- Skip to header navigation

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- Member login

International Federation of Social Workers

Global Online conference

Global Social Work Statement of Ethical Principles

July 2, 2018

Global Social Work Statement of Ethical Principles:

This Statement of Ethical Principles (hereafter referred to as the Statement) serves as an overarching framework for social workers to work towards the highest possible standards of professional integrity.

Implicit in our acceptance of this Statement as social work practitioners, educators, students, and researchers is our commitment to uphold the core values and principles of the social work profession as set out in this Statement.

An array of values and ethical principles inform us as social workers; this reality was recognized in 2014 by the International Federation of Social Workers and The International Association of Schools of Social Work in the global definition of social work, which is layered and encourages regional and national amplifications.

All IFSW policies including the definition of social work stem from these ethical principles.

Social work is a practice-based profession and an academic discipline that facilitates social change and development, social cohesion, and the empowerment and liberation of people. Principles of social justice, human rights, collective responsibility and respect for diversities are central to social work. Underpinned by theories of social work, social sciences, humanities and indigenous knowledge, social work engages people and structures to address life challenges and enhance wellbeing . http://ifsw.org/get-involved/global-definition-of-social-work/

Principles:

- Recognition of the Inherent Dignity of Humanity

Social workers recognize and respect the inherent dignity and worth of all human beings in attitude, word, and deed. We respect all persons, but we challenge beliefs and actions of those persons who devalue or stigmatize themselves or other persons.

- Promoting Human Rights

Social workers embrace and promote the fundamental and inalienable rights of all human beings. Social work is based on respect for the inherent worth, dignity of all people and the individual and social /civil rights that follow from this. Social workers often work with people to find an appropriate balance between competing human rights.

- Promoting Social Justice

Social workers have a responsibility to engage people in achieving social justice, in relation to society generally, and in relation to the people with whom they work. This means:

3.1 Challenging Discrimination and Institutional Oppression

Social workers promote social justice in relation to society generally and to the people with whom they work.

Social workers challenge discrimination, which includes but is not limited to age, capacity, civil status, class, culture, ethnicity, gender, gender identity, language, nationality (or lack thereof), opinions, other physical characteristics, physical or mental abilities, political beliefs, poverty, race, relationship status, religion, sex, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, spiritual beliefs, or family structure.

3.2 Respect for Diversity

Social workers work toward strengthening inclusive communities that respect the ethnic and cultural diversity of societies, taking account of individual, family, group, and community differences.

3.3 Access to Equitable Resources

Social workers advocate and work toward access and the equitable distribution of resources and wealth.

3.4 Challenging Unjust Policies and Practices

Social workers work to bring to the attention of their employers, policymakers, politicians, and the public situations in which policies and resources are inadequate or in which policies and practices are oppressive, unfair, or harmful. In doing so, social workers must not be penalized.

Social workers must be aware of situations that might threaten their own safety and security, and they must make judicious choices in such circumstances. Social workers are not compelled to act when it would put themselves at risk.

3.5 Building Solidarity

Social workers actively work in communities and with their colleagues, within and outside of the profession, to build networks of solidarity to work toward transformational change and inclusive and responsible societies.

- Promoting the Right to Self-Determination

Social workers respect and promote people’s rights to make their own choices and decisions, provided this does not threaten the rights and legitimate interests of others.

- Promoting the Right to Participation

Social workers work toward building the self-esteem and capabilities of people, promoting their full involvement and participation in all aspects of decisions and actions that affect their lives.

- Respect for Confidentiality and Privacy

6.1 Social workers respect and work in accordance with people’s rights to confidentiality and privacy unless there is risk of harm to the self or to others or other statutory restrictions.

6.2 Social workers inform the people with whom they engage about such limits to confidentiality and privacy.

- Treating People as Whole Persons

Social workers recognize the biological, psychological, social, and spiritual dimensions of people’s lives and understand and treat all people as whole persons. Such recognition is used to formulate holistic assessments and interventions with the full participation of people, organizations, and communities with whom social workers engage.

- Ethical Use of Technology and Social Media

8.1 The ethical principles in this Statement apply to all contexts of social work practice, education, and research, whether it involves direct face-to-face contact or through use of digital technology and social media.

8.2 Social workers must recognize that the use of digital technology and social media may pose threats to the practice of many ethical standards including but not limited to privacy and confidentiality, conflicts of interest, competence, and documentation and must obtain the necessary knowledge and skills to guard against unethical practice when using technology.

- Professional Integrity

9.1 It is the responsibility of national associations and organizations to develop and regularly update their own codes of ethics or ethical guidelines, to be consistent with this Statement, considering local situations. It is also the responsibility of national organizations to inform social workers and schools of social work about this Statement of Ethical Principles and their own ethical guidelines. Social workers should act in accordance with the current ethical code or guidelines in their country.

9.2 Social workers must hold the required qualifications and develop and maintain the required skills and competencies to do their job.

9.3 Social workers support peace and nonviolence. Social workers may work alongside military personnel for humanitarian purposes and work toward peacebuilding and reconstruction. Social workers operating within a military or peacekeeping context must always support the dignity and agency of people as their primary focus. Social workers must not allow their knowledge and skills to be used for inhumane purposes, such as torture, military surveillance, terrorism, or conversion therapy, and they should not use weapons in their professional or personal capacities against people.

9.4 Social workers must act with integrity. This includes not abusing their positions of power and relationships of trust with people that they engage with; they recognize the boundaries between personal and professional life and do not abuse their positions for personal material benefit or gain.

9.5 Social workers recognize that the giving and receiving of small gifts is a part of the social work and cultural experience in some cultures and countries. In such situations, this should be referenced in the country’s code of ethics.

9.6 Social workers have a duty to take the necessary steps to care for themselves professionally and personally in the workplace, in their private lives and in society.

9.7 Social workers acknowledge that they are accountable for their actions to the people they work with; their colleagues; their employers; their professional associations; and local, national, and international laws and conventions and that these accountabilities may conflict, which must be negotiated to minimize harm to all persons. Decisions should always be informed by empirical evidence; practice wisdom; and ethical, legal, and cultural considerations. Social workers must be prepared to be transparent about the reasons for their decisions.

9.8 Social workers and their employing bodies work to create conditions in their workplace environments and in their countries, where the principles of this Statement and those of their own national codes are discussed, evaluated, and upheld. Social workers and their employing bodies foster and engage in debate to facilitate ethically informed decisions.

Spanish translation – Traducción Español

Chinese Translation 全球社會工作倫理原則聲明 (繁體字譯本)

The Global Statement of Ethical Principles was approved at the General Meetings of the International Federation of Social Workers and the General Assembly of the International Association of Schools of Social Work (IASSW) in Dublin, Ireland, in July 2018. IASSW additionally endorsed a longer version: Global-Social-Work-Statement-of-Ethical-Principles-IASSW-27-April-2018-1

National Code of Ethics

National Codes of Ethics of Social Work adopted by IFSW Member organisations. The Codes of Ethics are in the national languages of the different countries. More national codes of ethics will soon be added to the ones below:

- Canada | Guidelines for ethical practice

- Finland (Englis)

- Finland (Finish)

- Puerto Rico English | Spanish

- South Korea English | Korean

- Sweden English | Swedish

- Switzerland English | German | French | Italian

- Turkey English | Turkish

- United Kingdom

- Login / Account

- Documentation

- Online Participation

- Constitution/ Governance

- Secretariat

- Our members

- General Meetings

- Executive Meetings

- Meeting papers 2018

- Global Definition of Social Work

- Meet Social Workers from around the world

- Frequently Asked Questions

- IFSW Africa

- IFSW Asia and Pacific

- IFSW Europe

- IFSW Latin America and Caribbean

- IFSW North America

- Education Commission

- Ethics Commission

- Indigenous Commission

- United Nations Commission

- Information Hub

- Upcoming Events

- Keynote Speakers

- Global Agenda

- Archive: European DM 2021

- The Global Agenda

- World Social Work Day

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

The Handbook of Social Research Ethics

- Donna M. Mertens - Gallaudet University, USA

- Pauline E. Ginsberg - Utica College, USA

- Description

The Handbook of Social Research Ethics is the first comprehensive volume of its kind to offer a deeper understanding of the history, theory, philosophy, and implementation of applied social research ethics. Editors Donna M. Mertens and Pauline Ginsberg bring together eminent, international scholars across the social and behavioral sciences and education to address the ethical issues that arise in the theory and practice of research within the technologically advancing and culturally complex world in which we live. In addition, this volume examines the ethical dilemmas that arise in the relationship between research practice and social justice issues. Key Features

- Situates the ethical concerns in the practice of social science research in historical and epistemological contexts

- Explores the philosophical roots of ethics from the perspectives of Kant, J.S. Mill, Hegel, and others

- Provides an overview and comparison of ethical regulations across disciplines, governments, and additional contexts such as IRBs, program evaluation, and more

- Examines specific ethical issues that arise in traditional methods and methodologies

- Addresses ethical concerns within a variety of diverse, cultural contexts

Intended Audience

| ISBN: 9781412949187 | Hardcover | Suggested Retail Price: $195.00 | Bookstore Price: $156.00 |

| ISBN: 9781483343464 | Electronic Version | Suggested Retail Price: $156.00 | Bookstore Price: $124.80 |

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

- Historically and epistemologically situates ethical concerns in the practice of social science research;

- Contextualizes philosophical roots of ethics from the perspectives of Kant, J.S. Mill, Hegel, and others;

- Provides an overview and comparison of ethical regulations across disciplines, governments, and additional contexts such as IRBs, program evaluation, and more;

- Examines specific ethical issues that arise in traditional methods and methodologies (e.g., experimental design, lab research, archival and secondary data retrieval and analysis);

- Addresses ethical concerns within a variety of diverse, cultural contexts such as race, ethnicity, age, class, religion, gender, and disability.

Select a Purchasing Option

This title is also available on SAGE Research Methods , the ultimate digital methods library. If your library doesn’t have access, ask your librarian to start a trial .

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

The status of research ethics in social work

Affiliation.

- 1 a College of Social Work , Florida State University , Tallahassee , USA.

- PMID: 29843568

- DOI: 10.1080/23761407.2018.1478756

Research ethics provide important and necessary standards related to the conduct and dissemination of research. To better understand the current state of research ethics discourse in social work, a systematic literature search was undertaken and numbers of publications per year were compared between STEM, social science, and social work disciplines. While many professions have embraced the need for discipline-specific research ethics subfield development, social work has remained absent. Low publication numbers, compared to other disciplines, were noted for the years (2006-2016) included in the study. Social work published 16 (1%) of the 1409 articles included in the study, contributing 3 (>1%) for each of the disciplines highest producing years (2011 and 2013). Comparatively, psychology produced 75 (5%) articles, psychiatry produced 64 (5%) articles, and nursing added 50 (4%) articles. The STEM disciplines contributed 956 (68%) articles between 2006 and 2016, while social science produced 453 (32%) articles. Examination of the results is provided in an extended discussion of several misconceptions about research ethics that may be found in the social work profession. Implications and future directions are provided, focusing on the need for increased engagement, education, research, and support for a new subfield of social work research ethics.

Keywords: Research ethics; responsible conduct of research; social work ethics; social work research.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Bibliometrics and social work: a two-edged sword can still be a blunt instrument. Ligon J, Thyer BA. Ligon J, et al. Soc Work Health Care. 2005;41(3-4):123-8. doi: 10.1300/J010v41n03_08. Soc Work Health Care. 2005. PMID: 16236644

- The paradox of faculty publications in professional journals. Green RG. Green RG. Soc Work Health Care. 2005;41(3-4):103-8. doi: 10.1300/J010v41n03_05. Soc Work Health Care. 2005. PMID: 16236641

- Authorship and publication practices in the social sciences: historical reflections on current practices. Bebeau MJ, Monson V. Bebeau MJ, et al. Sci Eng Ethics. 2011 Jun;17(2):365-88. doi: 10.1007/s11948-011-9280-4. Epub 2011 Jun 7. Sci Eng Ethics. 2011. PMID: 21647594 Review.

- Shallow science or meta-cognitive insights: a few thoughts on reflection via bibliometrics. Holden G, Rosenberg G, Barker K. Holden G, et al. Soc Work Health Care. 2005;41(3-4):129-48. doi: 10.1300/J010v41n03_09. Soc Work Health Care. 2005. PMID: 16236645 Review.

- Ethics approval, guarantees of quality and the meddlesome editor. Long T, Fallon D. Long T, et al. J Clin Nurs. 2007 Aug;16(8):1398-404. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01918.x. J Clin Nurs. 2007. PMID: 17655528 Review.

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Other literature sources.

- scite Smart Citations

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter Three: Ethics in social work research

Would it surprise you learn that scientists who conduct research may withhold effective treatments from individuals with diseases? Perhaps it wouldn’t surprise you, since you may have heard of the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment, in which treatments for syphilis were knowingly withheld from African-American participants for decades. Would it surprise you to learn that the practice of withholding treatment continues today? Multiple studies in the developing world continue to use placebo control groups in testing for cancer screenings, cancer treatments, and HIV treatments (Joffe & Miller, 2014). [1] What standards would you use to judge withholding treatment as ethical or unethical? Most importantly, how can you make sure that your study respects the human rights of your participants?

Chapter Outline

- 3.1 Research on humans

- 3.2 Specific ethical issues to consider

- 3.3 Ethics at micro, meso, and macro levels

- 3.4 The practice of science versus the uses of science

Content Advisory

This chapter discusses or mentions the following topics: unethical research that has occurred in the past against marginalized groups in America and during the Holocaust.

- Joffe, S., & Miller, F. G. (2014). Ethics of cancer clinical trials in low-resource settings. Journal of Clinical Oncology , 32 (28), 3192-3196. ↵

Foundations of Social Work Research Copyright © 2020 by Rebecca L. Mauldin is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Module 1 Chapter 3: Ethical Conduct of Research

The NASW professional code of ethics has quite a lot to say about ensuring that research be conducted in an ethical manner, so here we revisit the code of ethics to review these research-specific standards. We begin with an overview of historical events that bring us to where we are today in the research ethics arena. This content is covered in greater depth and detail in your CITI (Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative) program training modules. Then, we return to the section of NASW’s (2017) Code of Ethics that we initially visited in Chapter 1.

In reading this chapter, you will learn:

- Key facts about research ethics;

- Statements from the NASW Code of Ethics specific to the ethical conduct of research

History and Research Ethics

Following the conclusion of World War II and subsequent “Doctors’ Trial” portion of the Nuremberg Trials, the 10-point Nuremberg Code was developed as a response to numerous examples of unethical, inhumane “medical” experiments conducted in concentration camps. The Nuremberg Code was relatively ignored for many years, at least in the United States. Subsequently, a number of grievously unethical experiments were conducted on prisoners, institutionalized patients, and children—disproportionately on poor and racial minority populations—including exposure to toxins, diseases, radiation, or torture. The Tuskegee syphilis experiment represents a critical turning point in the nation’s tolerance of unethical human research. In 1932, the U.S. Public Health Service partnered with the Tuskegee Institute to study the natural course of syphilis among 399 black men. Over 40 years, the men believed they were being treated for syphilis, but were in fact receiving no treatment for the disease, even when penicillin proved to be an effective form of treatment by 1947. Beginning in 1968, concerns were being raised and condemning news reports were widely circulated in 1972, leading to the study being ended. By 1974, the Tuskegee Health Benefit Program was established by the U.S. government to ensure health and burial benefits to the study’s remaining survivors, wives, widows, and children.

In response to concerns about unethical research practices, a national group was formed (in 1974, the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research), and created what is now known as The Belmont Report (1979). The Belmont Report, in turn, influenced development of federal policy (1981, revised 2009) concerning protections for human research subjects—the Common Rule. The Belmont Report presented a summary of ethical guidelines for engaging in research that involves human subjects. The guidelines are based on three core principles:

- Respect for persons. This principle is founded on a conviction that “individuals should be treated as autonomous agents” (Belmont Report, 1979, p. 4). The report explains this autonomy in terms of respecting a person’s right to making considered, informed choices, and places a responsibility on researchers to ensure that a person has all of the information necessary for self-determined choices and is free from constraints on making self-determined choices. The discussion also addresses situations where a person might not be capable of self-determination and what protections might be necessary in these instances.

- Beneficence. This principle is about an obligation for protecting participants from harm and “making efforts to secure their well-being” (Belmont Report, 1979, p. 5). This translates into ensuring that benefits to participants are maximized and possible harms or risks are minimized.

- Justice. This principle is about fairness. Justice in this context is about ensuring a fair and just distribution of both the potential burdens and the potential benefits of participating in research. “Another way of conceiving the principle of justice is that equals ought to be treated equally” (Belmont report, 1979, p. 5).

These three core principles are closely aligned with the core values of our social work profession. Our code of ethics is based on principles that include respect for the dignity and worth of the individual, which includes fostering client self-determination, as well as practicing with integrity.

The Belmont Report (1979) also contains language about distinguishing between research and professional practice. The report defines practice in this way:

“…interventions that are designed solely to enhance the well-being of an individual patient or client and that have a reasonable expectation of success” (p. 3).

Research is defined in the Belmont Report as:

“…an activity designed to test an hypothesis, permit conclusions to be drawn, and thereby to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge” (p. 3).

These two types of professional activity are clearly contrasted—their goals are markedly different. Practice goals relate to benefits for the individuals being served; research goals are served by the individuals who participate.

Take a moment to complete the following activity.

Revisiting the NASW Code of Ethics

We previously examined what the NASW Code of Ethics had to say about the role of research and evidence in professional practice and the role of social work professionals in engaging with research and evidence. At this point, we turn again to the Code of Ethics to see what is specified in terms of the ethical conduct of research. These details are in addition to what was discussed earlier about research integrity.

Standard 5.02: Evaluation and Research continued . Let’s pick up where we left off in reviewing the NASW Code of Ethics content related to engaging in evaluation and research as a social work professional. The Code of Ethics (p. 27-28) replicates many elements found in the current federal policy concerning the protection of human subjects in research and in the 1996 Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). The Code of Ethics states that:

- (d) Social workers engaged in evaluation or research should carefully consider possible consequences and should follow guidelines developed for the protection of evaluation and research participants. Appropriate institutional review boards should be consulted

- (e) Social workers engaged in evaluation or research should obtain voluntary and written informed consent from participants, when appropriate, without any implied or actual deprivation or penalty for refusal to participate; without undue inducement to participate; and with due regard for participants’ well-being, privacy, and dignity. Informed consent should include information about the nature, extent, and duration of the participation requested and disclosure of the risks and benefits of participation in the research.

- (f) When using electronic technology to facilitate evaluation or research, social workers should ensure that participants provide informed consent for the use of such technology. Social workers should assess whether participants are able to use the technology and, when appropriate, offer reasonable alternatives to participate in the evaluation or research.

- (g) When evaluation or research participants are incapable of giving informed consent, social workers should provide an appropriate explanation to the participants, obtain the participants’ assent to the extent they are able, and obtain written consent from an appropriate proxy.

- (h) Social workers should never design or conduct evaluation or research that does not use consent procedures, such as certain forms of naturalistic observation and archival research, unless rigorous and responsible review of the research has found it to be justified because of its prospective scientific, educational, or applied value and unless equally effective alternative procedures that do not involve waiver of consent are not feasible.

- (i) Social workers should inform participants of their right to withdraw from evaluation and research at any time without penalty.

- (j) Social workers should take appropriate steps to ensure that participants in evaluation and research have access to appropriate supportive services.

- (k) Social workers engaged in evaluation or research should protect participants from unwarranted physical or mental distress, harm, danger, or deprivation.

- (l) Social workers engaged in the evaluation of services should discuss collected information only for professional purposes and only with people professionally concerned with this information.

- (m) Social workers engaged in evaluation or research should ensure the anonymity or confidentiality of participants and of the data obtained from them. Social workers should inform participants of any limits of confidentiality, the measures that will be taken to ensure confidentiality, and when any records containing research data will be destroyed.

- (n) Social workers who report evaluation and research results should protect participants’ confidentiality by omitting identifying information unless proper consent has been obtained authorizing disclosure.

- (o) Social workers should report evaluation and research findings accurately. They should not fabricate or falsify results and should take steps to correct any errors later found in published data using standard publication methods.

- (p) Social workers engaged in evaluation or research should be alert to and avoid conflicts of interest and dual relationships with participants, should inform participants when a real or potential conflict of interest arises, and should take steps to resolve the issue in a manner that makes participants’ interests primary.

- (q) Social workers should educate themselves, their students, and their colleagues about responsible research practices.

Together, these 14 statements reflect a responsibility for social workers to :

- participate in appropriate Institutional Review Board (IRB) procedures,

- ensure the safety and protection of participants in social work research and evaluation studies,

- engage in effective informed consent procedures,

- responsibly utilize information technology in research,

- collect and discuss only information relevant to the study,

- preserve participant privacy and confidentiality (or anonymity),

- engage in research with integrity,

- prevent or responsibly resolve conflict of interest instances, and

- remain informed about responsible research practices.

Social Work 3401 Coursebook Copyright © by Dr. Audrey Begun is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

9 3.2 Specific ethical issues to consider

Learning objectives.

- Define informed consent, and describe how it works

- Identify the unique concerns related to the study of vulnerable populations

- Differentiate between anonymity and confidentiality

- Explain the ethical responsibilities of social workers conducting research

- Identify the unique ethical concern posed by internet research

As should be clear by now, conducting research on humans presents a number of unique ethical considerations. Human research subjects must be given the opportunity to consent to their participation in research, fully informed of the study’s risks, benefits, and purpose. Further, subjects’ identities and the information they share should be protected by researchers. Of course, how consent and identity protection are defined may vary by individual researcher, institution, or academic discipline. In section 3.1, we examined the role that institutions play in shaping research ethics. In this section, we’ll take a look at a few specific topics that individual researchers and social workers in general must consider before embarking on research with human subjects.

Informed consent

A norm of voluntary participation is presumed in all social work research projects. In other words, we cannot force anyone to participate in our research without that person’s knowledge or consent (so much for that Truman Show experiment). Researchers must therefore design procedures to obtain subjects’ informed consent to participate in their research. Informed consent is defined as a subject’s voluntary agreement to participate in research based on a full understanding of the research and of the possible risks and benefits involved. Although it sounds simple, ensuring that one has actually obtained informed consent is a much more complex process than you might initially presume.

The first requirement is that, in giving their informed consent, subjects may neither waive nor even appear to waive any of their legal rights. Subjects also cannot release a researcher, her sponsor, or institution from any legal liability should something go wrong during the course of their participation in the research (USDHHS,2009). [1] Because social work research does not typically involve asking subjects to place themselves at risk of physical harm by, for example, taking untested drugs or consenting to new medical procedures, social work researchers do not often worry about potential liability associated with their research projects. However, their research may involve other types of risks.

For example, what if a social work researcher fails to sufficiently conceal the identity of a subject who admits to participating in a local swinger’s club? In this case, a violation of confidentiality may negatively affect the participant’s social standing, marriage, custody rights, or employment. Social work research may also involve asking about intimately personal topics, such as trauma or suicide that may be difficult for participants to discuss. Participants may re-experience traumatic events and symptoms when they participate in a study. Even if you are careful to fully inform your participants of all risks before they consent to the research process, you can probably empathize with participants thinking they could bear talking about a difficult topic and then finding it too overwhelming once they start. In cases like these, it is important for a social work researcher to have a plan to provide supports. This may mean providing referrals to counseling supports in the community or even calling the police if the participant is an imminent danger to themselves or others.

It is vital that social work researchers explain their mandatory reporting duties in the consent form and ensure participants understand them before they participate. Researchers should also emphasize to participants that they can stop the research process at any time or decide to withdraw from the research study for any reason. Importantly, it is not the job of the social work researcher to act as a clinician to the participant. While a supportive role is certainly appropriate for someone experiencing a mental health crisis, social workers must ethically avoid dual roles. Referring a participant in crisis to other mental health professionals who may be better able to help them is preferred.

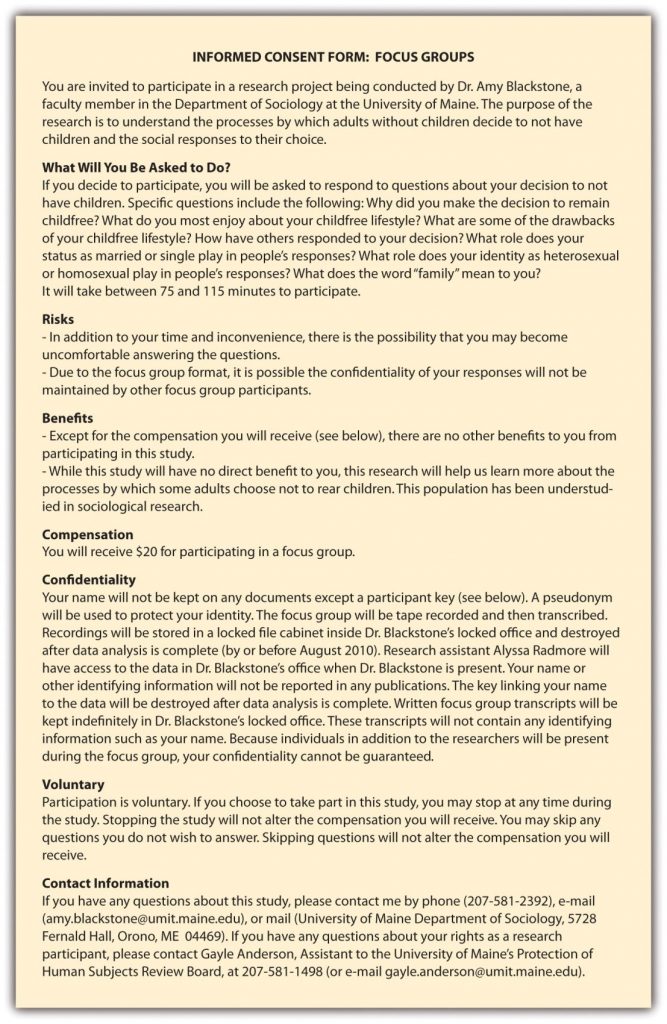

Beyond the legal issues, most IRBs require researchers to share some details about the purpose of the research, possible benefits of participation, and, most importantly, possible risks associated with participating in that research with their subjects. In addition, researchers must describe how they will protect subjects’ identities; how, where, and for how long any data collected will be stored; and whom to contact for additional information about the study or about subjects’ rights. All this information is typically shared in an informed consent form that researchers provide to subjects. In some cases, subjects are asked to sign the consent form indicating that they have read it and fully understand its contents. In other cases, subjects are simply provided a copy of the consent form and researchers are responsible for making sure that subjects have read and understand the form before proceeding with any kind of data collection. Figure 3.1 showcases a sample informed consent form from a research project on child-free adults. Note that this consent form describes a risk that may be unique to the particular method of data collection being employed: focus groups.

One last point to consider when preparing to obtain informed consent is that not all potential research subjects are considered equally competent or legally allowed to consent to participate in research. Subjects from vulnerable populations may be at risk of experiencing undue influence or coercion. [2] The rules for consent are more stringent for vulnerable populations. For example, minors must have the consent of a legal guardian in order to participate in research. In some cases, the minors themselves are also asked to participate in the consent process by signing special, age-appropriate “assent” forms designed specifically for them. Prisoners and parolees also qualify as vulnerable populations. Concern about the vulnerability of these subjects comes from the very real possibility that prisoners and parolees could perceive that they will receive some highly desired reward, such as early release, if they participate in research. Another potential concern regarding vulnerable populations is that they may be underrepresented in research, and even denied potential benefits of participation in research, specifically because of concerns about their ability to consent. So, on the one hand, researchers must take extra care to ensure that their procedures for obtaining consent from vulnerable populations are not coercive. The procedures for receiving approval to conduct research on these groups may be more rigorous than that for non-vulnerable populations. On the other hand, researchers must work to avoid excluding members of vulnerable populations from participation simply on the grounds that they are vulnerable or that obtaining their consent may be more complex. While there is no easy solution to this double-edged sword, an awareness of the potential concerns associated with research on vulnerable populations is important for identifying whatever solution is most appropriate for a specific case.

Protection of identities

As mentioned earlier, the informed consent process includes the requirement that researchers outline how they will protect the identities of subjects. This aspect of the process, however, is one of the most commonly misunderstood aspects of research.

In protecting subjects’ identities, researchers typically promise to maintain either the anonymity or confidentiality of their research subjects. Anonymity is the more stringent of the two. When a researcher promises anonymity to participants, not even the researcher is able to link participants’ data with their identities. Anonymity may be impossible for some social work researchers to promise because several of the modes of data collection that social workers employ. Face-to-face interviewing means that subjects will be visible to researchers and will hold a conversation, making anonymity impossible. In other cases, the researcher may have a signed consent form or obtain personal information on a survey and will therefore know the identities of their research participants. In these cases, a researcher should be able to at least promise confidentiality to participants.

Offering confidentiality means that some identifying information on one’s subjects is known and may be kept, but only the researcher can link participants with their data and she promises not to do so publicly. Confidentiality in research is quite similar to confidentiality in clinical practice. You know who your clients are, but others do not. You agree to keep their information and identity private. As you can see under the “Risks” section of the consent form in Figure 3.1, sometimes it is not even possible to promise that a subject’s confidentiality will be maintained. This is the case if data are collected in public or in the presence of other research participants (e.g., in the course of a focus group). Participants who social work researchers deem to be of imminent danger to self or others or those that disclose abuse of children and other vulnerable populations fall under a social worker’s duty to report. Researchers must then violate confidentiality to fulfill their legal obligations.

Protecting research participants’ identities is not always a simple prospect, especially for those conducting research on stigmatized groups or illegal behaviors. Sociologist Scott DeMuth learned that all too well when conducting his dissertation research on a group of animal rights activists. As a participant observer, DeMuth knew the identities of his research subjects. So when some of his research subjects vandalized facilities and removed animals from several research labs at the University of Iowa, a grand jury called on Mr. DeMuth to reveal the identities of the participants in the raid. When DeMuth refused to do so, he was jailed briefly and then charged with conspiracy to commit animal enterprise terrorism and cause damage to the animal enterprise (Jaschik, 2009).

Publicly, DeMuth’s case raised many of the same questions as Laud Humphreys’ work 40 years earlier. What do social scientists owe the public? Is DeMuth, by protecting his research subjects, harming those whose labs were vandalized? Is he harming the taxpayers who funded those labs? Or is it more important that DeMuth emphasize what he owes his research subjects, who were told their identities would be protected? DeMuth’s case also sparked controversy among academics, some of whom thought that as an academic himself, DeMuth should have been more sympathetic to the plight of the faculty and students who lost years of research as a result of the attack on their labs. Many others stood by DeMuth, arguing that the personal and academic freedom of scholars must be protected whether we support their research topics and subjects or not. DeMuth’s academic adviser even created a new group, Scholars for Academic Justice , to support DeMuth and other academics who face persecution or prosecution as a result of the research they conduct. What do you think? Should DeMuth have revealed the identities of his research subjects? Why or why not?

social work ethics and research

Often times, specific disciplines will provide their own set of guidelines for protecting research subjects and, more generally, for conducting ethical research. For social workers, the National Association of Social Workers (NASW) Code of Ethics section 5.02 describes the responsibilities of social workers in conducting research. Summarized below, these responsibilities are framed as part of a social worker’s responsibility to the profession. As representative of the social work profession, it is your responsibility to conduct and use research in an ethical manner.

A social worker should:

- Monitor and evaluate policies, programs, and practice interventions

- Contribute to the development of knowledge through research

- Keep current with the best available research evidence to inform practice

- Ensure voluntary and fully informed consent of all participants

- Not engage in any deception in the research process

- Allow participants to withdraw from the study at any time

- Provide access for participants to appropriate supportive services

- Protect research participants from harm

- Maintain confidentiality

- Report findings accurately

- Disclose any conflicts of interest

internet researcH

It is increasingly common for the internet to be used as a tool for conducting research and as a source of data such as the content of websites, blogs, or discussion boards. Research ethical principles apply to internet research, but there are ethical considerations that are unique to internet research.

Some of the major tensions and considerations of internet research include defining human subjects, differentiating between what is public and what is private, and making appropriate distinctions between individuals and data. These tensions lead to new concerns about informed consent, confidentiality, privacy, and harm when conducting internet research. These are important considerations because they link to the fundamental ethical principle of minimizing harm. Does the connection between one’s online data and his or her physical person enable psychological, economic, or physical, harm?

- Defining Human Subjects: In internet research, “human subject” has never been a good fit for describing many internet-based research environments. For example, should authors of web content be considered human subjects? This question is important because many regulatory bodies do not conduct ethical reviews if they determine that the research does not involve human subjects. Internet researchers have not reached a consensus about how to define the term “human subjects.” In fact, some contend that defining human subjects may not be as important as defining other terms such as harm, vulnerability, personally identifiable information, and so forth.

- Differentiating between Public and Private: Individual and cultural definitions and expectations of privacy are ambiguous, contested, and changing. On the internet, people may operate in public spaces but maintain strong perceptions or expectations of privacy. Or, they may acknowledge that the substance of their communication is public, but that the specific context in which it appears implies restrictions on how that information is – or should be – used by other parties. For example, a user may feel comfortable broadcasting tweets to a public audience, following the norms of the Twitter community. However, to find out that these ‘public’ tweets had been collected within a data set and combed over by a researcher could possibly feel like an encroachment on privacy. Despite what a simplified conceptualization of “public/private” might offer, there is no categorical way to discern all eventual harm. Data aggregators or search tools make information accessible to a wider public than what might have been originally intended. Social, academic, or regulatory delineations of public and private as a clearly recognizable binary no longer holds in everyday practice.

- Distinctions between individuals and data: The internet complicates the fundamental research ethics question of personhood. Is an avatar a person? Is one’s digital information an extension of the self? In the U.S. regulatory system, the primary question has generally been: Are we working with human subjects or not? If information is collected directly from individuals, such as an email exchange, instant message, or an interview in a virtual world, we are likely to naturally define the research scenario as one that involves a person. If the connection between the object of research and the person who produced it is indistinct, there may be a tendency to define the research scenario as one that does not involve any persons. This may oversimplify the situation–the question of whether one is dealing with a human subject is different from the question about whether information is linked to individuals: Can we assume a person is wholly removed from large data pools? For example, a data set containing thousands of tweets or an aggregation of surfing behaviors collected from a bot is perhaps far removed from the persons who engaged in these activities. In these scenarios, it is possible to forget that there was ever a person somewhere in the process that could be directly or indirectly impacted by the research. Yet there is considerable evidence that even ‘anonymized’ datasets that contain enough personal information can result in individuals being identifiable. Scholars and technologists continue to wrestle with how to adequately protect individuals when analyzing such datasets (Sweeny, 2009; Narayanan & Shmatikov, 2008, 2009).

These three issues represent ongoing tensions for internet research. Although researchers might like straightforward answers to questions such as “Will capturing a person’s Tweets cause them harm?” or “Is a blog a public or private space,” the uniqueness and almost endless range of specific situations has defied attempts to provide universal answers. The Association of Internet Researchers (Markham & Buchanan, 2012) has created a guide called Ethical Decision-Making and Internet Research that provides a detailed discussion of these issues.

Key Takeaways

- Researchers must obtain the informed consent of the people who participate in their research.

- Social workers must take steps to minimize the harms that could arise during the research process.

- If a researcher promises anonymity, she cannot link individual participants with their data.

- If a researcher promises confidentiality, she promises not to reveal the identities of research participants, even though she can link individual participants with their data.

- The NASW Code of Ethics includes specific responsibilities for social work researchers.

- Internet research is increasingly common and has its own unique set of ethical considerations.

- Anonymity- the identity of research participants is not known to researchers

- Confidentiality- identifying information about research participants is known to the researchers but is not divulged to anyone else

- Informed consent- a research subject’s voluntary agreement to participate in a study based on a full understanding of the study and of the possible risks and benefits involved

Image attributions

consent by Catkin CC-0

Figure 3.1 is copied from Blackstone, A. (2012) Principles of sociological inquiry: Qualitative and quantitative methods. Saylor Foundation. Retrieved from: https://saylordotorg.github.io/text_principles-of-sociological-inquiry-qualitative-and-quantitative-methods/ Shared under CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0 License

Anonymous by kalhh CC-0

- The full set of requirements for informed consent can be read online at the Office for Human Research Protections . ↵

- The guidelines on vulnerable populations can be read online at the the US Department of Health and Human Services’ . ↵

Foundations of Social Work Research Copyright © 2020 by Rebecca L. Mauldin is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Open access

- Published: 07 August 2024

Ethical considerations in public engagement: developing tools for assessing the boundaries of research and involvement

- Jaime Garcia-Iglesias 1 ,

- Iona Beange 2 ,

- Donald Davidson 2 ,

- Suzanne Goopy 3 ,

- Huayi Huang 3 ,

- Fiona Murray 4 ,

- Carol Porteous 5 ,

- Elizabeth Stevenson 6 ,

- Sinead Rhodes 7 ,

- Faye Watson 8 &

- Sue Fletcher-Watson 7

Research Involvement and Engagement volume 10 , Article number: 83 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

687 Accesses

21 Altmetric

Metrics details

Public engagement with research (PEwR) has become increasingly integral to research practices. This paper explores the process and outcomes of a collaborative effort to address the ethical implications of PEwR activities and develop tools to navigate them within the context of a University Medical School. The activities this paper reflects on aimed to establish boundaries between research data collection and PEwR activities, support colleagues in identifying the ethical considerations relevant to their planned activities, and build confidence and capacity among staff to conduct PEwR projects. The development process involved the creation of a taxonomy outlining key terms used in PEwR work, a self-assessment tool to evaluate the need for formal ethical review, and a code of conduct for ethical PEwR. These tools were refined through iterative discussions and feedback from stakeholders, resulting in practical guidance for researchers navigating the ethical complexities of PEwR. Additionally, reflective prompts were developed to guide researchers in planning and conducting engagement activities, addressing a crucial aspect often overlooked in formal ethical review processes. The paper reflects on the broader regulatory landscape and the limitations of existing approval and governance processes, and prompts critical reflection on the compatibility of formal approval processes with the ethos of PEwR. Overall, the paper offers insights and practical guidance for researchers and institutions grappling with ethical considerations in PEwR, contributing to the ongoing conversation surrounding responsible research practices.

Plain English summary

This paper talks about making research fairer for everyone involved. Sometimes, researchers ask members of the public for advice, guidance or insight, or for help to design or do research, this is sometimes known as ‘public engagement with research’. But figuring out how to do this in a fair and respectful way can be tricky. In this paper, we discuss how we tried to make some helpful tools. These tools help researchers decide if they need to get formal permission, known as ethical approval, for their work when they are engaging with members of the public or communities. They also give tips on how to do the work in a good and fair way. We produced three main tools. One helps people understand the important words used in this kind of work (known as a taxonomy). Another tool helps researchers decide if they need to ask for special permission (a self-assessment tool). And the last tool gives guidelines on how to do the work in a respectful way (a code of conduct). These tools are meant to help researchers do their work better and treat everyone involved fairly. The paper also talks about how more work is needed in the area, but these tools are a good start to making research fairer and more respectful for everyone.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

In recent decades, “public involvement in research” has experienced significant development, becoming an essential element of the research landscape. In fact, it has been argued, public involvement may make research better and more relevant [ 7 , p. 1]. Patients’ roles, traditionally study participants, have transformed to become “active partners and co-designers” [ 17 , p. 1]. This evolution has led to the appearance of a multitude of definitions and terms to refer to these activities. In the UK, the National Co-ordinating Centre for Public Engagement, defines public engagement as the “many ways organisations seek to involve the public in their work” [ 9 ]. In this paper, we also refer to “public involvement,” which is defined as “research being carried out ‘with’ or ‘by’ members of the public rather than ‘to’, ‘about’ or ‘for’ them” (UK Standards for Public Involvement). Further to this, the Health Research Authority (also in the UK), defines public engagement with research as “all the ways in which the research community works together with people including patients, carers, advocates, service users and members of the community” [ 6 ]; [ 9 ]. These terms encompass a wide variety of theorizations, levels of engagement, and terminology, such as ‘patient-oriented research’, ‘participatory’ research or services or ‘patient engagement’ [ 17 , p. 2]. For this paper, we use the term ‘public engagement with research’ or PEwR in this way.

Institutions have been set up to support PEwR activities. In the UK these include the UK Standards for Public Involvement in Research (supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Research), INVOLVE, and the National Coordinating Centre for Public Engagement (NCCPE). Most recently, in 2023, the UK’s largest funders and healthcare bodies signed a joint statement “to improve the extent and quality of public involvement across the sector so that it is consistently excellent” [ 6 ]. In turn, this has often translated to public engagement becoming a requisite for securing research funding or institutional ethical permissions [ 3 , p. 2], as well as reporting and publishing research [ 15 ]. Despite this welcomed infrastructure to support PEwR, there remain gaps in knowledge and standards in the delivery of PEwR. One such gap concerns the extent to which PEwR should be subject to formal ethical review in the same way as data collection for research.

In 2016, the UK Health Research Authority and INVOLVE published a joint statement suggesting that “involving the public in the design and development of research does not generally raise any ethical concerns” [ 7 , p. 2]. We presume that this statement is using the phrase ‘ethical concerns’ to narrowly refer to the kinds of concerns addressed by a formal research ethics review process, such as safeguarding, withdrawal from research, etc. Footnote 1 . To such an extent, we agree that public involvement with research is not inherently ‘riskier’ than other research activities.

Furthermore, a blanket need for formal ethical review risks demoting or disempowering non-academic contributors from the roles of consultants, co-researchers, or advisors to a more passive status as participants. Attending a meeting as an expert, discussing new project ideas, setting priorities, designing studies and, or interpreting findings does not require that we sign a consent form. Indeed, to do so clearly removes the locus of power away from the person signing and into the hands of the person who wrote the consent form. This particular risk is exacerbated when institutional, formal ethical review processes operate in complex, convoluted and obscure ways that often baffle researchers let alone members of the public.

However, we also recognize that PEwR is not without potential to do harm – something which formal research ethics review aims to anticipate and minimise. For example, a public lecture or a workshop could cause distress to audience members or participants if they learn for the first time that aspects of their lifestyle or personal history put them at higher risk of dementia. When patients are invited to join advisory panels, they may feel pressure to reveal personal details about their medical history to reinforce their expertise or legitimise their presence – especially in a room where most other people have potentially intimidating professional qualifications. Some patient groups may be exploited, if research involvement roles are positioned as an opportunity, or even a duty, and not properly reimbursed. When patients are more deeply involved in research roles, such as collecting or analysing data, they might experience distress, particularly if interacting with participants triggers their own painful or emotional memories [ 14 , p. 98]. Thus, at all levels of PEwR from science communication to embedded co-production, there is a danger of harm to patients or members of the public, and a duty of care on the part of the research team and broader institution who invited them in.

These concerns are not accessory to PEwR activities but rather exist at their heart. Following a review on the impacts of public engagement, Brett et al. conclude that “developing a wide view which considers the impact of PPI [public and patient involvement] on the people involved in the process can be critical to our understanding of why some studies that involve patients and the public thrive, while others fail” [ 1 , p. 388]. Despite the importance of these considerations, there is a stark absence of consistent guidance as to whether different forms of PEwR require formal ethical review. Nor is there, to our knowledge, any sustained attempt to provide a framework for ethical conduct of PEwR in the absence of formal review (see Pandya-Wood et al. [ 11 ]; Greenhalgh et al. [ 5 ]). This is, in part, due to there being a wide heterogeneity of practices, communities, and levels of engagement [ 8 , p. 6] that resists generalizable principles or frameworks.

The lack of frameworks about whether or how PEwR requires formal ethical review can, ironically, be a key barrier to PEwR happening. In our work as members of a university ethics review committee, we have found this lack of guidance to hamper appropriate ethical PEwR in several ways. Researchers may avoid developing PEwR initiatives altogether for fear of having to spend time or resources in securing formal ethical review (especially when this process is lengthy or resource-intensive). Likewise, they may avoid PEwR for fear that its conduction would be unethical. On the other hand, others could assume that the lack of a requirement for formal ethical review means there are no ethical issues or risks involved in PEwR.

Similarly, experts in PEwR who are not experienced with formal research ethics review may face barriers as their PEwR process becomes more elaborate, in-depth, or complex. For example, although a priority-setting exercise with members of an online community of people with depression was assessed as not requiring ethics review, the funding panel requested that formal ethics review be undergone for a follow-up exercised aimed at collecting data answering one of the priority questions identified in the previous priority-setting. It is crucial that innovations in PEwR and findings from this work are shared and yet academic teams may be unable to publish their work in certain journals which require evidence of having undergone formal ethical review. Finally, ethics committees such as ours often must rely on anecdotal knowledge to make judgements about what does or does not require formal ethical review, given the absence of standardized frameworks.

About this paper

In this paper, we report and reflect on the development of specific tools and processes for assessing the ethical needs of PEwR initiatives, as members of an ethics review committee for a large University medical school. These tools aim to delineate boundaries between research data collection and PEwR activities of various kinds, provide a self-assessment framework for ethical practice in PEwR and, overall, give people greater confidence when conducting PEwR work. We describe and critically reflect on the development of the following resources:

a taxonomy to define key terms relating to PEwR with associated resource recommendations.

a self-assessment tool to support people understanding where their planned activities fall in relation to research or PEwR.

a code of conduct for ethical conduct of PEwR (appended to the self-assessment tool).

We will, first, describe our work as part of an institutional ethics committee, the identification of a need for specific guidance, and our key assumptions; we will then describe the process of developing these tools and processes; provide an overview of the tools themselves; and reflect on early feedback received and future work needed.

Developing specific tools for PEWR in ethics

Identifying needs, goals and outputs.

The Edinburgh Medical School Research Ethics Committee (EMREC) provides ethical opinions to members of staff and postgraduate researchers within the University of Edinburgh Medical School in relation to planned research to be conducted on humans i.e. their data, or tissues. These research activities come from a wide range of disciplines, including public health, epidemiology, social science or psychology. EMREC does not review research that involves recruitment of NHS patients, use of NHS data, or other health service resources: such projects are evaluated by an NHS research ethics committee. EMREC is led by two co-directors and formed of over 38 members, which include experienced academics and academic-clinicians from a variety of disciplines. There are also 2–4 lay members who are not researchers.

EMREC receives regular enquiries about whether a specific piece of PEwR work (such as holding a workshop with people living with endometriosis to identify research priorities or interviewing HIV activists about their work during COVID-19) requires formal ethics review. In addition, often teams contact EMREC following completion of a PEwR activity that they want to publish because the journal in which they wish to publish has requested evidence of the work having undergone formal ethics approval. These enquiries are happening in the context of an institutional investment in staffing, leading to a significant degree of distributed expertise across the Medical School about diverse forms of PEwR.

Responding to this, in the summer of 2022, a Public and Patient Involvement and Engagement working group was formed by EMREC with the aim of developing new tools and processes to navigate the ethical implications of PEWR within the University of Edinburgh Medical School. The group’s original understandings were that:

PEwR is both important and skilled work that presents a unique set of ethical implications,

PEwR is a fragmented landscape where many people have relevant but different expertise and where a wide range of terminology is in use, and.

there is no existing widely-agreed framework for ethical PEwR.

This working group was designed to be temporary, lasting approximately six months. It was composed of eleven members with different degrees of seniority and disciplinary backgrounds - both members of EMREC and those from other parts of the Medical School, and other parts of the University of Edinburgh. Among these, there were both academics and PEwR experts in professional services (i.e. primarily non-academic) roles. The working group met four times (August, September and November 2022; and January 2023).

The group identified three key goals and, in relation to these, key outputs needed. The goals were: (1) help establish boundaries between research data collection (requiring an ethical opinion from EMREC) and PEwR activities of various kinds (requiring ethical reflection/practice but not a formal EMREC ethical opinion), (2) support colleagues to identify where their planned activities fell in the research-PEwR continuum and consequently the relevant ethical framework, and (3) identify ways of building confidence and capacity among staff to conduct PEwR projects. In relation to these goals, the working group initially agreed on producing the following key outputs:

A taxonomy outlining and defining key terms used in the PEwR work, with examples. While not universal or definitive, the taxonomy should help colleagues identify and label their activities and help determine the ethical considerations that would apply to conduct the work with integrity. It would also facilitate conversations between staff with varying levels and types of experience, and ensure that decisions around ethical conduct would be based on more than choice of terminology.

A self-assessment tool to provide a more systematic way to evaluate whether a given academic activity, involving a non-academic partner (organisation or individual) requires formal evaluation by a research ethics committee.

A list of resources collected both from within and beyond our institution that are relevant to the issue of ethics and PEwR and can serve as ‘further reading’ and training.

While we aimed to develop this work with a view to it being useful within the remit of the University of Edinburgh Medical School, we also understood that there was significant potential for these outputs to be of interest and relevance more widely. In this way, we aimed to position them as a pragmatic addition to existing guidance and resources, such as the NIHR Reflective Questions [ 2 ].

Our process

Across the first three meetings, the group worked together on the simultaneous development of the three outputs (taxonomy, self-assessment tool, and resources). The initial taxonomy was informed by the guidance produced by the Public Involvement Resource Hub at Imperial College London [ 10 ]. The taxonomy was developed as a table that included key terms (such as ‘public engagement’, ‘co-production’, or ‘market research’), with their definitions, examples, and synonyms. From early on, it was decided that different key terms would not be defined by the methods used, as there could be significant overlap among these – e.g. something called a focus group might be a part of a consultation, market research or research data collection.

A draft table (with just six categories) was presented in the first meeting and group members were asked to work on the table between meetings, including providing additional examples, amending language, or any other suggestions. This was done on a shared document using ‘comments’ so that contradictory views could be identified and agreements reached. The table was also shared with colleagues from outside the University of Edinburgh Medical School to capture the range of terminologies used across disciplines, recognising the interdisciplinary nature of much research.

Through this process, additional key terms were identified, such as “science communication” and “action research,” definitions were developed more fully, and synonyms were sometimes contextualized (by indicating, for example, shades of difference or usages specific to an area). Upon further work, three additional sections were added to the taxonomy tool: first, an introduction was developed that explained what terminology our specific institution used and noted that the boundaries between different terms were often “fuzzy and flexible.” In addition, the group agreed that it would be useful to provide a narrative example of how different forms of public engagement with research might co-exist and flow from one to another. To this end, a fictional example was developed where a team of clinical researchers interested in diabetes are described engaging in scoping work, research, co-production, science communication and action research at different times of their research programme. Finally, a section was also added that prompted researchers to reflect on the processes of negotiating how partners can be described in research (for example, whether to use terms such as ‘patient’ or ‘lay member’).

For the self-assessment tool, a first iteration was a table with two columns (one for research or work requiring formal ethical review and one for PEwR or work not requiring formal ethical review). The aim was for group members to fill the table with examples of activities that would fall under each category, with a view to identifying generalizable characteristics. However, this task proved complicated given the wide diversity of possible activities, multitude of contexts, and sheer number of exceptions. To address this, group members were asked to complete a case-based exercise. They were presented with the following situation: “I tell you I’m planning a focus group with some autistic folk” and asked how they would determine whether the activity would be a form of data collection for a research project (requiring formal ethical review) or another form of PEwR. Group members were asked, with a view to developing the self-assessment tool, to identify which questions they would ask to assess the activity. The replies of working group members were synthesized by one of the authors (SFW) and presented at the following meeting.

Through discussion as a group, we determined that the questions identified as useful in identifying if an activity required formal ethical review fell, roughly, under four main areas. Under each area, some indicators of activities were provided which were “less likely to need ethics review” and some “more likely to need ethics review”. The four umbrella questions were:

What is the purpose and the planned outcome of the activity? (see Table 1 for an excerpt of the initial draft answer to this question)

What is the status of the people involved in the activity? (indicators of less likely to need ethics review were “participants will be equal partners with academic team” or “participants will be advisors” and indicators more likely to require ethics approval were “participants will undertake tasks determined by academics” or “participants will contribute data or sign consent forms”).

What kind of information is being collected? (indicators of less likely to need ethics review were “asking about expert opinion on a topic” or “sessions will be minuted and notes taken” and indicators more likely to require ethics approval were “sessions will be recorded and transcribed” or “asking about participants’ personal experiences”).

What are the risks inherent in this activity? (indicators of less likely to need ethics review were “participants will be involved in decision-making” or “participants will be credited for their role in a manner of their choosing” and indicators more likely to require ethics approval were “participants’ involvement will and must be anonymized fully” or “participants have a choice between following protocol or withdrawing from the study”).

Upon further work, the group decided to modify this initial iteration in several ways leading to the final version. First, a brief introduction explaining the purpose of the tool was written. This included information about the aims of the tool, and a very brief overview of the process of formal research ethics review. It also emphasised the importance of discussion of the tool within the team, with PEwR experts and sometimes with EMREC members, depending on how clear-cut the outcome was. Second, we included brief information about what are ‘research’ and ‘public engagement with research’ with a view to supporting people who may not be familiar with how these concepts are used by ethics review committees (for example, lay co-applicants or co-researchers). Third, we included key guidance about how to use the tool, including ‘next steps’ if the activity was determined to be research or engagement. Importantly, this emphasised that none of the questions posed and indicators given were definitive of something needing or not needing formal research ethics review, but instead they should be used collectively to signpost a team towards, or away from, formal review.

Finally, while the four umbrella questions remained the same as in the previous iteration, the indicators under each were further refined. In discussing the previous version, the group agreed that, while some indicators could relate to an activity falling into either category (research or engagement) depending on other factors, there were others that were much more likely to fall under one category than the other. In other words, while no single indicator was deterministic of needing or not needing formal review, some indicators were more influential than others on the final self-assessment outcome. Thus, we divided the indicators associated with each umbrella question into two sub-groups. The more influential indicators were labelled as either “probably doesn’t need ethical review” or “almost certainly needs ethical review”. Less influential indicators were labelled as either “less likely to need ethical review” or “more likely to need ethical review.” This is shown in Table 2 .

This new format retains the awareness of the sometimes-blurry lines between research and PEwR for many activities, but also seeks to provide stronger direction through indicative activities that are more clear-cut, with a particular view to supporting early-career researchers and people new to ethics reviews and/or engagement processes.

A key concern of the group was what would happen next if a planned activity, using the self-assessment tool, was deemed as PEwR. The formal review process for research would not be available for a planned activity identified as PEwR i.e. completing a series of documents and a number of protocols to deal with issues such as data protection, safeguarding, etc. This would leave a vacuum in terms of guidance for ethical conduction of PEwR. The group was concerned that some people using the self-assessment tool might arrive at the conclusion that their planned activity was entirely without ethical risks, given that it was not required to undergo formal review. Others might be conscious of the risks but feel adrift as to how to proceed. This was a particular concern with early-career researchers and indeed established academics turning to PEwR for the first time: we wanted to facilitate their involvement with PEwR but we were also aware that many may lack experience and resources. To address this, the group decided to develop an additional output comprising a series of reflective prompts to guide researchers in planning and conducting engagement activities.

The prompts were organized under four headings. First, “Data Minimisation and Security” included information about required compliance with data protection legislation, suggestions about collecting and processing information, and ideas around ensuring confidentiality. Second, “Safeguarding Collaborators and Emotional Labour” prompted researchers to think about the risk of partners becoming distressed and suggested what things should be planned for in this regard. Third, “Professional Conduct and Intellectual Property” included advice on how to clearly manage partners’ expectations around their contributions, impact, and intellectual property. Finally, fourth, under “Power Imbalances”, the guidance discusses how researchers may work to address the inherent imbalances that exist in relationships with partners. It prompts the researcher to think about choice of location, information sharing, and authorship among others. While the Edinburgh Medical School Research Ethics Committee remains available for consultation on all these matters, as well as dedicated and professional PEwR staff, the group developed these guidelines with a view both to emphasizing the fact that an activity not requiring formal ethical review did not mean that the activity was absent of risk or did not require careful ethical planning; and to support those who may be unfamiliar with how to develop engagement activities. It was decided that this guideline should follow the self-assessment tool for clarity.