- NEWSLETTER SIGN UP

The Research Committee is dedicated to encouraging, supporting, and promoting a broad base of research that is grounded in diverse methodologies. By providing information to the public and the membership, the committee promotes standards of art therapy research, produces a registry of outcomes based research, and honors professional and student research activity.

Art therapy priority research areas, focusing research efforts in the following areas:.

- Outcome/efficacy research

- Art therapy and neuroscience

- Research on the processes and mechanisms in art therapy

- Art therapy assessment validity and reliability

- Cross-cultural/multicultural approaches to art therapy assessment and practice

- Establishment of a database of normative artwork across the lifespan

SEEKING TO ADDRESS THE FOLLOWING RESEARCH QUESTIONS:

- What interventions produce specific outcomes with particular populations or specific disorders?

- How does art therapy compare to other therapeutic disciplines that do not include art practice in terms of various outcomes?

- How reliable and valid is any art therapy assessment?

- What neurobiological processes are involved in art making during art therapy?

- To what extent do a person’s verbal associations to artwork created in art therapy enhance, support, or contradict?

- What are ways of making art therapy more effective for clients of different ethnic and racial backgrounds?

SUGGESTED POPULATIONS TO RESEARCH:

- Psychiatric major mental illness

- Medical/Cancer

- At-risk youth in schools

BIBLIOGRAPHIC SEARCH TOOL

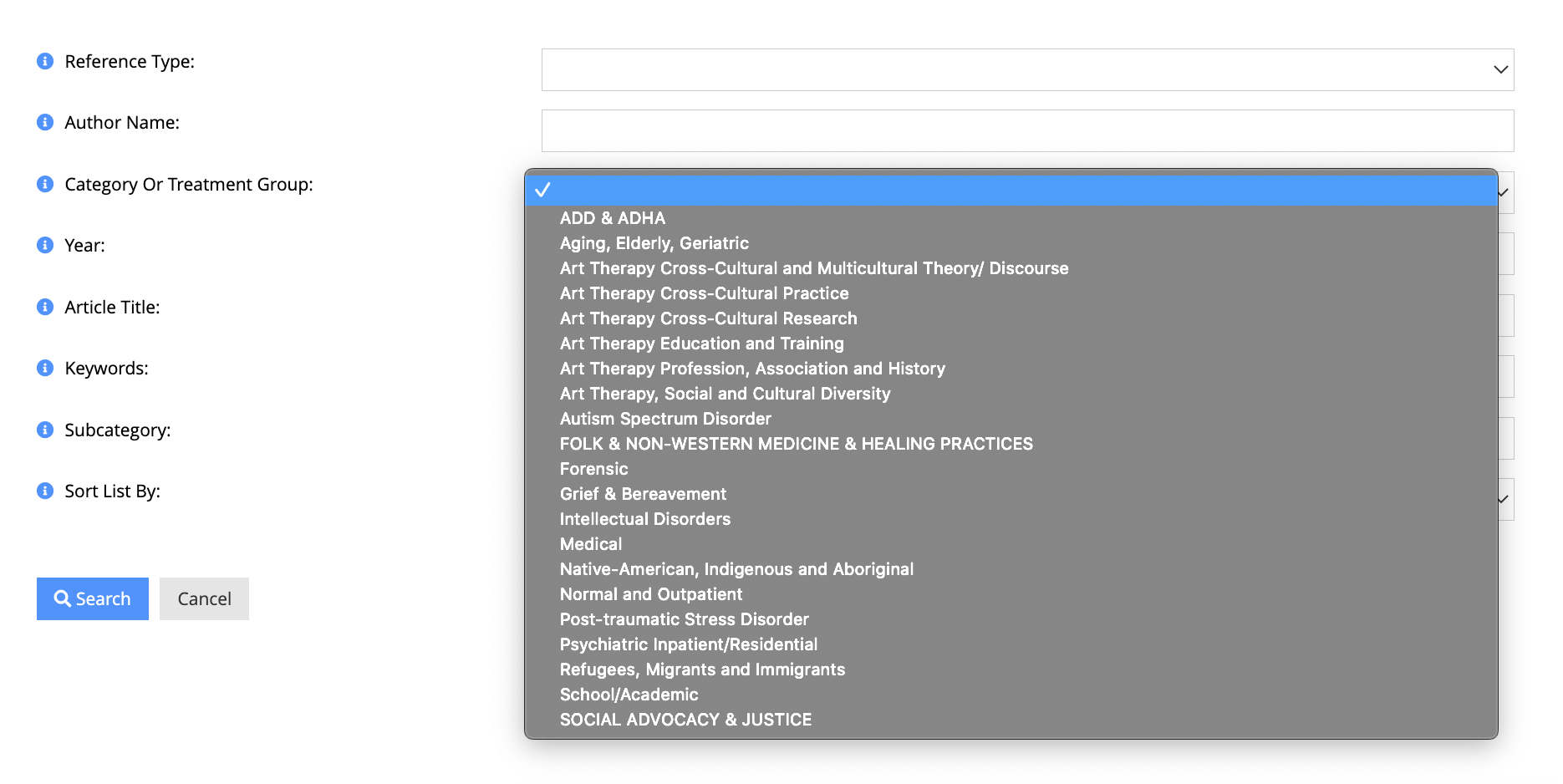

AATA’s Art Therapy Bibliographic Search Tool allows you to find listings of art therapy publications and theses from FOUR research sources: the Art Therapy Outcomes Bibliography, the Art Therapy Assessment Bibliography, the Multicultural Committee Selected Bibliography and Resource List, and the National Art Therapy Thesis and Dissertation Abstract Compilation.

The Art Therapy Bibliographic Search Tool enables you to search bibliographic entries based on one or all of the following characteristics: author name, category/treatment group, keywords, title, reference type, and year of publication.

AATA Member Exclusive: All AATA members have the benefit of viewing more details about each database entry, including abstracts, topics, and comments!

- < Previous

Home > Art Therapy Print Theses > 207

Art Therapy | Master's Theses in Print

A qualitative study with art therapists on the use of art as self-care in addressing vicarious trauma, author name.

Rachel A. Votaw , Notre Dame de Namur University

Graduation Date

Spring 2011

Document Type

Master's Thesis

Document Form

Degree name.

Master of Arts in Marriage and Family Therapy

Degree Granting Institution

Notre Dame de Namur University

Program Name

Art Therapy

Lisa Bjerknes, MD, MBA

First Reader

Laury Rappaport, PhD, ATR-BC

Second Reader

Richard Carolan, EdD, ATR-BC

This study sought to discover how art therapists use art for self-care to prevent vicarious trauma.

To expand upon current research, the researcher conducted a qualitative study through facilitating semi-structured interviews with ten art therapist participants and recording their experiences in using art as self-care to address vicarious trauma. Seven themes emerged, which included the therapists experiencing the following: extemalization, connecting with Art Therapists, engagement in spirituality, gaining access to insight and meaning, bringing the unconscious into conscious awareness, transformation, and finally, an improved mood. This study highlights the benefits art therapists experience through artmaking to prevent and manage vicarious trauma.

Since September 27, 2021

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS

- Collections

- Disciplines

- Expert Gallery

Author Corner

- Thesis Style Guides

- Art Therapy at Dominican University of California

- Dominican Scholar Feedback

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Review article, art as therapy in virtual reality: a scoping review.

- 1 GET Lab, Department of Multimedia and Graphic Arts, Cyprus University of Technology, Limassol, Cyprus

- 2 Arts and Humanities Division, New York University Abu Dhabi, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

This scoping review focuses on therapeutic interventions, which involve the creation of artworks in virtual reality. The purpose of this research is to survey possible directions that traditional practices of art therapy and therapeutic artmaking could take in the age of new media, with emphasis on fully immersive virtual reality. After the collection of papers from online databases, data from the included papers were extracted and analyzed using thematic analysis. The results reveal that virtual reality introduces novel opportunities for artistic expression, self-improvement, and motivation for psychotherapy and neurorehabilitation. Evidence that artmaking in virtual reality could be highly beneficial in therapeutic settings can be found in many aspects of virtual reality, such as its virtuality, ludicity, telepresence capacity, controlled environments, utility of user data, and popularity with digital natives. However, deficiencies in digital literacy, technical limitations of the current virtual reality devices, the lack of tactility in virtual environments, difficulties in the maintenance of the technology, interdisciplinary concerns, as well as aspects of inclusivity should be taken into consideration by therapy practitioners, researchers, and software developers alike. Finally, the reported results reveal implications for future practice.

1 Introduction

Given the rapid technological advancements, the steady decrease in prices of technological apparatus, and the continuous permeation of information technology in various disciplines, Adams et al. (2008) predict that, during the current millennium, digital art will be transcending its aesthetic role by adapting in multiple applications as a transdisciplinary medium. The present review touches upon the ubiquity of digital art and focuses on the fields of mental and physical healthcare. In this regard, of special interest is Virtual Reality (VR), a multipurpose communication medium ( Biocca and Levy, 2013 ) that intersects with the domains of both artistic expression ( Kim and Lee, 2021 ) and wellbeing ( Alqahtani et al., 2017 ; Montana et al., 2020 ). During the introductory part of this review, key concepts, which later contribute to a holistic understanding of the topic, are introduced. The present review approaches the integration of VR in practices relevant to art and therapy by presenting the state of the art, gaps in current knowledge, and potential future directions.

A VR system is characterized by its level of immersion, also referred to as sensory immersion, that has been described in the literature as the degree to which natural sensorimotor contingencies can be supported and engaged by the virtual simulation ( Kim and Biocca, 2018 ; Slater, 2018 ; Berkman and Akan, 2019 ). Immersion depends on the characteristics of the apparatus and optimizing immersion levels is supported by various VR studies, which conclude that high immersion is an antecedent of the sensation of “being present” in a Virtual Environment (VE) ( Slater et al., 2009 ; Slater and Sanchez-Vives, 2016 ).Eliciting presence is a crucial element of a VR experience as it indicates how natural sensorimotor contingencies ostensibly are and therefore how likely it is for the user to act in the VR environment as if in real life ( Slater and Sanchez-Vives, 2016 ), so that the experience becomes “organic, user-driven, and different for everyone” ( Bailenson, 2018 , p. 223) An example relevant to drawing/writing would be the visual stimuli of a pen matching the motor action of grasping it in the perceivably proper way ( Farmer et al., 2018 ) The naturalness in which the user’s body is perceived to be moving in order to form the action of grasping that pen, also contributes to the sensorimotor contingencies. Here, when the user embodies a virtual whole body or a body part, which they experience from a first-person perspective and onto which movements are mapped in real-time and in synchrony with the user’s real movements, this gives rise to the illusion of body ownership ( Maselli and Slater, 2013 ; Christofi et al., 2020 ). In VR storytelling, presence and embodiment together have been previously described as “narrative storyliving” ( Vallance and Towndrow, 2022 ).

Interestingly, the virtual bodies (or avatars) that act as surrogate bodies during VR embodiment are found to have capabilities which go beyond their technical capabilities. In cases when immersive VR applications allow for bodily customization, a psychosocial layer is added to VR embodiment, which may enhance the sense of body ownership by enabling role-play and the free expression of various behaviors and attitudes ( Bertrand et al., 2021 ). This influence on behaviors and attitudes which stems from the dispositional characteristics of the embodied avatar, is known as the “ Proteus Effect” ( Yee and Bailenson, 2007 ) and it has been shown to even lead to higher cognitive changes, such as, for example, embodying a child body causing adult VR users to overestimate the size of virtual objects ( Banakou et al., 2013 ), embodiment in a different race body leading to changes in implicit racial attitudes ( Maister et al., 2015 ; Banakou et al., 2020 ), or embodying a stereotypically empathic woman instigating empathy ( Hadjipanayi and Michael-Grigoriou, 2022 ). Embodying avatars in fully immersive VR can also lead to the acquirement of soft-skills, where for instance, embodying the avatar of Sigmund Freud was found to help VR users offer more sound counselling advice compared to embodying the avatar of a therapy client ( Osimo et al., 2015 ; Slater et al., 2019 ).

Contrary to fully immersive VR, non-immersive VR systems only offer a window on the virtual world, without this essentially being a disadvantage ( Alqahtani et al., 2017 ). A Window on World (WoW) type of VR is commonly projected through regular monitor screens. Non-immersive VR systems are less expensive and easier to use than immersive VR systems ( Bamodu and Ye, 2013 ). Desktop video games that include procedurally generated environments are classic examples of non-immersive VR ( Alqahtani et al., 2017 ). Semi-immersive VR systems are hybrid systems that aim to maintain the simplicity and low cost of non-immersive VR systems while emulating the advantages in sensorimotor contingencies that are successfully achieved by fully immersive VR systems ( Bamodu and Ye, 2013 ). This type of system occupies a portion of the physical environment and virtually transforms it to serve a specific purpose. For example, the therapeutic system for motor and cognitive rehabilitation that is introduced by Maggio et al. (2022) transforms an empty room into a virtual playground that can extend to the floor and the walls of the room to match the preferred design of specific rehabilitation exercises.

VR is a transdisciplinary medium that intertwines with subject areas relevant to both artistic creation and healthcare. However, artistic creation in VR is more commonly associated with aspects of creativity, entertainment, and culture rather than wellbeing ( Rubio-Tamayo et al., 2017 ; Pissini, 2020 ). This scoping review relies on gathering literature pieces for which all the relevant subject areas of “VR,” “art,” and “therapy” intersect. This is particularly challenging due to the broad terminology surrounding “art”, which is colloquially defined as any form of self-expression. For this reason, it is imperative that art-related aspects are further contextualized, while also keeping in mind that in this scoping review art is viewed through the lens of therapy and healing. in other words, the population included in this review is “VR users,” the concept is “the creation of visual artworks in immersive VR,” and the context is “therapy.” Notably, this review focuses on the visual aspect of artmaking, as it is favored by VR technology, and to-date there is a gap in the VR literature regarding non-visual therapeutic artmaking projects. In order to address the multi-dimensional role of art as a therapeutic practice, it is essential to first address the differences between 1) expressive arts therapy and art therapy and 2) therapeutic artmaking and art therapy.

Four distinct categories (disciplines) of expressive arts therapy are widely recognized among practitioners and are known as 1) art therapy, 2) music therapy, 3) dramatherapy, and 4) dance movement therapy ( Song et al., 2019 ). Disciplines of expressive arts therapy can sometimes be used adjunct to other affective, cognitive, or psychomotor approaches, forming tailored therapeutic interventions that meet the diverse needs of each cohort group ( Malchiodi, 2020 ). As an example, Mishina et al. (2017) introduced a set of playground activities into an expressive arts therapy intervention with troubled adolescents whose emotional states improved after the intervention. These playground activities included rhythmic movements and image creation, among other activities, that formed a multimodal expressive arts therapy approach. In the cognitive domain, art therapy elements are commonly combined with cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) to provide trauma-based treatment. In many cases, drawing or symbolically reenacting a traumatic memory under the guidance of a therapist helped clients come to terms with themselves regarding their feelings of anger, helplessness, and self-blame ( Pifalo, 2007 ; Sarid and Huss, 2010 ). Regarding the psychomotor domain, an improvement of psychomotor development in children with speech pathologies was observed after introducing a finger puppet theater approach (including the creation of puppets) in their correctional pedagogy training ( Arkhipova and Lazutkina, 2022 ). It is apparent that psychomotor therapy is well complemented by expressive arts therapy, as they share the element of active participation into activities that promote kinesthetic abilities, cognitive processes, and personal development ( Haeyen et al., 2021b ; Arkhipova and Lazutkina, 2022 ). In order to limit the scope of this review on the healing qualities of creating a visual artwork, this review focuses solely on art therapy. Art therapy includes practices such as drawing, coloring, painting, collaging, sculpting, and allows the use of any media and materials that can be utilized to create visual artworks of symbolic value ( Moon, 2011 ).

There are various definitions of art therapy as different schools of thought in psychology attribute different definitions and sometimes different psychotherapeutic goals to it. Three of the most notable approaches to art therapy are: humanistic, psychodynamic, and cognitive-behavioral. Humanistic art therapy is founded on the active participation of the client and the facilitation of the therapist in the exploration of the client’s artwork and its underlying narratives ( Farokhi, 2011 ). The psychodynamic approach in art therapy focuses on the unconscious of the human mind and borrows concepts from analytical and archetypal psychology which is associated with symbolic images ( Malchiodi, 2011 ). Cognitive-behavioral art therapy focuses on the attitude change of the client through visually externalizing problematic situations and identifying coping strategies ( Rosal, 2018 ). Overall, art therapy, as an expressive arts therapy discipline, most commonly refers to a triangular psychotherapeutic relationship between therapist, client, and artwork. Schaverien (2000) proposes that what is referred to as “art therapy” per se in the field of psychology, encompasses two other distinct forms of therapy, namely “art psychotherapy” and “analytical art psychotherapy.” The differences between these forms lie in the dynamic within the triangular psychotherapeutic relationship. Schaverien (2000) distinguishes “art therapy” as a process, in which the relationship between client and artwork is the main focus, whereas in “art psychotherapy” it is the relationship between client and therapist that is most emphasized, and in “analytical art psychotherapy” all three components of the relationship constellate equally.

Therapeutic artmaking, which can also be found in literature as “Art as Therapy,” contrary to art therapy, is a low-intensity intervention for which the involvement of a therapist is considered a non-prerequisite. The inherently beneficial properties of artmaking and the inclination of patients to turn artmaking into a coping mechanism against illness have been evident for centuries but scientific research on the healing aspects of art is fairly recent ( Farokhi, 2011 ). Immersive engagement with artmaking stimulates the senses, directs the artist’s mind to the present time, and employs multiple cognitive processes, such as problem-solving, differentiation, and decision-making ( Rosal, 2018 ). Also, contrary to art therapy, therapeutic artmaking can be characterized as a recreational experimentation with art materials, in which the overarching goal for the client is the creation of visually appealing artworks ( Angheluta and Lee, 2011 ; Worden, 2020 ).

Some argue that therapeutic artmaking is a form of art therapy in which the psychoanalytic value of creating art is attenuated in favor of focusing on the inherent healing qualities of creating art ( Czamanski-Cohen, et al., 2014 ). Others believe that art therapy and therapeutic artmaking should be considered as two completely different practices because of ethical considerations, as art therapy in contrast to therapeutic artmaking, requires the guidance and expertise of healthcare professionals ( Angheluta and Lee, 2011 ). Despite the differences between the two therapeutic approaches, therapeutic artmaking and art therapy share a similar therapeutic intent. As Worden (2020) elucidates, self-expression in art therapy opts for making an individual able to work through past traumas among other psychological issues, whereas therapeutic artmaking opts for evoking a feeling of catharsis, encouraging socialization, honing technical skills that cater to visual self-expression, and increasing self-esteem. All the above are positive outcomes that affect wellbeing. Admittedly, therapeutic artmaking and artistic expression as a psychotherapy, rehabilitation, or counseling intervention, are used complementary to each other to various degrees ( Farokhi, 2011 ; Malchiodi, 2020 ). Despite the main focus of the present scoping review being VR and therapeutic artmaking, the discipline of art therapy in this context cannot be omitted, because of the indicated interweaving between therapeutic artmaking and art therapy.

The topics of VR in therapeutic artmaking and art therapy remain vastly understudied, even though the groundwork that underscores potential uses of VR in different forms of psychotherapy has been laid during previous decades ( Riva, 2005 ). For instance, virtual reality exposure therapy (VRET), which refers to the systematic habituation of patients to stimuli reminiscent of traumatic memories through VR, is the most studied form of psychological VR intervention and is widely endorsed as a valid alternative to traditional psychotherapy ( Deng et al., 2019 ). The efficacy of VRET was evident since the infancy of VR ( Hodges et al., 1995 ), despite the low quality of graphics or level of human-computer interaction. Nowadays VRET is deemed as an equally effective treatment to in vivo interventions for a variety of disorders, such as specific phobias and anxiety disorders ( Carl et al., 2019 ; Mozgai et al., 2020 ) among others. With the exception of VRET, the number of studies addressing VR in psychotherapy is still limited ( Frewen et al., 2020 ) and considering the continuous changes in the technological landscape, definitive conclusions about the efficacy of art therapy interventions in VR cannot yet be drawn.

Furthermore, multiple commercial applications for wellbeing can be found across platforms and devices, but their efficacy is under scrutiny. Wagener et al. (2021) , after conducting a systematic application review, raised some critical points about the mismatch between the well-grounded theoretical background behind VR wellbeing applications and their subpar outcomes when it comes to practice. As they point out, most VR wellbeing applications unilaterally focus on specific wellbeing aspects and lack the flexibility of customization as well as opportunities for individual expression. Additionally, VR applications support users in identifying and reflecting upon their affective states, but they do so to a minimal degree. This reveals the need for further discourse on the potential and current limitations of practices about VR for wellbeing, which should derive insight from multiple disciplines for better understanding the intricacies of VR wellbeing. To this end, a scoping review is the most appropriate type of knowledge synthesis because it is most efficient in conveying the breadth of a variety of practices in a particular research area ( Brien et al., 2010 ) and can help clarifykey interdisciplinary concepts and definitions, as well as identify types of evidence and knowledge gaps in the literature.

Presently, and to the best of our knowledge, no literature reviews specifically focusing on the subject of immersive VR and art as a therapeutic practice exist. Pissini (2020) , who focuses on VR as a medium for artmaking, acknowledges the importance of studying VR practices in relation to the healthcare field, even though Pissini’s indicated work is deliberately directed towards other interesting aspects of immersive VR artmaking, such as embodied creativity. One literature review most relevant to the present paper titled “Technology use in art therapy practice: 2004 and 2011 comparison” by Orr (2012) , reviewed art therapy practice to every available technology at the time (between 2004 and 2011), and the author concluded that there was a gap between technological advancements and art therapy training, which further bred ethical limitations to the use of advanced technology in art therapy. Aspects of the ever-changing technology should be taken into account for the effective renewal of therapeutic practice, as old models of practice show signs of eventually becoming obsolete ( Salles et al., 2020 ). Especially after the COVID-19 pandemic and the mobility restrictions imposed on therapists and clients alike, therapists were forced to reevaluate their methods and find ways to best utilize technology to mitigate the negative effects of the pandemic on the normality of treatment procedures ( Feniger-Schaal et al., 2022 ). Long-distance VR interventions are deemed as suitable alternatives to face-to-face interventions in the case of treatments that require more “acting” instead of “talking,” such as psychomotor therapy, because of the experiential nature of using VR ( Haeyen et al., 2021b ). This scoping review revisits the technological gap indicated by Orr but purely focusing on VR, with the objective to assess the therapeutic utility of art-related practices in VR and provide guidelines for future research.

The question sought to be answered is twofold: 1) how has VR been integrated into practices relevant to art therapy and therapeutic artmaking? This review seeks to analyze how relevant studies define and juxtapose VR and artmaking in the context of therapy. Answering this first inquiry, while bearing in mind the overarching goals that each relevant study implies, can shed some light on the different forms in which advancing technology and artistic expression can manifest in a therapeutic setting; 2) how applicable are VR interventions for achieving therapeutic goals in relation to traditional art therapy and therapeutic artmaking practices? Through this inquiry, VR art-related interventions are being explored and contrasted to the well-established interventions that are traditionally used in art therapy and therapeutic artmaking. This inquiry is viewed from both the perspective of the client/user and the therapist/researcher to identify possible limitations and challenges.

2 Research methodology

2.1 eligibility criteria, 2.1.1 inclusion criteria.

The inclusion criteria were 1) academic manuscripts published between 2011 and the end of the data collection process, which ended in November 2022. VR and computer graphics have changed drastically during the last decade hence academic articles published before 2011 were omitted. The reason for this drastic change in the past decade is the sudden introduction of cost-effective VR head-mounted displays ( Harley, 2020 ). 2) Academic manuscripts on the topic of VR, wellbeing, art therapy and therapeutic artmaking. Out of the four disciplines of expressive arts therapy mentioned above, the present scoping review focuses only on the discipline of art therapy, as defined in the introduction. Concepts that are universal to all expressive arts disciplines are also considered to be relevant. Under the scope of the present review, both art therapy and artmaking are accepted as relevant interventions. The relevance of the interventions is appraised based on the inclusion of artistic expression that results in the creation of visual artworks via visuomotor integration. 3) Peer-reviewed academic manuscripts (research articles, quantitative and qualitative studies, opinion pieces, and essays).

2.1.2 Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria were 1) Manuscripts which focus solely on VR therapy techniques. One of the prime examples of VR therapy that is distinctively different from VR art therapy is VRET. 2) VR-related manuscripts that focus on the sensory aspect of art when the virtual experience allows only a passive participation of virtual reality users (i.e., watching or observing a VE). Being exposed to a VR simulation that is purposefully designed for inducing wellbeing outcomes is a method that is typically employed for psychological healing through aestheticism ( Moller et al., 2020 ) and spirituality ( Pendse et al., 2016 ). Therefore, the combination of animated images, ambient sounds, and other stimuli, which is used to provide a therapeutic experience without involving psychomotor activity, is more related to VR therapy than the practices of art therapy or artmaking. 3) VR-related manuscripts which refer to VR as its non-immersive counterpart (WoW) only, or demonstrate digital applications with the premise of exocentric navigation only. Non-immersive VR interventions are excluded due to technical qualities that result in differences in the overall experience compared to fully immersive VR systems ( Rubio-Tamayo et al., 2017 ; Slater, 2018 ). 4) VR-related manuscripts which include art therapy or therapeutic art-making practices but do not draw any associations between VR and art therapy or VR and therapeutic artmaking other than being parts of a holistic therapeutic approach.

2.2 Information sources

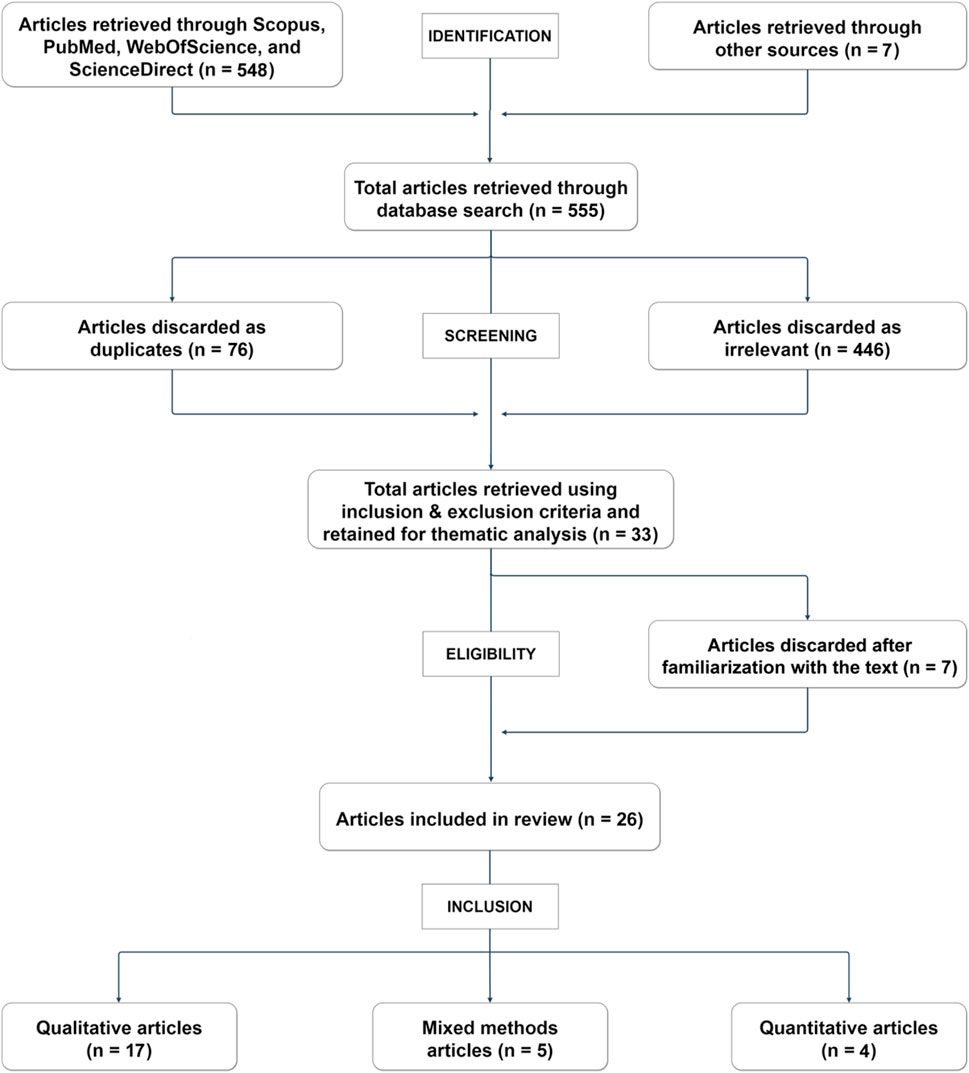

The searching process was carried out mainly through 4 databases, namely Scopus (138), Web Of Science (80 in the topic of “virtual reality and art therapy”), PubMed (67), ScienceDirect (263 in the subject areas of psychology, social sciences, computer science, neuroscience, and nursing and health professions). All 548 papers were sorted and then a second search from Google Scholar was carried out. From Google Scholar, 7 additional papers were found that were identified as potentially relevant. Within the first 6 search result pages of Google Scholar, only 4 potentially relevant papers were found, as most relevant articles had already been detected by previous search engines and had already been included for screening. Therefore, the total number of publications that potentially met the required criteria was finalized at 555. No additional articles were retrieved afterwards using incremental searching.

2.3 Search methods

The keywords used for the search engines to retrieve the 555 publications were “virtual reality art therapy.” In the stage of the publication retrieval and screening process, the usage of the keyword “art” required additional caution. From the first few searching sessions, it was apparent that the keyword “art” was inviting a multitude of irrelevant publications in the search results. The main reason for this outcome was that “art” in scientific literature is an excessively used term, with its most common usage found in the phrase “state of the art.” Therefore, the exclusion of the phrase “state of the art” from the search engines has significantly increased the quality and decreased the load of search results. For example, the search strategy for the Google Scholar search engine that was performed on 09 November 2022 included the search query: ((virtual reality AND art* AND therapy) -“state of the art”). Another issue caused by the keyword “art” is that the acronym “ART” is also found to be excessively used in areas of healthcare and science, technology, engineering, arts, mathematics education (STEAM). This issue has been resolved through the screening process, where the relevance of the retrieved publications has been appraised.

2.4 Selection of sources of evidence

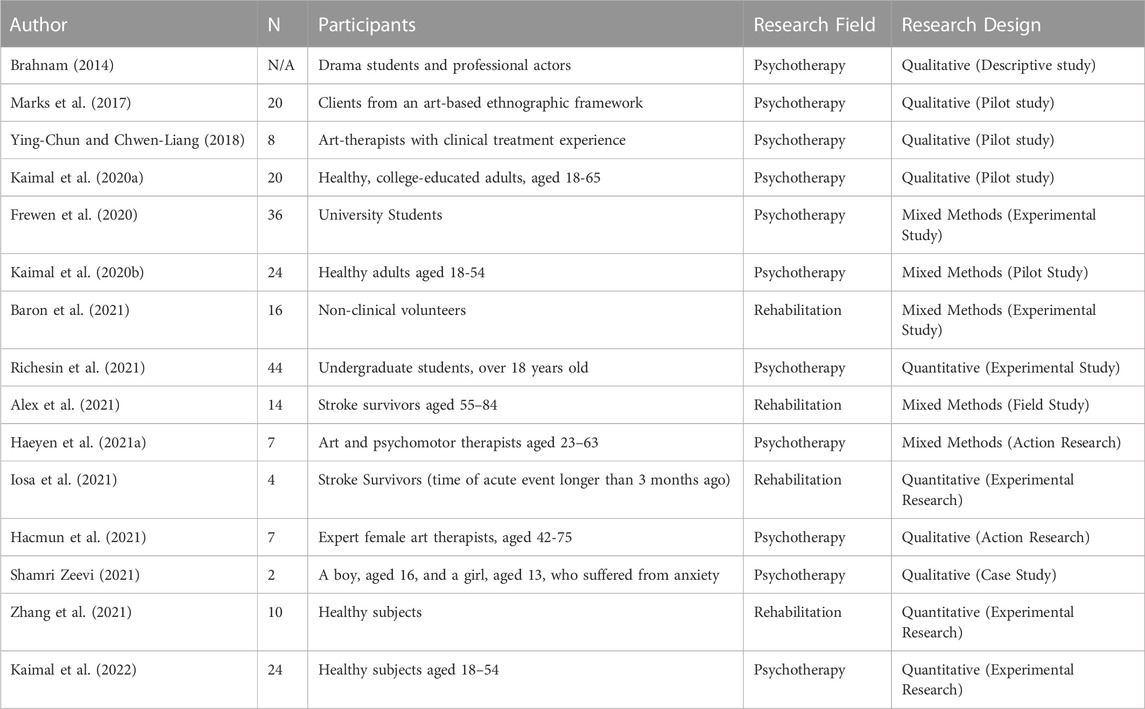

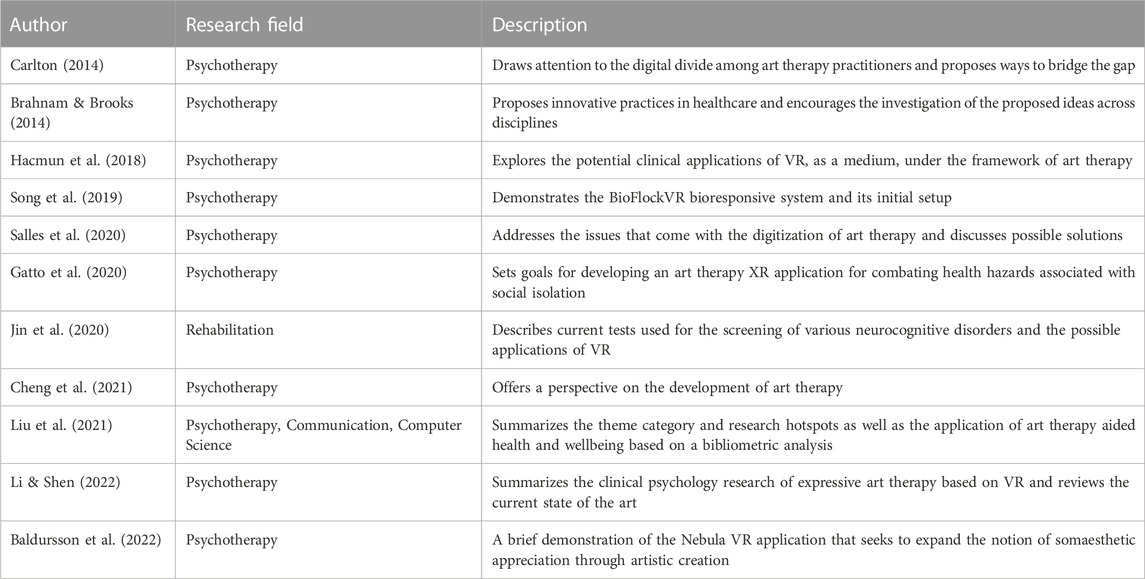

All 555 papers were screened by title and abstract. The screening and selection of the manuscripts was carried out on Rayyan ( www.rayyan.ai ), a web tool designed to help researchers carry out knowledge synthesis projects ( Ouzzani et al., 2016 ). After all the sources were uploaded to the web tool, the 555 publications were manually categorized as duplicates (76), irrelevant (446), and relevant (33) according to the criteria and processes discussed. Some aspects of the inclusion and exclusion criteria were easier to pinpoint with precision once the authors were familiarized with the 33 selected papers. After a thorough examination of the theoretical background and if applicable the employed apparatus and methodology of the 33 papers, it became apparent that the relevance of 7 papers should be reconsidered. In 3 out of the 7 papers the human-computer interaction involved a 2D virtual interface instead of a VE, but their intervention was labelled as “virtual reality” regardless that VEs are integral components of immersive VR. In 2 out of 7 papers, the references to VR and the technology used during interventions were too vague and could be exclusively concerning a WoW approach or even be irrelevant to VR as defined in this review. In another paper, the study intervention involved solely mixed reality (MR) technology. The remaining 1 out of 7 papers describes a human-computer interaction model that generates artworks solely based on the user’s affective state, without any psychomotor activity being evidently required. With these 7 papers abiding to the exclusion criteria, the 26 remaining papers consisted of mixed methods (5), qualitative (17), and quantitative (4) research publications ( Figure 1 ); 15 of the 26 included publications consist of empirical studies ( Table 1 ). The rest of the papers consist of academic articles that have aims other than the production of novel empirical knowledge ( Table 2 ).

FIGURE 1 . Flow diagram of the article retrieval process according to the PRISMA statement methodology.

TABLE 1 . Empirical studies included for analysis.

TABLE 2 . Academic articles that synthesize empirical evidence and are included for analysis.

2.5 Data charting process

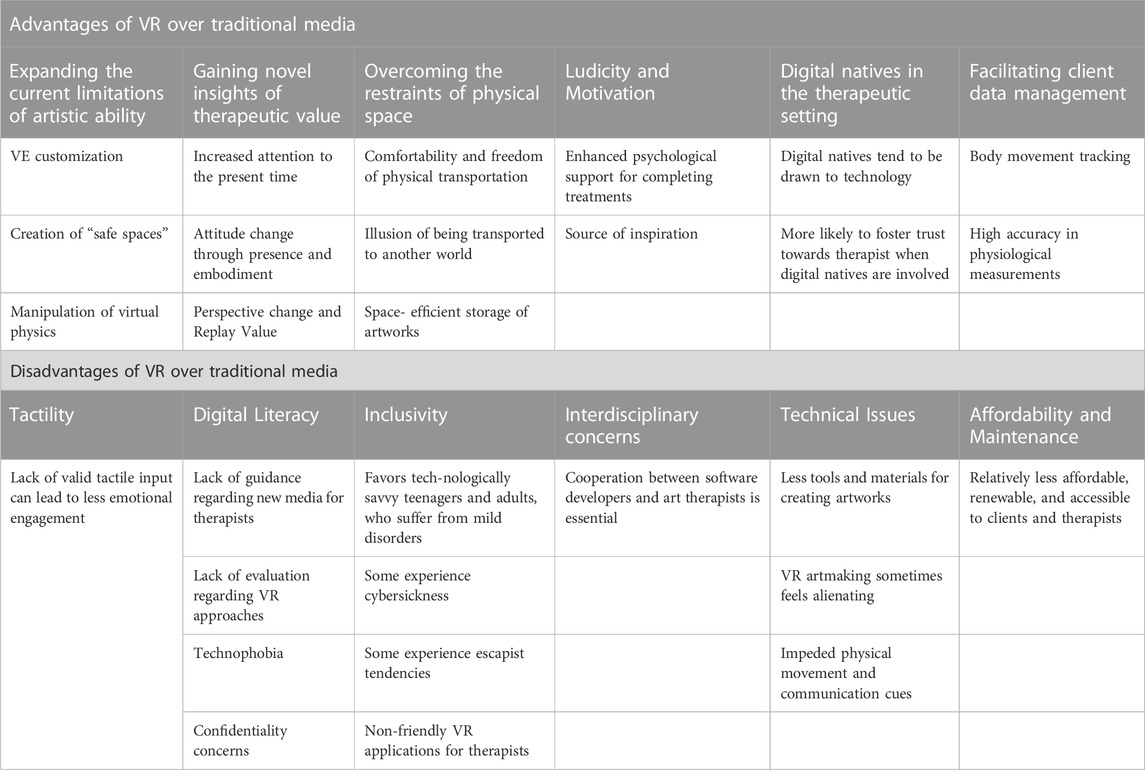

After familiarization with the texts and the transcription process, the extracted transcriptions were recorded in a table format based on the content of the papers and more specifically, the advantages and disadvantages of VR over traditional media in the context of therapeutic artmaking and art therapy. Whenever applicable, the primary results, main conclusion, as well as methodological approaches, including apparatus, study purpose, data collection and analysis were also collected. The tables were tested by the reviewer team for refinements and to ensure that all relevant data were gathered. Therefore, data pertaining to the different approaches towards art and VR technology were also included. An inductive thematic analysis was used for the collected data to define the most common recurring themes. The data charting process was manually carried out while two reviewers were permitted to simultaneously edit the transcribed data on the shared tables. The emergent themes became apparent after one of the reviewers used color coding on the transcribed data that helped in discerning patterns and aggregating the data into meaningful categories.

2.6 Data items

The generated codes regarding the methodological approach of studies revealed that there are two main treatment categories, namely psychological and neurorehabilitation treatments. The generated codes regarding advantages and disadvantages of VR over traditional media in the context of therapeutic artmaking and art therapy revealed 6 main themes for each. The occurred themes regarding advantages were recognized as:

A.i. “Expanding the current limitations of artistic ability and expression in clinical settings through VR”

A.ii. “Gaining novel insights of therapeutic value through VR.”

A.iii. “Overcoming the restraints of physical space”

A.iv. “Ludicity and motivation”

A.v. “Digital natives in the therapeutic setting”

A.vi. “Facilitating client data management”

The occurred themes regarding disadvantages were recognized as:

D.i. “Tactility”,

D.ii. “Digital literacy”

D.iii. “Inclusivity”

D.iv. “Interdisciplinary concerns”

D.v. “Technical limitations”

D.vi. “Affordability and maintenance.”

2.7 Synthesis of results

Thematic synthesis was used to formulate a descriptive analysis of the findings. In the results, reports on study logistics and the identified approaches regarding the use of art therapy and therapeutic artmaking in VR can be found. Also, advantages and disadvantages, limitations, and challenges of digitizing art therapy with the use of VR are presented in both narrative and table format ( Table 3 ). This scoping review was synthesized based on the PRISMA ScR checklist guidelines ( Tricco et al., 2018 ).

TABLE 3 . Summary of the advantages and disadvantages, challenges, and limitations in digitizing art therapy and therapeutic artmaking by using the VR medium.

An overview of the 26 publications indicates that the concept of using VR as an artmaking tool in therapy context has been nascent in the past decade (2011–2022 included) and it has recently grown in trend, with 73.07% ( n = 19) of the included papers being published between 2020 and 2022. A bibliometric analysis, which is conducted by Liu et al. (2021) and is spanning over a period of 75 years, confirms-through the co-occurrence of keywords used in the context of art therapy-that VR technology is becoming increasingly relevant with art therapy aided health and wellbeing research. Also, 57.69% ( n = 15) of the included papers involve experimental research with human participants, with the remaining 42.30% ( n = 11) consisting of opinion pieces, demos, and essays. All studies made use of a VR apparatus, most commonly mentioned being the Oculus, the HTC VIVE, and the Windows Mixed-Reality VR/MR headsets. Additionally, some of these studies included hardware complementary to VR, such as motion capture devices (MOCAP) for body tracking. Regarding the software, both custom and commercial VR drawing applications were used, with the most widely used one being the commercial application Google Tilt Brush. Participants fell under the category of either “patient” who suffers from psychological or physical conditions, “therapist,” “university student,” or “healthy subject,” and the research objectives suggest high heterogeneity among studies.

3.1 Approaches to art therapy and therapeutic artmaking

This subsection constitutes general observations drawn from the reviewed papers, which do not necessarily conform to the acceptable definitions of “art therapy” or “therapeutic artmaking” as presented in the introductory section. The presentation of these observations provides a brief overview of the therapeutic approaches and the state of the art. In the reviewed papers, the terms of art therapy and therapeutic artmaking, sometimes clearly distinguished and other times used interchangeably, are used to describe a wide variety of treatments. In general, all the reviewed treatments operate on the basis that creative endeavors can generate emotions and incentives for both mental and physical wellbeing. Art, and more specifically art materials and media, are viewed as intermediaries between the realms of ideas and reality, which are experienced through the individual’s senses. Specifically for VR, therapeutic activities such as painting, drawing, coloring, collaging, and sculpting, take a different form in the 3D environments, which could also vary (e.g., digital twins of an art therapy room or ostensibly infinite 3D canvases).

The authors identify two main categories, namely psychological and neurorehabilitation treatments, in which theoretical approaches to art diverge.

3.1.1 Psychological treatment approach

Most of the reviewed papers that are relevant to the field of psychology define their psychotherapeutic treatments in terms of art therapy, as a mental health profession and, more specifically, an expressive arts discipline. Art therapy is applied as a dynamic emotional therapy where art materials, the creative process, and the produced artwork serve as means of self-exploration and self-expression, in order to create personal change. In this context, the most widely mentioned theoretical influence is the psychodynamic perspective (Jungian psychology). This is often put in practice as depth psychology-based psychotherapy, in which the unconscious is brought to the surface thanks to the symbolic potential of artistic self-expression and, as a result, suppressed feelings are being revealed ( Song et al., 2019 ). During this process, creating art and the psychotherapeutic relationship are elements of higher psychotherapeutic value than the final product of artistic creation. In analytical art psychotherapy, the patient’s artwork is examined by the therapist to better understand the unconscious mind ( Schaverien, 2000 ; Cheng et al., 2021 ).

Principles from other schools of thought are also adapted to the theoretical framework of the reviewed papers. Through the lens of CBT, art facilitates the communication of the individual’s conceptual structures in a different way than verbal communication does, thus often providing alternative and illuminating perspectives to both the individual and the therapist. Within the triangular psychotherapeutic relationship, the artwork represents a subjective experience that is externalized by the client, in a way that the visualized mental relations of the client become more explorable and often reveal conflicting perspectives ( Hacmun et al., 2021 ). The “open studio approach” to art therapy is an approach that many of the reviewed papers find befitting of VR art therapy because of the ludic nature of current VR art-related applications. The creation of the “safe space” is a prominent practice in art therapy. Drawing the “self,” the “problem,” and “coping mechanisms,” such as a “sanctuary,” is found to significantly alleviate psychological trauma ( Frewen et al., 2020 ).

A strong implication that is pointed out is that artistic expression, even without being accompanied by verbal reflection or any psychotherapeutic intervention, could still be a source of psychological healing. Artmaking is viewed as an innate human characteristic and one of the most primitive forms of self-expression, which is continuously evolving as a result of technological advancement by encompassing new expressive capabilities ( Hacmun et al., 2018 ). Art is deployed as a source of solidarity, inspiration, and a sensation of security during times of crisis ( Gatto et al., 2020 ).

3.1.2 Neurorehabilitation treatment approach

Regarding rehabilitation treatments, it is revealed that VR drawing applications are often used by patients who suffer from post-stroke motor impairments or minor neurocognitive disorders. Under this framework, digital artmaking works as an effective treatment for rehabilitation because it values the enjoyability of the treatment, as it activates reward pathways of the brain, while supporting physical, cognitive, and emotional healing ( Kaimal et al., 2020a ). It also allows patients (e.g., stroke survivors) who encounter difficulties with speaking to express themselves non-verbally ( Alex et al., 2021 ; Zhang et al., 2021 ). The most recent findings in the field of VR artmaking suggest that different approaches to artmaking activate different brain regions ( Kaimal et al., 2022 ). Comparisons of prefrontal cortex activations between a visual tracing task of a drawing and creative self-expressive artmaking indicated significant differences. Distinctively, the implication is that creative self-expression, contrary to the tracing task, induces transient hypofrontality, a state of the brain that is associated with relaxation and the inhibition of self-reflective processes. This suggests that different artmaking approaches could be used for achieving specific treatment goals.

From the perspective of neuroaesthetics, the field which engages with the perceptual, cognitive, and emotional aspects involved during an aesthetic experience, the element of the artwork is an apt addition in the neurorehabilitation practice. A reason for this is that creation, or even mere observation, of artworks and the practice of rehabilitation are both tightly associated with sensorimotor activity, which is found to be cognitively concomitant to the emotive expressions of painted figures (e.g., the figures in “The Creation of Adam” by Michelangelo) ( Iosa et al., 2021 ). Artworks are found to neurobiologically induce motivation and affective arousal, which are fundamental aspects of neurorehabilitation, along with active participation and treatment intensity.

3.2 Advantages of VR over traditional media in therapeutic artmaking and art therapy

3.2.1 expanding the current limitations of artistic ability and expression in clinical settings through vr.

The authors of the reviewed papers appear to advocate for a potential revolutionization in the field of art therapy, because of the advent of VR. Especially in psychotherapy, VR’s increasing repertoire of tools for creative self-expression enables clients to better convey their conceptual structures to therapists and researchers by transforming and customizing the virtual environments where the therapeutic process takes place. The ability to tailor virtual environments according to the client’s psychological disorder and the psychotherapeutic approach of the therapist could more easily provide both clients and therapists or researchers a common ground of communication ( Hacmun et al., 2018 ).

The most notable contributions of artistic expression in VR psychotherapy are found to be the evocation of familiarity and safety in clients, as well as enhanced self-reflection and meditation. A common practice that is observed is the creation of a “safe space,” which is created by the client according to the client’s personal preference to serve as an emotional refuge. Safe spaces, which are usually in the form of houses or caves, have been used in psychotherapy practice long before VR but the ability to step into your artworks, which is exclusive to VR technology, expands the frontiers of this practice ( Frewen et al., 2020 ). VR safe spaces are most beneficial for people suffering with trauma and post-traumatic stress, as safe spaces allow them to gather and sort their thoughts and feelings out while being at one with themselves ( Brahnam, 2014 ). However, the creative ways the clients can express themselves through VR could go far beyond the concept of safe spaces and drastically vary, as clients continue to experiment with VR as a creative outlet.

In VR neurorehabilitation practices that involve artistic creation, as derived from the reviewed papers, artistic technique with emphasis on precision of movement seems to have an equally prominent, if not more prominent role, to that of artistic expression. Rehabilitation practices through VR technology are applicable because VR technology has evolved to allow a sufficiently high precision of movement, compared to the physical world. VR has the capacity of allowing patients who suffer from impaired mobility to make bold and expansive brush strokes in the virtual world by making simple gestures in the physical world ( Baron et al., 2021 ). This result can be achieved by accordingly adjusting the movement translation of the virtual avatar to the patient’s range of motion. In similar ways, the laws of physics in VR environments can be “adjusted” to the needs and comfort of the patients. In this sense, the VR medium offers a high level of independence to the user ( Alex et al., 2021 ).

3.2.2 Gaining novel insights of therapeutic value through VR

Throughout the reviewed papers, the concept of experiential discovery through VR is prevalent. From the client’s perspective, VR is a medium that is assumed to be effective in inducing emotional responses and stimulating cognition. Exposure in immersive VEs is found to decrease distracting thoughts (mind wandering) and increase properties required for eliciting attention, awareness, and self-reflectiveness. Some of these properties are presence and embodiment, which are important factors for changing implicit attitudes ( Hacmun et al., 2018 ; Gatto et al., 2020 ). From the therapist’s perspective as well as that of the researcher, VR enables the exploration of the client’s mind as an equivalent of exploring virtual worlds ( Marks et al., 2017 ). During the analysis, two of the most notable VR qualities that were indicated as salient contributors in gaining novel insights of therapeutic value in VR are enhanced perspective change and replay value (or playback).

The affordance of perspective change encompasses the user’s perspective but also the ability of virtual object manipulation. In this instance, “virtual objects” refers to the clients’ artistic creations, which play the role of externalized concepts. VR offers the ability of viewing objects from any angle, including from within the artwork, and the ability of scaling the size of objects ( Hacmun et al., 2018 ; Li and Shen, 2022 ). The viewing of such objects from different vantage points is a practice that is already employed in psychotherapy and VR can drastically enhance this practice. Through coming across these different perspectives, clients are given the opportunity to deconstruct and reconstruct their conceptual structures, such as the concept of the self ( Hacmun et al., 2018 ).

The ability to replay a recorded psychotherapy session and attempt to reassess the client’s behavior within the virtual environment allow the psychotherapist or researcher and the client to have a more accurate and clearer understanding of the client’s therapy progress ( Brahnam, 2014 ). In other words, the digital affordance of replaying each digital brushstroke during art therapy in VR can enhance reflection. Replay value is one of the many VR qualities that require ongoing study ( Carlton, 2014 ).

3.2.3 Overcoming the restraints of physical space

The reviewed papers often focus on the use of VR headsets that can be used in a patient’s daily life, even outside of the care services. The portability of VR allows the patients to engage in therapy in the comfort of their home, where no time or transportation restrictions apply ( Baron et al., 2021 ). However, even when it is mandatory for patients to either visit a clinical facility or remain hospitalized, VEs of immersive VR have the ability to transfer patients outside of the sterile physical environment of a clinical setting and “place” them somewhere more idyllic, thus providing inspiration and positive emotions. Furthermore, VEs are designed for the exploration of imaginal worlds and their design is in accordance with the central tenets of the creative processes in art therapy ( Gatto et al., 2020 ). This transportability through immersive VR allows the stimulation of the proprioceptive and vestibular senses without the need of a sizeable physical space and thus distinguishes immersive VR from other digital media. Equally important is the fact that VR artworks can be efficiently stored and retrieved for further editing without occupying physical space, unlike materials and artworks produced by traditional art therapy practices ( Baron et al., 2021 ).

3.2.4 Ludicity and motivation

The reviewed papers support the idea that ludic play and gamification models, which are compatible with VR technology, assist in establishing therapeutic interventions that drive the patient’s engagement while maintaining autonomy. Physical therapy requires time commitment while the therapeutic process is often arduous for the patient. Even so, the inherent qualities of VR applications motivate patients to keep exercising and instill in them the willingness to gain mastery over the new media ( Baron et al., 2021 ). As no hard-and-fast rules for artmaking exist, VR artmaking is often viewed as an activity for relaxation and recuperation with no substantial impact on the physical world and free from the fear of failure or committing mistakes ( Li and Shen 2022 ). A study that focused on the physiological measures of VR users during artmaking in a 3D virtual space, found a reduction in anxiety and negative affect ( Richesin et al., 2021 ). Also, the same study suggests that the aspect of having an end goal during a VR simulation, such as completing an artwork, plays an important role when aiming for specific wellbeing related outcomes. Another aspect worth mentioning is the element of inspiration. Guided imagery, as an art therapy practice, requires imagination, which patients sometimes lack. VR immersive environments may be able to provide the inspiration necessary for unimaginative patients to evoke concrete ideas and possibilities more easily while sparking the interest in further exploring these ideas ( Kaimal et al., 2020a ; Li and Shen, 2022 ).

3.2.5 Digital natives in the therapeutic setting

As technology has permeated every facet of current society, the group of digital natives is continuously increasing due to the succession of generations. Therapists and researchers from the reviewed papers suggest that most digital natives are accustomed to interacting with technology, including VR, and interaction with technology is intuitive and enjoyable to them. As digital natives grow up in a technologically abundant environment, their minds become wired towards best utilizing the technological resources at their disposal ( Marks et al., 2017 ). This is the main reason digital natives are often alienated by traditional media (i.e., art materials), which they often find too messy or even obsolete. In a psychotherapeutic setting, digital natives tend to feel more comfortable expressing themselves through means other than a conversation or a paper-and-pencil drawing. VR interventions are found to be great alternative options of therapy in cases of clients rejecting traditional therapeutic methods. Therefore, VR assists in building rapport between clients, especially younger ones, and their therapists, by enriching the psychotherapeutic relationship ( Shamri Zeevi, 2021 ; Li and Shen, 2022 ). The use of new media, such as VR, in art therapy paves the way for further cultural exploration of digital natives and their interaction with technology ( Carlton, 2014 ).

3.2.6 Facilitating client data management

The suitability and assistance of VR technology in data collection and data representation is occasionally mentioned in the reviewed papers. VR is widely portrayed as a technology that allows easier tracking of body movements, which on one hand is necessary for creating art and at the same time constitutes a crucial element of art therapy ( Ying-Chun and Chwen-Liang, 2018 ). Additionally, body movement is often viewed as a form of expression in and of itself. Especially for VR neurocognitive tests, the high ecological validity that is provided by VR, in comparison to their paper-and-pencil counterparts, makes the data collected through VR arguably more valid. This is because VR provides the possibility of safely reenacting activities of daily living in VR as if in real life ( Jin et al., 2020 ). Also, digital technologies can reach a large audience of patients and gather patient data that could lead to more informed decisions by both healthcare professionals and researchers. Data from multiple VR trials can be easily gathered and compiled, leading to reassessment and optimization of VR tests ( Jin et al., 2020 ; Salles et al., 2020 ).

3.3 Disadvantages of VR over traditional media in therapeutic artmaking and art therapy

3.3.1 tactility.

With the field of VR haptics still evolving, the reviewed papers point out that VR is insufficient in providing a similar level of sensory stimulation and tactility as traditional media in art therapy. VR technology replaces tangible art materials with virtual ones, which could be characterized as orderly and often unfamiliar, and this is especially true for clients who perceive traditional art therapy materials as more intuitive and easier to use ( Alex et al., 2021 ). The joy of “holding my completed artwork in my hands,” is a quality that seems to be exclusive to physical artworks ( Hacmun et al., 2018 ). The deprivation of sensory cues through the absence of sufficient tactility stimulation in digital media often brought up in the reviewed papers, is one of the main factors that prevent some art therapists from considering the adoption of not only VR but also other digital media in their psychotherapeutic treatments ( Haeyen et al., 2021a ).

3.3.2 Digital literacy

Most art therapy practitioners lack training in VR technology and their resources for employing VR are sparse. In addition, art therapy practitioners tend to consider traditional media in art therapy as more therapeutic than new media, even though there is no clear evidence of this belief ( Carlton, 2014 ). According to the reviewed papers that addressed these issues, the lack of systematic training in new media for art therapists discourages the use of VR technology in art therapy practice. Specifically, art therapists are hesitant about the use of VR technology, as they acknowledge the lack of technological expertise in the field and have no clear direction in how to incorporate digital materials in their psychotherapeutic treatments, which are often highly experiential and active by nature ( Brahnam, 2014 ; Haeyen et al., 2021a ). Consequently, the lack of technological expertise results in a lack of evaluation regarding the psychotherapeutic efficiency of the digital tools available and many practitioners arrive to the arbitrary conclusion that new media are inefficient compared to traditional media ( Salles et al., 2020 ). Some of the authors use the term “technophobia” to describe this phenomenon of repulsion towards new media. Technophobia is observed in practitioners and clients alike, as many of them admittedly perceive digital media and digital art as lesser than their traditional counterparts ( Jin et al., 2020 ). An important factor that caters to technophobia in clients is the uncertainty regarding confidentiality and privacy of the client’s data accumulated during VR sessions ( Marks et al., 2017 ). All things considered, and especially the obscurity of new media in art therapy graduate programs, there is also the issue that art therapy practitioners who are unfamiliar with new media may never come across the possibility of adopting VR in their psychotherapeutic practice. However, even when practitioners overcome any possible bias and consider the possibility of adopting VR, they are often intimidated by the steep learning curve and other limitations.

3.3.3 Inclusivity

From the analysis of the reviewed papers, it can be concluded that art therapy in VR is less inclusive than traditional art therapy. First and foremost, there is a digital divide among art therapy clients and those who are technology-savvy are more likely to find benefit in VR interventions ( Shamri Zeevi, 2021 ). Secondly, the use of VR by children who are below the age of twelve or thirteen is not recommended for safety reasons, according to policies of VR headset manufacturers ( Ying-Chun and Chwen-Liang, 2018 ). This age restriction specifically applies to VR gaming, so children younger than twelve could potentially make a healthy use of VR headsets when supervised by adults. Even so, this age restriction implies that VR usage requires the user to have a level of cognitive development that is higher than the one required for the usage of traditional art therapy media. Also, VR interventions are unsuited for people with major neurocognitive disorders, acute motor and vestibular issues, and those who are prone to headache and nausea, as the phenomenon of cybersickness seems to be a glaring problem. In addition, VR interventions are unsuited for people who suffer from hallucinations and those who struggle to distinguish between reality and fantasy ( Kaimal et al., 2020a ; Jin et al., 2020 ). The restrictions mentioned so far do not apply to traditional art therapy and even when clients seem to qualify for the use of VR, the opposite could be proven during therapy. For example, the client could be prone to distraction by the VR intervention. In this case, the client could easily diverge from the course of therapeutic practice, especially if the art therapy facilitator is negligent or unfamiliar with new media ( Carlton, 2014 ). It is difficult to predict a client’s response to a VR intervention before the beginning of the intervention as VR qualities are experienced differently by each user. Some users do not experience the illusion of presence–being in a different place than the physical one when using VR—but others experience this illusion too intensely. Regarding the latter case, patients may use VR interventions for unhealthy escapism instead of coping with real life problems ( Kaimal et al., 2020a ). This adds an extra layer of complexity in deciding whether VR interventions are benefactory to all clients. Issues with inclusivity can be encountered from the side of the art therapy practitioner too. This view stems from the observation that most applications of VR in psychotherapy are used in the context of CBT, while other approaches, such as the humanistic approach and their practitioners are obscured. Similarly, VR could be considered as impractical for some groups of art therapy practitioners who endorse art therapy practices other than the ones offered by most of the available VR applications ( Brahnam, 2014 ). It should be mentioned that practitioners often develop VR-applicable techniques based on various concepts and strategies (e.g., technical eclecticism, Ludic Engagement Designs for All) that could potentially cater to both the expertise of each practitioner and the unique needs of each client ( Brahnam and Brooks, 2014 ; Frewen et al., 2020 ).

3.3.4 Interdisciplinary concerns

Despite the attempts to digitize art therapy and therapeutic artmaking, more research is needed to ensure the satisfaction of therapists and clients alike regarding the efficacy of digital interventions. This seems to be true for both psychological and rehabilitation treatments in VR, according to the reviewed papers. Physical rehabilitation in its traditional form has long been proven as an effective method of regaining functionality, whereas more studies are needed to determine the extent to which VR rehabilitation is efficient ( Baron et al., 2021 ). Digital applications are notorious for widespread misinformation and, with applications in the healthcare industry being no exception, clinicians point out the significant risk of applications dictating therapy through digital means ( Salles et al., 2020 ). Clinicians stipulate that digital applications relevant to therapy should be flexible enough to be customized for each client instead of being adapted to the developers’ process of working. For example, art therapy is often misunderstood as the notion of simply making art for psychological healing or the notion that the completed artwork of the patient is a solid projection of the patient’s psychopathology. When these misconceptions are transferred to the digital realm, there is the danger of excluding the framework that makes art therapy therapeutic, such as aspects of the triangular psychotherapeutic relationship and the subtle expressions during the construction of an artwork ( Salles et al., 2020 ).

3.3.5 Technical limitations

Admittedly, the current state-of-the-art VR software for artmaking offers less sophisticated artistic capabilities for creative expression than traditional art therapy media. The range of tools and materials, which are available for drawing, painting, sculpting, and collage in VR, is comparatively more limited than the physical gamut of art tools and materials ( Kaimal et al., 2020a ).). Also, it can prove difficult for the client to convey some of the intentional or unintentional messages to the therapist or researcher due to the physical form of VR technology. By drawing examples from the reviewed papers, a common problem is that VR head-mounted displays hide the facial characteristics of the client and disallow eye-contact between the client and the physical environment, including the therapist ( Shamri Zeevi, 2021 ). In the case of physical rehabilitation, the rigidity, agelessness, and multi-perspective angles of 3D digital strokes often alienate patients, whose location tends to remain constant, due to them being inert ( Alex et al., 2021 ). A common issue for therapists and researchers is that they can only have a glimpse of the therapeutic process through a 2D projection of a computer screen, which makes monitoring the VR user ( Shamri Zeevi, 2021 ). Overall, the reviewed papers suggest that it is easier to evaluate social cues and initiate social interactions during traditional methods rather than VR interventions.

3.3.6 Affordability and maintenance

According to Carlton (2014) , there is a lack of affordability, renewability, and accessibility to new media compared to traditional media in art therapy. The issue of high cost in VR equipment and the development of specialized software applications, compared to traditional art therapy media and materials, is found in many of the reviewed papers. Specialized VR systems are usually available to psychotherapists only if provided by healthcare organizations that have their own IT departments where limitations, such as cost and maintenance, are most viably mitigated ( Brahnam, 2014 ).

4 Discussion

The findings indicate that the progress of VR technology is facilitating the use of VR in therapeutic practices relevant to the creation of artworks to a degree that allows a plethora of possibilities for innovation. In the field of psychotherapy, 3D digital brush strokes are employed to facilitate communication between client and therapist or researcher but also to act as building blocks for “safe spaces,” work as colorful mood regulators for reducing anxiety, and unravel empirical insight for self-improvement. The 3D digital strokes of Tilt Brush were only an instance of how therapeutic artmaking and art therapy manifest in VR. New forms of artistic expression are beginning to emerge through VR, such as generating graphics using biomarkers or simple gestures ( Song et al., 2019 ; Baldursson et al., 2022 ). Some of these art forms are made available thanks to the combination of VR with other technologies, such as the Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCI), where brain activity data can be easily collected and decoded to create control signals for virtual objects ( Coogan and He, 2018 ). One of the least expected findings was the emergence of digital drawing techniques in the field of neurorehabilitation. Rehabilitation strategies that involved the creation of traditional artworks were proposed by Skinner and Nagel (1996) , however the literature on the subject has been scarce for over 2 decades. Recent studies suggest that new media alleviate physical constraints from in-therapy motor-impaired patients to the point of allowing them to paint digital artworks and even “recreate” classical masterpieces in the form of a simulation ( Iosa et al., 2021 ; Zhang et al., 2021 ). For example, researchers used VR technology to simulate the illusion of painting classical art masterpieces, designed for the neuroaesthetic stimulation of patients with an affected upper limb, and found a “Michelangelo effect” arising ( Iosa et al., 2021 ). These imitations are neurologically comparable to performing the observed activity, akin to a virtual simulation, hence the term “embodied simulation” could be used ( Buk, 2009 ; Finisguerra et al., 2021 ). It is argued that the capabilities of computer simulations in inducing neuroplasticity are best utilized by the technology of VR, which provides patients with interactive, stimulatory and ecologically valid VEs ( Cheung et al., 2014 ). The sense of presence, which is induced within an immersive VR simulation, accounts for a bountiful allocation of cognitive resources that are relevant to motor control and is estimated to be one of the main factors that make VR technology especially suitable for rehabilitation ( Slobounov et al., 2015 ).

VR art therapy and therapeutic artmaking seem to be promising future interventions for wellbeing. Artmaking in immersive VR was found to lessen the participants’ insecurities about their skill in artmaking, allowing them to be more creative and focused on their therapeutic goals ( Kaimal et al., 2020a ). The malleability of VEs and their ability to adapt to the needs of clients as well as the illusion of presence are found to be some of the main contributors in facilitating healing. The symbolic, explorative, and controlled nature of VR art therapy allows personalized experiences that can be observed through different distances and points of view. These qualities allow individuals to create order from the fragmentary aspects of life and make sense of their emotions ( Malchiodi, 2002 ). VR could induce motivation and inspiration in clients, especially in those who are receptive towards new media, such as digital natives, whose life typically operates in both the physical and the digital world. Some digital natives choose to allocate their energy resources more in the digital world than the physical one and this phenomenon seems relevant to sociobiological factors and data ubiquity. Taking into consideration the above findings and the conclusions of the systematic review by Wagener et al. (2021) , it could be argued that the lack of applicability of holistic wellbeing approaches, customization, and self-expression in VR is prominent possibly because substantial steps to elevate the state of the art in the direction of art therapy and therapeutic artmaking have yet to be made.

The reviewed papers often indicate disadvantages of VR over traditional art media while implying that, nowadays, most of the highlighted issues are surmountable enough. Most of the explored issues, such as interdisciplinary concerns and the lack of digital literacy, are likely to move towards resolution the more they become adequately addressed. Other issues, such as the lack of cost-effective solutions for VR ownership and development, as well as tactility absence in VR during artmaking, can be more nuanced. The lack of tactility experienced through digital art therapy initially used to be one of the main sources of skepticism in art therapists regarding the adoption of digital art therapy practices. However, it has been observed that the lack of tactility could be an uncanny feeling for some but also a trivial matter for others, whose modalities combine inside the VR environment to create an illusion of tactility ( Hacmun et al., 2021 ). Currently, electrostimulation-based techniques are employed to tackle both the issue of tactility absence and cybersickness in VR ( Li et al., 2020 ; Vizcay et al., 2021 ).

All the reviewed papers are unanimous regarding the appropriateness of VR in art-based therapeutic practices, even though some researchers from the reviewed papers but also from the broader literature challenge the notion that fully immersive VR favors interventions for which the connection between client and therapist is deliberately distant ( Gatto et al., 2020 ; Hacmun et al., 2021 ). Xiong et al. (2022) argue that Augmented Reality (AR) could be a more suitable technology for art-based rehabilitation interventions than fully immersive VR because of the increased possibilities for social interaction in AR, among other reasons. As Alex et al. (2021) argue, sociability in VR applications, even though it exists, needs to be a more prominent feature. The accessibility increase of psychotherapeutic practices to collaborative VR spaces through telepresence could mitigate some of the interdisciplinary and technical problems which VR psychotherapy sustains, such as the limited accommodation of the triangular psychotherapeutic relationship to the VE. Importantly, the role of the therapist or the researcher, who is cut off from observing the implicit actions of the client/user during an artistic fully immersive VR intervention, is bound to be degraded due to the observer’s constrained ability to derive accurate conclusions. This implies that current VR technology favors the forms of art therapy in which the role of the therapist is peripheral to the psychotherapeutic relationship and this limitation is arguably detrimental to the overall usability of fully immersive VR as a therapeutic tool.

However, the authors by no means suggest that fully immersive VR is deleterious to the role of the therapist. Despite the drawbacks that fully immersive VR has in store regarding the therapist’s role, VR is also found to be especially useful for building trust between client and therapist, which is an important aspect of the psychotherapeutic relationship ( Frewen et al., 2020 ; Shamri Zeevi, 2021 ). The term “collaborative VR” refers to social VR platforms that allow user-generated content and synchronous communication in 3D virtual spaces via telepresence ( Saffo et al., 2021 ). Collaborative VR platforms where both client(s) and therapist(s) can simultaneously occupy the same virtual space through telepresence exist in a nascent stage (i. e., VRChat and the “Metaverse”), which are likely to become more of the norm in the years to come and prominent therapeutic spaces ( Rzeszewski and Evans, 2020 ; Hacmun et al., 2021 ). These platforms can employ eye tracking and real-time facial expression mapping techniques for avatars, which could be a solution to the problem of communicating emotional cues through VR ( Joachimczak et al., 2022 ). Nevertheless, a challenge that needs to be addressed regarding real-time facial expression mapping is that facial expressions of avatars need to mitigate their levels of perceived uncanniness and this challenge mostly concerns photorealistic avatars ( Kumarapeli et al., 2022 ). As fully immersive VR is progressively becoming more geared towards commercial use, the development of collaborative VR is more likely to gain momentum and subsequently elevate the role of the therapist and the possibilities offered regarding art-based therapy treatments.

5 Future directions

Despite the topic of VR in therapy being relatively new and the challenges being many, there is promising evidence regarding the therapeutic use of art-based VR interventions. The variables that constitute an effective digital application for art therapy are already evident ( Marks et al., 2017 ) but the transformation of theoretical knowledge into effective therapeutic practices, especially in the case of new media, needs further experimentation. As suggested by the reviewed papers, future research could pertain to the transfer and optimization of neurocognitive tests in VR with emphasis on drawing and visuospatial reasoning ( Jin et al., 2020 ). VR also poses an opportunity for studying the impact of artmaking on the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) from a theoretical standpoint that derives from pieces of research focusing on artmaking and anxiety disorders ( Sandmire et al., 2012 ; Sandmire et al., 2016 ). It is already known that artmaking practices help in reducing stress and anxiety, but VR technology could elevate our understanding of artmaking even further, thanks to the facilitation of data management and the ecological validity offered by VR interventions ( Richesin et al., 2021 ).

Even though many novel approaches to therapy have been described in this review, the full potential of immersive VR technology in therapeutic treatments seems to remain underutilized ( Geraets et al., 2021 ) and art-based treatments are no exception. One of the most underutilized affordances of VR in art therapy and therapeutic artmaking is that of the embodied expression via virtual avatars. The concepts of embodied cognition, virtual avatars, and embodiment are commonly found in the literature of fully immersive VR ( Kyrlitsias and Michael-Grigoriou, 2022 ), but the role of the avatars in the reviewed papers was given little to no attention. Reviewed studies that deployed fully immersive VR were found to be limited to the obligatory motion capture of the hands, provided by the controllers or other motion-capture techniques, which tend to make the VR user feel like a body-less ghost with visible hands. Arguably, the embodiment of virtual avatars, and its subsequent sensations of body ownership and body agency, should be considered as crucial elements of art-based therapeutic treatments in VR because of the indispensable role of kinesthetic and sensorimotor activity, as well as spatial awareness, during art therapy interventions. As Malchiodi (2020) notes, the most compelling reason for using any expressive arts therapy intervention is probably the sensory nature of the arts themselves, which cultivate cognitive and emotional awareness but also the awareness of somatic sensations that contributes to body-kinesthetic intelligence. Given that the facilitation of the communication between mind and body is one of the tenets of art therapy, when the VR user has no visual affirmation of having and controlling a body, the possibility that the lack of the expected visuo-proprioceptive stimuli downplays the efficacy of art therapy becomes prevalent. On a psychosocial level, embodied expression via avatars in VR could organically integrate into art-based therapeutic practices and enhance therapeutic experiences because of the possible influence of VR embodiment and presence in changing implicit attitudes. Adopting methods such as, the “ Proteus Effect” could prove to be useful in the context of art therapy in numerous creative ways, for example using avatar-based emotional priming interventions (e.g., for attitude change) or aiming for avatar-assisted cultivation of psychomotor skills.

Continuing in the lines of embodied cognition, another area of interest for future research could be that of embodied simulation. The Michelangelo effect is a good example of the utilization of the mirror neuron system in motor-impaired individuals for neurorehabilitation. An inference from the study, in which the term “Michelangelo effect” hails ( Iosa et al., 2021 ), could be that artmaking, even if subconsciously practiced via embodied simulation, activates visual-motor mirror neurons to the degree of facilitating neurorehabilitation. More research is needed to assess the level of significance of the association between VR artmaking (combined with shared body states of virtual humans) and neurorehabilitation.

Finally, psychotherapy interventions should go beyond “building safe spaces” when it comes to externalizations of mental representations in VR. Creative work in VR could often lead to creating a bridge between the physical world and emotions ( Shamri Zeevi, 2021 ). Externalizations help in understanding where the person stands in relation to a problem, and what they might need in order to gain control over it, but it also provides understanding of the nature and the scale of the problem as it is already evident through enhanced perspective change and replay value ( Marks et al., 2017 ). Intrusive mental images of distinct shapes and forms could also become available for constructive interaction through externalization. The case study of Walker et al. (2016) corroborates that bringing tormenting intrusive images to “the light of day” through artmaking allowed a sufferer to deconstruct and ultimately vanquish these reoccurring images. However, the efficacy of externalizations for the treatment of intrusive images on a large population with diverse experiences and levels of severity is still in question, since the exact underlying mechanisms of this treatment are unclear. VR technology, through its ecological validity, controllability of environments, and creative applications, provides an adequate opportunity for experimentation on externalizations of mental representations and intrusive mental imagery, while making it possible to generalize results in a larger population. Rosal (2018) points out the necessity of clinical psychology research to focus on the study of intrusive mental images because they are related to many disorders for which our knowledge on their treatment is still insufficient.

6 Conclusion

The aim of this scoping review was to provide comprehensive information for therapy practitioners, application developers, and researchers, who could make use of the presented information to update current practices, and help elevate the state of the art in psychotherapy and rehabilitation. Knowledge regarding VR artmaking and art therapy in the area of wellbeing is already reported in various papers in a fragmented fashion and the scope of the present review was to congregate all the relevant information in a cohesive manner. The unique properties of VR and their significance to the area of art therapy and therapeutic artmaking were detailed and contrasted with traditional therapeutic practices. Further, this review provided the opportunity to focus on underexplored areas of VR practice in psychotherapy and rehabilitation, identify knowledge gaps in the literature and discuss potential future directions in the field of VR.