The New York Times

The learning network | are anonymous social media networks dangerous.

Are Anonymous Social Media Networks Dangerous?

Questions about issues in the news for students 13 and older.

- See all Student Opinion »

How often do you read or post in anonymous online social media forums? Why do you think they are so popular? Do you think that kind of online anonymity can be dangerous? Why or why not?

In “Who Spewed That Abuse? Anonymous Yik Yak App Isn’t Telling,” Jonathan Mahler writes:

During a brief recess in an honors course at Eastern Michigan University last fall, a teaching assistant approached the class’s three female professors. “I think you need to see this,” she said, tapping the icon of a furry yak on her iPhone. The app opened, and the assistant began scrolling through the feed. While the professors had been lecturing about post-apocalyptic culture, some of the 230 or so freshmen in the auditorium had been having a separate conversation about them on a social media site called Yik Yak. There were dozens of posts, most demeaning, many using crude, sexually explicit language and imagery. After class, one of the professors, Margaret Crouch, sent off a flurry of emails — with screenshots of some of the worst messages attached — to various university officials, urging them to take some sort of action. “I have been defamed, my reputation besmirched. I have been sexually harassed and verbally abused,” she wrote to her union representative. “I am about ready to hire a lawyer.” In the end, nothing much came of Ms. Crouch’s efforts, for a simple reason: Yik Yak is anonymous. There was no way for the school to know who was responsible for the posts. Eastern Michigan is one of a number of universities whose campuses have been roiled by offensive “yaks.” Since the app was introduced a little more than a year ago, it has been used to issue threats of mass violence on more than a dozen college campuses, including the University of North Carolina, Michigan State University and Penn State. Racist, homophobic and misogynist “yaks” have generated controversy at many more, among them Clemson, Emory, Colgate and the University of Texas. At Kenyon College, a “yakker” proposed a gang rape at the school’s women’s center. In much the same way that Facebook swept through the dorm rooms of America’s college students a decade ago, Yik Yak is now taking their smartphones by storm. Its enormous popularity on campuses has made it the most frequently downloaded anonymous social app in Apple’s App Store, easily surpassing competitors like Whisper and Secret. At times, it has been one of the store’s 10 most downloaded apps. Like Facebook or Twitter, Yik Yak is a social media network, only without user profiles. It does not sort messages according to friends or followers but by geographic location or, in many cases, by university. Only posts within a 1.5-mile radius appear, making Yik Yak well suited to college campuses. Think of it as a virtual community bulletin board — or maybe a virtual bathroom wall at the student union. It has become the go-to social feed for college students across the country to commiserate about finals, to find a party or to crack a joke about a rival school. Much of the chatter is harmless. Some of it is not. “Yik Yak is the Wild West of anonymous social apps,” said Danielle Keats Citron, a law professor at University of Maryland and the author of “Hate Crimes in Cyberspace.” “It is being increasingly used by young people in a really intimidating and destructive way.”

Students: Read the entire article, then tell us …

— Have you used Yik Yak, Whisper, Secret or other anonymous social media networks? What have you noticed about the posts there? Why do you think people are so attracted to this kind of anonymity?

— How different do you think people are when they post anonymously than when their names are attached to their posts? What are the benefits and drawbacks of social media anonymity? How, for example, do you think personal expression on a network like Yik Yak compares and contrasts with personal expression on one like Facebook?

— Have you ever been offended by something posted online anonymously? What did you do?

— Are you more sympathetic to the arguments made in this article that networks like Yik Yak can be destructive and should, where possible, be restricted for young people, or are you more sympathetic to those who argue that restricting them curtails freedom of speech? Why?

— How do your own anonymous posts online compare with those you post under your real name? Why?

Students 13 and older are invited to comment below. Please use only your first name. For privacy policy reasons, we will not publish student comments that include a last name.

Comments are no longer being accepted.

I think that social media networks like Yik Yak, Whisper, and Secret should be taken down and out of existence. Although I have never used any of these social media networks myself based on the information given they aren’t being used for good purposes. Therefore they should just be deleted.

(I believe that Yik Yak is a good website for students and random people to express their thoughts to the world, but Yik Yak does have its downside with bad messages like threats and other situations that can put pressure on people which can lead to very large problems.)

Anonymous post online are different from posts under someones real name because you don’t know who you’re talking to. As an example I could be speaking to a drug dealer and I wouldn’t even know it, as if I were to be speaking to a drug dealer but then I would know because of his post, name, and friends. Having a anonymous account is dangerous it can bring many problems to us.

i have never used any social media sites that needs you to be anonymous i think when people do post on anonymous websites they feel like they can say what ever they want and be as mean as they want because no one knows who they are.

Anonymous Social Media Networks are dangerous. They are dangerous because you don’t really know who you are talking to. Also, because its anonymous people can get away with bullying. Which then leads to a lot of other stuff, like racism, and verbal abuse.

Social networks are becoming increasingly popular and is a way to communicate with others. Sometimes it can be used to hurt others. Online anonymity can be dangerous because it allows people to threaten, discriminate, and demean against each other and there is no way to trace it back. There will be no repercussions to face and no one will be able to deliver justice.

Yik Yak is a app that allows people to express things that they couldn’t on usual social medias. Also , people get attracted to new things that let them have a way of freedom , able to speak for themselves which is following there first amendment right .People may think that when they post anonymously they feel as if they can speak there mind and it won’t be a big deal, however , when there names are attached to the post they feel as if they know people are watching them and to know that they may get reported for things that may cause controversy .Yes , Yik Yak does have a personal expression the same as facebook does .No , I have never been offended by the comments because I never used the app and I don’t plan on using it .Yes , there are sympathetic arguments that can be made about destructing the app and should.

We had an issue with Yik Yak at our High School, people bullying certain social groups, etc., this was a student led response.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0nWUewy6eTQ

Local News Coverage: //www.denverpost.com/news/ci_27216163/cherry-creek-high-school-students-launch-anti-stereotype

I don’t think they are, if people just want to rant or let something out, those websites are helpful, because they can say whatever they want without it being reported by someone who doesn’t know their name. I know if I wanted to rant or let something out, I would use one of those websites, instead of a journal, because then I would know people would be reading it, and maybe just maybe some people are feeling the way I am.

I have not used Yik Yak, Whisper, or Secret. I do know about these anonymous apps though and the things I tend to hear is disturbing at times and some of them are funny. Many people are attracted to this because even though their voice is not heard on other social media apps, their voices can be heard without being known. And nobody will know about it too so it won’t get them into trouble at most times. I feel like people write a lot different when their names are attached to their social media accounts than when they are anonymous. A lot of people will usually write positive things with their names attached but anonymously they write disturbing things. Some benefits is that you won’t be known but a drawback is that you won’t be known. For example you may like a guy/girl and in person or on social media with your names, you feel shy, but anonymously, you would feel more comfortable so you would say something nice about that guy or girl without being known. But, some drawbacks are that in a critical moment, or for example, if someone gives a threat or states that he or she will carry out a violent act, then you won’t know who it is in an anonymous social media app. Therefore, it will be hard to stop the act or to find out and make charges. I have been offended because there were some instances where these people said racist jokes about my nationality. And pointed it not only to me but my other friends who share the same nationality.

I have used Yik Yak before but I’ve never even heard of Whisper or Secret until I read this article. My high school had a short lived obsession with the Yik Yak which didn’t last longer than two weeks maximum. I didn’t post a lot of Yaks, I used the app mostly to see what everyone else was talking about and figure out why they thought the app was so great. Some of the posts were funny, people tell jokes and shout out their friends. But others are unbelievably mean, people would rant about how much they hated someone else and say terrible things about them. People are attracted to the anonymity because it lets them say what they think of a person without ever having to face the victim they’ve lashed out at. They have no consequence and can say whatever they want, spread rumors, tell secrets, and ruin friendships and never get caught. When someone has their name attached to something they post on the internet, they behave socially acceptable because anything they say could be traced back to them. Yik Yak was originally created for college kids so younger kids shouldn’t even be on the app. Therefore, no restrictions should be made since the little kids aren’t supposed to know about it. I do however think you should be asked your age when you download it from the app store. I have personally never been offended by anything written online but I could easily see how someone would get offended. The comments made are so nasty and they could come from anyone, your best friend or someone you’ve never spoken a word to a day in your life. The worst part about it is not only that everyone else can see the comment, but that you’ll always wonder who posted it.

In the article “Are Anonymous Social Media Networks Dangerous?” it discusses the problems cause by social media apps on college campuses. I have used the app “Yik Yak” before, but shortly asked, by my coach, to delete it after finding offensive “yaks” about my teammates. I mostly noticed people just writing someone’s name and waiting for comments back, usually mean, and then causing a fight. I think people find these types of apps amusing because, no one can ever find out it is you saying that nasty comment you could never “tweet”, but still get a reaction out of people. People’s comments change when they know their name is on it, it used to be “You’ll say it online, but not your face,” or “You’re hiding behind your computer.” These apps have taken that to a whole new level, you could say something so mean and not have to worry about someone personally yelling at you in school the next day. Ultimately, it gets rid of any conscience that comes with talking bad about someone. I do think that these apps such as “Whisper” and “Yik Yak” have been made for a good reason, and not the negative. For example, someone can anonymously say where a party is that night, and not get yelled at for “blowing it up.” It can also be used to compliment someone, without using vulgar language. I think Yik Yak should be monitored better, and get rid of nasty things said. I’m all about the 1st amendment, but when its hurting people as bad as the teacher in the article, it isn’t fair. In my school they have blocked Yik Yak from our service, which makes it harder for people to be mean. For example: You see someone do something weird in school and think “wow I can’t wait to yak that later when I get home,” by the time you get home the yak has usually left your mind and is irrelevant. There will always be people who turn something great into something evil.

Yik Yak is a great way to tell something inspiring, funny or interesting anonymously. Sadly, they are not used for these purposes. Social medias like YIk Yak should be removed from every device, or at least have some sort of moderation. Yik Yak may eventually turn into something like 4chan, and we all know how 4chan turned out.

I believe that social media can be a good thing for kids but not always. Thats why there are age restictions on all social media cites, but not every one follows them. I am one of those people because age restrictions,put limits on what we can do and I think its stupid Yes its good for five year olds and they dont know what they are doing. If your one there for your friends and to share your life.. like snapchat, instagram, twitter, and facebook (even though nobody uses that).

I personally think that this is what the internet is for. Some bad people are on Facebook. Why don’t we just take FB down then? Or Instagram? Or Youtube? Lets just shut down the internet basically. Despite what they tell you in anti-bullying commercials, anonymity on the web does exist, and is actually very easy to obtain.

Honestly, I don’t think this is appropriate. We were given social media sites to express ourselves and share our feelings. I don’t use any social media sites,I know some of my friends do,and of course they like and favorite and post funny comments. However,I know for sure that they do not post ugly comments. The way that these students abused Yik Yak is terrible and I feel very bad for what has been done to these teachers.

I have next to no experience with anonymous social media, or any kind of social media at all, but I do have some experience with things like Quotev. (which is all I have other than this) I do have experience with bullying (from other sources, I do not bully)

When you post something on social media you should always show who you are. most people that don’t show who they are usually do that because they don’t want to show who they are (that’s obvious but still), also so they can get away with more than the average person can that shows who they are. I have never used Yik Yak but I probably wouldn’t because I like people to know who I am. I think it is a bad idea to have an anonymous website.

I believe that Yik Yak should take the really really bad comments, and have a moderator to throw the comment out. Yik Yak has a great purpose, but geniuses abuse their power on the site. Take those comments out, but the app has a good intention.

In a life of social media, there is ignorance and hate sliding through the cracks of social sites. Anyone can be mostly anonymous on social medias even if it is one where you have to have an account. I Don’t see why people complain about having apps like Yik Yak and Whisper, even though sites like Facebook and Twitter can have people acting like other people. In my eyes are more dangerous and secretive than people being themselves but not posting a name instead of trying to show yourself as someone who you aren’t.

I agree with kylemcm7th

Anonymous apps have created much controversy. Kids and even sometimes childish adults go on these apps and say awful things that they are too much of a coward to say to someones face. Anonymous apps cant be controlled because no one knows whose saying these controversial statements. The only way to stop this is take down these anonymous sites. These sites are unnecessary so we may as well just take them down. If someone really needs to tell a weird fetish they can tell a friend. If someone has something rude to say about somebody they can say it to their face if its that necessary to get out. If someone needs to tell a secret they can tell someone close. These apps have no good purposes so why not just get rid of them?

I have not ever used apps like Yik Yak, Whisper or Secret, but I have only seen and heard good things abut them. I have seen a variety of posts on it, and they mostly seem to be interesting or humorous, never, in my experience, hateful or derogatory. The anonymity of these apps seems like it would change the popular usage of them, but it doesn’t seem to do so. People still post things they would be okay posting under a name, and mainly seem attracted to, in particular, Yik Yak because of its location-based content. People who post anonymously may be much more vulgar, but they are also potentially much more outgoing than they would be if they could be identified by their opinions. I do not fully agree with the arguments in the article. They overshadow the possibility for discussion because the discussion is not what they wish it could be. Some people may use social media to harass people, but these people are only a small fragment of the entire Yik Yak “body.”

Personally, I have never used any of the anonymous social networking sites. I do agree, however, that these can potentially be dangerous if used for harm. People probably use these types of sites because they can voice their opinion without getting in trouble. Making these sites stricter could restrict freedom of speech, but these people shouldn’t be using these types of sites to say harmful things to others or to threaten others.

Social media, just not anonymous media, is a good thing for expressing feelings and sharing cool or funny things. If a person wants to shout about their bad day into the void of the web, they should. However, with pretty much all interactions, there is a line that can be crossed. The instances in the article, including threats of mass violence and proposed gang rape, are extremely just not okay. If somebody went on Yik Yak or another anonymous communication medium and engage in harmless banter about a rival organization, that’s okay; if somebody went on the same medium and threatened to bomb a school, they should be reprimanded as that is quite wrong. Basically, social media, anonymous or not, is a double edged sword. It can be used for good or bad. It’s okay to spread jokes, funny pictures, or stories, but once threats of violence and other harmful transgressions are made, actions should be taken to purge the medium or site of acute negativity.

Anonymous social media sites are made for one reason- harassment. People think if they are hidden, they will not get in trouble. Unfortunately, the people on Yik Yak are getting lucky. If UNC at Chapel Hill wanted to, they could put all the students in a room and interrogate them. I would have done that until someone talked, then I would get them in trouble. These students did not think about what they were saying or the possible consequences. Although I dislike the Democrats philosophy, and I believe in the freedom of speech, these students need to watch their thoughts and where they go.

What's Next

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

- Anonymity, Privacy, and Security Online

Table of Contents

- Part 1: The Quest for Anonymity Online

- Part 2: Concerns About Personal Information Online

- Part 3: Who Internet Users are Trying to Avoid; the Information They Want to Protect

- Part 4: How Users Feel About the Sensitivity of Certain Kinds of Data

- Part 5: Online Identity Theft, Security Issues, and Reputational Damage

Anonymity online

Most internet users would like to be anonymous online at least occasionally, but many think it is not possible to be completely anonymous online. New findings in a national survey show:

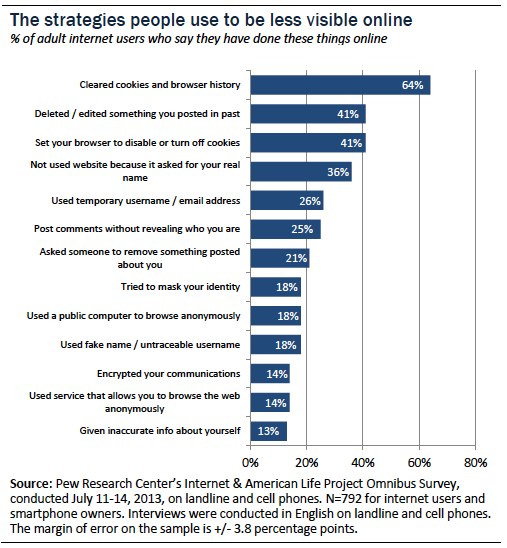

- 86% of internet users have taken steps online to remove or mask their digital footprints—ranging from clearing cookies to encrypting their email, from avoiding using their name to using virtual networks that mask their internet protocol (IP) address.

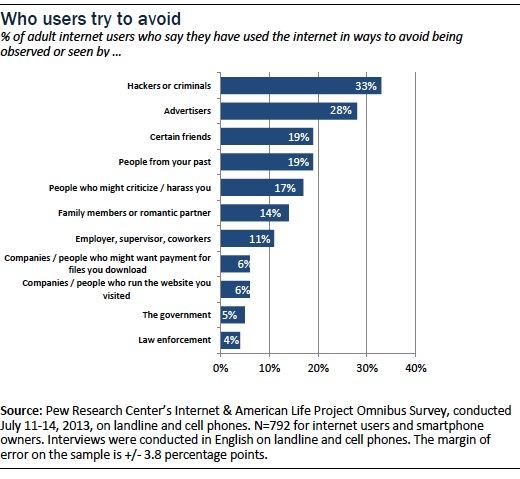

- 55% of internet users have taken steps to avoid observation by specific people, organizations, or the government

Still, 59% of internet users do not believe it is possible to be completely anonymous online, while 37% of them believe it is possible.

A section of the survey looking at various security-related issues finds that notable numbers of internet users say they have experienced problems because others stole their personal information or otherwise took advantage of their visibility online—including hijacked email and social media accounts, stolen information such as Social Security numbers or credit card information, stalking or harassment, loss of reputation, or victimization by scammers.

- 21% of internet users have had an email or social networking account compromised or taken over by someone else without permission.

- 13% of internet users have experienced trouble in a relationship between them and a family member or a friend because of something the user posted online.

- 12% of internet users have been stalked or harassed online.

- 11% of internet users have had important personal information stolen such as their Social Security Number, credit card, or bank account information.

- 6% of internet users have been the victim of an online scam and lost money.

- 6% of internet users have had their reputation damaged because of something that happened online.

- 4% of internet users have been led into physical danger because of something that happened online.

- 1% of internet users have lost a job opportunity or educational opportunity because of something they posted online or someone posted about them.

Some 68% of internet users believe current laws are not good enough in protecting people’s privacy online and 24% believe current laws provide reasonable protections.

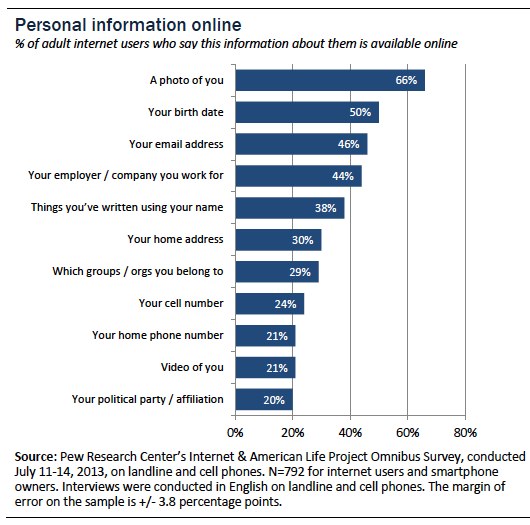

Most internet users know that key pieces of personal information about them are available online—such as photos and videos of them, their email addresses, birth dates, phone numbers, home addresses, and the groups to which they belong. And growing numbers of internet users (50%) say they are worried about the amount of personal information about them that is online—a figure that has jumped from 33% who expressed such worry in 2009.

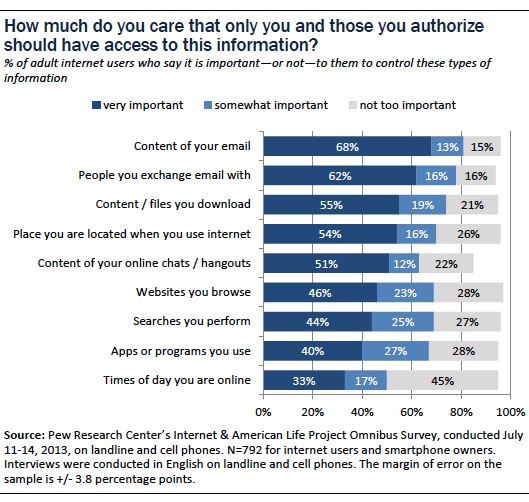

People would like control over their information, saying in many cases it is very important to them that only they or the people they authorize should be given access to such things as the content of their emails, the people to whom they are sending emails, the place where they are when they are online, and the content of the files they download.

About this survey

This survey by the Pew Research Center’s Internet Project was underwritten by Carnegie Mellon University. The findings in this report are based on data from telephone interviews conducted by Princeton Survey Research Associates International from July 11-14, among a sample of 1,002 adults ages 18 and older. Telephone interviews were conducted in English by landline and cell phone. For results based on the total sample, one can say with 95% confidence that the error attributable to sampling is plus or minus 3.4 percentage points and for the results from 792 internet and smartphone users in the sample, the margin of error is 3.8 percentage points. More information is available in the Methods section at the end of this report.

A closer look at key findings

86% of internet users have tried to use the internet in ways to minimize the visibility of their digital footprints

The chart below shows the variety of ways that internet users have tried to avoid being observed online.

55% of internet users have taken steps to hide from specific people or organizations

Beyond their general hope that they can go online anonymously, the majority of internet users have tried to avoid observation by other people, groups, companies, and government agencies. Hackers, criminals and advertisers are at the top of the list of groups people wish to avoid.

Users report that a wide range of their personal information is available online, but feel strongly about controlling who has access to certain kinds of behavioral data and communications content.

Users know that there is a considerable amount of personal information about them available online. Among the list of items queried, photos were the most commonly reported content posted online; 66% of internet users reported that an image of them was available online. And half (50%) say that their birth date is available.

Another set of questions focused on the kinds of “data exhaust” that is generated as a result of everyday forms of online communications, web surfing and application use. Respondents were asked how much they cared “that only you and those you authorize should have access” to certain kinds of behavioral data and communications content and there was notable variance in the answers. The content of email messages and the people with whom one communicates via email are considerably more sensitive pieces of information when compared with other online activities and associated data trails.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Online Harassment & Bullying

- Online Privacy & Security

- Platforms & Services

- Privacy Rights

- Social Media

Teens and Video Games Today

9 facts about bullying in the u.s., life on social media platforms, in users’ own words, after musk’s takeover, big shifts in how republican and democratic twitter users view the platform, teens and cyberbullying 2022, most popular.

901 E St. NW, Suite 300 Washington, DC 20004 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

© 2024 Pew Research Center

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence

The Many Shades of Anonymity: Characterizing Anonymous Social Media Content

February 1, 2023

Denzil Correa,Leandro Silva,Mainack Mondal,Fabrício Benevenuto,Krishna Gummadi

Max Planck Institute for Software Systems (MPI-SWS),Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG),Max Planck Institute for Software Systems (MPI-SWS),Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG),Max Planck Institute for Software Systems (MPI-SWS)

Proceedings:

Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, 9

Vol. 9 No. 1 (2015): Ninth International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media

Full Papers

Recently, there has been a significant increase in the popularity of anonymous social media sites like Whisper and Secret. Unlike traditional social media sites like Facebook and Twitter, posts on anonymous social media sites are not associated with well defined user identities or profiles. In this study, our goals are two-fold: (i) to understand the nature (sensitivity, types) of content posted on anonymous social media sites and (ii) to investigate the differences between content posted on anonymous and non-anonymous social me- dia sites like Twitter. To this end, we gather and analyze ex- tensive content traces from Whisper (anonymous) and Twitter (non-anonymous) social media sites. We introduce the notion of anonymity sensitivity of a social media post, which captures the extent to which users think the post should be anonymous. We also propose a human annotator based methodology to measure the same for Whisper and Twitter posts. Our analysis reveals that anonymity sensitivity of most whispers (unlike tweets) is not binary. Instead, most whispers exhibit many shades or different levels of anonymity. We also find that the linguistic differences between whispers and tweets are so significant that we could train automated classifiers to distinguish between them with reasonable accuracy. Our findings shed light on human behavior in anonymous media systems that lack the notion of an identity and they have important implications for the future designs of such systems.

10.1609/icwsm.v9i1.14635

Privacy Overview

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

- Israel-Gaza War

- War in Ukraine

- US Election

- US & Canada

- UK Politics

- N. Ireland Politics

- Scotland Politics

- Wales Politics

- Latin America

- Middle East

- In Pictures

- Executive Lounge

- Technology of Business

- Women at the Helm

- Future of Business

- Science & Health

- Artificial Intelligence

- AI v the Mind

- Film & TV

- Art & Design

- Entertainment News

- Destinations

- Australia and Pacific

- Caribbean & Bermuda

- Central America

- North America

- South America

- World’s Table

- Culture & Experiences

- The SpeciaList

- Natural Wonders

- Weather & Science

- Climate Solutions

- Sustainable Business

- Green Living

The danger of online anonymity

Stephen Pickhardt noticed a disturbing trend on the review page for his walking-tour business a couple of years ago. All of a sudden, with no warning or change in the way he operated his tours, reviews from customers on an influential travel website turned negative.

This was something new for Pickhardt. Since founding Free Tours by Foot in 2007, offering pay-what-you-like tours in nine cities, including Berlin, London and New York City, he had received only the occasional bad review. But the review page for his New Orleans tour was suddenly inundated with negative comments.

“They were so, so bad,” Pickhardt said from his office in Washington, DC. “They accused us of taking people down dark alleys, of strong-arming people.” Pickhardt knew the stories weren’t true.

He researched the writer of the reviews online and quickly discovered that the fake logins to the travel site were all linked to the same personal Facebook profile. The profile was for a staff member of a rival firm.

Once the problem was flagged, the well-known website removed the reviews. There’s no telling if Pickhardt lost business but it bothers him that a competitor would stoop so low.

“Don’t get me wrong, I do understand the motivation to pad reviews or bash your competitor,” Pickhardt said. “But I don’t think people have thought this through. They haven’t realised that this is morally objectionable.”

Truth is, what is allowed and what’s immoral in business has become harder to define. Technology has made it more difficult for managers to set limits on what employees can do for the business to stay competitive.

While padding online reviews has spawned countless libel lawsuits, how many people would be dragged before a judge after they verbally bashed a competitor? Technology has allowed for new forms of unethical behaviour. At the same time, laws and ethical guidelines simply haven’t kept up with the advancements in technology, said David Wasieleski, associate professor of business ethics at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

This leaves managers in a difficult situation; there are no accepted norms to fall back on to decide a line their employees shouldn’t cross. More often than not, Wasieleski said, the answer is transparency. Bosses need to ask themselves: What would the reaction be if the world found out what’s happening behind their company’s walls?

Technology and anonymity

Technology makes transparency even more important because studies show people are more likely to behave in a dishonest or morally questionable way when they can hide behind it. A research paper Wasieleski co-authored in 2012 revealed that students cheat more often when technology makes it possible. The internet especially gives people the feeling of anonymity, as if they can get away with it without anybody knowing who did it.

Proximity also makes a difference. People are less likely to behave badly when their victims are nearby, Wasieleski said. The web, of course, does a good job of making people feel far away from one another, and thus makes people more likely attack strangers online who might be on the other side of the globe.

It’s up to managers and business owners to write ethical guidelines that can be applied to any situation, said Muel Kaptein, professor of business ethics and integrity management at Rotterdam School of Management in the Netherlands. It’s not enough for bosses to expect employees to just figure things out. In other words, people are more likely to do bad things if others in the company are doing them too and there is no set policy in place to dictate what is appropriate or not.

“As part of many organisations, good people will lose their morality or forget their morality for a while,” said Kaptein, author of the book Why Do Good People Sometimes Do Bad Things? “People think: it’s not my responsibility to decide what’s right, and if the organisation decided it’s okay, then I will do it.”

Part of the problem is that lower-level employees in big corporations often feel like there’s nothing they could do to address the company’s moral lapses. And it’s those frontline workers who will often deal with the new issues brought about by technological advances.

“When faced with a new moral dilemma, managers need to pick their battles and decide what to bring to upper management,” Kaptein said. “But it’s also their responsibility to try to fix the big ones.”

The lesson Pickhardt has learned from his experience is that he must carefully monitor all of the review sites for each of his locations. While this is a great deal of extra work he knows watching out for fake reviews and responding to feedback has simply become part of staying competitive in the travel industry.

“Everyone is padding reviews to get to the top,” Pickhardt said. “A few good reviews can bring you up from the bottom to in the top three, and a few bad ones might knock you off. So there is a built-in incentive to being dishonest.”

Pickhardt admits that while there’s a temptation to write a false review to gain competitive advantage, doing so requires accepting a new moral footing, to accept that it’s OK to be untruthful on the web. It’s a step he isn’t willing to take.

“On the internet, people think it doesn’t matter what they say because they’re just screaming into the wind,” Pickhardt said. “But you also have to ask yourself if this is something you should be doing.”

To comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Capital, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter .

Find anything you save across the site in your account

How Harmful Is Social Media?

In April, the social psychologist Jonathan Haidt published an essay in The Atlantic in which he sought to explain, as the piece’s title had it, “Why the Past 10 Years of American Life Have Been Uniquely Stupid.” Anyone familiar with Haidt’s work in the past half decade could have anticipated his answer: social media. Although Haidt concedes that political polarization and factional enmity long predate the rise of the platforms, and that there are plenty of other factors involved, he believes that the tools of virality—Facebook’s Like and Share buttons, Twitter’s Retweet function—have algorithmically and irrevocably corroded public life. He has determined that a great historical discontinuity can be dated with some precision to the period between 2010 and 2014, when these features became widely available on phones.

“What changed in the 2010s?” Haidt asks, reminding his audience that a former Twitter developer had once compared the Retweet button to the provision of a four-year-old with a loaded weapon. “A mean tweet doesn’t kill anyone; it is an attempt to shame or punish someone publicly while broadcasting one’s own virtue, brilliance, or tribal loyalties. It’s more a dart than a bullet, causing pain but no fatalities. Even so, from 2009 to 2012, Facebook and Twitter passed out roughly a billion dart guns globally. We’ve been shooting one another ever since.” While the right has thrived on conspiracy-mongering and misinformation, the left has turned punitive: “When everyone was issued a dart gun in the early 2010s, many left-leaning institutions began shooting themselves in the brain. And, unfortunately, those were the brains that inform, instruct, and entertain most of the country.” Haidt’s prevailing metaphor of thoroughgoing fragmentation is the story of the Tower of Babel: the rise of social media has “unwittingly dissolved the mortar of trust, belief in institutions, and shared stories that had held a large and diverse secular democracy together.”

These are, needless to say, common concerns. Chief among Haidt’s worries is that use of social media has left us particularly vulnerable to confirmation bias, or the propensity to fix upon evidence that shores up our prior beliefs. Haidt acknowledges that the extant literature on social media’s effects is large and complex, and that there is something in it for everyone. On January 6, 2021, he was on the phone with Chris Bail, a sociologist at Duke and the author of the recent book “ Breaking the Social Media Prism ,” when Bail urged him to turn on the television. Two weeks later, Haidt wrote to Bail, expressing his frustration at the way Facebook officials consistently cited the same handful of studies in their defense. He suggested that the two of them collaborate on a comprehensive literature review that they could share, as a Google Doc, with other researchers. (Haidt had experimented with such a model before.) Bail was cautious. He told me, “What I said to him was, ‘Well, you know, I’m not sure the research is going to bear out your version of the story,’ and he said, ‘Why don’t we see?’ ”

Bail emphasized that he is not a “platform-basher.” He added, “In my book, my main take is, Yes, the platforms play a role, but we are greatly exaggerating what it’s possible for them to do—how much they could change things no matter who’s at the helm at these companies—and we’re profoundly underestimating the human element, the motivation of users.” He found Haidt’s idea of a Google Doc appealing, in the way that it would produce a kind of living document that existed “somewhere between scholarship and public writing.” Haidt was eager for a forum to test his ideas. “I decided that if I was going to be writing about this—what changed in the universe, around 2014, when things got weird on campus and elsewhere—once again, I’d better be confident I’m right,” he said. “I can’t just go off my feelings and my readings of the biased literature. We all suffer from confirmation bias, and the only cure is other people who don’t share your own.”

Haidt and Bail, along with a research assistant, populated the document over the course of several weeks last year, and in November they invited about two dozen scholars to contribute. Haidt told me, of the difficulties of social-scientific methodology, “When you first approach a question, you don’t even know what it is. ‘Is social media destroying democracy, yes or no?’ That’s not a good question. You can’t answer that question. So what can you ask and answer?” As the document took on a life of its own, tractable rubrics emerged—Does social media make people angrier or more affectively polarized? Does it create political echo chambers? Does it increase the probability of violence? Does it enable foreign governments to increase political dysfunction in the United States and other democracies? Haidt continued, “It’s only after you break it up into lots of answerable questions that you see where the complexity lies.”

Haidt came away with the sense, on balance, that social media was in fact pretty bad. He was disappointed, but not surprised, that Facebook’s response to his article relied on the same three studies they’ve been reciting for years. “This is something you see with breakfast cereals,” he said, noting that a cereal company “might say, ‘Did you know we have twenty-five per cent more riboflavin than the leading brand?’ They’ll point to features where the evidence is in their favor, which distracts you from the over-all fact that your cereal tastes worse and is less healthy.”

After Haidt’s piece was published, the Google Doc—“Social Media and Political Dysfunction: A Collaborative Review”—was made available to the public . Comments piled up, and a new section was added, at the end, to include a miscellany of Twitter threads and Substack essays that appeared in response to Haidt’s interpretation of the evidence. Some colleagues and kibbitzers agreed with Haidt. But others, though they might have shared his basic intuition that something in our experience of social media was amiss, drew upon the same data set to reach less definitive conclusions, or even mildly contradictory ones. Even after the initial flurry of responses to Haidt’s article disappeared into social-media memory, the document, insofar as it captured the state of the social-media debate, remained a lively artifact.

Near the end of the collaborative project’s introduction, the authors warn, “We caution readers not to simply add up the number of studies on each side and declare one side the winner.” The document runs to more than a hundred and fifty pages, and for each question there are affirmative and dissenting studies, as well as some that indicate mixed results. According to one paper, “Political expressions on social media and the online forum were found to (a) reinforce the expressers’ partisan thought process and (b) harden their pre-existing political preferences,” but, according to another, which used data collected during the 2016 election, “Over the course of the campaign, we found media use and attitudes remained relatively stable. Our results also showed that Facebook news use was related to modest over-time spiral of depolarization. Furthermore, we found that people who use Facebook for news were more likely to view both pro- and counter-attitudinal news in each wave. Our results indicated that counter-attitudinal exposure increased over time, which resulted in depolarization.” If results like these seem incompatible, a perplexed reader is given recourse to a study that says, “Our findings indicate that political polarization on social media cannot be conceptualized as a unified phenomenon, as there are significant cross-platform differences.”

Interested in echo chambers? “Our results show that the aggregation of users in homophilic clusters dominate online interactions on Facebook and Twitter,” which seems convincing—except that, as another team has it, “We do not find evidence supporting a strong characterization of ‘echo chambers’ in which the majority of people’s sources of news are mutually exclusive and from opposite poles.” By the end of the file, the vaguely patronizing top-line recommendation against simple summation begins to make more sense. A document that originated as a bulwark against confirmation bias could, as it turned out, just as easily function as a kind of generative device to support anybody’s pet conviction. The only sane response, it seemed, was simply to throw one’s hands in the air.

When I spoke to some of the researchers whose work had been included, I found a combination of broad, visceral unease with the current situation—with the banefulness of harassment and trolling; with the opacity of the platforms; with, well, the widespread presentiment that of course social media is in many ways bad—and a contrastive sense that it might not be catastrophically bad in some of the specific ways that many of us have come to take for granted as true. This was not mere contrarianism, and there was no trace of gleeful mythbusting; the issue was important enough to get right. When I told Bail that the upshot seemed to me to be that exactly nothing was unambiguously clear, he suggested that there was at least some firm ground. He sounded a bit less apocalyptic than Haidt.

“A lot of the stories out there are just wrong,” he told me. “The political echo chamber has been massively overstated. Maybe it’s three to five per cent of people who are properly in an echo chamber.” Echo chambers, as hotboxes of confirmation bias, are counterproductive for democracy. But research indicates that most of us are actually exposed to a wider range of views on social media than we are in real life, where our social networks—in the original use of the term—are rarely heterogeneous. (Haidt told me that this was an issue on which the Google Doc changed his mind; he became convinced that echo chambers probably aren’t as widespread a problem as he’d once imagined.) And too much of a focus on our intuitions about social media’s echo-chamber effect could obscure the relevant counterfactual: a conservative might abandon Twitter only to watch more Fox News. “Stepping outside your echo chamber is supposed to make you moderate, but maybe it makes you more extreme,” Bail said. The research is inchoate and ongoing, and it’s difficult to say anything on the topic with absolute certainty. But this was, in part, Bail’s point: we ought to be less sure about the particular impacts of social media.

Bail went on, “The second story is foreign misinformation.” It’s not that misinformation doesn’t exist, or that it hasn’t had indirect effects, especially when it creates perverse incentives for the mainstream media to cover stories circulating online. Haidt also draws convincingly upon the work of Renée DiResta, the research manager at the Stanford Internet Observatory, to sketch out a potential future in which the work of shitposting has been outsourced to artificial intelligence, further polluting the informational environment. But, at least so far, very few Americans seem to suffer from consistent exposure to fake news—“probably less than two per cent of Twitter users, maybe fewer now, and for those who were it didn’t change their opinions,” Bail said. This was probably because the people likeliest to consume such spectacles were the sort of people primed to believe them in the first place. “In fact,” he said, “echo chambers might have done something to quarantine that misinformation.”

The final story that Bail wanted to discuss was the “proverbial rabbit hole, the path to algorithmic radicalization,” by which YouTube might serve a viewer increasingly extreme videos. There is some anecdotal evidence to suggest that this does happen, at least on occasion, and such anecdotes are alarming to hear. But a new working paper led by Brendan Nyhan, a political scientist at Dartmouth, found that almost all extremist content is either consumed by subscribers to the relevant channels—a sign of actual demand rather than manipulation or preference falsification—or encountered via links from external sites. It’s easy to see why we might prefer if this were not the case: algorithmic radicalization is presumably a simpler problem to solve than the fact that there are people who deliberately seek out vile content. “These are the three stories—echo chambers, foreign influence campaigns, and radicalizing recommendation algorithms—but, when you look at the literature, they’ve all been overstated.” He thought that these findings were crucial for us to assimilate, if only to help us understand that our problems may lie beyond technocratic tinkering. He explained, “Part of my interest in getting this research out there is to demonstrate that everybody is waiting for an Elon Musk to ride in and save us with an algorithm”—or, presumably, the reverse—“and it’s just not going to happen.”

When I spoke with Nyhan, he told me much the same thing: “The most credible research is way out of line with the takes.” He noted, of extremist content and misinformation, that reliable research that “measures exposure to these things finds that the people consuming this content are small minorities who have extreme views already.” The problem with the bulk of the earlier research, Nyhan told me, is that it’s almost all correlational. “Many of these studies will find polarization on social media,” he said. “But that might just be the society we live in reflected on social media!” He hastened to add, “Not that this is untroubling, and none of this is to let these companies, which are exercising a lot of power with very little scrutiny, off the hook. But a lot of the criticisms of them are very poorly founded. . . . The expansion of Internet access coincides with fifteen other trends over time, and separating them is very difficult. The lack of good data is a huge problem insofar as it lets people project their own fears into this area.” He told me, “It’s hard to weigh in on the side of ‘We don’t know, the evidence is weak,’ because those points are always going to be drowned out in our discourse. But these arguments are systematically underprovided in the public domain.”

In his Atlantic article, Haidt leans on a working paper by two social scientists, Philipp Lorenz-Spreen and Lisa Oswald, who took on a comprehensive meta-analysis of about five hundred papers and concluded that “the large majority of reported associations between digital media use and trust appear to be detrimental for democracy.” Haidt writes, “The literature is complex—some studies show benefits, particularly in less developed democracies—but the review found that, on balance, social media amplifies political polarization; foments populism, especially right-wing populism; and is associated with the spread of misinformation.” Nyhan was less convinced that the meta-analysis supported such categorical verdicts, especially once you bracketed the kinds of correlational findings that might simply mirror social and political dynamics. He told me, “If you look at their summary of studies that allow for causal inferences—it’s very mixed.”

As for the studies Nyhan considered most methodologically sound, he pointed to a 2020 article called “The Welfare Effects of Social Media,” by Hunt Allcott, Luca Braghieri, Sarah Eichmeyer, and Matthew Gentzkow. For four weeks prior to the 2018 midterm elections, the authors randomly divided a group of volunteers into two cohorts—one that continued to use Facebook as usual, and another that was paid to deactivate their accounts for that period. They found that deactivation “(i) reduced online activity, while increasing offline activities such as watching TV alone and socializing with family and friends; (ii) reduced both factual news knowledge and political polarization; (iii) increased subjective well-being; and (iv) caused a large persistent reduction in post-experiment Facebook use.” But Gentzkow reminded me that his conclusions, including that Facebook may slightly increase polarization, had to be heavily qualified: “From other kinds of evidence, I think there’s reason to think social media is not the main driver of increasing polarization over the long haul in the United States.”

In the book “ Why We’re Polarized ,” for example, Ezra Klein invokes the work of such scholars as Lilliana Mason to argue that the roots of polarization might be found in, among other factors, the political realignment and nationalization that began in the sixties, and were then sacralized, on the right, by the rise of talk radio and cable news. These dynamics have served to flatten our political identities, weakening our ability or inclination to find compromise. Insofar as some forms of social media encourage the hardening of connections between our identities and a narrow set of opinions, we might increasingly self-select into mutually incomprehensible and hostile groups; Haidt plausibly suggests that these processes are accelerated by the coalescence of social-media tribes around figures of fearful online charisma. “Social media might be more of an amplifier of other things going on rather than a major driver independently,” Gentzkow argued. “I think it takes some gymnastics to tell a story where it’s all primarily driven by social media, especially when you’re looking at different countries, and across different groups.”

Another study, led by Nejla Asimovic and Joshua Tucker, replicated Gentzkow’s approach in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and they found almost precisely the opposite results: the people who stayed on Facebook were, by the end of the study, more positively disposed to their historic out-groups. The authors’ interpretation was that ethnic groups have so little contact in Bosnia that, for some people, social media is essentially the only place where they can form positive images of one another. “To have a replication and have the signs flip like that, it’s pretty stunning,” Bail told me. “It’s a different conversation in every part of the world.”

Nyhan argued that, at least in wealthy Western countries, we might be too heavily discounting the degree to which platforms have responded to criticism: “Everyone is still operating under the view that algorithms simply maximize engagement in a short-term way” with minimal attention to potential externalities. “That might’ve been true when Zuckerberg had seven people working for him, but there are a lot of considerations that go into these rankings now.” He added, “There’s some evidence that, with reverse-chronological feeds”—streams of unwashed content, which some critics argue are less manipulative than algorithmic curation—“people get exposed to more low-quality content, so it’s another case where a very simple notion of ‘algorithms are bad’ doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. It doesn’t mean they’re good, it’s just that we don’t know.”

Bail told me that, over all, he was less confident than Haidt that the available evidence lines up clearly against the platforms. “Maybe there’s a slight majority of studies that say that social media is a net negative, at least in the West, and maybe it’s doing some good in the rest of the world.” But, he noted, “Jon will say that science has this expectation of rigor that can’t keep up with the need in the real world—that even if we don’t have the definitive study that creates the historical counterfactual that Facebook is largely responsible for polarization in the U.S., there’s still a lot pointing in that direction, and I think that’s a fair point.” He paused. “It can’t all be randomized control trials.”

Haidt comes across in conversation as searching and sincere, and, during our exchange, he paused several times to suggest that I include a quote from John Stuart Mill on the importance of good-faith debate to moral progress. In that spirit, I asked him what he thought of the argument, elaborated by some of Haidt’s critics, that the problems he described are fundamentally political, social, and economic, and that to blame social media is to search for lost keys under the streetlamp, where the light is better. He agreed that this was the steelman opponent: there were predecessors for cancel culture in de Tocqueville, and anxiety about new media that went back to the time of the printing press. “This is a perfectly reasonable hypothesis, and it’s absolutely up to the prosecution—people like me—to argue that, no, this time it’s different. But it’s a civil case! The evidential standard is not ‘beyond a reasonable doubt,’ as in a criminal case. It’s just a preponderance of the evidence.”

The way scholars weigh the testimony is subject to their disciplinary orientations. Economists and political scientists tend to believe that you can’t even begin to talk about causal dynamics without a randomized controlled trial, whereas sociologists and psychologists are more comfortable drawing inferences on a correlational basis. Haidt believes that conditions are too dire to take the hardheaded, no-reasonable-doubt view. “The preponderance of the evidence is what we use in public health. If there’s an epidemic—when COVID started, suppose all the scientists had said, ‘No, we gotta be so certain before you do anything’? We have to think about what’s actually happening, what’s likeliest to pay off.” He continued, “We have the largest epidemic ever of teen mental health, and there is no other explanation,” he said. “It is a raging public-health epidemic, and the kids themselves say Instagram did it, and we have some evidence, so is it appropriate to say, ‘Nah, you haven’t proven it’?”

This was his attitude across the board. He argued that social media seemed to aggrandize inflammatory posts and to be correlated with a rise in violence; even if only small groups were exposed to fake news, such beliefs might still proliferate in ways that were hard to measure. “In the post-Babel era, what matters is not the average but the dynamics, the contagion, the exponential amplification,” he said. “Small things can grow very quickly, so arguments that Russian disinformation didn’t matter are like COVID arguments that people coming in from China didn’t have contact with a lot of people.” Given the transformative effects of social media, Haidt insisted, it was important to act now, even in the absence of dispositive evidence. “Academic debates play out over decades and are often never resolved, whereas the social-media environment changes year by year,” he said. “We don’t have the luxury of waiting around five or ten years for literature reviews.”

Haidt could be accused of question-begging—of assuming the existence of a crisis that the research might or might not ultimately underwrite. Still, the gap between the two sides in this case might not be quite as wide as Haidt thinks. Skeptics of his strongest claims are not saying that there’s no there there. Just because the average YouTube user is unlikely to be led to Stormfront videos, Nyhan told me, doesn’t mean we shouldn’t worry that some people are watching Stormfront videos; just because echo chambers and foreign misinformation seem to have had effects only at the margins, Gentzkow said, doesn’t mean they’re entirely irrelevant. “There are many questions here where the thing we as researchers are interested in is how social media affects the average person,” Gentzkow told me. “There’s a different set of questions where all you need is a small number of people to change—questions about ethnic violence in Bangladesh or Sri Lanka, people on YouTube mobilized to do mass shootings. Much of the evidence broadly makes me skeptical that the average effects are as big as the public discussion thinks they are, but I also think there are cases where a small number of people with very extreme views are able to find each other and connect and act.” He added, “That’s where many of the things I’d be most concerned about lie.”

The same might be said about any phenomenon where the base rate is very low but the stakes are very high, such as teen suicide. “It’s another case where those rare edge cases in terms of total social harm may be enormous. You don’t need many teen-age kids to decide to kill themselves or have serious mental-health outcomes in order for the social harm to be really big.” He added, “Almost none of this work is able to get at those edge-case effects, and we have to be careful that if we do establish that the average effect of something is zero, or small, that it doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be worried about it—because we might be missing those extremes.” Jaime Settle, a scholar of political behavior at the College of William & Mary and the author of the book “ Frenemies: How Social Media Polarizes America ,” noted that Haidt is “farther along the spectrum of what most academics who study this stuff are going to say we have strong evidence for.” But she understood his impulse: “We do have serious problems, and I’m glad Jon wrote the piece, and down the road I wouldn’t be surprised if we got a fuller handle on the role of social media in all of this—there are definitely ways in which social media has changed our politics for the worse.”

It’s tempting to sidestep the question of diagnosis entirely, and to evaluate Haidt’s essay not on the basis of predictive accuracy—whether social media will lead to the destruction of American democracy—but as a set of proposals for what we might do better. If he is wrong, how much damage are his prescriptions likely to do? Haidt, to his great credit, does not indulge in any wishful thinking, and if his diagnosis is largely technological his prescriptions are sociopolitical. Two of his three major suggestions seem useful and have nothing to do with social media: he thinks that we should end closed primaries and that children should be given wide latitude for unsupervised play. His recommendations for social-media reform are, for the most part, uncontroversial: he believes that preteens shouldn’t be on Instagram and that platforms should share their data with outside researchers—proposals that are both likely to be beneficial and not very costly.

It remains possible, however, that the true costs of social-media anxieties are harder to tabulate. Gentzkow told me that, for the period between 2016 and 2020, the direct effects of misinformation were difficult to discern. “But it might have had a much larger effect because we got so worried about it—a broader impact on trust,” he said. “Even if not that many people were exposed, the narrative that the world is full of fake news, and you can’t trust anything, and other people are being misled about it—well, that might have had a bigger impact than the content itself.” Nyhan had a similar reaction. “There are genuine questions that are really important, but there’s a kind of opportunity cost that is missed here. There’s so much focus on sweeping claims that aren’t actionable, or unfounded claims we can contradict with data, that are crowding out the harms we can demonstrate, and the things we can test, that could make social media better.” He added, “We’re years into this, and we’re still having an uninformed conversation about social media. It’s totally wild.”

New Yorker Favorites

An Oscar-winning filmmaker takes on the Church of Scientology .

Wendy Wasserstein on the baby who arrived too soon .

The young stowaways thrown overboard at sea .

As he rose in politics, Robert Moses discovered that decisions about New York City’s future would not be based on democracy .

The Muslim tamale king of the Old West .

Fiction by Jamaica Kincaid: “ Girl .”

Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .

PSYCH 424 blog

Anonymity and social media.

Even though the advances of technology and social have enabled people to connect and communicate more easily, it has negative effects, such as using anonymity online to hurt and bully people. News everywhere are shown often of young people committing suicide because they were bullied online. Cyber bullying could involve sending harmful messages online, harassment, threats, and humiliation involving the use of social media. It makes you think, why do people feel more prone to hurt others when they are hiding behind anonymity? And, what is it about anonymity online that changes a person’s identity or personality and makes them want to bully people on the web?

A study conducted in Taiwan with high school students as participants tried to evaluate the use of an anonymous presence online and its association with cyber bullying behavior. The results determined that the use of a high level of anonymity and reduced social cue lead to create higher degrees of cyber bullying behavior (Wu & Lien, 2013). There exists a perception of anonymity that comes with lowered feelings of accountability that could result in reduced public self-awareness. If someone is bullying another person online, and the victim does not know who the bully is, then the bully might increase the abuse since he or she will feel like there is no way they could be traced or could be held accountable for their actions.

You see evidence of these types of behaviors in all social media. If you go to youtube and look at the comment section, you will encounter people offending other people by insulting them simply because they do not agree with their opinions. On twitter, you will encounter the same situation; tweets are sent to other people with threats. In a way, social media enables people to take on different identities, or helps them create a new one. Manago, Graham, Greenfield, and Salimkhan suggest that the flexibility of communication capacities frees individuals from existing at the effect of an externally created media environment, and that identity becomes socially constructed in environments such as a chat room (2008). A young boy who decides to participate in a chat room about video games could see the different interactions of his peers. These interactions could include some users calling other user names, or bullying, and this young boy might determine that these people do not face any consequences for their actions; therefore he might want to decide to take on the same type of personality or identity online, and he could start cyber bullying his peers.

Intervention for these types of behaviors can start at home. Parents could monitor the websites their children visit and see how they are behaving online. If they do see that there is a behavior that should be stopped, then they can talk to their children about the negative effects these actions might cause on other people. At schools, principals, teachers and other staff members could give seminars to the students and to staff that show the effects of cyber bullying, and together they could create protocols for reporting cyber bullying and how they could intervene to prevent or stop these behaviors.

References:

Manago, Graham, Greenfield, & Salimkhan (2008) Self-presentationand gender on MySpace. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology . 29(6)

Wu, W. P., & Lien, C. C. (2013). Cyberbullying: An empirical analysis of factors related to anonymity and reduced social cue. Applied Mechanics and Materials, 311 , 533.

This entry was posted on Monday, October 26th, 2015 at 1:36 am and is filed under Uncategorized . You can follow any comments to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a comment , or trackback from your own site.

I can really relate to this post because I was a victim of cyber-bullying in middle and high school. There was a hate group made on Facebook by a boy I thought was my friend. I have also seen cyber-bullying on twitter and comment sections, people use such vulgar language and insulting words because they can get away with it without anyone finding out who they are. Because my parents did monitor my internet activity, they were able to help and stop the Facebook page from getting any bigger and helped me get through tough times when I was feeling upset about it. Had they not monitored my activity they could have never helped me through that rough time because I hadn’t wanted to tell them about it. I think the opposite could also help, with the growing abilities of parental controls.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Recent Posts

- Seinfeld’s Final Social Statement: The Cost of Inaction

- The psychological power of digital books in education

- Understanding Masculinity, Suicide, Prejudice, and Discrimination

- NGO of My Climate: Empowering Environmental Protection Through Innovative Carbon Offset Solutions

- Talk about Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT)

Recent Comments

- ama7669 on Does the justice system skew the reliability of eyewitness testimony?

- ama7669 on Escape Rooms need team cohesion for success!

- ama7669 on Lesson 6 Blog

- ama7669 on The Hopelessness Theory, Biomedical Model, and Depression from Diagnosis of a Chronic Illness

- tvz5192 on Embracing Diversity in a World of Uncertainty

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- February 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- February 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- February 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- February 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- February 2019

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- February 2018

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- February 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- February 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- February 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- create an entry

- Uncategorized

- Entries feed

- Comments feed

- WordPress.org

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Anonymity in social networks: The case of anonymous social media

2019, International Journal of Electronic Governance

Related Papers

Aaron Beach

Proceedings of second ACM …

Silvia Llorente

The number of users of social networks (SN) has increased dramatically during the last years. In turn, the number of applications offered by SNs, as well as their usage by SN users, has also increased significantly. These applications are developed by third parties and access users’ data to operate. This fact poses serious privacy risks, since SNs do not provide mechanisms to specify users’ privacy preferences for the usage done by third party applications over their personal data. This paper proposes a solution based on the usage of access control languages to keep track of the usage done by SN applications of users’ personal data.

16th International Conference on Advanced Communication Technology

Hoang Tung Phong

Rath Kanha Sar

Austin Beach

Alessio Merlo

Mobile applications (hereafter, apps) collect a plethora of information regarding the user behavior and his device through third-party analytics libraries. However, the collection and usage of such data raised several privacy concerns, mainly because the end-user i.e., the actual owner of the data is out of the loop in this collection process. Also, the existing privacy-enhanced solutions that emerged in the last years follow an ”all or nothing” approach, leaving the user the sole option to accept or completely deny the access to privacy-related data. This work has the two-fold objective of assessing the privacy implications on the usage of analytics libraries in mobile apps and proposing a data anonymization methodology that enables a trade-off between the utility and privacy of the collected data and gives the user complete control over the sharing process. To achieve that, we present an empirical privacy assessment on the analytics libraries contained in the 4500 most-used Androi...

Handbook of Computer Networks and Cyber Security

Rachna Jain

Cyber Deception

Fabio De Gaspari

In the wake of surveillance scandals in recent years, as well of the continuous deployment of more sophisticated censorship mechanisms, concerns over anonymity and privacy on the Internet are ever growing. In the last decades, researchers have designed and proposed several algorithms and solutions that allow interested parties to maintain anonymity online, even against powerful opponents. In this chapter, we present a survey of the classical anonymity schemes that proved to be most successful, describing how they work and their main shortcomings. Finally, we discuss new directions in Anonymous Communication Networks (ACN) taking advantage of today’s services, like On-Line Social Networks (OSN). OSN offer a vast pool of participants, allowing to effectively disguise traffic in the high volume of daily communications, thus offering high levels of anonymity and good resistance to analysis techniques.

Proceedings of the first workshop on …

Saikat Guha

Privacy and Identity …

Bibi van den Berg

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

researchgate.net

Sebastian Banescu

Daniele Midi

2010 8th IEEE International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Communications Workshops (PERCOM Workshops)

Dr. Didier Samfat

Brazilian Journal of Information Science: research trends

Ricardo Santana

Firuze Nur Atmaca

… of the Seventh Symposium on Usable …

Airi Lampinen

Tyrone Grandison

Seda Gurses

Lecture Notes in Computer Science

Jose daniel nuñez hurtado

Sanaz Kavianpour

2008 Web 2.0 Security and Privacy (W2SP'08)

David Evans

Shankar Badavath

ravi shanker

Internet Policy Review

Claudine Tinsman

Computer Science Department Faculty Publication Series

Michael P Hay

B. Tech (CSE) Seminar Report, Semester VI, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, NIST, Odisha, India.

International Journal of Experimental Research and Review

'International Journal of Experimental Research and Review ISSN 2455-4855 (Online)

Proceedings on Privacy Enhancing Technologies

Chad Spensky

Proceedings of the Eleventh Workshop on Mobile Computing Systems & Applications - HotMobile '10

Krishna Puttaswamy

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Articles on Online anonymity

Displaying 1 - 20 of 25 articles.

Sendit, Yolo, NGL: anonymous social apps are taking over once more, but they aren’t without risks

Alexia Maddox , RMIT University

Ending online anonymity won’t make social media less toxic

Shireen Morris , Macquarie University

Online abuse: banning anonymous social media accounts is not the answer

Harry T Dyer , University of East Anglia

Don’t be phish food! Tips to avoid sharing your personal information online

Nik Thompson , Curtin University

Lifelong anonymity orders: do they still work in the social media age?

Faith Gordon , Monash University and Julie Doughty , Cardiff University

Anonymous apps risk fuelling cyberbullying but they also fill a vital role

Killian O'Leary , Lancaster University and Stephen Murphy , University of Essex

Illuminating the ‘dark web’

Robert W. Gehl , University of Utah

By concealing identities, cryptocurrencies fuel cybercrime

Ari Juels , Cornell University ; Iddo Bentov , Cornell University , and Ittay Eyal , Cornell University

CNN-Reddit saga exposes tension between the internet, anonymity and power

Bree McEwan , DePaul University

Bitcoin’s central appeal could also be its biggest weakness

Corina Sas , Lancaster University

Tor upgrades to make anonymous publishing safer

Philipp Winter , Princeton University

Far beyond crime-ridden depravity, darknets are key strongholds of freedom of expression online

Roderick S. Graham , Old Dominion University and Brian Pitman , Old Dominion University

How news sites’ online comments helped build our hateful electorate

Marie K. Shanahan , University of Connecticut

Could encryption ‘backdoors’ safeguard privacy and fight terror online?

Keith Martin , Royal Holloway University of London

Vuvuzela, a next-generation anonymity tool that protects users by adding NOISE

Martin Berger , University of Sussex

The fall of Silk Road isn’t the end for anonymous marketplaces, Tor or bitcoin

Matthew Shillito , University of Liverpool

Tor: the last bastion of online anonymity, but is it still secure after Silk Road?

Steven J. Murdoch , UCL

‘Haters gonna hate’ is no consolation for online moderators

Jennifer Beckett , The University of Melbourne