- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Browse content in C - Mathematical and Quantitative Methods

- Browse content in C0 - General

- C01 - Econometrics

- Browse content in C1 - Econometric and Statistical Methods and Methodology: General

- C10 - General

- C11 - Bayesian Analysis: General

- C12 - Hypothesis Testing: General

- C13 - Estimation: General

- C14 - Semiparametric and Nonparametric Methods: General

- C15 - Statistical Simulation Methods: General

- C18 - Methodological Issues: General

- C19 - Other

- Browse content in C2 - Single Equation Models; Single Variables

- C20 - General

- C21 - Cross-Sectional Models; Spatial Models; Treatment Effect Models; Quantile Regressions

- C22 - Time-Series Models; Dynamic Quantile Regressions; Dynamic Treatment Effect Models; Diffusion Processes

- C23 - Panel Data Models; Spatio-temporal Models

- C24 - Truncated and Censored Models; Switching Regression Models; Threshold Regression Models

- C25 - Discrete Regression and Qualitative Choice Models; Discrete Regressors; Proportions; Probabilities

- C26 - Instrumental Variables (IV) Estimation

- Browse content in C3 - Multiple or Simultaneous Equation Models; Multiple Variables

- C30 - General

- C31 - Cross-Sectional Models; Spatial Models; Treatment Effect Models; Quantile Regressions; Social Interaction Models

- C32 - Time-Series Models; Dynamic Quantile Regressions; Dynamic Treatment Effect Models; Diffusion Processes; State Space Models

- C33 - Panel Data Models; Spatio-temporal Models

- C34 - Truncated and Censored Models; Switching Regression Models

- C35 - Discrete Regression and Qualitative Choice Models; Discrete Regressors; Proportions

- C36 - Instrumental Variables (IV) Estimation

- C38 - Classification Methods; Cluster Analysis; Principal Components; Factor Models

- Browse content in C4 - Econometric and Statistical Methods: Special Topics

- C40 - General

- C41 - Duration Analysis; Optimal Timing Strategies

- C44 - Operations Research; Statistical Decision Theory

- C45 - Neural Networks and Related Topics

- Browse content in C5 - Econometric Modeling

- C50 - General

- C51 - Model Construction and Estimation

- C52 - Model Evaluation, Validation, and Selection

- C53 - Forecasting and Prediction Methods; Simulation Methods

- C54 - Quantitative Policy Modeling

- C55 - Large Data Sets: Modeling and Analysis

- C57 - Econometrics of Games and Auctions

- C58 - Financial Econometrics

- Browse content in C6 - Mathematical Methods; Programming Models; Mathematical and Simulation Modeling

- C60 - General

- C61 - Optimization Techniques; Programming Models; Dynamic Analysis

- C63 - Computational Techniques; Simulation Modeling

- Browse content in C7 - Game Theory and Bargaining Theory

- C78 - Bargaining Theory; Matching Theory

- Browse content in C8 - Data Collection and Data Estimation Methodology; Computer Programs

- C81 - Methodology for Collecting, Estimating, and Organizing Microeconomic Data; Data Access

- Browse content in D - Microeconomics

- Browse content in D0 - General

- D04 - Microeconomic Policy: Formulation; Implementation, and Evaluation

- Browse content in D1 - Household Behavior and Family Economics

- D10 - General

- D12 - Consumer Economics: Empirical Analysis

- Browse content in D2 - Production and Organizations

- D22 - Firm Behavior: Empirical Analysis

- D24 - Production; Cost; Capital; Capital, Total Factor, and Multifactor Productivity; Capacity

- Browse content in D3 - Distribution

- D31 - Personal Income, Wealth, and Their Distributions

- Browse content in D4 - Market Structure, Pricing, and Design

- D41 - Perfect Competition

- D44 - Auctions

- Browse content in D6 - Welfare Economics

- D63 - Equity, Justice, Inequality, and Other Normative Criteria and Measurement

- Browse content in D9 - Micro-Based Behavioral Economics

- D91 - Role and Effects of Psychological, Emotional, Social, and Cognitive Factors on Decision Making

- Browse content in E - Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Browse content in E2 - Consumption, Saving, Production, Investment, Labor Markets, and Informal Economy

- E24 - Employment; Unemployment; Wages; Intergenerational Income Distribution; Aggregate Human Capital; Aggregate Labor Productivity

- Browse content in E3 - Prices, Business Fluctuations, and Cycles

- E30 - General

- E31 - Price Level; Inflation; Deflation

- E32 - Business Fluctuations; Cycles

- E37 - Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in E5 - Monetary Policy, Central Banking, and the Supply of Money and Credit

- E52 - Monetary Policy

- E58 - Central Banks and Their Policies

- Browse content in G - Financial Economics

- Browse content in G1 - General Financial Markets

- G10 - General

- G11 - Portfolio Choice; Investment Decisions

- G12 - Asset Pricing; Trading volume; Bond Interest Rates

- G17 - Financial Forecasting and Simulation

- Browse content in G2 - Financial Institutions and Services

- G21 - Banks; Depository Institutions; Micro Finance Institutions; Mortgages

- Browse content in H - Public Economics

- Browse content in H1 - Structure and Scope of Government

- H12 - Crisis Management

- Browse content in I - Health, Education, and Welfare

- Browse content in I1 - Health

- I12 - Health Behavior

- I13 - Health Insurance, Public and Private

- I14 - Health and Inequality

- I18 - Government Policy; Regulation; Public Health

- I19 - Other

- Browse content in I2 - Education and Research Institutions

- I21 - Analysis of Education

- I24 - Education and Inequality

- Browse content in J - Labor and Demographic Economics

- Browse content in J1 - Demographic Economics

- J16 - Economics of Gender; Non-labor Discrimination

- Browse content in J3 - Wages, Compensation, and Labor Costs

- J31 - Wage Level and Structure; Wage Differentials

- Browse content in J6 - Mobility, Unemployment, Vacancies, and Immigrant Workers

- J64 - Unemployment: Models, Duration, Incidence, and Job Search

- Browse content in J7 - Labor Discrimination

- J71 - Discrimination

- Browse content in L - Industrial Organization

- Browse content in L2 - Firm Objectives, Organization, and Behavior

- L24 - Contracting Out; Joint Ventures; Technology Licensing

- Browse content in O - Economic Development, Innovation, Technological Change, and Growth

- Browse content in O1 - Economic Development

- O10 - General

- O18 - Urban, Rural, Regional, and Transportation Analysis; Housing; Infrastructure

- Browse content in O5 - Economywide Country Studies

- O57 - Comparative Studies of Countries

- Browse content in P - Economic Systems

- Browse content in P1 - Capitalist Systems

- P16 - Political Economy

- Browse content in Q - Agricultural and Natural Resource Economics; Environmental and Ecological Economics

- Browse content in Q0 - General

- Q02 - Commodity Markets

- Browse content in Q1 - Agriculture

- Q11 - Aggregate Supply and Demand Analysis; Prices

- Browse content in Q5 - Environmental Economics

- Q54 - Climate; Natural Disasters; Global Warming

- Browse content in R - Urban, Rural, Regional, Real Estate, and Transportation Economics

- Browse content in R0 - General

- R00 - General

- Browse content in R1 - General Regional Economics

- R15 - Econometric and Input-Output Models; Other Models

- Browse content in R2 - Household Analysis

- R23 - Regional Migration; Regional Labor Markets; Population; Neighborhood Characteristics

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Self-Archiving Policy

- About The Econometrics Journal

- About the Royal Economic Society

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Theoretical Background

- 3. Empirical Methodology

- 5. Empirical Results

- 6. Conclusions

- Acknowledgments

- < Previous

The impact of homework on student achievement

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Ozkan Eren, Daniel J. Henderson, The impact of homework on student achievement, The Econometrics Journal , Volume 11, Issue 2, 1 July 2008, Pages 326–348, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1368-423X.2008.00244.x

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Utilizing parametric and nonparametric techniques, we assess the role of a heretofore relatively unexplored ‘input’ in the educational process, homework, on academic achievement. Our results indicate that homework is an important determinant of student test scores. Relative to more standard spending related measures, extra homework has a larger and more significant impact on test scores. However, the effects are not uniform across different subpopulations. Specifically, we find additional homework to be most effective for high and low achievers, which is further confirmed by stochastic dominance analysis. Moreover, the parametric estimates of the educational production function overstate the impact of schooling related inputs. In all estimates, the homework coefficient from the parametric model maps to the upper deciles of the nonparametric coefficient distribution and as a by‐product the parametric model understates the percentage of students with negative responses to additional homework.

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Librarian

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1368-423X

- Print ISSN 1368-4221

- Copyright © 2024 Royal Economic Society

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Does Homework Really Help Students Learn?

A conversation with a Wheelock researcher, a BU student, and a fourth-grade teacher

“Quality homework is engaging and relevant to kids’ lives,” says Wheelock’s Janine Bempechat. “It gives them autonomy and engages them in the community and with their families. In some subjects, like math, worksheets can be very helpful. It has to do with the value of practicing over and over.” Photo by iStock/Glenn Cook Photography

Do your homework.

If only it were that simple.

Educators have debated the merits of homework since the late 19th century. In recent years, amid concerns of some parents and teachers that children are being stressed out by too much homework, things have only gotten more fraught.

“Homework is complicated,” says developmental psychologist Janine Bempechat, a Wheelock College of Education & Human Development clinical professor. The author of the essay “ The Case for (Quality) Homework—Why It Improves Learning and How Parents Can Help ” in the winter 2019 issue of Education Next , Bempechat has studied how the debate about homework is influencing teacher preparation, parent and student beliefs about learning, and school policies.

She worries especially about socioeconomically disadvantaged students from low-performing schools who, according to research by Bempechat and others, get little or no homework.

BU Today sat down with Bempechat and Erin Bruce (Wheelock’17,’18), a new fourth-grade teacher at a suburban Boston school, and future teacher freshman Emma Ardizzone (Wheelock) to talk about what quality homework looks like, how it can help children learn, and how schools can equip teachers to design it, evaluate it, and facilitate parents’ role in it.

BU Today: Parents and educators who are against homework in elementary school say there is no research definitively linking it to academic performance for kids in the early grades. You’ve said that they’re missing the point.

Bempechat : I think teachers assign homework in elementary school as a way to help kids develop skills they’ll need when they’re older—to begin to instill a sense of responsibility and to learn planning and organizational skills. That’s what I think is the greatest value of homework—in cultivating beliefs about learning and skills associated with academic success. If we greatly reduce or eliminate homework in elementary school, we deprive kids and parents of opportunities to instill these important learning habits and skills.

We do know that beginning in late middle school, and continuing through high school, there is a strong and positive correlation between homework completion and academic success.

That’s what I think is the greatest value of homework—in cultivating beliefs about learning and skills associated with academic success.

You talk about the importance of quality homework. What is that?

Quality homework is engaging and relevant to kids’ lives. It gives them autonomy and engages them in the community and with their families. In some subjects, like math, worksheets can be very helpful. It has to do with the value of practicing over and over.

What are your concerns about homework and low-income children?

The argument that some people make—that homework “punishes the poor” because lower-income parents may not be as well-equipped as affluent parents to help their children with homework—is very troubling to me. There are no parents who don’t care about their children’s learning. Parents don’t actually have to help with homework completion in order for kids to do well. They can help in other ways—by helping children organize a study space, providing snacks, being there as a support, helping children work in groups with siblings or friends.

Isn’t the discussion about getting rid of homework happening mostly in affluent communities?

Yes, and the stories we hear of kids being stressed out from too much homework—four or five hours of homework a night—are real. That’s problematic for physical and mental health and overall well-being. But the research shows that higher-income students get a lot more homework than lower-income kids.

Teachers may not have as high expectations for lower-income children. Schools should bear responsibility for providing supports for kids to be able to get their homework done—after-school clubs, community support, peer group support. It does kids a disservice when our expectations are lower for them.

The conversation around homework is to some extent a social class and social justice issue. If we eliminate homework for all children because affluent children have too much, we’re really doing a disservice to low-income children. They need the challenge, and every student can rise to the challenge with enough supports in place.

What did you learn by studying how education schools are preparing future teachers to handle homework?

My colleague, Margarita Jimenez-Silva, at the University of California, Davis, School of Education, and I interviewed faculty members at education schools, as well as supervising teachers, to find out how students are being prepared. And it seemed that they weren’t. There didn’t seem to be any readings on the research, or conversations on what high-quality homework is and how to design it.

Erin, what kind of training did you get in handling homework?

Bruce : I had phenomenal professors at Wheelock, but homework just didn’t come up. I did lots of student teaching. I’ve been in classrooms where the teachers didn’t assign any homework, and I’ve been in rooms where they assigned hours of homework a night. But I never even considered homework as something that was my decision. I just thought it was something I’d pull out of a book and it’d be done.

I started giving homework on the first night of school this year. My first assignment was to go home and draw a picture of the room where you do your homework. I want to know if it’s at a table and if there are chairs around it and if mom’s cooking dinner while you’re doing homework.

The second night I asked them to talk to a grown-up about how are you going to be able to get your homework done during the week. The kids really enjoyed it. There’s a running joke that I’m teaching life skills.

Friday nights, I read all my kids’ responses to me on their homework from the week and it’s wonderful. They pour their hearts out. It’s like we’re having a conversation on my couch Friday night.

It matters to know that the teacher cares about you and that what you think matters to the teacher. Homework is a vehicle to connect home and school…for parents to know teachers are welcoming to them and their families.

Bempechat : I can’t imagine that most new teachers would have the intuition Erin had in designing homework the way she did.

Ardizzone : Conversations with kids about homework, feeling you’re being listened to—that’s such a big part of wanting to do homework….I grew up in Westchester County. It was a pretty demanding school district. My junior year English teacher—I loved her—she would give us feedback, have meetings with all of us. She’d say, “If you have any questions, if you have anything you want to talk about, you can talk to me, here are my office hours.” It felt like she actually cared.

Bempechat : It matters to know that the teacher cares about you and that what you think matters to the teacher. Homework is a vehicle to connect home and school…for parents to know teachers are welcoming to them and their families.

Ardizzone : But can’t it lead to parents being overbearing and too involved in their children’s lives as students?

Bempechat : There’s good help and there’s bad help. The bad help is what you’re describing—when parents hover inappropriately, when they micromanage, when they see their children confused and struggling and tell them what to do.

Good help is when parents recognize there’s a struggle going on and instead ask informative questions: “Where do you think you went wrong?” They give hints, or pointers, rather than saying, “You missed this,” or “You didn’t read that.”

Bruce : I hope something comes of this. I hope BU or Wheelock can think of some way to make this a more pressing issue. As a first-year teacher, it was not something I even thought about on the first day of school—until a kid raised his hand and said, “Do we have homework?” It would have been wonderful if I’d had a plan from day one.

Explore Related Topics:

- Share this story

Senior Contributing Editor

Sara Rimer A journalist for more than three decades, Sara Rimer worked at the Miami Herald , Washington Post and, for 26 years, the New York Times , where she was the New England bureau chief, and a national reporter covering education, aging, immigration, and other social justice issues. Her stories on the death penalty’s inequities were nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and cited in the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision outlawing the execution of people with intellectual disabilities. Her journalism honors include Columbia University’s Meyer Berger award for in-depth human interest reporting. She holds a BA degree in American Studies from the University of Michigan. Profile

She can be reached at [email protected] .

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.

There are 81 comments on Does Homework Really Help Students Learn?

Insightful! The values about homework in elementary schools are well aligned with my intuition as a parent.

when i finish my work i do my homework and i sometimes forget what to do because i did not get enough sleep

same omg it does not help me it is stressful and if I have it in more than one class I hate it.

Same I think my parent wants to help me but, she doesn’t care if I get bad grades so I just try my best and my grades are great.

I think that last question about Good help from parents is not know to all parents, we do as our parents did or how we best think it can be done, so maybe coaching parents or giving them resources on how to help with homework would be very beneficial for the parent on how to help and for the teacher to have consistency and improve homework results, and of course for the child. I do see how homework helps reaffirm the knowledge obtained in the classroom, I also have the ability to see progress and it is a time I share with my kids

The answer to the headline question is a no-brainer – a more pressing problem is why there is a difference in how students from different cultures succeed. Perfect example is the student population at BU – why is there a majority population of Asian students and only about 3% black students at BU? In fact at some universities there are law suits by Asians to stop discrimination and quotas against admitting Asian students because the real truth is that as a group they are demonstrating better qualifications for admittance, while at the same time there are quotas and reduced requirements for black students to boost their portion of the student population because as a group they do more poorly in meeting admissions standards – and it is not about the Benjamins. The real problem is that in our PC society no one has the gazuntas to explore this issue as it may reveal that all people are not created equal after all. Or is it just environmental cultural differences??????

I get you have a concern about the issue but that is not even what the point of this article is about. If you have an issue please take this to the site we have and only post your opinion about the actual topic

This is not at all what the article is talking about.

This literally has nothing to do with the article brought up. You should really take your opinions somewhere else before you speak about something that doesn’t make sense.

we have the same name

so they have the same name what of it?

lol you tell her

totally agree

What does that have to do with homework, that is not what the article talks about AT ALL.

Yes, I think homework plays an important role in the development of student life. Through homework, students have to face challenges on a daily basis and they try to solve them quickly.I am an intense online tutor at 24x7homeworkhelp and I give homework to my students at that level in which they handle it easily.

More than two-thirds of students said they used alcohol and drugs, primarily marijuana, to cope with stress.

You know what’s funny? I got this assignment to write an argument for homework about homework and this article was really helpful and understandable, and I also agree with this article’s point of view.

I also got the same task as you! I was looking for some good resources and I found this! I really found this article useful and easy to understand, just like you! ^^

i think that homework is the best thing that a child can have on the school because it help them with their thinking and memory.

I am a child myself and i think homework is a terrific pass time because i can’t play video games during the week. It also helps me set goals.

Homework is not harmful ,but it will if there is too much

I feel like, from a minors point of view that we shouldn’t get homework. Not only is the homework stressful, but it takes us away from relaxing and being social. For example, me and my friends was supposed to hang at the mall last week but we had to postpone it since we all had some sort of work to do. Our minds shouldn’t be focused on finishing an assignment that in realty, doesn’t matter. I completely understand that we should have homework. I have to write a paper on the unimportance of homework so thanks.

homework isn’t that bad

Are you a student? if not then i don’t really think you know how much and how severe todays homework really is

i am a student and i do not enjoy homework because i practice my sport 4 out of the five days we have school for 4 hours and that’s not even counting the commute time or the fact i still have to shower and eat dinner when i get home. its draining!

i totally agree with you. these people are such boomers

why just why

they do make a really good point, i think that there should be a limit though. hours and hours of homework can be really stressful, and the extra work isn’t making a difference to our learning, but i do believe homework should be optional and extra credit. that would make it for students to not have the leaning stress of a assignment and if you have a low grade you you can catch up.

Studies show that homework improves student achievement in terms of improved grades, test results, and the likelihood to attend college. Research published in the High School Journal indicates that students who spent between 31 and 90 minutes each day on homework “scored about 40 points higher on the SAT-Mathematics subtest than their peers, who reported spending no time on homework each day, on average.” On both standardized tests and grades, students in classes that were assigned homework outperformed 69% of students who didn’t have homework. A majority of studies on homework’s impact – 64% in one meta-study and 72% in another – showed that take home assignments were effective at improving academic achievement. Research by the Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) concluded that increased homework led to better GPAs and higher probability of college attendance for high school boys. In fact, boys who attended college did more than three hours of additional homework per week in high school.

So how are your measuring student achievement? That’s the real question. The argument that doing homework is simply a tool for teaching responsibility isn’t enough for me. We can teach responsibility in a number of ways. Also the poor argument that parents don’t need to help with homework, and that students can do it on their own, is wishful thinking at best. It completely ignores neurodiverse students. Students in poverty aren’t magically going to find a space to do homework, a friend’s or siblings to help them do it, and snacks to eat. I feel like the author of this piece has never set foot in a classroom of students.

THIS. This article is pathetic coming from a university. So intellectually dishonest, refusing to address the havoc of capitalism and poverty plays on academic success in life. How can they in one sentence use poor kids in an argument and never once address that poor children have access to damn near 0 of the resources affluent kids have? Draw me a picture and let’s talk about feelings lmao what a joke is that gonna put food in their belly so they can have the calories to burn in order to use their brain to study? What about quiet their 7 other siblings that they share a single bedroom with for hours? Is it gonna force the single mom to magically be at home and at work at the same time to cook food while you study and be there to throw an encouraging word?

Also the “parents don’t need to be a parent and be able to guide their kid at all academically they just need to exist in the next room” is wild. Its one thing if a parent straight up is not equipped but to say kids can just figured it out is…. wow coming from an educator What’s next the teacher doesn’t need to teach cause the kid can just follow the packet and figure it out?

Well then get a tutor right? Oh wait you are poor only affluent kids can afford a tutor for their hours of homework a day were they on average have none of the worries a poor child does. Does this address that poor children are more likely to also suffer abuse and mental illness? Like mentioned what about kids that can’t learn or comprehend the forced standardized way? Just let em fail? These children regularly are not in “special education”(some of those are a joke in their own and full of neglect and abuse) programs cause most aren’t even acknowledged as having disabilities or disorders.

But yes all and all those pesky poor kids just aren’t being worked hard enough lol pretty sure poor children’s existence just in childhood is more work, stress, and responsibility alone than an affluent child’s entire life cycle. Love they never once talked about the quality of education in the classroom being so bad between the poor and affluent it can qualify as segregation, just basically blamed poor people for being lazy, good job capitalism for failing us once again!

why the hell?

you should feel bad for saying this, this article can be helpful for people who has to write a essay about it

This is more of a political rant than it is about homework

I know a teacher who has told his students their homework is to find something they are interested in, pursue it and then come share what they learn. The student responses are quite compelling. One girl taught herself German so she could talk to her grandfather. One boy did a research project on Nelson Mandela because the teacher had mentioned him in class. Another boy, a both on the autism spectrum, fixed his family’s computer. The list goes on. This is fourth grade. I think students are highly motivated to learn, when we step aside and encourage them.

The whole point of homework is to give the students a chance to use the material that they have been presented with in class. If they never have the opportunity to use that information, and discover that it is actually useful, it will be in one ear and out the other. As a science teacher, it is critical that the students are challenged to use the material they have been presented with, which gives them the opportunity to actually think about it rather than regurgitate “facts”. Well designed homework forces the student to think conceptually, as opposed to regurgitation, which is never a pretty sight

Wonderful discussion. and yes, homework helps in learning and building skills in students.

not true it just causes kids to stress

Homework can be both beneficial and unuseful, if you will. There are students who are gifted in all subjects in school and ones with disabilities. Why should the students who are gifted get the lucky break, whereas the people who have disabilities suffer? The people who were born with this “gift” go through school with ease whereas people with disabilities struggle with the work given to them. I speak from experience because I am one of those students: the ones with disabilities. Homework doesn’t benefit “us”, it only tears us down and put us in an abyss of confusion and stress and hopelessness because we can’t learn as fast as others. Or we can’t handle the amount of work given whereas the gifted students go through it with ease. It just brings us down and makes us feel lost; because no mater what, it feels like we are destined to fail. It feels like we weren’t “cut out” for success.

homework does help

here is the thing though, if a child is shoved in the face with a whole ton of homework that isn’t really even considered homework it is assignments, it’s not helpful. the teacher should make homework more of a fun learning experience rather than something that is dreaded

This article was wonderful, I am going to ask my teachers about extra, or at all giving homework.

I agree. Especially when you have homework before an exam. Which is distasteful as you’ll need that time to study. It doesn’t make any sense, nor does us doing homework really matters as It’s just facts thrown at us.

Homework is too severe and is just too much for students, schools need to decrease the amount of homework. When teachers assign homework they forget that the students have other classes that give them the same amount of homework each day. Students need to work on social skills and life skills.

I disagree.

Beyond achievement, proponents of homework argue that it can have many other beneficial effects. They claim it can help students develop good study habits so they are ready to grow as their cognitive capacities mature. It can help students recognize that learning can occur at home as well as at school. Homework can foster independent learning and responsible character traits. And it can give parents an opportunity to see what’s going on at school and let them express positive attitudes toward achievement.

Homework is helpful because homework helps us by teaching us how to learn a specific topic.

As a student myself, I can say that I have almost never gotten the full 9 hours of recommended sleep time, because of homework. (Now I’m writing an essay on it in the middle of the night D=)

I am a 10 year old kid doing a report about “Is homework good or bad” for homework before i was going to do homework is bad but the sources from this site changed my mind!

Homeowkr is god for stusenrs

I agree with hunter because homework can be so stressful especially with this whole covid thing no one has time for homework and every one just wants to get back to there normal lives it is especially stressful when you go on a 2 week vaca 3 weeks into the new school year and and then less then a week after you come back from the vaca you are out for over a month because of covid and you have no way to get the assignment done and turned in

As great as homework is said to be in the is article, I feel like the viewpoint of the students was left out. Every where I go on the internet researching about this topic it almost always has interviews from teachers, professors, and the like. However isn’t that a little biased? Of course teachers are going to be for homework, they’re not the ones that have to stay up past midnight completing the homework from not just one class, but all of them. I just feel like this site is one-sided and you should include what the students of today think of spending four hours every night completing 6-8 classes worth of work.

Are we talking about homework or practice? Those are two very different things and can result in different outcomes.

Homework is a graded assignment. I do not know of research showing the benefits of graded assignments going home.

Practice; however, can be extremely beneficial, especially if there is some sort of feedback (not a grade but feedback). That feedback can come from the teacher, another student or even an automated grading program.

As a former band director, I assigned daily practice. I never once thought it would be appropriate for me to require the students to turn in a recording of their practice for me to grade. Instead, I had in-class assignments/assessments that were graded and directly related to the practice assigned.

I would really like to read articles on “homework” that truly distinguish between the two.

oof i feel bad good luck!

thank you guys for the artical because I have to finish an assingment. yes i did cite it but just thanks

thx for the article guys.

Homework is good

I think homework is helpful AND harmful. Sometimes u can’t get sleep bc of homework but it helps u practice for school too so idk.

I agree with this Article. And does anyone know when this was published. I would like to know.

It was published FEb 19, 2019.

Studies have shown that homework improved student achievement in terms of improved grades, test results, and the likelihood to attend college.

i think homework can help kids but at the same time not help kids

This article is so out of touch with majority of homes it would be laughable if it wasn’t so incredibly sad.

There is no value to homework all it does is add stress to already stressed homes. Parents or adults magically having the time or energy to shepherd kids through homework is dome sort of 1950’s fantasy.

What lala land do these teachers live in?

Homework gives noting to the kid

Homework is Bad

homework is bad.

why do kids even have homework?

Comments are closed.

Latest from Bostonia

Could boston be the next city to impose congestion pricing, alum has traveled the world to witness total solar eclipses, opening doors: rhonda harrison (eng’98,’04, grs’04), campus reacts and responds to israel-hamas war, reading list: what the pandemic revealed, remembering com’s david anable, cas’ john stone, “intellectual brilliance and brilliant kindness”, one good deed: christine kannler (cas’96, sph’00, camed’00), william fairfield warren society inducts new members, spreading art appreciation, restoring the “black angels” to medical history, in the kitchen with jacques pépin, feedback: readers weigh in on bu’s new president, com’s new expert on misinformation, and what’s really dividing the nation, the gifts of great teaching, sth’s walter fluker honored by roosevelt institute, alum’s debut book is a ramadan story for children, my big idea: covering construction sites with art, former terriers power new professional women’s hockey league, five trailblazing alums to celebrate during women’s history month, alum beata coloyan is boston mayor michelle wu’s “eyes and ears” in boston neighborhoods.

Does Homework Improve Academic Achievement?

- Share this story on facebook

- Share this story on twitter

- Share this story on reddit

- Share this story on linkedin

- Get this story's permalink

- Print this story

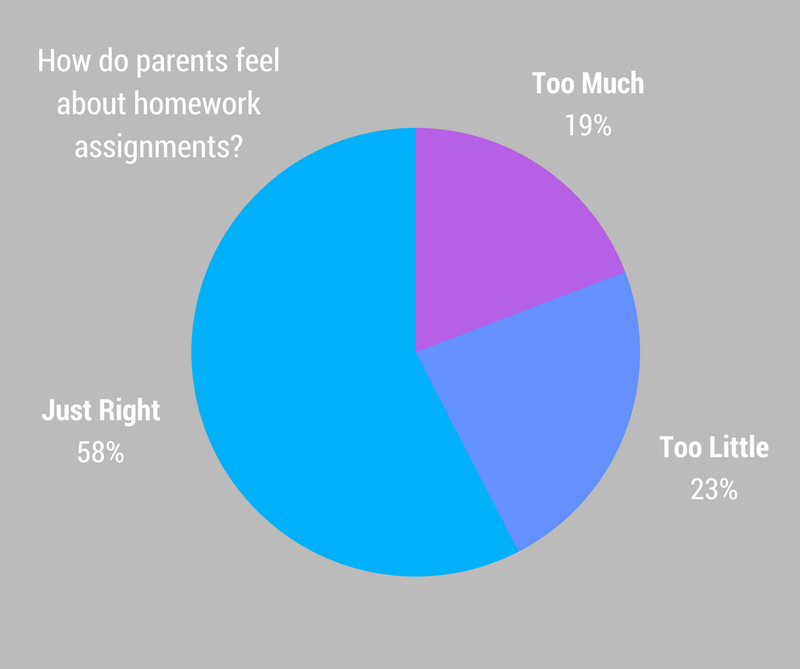

Educators should be thrilled by these numbers. Pleasing a majority of parents regarding homework and having equal numbers of dissenters shouting "too much!" and "too little!" is about as good as they can hope for.

But opinions cannot tell us whether homework works; only research can, which is why my colleagues and I have conducted a combined analysis of dozens of homework studies to examine whether homework is beneficial and what amount of homework is appropriate for our children.

The homework question is best answered by comparing students who are assigned homework with students assigned no homework but who are similar in other ways. The results of such studies suggest that homework can improve students' scores on the class tests that come at the end of a topic. Students assigned homework in 2nd grade did better on math, 3rd and 4th graders did better on English skills and vocabulary, 5th graders on social studies, 9th through 12th graders on American history, and 12th graders on Shakespeare.

Less authoritative are 12 studies that link the amount of homework to achievement, but control for lots of other factors that might influence this connection. These types of studies, often based on national samples of students, also find a positive link between time on homework and achievement.

Yet other studies simply correlate homework and achievement with no attempt to control for student differences. In 35 such studies, about 77 percent find the link between homework and achievement is positive. Most interesting, though, is these results suggest little or no relationship between homework and achievement for elementary school students.

Why might that be? Younger children have less developed study habits and are less able to tune out distractions at home. Studies also suggest that young students who are struggling in school take more time to complete homework assignments simply because these assignments are more difficult for them.

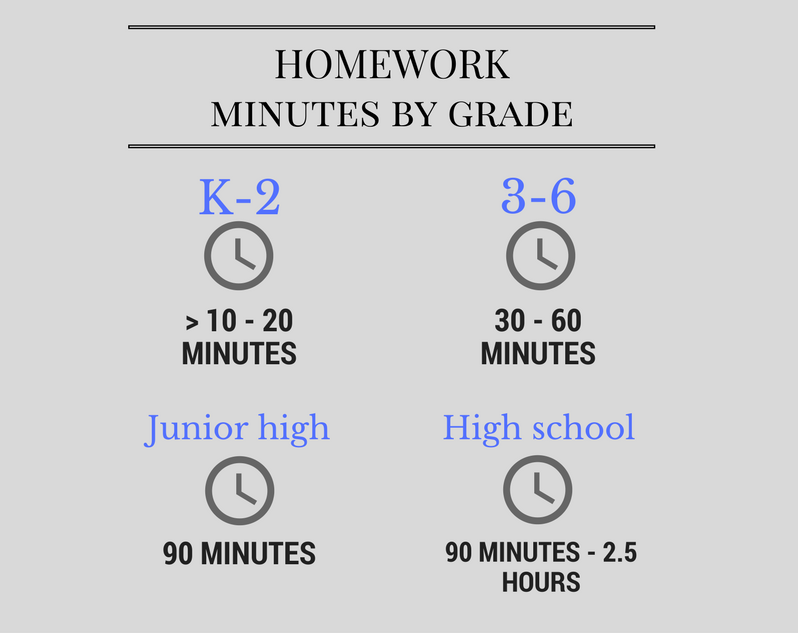

These recommendations are consistent with the conclusions reached by our analysis. Practice assignments do improve scores on class tests at all grade levels. A little amount of homework may help elementary school students build study habits. Homework for junior high students appears to reach the point of diminishing returns after about 90 minutes a night. For high school students, the positive line continues to climb until between 90 minutes and 2½ hours of homework a night, after which returns diminish.

Beyond achievement, proponents of homework argue that it can have many other beneficial effects. They claim it can help students develop good study habits so they are ready to grow as their cognitive capacities mature. It can help students recognize that learning can occur at home as well as at school. Homework can foster independent learning and responsible character traits. And it can give parents an opportunity to see what's going on at school and let them express positive attitudes toward achievement.

Opponents of homework counter that it can also have negative effects. They argue it can lead to boredom with schoolwork, since all activities remain interesting only for so long. Homework can deny students access to leisure activities that also teach important life skills. Parents can get too involved in homework -- pressuring their child and confusing him by using different instructional techniques than the teacher.

My feeling is that homework policies should prescribe amounts of homework consistent with the research evidence, but which also give individual schools and teachers some flexibility to take into account the unique needs and circumstances of their students and families. In general, teachers should avoid either extreme.

Link to this page

Copy and paste the URL below to share this page.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Students' Achievement and Homework Assignment Strategies

Rubén fernández-alonso.

1 Department of Education Sciences, University of Oviedo, Oviedo, Spain

2 Department of Education, Principality of Asturias Government, Oviedo, Spain

Marcos Álvarez-Díaz

Javier suárez-Álvarez.

3 Department of Psychology, University of Oviedo, Oviedo, Spain

José Muñiz

The optimum time students should spend on homework has been widely researched although the results are far from unanimous. The main objective of this research is to analyze how homework assignment strategies in schools affect students' academic performance and the differences in students' time spent on homework. Participants were a representative sample of Spanish adolescents ( N = 26,543) with a mean age of 14.4 (±0.75), 49.7% girls. A test battery was used to measure academic performance in four subjects: Spanish, Mathematics, Science, and Citizenship. A questionnaire allowed the measurement of the indicators used for the description of homework and control variables. Two three-level hierarchical-linear models (student, school, autonomous community) were produced for each subject being evaluated. The relationship between academic results and homework time is negative at the individual level but positive at school level. An increase in the amount of homework a school assigns is associated with an increase in the differences in student time spent on homework. An optimum amount of homework is proposed which schools should assign to maximize gains in achievement for students overall.

The role of homework in academic achievement is an age-old debate (Walberg et al., 1985 ) that has swung between times when it was thought to be a tool for improving a country's competitiveness and times when it was almost outlawed. So Cooper ( 2001 ) talks about the battle over homework and the debates and rows continue (Walberg et al., 1985 , 1986 ; Barber, 1986 ). It is considered a complicated subject (Corno, 1996 ), mysterious (Trautwein and Köller, 2003 ), a chameleon (Trautwein et al., 2009b ), or Janus-faced (Flunger et al., 2015 ). One must agree with Cooper et al. ( 2006 ) that homework is a practice full of contradictions, where positive and negative effects coincide. As such, depending on our preferences, it is possible to find data which support the argument that homework benefits all students (Cooper, 1989 ), or that it does not matter and should be abolished (Barber, 1986 ). Equally, one might argue a compensatory effect as it favors students with more difficulties (Epstein and Van Voorhis, 2001 ), or on the contrary, that it is a source of inequality as it specifically benefits those better placed on the social ladder (Rømming, 2011 ). Furthermore, this issue has jumped over the school wall and entered the home, contributing to the polemic by becoming a common topic about which it is possible to have an opinion without being well informed, something that Goldstein ( 1960 ) warned of decades ago after reviewing almost 300 pieces of writing on the topic in Education Index and finding that only 6% were empirical studies.

The relationship between homework time and educational outcomes has traditionally been the most researched aspect (Cooper, 1989 ; Cooper et al., 2006 ; Fan et al., 2017 ), although conclusions have evolved over time. The first experimental studies (Paschal et al., 1984 ) worked from the hypothesis that time spent on homework was a reflection of an individual student's commitment and diligence and as such the relationship between time spent on homework and achievement should be positive. This was roughly the idea at the end of the twentieth century, when more positive effects had been found than negative (Cooper, 1989 ), although it was also known that the relationship was not strictly linear (Cooper and Valentine, 2001 ), and that its strength depended on the student's age- stronger in post-compulsory secondary education than in compulsory education and almost zero in primary education (Cooper et al., 2012 ). With the turn of the century, hierarchical-linear models ran counter to this idea by showing that homework was a multilevel situation and the effect of homework on outcomes depended on classroom factors (e.g., frequency or amount of assigned homework) more than on an individual's attitude (Trautwein and Köller, 2003 ). Research with a multilevel approach indicated that individual variations in time spent had little effect on academic results (Farrow et al., 1999 ; De Jong et al., 2000 ; Dettmers et al., 2010 ; Murillo and Martínez-Garrido, 2013 ; Fernández-Alonso et al., 2014 ; Núñez et al., 2014 ; Servicio de Evaluación Educativa del Principado de Asturias, 2016 ) and that when statistically significant results were found, the effect was negative (Trautwein, 2007 ; Trautwein et al., 2009b ; Lubbers et al., 2010 ; Chang et al., 2014 ). The reasons for this null or negative relationship lie in the fact that those variables which are positively associated with homework time are antagonistic when predicting academic performance. For example, some students may not need to spend much time on homework because they learn quickly and have good cognitive skills and previous knowledge (Trautwein, 2007 ; Dettmers et al., 2010 ), or maybe because they are not very persistent in their work and do not finish homework tasks (Flunger et al., 2015 ). Similarly, students may spend more time on homework because they have difficulties learning and concentrating, low expectations and motivation or because they need more direct help (Trautwein et al., 2006 ), or maybe because they put in a lot of effort and take a lot of care with their work (Flunger et al., 2015 ). Something similar happens with sociological variables such as gender: Girls spend more time on homework (Gershenson and Holt, 2015 ) but, compared to boys, in standardized tests they have better results in reading and worse results in Science and Mathematics (OECD, 2013a ).

On the other hand, thanks to multilevel studies, systematic effects on performance have been found when homework time is considered at the class or school level. De Jong et al. ( 2000 ) found that the number of assigned homework tasks in a year was positively and significantly related to results in mathematics. Equally, the volume or amount of homework (mean homework time for the group) and the frequency of homework assignment have positive effects on achievement. The data suggests that when frequency and volume are considered together, the former has more impact on results than the latter (Trautwein et al., 2002 ; Trautwein, 2007 ). In fact, it has been estimated that in classrooms where homework is always assigned there are gains in mathematics and science of 20% of a standard deviation over those classrooms which sometimes assign homework (Fernández-Alonso et al., 2015 ). Significant results have also been found in research which considered only homework volume at the classroom or school level. Dettmers et al. ( 2009 ) concluded that the school-level effect of homework is positive in the majority of participating countries in PISA 2003, and the OECD ( 2013b ), with data from PISA 2012, confirms that schools in which students have more weekly homework demonstrate better results once certain school and student-background variables are discounted. To put it briefly, homework has a multilevel nature (Trautwein and Köller, 2003 ) in which the variables have different significance and effects according to the level of analysis, in this case a positive effect at class level, and a negative or null effect in most cases at the level of the individual. Furthermore, the fact that the clearest effects are seen at the classroom and school level highlights the role of homework policy in schools and teaching, over and above the time individual students spend on homework.

From this complex context, this current study aims to explore the relationships between the strategies schools use to assign homework and the consequences that has on students' academic performance and on the students' own homework strategies. There are two specific objectives, firstly, to systematically analyze the differential effect of time spent on homework on educational performance, both at school and individual level. We hypothesize a positive effect for homework time at school level, and a negative effect at the individual level. Secondly, the influence of homework quantity assigned by schools on the distribution of time spent by students on homework will be investigated. This will test the previously unexplored hypothesis that an increase in the amount of homework assigned by each school will create an increase in differences, both in time spent on homework by the students, and in academic results. Confirming this hypothesis would mean that an excessive amount of homework assigned by schools would penalize those students who for various reasons (pace of work, gaps in learning, difficulties concentrating, overexertion) need to spend more time completing their homework than their peers. In order to resolve this apparent paradox we will calculate the optimum volume of homework that schools should assign in order to benefit the largest number of students without contributing to an increase in differences, that is, without harming educational equity.

Participants

The population was defined as those students in year 8 of compulsory education in the academic year 2009/10 in Spain. In order to provide a representative sample, a stratified random sampling was carried out from the 19 autonomous regions in Spain. The sample was selected from each stratum according to a two-stage cluster design (OECD, 2009 , 2011 , 2014a ; Ministerio de Educación, 2011 ). In the first stage, the primary units of the sample were the schools, which were selected with a probability proportional to the number of students in the 8th grade. The more 8th grade students in a given school, the higher the likelihood of the school being selected. In the second stage, 35 students were selected from each school through simple, systematic sampling. A detailed, step-by-step description of the sampling procedure may be found in OECD ( 2011 ). The subsequent sample numbered 29,153 students from 933 schools. Some students were excluded due to lack of information (absences on the test day), or for having special educational needs. The baseline sample was finally made up of 26,543 students. The mean student age was 14.4 with a standard deviation of 0.75, rank of age from 13 to 16. Some 66.2% attended a state school; 49.7% were girls; 87.8% were Spanish nationals; 73.5% were in the school year appropriate to their age, the remaining 26.5% were at least 1 year behind in terms of their age.

Test application, marking, and data recording were contracted out via public tendering, and were carried out by qualified personnel unconnected to the schools. The evaluation, was performed on two consecutive days, each day having two 50 min sessions separated by a break. At the end of the second day the students completed a context questionnaire which included questions related to homework. The evaluation was carried out in compliance with current ethical standards in Spain. Families of the students selected to participate in the evaluation were informed about the study by the school administrations, and were able to choose whether those students would participate in the study or not.

Instruments

Tests of academic performance.

The performance test battery consisted of 342 items evaluating four subjects: Spanish (106 items), mathematics (73 items), science (78), and citizenship (85). The items, completed on paper, were in various formats and were subject to binary scoring, except 21 items which were coded on a polytomous scale, between 0 and 2 points (Ministerio de Educación, 2011 ). As a single student is not capable of answering the complete item pool in the time given, the items were distributed across various booklets following a matrix design (Fernández-Alonso and Muñiz, 2011 ). The mean Cronbach α for the booklets ranged from 0.72 (mathematics) to 0.89 (Spanish). Student scores were calculated adjusting the bank of items to Rasch's IRT model using the ConQuest 2.0 program (Wu et al., 2007 ) and were expressed in a scale with mean and standard deviation of 500 and 100 points respectively. The student's scores were divided into five categories, estimated using the plausible values method. In large scale assessments this method is better at recovering the true population parameters (e.g., mean, standard deviation) than estimates of scores using methods of maximum likelihood or expected a-posteriori estimations (Mislevy et al., 1992 ; OECD, 2009 ; von Davier et al., 2009 ).

Homework variables

A questionnaire was made up of a mix of items which allowed the calculation of the indicators used for the description of homework variables. Daily minutes spent on homework was calculated from a multiple choice question with the following options: (a) Generally I don't have homework; (b) 1 h or less; (c) Between 1 and 2 h; (d) Between 2 and 3 h; (e) More than 3 h. The options were recoded as follows: (a) = 0 min.; (b) = 45 min.; (c) = 90 min.; (d) = 150 min.; (e) = 210 min. According to Trautwein and Köller ( 2003 ) the average homework time of the students in a school could be regarded as a good proxy for the amount of homework assigned by the teacher. So the mean of this variable for each school was used as an estimator of Amount or volume of homework assigned .

Control variables

Four variables were included to describe sociological factors about the students, three were binary: Gender (1 = female ); Nationality (1 = Spanish; 0 = other ); School type (1 = state school; 0 = private ). The fourth variable was Socioeconomic and cultural index (SECI), which is constructed with information about family qualifications and professions, along with the availability of various material and cultural resources at home. It is expressed in standardized points, N(0,1) . Three variables were used to gather educational history: Appropriate School Year (1 = being in the school year appropriate to their age ; 0 = repeated a school year) . The other two adjustment variables were Academic Expectations and Motivation which were included for two reasons: they are both closely connected to academic achievement (Suárez-Álvarez et al., 2014 ). Their position as adjustment factors is justified because, in an ex-post facto descriptive design such as this, both expectations and motivation may be thought of as background variables that the student brings with them on the day of the test. Academic expectations for finishing education was measured with a multiple-choice item where the score corresponds to the years spent in education in order to reach that level of qualification: compulsory secondary education (10 points); further secondary education (12 points); non-university higher education (14 points); University qualification (16 points). Motivation was constructed from the answers to six four-point Likert items, where 1 means strongly disagree with the sentence and 4 means strongly agree. Students scoring highly in this variable are agreeing with statements such as “at school I learn useful and interesting things.” A Confirmatory Factor Analysis was performed using a Maximum Likelihood robust estimation method (MLMV) and the items fit an essentially unidimensional scale: CFI = 0.954; TLI = 0.915; SRMR = 0.037; RMSEA = 0.087 (90% CI = 0.084–0.091).

As this was an official evaluation, the tests used were created by experts in the various fields, contracted by the Spanish Ministry of Education in collaboration with the regional education authorities.

Data analyses

Firstly the descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations between the variables were calculated. Then, using the HLM 6.03 program (Raudenbush et al., 2004 ), two three-level hierarchical-linear models (student, school, autonomous community) were produced for each subject being evaluated: a null model (without predictor variables) and a random intercept model in which adjustment variables and homework variables were introduced at the same time. Given that HLM does not return standardized coefficients, all of the variables were standardized around the general mean, which allows the interpretation of the results as classical standardized regression analysis coefficients. Levels 2 and 3 variables were constructed from means of standardized level 1 variables and were not re-standardized. Level 1 variables were introduced without centering except for four cases: study time, motivation, expectation, and socioeconomic and cultural level which were centered on the school mean to control composition effects (Xu and Wu, 2013 ) and estimate the effect of differences in homework time among the students within the same school. The range of missing variable cases was very small, between 1 and 3%. Recovery was carried out using the procedure described in Fernández-Alonso et al. ( 2012 ).

The results are presented in two ways: the tables show standardized coefficients while in the figures the data are presented in a real scale, taking advantage of the fact that a scale with a 100 point standard deviation allows the expression of the effect of the variables and the differences between groups as percentage increases in standardized points.

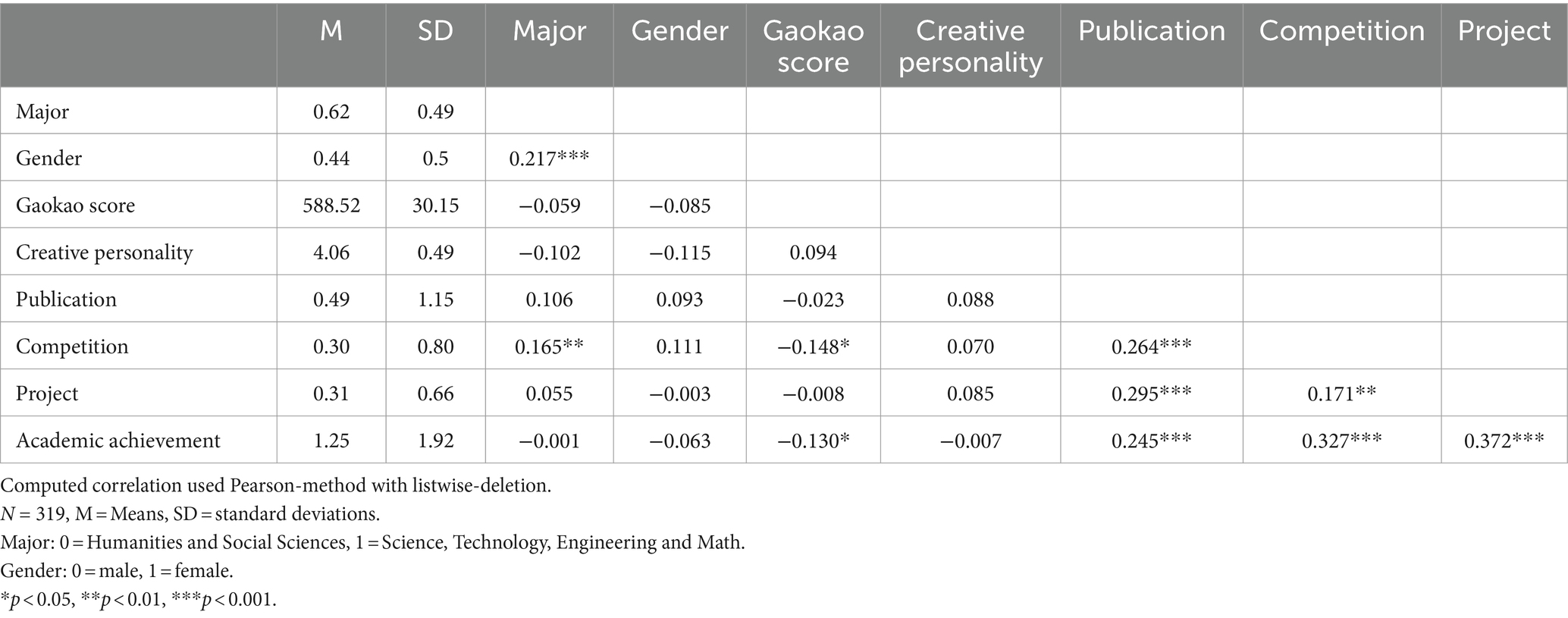

Table Table1 1 shows the descriptive statistics and the matrix of correlations between the study variables. As can be seen in the table, the relationship between the variables turned out to be in the expected direction, with the closest correlations between the different academic performance scores and socioeconomic level, appropriate school year, and student expectations. The nationality variable gave the highest asymmetry and kurtosis, which was to be expected as the majority of the sample are Spanish.

Descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation matrix between the variables .

Table Table2 2 shows the distribution of variance in the null model. In the four subjects taken together, 85% of the variance was found at the student level, 10% was variance between schools, and 5% variance between regions. Although the 10% of variance between schools could seem modest, underlying that there were large differences. For example, in Spanish the 95% plausible value range for the school means ranged between 577 and 439 points, practically 1.5 standard deviations, which shows that schools have a significant impact on student results.

Distribution of the variance in the null model .

Table Table3 3 gives the standardized coefficients of the independent variables of the four multilevel models, as well as the percentage of variance explained by each level.

Multilevel models for prediction of achievement in four subjects .

β, Standardized weight; SE, Standard Error; SECI, Socioeconomic and cultural index; AC, Autonomous Communities .

The results indicated that the adjustment variables behaved satisfactorily, with enough control to analyze the net effects of the homework variables. This was backed up by two results, firstly, the two variables with highest standardized coefficients were those related to educational history: academic expectations at the time of the test, and being in the school year corresponding to age. Motivation demonstrated a smaller effect but one which was significant in all cases. Secondly, the adjustment variables explained the majority of the variance in the results. The percentages of total explained variance in Table Table2 2 were calculated with all variables. However, if the strategy had been to introduce the adjustment variables first and then add in the homework variables, the explanatory gain in the second model would have been about 2% in each subject.

The amount of homework turned out to be positively and significantly associated with the results in the four subjects. In a 100 point scale of standard deviation, controlling for other variables, it was estimated that for each 10 min added to the daily volume of homework, schools would achieve between 4.1 and 4.8 points more in each subject, with the exception of mathematics where the increase would be around 2.5 points. In other words, an increase of between 15 and 29 points in the school mean is predicted for each additional hour of homework volume of the school as a whole. This school level gain, however, would only occur if the students spent exactly the same time on homework as their school mean. As the regression coefficient of student homework time is negative and the variable is centered on the level of the school, the model predicts deterioration in results for those students who spend more time than their class mean on homework, and an improvement for those who finish their homework more quickly than the mean of their classmates.

Furthermore, the results demonstrated a positive association between the amount of homework assigned in a school and the differences in time needed by the students to complete their homework. Figure Figure1 1 shows the relationship between volume of homework (expressed as mean daily minutes of homework by school) and the differences in time spent by students (expressed as the standard deviation from the mean school daily minutes). The correlation between the variables was 0.69 and the regression gradient indicates that schools which assigned 60 min of homework per day had a standard deviation in time spent by students on homework of approximately 25 min, whereas in those schools assigning 120 min of homework, the standard deviation was twice as long, and was over 50 min. So schools which assigned more homework also tended to demonstrate greater differences in the time students need to spend on that homework.

Relationship between school homework volume and differences in time needed by students to complete homework .

Figure Figure2 2 shows the effect on results in mathematics of the combination of homework time, homework amount, and the variance of homework time associated with the amount of homework assigned in two types of schools: in type 1 schools the amount of homework assigned is 1 h, and in type 2 schools the amount of homework 2 h. The result in mathematics was used as a dependent variable because, as previously noted, it was the subject where the effect was smallest and as such is the most conservative prediction. With other subjects the results might be even clearer.

Prediction of results for quick and slow students according to school homework size .

Looking at the first standard deviation of student homework time shown in the first graph, it was estimated that in type 1 schools, which assign 1 h of daily homework, a quick student (one who finishes their homework before 85% of their classmates) would spend a little over half an hour (35 min), whereas the slower student, who spends more time than 85% of classmates, would need almost an hour and a half of work each day (85 min). In type 2 schools, where the homework amount is 2 h a day, the differences increase from just over an hour (65 min for a quick student) to almost 3 h (175 min for a slow student). Figure Figure2 2 shows how the differences in performance would vary within a school between the more and lesser able students according to amount of homework assigned. In type 1 schools, with 1 h of homework per day, the difference in achievement between quick and slow students would be around 5% of a standard deviation, while in schools assigning 2 h per day the difference would be 12%. On the other hand, the slow student in a type 2 school would score 6 points more than the quick student in a type 1 school. However, to achieve this, the slow student in a type 2 school would need to spend five times as much time on homework in a week (20.4 weekly hours rather than 4.1). It seems like a lot of work for such a small gain.

Discussion and conclusions

The data in this study reaffirm the multilevel nature of homework (Trautwein and Köller, 2003 ) and support this study's first hypothesis: the amount of homework (mean daily minutes the student spends on homework) is positively associated with academic results, whereas the time students spent on homework considered individually is negatively associated with academic results. These findings are in line with previous research, which indicate that school-level variables, such as amount of homework assigned, have more explanatory power than individual variables such as time spent (De Jong et al., 2000 ; Dettmers et al., 2010 ; Scheerens et al., 2013 ; Fernández-Alonso et al., 2015 ). In this case it was found that for each additional hour of homework assigned by a school, a gain of 25% of a standard deviation is expected in all subjects except mathematics, where the gain is around 15%. On the basis of this evidence, common sense would dictate the conclusion that frequent and abundant homework assignment may be one way to improve school efficiency.

However, as noted previously, the relationship between homework and achievement is paradoxical- appearances are deceptive and first conclusions are not always confirmed. Analysis demonstrates another two complementary pieces of data which, read together, raise questions about the previous conclusion. In the first place, time spent on homework at the individual level was found to have a negative effect on achievement, which confirms the findings of other multilevel-approach research (Trautwein, 2007 ; Trautwein et al., 2009b ; Chang et al., 2014 ; Fernández-Alonso et al., 2016 ). Furthermore, it was found that an increase in assigned homework volume is associated with an increase in the differences in time students need to complete it. Taken together, the conclusion is that, schools with more homework tend to exhibit more variation in student achievement. These results seem to confirm our second hypothesis, as a positive covariation was found between the amount of homework in a school (the mean homework time by school) and the increase in differences within the school, both in student homework time and in the academic results themselves. The data seem to be in line with those who argue that homework is a source of inequity because it affects those less academically-advantaged students and students with greater limitations in their home environments (Kohn, 2006 ; Rømming, 2011 ; OECD, 2013b ).

This new data has clear implications for educational action and school homework policies, especially in compulsory education. If quality compulsory education is that which offers the best results for the largest number (Barber and Mourshed, 2007 ; Mourshed et al., 2010 ), then assigning an excessive volume of homework at those school levels could accentuate differences, affecting students who are slower, have more gaps in their knowledge, or are less privileged, and can make them feel overwhelmed by the amount of homework assigned to them (Martinez, 2011 ; OECD, 2014b ; Suárez et al., 2016 ). The data show that in a school with 60 min of assigned homework, a quick student will need just 4 h a week to finish their homework, whereas a slow student will spend 10 h a week, 2.5 times longer, with the additional aggravation of scoring one twentieth of a standard deviation below their quicker classmates. And in a school assigning 120 min of homework per day, a quick student will need 7.5 h per week whereas a slow student will have to triple this time (20 h per week) to achieve a result one eighth worse, that is, more time for a relatively worse result.

It might be argued that the differences are not very large, as between 1 and 2 h of assigned homework, the level of inequality increases 7% on a standardized scale. But this percentage increase has been estimated after statistically, or artificially, accounting for sociological and psychological student factors and other variables at school and region level. The adjustment variables influence both achievement and time spent on homework, so it is likely that in a real classroom situation the differences estimated here might be even larger. This is especially important in comprehensive education systems, like the Spanish (Eurydice, 2015 ), in which the classroom groups are extremely heterogeneous, with a variety of students in the same class in terms of ability, interest, and motivation, in which the aforementioned variables may operate more strongly.

The results of this research must be interpreted bearing in mind a number of limitations. The most significant limitation in the research design is the lack of a measure of previous achievement, whether an ad hoc test (Murillo and Martínez-Garrido, 2013 ) or school grades (Núñez et al., 2014 ), which would allow adjustment of the data. In an attempt to alleviate this, our research has placed special emphasis on the construction of variables which would work to exclude academic history from the model. The use of the repetition of school year variable was unavoidable because Spain has one of the highest levels of repetition in the European Union (Eurydice, 2011 ) and repeating students achieve worse academic results (Ministerio de Educación, 2011 ). Similarly, the expectation and motivation variables were included in the group of adjustment factors assuming that in this research they could be considered background variables. In this way, once the background factors are discounted, the homework variables explain 2% of the total variance, which is similar to estimations from other multilevel studies (De Jong et al., 2000 ; Trautwein, 2007 ; Dettmers et al., 2009 ; Fernández-Alonso et al., 2016 ). On the other hand, the statistical models used to analyze the data are correlational, and as such, one can only speak of an association between variables and not of directionality or causality in the analysis. As Trautwein and Lüdtke ( 2009 ) noted, the word “effect” must be understood as “predictive effect.” In other words, it is possible to say that the amount of homework is connected to performance; however, it is not possible to say in which direction the association runs. Another aspect to be borne in mind is that the homework time measures are generic -not segregated by subject- when it its understood that time spent and homework behavior are not consistent across all subjects (Trautwein et al., 2006 ; Trautwein and Lüdtke, 2007 ). Nonetheless, when the dependent variable is academic results it has been found that the relationship between homework time and achievement is relatively stable across all subjects (Lubbers et al., 2010 ; Chang et al., 2014 ) which leads us to believe that the results given here would have changed very little even if the homework-related variables had been separated by subject.

Future lines of research should be aimed toward the creation of comprehensive models which incorporate a holistic vision of homework. It must be recognized that not all of the time spent on homework by a student is time well spent (Valle et al., 2015 ). In addition, research has demonstrated the importance of other variables related to student behavior such as rate of completion, the homework environment, organization, and task management, autonomy, parenting styles, effort, and the use of study techniques (Zimmerman and Kitsantas, 2005 ; Xu, 2008 , 2013 ; Kitsantas and Zimmerman, 2009 ; Kitsantas et al., 2011 ; Ramdass and Zimmerman, 2011 ; Bembenutty and White, 2013 ; Xu and Wu, 2013 ; Xu et al., 2014 ; Rosário et al., 2015a ; Osorio and González-Cámara, 2016 ; Valle et al., 2016 ), as well as the role of expectation, value given to the task, and personality traits (Lubbers et al., 2010 ; Goetz et al., 2012 ; Pedrosa et al., 2016 ). Along the same lines, research has also indicated other important variables related to teacher homework policies, such as reasons for assignment, control and feedback, assignment characteristics, and the adaptation of tasks to the students' level of learning (Trautwein et al., 2009a ; Dettmers et al., 2010 ; Patall et al., 2010 ; Buijs and Admiraal, 2013 ; Murillo and Martínez-Garrido, 2013 ; Rosário et al., 2015b ). All of these should be considered in a comprehensive model of homework.

In short, the data seem to indicate that in year 8 of compulsory education, 60–70 min of homework a day is a recommendation that, slightly more optimistically than Cooper's ( 2001 ) “10 min rule,” gives a reasonable gain for the whole school, without exaggerating differences or harming students with greater learning difficulties or who work more slowly, and is in line with other available evidence (Fernández-Alonso et al., 2015 ). These results have significant implications when it comes to setting educational policy in schools, sending a clear message to head teachers, teachers and those responsible for education. The results of this research show that assigning large volumes of homework increases inequality between students in pursuit of minimal gains in achievement for those who least need it. Therefore, in terms of school efficiency, and with the aim of improving equity in schools it is recommended that educational policies be established which optimize all students' achievement.

Ethics statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the University of Oviedo with written informed consent from all subjects. All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the University of Oviedo.

Author contributions

RF and JM have designed the research; RF and JS have analyzed the data; MA and JM have interpreted the data; RF, MA, and JS have drafted the paper; JM has revised it critically; all authors have provided final approval of the version to be published and have ensured the accuracy and integrity of the work.

This research was funded by the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad del Gobierno de España. References: PSI2014-56114-P, BES2012-053488. We would like to express our utmost gratitude to the Ministerio de Educación Cultura y Deporte del Gobierno de España and to the Consejería de Educación y Cultura del Gobierno del Principado de Asturias, without whose collaboration this research would not have been possible.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

- Barber B. (1986). Homework does not belong on the agenda for educational reform . Educ. Leadersh. 43 , 55–57. [ Google Scholar ]

- Barber M., Mourshed M. (2007). How the World's Best-Performing School Systems Come Out on Top. McKinsey and Company . Available online at: http://mckinseyonsociety.com/downloads/reports/Education/Worlds_School_Systems_Final.pdf (Accessed January 25, 2016).

- Bembenutty H., White M. C. (2013). Academic performance and satisfaction with homework completion among college students . Learn. Individ. Differ. 24 , 83–88. 10.1016/j.lindif.2012.10.013 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Buijs M., Admiraal W. (2013). Homework assignments to enhance student engagement in secondary education . Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 28 , 767–779. 10.1007/s10212-012-0139-0 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chang C. B., Wall D., Tare M., Golonka E., Vatz K. (2014). Relations of attitudes toward homework and time spent on homework to course outcomes: the case of foreign language learning . J. Educ. Psychol. 106 , 1049–1065. 10.1037/a0036497 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cooper H. (1989). Synthesis of research on homework . Educ. Leadersh. 47 , 85–91. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cooper H. (2001). The Battle Over Homework: Common Ground for Administrators, Teachers, and Parents . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Google Scholar ]