Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Starting the research process

- How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

Published on October 12, 2022 by Shona McCombes and Tegan George. Revised on November 21, 2023.

A research proposal describes what you will investigate, why it’s important, and how you will conduct your research.

The format of a research proposal varies between fields, but most proposals will contain at least these elements:

Introduction

Literature review.

- Research design

Reference list

While the sections may vary, the overall objective is always the same. A research proposal serves as a blueprint and guide for your research plan, helping you get organized and feel confident in the path forward you choose to take.

Table of contents

Research proposal purpose, research proposal examples, research design and methods, contribution to knowledge, research schedule, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research proposals.

Academics often have to write research proposals to get funding for their projects. As a student, you might have to write a research proposal as part of a grad school application , or prior to starting your thesis or dissertation .

In addition to helping you figure out what your research can look like, a proposal can also serve to demonstrate why your project is worth pursuing to a funder, educational institution, or supervisor.

Research proposal length

The length of a research proposal can vary quite a bit. A bachelor’s or master’s thesis proposal can be just a few pages, while proposals for PhD dissertations or research funding are usually much longer and more detailed. Your supervisor can help you determine the best length for your work.

One trick to get started is to think of your proposal’s structure as a shorter version of your thesis or dissertation , only without the results , conclusion and discussion sections.

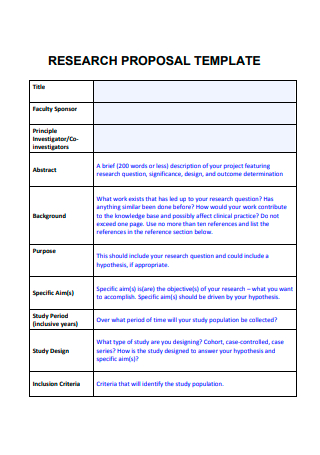

Download our research proposal template

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Writing a research proposal can be quite challenging, but a good starting point could be to look at some examples. We’ve included a few for you below.

- Example research proposal #1: “A Conceptual Framework for Scheduling Constraint Management”

- Example research proposal #2: “Medical Students as Mediators of Change in Tobacco Use”

Like your dissertation or thesis, the proposal will usually have a title page that includes:

- The proposed title of your project

- Your supervisor’s name

- Your institution and department

The first part of your proposal is the initial pitch for your project. Make sure it succinctly explains what you want to do and why.

Your introduction should:

- Introduce your topic

- Give necessary background and context

- Outline your problem statement and research questions

To guide your introduction , include information about:

- Who could have an interest in the topic (e.g., scientists, policymakers)

- How much is already known about the topic

- What is missing from this current knowledge

- What new insights your research will contribute

- Why you believe this research is worth doing

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

As you get started, it’s important to demonstrate that you’re familiar with the most important research on your topic. A strong literature review shows your reader that your project has a solid foundation in existing knowledge or theory. It also shows that you’re not simply repeating what other people have already done or said, but rather using existing research as a jumping-off point for your own.

In this section, share exactly how your project will contribute to ongoing conversations in the field by:

- Comparing and contrasting the main theories, methods, and debates

- Examining the strengths and weaknesses of different approaches

- Explaining how will you build on, challenge, or synthesize prior scholarship

Following the literature review, restate your main objectives . This brings the focus back to your own project. Next, your research design or methodology section will describe your overall approach, and the practical steps you will take to answer your research questions.

To finish your proposal on a strong note, explore the potential implications of your research for your field. Emphasize again what you aim to contribute and why it matters.

For example, your results might have implications for:

- Improving best practices

- Informing policymaking decisions

- Strengthening a theory or model

- Challenging popular or scientific beliefs

- Creating a basis for future research

Last but not least, your research proposal must include correct citations for every source you have used, compiled in a reference list . To create citations quickly and easily, you can use our free APA citation generator .

Some institutions or funders require a detailed timeline of the project, asking you to forecast what you will do at each stage and how long it may take. While not always required, be sure to check the requirements of your project.

Here’s an example schedule to help you get started. You can also download a template at the button below.

Download our research schedule template

If you are applying for research funding, chances are you will have to include a detailed budget. This shows your estimates of how much each part of your project will cost.

Make sure to check what type of costs the funding body will agree to cover. For each item, include:

- Cost : exactly how much money do you need?

- Justification : why is this cost necessary to complete the research?

- Source : how did you calculate the amount?

To determine your budget, think about:

- Travel costs : do you need to go somewhere to collect your data? How will you get there, and how much time will you need? What will you do there (e.g., interviews, archival research)?

- Materials : do you need access to any tools or technologies?

- Help : do you need to hire any research assistants for the project? What will they do, and how much will you pay them?

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Methodology

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

Once you’ve decided on your research objectives , you need to explain them in your paper, at the end of your problem statement .

Keep your research objectives clear and concise, and use appropriate verbs to accurately convey the work that you will carry out for each one.

I will compare …

A research aim is a broad statement indicating the general purpose of your research project. It should appear in your introduction at the end of your problem statement , before your research objectives.

Research objectives are more specific than your research aim. They indicate the specific ways you’ll address the overarching aim.

A PhD, which is short for philosophiae doctor (doctor of philosophy in Latin), is the highest university degree that can be obtained. In a PhD, students spend 3–5 years writing a dissertation , which aims to make a significant, original contribution to current knowledge.

A PhD is intended to prepare students for a career as a researcher, whether that be in academia, the public sector, or the private sector.

A master’s is a 1- or 2-year graduate degree that can prepare you for a variety of careers.

All master’s involve graduate-level coursework. Some are research-intensive and intend to prepare students for further study in a PhD; these usually require their students to write a master’s thesis . Others focus on professional training for a specific career.

Critical thinking refers to the ability to evaluate information and to be aware of biases or assumptions, including your own.

Like information literacy , it involves evaluating arguments, identifying and solving problems in an objective and systematic way, and clearly communicating your ideas.

The best way to remember the difference between a research plan and a research proposal is that they have fundamentally different audiences. A research plan helps you, the researcher, organize your thoughts. On the other hand, a dissertation proposal or research proposal aims to convince others (e.g., a supervisor, a funding body, or a dissertation committee) that your research topic is relevant and worthy of being conducted.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. & George, T. (2023, November 21). How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved April 1, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-process/research-proposal/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a problem statement | guide & examples, writing strong research questions | criteria & examples, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, what is your plagiarism score.

Basic Methods Handbook for Clinical Orthopaedic Research pp 249–254 Cite as

How to Write a Winning Clinical Research Proposal?

- Christian Lattermann 8 &

- Janey D. Whalen 9

- First Online: 02 February 2019

2302 Accesses

This chapter addresses general approaches towards writing a clinical research proposal. The landscape in research has changed in the last decade and has become more translational in nature. Therefore, research proposals are read and evaluated by scientists from various fields that may not be intricately familiar with specific techniques and technique-related jargon. This chapter is designed to address the need for more translational and reviewer-friendly proposal writing and is built on errors and mistakes commonly seen in research proposals.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Shapiro FR. The Yale book of quotations, section: Blaise Pascal. New Haven: Yale University Press; 2006. p. 583.

Google Scholar

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA

Christian Lattermann

Icartilage.com, Boston, MA, USA

Janey D. Whalen

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Christian Lattermann .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

UPMC Rooney Sports Complex, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

Volker Musahl

Department of Orthopaedics, Sahlgrenska Academy, Gothenburg University, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden

Jón Karlsson

Department of Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology, Kantonsspital Baselland (Bruderholz, Laufen und Liestal), Bruderholz, Switzerland

Michael T. Hirschmann

McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada

Olufemi R. Ayeni

Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, NY, USA

Robert G. Marx

Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, NorthShore University HealthSystem, Evanston, IL, USA

Jason L. Koh

Institute for Medical Science in Sports, Osaka Health Science University, Osaka, Japan

Norimasa Nakamura

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 ISAKOS

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Lattermann, C., Whalen, J.D. (2019). How to Write a Winning Clinical Research Proposal?. In: Musahl, V., et al. Basic Methods Handbook for Clinical Orthopaedic Research. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-58254-1_27

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-58254-1_27

Published : 02 February 2019

Publisher Name : Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

Print ISBN : 978-3-662-58253-4

Online ISBN : 978-3-662-58254-1

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

87Chapter 4 Writing your research proposal

- Published: November 2011

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

In many ways it’s a reflection of yourself as a researcher and an insight into your proposed work. A poorly written proposal has the ability to wreck a project and embarrass the researcher before it has even begun. Similarly, a well-constructed proposal bodes well for the success of the project and displays the researcher in a good light amongst their peers and supervisors. The research proposal identifies: • What the topic is, both in terms of background and the individual area of interest. • What you plan to accomplish and why it needs doing. • What in particular you are trying to find out, i.e. the research question. • How you will get the answer to your question, i.e. your methodology. • What others will learn from it and why it is worth learning. • How long it will take. • How much money it will cost. Through your research proposal you are attempting to convince potential supporters that your project is worth doing, you are scientifically competent to run it, and are in possession of the necessary management skills to ensure its completion. The proposal concisely describes the key elements of the study process, although in sufficient depth to permit evaluation. It is a stand-alone document that must contain evidence of an answerable question, demonstrate your grasp of the literature, and also clearly show that your methodology is sound. A research time-table is required to demonstrate a realistic appreciation of how the study will progress through time. The research proposal serves many purposes to many different parties. Amongst these purposes, some of the key ones are: • Acting as a route map and timetable for all involved in your project. • Giving a clear overview of your planned work to ensure favourable decision at ethical review. • Gaining funding to carry out your proposed study. • Securing a place to undertake a higher scientific degree. • Being an opportunity to ‘blow your own trumpet’ on paper. Although there are several bodies who will be obliged to see your proposal, there is a reasonable chance it will end up being wider read than this, so a coherent piece of work will reflect well on you.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

- Google Scholar Indexing

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Writing a research proposal

The format of a research proposal varies depending on what or who it is required by. They can vary in length, ie. be very concise or quite long and detailed. Also the headings for the different sections can vary. Therefore, this guide deals with the research proposal in its most generic form, which should be easily modifiable to fit the criteria for any research body.

The ultimate aim of any research proposal is to convince people that your research is important, has not been done before, is worthwhile and is feasible. Hence you have to make a strong argument for your research. The language used should be clear and easy to understand, as often non-experts will assess it. Some funders may, and the Research Ethics Committee application form will, want a ‘lay’ summary in addition to your basic proposal document. It is usually only in the background and methodology sections that writers tend to assume that the intended audience has a particular knowledge of their research area.

Additionally, it is crucial that different sections of your research proposal should link or follow on from each other, eg. the research question should link with the methodology. This may sound obvious, but revisions of one section can lead to mis-matches. Check this before submitting your proposal!

Typical stages in a research proposal

1. The purpose of a research proposal is:

- To help to focus on a relevant and current topic.

- To identify a gap or inadequacy in the research literature.

- To make sure that these are your ideas, and to help you to focus and crystallise your ideas.

- To help you to focus on what the actual stages involved in the research process will be, eg. the exact methodology and data analysis that will be adopted.

- To justify a proposed research project to a particular audience, eg. supervisor, departmental or faculty committee, external funding body etc.

2. Some strategies before you start:

- Search through literature for topic related articles and books, ie. search through databases/catalogues/journals etc.

- Look at what is already being done in the area i.e. existing data and research.

- Read critically, ie. look for interesting and suitable gaps – areas for research.

- Talk to your employer for approval – there is no point in starting research that you will not be allowed to complete.

- Talk to your local research and development teams. They will be able to tell you the specific criteria for any research proposal and may highlight some issues that you have overlooked.

- Talk to experts or supervisors in the field – in person, phone, letters, e-mail.

- If it is helpful, use concept maps to link ideas, and or formulate questions that the literature review should address.

3. Identifying your research question:

Any research proposal needs to have a clear research question for it to succeed. Without a clear question research will become confused and lack direction. Subsequent analysis will be difficult because the research question is key to forming your hypothesis or aims, and later analysis.

Do start by writing a question, not a statement. This will help clarify exactly what the issue is that you are trying to find a solution to. Hypotheses, aims etc can then follow from this.

Your research question should:

- Be as clear and concise as you can make it. Don’t use multi-barrelled questions if you can avoid them.

- Be informative – state your population of interest, locality etc.

- Avoid technical jargon – this is the golden rule in most areas of research proposals. Remember that your research question is what will capture the interest of the reader / assessor.

- Relate to the proposal title – often the research question is quoted as the title of the proposal.

- Relate to the aim of the research – again, the research question is often quoted as the research aim.

It should be obvious from your question alone what the project will aim to do, and on who.

4. Project title:

The title should be brief but informative. It is important that it is clear and easy to understand, and describes what your proposed research is. As previously stated, this is often the research question.

5. Abstract or summary:

This is a very important section which bears a disproportionate share of responsibility for success or failure of a proposal, as it may act as the initial ‘hook’.

It needs to be written for a wider audience, so technical vocabulary has to be limited. The abstract also needs to come quickly to the proposed research. Abstracts for grant proposals usually begin with the objective or purpose of the study, move on to methodology (procedures and design), and close with a modest but precise statement of the projects’ significance.

The significance should:

- Be about one paragraph – if it needs any longer it is advisable to rethink your research or break it down into more manageable chunks.

- Explain to the reader why the study is “significant”, in the sense of advancing general knowledge.

- Explain what the benefits to the patient / health community are.

- Encourage funding.

Although you present this first in the document, write it last so that its content accurately reflects the whole proposal.

6. Introduction:

The introduction is also written so that a more general audience can easily obtain a general idea of what the project is about, and the major concepts involved. It will also typically begin with the purpose of the proposed research. The introduction will typically be quite short, leaving the detail to the background and methodology sections.

7. Background:

It is only in the background and methodology sections that writers tend to assume that their intended audience is a specialist in their research area, and so use more technical language.

This section will include the literature review.

The purpose of a literature review is as follows:

- To become familiar with the research area and keep up to date with the current research in your area of interest.

- Identify an appropriate research question.

- Establish a theoretical framework for the research.

- Justify the need for the research.

Through the actual process of writing the literature review you, the researcher, can explore the relevant literature, formulate a problem, defend the value of the research, and compare the findings and ideas with your own. The literature review establishes a context and orientates the reader to your research topic.

The common structure of the literature review is likened to a “funnel effect”, which goes from general to more specific studies etc directly relating your intended project, ending with your research question, problem or objective.

In summary the stages of a literature review are as follows:

- General statement(s) about the field of research – the setting.

- More specific statements about the previous research.

- Statements that indicate the need for more investigation.

- Very specific statement(s) of the research question, problem or objective.

Your Trust librarians will be able to help with appropriate literature searching techniques if required.

8. Methodology:

The method or methodology section describes the steps you will follow in conducting your research. It is a very important section as assessors will scrutinise it to evaluate the feasibility and likelihood of successful completion of your proposed research.

Examine methodology sections of research articles in your research area. Arrange to discuss your research with a statistical and/or methodological specialist (Trust and other local research clinics / groups). Discuss with other researchers in your discipline the methodologies they have adopted. Consult methodology texts and statistical packages.

Overview of research:

Population/sample to be studied, including:

- How you have arrived at the sample size.

- How they will be recruited.

- Location of the research.

- Restrictions/limiting conditions.

- Sampling technique.

- Procedures.

- Analysis tools and methods.

9. Timescale:

10. Budget:

11. Ethical considerations:

- Benefits vs risks of the involvement in the project.

- Receipt of informed consent.

- Protection of participants (including data protection and storage issues).

- Privacy, minimising discomfort etc.

- Community values.

12. Dissemination strategy:

- The targets of your research eg. staff, patients, service users or carers,

- services locally and/or nationally,

- policies that drive the above services.

13. Bibliography and references:

Good luck with your project!

Useful reading: Bowling A (2002), Research Methods in Health: Investigating Health and Health Services 2Rev Ed edition, Open University Press Polgar S and Thomas SA. (4 th Edition 2004) Introduction to Research in the Health Sciences. Churchill Livingstone. MRC Good Research Practice Guidance

UCL Doctorate In Clinical Psychology

Guidelines for the Research Proposal

The purpose of the research proposal is to help you organise your ideas about your major research project, and to enable you to get feedback on what you are planning to do. It is worth putting in careful thought at this stage: it will mean that the project is more likely to run smoothly in the long run, and much of what you write in it can eventually be recycled into the final thesis write-up. The proposal is also needed for NHS ethics applications.

The proposal is a course requirement, but is not an assessed piece of work. It is due early in Term 1 of Year 2 (the date will be announced). Please submit an electronic copy to the Research Administrator (following the procedure detailed on the Project Support Moodle site).

There is no formal word limit (but conciseness is essential): we suggest that you aim for around 2500 words, plus references and any necessary appendices. Format it double-spaced, and include page numbers so that reviewers can easily refer back to specific points. Since it is not assessed work, it does not need your code number; please put your name on it.

Some sample proposals from previous years are available on the 'Proposal' (Topic 4) section of the Research Project Support Moodle.

The structure and content of the proposal is similar to that of the introduction and method sections of a journal article:

A title page with (1) the provisional title of the project (this can be modified later on), (2) your name, (3) your internal and external supervisors, (4) the setting where the study is likely to take place and (5) the date. If you are doing a joint project with other trainees, this should be stated here and the other trainees should be named. (Including all of this information on the title page is very helpful for the course's administrative purposes.)

The introduction (3 or 4 pages) states what the research topic is and why it is important. It succinctly reviews previous research in the area and relevant psychological theory, and summarises the rationale for the intended study. The introduction should end with one or more clearly stated research questions or hypotheses.

The method section (3 or 4 pages) describes in detail the proposed research methods: the setting, participants, sample size, research design, measures, ethical considerations, and data analysis procedures. For quantitative research, the sample size needs to be determined by a power calculation, which should be reported here (a separate document on power calculations is on the Project Support Moodle site). Measures that are not well known should be included as an appendix. For qualitative research, describe your interview schedule (append a draft) and your proposed method of analysis, including the types of "credibility checks" that you propose to use.

The service user involvement section (one or two or paragraphs) describes how the needs and views of service users or other relevant members of the public have shaped or will shape your project. This could include examples of service users influencing: (1) the choice of topic to be researched; (2) decisions about methodology; (3) the design of materials such as invitation letters and participant information sheets; (4) the design of a qualitative interview schedule, and (5) the ethics of the research. Please outline any plans for service user involvement later in the project. Remember, whilst there are formal ways of eliciting service user views, such as the use of focus groups and services such as FAST-R ( Feasibility And Support to Timely recruitment for Research ), informal sources of information are also valuable, and can be described here. This might include conversations with individual service users, experiences from clinical work, or interactions that take place on-line.

Whilst we strongly encourage trainees to use service user input when developing their research, this is not obligatory. Sometimes consultation with service users and other members of the public is not necessary, for example in some studies of healthy volunteers. If there has been no input from service users or members of the public, please use this section to state this, and briefly (a couple of sentences) explain why.

The feasibility section has a brief appraisal of how realistic your project is in practical terms, particularly with regard to recruiting participants. Many trainees (and their supervisors!) tend to be over-optimistic at this stage of the project, and it is a good idea to address potential recruitment problems at the outset. You should also include a fallback plan in case things go pear-shaped (which, sadly, in clinical research they often do). It would be helpful if you provided an estimate of what the smallest viable sample size would be, so that we (and you) have an idea of what a worst-case scenario might look like. A general timetable for the project is given in the guidelines for the major research project . If you anticipate any major departures from this, give details and a rationale.

The joint working section is, of course, only required if you are proposing a joint project. In this section provide a brief outline of what your anticipated contribution to the overall study will be, and what will be done by others. There should be a statement of how your research question(s) and analyses will be distinct from those of other students involved in the project. It will be helpful to consult the course guidelines on joint projects when planning any joint study.

The institutional arrangements , e.g., the setting, and who has agreed to be your internal and external supervisors.

The costings section sets out any substantial expenses that the project may entail. Note that the Department has limited funds and does not normally fund projects costing more than £250 over two years (see the course document on research funding ). If your project is likely to cost more than this, the course may possibly be able to provide some additional funding up to £400, although this cannot be guaranteed. It is your responsibility to secure additional funding for expenses beyond that allocated by the course.

The reference list gives all cited works. (It is important to check that this is complete, because reviewers may consult some of your references to understand the background to your study.)

Appendices include measures not in common use, draft qualitative interview schedules, etc.

Supervisors' input

Research proposals usually need to go through several drafts. Show your internal and external supervisors a draft early enough so that you can incorporate their comments into a revised draft before submission.

Review of the proposal

The proposal will be read by one of the academic staff, and will be discussed at a proposals review meeting in October. The resultant written feedback that you receive (towards the end of October) will give you a clear indication of the general feasibility of your project, and suggest any changes that will need to be made before it goes ahead.

This process counts as the "peer review" that is required for all NHS ethics applications. Therefore, once your proposal has passed the review stage, those of you applying for NHS ethics should contact Will Mandy to ask for a letter confirming that your project has been successfully peer reviewed.

Printable version of this page

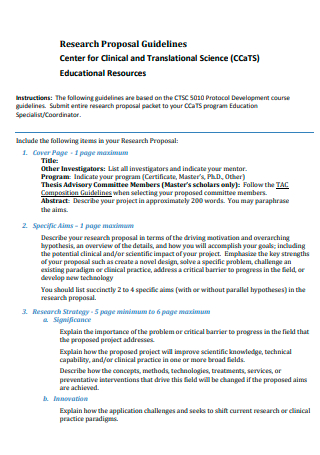

Center for Clinical and Translational Science (CCaTS)

Postdoctoral master's degree program, research proposal.

The mentored research experience is a key component of the Postdoctoral Master's Degree Program in clinical and translational science.

Students develop their research proposals in CTSC 5010: Clinical Research Proposal Development, with a deadline based on the academic cycle listed below. Members of the CCaTS Scientific Review Group review research proposals, and the Master's and Certificate Programs Executive Committee approves them.

Include these items in your proposal packet:

- Research Proposal Packet Cover Page (PDF) .

- The proposal. Research proposals are approved by the CCaTS Master's and Certificate Programs Executive Committee and Mayo Clinic Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences (MCGSBS). Follow the Research Proposal Guidelines (PDF) , and construct your specific aims in a way that clearly defines the two or three publications resulting from the proposal.

- Research Proposal Project Timeline form .

- Translational Impact Statement. In one paragraph or a maximum of one page, describe the translational gap that your project will fill. You may include key literature that helped you identify that gap.

- Names. Your name should be first.

- Member expertise. Stick to the expertise that has value for this specific proposal.

- Help collect data?

- Train the student leader on necessary skills?

- Provide mentorship for the student leader for their research?

- Communication. How will the team meet, for example, in person or online? How often? How will the team resolve differences of opinion? What is the structure of meetings? Be clear about how you are situated in this structure.

- Final statement. Include a statement such as, "This team brings together fields of expertise that uniquely allow us to achieve [define a positive outcome]."

- Audience. Remember that you want to be writing for a broad readership. Limit your use of jargon and strive for clarity whenever possible

- Current curricula vitae for you and your mentor.

Thesis Advisory Committee (TAC) form. Complete the Proposed Master Thesis Advisory Committee form (PDF) . All TAC members are expected to provide scientific peer review and approve your proposal prior to submission. After your TAC has been approved by the CCaTS Master’s and Certificate Programs Executive Committee, the program staff will submit the MCGSBS TAC e-form on your behalf.

Read more about the Thesis Advisory Committee .

Verification statement from your department or division. This statement must document that peer review of the proposal has taken place and that the proposed work is scientifically sound and clinically meaningful. The minute excerpt from your department or division research committee or minute excerpt used for submission to the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board (IRB) may be used.

Note: If your project is deemed nontherapeutic and minimal risk — for example, a retrospective chart review — the IRB does not require divisional review and the CCaTS Minimal Risk Study form (PDF) is used in lieu of department or division verification.

If the proposal is part of a larger project, submit the abstract and documentation of scientific peer review of the larger project (that is, the minute excerpt from the appropriate research committee or funding agency).

- IRB approval email notification. This email notification documents that IRB review of your proposal was completed and approved. If the IRB has not yet approved your proposal, submit the email notification when approved. If your proposal is part of a larger project, please submit the IRB approval for the larger project.

- Research Proposal Potential Reviewers (PDF) .

Research proposal review criteria

The CCaTS Master's and Certificate Programs Executive Committee considers whether the thesis that will result from the proposal has the potential to meet the prescribed thesis standards and is feasible within the time frame identified. Proposals are reviewed by the CCaTS Scientific Review Group using these criteria:

- Clinical or translational research. Does the project meet the definition of clinical or translational research? If an animal model is being studied, has the scholar justified its significance to human disease?

- Scientific peer review. Is the hypothesis significant? Is the study design valid? Is the data collection and analysis plan consistent with the study goal? Is there statistical justification?

- IRB review. Has IRB approval for the project been obtained, or is it pending? If the scholar's project is part of a larger project, has documentation been provided showing IRB approval for the larger project?

- Authorship. Will the scholar be the first author on publications resulting from this project? If the scholar's project is part of a larger, multiauthor study, has the scholar explained the contribution to authorship? Will the project result in at least one publication?

- Feasibility. Is there sufficient funding for the project? Is there sufficient time to collect data and recruit participants? Does the project align with the scholar's research interests?

- Recruitment plan. Has a satisfactory subject recruitment plan, including a timeline, been provided?

- Current status. Has the status of the project been provided? For example, "Fifty percent of the data are collected, with data collection expected to be complete in six months."

More about research at Mayo Clinic

- Research Faculty

- Laboratories

- Core Facilities

- Centers & Programs

- Departments & Divisions

- Clinical Trials

- Institutional Review Board

- Postdoctoral Fellowships

- Training Grant Programs

- Publications

Mayo Clinic Footer

- Request Appointment

- About Mayo Clinic

- About This Site

Legal Conditions and Terms

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Notice of Privacy Practices

- Notice of Nondiscrimination

- Manage Cookies

Advertising

Mayo Clinic is a nonprofit organization and proceeds from Web advertising help support our mission. Mayo Clinic does not endorse any of the third party products and services advertised.

- Advertising and sponsorship policy

- Advertising and sponsorship opportunities

Reprint Permissions

A single copy of these materials may be reprinted for noncommercial personal use only. "Mayo," "Mayo Clinic," "MayoClinic.org," "Mayo Clinic Healthy Living," and the triple-shield Mayo Clinic logo are trademarks of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research.

Advertisement

- Previous Issue

- Previous Article

- Next Article

Preparation of the Investigator for a Proposal

The research proposal, insights into the reviewer's perspective, conclusions, writing successful research proposals for medical science .

(Schwinn) Professor of Anesthesiology and Surgery; Associate Professor of Pharmacology/Cancer Biology, Duke University Medical Center; Senior Fellow, Duke Pepper Aging Center.

(DeLong) Associate Professor, Division of Biometry and Medical Informatics, Duke University Medical Center.

(Shafer) Staff Anesthesiologist, Palo Alto VA Health Care System; Associate Professor of Anesthesia, Stanford University.

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Cite Icon Cite

- Get Permissions

- Search Site

Debra A. Schwinn , Elizabeth R. DeLong , Steven L. Shafer; Writing Successful Research Proposals for Medical Science . Anesthesiology 1998; 88:1660–1666 doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-199806000-00031

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

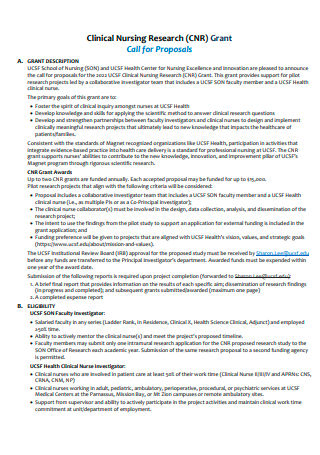

HIGH-QUALITY research proposals are required to obtain funds for the basic and clinical sciences. In this era of diminishing revenues, the ability to compete successfully for peer-reviewed research money is essential to create and maintain scientific programs. Ideally, the essentials of “grantsmanship” are learned through observation and participation in grant preparation, but the training environment experienced by most physicians typically focuses on clinical skills. Most physicians are never exposed to a research environment and therefore do not learn how to write grants. The result is that many clinical studies, even when designed by skilled clinicians and those that address important clinical questions, often do not compete successfully with proposals written by basic scientists. This creates a perception that clinical studies are not favorably viewed by research review committees. The opposite is probably closer to the truth; research review committees are very keen to fund excellent clinical research. Although greater numbers of researchers with Ph.D. degrees have applied for National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants compared with researchers with M.D. degrees over the last 10 yr, funding rates (percent applications funded) have remained approximately the same for these investigators ( Figure 1 ; 1995 success rates: all degrees, 6,759 [26.8%]; M.D. - Ph.D., 370 [23.1%]; M.D., 1,518 [28.1%]; Ph.D., 4,746 [26.8%]; other degree, 125 [23.1%]).[section]

![proposal for clinical research Figure 1. Overall success rates for NIH funding of scientific applications, 1986 - 1995. No difference in funding rate is observed between applicants holding M.D. versus Ph.D. degrees. As the success rate for first-time applications was 11.3% in 1993, it is apparent that resubmission of a revised application significantly increases the overall chance of having research proposal ultimately funded.[section]](https://asa2.silverchair-cdn.com/asa2/content_public/journal/anesthesiology/88/6/10.1097_00000542-199806000-00031/4/m_31ff1.png?Expires=1714478590&Signature=DF7-UG0u~UJKg~wyOGmJ4waYoPjUxVIrlVBxQ0~ghz-Jf-oIsRlCqxm4Qt3wH4M-l6wWrzOwEaqCekVUFcbGhitKEhM8DIDKCOI~6XmRDAUa~phZZz2tt9Pl7RaAw2tnyOQTOVU-cDkRhxGNGTz1BeeAZ9Tg4v73jLJ6ltntapoy6Sp0kQBf0iHxYPBO3RDE~ds4jxXNEMLjNbzXSIWapjuJyb1rSYj0j9tRPeFq6UHlMddud6m4R67UnrD5KsRECAkYP14B9KZFv06k7IiCdsDfrxfswUJ2jY3gDlsQDLYqKaaXRWiCHHeE4fNLtu5jR-DXfly1vlt4igxeVh8sjw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Figure 1. Overall success rates for NIH funding of scientific applications, 1986 - 1995. No difference in funding rate is observed between applicants holding M.D. versus Ph.D. degrees. As the success rate for first-time applications was 11.3% in 1993, it is apparent that resubmission of a revised application significantly increases the overall chance of having research proposal ultimately funded.[section]

Capable medical researchers ultimately write research proposals for funding by the NIH. Standards of excellence for NIH grants are high (only the top [almost equal to] 20% of grants are funded). Research questions posed must be hypothesis driven; the investigator must be qualified to perform the study; and preliminary evidence should be presented demonstrating that the research is feasible and will answer the questions posed. The goal of this article is to review important elements of successful research proposals, with emphasis on funding sources available to the anesthesiology community. Two important anesthesia-specific organizations exist to support anesthesia research - The Foundation for Anesthesia Education and Research (FAER, an organization under the auspices of the American Society of Anesthesiologists) and the International Anesthesiology Research Society (IARS).

Successful applications for research support from FAER and IARS have many of the characteristics of grants funded by the NIH and other peer-reviewed funding sources. These characteristics include (1) a highly qualified investigator(s);(2) for junior investigators, a mentor with a successful track record in scientific investigation, peer-reviewed funding, and mentorship of fellows and faculty;(3) a supportive academic environment; and (4) a scientifically sound proposal. Each of these characteristics is discussed in the subsequent sections.

Training of the Investigator

One of the most important components of a successful research proposal is a well-trained investigator. Training in clinical anesthesia is not training in research methodology or scientific thinking; it does not prepare an individual for a career in investigation. Although obvious for basic science research, clinical research also requires commitment of a minimum of 1 yr of dedicated training with a good mentor, and more typically 2 - 3 yr in the field of the proposed research. The applicant also needs to demonstrate commitment to a career in investigation. Several years of scientific training is the first demonstration of such commitment. Research proposals must document institutional support for nonclinical time, and the investigator must provide evidence that this time has been used wisely and will continue to be dedicated to the proposed research.

The research proposal must document a track record of productivity by the investigator. This expectation increases as the training and career of the investigator progresses. Fellowship awards do not have an expectation of prior research training, so publications from prior research are not expected. At the fellowship level, outstanding letters of recommendation, undergraduate and medical school performance, and related accomplishments are most important. Because previous training is not required of the fellowship applicant, prior success of the mentor (publications and track record with previous trainees) weighs heavily in the fellowship review. For junior faculty, peer-reviewed publications are expected from the fellowship period. Young Investigator Annoucements (from FAER) and several new IARS awards require several years as a successful junior faculty member, so expectations of demonstrated research success are further increased. The investigator must demonstrate (1) rigorous training, (2) commitment to research, (3) an appropriate career path, and (4) a track record of productive work. None of these are trivial issues, and none can be easily accomplished without making a commitment to research early in the academic career.

The quality of the mentor is another important aspect of awards granted to fellows and junior faculty. Identification of a mentor is explicitly required for FAER and certain junior level NIH grant applications. First and foremost, the mentor must be a successful investigator. Criteria for this include a track record of publication in the area of the proposed research, continued peer-reviewed funding, and a history of successfully training young investigators. Although mentorship is not considered heavily in more senior grant applications, input from a more experienced investigator often remains beneficial throughout one's career (as we can personally attest to). In addition to the mentor, high-quality coinvestigators, collaborators, and consultants also play important roles in strengthening a research proposal.

Environment

Good research is best accomplished in a supportive, cooperative environment. Because of the changing climate of clinical medicine, researchers (both clinical and basic science) face increasing pressure to minimize research time. It is not possible to become a successful investigator in one's spare time. Documentation of adequate nonclinical time for research (not for committee meetings or other unrelated tasks) is essential. Receiving funding at a junior level often enables the department to match funds or to guarantee nonclinical time to the budding investigator. In general, the more non-clinical time available to an investigator, the more competitive the application.

Other important elements of the environment include people, space, and institutional resources. People include mentors, consultants who can help with specific methodologies, statistical support, helpful colleagues, experienced technicians, a clinical research team, and a dedicated chairperson. There must be adequate space for performing the proposed studies, office space for research personnel, and storage space for equipment and supplies. Institutional resources include related departmental and interdepartmental seminar series, a critical mass of investigators in a related area, instrument development and repair shops, and necessary laboratory space and common facilities.

Criteria for a sound research proposal are the same whether the proposal is submitted to NIH, FAER, IARS, or other funding sources. In crafting a proposal, it is essential to consider the perspective of the reviewer; therefore, items of interest to the reviewer are listed after general definition of the grant proposal.

Review committees receive dozens of grants. NIH study sections may review as many as 150 proposals during one session. Typically, only two or three reviewers are assigned to read each grant in detail, but everyone is expected to read each abstract. Hence, the abstract is often one of the most important parts of the research proposal. The abstract should address the significance of the question and the overall topic, state the hypothesis, and point out key preliminary data. Additionally, the abstract should provide a synopsis of methodologies planned. In the end, the reviewer must be convinced that the applicant is uniquely (or ideally) suited to undertake this important study by the end of this concise paragraph.

Body of the Grant

Specific Aims. The specific aims section is critically important in a scientific proposal. It is here that the investigator crystallizes the overall goal of the research and states specific hypotheses.