A Brief History of the English Language: From Old English to Modern Days

Join us on a journey through the centuries as we trace the evolution of English from the Old and Middle periods to modern times.

What Is the English Language, and Where Did It Come From?

The different periods of the english language, the bottom line.

Today, English is one of the most common languages in the world, spoken by around 1.5 billion people globally. It is the official language of many countries, including the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

English is also the lingua franca of international business and academia and is one of the six official languages of the United Nations.

Despite its widespread use, English is not without its challenges. Because it has borrowed words from so many other languages, it can be difficult to know how to spell or pronounce certain words. And, because there are so many different dialects of English, it can be hard to understand someone from a different region.

But, overall, English is a rich and flexible language that has adapted to the needs of a rapidly changing world. It is truly a global, dominant language – and one that shows no signs of slowing down. Join us as we guide you through the history of the English language.

Discover how to learn words 3x faster

Learn English with Langster

The English language is a West Germanic language that originated in England. It is the third most spoken language in the world after Mandarin Chinese and Spanish. English has been influenced by a number of other languages over the centuries, including Old Norse, Latin, French, and Dutch.

The earliest forms of English were spoken by the Anglo-Saxons, who settled in England in the 5th century. The Anglo-Saxons were a mix of Germanic tribes from Scandinavia and Germany. They brought with them their own language, which was called Old English.

The English language has gone through distinct periods throughout its history. Different aspects of the language have changed throughout time, such as grammar, vocabulary, spelling , etc.

The Old English period (5th-11th centuries), Middle English period (11th-15th centuries), and Modern English period (16th century to present) are the three main divisions in the history of the English language.

Let's take a closer look at each one:

Old English Period (500-1100)

The Old English period began in 449 AD with the arrival of three Germanic tribes from the Continent: the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes. They settled in the south and east of Britain, which was then inhabited by the Celts. The Anglo-Saxons had their own language, called Old English, which was spoken from around the 5th century to the 11th century.

Old English was a Germanic language, and as such, it was very different from the Celtic languages spoken by the Britons. It was also a very different language from the English we speak today. It was a highly inflected language, meaning that words could change their form depending on how they were being used in a sentence.

There are four known dialects of the Old English language:

- Northumbrian in northern England and southeastern Scotland,

- Mercian in central England,

- Kentish in southeastern England,

- West Saxon in southern and southwestern England.

Old English grammar also had a complex system, with five main cases (nominative, accusative, genitive, dative, instrumental), three genders (masculine, feminine, and neuter), and two numbers (singular and plural).

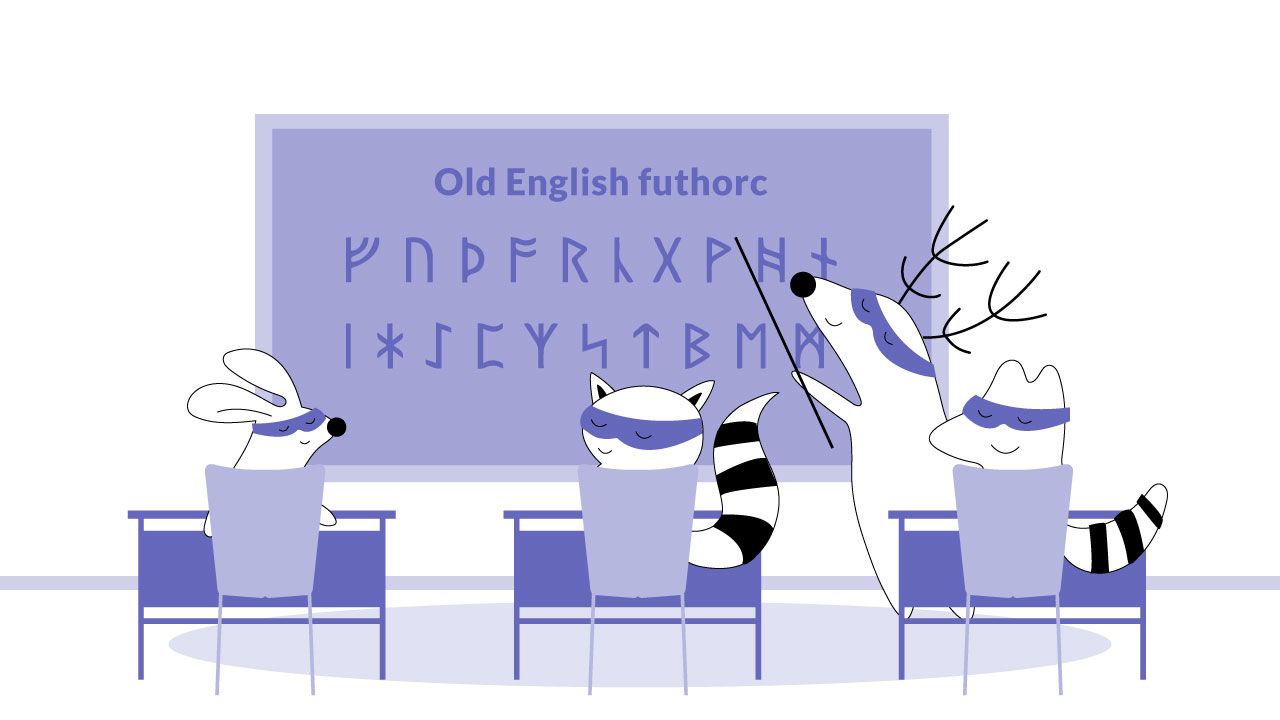

The Anglo-Saxons also had their own alphabet, which was known as the futhorc . The futhorc consisted of 24 letters, most of which were named after rune symbols. However, they also borrowed the Roman alphabet and eventually started using that instead.

The vocabulary was also quite different, with many words being borrowed from other languages such as Latin, French, and Old Norse. The first account of Anglo-Saxon England ever written is from 731 AD – a document known as the Venerable Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People , which remains the single most valuable source from this period.

Another one of the most famous examples of Old English literature is the epic poem Beowulf , which was written sometime between the 8th and 11th centuries. By the end of the Old English period at the close of the 11th century, West Saxon dominated, resulting in most of the surviving documents from this period being written in the West Saxon dialect.

The Old English period was a time of great change for Britain. In 1066, the Normans invaded England and conquered the Anglo-Saxons. The Normans were originally Viking settlers from Scandinavia who had settled in France in the 10th century. They spoke a form of French, which was the language of the ruling class in England after the Norman Conquest.

The Old English period came to an end in 1066 with the Norman Conquest. However, Old English continued to be spoken in some parts of England until the 12th century. After that, it was replaced by Middle English.

Middle English Period (1100-1500)

The second stage of the English language is known as the Middle English period , which was spoken from around the 12th century to the late 15th century. As mentioned above, Middle English emerged after the Norman Conquest of 1066, when the Normans conquered England.

As a result of the Norman Conquest, French became the language of the ruling class, while English was spoken by the lower classes. This led to a number of changes in the English language, including a reduction in the number of inflections and grammatical rules.

Middle English is often divided into two periods: Early Middle English (11th-13th centuries) and Late Middle English (14th-15th centuries).

Early Middle English (1100-1300)

The Early Middle English period began in 1066 with the Norman Conquest and was greatly influenced by French, as the Normans brought with them many French words that began to replace their Old English equivalents. This process is known as Normanisation.

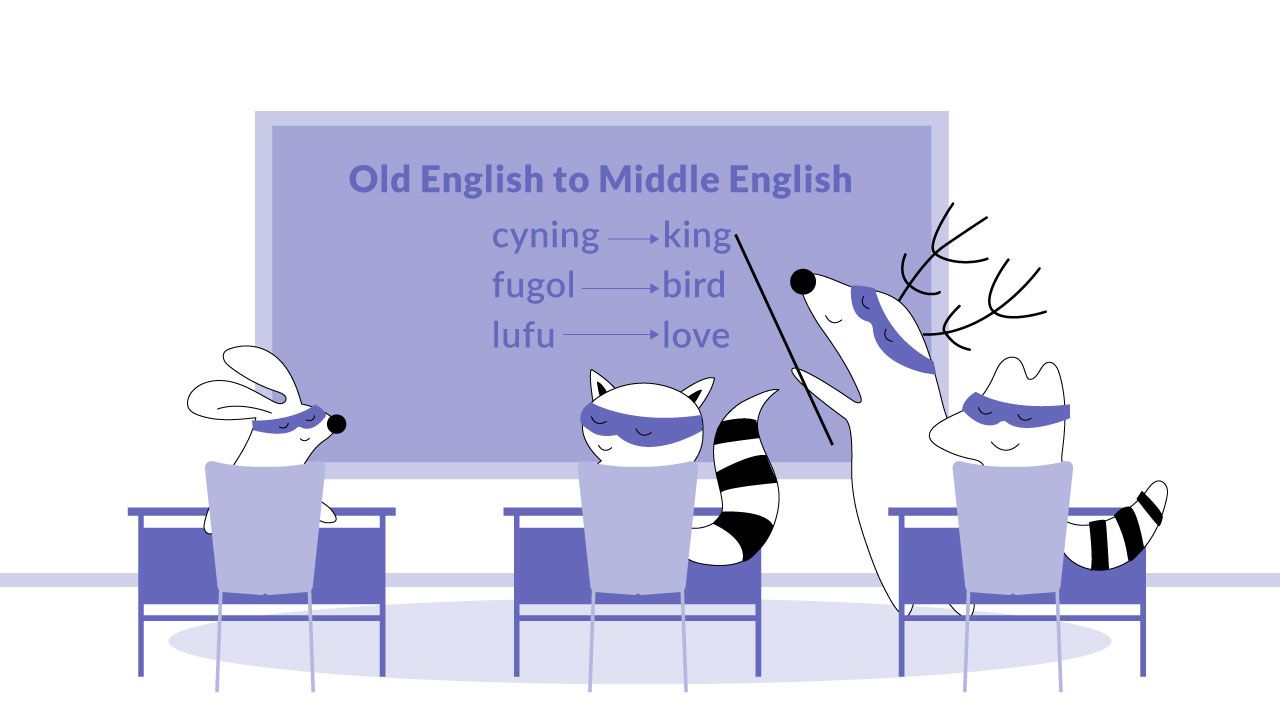

One of the most noticeable changes was in the vocabulary of law and government. Many Old English words related to these concepts were replaced by their French equivalents. For example, the Old English word for a king was cyning or cyng , which was replaced by the Norman word we use today, king .

The Norman Conquest also affected the grammar of Old English. The inflectional system began to break down, and words started to lose their endings. This Scandinavian influence made the English vocabulary simpler and more regular.

Late Middle English (1300-1500)

The Late Middle English period began in the 14th century and lasted until the 15th century. During this time, the English language was further influenced by French.

However, the Hundred Years’ War (1337-1453) between England and France meant that English was used more and more in official documents. This helped to standardize the language and make it more uniform.

One of the most famous examples of Middle English literature is The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer, which was written in the late 14th century. Chaucer was the first major writer in English, and he e helped to standardize the language even further. For this reason, Middle English is also frequently referred to as Chaucerian English.

French influence can also be seen in the vocabulary, with many French loanwords being introduced into English during this time. Middle English was also influenced by the introduction of Christianity, with many religious terms being borrowed from Latin.

Modern English Period (1500-present)

After Old and Middle English comes the third stage of the English language, known as Modern English , which began in the 16th century and continues to the present day.

The Early Modern English period, or Early New English, emerged after the introduction of the printing press in England in 1476, which meant that books could be mass-produced, and more people learned to read and write. As a result, the standardization of English continued.

The Renaissance (14th-17th centuries) saw a rediscovery of classical learning, which had a significant impact on English literature. During this time, the English language also borrowed many Greek and Latin words. The first English dictionary , A Table Alphabeticall of Hard Words , was published in 1604.

The King James Bible , which was first published in 1611, also had a significant impact on the development of Early Modern English. The Bible was translated into English from Latin and Greek, introducing many new words into the language.

The rise of the British Empire (16th-20th centuries) also had a significant impact on the English language. English became the language of commerce, science, and politics, and was spread around the world by British colonists. This led to the development of many different varieties of English, known as dialects.

One of the most famous examples of Early Modern English literature is William Shakespeare's play Romeo and Juliet , which was first performed in 1597. To this day, William Shakespeare is considered the greatest writer in the English language.

The final stage of the English language is known as Modern English , which has been spoken from around the 19th century to the present day. Modern English has its roots in Early Modern English, but it has undergone several changes since then.

The most significant change occurred in the 20th century, with the introduction of mass media and technology. For example, new words have been created to keep up with changing technology, and old words have fallen out of use. However, the core grammar and vocabulary of the language have remained relatively stable.

Today, English is spoken by an estimated 1.5 billion people around the world, making it one of the most widely spoken languages in the world. It is the official language of many countries, including the United Kingdom, the United States, and Australia. English is also the language of international communication and is used in business, education, and tourism.

English is a fascinating language that has evolved over the centuries, and today it is one of the most commonly spoken languages in the world. The English language has its roots in Anglo-Saxon, a West Germanic language spoken by the Anglo-Saxons who settled in Britain in the 5th century.

The earliest form of English was known as Old English, which was spoken until around the 11th century. Middle English emerged after the Norman Conquest of 1066, and it was spoken until the late 15th century. Modern English began to develop in the 16th century, and it has continued to evolve since then.

If you want to expand your English vocabulary with new, relevant words, make sure to download our Langster app , and learn English with stories! Have fun!

Ellis is a seasoned polyglot and one of the creative minds behind Langster Blog, where she shares effective language learning strategies and insights from her own journey mastering the four languages. Ellis strives to empower learners globally to embrace new languages with confidence and curiosity. Off the blog, she immerses herself in exploring diverse cultures through cinema and contemporary fiction, further fueling her passion for language and connection.

Learn with Langster

Teaching English As a Foreign Language: Tips and Resources

Review: BBC Learning English App and Course

What Is Britain: 9 Facts About the United Kingdom Everyone Should Know

More Langster

- Why Stories?

- For Educators

- French A1 Grammar

- French A2 Grammar

- German A1 Grammar

- German A2 Grammar

- Spanish Grammar

- English Grammar

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.1: Development of the English Language

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 134560

Learning Objectives

- Recognize the key influences on the development of the English language.

- Understand the broad timeline of the development of the English language.

The English language and English literature began with the recorded history of Britain.

The early history of England includes five invasions which contributed to the development of the English language and influenced the literature:

- the Roman invasion

- the Anglo-Saxon invasions

- the Christian “invasion”

- the Viking invasions

- the Norman French invasion

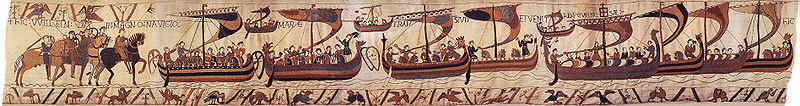

Norman Invasion portrayed in the Bayeux Tapestry.

The Roman Invasion

At the time of the earliest written records, the British islands were inhabited by Celtic people known as the Britons. ( See Map 1 .) Although the Roman Empire made initial contacts with the Celtic people in Britain around 55 B.C., the Roman invasion of Britain began around A.D. 43. The Celtic people resisted but were unable to fend off the invading Roman troops. One of the principal figures fighting the Romans was the Celtic queen Boudicca . Unlike their Roman counterparts, Celtic societies allotted women rights often equal to those of men. When her husband, an ally of the Romans, died, the Romans took over the land of her tribe, the Iceni, flogging Boudicca and raping her daughters. Boudicca led her people in revolt and for some time managed to hold back the mighty Roman legions.

Roman lighthouse at Dover.

Long familiar with Britain as a source of tin, the Romans conquered Britain around A.D. 44 and set up fortresses, light houses on the coast, and a defensive wall across the entire Northern border of England named Hadrian’s Wall for the Roman emperor Hadrian. As they did in many parts of the world, the Romans built villas with beautiful mosaics, a series of roads which were used for centuries, and great Roman baths, such as those at Aquae Sulis, now known as Bath, England. View a video mini-lecture that explains the Roman invasion .

Roman bath overflow at Bath, England.

How did the Roman invasion affect the development of the English language? While there is no direct linguistic connection, the Roman occupation of Britain and their subsequent abandonment of the country set the stage for the most important invasion, the Anglo-Saxon invasion which provided the foundation of the English language.

The Anglo-Saxon Invasions

At the fall of the Roman Empire (ca. 420), the Roman troops were called back to the continent, and Britain was left undefended. This period of time produced the figure that was transformed in legend into King Arthur . The man who formed the basis of the Arthurian legend was probably a descendent of Celtic and Roman people who led his followers in resisting the Anglo-Saxons. This resistance occurred long before the days of knights in armor mounted on horseback, the picture of King Arthur found in most stories.

The Anglo-Saxons were Germanic tribes who began raiding the coastal areas of Britain around 450. ( See Map 2 .) For over 100 years, the Anglo-Saxons continued to raid and gradually to settle in Britain, pushing the Celtic people into the remote parts of Britain—into what are today the countries of Wales, Scotland, and Ireland. ( See Map 3 and Map 4 .) With them, they took their Celtic language which formed the basis of the Gaelic languages of Scotland, Wales, and Ireland. (See Map 5.) Few Celtic words remain in today’s English; those few are primarily place names such as avon for river (as in the English town Stratford-upon-Avon) and words associated with the countries to which the Celts dispersed such as glen (valley), loch (lake), and cairn (pile of stones) from Scotland.

Anglo-Saxon ornament in the British Museum.

The Anglo-Saxon Germanic Language Is the Foundation of the English Language

The culture of the Anglo-Saxons is much in evidence in Old English literature, especially in the concept of the Germanic heroic ideal. The primary attribute of the heroic ideal was excellence—excellence in all that was important to the tribe: hunting, sea-faring, fighting. The leader of each tribal unit, often family units especially in earlier years, gained his position because of his physical strength and capabilities in the activities necessary for survival. Each man of the tribe, called a thane or retainer, an Anglo-Saxon warrior loyal to a specific leader, swore his allegiance, and in return his leader rewarded him with the spoils of their battles and raids. A group of Anglo-Saxon warriors bound by the reciprocal king-retainer relationship was known as a comitatus . An example is the group of Geats led by Beowulf.

These Anglo-Saxon tribes led violent lives governed as they believed by wyrd , the Anglo-Saxon word for fate, the power that controls one’s destiny, and bound by loyalty to their comitatus , including the obligation of exacting revenge for their comrades. A formal system of wergild , a price placed on a man’s life and paid in lieu of blood revenge, provided an honorable way to end a feud or to satisfy the demands of revenge.

By the year 700, various tribes settled in different parts of Britain, each with its own dialect. ( See Map 6 .) The language generally known as Old English came primarily from the dialect of the West Saxons, located in an area known as Wessex.

Video Clip 1

The Anglo-Saxon Invasion: Beowulf and the Sutton Hoo Exhibit

(click to see video)

Although mostly illiterate, the Anglo-Saxons had a rich tradition of oral literature. Gathered in the mead hall with its long tables around a central hearth, the Anglo-Saxons listened to tales of battle glory sung or chanted to the strums of a harp. The scop , the tribal poet/singer, entertained and commemorated significant events by composing and performing tales such as Beowulf . Although many scholars have varying ideas about how these performances might have sounded, little is known of secular music during this time period, and there is of course no evidence to suggest whether the songs were more like chants with strums of the harp perhaps in the caesura or whether they were lively, rambunctious, melodic performances. We might remember that in Beowulf , it’s the sound of laughter, the music of the harp, and the singing of the scop that drives Grendel to attack Heorot.

Reconstruction of Anglo-Saxon harp from remnants in Sutton Hoo.

The Anglo-Saxon invasion established the English language and the earliest English literature. The next important step, the recording of that literature, came with the return of Christianity to Britain.

The Christian “Invasion”

Although certainly not a military invasion like the others in the list, the arrival of Christianity in Britain was as influential on the language and the culture, and therefore on the literature. Christianity was not unknown in Britain when St. Augustine arrived in 597 but had appeared during the time of the Romans. However, Christianity was suppressed along with the Celtic tribes during the Anglo-Saxon invasions. In 597, St. Augustine arrived on a mission to Christianize the pagan Anglo-Saxons, and the literature of the time bears witness to his influence. During the same time period, Celtic Christianity continued to spread from the northern and western reaches. The Anglo-Saxons were mostly illiterate; therefore, their oral stories were not written until the Christian monks recorded them. Many twentieth-century scholars believed that Beowulf , for example, was originally a pagan story and that references to Christianity are interpolations made by the recording monks in their reluctance to perpetuate strictly pagan literature or as a way of converting still-pagan Anglo-Saxons. Most scholars now believe that Beowulf was more likely composed by a Christian author who drew on and perhaps paid homage to his pagan roots.

Video Clip 2

The Christian Invasion: St. Augustine’s Abbey, Canterbury

Burial site of St. Augustine’s successor Laurence in the abbey ruins.

Many words with Latin roots found their way into the English language with the assimilation of Christianity into the culture, many of them words for religious concepts for which the Anglo-Saxons had no terms, such as angel, priest, martyr, bishop.

The establishment of monasteries in Britain also led to the production of beautifully illuminated manuscripts, such as the Lindisfarne Gospels. The British Library’s Virtual Books Online Gallery allows you to virtually turn the pages of the Lindisfarne gospels .

Video Clip 3

The Lindisfarne Gospels

The Viking Invasions

Between 750 and 1050, another group of war-like, pagan tribes raided Britain and gradually established settlements, primarily in the north and east of England. The Vikings were from the area now known as Scandinavia. While they shared cultural similarities with the Anglo-Saxons, they brought their own language, another impact on the developing English language. Words such as sky, skin, wagon originated with the language of the Vikings.

Ruins of Lindisfarne Priory.

Sidebar 1.1.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (translated by E. E. C. Gomme, 1909) describes the Viking raid on the Holy Island of Lindisfarne:

“Here terrible portents came about over the land of Northumbria, and miserably frightened the people: these were immense flashes of lightening, and fiery dragons were seen flying in the air. A great famine immediately followed these signs; and a little after that in the same year on 8 June the raiding of heathen men miserably devastated God’s church in Lindisfarne island by looting and slaughter.”

These fishing huts on the Holy Isle of Lindisfarne are built in the shape of overturned Viking boats, still suggesting the Viking heritage of this area as a result of the Viking raiding parties and the eventual coming of Viking settlers. The English language also retains evidence of the Viking influence. In northeastern England, place names recall their Viking settlers: York from Jorvik and Whitby from the Viking by meaning a farm.

Alfred the Great negotiated a peaceful settlement with the Vikings by partitioning Britain in what was known as the Danelaw , establishing a period of relatively peaceful coexistence in which the language and the culture mingled.

Video Clip 4

The Viking Invasion: Chester, England

Video Clip 5

St. Gregory’s Minster, Kirkdale, England

The Norman Invasion

The year 1066 is possibly the most important date in the history of Britain and in the development of the English language. When William the Conqueror defeated the English King Harold at the Battle of Hastings, he brought to England a new language and a new culture. Old French became the language of the court, of the government, the church, and all the aristocratic entities. Old English, the language of the Anglo-Saxons, existed only among the conquered lower orders of society. However, within three to four hundred years, the English language emerged, greatly enriched by French vocabulary and distinctly different from the Anglo-Saxons’ Old English, Chaucer’s language, now referred to as Middle English.

Pevensy Castle ruins—Pevensy Castle was built by William the Conqueror on ruins of Roman and Anglo-Saxon settlements.

Video Clip 6

The Norman Invasion: William the Conqueror and the Battle of Hastings

The British Library provides an interactive timeline that traces the development of the English language, beginning with Beowulf.

Key Takeaways

The development of the English language was influenced by 5 events:

- the Norman invasion

- The Germanic language of the Anglo-Saxons, known as Old English, is the foundation of the English language.

- Construct a timeline which includes key events in the development of the English language.

- On a map of the British Isles, locate areas of Roman settlements, Celtic settlements after the Roman invasion, Anglo-Saxon settlements, Canterbury (the site of St. Augustine’s church and monastery), Viking settlements, and the Holy Island of Lindisfarne.

- On a contemporary map of England, locate cities whose names contain recognizable Roman influence such as castor or cester and wich or wick ; Anglo-Saxon influence such as stow , ham , ton , or bury ; Viking influence such as by , thorpe , or thwaite ; and Norman influence such as beau , bel , ville , or mont .

- Celtic Peoples of Roman Britain . Britannia History .

- Roman “Saxon Shore” Forts . Britannia History

- Saxon Invasions and Land Holdings . Britannia History

- Saxon Tribes and Celtic Holdings . Britannia History

- Saxon Control . Britannia History

General Background

- English Language and Literature Timeline . British Library.

The Britons

- “ Arthur: King of the Britons .” David Nash Ford. Britannia .

- “ Boudicca . The Celtic Arts and Cultures Website . The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- “ Britons (Celts) . John Weston. Data Wales .

British Museum Online Tours:

- “ Daily Life in Iron Age Britain

- “ People in Iron Age Britain

- “ Religion and Ritual in Iron Age Britain

- “ War and Art in Iron Age Britain

- Hadrian’s Wall . “Hadrian: Empire and Conflict.” The British Museum.

- “ Alfred the Great .” Monarchs. Britannia .

- “ The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle .” The Online Medieval and Classical Library .

- “ The Anglo-Saxon Fyrd c.400–878 A.D. ” Ben Levick. Regia Anglorum .

The Arrival of Christianity

- “ St. Augustine of Canterbury .” Terry H. Jones. Saints.SPQN.com .

- Lindisfarne Gospels . Virtual Books. Online Gallery. The British Library.

- “ The Venerable Bede (672–735) .” Religion Facts .

- “ The Danelaw .” Britannia .

- “ The Anglo-Saxon Invasion: Beowulf and the Sutton Hoo Exhibit .” Dr. Carol Lowe. McLennan Community College.

- “ The Christian Invasion: St. Augustine’s Abbey, Canterbury .” Dr. Carol Lowe. McLennan Community College.

- “ The Lindisfarne Gospels .” Dr. Carol Lowe. McLennan Community College.

- “ The Norman Invasion: William the Conqueror and the Battle of Hastings .” Dr. Carol Lowe. McLennan Community College.

- “ The Roman Invasion: Boudicca and the Celts .” Dr. Carol Lowe. McLennan Community College.

- “ St Gregory’s Minster, Kirkdale .” Dr. Carol Lowe. McLennan Community College.

- “ The Viking Invasion: Chester, England .” Dr. Carol Lowe. McLennan Community College.

Medieval Manuscripts

- Catalogue of Digitized Medieval Manuscripts . Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies. University of California, Los Angeles.

- Digital Scriptorium . Columbia University and University of California, Berkeley.

- Part Time Courses

- General English

- English Electives

- Online Courses

- Tests and Preparation Courses

- Bespoke Group Courses

- University College Pathway Halifax

- Academic Support

- Social Programme

- Accommodation

- Student Welfare

- Virtual Learning Campus

- Pathways Programs

- Download a Brochure

- English Test

- Visa Information

- Virtual Classroom FAQs

- Prices & Payment

- School Policies

- Public Holidays and Term Dates

- Handbooks & Forms

- Inspection Reports

- Covid-19 Information (North America)

- Contact us now

A brief history of the English language

Regardless of the many languages one is fortunate to be fluent in, English takes its place as one of the world’s predominant forms of communication with its influences extending over as much as +2 billion people globally.

Quirks and inconsistencies aside, the history surrounding its monumental rise is both a fascinating and rich one, and while we promise to be brief, you just might pick up a thing or two that may stimulate your interest in studying English with us here at Oxford International English Schools.

Where it all started

Many of you will be forgiven for thinking that studying an English Language course consists of English grammar more than anything else. While English grammar does play a part when taking courses to improve English overall, it is but a small part of the overall curriculum where one becomes immersed in a history that was partly influenced by myths, battles, and legends on one hand, and the everyday workings of its various social class on the other.

According to the Encyclopedia Britannica , the English language itself really took off with the invasion of Britain during the 5th century. Three Germanic tribes, the Jutes , Saxons and Angles were seeking new lands to conquer, and crossed over from the North Sea. It must be noted that the English language we know and study through various English language courses today had yet to be created as the inhabitants of Britain spoke various dialect of the Celtic language.

During the invasion, the native Britons were driven north and west into lands we now refer to as Scotland, Ireland, and Wales. The word England and English originated from the Old English word Engla-land , literally meaning “the land of the Angles” where they spoke Englisc .

Old English (5th to 11th Century)

Albert Baugh, a notable English professor at the University of Pennsylvania notes amongst his published works [1] that around 85% of Old English is no longer in use; however, surviving elements form the basis of the Modern English language today.

Old English can be further subdivided into the following:

- Prehistoric or Primitive [2] (5th to 7th Century) – available literature or documentation referencing this period is not available aside from limited examples of Anglo-Saxon runes ;

- Early Old English (7th to 10th Century) – this period contains some of the earliest documented evidence of the English language, showcasing notable authors and poets like Cynewulf and Aldhelm who were leading figures in the world of Anglo-Saxon literature.

- Late Old English (10th to 11th Century) – can be considered the final phase of the Old English language which was brought about by the Norman invasion of England. This period ended with the consequential evolution of the English language towards Early Middle English .

Early Middle English

It was during this period that the English language, and more specifically, English grammar, started evolving with particular attention to syntax. Syntax is “ the arrangement of words and phrases to create well-formed sentences in a language, ” and we find that while the British government and its wealthy citizens Anglicised the language, Norman and French influences remained the dominant language until the 14th century.

An interesting fact to note is that this period has been attributed with the loss of case endings that ultimately resulted in inflection markers being replaced by more complex features of the language. Case endings are “ a suffix on an inflected noun, pronoun, or adjective that indicates its grammatical function. ”

History of the English language

Charles Laurence Barber [3] comments, “The loss and weakening of unstressed syllables at the ends of words destroyed many of the distinctive inflections of Old English.”

Similarly, John McWhorter [4] points out that while the Norsemen and their English counterparts were able to comprehend one another in a manner of speaking, the Norsemen’s inability to pronounce the endings of various words ultimately resulted in the loss of inflectional endings.

This brings to mind a colleague’s lisp and I take to wondering: if this were a few hundred years ago, and we were in medieval Britain, could we have imagined that a speech defect would bring about the amazing changes modern history is now looking back on? Something to ponder…

Refer to the image below for an idea of the changes to the English language during this time frame.

Late Middle English

It was during the 14th century that a different dialect (known as the East-Midlands ) began to develop around the London area.

Geoffrey Chaucer, a writer we have come to identify as the Father of English Literature [5] and author of the widely renowned Canterbury Tales , was often heralded as the greatest poet of that particular time. It was through his various works that the English language was more or less “approved” alongside those of French and Latin, though he continued to write up some of his characters in the northern dialects.

It was during the mid-1400s that the Chancery English standard was brought about. The story goes that the clerks working for the Chancery in London were fluent in both French and Latin. It was their job to prepare official court documents and prior to the 1430s, both the aforementioned languages were mainly used by royalty, the church, and wealthy Britons. After this date, the clerks started using a dialect that sounded as follows:

- gaf (gave) not yaf (Chaucer’s East Midland dialect)

- such not swich

- theyre (their) not hir [6]

As you can see, the above is starting to sound more like the present-day English language we know. If one thinks about it, these clerks held enormous influence over the manner of influential communication, which ultimately shaped the foundations of Early Modern English.

Early Modern English

The changes in the English language during this period occurred from the 15th to mid-17th Century, and signified not only a change in pronunciation, vocabulary or grammar itself but also the start of the English Renaissance.

The English Renaissance has much quieter foundations than its pan-European cousin, the Italian Renaissance, and sprouted during the end of the 15th century. It was associated with the rebirth of societal and cultural movements, and while slow to gather steam during the initial phases, it celebrated the heights of glory during the Elizabethan Age .

It was William Caxton ’s innovation of an early printing press that allowed Early Modern English to become mainstream, something we as English learners should be grateful for! The Printing Press was key in standardizing the English language through distribution of the English Bible.

Caxton’s publishing of Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur (the Death of Arthur) is regarded as print material’s first bestseller. Malory’s interpretation of various tales surrounding the legendary King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table, in his own words, and the ensuing popularity indirectly ensured that Early Modern English was here to stay.

It was during Henry the VIII’s reign that English commoners were finally able to read the Bible in a language they understood, which to its own degree, helped spread the dialect of the common folk.

The end of the 16th century brought about the first complete translation of the Catholic Bible, and though it didn’t make a markable impact, it played an important role in the continued development of the English language, especially with the English-speaking Catholic population worldwide.

The end of the 16th and start of the 17th century would see the writings of actor and playwright, William Shakespeare, take the world by storm .

Why was Shakespeare’s influence important during those times? Shakespeare started writing during a time when the English language was undergoing serious changes due to contact with other nations through war, colonisation, and the likes. These changes were further cemented through Shakespeare and other emerging playwrights who found their ideas could not be expressed through the English language currently in circulation. Thus, the “adoption” of words or phrases from other languages were modified and added to the English language, creating a richer experience for all concerned.

It was during the early 17th century that we saw the establishment of the first successful English colony in what was called The New World . Jamestown, Virginia, also saw the dawn of American English with English colonizers adopting indigenous words, and adding them to the English language.

The constant influx of new blood due to voluntary and involuntary (i.e. slaves) migration during the 17th, 18th and 19th century meant a variety of English dialects had sprung to life, this included West African, Native American, Spanish and European influences.

Meanwhile, back home, the English Civil War, starting mid-17th century, brought with it political mayhem and social instability. At the same time, England’s puritanical streak had taken off after the execution of Charles I. Censorship was a given, and after the Parliamentarian victory during the War, Puritans promoted an austere lifestyle in reaction to what they viewed as excesses by the previous regime [7] . England would undergo little more than a decade under Puritan leadership before the crowning of Charles II. His rule, effectively the return of the Stuart Monarchy, would bring about the Restoration period which saw the rise of poetry, philosophical writing, and much more.

It was during this age that literary classics, like those of John Milton’s Paradise Lost , were published, and are considered relevant to this age!

Late Modern English

The Industrial Revolution and the Rise of the British Empire during the 18th, 19th and early 20th-century saw the expansion of the English language.

The advances and discoveries in science and technology during the Industrial Revolution saw a need for new words, phrases, and concepts to describe these ideas and inventions. Due to the nature of these works, scientists and scholars created words using Greek and Latin roots e.g. bacteria, histology, nuclear, biology. You may be shocked to read that these words were created but one can learn a multitude of new facts through English language courses as you are doing now!

Colonialism brought with it a double-edged sword. It can be said that the nations under the British Empire’s rule saw the introduction of the English language as a way for them to learn, engage, and hopefully, benefit from “overseas” influence. While scientific and technological discoveries were some of the benefits that could be shared, colonial Britain saw this as a way to not only teach their language but impart their culture and traditions upon societies they deemed as backward , especially those in Africa and Asia.

The idea may have backfired as the English language walked away with a large number of foreign words that have now become part and parcel of the English language e.g. shampoo, candy, cot and many others originated in India!

English in the 21st Century

If one endevours to study various English language courses taught today, we would find almost no immediate similarities between Modern English and Old English. English grammar has become exceedingly refined (even though smartphone messaging have made a mockery of the English language itself) where perfect living examples would be that of the current British Royal Family. This has given many an idea that speaking proper English is a touch snooty and high-handed. Before you scoff, think about what you have just read. The basic history and development of a language that literally spawned from the embers of wars fought between ferocious civilisations. Imagine everything that our descendants went through, their trials and tribulations, their willingness to give up everything in order to achieve freedom of speech and expression.

Everything has lead up to this point where English learners decide to study the language at their fancy, something we take for granted as many of us have access to courses to improve English at the touch of a button!

Perhaps you’re a fan of Shakespeare, maybe you’re more intune with John Milton or J.K. Rowling? Whatever you fancy, these authors, poets and playwrights bring to life more than just words on a page. With them comes a living history that continues to evolve to this day!

[1] Baugh, Albert (1951). A History of the English Language. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 60–83; 110–130 (Scandinavian influence).

[2] Stumpf, John (1970). An Outline of English Literature; Anglo-Saxon and Middle English Literature. London: Forum House Publishing Company. p. 7. We do not know what languages the Jutes, Angles, and Saxons spoke, nor even whether they were sufficiently similar to make them mutually intelligible, but it is reasonable to assume that by the end of the sixth century there must have been a language that could be understood by all and this we call Primitive Old English.

[3] Berber, Charles Laurence (2000). The English Language; A Historical Introduction. Cambridge University Press. p.157.

[4] McWhorter, Our Magnificent Bastard Tongue, 2008, pp. 89–136

[5] Robert DeMaria, Jr., Heesok Chang, Samantha Zacher (eds.), A Companion to British Literature, Volume 2: Early Modern Literature, 1450-1660, John Wiley & Sons, 2013, p. 41.

[6] http://www.encyclopedia.com/humanities/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/chancery-standard

[7] Durston, 1985

British slang words & phrases

The differences in British and American spelling

Why is the United Kingdom flag called the Union Jack?

Privacy overview.

What are the origins of the English Language?

The history of English is conventionally, if perhaps too neatly, divided into three periods usually called Old English (or Anglo-Saxon), Middle English, and Modern English. The earliest period begins with the migration of certain Germanic tribes from the continent to Britain in the fifth century A.D. , though no records of their language survive from before the seventh century, and it continues until the end of the eleventh century or a bit later. By that time Latin, Old Norse (the language of the Viking invaders), and especially the Anglo-Norman French of the dominant class after the Norman Conquest in 1066 had begun to have a substantial impact on the lexicon, and the well-developed inflectional system that typifies the grammar of Old English had begun to break down.

The following brief sample of Old English prose illustrates several of the significant ways in which change has so transformed English that we must look carefully to find points of resemblance between the language of the tenth century and our own. It is taken from Aelfric's "Homily on St. Gregory the Great" and concerns the famous story of how that pope came to send missionaries to convert the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity after seeing Anglo-Saxon boys for sale as slaves in Rome:

Eft he axode, hu ðære ðeode nama wære þe hi of comon. Him wæs geandwyrd, þæt hi Angle genemnode wæron. Þa cwæð he, "Rihtlice hi sind Angle gehatene, for ðan ðe hi engla wlite habbað, and swilcum gedafenað þæt hi on heofonum engla geferan beon."

A few of these words will be recognized as identical in spelling with their modern equivalents— he, of, him, for, and, on —and the resemblance of a few others to familiar words may be guessed— nama to name, comon to come, wære to were, wæs to was —but only those who have made a special study of Old English will be able to read the passage with understanding. The sense of it is as follows:

Again he [St. Gregory] asked what might be the name of the people from which they came. It was answered to him that they were named Angles. Then he said, "Rightly are they called Angles because they have the beauty of angels, and it is fitting that such as they should be angels' companions in heaven."

Some of the words in the original have survived in altered form, including axode (asked), hu (how), rihtlice (rightly), engla (angels), habbað (have), swilcum (such), heofonum (heaven), and beon (be). Others, however, have vanished from our lexicon, mostly without a trace, including several that were quite common words in Old English: eft "again," ðeode "people, nation," cwæð "said, spoke," gehatene "called, named," wlite "appearance, beauty," and geferan "companions." Recognition of some words is naturally hindered by the presence of two special characters, þ, called "thorn," and ð, called "edh," which served in Old English to represent the sounds now spelled with th .

Other points worth noting include the fact that the pronoun system did not yet, in the late tenth century, include the third person plural forms beginning with th-: hi appears where we would use they. Several aspects of word order will also strike the reader as oddly unlike ours. Subject and verb are inverted after an adverb— þa cwæð he "Then said he"—a phenomenon not unknown in Modern English but now restricted to a few adverbs such as never and requiring the presence of an auxiliary verb like do or have. In subordinate clauses the main verb must be last, and so an object or a preposition may precede it in a way no longer natural: þe hi of comon "which they from came," for ðan ðe hi engla wlite habbað "because they angels' beauty have."

Perhaps the most distinctive difference between Old and Modern English reflected in Aelfric's sentences is the elaborate system of inflections, of which we now have only remnants. Nouns, adjectives, and even the definite article are inflected for gender, case, and number: ðære ðeode "(of) the people" is feminine, genitive, and singular, Angle "Angles" is masculine, accusative, and plural, and swilcum "such" is masculine, dative, and plural. The system of inflections for verbs was also more elaborate than ours: for example, habbað "have" ends with the -að suffix characteristic of plural present indicative verbs. In addition, there were two imperative forms, four subjunctive forms (two for the present tense and two for the preterit, or past, tense), and several others which we no longer have. Even where Modern English retains a particular category of inflection, the form has often changed. Old English present participles ended in -ende not -ing, and past participles bore a prefix ge- (as geandwyrd "answered" above).

The period of Middle English extends roughly from the twelfth century through the fifteenth. The influence of French (and Latin, often by way of French) upon the lexicon continued throughout this period, the loss of some inflections and the reduction of others (often to a final unstressed vowel spelled -e ) accelerated, and many changes took place within the phonological and grammatical systems of the language. A typical prose passage, especially one from the later part of the period, will not have such a foreign look to us as Aelfric's prose has; but it will not be mistaken for contemporary writing either. The following brief passage is drawn from a work of the late fourteenth century called Mandeville's Travels. It is fiction in the guise of travel literature, and, though it purports to be from the pen of an English knight, it was originally written in French and later translated into Latin and English. In this extract Mandeville describes the land of Bactria, apparently not an altogether inviting place, as it is inhabited by "full yuele [evil] folk and full cruell."

In þat lond ben trees þat beren wolle, as þogh it were of scheep; whereof men maken clothes, and all þing þat may ben made of wolle. In þat contree ben many ipotaynes, þat dwellen som tyme in the water, and somtyme on the lond: and þei ben half man and half hors, as I haue seyd before; and þei eten men, whan þei may take hem. And þere ben ryueres and watres þat ben fulle byttere, þree sithes more þan is the water of the see. In þat contré ben many griffounes, more plentee þan in ony other contree. Sum men seyn þat þei han the body vpward as an egle, and benethe as a lyoun: and treuly þei seyn soth þat þei ben of þat schapp. But o griffoun hath the body more gret, and is more strong, þanne eight lyouns, of suche lyouns as ben o this half; and more gret and strongere þan an hundred egles, suche as we han amonges vs. For o griffoun þere wil bere fleynge to his nest a gret hors, 3if he may fynde him at the poynt, or two oxen 3oked togidere, as þei gon at the plowgh.

The spelling is often peculiar by modern standards and even inconsistent within these few sentences (contré and contree, o [griffoun] and a [gret hors], þanne and þan, for example). Moreover, in the original text, there is in addition to thorn another old character 3, called "yogh," to make difficulty. It can represent several sounds but here may be thought of as equivalent to y. Even the older spellings (including those where u stands for v or vice versa) are recognizable, however, and there are only a few words like ipotaynes "hippopotamuses" and sithes "times" that have dropped out of the language altogether.

We may notice a few words and phrases that have meanings no longer common such as byttere "salty," o this half "on this side of the world," and at the poynt "to hand," and the effect of the centuries-long dominance of French on the vocabulary is evident in many familiar words which could not have occurred in Aelfric's writing even if his subject had allowed them, words like contree, ryueres, plentee, egle, and lyoun .

In general word order is now very close to that of our time, though we notice constructions like hath the body more gret and three sithes more þan is the water of the see. We also notice that present tense verbs still receive a plural inflection as in beren, dwellen, han, and ben and that while nominative þei has replaced Aelfric's hi in the third person plural, the form for objects is still hem .

The period of Modern English extends from the sixteenth century to our own day. The early part of this period saw the completion of a revolution in the phonology of English that had begun in late Middle English and that effectively redistributed the occurrence of the vowel phonemes to something approximating their present pattern. (Mandeville's English would have sounded even less familiar to us than it looks.)

Other important early developments include the stabilizing effect on spelling of the printing press and the beginning of the direct influence of Latin and, to a lesser extent, Greek on the lexicon. Later, as English came into contact with other cultures around the world and distinctive dialects of English developed in the many areas which Britain had colonized, numerous other languages made small but interesting contributions to our word-stock.

The historical aspect of English really encompasses more than the three stages of development just under consideration. English has what might be called a prehistory as well. As we have seen, our language did not simply spring into existence; it was brought from the Continent by Germanic tribes who had no form of writing and hence left no records. Philologists know that they must have spoken a dialect of a language that can be called West Germanic and that other dialects of this unknown language must have included the ancestors of such languages as German, Dutch, Low German, and Frisian. They know this because of certain systematic similarities which these languages share with each other but do not share with, say, Danish. However, they have had somehow to reconstruct what that language was like in its lexicon, phonology, grammar, and semantics as best they can through sophisticated techniques of comparison developed chiefly during the last century.

Similarly, because ancient and modern languages like Old Norse and Gothic or Icelandic and Norwegian have points in common with Old English and Old High German or Dutch and English that they do not share with French or Russian, it is clear that there was an earlier unrecorded language that can be called simply Germanic and that must be reconstructed in the same way. Still earlier, Germanic was just a dialect (the ancestors of Greek, Latin, and Sanskrit were three other such dialects) of a language conventionally designated Indo-European, and thus English is just one relatively young member of an ancient family of languages whose descendants cover a fair portion of the globe.

Word of the Day

Tendentious.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Brill | Nijhoff

Brill | Wageningen Academic

Brill Germany / Austria

Böhlau

Brill | Fink

Brill | mentis

Brill | Schöningh

Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht

V&R unipress

Open Access

Open Access for Authors

Open Access and Research Funding

Open Access for Librarians

Open Access for Academic Societies

Discover Brill’s Open Access Content

Organization

Stay updated

Corporate Social Responsiblity

Investor Relations

Policies, rights & permissions

Review a Brill Book

Author Portal

How to publish with Brill: Files & Guides

Fonts, Scripts and Unicode

Publication Ethics & COPE Compliance

Data Sharing Policy

Brill MyBook

Ordering from Brill

Author Newsletter

Piracy Reporting Form

Sales Managers and Sales Contacts

Ordering From Brill

Titles No Longer Published by Brill

Catalogs, Flyers and Price Lists

E-Book Collections Title Lists and MARC Records

How to Manage your Online Holdings

LibLynx Access Management

Discovery Services

KBART Files

MARC Records

Online User and Order Help

Rights and Permissions

Latest Key Figures

Latest Financial Press Releases and Reports

Annual General Meeting of Shareholders

Share Information

Specialty Products

Press and Reviews

Share link with colleague or librarian

Stay informed about this journal!

- Get New Issue Alerts

- Get Advance Article alerts

- Get Citation Alerts

The Descent of English

West germanic, any way you slice it.

Emonds & Faarlund judge subgrouping by problematic criteria and do not actually employ their stated criteria, while those criteria in fact show English to be West Germanic.

Emonds and Faarlund ( E & F ) challenge the traditional position of English within Germanic, as have others recently and in different ways, within linguistics (e.g., McWhorter, 2002; Trudgill, 2011) and beyond (e.g., Forster et al., 2004, 2006; Oppenheimer, 2006). We show that:

1 E & F ’s stated criteria for determining descent are idiosyncratic; 2 E & F don’t follow those criteria; 3 by E & F ’s criteria, English is clearly West Germanic (WGmc).

First, E & F write (2014: 57) that “no principles of linguistic descent even remotely depend on differences in sources of vocabulary.” Instead, a language’s descent is (2014: 57–58):

[…] in accord with an often unarticulated linguistic practice of 200 years, […] properly determined by its grammar, including its morphosyntactic system, and patterns of regular sound change. […] structuralists at least understood that syntax must play a central role as well.

E & F give no source for these views, but actual practice and theory align closely with Barbançon et al. (2013: 146; also Longobardi et al., 2013: 122):

In the current state of the art, linguistic characters are of three types: lexical, phonological, and morphological. (Syntactic characters are not generally used because not enough is known about syntactic change to justify confidence that any syntactic character could provide good evidence for linguistic descent.)

E & F (this volume) provide “lexical and above all syntactic arguments” that English is North Germanic (NGmc), though admitting that the lexicon “ended up as more English than Scandinavian” (2014: 53).

Similarly, “Middle English phonology, especially its phonetics, is very much a continuation of Old English phonology” (2014: 157). English shows trajectories parallel to WGmc but not NGmc, e.g., losing front rounded vowels (like Yiddish, many German dialects, but unlike NGmc), and using alveolar rather than dental articulation for /t, d, n/ (Haugen, 1976: 477–478). Norse speakers would have presumably continued this articulatory feature rather than adopting WGmc patterns.

Morphological discussion focuses on loss, not shared innovation, basically case deflection. Only shared innovation can speak clearly to kinship (Ringe and Eska, 2013: 256, others). Still, core English inflection matches WGmc, not NGmc, reflecting different developments from Proto-Germanic. For instance, ME plurals are formed with typically WGmc -(e)n and -(e)s , cf. Dutch, Frisian; NGmc relies heavily on -Vr forms, lost in English (Blake, 1992a: 126–133, 1992b: 105; Booij, 2002: 24; Haugen, 1976: 76).

In short, E & F find lexical evidence unhelpful yet use it, and see phonological evidence as central, but both types of evidence show English as WGmc. Their morphological evidence is not probative and even divergent inheritance shows English to be WGmc, not NGmc.

Their case thus rests entirely on syntax: “Syntactic evidence for the ancestor of English […] all goes one way,” i.e. with NGmc, not WGmc (this volume). They rely on standard German and Dutch, ignoring rich dialectal variation in German, Low German, Dutch, and Yiddish, which shows precisely the NGmc-like characters they find in English. First, contrary to E & F ’s claim (2014: 91), invariant relative particles or complementizers are widespread across WGmc (e.g., Harbert, 2007: 423–435). Second, E & F maintain that English future modals reflect Norse skulu, munu (2014: 79–81), yet many WGmc dialects use the WGmc cognates here, wollen and sollen (Schirmunski, 2010: 645–646). The development of modals was slow and complex across the family (e.g., Diewald, 1999), making this ill-suited as a diagnostic.

Syntax is further claimed to be resistant to borrowing: “Syntactic continuity and stability through history is a clear indication of a genealogical linguistic relationship” (this volume). Two of their central examples, parasitic gaps and preposition stranding, do transfer in bilingualism. Wisconsin German heritage bilinguals produce parasitic gaps (Bousquette et al., 2013, 2016a, 2016b; Sewell and Salmons, 2014). Bousquette (2015) shows preposition stranding in the same communities, exemplified by his title. The adoption of stranding under contact is widely attested in heritage bilingualism, e.g., King (2013) on Acadian French and Pascual y Cabo and Gómez (2015) on heritage Spanish. Stranding is also attested in WGmc, especially Low German, as shown by Fleischer (2002) (see Bech and Walkden, 2016 on Old English stranding.)

In conclusion, E & F ’s stated criteria for determining descent are at odds with longstanding practice and theory, especially for syntax. E & F do not consistently rely on their claimed criteria, particularly using lexical and not using phonetic/phonological evidence. Most importantly, they ignore extensive phonetic, phonological, morphological and syntactic evidence from across WGmc showing English-like patterns that E & F portray as exclusively NGmc. Beyond that, the assumption that syntax is less vulnerable to contact (this volume), while perhaps intuitively appealing, proves incorrect for critical examples. The list of examples given could be greatly expanded.

In short, distinctively Norse-like characteristics of English reflect contact, shared heritage or parallel innovation, but crucially not Norse ancestry.

Barbançon, François, Steven N. Evans, Luay Nakhleh, Don Ringe, and Tandy Warnow. 2013. An experimental study comparing linguistic phylogenetic reconstruction methods. Diachronica 30: 143–170.

Bech, Kristin and George Walkden. 2016. English is (still) a West Germanic language. Journal of Nordic Linguistics 39: 65–100 (doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0332586515000219).

Blake, Norman. 1992a. The Cambridge History of the English Language . Vol. I : Beginnings to 1066 . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Blake, Norman. 1992b. The Cambridge History of the English Language . Vol. II : 1066 to 1476 . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Booij, Geert. 2002. The Morphology of Dutch . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bousquette, Joshua. 2015. “Is das der Hammer, das du den Traktor gebrochen hast mit?” Preposition stranding in Wisconsin Heritage German. Paper presented at the Sixth Workshop on Immigrant Languages in the Americas ( WILA 6), Uppsala, September 2015.

Bousquette, Joshua, Benjamin Frey, Nick Henry, Daniel Nützel, Michael Putnam, Joseph Salmons, and Alyson Sewell. 2013. How deep is your syntax?—Filler-gap dependencies in heritage language grammar. University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics 19(1): 19–30.

Bousquette, Joshua, Benjamin Frey, Daniel Nützel, Michael Putnam, and Joseph Salmons. 2016a. Parasitic gapping in bilingual grammar: Evidence from Wisconsin Heritage German. Heritage Language Journal . 13(1): 1–28. Available at http://hlj.ucla.edu/.

Bousquette, Joshua, Michael Putnam, Joseph Salmons, Benjamin Frey, and Daniel Nützel. 2016b. Multiple grammars, dominance, and optimization. In Géraldine Legendre, Michael T. Putnam, Henriëtte de Swart, and Erin Zaroukian (eds.), Optimality Theoretic Syntax, Semantics, and Pragmatics: From Uni- to Bidirectional Optimization , 158–176. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Diewald, Gabriele. 1999. Die Modalverben im Deutschen: Grammatikalisierung und Polyfunktionalität . Tübingen: Niemeyer.

Emonds, Joseph and Jan Terje Faarlund. 2014. English: The language of the Vikings . Olomouc: Palacký University Press. Online at http://anglistika.upol.cz/vikings2014/.

Fleischer, Jürg. 2002. Preposition stranding in German dialects. In Sjef Barbiers, Leonie Cornips, and Susanne van der Kleij (eds.), Syntactic Microvariation . Amsterdam: Meertens Institute. Downloadable at http://www.meertens.knaw.nl/books/synmic/ (accessed November 1, 2015).

Forster, Peter, Tobias Polzin, and Arne Röhl. 2006. Evolution of English basic vocabulary within the network of Germanic languages. In Peter Forster and Colin Renfrew (eds.), Phylogenetic Methods and the Prehistory of Languages , 131–138. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archeological Research.

Forster, Peter, Valentino Romano, Francesco Calì, Arne Röhl, and Matthew Hurles. 2004. MtDNA markers for Celtic and Germanic language areas in the British Isles. In Martin Jones (ed.), Traces of Ancestry: Studies in Honour of Colin Renfrew , 99–111. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archeological Research.

Harbert, Wayne. 2007. The Germanic Languages . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Haugen, Einar. 1976. The Scandinavian Languages: An Introduction to Their History . Cambridge, MA : Harvard University Press.

King, Ruth. 2013. Acadian French in Time and Space: A Study in Morphosyntax and Comparative Sociolinguistics . Durham, NC : Duke University Press.

Longobardi, Giuseppe, Cristina Guardiano, Giuseppina Silvestri, Alessio Boattini, and Andrea Ceolin. 2013. Toward a syntactic phylogeny of modern Indo-European languages. Journal of Historical Linguistics 3: 122–152.

McWhorter, John H. 2002. What happened to English? Diachronica 19(2): 217–272.

Oppenheimer, Stephen. 2006. The Origins of the British: A Genetic Detective Story: The Surprising Roots of the English, Irish, Scottish and Welsh . New York: Basic Books.

Pascual y Cabo, Diego and Inmaculada Gómez Soler. 2015. Preposition stranding in Spanish as a heritage language. Heritage Language Journal 12: 186–209. Downloadable at http://www.heritagelanguages.org/ (accessed November 1, 2015).

Ringe, Don and Joseph F. Eska. 2013. Historical Linguistics: Toward a Twenty-first Century Reintegration . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schirmunski, Viktor M. 2010. Deutsche Mundartkunde . 2nd ed. by Larissa Naiditsch. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

Sewell, Alyson and Joseph Salmons. 2014. How far-reaching are the effects of contact? Parasitic gapping in Wisconsin German and English. In Robert Nicolai (ed.), Questioning Language Contact: Limits of Contact, Contact at its Limits , 217–251. Leiden: Brill.

Trudgill, Peter. 2011. Sociolinguistic Typology: Social Determinants of Linguistic Complexity . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

We thank the editors for inviting us to contribute to this discussion, and the following for discussions and comments: Joshua Bousquette, Monica Macaulay, Mike Putnam, and George Walkden. All errors are our own.

Content Metrics

Reference Works

Primary source collections

COVID-19 Collection

How to publish with Brill

Open Access Content

Contact & Info

Sales contacts

Publishing contacts

Stay Updated

Newsletters

Social Media Overview

Terms and Conditions

Privacy Statement

Cookie Settings

Accessibility

Legal Notice

Terms and Conditions | Privacy Statement | Cookie Settings | Accessibility | Legal Notice | Copyright © 2016-2024

Copyright © 2016-2024

- [66.249.64.20|81.177.182.174]

- 81.177.182.174

Character limit 500 /500

Globalization of the English Language: One of the Most Widely Used Languages in the World Expository Essay

English language is one of the most widely used languages in the whole world in spite of the fact that there are many languages. As much as all the other languages are important for various reasons, English language is important because it helps in uniting the whole world.

Consequently, most parts in the world today are united because a high percentage of people have learnt to communicate in English. The issues of languages have a long history. For instance, the story of the tower of Babel has many similarities with the current situation that is facing the English language. While the English language is becoming popular and important, other local languages are vanishing as the days go by.

Therefore, the issue of English becoming an international language and preservation of other languages has become the subject of discussion. With that background in mind, this paper focuses on English language, its importance, as well as the advantages and disadvantages of multiple languages compared to having one single language.

There are some applications on the English language and other languages that can be derived from reading the story of the Tower of Babel as recorded in the book of Genesis in the Christian bible. The story of the tower of Babel came up after people who were speaking only one language united and decided to build one high tower to become famous. God was not delighted with them and he confused their languages such that they started speaking in different languages.

Due to the language confusion, they could not continue with their project and according to the Christian bible, many languages that are present in the world today came up due to the same. Therefore, it is clear that speaking one language is very important because it unites people such that they can be able to undertake a similar project. Some problems and conflicts that are in the world today result from the presence of having many languages as it happened during the time of the Tower of Babel.

As highlighted earlier, other languages are important but on a global scale, English is more important. The issue whether English language is a global language or not is contentious despite the fact that the majority of people in the whole world can communicate in it. In addition, most of the works in different areas such as sciences and literature have been written in English since the authors target meeting a large audience.

On the same note, it is important to point out that most of the works that were originally written in other languages are usually translated into English. As a result, one of the authors concluded in future, all the world literature would be referred to as the English language (Divide).

It is quite true that there is widespread use of English language in the world today but as highlighted earlier, it is not clear whether English will end up becoming a global language. Various studies have indicated that the majority in the world are learning and being taught to speak in English. However, it is important to mention that the number of people speaking a particular language is not the determining factor.

The study of illustrates that the economic as well as the military power of the speakers are usually the most important determining factors. More specifically, the study explains that military power helps in establishing the language but the economic power helps to expand it. Therefore, English may end up becoming an international language not only based on the military power of its speakers but also on their economic power (Crystal).

Although there are some advantages of having one language, it is important to preserve other languages since they are important aspects of culture. According to The Endangered Language Fund, there are about thousand languages which are spoken in the whole world and it is projected that about half of languages may disappear in the twenty first century. Therefore, it is important to perverse those languages failure to which they may become extinct.

There are both advantages and disadvantages of having multiple languages in the world. The story of the Tower of Babel clearly illustrates that having multiple languages leads to misunderstanding, which may eventually lead to conflicts. Language is an important aspect in communication and failure to understand other people does not only lead to conflicts but also lack of harmony.

Though people speaking a similar language may conflict, it is worse when people speak different languages. Secondly, having multiple languages is disadvantageous in the view of the fact that it calls for people to learn and to be taught other foreign languages. Additionally, learning other languages needs not only money but also a lot of devotion.

Currently, people who are learning foreign languages are very few indicating that is not as easy. Translation and localization of products also require additional finances. Therefore, the costs involved in preserving multiple languages as well as the conflicts that emerge from the same are some of the most important disadvantages of having multiple languages.

In the view of the fact that language is an important aspect of culture, it is quite advantageous to have multiple languages since they mark cultural diversity. As much as human beings have had many inventions, studies of Divide indicate that of all the human inventions, language is the greatest.

There are several things concerning culture that can only be learnt and preserved by local languages, which are inclusive but not limited, customs, beliefs, norms and cultural values. Therefore, having multiple languages is very important because it helps in preserving the cultural heritage, which has been developed for many centuries. Apart from that, since the same creates cultural diversity, it can lead to meaningful cultural competition, which may be very beneficial.

The essay has indicated that there are both advantages and disadvantages of multiple languages compared to a single language. Currently, most of the languages are vanishing due to the emergence of international languages, which are becoming very popular. English is an important language in the whole world although the issue whether it is an international language or not is contentious. However, based on its speakers, it is clear that the language is quickly turning out to be important on the global scale.

Most of the English speakers are from the western world like the Americans and they are powerful not only politically but also economically. Study of history indicates that the international languages, which existed in the past like Latin and Greek, are marked by political and economic power. Therefore, if the current trend will continue, English will become an international language.

Works Cited

Crystal, David . English as a Global Language. 2003. Web.

Divide, Linguistic Diversity and the Digital. Jenns Allwood. Web.

The Endangered Language Fund . About the Fund. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, November 2). Globalization of the English Language: One of the Most Widely Used Languages in the World. https://ivypanda.com/essays/english/

"Globalization of the English Language: One of the Most Widely Used Languages in the World." IvyPanda , 2 Nov. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/english/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'Globalization of the English Language: One of the Most Widely Used Languages in the World'. 2 November.

IvyPanda . 2023. "Globalization of the English Language: One of the Most Widely Used Languages in the World." November 2, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/english/.

1. IvyPanda . "Globalization of the English Language: One of the Most Widely Used Languages in the World." November 2, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/english/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Globalization of the English Language: One of the Most Widely Used Languages in the World." November 2, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/english/.

- Vernacular Languages vs. Latin: The Fall of the Babel

- The Library of Babel Parallel With the Tower of Babel

- “New World Babel” by Edward Gray

- "Babel" by Alejandro Gonzalez

- "Babel" and "Super Size Me": Documentaries Analysis

- Borges' "The Circular Ruins" and "The Library of Babel"

- Global Ethics: The Babel Drama by Iñárritu

- Movie Babel by Alejandro Gonzalez Innarritu

- Earth's Issues in “The Vanishing of Gaia” by Lovelock

- Film Studies: “Babel” by Alejandro Gonzalez Innarritu

- The Role of Languages

- Getting Tongue-Tied: When the English Language Starts Dominating

- Language Development Analysis

- Conservative and Liberal Languages

- English as a Global Language Essay

- Importance Of English Language Essay

Importance of English Language Essay

500+ words essay on the importance of the english language.

English plays a dominant role in almost all fields in the present globalized world. In the twenty-first century, the entire world has become narrow, accessible, sharable and familiar for all people as English is used as a common language. It has been accepted globally by many countries. This essay highlights the importance of English as a global language. It throws light on how travel and tourism, and entertainment fields benefit by adopting English as their principal language of communication. The essay also highlights the importance of English in education and employment.

Language is the primary source of communication. It is the method through which we share our ideas and thoughts with others. There are thousands of languages in the world, and every country has its national language. In the global world, the importance of English cannot be denied and ignored. English serves the purpose of the common language. It helps maintain international relationships in science, technology, business, education, travel, tourism and so on. It is the language used mainly by scientists, business organizations, the internet, and higher education and tourism.

Historical background of the English Language

English was initially the language of England, but due to the British Empire in many countries, English has become the primary or secondary language in former British colonies such as Canada, the United States, Sri Lanka, India and Australia, etc. Currently, English is the primary language of not only countries actively touched by British imperialism, but also many business and cultural spheres dominated by those countries. 67 countries have English as their official language, and 27 countries have English as their secondary language.

Reasons for Learning the English Language

Learning English is important, and people all over the world decide to study it as a second language. Many countries have included English as a second language in their school syllabus, so children start learning English at a young age. At the university level, students in many countries study almost all their subjects in English in order to make the material more accessible to international students. English remains a major medium of instruction in schools and universities. There are large numbers of books that are written in the English language. Many of the latest scientific discoveries are documented in English.

English is the language of the Internet. Knowing English gives access to over half the content on the Internet. Knowing how to read English will allow access to billions of pages of information that may not be otherwise available. With a good understanding and communication in English, we can travel around the globe. Knowing English increases the chances of getting a good job in a multinational company. Research from all over the world shows that cross-border business communication is most often conducted in English, and many international companies expect employees to be fluent in English. Many of the world’s top films, books and music are produced in English. Therefore, by learning English, we will have access to a great wealth of entertainment and will be able to build a great cultural understanding.

English is one of the most used and dominant languages in the world. It has a bright future, and it helps connect us to the global world. It also helps us in our personal and professional life. Although learning English can be challenging and time-consuming, we see that it is also very valuable to learn and can create many opportunities.

Frequently Asked Questions on English language Essay

Why is the language english popular.

English has 26 alphabets and is easier to learn when compared to other complex languages.

Is English the official language of India?

India has two official languages Hindi and English. Other than that these 22 other regional languages are also recognised and spoken widely.

Why is learning English important?

English is spoken around the world and thus can be used as an effective language for communication.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Request OTP on Voice Call

Post My Comment

- Share Share

Register with BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

Counselling

25,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today