Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Write for Us

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 19, Issue 1

- Reviewing the literature

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Joanna Smith 1 ,

- Helen Noble 2

- 1 School of Healthcare, University of Leeds , Leeds , UK

- 2 School of Nursing and Midwifery, Queens's University Belfast , Belfast , UK

- Correspondence to Dr Joanna Smith , School of Healthcare, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, UK; j.e.smith1{at}leeds.ac.uk

https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2015-102252

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Implementing evidence into practice requires nurses to identify, critically appraise and synthesise research. This may require a comprehensive literature review: this article aims to outline the approaches and stages required and provides a working example of a published review.

Are there different approaches to undertaking a literature review?

What stages are required to undertake a literature review.

The rationale for the review should be established; consider why the review is important and relevant to patient care/safety or service delivery. For example, Noble et al 's 4 review sought to understand and make recommendations for practice and research in relation to dialysis refusal and withdrawal in patients with end-stage renal disease, an area of care previously poorly described. If appropriate, highlight relevant policies and theoretical perspectives that might guide the review. Once the key issues related to the topic, including the challenges encountered in clinical practice, have been identified formulate a clear question, and/or develop an aim and specific objectives. The type of review undertaken is influenced by the purpose of the review and resources available. However, the stages or methods used to undertake a review are similar across approaches and include:

Formulating clear inclusion and exclusion criteria, for example, patient groups, ages, conditions/treatments, sources of evidence/research designs;

Justifying data bases and years searched, and whether strategies including hand searching of journals, conference proceedings and research not indexed in data bases (grey literature) will be undertaken;

Developing search terms, the PICU (P: patient, problem or population; I: intervention; C: comparison; O: outcome) framework is a useful guide when developing search terms;

Developing search skills (eg, understanding Boolean Operators, in particular the use of AND/OR) and knowledge of how data bases index topics (eg, MeSH headings). Working with a librarian experienced in undertaking health searches is invaluable when developing a search.

Once studies are selected, the quality of the research/evidence requires evaluation. Using a quality appraisal tool, such as the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tools, 5 results in a structured approach to assessing the rigour of studies being reviewed. 3 Approaches to data synthesis for quantitative studies may include a meta-analysis (statistical analysis of data from multiple studies of similar designs that have addressed the same question), or findings can be reported descriptively. 6 Methods applicable for synthesising qualitative studies include meta-ethnography (themes and concepts from different studies are explored and brought together using approaches similar to qualitative data analysis methods), narrative summary, thematic analysis and content analysis. 7 Table 1 outlines the stages undertaken for a published review that summarised research about parents’ experiences of living with a child with a long-term condition. 8

- View inline

An example of rapid evidence assessment review

In summary, the type of literature review depends on the review purpose. For the novice reviewer undertaking a review can be a daunting and complex process; by following the stages outlined and being systematic a robust review is achievable. The importance of literature reviews should not be underestimated—they help summarise and make sense of an increasingly vast body of research promoting best evidence-based practice.

- ↵ Centre for Reviews and Dissemination . Guidance for undertaking reviews in health care . 3rd edn . York : CRD, York University , 2009 .

- ↵ Canadian Best Practices Portal. http://cbpp-pcpe.phac-aspc.gc.ca/interventions/selected-systematic-review-sites / ( accessed 7.8.2015 ).

- Bridges J , et al

- ↵ Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). http://www.casp-uk.net / ( accessed 7.8.2015 ).

- Dixon-Woods M ,

- Shaw R , et al

- Agarwal S ,

- Jones D , et al

- Cheater F ,

Twitter Follow Joanna Smith at @josmith175

Competing interests None declared.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

The Power of Mass Media and Feminism in the Evolution of Nursing’s Image: A Critical Review of the Literature and Implications for Nursing Practice

- Published: 12 November 2019

- Volume 42 , pages 371–386, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Jasmine Gill ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7534-1091 1 &

- Charley Baker 1

7505 Accesses

18 Citations

6 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Nursing has evolved, yet media representation has arguably failed to keep up. This work explores why representation has been slow in accurately depicting nurses' responsibilities, impacts on public perceptions and professional identity. A critical realist review was employed as this method enables in-depth exploration into why something exists. A multidisciplinary approach was adopted, drawing from feminist, psychological and sociological theories to provide insightful understanding and recommendations. One main feminist lens has been implemented, using Laura Mulvey’s ‘Male-Gaze’ framework for content analysis of three nurse-related advertisements to explore how the profession's female status influences representation, public perception and how this might impact nursing. Nurse representation has important real-world consequences. It is essential to improve unnecessary negative portrayals and contest ingrained stereotypes as there are costs to public opinion and nursing's self-identity. Nursing's female status has an impact within a male-dominated media industry, with a leisurely approach adopted toward changing representation. Media images become societally ingrained, this reiterates the significance of accurate/positive depictions. Social media is an instant method of communication with the public to combat stereotypes and maintain engagement to provide better understanding of what nurses do.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

The Role of Communication in Stereotypes, Prejudices and Professional Identity: The Case of Nurses

Professionalism in a Pandemic: Shifting Perceptions of Nursing Through Social Media

Religious orientation, endorser credibility, and the portrayal of female nurses by the media.

Chyong-Ling Lin, Jin-Tsann Yeh, … Wei-Chung Lee

24 Hours in A&E . 2011. Channel 4. 11 May. London: The Garden Productions Ltd.

Archer, Margaret. 1995. Realist Social Theory: The Morphogenetic Approach . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Bandura, Albert. 2001. “Social Cognitive Theory of Mass Communication.” Media Psychology 3 (3): 265-299.

Article Google Scholar

BBC News – British Broadcasting Corporation. 2015. “#ImInWorkJeremy: NHS Staff Post Weekend Working Photos.” Accessed 1 September 2017. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-33578990 .

Bhaskar, Roy. 1998. The Possibility of Naturalism . 3rd edition. London: Routledge.

Google Scholar

_____. 2008. A Realist Theory of Science . London: Verso.

Bright, Jim. 1997. “Carry On Remembering.” Classic Television 1: 25-33.

Broadcasters’ Audience Research Board. 2017. Viewing Data . Accessed 4 June 2017. http://www.barb.co.uk/viewing-data/ .

Brodie, David A., Gavin J. Andrews, Justin P. Andrews, Gail B. Thomas, Josephine Wong, and Lorna Rixon. 2004. “Perceptions of Nursing: Confirmation, Change and the Student Experience.” International Journal of Nursing Studies 41 (7): 721-733.

Bronner, Gila, Chava Peretz and Mally Ehrenfeld. 2003. “Sexual Harassment of Nurses and Nursing Students.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 42 (6): 637-644.

Bryman, A. 2016. Social Research Methods . 5th edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Byerly, Carolyn M. 2013. “Women and the Concentration of Media Ownership.” In Seeking Equity for Women in Journalism and Mass Communication Education , edited by Ramona R. Rush, Carol E. Oukrop and Pamela J. Creedon, 245. Mahwah: Taylor and Francis.

Cabaniss, Reitha. 2011. “Educating Nurses to Impact Change in Nursing's Image.” Teaching and Learning in Nursing 6 (3): 112-118.

Carroll, Stacey M. and Katherine C. Rosa. 2016. “Role and Image of Nursing in Children's Literature: A Qualitative Media Analysis.” Journal of Pediatric Nursing 31 (2): 141-151.

Carry On Doctor . 1967. Directed by Gerald Thomas. United Kingdom. Rank Organisation.

Carry On Matron . 1972. Directed by Gerald Thomas. United Kingdom. The Rank Organisation.

Carry On Nurse . 1959. Directed by Gerald Thomas. United Kingdom. Anglo-Amalgamated.

Carter, Cynthia., Linda Steiner, and Lisa McLaughlin. 2014. The Routledge Companion to Media and Gender. London: Routledge.

Ceulemans, Mieke and Guido Fauconnier. 1979. “Mass Media: The Image, Role and Social Conditions of Women: A Collection and Analysis of Research Materials.” Reports and Papers on Mass Communication 84:26-27.

Cohen, Shelley and Kathleen Bartholomew. 2009. The Image of Nursing: Perspectives on Shaping, Empowering, and Elevating the Nursing Profession . Danvers: HCPro.

Connell, Barbara. 2011. Exploring the Media: Text, Industry, Audience. New York: Columbia University Press.

Crenshaw, Kimberle. 1989. “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.” University of Chicago Legal Forum 140: 139–167.

Darbyshire, Philip. 2014. “Heroines, Hookers and Harridans: Exploring Popular Images and Representations of Nurses and Nursing.” In Contexts of Nursing: An Introduction , edited by J. Daly, S. Speedy, D. Jackson, 51-64. Sydney: Elsevier.

Dean, Erin. 2014. “Lancet Commission to Tackle the Poor Perception of UK Nursing.” Nursing Standard 28 (21): 10.

Deep Throat . 1972. Directed by Jerry Gerald. Florida, United States. Bryanston Pictures.

Doyle, Gillian. 2002. Media Ownership: The Economics and Politics of Convergence and Concentration in the UK and European Media. London: SAGE Publications.

Dyer, Richard. 2013. The Matter of Images: Essays on Representation . 2 nd edition. London: Routledge.

Edgley, Alison, Theodore Stickley, Stephen Timmons, and Andy Meal. 2014. “Critical Realist Review: Exploring the Real, Beyond the Empirical.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 40 (3): 316–330.

Ehrenreich, Barbara and Deirdre English. 2010. Witches, Midwives, and Nurses: A History of Women Healers . 2 nd edition. New York: The Feminist Press.

Fagin, Claire M. 2000. Essays on Nursing Leadership . New York: Springer.

Finlayson, Belinda, Jennifer Dixon, Sandra Meadows, and George Blair. 2002. “Mind the Gap: The Extent of the NHS Nursing Shortage.” BMJ 325 (7363): 538-541.

Ford, Steve. 2017a . “Trust Backtracks on Job Ad Dubbed ‘Disrespectful’ to Nurses.” Nursing Times . Accessed 22 July 2017. https://www.nursingtimes.net/news/hospital/trust-backtracks-on-job-ad-dubbed-disrespectful-to-nurses/7017390.article .

_____. 2017b. “'Sexist’ Nurse Job Ads Were Used by Mistake, Says Trust . ” Nursing Times . Accessed 25 July 2017. https://www.nursingtimes.net/news/hospital/sexist-nurse-job-ads-were-used-by-mistake-says-trust/7018256.article .

Fraenkel, Jack R. and Wallen, Norman E. 2006. How to Design and Evaluate Research in Education. 6th edition. Boston: McGraw-Hill Education (ISE Editions).

Gill, R. 2007. Gender and the Media . Cambridge: Polity Press.

Gillett, Karen. 2014. “Nostalgic Constructions of Nurse Education in British National Newspapers.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 70 (11): 2495-2505.

Girvin, June. 2015. “Editorial: The Public Understanding of Nursing - Time for A Step Change?” Journal of Clinical Nursing 24 (23-24): 3341-3342.

_____. 2017. “#50shadesofHey (acknowledgement of the # to P Darbyshire.” Still Learning About Leadership. Accessed 4 June 2017. https://junegirvin2.wordpress.com/2017/05/17/50shadesofhey-acknowledgment-of-the-to-p-darbyshire/ .

Girvin, June, D. Jackson, and M. Hutchinson, M. 2016. “Contemporary Public Perceptions of Nursing: A Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis of The International Research Evidence.” Journal of Nursing Management 24: 994–1006.

Grant, Maria J. and Andrew Booth. 2009. “A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies.” Health Information & Libraries Journal 26 (2): 91–108.

Hall, Stuart. 1973. Encoding and Decoding in the Television Discourse . Birmingham: University of Birmingham Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies.

Hallam, Julia. 2000. Nursing the Image: Media, Culture and Professional Identity . London: Routledge.

Happer, Catherina and Greg Philo. 2013. “The Role of the Media in the Construction of Public Belief and Social Change.” Journal of Social and Political Psychology 1 (1): 321-336.

Hart, Andrew. 2013. Teaching the Media: International Perspectives . London: Routledge.

Heilemann, Mary-Sue V. 2012. “Media Images and Screen Representations of Nurses.” Nursing Outlook 60 (5): 1-3.

Hsieh, Hsiu-Fang and Sarah E. Shannon. 2005. “Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis.” Qualitative Health Research 15 (9): 1277-1288.

Hudson-Jones, Anne. 1988. Images of Nurses: Perspectives from History, Art and Literature . Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Huston, Carol J. 2014. Professional Issues in Nursing . Third edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Jones-Berry, S. 2017. “Nursing Now! Campaign To Support and Empower Nurses.” Nursing Standard , 31 (51): 7-8.

Joseph, Ammu. 2013. “Media Pluralism and Gender: Not Just a Question of Numbers.” Waccglobal . Accessed 3 September 2017. http://www.waccglobal.org/articles/media-pluralism-and-gender-not-just-a-question-of-numbers .

Kalisch, Philip A. and Beatrice J. Kalisch. 1987. The Changing Image of the Nurse . California: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

Knapton, Sarah. 2015. “#ImInWorkJeremy: NHS Staff Post Weekend Working Pictures on Twitter.” Telegraph. Accessed 1 September 2017. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/health/news/11749289/ImInWorkJeremy-NHS-staff-post-weekend-working-pictures-on-Twitter.html .

Lippmann, Walter. 1956. Public Opinion . New York: Macmillan.

Long, Paul and Tim Wall. 2014. Media Studies: Texts, Production, Context . 2nd edition. London: Routledge.

Madison, Jean and Victor Minichiello. 2000. “Recognizing and Labelling Sex Based and Sexual Harassment in the Health Care Workplace.” Journal of Nursing Scholarships 4 (32): 405–410.

Matos, Carolina. 2017. Globalization, Gender Politics and the Media . London: Lexington Books.

McAllister, Margaret, Terri Downer, Julie Hanson, and Florin Oprescu. 2014. “Transformers: Changing the Face of Nursing and Midwifery in the Media.” Nurse Education in Practice 14 (2): 148-153.

McNab, Christine. 2009. “What Social Media Offers to Health Professionals and Citizens.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 87 (8): 566.

Media Reform Coalition. 2015. “Who Owns the UK Media?” Accessed 3 September 2017. http://www.mediareform.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Who_owns_the_UK_media-report_plus_appendix1.pdf .

Monaghan, Thomas. 2015. “A Critical Analysis of the Literature and Theoretical Perspectives on Theory–Practice Gap amongst Newly Qualified Nurses Within the United Kingdom.” Nurse Education Today 35 (8): 1-7.

Muehlbauer, Paula M. 2012. “How Can We Improve the Way the Media Portrays the Nursing Profession?” ONS Voice . Accessed 1 September 2017. https://voice.ons.org/news-and-views/how-can-we-improve-the-way-the-media-portrays-the-nursing-profession .

Muff, Janet. 1988. Socialization, Sexism, and Stereotyping: Women's Issues in Nursing. Prospect Heights, Ill.: Waveland Press.

Mulvey, Laura. 1975. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Screen 16 (3): 6-18.

_____. 1989. “Afterthoughts on ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ inspired by King Vidor’s Duel in the Sun (1946).” In Visual and Other Pleasures , edited by Stephen Heath, Colin MacCabe, and Denise Riley, 29-38. Language, Discourse, Society. Palgrave Macmillan, London.

_____. 2013. Fetishism and Curiosity . Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Munn, Flavia. 2016. “Nursing the Most Trusted Profession in the UK.” Nursing Standard . Accessed 21 May 2017. https://rcni.com/nursing-standard/newsroom/news/nursing-most-trusted-profession-uk-72621 .

NMC – Nursing & Midwifery Council. 2015. “Guidance on Using Social Media Responsibly.” Accessed 1 September 2017. https://www.nmc.org.uk/globalassets/sitedocuments/nmc-publications/social-media-guidance.pdf .

NMC – Nursing & Midwifery Council. 2016. “Annual Equality and Diversity Report . ” Accessed 11 August 2017. https://www.nmc.org.uk/globalassets/sitedocuments/annual_reports_and_accounts/equality-and-diversity-report-2015-16.pdf .

Norman, Jim. 2016. “Americans Rate Healthcare Providers High on Honesty, Ethics.” Gallup . Accessed 20 May 2017. http://www.gallup.com/poll/200057/americans-rate-healthcare-providers-high-honesty-ethics.aspx .

Ott, Brian L. and Robert L. Mack. 2014. Critical Media Studies: An Introduction . 2nd edition. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons.

Pawson, Ray. 2006. Evidence-Based Policy: A Realist Perspective . London: Sage.

Pawson, Ray and Nicholas Tilley. 1997. Realistic Evaluation . London: Sage.

Peate, Ian. 2015. “The Lancet—Commission or Condescension?” British Journal of Nursing 24 (8): 429.

Press Association, The. 2014. “Media Coverage ‘Idealises Nursing from the Past.”’ Nursing Times. Accessed 26 Jun 2017. https://www.nursingtimes.net/media-coverage-idealises-nursing-from-the-past/5071086.article .

Ross, Karen and Claudia Padovani. 2017. Gender Equality and the Media . Basingstoke: Taylor & Francis Limited.

RCN – Royal College of Nursing. 2015. “This is Nursing in the South West.” Accessed 27 May 2017. https://www.rcn.org.uk/-/media/royal-college-of-nursing/documents/publications/2015/july/pub-004873.pdf .

RCN – Royal College of Nursing. 2017. “Campaigns.” Accessed 27 May 2017. https://www2.rcn.org.uk/newsevents/campaigns .

Sayer, Andrew. 2000. Realism and Social Science . London: Sage.

Seago, Jean Anne, Joanne Spetz, Andrew Alvarado, Dennis Kean, et al. 2006. “The Nursing Shortage: Is It Really About Image?” Journal of Healthcare Management 51 (2): 96-110.

Sephel, Alysse. 2011. “Digging Deeper: Nurse Excess or Shortage?” Journal of Professional Nursing 27 (6): 390-393.

Shelton, Anthony. 1995. Fetishism: Visualising Power and Desire . London: Lund Humphries.

Silva, Michelle and Julie Freischlag. 2017. “Challenge Accepted: Social Media as a Stereotype Change Agent.” The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery 154 (4): 1354-1355.

Simpkin, Victoria L. and Elias Mossialos. 2017. “Brexit and the NHS: Challenges, Uncertainties and Opportunities.” Health Policy 121 (5): 477-480.

Skeggs, Beverley. 1997. Formations of Class and Gender: Becoming Respectable . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Soothill, Keith, Christine Henry, and Kevin Kendrick. 1992. Themes and Perspectives in Nursing . London: Chapman & Hall.

Spector, Paul E., Zhiqing E. Zhou, and Xin Xuan Chen. 2014. “Nurse Exposure to Physical and Nonphysical Violence, Bullying, and Sexual Harassment: A Quantitative review.” International Journal of Nursing Studies 51 (1): 72-84.

Stange, Mary Zeiss, Carol Oyster, and Jane Sloan. 2013. The Multimedia Encyclopedia of Women in Today's World. London: SAGE Publications Inc.

Summers, Sandy. 2010. “The Image of Nursing: The Naughty Nurse.” Nursing Times . Accessed 26 April 2017. https://www.nursingtimes.net/roles/nurse-educators/the-image-of-nursing-the-naughty-nurse/5020678.article .

Summers, Sandy and Harry Jacobs Summers. 2015. Saving Lives: Why the Media’s Portrayal of Nursing Puts Us All at Risk. 2 nd edition. New York: Oxford University Press.

Takase, Miyuki, Esme Kershaw, and Lorraine Burt. 2002. “Does Public Image of Nurses Matter?” Journal of Professional Nursing 18 (4): 196-205.

Takase, Miyuki., Philip Maude, and Elizabeth Manias. 2006. “Impact of the Perceived Public Image of Nursing on Nurses' Work Behaviour.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 53 (3): 333-343.

The Prime Minister’s Commission on the Future of Nursing and Midwifery in England. 2010. “Front Line Care: The Future of Nursing and Midwifery in England.” Accessed 27 May 2017. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20100331110400/http:/cnm.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/front_line_care.pdf .

The Times . 2017. “Storm over ‘Sexist’ Poster Campaign to Recruit Nurses.” Accessed 20 July 2017. https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/storm-over-sexist-poster-campaign-to-recruit-nurses-d7w5zd6b2 .

Thio, Alex and Jim Taylor. 2012. Social Problems . Sudbury: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Thompson, Victoria. 2010. “Ad Campaign Attacked as 'Gratuitous Sexualisation of Nursing.” Nursing Times . Accessed 17 July 2017. https://www.nursingtimes.net/roles/nurse-managers/ad-campaign-attacked-as-gratuitous-sexualisation-of-nursing/5012644.article .

Thornham, Sue. 2007. Women, Feminism and media. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Thorpe, Charles. 2016. Necroculture . New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Tuchman, Gaye. 1979. “Women's Depiction by the Mass Media.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 4 (3): 528-542.

Ulmer, Brenda. 2000. “The Image of Nursing.” AORN Journal 71 (6): 1124-1127.

Ramsay, G. 2019. “Who Owns the UK Media?” Accessed 12 May 2019. https://www.mediareform.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/FINALonline2.pdf .

Walter, D. 2013. “Nurse Past, Present and Future: The Making of Modern Nursing.” AORN Journal 97 (3): 383-384.

Willis, Phil. 2012. “Quality with Compassion: The Future of Nursing Education: Report of the Willis Commission 2012.” Accessed 27 May 2017. http://www.williscommission.org.uk/__data/.../Willis_Commission_executive_summary.pdf .

Yar, Mohammed, David Dix, and Madhavi Bajekal. 2006. “Socio-demographic Characteristics of the Healthcare Workforce in England and Wales--Results from the 2001 Census.” Health Stat Q 32:44-56.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Royal Derby Hospital, Room 401, Uttoxeter Road, Derby, DE22 3DT, UK

Jasmine Gill & Charley Baker

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jasmine Gill .

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

1 Blink 182. 1999. Enema of the State Album Cover. [photograph]. https://www.truthaboutnursing.org/media/music/blink182.html . Accessed 28 July 2017.

2 Ford, Steve. 2012a. RCN Launches Ad Campaign to Promote ‘Remarkable’ Nurses. [photograph]. https://www.nursingtimes.net/roles/nurse-managers/rcn-launches-ad-campaign-to-promote-remarkable-nurses-17-09-2012/ . Accessed: 28 July 2017.

3 Ford, Steve. 2012b. RCN Launches Ad Campaign to Promote ‘Remarkable’ Nurses. [photograph]. https://www.nursingtimes.net/roles/nurse-managers/rcn-launches-ad-campaign-to-promote-remarkable-nurses-17-09-2012/ . Accessed: 28 July 2017.

4 Thompson, Victoria. 2010. Ad Campaign Attacked as ‘Gratuitous Sexualisation of Nurses’. [photograph]. https://www.nursingtimes.net/roles/nurse-managers/ad-campaign-attacked-as-gratuitous-sexualisation-of-nursing-16-03-2010/ . Accessed: 27 July 2017.

5 Wigan Hospitals. 2017. Looking to work for a great employer…look no further? [photograph]. https://twitter.com/WWLNHS/status/834447744743960576 . Accessed 27 July 2017.

6 The Times. 2017. Storm Over ‘Sexist’ Poster Campaign to Recruit Nurses. [photograph]. https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/storm-over-sexist-poster-campaign-to-recruit-nurses-d7w5zd6b2 . Accessed: 27 July 2017.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Gill, J., Baker, C. The Power of Mass Media and Feminism in the Evolution of Nursing’s Image: A Critical Review of the Literature and Implications for Nursing Practice. J Med Humanit 42 , 371–386 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10912-019-09578-6

Download citation

Published : 12 November 2019

Issue Date : September 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10912-019-09578-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Representation

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Open access

- Published: 19 March 2024

Interventions, methods and outcome measures used in teaching evidence-based practice to healthcare students: an overview of systematic reviews

- Lea D. Nielsen 1 ,

- Mette M. Løwe 2 ,

- Francisco Mansilla 3 ,

- Rene B. Jørgensen 4 ,

- Asviny Ramachandran 5 ,

- Bodil B. Noe 6 &

- Heidi K. Egebæk 7

BMC Medical Education volume 24 , Article number: 306 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

150 Accesses

Metrics details

To fully implement the internationally acknowledged requirements for teaching in evidence-based practice, and support the student’s development of core competencies in evidence-based practice, educators at professional bachelor degree programs in healthcare need a systematic overview of evidence-based teaching and learning interventions. The purpose of this overview of systematic reviews was to summarize and synthesize the current evidence from systematic reviews on educational interventions being used by educators to teach evidence-based practice to professional bachelor-degree healthcare students and to identify the evidence-based practice-related learning outcomes used.

An overview of systematic reviews. Four databases (PubMed/Medline, CINAHL, ERIC and the Cochrane library) were searched from May 2013 to January 25th, 2024. Additional sources were checked for unpublished or ongoing systematic reviews. Eligibility criteria included systematic reviews of studies among undergraduate nursing, physiotherapist, occupational therapist, midwife, nutrition and health, and biomedical laboratory science students, evaluating educational interventions aimed at teaching evidence-based practice in classroom or clinical practice setting, or a combination. Two authors independently performed initial eligibility screening of title/abstracts. Four authors independently performed full-text screening and assessed the quality of selected systematic reviews using standardized instruments. Data was extracted and synthesized using a narrative approach.

A total of 524 references were retrieved, and 6 systematic reviews (with a total of 39 primary studies) were included. Overlap between the systematic reviews was minimal. All the systematic reviews were of low methodological quality. Synthesis and analysis revealed a variety of teaching modalities and approaches. The outcomes were to some extent assessed in accordance with the Sicily group`s categories; “skills”, “attitude” and “knowledge”. Whereas “behaviors”, “reaction to educational experience”, “self-efficacy” and “benefits for the patient” were rarely used.

Conclusions

Teaching evidence-based practice is widely used in undergraduate healthcare students and a variety of interventions are used and recognized. Not all categories of outcomes suggested by the Sicily group are used to evaluate outcomes of evidence-based practice teaching. There is a need for studies measuring the effect on outcomes in all the Sicily group categories, to enhance sustainability and transition of evidence-based practice competencies to the context of healthcare practice.

Peer Review reports

Evidence-based practice (EBP) enhances the quality of healthcare, reduces the cost, improves patient outcomes, empowers clinicians, and is recognized as a problem-solving approach [ 1 ] that integrates the best available evidence with clinical expertise and patient preferences and values [ 2 ]. A recent scoping review of EBP and patient outcomes indicates that EBPs improve patient outcomes and yield a positive return of investment for hospitals and healthcare systems. The top outcomes measured were length of stay, mortality, patient compliance/adherence, readmissions, pneumonia and other infections, falls, morbidity, patient satisfaction, patient anxiety/ depression, patient complications and pain. The authors conclude that healthcare professionals have a professional and ethical responsibility to provide expert care which requires an evidence-based approach. Furthermore, educators must become competent in EBP methodology [ 3 ].

According to the Sicily statement group, teaching and practicing EBP requires a 5-step approach: 1) pose an answerable clinical question (Ask), 2) search and retrieve relevant evidence (Search), 3) critically appraise the evidence for validity and clinical importance (Appraise), 4) applicate the results in practice by integrating the evidence with clinical expertise, patient preferences and values to make a clinical decision (Integrate), and 5) evaluate the change or outcome (Evaluate /Assess) [ 4 , 5 ]. Thus, according to the World Health Organization, educators, e.g., within undergraduate healthcare education, play a vital role by “integrating evidence-based teaching and learning processes, and helping learners interpret and apply evidence in their clinical learning experiences” [ 6 ].

A scoping review by Larsen et al. of 81 studies on interventions for teaching EBP within Professional bachelor-degree healthcare programs (PBHP) (in English undergraduate/ bachelor) shows that the majority of EBP teaching interventions include the first four steps, but the fifth step “evaluate/assess” is less often applied [ 5 ]. PBHP include bachelor-degree programs characterized by combined theoretical education and clinical training within nursing, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, radiography, and biomedical laboratory students., Furthermore, an overview of systematic reviews focusing on practicing healthcare professionals EBP competencies testifies that although graduates may have moderate to high level of self-reported EBP knowledge, skills, attitudes, and beliefs, this does not translate into their subsequent EBP implementation [ 7 ]. Although this cannot be seen as direct evidence of inadequate EBP teaching during undergraduate education, it is irrefutable that insufficient EBP competencies among clinicians across healthcare disciplines impedes their efforts to attain highest care quality and improved patient outcomes in clinical practice after graduation.

Research shows that teaching about EBP includes different types of modalities. An overview of systematic reviews, published by Young et al. in 2014 [ 8 ] and updated by Bala et al. in 2021 [ 9 ], synthesizes the effects of EBP teaching interventions including under- and post graduate health care professionals, the majority being medical students. They find that multifaceted interventions with a combination of lectures, computer lab sessions, small group discussion, journal clubs, use of current clinical issues, portfolios and assignments lead to improvement in students’ EBP knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behaviors compared to single interventions or no interventions [ 8 , 9 ]. Larsen et al. find that within PBHP, collaboration with clinical practice is the second most frequently used intervention for teaching EBP and most often involves four or all five steps of the EBP teaching approach [ 5 ]. The use of clinically integrated teaching in EBP is only sparsely identified in the overviews by Young et al. and Bala et al. [ 8 , 9 ]. Therefore, the evidence obtained within Bachelor of Medicine which is a theoretical education [ 10 ], may not be directly transferable for use in PBHP which combines theoretical and mandatory clinical education [ 11 ].

Since the overview by Young et al. [ 8 ], several reviews of interventions for teaching EBP used within PBHP have been published [ 5 , 12 , 13 , 14 ].

We therefore wanted to explore the newest evidence for teaching EBP focusing on PBHP as these programs are characterized by a large proportion of clinical teaching. These healthcare professions are certified through a PBHP at a level corresponding to a University Bachelor Degree, but with strong focus on professional practice by combining theoretical studies with mandatory clinical teaching. In Denmark, almost half of PBHP take place in clinical practice. These applied science programs qualify “the students to independently analyze, evaluate and reflect on problems in order to carry out practice-based, complex, and development-oriented job functions" [ 11 ]. Thus, both the purpose of these PBHP and the amount of clinical practice included in the educations contrast with for example medicine.

Thus, this overview, identifies the newest evidence for teaching EBP specifically within PBHP and by including reviews using quantitative and/or qualitative methods.

We believe that such an overview is important knowledge for educators to be able to take the EBP teaching for healthcare professions to a higher level. Also reviewing and describing EBP-related learning outcomes, categorizing them according to the seven assessment categories developed by the Sicily group [ 2 ], will be useful knowledge to educators in healthcare professions. These seven assessment categories for EBP learning including: Reaction to the educational experience, attitudes, self-efficacy, knowledge, skills, behaviors and benefits to patients, can be linked to the five-step EBP approach. E.g., reactions to the educational experience: did the educators teaching style enhance learners’ enthusiasm for asking questions? (Ask), self-efficacy: how well do learners think they critically appraise evidence? (Appraise), skills: can learners come to a reasonable interpretation of how to apply the evidence? (Integrate) [ 2 ]. Thus, this set of categories can be seen as a basic set of EBP-related learning outcomes to classify the impact from EBP educational interventions.

Purpose and review questions

A systematic overview of which evidence-based teaching interventions and which EBP-related learning outcomes that are used will give teachers access to important knowledge on what to implement and how to evaluate EBP teaching.

Thus, the purpose of this overview is to synthesize the latest evidence from systematic reviews about EBP teaching interventions in PBHP. This overview adds to the existing evidence by focusing on systematic reviews that a) include qualitative and/ or quantitative studies regardless of design, b) are conducted among PBHP within nursing, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, midwifery, nutrition and health and biomedical laboratory science, and c) incorporate the Sicily group's 5-step approach and seven assessment categories when analyzing the EBP teaching interventions and EBP-related learning outcomes.

The questions of this overview of systematic reviews are:

Which educational interventions are described and used by educators to teach EBP to Professional Bachelor-degree healthcare students?

What EBP-related learning outcomes have been used to evaluate teaching interventions?

The study protocol was guided by the Cochrane Handbook on Overviews of Reviews [ 15 ] and the review process was reported in accordance with The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement [ 16 ] when this was consistent with the Cochrane Handbook.

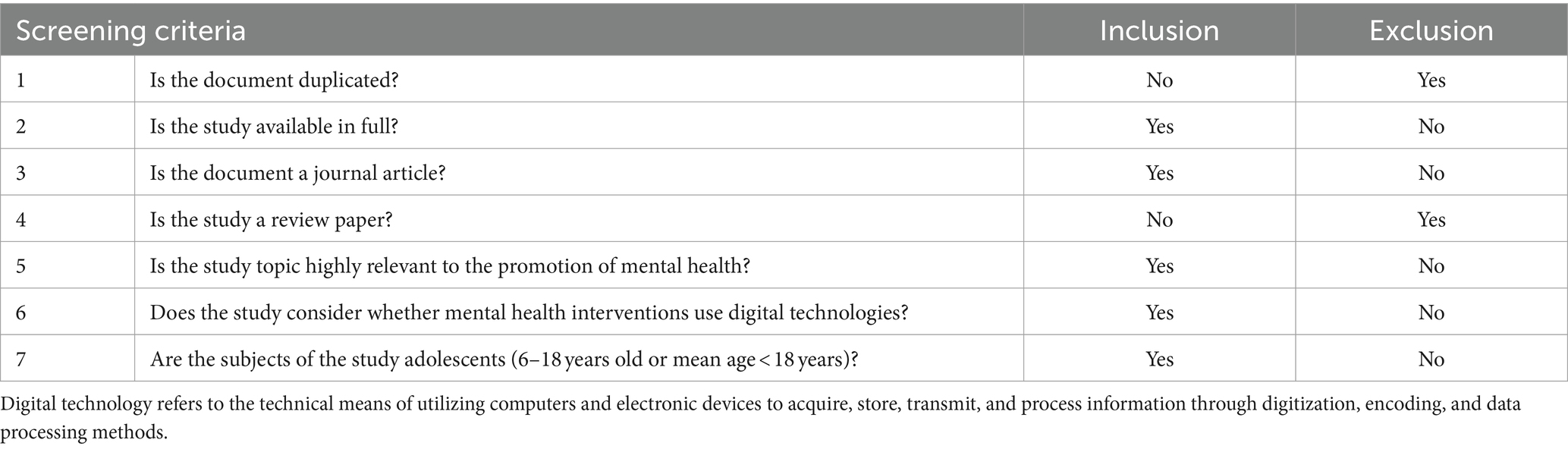

Inclusion criteria

Eligible reviews fulfilled the inclusion criteria for publication type, population, intervention, and context (see Table 1 ). Failing a single inclusion criterion implied exclusion.

Search strategy

On January 25th 2024 a systematic search was conducted in; PubMed/Medline, CINAHL (EBSCOhost), ERIC (EBSCOhost) and the Cochrane library from May 2013 to January 25th, 2024 to identify systematic reviews published after the overview by Young et al. [ 8 ]. In collaboration with a research librarian, a search strategy of controlled vocabulary and free text terms related to systematic reviews, the student population, teaching interventions, teaching context, and evidence-based practice was developed (see Additional file 1 ). For each database, the search strategy was peer reviewed, revised, modified and subsequently pilot tested. No language restrictions were imposed.

To identify further eligible reviews, the following methods were used: Setting email alerts from the databases to provide weekly updates on new publications; backward and forward citation searching based on the included reviews by screening of reference lists and using the “cited by” and “similar results” function in PubMed and CINAHL; broad searching in Google Scholar (Advanced search), Prospero, JBI Evidence Synthesis and the OPEN Grey database; contacting experts in the field via email to first authors of included reviews, and by making queries via Twitter and Research Gate on any information on unpublished or ongoing reviews of relevance.

Selection and quality appraisal process

Database search results were merged, duplicate records were removed, and title/abstract were initially screened via Covidence [ 17 ]. The assessment process was pilot tested by four authors independently assessing eligibility and methodological quality of one potential review followed by joint discussion to reach a common understanding of the criteria used. Two authors independently screened each title/abstract for compliance with the predefined eligibility criteria. Disagreements were resolved by a third author. Four authors were paired for full text screening, and each pair assessed independently 50% of the potentially relevant reviews for eligibility and methodological quality.

For quality appraisal, two independent authors used the AMSTAR-2 (A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews) for reviews including intervention studies [ 18 ] and the Joanna Briggs Institute Checklist for systematic reviews and research Synthesis (JBI checklist) [ 19 ] for reviews including both quantitative and qualitative or only qualitative studies. Uncertainties in assessments were resolved by requesting clarifying information from first authors of reviews and/or discussion with co-author to the present overview.

Overall methodological quality for included reviews was assessed using the overall confidence criteria of AMSTAR 2 based on scorings in seven critical domains [ 18 ] appraised as high (none or one non-critical flaw), moderate (more than one non-critical flaw), low (one critical weakness) or critically low (more than one critical weakness) [ 18 ]. For systematic reviews of qualitative studies [ 13 , 20 , 21 ] the critical domains of the AMSTAR 2, not specified in the JBI checklist, were added.

Data extraction and synthesis process

Data were initially extracted by the first author, confirmed or rejected by the last author and finally discussed with the whole author group until consensus was reached.

Data extraction included 1) Information about the search and selection process according to the PRISMA statement [ 16 , 22 ], 2) Characteristics of the systematic reviews inspired by a standard in the Cochrane Handbook (15), 3) A citation index inspired by Young et al. [ 8 ] used to illustrate overlap of primary studies in the included systematic reviews, and to ensure that data from each primary study were extracted only once [ 15 ], 4) Data on EBP teaching interventions and EBP-related outcomes. These data were extracted, reformatted (categorized inductively into two categories: “Collaboration interventions” and “ Educational interventions ”) and presented as narrative summaries [ 15 ]. Data on outcome were categorized according to the seven assessment categories, defined by the Sicily group, to classify the impact from EBP educational interventions: Reaction to the educational experience, attitudes, self-efficacy, knowledge, skills, behaviors and benefits to patients [ 2 ]. When information under points 3 and 4 was missing, data from the abstracts of the primary study articles were reviewed.

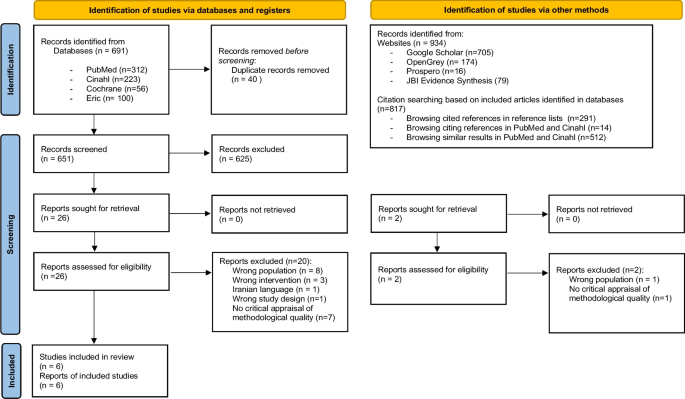

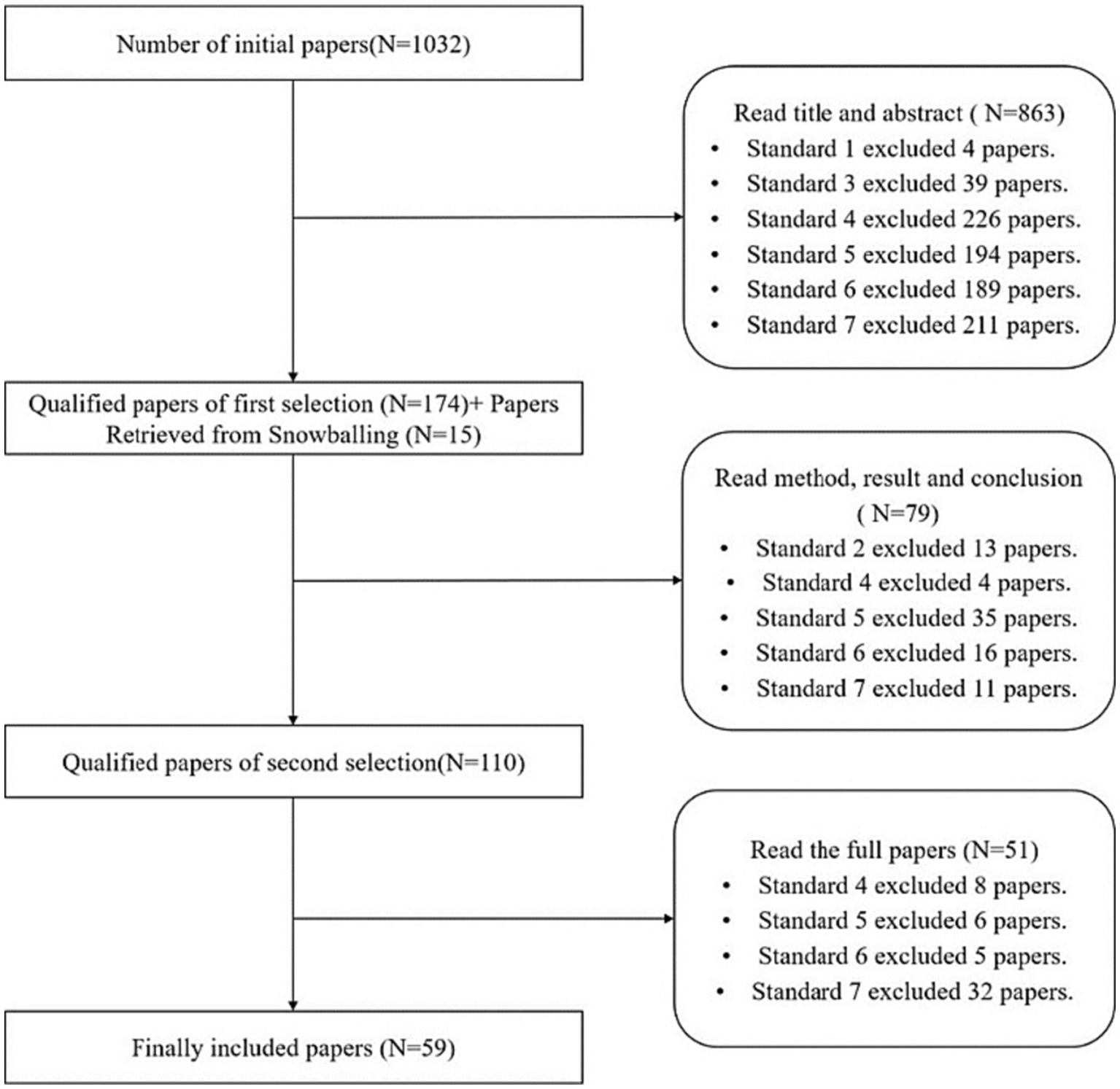

Results of the search

The database search yielded 691 references after duplicates were removed. Title and abstract screening deemed 525 references irrelevant. Searching via other methods yielded two additional references. Out of 28 study reports assessed for eligibility 22 were excluded, leaving a total of six systematic reviews. Screening resulted in 100% agreement among the authors. Figure 1 details the search and selection process. Reviews that might seem relevant but did not meet the eligibility criteria [ 15 ], are listed in Additional file 2 . One protocol for a potentially relevant review was identified as ongoing [ 23 ].

PRISMA flow diagram on search and selection of systematic reviews

Characteristics of included systematic reviews and overlap between them

The six systematic reviews originated from the Middle East, Asia, North America, Europe, Scandinavia, and Australia. Two out of six reviews did not identify themselves as systematic reviews but did fulfill this eligibility criteria [ 12 , 20 ]. All six represented a total of 64 primary studies and a total population of 6649 students (see Table 2 ). However, five of the six systematic reviews contained a total of 17 primary studies not eligible to our overview focus (e.g., postgraduate students) (see Additional file 3 ). Results from these primary studies were not extracted. Of the remaining primary studies, six were included in two, and one was included in three systematic reviews. Data from these studies were extracted only once to avoid double-counting. Thus, the six systematic reviews represented a total of 39 primary studies and a total population of 3394 students. Nursing students represented 3280 of these. One sample of 58 nutrition and health students and one sample of 56 mixed nursing and midwife students were included but none from physiotherapy, occupational therapy, or biomedical laboratory scientists. The majority ( n = 28) of the 39 primary studies had a quantitative design whereof 18 were quasi-experimental (see Additional file 4 ).

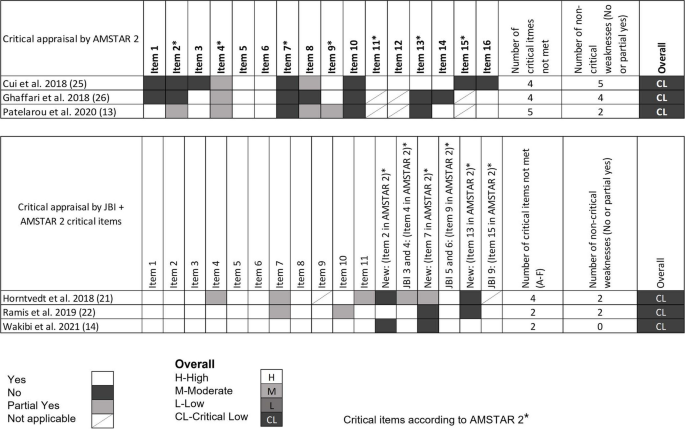

Quality of systematic review

All the included systematic reviews were assessed as having critically low quality with 100% concordance between the two designed authors (see Fig. 2 ) [ 18 ]. The main reasons for the low quality of the reviews were a) not demonstrating a registered protocol prior to the review [ 13 , 20 , 24 , 25 ], b) not providing a list of excluded studies with justification for exclusion [ 12 , 13 , 21 , 24 , 25 ] and c) not accounting for the quality of the individual studies when interpreting the result of the review [ 12 , 20 , 21 , 25 ].

Overall methodological quality assessment for systematic reviews. Quantitative studies [ 12 , 24 , 25 ] were assessed following the AMSTAR 2 critical domain guidelines. Qualitative studies [ 13 , 20 , 21 ] were assessed following the JBI checklist. For overall classification, qualitative studies were also assessed with the following critical AMSTAR 2 domains not specified in the JBI checklist (item 2. is the protocol registered before commencement of the review, item 7. justification for excluding individual studies and item 13. consideration of risk of bias when interpreting the results of the review)

Missing reporting of sources of funding for primary studies and not describing the included studies in adequate detail were, most often, the two non-critical items of the AMSTAR 2 and the JBI checklist, not met.

Most of the included reviews did report research questions including components of PICO, performed study selection and data extraction in duplicate, used appropriate methods for combining studies and used satisfactory techniques for assessing risk of bias (see Fig. 2 ).

Main findings from the systematic reviews

As illustrated in Table 2 , this overview synthesizes evidence on a variety of approaches to promote EBP teaching in both classroom and clinical settings. The systematic reviews describe various interventions used for teaching in EBP, which can be summarized into two themes: Collaboration Interventions and Educational Interventions.

Collaboration interventions to teach EBP

In general, the reviews point that interdisciplinary collaboration among health professionals and/or others e.g., librarian and professionals within information technologies is relevant when planning and teaching in EBP [ 13 , 20 ].

Interdisciplinary collaboration was described as relevant when planning teaching in EBP [ 13 , 20 ]. Specifically, regarding literature search Wakibi et al. found that collaboration between librarians, computer laboratory technicians and nurse educators enhanced students’ skills [ 13 ]. Also, in terms of creating transfer between EBP teaching and clinical practice, collaboration between faculty, library, clinical institutions, and teaching institutions was used [ 13 , 20 ].

Regarding collaboration with clinical practice, Ghaffari et al. found that teaching EBP integrated in clinical education could promote students’ knowledge and skills [ 25 ]. Horntvedt et al. found that during a six-week course in clinical practice, students obtained better skills in reading research articles and orally presenting the findings to staff and fellow students [ 20 ]. Participation in clinical research projects combined with instructions in analyzing and discussing research findings also “led to a positive approach and EBP knowledge” [ 20 ]. Moreover, reading research articles during the clinical practice period enhances the students critical thinking skills. Furthermore, Horntvedt et al. mention, that students found it meaningful to conduct a “mini” – research project in clinical settings, as the identified evidence became relevant [ 20 ].

Educational interventions

Educational interventions can be described as “Framing Interventions” understood as different ways to set up a framework for teaching EBP, and “ Teaching methods ” understood as specific methods used when teaching EBP.

Various educational interventions were described in most reviews [ 12 , 13 , 20 , 21 ]. According to Patelarou et al., no specific educational intervention regardless of framing and methods was in favor to “ increase knowledge, skills and competency as well as improve the beliefs, attitudes and behaviors of nursing students” [ 12 ].

Framing interventions

The approaches used to set up a framework for teaching EBP were labelled in different ways: programs, interactive teaching strategies, educational programs, courses etc. Approaches of various durations from hours to months were described as well as stepwise interventions [ 12 , 13 , 20 , 21 , 24 , 25 ].

Some frameworks [ 13 , 20 , 21 , 24 ] were based on the assessments categories described by the Sicily group [ 2 ] or based on theory [ 21 ] or as mentioned above clinically integrated [ 20 ]. Wakibi et al. identified interventions used to foster a spirit of inquiry and EBP culture reflecting the “5-step approach” of the Sicily group [ 4 ], asking PICOT questions, searching for best evidence, critical appraisal, integrating evidence with clinical expertise and patient preferences to make clinical decisions, evaluating outcomes of EBP practice, and disseminating outcomes useful [ 13 ]. Ramis et al. found that teaching interventions based on theory like Banduras self-efficacy or Roger’s theory of diffusion led to positive effects on students EBP knowledge and attitudes [ 21 ].

Teaching methods

A variety of teaching methods were used such as, lectures [ 12 , 13 , 20 ], problem-based learning [ 12 , 20 , 25 ], group work, discussions [ 12 , 13 ], and presentations [ 20 ] (see Table 2 ). The most effective method to achieve the skills required to practice EBP as described in the “5-step approach” by the Sicely group is a combination of different teaching methods like lectures, assignments, discussions, group works, and exams/tests.

Four systematic reviews identified such combinations or multifaceted approaches [ 12 , 13 , 20 , 21 ]. Patelarou et al. states that “EBP education approaches should be blended” [ 12 ]. Thus, combining the use of video, voice-over, PowerPoint, problem-based learning, lectures, team-based learning, projects, and small groups were found in different studies. This combination had shown “to be effective” [ 12 ]. Similarly, Horntvedt et al. found that nursing students reported that various teaching methods improved their EBP knowledge and skills [ 20 ].

According to Ghaffari et al., including problem-based learning in teaching plans “improved the clinical care and performance of the students”, while the problem-solving approach “promoted student knowledge” [ 25 ]. Other teaching methods identified, e.g., flipped classroom [ 20 ] and virtual simulation [ 12 , 20 ] were also characterized as useful interactive teaching interventions. Furthermore, face-to-face approaches seem “more effective” than online teaching interventions to enhance students’ research and appraisal skills and journal clubs enhance the students critically appraisal-skills [ 12 ].

As the reviews included in this overview primarily are based on qualitative, mixed methods as well as quasi-experimental studies and to a minor extent on randomized controlled trials (see Table 2 ) it is not possible to conclude of the most effective methods. However, a combination of methods and an innovative collaboration between librarians, information technology professionals and healthcare professionals seem the most effective approach to achieve EBP required skills.

EBP-related outcomes

Most of the systematic reviews presented a wide array of outcome assessments applied in EBP research (See Table 3 ). Analyzing the outcomes according to the Sicily group’s assessment categories revealed that assessing “knowledge” (used in 19 out of 39 primary studies), “skills” (used in 18 out of 39 primary studies) and “attitude” (used in 17 out of 39) were by far the most frequently used assessment categories, whereas outcomes within the category of “behaviors” (used in eight studies) “reaction to educational experience” (in five studies), “self-efficacy” (in two studies), and “benefits for the patient” (in one study), were used to a far lesser extent. Additionally, outcomes, that we were not able to categorize within the seven assessment categories, were “future use” and “Global EBP competence”.

The purpose of this overview of systematic reviews was to collect and summarize evidence of the diversity of EBP teaching interventions and outcomes measured among professional bachelor- degree healthcare students.

Our results give an overview of “the state of the art” of using and measuring EBP in PBHP education. However, the quality of included systematic reviews was rated critically low. Thus, the result cannot support guidelines of best practice.

The analysis of the interventions and outcomes described in the 39 primary studies included in this overview, reveals a wide variety of teaching methods and interventions being used and described in the scientific literature on EBP teaching of PBHP students. The results show some evidence of the five step EBP approach in accordance with the inclusion criteria “interventions aimed at teaching one or more of the five EBP steps; Ask, Search, Appraise, Integrate, Assess/evaluate”. Most authors state, that the students´ EBP skills, attitudes and knowledge improved by almost any of the described methods and interventions. However, descriptions of how the improvements were measured were less frequent.

We evaluated the described outcome measures and assessments according to the seven categories proposed by the Sicily group and found that most assessments were on “attitudes”, “skills” and “knowledge”, sometimes on “behaviors” and very seldom on” reaction to educational experience”, “self-efficacy” and “benefits to the patients”. To our knowledge no systematic review or overview has made this evaluation on outcome categories before, but Bala et al. [ 9 ] also stated that knowledge, skills, and attitudes are the most common evaluated effects.

Comparing the outcomes measured between mainly medical [ 9 ] and nursing students, the most prevalent outcomes in both groups are knowledge, skills and attitudes around EBP. In contrast, measuring on the students´ patient care or on the impact of the EBP teaching on benefits for the patients is less prevalent. In contrast Wu et al.’s systematic review shows that among clinical nurses, educational interventions supporting implementation of EBP projects can change patient outcomes positively. However, they also conclude that direct causal evidence of the educational interventions is difficult to measure because of the diversity of EBP projects implemented [ 26 ]. Regarding EBP behavior the Sicily group recommend this category to be assessed by monitoring the frequency of the five step EBP approach, e.g., ASK questions about patients, APPRAISE evidence related to patient care, EVALUATE their EBP behavior and identified areas for improvement [ 2 ]. The results also showed evidence of student-clinician transition. “Future use” was identified in two systematic reviews [ 12 , 13 ] and categorized as “others”. This outcome is not included in the seven Sicily categories. However, a systematic review of predictive modelling studies shows, that future use or the intention to use EBP after graduation are influenced by the students EBP familiarity, EBP capability beliefs, EBP attitudes and academic and clinical support [ 27 ].

Teaching and evaluating EBP needs to move beyond aiming at changes in knowledge, skills, and attitudes, but also start focusing on changing and assessing behavior, self-efficacy and benefit to the patients. We recommend doing this using validated tools for the assessment of outcomes and in prospective studies with longer follow-up periods, preferably evaluating the adoption of EBP in clinical settings bearing in mind, that best teaching practice happens across sectors and settings supported and supervised by multiple professions.

Based on a systematic review and international Delphi survey, a set of interprofessional EBP core competencies that details the competence content of each of the five steps has been published to inform curriculum development and benchmark EBP standards [ 28 ]. This consensus statement may be used by educators as a reference for both learning objectives and EBP content descriptions in future intervention research. The collaboration with clinical institutions and integration of EBP teaching components such as EBP assignments or participating in clinical research projects are important results. Specifically, in the light of the dialectic between theoretical and clinical education as a core characteristic of Professional bachelor-degree healthcare educations.

Our study has some limitations that need consideration when interpreting the results. A search in the EMBASE and Scopus databases was not added in the search strategy, although it might have been able to bring additional sources. Most of the 22 excluded reviews included primary studies among other levels/ healthcare groups of students or had not critically appraised their primary studies. This constitutes insufficient adherence to methodological guidelines for systematic reviews and limits the completeness of the reviews identified. Often, the result sections of the included reviews were poorly reported and made it necessary to extract some, but not always sufficient, information from the primary study abstracts. As the present study is an overview and not a new systematic review, we did not extract information from the result section in the primary studies. Thus, the comprehensiveness and applicability of the results of this overview are limited by the methodological limitations in the six included systematic reviews.

The existing evidence is based on different types of study designs. This heterogeneity is seen in all the included reviews. Thus, the present overview only conveys trends around the comparative effectiveness of the different ways to frame, or the methods used for teaching EBP. This can be seen as a weakness for the clarity and applicability of the overview results. Also, our protocol is unpublished, which may weaken the transparency of the overview approach, however our search strategies are available as additional material (see Additional file 1 ). In addition, the validity of data extraction can be discussed. We extracted data consecutively by the first and last author and if needed consensus was reached by discussion with the entire research group. This method might have been strengthened by using two blinded reviewers to extract data and present data with supporting kappa values.

The generalizability of the results of this overview is limited to undergraduate nursing students. Although, we consider it a strength that the results represent a broad international perspective on framing EBP teaching, as well as teaching methods and outcomes used among educators in EBP. Primary studies exist among occupational therapy and physiotherapy students [ 5 , 29 ] but have not been systematically synthesized. However, the evidence is almost non-existent among midwife, nutrition and health and biomedical laboratory science students. This has implications for further research efforts because evidence from within these student populations is paramount for future proofing the quality assurance of clinical evidence-based healthcare practice.

Another implication is the need to compare how to frame the EBP teaching, and the methods used both inter-and mono professionally among these professional bachelor-degree students. Lastly, we support the recommendations of Bala et al. of using validated tools to increase the focus on measuring behavior change in clinical practice and patient outcomes, and to report in accordance with the GREET guidelines for educational intervention studies [ 9 ].

This overview demonstrates a variety of approaches to promote EBP teaching among professional bachelor-degree healthcare students. Teaching EBP is based on collaboration with clinical practice and the use of different approaches to frame the teaching as well as different teaching methods. Furthermore, this overview has elucidated, that interventions often are evaluated according to changes in the student’s skills, knowledge and attitudes towards EBP, but very rarely on self-efficacy, behaviors, benefits to the patients or reaction to the educational experience as suggested by the Sicily group. This might indicate that educators need to move on to measure the effect of EBP on outcomes comprising all categories, which are important to enhance sustainable behavior and transition of knowledge into the context of practices where better healthcare education should have an impact. In our perspective these gaps in the EBP teaching are best met by focusing on more collaboration with clinical practice which is the context where the final endpoint of teaching EBP should be anchored and evaluated.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used an/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Evidence-Based Practice

Professional bachelor-degree healthcare programs

Mazurek Melnyk B, Fineout-Overholt E. Making the Case for Evidence-Based Practice and Cultivalting a Spirit of Inquiry. I: Mazurek Melnyk B, Fineout-Overholt E, redaktører. Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing and Healthcare A Guide to Best Practice. 4. ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2019. p. 7–32.

Tilson JK, Kaplan SL, Harris JL, Hutchinson A, Ilic D, Niederman R, et al. Sicily statement on classification and development of evidence-based practice learning assessment tools. BMC Med Educ. 2011;11(78):1–10.

Google Scholar

Connor L, Dean J, McNett M, Tydings DM, Shrout A, Gorsuch PF, et al. Evidence-based practice improves patient outcomes and healthcare system return on investment: Findings from a scoping review. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2023;20(1):6–15.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Dawes M, Summerskill W, Glasziou P, Cartabellotta N, Martin J, Hopayian K, et al. Sicily statement on evidence-based practice. BMC Med Educ. 2005;5(1):1–7.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Larsen CM, Terkelsen AS, Carlsen AF, Kristensen HK. Methods for teaching evidence-based practice: a scoping review. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):1–33.

Article CAS Google Scholar

World Health Organization. Nurse educator core competencies. 2016 https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/258713 Accessed 21 Mar 2023.

Saunders H, Gallagher-Ford L, Kvist T, Vehviläinen-Julkunen K. Practicing healthcare professionals’ evidence-based practice competencies: an overview of systematic reviews. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2019;16(3):176–85.

Young T, Rohwer A, Volmink J, Clarke M. What Are the Effects of Teaching Evidence-Based Health Care (EBHC)? Overview of Systematic Reviews PLoS ONE. 2014;9(1):1–13.

Bala MM, Poklepović Peričić T, Zajac J, Rohwer A, Klugarova J, Välimäki M, et al. What are the effects of teaching Evidence-Based Health Care (EBHC) at different levels of health professions education? An updated overview of systematic reviews. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(7):1–28.

Article Google Scholar

Copenhagen University. Bachelor in medicine. 2024 https://studier.ku.dk/bachelor/medicin/undervisning-og-opbygning/ Accessed 31 Jan 2024.

Ministery of Higher Education and Science. Professional bachelor programmes. 2022 https://ufm.dk/en/education/higher-education/university-colleges/university-college-educations Accessed 31 Jan 2024.

Patelarou AE, Mechili EA, Ruzafa-Martinez M, Dolezel J, Gotlib J, Skela-Savič B, et al. Educational Interventions for Teaching Evidence-Based Practice to Undergraduate Nursing Students: A Scoping Review. Int J Env Res Public Health. 2020;17(17):1–24.

Wakibi S, Ferguson L, Berry L, Leidl D, Belton S. Teaching evidence-based nursing practice: a systematic review and convergent qualitative synthesis. J Prof Nurs. 2021;37(1):135–48.

Fiset VJ, Graham ID, Davies BL. Evidence-Based Practice in Clinical Nursing Education: A Scoping Review. J Nurs Educ. 2017;56(9):534–41.

Pollock M, Fernandes R, Becker L, Pieper D, Hartling L. Chapter V: Overviews of Reviews. I: Higgins J, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page M, et al., editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 62. 2021 https://training.cochrane.org/handbook Accessed 31 Jan 2024.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, m.fl. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:1-9

Covidence. Covidence - Better systematic review management. https://www.covidence.org/ Accessed 31 Jan 2024.

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;21(358):1–9.

Joanna Briggs Institute. Critical Appraisal Tools. https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools Accessed 31 Jan 2024.

Horntvedt MT, Nordsteien A, Fermann T, Severinsson E. Strategies for teaching evidence-based practice in nursing education: a thematic literature review. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):1–11.

Ramis M-A, Chang A, Conway A, Lim D, Munday J, Nissen L. Theory-based strategies for teaching evidence-based practice to undergraduate health students: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):1–13.

Rethlefsen ML, Kirtley S, Waffenschmidt S, Ayala AP, Moher D, Page MJ, et al. PRISMA-S: an extension to the PRISMA Statement for Reporting Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):1–19.

Song CE, Jang A. Simulation design for improvement of undergraduate nursing students’ experience of evidence-based practice: a scoping-review protocol. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(11):1–6.

Cui C, Li Y, Geng D, Zhang H, Jin C. The effectiveness of evidence-based nursing on development of nursing students’ critical thinking: A meta-analysis. Nurse Educ Today. 2018;65:46–53.

Ghaffari R, Shapoori S, Binazir MB, Heidari F, Behshid M. Effectiveness of teaching evidence-based nursing to undergraduate nursing students in Iran: a systematic review. Res Dev Med Educ. 2018;7(1):8–13.

Wu Y, Brettle A, Zhou C, Ou J, Wang Y, Wang S. Do educational interventions aimed at nurses to support the implementation of evidence-based practice improve patient outcomes? A systematic review. Nurse Educ Today. 2018;70:109–14.

Ramis MA, Chang A, Nissen L. Undergraduate health students’ intention to use evidence-based practice after graduation: a systematic review of predictive modeling studies. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2018;15(2):140–8.

Albarqouni L, Hoffmann T, Straus S, Olsen NR, Young T, Ilic D, et al. Core competencies in evidence-based practice for health professionals: consensus statement based on a systematic review and Delphi survey. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(2):1–12.

Hitch D, Nicola-Richmond K. Instructional practices for evidence-based practice with pre-registration allied health students: a review of recent research and developments. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pr. 2017;22(4):1031–45.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge research librarian Rasmus Sand for competent support in the development of literature search strategies.

This work was supported by the University College of South Denmark, which was not involved in the conduct of this study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Nursing Education & Department for Applied Health Science, University College South Denmark, Degnevej 17, 6705, Esbjerg Ø, Denmark

Lea D. Nielsen

Department of Oncology, Hospital of Lillebaelt, Beriderbakken 4, 7100, Vejle, Denmark

Mette M. Løwe

Biomedical Laboratory Science & Department for Applied Health Science, University College South Denmark, Degnevej 17, 6705, Esbjerg Ø, Denmark

Francisco Mansilla

Physiotherapy Education & Department for Applied Health Science, University College South Denmark, Degnevej 17, 6705, Esbjerg Ø, Denmark

Rene B. Jørgensen

Occupational Therapy Education & Department for Applied Health Science, University College South Denmark, Degnevej 17, 6705, Esbjerg Ø, Denmark

Asviny Ramachandran

Department for Applied Health Science, University College South Denmark, Degnevej 17, 6705, Esbjerg Ø, Denmark

Bodil B. Noe

Centre for Clinical Research and Prevention, Section for Health Promotion and Prevention, Bispebjerg and Frederiksberg Hospital, Nordre Fasanvej 57, 2000, Frederiksberg, Denmark

Heidi K. Egebæk

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation of data, writing the main manuscript, preparing figures and tables and revising the manuscripts.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Lea D. Nielsen .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary material 1., supplementary material 2., supplementary material 3., supplementary material 4., rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Nielsen, L.D., Løwe, M.M., Mansilla, F. et al. Interventions, methods and outcome measures used in teaching evidence-based practice to healthcare students: an overview of systematic reviews. BMC Med Educ 24 , 306 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-05259-8

Download citation

Received : 29 May 2023

Accepted : 04 March 2024

Published : 19 March 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-05259-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- MH "Students, Health occupations+"

- MH "Students, occupational therapy"

- MH "Students, physical therapy"

- MH "Students, Midwifery"

- “Students, Nursing"[Mesh]

- “Teaching"[Mesh]

- MH "Teaching methods+"

- "Evidence-based practice"[Mesh]

BMC Medical Education

ISSN: 1472-6920

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Open access

- Published: 18 March 2024

Exploring advanced clinical practitioner perspectives on training, role identity and competence: a qualitative study

- Maxine Kuczawski ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0774-8113 1 ,

- Suzanne Ablard 1 ,

- Fiona Sampson 1 ,

- Susan Croft 1 , 2 ,

- Joanna Sutton-Klein 1 , 3 &

- Suzanne Mason 1

BMC Nursing volume 23 , Article number: 185 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

260 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Advanced Clinical Practitioners (ACPs) are a new role that have been established to address gaps and support the existing medical workforce in an effort to help reduce increasing pressures on NHS services. ACPs have the potential to practice at a similar level to mid-grade medical staff, for example independently undertaking assessments, requesting and interpreting investigations, and diagnosing and discharging patients. These roles have been shown to improve both service outcomes and quality of patient care. However, there is currently no widespread formalised standard of training within the UK resulting in variations in the training experiences and clinical capabilities of ACPs. We sought to explore the training experiences of ACPs as well as their views on role identity and future development of the role.

Five online focus groups were conducted between March and May 2021 with trainee and qualified advanced clinical practitioners working in a range of healthcare settings, in the North of England. The focus groups aimed to explore the experiences of undertaking ACP training including supervision, gaining competence, role identity and career progression. Thematic analysis of the focus group transcripts was performed, informed by grounded theory principles.

Fourteen advanced clinical practitioners participated. Analysis revealed that training was influenced by internal and external perceptions of the role, often acting as barriers, with structural aspects being significant contributory factors. Key themes identified (1) clinical training lacked structure and support, negatively impacting progress, (2) existing knowledge and experience acted as both an enabler and inhibitor, with implications for confidence, (3) the role and responsibilities are poorly understood by both advanced clinical practitioners and the wider medical profession and (4) advanced clinical practitioners recognised the value and importance of the role but felt changes were necessary, to provide security and sustainability.

Conclusions

Appropriate structure and support are crucial throughout the training process to enable staff to have a smooth transition to advanced level, ensuring they obtain the necessary confidence and competence. Structural changes and knowledge brokering are essential, particularly in relation to role clarity and its responsibilities, sufficient allocated time to learn and practice, role accreditation and continuous appropriate supervision.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Advanced Clinical Practitioners (ACPs) are a relatively new role in the National Health Service (NHS), introduced to address the increasing complexity of healthcare needs and the growing demand for skilled professionals. They are becoming increasingly embedded within a wide range of NHS healthcare settings spanning community services, mental health wards and hospitals. ACPs play a vital role in expanding the scope of practice within healthcare teams, take on more advanced and complex levels of clinical work, including tasks historically carried out by doctors, with an aim to help alleviate the strain on medical professionals and enhance the efficiency of healthcare delivery. Their integration into the workforce has been shown to enhance patient care by providing timely access to high-quality services while also fostering interdisciplinary collaboration [ 1 ]. Studies have shown that ACPs contribute to improved patient outcomes, increased patient satisfaction, and cost-effective healthcare delivery [ 2 , 3 ]. Additionally, their presence supports the development of junior staff by providing mentorship and guidance, thus ensuring a sustainable healthcare workforce for the future [ 1 , 4 ]. As non-medical healthcare professionals, ACPS are required to undertake further education (Masters degree) and extended training in specific clinical areas such as nursing, pharmacy, or allied health professions to qualify as an ACP. According to the multi-professional framework advanced clinical practice, this training is underpinned by four pillars: clinical practice, leadership and management, education, and research [ 5 ]. However, there is wide variability in this practice and training of ACPs across the UK [ 6 ].

Recent years have seen attempts to standardise the training and practice of ACPs. A framework for advanced clinical practice in England was authored in 2017 by Health Education England (HEE) (NHS England) [ 5 ], which set out standards for advanced clinical practice. Within this framework, advanced clinical practitioners should be able to deliver care with a high degree of autonomy and undertake complex decision making. The knowledge and skills should be underpinned by a Master’s level award (or equivalent) that incorporates the Four Pillars of Practice: Clinical Practice, Leadership and Management, Education and Research [ 5 ]. In 2020, The Centre for Advancing Practice ( https://advanced-practice.hee.nhs.uk/ ) began accrediting some of the many advanced clinical practice Masters programmes available in the UK, which it deemed to have met the standards laid out in HEE’s framework [ 7 ]. This process of defining common standards remains in its early stages, and there remains little research on ACP training programmes and their structures or governance. In a further effort to improve and standardise advanced clinical practice, The Centre for Advancing Practice additionally created guidance on workplace supervision for ACPs, noting the crucial need for high-quality supervision [ 8 ]. The Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) published their 2020-25 corporate strategy also in 2020, and committed to explore the need for regulation in a comprehensive review of advanced nurse practice [ 9 ]. The review is still in progress but research undertaken in the early stages by The Nuffield Trust and BritainThinks as part of the review reported inconsistency in definitions, outcomes, standards of education and proficiency in advance practice [ 10 ], and support for regulation by health professionals [ 11 ]. Despite calls for improvements in the supervision of ACPs, there has been limited research in this area.