SAFETY ALERT: If you are in danger, please use a safer computer and consider calling 911. The National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1-800-799-7233 / TTY 1-800-787-3224 or the StrongHearts Native Helpline at 1−844-762-8483 (call or text) are available to assist you.

Please review these safety tips .

Research & Evidence

NRCDV works to strengthen researcher/practitioner collaborations that advance the field’s knowledge of, access to, and input in research that informs policy and practice at all levels. We also identify and develop guidance and tools to help domestic violence programs and coalitions better evaluate their work, including by using participatory action research approaches that directly tap the diverse expertise of a community to frame and guide evaluation efforts.

Safety & Privacy in a Digital World

Immigrant Survivors of Domestic Violence

Teen Dating Violence

Housing and Domestic Violence

Domestic Violence in LGBTQ Communities

Trans and Non-Binary Survivors

The Difference Between Surviving & Not Surviving

Earned Income Tax Credit & Other Tax Credits

For an extensive list of research & evidence materials check out the research & statistics section on VAWnet

The Domestic Violence Evidence Project (DVEP) is a multi-faceted, multi-year and highly collaborative effort designed to assist state coalitions, local domestic violence programs, researchers, and other allied individuals and organizations better respond to the growing emphasis on identifying and integrating evidence-based practice into their work. DVEP brings together research, evaluation, practice and theory to inform critical thinking and enhance the field's knowledge to better serve survivors and their families.

The Community Based Participatory Research Toolkit (CBPR) is for researchers and practitioners across disciplines and social locations who are working in academic, policy, community, or practice-based settings. In particular, the toolkit provides support to emerging researchers as they consider whether and how to take a CBPR approach and what it might mean in the context of their professional roles and settings. Domestic violence advocates will also find useful information on the CBPR approach and how it can help answer important questions about your work.

For over two decades, the National Resource Center on Domestic Violence has operated VAWnet , an online library focused on violence against women and other forms of gender-based violence. VAWnet.org has long been identified as an unparalleled, comprehensive, go-to source of information and resources for anti-violence advocates, human service professionals, educators, faith leaders, and others interested in ending domestic and sexual violence.

Safe Housing Partnerships , the website of the Domestic Violence and Housing Technical Assistance Consortium , includes the latest research and evidence on the intersection of domestic and sexual violence, housing, and homelessness. You can also find new research exploring different aspects of efforts to expand housing options for domestic and sexual violence survivors, including the use of flexible funding approaches, DV Housing First and rapid rehousing, DV Transitional Housing, and mobile advocacy.

- Open access

- Published: 20 June 2023

A qualitative quantitative mixed methods study of domestic violence against women

- Mina Shayestefar 1 ,

- Mohadese Saffari 1 ,

- Razieh Gholamhosseinzadeh 2 ,

- Monir Nobahar 3 , 4 ,

- Majid Mirmohammadkhani 4 ,

- Seyed Hossein Shahcheragh 5 &

- Zahra Khosravi 6

BMC Women's Health volume 23 , Article number: 322 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

10k Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Violence against women is one of the most widespread, persistent and detrimental violations of human rights in today’s world, which has not been reported in most cases due to impunity, silence, stigma and shame, even in the age of social communication. Domestic violence against women harms individuals, families, and society. The objective of this study was to investigate the prevalence and experiences of domestic violence against women in Semnan.

This study was conducted as mixed research (cross-sectional descriptive and phenomenological qualitative methods) to investigate domestic violence against women, and some related factors (quantitative) and experiences of such violence (qualitative) simultaneously in Semnan. In quantitative study, cluster sampling was conducted based on the areas covered by health centers from married women living in Semnan since March 2021 to March 2022 using Domestic Violence Questionnaire. Then, the obtained data were analyzed by descriptive and inferential statistics. In qualitative study by phenomenological approach and purposive sampling until data saturation, 9 women were selected who had referred to the counseling units of Semnan health centers due to domestic violence, since March 2021 to March 2022 and in-depth and semi-structured interviews were conducted. The conducted interviews were analyzed using Colaizzi’s 7-step method.

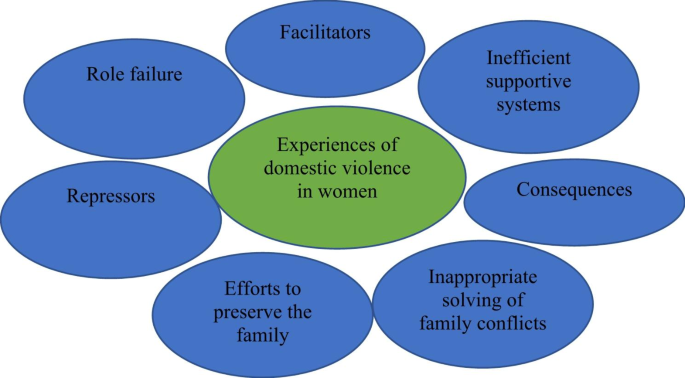

In qualitative study, seven themes were found including “Facilitators”, “Role failure”, “Repressors”, “Efforts to preserve the family”, “Inappropriate solving of family conflicts”, “Consequences”, and “Inefficient supportive systems”. In quantitative study, the variables of age, age difference and number of years of marriage had a positive and significant relationship, and the variable of the number of children had a negative and significant relationship with the total score and all fields of the questionnaire (p < 0.05). Also, increasing the level of female education and income both independently showed a significant relationship with increasing the score of violence.

Conclusions

Some of the variables of violence against women are known and the need for prevention and plans to take action before their occurrence is well felt. Also, supportive mechanisms with objective and taboo-breaking results should be implemented to minimize harm to women, and their children and families seriously.

Peer Review reports

Violence against women by husbands (physical, sexual and psychological violence) is one of the basic problems of public health and violation of women’s human rights. It is estimated that 35% of women and almost one out of every three women aged 15–49 experience physical or sexual violence by their spouse or non-spouse sexual violence in their lifetime [ 1 ]. This is a nationwide public health issue, and nearly every healthcare worker will encounter a patient who has suffered from some type of domestic or family violence. Unfortunately, different forms of family violence are often interconnected. The “cycle of abuse” frequently persists from children who witness it to their adult relationships, and ultimately to the care of the elderly [ 2 ]. This violence includes a range of physical, sexual and psychological actions, control, threats, aggression, abuse, and rape [ 3 ].

Violence against women is one of the most widespread, persistent, and detrimental violations of human rights in today’s world, which has not been reported in most cases due to impunity, silence, stigma and shame, even in the age of social communication [ 3 ]. In the United States of America, more than one in three women (35.6%) experience rape, physical violence, and intimate partner violence (IPV) during their lifetime. Compared to men, women are nearly twice as likely (13.8% vs. 24.3%) to experience severe physical violence such as choking, burns, and threats with knives or guns [ 4 ]. The higher prevalence of violence against women can be due to the situational deprivation of women in patriarchal societies [ 5 ]. The prevalence of domestic violence in Iran reported 22.9%. The maximum of prevalence estimated in Tehran and Zahedan, respectively [ 6 ]. Currently, Iran has high levels of violence against women, and the provinces with the highest rates of unemployment and poverty also have the highest levels of violence against women [ 7 ].

Domestic violence against women harms individuals, families, and society [ 8 ]. Violence against women leads to physical, sexual, psychological harm or suffering, including threats, coercion and arbitrary deprivation of their freedom in public and private life. Also, such violence is associated with harmful effects on women’s sexual reproductive health, including sexually transmitted infection such as Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), abortion, unsafe childbirth, and risky sexual behaviors [ 9 ]. There are high levels of psychological, sexual and physical domestic abuse among pregnant women [ 10 ]. Also, women with postpartum depression are significantly more likely to experience domestic violence during pregnancy [ 11 ].

Prompt attention to women’s health and rights at all levels is necessary, which reduces this problem and its risk factors [ 12 ]. Because women prefer to remain silent about domestic violence and there is a need to introduce immediate prevention programs to end domestic violence [ 13 ]. violence against women, which is an important public health problem, and concerns about human rights require careful study and the application of appropriate policies [ 14 ]. Also, the efforts to change the circumstances in which women face domestic violence remain significantly insufficient [ 15 ]. Given that few clear studies on violence against women and at the same time interviews with these people regarding their life experiences are available, the authors attempted to planning this research aims to investigate the prevalence and experiences of domestic violence against women in Semnan with the research question of “What is the prevalence of domestic violence against women in Semnan, and what are their experiences of such violence?”, so that their results can be used in part of the future planning in the health system of the society.

This study is a combination of cross-sectional and phenomenology studies in order to investigate the amount of domestic violence against women and some related factors (quantitative) and their experience of this violence (qualitative) simultaneously in the Semnan city. This study has been approved by the ethics committee of Semnan University of Medical Sciences with ethic code of IR.SEMUMS.REC.1397.182. The researcher introduced herself to the research participants, explained the purpose of the study, and then obtained informed written consent. It was assured to the research units that the collected information will be anonymous and kept confidential. The participants were informed that participation in the study was entirely voluntary, so they can withdraw from the study at any time with confidence. The participants were notified that more than one interview session may be necessary. To increase the trustworthiness of the study, Guba and Lincoln’s criteria for rigor, including credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability [ 16 ], were applied throughout the research process. The COREQ checklist was used to assess the present study quality. The researchers used observational notes for reflexivity and it preserved in all phases of this qualitative research process.

Qualitative method

Based on the phenomenological approach and with the purposeful sampling method, nine women who had referred to the counseling units of healthcare centers in Semnan city due to domestic violence in February 2021 to March 2022 were participated in the present study. The inclusion criteria for the study included marriage, a history of visiting a health center consultant due to domestic violence, and consent to participate in the study and unwillingness to participate in the study was the exclusion criteria. Each participant invited to the study by a telephone conversation about study aims and researcher information. The interviews place selected through agreement of the participant and the researcher and a place with the least environmental disturbance. Before starting each interview, the informed consent and all of the ethical considerations, including the purpose of the research, voluntary participation, confidentiality of the information were completely explained and they were asked to sign the written consent form. The participants were interviewed by depth, semi-structured and face-to-face interviews based on the main research question. Interviews were conducted by a female health services researcher with a background in nursing (M.Sh.). Data collection was continued until the data saturation and no new data appeared. Only the participants and the researcher were present during the interviews. All interviews were recorded by a MP3 Player by permission of the participants before starting. Interviews were not repeated. No additional field notes were taken during or after the interview.

The age range of the participants was from 38 to 55 years and their average age was 40 years. The sociodemographic characteristics of the participants are summarized in table below (Table 1 ).

Five interviews in the courtyards of healthcare centers, 2 interviews in the park, and 2 interviews at the participants’ homes were conducted. The duration of the interviews varied from 45 min to one hour. The main research question was “What is your experience about domestic violence?“. According to the research progress some other questions were asked in line with the main question of the research.

The conducted interviews were analyzed by using the 7 steps Colizzi’s method [ 17 ]. In order to empathize with the participants, each interview was read several times and transcribed. Then two researchers (M.Sh. and M.N.) extracted the phrases that were directly related to the phenomenon of domestic violence against women independently and distinguished from other sentences by underlining them. Then these codes were organized into thematic clusters and the formulated concepts were sorted into specific thematic categories.

In the final stage, in order to make the data reliable, the researcher again referred to 2 participants and checked their agreement with their perceptions of the content. Also, possible important contents were discussed and clarified, and in this way, agreement and approval of the samples was obtained.

Quantitative method

The cross-sectional study was implemented from February 2021 to March 2022 with cluster sampling of married women in areas of 3 healthcare centers in Semnan city. Those participants who were married and agreed with the written and verbal informed consent about the ethical considerations were included to the study. The questionnaire was completed by the participants in paper and online form.

The instrument was the standard questionnaire of domestic violence against women by Mohseni Tabrizi et al. [ 18 ]. In the questionnaire, questions 1–10, 11–36, 37–65 and 66–71 related to sociodemographic information, types of spousal abuse (psychological, economical, physical and sexual violence), patriarchal beliefs and traditions and family upbringing and learning violence, respectively. In total, this questionnaire has 71 items.

The scoring of the questionnaire has two parts and the answers to them are based on the Likert scale. Questions 11–36 and 66–71 are answered with always [ 4 ] to never (0) and questions 37–65 with completely agree [ 4 ] to completely disagree (0). The minimum and maximum score is 0 and 300, respectively. The total score of 0–60, 61–120 and higher than 121 demonstrates low, moderate and severe domestic violence against women, respectively [ 18 ].

In the study by Tabrizi et al., to evaluate the validity and reliability of this questionnaire, researchers tried to measure the face validity of the scale by the previous research. Those items and questions which their accuracies were confirmed by social science professors and experts used in the research, finally. The total Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.183, which confirmed that the reliability of the questions and items of the questionnaire is sufficient [ 18 ].

Descriptive data were reported using mean, standard deviation, frequency and percentage. Then, to measure the relationship between the variables, χ2 and Pearson tests also variance and regression analysis were performed. All analysis were performed by using SPSS version 26 and the significance level was considered as p < 0.05.

Qualitative results

According to the third step of Colaizzi’s 7-step method, the researcher attempted to conceptualize and formulate the extracted meanings. In this step, the primary codes were extracted from the important sentences related to the phenomenon of violence against women, which were marked by underlining, which are shown below as examples of this stage and coding.

The primary code of indifference to the father’s role was extracted from the following sentences. This is indifference in the role of the father in front of the children.

“Some time ago, I told him that our daughter is single-sided deaf. She has a doctor’s appointment; I have to take her to the doctor. He said that I don’t have money to give you. He doesn’t force himself to make money anyway” (p 2, 33 yrs).

“He didn’t value his own children. He didn’t think about his older children” (p 4, 54 yrs).

The primary code extracted here included lack of commitment in the role of head of the household. This is irresponsibility towards the family and meeting their needs.

“My husband was fired from work after 10 years due to disorder and laziness. Since then, he has not found a suitable job. Every time he went to work, he was fired after a month because of laziness” (p 7, 55 yrs).

“In the evening, he used to get dressed and go out, and he didn’t come back until late. Some nights, I was so afraid of being alone that I put a knife under my pillow when I slept” (p 2, 33 yrs).

A total of 246 primary codes were extracted from the interviews in the third step. In the fourth step, the researchers put the formulated concepts (primary codes) into 85 specific sub-categories.

Twenty-three categories were extracted from 85 sub-categories. In the sixth step, the concepts of the fifth step were integrated and formed seven themes (Table 2 ).

These themes included “Facilitators”, “Role failure”, “Repressors”, “Efforts to preserve the family”, “Inappropriate solving of family conflicts”, “Consequences”, and “Inefficient supportive systems” (Fig. 1 ).

Themes of domestic violence against women

Some of the statements of the participants on the theme of “ Facilitators” are listed below:

Husband’s criminal record

“He got his death sentence for drugs. But, at last it was ended for 10 years” (p 4, 54 yrs).

Inappropriate age for marriage

“At the age of thirteen, I married a boy who was 25 years old” (p 8, 25 yrs).

“My first husband obeyed her parents. I was 12–13 years old” (p 3, 32 yrs).

“I couldn’t do anything. I was humiliated” (p 1, 38 yrs).

“A bridegroom came. The mother was against. She said, I am young. My older sister is not married yet, but I was eager to get married. I don’t know, maybe my father’s house was boring for me” (p 2, 33 yrs).

“My parents used to argue badly. They blamed each other and I always wanted to run away from these arguments. I didn’t have the patience to talk to mom or dad and calm them down” (p 5, 39 yrs).

Overdependence

“My husband’s parents don’t stop interfering, but my husband doesn’t say anything because he is a student of his father. My husband is self-employed and works with his father on a truck” (p 8, 25 yrs).

“Every time I argue with my husband because of lack of money, my mother-in-law supported her son and brought him up very spoiled and lazy” (p 7, 55 yrs).

Bitter memories

“After three years, my mother married her friend with my uncle’s insistence and went to Shiraz. But, his condition was that she did not have the right to bring his daughter with her. In fact, my mother also got married out of necessity” (p 8, 25 yrs).

Some of their other statements related to “ Role failure” are mentioned below:

Lack of commitment to different roles

“I got angry several times and went to my father’s house because of my husband’s bad financial status and the fact that he doesn’t feel responsible to work and always says that he cannot find a job” (p 6, 48 yrs).

“I saw that he does not want to change in any way” (p 4, 54 yrs).

“No matter how kind I am, it does not work” (p 1, 38 yrs).

Some of their other statements regarding “ Repressors” are listed below:

Fear and silence

“My mother always forced me to continue living with my husband. Finally, my father had been poor. She all said that you didn’t listen to me when you wanted to get married, so you don’t have the right to get angry and come to me, I’m miserable enough” (p 2, 33 yrs).

“Because I suffered a lot in my first marital life. I was very humiliated. I said I would be fine with that. To be kind” (p1, 38 yrs).

“Well, I tell myself that he gets angry sometimes” (p 3, 32 yrs).

Shame from society

“I don’t want my daughter-in-law to know. She is not a relative” (p 4, 54 yrs).

Some of the statements of the participants regarding the theme of “ Efforts to preserve the family” are listed below:

Hope and trust

“I always hope in God and I am patient” (p 2, 33 yrs).

Efforts for children

“My divorce took a month. We got a divorce. I forgave my dowry and took my children instead” (p 2, 33 yrs).

Some of their other statements regarding the “ Inappropriate solving of family conflicts” are listed below:

Child-bearing thoughts

“My husband wanted to take me to a doctor to treat me. But my father-in-law refused and said that instead of doing this and spending money, marry again. Marriage in the clans was much easier than any other work” (p 8, 25 yrs).

Lack of effective communication

“I was nervous about him, but I didn’t say anything” (p 5, 39 yrs).

“Now I am satisfied with my life and thank God it is better to listen to people’s words. Now there is someone above me so that people don’t talk behind me” (p 2, 33 yrs).

Some of their other statements regarding the “ Consequences” are listed below:

Harm to children

“My eldest daughter, who was about 7–8 years old, behaved differently. Oh, I was angry. My children are mentally depressed and argue” (p 5, 39 yrs).

After divorce

“Even though I got a divorce, my mother and I came to a remote area due to the fear of what my family would say” (p 2, 33 yrs).

Social harm

“I work at a retirement center for living expenses” (p 2, 33 yrs).

“I had to go to clean the houses” (p 5, 39 yrs).

Non-acceptance in the family

“The children’s relationship with their father became bad. Because every time they saw their father sitting at home smoking, they got angry” (p 7, 55 yrs).

Emotional harm

“When I look back, I regret why I was not careful in my choice” (p 7, 55 yrs).

“I felt very bad. For being married to a man who is not bound by the family and is capricious” (p 9, 36 yrs).

Some of their other statements regarding “ Inefficient supportive systems” are listed below:

Inappropriate family support

“We didn’t have children. I was at my father’s house for about a month. After a month, when I came home, I saw that my husband had married again. I cried a lot that day. He said, God, I had to. I love you. My heart is broken, I have no one to share my words” (p 8, 25 yrs).

“My brother-in-law was like himself. His parents had also died. His sister did not listen at all” (p 4, 54 yrs).

“I didn’t have anyone and I was alone” (p 1, 38 yrs).

Inefficiency of social systems

“That day he argued with me, picked me up and threw me down some stairs in the middle of the yard. He came closer, sat on my stomach, grabbed my neck with both of his hands and wanted to strangle me. Until a long time later, I had kidney problems and my neck was bruised by her hand. Given that my aunt and her family were with us in a building, but she had no desire to testify and was afraid” (p 3, 32 yrs).

Undesired training and advice

“I told my mother, you just said no, how old I was? You never insisted on me and you didn’t listen to me that this man is not good for you” (p 9, 36 yrs).

Quantitative results

In the present study, 376 married women living in Semnan city participated in this study. The mean age of participants was 38.52 ± 10.38 years. The youngest participant was 18 and the oldest was 73 years old. The maximum age difference was 16 years. The years of marriage varied from one year to 40 years. Also, the number of children varied from no children to 7. The majority of them had 2 children (109, 29%). The sociodemographic characteristics of the participants are summarized in the table below (Table 3 ).

The frequency distribution (number and percentage) of the participants in terms of the level of violence was as follows. 89 participants (23.7%) had experienced low violence, 59 participants (15.7%) had experienced moderate violence, and 228 participants (60.6%) had experienced severe violence.

Cronbach’s alpha for the reliability of the questionnaire was 0.988. The mean and standard deviation of the total score of the questionnaire was 143.60 ± 74.70 with a range of 3-244. The relationship between the total score of the questionnaire and its fields, and some demographic variables is summarized in the table below (Table 4 ).

As shown in the table above, the variables of age, age difference and number of years of marriage have a positive and significant relationship, and the variable of number of children has a negative and significant relationship with the total score and all fields of the questionnaire (p < 0.05). However, the variable of education level difference showed no significant relationship with the total score and any of the fields. Also, the highest average score is related to patriarchal beliefs compared to other fields.

The comparison of the average total scores separately according to each variable showed the significant average difference in the variables of the previous marriage history of the woman, the result of the previous marriage of the woman, the education of the woman, the education of the man, the income of the woman, the income of the man, and the physical disease of the man (p < 0.05).

In the regression model, two variables remained in the final model, indicating the relationship between the variables and violence score and the importance of these two variables. An increase in women’s education and income level both independently show a significant relationship with an increase in violence score (Table 5 ).

The results of analysis of variance to compare the scores of each field of violence in the subgroups of the participants also showed that the experience and result of the woman’s previous marriage has a significant relationship with physical violence and tradition and family upbringing, the experience of the man’s previous marriage has a significant relationship with patriarchal belief, the education level of the woman has a significant relationship with all fields and the level of education of the man has a significant relationship with all fields except tradition and family upbringing (p < 0.05).

According to the results of both quantitative and qualitative studies, variables such as the young age of the woman and a large age difference are very important factors leading to an increase in violence. At a younger age, girls are afraid of the stigma of society and family, and being forced to remain silent can lead to an increase in domestic violence. As Gandhi et al. (2021) stated in their study in the same field, a lower marriage age leads to many vulnerabilities in women. Early marriage is a global problem associated with a wide range of health and social consequences, including violence for adolescent girls and women [ 12 ]. Also, Ahmadi et al. (2017) found similar findings, reporting a significant association among IPV and women age ≤ 40 years [ 19 ].

Two others categories of “Facilitators” in the present study were “Husband’s criminal record” and “Overdependence” which had a sub-category of “Forced cohabitation”. Ahmadi et al. (2017) reported in their population-based study in Iran that husband’s addiction and rented-householders have a significant association with IPV [ 19 ].

The patriarchal beliefs, which are rooted in the tradition and culture of society and family upbringing, scored the highest in relation to domestic violence in this study. On the other hand, in qualitative study, “Normalcy” of men’s anger and harassment of women in society is one of the “Repressors” of women to express violence. In the quantitative study, the increase in the women’s education and income level were predictors of the increase in violence. Although domestic violence is more common in some sections of society, women with a wide range of ages, different levels of education, and at different levels of society face this problem, most of which are not reported. Bukuluki et al. (2021) showed that women who agreed that it is good for a man to control his partner were more likely to experience physical violence [ 20 ].

Domestic violence leads to “Consequences” such as “Harm to children”, “Emotional harm”, “Social harm” to women and even “Non-acceptance in their own family”. Because divorce is a taboo in Iranian culture and the fear of humiliating women forces them to remain silent against domestic violence. Balsarkar (2021) stated that the fear of violence can prevent women from continuing their studies, working or exercising their political rights [ 8 ]. Also, Walker-Descarte et al. (2021) recognized domestic violence as a type of child maltreatment, and these abusive behaviors are associated with mental and physical health consequences [ 21 ].

On the other hand and based on the “Lack of effective communication” category, ignoring the role of the counselor in solving family conflicts and challenges in the life of couples in the present study was expressed by women with reasons such as lack of knowledge and family resistance to counseling. Several pathologies are needed to investigate increased domestic violence in situations such as during women’s pregnancy or infertility. Because the use of counseling for couples as a suitable solution should be considered along with their life challenges. Lin et al. (2022) stated that pregnant women were exposed to domestic violence for low birth weight in full term delivery. Spouse violence screening in the perinatal health care system should be considered important, especially for women who have had full-term low birth weight infants [ 22 ].

Also, lack of knowledge and low level of education have been found as other factors of violence in this study, which is very prominent in both qualitative and quantitative studies. Because the social systems and information about the existing laws should be followed properly in society to act as a deterrent. Psychological training and especially anger control and resilience skills during education at a younger age for girls and boys should be included in educational materials to determine the positive results in society in the long term. Manouchehri et al. (2022) stated that it seems necessary to train men about the negative impact of domestic violence on the current and future status of the family [ 23 ]. Balsarkar (2021) also stated that men and women who have not had the opportunity to question gender roles, attitudes and beliefs cannot change such things. Women who are unaware of their rights cannot claim. Governments and organizations cannot adequately address these issues without access to standards, guidelines and tools [ 8 ]. Machado et al. (2021) also stated that gender socialization reinforces gender inequalities and affects the behavior of men and women. So, highlighting this problem in different fields, especially in primary health care services, is a way to prevent IPV against women [ 24 ].

There was a sub-category of “Inefficiency of social systems” in the participants experiences. Perhaps the reason for this is due to insufficient education and knowledge, or fear of seeking help. Holmes et al. (2022) suggested the importance of ascertaining strategies to improve victims’ experiences with the court, especially when victims’ requests are not met, to increase future engagement with the system [ 25 ]. Sigurdsson (2019) revealed that despite high prevalence numbers, IPV is still a hidden and underdiagnosed problem and neither general practitioner nor our communities are as well prepared as they should be [ 26 ]. Moreira and Pinto da Costa (2021) found that while victims of domestic violence often agree with mandatory reporting, various concerns are still expressed by both victims and healthcare professionals that require further attention and resolution [ 27 ]. It appears that legal and ethical issues in this regard require comprehensive evaluation from the perspectives of victims, their families, healthcare workers, and legal experts. By doing so, better practical solutions can be found to address domestic violence, leading to a downward trend in its occurrence.

Some of the variables of violence against women have been identified and emphasized in many studies, highlighting the necessity of policymaking and social pathology in society to prevent and use operational plans to take action before their occurrence. Breaking the taboo of domestic violence and promoting divorce as a viable solution after counseling to receive objective results should be implemented seriously to minimize harm to women, children, and their families.

Limitations

Domestic violence against women is an important issue in Iranian society that women resist showing and expressing, making researchers take a long-term process of sampling in both qualitative and quantitative studies. The location of the interview and the women’s fear of their husbands finding out about their participation in this study have been other challenges of the researchers, which, of course, they attempted to minimize by fully respecting ethical considerations. Despite the researchers’ efforts, their personal and professional experiences, as well as the studies reviewed in the literature review section, may have influenced the study results.

Data Availability

Data and materials will be available upon email to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

Intimate Partner Violence

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

Organization WH. Violence against women prevalence estimates, 2018: global, regional and national prevalence estimates for intimate partner violence against women and global and regional prevalence estimates for non-partner sexual violence against women. World Health Organization; 2021.

Huecker MR, Malik A, King KC, Smock W. Kentucky Domestic Violence. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. Disclosure: Ahmad Malik declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies. Disclosure: Kevin King declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies. Disclosure: William Smock declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.: StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2023, StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2023.

Gandhi A, Bhojani P, Balkawade N, Goswami S, Kotecha Munde B, Chugh A. Analysis of survey on violence against women and early marriage: Gyneaecologists’ perspective. J Obstet Gynecol India. 2021;71(Suppl 2):76–83.

Article Google Scholar

Sugg N. Intimate partner violence: prevalence, health consequences, and intervention. Med Clin. 2015;99(3):629–49.

Google Scholar

Abebe Abate B, Admassu Wossen B, Tilahun Degfie T. Determinants of intimate partner violence during pregnancy among married women in Abay Chomen district, western Ethiopia: a community based cross sectional study. BMC Womens Health. 2016;16(1):1–8.

Adineh H, Almasi Z, Rad M, Zareban I, Moghaddam A. Prevalence of domestic violence against women in Iran: a systematic review. Epidemiol (Sunnyvale). 2016;6(276):2161–11651000276.

Pirnia B, Pirnia F, Pirnia K. Honour killings and violence against women in Iran during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(10):e60.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Balsarkar G. Summary of four recent studies on violence against women which obstetrician and gynaecologists should know. J Obstet Gynecol India. 2021;71:64–7.

Ellsberg M, Jansen HA, Heise L, Watts CH, Garcia-Moreno C. Intimate partner violence and women’s physical and mental health in the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence: an observational study. The lancet. 2008;371(9619):1165–72.

Chasweka R, Chimwaza A, Maluwa A. Isn’t pregnancy supposed to be a joyful time? A cross-sectional study on the types of domestic violence women experience during pregnancy in Malawi. Malawi Med journal: J Med Association Malawi. 2018;30(3):191–6.

Afshari P, Tadayon M, Abedi P, Yazdizadeh S. Prevalence and related factors of postpartum depression among reproductive aged women in Ahvaz. Iran Health care women Int. 2020;41(3):255–65.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Gebrezgi BH, Badi MB, Cherkose EA, Weldehaweria NB. Factors associated with intimate partner physical violence among women attending antenatal care in Shire Endaselassie town, Tigray, northern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study, July 2015. Reproductive health. 2017;14:1–10.

Duran S, Eraslan ST. Violence against women: affecting factors and coping methods for women. J Pak Med Assoc. 2019;69(1):53–7.

PubMed Google Scholar

Devries KM, Mak JY, Garcia-Moreno C, Petzold M, Child JC, Falder G, et al. The global prevalence of intimate partner violence against women. Science. 2013;340(6140):1527–8.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Mahapatro M, Kumar A. Domestic violence, women’s health, and the sustainable development goals: integrating global targets, India’s national policies, and local responses. J Public Health Policy. 2021;42(2):298–309.

Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry: sage; 1985.

Colaizzi PF. Psychological research as the phenomenologist views it. 1978.

Mohseni Tabrizi A, Kaldi A, Javadianzadeh M. The study of domestic violence in Marrid Women Addmitted to Yazd Legal Medicine Organization and Welfare Organization. Tolooebehdasht. 2013;11(3):11–24.

Ahmadi R, Soleimani R, Jalali MM, Yousefnezhad A, Roshandel Rad M, Eskandari A. Association of intimate partner violence with sociodemographic factors in married women: a population-based study in Iran. Psychol Health Med. 2017;22(7):834–44.

Bukuluki P, Kisaakye P, Wandiembe SP, Musuya T, Letiyo E, Bazira D. An examination of physical violence against women and its justification in development settings in Uganda. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(9):e0255281.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Walker-Descartes I, Mineo M, Condado LV, Agrawal N. Domestic violence and its Effects on Women, Children, and families. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2021;68(2):455–64.

Lin C-H, Lin W-S, Chang H-Y, Wu S-I. Domestic violence against pregnant women is a potential risk factor for low birthweight in full-term neonates: a population-based retrospective cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(12):e0279469.

Manouchehri E, Ghavami V, Larki M, Saeidi M, Latifnejad Roudsari R. Domestic violence experienced by women with multiple sclerosis: a study from the North-East of Iran. BMC Womens Health. 2022;22(1):1–14.

Machado DF, Castanheira ERL, Almeida MASd. Intersections between gender socialization and violence against women by the intimate partner. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva. 2021;26:5003–12.

Holmes SC, Maxwell CD, Cattaneo LB, Bellucci BA, Sullivan TP. Criminal Protection orders among women victims of intimate Partner violence: Women’s Experiences of Court decisions, processes, and their willingness to Engage with the system in the future. J interpers Violence. 2022;37(17–18):Np16253–np76.

Sigurdsson EL. Domestic violence-are we up to the task? Scand J Prim Health Care. 2019;37(2):143–4.

Moreira DN, Pinto da Costa M. Should domestic violence be or not a public crime? J Public Health. 2021;43(4):833–8.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors of this study appreciate the Deputy for Research and Technology of Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Social Determinants of Health Research Center of Semnan University of Medical Sciences and all the participants in this study.

Research deputy of Semnan University of Medical Sciences financially supported this project.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Allied Medical Sciences, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran

Mina Shayestefar & Mohadese Saffari

Amir Al Momenin Hospital, Social Security Organization, Ahvaz, Iran

Razieh Gholamhosseinzadeh

Department of Nursing, Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran

Monir Nobahar

Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran

Monir Nobahar & Majid Mirmohammadkhani

Clinical Research Development Unit, Kowsar Educational, Research and Therapeutic Hospital, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran

Seyed Hossein Shahcheragh

Student Research Committee, School of Allied Medical Sciences, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran

Zahra Khosravi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

M.Sh. contributed to the first conception and design of this research; M.Sh., Z.Kh., M.S., R.Gh. and S.H.Sh. contributed to collect data; M.N. and M.Sh. contributed to the analysis of the qualitative data; M.M. and M.Sh. contributed to the analysis of the quantitative data; M.SH., M.N. and M.M. contributed to the interpretation of the data; M.Sh., M.S. and S.H.Sh. wrote the manuscript. M.Sh. prepared the final version of manuscript for submission. All authors reviewed the manuscript meticulously and approved it. All names of the authors were listed in the title page.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mina Shayestefar .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This article is resulted from a research approved by the Vice Chancellor for Research of Semnan University of Medical Sciences with ethics code of IR.SEMUMS.REC.1397.182 in the Social Determinants of Health Research Center. The authors confirmed that all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. All participants accepted the participation in the present study. The researchers introduced themselves to the research units, explained the purpose of the research to them and then all participants signed the written informed consent. The research units were assured that the collected information was anonymous. The participant was informed that participating in the study was completely voluntary so that they can safely withdraw from the study at any time and also the availability of results upon their request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare that there are no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Shayestefar, M., Saffari, M., Gholamhosseinzadeh, R. et al. A qualitative quantitative mixed methods study of domestic violence against women. BMC Women's Health 23 , 322 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-023-02483-0

Download citation

Received : 28 April 2023

Accepted : 14 June 2023

Published : 20 June 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-023-02483-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Domestic violence

- Cross-sectional studies

- Qualitative research

BMC Women's Health

ISSN: 1472-6874

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Diverse Intimate Partner Violence Survivors' Experiences Seeking Help from the Police: A Qualitative Research Synthesis

Affiliations.

- 1 Boise State University, ID, USA.

- 2 Old Dominion University, Norfolk, VA, USA.

- 3 University of Houston-Downtown, TX, USA.

- 4 Department of the Air Force, Washington, D.C, USA.

- PMID: 39150320

- DOI: 10.1177/15248380241270083

Intimate partner violence (IPV), inclusive of all forms of abuse, is an ongoing public health and criminal-legal issue that transcends social boundaries. However, there is a lack of equitable representation of diverse populations who experience IPV in the literature. To garner a holistic knowledge of diverse IPV survivor populations' experiences with seeking help from the police, the current review utilized a qualitative research synthesis methodology to explore police interactions among six IPV survivor populations that are underrepresented in the current literature: women with substance use issues, immigrant women, women in rural localities, heterosexual men, racially/ethnically minoritized women, and sexual minority women. Seven electronic databases were searched to identify peer-reviewed articles on IPV survivors' narrative descriptions (qualitative or mixed-methods) of their encounters with law enforcement. The final analysis included 28 studies that were then coded with an iterative coding strategy. The analysis uncovered the following themes: (a) revictimization by the police, (b) police negligence, (c) discrimination, (d) cultural differences, and (e) positive experiences. These themes demonstrated that while some experiences with law enforcement were shared between under-researched survivor groups, some experiences were explicitly tied to some aspects of survivors' identities. Recognizing the potential law enforcement has to support survivors, the findings of the current review reiterate the need for ongoing efforts to improve law enforcement knowledge and overall response to IPV, especially for diverse populations of IPV survivors.

Keywords: diverse populations; domestic violence; help-seeking; intimate partner violence; police response; qualitative synthesis; survivor experiences.

PubMed Disclaimer

Conflict of interest statement

Declaration of Conflicting InterestsThe author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Similar articles

- The Contextual Influences of Police and Social Service Providers on Formal Help-Seeking After Incidents of Intimate Partner Violence. Augustyn MB, Willyard KC. Augustyn MB, et al. J Interpers Violence. 2022 Jan;37(1-2):NP1077-NP1104. doi: 10.1177/0886260520915551. Epub 2020 May 18. J Interpers Violence. 2022. PMID: 32418469

- Rural Australian women's legal help seeking for intimate partner violence: women intimate partner violence victim survivors' perceptions of criminal justice support services. Ragusa AT. Ragusa AT. J Interpers Violence. 2013 Mar;28(4):685-717. doi: 10.1177/0886260512455864. Epub 2012 Aug 27. J Interpers Violence. 2013. PMID: 22929344

- Healthcare provider experiences interacting with survivors of intimate partner violence: a qualitative study to inform survivor-centered approaches. Anguzu R, Cassidy LD, Nakimuli AO, Kansiime J, Babikako HM, Beyer KMM, Walker RJ, Wandira C, Kizito F, Dickson-Gomez J. Anguzu R, et al. BMC Womens Health. 2023 Nov 8;23(1):584. doi: 10.1186/s12905-023-02700-w. BMC Womens Health. 2023. PMID: 37940914 Free PMC article.

- Survivor, family and professional experiences of psychosocial interventions for sexual abuse and violence: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Brown SJ, Carter GJ, Halliwell G, Brown K, Caswell R, Howarth E, Feder G, O'Doherty L. Brown SJ, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022 Oct 4;10(10):CD013648. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013648.pub2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022. PMID: 36194890 Free PMC article. Review.

- Influence of Cultural Norms on Formal Service Engagement Among Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence: A Qualitative Meta-synthesis. Green J, Satyen L, Toumbourou JW. Green J, et al. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2024 Jan;25(1):738-751. doi: 10.1177/15248380231162971. Epub 2023 Apr 19. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2024. PMID: 37073947 Free PMC article. Review.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Related information

Linkout - more resources, full text sources.

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

- Frontiers in Psychology

- Gender, Sex and Sexualities

- Research Topics

New Perspectives on Domestic Violence: from Research to Intervention

Total Downloads

Total Views and Downloads

About this Research Topic

In a document dated June 16th 2017, the United States Department of Justice stated that Domestic Violence (DV) has a significant impact not only on those abused, but also on family members, friends, and on the people within the social networks of both the abuser and the victim. In this sense, children who ...

Keywords : domestic violence, intimate partner violence, victims, perpetrators, societal attitudes, gender violence, intervention and prevention, relevant research, same sex intimate partner violence, same sex domestic violence

Important Note : All contributions to this Research Topic must be within the scope of the section and journal to which they are submitted, as defined in their mission statements. Frontiers reserves the right to guide an out-of-scope manuscript to a more suitable section or journal at any stage of peer review.

Topic Editors

Topic coordinators, recent articles, submission deadlines.

Submission closed.

Participating Journals

Total views.

- Demographics

No records found

total views article views downloads topic views

Top countries

Top referring sites, about frontiers research topics.

With their unique mixes of varied contributions from Original Research to Review Articles, Research Topics unify the most influential researchers, the latest key findings and historical advances in a hot research area! Find out more on how to host your own Frontiers Research Topic or contribute to one as an author.

Domestic Violence Facts and Statistics * Domestic Violence Video Presentations * Online CEU Courses

From the Editorial Board of the Peer-Reviewed Journal, Partner Abuse www.springerpub.com/pa and the Advisory Board of the Association of Domestic Violence Intervention Programs www.battererintervention.org * www.domesticviolenceintervention.net

Resources for researchers, policy-makers, intervention providers, victim advocates, law enforcement, judges, attorneys, family court mediators, educators, and anyone interested in family violence

PASK FINDINGS

61-Page Author Overview

Domestic Violence Facts and Statistics at-a-Glance

PASK Researchers

PASK Video Summary by John Hamel, LCSW

- Introduction

- Implications for Policy and Treatment

- Domestic Violence Politics

17 Full PASK Manuscripts and tables of Summarized Studies

INTERNATIONAL RESEARCH

FACTS AND STATISTICS ON DOMESTIC VIOLENCE AT-A-GLANCE

Sponsored by the peer-reviewed journal partner abuse https://www.springerpub.com/partner-abuse.html , and the association of domestic violence intervention providers https://domesticviolenceintervention.net/, facts and statistics on prevalence of partner abuse, victimization.

- Overall, 22% of individuals assaulted by a partner at least once in their lifetime (23% for females and 19.3% for males)

- Higher overall rates among dating students

- Higher victimization for male than female high school students

- Lifetime rates higher among women than men

- Past year rates somewhat higher among men

- Higher rates of intimate partner violence (IPV) among younger, dating populations “highlights the need for school-based IPV prevention and intervention efforts”

Perpetration

- Overall, 25.3% of individuals have perpetrated IPV

- Rates of female-perpetrated violence higher than male-perpetrated (28.3% vs. 21.6%)

- Wide range in perpetration rates: 1.0% to 61.6% for males; 2.4% to 68.9% for women,

- Range of findings due to variety of samples and operational definitions of PV

Emotional Abuse and Control

- 80% of individuals have perpetrated emotional abuse

- Emotional abuse categorized as either expressive (in response to a provocation) or coercive (intended to monitor, control and/or threaten)

- Across studies, 40% of women and 32% of men reported expressive abuse; 41% of women and 43% of men reported coercive abuse

- According to national samples, 0.2% of men and 4.5% of women have been forced to have sexual intercourse by a partner

- 4.1% to 8% of women and 0.5% to 2% of men report at least one incident of stalking during their lifetime

- Intimate stalkers comprise somewhere between one-third and one half of all stalkers.

- Within studies of stalking and obsessive behaviors, gender differences are much less when all types of obsessive pursuit behaviors are considered, but more skewed toward female victims when the focus is on physical stalking

Facts and Statistics on Context

Bi-directional vs. uni-directional.

- Among large population samples, 57.9% of IPV reported was bi-directional, 42% unidirectional; 13.8% of the unidirectional violence was male to female (MFPV), 28.3% was female to male (FMPV)

- Among school and college samples, percentage of bidirectional violence was 51.9%; 16.2% was MFPV and 31.9% was FMPV

- Among respondents reporting IPV in legal or female-oriented clinical/treatment seeking samples not associated with the military, 72.3% was bi-directional; 13.3% was MFPV, 14.4% was FMPV

- Within military and male treatment samples, only 39% of IPV was bi-directional; 43.4% was MFPV and 17.3% FMPV

- Unweighted rates: bidirectional rates ranged from 49.2% (legal/female treatment) to 69.7% (legal/male treatment)

- Extent of bi-directionality in IPV comparable between heterosexual and LGBT populations

- 50.9% of IPV among Whites bilateral; 49% among Latinos; 61.8% among African-Americans

- Male and female IPV perpetrated from similar motives – primarily to get back at a partner for emotionally hurting them, because of stress or jealousy, to express anger and other feelings that they could not put into words or communicate, and to get their partner’s attention.

- Eight studies directly compared men and women in the power/control motive and subjected their findings to statistical analyses. Three reported no significant gender differences and one had mixed findings. One paper found that women were more motivated to perpetrate violence as a result of power/control than were men, and three found that men were more motivated; however, gender differences were weak

- Of the ten papers containing gender-specific statistical analyses, five indicated that women were significantly more likely to report self-defense as a motive for perpetration than men. Four papers did not find statistically significant gender differences, and one paper reported that men were more likely to report this motive than women. Authors point out that it might be particularly difficult for highly masculine males to admit to perpetrating violence in self-defense, as this admission implies vulnerability.

- Self-defense was endorsed in most samples by only a minority of respondents, male and female. For non-perpetrator samples, the rates of self-defense reported by men ranged from 0% to 21%, and for women the range was 5% to 35%. The highest rates of reported self-defense motives (50% for men, 65.4% for women) came from samples of perpetrators, who may have reasons to overestimate this motive.

- None of the studies reported that anger/retaliation was significantly more of a motive for men than women’s violence; instead, two papers indicated that anger was more likely to be a motive for women’s violence as compared to men.

- Jealousy/partner cheating seems to be a motive to perpetrate violence for both men and women.

Facts and Statistics on Risk Factors

- Demographic risk factors predictive of IPV: younger age, low income/unemployment, minority group membership

- Low to moderate correlations between childhood-of-origin exposure to abuse and IPV

- Protective factors against dating violence: Positive, involved parenting during adolescence, encouragement of nonviolent behavior; supportive peers

- Negative peer involvement predictive of teen dating violence

- Conduct disorder/anti-social personality risk factors for IPV

- Weak association between depression and IPV, strongest for women

- Weak association overall between alcohol and IPV, but stronger association for drug use

- Alcohol use more strongly associated with female-perpetrated than male-perpetrated IPV

- Married couples at lower risk than dating couples; separated women the most vulnerable

- Low relationship satisfaction and high conflict predictive of IPV, especially high conflict

- With few exception, IPV risk factors the same for men and women

Facts and Statistics on Impact on Victims, Children and Families

Impact on partners.

- Victims of physical abuse experience more physical injuries, poorer physical functioning and health outcomes, higher rates of psychological symptoms and disorders, and poorer cognitive functioning compared to non-victims. These findings were consistent regardless of the nature of the sample, and, with some exceptions were generally greater for female victims compared to male victims.

- Physical abuse significantly decreases female victims’ psychological well-being, increases the probability of suffering from depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and substance abuse; and victimized women more likely to report visits to mental health professionals and to take medications including painkillers and tranquilizers.

- Few studies have examined the consequences of physical victimization in men, and the studies that have been conducted have focused primarily on sex differences in injury rates.

- When severe aggression has been perpetrated (e.g., punching, kicking, using a weapon), rates of injury are much higher among female victims than male victims, and those injuries are more likely to be life-threatening and require a visit to an emergency room or hospital. However, when mild-to-moderate aggression is perpetrated (e.g., shoving, pushing, slapping), men and women tend to report similar rates of injury.

- Physically abused women have been found to engage in poorer health behaviors and risky sexual behaviors. They are more likely to miss work, have fewer social and emotional support networks are also less likely to be able to take care of their children and perform household duties.

- Similarly, psychological victimization among women is significantly associated with poorer occupational functioning and social functioning.

- Psychological victimization is strongly associated with symptoms of depression and suicidal ideation, anxiety, self-reported fear and increased perceived stress, insomnia and poor self-esteem

- Psychological victimization is at least as strongly related as physical victimization to depression, PTSD, and alcohol use as is physical victimization, and effects of psychological victimization remain even after accounting for the effects of physical victimization.

- Because research on the psychological consequences of abuse on male victims is very limited and has yielded mixed findings (some studies find comparable effects of psychological abuse across gender, while others do not) it is premature to draw any firm conclusions about this issue.

Effects of Partner Violence and Conflict on Children

- Significant correlation between witnessing mutual PV and both internalizing (e.g., anxiety, depression) and externalizing outcomes (e.g., school problems, aggression) for children and adolescents

- Exposure to male-perpetrated PV: Worse outcomes in internalizing and externalizing problems, including higher rates of aggression toward family members and dating partners, compared to no exposure

- Children and teens exposed to female-perpetrated PV significantly more likely to aggress against peers, family members and dating partners compared to those not so exposed

- Results mixed regarding additive effect of exposure to PV and experiencing direct child abuse

- Witnessing PV in childhood correlated with trauma symptoms and depression in adulthood

- Child abuse correlated with family violence perpetration in adulthood

- Children more impacted by exposure to conflict characterized by contempt, hostility and withdrawal compared to those characterized only by anger

- Greater impact when topic discussed concerns the child (e.g., disagreements over child rearing, blaming the child)

- High inter-parental conflict/emotional abuse leads to a decrease in parental sensitivity, warmth and consistent discipline; and an increase in harsh discipline and psychological control

- Neurobiological and physical functioning mediate relationship between inter-parental conflict and negative child outcomes

- Maternal behaviors somewhat more affected than paternal behaviors, but findings are equivocal, given difficulty in disaggregating male and female perpetrated conflict from couple level operationalizations

- Greater effects found for mother-child relationships and child outcomes through the toddler years; greater effects found for father-child relationships and child outcomes during the school-age years

- Family systems theory useful in understanding how discord in one part of the family can impact functioning in the family as a whole, even if it poses some methodological and explanatory challenges

Facts and Statistics on Partner Abuse in Other Populations

Partner abuse in ethnic minority and lgbt populations.

- African-Americans: Older studies found higher rates of male-to-female partner violence (MFPV); recent studies have found higher rates of female-to-male partner violence (FMPV)

- Psychological aggression reported at significantly higher rates than physical aggression

- As with White populations, minor/moderate aggression far more prevalent among Black couples than severe aggression

- In dating studies, no gender differences found in rates of physical or psychological victimization, but women reported higher rates of physical aggression than men

- Latinos: Mutual and minor/moderate PV most prevalent, but not as much as psychological aggression

- No gender differences for physical or psychological aggression, except among migrant farm workers where MFPV was highest

- Asian Americans: The one general population study found percentage of mutual violence perpetration to be one-third of total

- Overall rates of PV comparable across gender in large population, community and dating samples

- Lowest rates found among Vietnamese, compared to respondents who identified as Filipino, Chinese or others of Asian descent

- Native Americans: Only three studies found; women reported higher rates of victimization than men, and reported higher levels of injuries incurred

- Risk factors for ethnic minority PV include: substance abuse, low SES, and violence exposure and victimization in childhood

- LGBT populations: Higher overall rates compared to heterosexual populations

- Inconsistent findings regarding PV differences between same-sex subgroups

- Risk factors for LGBT groups include discrimination and internalized homophobia

Partner Abuse Worldwide

- A total of 162 articles reporting on over 200 studies met the inclusion criteria and were summarized in the online tables for Asia, the Middle East, Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, and Europe and the Caucasus.

- A total of 40 articles (73 studies) in 49 countries contained data on both male and female IPV, with a total of 117 direct comparisons across gender for physical PV.

- Rates of physical PV were higher for female perpetration /male victimization compared to male perpetration/female victimization, or were the same, in 73 of those comparisons, or 62%.

- There were 54 comparisons made for psychological abuse including controlling behaviors and dominance, with higher rates found for female perpetration /male victimization, in 36 comparisons (67%).

- Of the 19 direct comparisons made for sexual PV, rates were found to be higher for female perpetration /male victimization in 7comparisons (37%).

- When only adult samples from large population and community surveys were considered, the overall percentage of partner abuse that was higher for female perpetration /male victimization compared to male perpetration/female victimization, or were the same, was found to be 44% for adult IPV, although in many comparisons, the differences were slight.

- Studies reporting on female victimization only found the lowest rates for physical abuse victimization in a large population study in Georgia (2%, past year), and the highest in a community survey in Ethiopia (72.5% past year) On the higher end, rates of physical PV far exceed the average found in the United States.

- The lowest rates of psychological victimization were found in large population study in Haiti (10.8% past year); highest was 98.7% in Bangkok, Thailand (past year).

- Unlike physical IPV, the highest rates of psychological abuse throughout the world are about the same as those found in the United States (80%).

- Rates of sexual abuse victimization differed widely across regions, with rates as low as 1% in Georgia (past year); highest rates were found in a study of secondary school students in Ethiopia (68%, lifetime)

- Physical injuries were compared across gender in two studies. As expected, abused women were found to experience higher rates of physical injuries compared to men.

- Far more frequently mentioned were the psychological and behavioral effects of abuse, and these included PTSD symptomology, stress, depression, irritability, feelings of shame and guilt, poor self-esteem, flashbacks, sexual dissatisfaction and unwanted sexual behavior, changes in eating behavior, and aggression.

- Two studies compared mental health symptoms across gender. In Botswana, women were found to evidence significantly more of these than men; whereas in a clinical study in Pakistan male and female IPV victims suffered equally (60% of men and women reported depression, 67% anxiety.)

- A variety of health-related outcomes were also found to be associated with IPV victimization, including overall poor physical health, more long-term illnesses, having to take a larger number of prescribed drugs, STDs, and disturbed sleeping patterns. Abused mothers experienced poorer reproductive health, respiratory infections, induced abortion and complications during pregnancy; and in a few studies their children were found to experience diarrhea, fever and prolonged coughing.

- The most common risk factors found in this review of IPV in Asia, Africa, the Middle East, Latin America and Europe have also been found to be significant risk factors in the U.S. and other English-speaking industrialized nations.

- Most often cited are the risk factors related to low income household income and victim/perpetrator unemployment, at 36. An almost equally high number of studies (35) reported victim’s low education level. Alcohol and substance abuse by the perpetrator was a risk factor in 26 studies. Family of origin abuse, whether directly experienced or witnessed, was cited in 18 studies. Victim’s younger age was also a major risk factor, mentioned in 17 studies, and perpetrator’s low education level was mentioned in 16.

- In contrast to the U.S., there is a much higher tolerance by both men and women for IPV in other parts of the world, with rates of approval depending on the country and the type of justification.

- Regression analyses indicated that a country’s level of human development (as measured by HDI) was not a significant predictor of male or female physical partner abuse perpetration.

- Additional regression analyses indicated that a nation’s gender inequality level, as measured by the Gender Inequality Index (GII), was not predictive of either male or female perpetrated physical partner abuse or female-only victimization in studies conducted with general population or community samples.

- Separate regression analyses on data from the IDVS with dating samples indicate that higher gender inequality levels significantly predict higher prevalence of male and female physical partner abuse perpetration. GII level explained the variance for 17% of male partner abuse and 19% of female partner abuse perpetration.

- A final analysis examined the association between dominance by one partner and partner violence perpetrated against a partner in dating samples using data from the IDVS. Male dominance scores were not found to be predictive of male partner violence perpetration; however, female dominance scores explained 47% of the variance of female partner violence perpetration.

Facts and Statistics on The Role of Law Enforcement and the Criminal Justice System

The crime control effects of criminal sanctions.

- Possible causal mechanisms for the effectiveness of arrest and prosecution: fear of sanctions and victim empowerment; however, because none of the reviewed studies adequately measure such mechanisms, review assumes a general crime control effect that is neutral about causal mechanisms

- “Based upon the analyses and conclusions produced by these studies, we find that the most frequent outcome reported is that sanctions that follow an arrest for IPV have no effect on the prevalence of subsequent offending. Among the minority of reported analyses that do report a statistically significant effect, two-thirds of the published findings show sanctions are associated with reductions in repeat offending and one third show sanctions are associated with increased repeat offending.”

- Wide range of recidivism from 3.1% to 65.5% , due to high variability in measures of repeat offending (e.g., follow-up time frame)

- Studies unclear about then exact nature of the sentence imposed, and what constitutes a “prosecution” or “conviction”

- Diversity of analytic methods hinder analysis of effect sizes

- Sample selection bias: None of the studies address this issue; for instance, if a small number of low-risk cases are prosecuted, prosecuted offenders are more likely to re-offend compared to those not prosecuted, because of the selection process

- Missing data: Often leads to cases being dropped from a study, which in turns creates sample bias

Gender and Racial/Ethnic Differences in Criminal Justice Decision Making

- Female arrests affected by high SES, presence of weapons and witnesses

- Women more likely than men to be cited rather than be taken into custody, but the gender discrepancy is less when a decision is made on whether to file charges as misdemeanors or felonies

- Men are more likely than women to be convicted and to be given harsher sentences

- “Males were consistently treated more severely at every stage of the prosecution process, particularly regarding the decision to prosecute, even when controlling for other variables (e.g., the presence of physical injuries) and when examined under different conditions.”

- No conclusive evidence of discrimination against ethnic minority groups in either arrest, prosecution and sentencing

- Dual arrests were more likely in same-sex couples compared to heterosexual couples, perhaps due to incorrect assumption by police that same-sex couples more likely to engage in mutual violence.

- Protective orders far more likely to be granted, and with more restrictions to women than to men (particularly in cases involving less severe abuse histories)

- Mock juries more likely to assign blame responsibility to male perpetrators in contrast to female perpetrators, even when presented with identical scenarios

Effectiveness, Victim Safety, Characteristics and Enforcement of Protective Orders

- A large percentage of women who are issued protective orders (POs) tend to be unemployed or under-employed as income ranged between $10,000 to $15,000, and almost 50% of women are financially dependent on their partners.

- At least half of women obtaining POs are married, and married women are more likely to stay with their abusers and be pregnant.

- Women who are issued POs tend to have more mental health issues (i.e., depression, PTSD) and rural women tend to experience more abuse and mental health issues than urban women

- Only a few studies have examined characteristics of men seeking a PO

- “Effectiveness” defined as violations of protective orders (POs) and/or re-victimization

- Some studies have found POs to reduce violence against victims, with an almost 80% reduction in violence reported to police

- Victims report feeling safer and having greater psychological well-being after obtaining a protective order; still, POs violated at a rate of between 44% to 70%

- Nearly 60% of women who had secured a PO reported to have subsequently been stalked

- Severity of criminal charges on the offender, as well as previous violations, best predictors of new PO violations

- Although there is no significant difference in the amount of abuse suffered by married and unmarried victims, married victims less likely to seek final protective orders, perhaps because they are more likely to be re-victimized

- Women granted POs at significantly higher rates than men, especially in cases involving lower level violence

- No gender differences in the enforcement of POs, and no differences in rates of recidivism

Facts and Statistics on Assessment and Treatment

Risk assessment.

- Little agreement in the literature with regard to the most appropriate approach (actuarial, structured clinical judgment) nor which specific measure has the strongest empirical validation behind it, leaving clinicians and policy makers with little clear guidance

- Review yielded studies reporting on the validity and reliability of eight IPV specific actuarial instruments and three general actuarial risk assessment measures.

- Range of area under the curve (AUC) values reported for the validity of the Ontario Domestic Assault Risk Assessment (ODARA) predicting recidivism was good to excellent (0.64 – 0.77)

- The single study that reported on the Domestic Violence Risk Appraisal Guide (DVRAG) reported an AUC = 0.70 (p < .001). The inter-rater reliability for both instruments was excellent

- The Domestic Violence Screening Inventory (DVSI) and Domestic Violence Screening Inventory – Revised (DVSI-R) were found to be good predictors of new family violence incidents and IPV recurrence (AUC range 0.61 – 0.71)

- Three studies examined the Psychopathy Checklist – Revised (PCL-R) and Violence Risk Appraisal Guide (VRAG), neither of which are IPV specific, reporting AUCs ranging from 0.66 – 0.71 and 0.67 – 0.75, respectively.

- The Level of Service Inventory – Revised (LSI-R) and Level of Service Inventory – Ontario Revision (LSI-OR) were discussed in four articles, reporting two AUC values of 0.50 and 0.73, both of which were predicting IPV recidivism