Case studies in child welfare

About this guide, child welfare case studies, real-life stories, and scenarios, social services and organizational case studies, other case studies, using case studies.

This guide is intended as a supplementary resource for staff at Children's Aid Societies and Indigenous Well-being Agencies. It is not intended as an authority on social work or legal practice, nor is it meant to be representative of all perspectives in child welfare. Staff are encouraged to think critically when reviewing publications and other materials, and to always confirm practice and policy at their agency.

Case studies and real-life stories can be a powerful tool for teaching and learning about child welfare issues and practice applications. This guide provides access to a variety of sources of social work case studies and scenarios, with a specific focus on child welfare and child welfare organizations.

- Real cases project Three case studies, drawn from the New York City Administration for Children's Services. Website also includes teaching guides

- Protective factors in practice vignettes These vignettes illustrate how multiple protective factors support and strengthen families who are experiencing stress. From the National Child Abuse Prevention Month website

- Child welfare case studies and competencies Each of these cases was developed, in partnership, by a faculty representative from an Alabama college or university social work education program and a social worker, with child welfare experience, from the Alabama Department of Human Resources

- Immigration in the child welfare system: Case studies Case studies related to immigrant children and families in the U.S. from the American Bar Association

- White privilege and racism in child welfare scenarios From the Center for Advanced Studies in Child Welfare more... less... https://web.archive.org/web/20190131213630/https://cascw.umn.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/WhitePrivilegeScenarios.pdf

- You decide: Would you remove these children from their families? Interactive piece from the Australian Broadcasting Corporation featuring cases based on real-life situations

- A case study involving complex trauma This case study complements a series of blog posts dedicated to the topic of complex trauma and how children learn to cope with complex trauma

- Fostering and adoption: Case studies Four case studies from Research in Practice (UK)

- Troubled families case studies This document describes how different families in the UK were helped through family intervention projects

- Parenting case studies From of the Pennsylvania Child Welfare Resource Center's training entitled "Understanding Reactive Attachment Disorder"

- Children’s Social Work Matters: Case studies Collections of narratives and case studies

- Race for Results case studies Series of case studies from the Annie E. Casey Foundation looking at ways of addressing racial inequities and supporting better outcomes for racialized children and communities

- Systems of care implementation case studies This report presents case studies that synthesize the findings, strategies, and approaches used by two grant communities to develop a principle-guided approach to child welfare service delivery for children and families more... less... https://web.archive.org/web/20190108153624/https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/ImplementationCaseStudies.pdf

- Child Outcomes Research Consortium: Case studies Case studies from the Child Outcomes Research Consortium, a membership organization in the UK that collects and uses evidence to improve children and young people’s mental health and well-being

- Social work practice with carers: Case studies

- Social Care Institute for Excellence: Case studies

- Learning to address implicit bias towards LGBTQ patients: Case scenarios [2018] more... less... https://web.archive.org/web/20190212165359/https://www.lgbthealtheducation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Implicit-Bias-Guide-2018_Final.pdf

- Using case studies to teach

- Last Updated: Aug 12, 2022 11:21 AM

- URL: https://oacas.libguides.com/case-studies

Children and the Child Welfare System: Problems, Interventions, and Lessons from Around the World

- Open access

- Published: 30 January 2021

- Volume 38 , pages 127–130, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Jarosław Przeperski ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5362-4170 1 &

- Samuel A. Owusu 1

13k Accesses

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Securing the welfare of children and the family is an integral part of social work. Modern society has experienced enormous changes that present both opportunities and challenges to the practice of social work to protect the welfare of children. It is thus essential that we understand the experiences of social work practitioners in different parts of the world in order to adapt practice to the changing times. To help achieve this, we present a collection of papers from around the world that presents findings on various aspects of social work research and practice involving children and the potential for improved service delivery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Social Work and Child Well-Being

Moving from Risk to Safety: Work with Children and Families in Child Welfare Contexts

Understanding and Promoting Child Wellbeing After Child Welfare System Involvement: Progress Made and Challenges Ahead

Sarah A. Font & John D. Fluke

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The protection of children’s welfare in many parts of the world involve different institutions and professionals ranging from social workers to the police, courts, schools, health centers, among others. In the course of their duties, some form of collaboration to varying degrees occur between these institutions and professionals in order to secure the welfare of children (Lalayants, 2008 ).

The child welfare system and social work particularly, has been observed to have undergone complex changes from its inception till now (Bamford, 2015 ; McNutt, 2013 ; Mendes, 2005 ; Stuart, 2013 ). Historically, the family and the local community were in many societies, solely responsible for a child’s well-being. When in crisis, the family including the wider extended family, was primarily responsible for supporting the child and solving their problems.

In response to wider changes in contemporary society, the child welfare system has increased the involvement of aid institutions protecting the welfare of children while reducing the role of the family. The family as a unit has also undergone changes, from the involvement of a broader network of relatives and the local community to the dominance of the nuclear family. Family ties have been weakened in many societies and the way the family unit functions has changed. Many children experience problems that often exceed the capacity of help available to these nuclear families. This has made it necessary to involve professional institutions (education, health, etc.) to aid in other areas outside of their core mandates to ensure children are secure, healthy, fed, and entertained and also to help families regain their own strength.

Although certain challenges to child welfare have persisted over time, children in contemporary times face some threats to their welfare unique to the times. Advancement in technology on one hand presents novel problems such as internet-use addictions and extensive means of child exploitation whiles on the other hand, these advancements in technology also provide opportunities to reach more clients effectively, gather data for analysis, and monitor and assess the performance of workers as well as the effectiveness of services. Modern ICT tools (such as online platforms and mobile applications) provide more flexibility in engagement between social workers and clients and the frequency of such meetings or engagements. However, an uncritical over-reliance on these tools presents other problems. Some social workers may be prone to avoid difficult situations involving uncooperative or violent families (Cooper, 2005 ) and an over-reliance on online meetings may worsened such cases, leaving vulnerable children unprotected.

All around the world, differences exist in the degree of exposure and the severity of problems facing children based on their age group (infants, toddlers, teens, and, youth), gender, geography, economic background, and culture. For instance, among the genders, differences exist in the probability of falling victim to child sexual abuse (Wellman, 1993 ) and the consequences of such victimization (Asscher, Van der Put, & Stams, 2015 ). Children from poor families are more at risk of being involved with the welfare system in certain countries (Fong, 2017 ) while poor and developing countries lack some resources needed to support children and families compared to more developed and richer countries. In addition, cultural attitudes towards parenting in different parts of the world may exacerbate the problems of child neglect, corporal punishment, and other forms of abuse.

To ensure that social workers are better equipped to deal with the daunting task of protecting the welfare of children, reforms have been proposed which are aimed at improving on the knowledge and skills of social workers, instituting standards of practice based on data, striving for continuous excellence in organizations (Cahalane, 2013 ) among others. The social work interventions aimed at improving the welfare of children of any given society can be affected by political, cultural, and socio-economic factors and this needs to be understood and addressed during the design, implementation, and assessment stages of interventions. Reisch and Jani ( 2012 ) describe how politics affect the development of social programs at the macro and micro levels, workplace decision-making processes, and resource allocation for agencies and clients.

With the aim of understanding the various challenges facing social work and the child welfare system around the world and the existing opportunities to address them, several papers on varying topics related to child welfare have been collated into this special issue. The contributors come from Asia, Africa, North America, and Europe and present the results of research into different areas affecting child welfare, child welfare workers and institutions, and interventions. Many lessons can be learnt from understanding the problems facing children and their families from around the world, the services and interventions instituted to combat such problems, the state of mind of children and their relationships with others, and the potentials of modern tools to improve service delivery in the child welfare sector.

In the special issue, Filippelli, Fallon, Lwin and Gantous ( 2021 ) present the paper, “Infants and Toddlers Investigated by The Child Welfare System: Exploring the Decision to Provide Ongoing Child Welfare Services”. Following the concerns of limited research into decision-making process of young children involved in the welfare system, the authors aimed to contribute to the literature on cases of maltreatment of young children and decisions to address them. The authors sought to answer the questions of the character of investigations of alleged child maltreatment, what factors influence decisions to recommend welfare service provision, and what differences may exist between cases involving infants and toddlers. After reviewing data on investigations into suspected cases of child maltreatment in Canada, it was determined that assessment by welfare workers and the mental health of caregivers are important indicators of decisions to transfer cases for further services. For cases involving infants, results indicate caregiver characteristics and household income are unique factors influencing decision-making while in toddler-involved cases, the toddler and the caregiver characteristics are factors that affect decisions.

Van Dam, Heijmans, and Stams ( 2021 ) aimed to determine the long-term effect of the intervention program, Youth Initiated Mentoring (YIM) organized in the Netherlands. They sought to find out how the mentors and the youth mentees were doing several months or years after the program and their impression of the whole program. In the paper “Youth Initiated Mentoring in Social Work: Sustainable Solution for Youth with Complex Needs?”, they show some findings on the present situation of mentees, the quality and trajectory of mentor–mentee relationships, and the level of support from social workers. Results indicate a sustained relationship between majority of the mentors and mentees and a reduction in the likelihood of out-of-home placement among other long-term benefits. The authors offer some recommendations for future research into Youth Initiated Mentoring.

Mackrill and Svendsen ( 2021 ) in the paper, “Implementing Routine Outcome Monitoring in Statutory Children’s Services” highlights the outcome of a 2-year long study on the effect of implementing a feedback-informed approach to family service provision in Denmark. In the study, they sought to understand how the feedback informed approach assisted in protecting children and families and what gaps exist in the service delivery chain. This involved analyzing by means of a constructivist grounded theory approach, anonymized data derived from field notes and interviews of various stakeholders. They report that the feedback-oriented approach helped service workers to follow legal directives especially in areas of assessment, care planning and follow-up, as well as in their approach to interviewing children. On the other hand, they assert that this approach to service delivery fails to emphasize attention to risk especially within families and the rights of clients to legal advice and recourse, among other issues. They offer some recommendations to address some of the identified challenges.

In order to understand the perceptions of the youth about older people with regards to healthcare and social help so that resources to address any existing negative stereotypes can be identified, Kanios ( 2021 ) surveyed 1084 school-going young people in Poland. Findings of this survey are presented in the paper titled “Beliefs of Secondary School Youth and Higher Education Students About Elderly Persons: A Comparative Survey”. Results show varied beliefs about older people regarding healthcare and social help among Secondary School Youth and Higher Education Students. Most of the respondents from both groups held no stereotypical views of older people. Students in higher education especially were found to maintain a more mature outlook on older people. Kanios concludes the paper with some recommendations of educational interest to combat existing negative stereotypes of older people.

Frimpong-Manso ( 2021 ) aimed to understand the views of social workers in Ghana on the benefits of intervention programs that strengthen families and to identify any existing barriers to their successful implementation in his paper, “Family Support Services in The Context of Child Care Reform: Perspectives of Ghanaian Social Workers”. Qualitative data derived from interviews with social workers point to some benefits of the existing family support services such as capacity building and wellbeing promotion of the families. Some identified challenges to success include inadequate funding and poor interagency cooperation.

Odrowąż-Coates and Kostrzewska ( 2021 ) from Poland present an analysis of the indicators of successful and fulfilling teenage motherhood in their paper titled “A Retrospective on Teenage Pregnancy in Poland. Focusing on Empowerment and Support Variables to Challenge Stereotyping in the Context of Social Work”. With the aim of showcasing positive cases of teenage motherhood as a means of empowerment and a way to tackle stereotypes in Poland, the authors utilized data from interviews and field practice notes involving teenage mothers and family court curators. Findings from this study show these teenage mothers to be empowered, independent, persevering, and with agency. Resources available through social work interventions and other support systems are also highlighted. The authors emphasize the need to show the positive life experiences of teenage mothers and the social work programs that contribute towards that in order to dispel existing stereotypes.

Abu Bakar Ah et al. ( 2021 ) in their paper, “Material Deprivation Status of Malaysian Children from Low-Income Families” relied on data from a self-reported survey of 360 poor children in Malaysia to determine their level of material deprivation. Results indicate a low level of material deprivation among poor Malaysian children. The authors include some recommendations to improve on the well-being of children in Malaysia.

With the hypothesis that the quality and quantity of placement of children with their kin depend on social workers, managers, and some organizational factors, Rasmussen and Jæger ( 2021 ) present a case study of social workers and their field practices related to kinship care in Denmark. Their paper, “The Emotional and Other Barriers to Kinship Care in Denmark: A case study in two Danish municipalities” contains analysis of the findings of their study. Through a mixed method approach of analyzing documents, interviews, observations, and dialogue meetings, data on placement into kinship care in two municipalities in Denmark were gathered. Among all the cases selected for the study, they reported a reasonable level of satisfaction among all parties involved. However, the authors indicate a hesitation among social workers to enter emotionally-charged familial situations which affects their decisions on kinship placement. The paper also points to the non-involvement of families in a systematic manner in placement decisions as another factor that affects placement decisions.

Grządzielewska ( 2021 ) from Poland, reviews how machine-learning can be applied as a tool to predict burnout among social work employees in the paper, “Using Machine Learning in Burnout Prediction: A Survey”. The ability to analyze and interpret large amount of data makes the tools of machine learning very useful. The paper attempts to compare traditional and newer methods of predictive modeling and discusses how different variables affect the choice of appropriate methodologies. It is discussed in this paper how machine-learning algorithms can be incorporated into a burnout monitoring system to create new models of burnout, identify the potential for burnout among new recruits and existing employees, and design appropriate interventions. The author recommends further attention by social work researchers in the study of burnout.

We acknowledge the contributions of the various authors to making this special issue possible by sharing their perspectives on child welfare service delivery.

Abu Bakar Ah, S. H., Rezaul Islam, M., Sulaiman, S., et al. (2021). Material deprivation status of Malaysian children from low-income families. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-020-00732-x .

Article Google Scholar

Asscher, J. J., Van der Put, C. E., & Stams, G. J. (2015). Gender differences in the impact of abuse and neglect victimization on adolescent offending behavior. Journal of Family Violence, 30, 215–225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-014-9668-4 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bamford, T. (2015). A contemporary history of social work: Learning from the past . Bristol: Policy Press.

Book Google Scholar

Cahalane, H. (2013). Contemporary issues in child welfare practice . New York, NY: Springer.

Cooper, A. (2005). Surface and depth in the Victoria Climbie Inquiry report. Child and Family Social Work, 10 (1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2005.00350.x .

Filippelli, J., Fallon, B., Lwin, K., & Gantous, A. (2021). Infants and toddlers investigated by the child welfare system: Exploring the decision to provide ongoing child welfare services. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 11, 1–15.

Google Scholar

Fong, K. (2017). Child welfare involvement and contexts of poverty: The role of parental adversities, social networks, and social services. Children and Youth Services Review, 72, 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.10.011 .

Frimpong-Manso, K. (2021). Family support services in the context of child care reform: Perspectives of Ghanaian social workers. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-020-00729-6 .

Grządzielewska, M. (2021). Using machine learning in burnout prediction: A survey. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-020-00733-w .

Kanios, A. (2021). Beliefs of secondary school youth and higher education students about elderly persons: A comparative survey. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-020-00727-8 .

Lalayants, M. (2008). Interagency collaboration approach to service delivery in child abuse and neglect: perceptions of professionals. International Journal of Interdisciplinary Social Sciences, 3, 225–336.

Mackrill, T., & Svendsen, I. L. (2021). Implementing routine outcome monitoring in statutory children’s services. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-020-00734-9 .

McNutt, J. (2013). Social work practice: History and evolution. Encyclopedia of Social Work . Retrieved January 11, 2021, from https://oxfordre.com/socialwork/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199975839.001.0001/acrefore-9780199975839-e-620 .

Mendes, P. (2005). The history of social work in Australia: A critical literature review. Australian Social Work, 58 (2), 121–131. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0748.2005.00197.x .

Odrowąż-Coates, A., & Kostrzewska, D. (2021). A retrospective on teenage pregnancy in Poland: Focusing on empowerment and support variables to challenge stereotyping in the context of social work. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-020-00735 .

Rasmussen, B. M., & Jæger, S. (2021). The emotional and other barriers to kinship care in Denmark: A case study in two Danish municipalities. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal.

Reisch, M., & Jani, J. S. (2012). The new politics of social work practice: Understanding context to promote change. British Journal of Social Work, 42 (6), 1132–1150. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcs072 .

Stuart, P. (2019). Social work profession: History. Encyclopedia of Social Work . Retrieved January 11, 2021, from https://oxfordre.com/socialwork/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199975839.001.0001/acrefore-9780199975839-e-623 .

van Dam, L., Heijmans, L., & Stams, G. J. (2021). Youth initiated mentoring in social work: Sustainable solution for youth with complex needs? Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-020-00730-z .

Wellman, M. M. (1993). Child sexual abuse and gender differences: Attitudes and prevalence. Child Abuse & Neglect, 17 (4), 539–547. https://doi.org/10.1016/0145-2134(93)90028-4 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Centre for Family Research, Nicolaus Copernicus University, ul. Lwowska 1, 87-100, Toruń, Poland

Jarosław Przeperski & Samuel A. Owusu

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jarosław Przeperski .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Przeperski, J., Owusu, S.A. Children and the Child Welfare System: Problems, Interventions, and Lessons from Around the World. Child Adolesc Soc Work J 38 , 127–130 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-021-00740-5

Download citation

Accepted : 16 January 2021

Published : 30 January 2021

Issue Date : April 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-021-00740-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Child welfare

- Child protection

- Social work intervention

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Our Journey

Thanks for signing up.

Evaluating Child Labor Programs: Uncovering How Local Norms Impact Field-Level Relationships Between Farmers, Workers and Children

This is a case study of how Philip Morris International (PMI), used participatory evaluation tools to gather information in order to address the “root causes of the most prevalent and persistent issues that keep surfacing” – specifically child labor in their agricultural supply chain.

Using participatory evaluation to address the root causes of an issue

This case study is part of a collection developed under the Quality of Relationships stream of Shift’s Valuing Respect Project . It explores how Philip Morris International (PMI) , a global tobacco company, used participatory evaluation tools to gather information in order to address the “root causes of the most prevalent and persistent issues that keep surfacing” – specifically child labor in their agricultural supply chain.

December 2020 |

Assessing whether behavior change training can improve relationships between supervisors and workers.

Over the years, PMI has been gathering data through regular assessments and farm visits, which help the company to monitor the implementation of its labor standards, including zero child labor. However, it is its latest strategy, Step Change , that has provided complementary information about local awareness challenges, customs and societal attitudes that normalized children working on tobacco-growing farms. In driving this change, PMI has set itself an ambitious target to eliminate child labor from its leaf supply chain by 2025. Addressing incidences of child labor is important due to the hazardous nature of the agricultural work, which can pose increased health and safety risk to children. This case study describes how a combination of participatory methods allowed local and affected people to express in their own terms any local realities that run counter to the company’s efforts to reduce the use of child labor on farms.

Specifically, the evaluation uncovered that:

- workers are more accepting of children working on farms than farmers;

- child labor is seen as part of a widespread societal norm of communal work; and

- strong cultural beliefs ingrained in the society including of some local leaders, educators and community representatives weakening the company’s messaging about child labor.

“ We asked ourselves: ‘Why aren’t we seeing positive change?’ That is when we decided to take a deep dive, speak to the farmers and workers directly to uncover root causes which were preventing us from achieving desired outcomes.” “ JOANNE LE PATOUREL, MANAGER SOCIAL SUSTAINABILITY LEAF, PMI

QUALITY OF RELATIONSHIPS SERIES

- Key Messages

- Other Resources

ABOUT THE VALUING RESPECT PROJECT

- Why We need change

Take Action

This resource was published by shift project on february 07, 2021, related work to evaluating child labor programs: uncovering how local norms impact field-level relationships between farmers, workers and children.

August 2021 |

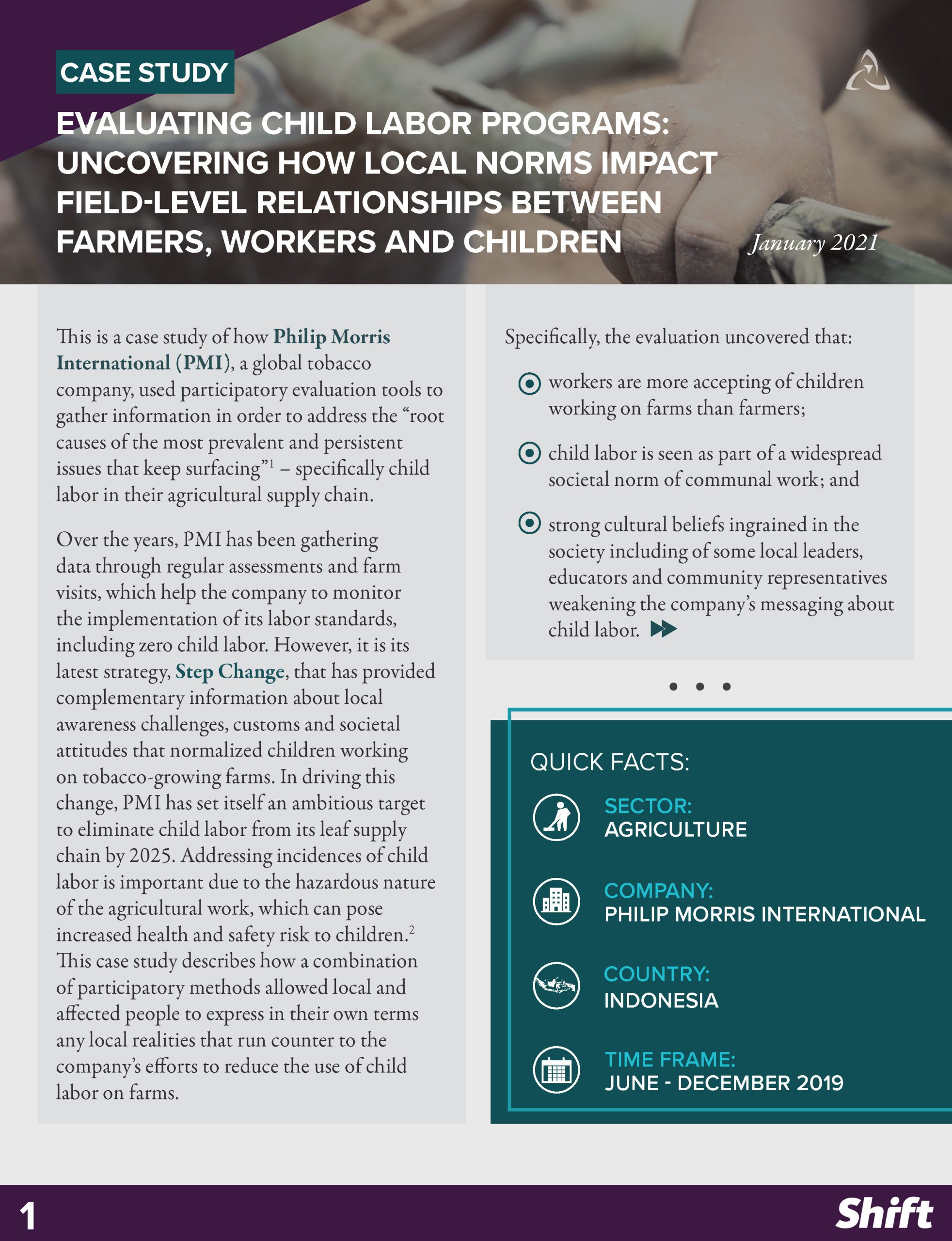

Red flag 24. aggressive tax-minimization strategies.

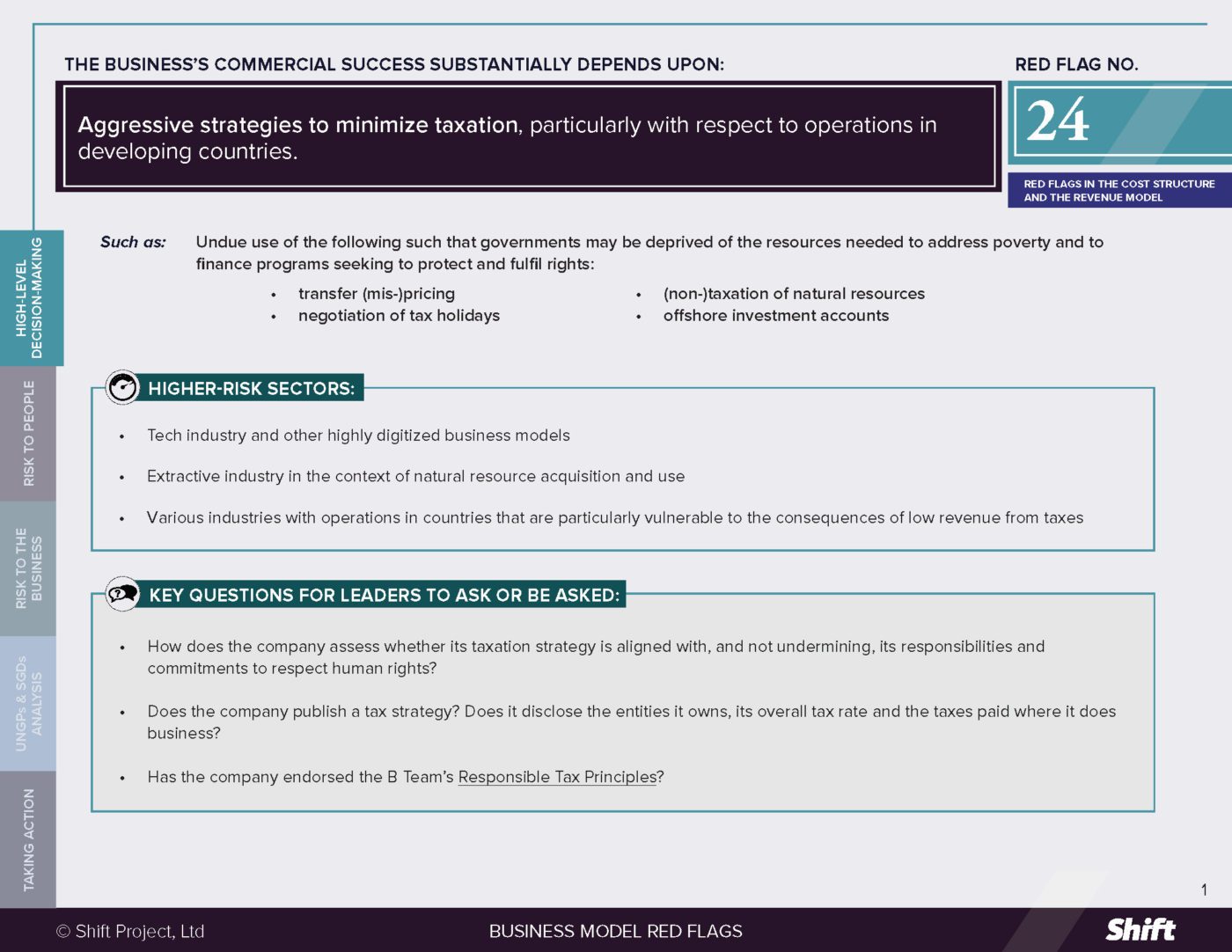

Red Flag 23. Markets where regulations fall below human rights standards

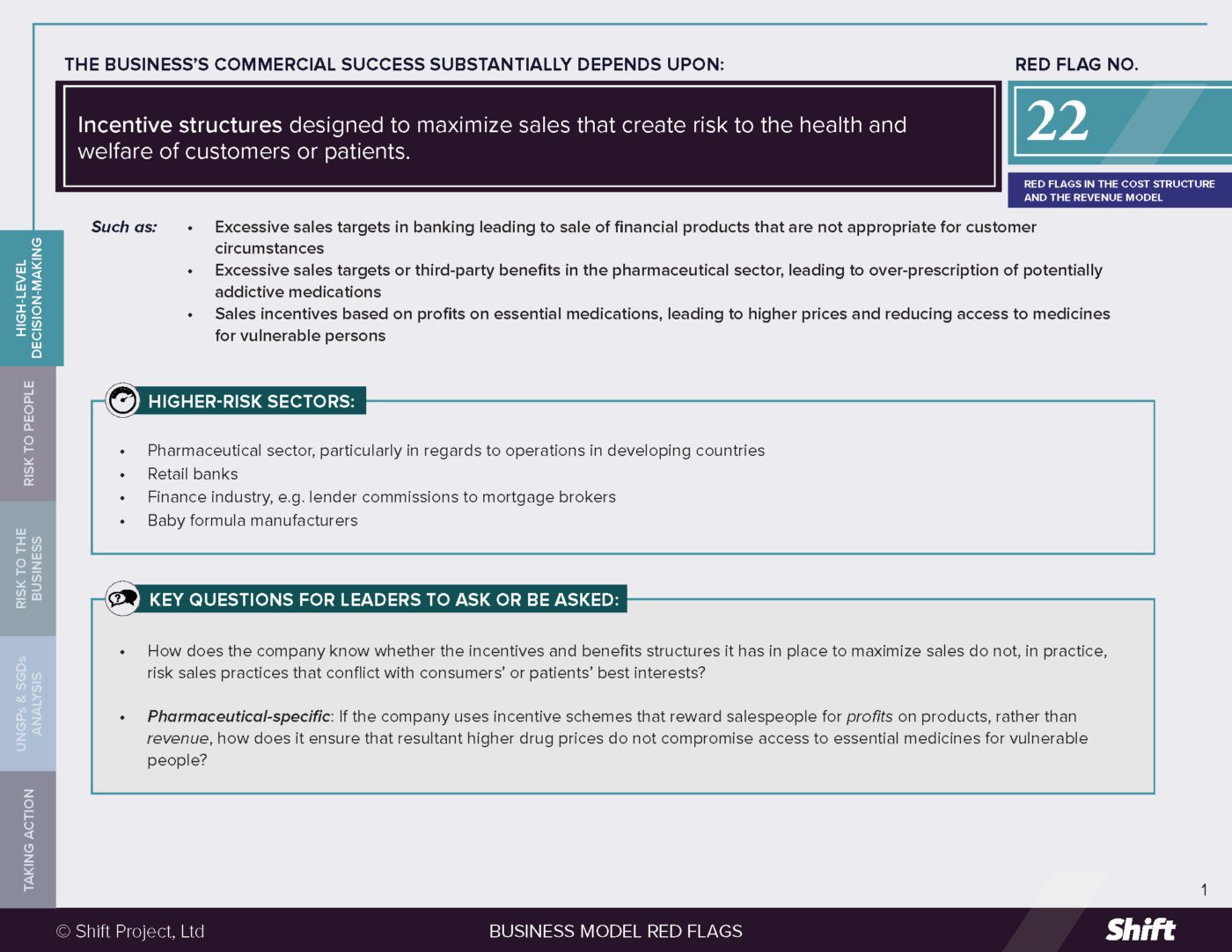

Red Flag 22. Sales-maximizing incentives that put consumers at risk

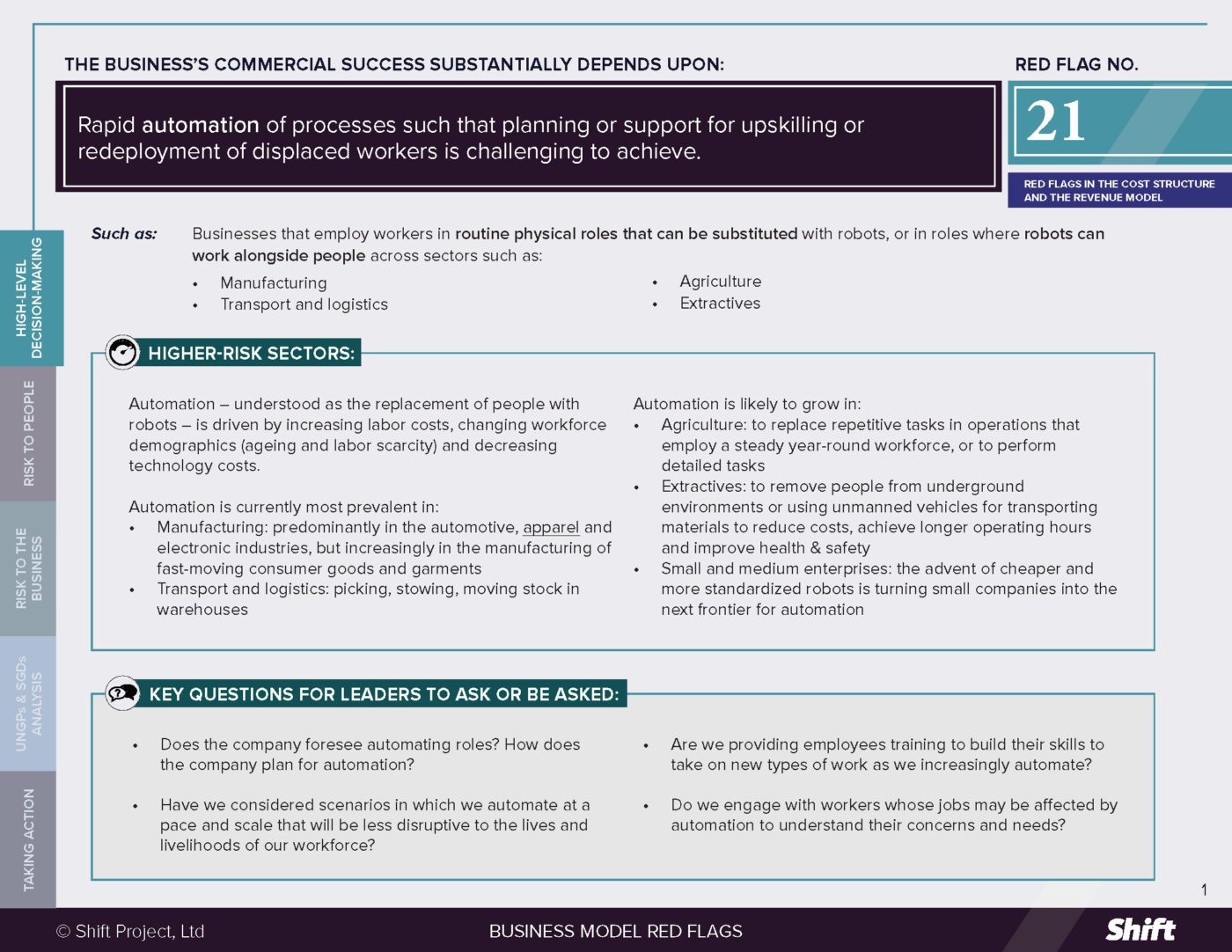

Red Flag 21. Automation at speed or scale that leaves workers little chance to adapt

Like what you’re seeing, get notified whenever shift releases a new resource, viewpoint, or insight..

Privacy Overview

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Health Promot Perspect

- v.12(4); 2022

Exploring the health of child protection workers: A call to action

Javier f. boyas.

1 Troy University, School of Social Work and Human Services, 112A Wright Hall, Troy, AL, 36082, USA

Debra Moore

Maritza y. duran.

2 University of Georgia, School of Social Work, 279 Williams St., Athens, GA, 30602, USA

Jacqueline Fuentes

Jana woodiwiss, antonella cirino.

Background: This exploratory study determined if a relationship exists between secondary traumatic stress (STS) related to health status, health outcomes, and health practices among child protection workers in a Southern state.

Methods: This study used a cross-sectional survey research design that included a non-probability sample of child protection workers (N=196). Data were collected face-to-face and online between April 2018 and November 2019 from multiple county agencies. A self-administered questionnaire was completed focused on various health behaviors, outcomes, and workplace perceptions.

Results: Results of the zero-order correlations suggest that higher levels of STS were significantly associated with not having visited a doctor for a routine checkup ( r =-0.17, P =0.04), more trips to see a doctor ( r =0.16, P =0.01), and increased number of visits to emergency room (ER) ( r =0.20, P =0.01). Lower levels of STS were associated with better self-rated health (SRH) ( r =-0.32, P ≤0.001), higher perceptions of health promotion at work ( r =-0.29, P ≤0.001), frequent exercise ( r =-0.21, P =0.01), and by avoiding salt ( r =-0.20, P ≤0.031). T-test results suggest that workers who did not have children (µ=45.85, SD=14.02, P =0.01) and non-Hispanic white workers (µ=51.79, SD=11.62, P ≤0.001) reported significantly higher STS levels than workers who had children (µ=39.73, SD=14.58) and self-identified as Black (µ=39.01, SD=14.38).

Conclusion: Findings show that increased interpersonal trauma was linked to unhealthy eating, general physical health problems, and health care utilization. If not addressed, both STS and poor health and health outcomes can have unfavorable employee outcomes, such as poor service delivery.

Introduction

Child protection is one of the more challenging and taxing human service occupations. The nature and organization of the work make child protection inherently strenuous, such as high work demands, low salaries, excessive caseloads, risky and unpredictable case situations, changing policies and standards, on-call duties, understaffed work environments, persistent emergencies, and arduous work schedules. 1 - 4 Child protection workers often face the apprehension of making abrupt decisions on complicated cases, sometimes with little to no background information. Such fast-paced decision-making does not always end in selecting the safest option, which has resulted in continuous public and media scrutiny. 5 It is clear, though, that child protection workers’ decisions are vital, given they are the first line of defense when there is suspicion of child abuse or neglect and effective interventions when cases of abuse or neglect are indicated. Additionally, listening to children talk about traumatic experiences while trying to work in a demanding, challenging, and commonly “insensitive” child welfare structure can potentially put a child protection worker at heightened risk of developing emotional and psychological problems. 6 - 10 Thus, for child protection workers to provide quality services to vulnerable populations, they must be mentally, physically, and emotionally prepared.

Given the magnitude of what is at stake and the number of job-related stressors, it is not surprising that many child protection workers suffer from mental health problems. Such suffering has often resulted in the genesis of adverse occupational stress reactions, such as job stress, burnout, and vicarious trauma. 6 - 10 One of the concerning occupational hazards faced by child protection work relates to the increased susceptibility to experiencing vicarious trauma, often recognized as secondary traumatic stress (STS). It has been estimated that as many as 70% of social workers experience STS. 11 That is because of the multiple times child protection workers are exposed to indirect trauma through a client’s narrative and distressing description of a traumatic event, such as hearing accounts of acts of cruelty, medical neglect, emotional, physical, sexual, and psychological abuse. 12 , 13 They also hear and read disturbing content discussed in case reviews and case recordings. 14 Since so many of their clients are survivors of trauma, child protection workers provide empathy for their clients by providing ongoing listening, supporting, and providing various levels of continuing care, which can leave them vulnerable to absorbing the anguish their clients experience. 15 Not surprisingly, child protection workers too are likely to show stress symptoms of primary trauma. 16 , 17 STS is thus viewed as a psychological reaction to a stressor encountered in the workplace associated with the many traumatic accounts shared by trauma survivors. 18 It is well established that STS can manifest on three levels: physical, behavioral, and psychological/emotional. 19

Although researchers have documented the psychosocial stress reactions associated with child protection, such as STS, very few studies have explored whether child protection workers’ levels of STS are associated with health status, health practices, and health outcomes. Existing research highlights the relationship between interpersonal trauma exposure and adverse physical health outcomes. 20 , 21 Furthermore, several studies sampling vulnerable occupational groups revealed that occupational stress can manifest and result in psychosomatic symptoms. 22 - 26

This relationship has been explained by asserting that trauma activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the sympathetic nervous systems, which prompts an overreaction in the immune system. 27 , 28 This physiological response is attributed to increased ill health and a debilitated immune system. 29

We maintain that investigating the global health of this occupational group is highly relevant because, historically, child protection workers hardly ever benefit from organizational health and well-being training. Very few organizations have invested in promoting health and well-being among their workforce. While some child protection organizations have started to introduce programming to address mental health concerns, the same cannot be said about physical health, despite the growing number of studies that underscore the health concerns raised by child protection workers. 30 - 32 Current research suggests that child protection workers develop unhealthy behaviors due to the stress and demands of child protection practice, which include unhealthy eating, substance abuse, self-neglect, and lack of exercise. 30 , 33 Thus, child protection workers’ health behaviors and health status should be investigated, given the work conditions they experience. Health is not only a key indicator of social wellness, but it is also essential to the work performance of child protection workers. 34 Ignoring child protection workers’ health could put the entire child welfare system at risk. 15 , 35 There is very little information in the literature related to how much health is discussed within child welfare organizations or discussion of the nutritional eating habits of child protection workers. Additionally, although many studies suggest that many child protection workers suffer from STS, 36 , 37 few studies have explored whether a correlation exists with health status, health practices, and health outcomes among this vulnerable occupational group. This study’s first aim was to identify child protection workers’ health practices and health status in a Southern state. The second aim was to determine if a significant correlation exists between STS, health behaviors, and health outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Research design and sampling.

This study used a cross-sectional, retrospective research design. A non-probability sample of child protection workers was recruited to participate in this study using a combination of convenience and snowball sampling techniques. The study eligibility criteria were: (1) be at least 18 years of age, (2) be employed in a child protection public agency in a specific Southern state and (3) have no cognitive limitations. Participants were excluded if they worked for a private child protection agency or were public child protection in other neighboring states. No potential participant was left out due to exclusion criteria.

Participants were recruited via Facebook, word of mouth, and at trainings targeting child protection workers. Data were collected face-to-face and online from April 2018 through October 2019 from various county agencies across one state. A self-administered questionnaire took approximately 30 minutes to complete. In all, 40 persons opted to complete the survey online, whereas the other 158 participants completed their surveys face-to-face. No significant differences in health and health outcomes were identified between respondents who completed the survey online compared to those who completed the survey in person. Pilot testing with 15 possible participants was conducted to further maximize the face validity of the questionnaire. Their responses were not included in the current analysis. As a result of feedback gained from the pilot testing, the final instrument was abbreviated to reduce the possibility of the participants experiencing mental fatigue. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Participants were not given a research honorarium. The Institutional Review Board at the University of Mississippi approved the protocols (protocol number: 18x-288)used in the present study to ensure minimal risk to participants.

Instrumentation

The STS symptoms scale 36 is a self-report questionnaire consisting of 17 items. Responses are based on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = never to 5 = very often). The STS includes three subscales: intrusion (5 items), avoidance (7 items) and arousal (5 items). Items were summed to create a total score, with higher scores indicating a higher level of STS. A total score of 38 or higher indicates STS. 36 The STS scale had a high internal consistency in the present study (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.89).

Self-rated health (SRH) continues to be widely used in health surveys because it is considered a robust global measure of general health status in epidemiological studies and an independent predictor of morbidity and mortality. 38 , 39 SRH was a single item that asked respondents to answer the question, “How would you describe your overall state of health these days?” SRH was measured as a five-category ordinal variable: poor = 0 to excellent = 4.

Several measures were included to determine child welfare workers’ health status, health practices, and health outcomes. Chronic health conditions were an eight-item measurement in which workers were asked to report the chronic conditions they were experiencing. Workers were asked if they had been diagnosed with the following conditions: diabetes, heart disease, obesity, asthma, hypertension, cancer, stroke, and liver disease. Each question was a dichotomous variable, indicating either presence (= 1), or absence (= 0) of the diagnosis in question.

Exercise activity was a single item measure that asked participants how often they managed to get the recommended amount of exercise: 1 = never to 3 = three times a week. Body mass index was calculated by height and weight of respondents. Smoking was a five-item measure that captured participants’ smoking status, how many cigarettes they smoked daily, weekly, and monthly, and if they began smoking as a result of their job. Smoking status was captured as a dichotomized measure: no = 0, yes = 1.

Nutritional eating was an eight-item measure that asked participants how often they engaged in healthy eating by eating fruit, eating vegetables, eating healthy options, avoiding salt, eating bran, avoiding fried food, avoiding desserts, and avoiding sugary drinks. Each nutritional eating question was an ordinal variable that was measured as Never/rarely = 1, A few times per week = 2, Once a day/every meal = 3.

The following individual and demographic data were collected: race/ethnicity, age, education level, job titles, marital status, and children. Race/ethnicity was a single item that asked participants to state with which ethnic group they identify. The original options included Caucasian, African American/Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic/Latino, Asian American/Asian, Native American/Alaskan Native, Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, or not listed. However, since the sample was mostly homogenous, this variable was dichotomized: 0 = non-Hispanic White, 1 = African American/Black. Age was a continuous measure. Educational degree was a nominal measure: Bachelor = 1, Bachelor’s in Social Work = 2, Master’s in Social Work = 3, Master’s in Psychology = 4, Ph.D. = 5, Psy D. = 6, JD = 7, Other = 8. Licensure was dichotomized: No = 0, Yes = 1. Furthermore, job titles were nominal measures: Manager/ Supervisor = 1, Frontline worker = 2, Staff = 3, Legal staff = 4. Marital status: single = 1, married = 2, separated = 3, divorced = 4, widowed = 5. Having children were captured as a dichotomized measure: No = 0, Yes = 1.

Team health promotion was measured by the Team Health Climate instrument developed by Sonnentag and Pundt. 40 Three Likert-scale items were used to assess if workers were asked if the topic of health was included in their work meetings, if it was expected within their workplace that they take care of their health, and if there were any exchanges in ideas about healthy living. Child welfare workers responded using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). All 3 items were aggregated to create the scale, with higher scores representing better perceptions of team health promotion. Previous research of the team health climate scales showed acceptable levels of internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.71). 41 In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.86.

Health care utilization was a five-item measurement. Workers were first asked if they had one person they thought of as their personal doctor or health care provider (1 = Yes, only one, 2 = More than one, and 3 = No, I do not have a personal doctor or health care provider). They were then asked about how long it had been since they last visited a doctor for a routine checkup; this was a Likert scale measure that ranged from 1 = Within the past year to 6 = Never had a routine checkup. The health care utilization measures were three single items previously used in the National Health Interview Survey. 42 Each item asked participants to report how many times they had visited a health clinic, doctor, and emergency room (ER) in the past 12 months.

Data analysis

Univariate statistics were used to discern the study sample in terms of sociodemographic characteristics. Bivariate analyses included zero-order correlations to determine if multicollinearity was an issue and identify the strength between STS and independent variables. T -tests were also used to identify group mean differences by sex and race/ethnicity. Statistical significance was measured at the 95% confidence interval level ( P ≤ 0.05). All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Descriptive sample information

The majority of the child protection workers in the sample were Black/African American ( n = 152; 77%), followed by non-Hispanic White/Caucasian ( n = 44; 22%). The sample participants identified primarily as female ( n = 197, 97.5%). The median age of the respondents was 36.86 (SD = 10.34) years old. In terms of marital status, most of the respondents indicated being single ( n = 93; 46%), followed by those who were married ( n = 84; 42%). Many respondents reported having children 73.8% ( n = 149). In terms of job tenure, respondents reported a mean average of 68.73 months, or 5.72 years of working for the child protection agency. Most respondents were frontline workers ( n = 136; 67%), whereas the remaining were in managerial and supervisory positions ( n = 42; 20%). Most respondents held a Bachelor’s in Social Work (BSW) ( n = 123; 61%), while 50 (25%) reported possessing an master of social work (MSW). Only 33.7% of respondents ( n = 68) were Licensed Social Workers. Respondents indicated that 63.4% ( n = 128) worked in a rural community, followed by 22.3% ( n = 45) of workers who worked in a semi-rural community.

Health status and health behaviors

In terms of health status, 62% of respondents indicated having either poor or fair health. Respondents reported having been diagnosed with the following chronic health conditions: diabetes 18% ( n = 37), heart disease 4.5% ( n = 9), obesity 28.7% ( n = 19), hypertension 28.7% ( n = 58), asthma 6.4% ( n = 13), cancer 1.5 % ( n = 3), stroke 1% ( n = 2) and liver disease.5% ( n = 1). Among the respondents, 29% reported having at least one chronic condition, 13% reported having two conditions, while 8% reported having 3 chronic conditions. Most of the respondents did not smoke cigarettes ( n = 93%). Seven respondents stated that they started smoking as a result of working at the agency. The mean average body mass index (BMI) of survey respondents was 31.64 (SD = 8.34).

Participants were asked if they managed to get the recommended amount of exercise per week which is at least 30 minutes three times per week. The majority of respondents (55.4%; n = 112) indicated they rarely/occasionally exercised the recommended amount, while 33.7% ( n = 68), indicated that they never exercised the recommended amount. Only 10.4% ( n = 21) of the respondents indicated they exercised the sufficient amount/got sufficient physical activity in their work.

Nutritional eating

In terms of healthy eating, 22.8% ( n = 46) of the participants indicated that they never/rarely engaged in eating fruits, while 68.4% ( n = 128) indicated that they engaged in eating fruits a few times per week. Only 12.4% ( n = 25) indicated that that they engaged in eating fruits with every meal. Regarding engaging in eating vegetables, participants indicated 22% ( n = 10.9) never/rarely, while 56.9% ( n = 115) indicated a few times per week, and 29.7% ( n = 60) indicated eating vegetables once a day/every meal. In terms of avoiding salt, 53.5% ( n = 108) of participants indicated never/rarely, 31.7% ( n = 64) indicated a few times per week, 12.4% ( n = 25) indicated avoiding salt once a day/every meal. Participants were asked how often they ate bran: 57.9% ( n = 117) indicated never/rarely; 33.7% ( n = 68) indicated a few times per week; 3% ( n = 6) indicated once a day/every meal. Participants were also asked how often they avoided fried food, and 39.1% ( n = 79) reported never/rarely avoiding fried food; 46% ( n = 93) avoided fried food a few times a week; and 11.9% ( n = 24) avoided fried food once a day/every meal. Furthermore, 42.6% of participants never/rarely avoided sugary drinks; 39.6% ( n = 86) avoided sugar drinks a few times per week and 15.8% ( n = 32) avoided sugary drinks once a day/every meal.

Health-seeking behaviors

In terms of having a personal care provider, 61% of the respondents reported having one person they considered their personal doctor or health care provider, whereas 14% did not have one person they considered their personal care provider. The majority of respondents, 75%, reported visiting the doctor for a routine doctor visit that did not include an exam for a specific injury, illness, or condition in the past year, while another 13% visited the doctor for a routine visit within the past two years. In terms of health care utilization, respondents were asked how many times they visited a health clinic, a doctor’s office, and the ER. Twenty percent of respondents did not visit the doctor for a routine doctor visit. On average, respondents average 3.39 (SD = 3.85) visits to a doctor’s office, 2.95 (SD = 3.37) visits to a health clinic, and.55 visits to the ER in the past 12 months. Roughly 33% of the respondents reported needing to go to see a doctor but did not do so because of cost.

Health promotion in the workplace

Participants were surveyed about how much health is discussed within their team meetings and other team events. Roughly 46% either strongly disagreed or disagreed that the topic of health is discussed within their team. Moreover, 41% strongly disagreed or disagreed that they exchanged ideas about healthy living within their team. However, 54% strongly agreed or agreed that it is expected that they take care of their health.

Bivariate results

Results of the zero-order correlation suggest that STS is significantly associated with healthy eating by avoiding salt, frequency of exercise, team health climate, frequency of routine check, number of visits to the doctor, number of visits to ER, and SRH. Results of the t test suggest that having children and race were significantly associated with STS. In terms of health status, respondents who reported poorer health also reported higher levels of STS ( r = -0.32, P ≤ 0.001). In terms of health behaviors, respondents that did not exercise 30 minutes 3 times weekly reported significantly higher levels of STS ( r = -0.21, P ≤ 0.01). Respondents who reported not avoiding eating salt also reported higher levels of STS ( r = -0.20, P ≤ 0.05). In terms of the workplace, respondents who perceived higher perception of health being promoted amongst their team also reported lower levels of STS ( r = -0.29, P ≤ 0.001). Turning to healthcare utilization, respondents who made more trips to see a doctor ( r = 0.16, P ≤ 0.05) and the ER ( r = 0.20, P = 0.01) also reported higher levels of STS. However, respondents who have not visited a doctor for a routine checkup in a while reported significantly higher levels of STS ( r = 0.17, P = < 0.05). Demographically, t test results suggest that workers who had children (µ = 39.73, SD = 14.58) reported significantly lower levels of STS than workers without children (µ = 45.85, SD = 14.02). African American child protection workers (µ = 39.01, SD = 14.38) reported significantly lower levels of STS compared to non-Hispanic White workers (µ = 51.79, SD = 11.62).

Child protection workers work in highly stressful work environments and are regularly exposed to emotional duress indirectly, which may result in the genesis of interpersonal trauma. The present study sought to explore how STS was associated with multiple health outcomes among child protection workers in a southern state. Among a sample of child protection workers, 57.7% of respondents in the present study reported STS scores of 38 or more. This finding is concerning, given that interpersonal trauma has been linked to somatic symptoms and general physical health problems. 43 If not addressed, STS and poor health can have unfavorable employee outcomes, such as poor service delivery. Thus, if child welfare outcomes are going to improve, improving child protection workers’ health and mental health will be critical.

Health status was significantly associated with STS. In the present study, results indicate that STS was significantly associated with SRH. In fact, SRH shared the strongest relationship with STS. Consistent with existing studies, poorer health perceptions were significantly associated with increased levels of STS among child protection workers. 21 , 32 , 44 This finding may be related to the correlation between health outcomes and the clustering of avoidance and hyperarousal symptoms that underly STS, resulting in a potentially cumulative adverse impact on health. 32 , 45 , 46 One study suggests that child protection workers’ stress contributes to unhealthy eating habits, disturbed sleep, and substance use and poor health, such as high blood pressure, weight gain, and fatigue. 30 Other studies suggest that secondary stress among social workers was associated with sleep disturbance, sexual difficulties, poor eating habits, and elevated blood pressure. 26

Health practices were found to be correlated with STS. The observed relationship between STS and lack of exercise among child protection workers is indicative of literature illustrating the impact of mental health distress on disengaging from physical activity. 30 , 47 In one study, child protection workers noted having “no energy” or “being too tired” to engage in physical activity after work, highlighting the emotional exhaustion of STS leading to bodily fatigue. 15 This finding is consistent among first responders who also report lower levels of physical activity when having higher levels of STS. 48 Moreover, this finding affirms the consequences of trauma on the physical health of child protection workers.

The present study revealed that respondents who reported not avoiding eating salt also reported higher levels of STS. There currently needs to be more research examining how limiting salt can curtail STS. While it has been noted that psychological dysregulations ensue as a result of normal homeostatic functioning being shifted towards abnormal ranges due to prolonged secretion of stress hormones, 49 the connections between behaviors associated with these dysregulations as it relates to STS and salt intake have not been established. Furthermore, psychosocial stimulation associated defense responses (stress) have been shown to induce an increase in salt appetite. 50 - 52 One suggestion to this occurrence may be that after prolonged salt intake to ameliorate stress activation, individuals may lean on salt to manage stressful situations and become less able to deal with consistent stress, such as work-related stress or STS. More research is needed that elucidates the workings of this relationship.

Limited literature also exists regarding the association between child protection workers and their participation in routine check-ups and ER visits and doctor visits. Some literature suggests child protection workers miss appointments or come to work sick due to time constraints with their work schedule and fear falling behind on their existing workload. 30 , 33 One study suggests child welfare workers directly referenced not feeling they had time to attend routine check-ups due to overwhelming workloads and described preventative care becoming an added stressor. 30

Turning to sociodemographics, two were significantly associated with STS. Findings suggest a significant relationship exists between having children and lower STS scores. This may be the case because having loving and supportive relationships with friends and family may increase child protection workers’ capacity to manage different types of stress. 53 For child protection workers without children, it is reasonable to assume that the absence of psychosocial resources, such as children, does not allow these workers to find the fortification and inner strength to realize mental equilibrium or emotional permanence, which can increase the onset of distress. 54 Essentially, the missing support from personal resources, such as those with children, can lead to poorer individual coping. 55 , 56 However, our results contradict the existing literature, which implies that STS levels are higher among child protection workers who reported having children. 31 , 57 One of STS’s notable consequences is strain and withdrawal from personal relationships as a defense mechanism against traumatic experiences shared by clients. 31 Several participants in James’study 31 reported experiencing STS had impacted their relationships because of feeling beleaguered by constant distractions and lower moods. Respondents noted their stress levels increased because of not having enough time with family and friends and missing their children’s school events. Still, more research is needed that elucidates possible explanations as to why child protection workers without children suffer from higher levels of STS.

In this study, race mattered. The racial identity of child protection workers was found to predict increased levels of STS, specifically among White child protection workers. While there is not literature to help explain this finding due to mostly white samples in child welfare studies, 58 several interpretations can be advanced. This finding could relate to the context of the workers, which is the southern state itself, where data were collected. Historically, and even today, this state’s quest for full integration continues to be a struggle. This is a state with a deep history of enslavement, sharecropping, racial exclusion separation, hate group participation, and aggressive anti-Black activism. This history allowed many Whites to experience life in a cultural vacuum where they were surrounded by white peers. 59 Understanding this backdrop, it may be that what White child protection workers in this study heard traumatic narratives that they have never heard of or experienced directly. It could be argued that the life experiences by Whites in this Southern state are radically different from the many families of color, and rural populations who receive child protection services. According to constructivist self-development theory, a person constructs their realities based on self-perceptions and schemas, influenced by their lived experiences, that stem from interpersonal, intrapsychic, familial, cultural and social experiences. 19 , 60 Black child protection workers in this Southern state may have experienced lower incidences of vicarious trauma because they have been already exposed to accounts of traumatic experiences of child abuse and neglect that fit all too well with their reality. Because of their lived experience, Black child protection workers had already confronted the damage generated by intergenerational trauma, which may have lessened the pain of hearing accounts of trauma among their clients. The traumatic narratives heard by Black child protection workers may have altered their cognitions and worldview in ways that did not materialize for non-Hispanic White child protection workers, who may have never been exposed to the trauma they heard from clients.

It can also be hypothesized that the deflated account of STS among Black child welfare workers can be attributed to the Black Superwoman Schema (the overwhelming majority of Black respondents were women), which posits that Black women are less likely to report STS due to their socialization, which is linked to racial and gendered schema that includes displaying strength to overcome racial adversity. 61 , 62 Watson and Hunter 63 expand on how this multidimensional construct is characterized as an “obligation to manifest strength, emotional inhibition, resistance to utilize mental health self-care resources, rejection of dependence on others, determination to succeed, and caretaking” 63 (p. 445). Qualitative findings suggest Black women, particularly professionals, resist showing vulnerability because they do not want to give their counterparts a sense that they could not do the work, even when working with limited resources, 62 as is often the case in child protection work.

Team health climate was also examined in this study, which revealed thatchild protection workers reported lower levels of STS when they perceived working in an environment where team health was being promoted. To the best knowledge of the authors, no other study has examined if a relationship exists between STS and team health climate. One study found that team health climate was generally associated with positive health and mental health. 41 The results are consistent with broader research suggesting that health climate is a milieu source that enables health-related outcomes among workers. 41 , 64 This finding underscores the importance that an organization’s climate can have on serving as a social cue to trigger desired and rewarded health behaviors that safeguard child protection workers from ill health. 64

Implications

Child welfare workers experience elevated rates, such as 80% mild, 47% moderate, and 22% full STS severity levels. 65 Due to current reports of STS rates among child protection workers, exploration of how STS impacts the health of child protection workers, as evidenced by the proven association between STS and ER visits, doctor visits, and routine checks, may assist with developing better support systems for this strained workforce that is a crucial base in supporting families and children in need. Child welfare organizations are primed to become distal antecedents for employee health and well-being. To mitigate the genesis of STS, organizations can be intentional about emphasizing concern, care, and consideration about favorable employee health- and mental health-related outcomes. This can be accomplished through using health promotion advocacy to encourage self-care practices among its employees by “maintaining a healthy diet, physical exercise, balancing work and play, rest, spiritual replenishment, and building social networks”. 31 The National Association of Social Workers (NASW) 66 supports organizational policies that promote self-care, including a healthy diet, adequate sleep, physical activity, health care, and vacations to prevent STS. 67 This is important given that empirical evidence exists that links self-care practices with more favorable perceptions of health among child protection workers. 68

Given the number of poor health habits (e.g., poor nutritional eating habits, low exercise activity levels) reported by child protection workers in this study, child welfare organizations must begin to consider the health status of their workforce. Most of the workers in the present study reported poor or fair health, almost 30% reported suffering from at least one chronic condition, many had very high BMI counts, and over 60% did not have someone they considered their personal doctor or health care provider. Thus, it would be prudent for organizations to take on the role and responsibility of promoting the well-being of their employees. 69 It has been argued that a positive organizational climate is one that provides learning opportunities and rewards. 64 Child welfare administrators should consider encouraging teams within the agency to discuss health matters and provide them with health and mental-related information and practical support, 41 such as trauma-specific workshops or contract or partner with community clinics to host on-site monthly health checkups for the employees. This partnership is germane for child protection staff, given that many respondents stated they could not take time away from work to tend to their medical needs.

To mitigate the negative impacts of STS, child welfare agency administrative responses should integrate trauma-informed child welfare practices into their organizational culture. 68 Trauma-informed child welfare practices by staff concede how traumatic events could influence children, families, and child protection professionals who serve them. Still, such an approach should also acknowledge how the workers might suffer from the various traumatic narratives they have encountered while working in child protection. 70 For example, normalizing the experience of secondary trauma among workers is essential in considering trauma as an underlying explanation for behavioral and emotional distress. 70 Such a perspective may change the deficit approach child protection workers are met with by their colleagues. The conversation may shift from asking, “What’s wrong with you?” to “What happened to you?” 70 (p. 6).

Another implication of this study’s findings is the potential that child protection workers’ consumption of salt to manage stress may cause increased tolerance, rendering this coping mechanism less and less effective even with increased intake over time. Once an individual cannot cope with daily life stressors, an allostatic overload can occur. 71 Allostatic load refers to the cumulative burden of chronic stress and life events. 71 “Chronic stress and allostatic load shift the operating range of numerous biological systems” 49 (p. 798). These shifts in biology could also play a role in how workers engage with salt intake and utilize salt and nutrition as mitigating factors in coping with chronic stress, job burnout, and STS. 49 More attention should be given to the allostatic load count of child protection workers due to the connection of chronic stress and allostatic load on the biological makeup of individuals exposed to consistently stressful work environments; the impact of stress on this vulnerable occupational group could dramatically alter their health trajectories in terms of comorbid conditions. This is further evidenced by the vast number of comorbid conditions reported by participants in the current study, such as obesity, hypertension, and diabetes stemming from chronic physical inactivity and heavier salt consumption. Future longitudinal research should be carried out that examines allostatic load counts among child protection workers to determine if the workplace stressors have created significant wear and tear on their bodies since joining the child protection workforce.

Despite being one of the few studies exploring child protection workers’ health and health outcomes, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional survey research design does not allow for any causal inferences. Second, it is unknown how many of the workers experienced a personal traumatic event(s) prior to working in these roles. Some research suggests helping professionals have a higher prevalence of individual trauma than other professionals, which may worsen what is experienced in the workplace. 72 Third, given the topic explored in this study, there is a potential for a self-selection bias. It is possible that the propensity for participating in this investigation was related to a participant’s greater interest in, or direct experience, with personal trauma. Fourth, the sample was somewhat homogeneous because it was predominantly female respondents and primarily African American. Other genders’ and racial/ethnic groups’ perspectives were not captured. Fifth, the generalizability of results are limited due to the convenience sampling methods used within the current study. Last, data were collected from a single southern state, which may not be representative of patterns of STS experienced nationally.

The present study underscores the extent to which STS is associated with multiple health behaviors among child protection workers in a southern state. There does appear to be a significant correlation between STS levels, SRH, lack of exercise, salt intake, and healthcare utilization. Moreover, we found that STS levels were lower among child protection workers who believed health promotion was stressed in their team environment. These results underscore the importance of how physical health relates to a worker’s inward dynamics. Thus, more research is needed to identify how public child welfare workers cope with STS to ensure they do not develop unhealthy health habits that can contribute to or expand health disparities among this vulnerable work group. More importantly, public child protection workers who unsuccessfully abate the deleterious consequences of their work on themselves can harm them and place their clients at further injury by not knowing how to respond and redirect their client’s set of circumstances appropriately. 72 Such oversight has the potential to significantly diminish the service delivery received by the children and families in the child welfare system. As the current study unveils, uncovering the adverse outcomes associated with child protection work becomes critical. It identifies that in our effort as a society to create positive change, we may be establishing a system of oppression under the guise of professionalism and humanitarian effort that disenfranchises a vulnerable work group that is protecting an even more vulnerable population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Javier F. Boyas.

Data curation: J avier F. Boyas, Debra Moore, Maritza Y. Duran.

Formal Analysis: Javier F. Boyas, Debra Moore, Maritza Y. Duran.

Investigation: Javier F. Boyas, Debra Moore.

Methodology: Javier F. Boyas, Debra Moore.

Project administration: Javier F. Boyas.

Resources: Javier F. Boyas, Debra Moore.

Supervision: Javier F. Boyas.

Validation: Javier F. Boyas.

Visualization: Javier F. Boyas, Jacqueline Fuentes, Jana Woodwiss, Leah McCoy.

Writing – original draft: Javier F. Boyas, Debra Moore, Maritza Y. Duran, Jacqueline Fuentes, Jana Woodiwiss, Leah McCoy, Antonella Cirino.

Writing – review & editing: Javier F. Boyas, Debra Moore, Maritza Y. Duran, Jacqueline Fuentes, Jana Woodiwiss, Leah McCoy, Antonella Cirino.

No external funding was obtained for the current study.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The procedures carried out in this research were approved by the University of Mississippi’s ethics committee.

Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflicts or competing interests.

- Case report

- Open access

- Published: 11 September 2017

A case of a four-year-old child adopted at eight months with unusual mood patterns and significant polypharmacy

- Magdalena Romanowicz ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4916-0625 1 ,

- Alastair J. McKean 1 &

- Jennifer Vande Voort 1

BMC Psychiatry volume 17 , Article number: 330 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

41k Accesses

2 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Long-term effects of neglect in early life are still widely unknown. Diversity of outcomes can be explained by differences in genetic risk, epigenetics, prenatal factors, exposure to stress and/or substances, and parent-child interactions. Very common sub-threshold presentations of children with history of early trauma are challenging not only to diagnose but also in treatment.

Case presentation

A Caucasian 4-year-old, adopted at 8 months, male patient with early history of neglect presented to pediatrician with symptoms of behavioral dyscontrol, emotional dysregulation, anxiety, hyperactivity and inattention, obsessions with food, and attachment issues. He was subsequently seen by two different child psychiatrists. Pharmacotherapy treatment attempted included guanfacine, fluoxetine and amphetamine salts as well as quetiapine, aripiprazole and thioridazine without much improvement. Risperidone initiated by primary care seemed to help with his symptoms of dyscontrol initially but later the dose had to be escalated to 6 mg total for the same result. After an episode of significant aggression, the patient was admitted to inpatient child psychiatric unit for stabilization and taper of the medicine.

Conclusions

The case illustrates difficulties in management of children with early history of neglect. A particular danger in this patient population is polypharmacy, which is often used to manage transdiagnostic symptoms that significantly impacts functioning with long term consequences.

Peer Review reports

There is a paucity of studies that address long-term effects of deprivation, trauma and neglect in early life, with what little data is available coming from institutionalized children [ 1 ]. Rutter [ 2 ], who studied formerly-institutionalized Romanian children adopted into UK families, found that this group exhibited prominent attachment disturbances, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), quasi-autistic features and cognitive delays. Interestingly, no other increases in psychopathology were noted [ 2 ].

Even more challenging to properly diagnose and treat are so called sub-threshold presentations of children with histories of early trauma [ 3 ]. Pincus, McQueen, & Elinson [ 4 ] described a group of children who presented with a combination of co-morbid symptoms of various diagnoses such as conduct disorder, ADHD, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression and anxiety. As per Shankman et al. [ 5 ], these patients may escalate to fulfill the criteria for these disorders. The lack of proper diagnosis imposes significant challenges in terms of management [ 3 ].

J is a 4-year-old adopted Caucasian male who at the age of 2 years and 4 months was brought by his adoptive mother to primary care with symptoms of behavioral dyscontrol, emotional dysregulation, anxiety, hyperactivity and inattention, obsessions with food, and attachment issues. J was given diagnoses of reactive attachment disorder (RAD) and ADHD. No medications were recommended at that time and a referral was made for behavioral therapy.

She subsequently took him to two different child psychiatrists who diagnosed disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD), PTSD, anxiety and a mood disorder. To help with mood and inattention symptoms, guanfacine, fluoxetine, methylphenidate and amphetamine salts were all prescribed without significant improvement. Later quetiapine, aripiprazole and thioridazine were tried consecutively without behavioral improvement (please see Table 1 for details).

No significant drug/substance interactions were noted (Table 1 ). There were no concerns regarding adherence and serum drug concentrations were not ordered. On review of patient’s history of medication trials guanfacine and methylphenidate seemed to have no effect on J’s hyperactive and impulsive behavior as well as his lack of focus. Amphetamine salts that were initiated during hospitalization were stopped by the patient’s mother due to significant increase in aggressive behaviors and irritability. Aripiprazole was tried for a brief period of time and seemed to have no effect. Quetiapine was initially helpful at 150 mg (50 mg three times a day), unfortunately its effects wore off quickly and increase in dose to 300 mg (100 mg three times a day) did not seem to make a difference. Fluoxetine that was tried for anxiety did not seem to improve the behaviors and was stopped after less than a month on mother’s request.

J’s condition continued to deteriorate and his primary care provider started risperidone. While initially helpful, escalating doses were required until he was on 6 mg daily. In spite of this treatment, J attempted to stab a girl at preschool with scissors necessitating emergent evaluation, whereupon he was admitted to inpatient care for safety and observation. Risperidone was discontinued and J was referred to outpatient psychiatry for continuing medical monitoring and therapy.

Little is known about J’s early history. There is suspicion that his mother was neglectful with feeding and frequently left him crying, unattended or with strangers. He was taken away from his mother’s care at 7 months due to neglect and placed with his aunt. After 1 month, his aunt declined to collect him from daycare, deciding she was unable to manage him. The owner of the daycare called Child Services and offered to care for J, eventually becoming his present adoptive parent.

J was a very needy baby who would wake screaming and was hard to console. More recently he wakes in the mornings anxious and agitated. He is often indiscriminate and inappropriate interpersonally, unable to play with other children. When in significant distress he regresses, and behaves as a cat, meowing and scratching the floor. Though J bonded with his adoptive mother well and was able to express affection towards her, his affection is frequently indiscriminate and he rarely shows any signs of separation anxiety.

At the age of 2 years and 8 months there was a suspicion for speech delay and J was evaluated by a speech pathologist who concluded that J was exhibiting speech and language skills that were solidly in the average range for age, with developmental speech errors that should be monitored over time. They did not think that issues with communication contributed significantly to his behavioral difficulties. Assessment of intellectual functioning was performed at the age of 2 years and 5 months by a special education teacher. Based on Bailey Infant and Toddler Development Scale, fine and gross motor, cognitive and social communication were all within normal range.