Desmond Tutu

Nobel Peace Prize award-winner Desmond Tutu was a renowned South African Anglican cleric known for his staunch opposition to the policies of apartheid.

(1931-2021)

Who Was Desmond Tutu?

Desmond Tutu established a career in education before turning to theology, ultimately becoming one of the world's most prominent spiritual leaders. In 1978, Tutu was appointed the general secretary of his country's Council of Churches and became a leading spokesperson for the rights of Black South Africans. During the 1980s, he played an almost unrivaled role in drawing national and international attention to the iniquities of apartheid, and in 1984, he won the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts. He later chaired the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and has continued to draw attention to a number of social justice issues over the years.

Early Life and Education

Desmond Mpilo Tutu was born on October 7, 1931, in Klerksdorp, South Africa. His father was an elementary school principal and his mother worked cooking and cleaning at a school for the blind. The South Africa of Tutu's youth was rigidly segregated, with Black Africans denied the right to vote and forced to live in specific areas. Although as a child Tutu understood that he was treated worse than white children based on nothing other than the color of his skin, he resolved to make the best of the situation and still managed a happy childhood.

"We knew, yes, we were deprived," he later recalled in an Academy of Achievement interview. "It wasn't the same thing for white kids, but it was as full a life as you could make it. I mean, we made toys for ourselves with wires, making cars, and you really were exploding with joy!" Tutu recalled one day when he was out walking with his mother when a white man, a priest named Trevor Huddleston, tipped his hat to her — the first time he had ever seen a white man pay this respect to a Black woman. The incident made a profound impression on Tutu, teaching him that he need not accept discrimination and that religion could be a powerful tool for advocating racial equality.

Tutu graduated from high school in 1950, and although he had been accepted into medical school, his family could not afford the expensive tuition. Instead, he accepted a scholarship to study education at Pretoria Bantu Normal College and graduated with his teacher's certificate in 1953. He then continued on to receive a bachelor's degree from the University of South Africa in 1954. Upon graduation, Tutu returned to his high school alma mater to teach English and history. "...I tried to be what my teachers had been to me to these kids," he said, "seeking to instill in them a pride, a pride in themselves. A pride in what they were doing. A pride that said they may define you as so and so. You aren't that. Make sure you prove them wrong by becoming what the potential in you says you can become."

Fighting Apartheid

Tutu became increasingly frustrated with the racism corrupting all aspects of South African life under apartheid. In 1948, the National Party won control of the government and codified the nation's long-present segregation and inequality into the official, rigid policy of apartheid. In 1953, the government passed the Bantu Education Act, a law that lowered the standards of education for Black South Africans to ensure that they only learned what was necessary for a life of servitude. The government spent one-tenth as much money on the education of a Black student as on the education of a white one, and Tutu's classes were highly overcrowded. No longer willing to participate in an educational system explicitly designed to promote inequality, he quit teaching in 1957.

The next year, in 1958, Tutu enrolled at St. Peter's Theological College in Johannesburg. He was ordained as an Anglican deacon in 1960 and as a priest in 1961. In 1962, Tutu left South Africa to pursue further theological studies in London, receiving his master's of theology from King's College in 1966. He then returned from his four years abroad to teach at the Federal Theological Seminary at Alice in the Eastern Cape as well as to serve as the chaplain of the University of Fort Hare. In 1970, Tutu moved to the University of Botswana, Lesotho and Swaziland in Roma to serve as a lecturer in the department of theology. Two years later, he decided to move back to England to accept his appointment as the associate director of the Theological Education Fund of the World Council of Churches in Kent.

Tutu's rise to international prominence began when he became the first Black person to be appointed the Anglican dean of Johannesburg in 1975. It was in this position that he emerged as one of the most prominent and eloquent voices in the South African anti-apartheid movement, especially important considering that many of the movement's prominent leaders were imprisoned or in exile.

In 1976, shortly after he was appointed Bishop of Lesotho, further raising his international profile, Tutu wrote a letter to the South African prime minister warning him that a failure to quickly redress racial inequality could have dire consequences, but his letter was ignored. In 1978, Tutu was selected as the general secretary of the South African Council of Churches, again becoming the first Black citizen appointed to the position, and he continued to use his elevated position in the South African religious hierarchy to advocate for an end to apartheid. "So, I never doubted that ultimately we were going to be free, because ultimately I knew there was no way in which a lie could prevail over the truth, darkness over light, death over life," he said.

Awarded Nobel Peace Prize

In 1984, Tutu received the Nobel Peace Prize "not only as a gesture of support to him and to the South African Council of Churches of which he was a leader, but also to all individuals and groups in South Africa who, with their concern for human dignity, fraternity and democracy, incite the admiration of the world," as stated by the award's committee. Tutu was the first South African to receive the award since Albert Luthuli in 1960. His receipt of the Nobel Peace Prize transformed South Africa's anti-apartheid movement into a truly international force with deep sympathies all across the globe. The award also elevated Tutu to the status of a renowned world leader whose words immediately brought attention.

Tutu and Nelson Mandela

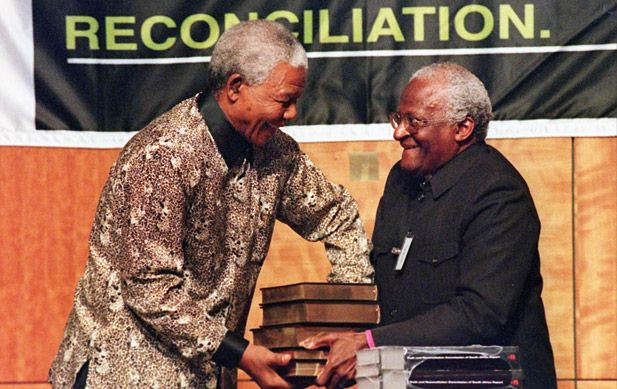

In 1985, Tutu was appointed the Bishop of Johannesburg, and a year later he became the first Black person to hold the highest position in the South African Anglican Church when he was chosen as the Archbishop of Cape Town. In 1987, he was also named the president of the All Africa Conference of Churches, a position he held until 1997. In no small part due to Tutu's eloquent advocacy and brave leadership, in 1993, South African apartheid finally came to an end, and in 1994, South Africans elected Nelson Mandela as their first Black president. The honor of introducing the new president to the nation fell to the archbishop. President Mandela also appointed Tutu to head the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, tasked with investigating and reporting on the atrocities committed by both sides in the struggle over apartheid.

Continued Activism

Although he officially retired from public life in the late 1990s, Tutu continued to advocate for social justice and equality across the globe, specifically taking on issues like treatment for tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS prevention, climate change and the right for the terminally ill to die with dignity. In 2007, he joined The Elders, a group of seasoned world leaders including Kofi Annan , Mary Robinson, Jimmy Carter and others, who meet to discuss ways to promote human rights and world peace.

Desmond Tutu Books

Tutu also penned several books over the years, including No Future Without Forgiveness (1999), the children's title God's Dream (2008) and The Book of Joy: Lasting Happiness in a Changing World (2016), with the latter co-authored by the Dalai Lama .

Tutu stood among the world's foremost human rights activists. Like Nelson Mandela, Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. , his teachings reached beyond the specific causes for which he advocated to speak for all oppressed peoples' struggles for equality and freedom. Perhaps what made Tutu so inspirational and universal a figure was his unshakable optimism in the face of overwhelming odds and his limitless faith in the ability of human beings to do good. "Despite all of the ghastliness in the world, human beings are made for goodness," he once said. "The ones that are held in high regard are not militarily powerful, nor even economically prosperous. They have a commitment to try and make the world a better place."

Personal Life

Tutu married Nomalizo Leah on July 2, 1955. They had four children and remained married until his death on December 26, 2021.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Desmond Tutu

- Birth Year: 1931

- Birth date: October 7, 1931

- Birth City: Klerksdorp

- Birth Country: South Africa

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Nobel Peace Prize award-winner Desmond Tutu was a renowned South African Anglican cleric known for his staunch opposition to the policies of apartheid.

- Civil Rights

- Christianity

- Journalism and Nonfiction

- Education and Academia

- Astrological Sign: Libra

- St. Peter's Theological College

- King's College

- Nacionalities

- South African

- Interesting Facts

- Desmond Tutu first sought out to be a doctor but was unable to afford the tuition.

- Tutu was the first Black person to be appointed the Anglican dean of Johannesburg in 1975.

- Tutu co-authored a book with the Dalai Lama.

- Death Year: 2021

- Death date: December 26, 2021

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Desmond Tutu Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/political-figures/desmond-tutu

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: December 26, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

- ...when you discover that apartheid sought to mislead people into believing that what gave value to human beings was a biological irrelevance, really, skin color or ethnicity, and you saw how the scriptures say it is because we are created in the image of God, that each one of us is a God-carrier. No matter what our physical circumstances may be, no matter how awful, no matter how deprived you could be, it doesn't take away from you this intrinsic worth.

- All of those who have ever strutted the world stage as if they are invincible roosters—Hitler, Stalin, Amin and those apartheid guys...they bite the dust.

- The universe can take quite a while to deliver. God is patient with us to become the God's children he wants us to be but you really can see him weeping.

Watch Next .css-smpm16:after{background-color:#323232;color:#fff;margin-left:1.8rem;margin-top:1.25rem;width:1.5rem;height:0.063rem;content:'';display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;}

Civil Rights Activists

Martin Luther King Jr. Didn’t Criticize Malcolm X

5 Crowning Achievements of Maya Angelou

30 Civil Rights Leaders of the Past and Present

Benjamin Banneker

Marcus Garvey

Madam C.J. Walker

Maya Angelou

Martin Luther King Jr.

17 Inspiring Martin Luther King Quotes

Bayard Rustin

- Member Interviews

- Science & Exploration

- Public Service

- Achiever Universe

- Summit Overview

- About The Academy

- Academy Patrons

- Delegate Alumni

- Directors & Our Team

- Golden Plate Awards Council

- Golden Plate Awardees

- Preparation

- Perseverance

- The American Dream

- Recommended Books

- Find My Role Model

All achievers

Archbishop desmond tutu, nobel prize for peace.

Listen to this achiever on What It Takes

What It Takes is an audio podcast produced by the American Academy of Achievement featuring intimate, revealing conversations with influential leaders in the diverse fields of endeavor: public service, science and exploration, sports, technology, business, arts and humanities, and justice.

Download our free multi-touch iBook Social Justice: Leadership Lessons — for your Mac or iOS device on Apple Books

The Social Justice iBook opens up the compelling, inspiring and selfless world of social justice, giving readers a better understanding of how empowering others, promoting equality and exposing injustice can change the very fabric of our society.

I never doubted that we were going to be free because, ultimately, I knew there was no way in which a lie could prevail over the truth, darkness over light, death over life.

Desmond Tutu was born in Klerksdorp, in the South African state of Transvaal. The family moved to Johannesburg when he was 12, and he attended Johannesburg Bantu High School. Although he had planned to become a physician, his parents could not afford to send him to medical school. Tutu’s father was a teacher, he himself trained as a teacher at Pretoria Bantu Normal College, and graduated from the University of South Africa in 1954.

The government of South Africa did not extend the rights of citizenship to black South Africans. The National Party had risen to power on the promise of instituting a system of apartheid — complete separation of the races. All South Africans were legally assigned to an official racial group; each race was restricted to separate living areas and separate public facilities. Only white South Africans were permitted to vote in national elections. Black South Africans were only represented in the local governments of remote “tribal homelands.” Interracial marriage was forbidden, blacks were legally barred from certain jobs and prohibited from forming labor unions. Passports were required for travel within the country; critics of the system could be banned from speaking in public and subjected to house arrest.

When the government ordained a deliberately inferior system of education for black students, Desmond Tutu refused to cooperate. He could no longer work as a teacher, but he was determined to do something to improve the life of his disenfranchised people. On the advice of his bishop, he began to study for the Anglican priesthood. Tutu was ordained as a priest in the Anglican church in 1960. At the same time, the South African government began a program of forced relocation of black Africans and Asians from newly designated “white” areas. Millions were deported to the “homelands,” and only permitted to return as “guest workers.”

Desmond Tutu lived in England from 1962 to 1966, where he earned a master’s degree in theology. He taught theology in South Africa for the next five years and returned to England to serve as an assistant director of the World Council of Churches in London. In 1975 he became the first black African to serve as Dean of St. Mary’s Cathedral in Johannesburg. From 1976 to 1978 he was Bishop of Lesotho. In 1978 he became the first black General Secretary of the South African Council of Churches.

This position gave Bishop Tutu a national platform to denounce the apartheid system as “evil and unchristian.” Tutu called for equal rights for all South Africans and a system of common education. He demanded the repeal of the oppressive passport laws and an end to forced relocation. Tutu encouraged nonviolent resistance to the apartheid regime and advocated an economic boycott of the country. The government revoked his passport to prevent him from traveling and speaking abroad, but his case soon drew the attention of the world. In the face of an international public outcry, the government was forced to restore his passport.

In 1984, Desmond Tutu was awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace, “not only as a gesture of support to him and to the South African Council of Churches of which he is leader, but also to all individuals and groups in South Africa who, with their concern for human dignity, fraternity and democracy, incite the admiration of the world.”

Two years later, Desmond Tutu was elected Archbishop of Cape Town. He was the first black African to serve in this position, which placed him at the head of the Anglican Church in South Africa, as the Archbishop of Canterbury is spiritual leader of the Church of England. International economic pressure and internal dissent forced the South African government to reform. In 1990, Nelson Mandela of the African National Congress was released after almost 27 years in prison. The following year the government began the repeal of racially discriminatory laws.

After the country’s first multi-racial elections in 1994, President Mandela appointed Archbishop Tutu to chair the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, investigating the human rights violations of the previous 34 years. As always, the Archbishop counseled forgiveness and cooperation, rather than revenge for past injustice.

In 1996 he retired as Archbishop of Cape Town and was named Archbishop Emeritus. For two years, he was Visiting Professor of Theology at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia. Published collections of his speeches, sermons, and other writings include Crying in the Wilderness , Hope and Suffering , and The Rainbow People of God .

In 2007, Desmond Tutu joined former South African President Mandela, former U.S. President Jimmy Carter, retired U.N Secretary General Kofi Annan, and former Irish President Mary Robinson to form The Elders, a private initiative mobilizing the experience of senior world leaders outside of the conventional diplomatic process. Tutu was named to chair the group. Carter and Tutu have traveled together to Darfur, Gaza, and Cyprus in an effort to resolve long-standing conflicts. Desmond Tutu’s historic accomplishments — and his continuing efforts to promote peace in the world — were formally recognized by the United States in 2009, when President Barack Obama named him to receive the nation’s highest civilian honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Watch a tribute to Nobel Peace Prize-winner Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s life and work. Listen to former South African President Nelson Mandela, other Nobel Peace Prize recipients, and inspiring achievers speak about the leadership of Archbishop Tutu in post-apartheid South Africa in the film Just Call Me Arch.

“We received death threats, yes, but you see, when you are in a struggle, there are going to have to be casualties, and why should you be exempt?”

When Desmond Tutu became General Secretary of the South African Council of Churches, he used his pulpit to decry the apartheid system of racial segregation. The South African government revoked his passport to prevent him from traveling, but Bishop Tutu refused to be silenced. International condemnation forced the government to rescind their decision. He had succeeded in drawing the world’s attention to the injustice of the apartheid system. In 1984, his contribution to the cause of racial equality in South Africa was recognized with the Nobel Peace Prize.

As Archbishop of Cape Town, spiritual leader of all Anglican Christians in South Africa, his spiritual authority dealt a death blow to white supremacy in South Africa. As chairman of the post-apartheid Truth and Reconciliation Commission, he helped his country to bind up its wounds, and choose forgiveness over revenge. He continues to raise his voice for peace and justice all over the world.

Being the Archbishop of Cape Town carried political responsibilities. Had you seen the black African’s struggle to end apartheid escalating from one of peace to a more forceful resistance?

Archbishop Desmond Tutu: I wasn’t really a political animal in the sense of being outraged almost all of the time but when I was at Theological College — I went to Theological College in 1958, and the year when I was going to be ordained a deacon is the year of Sharpeville, the Sharpeville Massacre when police opened fire on peaceful demonstrators against the past laws. Then, you know, you began — I mean, you intensified a sense of outrage that you had, which had developed actually even at Teacher Training College.

You see, in 1955 the ANC had this passive resistance campaign which didn’t succeed. In 1960 you had Sharpeville. You kept thinking that our white compatriots would hear — you know, would hear the pleas that were being made. I mean, we had people like Chief Albert Luthuli, who won the Nobel Peace Prize, the first South African to do so, who had been president of the ANC. And remarkably moderate really in the kind of demands that they were making, but it was — it kept falling on deaf ears, and increasingly people felt that it was going to be more and more difficult to bring about these changes peacefully.

I mean, even people like Nelson Mandela. I mean, they were striving to work for those changes nonviolently, and when they began engaging in acts of sabotage, they were very careful to ensure that they were attacking installations and not people. They tried to avoid casualties as much as possible. And it was 1960 that changed them when, after Sharpeville, and they were banned — the ANC and the PAC were banned — that they decided there was no real hope of a nonviolent end to apartheid. They were forced to take on the armed struggle, but even at that time I was not articulate, and there was an evolution.

I was appointed Dean of Johannesburg in 1975. And that — we were sufficiently political, my wife and I, because up to that point the Dean of Johannesburg had been white and the deanery was in town. My wife and I, we were in London. When we were appointed we said we’re not going to ask for permission, which we might have got, to go and live in town and the permission under — I mean, it wasn’t a right. We said, “Well, we’ll live in Soweto.” And so that — we begin always by making a political statement even without articulating it in words.

And when I arrived I realized that I had been given a platform that was not readily available to many blacks and most of our leaders were either now in chains or in exile. And I said, “Well, I’m going to use this to seek to try to articulate our aspirations and the anguishes of our people.” And I was — I mean for some reason the press were very friendly. I mean virtually anything I said it got fairly wide publicity, which was a great help.

But the thing I think that thrust me possibly into the public consciousness, I had just been elected Bishop of Lesotho. I had gone there to become bishop and I went for a retreat. I don’t know — I mean, I don’t know what happened but it just seemed like God was saying to me, “You’ve got to write a letter to the Prime Minister.” And the letter wrote itself.

In May of 1976 you wrote a letter to the Prime Minister warning of a building tension among black South African youth over the government-imposed Bantu education. What was its significance leading up to the June 16, 1976 riots?

Archbishop Desmond Tutu: I wrote the letter to the Prime Minister and told him that I was scared. I was scared because the mood in the townships was frightening. If they didn’t do something to make our people believe that they cared about our concerns I feared that we were going to have an eruption.

I sent off the letter. I probably made a technical mistake by giving it to a journalist before hearing from the Prime Minister because this journalist was working for a Sunday newspaper and gave it enormous press, and I think quite rightly the Prime Minister was annoyed that I had not given him the opportunity but never mind. He, the Prime Minister, dismissed my letter contemptuously. I wrote to him in May of 1976. I said, “I have a nightmarish fear that there was going to be an explosion if they didn’t do anything.” Well, they didn’t do anything and a month later the Soweto [uprising] happened.

The South African government for some odd reason had ignored my letter where I warned. I didn’t have any sort of premonition, although I felt there was something in the air, but when it happened, when June the 16th happened, 1976, it caught most of us really by surprise. We hadn’t expected that our young people would have had the courage. See, Bantu education had hoped that it was going to turn them into docile creatures, kowtowing to the white person, and not being able to say “boo” to a goose kind of thing, you know, and it was an amazing event when these schoolkids came out and said they were refusing to be taught in the medium of Afrikaans. That was — that was really symbolic of all of the oppression. Afrikaans was the language they felt of the oppressor, and protesting against Afrikaans was really protesting against the whole system of injustice and oppression where black people’s dignity was rubbed in the dust and trodden underfoot carelessly, and South Africa never became the same — we knew it was not going ever to be the same again, and these young people were amazing. They really were amazing.

What was it about these kids that makes you use the word “amazing?”

Archbishop Desmond Tutu: I recall that on one or two occasions, I spoke to some of them and said, “You know, are you aware that if you continue to behave in this way, they will turn their dogs on you, they will whip you, they may detain you without trial, they will torture you in their jails, and they may even kill you?,” and it was almost like privata on the part of these kids because almost all of them said, “So what. It doesn’t matter if that happens to me, as long as it contributes to our struggle for freedom,” and I think 1994, when Nelson Mandela was inaugurated as the first democratically elected president, vindicated them. It was the vindication of those 1977 remarkable kids.

When you first began to speak out publicly against the apartheid system as Bishop of Lesotho, there must have been people who said, “This is hopeless. It’s not going to make a difference. There’s nothing you can do that will ever change anything.” How did you cope with that?

Archbishop Desmond Tutu: Many of us had moments when we doubted that apartheid would be defeated, certainly not in our lifetime. But, I never had that sense. I knew in a way that was unshakable, because you see, when you look at something like Good Friday, and saw God dead on the cross, nothing could have been more hopeless than Good Friday. And then, Easter happens, and whammo! Death is done to death, and Jesus breaks the shackles of death and devastation, of darkness, of evil. And, from that moment on, you see, all of us are constrained to be prisoners of hope. If God could do this with that utterly devastating thing, the desolation of a Good Friday, of the cross, well, what could stop God then from bringing good out of this great evil of apartheid? So, I never doubted that ultimately we were going to be free because ultimately, I knew there was no way in which a lie could prevail over the truth, darkness over light, death over life.

And actually now having had the advantage of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and being able to look at some of the records of what the apartheid government was doing, the thing that is surprising to me is why so many of us survived. I mean, how is it that they did not assassinate more of us? And it is in a sense a mystery unless, of course, you say, well, God does have very strange ways of working because, I mean, they could have — you know, I mean, people say, “Well, maybe you were saved by the fact that you were in the church and you — ” and I believe that that is true.

I really would get mad with God. I would say, “I mean, how in the name of everything that is good can you allow this or that to happen?” But I didn’t doubt that ultimately good, right, justice would prevail. That I said — there were times, of course, when you had to almost sort of whistle in the dark when you wished you could say to God, “God, we know you are running the show but why don’t you make it slightly more obvious that you are doing so?”

And I mean, you know, you look and you say today there really isn’t a cause today in the world that captures the imagination, the support, the commitment of people in the way that the anti-apartheid cause did. I mean, the anti-apartheid cause was global. You could go almost anywhere in the world and you’d be sure to find an anti-apartheid group there. We are beneficiaries of an incredible amount of loving. People were ready to be arrested. They were demonstrating on our behalf. People kept vigils on our behalf. I mean you see it now in some ways — well, even before Nelson Mandela was released in 1988, Trevor Huddleston, who was my mentor and was President of the Anti-Apartheid Movement suggested that young people should come on a kind of a pilgrimage which would culminate in Hyde Park Corner on the day or very close to the day of Nelson’s birthday, the 16th, I think the 16th of July, and young people responded. Young people who most of them were not born when Nelson Mandela went to jail, in 1988, and they flocked. There must have been at least a quarter million young people congregated in Hyde Park Corner in London and Trevor Huddleston said — this was Nelson’s 70th birthday — “Let this be his last birthday in jail.” Now that was ’78 — in ’88. It’s not too bad when you think that two years later he was out. But, you know, here was a man who could command so much reverence and support especially from people — young people who had never seen him, heard him, seen pictures of him, were not born when he went to jail. That was a measure of the support that we have had.

What I have to say really bowled me over was how quickly the change happened when it happened.

One moment, Nelson Mandela is in jail, and the next moment, he is walking, a free man. One moment, we are shackled as the oppressed of apartheid; the next, we are voting for the very first time. I was 63 when I voted for the first time in my life in the country of my birth. Nelson Mandela was 76 years of age. But it happened, it happened. It happened partly because the international community supported us. People prayed for us. People demonstrated on our behalf, especially young people. Students at universities and college campuses used to sit out in the baking sunshine to force their institutions to divest and the miracle happened. We became free because we were helped and we want to say a big “thank you” to the world. And, you can become free nonviolently.

Did you and Nelson Mandela meet for the first time after he was released from imprisonment in 1990?

Archbishop Desmond Tutu: I had seen him only once before, before he got arrested, in the 1950s when he adjudicated at a debating contest, and I was part of that. I never saw him really again, although now our houses in Soweto are not so very far apart. In 1990, I think it’s the 11th of February, he came out and came to spend his first night in the house which was the official residence of the Archbishop of Cape Town, and I was the Archbishop of Cape Town! He was ensconced with the leadership of his party, the African National Congress, and now and again, they would be interrupted. There is a phone call. This is the White House, and there is a phone call. This is the Statehouse in Lusaka. I mean, he was getting telephone calls congratulating him and wishing him well, and he then had his first — on the Monday, he had his first press conference as a free man on the lawns of Bishop’s Court. Sort of, that was the extent of our meeting. I mean, I met him in the morning just to say “hi,” but what I do remember is he went around thanking the people, my staff, for, you know, people who had cooked their meals. He’s always been gracious in that kind of way, but this is sort of the first time I saw his charm working on people.

There were times when you were subjected at the least to fierce criticism, and there were times when you must have feared for your life. How do you deal with that?

Archbishop Desmond Tutu: We received death threats, yes, but you see when you are in a struggle, there are going to have to be casualties, and why should you be exempt? But I often said, “Look, here, God, if I’m doing your work, then you jolly well are going to have to look after me!” And God did God’s stuff. But it was — I mean people prayed. People prayed. You know, there’s a wonderful image in the Book of the Prophet Zechariah, where he speaks about Jerusalem not having conventional walls, and God says to this overpopulated Jerusalem, “I will be like a wall of fire ’round you.” Frequently in the struggle, we experienced a like wall of fire — people all over the world surrounding us with love. And you know that image of the Prophet Elijah — he is surrounded by enemies, and his servant is scared, and Elijah says to God, “Open his eyes so that he should see,” and God opens the eyes of the servant, and the servant looks, and he sees hosts and hosts and hosts of angels. And the prophet says to him, “You see? Those who are for us are many times more than those against us.”

When you first began, you knew what you were trying to do, and you perhaps had some idea of what you thought it would take to achieve this goal. Now that the goal of ending apartheid and creating democracy in South Africa is achieved, what do you know now that you didn’t know before?

Archbishop Desmond Tutu: I have come to realize the extraordinary capacity for evil that all of us have because we have now heard the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and there have been revelations of horrendous atrocities that people have committed. Any and every one of us could have perpetrated those atrocities. The people who were perpetrators of the most gruesome things didn’t have horns, didn’t have tails. They were ordinary human beings like you and me. That’s the one thing. Devastating! But the other, more exhilarating than anything that I have ever experienced — and something I hadn’t expected — to discover that we have an extraordinary capacity for good. People who suffered untold misery, people who should have been riddled with bitterness, resentment and anger come to the Commission and exhibit an extraordinary magnanimity and nobility of spirit in their willingness to forgive, and to say, “Hah! Human beings actually are fundamentally good.” Human beings are fundamentally good. The aberration, in fact, is the evil one, for God created us ultimately for God, for goodness, for laughter, for joy, for compassion, for caring.

- 33 photos

Remembering Desmond Tutu’s life and legacy

PBS NewsHour PBS NewsHour

Leave your feedback

- Copy URL https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/remembering-desmond-tutus-life-and-legacy

Former Archbishop Desmond Tutu, South Africa’s Nobel Peace Prize-winning icon, died Sunday at 90. Tutu’s passionate voice helped end South Africa’s brutal apartheid regime that oppressed its Black majority for decades. World leaders, South Africans and people around the globe mourned his death and praised the life he lived and the legacy he leaves behind, including his more recent work as an activist for racial justice and LGBTQ rights. NewsHour Special Correspondent Charlayne Hunter-Gault joins.

Read the Full Transcript

Notice: Transcripts are machine and human generated and lightly edited for accuracy. They may contain errors.

Desmond Tutu:

We raise our hands and we say 'we will be free, all of us, Black and white together, for we are marching to freedom.'

Michael Hill:

Archbishop Desmond Tutu was an Anglican bishop and a leader of the anti-Apartheid movement in South Africa. Born in 1931, he followed in his father's footsteps, becoming a high school teacher. He then switched paths to become an Anglican priest. Tutu was on the frontline fighting for freedom and equality in South Africa, where racially segregated apartheid began in 1948.

We know, we know, we shall overcome the evil.

In 1984, tutu won the Nobel Peace Prize for his role in advocating for non-violent protest to end the brutal practice of white-minority rule.

Welcome our brand new state president, out of the box, Nelson Mandela!

In 1994, South Africa elected its first black president Nelson Mandela. Tutu said voting in that democratic election was "like falling in love." The two were counterparts in the struggle for freedom.

After Mandela's election, the Archbishop chaired the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, investigating crimes of the apartheid era. He delivered the final report to Mandela in 1998.

Tutu advocated for racial justice and LGBTQ rights globally. Tutu died from complications from prostate cancer, which he was first diagnosed with in 1997. When asked how he would like to be remembered, Tutu answered:

He loved, he laughed, he cried, he was forgiven, he forgave.

For more on the life of Archbishop Desmond Tutu, I spoke with NewsHour Special Correspondent Charlayne Hunter-Gault. Thank you so much for joining us. I have to ask you this where would the end of apartheid be if it had not been for Desmond Tutu?

Charlayne Hunter-Gault:

Well, we may still be involved in it, but actually, I think that one of the things that Desmond Tutu, and I am so sorry to hear he has transitioned as the South Africans say they never used the term dead or death, but I think that so much changed as a result of his work. And yet, like in America, we go around in circles, sometimes trying to get a more perfect union. And so I think that at the time that Archbishop Tutu was very active, especially with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, it was the time to set South Africa on a new path. And sometimes, as you would know, the paths have rubbish on them. But his principles were those that enabled those who cared about the things that he did to sweep away that rubbish in the past. So it never goes away. South Africa is having a rough time today as we are here in America, but there are people who have given us lessons to survive even the worst of times. And he was one of those.

You know, he chaired this Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa on behalf of the president at the time, Nelson Mandela. And he wrote in one of his reports, Tutu did, not to judge the morality of people's actions, but to act as an incubation chamber for national healing, reconciliation and forgiveness. But that didn't sit well with a lot of South Africans, though.

Well, it didn't, but it didn't dissuade him from, you know, as a preacher's kid, a PK, which I am, I always understood what moved Archbishop Tutu. And it was his faith. And his faith taught him to have faith in people. And those could be people whom he wanted to help have support him, but others who he knew it was going to be a challenge to achieve. And so as we have here in America today, we have a younger generation that wants things to happen a lot faster, the equality that we've been promised in our constitution. And the same is true in South Africa. So you had people on all sides of the, shall we say, the freedom equation. But he understood all of that and he never criticized them. He always said he understood their impatience. And yet he continued on his path toward reconciliation because he thought that that was probably the most important thing that could happen in the country, reconciliation. And although not everybody bought into it, he did help prepare the country for one of the greatest presidents who ever lived, Nelson Mandela. And he also helped to ease the transition in so many ways.

Charlayne, tell us, what was it like when you first met him in his younger days and you were in South Africa?

I think he was about six or seven years old at the time and had a very young spirit. In fact, when he was running the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, we learned from him that he had prostate cancer. And he said that probably the best kind of healer is a wounded healer. And what surprised me more than anything was as challenging as the country was at the time and as serious as the position that he had to determine what South Africans could do going forward, he was always positive and he had a great sense of humor. I mean, you can find pictures of him just laughing. And that's what struck me often in the meetings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which I attended. Although it was all very serious, he would find humor in some things, and I think that helped in many ways to ease the tension. So he was a man of many different attitudes and positions, and I think all of that made him a very successful person in the efforts that he was trying to achieve. And we'll always remember him for what he contributed to a new South Africa.

We've been speaking with Charlayne Hunter-Gault on the passing of Desmond Tutu. Charlayne, thank you.

Thank you for having me. It's a real pleasure to talk about such a great man.

Listen to this Segment

Watch the Full Episode

Support Provided By: Learn more

More Ways to Watch

- PBS iPhone App

- PBS iPad App

Educate your inbox

Subscribe to Here’s the Deal, our politics newsletter for analysis you won’t find anywhere else.

Thank you. Please check your inbox to confirm.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Desmond Tutu, Whose Voice Helped Slay Apartheid, Dies at 90

The archbishop, a powerful force for nonviolence in South Africa’s anti-apartheid movement, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984.

By Marilyn Berger

Desmond M. Tutu, the cleric who used his pulpit and spirited oratory to help bring down apartheid in South Africa and then became the leading advocate of peaceful reconciliation under Black majority rule, died on Sunday in Cape Town. He was 90.

His death was confirmed by the office of South Africa’s president, Cyril Ramaphosa, who called the archbishop “a leader of principle and pragmatism who gave meaning to the biblical insight that faith without works is dead.”

The cause of death was cancer, the Desmond and Leah Tutu Legacy Foundation said, adding that Archbishop Tutu had died in a care facility. He was first diagnosed with prostate cancer in 1997, and was hospitalized several times in the years since, amid recurring fears that the disease had spread.

As leader of the South African Council of Churches and later as Anglican archbishop of Cape Town, Archbishop Tutu led the church to the forefront of Black South Africans’ decades-long struggle for freedom. His voice was a powerful force for nonviolence in the anti-apartheid movement, earning him a Nobel Peace Prize in 1984 .

When that movement triumphed in the early 1990s, he prodded the country toward a new relationship between its white and Black citizens, and, as chairman of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, he gathered testimony documenting the viciousness of apartheid.

“You are overwhelmed by the extent of evil,” he said. But, he added, it was necessary to open the wound to cleanse it. In return for an honest accounting of past crimes, the committee offered amnesty, establishing what Archbishop Tutu called the principle of restorative — rather than retributive — justice.

His credibility was crucial to the commission’s efforts to get former members of the South African security forces and former guerrilla fighters to cooperate with the inquiry.

Archbishop Tutu preached that the policy of apartheid was as dehumanizing to the oppressors as it was to the oppressed. At home, he stood against looming violence and sought to bridge the chasm between Black and white; abroad, he urged economic sanctions against the South African government to force a change of policy.

But as much as he had inveighed against the apartheid-era leadership, he displayed equal disapproval of leading figures in the dominant African National Congress, which came to power under Nelson Mandela in the first fully democratic elections in 1994.

In 2004, the archbishop accused President Thabo Mbeki, Mr. Mandela’s successor, of pursuing policies that enriched a tiny elite while “many, too many, of our people live in grueling, demeaning, dehumanizing poverty.”

“We are sitting on a powder keg,” he said.

Although he and Mr. Mbeki later reconciled — they were photographed together in 2015 as Mr. Mbeki, by then the former president, visited Archbishop Tutu in a hospital — the archbishop remained unhappy about the state of affairs in his country under its next president, Jacob G. Zuma, who had denied Mr. Mbeki another term despite being embroiled in scandal.

“I think we are at a bad place in South Africa,” Archbishop Tutu told The New York Times Magazine in 2010, “and especially when you contrast it with the Mandela era. Many of the things that we dreamed were possible seem to be getting more and more out of reach. We have the most unequal society in the world.”

Then, in 2011, as critics accused the A.N.C. of corruption and mismanagement, Archbishop Tutu again assailed the government, this time in terms that would have once been unimaginable. “This government, our government, is worse than the apartheid government,” he said, “because at least you were expecting it with the apartheid government.”

He added: “Mr. Zuma, you and your government don’t represent me. You represent your own interests. I am warning you out of love, one day we will start praying for the defeat of the A.N.C. government. You are disgraceful.”

His words seemed prophetic when, in 2016, an alliance of religious leaders in South Africa joined other critics in urging Mr. Zuma to quit. In early 2018, Mr. Zuma was ousted after a power struggle with his deputy, Mr. Ramaphosa, who took over the presidency in February of that year.

By then, Archbishop Tutu had largely stopped giving interviews because of failing health and rarely appeared in public. But a few months after Mr. Ramaphosa was sworn in as the new president with the promise of a “new dawn” for the nation, the archbishop welcomed him at his home.

“Know that we pray regularly for you and your colleagues that this must not be a false dawn,” Archbishop Tutu warned Mr. Ramaphosa.

At that time, support for the African National Congress had declined, even though it remained the country’s biggest political party. In elections in 2016 , while still under the leadership of Mr. Zuma, the party’s share of the vote slipped to its lowest level since the end of apartheid. Mr. Ramaphosa struggled to reverse that trend, but earned some praise later for his robust handling of the coronavirus crisis.

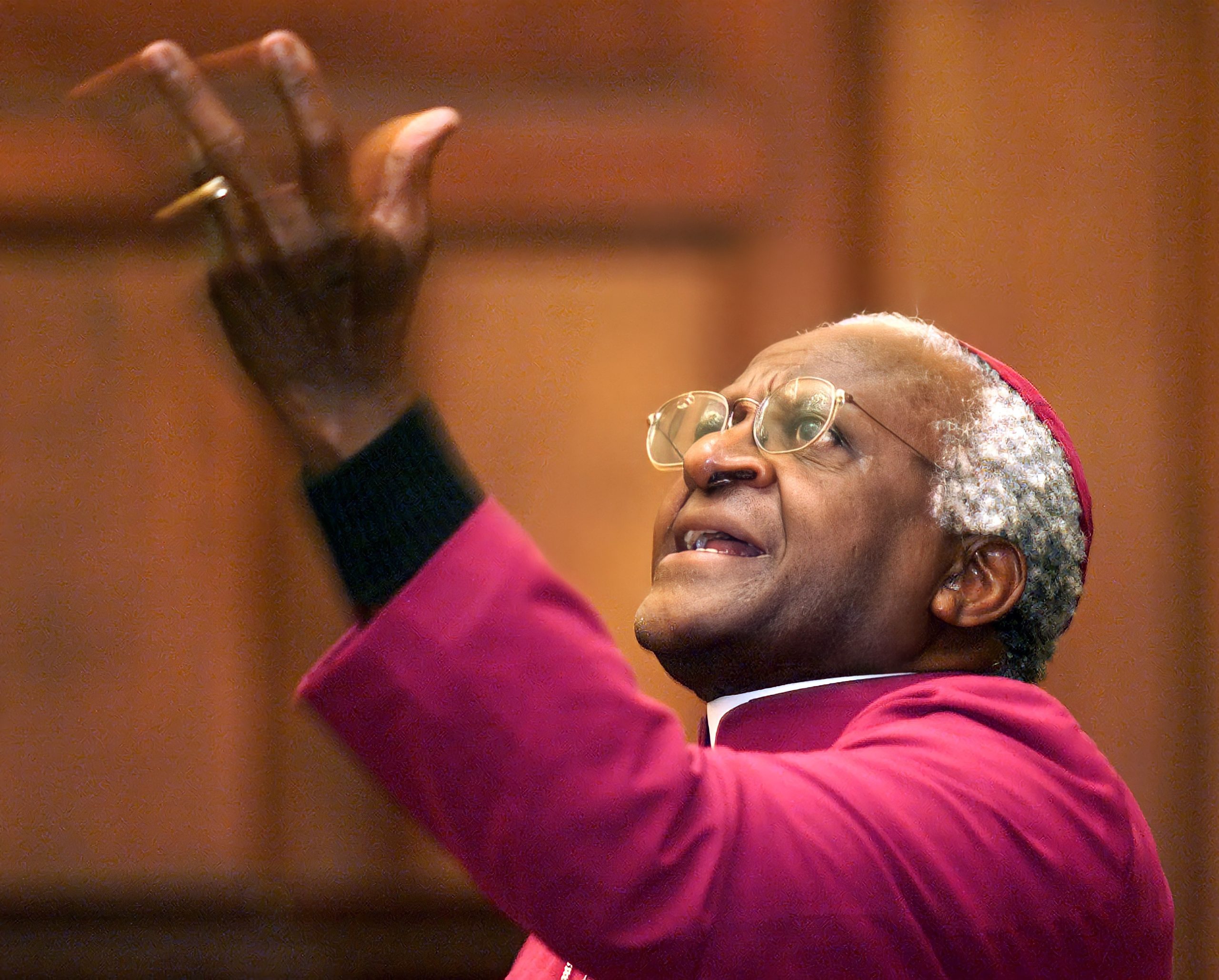

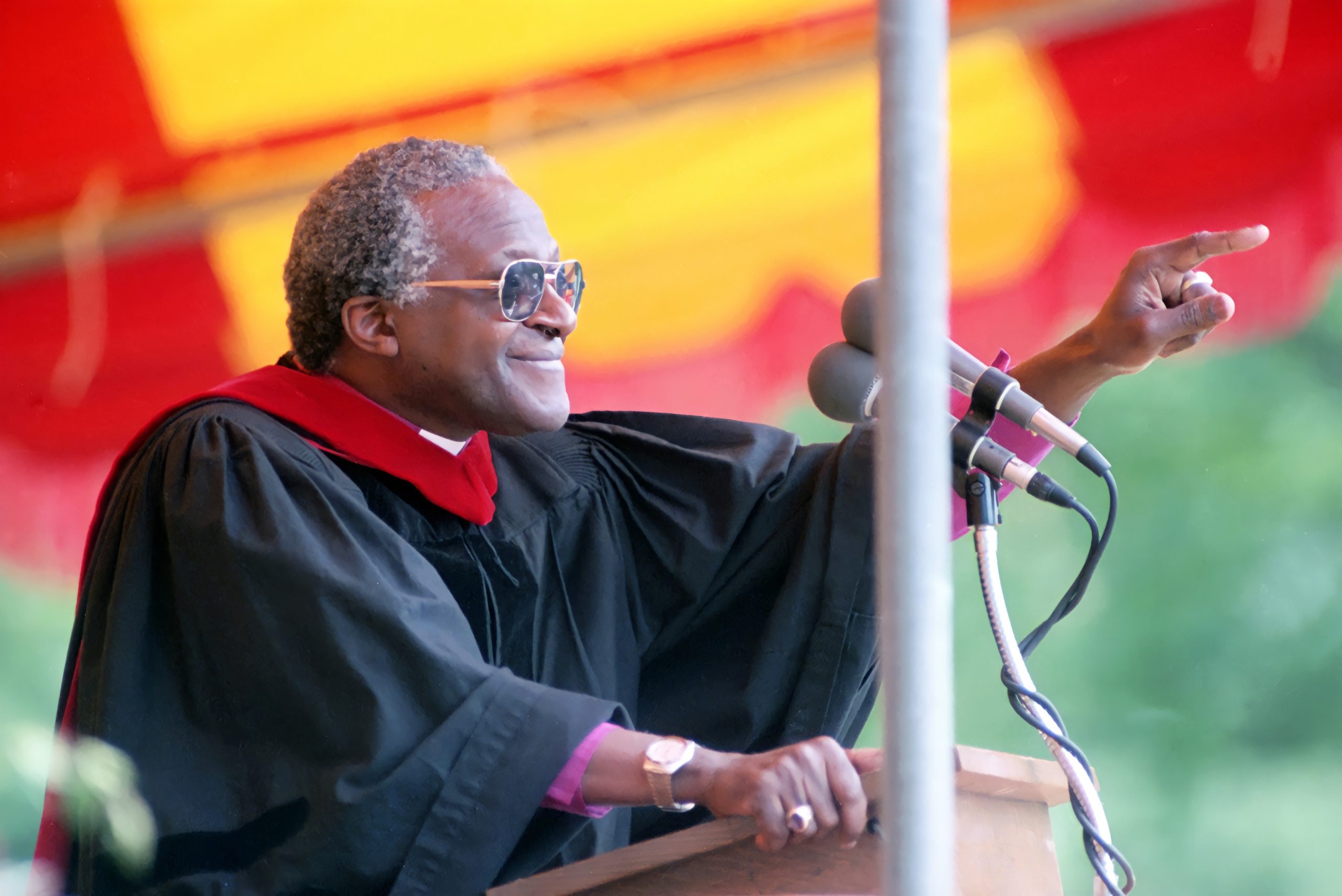

A Global Celebrity

For much of his life, Archbishop Tutu was a spellbinding preacher, his voice by turns sonorous and high-pitched. He often descended from the pulpit to embrace his parishioners. Occasionally he would break into a pixielike dance in the aisles, punctuating his message with the wit and the chuckling that became his hallmark, inviting his audience into a jubilant bond of fellowship. While assuring his parishioners of God’s love, he exhorted them to follow the path of nonviolence in their struggle.

Politics were inherent in his religious teachings. “We had the land, and they had the Bible,” he said in one of his parables. “Then they said, ‘Let us pray,’ and we closed our eyes. When we opened them again, they had the land and we had the Bible. Maybe we got the better end of the deal.”

His moral leadership, combined with his winning effervescence, made him something of a global celebrity. He was photographed at glittering social functions, appeared in documentaries and chatted with talk-show hosts. Even in late 2015, when his health seemed poor, he met with Prince Harry of Britain, who presented him with an honor on behalf of Queen Elizabeth II.

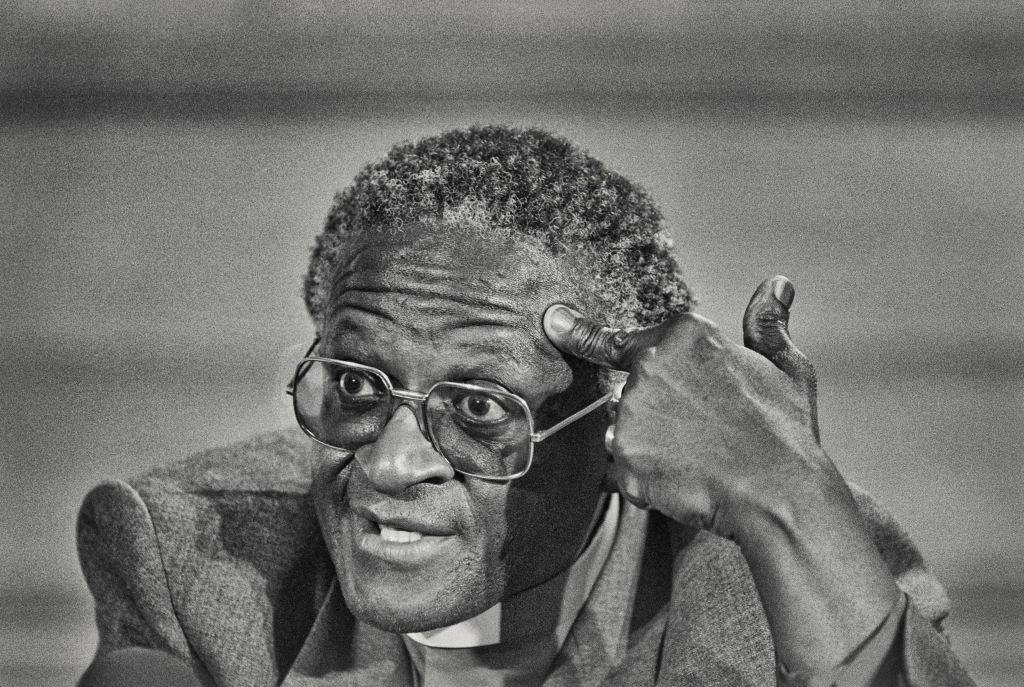

A compact, restless man — for many years he kept fit by jogging at 4:30 every morning — Archbishop Tutu had piercing eyes that were barely concealed by rimless glasses. When he traveled abroad, he cut a handsome figure in his well-tailored gray suit over a magenta shirt with a white clerical collar.

Apparently convinced of the virtues of modesty, he never seemed to accustom himself to the perquisites of fame and high office. He was unfailingly on time, always expressed appreciation to the bellhops and maids sent to wait on him, and was uncomfortable with limousines and police escorts.

“You know, back home, when you hear a police siren, you figure that they are coming to get you,” he once told a reporter from The Washington Post. “It still makes me a bit nervous riding with them.”

Although Archbishop Tutu, like other Black South Africans of his era, had suffered through the horrors and indignities of apartheid, he did not allow himself to hate his enemies. When he was young, he said, he was fortunate in the white priests that he knew, and throughout the long struggle against apartheid he remained an optimist. “Justice, goodness, love, compassion must prevail,” he said during a visit to New York in 1990. “Freedom is breaking out. Freedom is coming.”

He coined the phrase “rainbow nation” to describe the new South Africa emerging into democracy, and called for vigorous debate among all races.

Archbishop Tutu had always said that he was a priest, not a politician, and that when the real leaders of the movement against apartheid returned from jail or exile he would serve as its chaplain. While he acknowledged that there was a political role for the church, he prohibited ordained clergy from belonging to any political party.

In 1989, after President F.W. de Klerk had at last started to dismantle apartheid, Archbishop Tutu stepped aside, handing the leadership of the struggle back to Mr. Mandela on his release from prison in 1990.

But Archbishop Tutu did not stay entirely out of the nation’s business. “We’ve struggled to get these guys where they are, and we’re not going to let them fail,” he said. “We didn’t swallow all that tear gas, and be chased around and be sent to jail and into exile and killed, for failure.”

From Teacher to Preacher

Desmond Mpilo Tutu was born on Oct. 7, 1931, in Klerksdorp, on the Witwatersrand in what is now the North West Province of South Africa. His mother, Aletha, was a domestic worker; his father, Zachariah, taught at a Methodist school. The young Desmond was baptized a Methodist, but the entire family later joined the Anglican Church. When he was 12 the family moved to Johannesburg, where his mother found work as a cook in a school for the blind.

While he never forgot his father’s shame when a white policeman called him “boy” in front of his son, he was even more deeply affected when a white man in a priest’s robe tipped his hat to his mother, he said.

The white man was the Rev. Trevor Huddleston , a prominent campaigner against apartheid. When Desmond was hospitalized with tuberculosis, Father Huddleston visited him almost every day. “This little boy very well could have died,” Father Huddleston told an interviewer many years later, “but he didn’t give up, and he never lost his glorious sense of humor.”

After his recovery, Desmond wanted to become a doctor, but his family could not afford the school fees. Instead he became a teacher, studying at the Pretoria Bantu Normal College and earning a bachelor’s degree from the University of South Africa. He taught high school for three years but resigned to protest the Bantu Education Act, which lowered education standards for Black students.

By then he was married to Nomalizo Leah Shenxane, a major influence in his life; the couple celebrated 60 years of marriage by publicly renewing their wedding vows in July 2015. She survives him, as do their four children: a son, Trevor Thamsanqa Tutu, and three daughters, Theresa Thandeka Tutu, Naomi Nontombi Tutu and Mpho Tutu van Furth, as well as seven grandchildren.

Archbishop Tutu turned to the ministry, he said, because he thought it could provide “a likely means of service.” He studied at St. Peter’s Theological College in Johannesburg and was ordained an Anglican priest at St. Mary’s Cathedral in December 1961, less than two years after protests convulsed the town of Sharpeville, 40 miles from Johannesburg.

After serving in local churches, he studied in England, where he earned a bachelor of divinity degree and a master’s in theology from King’s College in London. When he returned to South Africa he was a lecturer, and from 1972 to 1975 he served as associate director of the Theological Education Fund, traveling widely in Asia and Africa and administering scholarships for the World Council of Churches.

He was named Anglican dean of Johannesburg in 1975 and consecrated bishop of Lesotho the next year. In 1978 he became the first Black general secretary of the South African Council of Churches, and began to establish the organization as a major force in the movement against apartheid.

Under Bishop Tutu’s leadership, the council established scholarships for Black youths and organized self-help programs in Black townships. There were also more controversial programs: Lawyers were hired to represent Black defendants on trial under the security laws, and support was provided for the families of those detained without trial.

As bishop, he spoke out against the establishment of tribal “homelands” and used the council as a platform to urge foreign investors to pull out of South Africa.

A month after he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984, Desmond Tutu became the first Black Anglican bishop of Johannesburg when the national church hierarchy intervened to break a deadlock between Black and white electors. He was named archbishop of Cape Town in 1986, becoming spiritual head of the country’s 1.5 million Anglicans, 80 percent of whom were Black.

He preached forbearance but, as he insisted to The Christian Century magazine in 1980, “I am a man of peace, but not a pacifist.”

In an interview in the early 1980s, he said: “Blacks don’t believe that they are introducing violence into the situation. They believe that the situation is already violent.”

“I will never tell someone to pick up a gun,” he said in another interview “But I will pray for the man who picks up the gun, pray that he will be less cruel than he might otherwise have been, because he is a member of the community. We are going to have to decide: If this civil war escalates, what is our ministry going to be?”

He demonstrated his personal bravery in 1985 when, still a bishop, he helped to rescue a Black police informer from a mob in Duduza, a South African township.

Archbishop Tutu also spoke out against President Ronald Reagan’s policy of “constructive engagement,” which was intended to show impartiality in South African domestic affairs for what were said to be strategic purposes.

“To be impartial,” he said, “is indeed to have taken sides already with the status quo. How are you to remain impartial when the South African authorities evict helpless mothers and children and let them shiver in the winter rain?”

He remained equally outspoken even in later years. In 2003 he criticized his own government for backing Zimbabwe’s president, Robert Mugabe, who had a long record of human rights abuses.

In 2010 he unsuccessfully urged a touring Cape Town opera company not to perform in Israel , invoking South Africa’s struggle against apartheid in criticizing Israel’s policy toward Palestinians. He said that the company’s production of “Porgy and Bess” should be postponed “until both Israeli and Palestinian opera lovers of the region have equal opportunity and unfettered access to attend performances.”

Man of Forgiveness

Archbishop Tutu was the author of many books, including collections of his sermons and addresses, illustrated children’s books and forward-looking works about South Africa like “God Has a Dream: A Vision of Hope for Our Time” (2004) and “Made for Goodness” (2010), which he wrote with his daughter Mpho, an Episcopal priest. (She was forced to give up her priest’s license in South Africa after marrying a woman.)

On his frequent trips abroad during the apartheid era, Archbishop Tutu never stopped pressing the case for sanctions against South Africa. The government struck back and twice revoked his passport, forcing him to travel with a document that described his citizenship as “undetermined.”

But as the author of a 1999 book titled “No Future Without Forgiveness,” he was generous in forgiving his enemies, and when the de Klerk government took steps in 1989 toward ending apartheid, Archbishop Tutu was among the first to welcome the prospect of change.

“An extraordinary thing has happened in South Africa,” he said in 1990,“and it is undoubtedly due to the courage of President de Klerk. We’ve got someone here who is greater than we expected. At some points we had to pinch ourselves to be sure we were seeing what we were seeing.”

Still, when the Truth and Reconciliation Commission issued its final findings in 2003 , Archbishop Tutu’s imprint was plain. It warned the government against issuing a blanket amnesty to perpetrators of the crimes of apartheid and urged businesses to join with the government in delivering reparations to the millions of Black people victimized by the former white minority government.

The report further said that Mr. de Klerk had knowingly withheld information from the commission about state-sponsored violations, and it reiterated charges against the Zulu-based Inkatha Freedom Party, South Africa’s second-largest Black party, accusing it of having collaborated with white supremacists in the massacre of hundreds of people in the early 1990s.

Archbishop Tutu officially retired from public duties in 2010 . One of his last major appearances came that year, when South Africa hosted the World Cup.

But he did not retreat from the public eye entirely. In June 2011, he joined Michelle Obama at the new Cape Town Stadium, built for the tournament, where she was promoting physical fitness during a tour of southern Africa.

Inside the stadium, Ms. Obama got down on the floor to perform a few push-ups, and Archbishop Tutu, seeming keen to join in, dropped to the floor and did the same. Rising to their feet, a bit winded, they congratulated each other with a fist bump.

Archbishop Tutu continued to make occasional forays into the limelight, even as he grew more infirm.

In 2021, as he approached his 90th birthday, he pitched into a fraught debate as disinformation about coronavirus vaccines swirled.

“There is nothing to fear,” he said. “Don’t let Covid-19 continue to ravage our country, or our world. Vaccinate.”

Alan Cowell and Lynsey Chutel contributed reporting.

An earlier version of this obituary erroneously credited Bishop Tutu with a distinction. He was the first Black Anglican bishop of Johannesburg — not the first Anglican bishop.

How we handle corrections

- Election 2024

- Entertainment

- Newsletters

- Photography

- Personal Finance

- AP Investigations

- AP Buyline Personal Finance

- AP Buyline Shopping

- Press Releases

- Israel-Hamas War

- Russia-Ukraine War

- Global elections

- Asia Pacific

- Latin America

- Middle East

- Election Results

- Delegate Tracker

- AP & Elections

- Auto Racing

- 2024 Paris Olympic Games

- Movie reviews

- Book reviews

- Personal finance

- Financial Markets

- Business Highlights

- Financial wellness

- Artificial Intelligence

- Social Media

Desmond Tutu: Timeline of a life committed to equality

People place flowers alongside a photo of Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu at the St. George’s Cathedral in Cape Town, South Africa, Sunday, Dec. 26, 2021. South Africa’s president says Tutu, South Africa’s Nobel Peace Prize-winning activist for racial justice and LGBT rights and the retired Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town, has died at the age of 90. (AP Photo)

FILE - Former South African President Nelson Mandela, right, reacts with Archbishop Desmond Tutu during the launch of a Walter and Albertina Sisulu exhibition, called, ‘Parenting a Nation’, at the Nelson Mandela Foundation in Johannesburg, South Africa, Wednesday, March 12, 2008. Tutu, South Africa’s Nobel Peace Prize-winning activist for racial justice and LGBT rights and the retired Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town, has died at the age of 90, it was announced on Sunday, Dec. 26, 2021. An uncompromising foe of apartheid, South Africa’s brutal regime of oppression again the Black majority, Tutu worked tirelessly, but non-violently, for its downfall.(AP Photo/Themba Hadebe, File)

FILE - Former South Africa president Nelson Mandela, center, is reunited with The Elders, three years after he launched the group, in Johannesburg, South Africa Saturday, May 29, 2010. From left back row, former Brazilian president Fernando Henrique Cardoso, former US president Jimmy Carter, former Irish president Mary Robinson, former secretary-general of the UN Kofi Annan, former prime minister of Norway Gro Brundtland, former president of Finland Martti Ahtisaari and UN ambassador Lakhdar Brahimi. In front row Mandela’s wife, Graca Machel, South African cleric Desmond Tutu, Nelson Mandela, and Indian philanthropist Ela Bhatt, right. South Africa’s Nobel Peace Prize-winning activist for racial justice and LGBT rights and the retired Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town, has died at the age of 90, it was announced on Sunday, Dec. 26, 2021. An uncompromising foe of apartheid, South Africa’s brutal regime of oppression again the Black majority, Tutu worked tirelessly, but non-violently, for its downfall. (AP Photo/Jeff Moore, Pool)

A woman stands outside the the historical home of Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu, in Soweto, Johannesburg, South Africa, Sunday, Dec. 26, 2021. South Africa’s president says Tutu, South Africa’s Nobel Peace Prize-winning activist for racial justice and LGBT rights and the retired Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town, has died at the age of 90. (AP Photo)

People take photos at a statue of Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu at the V&A Waterfront in Cape Town, South Africa, Sunday, Dec. 26, 2021. South Africa’s president says Tutu, South Africa’s Nobel Peace Prize-winning activist for racial justice and LGBT rights and the retired Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town, has died at the age of 90. (AP Photo)

Flowers are placed alongside a photo of Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu at the St. George’s Cathedral in Cape Town, South Africa, Sunday, Dec. 26, 2021. South Africa’s president says Tutu, South Africa’s Nobel Peace Prize-winning activist for racial justice and LGBT rights and the retired Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town, has died at the age of 90. (AP Photo)

- Copy Link copied

JOHANNESBURG (AP) — 1931 - Oct. 7 - Desmond Mpilo Tutu is born in Klerksdorp, near Johannesburg.

1947 – Contracts tuberculosis, as he recuperates he is visited by Trevor Huddleston, a British Anglican pastor working in South Africa.

1955 – Marries Nomalizo Leah Shenxane and begins teaching at a secondary school in Johannesburg.

1961 - Is ordained as a minister in the Anglican church, after quitting teaching in disgust at South Africa’s apartheid government’s inferior education for Blacks.

1962 – Studies theology at King’s College London.

1966 – Returns to South Africa to teach at a seminary in the Eastern Cape.

1975 – Becomes the Anglican church’s first Black dean of Johannesburg.

1976 - Serves as Bishop of Lesotho and voices criticism of apartheid in South Africa.

1978 - Becomes general-secretary of the South African Council of Churches and achieves global prominence as a leading opponent of apartheid, supports economic sanctions to achieve majority rule in South Africa.

1984 - Wins Nobel Peace Prize - “There is no peace in southern Africa. There is no peace because there is no justice. There can be no real peace and security until there be first justice enjoyed by all the inhabitants of that beautiful land,” Tutu says in his acceptance speech.

1985 – Becomes the first Black bishop of Johannesburg.

1986 - Is ordained the first Black Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town.

1989 - Leads anti-apartheid march of 30,000 people through Cape Town.

1990 - Hosts Nelson Mandela for his first night of freedom after Mandela is released from prison after being held for 27 years for his opposition to apartheid. Mandela calls Tutu “the peoples’ archbishop.”

1994 - Votes in South Africa’s first democratic election in which all races can cast ballots.

1995 - President Nelson Mandela appoints Tutu to be chairman of the country’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

1996 - Tutu retires as prelate, the Anglican church gives him the title of Archbishop Emeritus of Cape Town.

1997 - Is diagnosed with prostate cancer and announces it to help with public awareness of the disease.

1998 - Truth and Reconciliation Commission publishes its report, putting most of the blame for abuses on the forces of apartheid, but also finds the African National Congress guilty of human rights violations. The ANC sues to block the document’s release, earning a rebuke from Tutu.

2009 - Aug. 12 - Receives the Presidential Medal of Freedom from U.S. President Barack Obama.

2010 - July 22 - Retires from public life, tells press: “Don’t call me, I’ll call you.”

2013 - Launches international campaign for LGBTQ rights in Cape Town. “I would not worship a God who is homophobic.”

2014 - July 12 - Urges the British parliament to allow assisted dying, saying “the manner of Nelson Mandela’s prolonged death was an affront.”

2021 - Oct. 7 - Frail, in a wheelchair, Tutu attends his 90th birthday celebration at St. George’s Cathedral in Cape Town.

2021 - Dec. 26 - Tutu dies in Cape Town.

- remembrance

Desmond Tutu, Anti-Apartheid Campaigner Who Tried to Heal the World, Dies at 90

S outh African anti-apartheid campaigner, Nobel Peace Prize laureate and Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu , one of the world’s most revered religious leaders, died in Cape Town on Sunday at age 90, bringing to an end an extraordinary life filled with courage, love and a passion for justice.

South African President Cyril Ramaphosa announced Tutu’s death, saying it marks “another chapter of bereavement in our nation’s farewell to a generation of outstanding South Africans who have bequeathed us a liberated South Africa.” Fellow anti-apartheid campaigner Nelson Mandela died in 2013, and F.W. de Klerk—the last white South African president, who worked to dismantle the South African government’s apartheid system— died in November .

Ramaphosa paid tribute to Tutu’s work, both in ending apartheid and in fighting for human rights everywhere: “A man of extraordinary intellect, integrity and invincibility against the forces of apartheid, he was also tender and vulnerable in his compassion for those who had suffered oppression, injustice and violence under apartheid, and oppressed and downtrodden people around the world.”

Tutu had been hospitalized several times in recent years following a 1997 prostate cancer diagnosis.

A globally recognized icon of peaceful resistance to injustice, Tutu is best remembered for his courageous leadership of the Anglican Church in South Africa even as he spearheaded the fight against apartheid. Like fellow human rights activists Mahatma Ghandi and Martin Luther King Jr., he used his religion as a platform to advocate for equality and freedom for all South Africans, regardless of race. He often noted that the apartheid system, while devastating for South Africa’s blacks, was nearly as corrosive to the spiritual, physical and political development of the white population it was supposed to protect. “Whites, in being those who oppress others, dehumanized themselves,” he was quoted as saying .

Deftly wielding the Christian principles of love and forgiveness as a weapon in his fight to dismantle apartheid, he regularly, and publicly, prayed for the wellbeing of his opponents, even those who were most vociferous in their attacks against him. But even as he preached forgiveness, he was uncompromising when it came to his fundamental moral philosophy. “You are either in favour of evil, or you are in favour of good. You are either on the side of the oppressed or on the side of the oppressor. You can’t be neutral,” he wrote in a statement to the United States Congress in 1984. He expanded his thinking in later speeches and sermons, noting that “If an elephant has its foot on the tail of a mouse and you say that you are neutral, the mouse will not appreciate your neutrality.”

READ MORE: The Secret to Joy, According to the Dalai Lama and Desmond Tutu

It was a philosophy that continued to animate his activism long after the end of apartheid. When full democracy finally came to South Africa in 1994, Tutu applied his elder-statesman stature and boundless energy to advocate for social justice and equality globally, taking on issues of HIV/AIDS treatment and prevention, climate change and the right of the terminally ill to die with dignity. He became a globe-trotting peace advocate, pushing for justice, freedom and an end to conflict in Israel-Palestine, Rwanda, Burma and Iraq. He campaigned against the United States’ illegal detention of suspected terrorists in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, and became an outspoken supporter of LGBTQ rights, even as he risked conflict with members of his own church. “Opposing apartheid was a matter of justice,” he said in 2006 . “Opposing discrimination against women is a matter of justice. Opposing discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation is a matter of justice.” Though Tutu was routinely confronted with some of the most egregious aspects of human behavior at home and in his travels , he never lost his faith in his fellow man. “Despite all of the ghastliness in the world, human beings are made for goodness,” he once said.

His sermons, unfailingly lucid, penetrating and inspired, went beyond the homily of the day to encompass the news of the world. A tremendous orator, he wove jokes, observations and passion into his speeches, deftly conducting his audiences into a state of uproar over injustice. Once there, he gently directed the heightened emotions towards constructive action. As the title of his authorized biography, published to great acclaim in 2006, put it: He was a rabble rouser for peace . As Mandela said: “Sometimes strident, often tender, never afraid and seldom without humor, Desmond Tutu’s voice will always be the voice of the voiceless.”

Born on Oct. 7, 1931, to a school headmaster and a domestic servant in Klerksdorp, South Africa, Desmond Mpilo Tutu grew up to become a teacher like his father. But when the South African government started instituting discriminatory education policies that restricted black South Africans’ employment opportunities, he quit in disgust. In 1958 he enrolled at a theological college instead, and in 1961 was ordained as priest in the Anglican church. A year later he left South Africa to continue his studies in London, where he experienced, for the first time, a life of freedom from apartheid’s race-based restrictions. “I’m sure there was racism there,” he noted in his biography. “But we were protected by the church. It was marvelous. We didn’t have to carry our passes anymore and we did not have to look around to see if we could use that bath or that exit. It was a tremendously liberating thing.”

More from TIME

Tutu returned to Africa in 1975, and became the Anglican Bishop of the country of Lesotho. Two years later he returned to South Africa, where he was elected to become the first Black secretary general of the South African Council of Churches. His elevated position in the church enabled him to advocate for an end of apartheid while granting him a certain degree of protection from the South African authorities. With most of the leaders of the anti-apartheid movement jailed or in exile, Tutu become the movement’s de facto head, and a leading spokesperson for the rights of Black South Africans. His unstinting efforts to draw national and international attention to apartheid’s discrimination earned him the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984 . The awards committee said it was meant, “not only as a gesture of support to him and to the South African Council of Churches of which he was a leader, but also to all individuals and groups in South Africa who, with their concern for human dignity, fraternity and democracy, incite the admiration of the world.”

Two years later he become the Archbishop of Cape Town, the first Black man to preside over the city’s two million-strong congregation. Right-wing white Christians protested outside the cathedral at his investiture, calling it the “death of the Anglican church.” As the church’s official residence was located in an area reserved for white residents only, the apartheid government asked him to apply for the status of “honorary white” so that he could reside on the premises. He refused.

Tutu’s receipt of the Nobel Peace Prize helped catapult South Africa’s anti-apartheid movement into a global cause. Nearly a decade’s worth of eloquent advocacy by Tutu and his supporters around the world brought the country’s government to its knees. In 1993 the apartheid system ended, South African blacks were given the vote, and in 1994 they elected Nelson Mandela as their first Black president. Tutu had the honor of introducing the new president to the nation. He has described that moment as one of the greatest in his life. “I said to God, ‘God, if I die now, I don’t really mind.’”

But Mandela had other plans for “The Arch,” as he was affectionately called, appointing him as head of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission tasked with investigating human rights abuses committed by both sides during apartheid. Tutu presided over the two and a half-year-long proceeding with his trademark grace, compassion and forgiveness, even though he sometimes collapsed into anguished tears upon hearing details of some of the worst atrocities.

READ MORE: 10 Questions for Desmond Tutu

Often called the “moral conscience of South Africa,” Tutu was also known to be a bit of a scold. He held all of the nation’s leaders to the highest standards, and made enemies of many in the African National Congress for his well-deserved criticisms of their failings. He derided Mandela’s successor, President Thabo Mbeki, for his denial of the country’s HIV/AIDS epidemic, and took on President Jacob Zuma for his “moral failings.” Even the leaders of neighboring countries were not spared: Zimbabwe’s former president, Robert Mugabe , once described Tutu as “an evil little bishop” for Tutu’s sermons against the Zimbabwean dictator’s kleptocratic rule.

In 2007 Tutu turned his exacting gaze against the Anglican Church, rebuking religious conservatives among the clergy for their attitudes against homosexuality. He told the BBC that the Church had failed to demonstrate that God is “welcoming,” and that he had felt saddened and “ashamed.” “If God, as they say, is homophobic, I wouldn’t worship that God,” he said. Later on he told supporters in Cape Town that he “would refuse to go to a homophobic heaven…. I mean I would much rather go to the other place.”

As a founding member of the Elders , an organization of former world leaders who work together to promote human rights and world peace, Tutu continued on his quest to put an end to injustice until he decided to retire from public life in 2010. “Instead of growing old gracefully, at home with my family, reading and writing and praying and thinking, too much of my time has been spent at airports and in hotels,” he said at the time. “The time has now come to slow down, to sip rooibos tea with my beloved wife in the afternoons, to watch cricket, to travel to visit my children and grandchildren, rather than to conferences and conventions and university campuses.”

Nonetheless, he emerged from his seclusion from time to time when he found it absolutely necessary. In 2017, he penned a chagrined letter to fellow Nobel Laureate Aung San Suu Kyi, calling on her to speak up for the rights of Rohingya in Myanmar , saying that said the “unfolding horror” and “ethnic cleansing” of the country’s Muslim minority had forced him to speak out. “I am now elderly, decrepit and formally retired, but breaking my vow to remain silent on public affairs out of profound sadness,” he wrote in a letter he posted on social media. “If the political price of your ascension to the highest office in Myanmar is your silence, the price is surely too steep.”

Tutu leaves behind his wife, Nomalizo Leah Tutu, four children, several grandchildren and a nation bereft of one of the most articulate voices for justice the world has ever seen.

In a 2014 speech advocating for the right to assisted death, the archbishop described the peaceful death and joyous funeral he hoped to have for himself. He said that he would like to be cremated, despite knowing that it made some people uncomfortable, and that he would like to have his ashes interred at St. George’s Cathedral in Cape Town. He wanted a simple coffin, he said, one that would serve as an example to others of the importance of frugal funerals: “My concern is not just about affordability; it’s my strong preference that money should be spent on the living.”

Most of all, he concluded, he wanted his death to be seen not as an occasion for sadness, but as the natural conclusion to the arc of his extraordinary life. “Dying is part of life,” he said. “We have to die. The Earth cannot sustain us and the millions of people that came before us. We have to make way for those who are yet to be born.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Javier Milei’s Radical Plan to Transform Argentina

- The New Face of Doctor Who

- How Private Donors Shape Birth-Control Choices

- What Happens if Trump Is Convicted ? Your Questions, Answered

- The Deadly Digital Frontiers at the Border

- Scientists Are Finding Out Just How Toxic Your Stuff Is

- The 31 Most Anticipated Movies of Summer 2024

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

World leaders mourn the death of Archbishop Desmond Tutu

Deepa Shivaram