Wonder in Mathematics

[verb] + [noun]: Wondering about and creating wonder

My maths autobiography

School maths

I have always loved maths, but the reasons why have changed dramatically over time.

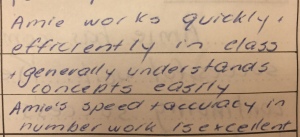

This is my Year 1 work. It reminds me about what I thought it meant to be good at maths: lots of ticks on neat work, especially if it was done quickly.

This attitude was reinforced by my report cards in primary school. A typical one looks like this. Note the focus on speed and accuracy. I loved maths because I was good at it.

Our Year 2 classroom had a corner filled with self-directed puzzle-type problems. If students finished their work early, they could go to the puzzle corner. I recall spending a lot of time there (my report says I was put in an extension group). Looking back, I’m sad that not every student had the same opportunities to engage with these richer, stimulating problems.

Outside of school, I loved doing and making up puzzles. I looked for patterns everywhere. I was always thinking about different ways to count, to organise, and to get things done more quickly. Growing up on a rural property, I had a lot of chores and time to think. For example, I’d think about how many buckets of oranges I could pick in an hour, how long it would take us to fill an orange picking bin, the different ways I could climb the rungs of the ladder, and so on. But I didn’t connect these ideas to maths.

Most of my school maths memories involve doing exercise after exercise from the textbook, but that was fine by me because I could put a self-satisfied tick next to each neatly done problem (after checking the answer in the back of the book!). I remember one high-school maths project to work out the most efficient way to wrap a Kit Kat in foil. It stands out in my memory because it was so different to the rest of maths class.

There were gaps in my knowledge along the way that I tried to cover up. I missed a month of Year 4 due to illness, and a substantial chunk of that time was devoted to fractions. When I got to algebraic fractions in later years, I would furtively use my calculator on simple examples to see if I could work out the right ‘rule’. Now I congratulate myself on having the sense to work it out for myself by generalising from specific examples. In Year 12 I felt embarrassed for using straws and Blu Tack to make visualisations of 3D coordinate geometry; everyone else could do it in their heads. Now I’m proud that I found a tool to help me make sense of the maths.

In Year 12 I hit a big obstacle. All my grades went downhill, including in maths. My maths report card says that I was ‘prone to panic attacks when working against a time constraint’. I don’t remember that, although I do remember crying (which I almost never do) in my maths teacher’s office and thinking that I didn’t know anything. I realise now that much of my maths schooling was about memorisation but not about understanding, and that it had caught up with me by Year 12.

Despite my mostly mediocre grades (I got a D in physics!), I did okay and was offered several university places. My love of the English language drew me to careers such as law, journalism and psychology. But I had also applied for and been offered a place in mathematics. Despite this, I chose to repeat Year 12. I took maths again because I still enjoyed it. The second time around it seemed to make a lot more sense; my scores were 19 and 19.5 for Maths 1 and 2. At the end of Year 13 I was awarded one of the first UniSA Hypatia Scholarships for Mathematically Talented Women. This boosted my confidence and made University study more affordable for a country kid. So, I decided to do mathematics. I also enrolled in a computer science major because I wasn’t sure what kind of job you could get with a maths degree.

University days

Most of my undergraduate mathematics experience was the same as high school. I got Distinctions or High Distinctions for all my subjects (except Statistics 3B where I scraped a pass). I did most of my thinking in my head and then committed it to paper. I produced beautiful notes, and would rewrite a page if it had a single mistake on it. On reflection, I had a fairly superficial understanding of mathematics, but knew what to do to get good marks. I got disenchanted in the third year of my four-year degree and briefly considered quitting, but I had never quit something so important so I kept going.

At the end of third year, I had an experience that made me sure I wanted to be a mathematician. I attended a Mathematics-in-Industry Study Group. This is a five-day event that draws together around 100 mathematicians. On the first day, we listen to five or six different companies tell us about a problem they have that needs solving. For example, they might say ‘we want to stop washing machines from walking across the floor when they are unbalanced’ or ‘we want to know the best way to pack apples in cartons’. The mathematicians then decide which problem they want to work on, and smaller groups spend the next three and a half days feverishly trying to find a solution.

It was transformative as I witnessed, first-hand, mathematics put into action. I also saw how mathematicians creatively and collaboratively approach solving problems. I watched accomplished mathematicians initially not know how to start. I saw them making mistakes. They had intense (but friendly) discussions about whether something was the right approach. It was a defining moment, because it showed me how mathematics is really done, beyond learning mathematics that’s already known, or applying algorithms without a sense of why we would do so. I saw the true habits of mathematicians in action. I also discovered the important role that communication plays in mathematics, and that I could put my love of the English language to good use.

The transition from doing maths exercises with answers that were ‘perfect’ the first time to the more authentic and messy problem-solving required for mathematical research was not an easy one for me. I found it difficult in my PhD to accept that I was not perfect and that I had to constantly draft and refine both my mathematical ideas and my writing, especially because I had never been taught these skills. But I was helped in being surrounded by more experienced mathematicians who modelled, if not explicitly articulated, that this was how mathematicians really work.

It’s eight years since I was awarded my PhD, and I can now say that I am quite comfortable with this ‘messy’ approach to maths. I like to say that mathematicians are chronically lost and confused, and that is how it is supposed to be . It would be ridiculous for mathematicians to spend their days solving problems that they already know how to solve. So, being uncertain about whether something will work, or uncertain about what to do next, is a natural way for mathematicians to be.

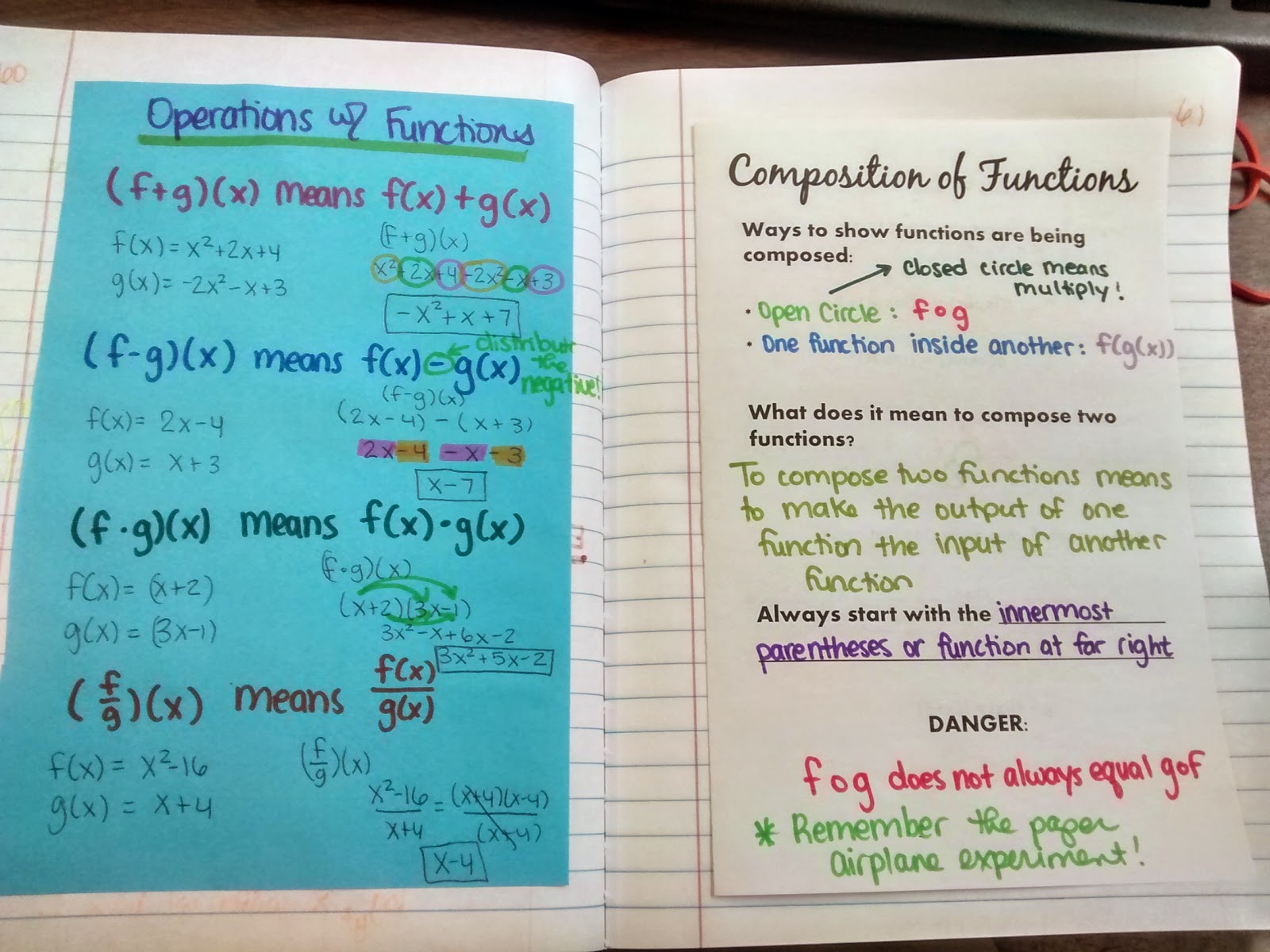

Teaching maths

I started teaching mathematics during my PhD. At first I taught exactly as I had been taught, with procedures and algorithms. But I also didn’t want to respond to a student with ‘Because that’s the rule’, so I started trying to really understand why maths concepts worked the way they did. I learned so much more about maths when I started to explain it to others. The way I taught expanded to include visual ways to think about maths, a variety of representations and approaches, and other flexible ways of thinking. It wasn’t natural to me at first (and at times I still solve arithmetical problems in my head by imagining a pen writing the algorithm) but it has immeasurably enriched my own understanding of mathematical concepts.

I also realised that the way I was taught was not the way I wanted to teach, but I wasn’t sure how to change that. I sought ideas from the internet, and eventually stumbled into the early days of the online community that is the MTBoS (the Math Twitter Blogosphere), although I didn’t realise that until much later. I lurked for a long time because I felt like an outsider: I wasn’t a school teacher (what did I know about education?!) and I wasn’t located in North America. Today I couldn’t imagine teaching without the support of my professional community on Twitter which extends all around the world.

Around five years ago I decided that I could help break the cycle of traditional procedural-based teaching by supporting students, particularly preservice teachers, in experiencing maths in the ways that I and other professional mathematicians do. So, I designed a course that gives students these problem-solving experiences alongside learning skills for thinking and working mathematically. I hold these word clouds from Tracy Zager in my head as a reminder and a motivation of what I am trying to accomplish. (You can read more about how I found them here .)

I still love ‘cracking puzzles’ in maths like I did in Year 2, but my love of maths has expanded to include learning how others think about mathematical ideas. In almost every class I see a student think about a problem in a way I’d never imagined, and I love it. Listening to student thinking is why I’ll never tire of teaching, and it helps me to be a better teacher. I can’t wait to learn from you.

Share this:

5 thoughts on “ my maths autobiography ”.

You are an inspiration Amie – I love that you have shared your journey. It gives me confidence to continue to pursue your approach to teaching mathematics in my role as a mathematics teacher to young people.

Thanks Vanessa. It’s my respect for the work that you and your colleagues do that made me realise I have to learn a lot more about school teaching. So I’m about to start a Master of Teaching. Wish me luck!

I’m inspired about what we can do as a community when we work together. I’ve read a lot of maths autobiographies recently, and they almost all talk about procedurally-based classrooms. But I hope we are making an impact. I can’t wait to read the maths autobiographies of our students!

Thanks for this Amie. My journey in maths has similarities to yours. Unlike you it was not events within the research community that lead me to a transformative experience, rather it was conversations with a mathematics educator that brought things together.

I was capable at what I was asked to do at school. And I certainly remember speed and accuracy being rewarded there. University was more of the same and looking back I learnt how to do well, without any deep understanding. I did get frustrated at the assessment and got a sense that exams were a speed contest, not an opportunity to show deep understanding.

Unfortunately for me I feel as though my honours and postgraduate years were so overly scaffolded that even then I didn’t really learn what it is to do mathematics. No disrespect at all to my supervisor who is one Australia’s finest applied mathematicians – I know he thought he was doing his best by me. At the time, I thought his approach to my “research” internship was entirely appropriate, because it was like my undergraduate years. Looking back I wish he wasn’t so attentive and had me work out things for myself.

I finished my PhD in three years and three weeks and the following day took up my lecturing job in north QLD. This was 1993. I had moved to a department in decline and there was no broad culture of research or doing of mathematics. The most authentic doers of mathematics were actually the physicists on the floor below, but it took me a while to work this out. It was very much a place where we did direct teaching in the way I had experienced as a student.

By 2007 I was in a multi-disciplinary school and my responsibilities extended outside of mathematics into physics and assisting with off-shore delivery of IT. Somehow my efforts in teaching were recognised and I got approached to take a leadership role in the science faculty. It was a role where I had no power. I was supposed to use my “influence” to raise the profile of teaching. This did give me an opportunity to reflect – not on mathematics, but on what we were doing in our BSc – and I decided to focus on numeracy, because I knew this was an issue frequently discussed by the cohort of academics. I got to mix with other learning and teaching people across Australia and be involved in some great projects.

In 2010 I decided I needed some help from somebody with a knowledge of education, because I wanted to formalise some of the work I had been doing. I ended up meeting the mathematics educator, Jo Balatti. I did not ask for her. This was the person the Head of Education got me to meet.

It did not take long before Jo started telling me about her struggles with the maths pedagogy subject. She very quickly got me to realise that I as a mathematician had a responsibility to focus on the cohort of preservice maths teachers. There was a lot of distrust between education and the sciences and maths within the university, so there was not a history of cooperation. But Jo pointed out to me that her students were doing at least four subjects of maths in my discipline before she begins to teach them maths pedagogy in education – and that her experience was these students were very weak when it came to explaining mathematics concepts and procedures.

My interactions with Jo lead to a lot of reflection by me about mathematics and the way it needs to be taught. This is not to say that I had not contemplated this before. Despite my own lack of profile in research mathematics I knew enough from the conference circuit that mathematics is a very powerful bunch of knowledge and pursuits in mathematics are not procedural in nature. However it was not until I thought about Jo’s words that I really began to understand how our approaches in maths teaching were unhelpful.

Jo & I co-wrote a subject for preservice maths teachers – and this subject has given me an opportunity to revisit so much of mathematics – in a way that we hope helps aspiring maths teachers to do a good job. And I agree with the message in the word clouds of Tracy Zager – that there is so much to the body of knowledge we call mathematics that we ought to get across. This includes the messiness of problem solving and the absolute thrill of the light-bulb moments where connections are made and the beauty of the structures within mathematics are revealed.

- Pingback: (Some of) my mathematical journey | L'Infinit: the unfinished business of mathematics

- Pingback: The shape of our mathematical beliefs – Wonder in Mathematics

Leave a comment Cancel reply

Blog at WordPress.com.

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Exploring Mathematical Identities Through Autobiographies

Everyone has a "math story".

Updated January 23, 2024

- Why Education Is Important

- Take our ADHD Test

- Find a Child Therapist

In my discipline, Sociology, analyzing autobiographies, or life histories, has a rich foundation. Such narrative analysis enables us to gain insight into the phenomenological life worlds of both self and others. The quintessential example of a classic sociological study employing the use of autobiographical data is The Polish Peasant in Europe and America by W.I. Thomas and Florian Znaniecki (1918). Their analysis of familial letters exchanged between new immigrants to the U.S. and their family members in Poland shed light on the effects of immigration, industrialization, disintegration, and reorganization. Of course Sociology does not solely lay claim to utilizing the method of autobiographical analysis. Many disciplines – and not just in the social sciences – recognize the value of autobiographies in understanding subjective experiences in a holistic and reflective manner.

Recent collaborations with my colleague Carmen Latterell, who is in the field of Math Education , have demonstrated that math autobiographies can be used by researchers to better understand current and future teachers’ approaches to the study and teaching of mathematics. Researchers who have collected math autobiographies from current teachers as well as from both preservice elementary and secondary teachers have shown that individuals’ written narratives of their experiences with mathematics provide a window to their mathematical identities while also describing experiences with, and feelings toward, math that shape how they approach the teaching of the subject matter in their own classrooms. Mixes of positive and negative experiences with math are revealed in individuals’ math autobiographies. Not surprisingly, one’s teachers and family members have a large effect on one’s attitudes about math. With respect to former teachers, both good and bad experiences shape attitudes about and approaches toward math. While having had good teachers in the past provides future teachers excellent role models and are an inspiration, having had bad teachers also serves as a motivator – in particular, future teachers note that they will be sure not to repeat some of the poor practices and approaches they had to endure from some of their former teachers.

Math autobiographies provided by research participants highlight both minor and major setbacks – in some cases, the writers of the autobiographies express that they sought out alternative methods for learning the material outside of what was being done in the classroom; in other cases, individuals report simply giving up. Sadly, amongst those in the latter group, any sense of self-efficacy with respect to math was lost. Narratives also demonstrate the difference that particular branches of math can make in one’s interest and confidence level. For instance, some individuals indicate that they absolutely loved algebra but hated geometry, or vice versa.

Math is ubiquitous. We don’t need to be math teachers or working in a field that draws heavily from math, such as engineering, to recognize the relevance and daily necessity of mathematical properties. Whether we are measuring ingredients for a meal we are preparing, figuring out the best deal on an item in the store, counting beats as we practice our musical instrument, or computing the number of calories we are burning during our exercise regimen, we are inevitably relying upon our understanding of math. In this sense, each one of us has a math autobiography ; each of us has a math identity . As noted, researchers have collected the math autobiographies of current and future teachers. In the interest of broadening the scope, please share your math autobiography (whether through the comments function on this site or by sending me an email). In essence, describe how you identify yourself mathematically, including how particular people, events, and experiences have shaped who you are mathematically from as early as you remember until now. What is your math story?

Drake, C. (2006). Turning points: Using teachers’ mathematics life stories to understand the implementation of mathematics education reform. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 9, 579-608.

Ellsworth, J. Z., & Buss, A. (2000). Autobiographical stories from preservice elementary mathematics and science students: Implications for K-16 teaching. School Science and Mathematics, 100(7), 355-364.

Guillaume, A. M., & Kirtman, L. (2010). Mathematics stories: Preservice teachers’ images and experiences as learners of mathematics. Issues in Teacher Education, 19(1), 121-143.

Latterell, C.M. & Wilson, J.L. (in press).

McCulloch, A., Marshall, P. L., DeCuir-Gunby, J. T., & Caldwell, T. S. (2013). Math autobiographies: A window into teachers’ identities as mathematics learners. School Science and Mathematics, 113(8), 380-389.

Thomas, W. I. & Znaniecki, F. (1918-1920). The Polish peasant in Europe and America. (5 volumes). Boston: Gorham Press.

Janelle Wilson, Ph.D., is a professor of sociology at the University of Minnesota Duluth.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Sticking up for yourself is no easy task. But there are concrete skills you can use to hone your assertiveness and advocate for yourself.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

100 Best Mathematician Biography Books of All Time

We've researched and ranked the best mathematician biography books in the world, based on recommendations from world experts, sales data, and millions of reader ratings. Learn more

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks

Rebecca Skloot | 5.00

Yet Henrietta Lacks remains virtually unknown, buried in an unmarked grave.

Now Rebecca Skloot takes us on an extraordinary journey, from the “colored” ward of Johns Hopkins Hospital in the 1950s to stark white laboratories with freezers full of HeLa cells; from Henrietta’s small, dying hometown of Clover, Virginia — a land of wooden slave quarters, faith healings, and voodoo — to East Baltimore today, where her children and grandchildren live and struggle with the legacy of her cells.

Henrietta’s family did not learn of her “immortality” until more than twenty years after her death, when scientists investigating HeLa began using her husband and children in research without informed consent. And though the cells had launched a multimillion-dollar industry that sells human biological materials, her family never saw any of the profits. As Rebecca Skloot so brilliantly shows, the story of the Lacks family — past and present — is inextricably connected to the dark history of experimentation on African Americans, the birth of bioethics, and the legal battles over whether we control the stuff we are made of.

Over the decade it took to uncover this story, Rebecca became enmeshed in the lives of the Lacks family—especially Henrietta’s daughter Deborah, who was devastated to learn about her mother’s cells. She was consumed with questions: Had scientists cloned her mother? Did it hurt her when researchers infected her cells with viruses and shot them into space? What happened to her sister, Elsie, who died in a mental institution at the age of fifteen? And if her mother was so important to medicine, why couldn’t her children afford health insurance?

Intimate in feeling, astonishing in scope, and impossible to put down, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks captures the beauty and drama of scientific discovery, as well as its human consequences.

Carl Zimmer Yes. This is a fascinating book on so many different levels. It is really compelling as the story of the author trying to uncover the history of the woman from whom all these cells came. (Source)

A.J. Jacobs Great writer. (Source)

See more recommendations for this book...

Walter Isaacson | 4.93

Elon Musk Quite interesting. (Source)

Bill Gates [On Bill Gates's reading list in 2012.] (Source)

Gary Vaynerchuk I've read 3 business books in my life. If you call [this book] a business book. (Source)

Hidden Figures

The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space Race

Margot Lee Shetterly | 4.89

Set against the backdrop of the Jim Crow South and the civil rights movement, the never-before-told true story of NASA’s African-American female mathematicians who played a crucial role in America’s space program—and whose contributions have been unheralded, until now.

Before John Glenn orbited the Earth or Neil Armstrong walked on the moon, a group of professionals worked as “Human Computers,” calculating the flight paths that would enable these historic achievements. Among these were a coterie of bright, talented African-American women. Segregated from their white counterparts by...

Before John Glenn orbited the Earth or Neil Armstrong walked on the moon, a group of professionals worked as “Human Computers,” calculating the flight paths that would enable these historic achievements. Among these were a coterie of bright, talented African-American women. Segregated from their white counterparts by Jim Crow laws, these “colored computers,” as they were known, used slide rules, adding machines, and pencil and paper to support America’s fledgling aeronautics industry, and helped write the equations that would launch rockets, and astronauts, into space.

Drawing on the oral histories of scores of these “computers,” personal recollections, interviews with NASA executives and engineers, archival documents, correspondence, and reporting from the era, Hidden Figures recalls America’s greatest adventure and NASA’s groundbreaking successes through the experiences of five spunky, courageous, intelligent, determined, and patriotic women: Dorothy Vaughan, Mary Jackson, Katherine Johnson, Christine Darden, and Gloria Champine.

"Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman!"

Adventures of a Curious Character

Richard P. Feynman, Ralph Leighton, Edward Hutchings, Albert R. Hibbs | 4.76

Sergey Brin Brin told the Academy of Achievement: "Aside from making really big contributions in his own field, he was pretty broad-minded. I remember he had an excerpt where he was explaining how he really wanted to be a Leonardo [da Vinci], an artist and a scientist. I found that pretty inspiring. I think that leads to having a fulfilling life." (Source)

Larry Page Google co-founder has listed this book as one of his favorites. (Source)

Peter Attia The book I’ve recommended most. (Source)

A Beautiful Mind

Sylvia Nasar | 4.74

Ariel Rubinstein The story of John Nash is really a human story – I don’t think it sheds much light on game theory. But it gives hope to people dealing with this disease. (Source)

Diane Coyle This is a terrific book for just saying something about what game theory helps to do, without plunging you into all the complicated mathematics of how to do it in practice. (Source)

The Man Who Loved Only Numbers

The Story of Paul Erdős and the Search for Mathematical Truth

Paul Hoffman | 4.72

The Last Lecture

Randy Pausch, Jeffrey Zaslow, et al | 4.71

Gabriel Coarna I read "The Last Lecture" because I had seen Randy Pausch give this talk: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ji5_MqicxSo (Source)

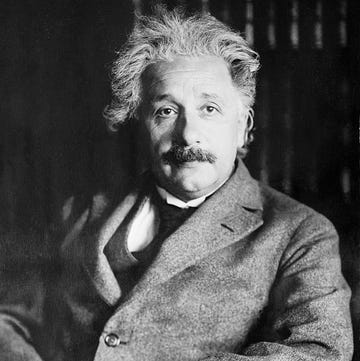

His Life and Universe

Walter Isaacson | 4.71

Bill Gates [On Bill Gates's reading list in 2011.] (Source)

Elon Musk I didn't read actually very many general business books, but I like biographies and autobiographies, I think those are pretty helpful. Actually, a lot of them aren't really business. [...] I also feel it’s worth reading books on scientists and engineers. (Source)

Scott Belsky [Scott Belsky recommended this book on the podcast "The Tim Ferriss Show".] (Source)

Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic Future

Ashlee Vance | 4.68

Richard Branson Elon Musk is a man after my own heart: a risk taker undaunted by setbacks and ever driven to ensure a bright future for humanity. Ashlee Vance's stellar biography captures Musk's remarkable life story and irrepressible spirit. (Source)

Casey Neistat I'm fascinated by Elon Musk, I own a Tesla, I read Ashlee Vance's biography on Elon Musk. I think he's a very interesting charachter. (Source)

Roxana Bitoleanu A business book I would definitely choose the biography of Elon Musk by Ashlee Vance, because of Elon's strong, even extreme ambition to radically change the world, which I find very inspiring. (Source)

The Man Who Knew Infinity

A Life of the Genius Ramanujan

Robert Kanigel | 4.68

Don't have time to read the top Mathematician Biography books of all time? Read Shortform summaries.

Shortform summaries help you learn 10x faster by:

- Being comprehensive: you learn the most important points in the book

- Cutting out the fluff: you focus your time on what's important to know

- Interactive exercises: apply the book's ideas to your own life with our educators' guidance.

Leonardo da Vinci

Walter Isaacson | 4.63

Bill Gates I think Leonardo was one of the most fascinating people ever. Although today he’s best known as a painter, Leonardo had an absurdly wide range of interests, from human anatomy to the theater. Isaacson does the best job I’ve seen of pulling together the different strands of Leonardo’s life and explaining what made him so exceptional. A worthy follow-up to Isaacson’s great biographies of Albert... (Source)

Satya Nadella Microsoft CEO has plunged into what must be an advance copy of Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson, who has written biographies of Steve Jobs, Albert Einstein and Ben Franklin. Isaacson’s biography is based on the Renaissance master’s personal notebooks, so you know we’re going to be taken into the creative mind of the genius. (Source)

Ryan Holiday Truly excellent book about one of history’s all time greats. (Source)

Benjamin Franklin

An American Life

Elon Musk I didn't read actually very many general business books, but I like biographies and autobiographies, I think those are pretty helpful. Actually, a lot of them aren't really business. [...] Isaacson's biography on Franklin is really good. Cause he was an entrepreneur and he sort of started from nothing, actually he was just like a run away kid, basically, and created his printing business and sort... (Source)

Brandon Stanton The [biography of Benjamin Franklin] I read. (Source)

The Biography of a Dangerous Idea

Charles Seife | 4.53

Alex Bellos Unlike Ifrah, Charles Seife is a brilliant popular science writer who has here written the ‘biography’ of zero. And even though he doesn’t talk that much about India, it works well as a handbook to Ifrah’s sections on India. Because Seife talks about how zero is mathematically very close to the idea of infinity, which is another mathematical idea that the Indians thought about differently. Seife... (Source)

Bryan Johnson Chronicles how hard it was for humanity to come up with and hold onto the concept of zero. No zero, no math. No zero, no engineering. No zero, no modern world as we know it... (Source)

Never at Rest

A Biography of Isaac Newton

Richard S. Westfall | 4.48

William Newman It’s a magisterial book. It’s the only treatment of Newton that really tries to give a detailed study of the totality of his science alongside his religion and his work on alchemy, which covered more than 30 years. (Source)

The Wright Brothers

David McCullough | 4.48

Ed Zschau A fabulous book. (Source)

Paul Halmos

Celebrating 50 Years of Mathematics

John Ewing, F.W. Gehring | 4.47

How to Change Your Mind

What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence

POLLAN MICHAE | 4.47

Daniel Goleman Michael Pollan masterfully guides us through the highs, lows, and highs again of psychedelic drugs. How to Change Your mind chronicles how it’s been a longer and stranger trip than most any of us knew. (Source)

Yuval Noah Harari Changed my mind, or at least some of the ideas held in my mind. (Source)

David Heinemeier Hansson How we get locked into viewing the world, ourselves, and each other in a certain way, and then finding it difficult to relate to alternative perspectives or seeing other angles. Studying philosophy, psychology, and sociology is a way to break those rigid frames we all build over time. But that’s still all happening at a pretty high level of perception. Mind altering drugs, and especially... (Source)

An Astronaut's Guide to Life on Earth

Chris Hadfield | 4.44

James Altucher And while you are at it, throw in “Bounce” by Mathew Syed, who was the UK Ping Pong champion when he was younger. I love any book where someone took their passion, documented it, and shared it with us. That’s when you can see the subleties, the hard work, the luck, the talent, the skill, all come together to form a champion. Heck, throw in, “An Astronaut’s Guide to Earth” by Commander Chris... (Source)

Chris Goward Here are some of the books that have been very impactful for me, or taught me a new way of thinking: [...] An Astronaut's Guide to Life on Earth. (Source)

Simon Carley Also love the idea of being a zero. Totally agree that some of my finest colleagues are that. I’m fact the doc I want to look after me in resus is defo a zero. (Read the book to find out why). (Source)

My Family and Other Animals (Corfu Trilogy #1)

Gerald Durrell | 4.44

M G Leonard It’s a real work of genius and needs to be kept on every child’s bedside table. (Source)

Women in Science

50 Fearless Pioneers Who Changed the World

Rachel Ignotofsky | 4.43

The Ghost Map

The Story of London's Most Terrifying Epidemic—and How It Changed Science, Cities, and the Modern World

Steven Johnson | 4.42

Seth Mnookin The Ghost Map is a book that I oftentimes give to people to show them how cool and exciting and accessible and gripping stories about scientific discoveries can be. (Source)

Alison Alvarez I read the Ghost Map, a book about 1854 London Cholera outbreak. The outbreak was stopped because of a map created by Dr. John Snow. You can see hints of this map in some of our customer discovery tools because it was such an effective way of pinpointing a solution to a seemingly insurmountable problem. (Source)

Stephen Evans Johnson looks at London during a specific moment in time, August 1854, and focuses on a particular incident, an outbreak of cholera in Soho, in Central London. (Source)

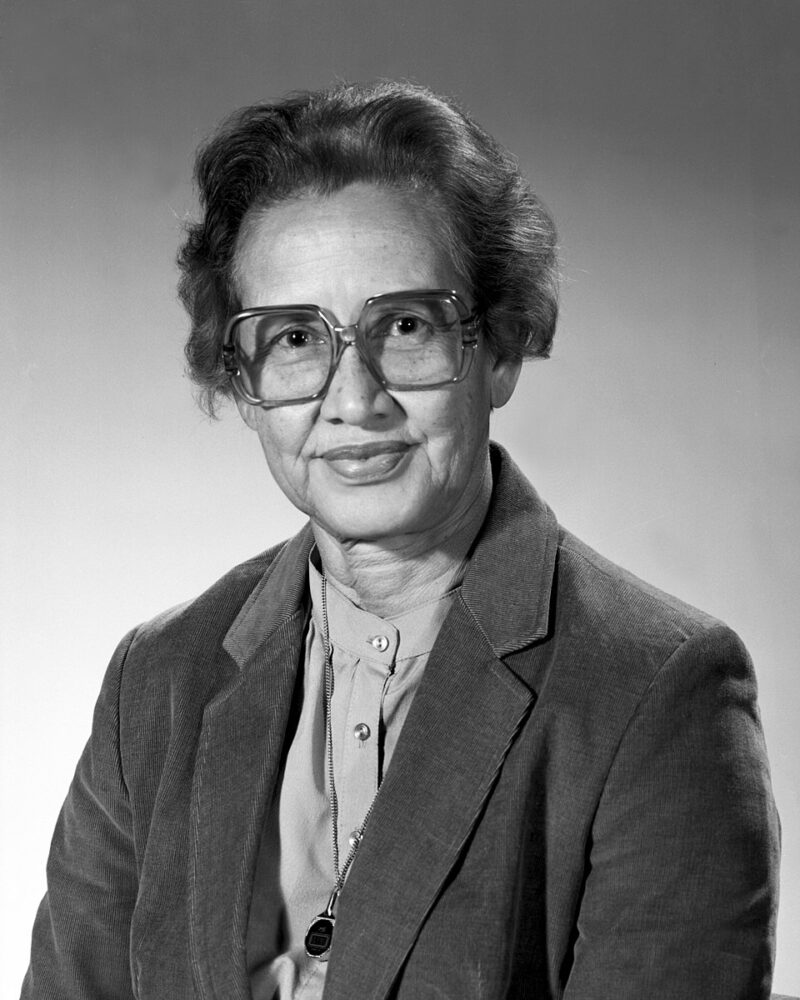

Katherine Johnson

Thea Feldman and Alyssa Petersen | 4.42

The Innovators

How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution

Walter Isaacson | 4.41

Chris Fussell The history of how great ideas evolve. (Source)

Brian Burkhart This book is essentially a biography of all the people who’ve led to the technology of today—it’s fascinating. The most important point of the book is everything is one long, connected chain. There isn’t just one person or one industry that makes anything happen—it all goes way back. For example, the communication theory I have espoused and taught throughout my career is from Aristotle, Socrates,... (Source)

Sean Gardner @semayuce @MicrosoftUK @HelenSharmanUK @astro_timpeake @WalterIsaacson Yes, I agree: "The Innovators" is a great book. I loved it too. (Source)

I Want to Be a Mathematician

An Automathography

P.R. Halmos | 4.41

Human Computer

Mary Jackson, Engineer

Andi Diehn and Katie Mazeika | 4.41

My Brain is Open

The Mathematical Journeys of Paul Erdős

Bruce Schechter | 4.38

Mathematicians Are People, Too

Stories from the Lives of Great Mathematicians, Volume 1

DALE SEYMOUR PUBLICATIONS | 4.38

Reaching for the Moon

The Autobiography of NASA Mathematician Katherine Johnson

Katherine Johnson | 4.37

A Mind at Play

How Claude Shannon Invented the Information Age

Jimmy Soni, Rob Goodman | 4.37

Erik Rostad Here is something that recently helped me. It comes from the book A Mind at Play by Jimmy Soni & Rob Goodman. I'll quote the passage directly and then describe how it helped me: "What does information really measure? It measures the uncertainty we overcome. It measure our chances of learning something we haven't yet learned. Or, more specifically: when one thing carries information about... (Source)

Bryan Johnson [Bryan Johnson recommended this book on Twitter.] (Source)

The Facebook Effect

The Inside Story of the Company That is Connecting the World

David Kirkpatrick | 4.37

Dustin Moskovitz [Dustin Moskovitz recommended this book during a Stanford lecture.] (Source)

Craig Pearce If you read to maintain motivation and be entertained, I recommend a few books that in addition to telling great stories, also contain lessons and learnings. You won’t gain many step-by-step type lessons from these books but you will come away realizing that not all startups, regardless of what stage they are in, are as well polished as they make you think. You will realize that they make... (Source)

Angela Pham The Facebook Effect by David Kirkpatrick made me a fan of Mark Zuckerberg and Sheryl Sandberg years ago. I didn’t hesitate to take my current role at Facebook because I feel so strongly about their integrity and leadership, no matter the negative sentiments and media narratives the company has endured recently. (Source)

The Life and Science of Richard Feynman

James Gleick | 4.36

Naval Ravikant I’ve been reading Perfectly Reasonable Deviations, and I’ve also been rereading Genius. (Source)

Failure Is Not an Option

Mission Control from Mercury to Apollo 13 and Beyond

Gene Kranz | 4.36

Dominic D'agostino Gene Kranz has always been a huge inspiration. Just finished his book "Failure is not an option". The level of detail he goes into describing mission control is fantastic. https://t.co/ii5UpJBKty https://t.co/wPc9anl07C (Source)

Fate Is the Hunter

Ernest K. Gann | 4.35

William Dunham | 4.35

Women in Mathematics

The Addition of Difference

Claudia Henrion | 4.34

Computer Decoder

Dorothy Vaughn, Computer Scientist

Andi Diehn and Katie Mazeika | 4.34

An Informal History of Liquid Rocket Propellants

John Drury Clark, Isaac Asimov | 4.34

Elon Musk There is a good book on rocket stuff called Ignition! [An informal history of liquid rocket propellants] by John Clark, that’s a really fun one. (Source)

The Cuckoo's Egg

Clifford Stoll | 4.33

Rick Klau @AtulAcharya @stevesi Same. Read it in college, realized I was more excited about the tech than what I was studying -- and Cliff did such a great job helping you understand what was going on. Such a great book. (Source)

James Stanley "The Cuckoo's Egg" by Clifford Stoll is another great book. I believe it's the first documented account of a computer being misused by a remote attacker. It talks about how Clifford attached physical teleprinters to the incoming phone lines so that he could see what the attacker was actually doing on the computer, and how he traced the attacker across several countries. (Source)

Bitcoin Billionaires

A True Story of Genius, Betrayal, and Redemption

Ben Mezrich | 4.33

Kim Dotcom The Winklevoss brothers mailed me this awesome must-read book #bitcoinbillionaires with a really nice personal note. Thank you @winklevoss and @tylerwinklevoss. Facebook was stolen from you but what you’ve created since then is even more impressive. Crypto is the future. https://t.co/iAkfU1Dm65 (Source)

Bill Lee Thank you @tylerwinklevoss @winklevoss for sending me the must read @benmezrich book with the nice signed note. You guys are ushering in the crypto revolution and have captured lightning in a bottle again. #respect #BitcoinBillionaires https://t.co/QNaJLkQPJa (Source)

Leonhard Euler

Mathematical Genius in the Enlightenment

Ronald S. Calinger | 4.33

Robin Wilson Ron (Source)

DK Life Stories

Ebony Joy Wilkins and Charlotte Ager | 4.32

Prime Obsession

Bernhard Riemann and the Greatest Unsolved Problem in Mathematics

John Derbyshire | 4.32

The Undoing Project

A Friendship That Changed Our Minds

Michael Lewis | 4.31

Doug McMillon Here are some of my favorite reads from 2017. Lots of friends and colleagues send me book suggestions and it's impossible to squeeze them all in. I continue to be super curious about how digital and tech are enabling people to transform our lives but I try to read a good mix of books that apply to a variety of areas and stretch my thinking more broadly. (Source)

David Heinemeier Hansson Michael Lewis is just a great storyteller, and tell a story in this he does. It’s about two Israeli psychologists, their collaboration on the irrationality of the human mind, and the milestones they set with concepts like loss-aversion, endowment effect, and other common quirks that the assumption of rationality doesn’t account for. It’s a bit long-winded, but if you like Lewis’ style, you... (Source)

Francisco Perez Mackenna This summer, Mackenna is learning more about the birth of behavioral economics, the psychology of white collar crime, and the restoration of American cities as locations of economic growth. (Source)

NASA Mathematician Katherine Johnson NASA Mathematician Katherine Johnson

Heather E. Schwartz | 4.31

American Prometheus

The Triumph & Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer

Kai Bird, Martin J. Sherwin | 4.31

David Blaine One of the more fascinating men that I’ve read about. (Source)

Fourteen Billion Years of Cosmic Evolution

Neil deGrasse Tyson, Vikas Adam, et al | 4.31

A Year in Space, A Lifetime of Discovery

Scott Kelly | 4.31

Eric Ries Kelly spent a record-breaking year in space and this book is a fascinating account of that time and what he learned about humanity and himself. (Source)

Anoop Anthony Reading Endurance puts things in perspective; some of us have callings with remarkable purpose — the very future of humankind — at significant risk to one's own life and creature comforts. It may sound corny, but it makes one wonder: can the work we do in our industries and businesses have a higher purpose than just commercial success? (Source)

Thunderstruck

Erik Larson | 4.31

Timothy J. Jorgensen I chose this book because radio waves are a type of radiation. (Source)

Margot Lee Shetterly | 4.31

Based on the New York Times bestselling book and the Academy Award–nominated movie, author Margot Lee Shetterly and illustrator Laura Freeman bring the incredibly inspiring true story of four black women who helped NASA launch men into space to picture book readers!

Dorothy Vaughan, Mary Jackson, Katherine Johnson, and Christine Darden were good at math… really good.

They participated in some of NASA's greatest successes, like providing the calculations for America's first journeys into space. And they did so during a time when being black...

They participated in some of NASA's greatest successes, like providing the calculations for America's first journeys into space. And they did so during a time when being black and a woman limited what they could do. But they worked hard. They persisted. And they used their genius minds to change the world.

In this beautifully illustrated picture book edition, we explore the story of four female African American mathematicians at NASA, known as "colored computers," and how they overcame gender and racial barriers to succeed in a highly challenging STEM-based career.

"Finally, the extraordinary lives of four African American women who helped NASA put the first men in space is available for picture book readers," proclaims Brightly in their article "18 Must-Read Picture Books of 2018." "Will inspire girls and boys alike to love math, believe in themselves, and reach for the stars."

Rocket Boys (Coalwood #1)

Homer Hickam | 4.30

Women Who Count

Honoring African American Women Mathematicians

Shelly M. Jones | 4.30

Hidden Valley Road

Inside the Mind of an American Family

Robert Kolker | 4.30

The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind

Creating Currents of Electricity and Hope

William Kamkwamba, Bryan Mealer | 4.30

Cambridge Analytica and the Plot to Break America

Christopher Wylie | 4.30

Wizard: The Life and Times of Nikola Tesla

Biography of a Genius

Marc Seifer | 4.30

Black Pioneers of Science and Invention

Louis Haber | 4.28

Hope Jahren | 4.28

Lost in Math

How Beauty Leads Physics Astray

Sabine Hossenfelder | 4.28

Barbara Kiser This is a firecracker of a book—a shot across the bows of theoretical physics. Sabine Hossenfelder, a theoretical physicist working on quantum gravity and blogger, confronts failures in her field head-on. (Source)

Love and Math

The Heart of Hidden Reality

Edward Frenkel | 4.27

The True Story of a Lone Genius Who Solved the Greatest Scientific Problem of His Time

Dava Sobel, Neil Armstrong | 4.26

Richard Branson Today is World Book Day, a wonderful opportunity to address this #ChallengeRichard sent in by Mike Gonzalez of New Jersey: Make a list of your top 65 books to read in a lifetime. (Source)

Alan Turing

Andrew Hodges, Douglas Hofstadter | 4.26

George Dyson Alan Turing was born exactly 100 years ago, [editor’s note: this interview was done in 2012] and died aged 41. In those 41 years he led an amazing life that is covered with extraordinary grace, complexity and completeness by Andrew Hodges in this biography. It was first published in 1983 and remains in print. (Source)

Ghost in the Wires

My Adventures as the World's Most Wanted Hacker

Kevin Mitnick, Steve Wozniak, William L. Simon | 4.25

If they were a hall of fame or shame for computer hackers, a Kevin Mitnick plaque would be mounted the near the entrance. While other nerds were fumbling with password possibilities, this adept break-artist was penetrating the digital secrets of Sun Microsystems, Digital Equipment Corporation, Nokia, Motorola, Pacific Bell, and other mammoth enterprises. His Ghost in the Wires memoir paints an action portrait of a plucky loner motivated by a passion for trickery, not material game. (P.S. Mitnick's capers have already been the subject of two books and a movie. This first-person account is...

If they were a hall of fame or shame for computer hackers, a Kevin Mitnick plaque would be mounted the near the entrance. While other nerds were fumbling with password possibilities, this adept break-artist was penetrating the digital secrets of Sun Microsystems, Digital Equipment Corporation, Nokia, Motorola, Pacific Bell, and other mammoth enterprises. His Ghost in the Wires memoir paints an action portrait of a plucky loner motivated by a passion for trickery, not material game. (P.S. Mitnick's capers have already been the subject of two books and a movie. This first-person account is the most comprehensive to date.)

Richard Bejtlich In 2002 I reviewed Kevin Mitnick's first book, The Art of Deception. In 2005 I reviewed his second book, The Art of Intrusion. I gave both books four stars. Mitnick's newest book, however, with long-time co-author Bill Simon, is a cut above their previous collaborations and earns five stars. As far as I can tell (and I am no Mitnick expert, despite reading almost all previous texts mentioning... (Source)

Antonio Eram This book was recommended by Antonio when asked for titles he would recommend to young people interested in his career path. (Source)

Nick Janetakis I'm going to start reading Ghost in the Wires by Kevin Mitnick this week. I used to go to 2600 meetings back when he was arrested for wire fraud and other hacking related shenanigans in the mid 1990s. I'm fascinated by things like social engineering and language in general. In the end, I just want to be entertained by his stories. For someone who is into computer programming, a book like this... (Source)

My Inventions

The Autobiography of Nikola Tesla

Nikola Tesla | 4.25

Elon Musk I didn't read actually very many general business books, but I like biographies and autobiographies, I think those are pretty helpful. Actually, a lot of them aren't really business. [...] I think it's also worth reading books on scientists and engineers. Tesla, obviously. (Source)

My Stroke of Insight

A Brain Scientist's Personal Journey

Jill Bolte Taylor | 4.24

Maya Zlatanova [One of the books that had the biggest impact on Maya.] (Source)

Why Fish Don't Exist

A Story of Loss, Love, and the Hidden Order of Life

Lulu Miller | 4.24

Angles of Reflection

Joan L. Richards | 4.23

Men of Mathematics

E.T. Bell | 4.23

A Mathematician's Apology

G. H. Hardy, C. P. Snow | 4.23

Marcus du Sautoy Yes, it really appealed to me when I read it as a kid because I was interested in music, I played the trumpet, I loved doing theatre, and somehow GH Hardy in that book revealed to me how much mathematics is a creative art as much as a useful science. In fact he probably goes further, he really revels in the beauty of the subject and says he’s not particularly interested in the applications. That... (Source)

Plague of Corruption

Restoring Faith in the Promise of Science

Kent Heckenlively | 4.23

One Scientist's Intrepid Search for the Truth about Human Retroviruses and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS), Autism, and Other Diseases

Kent Heckenlively | 4.22

Abel's Proof

An Essay on the Sources and Meaning of Mathematical Unsolvability

Peter Pesic | 4.22

Beyond Banneker

Black Mathematicians and the Paths to Excellence

Erica N. Walker | 4.22

Mathematicians are People, Too

Stories from the Lives of Great Mathematicians (Volume Two)

Luetta Reimer, Wilbert Reimer, et al. | 4.18

God Created the Integers

The Mathematical Breakthroughs That Changed History

Stephen Hawking | 4.18

The Clockwork Universe

Isaac Newton, the Royal Society, and the Birth of the Modern World

Edward Dolnick | 4.17

Remarkable Mathematicians

From Euler to Von Neumann

Ioan James | 4.17

A Mathematician Grappling with His Century

Laurent Schwartz and S. Schneps | 4.17

Adventures of a Mathematician

S. M. Ulam, Daniel Hirsch, et al. | 4.16

The Random Walks of George Polya

George Pólya and Gerald L. Alexanderson | 4.15

Uncanny Valley

Anna Wiener | 4.14

Can Duruk Interesting thread about @annawiener’s book. I’d like us, as the tech industry, to move past framing every single criticism or commentary on our work as “anti tech screed”. Seems like books like this are key, but it requires an open and inquisitive mind more than anything. https://t.co/OCCgGyScwQ (Source)

Kara Swisher @AmyAlex63 @GuardianUS Agreed but it is a great book and very sly (Source)

Robert Went Great book! Uncanny Valley author @annawiener on the stories tech companies tell themselves. My hope is to provide an ordinary employee’s perspective, which is one that for many different reasons is harder for a lot of people to share publicly https://t.co/sUzc5wJeCk (Source)

Code-Breaker and Mathematician Alan Turing

Heather E. Schwartz | 4.14

More Mathematical People

Donald J. Albers, Gerald L. Alexanderson, Constance Reid | 4.13

Prisoner's Dilemma

William Poundstone | 4.13

Constance Reid | 4.13

How Microsoft's Mogul Reinvented an Industry--and Made Himself the Richest Man in America

Stephen Manes, Paul Andrews | 4.12

Returning to Earth

Buzz Aldrin | 4.12

Summary and Analysis of Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space Race

Based on the Book by Margot Lee Shetterly

Worth Books | 4.10

Maurice Mashaal and Anna Pierrehumbert | 4.09

The Mathematician's Shiva

Stuart Rojstaczer | 4.09

Mathematical Apocrypha Redux

More Stories and Anecdotes of Mathematicians and the Mathematical (Spectrum)

Steven Krantz | 4.07

Einstein's Italian Mathematicians

Ricci, Levi-Civita, and the Birth of General Relativity

Judith R. Goodstein | 4.07

John Von Neumann

Norman MacRae | 4.06

Out of the Mouths of Mathematicians

Rosemary Schmalz | 4.05

Mathematical People

Profiles and Interviews

Donald Albers, Gerald L. Alexanderson | 4.04

Math Equals

Biographies of Women Mathematicians+related Activities

Teri Perl | 4.04

Alan M. Turing

Sara Turing | 4.02

Edmund Morris | 4.02

Norbert Wiener--A Life in Cybernetics: Ex-Prodigy: My Childhood and Youth and I Am a Mathematician

The Later Life of a Prodigy

Norbert Wiener and Ronald R. Kline | 4.00

Mathematicians

An Outer View of the Inner World

Mariana Cook | 4.00

The Man Who Knew The Way to the Moon

Todd Zwillich | 3.98

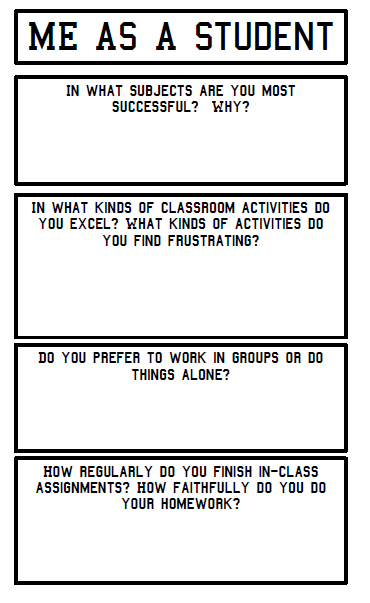

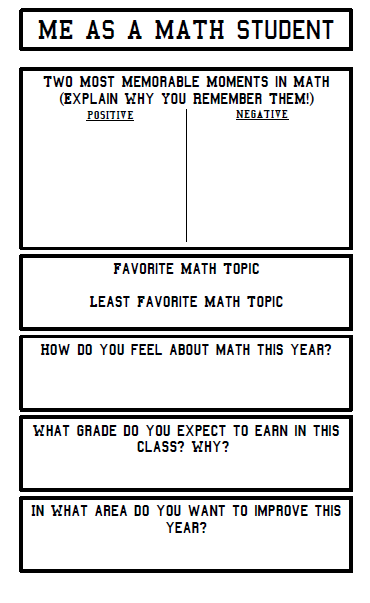

Discovering Each Teacher's "Math Autobiography"

What are the most powerful memories you have about learning math? Did it always feel fun and easy, supported by parents and teachers who gave you confidence? Was it generally enjoyable, but marred by a few bad experiences, like mean teachers, critical parents, and traumatic life events that impacted school? Or has math long felt like a struggle - one where you never received support?

These home and school experiences shape the way we each think about our abilities - and thus, how much we gravitate to, persevere at, and ask for help with our school subjects. They are especially impactful in math, where students may hear the phrase "I'm not a math person" - which conveys the common erroneous belief that math is something you either "get" or you don't. These experiences are a part of each person's "math identity". To support students to be successful mathematicians, teachers must understand the math identities their students bring to the classroom, and commit to being a positive force in shaping them for the future.

Hear Dr. Kim Melgar talk about Preventing and Overcoming Math Trauma on the Mindful Math podcast.

But first, teachers must understand their own math identities. Only by exploring their experiences can they identify how they may replicate their own traumas and biases - or, conversely, re-create the fun, engaging math classrooms and mentor relationships they remember. This is true whether you're a high school calculus teacher or an elementary school teacher who dislikes math. Those for whom math has always "come easily" may need to learn more diverse strategies for breaking down concepts and remaining patient as learners struggle through a task. Those who had punishing or demeaning adults in their lives, or had teachers who simply did not know how to break down a problem, may need to relearn their own confidence and acquire math pedagogy skills. For all groups, remembering the caring, patient, and supportive adults they still cherish, is a welcome reminder of just how much impact one teacher can make.

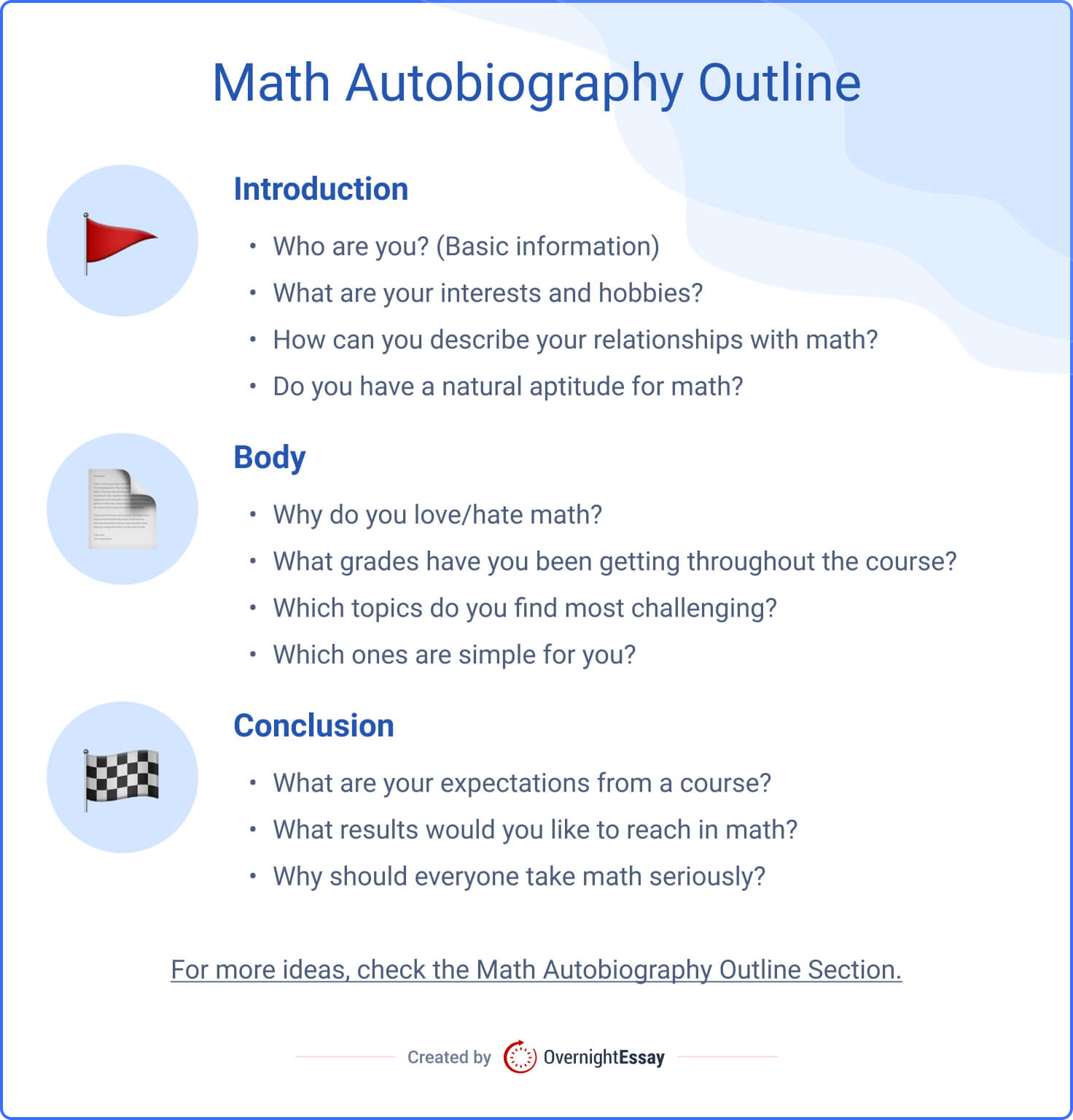

In our Relay teacher preparation curriculum for math teachers, we start by asking Relay students to write their own math autobiography. The exercise works like this:

- Relay students read this article by North Carolina State University researchers Allison W. McCulloch, Patricia L. Marshall, Jessica T. DeCuir-Gunby and Ticola S. Caldwall

- Relay students write their own math autobiography as well as a reflection on it, answering these questions:

- ~Consider the beliefs you named in the pre-work about what it means to teach math, who can learn math, and how math should be taught. How have your experiences with math informed how you currently think?

- ~ What do you want all students to believe about math based on their experience with you this year?

- ~What, if anything, do you need to change about your beliefs and mindsets in order to help all students believe this?

- ~What support might you need to shift these beliefs and mindsets?

- Relay students then share portions of their autobiographies and reflections in class as the basis of discussion, connection, and greater self-understanding

During this exercise, we often hear Relay students say things like, “I feel affirmed” or “Wow, I thought math just wasn’t for me, but I see now how I was taught that”, or “I didn’t realize that this previous experience caused trauma for me in math”. Students may describe how it felt to be the only person of color in advanced math classes, or other experiences related to how their identity - from race, to gender, disability, sexuality, religion, nationality, perceived family income, and more - led others to make assumptions about them and either limit or support their math confidence. For many, it is the first time really confronting the idea of trauma within school, and how they still carry the negative experiences today. But nearly everyone can also remember a teacher, parent, or mentor who connected with them, supported them, and turned them on the path to teaching. These are the "aha" moments that will shape teachers' classrooms for years to come.

If you are a school or school system leader and want to learn more about enrolling prospective teachers or currents in a teacher residency and/ or masters degree program, start on our Locations page to see the programs available in your state.

Dr. Kim Melgar

Kim Melgar is the Department Chair, Mathematics at Relay Graduate School of Education. This is her 15th year in what she describes as the best field - education. Kim taught middle school math and science and served as an instructional coach in the South Bronx before joining Relay, where she has also taught aspiring teachers as an adjunct and assistant professor. Kim is passionate about all things math, including how to create inclusive math classrooms through UDL, support multilingual learners, and help teachers and students see themselves as “math people.”

Sign up for our monthly newsletter for more expert insights from school and system leaders.

Math is for everyone

Mathematical, autobiography.

This math autobiography is the story of who I am as a mathematician. Everyone has a math journey, but every journey is unique. My math journey has had a profound impact on my identity — chance is that yours has too. When we share, we can better understand each other.

Before birth

That's my grandma. My mom is wearing pigtails, and next to her is my aunt. I come from a line of driven and entrepreneurial women. My mom graduated from college in Southern California and started her own business with my aunt. They owned a card shop for 14 years.

Meet my dad - he plays the guitar and likes to ride his bike. My brother and I are three years apart. Growing up I loved helping my brother with his math homework because people told me I was good at it. We went to the same K - 8 school in California. The teachers gave my brother points for acting out. He hated school.

Middle School

Gina and Audrey were my two closest friends in middle school. That's us! I was one of only two girls tracked for advanced math. I was proud, but embarrassed. What did I do? Did I deserve to be there more than my friends? They worked just as hard as I did — plus, they were way more popular than I. Th oughts from my middle school diary...

High School

This is my high school AB Calculus class. I took the class when I was a senior. I don't remember very much about Calculus, but I remember how the class made me feel. We were a community; evidently we took pictures together. We had fun solving problems. And our teacher encouraged us, gave us time, and validated our efforts. College math and pre-med track, here I come!

I graduated from college in 2014! Though the degree I'm holding is not the one you'd expect — Bachelor of Science in Anthropology. My first year of college courses was stacked - Chemistry, Chemistry Lab, Calc I, Calc 2, Biology. Then I failed my first chem exam. And then another. My confidence plummeted. I compared myself to others and decided that I wasn't smart enough. I am not a math person, I told myself. I was ready to get out of town and start something new.

New York City

New York City is where I learned courage, perseverance, and resilience. Before graduating college I applied for a position at Cornelia Connelly Center (CCC), an all-girls school in the Lower East Side that champions under-resourced students. I learned of the position from a high school alumni job alert. I interviewed, got the job, and a few months later, I moved to NYC. I'd serve as an Americorps Resident Teacher and I'd be teaching...math! CCC is not only where I rediscovered my love for math, but also discovered my love for teaching it!

Graduate School

I decided that I owed it to myself and to my students to learn how to teach math the right way. There's no right way, but while attending Fordham's Graduate School of Education I learned that math is about problem solving, using your brain, building up confidence, overcoming challenges, and ensuring equity. I was living and breathing math — it was awesome.

There is much to do to achieve justice. What can I do? What can I give? We all have gifts and talents to contribute, and this is mine. Teaching math is about breaking down systems that undermine equality and promoting confidence and compassion. It's a math revolution that's changing the world!

Famous Mathematicians

Mathematicians who changed history.

.css-34sej9{-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;display:block;margin-top:0;margin-bottom:0;font-family:Ramillas,Ramillas-weightbold-roboto,Ramillas-weightbold-local,Georgia,Times,Serif;font-size:2rem;line-height:1.2;font-weight:bold;}@media(max-width: 48rem){.css-34sej9{font-size:1.5rem;line-height:1.1;}}@media (any-hover: hover){.css-34sej9{-webkit-transition:color 0.3s ease-in-out;transition:color 0.3s ease-in-out;}.css-34sej9:hover{color:link-hover;}} Isaac Newton

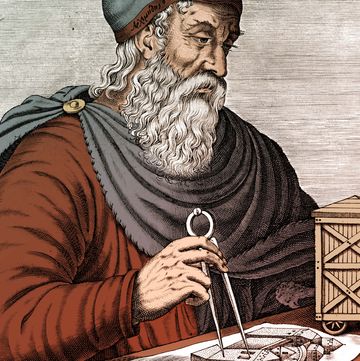

.css-1796pb7{-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;display:block;margin-top:0;margin-bottom:0;font-family:Gilroy,Gilroy-roboto,Gilroy-local,Helvetica,Arial,Sans-serif;font-size:1.125rem;line-height:1.2;font-weight:bold;color:#262626;text-transform:capitalize;}@media (any-hover: hover){.css-1796pb7{-webkit-transition:color 0.3s ease-in-out;transition:color 0.3s ease-in-out;}.css-1796pb7:hover{color:link-hover;}} Archimedes: The Mathematician Who Discovered Pi

Katherine Johnson

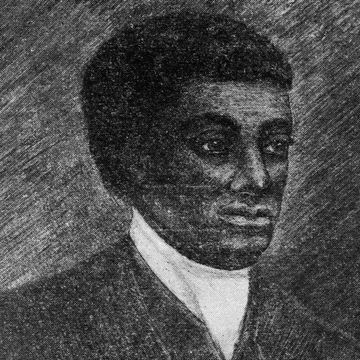

Benjamin Banneker

Kelly Miller

.css-1dmjnw1{position:relative;}.css-1dmjnw1:before{content:"";position:absolute;} .css-qaeylj{-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;display:block;margin-top:0;margin-bottom:0;font-family:Ramillas,Ramillas-weightbold-roboto,Ramillas-weightbold-local,Georgia,Times,Serif;font-size:2rem;line-height:1.2;font-weight:800;}@media(max-width: 48rem){.css-qaeylj{font-size:1.5rem;line-height:1.1;}}@media (any-hover: hover){.css-qaeylj{-webkit-transition:color 0.3s ease-in-out;transition:color 0.3s ease-in-out;}.css-qaeylj:hover{color:link-hover;}} Leonhard Euler .css-ha23m7{position:relative;}.css-ha23m7:after{content:"";position:absolute;}

More mathematicians.

.css-q53si6{-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;display:block;margin-top:0;margin-bottom:0;font-family:Gilroy,Gilroy-roboto,Gilroy-local,Helvetica,Arial,Sans-serif;font-size:1.125rem;line-height:1.2;font-weight:bold;color:#ffffff;text-transform:capitalize;}@media (any-hover: hover){.css-q53si6{-webkit-transition:color 0.3s ease-in-out;transition:color 0.3s ease-in-out;}.css-q53si6:hover{color:link-hover;}} Did This Newly Found Compass Belong to Copernicus?

The Solar Eclipse That Made Albert Einstein a Star

Archimedes: The Mathematician Who Discovered Pi

22 Famous Scientists You Should Know

Charles Babbage

Blaise Pascal

Leonhard Euler

- Our Mission

How Math Autobiographies Build Student Confidence

Incorporating a writing task into lessons can help students reflect on their work and see their skills in a new light.

As educators, we understand the crucial role of fostering confidence and a strong math identity in our students. We aim for each student to feel empowered and to see themselves as capable mathematicians every day. One effective way to nurture this mindset is by encouraging students to write a math autobiography. This reflective exercise invites them to consider their entire mathematical journey, which helps build confidence and reinforce the belief that they are inherently skilled at math.

Writing a math autobiography allows students to connect with each other through their mathematical experiences, identify their learning preferences (though those may change), and set future goals. It also highlights the times when they’ve stepped out of their comfort zone and found joy in the challenges they faced. Take a fifth grader, who discovered that “the more challenging math got, the more I loved it.” This realization helped her embrace challenges, because she knew she could enjoy them.

Similarly, another fifth grader reflected on his experience learning math during the pandemic. He found that virtual learning strengthened his perseverance, and he realized the power of his own resilience. By integrating reading, writing, and talking, this project guides students to develop a mathematical mindset.

Would Students Describe Themselves as Mathematicians?

Most students wouldn’t know how to respond, but we know mathematicians each have their own unique and beautiful math history. We can guide students by helping them find what they enjoy as a mathematician, how they hope to be perceived as a mathematician, and what concepts they’re passionate about. In our experience, students uncovered their math identity by using mentor texts and emotion graphs .

Mentor texts provide a mathematician’s perspective while allowing students to reflect on their own math journey. We chose to share mentor texts centered around the theme of perseverance. When we read Nothing Stopped Sophie , by Cheryl Bardoe, a fourth-grade mathematician stated, ”I forget that every person has trouble with math sometimes.”

We used emotion graphs to help students share their stories and experiences, which allowed them to realize what has shaped their mindset. This visual brainstorming task was the foundation for their math autobiography. As students thought about their math feelings throughout the years, memories flooded into their heads.

For our upper elementary students, we decided to use three different emojis on the y axis (happy, indifferent, and sad). The x axis listed the time period of their life. Most students had a “before school” category and then listed each grade level individually.

Planning on Paper and Identifying Relatable Themes

With these connections made, students were ready to plan their math autobiographies. Each student got six sticky notes to jot ideas related to their own history. When students read biographies, they look for certain elements (dates, challenges or obstacles, achievements, memorable moments, firsts and lasts, and connections or relationships).

They consider their own math history with each of these lenses, which gives them a collection of ideas to get writing. When students place each sticky note on a sheet of plain white paper, they’re able to view all of their ideas at one time and begin to plan their own autobiography. As they write, they can return to their sticky notes over and over again, weaving in each component. Students might plan ahead by adding a star to certain ideas that they want to include. They might also use check marks to keep track of what they’ve included so far.

In addition, having the sheet with these sticky notes at student workspaces will help teachers engage in writing conferences to help students get started when they’re stuck (and also help students rehearse ideas with partners before writing).

As students began writing, we noticed that each one crafted their own theme. One student reflected on his confidence in math when he wrote, “When I was in kindergarten, that’s when math started to play a role in my life” and “I realized it was not good to be overconfident in my math skills.”

Another student highlighted her perseverance in her math autobiography, saying, “I knew after trying and working hard, I could do it!” A student chose to focus his writing around connecting mathematics to world experiences when he wrote, “Math, I found, was everywhere—in Sesame Street , on cereal boxes, and in chess, my favorite board game—and so I grew as a mathematician.”

Instructional Strategies That Empower Mathematicians

Having the texts out while students are writing is key. Students quickly pointed out that the mentor texts they were reading had illustrations and pictures, so they included pictures in their own math autobiographies. Students wrote captions to convey the theme of their photographs.

When describing a candy photo he had pasted on his autobiography, a fifth grader wrote, “Mathematicians sort objects. On Halloween, me and my friends gave ‘values’ to every candy to make trading easier.” Mathematicians became motivated to teach others through their own math story. As a result, they became more confident in their math identity.

Showcase Student Projects in Different Ways

Some students created storybooks, others designed scrapbook pages, and still others wrote by hand, typed, or recorded their voice. Projects included real photographs, graphs, and math symbols in their design. A gallery walk displayed the math autobiographies so that everyone could move around to see the projects.

In a follow-up discussion, consider asking students:

- What’s the same about your work and someone else’s work? What is different?

- What kind of mathematicians are we? Can you finish this statement, “We’re the kind of mathematicians who…”?

- What can we do with math? How would you finish this sentence, “With math, we can…”? (Do this a few times in different ways.)

Embedding this writing project into any math classroom can help build confidence in students and promote reflection. Elementary mathematicians will craft a successful autobiography when they have time to reflect on their feelings around math, brainstorm memorable moments, and connect with other mathematicians.

Reflecting on their current feelings about their identity, the more they reflect, the more they’ll grow in and outside of the classroom.

Famous Scientists

Top Mathematicians

Here’s our alphabetical list of the most popular mathematicians or contributors to mathematics on the Famous Scientists website, ordered by surname.

Alphabetical List of Scientists

Louis Agassiz | Maria Gaetana Agnesi | Al-Battani Abu Nasr Al-Farabi | Alhazen | Jim Al-Khalili | Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi | Mihailo Petrovic Alas | Angel Alcala | Salim Ali | Luis Alvarez | Andre Marie Ampère | Anaximander | Carl Anderson | Mary Anning | Virginia Apgar | Archimedes | Agnes Arber | Aristarchus | Aristotle | Svante Arrhenius | Oswald Avery | Amedeo Avogadro | Avicenna

Charles Babbage | Francis Bacon | Alexander Bain | John Logie Baird | Joseph Banks | Ramon Barba | John Bardeen | Charles Barkla | Ibn Battuta | William Bayliss | George Beadle | Arnold Orville Beckman | Henri Becquerel | Emil Adolf Behring | Alexander Graham Bell | Emile Berliner | Claude Bernard | Timothy John Berners-Lee | Daniel Bernoulli | Jacob Berzelius | Henry Bessemer | Hans Bethe | Homi Jehangir Bhabha | Alfred Binet | Clarence Birdseye | Kristian Birkeland | James Black | Elizabeth Blackwell | Alfred Blalock | Katharine Burr Blodgett | Franz Boas | David Bohm | Aage Bohr | Niels Bohr | Ludwig Boltzmann | Max Born | Carl Bosch | Robert Bosch | Jagadish Chandra Bose | Satyendra Nath Bose | Walther Wilhelm Georg Bothe | Robert Boyle | Lawrence Bragg | Tycho Brahe | Brahmagupta | Hennig Brand | Georg Brandt | Wernher Von Braun | J Harlen Bretz | Louis de Broglie | Alexander Brongniart | Robert Brown | Michael E. Brown | Lester R. Brown | Eduard Buchner | Linda Buck | William Buckland | Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon | Robert Bunsen | Luther Burbank | Jocelyn Bell Burnell | Macfarlane Burnet | Thomas Burnet

Benjamin Cabrera | Santiago Ramon y Cajal | Rachel Carson | George Washington Carver | Henry Cavendish | Anders Celsius | James Chadwick | Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar | Erwin Chargaff | Noam Chomsky | Steven Chu | Leland Clark | John Cockcroft | Arthur Compton | Nicolaus Copernicus | Gerty Theresa Cori | Charles-Augustin de Coulomb | Jacques Cousteau | Brian Cox | Francis Crick | James Croll | Nicholas Culpeper | Marie Curie | Pierre Curie | Georges Cuvier | Adalbert Czerny

Gottlieb Daimler | John Dalton | James Dwight Dana | Charles Darwin | Humphry Davy | Peter Debye | Max Delbruck | Jean Andre Deluc | Democritus | René Descartes | Rudolf Christian Karl Diesel | Diophantus | Paul Dirac | Prokop Divis | Theodosius Dobzhansky | Frank Drake | K. Eric Drexler

John Eccles | Arthur Eddington | Thomas Edison | Paul Ehrlich | Albert Einstein | Gertrude Elion | Empedocles | Eratosthenes | Euclid | Eudoxus | Leonhard Euler

Michael Faraday | Pierre de Fermat | Enrico Fermi | Richard Feynman | Fibonacci – Leonardo of Pisa | Emil Fischer | Ronald Fisher | Alexander Fleming | John Ambrose Fleming | Howard Florey | Henry Ford | Lee De Forest | Dian Fossey | Leon Foucault | Benjamin Franklin | Rosalind Franklin | Sigmund Freud | Elizebeth Smith Friedman

Galen | Galileo Galilei | Francis Galton | Luigi Galvani | George Gamow | Martin Gardner | Carl Friedrich Gauss | Murray Gell-Mann | Sophie Germain | Willard Gibbs | William Gilbert | Sheldon Lee Glashow | Robert Goddard | Maria Goeppert-Mayer | Thomas Gold | Jane Goodall | Stephen Jay Gould | Otto von Guericke

Fritz Haber | Ernst Haeckel | Otto Hahn | Albrecht von Haller | Edmund Halley | Alister Hardy | Thomas Harriot | William Harvey | Stephen Hawking | Otto Haxel | Werner Heisenberg | Hermann von Helmholtz | Jan Baptist von Helmont | Joseph Henry | Caroline Herschel | John Herschel | William Herschel | Gustav Ludwig Hertz | Heinrich Hertz | Karl F. Herzfeld | George de Hevesy | Antony Hewish | David Hilbert | Maurice Hilleman | Hipparchus | Hippocrates | Shintaro Hirase | Dorothy Hodgkin | Robert Hooke | Frederick Gowland Hopkins | William Hopkins | Grace Murray Hopper | Frank Hornby | Jack Horner | Bernardo Houssay | Fred Hoyle | Edwin Hubble | Alexander von Humboldt | Zora Neale Hurston | James Hutton | Christiaan Huygens | Hypatia

Ernesto Illy | Jan Ingenhousz | Ernst Ising | Keisuke Ito

Mae Carol Jemison | Edward Jenner | J. Hans D. Jensen | Irene Joliot-Curie | James Prescott Joule | Percy Lavon Julian

Michio Kaku | Heike Kamerlingh Onnes | Pyotr Kapitsa | Friedrich August Kekulé | Frances Kelsey | Pearl Kendrick | Johannes Kepler | Abdul Qadeer Khan | Omar Khayyam | Alfred Kinsey | Gustav Kirchoff | Martin Klaproth | Robert Koch | Emil Kraepelin | Thomas Kuhn | Stephanie Kwolek

Joseph-Louis Lagrange | Jean-Baptiste Lamarck | Hedy Lamarr | Edwin Herbert Land | Karl Landsteiner | Pierre-Simon Laplace | Max von Laue | Antoine Lavoisier | Ernest Lawrence | Henrietta Leavitt | Antonie van Leeuwenhoek | Inge Lehmann | Gottfried Leibniz | Georges Lemaître | Leonardo da Vinci | Niccolo Leoniceno | Aldo Leopold | Rita Levi-Montalcini | Claude Levi-Strauss | Willard Frank Libby | Justus von Liebig | Carolus Linnaeus | Joseph Lister | John Locke | Hendrik Antoon Lorentz | Konrad Lorenz | Ada Lovelace | Percival Lowell | Lucretius | Charles Lyell | Trofim Lysenko

Ernst Mach | Marcello Malpighi | Jane Marcet | Guglielmo Marconi | Lynn Margulis | Barry Marshall | Polly Matzinger | Matthew Maury | James Clerk Maxwell | Ernst Mayr | Barbara McClintock | Lise Meitner | Gregor Mendel | Dmitri Mendeleev | Franz Mesmer | Antonio Meucci | John Michell | Albert Abraham Michelson | Thomas Midgeley Jr. | Milutin Milankovic | Maria Mitchell | Mario Molina | Thomas Hunt Morgan | Samuel Morse | Henry Moseley

Ukichiro Nakaya | John Napier | Giulio Natta | John Needham | John von Neumann | Thomas Newcomen | Isaac Newton | Charles Nicolle | Florence Nightingale | Tim Noakes | Alfred Nobel | Emmy Noether | Christiane Nusslein-Volhard | Bill Nye

Hans Christian Oersted | Georg Ohm | J. Robert Oppenheimer | Wilhelm Ostwald | William Oughtred

Blaise Pascal | Louis Pasteur | Wolfgang Ernst Pauli | Linus Pauling | Randy Pausch | Ivan Pavlov | Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin | Wilder Penfield | Marguerite Perey | William Perkin | John Philoponus | Jean Piaget | Philippe Pinel | Max Planck | Pliny the Elder | Henri Poincaré | Karl Popper | Beatrix Potter | Joseph Priestley | Proclus | Claudius Ptolemy | Pythagoras

Adolphe Quetelet | Harriet Quimby | Thabit ibn Qurra

C. V. Raman | Srinivasa Ramanujan | William Ramsay | John Ray | Prafulla Chandra Ray | Francesco Redi | Sally Ride | Bernhard Riemann | Wilhelm Röntgen | Hermann Rorschach | Ronald Ross | Ibn Rushd | Ernest Rutherford

Carl Sagan | Abdus Salam | Jonas Salk | Frederick Sanger | Alberto Santos-Dumont | Walter Schottky | Erwin Schrödinger | Theodor Schwann | Glenn Seaborg | Hans Selye | Charles Sherrington | Gene Shoemaker | Ernst Werner von Siemens | George Gaylord Simpson | B. F. Skinner | William Smith | Frederick Soddy | Mary Somerville | Arnold Sommerfeld | Hermann Staudinger | Nicolas Steno | Nettie Stevens | William John Swainson | Leo Szilard

Niccolo Tartaglia | Edward Teller | Nikola Tesla | Thales of Miletus | Theon of Alexandria | Benjamin Thompson | J. J. Thomson | William Thomson | Henry David Thoreau | Kip S. Thorne | Clyde Tombaugh | Susumu Tonegawa | Evangelista Torricelli | Charles Townes | Youyou Tu | Alan Turing | Neil deGrasse Tyson

Harold Urey

Craig Venter | Vladimir Vernadsky | Andreas Vesalius | Rudolf Virchow | Artturi Virtanen | Alessandro Volta

Selman Waksman | George Wald | Alfred Russel Wallace | John Wallis | Ernest Walton | James Watson | James Watt | Alfred Wegener | John Archibald Wheeler | Maurice Wilkins | Thomas Willis | E. O. Wilson | Sven Wingqvist | Sergei Winogradsky | Carl Woese | Friedrich Wöhler | Wilbur and Orville Wright | Wilhelm Wundt

Chen-Ning Yang

Ahmed Zewail

Worlds of Words

International collection of children’s and adolescent literature, biographies of mathematicians.

By Susan Corapi, Trinity International University, Deerfield, IL