The Gender Analysis Tool With Topical Questions

GENDER ANALYSIS QUESTION TABLE

More specifically, to make the GAF more accessible, the tables below offer topical questions to guide the content of research questions for each domain at each level of the health system for gender analysis.

For each level of the health system: 1) individual and household; 2) community; 3) health facility; 4) district; 5) national, there is one table with illustrative questions for each of the four domains.

The first table in each section contains general topical questions that pertain to that level of the health system, and the second table contains topical questions pertinent to a specific area of health (e.g., HIV, FP). The topical questions are both illustrative and descriptive and offer a set of key questions for a range of Jhpiego health areas. They should inform what kind of information should be gathered using a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods, but are not intended to be directly transferred to a survey or interview guide. Instead, the questions should be further adapted for a specific purpose, to a particular context, and to the type of data collection tool.

Sample data collection tools and resources that pertain to each level and set of tables are found at the end of each set. Annotations of the data collection and analysis resources listed appear in Annex III. The citations contain a hyperlink to the full document of each resource. To keep the size of the tool manageable, we focused questions on one health area per level of the health system.

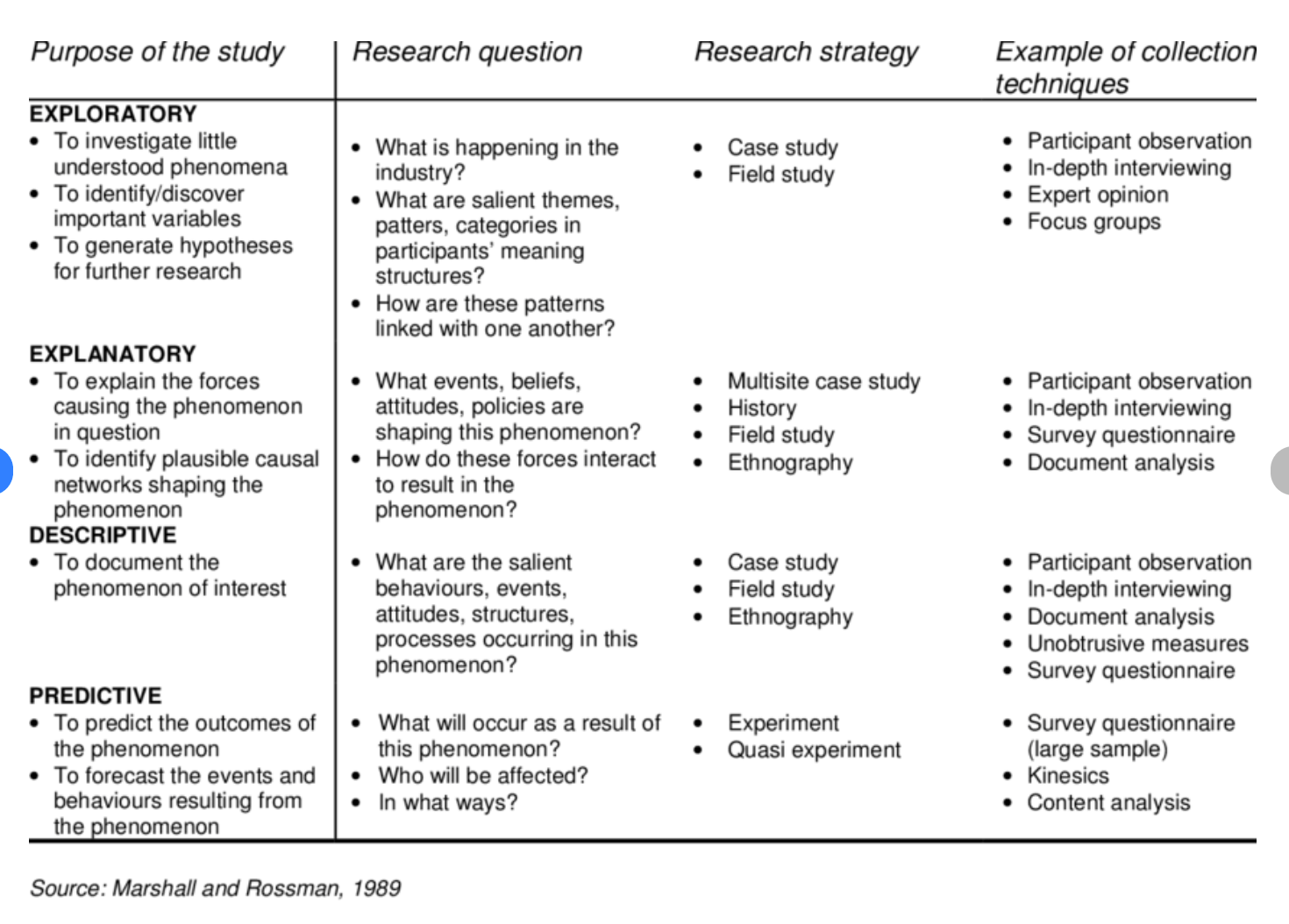

The table below illustrates the level of questions that this Toolkit aims to provide using HIV-related gender analysis and assessment questions. The topical questions in the GAF tables are more specific than broader research questions and less specific than the types of questions that would appear on a survey or as part of a qualitative interview guide, which would have to be adapted and tested prior to their application for the setting and type of tools to be used.

| RESEARCH QUESTIONS (BY DOMAIN) |

| TOPICAL QUESTIONS |

| QUANTITATIVE DATA COLLECTION QUESTIONS | ||

A behind-the-scenes blog about research methods at Pew Research Center. For our latest findings, visit pewresearch.org .

- Demographic Research

Adapting how we ask about the gender of our survey respondents

Knowing the gender of our survey respondents is critical to a variety of analyses we do at Pew Research Center. Gender affects how a person sees and is seen by the world. It’s predictive of things like voting behavior , the wage gap and household responsibilities .

On nearly all surveys we conduct in the United States, we ask people, “Are you male or female?” (Or, in Spanish: ¿Es usted hombre o mujer? ) While this wording has been the standard question we’ve used for years, we wondered if we could find a new way to ask about gender that would acknowledge changing norms around gender identity and improve data quality and accuracy, while still maintaining the neutrality that defines the Center.

We organized a research team to answer this question and — if the answer turned out to be yes — determine how we might modify the way we ask about respondents’ gender. Ultimately, we settled on a new version of the question: “Do you describe yourself as a man, a woman, or in some other way?” (Or, in Spanish: ¿Se describe a sí mismo(a) como un hombre, una mujer o de alguna otra manera? )

Here, we detail how and why we came to this decision.

We considered attitudes, laws and best practices in research

Gender is a social construct based on how people see themselves and how others see them. Sex, by contrast, is a biological construct assigned at birth. An estimated 1.4 million U.S. adults are transgender, which is defined in this post as people who identify as neither a man nor a woman (sometimes people in this group use the term “nonbinary”) or those who identify with a gender different from the sex they were assigned at birth . (It is worth noting that some people in this group might use terms other than “transgender” to describe themselves.) Roughly one-in-five U.S. adults know someone who uses a gender neutral pronoun such as “they” instead of “he” or “she,” and 17 states and the District of Columbia have adapted to this evolution in gender identity by adding a nonbinary option to driver’s licenses.

Other survey researchers have also begun adapting their gender questions. Some surveys ask a two-step question to determine both sex assigned at birth and current gender identity. Others ask whether a respondent is male or female and whether they self-identify as transgender. Meanwhile, qualitative research has looked at the best terms to use when asking about gender identity.

Given that many Americans view gender in a way that is more complex than can be captured in just the two response options of “male” and “female,” adding a third option could improve data accuracy by ensuring the data are representative and inclusive of all types of voices. Proponents of a third gender response option may also perceive the lack of such an option as exclusionary. On the other hand, the Center was concerned that adding a third option could possibly alienate the 56% of U.S. adults who said in a 2018 survey that forms or online profiles should not include an option other than “man” and “woman.” If either group stopped participating in our surveys, it would introduce bias and harm data quality. Another consideration was how a third gender response option would translate into Spanish. The Center’s surveys are almost always conducted in both English and Spanish, and little existing research has addressed how to phrase a revised gender question in Spanish.

Prior research informed our new gender identity question

In previous studies , researchers have conducted a variety of tests about the best way to ask about gender. Informed by this research, we decided to make our starting point the question wording used in the National Crime Victimization Survey : “Do you currently describe yourself as male, female or transgender?” We then made two changes based on previous research.

First, we replaced “transgender” with the phrase “in some other way.” Some people who identify as neither male nor female do not identify with the term “transgender,” instead preferring “nonbinary,” “genderfluid” or other terms. “Transgender” also isn’t necessarily mutually exclusive from “male” and “female.” For example, some people consider themselves both male and transgender. In addition, there is no Spanish equivalent of “transgender,” and around three-in-ten U.S. adults do not have a clear understanding of what “transgender” means.

Second, we replaced “male” and “female” with “a man” and “a woman.” The words “male” and “female” refer to a person’s biology or sex , while the words “man” and “woman” are cultural terms that are more consistent with the concept of gender.

We conducted an experiment to address outstanding concerns

In June and July 2020, we conducted an online opt-in survey of 5,903 internet panelists to test two alternative gender question options in English and Spanish. A total of 4,931 responded in English and 972 responded in Spanish. The survey took an average of 12 minutes to complete and included questions about the coronavirus outbreak, political approval and other demographics.

Respondents were randomly assigned to receive one of three sets of gender questions after receiving other demographic questions. One group of respondents (n=1,654) received the standard Pew Research Center question. Another group (n=2,611) received a question about sex, followed by a question about gender:

1. “Were you born male or female?” ( ¿Su sexo al nacer fue masculino o femenino? )

2. “Do you describe yourself as a man, a woman, or in some other way?” ( ¿Se describe a sí mismo(a) como un hombre, una mujer o de alguna otra manera? ) The phrase “some other way” also included a text box for respondent specification.

In asking these questions, it was especially important that we minimized the number of adults who might incorrectly be classified as transgender. Since the U.S. transgender population is small, estimates of the size of this population might be artificially inflated even if a small number of respondents accidentally chose the wrong answer. To minimize this error, we asked a third follow-up question of those whose responses to these two questions did not match:

3. “Just to confirm, you were born [male/female] and now describe yourself [as a man/as a woman/in some other way]. Is that correct?” ( Solo para confirmar, su sexo al nacer fue [masculino/femenino] y ahora se describe a sí mismo(a) [como hombre/como mujer/de otra manera]. ¿Es eso correcto? )

If respondents said their answers were not recorded correctly, they were given the opportunity to re-answer both questions.

A final group (n=1,638) received the same questions as the second group, but in reverse order; they received the question about gender identity before the question about sex assigned at birth. This group was also asked to confirm if their answers to the two questions didn’t match.

At the end of the survey, immediately following the gender/sex questions, we asked all respondents whether they thought our questions were biased (and, if so, why), followed by two questions about their views on transgender rights and offering a third gender option on forms and online profiles.

Unweighted estimates from this experiment are sprinkled throughout the remainder of this post. While opt-in samples are not ideal for creating point estimates, they are useful when comparing experimental wording conditions, as was the purpose here. To further improve comparability and to ensure we had reliable estimates, we also implemented a series of quotas and included an oversample of less-acculturated Hispanics (as determined by a combination of language skills, years living in the U.S., type of media consumption and self-described cultural affiliation).

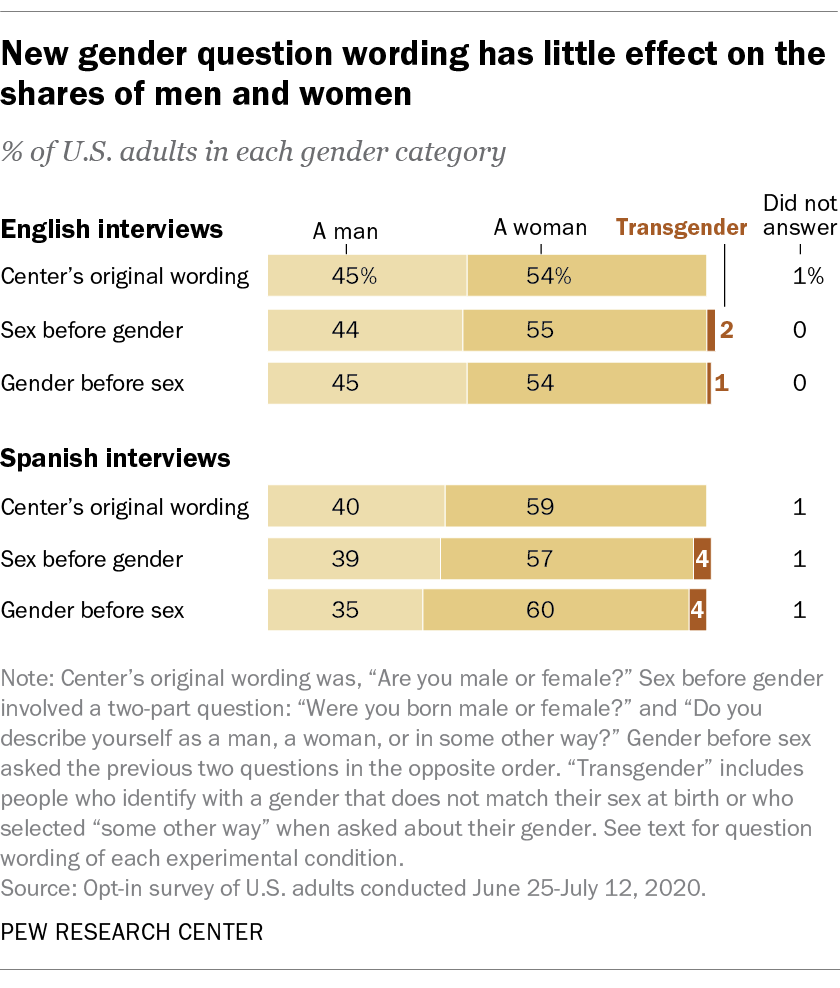

Data quality improved with the new gender question

Regardless of the way in which we asked respondents their sex/gender, we observed consistent distributions among men and women, suggesting little effect of the question wording for most people. However, among English-speaking adults who received the new gender questions, 1.5% selected the third, nonbinary response option or chose a gender inconsistent with their sex, suggesting that the inclusion of the third option had the intended effect on being more inclusive and improving data accuracy.

There was some concern that people who consider themselves a man or woman may not wish to be defined by their gender and instead opt for the third option and write in a non-gender term to describe themselves, such as “human” or “mother” or “scientist.” A large number of these types of responses would have suggested that the revised question would introduce error and hurt data quality. Luckily, we only observed four of these types of responses among English speakers, affecting the estimate by 0.1 percentage point and suggesting that it was not a problem.

Providing a third gender option didn’t alienate people

Fewer English-speaking respondents to our 2020 survey said they opposed the inclusion of a third gender response option on forms or online profiles (44%) than in our 2018 survey. However, 44% is still a substantial share of respondents. We were concerned that opponents would find our new, more inclusive question off-putting. This concern did not appear in the data. Fewer than 1% opted not to answer the gender question.

The revised gender question also didn’t cause more people to stop taking the survey before completing it. No more than 0.5% of English-speaking respondents across all experimental conditions opted to stop participating at or after the sex and gender questions.

The revised questions also did not appear to be affecting the Center’s credibility as a nonpartisan research organization. When asked whether respondents thought the survey was politically neutral, about three-in-four English speakers said the survey was not at all or not very biased, regardless of which gender questions they received.

The new gender question worked in Spanish, too

A small proportion of Spanish-speaking respondents (3.6%) opted for the third gender choice or chose a gender inconsistent with their sex. While this was significantly higher than the estimate among English speakers (1.5%), both English and Spanish speakers were asked to confirm their choice if sex and gender responses did not match. Spanish speakers consistently confirmed their answers to both sex and gender. Moreover, when asked if they found any questions confusing, only six Spanish speakers mentioned the gender question wording, and none of the six were coded as transgender.

Similar to English-speaking respondents, Spanish speakers did not seem to be affected by the various question wordings. And the addition of a third option had no perceivable alienation effect. Some 40% of Spanish speakers said they disapproved of the addition of a third gender choice on forms, but the addition of a third response category to the gender question did not cause more people to stop participating in the survey prematurely, nor did it affect the proportion of Spanish-speakers who perceived the survey as somewhat or very biased.

Asking about sex in addition to gender wasn’t necessary

While our experiment used a two-step question to deduce both a respondent’s sex and gender, moving forward, we will limit most of the Center’s U.S. surveys to the single gender question referenced at the top of this post.

Based on comments collected at the end of our experiment, fewer than 1% of respondents mentioned the sex and gender questions in any way. Among those who did, 30% expressed frustration over the presence of multiple questions or concern about the use of the term “born” in the question on sex. Also, the inclusion of a question about respondent’s sex isn’t necessary for most of the Center’s research, which focuses predominantly on gender. And while we do construct weights based on population estimates by sex, the correlation between gender and sex suggests that gender can reliably be used as a proxy for sex for this purpose. Another important consideration is respondents’ time: If we don’t need to ask a question, we won’t.

In conclusion, this change in how we ask about gender was not taken lightly, as we were driven to ensure inclusivity and accuracy while maintaining the rigorousness and neutrality that characterizes the Center.

Categories:

- Survey Methods

More from Decoded

Who are you the art and science of measuring identity.

As a shop that studies human behavior through surveys and other social scientific techniques, we have a good line of sight into the contradictory nature of human preferences. Here’s a look at how we categorize our survey participants in ways that enhance our understanding of how people think and behave.

How Pew Research Center will report on generations moving forward

When we have the data to study groups of similarly aged people over time, we won’t always default to using the standard generational definitions and labels, like Gen Z, Millennials or Baby Boomers.

5 things to keep in mind when you hear about Gen Z, Millennials, Boomers and other generations

It can be useful to talk about generations, but generational categories are not scientifically defined and labels can lead to stereotypes and oversimplification.

How a coding error provided a rare glimpse into Latino identity among Brazilians in the U.S.

An error in how the Census Bureau processed data from a national survey provided a rare window into how Brazilians living in the U.S. view their identity.

Why the U.S. census doesn’t ask Americans about their religion

The Census Bureau has collected data on Americans’ income, race, ethnicity, housing and other things, but it has never directly asked about their religion.

MORe from decoded

Measuring partisanship in europe: how online survey questions compare with phone polls, reproducibility as part of code quality control, redacting identifying information with computational methods in large text data.

To browse all of Pew Research Center findings and data by topic, visit pewresearch.org

About Decoded

This is a blog about research methods and behind-the-scenes technical matters at Pew Research Center. To get our latest findings, visit pewresearch.org .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Not a member?

Find out what The Global Health Network can do for you. Register now.

Member Sites A network of members around the world. Join now.

- 1000 Challenge

- ODIN Wastewater Surveillance Project

- CEPI Technical Resources

- Global Health Research Management

- UK Overseas Territories Public Health Network

- Global Malaria Research

- Global Outbreaks Research

- Sub-Saharan Congenital Anomalies Network

- Global Pathogen Variants

- Global Health Data Science

- AI for Global Health Research

- MRC Clinical Trials Unit at UCL

- Virtual Biorepository

- Epidemic Preparedness Innovations

- Rapid Support Team

- The Global Health Network Africa

- The Global Health Network Asia

- The Global Health Network LAC

- Global Health Bioethics

- Global Pandemic Planning

- EPIDEMIC ETHICS

- Global Vector Hub

- Global Health Economics

- LactaHub – Breastfeeding Knowledge

- Global Birth Defects

- Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR)

- Human Infection Studies

- EDCTP Knowledge Hub

- CHAIN Network

- Brain Infections Global

- Research Capacity Network

- Global Research Nurses

- ZIKAlliance

- TDR Fellows

- Global Health Coordinators

- Global Health Laboratories

- Global Health Methodology Research

- Global Health Social Science

- Global Health Trials

- Zika Infection

- Global Musculoskeletal

- Global Pharmacovigilance

- Global Pregnancy CoLab

- INTERGROWTH-21ˢᵗ

- East African Consortium for Clinical Research

- Women in Global Health Research

- Coronavirus

Research Tools Resources designed to help you.

- Site Finder

- Process Map

- Global Health Training Centre

- Resources Gateway

- Global Health Research Process Map

- Social Sciences Sessions

Session 11: Using Gender Analysis within Qualitative Research

Gender analysis entails researchers seeking to understand gender power relations and norms and their implications, including the nature of women’s, men’s, and people of other gender’s lives, how their needs and experiences differ, the causes and consequences of these differences, and how services and polices might address these differences. As well as analysing differences between females, males, and people of other genders, gender analysis, by focusing on the nature of power relations, also considers differences among females, among males, and among people of other genders. It includes examining gender in relation to other social stratifiers, such as class, race, education, ethnicity, age, geographic location, (dis)ability, and sexuality, ideally from an intersectional perspective.

Incorporating gender analysis into research should ideally be done at all stages of the research process. It includes considering gender when defining research aims, objectives, or questions; within the development of study designs and data collection tools; during the process of data collection; and in the interpretation and dissemination of results. By including gender into research, researchers can ensure that gender inequities are not perpetuated, collect higher quality and more accurate data, and actively engage in positively changing gender relations and reducing inequities.

Overall, by the end of the session users should be able to:

- Understand what gender analysis is and why it is important for global health research

- Recognize different ways gender analysis can be incorporated into your health systems research, including research content, process, and outcomes

- Understand how gender frameworks can be used to guide analytical process

You can download the powerpoint here .

The information above is taken from the following resource: Morgan, R. et al., 2016. How to do (or not to do)… gender analysis in health systems research. Health Policy and Planning, p.czw037.

Recommended Resources Gender Analysis Hunt, J. (2004). Introduction to gender analysis concepts and steps . Development Bulletin, 64, 100–106. JHPIEGO. (2016). Gender Analysis Toolkit for Health Systems . LSTM. (1996). Guidelines for the analysis of Gender and Health . Morgan, R. et al., (2016). How to do (or not to do)… gender analysis in health systems research . Health Policy and Planning, 31: 1069–1078. RinGs (2016). How to do gender analysis in health systems research: a guide RinGs (2015) How to do gender analysis in health systems research webinar recording

Gender Frameworks Caro, D. (2009). A Manual for Integrating Gender Into Reproductive Health and HIV Programs. JHPIEGO. (2016). Gender Analysis Toolkit for Health Systems . March, C., Smyth, I., & Mukhopadhyay, M. (1999). A Guide to Gender-Analysis Frameworks . Oxfam. RinGs (2015) Ten Gender Analysis Frameworks & Tools to Aid with Health Systems Research Warren, H. (2007). Using gender-analysis frameworks: theoretical and practical reflections. Gender & Development , 15(2), 187–198.

Intersectionality Bowleg, L. (2012). The problem with the phrase women and minorities: Intersectionality-an important theoretical framework for public health . American Journal of Public Health, 102(7), 1267–1273. Hankivsky, O. (2014). Intersectionality 101 . The Institute for Intersectionality Research & Policy, SFU. Larson, E., George, A., Morgan, R., & Poteat, T. (2016). 10 Best resources on... intersectionality with an emphasis on low- and middle-income countries . Health Policy Plan., czw020–. http://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czw020

We want these sessions to be useful and respond to users needs, so please contact us if you would like to see additional materials. We also have a dedicated page for users to share any thoughts or experiences of using these research approaches. You can also use these pages to ask questions or seek clarification. Click here for discussions.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 22 October 2022

The impact of gender diversity on scientific research teams: a need to broaden and accelerate future research

- Hannah B. Love ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0011-1328 1 , 2 ,

- Alyssa Stephens 2 , 3 ,

- Bailey K. Fosdick ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3736-2219 2 ,

- Elizabeth Tofany 2 &

- Ellen R. Fisher ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6828-8600 1 , 2 , 4

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 9 , Article number: 386 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

7853 Accesses

8 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Business and management

- Complex networks

- Science, technology and society

Multiple studies from the literature suggest that a high proportion of women on scientific teams contributes to successful team collaboration, but how the proportion of women impacts team success and why this is the case, is not well understood. One perspective suggests that having a high proportion of women matters because women tend to have greater social sensitivity and promote even turn-taking in meetings. Other studies have found women are more likely to collaborate and are more democratic. Both explanations suggest that women team members fundamentally change team functioning through the way they interact. Yet, most previous studies of gender on scientific teams have relied heavily on bibliometric data, which focuses on the prevalence of women team members rather than how they act and interact throughout the scientific process. In this study, we explore gender diversity in scientific teams using various types of relational data to investigate how women impact team interactions. This study focuses on 12 interdisciplinary university scientific teams that were part of an institutional team science program from 2015 to 2020 aimed at cultivating, integrating, and translating scientific expertise. The program included multiple forms of evaluation, including participant observation, focus groups, interviews, and surveys at multiple time points. Using social network analysis, this article tested five hypotheses about the role of women on university-based scientific teams. The hypotheses were based on three premises previously established in the literature. Our analyses revealed that only one of the five hypotheses regarding gender roles on teams was supported by our data. These findings suggest that scientific teams may create ingroups , when an underrepresented identity is included instead of excluded in the outgroup , for women in academia. This finding does not align with the current paradigm and the research on the impact of gender diversity on teams. Future research to determine if high-functioning scientific teams disrupt rather than reproduce existing hierarchies and gendered patterns of interactions could create an opportunity to accelerate the advancement of knowledge while promoting a just and equitable culture and profession.

Similar content being viewed by others

Towards understanding the characteristics of successful and unsuccessful collaborations: a case-based team science study

Interpersonal relationships drive successful team science: an exemplary case-based study

The achievement of gender parity in a large astrophysics research centre

Introduction.

Diversity in scientific teams is often a catalyst for creativity and innovation (Misra et al., 2017 ; Smith-Doerr et al., 2017 ), and numerous studies have documented that gender diversity, the equitable representation of genders, is important for the development, process, and outcomes of scientific teams (Bear and Woolley, 2011 ; Hall et al., 2018 ; Misra et al., 2017 ; Riedl et al., 2021 ; Smith-Doerr et al., 2017 ; Woolley et al., 2010 ). Furthermore, research has found evidence that a higher proportion of women on a team increases collective intelligence (Riedl et al., 2021 ; Woolley et al., 2010 ), and that gender-balanced teams lead to the best outcomes for group process (Bear and Woolley, 2011 ; Carli, 2001 ; Taps and Martin, 1990 ). When scientists hear that the proportion of women influences team performance, they often ask “What proportion is needed, and why does the proportion of women impact team success?”

The answers to these questions remain unclear. To date, most research on the impact of gender composition on scientific teams only uses quantitative metrics (e.g., comparing team rosters and bibliometric data) (Badar et al., 2013 ; Lee, 2005 ; Lerback et al., 2020 ; Pezzoni et al., 2016 ; Wagner, 2016 ; Zeng et al., 2016 ). Although these quantitative metrics provide a reasonable starting point, they emphasize the presence of women rather than their levels of integration or participation, which may perpetuate tokenism on scientific teams. As Smith-Doerr et al. ( 2017 ), reported

Our journey through the literature demonstrated a critical difference between diversity as the simple presence of women and minority scientists on teams and in workplaces, and their full integration (p. 140).

Similarly, Bear and Woolley ( 2011 ) conducted a meta-analysis of the literature from multiple disciplines and found that when diverse team members were integrated holistically, team diversity contributed to innovation. Conversely, in studies where teams had diverse membership but failed, these teams were often relying on token members and did not have authentic and full integration of those diverse members. Bear and Woolley ( 2011 ) suggest that the proportion of women on a team roster should be studied as follows:

It is not enough to simply examine the number of women in a particular institution or role. … In order to be truly effective, the role that women play in scientific teams should also be taken into consideration and promoted in order to yield the substantial benefits of increased gender diversity (p. 151).

These recent studies signal a paradigm shift in literature in the perceptions of diversity on teams because historically, diversity on teams was perceived as negative. In 1997, Baugh and Graen ( 1997 ) described teams with women and minorities were perceived to be less effective. Benschop and Doorewaard ( 1998 ) described how teams simply (re)produce gender inequality and they did not see a future in teams providing opportunities for women. Guimerà et al. ( 2005 ) claimed that while diversity may potentially spur creativity, it typically promotes conflict and miscommunication. Today, it is well accepted in the literature that to create new knowledge and solve complex global problems, studies in the science of team science (SciTS), knowledge innovation, creative, and more have documented that diversity in teams is important for the process, interactions, and outcomes (Bear and Woolley, 2011 ; Hall et al., 2018 ; Misra et al., 2017 ; Riedl et al., 2021 ; Soler-Gallart, 2017 ; Ulibarri et al., 2019 ; Woolley et al., 2010 ).

Numerous researchers have called for varied approaches to the study of women on teams. Madlock-Brown and Eichmann ( 2016 ) wrote that we “need a multi-pronged approach to deal with the persisting gender gap issues” (p. 654). Bozeman et al. ( 2013 ), explained that we understand collaboration from a bibliometric standpoint, but much more qualitative research is needed about the meaning of collaboration and the more informal side of collaboration, including mentoring, ingrained biases, and balancing collaborations (Reardon, 2022 ). Further, many of these studies about women on teams were conducted with undergraduate students within curricular settings, not with real-world scientific teams. Fundamentally, to understand gender patterns in scientific collaborations, qualitative and mixed methods research approaches are needed that study the process of scientific team development and not just team outcomes (Keyton et al., 2008 ; Wooten et al., 2014 ).

This study focused on 12 interdisciplinary university scientific teams that were part of an institutional team science program from 2015 to 2020 aimed at cultivating, integrating, and translating scientific expertise. Team science is research conducted collaboratively by small teams or larger groups (Cooke and Hilton, 2015 ). The program included multiple forms of evaluation, including participant observation, focus groups, interviews, and surveys at multiple time points. More specifically, gender diversity was explored by using mixed-methods data from team interactions to investigate two primary research questions: (1) what is the role of women on scientific teams? and (2) how do women impact team interactions?

Members of the 12 teams completed social network surveys about their relationships including who they seek advice from, who is a mentor, who serves on student committees, who they learn from, and who they collaborate with. Social network analysis studies the behavior of the individual at the micro level, the pattern of relationships (network structure) at the macro level, and the interactions between the two (Stokman, 2001 ). In the context of team science, social network analysis provides insights into how interactions are related to team success and how the social processes teams use supports the knowledge-creation process (Cravens et al., 2022 ; Giuffre, 2013 ; Granovetter, 1977 ; Love et al., 2021 ; Zhang et al., 2020 ). Utilizing these data, we calculated the indegree for each team member’s relationship with other team members. Indegree quantifies the number of other team members that stated they had the selected relationship with the given individual. For example, the advice indegree counts the number of other team members that reported receiving advice from that person. To compare results across the teams, the indegree and outdegree measures were scaled by the number of respondents to account for the total number of possible connections for individuals. These social network measures allowed us to test five hypotheses based on the current team science literature and other disciplines about how women impact team interaction and collaboration.

Hypothesis 1 : Women faculty will have a higher indegree than men faculty within the mentoring and student committee networks. Men faculty members will have a higher indegree than Women faculty members in the advice and leadership networks.

Hypothesis 2 : Men at all career stages will be more likely to be considered a leader on the team than women, measured by having a higher average scaled indegree in the leadership network.

Hypothesis 3 : Various networks will be correlated as follows:

Leadership and advice networks will be positively correlated.

Mentoring networks will not be positively correlated with leadership or advice networks.

Mentoring and student committees will be correlated.

Hypothesis 4 : The social and collaboration relations will be more positively correlated for women than for men.

Hypothesis 5 : Non-faculty team members will have more social connections on teams with a senior woman relative to those on teams without a senior woman.

These hypotheses are grounded in the literature on the persistent, latent, and subtle ways gender inequality is reproduced within organizations (Acker, 1992 ; Benschop and Doorewaard, 1998 ; Cole, 2004 ; Fraser, 1989 ; Gaughan and Bozeman, 2016 ; Madlock-Brown and Eichmann, 2016 ; Sprague and Smith, 1989 ). Many theories regarding the impact of gender diversity assume that teams reproduce socialized patterns of behavior. Zimmerman and West ( 1987 ) wrote that gender is not a biological concept, but it is a social construction that “involves a complex of socially guided perceptual, interactional, and micropolitical activities that cast particular pursuits as expressions of masculine and feminine ‘natures’” (West and Zimmerman, 1987 ). Gender is thus created by social organization and performed in our everyday lives and the ways we interact with one another (Butler, 1988 ). Gender, albeit a social construct, is an influential schema that impacts behaviors and interactions in society (West and Zimmerman, 1987 ).

According to Zimmerman and West ( 1987 ) and Butler ( 1988 ), the process of gender socialization includes ideas about who is a leader, how leaders should act, and even what leaders should look like. Many studies have found that women may not be perceived as leaders even when their status or contributions to the team are high (Bunderson, 2003 ; DiTomaso et al., 2007 ; Humbert & Guenther, 2017 ; Joshi, 2014 ). Other studies have found that men were more influential in groups, even when they were in the minority (Craig and Sherif, 1986 ), and that teams with women and minorities were perceived to be less effective (Baugh and Graen, 1997 ). Furthermore, although leadership responsibilities often become attached to specific roles, they can also be conferred and performed based on the perception of the individual qualities or capabilities of team members (Butler, 1988 ). For example, if a woman is a principal investigator (PI), a man on the team may also be considered a leader and vice-versa. These conferred roles may impact individual responsibilities and further solidify the perception of who is the team leader .

Perceptions about the roles of women and men can also impact the responsibilities they are assigned during meetings and the duties they are expected to perform in the workplace. In academia, faculty are frequently expected to engage in service work to support the university, the discipline, and the community. Service work may include mentoring, advising, and serving on committees. Recent studies suggest what has been long perceived within academia, that when controlling for rank, race/ethnicity, and discipline, women spend significantly more hours on service work when compared to their male colleagues, (Guarino and Borden, 2017 ; Misra et al., 2011 ; Urry, 2015 ). In STEM disciplines, women spend a higher percentage of their time on mentoring than their male counterparts (21% for women vs. 15% for men) (Misra et al., 2011 ). Researchers have not yet explored whether team science exacerbates or mitigates this disparity in service work.

Literature has documented that collaboration patterns are different for women and men. Women faculty and students participate in more interdisciplinary research in almost all fields at every career stage (Rhoten and Pfirman, 2007 ). In addition, women tend to have more collaborators than men (Bozeman and Gaughan, 2011 ), and studies have found that being well-connected correlates with success for women (Madlock-Brown and Eichmann, 2016 ). Is it possible that having a senior woman on the team creates a culture of collaboration, such that non-faculty, which might be traditionally marginalized on a team, are more well-connected? We evaluate this here by comparing the connectedness of non-faculty on teams with and without a senior woman.

In part, the lack of understanding about why gender diversity matters on scientific teams result from primarily studying member demographic profiles rather than studying how teams are functioning, including exchanges of knowledge, power dynamics, and the team development process which is critical to team success (Smith-Doerr et al., 2017 ). This study moves beyond team composition to expand and examine real-world scientific teams through analysis of relational data to answer the questions: What is the role of women on scientific teams; and How do women impact team interactions?

This study was conducted at a land grant, R1 University in the western region of the United States. The primary sample for this study was 12 self-formed, interdisciplinary scientific teams with varied research foci, who were participants in a competitive university-funded team science program from 2015 to 2020. To apply for funding, each team submitted a written application and competed in a pitch fest (a brief oral presentation of their proposed project) that was followed by an intensive question and answer session by the review team. The topics for the interdisciplinary teams that were selected were broadly defined across STEM-related fields. The teams were expected to contribute to high-level program goals, which included:

Increase university interest in multi-dimensional, systems-based problems

Leverage the strengths and expertise of a range of disciplines and fields

Shift the funding landscape towards investing in team science/collaborative endeavors

Develop large-scale proposals; high caliber research and scholarly outputs; new, productive, and impactful collaborations

These overarching goals were measured by having the teams report on a variety of outcome metrics, including publications, proposals submitted, and awards received.

Participation in the team science program occurred through two cohorts and lasted 24–30 months for each cohort. However, a team in the second cohort left the program after 12 months. During the program, teams met with administrative leadership, the team science research team, and some external partners every 3–4 months to provide progress updates on stated milestones and receive feedback and mentorship. Additional support was provided through individualized trainings/workshops approximately every few months throughout the program. These sessions provided additional instruction on team science principles, social network analysis interpretation, marketing/branding, diversity and inclusion, opportunity identification, philanthropic fundraising, technology transfer, visioning, and team management/leadership. Some of the training was attended by multiple teams, but often these were specifically designed for the needs and developmental stage of each team. An additional team volunteered to participate in the study but was not part of the formal program. This team, also self-formed, was an interdisciplinary team that had received a large award through a federal grant. The 13 teams were randomly assigned a number from 1 to 13 to maintain anonymity and are referred to in this study by their team number. Team 2 was excluded from the study altogether because two of the authors were members of this team.

Data collection

Multiple types of evaluation data, at multiple points in time, were collected throughout the university-based team science program including participant observation, focus groups, turn-taking data, rosters, interviews, and surveys. This study utilized the resulting data from rosters, participant observation, field notes, and responses to a social network survey. Data for this article is from social network surveys at the conclusion of the program or the closest associated data point. Selecting data from a similar timepoint follows the recommendations of Wooten et al. ( 2014 ) who differentiated between development, process, and outcome metrics for scientific teams.

Teams submitted rosters with demographic information including name, email, self-identified gender, title, college, department, and role on the team (i.e., PI, member, graduate students, etc.). Rosters were updated annually during the program and provided the data to define senior woman and junior faculty and other demographic categories.

Social network survey

Each team member on the roster was sent an email after the program end date and was asked to complete an online social network survey that had two sections: demographic and social network relational questions (see Appendix Table 2 ). Following IRB protocol #19-8622H, participation was voluntary, and all subjects were identified by name on the social network survey to allow for the complete construction of social networks. Names were deleted prior to data analysis and result reporting.

To ensure that respondents had the option to select a self-identified gender, the social network survey included a demographic question that asked participants to self-identify their gender by filling in a blank space rather than choosing from a prescribed drop-down list. This was the gender attribute used for analysis in this article. Two respondents did not answer the gender demographic survey question, and the roster data was used for these participants. There was no variability in the level of missingness across questions. Respondents either completed the survey or did not.

The network survey’s relational questions asked about the presence and absence of interactional mentoring, advice, leadership, and collaborative relationships with other members of the team. The first set of questions was developed by the research team primarily to collect information about scientific collaborations since joining the team. The survey asked, who have you:

talked about possible joint research/ideas/concepts/connections

worked on research, collaborations, tech projects, or consulting projects

worked on joint publications presentations, or conference proceeding

worked on or submitted a grant proposal; and sat on a student’s committee together (or is a member of your thesis/dissertation committee)

The second set of questions focused on social relationships within the team, including:

I learn from [ this person ]

I seek advice from [ this person ]

I hang out with [ this person ] for fun

[ this person ] is a leader on the team

[ this person ] is a mentor to me

[ this person ] is a friend

[ this person ] energizes me

Participant observation and field notes

A researcher attended two to six team meetings for each team to collect observational data. There were two exceptions to this as Team 1 did not have face-to-face team meetings, precluding participant observation; and Team 5 did not consent to observation at their meetings. After the meetings, the researcher recorded field notes to provide qualitative insights into the progress of the team development, their patterns of collaboration, and gender interactions as suggested by Marvasti ( 2004 ). The field notes supported the development of the senior women classification (see Appendix Table 1 for classification definitions). In addition to roster information, many teams had separate leadership teams that met and determined the scientific direction of the team. If a team had a woman on the leadership team, as recorded in field notes, then they received the designation of having a senior woman .

Statistical analysis

RStudio (R Studio Team, 2020 ) was used to analyze the social network data. The data were summarized using outdegree, indegree, and average degree. The outdegree of an individual is a measure of how many other team members they indicated receiving advice, mentorship, etc. from on the team. Alternatively, the indegree of an individual is a measure of how many other team members reported receiving advice, or mentorship, from that person. Average degree is the average number of immediate connections (i.e., indegree plus outdegree) for a person in a network (Giuffre, 2013 ; Hanneman and Riddle, 2005 ). To compare results across the teams, the indegree and outdegree measures were scaled by the number of respondents to account for the total number of possible connections for individuals (which is a function of both team size and response rate). The scaled indegree is thus the proportion of the team that named that team member for a given category. For example, if a team member has a scaled mentor indegree of 0.10, then 10% of the responding team members consider this individual to be a mentor. Confidence intervals for scaled indegrees were calculated using a t -distribution due to limited sample size.

The social relation question set responses were also analyzed separately and then combined for further statistical analysis. Three measures were created: collaboration, social, and professional support. To create the measure called collaboration , the following questions were combined: worked on research, collaborations, tech projects, or consulting projects; worked on joint publications presentations, or conference proceedings; worked on or submitted a grant proposal. To create the measure called social , the measures: I hang out with [this person] for fun and [this person] is a friend were combined. Finally, to create the measure called professional support , the measures: I seek advice from [this person], [this person] is a mentor to me, and sat on a student’s committee together (or is a member of your thesis/dissertation committee) were combined (see Appendix Table 2 for Terms and Associated Survey Questions).

In addition, data from the social network relational questions were used to construct multiple social network diagrams, wherein nodes represent the team members, and an edge exists from participant A to participant B if A perceived a relation with B. For example, in the mentorship network, a link from A to B signified that A considered B to be a mentor.

Field notes were analyzed using a constant comparative method (Mathison, 2013 ) to provide qualitative insights into the progress of overall and individual team development, patterns of collaboration, and gender interactions as suggested by Marvasti ( 2004 ).

Classifications

For analysis purposes, three classifications were created from the demographic data. Senior woman indicates there was a woman PI or a woman on the leadership team. Faculty was defined as an assistant, associate, and full professor. Non-faculty were defined as undergraduate students, graduate students, postdocs, research associates, community partners, and project managers. In the study, 78.5% of faculty, and 77.6% of non-faculty completed the survey (see Appendix Fig. 1 for more details on response rate and Appendix Table 1 for terms and definitions).

Demographic data

Over half of the 204 team members, 160 (78.2%), completed the survey. Out of 160 respondents, 84% of women and 73% of men completed the survey. Table 1 provides demographic data by team number. Team size ranged from a low of 6 and a high of 30 members and the average number of team members was 15. The university had seven colleges, and all teams had representation from three to seven colleges.

Hypotheses testing

Test results of the five study hypotheses are presented below.

Hypothesis 1 : Women faculty will have a higher indegree than men faculty within the mentoring and student committee networks, and men faculty members will have a higher indegree than women faculty members in the advice and leadership networks.

The first hypothesis was designed to investigate if women were perceived to be doing more service work and emotional labor (mentoring and student committee networks), and men were perceived as being leaders (leader and advice networks) (Guarino and Borden, 2017 ; Misra et al., 2011 ; Urry, 2015 ).

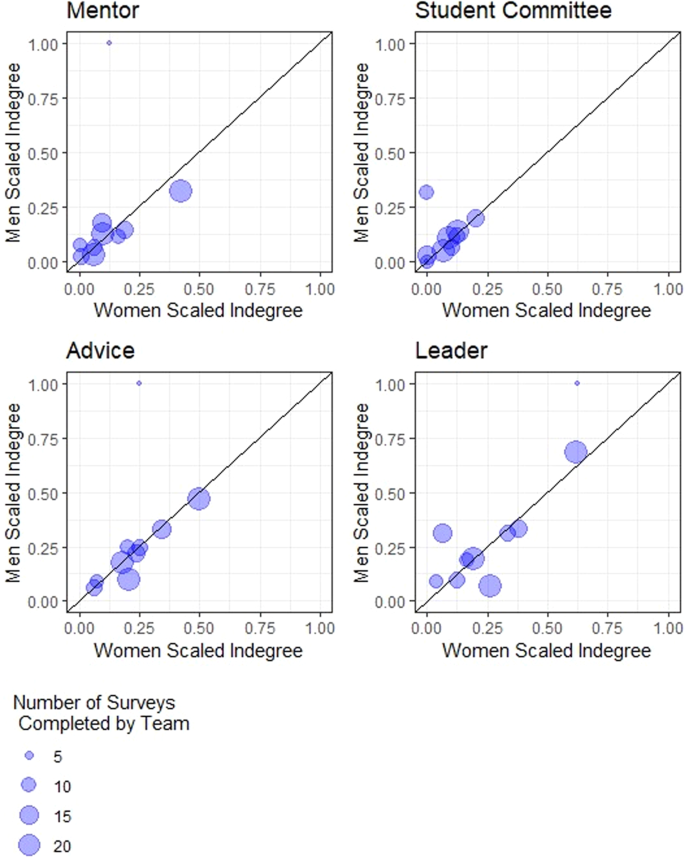

Figure 1 compares the average indegree values of men and women on each team in four social network diagrams (mentoring, student committees, leader, and advice). The data in Fig. 1 do not support the hypothesis that more team members went to women faculty for mentoring and for serving on student committees. Further, the data did not support that more team members went to men faculty for advice or reported viewing them as leaders.

These are plotted against one another, where the size of the dot reflects the number of team members that completed the survey. When the number of respondents is low (a small dot), the scaled indegree is expected to be more variable, whereas when the number of respondents is high (a large dot), the scaled indegree is expected to be less variable and more representative of the whole team’s perceptions. Each graph reports a different social network question (mentor, student committee, advice, and leader).

The Fig. 1 mentoring network does, however, illustrate that teams in the study either engaged or did not engage in mentoring. On teams where women had a high mentoring indegree, men also had a high indegree in the mentoring network. This indicates that mentoring was team-specific rather than gender-specific. This aligns with other studies about team processes that found team norms (like mentoring) impact the behaviors and processes of teams (Duhigg, 2016 ; Winter et al., 2012 ).

Hypothesis 2 : Men at all career stages are more likely to be considered a leader on the team than women, measured by having a higher average scaled indegree in the leadership network (Table 2 ).

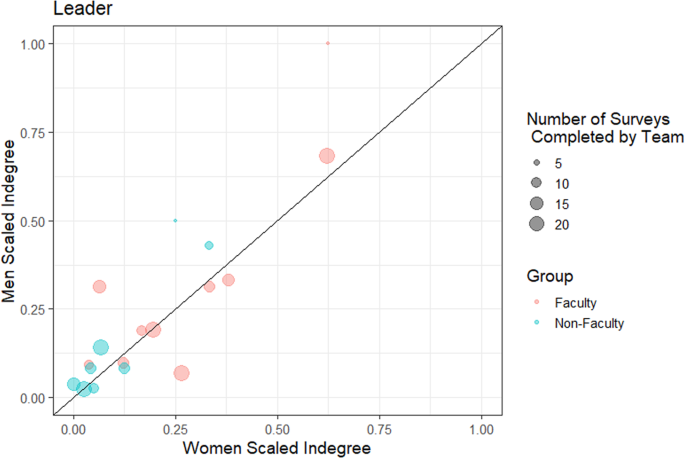

Literature in business, political science, and sociology report that men are more likely to be perceived as leaders (Baugh and Graen, 1997 ; Bunderson, 2003 ; Craig and Sherif, 1986 ; DiTomaso et al., 2007 ; Humbert and Guenther, 2017 ; Joshi, 2014 ). Based on this, we hypothesized that these perceptions would also be present in scientific teams (Table 2 , Fig. 2 ). In the study, both men faculty and men non-faculty were more likely to be reported as a leader on the team; however, this finding was not statistically significant based on a 95% confidence interval (CI) (Table 2 ).

The values for men and women for each of the faculty types are plotted against one another. Faculty were more likely to be considered leaders than non-faculty, but there were no significant differences between reporting men or women as leaders on scientific teams.

Figure 2 illustrates the scaled indegree for women and men faculty and non-faculty, which shows faculty are more likely to be considered leaders than non-faculty. Nevertheless, there were no significant differences in whether team members reported men or women as leaders on scientific teams.

Hypothesis 3 : Based on socialized gendered perceptions various networks will be correlated as follows:

The third hypothesis focused on whether gendered perceptions resulted in certain network diagrams being correlated. Previous studies have found that men are more likely to be perceived as leaders (Baugh and Graen, 1997 ; Bunderson, 2003 ; Butler, 1988 ; Craig and Sherif, 1986 ; DiTomaso et al., 2007 ; Humbert and Guenther, 2017 ; Joshi, 2014 ) and women are more likely to be perceived as mentors or caretakers (Guarino and Borden, 2017 ; Misra et al., 2011 ; Urry, 2015 ). These perceptions are sedimented in the language used to describe men and women (Sprague and Massoni, 2005 ).

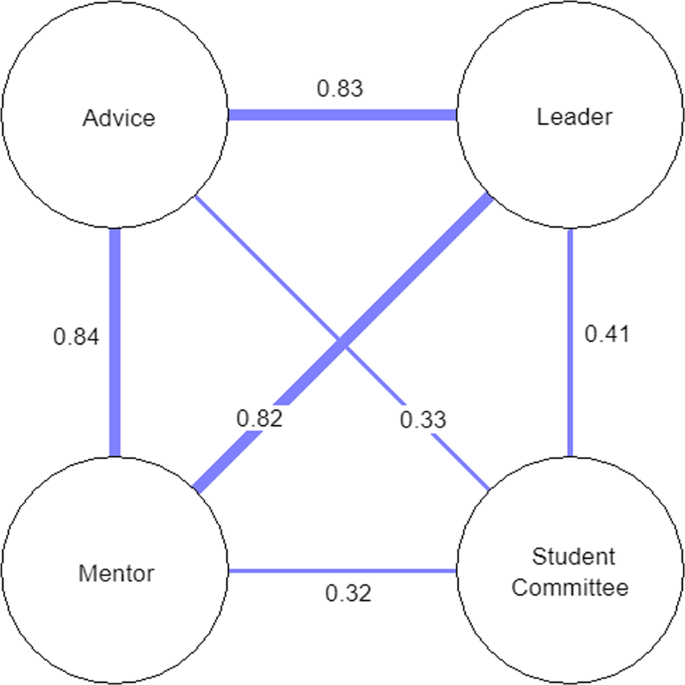

We see the advice, leader, and mentor networks were highly correlated but only weakly correlated with the student committee network.

Based on this literature, we hypothesized that the leadership and advice networks would be correlated because both leading and giving advice suggest a greater power differential. Second, the mentoring network would not be correlated with leadership or advice networks because mentoring is more closely aligned with caregiving activities, which are considered more feminine. Third, the mentor and student committee networks would be correlated because these acts are associated with caretaking. Here, we tested if the networks related to leadership were correlated and if networks related to mentorship and service work such as serving on student committees were correlated.

Figure 3 illustrates the correlations for four of the network diagrams (mentoring, student committee, advice, and leadership) and reports the significance. The first gendered perception, that the leadership and advice networks would be correlated, was validated by the data. In the study, the leadership and advice networks were correlated (0.83). However, the hypothesis that the mentoring network would not be correlated with leadership (0.82) and advice (0.84) was not supported. These network diagrams were correlated, indicating team members who reported other team members as being leaders also reported that they received advice and mentoring from them. Finally, the hypothesis that mentoring and student committee diagrams would be correlated was also not validated by the data (0.32). One factor that could be contributing to these results comes from studies that show perceived organizational support, as well as perceived leader support, correlate with creativity and satisfaction in the workplace (Handley et al., 2015 ; Moss-Racusin et al., 2012 ; Smith et al., 2015 ). On the teams, members that are perceived as leaders are likely to provide support to others on the team. Notably, these studies did not explicitly examine gender in their findings.

A growing body of literature seeks to understand the connection between interpersonal relationships and knowledge innovation (Reference Blinded). We investigate this by considering how three types of interactions collaborative, social, and professional are intertwined on scientific teams. The purpose of this hypothesis was to closely examine the collaboration patterns of men and women and the connection between interpersonal relationships and knowledge creation. To create the measures in this hypothesis, social network survey questions were combined. For example, the measure social is a combination of: I hang out with [this person] for fun and [this person] is a friend (see the Analysis section for descriptions of all the measures).

To test what proportion of team members collaborate, given that they are also social with these individuals, we identified the team members that the person was social with and then calculated what proportion of those members they were also collaborating with. The results for this measure are given in Table 3 as proportion collaboration given social . Other items in Table 3 were developed in a similar manner.

Although our results indicate no statistical differences between men and women, we found that both men and women have intertwined relationships. If a team member is in one network (e.g., collaboration), it is likely that the person is also in another one of their networks (e.g., social). Furthermore, the overall proportion of men who have intertwined relationships in their collaboration, social, and professional support networks were higher in all proportions except proportion social given professional support (Table 3 ).

Numerous studies have attempted to tease apart gendered approaches to different collaboration styles and whether this has any impact on scientific collaborations (Bozeman et al., 2013 ; Madlock-Brown and Eichmann, 2016 ; Misra et al., 2017 ; Zeng et al., 2016 ). To build on this body of literature, this hypothesis tests the impact of senior women’s leadership, if any, on the collaborations of senior women and their impact on the network.

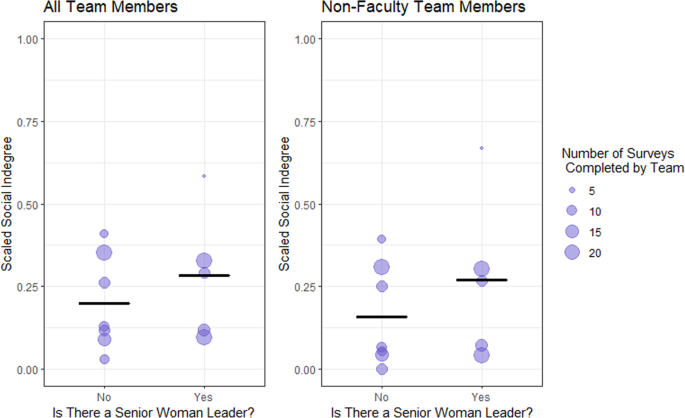

Figure 4 illustrates the scaled average indegree on the whole team when there are women in senior positions. A high average indegree for the team indicates that more team members and interacting and socializing on the team. The average scaled indegree on teams with a senior woman was 0.28 and without a senior woman was 0.20 ( t -test p = 0.44; Cohen’s D effect size 0.51). The second graph in Fig. 4 illustrates the scaled average indegree on non-faculty when there are women in a senior positions. The average scaled indegree on teams with a senior woman was 0.27 and without a senior woman was 0.16 ( t -test p = 0.42; Cohen’s D effect size 0.55). Thus, there was no evidence to conclude that senior women influenced the social interactions on the team.

These average scaled indegree measures were then separated based on whether there was a senior woman leader on the team, and the average across all teams was marked by a black horizontal bar. Based on these data, there appears to be no systematic difference in the social interactions of teams with a woman in a senior position and teams without a woman in a senior position. Average scaled indegree of non-faculty on teams without a senior woman = 0.16. Average scaled indegree of non-faculty on teams with a senior woman = 0.27. ( t -test) p -value = 0.42.

This study explored the impact of gender diversity on 12 scientific teams by analyzing team development and process data. It investigated two primary research questions: What is the role of women on scientific teams? and How do women impact team interactions? We initially believed that the primary reason previous research had been unable to adequately explain the role of women on scientific teams and how women impact team interactions were in part due to the lack of qualitative and mixed methods studies. We based our initial hypothesis on the assumption that scientific teams reproduce existing patterns of inequality (Butler, 1988 ; West and Zimmerman, 1987 ). However, it was through the development of the five hypotheses for this study and the subsequent analysis of relational data, that we learned that our assumption was in large part not supported.

Numerous studies have found evidence of systematic discrimination and bias in awarding grants (Ginther et al., 2011 ), acceptance of publications (Lerback et al., 2020 ; Salerno et al., 2019 ), language to describe women (Ross et al., 2017 ), promotion decisions (Régner et al., 2019 ), rewards (Mitchneck et al., 2016 ), and access to resources for research (Misra et al., 2017 ) in addition to other obstacles and forms of marginalization that are invisible and unacknowledged (Rhoten and Pfirman, 2007 ; Urry, 2015 ). Why did our data not replicate these findings? We conclude with the following possible explanations.

Preliminary studies in the SciTS literature have found that team science principles may simultaneously support the advancement of women in scientific fields; and complementarily, the inclusion of women on scientific teams may increase the success of these teams (McKean, 2016 ; Woolley et al., 2010 ). Further, including women and underrepresented populations on scientific teams has the potential to “serve as a strong entry point into scientific studies for women” (Rhoten and Pfirman, 2007 , p. 72). Similarly, in sociology, Soler-Gallart ( 2017 ) found positive benefits for the whole team when scientists engaged in dialogic relations and interaction with the intention of overcoming gender barriers and discrimination. Could team science advance women in their scientific careers? If high-functioning scientific teams disrupt rather than reproduce existing hierarchies and gendered patterns of interactions, it increases the possibility that team science is a tool not only for accelerating the creation of knowledge but for the advancement of a more empowered, just, and equitable profession.

Literature has documented how including historically underrepresented identities in the ingroup changes attitudes and behaviors (Soler-Gallart, 2017 ). Allport et al. ( 1954 ) found that when members of an ingroup were in close contact and built connections with members of an outgroup, prejudice decreased. Initially, the theory about ingroups and outgroups was devised to describe race and ethnic relations; however, recent studies have generalized the findings to other topics including gender bias and discrimination (Pettigrew and Tropp, 2006 ). Today, numerous studies have documented that intergroup contact and connections can improve intergroup attitudes (Allport et al., 1954 ; Brewer, 2007 ; Dovidio et al., 2012 ; Pettigrew and Tropp, 2006 ). Is it possible that scientific teams create ingroups that include rather than exclude women?

The teams in this study were not created nor did they develop in isolation. These teams had access to team development resources like SciTS literature, team science training, and access to administrative expertise and support. The promotion and tenure package of the selected university for this study allowed faculty to include interdisciplinary and team accomplishments. Structures were in place to fund, train, build, and reward these teams. Many of these resources, interventions and structures were designed and led by a group of nine women and one man. The women, especially, emphasized diversity, equity, and inclusion from team formation to building and rewarding successes. In addition, many of the sessions were customized to meet the needs of individual teams. Did these facilitators create an ingroup ? Although we did not test the impact of these interventions and structures, other studies have previously hypothesized that modifying existing and often outmoded structures will positively impact outcomes for women (Gibbons et al., 1994 ; Hansson, 1999 ; Rhoten and Pfirman, 2007 ). Another study found that when team members participate in dialog relations and interactions instead of using prestige to gain power they were more willing to rethink concepts when presented with new information (Soler-Gallart, 2017 ). Specifically, in terms of women in science, Rolison ( 2000 , 2004 ) developed a hypothesis recommending explicitly applying Title IX principles to support women in academia. She posited that providing equal funding opportunities and resources for women would result in equal opportunities for success. Another study attributed the key to their team’s success was the inclusion of women, the community, and other diverse perspectives from the community (Soler-Gallart, 2017 ). Our findings suggest that the handful of women on our teams may have joined the ingroup in academia albeit if only for a short time.

It is important to note that we do not believe our results accurately reflect the university of study as a whole or academia in general. Team observations and resulting field notes documented numerous accounts of gender inequality and inequity where women were disempowered and had limited opportunities to contribute to the team. Moreover, we are confident that women on these teams have had individual experiences that would contradict our findings. A lack of evidence does not indicate that there is equality. Nevertheless, these results do suggest that scientific teams, developed with intention, may provide greater opportunities for women to amplify their contributions to science (McKean, 2016 ; Rhoten and Pfirman, 2007 ; Woolley et al., 2010 ).

Limitations

Previous studies on gender and scientific teams have used bibliometric data to understand patterns of collaboration. Other studies on teams have created teams in the lab using students and other volunteers. Although this study is unique and contributes to the literature, as the data are based on real-world scientific teams, we identified six limitations.

First, several teams had apprehension about participating in SciTS research, and one team left the program after year one resulting in limited data from those teams. Second, teams may have experienced the so-called Hawthorne effect (K. Baxter et al., 2015 ) and performed differently because they were part of a research study, and a researcher regularly attended team meetings. All participant observations related to the positionality of the researcher were well-documented in field notes (P. Baxter and Jack, 2008 ; Greenwood, 1993 ; Marvasti, 2004 ).

Third, we defined senior women in a manner that would be inclusive to women with and without formal titles. The senior woman designation was given based on both formal titles and field notes. Some of the teams in our study had women who were the PI or in a designated leadership position with formal titles, and other teams had women on the leadership team. It is possible that the women on these teams were seen as leaders because of their position on the team, but that their leadership came without titles, awards, and recognition that might have been associated with those titles.

Fourth, it is possible that study participants had varying definitions of mentor , advice , and leader . We anticipated different interpretations in our study plan and as a result combined data in hypothesis four to detect and account for potential differences in definitions. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that lived experiences, in general, give individuals different perspectives. Literature in political science has found that when people imagine a leader , many of the traits are more masculine (e.g., wearing a suit, being tall and bigger) (Butler, 1988 ). Fifth, we did not measure the success of the teams in this study; thus, we were unable to translate how different interaction patterns translated into team performance. Ongoing funding was, however, contingent on performance as measured by pre-determined metrics including numbers of grants, publications, invention patents, and other markers of success.

Finally, a limitation of all social network studies is that data are collected at a single point in time. Thus, temporal changes in team interactions cannot be accounted for in our sample. For example, we cannot discern whether social relationships or scientific collaborations came first. We only know that they were both happening at the time the survey was administered. Further, at the time the survey was completed, it is possible that a person had not yet established a relationship, or they had forgotten about a previous relationship.

Conclusion, recommendations, and future research

We offer three key recommendations for future research. First, scientific results that are statistically insignificant are rarely shared in the literature. Therefore, it is critical that all efforts to expand research be published to broaden and accelerate the understanding of the role of women in scientific teams (Bammer et al., 2020 ; Oliver and Boaz, 2019 ).

Second, the landscape of science is changing rapidly as a result of private and federal funders requiring the inclusion of the science of team science experts as PIs in grant applications. We recommend that researchers expand their focus and examine how scientific teams change the culture of science. Research questions might include: How do support diverse teams translate to culture changes in science and the academy? Do scientific interdisciplinary teams provide more access for historically marginalized and disenfranchised groups? Finally, to create a comprehensive understanding of elements that contribute to expertise in scientific teams, we recommend that research be conducted with a theoretical focus on team development and processes. This would include studies that explore science facilitation, learning-by-doing, and other tacit forms of expertise that lead to integration and implementation of knowledge (rather than a focus on recruitment and demographics).

Third, existing studies define gender as a binary (man/woman). This short-sighted perspective is no longer relevant in society. Gender is not a biological concept, but a social construct, “It involves a complex of socially guided perceptual, interactional, and micropolitical activities that cast particular pursuits as expressions of masculine and feminine ‘natures.’” (West and Zimmerman, 1987 , p. 125). Gender is thus created by the social organization of our everyday lives and the way we interact with one another. People often see this difference as natural , and society is structured as a response to these differences in terms of men and women. Because of this, researchers like us continue to expend time and resources asking research questions rooted in binary gender. Future research should broaden definitions of diversity and gender including non-binary definitions of gender, expand how we measure inclusivity, explore how power imbalances block expertise, and study how a balance of power promotes expertise.

In conclusion, the lack of evidence for gender impacting team roles and behaviors in our study aligns with other SciTS studies that found team composition is not the silver bullet that automatically leads to knowledge creation and innovation (Duhigg, 2016 ; Oliver and Boaz, 2019 ). Numerous SciTS studies have documented the importance of processes over team composition and relationships to build successful teams (Boix Mansilla et al., 2016 ; Gaughan and Bozeman, 2016 ; Hall et al., 2018 ; Zhang et al., 2020 ). Perhaps the reason scientific teams produce more citations and have a greater impact than siloed investigators (Wuchty et al., 2007 ) is that they are leveraging the available expertise through the authentic integration of all members.

In the future, when scientists ask, “What proportion of women is ideal on a team?” consider responding with “It is not about the number of women, but rather how women on teams are integrated and empowered.”

Data availability

Data are available upon request to protect the privacy of our study participants. Parts of the larger data set have been made publicly available via the following links: https://doi.org/10.25675/10217/214187 and https://hdl.handle.net/10217/194364 .

Acker J (1992) Gendering organizational theory. Gendering Organ Anal 6(2):248–260. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124390004002002

Article Google Scholar

Allport G, Clark K, Pettigrew T (1954) The nature of prejudice. http://althaschool.org/_cache/files/7/1/71f96bdb-d4c3-4514-bae2-9bf809ba9edc/97F5FE75CF9A120E7DC108EB1B0FF5EC.holocaust-the-nature-of-prejudice.doc

Badar K, Hite JM, Badir YF (2013) Examining the relationship of co-authorship network centrality and gender on academic research performance: the case of chemistry researchers in Pakistan. Scientometrics 94(2):755–775. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-012-0764-z

Bammer G, O’Rourke M, O’Connell D, Neuhauser L, Midgley G, Klein JT, Grigg NJ, Gadlin H, Elsum IR, Bursztyn M, Fulton EA, Pohl C, Smithson M, Vilsmaier U, Bergmann M, Jaeger J, Merkx F, Vienni Baptista B, Burgman MA, … Richardson GP (2020) Expertise in research integration and implementation for tackling complex problems: when is it needed, where can it be found and how can it be strengthened? Palgrave Commun 6(1) https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0380-0

Baugh SG, Graen GB (1997) Effects of team gender and racial composition on perceptions of team performance in cross-functional teams. Group Organ Manag 22(3):366–383. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601197223004

Baxter K, Courage C, Caine K (2015) Understanding your users: a practical guide to user research methods. In: Understanding your users. Second edition. Morgan Kaufmann/Elsevier, Amsterdam

Baxter P, Jack S (2008) The qualitative report qualitative case study methodology: study design and implementation for novice researchers. Qual Reportual Rep 13(2):544–559. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol13/iss4/2

Google Scholar

Bear JB, Woolley AW (2011) The role of gender in team collaboration and performance. Interdiscip Sci Rev 36(2):146–153. https://doi.org/10.1179/030801811X13013181961473

Benschop Y, Doorewaard H (1998) Six of one and half a dozen of the other: the gender subtext of taylorism and team-based work. Gend Work Organ 5(1):5–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0432.00042

Boix Mansilla V, Lamont M, Sato K (2016) Shared cognitive emotional interactional platforms: markers and conditions for successful interdisciplinary collaborations. Sci Technol Hum Values 41(4):571–612. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243915614103

Bozeman B, Fay D, Slade CP (2013) Research collaboration in universities and academic entrepreneurship: the-state-of-the-art. J Technol Transf 38(1):1–67 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-012-9281-8

Bozeman B, Gaughan M (2011) How do men and women differ in research collaborations? An analysis of the collaborative motives and strategies of academic researchers. Res Policy 40(10):1393–1402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.07.002

Brewer MB (2007) The social psychology of intergroup relations: social categorization, ingroup bias and outgroup prejudice. In Kruglanski, AW & Higgins, ET (Eds.), Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles. The Guilford Press. pp. 695–715

Bunderson JS (2003) Recognizing and utilizing expertise in work groups: a status characteristics perspective. Adm Sci Q 48(4) https://doi.org/10.2307/3556637

Butler J (1988) Performative acts and gender constitution: an essay in phenomenology and feminist theory. Theatr J 40(4):519. https://doi.org/10.2307/3207893

Carli L (2001) Gender and social influence. J Soc Issues 57(4):725–741. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00238

Cole S (2004) Merton’s contribution to the sociology of science. Soc Stud Sci 34(6):829–844. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312704048600

Cooke NJ, Hilton ML (2015) Enhancing the effectiveness of team science. National Academies Press

Craig JM, Sherif CW (1986) The effectiveness of men and women in problem-solving groups as a function of group gender composition. Sex Roles 14(7–8):453–466. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00288427

Cravens AE, Jones MS, Ngai C, Zarestky J, Love HB (2022) Science facilitation: navigating the intersection of intellectual and interpersonal expertise in scientific collaboration Humanit Soc Sci Commun 9(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01217-1

DiTomaso N, Post C, Smith DR, Farris GF, Cordero R (2007) Effects of structural position on allocation and evaluation decisions for scientists and engineers in industrial R&D. Adm Sci Q 52(2):175–207. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.52.2.175

Dovidio JF, Gaertner SL, Kawakami K (2012) Intergroup contact: the past, present, and the future. Journals.Sagepub.Com 6(1):5–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430203006001009

Duhigg C (2016) What google learned from its quest to build the perfect team. N Y Times https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/28/magazine/what-google-learned-from-its-quest-to-build-the-perfect-team.html

Fraser N (1989) Unruly practices: power, discourse, and gender in contemporary social theory. In: Feminist review, vol 40(10). University of Minnesota Press, pp. 107–108

Gaughan M, Bozeman B (2016) Using the prisms of gender and rank to interpret research collaboration power dynamics. Soc Stud Sci 46(4):536–558. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312716652249

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Gibbons M, Limoges C, Nowotny H, Schwartzman S (1994) The new production of knowledge: the dynamics of science and research in contemporary societies. In CI, Sage Publications, London. pp. ix+179

Ginther DK, Schaffer WT, Schnell J, Masimore B, Liu F, Haak LL, Kington R (2011) Race, ethnicity, and NIH research awards. Science 333(6045):1015–1019. https://doi.org/10.1126/SCIENCE.1196783/SUPPL_FILE/GINTHER_SOM.PDF

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Giuffre K (2013) Communities and networks: using social network analysis to rethink urban and community studies, 1st ed. Polity Press.

Granovetter MS (1973) The strength of weak ties. Am J Sociol 78(6):1360–1380

Greenwood RE (1993) The case study approach. Bus Commun Q 56(4):46–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/108056999305600409

Guarino CM, Borden VMH (2017) Faculty service loads and gender: are women taking care of the academic family. Res High Educ 58(6):672–694. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-017-9454-2

Guimerà R, Uzzi B, Spiro J, Nunes Amaral LA, Amaral LAN, Nunes Amaral LA, Guimera R, Brian U, Spiro J, Amaral LAN, Guimerà R, Uzzi B, Spiro J, Nunes Amaral LA (2005) Sociology: team assembly mechanisms determine collaboration network structure and team performance. Science 308(5722):697–702. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1106340

Hall KL, Vogel AL, Huang GC, Serrano KJ, Rice EL, Tsakraklides SP, Fiore SM (2018) The science of team science: a review of the empirical evidence and research gaps on collaboration in science. Am Psychol 73(4):532–548. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000319

Handley IM, Brown ER, Moss-Racusin CA, Smith JL (2015) Quality of evidence revealing subtle gender biases in science is in the eye of the beholder. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112(43):13201–13206. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1510649112

Hanneman R, Riddle M (2005) Introduction to social network methods. http://www.researchgate.net/profile/Robert_Hanneman/publication/235737492_Introduction_to_social_network_methods/links/0deec52261e1577e6c000000.pdf

Hansson B (1999) Interdisciplinarity: for what purpose? Policy Sci 32(4):339–343. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1004718320735