- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- How to prepare and...

How to prepare and deliver an effective oral presentation

- Related content

- Peer review

- Lucia Hartigan , registrar 1 ,

- Fionnuala Mone , fellow in maternal fetal medicine 1 ,

- Mary Higgins , consultant obstetrician 2

- 1 National Maternity Hospital, Dublin, Ireland

- 2 National Maternity Hospital, Dublin; Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Medicine and Medical Sciences, University College Dublin

- luciahartigan{at}hotmail.com

The success of an oral presentation lies in the speaker’s ability to transmit information to the audience. Lucia Hartigan and colleagues describe what they have learnt about delivering an effective scientific oral presentation from their own experiences, and their mistakes

The objective of an oral presentation is to portray large amounts of often complex information in a clear, bite sized fashion. Although some of the success lies in the content, the rest lies in the speaker’s skills in transmitting the information to the audience. 1

Preparation

It is important to be as well prepared as possible. Look at the venue in person, and find out the time allowed for your presentation and for questions, and the size of the audience and their backgrounds, which will allow the presentation to be pitched at the appropriate level.

See what the ambience and temperature are like and check that the format of your presentation is compatible with the available computer. This is particularly important when embedding videos. Before you begin, look at the video on stand-by and make sure the lights are dimmed and the speakers are functioning.

For visual aids, Microsoft PowerPoint or Apple Mac Keynote programmes are usual, although Prezi is increasing in popularity. Save the presentation on a USB stick, with email or cloud storage backup to avoid last minute disasters.

When preparing the presentation, start with an opening slide containing the title of the study, your name, and the date. Begin by addressing and thanking the audience and the organisation that has invited you to speak. Typically, the format includes background, study aims, methodology, results, strengths and weaknesses of the study, and conclusions.

If the study takes a lecturing format, consider including “any questions?” on a slide before you conclude, which will allow the audience to remember the take home messages. Ideally, the audience should remember three of the main points from the presentation. 2

Have a maximum of four short points per slide. If you can display something as a diagram, video, or a graph, use this instead of text and talk around it.

Animation is available in both Microsoft PowerPoint and the Apple Mac Keynote programme, and its use in presentations has been demonstrated to assist in the retention and recall of facts. 3 Do not overuse it, though, as it could make you appear unprofessional. If you show a video or diagram don’t just sit back—use a laser pointer to explain what is happening.

Rehearse your presentation in front of at least one person. Request feedback and amend accordingly. If possible, practise in the venue itself so things will not be unfamiliar on the day. If you appear comfortable, the audience will feel comfortable. Ask colleagues and seniors what questions they would ask and prepare responses to these questions.

It is important to dress appropriately, stand up straight, and project your voice towards the back of the room. Practise using a microphone, or any other presentation aids, in advance. If you don’t have your own presenting style, think of the style of inspirational scientific speakers you have seen and imitate it.

Try to present slides at the rate of around one slide a minute. If you talk too much, you will lose your audience’s attention. The slides or videos should be an adjunct to your presentation, so do not hide behind them, and be proud of the work you are presenting. You should avoid reading the wording on the slides, but instead talk around the content on them.

Maintain eye contact with the audience and remember to smile and pause after each comment, giving your nerves time to settle. Speak slowly and concisely, highlighting key points.

Do not assume that the audience is completely familiar with the topic you are passionate about, but don’t patronise them either. Use every presentation as an opportunity to teach, even your seniors. The information you are presenting may be new to them, but it is always important to know your audience’s background. You can then ensure you do not patronise world experts.

To maintain the audience’s attention, vary the tone and inflection of your voice. If appropriate, use humour, though you should run any comments or jokes past others beforehand and make sure they are culturally appropriate. Check every now and again that the audience is following and offer them the opportunity to ask questions.

Finishing up is the most important part, as this is when you send your take home message with the audience. Slow down, even though time is important at this stage. Conclude with the three key points from the study and leave the slide up for a further few seconds. Do not ramble on. Give the audience a chance to digest the presentation. Conclude by acknowledging those who assisted you in the study, and thank the audience and organisation. If you are presenting in North America, it is usual practice to conclude with an image of the team. If you wish to show references, insert a text box on the appropriate slide with the primary author, year, and paper, although this is not always required.

Answering questions can often feel like the most daunting part, but don’t look upon this as negative. Assume that the audience has listened and is interested in your research. Listen carefully, and if you are unsure about what someone is saying, ask for the question to be rephrased. Thank the audience member for asking the question and keep responses brief and concise. If you are unsure of the answer you can say that the questioner has raised an interesting point that you will have to investigate further. Have someone in the audience who will write down the questions for you, and remember that this is effectively free peer review.

Be proud of your achievements and try to do justice to the work that you and the rest of your group have done. You deserve to be up on that stage, so show off what you have achieved.

Competing interests: We have read and understood the BMJ Group policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: None.

- ↵ Rovira A, Auger C, Naidich TP. How to prepare an oral presentation and a conference. Radiologica 2013 ; 55 (suppl 1): 2 -7S. OpenUrl

- ↵ Bourne PE. Ten simple rules for making good oral presentations. PLos Comput Biol 2007 ; 3 : e77 . OpenUrl PubMed

- ↵ Naqvi SH, Mobasher F, Afzal MA, Umair M, Kohli AN, Bukhari MH. Effectiveness of teaching methods in a medical institute: perceptions of medical students to teaching aids. J Pak Med Assoc 2013 ; 63 : 859 -64. OpenUrl

24 Oral Presentations

Many academic courses require students to present information to their peers and teachers in a classroom setting. This is usually in the form of a short talk, often, but not always, accompanied by visual aids such as a power point. Students often become nervous at the idea of speaking in front of a group.

This chapter is divided under five headings to establish a quick reference guide for oral presentations.

A beginner, who may have little or no experience, should read each section in full.

For the intermediate learner, who has some experience with oral presentations, review the sections you feel you need work on.

The Purpose of an Oral Presentation

Generally, oral presentation is public speaking, either individually or as a group, the aim of which is to provide information, entertain, persuade the audience, or educate. In an academic setting, oral presentations are often assessable tasks with a marking criteria. Therefore, students are being evaluated on their capacity to speak and deliver relevant information within a set timeframe. An oral presentation differs from a speech in that it usually has visual aids and may involve audience interaction; ideas are both shown and explained . A speech, on the other hand, is a formal verbal discourse addressing an audience, without visual aids and audience participation.

Types of Oral Presentations

Individual presentation.

- Breathe and remember that everyone gets nervous when speaking in public. You are in control. You’ve got this!

- Know your content. The number one way to have a smooth presentation is to know what you want to say and how you want to say it. Write it down and rehearse it until you feel relaxed and confident and do not have to rely heavily on notes while speaking.

- Eliminate ‘umms’ and ‘ahhs’ from your oral presentation vocabulary. Speak slowly and clearly and pause when you need to. It is not a contest to see who can race through their presentation the fastest or fit the most content within the time limit. The average person speaks at a rate of 125 words per minute. Therefore, if you are required to speak for 10 minutes, you will need to write and practice 1250 words for speaking. Ensure you time yourself and get it right.

- Ensure you meet the requirements of the marking criteria, including non-verbal communication skills. Make good eye contact with the audience; watch your posture; don’t fidget.

- Know the language requirements. Check if you are permitted to use a more casual, conversational tone and first-person pronouns, or do you need to keep a more formal, academic tone?

Group Presentation

- All of the above applies, however you are working as part of a group. So how should you approach group work?

- Firstly, if you are not assigned to a group by your lecturer/tutor, choose people based on their availability and accessibility. If you cannot meet face-to-face you may schedule online meetings.

- Get to know each other. It’s easier to work with friends than strangers.

- Also consider everyone’s strengths and weaknesses. This will involve a discussion that will often lead to task or role allocations within the group, however, everyone should be carrying an equal level of the workload.

- Some group members may be more focused on getting the script written, with a different section for each team member to say. Others may be more experienced with the presentation software and skilled in editing and refining power point slides so they are appropriate for the presentation. Use one visual aid (one set of power point slides) for the whole group. Take turns presenting information and ideas.

- Be patient and tolerant with each other’s learning style and personality. Do not judge people in your group based on their personal appearance, sexual orientation, gender, age, or cultural background.

- Rehearse as a group, more than once. Keep rehearsing until you have seamless transitions between speakers. Ensure you thank the previous speaker and introduce the one following you. If you are rehearsing online, but have to present in-person, try to schedule some face-to-face time that will allow you to physically practice using the technology and classroom space of the campus.

- For further information on working as a group see:

Working as a group – my.UQ – University of Queensland

Writing Your Presentation

Approach the oral presentation task just as you would any other assignment. Review the available topics, do some background reading and research to ensure you can talk about the topic for the appropriate length of time and in an informed manner. Break the question down as demonstrated in Chapter 17 Breaking Down an Assignment. Where it differs from writing an essay is that the information in the written speech must align with the visual aid. Therefore, with each idea, concept or new information you write, think about how this might be visually displayed through minimal text and the occasional use of images. Proceed to write your ideas in full, but consider that not all information will end up on a power point slide. After all, it is you who are doing the presenting , not the power point. Your presentation skills are being evaluated; this may include a small percentage for the actual visual aid. This is also why it is important that EVERYONE has a turn at speaking during the presentation, as each person receives their own individual grade.

Using Visual Aids

A whole chapter could be written about the visual aids alone, therefore I will simply refer to the key points as noted by my.UQ

To keep your audience engaged and help them to remember what you have to say, you may want to use visual aids, such as slides.

When designing slides for your presentation, make sure:

- any text is brief, grammatically correct and easy to read. Use dot points and space between lines, plus large font size (18-20 point).

- Resist the temptation to use dark slides with a light-coloured font; it is hard on the eyes

- if images and graphs are used to support your main points, they should be non-intrusive on the written work

Images and Graphs

- Your audience will respond better to slides that deliver information quickly – images and graphs are a good way to do this. However, they are not always appropriate or necessary.

When choosing images, it’s important to find images that:

- support your presentation and aren’t just decorative

- are high quality, however, using large HD picture files can make the power point file too large overall for submission via Turnitin

- you have permission to use (Creative Commons license, royalty-free, own images, or purchased)

- suggested sites for free-to-use images: Openclipart – Clipping Culture ; Beautiful Free Images & Pictures | Unsplash ; Pxfuel – Royalty free stock photos free download ; When we share, everyone wins – Creative Commons

This is a general guide. The specific requirements for your course may be different. Make sure you read through any assignment requirements carefully and ask your lecturer or tutor if you’re unsure how to meet them.

Using Visual Aids Effectively

Too often, students make an impressive power point though do not understand how to use it effectively to enhance their presentation.

- Rehearse with the power point.

- Keep the slides synchronized with your presentation; change them at the appropriate time.

- Refer to the information on the slides. Point out details; comment on images; note facts such as data.

- Don’t let the power point just be something happening in the background while you speak.

- Write notes in your script to indicate when to change slides or which slide number the information applies to.

- Pace yourself so you are not spending a disproportionate amount of time on slides at the beginning of the presentation and racing through them at the end.

- Practice, practice, practice.

Nonverbal Communication

It is clear by the name that nonverbal communication are the ways that we communicate without speaking. Many people are already aware of this, however here are a few tips that relate specifically to oral presentations.

Being confident and looking confident are two different things. Fake it until you make it.

- Avoid slouching or leaning – standing up straight instantly gives you an air of confidence.

- Move! When you’re glued to one spot as a presenter, you’re not perceived as either confident or dynamic. Use the available space effectively, though do not exaggerate your natural movements so you look ridiculous.

- If you’re someone who “speaks with their hands”, resist the urge to constantly wave them around. They detract from your message. Occasional gestures are fine.

- Be animated, but don’t fidget. Ask someone to watch you rehearse and identify if you have any nervous, repetitive habits you may be unaware of, for example, constantly touching or ‘finger-combing’ your hair, rubbing your face.

- Avoid ‘voice fidgets’ also. If you needs to cough or clear your throat, do so once then take a drink of water.

- Avoid distractions. No phone turned on. Water available but off to one side.

- Keep your distance. Don’t hover over front-row audience members; this can be intimidating.

- Have a cheerful demeaner. You do not need to grin like a Cheshire cat throughout the presentation, yet your facial expression should be relaxed and welcoming.

- Maintain an engaging TONE in your voice. Sometimes it’s not what you’re saying that is putting your audience to sleep, it’s your monotonous tone. Vary your tone and pace.

- Don’t read your presentation – PRESENT it! Internalize your script so you can speak with confidence and only occasionally refer to your notes if needed.

- Lastly, make good eye contact with your audience members so they know you are talking with them, not at them. You’re having a conversation. Watch the link below for some great speaking tips, including eye contact.

Below is a video of some great tips about public speaking from Amy Wolff at TEDx Portland [1]

- Wolff. A. [The Oregonion]. (2016, April 9). 5 public speaking tips from TEDxPortland speaker coach [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JNOXZumCXNM&ab_channel=TheOregonian ↵

communication of thought by word

Academic Writing Skills Copyright © 2021 by Patricia Williamson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

A Guide to Oral Presentation and Statement of Intention

Oral presentations can be incredibly daunting for students, and most of us are not the biggest fans of public speaking. To help you alleviate your stress in preparing for this SAC, we have created a comprehensive guide on this particular topic which includes some ideas to help you develop your writing, research and presentation skills! An annotated sample response is also attached for your reference.

- Choosing a Topic for your SAC

Researching Your Issue

Creating a contention, writing your speech, presentation tips.

- Sample Speech

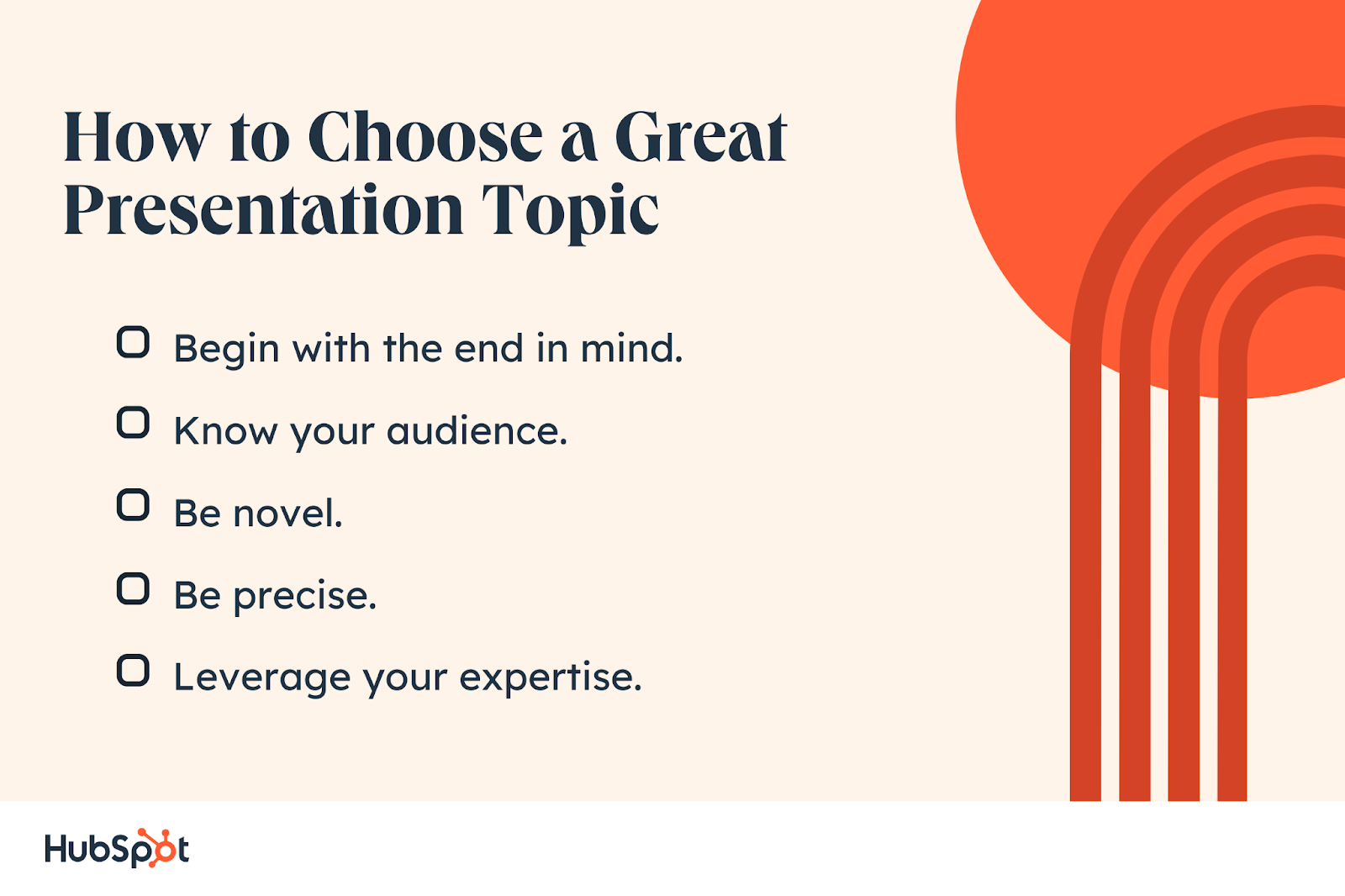

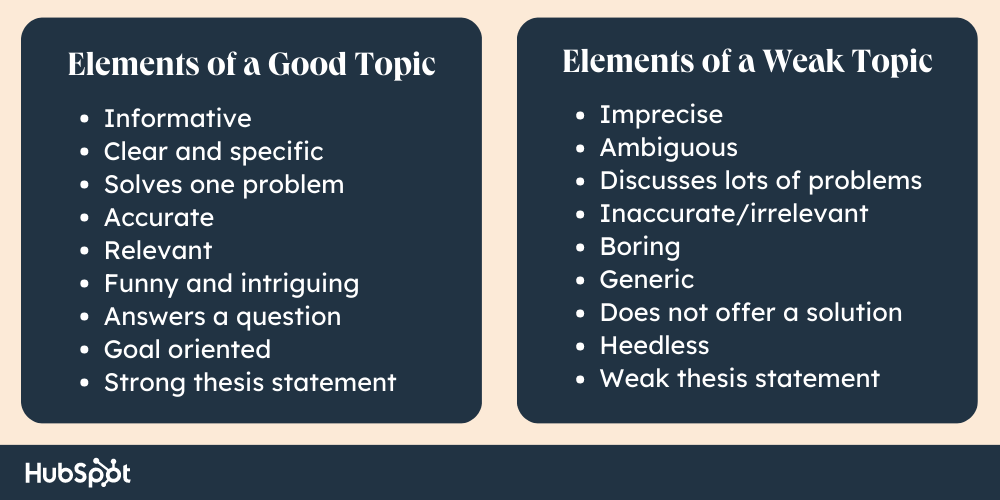

Choosing a Topic for your Oral Presentation SAC

When selecting a topic for your presentation ensure, that there are clearly two sides to the issue. For example, the issue of whether or not Australia should implement a sugar tax has arguments both for and against. This means that you will have lots of opposing opinions to rebut!

Remember that the issue you choose must have appeared in the Australian media since September the 1st the previous year. When choosing an issue, try to base it around a specific event, proposal or something concrete. For example, the general topic of climate change is too broad, whereas writing about whether or not the school climate strikes (specific event) should be allowed to proceed, sufficiently narrows down the topic.

Further, make sure that the issue you choose will be interesting and understandable to your audience of teachers and VCE students. You should avoid topics which require you to use extensive jargon. Your audience is most likely to be captivated by a relatable topic that they care about and understand.

Make sure to phrase your issue as a precise question that you can answer in your contention. For example “Should Australia increase surveillance in an attempt to counteract terrorism?”.

If you are struggling to choose an issue the ABC News Archive is a good starting place. If in doubt, choose an issue which you are interested in! You are more likely to be motivated to spend time researching and writing on a topic that you care about.

Once you have chosen a topic make sure to conduct research before writing your speech! A good place to begin is by searching for coverage in popular news sources (The Age, The Herald Sun, The ABC, The Australian). Next, you may also want to use some lesser known but still reputable websites (The Conversation, A Current Affair, Q&A, 9 News, Insight, etc.). Make sure that you read articles arguing both for and against your contention.

As you read, note down any key arguments, quotes, pieces of evidence or persuasive techniques which you think may inspire or support your own speech. Once you have done this for 5–10 articles you should be ready to write! When writing, aim to go further than just synthesising the arguments that you have seen others present. Assessors are looking for your ability to create unique and convincing arguments, which are supported by research and evidence.

Your contention must be precise and concise. You should avoid contentions that are too broad or are already generally accepted in society, such as “climate change exists” or “hate speech is wrong”. An example of a specific and detailed contention is “Australia must allow punters to test their pills at music festivals and the police to operate in a similar way to the Sydney injecting centre where using drugs is not a crime.”

The Introduction:

Start with an opening sentence which grabs the attention of your audience. This could take the form of an anecdote, rhetorical question, quote, shocking statistic, etc.

- Establish the importance and urgency of your issue.

- Relate to your audience by using inclusive language.

- Clearly state your contention and briefly summarise your arguments.

If you are taking on a persona use some time to introduce yourself. Taking on a persona is recommended so that you can establish your credibility and stake in the issue. When choosing a persona keep in mind that if you choose to speak as a professional person (politician, lawyer, doctor, etc.) you should consider the type of jargon and formal language that they may use.

- Be sure to vary your sentence length. Short sentences are usually more impactful than extended ones.

- Define any key terms.

The Body Paragraphs:

Begin and end each body paragraph by clearly signposting your argument.

Your paragraphs should be made up of evidence and explanation that supports your argument.

Aim for a balance between appealing to the audience’s sense of logic (with evidence, appeals to common sense, expert opinion, etc.) and appealing to their emotions (with emotive language, anecdotes, connotations and rhetorical questions).

Make use of a variety of persuasive language techniques! Take inspiration from the techniques used in the articles you found during the research stage.

Utilise words with connotations, or implied meanings, in order to influence the audience’s perception of the issue. For example, if you were arguing for graffiti to be considered as art you may refer to it as “street art”, whereas if you were arguing for it to be considered a criminal offence you may describe it as “vandalism”.

Acknowledge the potential arguments of the opposition and then rebut them. You can include this rebuttal throughout your essay or as a final paragraph dedicated to criticising your opposition.

The Conclusion:

- Restate your contention and briefly summarise your arguments.

- Remind the audience of why the issue is important and how it relates to them directly.

Your conclusion must end in a memorable way to ensure that your speech stands out to the assessor and remains on their mind after its conclusion. You may choose to do this with a rhetorical question, quote, statistic, anecdote, etc.

Ensure that you make eye contact with various members of your audience and look around the room. Raise your cue cards so that you don’t need to look down too far to see them.

Whilst presenting your speech try to stand still and avoid swaying or pacing. Use your arms to make natural gestures; however, do not overdo this.

Read your speech aloud to your family or friends to practice your delivery. Another option is reading your speech in front of a camera or mirror. Aim to practise the speech until you have it memorised.

Make sure to vary your tone when presenting. Pause after making an important statement and emphasise elements that you want the audience to pay attention to with volume and tone. Variation will make your speech more engaging for the audience.

Make sure to time your speech to ensure that it is within the time restriction. Also ensure that you are speaking at a slightly slower pace than usual so that the audience can follow your points easily.

If speaking with props or a Powerpoint presentation, avoid overcomplicating your materials. You don’t want to distract the audience from your speech by overwhelming them with busy Powerpoint slides, or bore them by simply reading straight from your presentation.

The Written Explanation

The written explanation gives you an opportunity to explain the choices that you have made when writing your speech. Often these statements have a strict word limit usually around 400–500 words (depending on your school), which means that you need to be as concise as possible. The written explanation is worth 25% of your mark for this outcome, so make sure that you take it seriously. When writing your statement of intention you can follow the structure outlined below.

Provide a brief description of your issue and any specific events which sparked media coverage.

Contention:

Clearly state your stance on the issue. You may also like to include why you have chosen this stance.

Outline where and when you will be presenting your speech and why you have made this choice. If you are taking on a persona explain who you have chosen to speak as and why.

Select a target audience which is suitable for your presentation. Describe why you have chosen to present to this specific group of people.

Consider the overall language style you have used (formal, informal, personal, etc.) and the persuasive language techniques you have incorporated (repetition, comparison, connotations, etc.). How do you intend for these techniques to influence your audience?

Outline what you want to achieve by presenting your speech. What is the message you would like the audience to receive? What is the desired outcome of your speech?

To download this, click here .

Related posts.

An Ultimate Guide to Analysing Plays

Your 2024 VCE English cheat sheets: Text summaries, key themes and approaches to genre

A Pocket Guide to Argument Analysis

Text Response: Identifying and Correcting Common Essay Errors

Creative Responses and Written Commentary (SOIs) Explained

.webp)

Introducing online resources

$45 per month • Free for current students

We are excited to launch an online library of best-in-class resources for VCE training. We are excited to launch an online library of best-in-class resources for VCE training.

This page has been archived and is no longer updated

Oral Presentation Structure

Finally, presentations normally include interaction in the form of questions and answers. This is a great opportunity to provide whatever additional information the audience desires. For fear of omitting something important, most speakers try to say too much in their presentations. A better approach is to be selective in the presentation itself and to allow enough time for questions and answers and, of course, to prepare well by anticipating the questions the audience might have.

As a consequence, and even more strongly than papers, presentations can usefully break the chronology typically used for reporting research. Instead of presenting everything that was done in the order in which it was done, a presentation should focus on getting a main message across in theorem-proof fashion — that is, by stating this message early and then presenting evidence to support it. Identifying this main message early in the preparation process is the key to being selective in your presentation. For example, when reporting on materials and methods, include only those details you think will help convince the audience of your main message — usually little, and sometimes nothing at all.

The opening

- The context as such is best replaced by an attention getter , which is a way to both get everyone's attention fast and link the topic with what the audience already knows (this link provides a more audience-specific form of context).

- The object of the document is here best called the preview because it outlines the body of the presentation. Still, the aim of this element is unchanged — namely, preparing the audience for the structure of the body.

- The opening of a presentation can best state the presentation's main message , just before the preview. The main message is the one sentence you want your audience to remember, if they remember only one. It is your main conclusion, perhaps stated in slightly less technical detail than at the end of your presentation.

In other words, include the following five items in your opening: attention getter , need , task , main message , and preview .

Even if you think of your presentation's body as a tree, you will still deliver the body as a sequence in time — unavoidably, one of your main points will come first, one will come second, and so on. Organize your main points and subpoints into a logical sequence, and reveal this sequence and its logic to your audience with transitions between points and between subpoints. As a rule, place your strongest arguments first and last, and place any weaker arguments between these stronger ones.

The closing

After supporting your main message with evidence in the body, wrap up your oral presentation in three steps: a review , a conclusion , and a close . First, review the main points in your body to help the audience remember them and to prepare the audience for your conclusion. Next, conclude by restating your main message (in more detail now that the audience has heard the body) and complementing it with any other interpretations of your findings. Finally, close the presentation by indicating elegantly and unambiguously to your audience that these are your last words.

Starting and ending forcefully

Revealing your presentation's structure.

To be able to give their full attention to content, audience members need structure — in other words, they need a map of some sort (a table of contents, an object of the document, a preview), and they need to know at any time where they are on that map. A written document includes many visual clues to its structure: section headings, blank lines or indentations indicating paragraphs, and so on. In contrast, an oral presentation has few visual clues. Therefore, even when it is well structured, attendees may easily get lost because they do not see this structure. As a speaker, make sure you reveal your presentation's structure to the audience, with a preview , transitions , and a review .

The preview provides the audience with a map. As in a paper, it usefully comes at the end of the opening (not too early, that is) and outlines the body, not the entire presentation. In other words, it needs to include neither the introduction (which has already been delivered) nor the conclusion (which is obvious). In a presentation with slides, it can usefully show the structure of the body on screen. A slide alone is not enough, however: You must also verbally explain the logic of the body. In addition, the preview should be limited to the main points of the presentation; subpoints can be previewed, if needed, at the beginning of each main point.

Transitions are crucial elements for revealing a presentation's structure, yet they are often underestimated. As a speaker, you obviously know when you are moving from one main point of a presentation to another — but for attendees, these shifts are never obvious. Often, attendees are so involved with a presentation's content that they have no mental attention left to guess at its structure. Tell them where you are in the course of a presentation, while linking the points. One way to do so is to wrap up one point then announce the next by creating a need for it: "So, this is the microstructure we observe consistently in the absence of annealing. But how does it change if we anneal the sample at 450°C for an hour or more? That's my next point. Here is . . . "

Similarly, a review of the body plays an important double role. First, while a good body helps attendees understand the evidence, a review helps them remember it. Second, by recapitulating all the evidence, the review effectively prepares attendees for the conclusion. Accordingly, make time for a review: Resist the temptation to try to say too much, so that you are forced to rush — and to sacrifice the review — at the end.

Ideally, your preview, transitions, and review are well integrated into the presentation. As a counterexample, a preview that says, "First, I am going to talk about . . . , then I will say a few words about . . . and finally . . . " is self-centered and mechanical: It does not tell a story. Instead, include your audience (perhaps with a collective we ) and show the logic of your structure in view of your main message.

This page appears in the following eBook

Topic rooms within Scientific Communication

Within this Subject (22)

- Communicating as a Scientist (3)

- Papers (4)

- Correspondence (5)

- Presentations (4)

- Conferences (3)

- Classrooms (3)

Other Topic Rooms

- Gene Inheritance and Transmission

- Gene Expression and Regulation

- Nucleic Acid Structure and Function

- Chromosomes and Cytogenetics

- Evolutionary Genetics

- Population and Quantitative Genetics

- Genes and Disease

- Genetics and Society

- Cell Origins and Metabolism

- Proteins and Gene Expression

- Subcellular Compartments

- Cell Communication

- Cell Cycle and Cell Division

© 2014 Nature Education

- Press Room |

- Terms of Use |

- Privacy Notice |

Visual Browse

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

In the social and behavioral sciences, an oral presentation assignment involves an individual student or group of students verbally addressing an audience on a specific research-based topic, often utilizing slides to help audience members understand and retain what they both see and hear. The purpose is to inform, report, and explain the significance of research findings, and your critical analysis of those findings, within a specific period of time, often in the form of a reasoned and persuasive argument. Oral presentations are assigned to assess a student’s ability to organize and communicate relevant information effectively to a particular audience. Giving an oral presentation is considered an important learning skill because the ability to speak persuasively in front of an audience is transferable to most professional workplace settings.

Oral Presentations. Learning Co-Op. University of Wollongong, Australia; Oral Presentations. Undergraduate Research Office, Michigan State University; Oral Presentations. Presentations Research Guide, East Carolina University Libraries; Tsang, Art. “Enhancing Learners’ Awareness of Oral Presentation (Delivery) Skills in the Context of Self-regulated Learning.” Active Learning in Higher Education 21 (2020): 39-50.

Preparing for Your Oral Presentation

In some classes, writing the research paper is only part of what is required in reporting the results your work. Your professor may also require you to give an oral presentation about your study. Here are some things to think about before you are scheduled to give a presentation.

1. What should I say?

If your professor hasn't explicitly stated what the content of your presentation should focus on, think about what you want to achieve and what you consider to be the most important things that members of the audience should know about your research. Think about the following: Do I want to inform my audience, inspire them to think about my research, or convince them of a particular point of view? These questions will help frame how to approach your presentation topic.

2. Oral communication is different from written communication

Your audience has just one chance to hear your talk; they can't "re-read" your words if they get confused. Focus on being clear, particularly if the audience can't ask questions during the talk. There are two well-known ways to communicate your points effectively, often applied in combination. The first is the K.I.S.S. method [Keep It Simple Stupid]. Focus your presentation on getting two to three key points across. The second approach is to repeat key insights: tell them what you're going to tell them [forecast], tell them [explain], and then tell them what you just told them [summarize].

3. Think about your audience

Yes, you want to demonstrate to your professor that you have conducted a good study. But professors often ask students to give an oral presentation to practice the art of communicating and to learn to speak clearly and audibly about yourself and your research. Questions to think about include: What background knowledge do they have about my topic? Does the audience have any particular interests? How am I going to involve them in my presentation?

4. Create effective notes

If you don't have notes to refer to as you speak, you run the risk of forgetting something important. Also, having no notes increases the chance you'll lose your train of thought and begin relying on reading from the presentation slides. Think about the best ways to create notes that can be easily referred to as you speak. This is important! Nothing is more distracting to an audience than the speaker fumbling around with notes as they try to speak. It gives the impression of being disorganized and unprepared.

NOTE: A good strategy is to have a page of notes for each slide so that the act of referring to a new page helps remind you to move to the next slide. This also creates a natural pause that allows your audience to contemplate what you just presented.

Strategies for creating effective notes for yourself include the following:

- Choose a large, readable font [at least 18 point in Ariel ]; avoid using fancy text fonts or cursive text.

- Use bold text, underlining, or different-colored text to highlight elements of your speech that you want to emphasize. Don't over do it, though. Only highlight the most important elements of your presentation.

- Leave adequate space on your notes to jot down additional thoughts or observations before and during your presentation. This is also helpful when writing down your thoughts in response to a question or to remember a multi-part question [remember to have a pen with you when you give your presentation].

- Place a cue in the text of your notes to indicate when to move to the next slide, to click on a link, or to take some other action, such as, linking to a video. If appropriate, include a cue in your notes if there is a point during your presentation when you want the audience to refer to a handout.

- Spell out challenging words phonetically and practice saying them ahead of time. This is particularly important for accurately pronouncing people’s names, technical or scientific terminology, words in a foreign language, or any unfamiliar words.

Creating and Using Overheads. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Kelly, Christine. Mastering the Art of Presenting. Inside Higher Education Career Advice; Giving an Oral Presentation. Academic Skills Centre. University of Canberra; Lucas, Stephen. The Art of Public Speaking . 12th edition. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill Higher Education, 2015; Peery, Angela B. Creating Effective Presentations: Staff Development with Impact . Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Education, 2011; Peoples, Deborah Carter. Guidelines for Oral Presentations. Ohio Wesleyan University Libraries; Perret, Nellie. Oral Presentations. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Speeches. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Storz, Carl et al. Oral Presentation Skills. Institut national de télécommunications, EVRY FRANCE.

Organizing the Content

In the process of organizing the content of your presentation, begin by thinking about what you want to achieve and how are you going to involve your audience in the presentation.

- Brainstorm your topic and write a rough outline. Don’t get carried away—remember you have a limited amount of time for your presentation.

- Organize your material and draft what you want to say [see below].

- Summarize your draft into key points to write on your presentation slides and/or note cards and/or handout.

- Prepare your visual aids.

- Rehearse your presentation and practice getting the presentation completed within the time limit given by your professor. Ask a friend to listen and time you.

GENERAL OUTLINE

I. Introduction [may be written last]

- Capture your listeners’ attention . Begin with a question, an amusing story, a provocative statement, a personal story, or anything that will engage your audience and make them think. For example, "As a first-gen student, my hardest adjustment to college was the amount of papers I had to write...."

- State your purpose . For example, "I’m going to talk about..."; "This morning I want to explain…."

- Present an outline of your talk . For example, “I will concentrate on the following points: First of all…Then…This will lead to…And finally…"

II. The Body

- Present your main points one by one in a logical order .

- Pause at the end of each point . Give people time to take notes, or time to think about what you are saying.

- Make it clear when you move to another point . For example, “The next point is that...”; “Of course, we must not forget that...”; “However, it's important to realize that....”

- Use clear examples to illustrate your points and/or key findings .

- If appropriate, consider using visual aids to make your presentation more interesting [e.g., a map, chart, picture, link to a video, etc.].

III. The Conclusion

- Leave your audience with a clear summary of everything that you have covered.

- Summarize the main points again . For example, use phrases like: "So, in conclusion..."; "To recap the main issues...," "In summary, it is important to realize...."

- Restate the purpose of your talk, and say that you have achieved your aim : "My intention was ..., and it should now be clear that...."

- Don't let the talk just fizzle out . Make it obvious that you have reached the end of the presentation.

- Thank the audience, and invite questions : "Thank you. Are there any questions?"

NOTE: When asking your audience if anyone has any questions, give people time to contemplate what you have said and to formulate a question. It may seem like an awkward pause to wait ten seconds or so for someone to raise their hand, but it's frustrating to have a question come to mind but be cutoff because the presenter rushed to end the talk.

ANOTHER NOTE: If your last slide includes any contact information or other important information, leave it up long enough to ensure audience members have time to write the information down. Nothing is more frustrating to an audience member than wanting to jot something down, but the presenter closes the slides immediately after finishing.

Creating and Using Overheads. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Giving an Oral Presentation. Academic Skills Centre. University of Canberra; Lucas, Stephen. The Art of Public Speaking . 12th ed. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill Higher Education, 2015; Peery, Angela B. Creating Effective Presentations: Staff Development with Impact . Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Education, 2011; Peoples, Deborah Carter. Guidelines for Oral Presentations. Ohio Wesleyan University Libraries; Perret, Nellie. Oral Presentations. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Speeches. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Storz, Carl et al. Oral Presentation Skills. Institut national de télécommunications, EVRY FRANCE.

Delivering Your Presentation

When delivering your presentation, keep in mind the following points to help you remain focused and ensure that everything goes as planned.

Pay Attention to Language!

- Keep it simple . The aim is to communicate, not to show off your vocabulary. Using complex words or phrases increases the chance of stumbling over a word and losing your train of thought.

- Emphasize the key points . Make sure people realize which are the key points of your study. Repeat them using different phrasing to help the audience remember them.

- Check the pronunciation of difficult, unusual, or foreign words beforehand . Keep it simple, but if you have to use unfamiliar words, write them out phonetically in your notes and practice saying them. This is particularly important when pronouncing proper names. Give the definition of words that are unusual or are being used in a particular context [e.g., "By using the term affective response, I am referring to..."].

Use Your Voice to Communicate Clearly

- Speak loud enough for everyone in the room to hear you . Projecting your voice may feel uncomfortably loud at first, but if people can't hear you, they won't try to listen. However, moderate your voice if you are talking in front of a microphone.

- Speak slowly and clearly . Don’t rush! Speaking fast makes it harder for people to understand you and signals being nervous.

- Avoid the use of "fillers." Linguists refer to utterances such as um, ah, you know, and like as fillers. They occur most often during transitions from one idea to another and, if expressed too much, are distracting to an audience. The better you know your presentation, the better you can control these verbal tics.

- Vary your voice quality . If you always use the same volume and pitch [for example, all loud, or all soft, or in a monotone] during your presentation, your audience will stop listening. Use a higher pitch and volume in your voice when you begin a new point or when emphasizing the transition to a new point.

- Speakers with accents need to slow down [so do most others]. Non-native speakers often speak English faster than we slow-mouthed native speakers, usually because most non-English languages flow more quickly than English. Slowing down helps the audience to comprehend what you are saying.

- Slow down for key points . These are also moments in your presentation to consider using body language, such as hand gestures or leaving the podium to point to a slide, to help emphasize key points.

- Use pauses . Don't be afraid of short periods of silence. They give you a chance to gather your thoughts, and your audience an opportunity to think about what you've just said.

Also Use Your Body Language to Communicate!

- Stand straight and comfortably . Do not slouch or shuffle about. If you appear bored or uninterested in what your talking about, the audience will emulate this as well. Wear something comfortable. This is not the time to wear an itchy wool sweater or new high heel shoes for the first time.

- Hold your head up . Look around and make eye contact with people in the audience [or at least pretend to]. Do not just look at your professor or your notes the whole time! Looking up at your your audience brings them into the conversation. If you don't include the audience, they won't listen to you.

- When you are talking to your friends, you naturally use your hands, your facial expression, and your body to add to your communication . Do it in your presentation as well. It will make things far more interesting for the audience.

- Don't turn your back on the audience and don't fidget! Neither moving around nor standing still is wrong. Practice either to make yourself comfortable. Even when pointing to a slide, don't turn your back; stand at the side and turn your head towards the audience as you speak.

- Keep your hands out of your pocket . This is a natural habit when speaking. One hand in your pocket gives the impression of being relaxed, but both hands in pockets looks too casual and should be avoided.

Interact with the Audience

- Be aware of how your audience is reacting to your presentation . Are they interested or bored? If they look confused, stop and ask them [e.g., "Is anything I've covered so far unclear?"]. Stop and explain a point again if needed.

- Check after highlighting key points to ask if the audience is still with you . "Does that make sense?"; "Is that clear?" Don't do this often during the presentation but, if the audience looks disengaged, interrupting your talk to ask a quick question can re-focus their attention even if no one answers.

- Do not apologize for anything . If you believe something will be hard to read or understand, don't use it. If you apologize for feeling awkward and nervous, you'll only succeed in drawing attention to the fact you are feeling awkward and nervous and your audience will begin looking for this, rather than focusing on what you are saying.

- Be open to questions . If someone asks a question in the middle of your talk, answer it. If it disrupts your train of thought momentarily, that's ok because your audience will understand. Questions show that the audience is listening with interest and, therefore, should not be regarded as an attack on you, but as a collaborative search for deeper understanding. However, don't engage in an extended conversation with an audience member or the rest of the audience will begin to feel left out. If an audience member persists, kindly tell them that the issue can be addressed after you've completed the rest of your presentation and note to them that their issue may be addressed later in your presentation [it may not be, but at least saying so allows you to move on].

- Be ready to get the discussion going after your presentation . Professors often want a brief discussion to take place after a presentation. Just in case nobody has anything to say or no one asks any questions, be prepared to ask your audience some provocative questions or bring up key issues for discussion.

Amirian, Seyed Mohammad Reza and Elaheh Tavakoli. “Academic Oral Presentation Self-Efficacy: A Cross-Sectional Interdisciplinary Comparative Study.” Higher Education Research and Development 35 (December 2016): 1095-1110; Balistreri, William F. “Giving an Effective Presentation.” Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 35 (July 2002): 1-4; Creating and Using Overheads. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Enfield, N. J. How We Talk: The Inner Workings of Conversation . New York: Basic Books, 2017; Giving an Oral Presentation. Academic Skills Centre. University of Canberra; Lucas, Stephen. The Art of Public Speaking . 12th ed. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill Higher Education, 2015; Peery, Angela B. Creating Effective Presentations: Staff Development with Impact . Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Education, 2011; Peoples, Deborah Carter. Guidelines for Oral Presentations. Ohio Wesleyan University Libraries; Perret, Nellie. Oral Presentations. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Speeches. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Storz, Carl et al. Oral Presentation Skills. Institut national de télécommunications, EVRY FRANCE.

Speaking Tip

Your First Words are Your Most Important Words!

Your introduction should begin with something that grabs the attention of your audience, such as, an interesting statistic, a brief narrative or story, or a bold assertion, and then clearly tell the audience in a well-crafted sentence what you plan to accomplish in your presentation. Your introductory statement should be constructed so as to invite the audience to pay close attention to your message and to give the audience a clear sense of the direction in which you are about to take them.

Lucas, Stephen. The Art of Public Speaking . 12th edition. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill Higher Education, 2015.

Another Speaking Tip

Talk to Your Audience, Don't Read to Them!

A presentation is not the same as reading a prepared speech or essay. If you read your presentation as if it were an essay, your audience will probably understand very little about what you say and will lose their concentration quickly. Use notes, cue cards, or presentation slides as prompts that highlight key points, and speak to your audience . Include everyone by looking at them and maintaining regular eye-contact [but don't stare or glare at people]. Limit reading text to quotes or to specific points you want to emphasize.

- << Previous: Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Next: Group Presentations >>

- Last Updated: Mar 6, 2024 1:00 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

Personalised content for

You're viewing this site as a domestic an international student

You're an international student if you are:

- intending to study on a student visa

- not a citizen of Australia or New Zealand

- not an Australian permanent resident

- not a holder of an Australian humanitarian visa.

You're a domestic student if you are:

- a citizen of Australia or New Zealand

- an Australian permanent resident

- a holder of an Australian humanitarian visa.

- Alumni & Giving

- Current students

Search Charles Darwin University

Study Skills

Oral presentations

One of the most common types of assessment at university is presentations. Presentations at university prepare you for life after graduation when your professional communication skills will be invaluable. These materials will help you prepare, design and deliver an informative and audience-friendly presentation.

This page will help you to meet your lecturers' expectations by:

- self-evaluating your current strengths and weaknesses

- planning and organising your presentation

- handling questions

- engaging your audience

- using clear spoken English

- creating effective visuals, slides and posters

- managing group presentations

- managing nervousness

- recording your presentations.

Download this summary sheet for your own reference.

Introduction to oral presentations

This section gives a general overview of presentations.

Before you continue, reflect on your previous public speaking experiences and the feedback you have received. How would you rate your ability in the following skills? Rate your ability from ‘good’ to ‘needs development’.

Reflect on your answers. Congratulations if you feel confident about your skills. You may find it helpful to review the materials on this page to confirm your knowledge and possibly learn more. Don't worry if you don't feel confident. Work through these materials to build your skills.

Spoken tasks are very common at university. Besides oral presentations, how many other types of speaking tasks do you think you may do?

Compare your ideas with these:

The materials on this page focus on presentations, but the tips and strategies are useful for a range of speaking tasks.

A successful presentation is designed to meet the needs of the audience. Think about this. While attending your presentation, the audience needs to:

listen to your voice; i.e., your pronunciation, language choices and style of delivery

understand the information conveyed by your voice

read the text and the visuals on your slides

understand the information conveyed by the text and visuals

watch your face and gestures

understand the messages conveyed by your face and gestures.

The audience must do all these things simultaneously. This is a heavy cognitive load, so your job is to make it as easy as possible for them.

Watch this video for a general introduction to presentations.

Now, check your understanding.

A process for preparing your presentation

This section will take you through the stages of preparing your presentations.

1. Read the task instructions carefully to understand requirements.

When will you deliver the presentation?

Is it individual or group?

Is it online or face-to-face?

Is it recorded or live?

How long is it?

Is a question-and-answer session included?

How will you be assessed?

2. Analyse the task to identify the topic and scope.

Revise how to analyse a task in the Study Skills page Preparing for the essay .

Highlight key words in the task and ensure you use them in the presentation.

3. Consider the needs of your audience by answering these questions:

What does the audience already know about the topic?

What do they need to know?

What is most likely to interest them?

Consider the audience in each of the following situations and decide which presentation element is likely to be the LEAST useful or interesting for them.

4. Do your research.

Visit the Subject Guides on the library page for research tips tailored to your discipline.

Check the Library workshop calendar for workshops revising research skills.

5. Organise your content.

Sequence your content into logical order

Create a presentation plan

Read this example presentation plan. Would this be a useful method for you?

Notice how this student divides their content into topics and sub-topics, puts it into a logical sequence, and decides on the number of slides each topic is likely to need (columns 1 and 2). They then plan potential content for the slides and estimate the amount of time they will spend on each topic (columns 3 and 4).

Remember: a presentation plan will help you to get organised but it is a working document that may change as you learn more about your topic.

6. Create your slides and presentation notes.

A. See Effective visuals below for advice on designing slides.

B. Decide on the most useful type of notes for you. Ideas include:

7. Practise your delivery.

This material contains a lot of advice on ways you can practise. Work through the rest of the page to learn more strategies.

Organisation and transitions

This section will provide an overview of the stages of a presentation and transitions between sections.

In Introduction to oral presentations , you learned that presentations usually have three stages: introduction, body and conclusion.

The amount of time you should spend on the introduction, body, and conclusion of your presentation can vary depending on the length of your presentation, the complexity of your topic, and your personal presentation style. However, as a general guideline, you could aim to allocate your time in the following way:

Remember that these percentages are guidelines, not rules. Your timing may vary so it is important to create a presentation plan and rehearse to ensure you use your time well to effectively communicate your message.

Audiences form their first impression of a speaker within 90 seconds (Wallwork, 2016), so it is important that you introduce yourself with confidence. However, at the start of your presentation, you may be feeling unsettled. If you are nervous about public speaking, plan a simple, well-structured introduction that follows the steps below. By the time you have delivered this information, you may begin to overcome your nerves.

Your introduction should include some or all of the following. You could:

greet the audience and introduce yourself

introduce the topic and aim

give your scope, or specific points on which you will focus

give an outline of your presentation

announce when the audience can ask questions.

use a hook to engage the audience

Read these two presentation introductions to:

identify the stages of an introduction – click on the hotspots to check your ideas

consider how the presentations are similar and different.

These two presentations are about the same topic, but they are different in their approach. Presentation one is more traditional, while presentation two has a more conversational tone and uses more hooks to engage the audience. Both presentations are strong, clear and succinct. In planning your presentation, you should create your own approach that:

meets the needs, interests and expectations of your audience

you feel most confident with.

Read these sentences and place them to create a cohesive introduction.

If you are studying in your second or third language, you may occasionally stumble over collocations (words that usually go together). This exercise is to help you to review common collocations used in introductions.

Just as your essays are divided into paragraphs that present ideas in a logical order, so should your presentation be divided into logical sections.

You need to signal very carefully to your audience when you are linking ideas and when you are transitioning from one section to the next. To manage a transition, you could try one or more of the following ideas.

- Give a brief recap of the main message of the section you just completed (in long presentations).

- Pause for a couple of seconds at the end of each section to give your audience a chance to process the information you have given them.

- Use a divider slide that announces the next part of your talk.

- Use signpost language: phrases that signal transitions and links between ideas.

Signpost language serves an important purpose. Used badly, these phrases can sound stilted and formulaic; however, used well, they help your audience follow your logic, and they help you manage your delivery.

Conclusions are an essential part of your presentation because they are a last chance to convey your most important message and to create a lasting impression on your audience.

Your conclusion should include some or all of the following. You could:

signal that your presentation is concluding

include a summary or overview of your talk

reiterate the takeaway message, or what you MOST want your audience to remember

use a final hook to make a lasting impression on your audience

introduce question time.

Read these two presentation conclusions to:

identify the stages of the conclusions – click on the hotspots to check your ideas

consider how the two presentations are similar and different.

These two conclusions are about the same topic, but they are different in their approach. Conclusion one is more traditional, while conclusion two is more conversational and actively tries to engage the audience. In planning your own presentation, you should create your own approach that:

Questions at presentations and lectures

This section will provide an overview of how you can effectively ask and answer questions.

You may not have given much thought to how you ask questions during presentations or lectures. However, it is important that you can do this well.

Keep these tips in mind:

- If you have a question during a lecture or a conference presentation, don’t be shy to ask. Remember: not only do questions help you to learn, but they can also help you get noticed as an engaged student.

- If the presentation is long, note your questions as you think of them. The question may be answered later in the presentation, but if it isn’t, your notes will help you remember them during question time.

- At the end of long presentations, you should contextualise your question to make it easier to answer. This is explained next.

If a presentation is long, you may need to ask a question about information that was delivered 30 or so minutes previously. Therefore, you may need to identify which part of the presentation you are referring to.

Divide your question into three parts:

If you are studying in your second or third language, you may occasionally stumble over collocations (words that usually go together). This exercise is to help you to review:

the three stages of a question

common collocations used in questions.

The first thing you must remember is that questions at your presentations are a very positive sign. They tell you that your audience has listened, and they are interested enough to want to know more. Nevertheless, question time can make many students feel nervous. However, if you prepare well, you can feel more confident that you can handle this stage of your presentation.

Despite preparing thoroughly, you may sometimes be asked challenging questions that you either don’t quite understand or you are not sure how to answer. Try these strategies.

1. Clarify questions that you don’t understand by asking the questioner:

to stand or speak up if you can’t hear them in a live presentation

to rephrase if you think you are misunderstanding them

questions to clarify what they want to know.

2. Gain a couple of seconds of thinking time by:

commenting on the question

repeating or paraphrasing the question.

3. Refer the question on to:

an appropriate peer in a group presentation - if the question is outside your area

the audience - if the question seems to be more open-ended or hypothetical.

Engaging the audience

This section will review strategies to engage and maintain your audience’s attention.

Engaging your audience can begin before you start your presentation. In fact, it begins when you write your title. A title has two goals:

- To convey the main message of the presentation

- To attract the widest possible audience.

If you are doing a presentation for one of your units, writing the title might seem relatively simple. Your lecturer may even suggest a title. However, if you are participating in an event, you need to write your title more carefully. At many events, the audience chooses which presentations they will attend or which poster presenters they will stop and listen to. For this reason, you need to create an effective but interesting title that will engage the audience at that event.

If you are doing a presentation based on a written assignment or paper, you may rewrite the title for the presentation. This is the title of a paper published by Read et al (2007).

Satellite Tracking Reveals Long Distance Coastal Travel and Homing by Translocated Estuarine Crocodiles, Crocodylus porosus

Read these presentation title suggestions. Which do you prefer?

Over to you:

1. Reread the instructions for your presentation task. Consider these questions:

- What guidelines have you been given for the title?

- Who are the audience and what is likely to interest and engage them?

2. Write a declarative, a descriptive, an interrogative and a two-part title.

3. Ask a peer to read each and give feedback on the most engaging and informative.

Effective presenters use a range of techniques to catch and keep the interest of their audience. These are sometimes called hooks.

Compare these two introductions.

Both introductions are competent, but in the second introduction, Kim hooks the audience with a discussion point. This gets the audience’s attention and increases their curiosity about her topic. You can hook and maintain the audience’s attention in many different ways and at any time during your presentation.

Match these hooks and examples below:

Keep in mind that your audience’s attention may drop during a long presentation, so you can help them focus and follow you by:

spending no more than approximately one or two minutes on each slide

giving or repeating important information when attention is high: the beginning, the end, and after a hook

using a hook when you feel the energy in the room drop.

A large proportion of communication is non-verbal, so your voice and body language are an important part of your presentation. They can create a positive or negative impression on your audience.

Think about these guidelines. What advice is useful for you?

Remember the general guidelines above, but also remember that body language can depend on the presenter’s personality and cultural background.

Don’t try to force yourself to behave in ways that make you uncomfortable. Remember that your body language will be more engaging if you:

feel relaxed and well-prepared

allow your own interest in the topic to show.

Your voice is critical in oral presentations because it is the primary tool you use to convey your message to your audience. Think of your voice as your instrument. How you use it affects how your audience perceives your message.

Reflect on the public speakers you enjoy listening to and find easy to understand. They could be well-known speakers, like a political figure, or less well-known, like a lecturer.

Why do you enjoy listening to them?

What do they do that helps you understand them easily?

Listen to these two extracts.

Which do you think is most effective?

Many listeners would find speaker B more engaging and easier to understand because the speaker uses a good pace, pausing, clear stress and appropriate intonation.

Pace is the speed of our speech.

The average speed is about 125-150 words per minute, but this varies depending on age, gender, culture and situation.

Many public speakers slow their pace slightly so their audience can follow their ideas.

Pausing is a brief stop when we speak.

Speakers naturally pause to draw breath.

Good public speakers use brief pauses to give their audience time to absorb their message.

Intonation is how our voice rises and falls when we speak.

A rising voice creates anticipation. It indicates that another point is coming.

A falling voice creates a sense of importance. It also indicates that you’re finishing a point.

Stress is when we say some words more loudly than others.

Stress is put onto the main content words – or words that carry the main message

Stress is put onto certain words for emphasis to draw attention to a point.

Let’s now explore in more detail how these techniques are used in a presentation.

You can find online support to practise your use of voice through a range of apps and software. One example that you can access through your student Microsoft account is Speaker Coach.

Repetition and the rule of three are two more techniques you can use to make your presentation more engaging.

Repetition

We hear repetition frequently in speeches. Read these examples in famous political speeches:

Although you may not be a political figure (yet), you may occasionally use some repetition in your presentations. Repetition is used for:

What would you repeat in these sentences?

Practice these sentences by repeating them aloud.

The rule of three

The rule of three is a technique in which we present information in groups of three.

Think about how the rule of three is used in different situations:

Giving ideas in groups of three is not a strict rule; however, it is a useful strategy because it is:

1. Explore how these techniques are used in an authentic presentation.

2. Download the script of the talk below. Read and make notes while you listen again.

Ted Talk script.docx

3. Download the annotated script and compare your answers.

1. Can you finish this sentence using the power of three?

To deliver an effective presentation, I need...

2. Think about a presentation you need to deliver soon.

Script your introduction, including either repetition or a group of three items.

Mark your stress and intonation.

Ask a peer to listen to you deliver it and give you feedback.

Written vs spoken English

Many presentations at university are based on a written assignment. This section will help you adapt your written text to oral English.

When you are preparing a presentation based on a written paper, you may feel tempted to read sections of your paper aloud – especially if the presentation is recorded or online and your audience can’t actually see you. DON’T do this.

- Compare these two texts. Which one is spoken English?

- Move the slider to reveal an analysis of the language

This analysis illustrates an important point: compared to spoken English, written academic English usually:

uses more formal, academic vocabulary

uses more nouns, especially nominalisations

has fewer but longer sentences

is more dense; that is, it contains more detail in fewer words.

Therefore, reading aloud from your paper sounds unnatural, makes your presentation less engaging and makes your information harder for your audience to follow.

Top tip: when you are preparing an oral presentation based on a written text, you should create your presentation from a plan , not from the text. To do this, you could:

- read through your written text, and for each paragraph, write key words into a separate document

- use the key words to make a presentation plan

- practise delivering your talk from the key words; if you forget some elements, add extra notes

- transfer your notes to one of the following:

note cards for each stage of your talk a printout of your slides a list of key ideas and facts in bullet points a tree-diagram or flowchart of the structure of the talk

5. practise delivering your talk using your notes, not the original assignment.

Another point to consider when you are preparing a presentation based on an assignment is how you will handle the data and statistics. Many of these are conveyed through visuals, such as tables and graphs; however, you still need to explain your figures. To do this, you must consider how you will say them.

Listen to these extracts and consider how clear the figures are.

Remember:

- Use percentages when you can because they are usually easier for audiences to remember.

- Use smaller figures when you can because they are usually easier for listeners to comprehend.

- Reduce the number of figures you recite.

- Support figures with words and phrases like rise or fall, majority or minority, or trend

- Avoid difficult combinations of sounds and pay special attention to numbers that end in -teen or - ty.

Top tips:

When you are preparing an oral presentation based on a written text that includes numbers, try these ideas.

- Ask a peer to listen to your talk and write down the numbers they hear. If any are incorrect, consider how you can make them clearer for the listener.

- Ensure that important figures you need to say are also written on your slides.

In Engaging the audience , you learned about avoiding highly technical words in your titles to attract a wide audience. This also applies in the body of your presentation, especially if your audience is multi-disciplinary (or including people from a range of disciplines besides yours).

Just as you consider audience and purpose in your writing, you must do the same when preparing your oral presentations.

Read the following two sentences. Which would you say to multi-disciplinary listeners?

Stem cell malfunction is caused by DNA damage produced by reactive oxygen species.

DNA damage-induced HSPC malfunction depends on ROS accumulation downstream of IFN-1 signaling and bid mobilisation

Most people would agree that sentence one would be appropriate for an audience with people from outside your discipline.

Top Tip:

If your audience is multi-disciplinary, ensure you provide definitions or examples to explain necessary technical words. Images on your slides are also useful.

Effective visuals – slides and posters

This section will give you tips for creating effective slides or posters.

Design is a broad but interesting field that you might like to explore if you need to produce many visuals in your future studies or your profession. For now, these tips will introduce you to basic principles to help you get started on your first slides and posters.

Examine each slide to determine the design problem. Then click to the next slides for a useful tip.

Over to you:

Examine slides you are drafting for your own presentation. Have you avoided these issues?

A poster presentation at a conference is a session where researchers present their work on a poster. A poster is a visual display of the researcher's work, including text, graphs, images, and tables.

During the presentation session, the researcher stands by their poster and explains their work to conference attendees who walk around the room viewing the posters. This is the major difference between regular conference presentations and poster presentations: conference presentations attract an audience with a well-written abstract ; however, posters attract an audience by being eye-catching, visually pleasing, legible and informative.

The design elements that you must consider are the same as those outlined above for slides. However, you must also consider that the audience needs to be able to read the poster from at least 1.5m away

Compare these two posters. Move the slider left and right so you can compare different elements.

Here are some key poster characteristics. Well-designed posters are: