15.1 The Sociological Approach to Religion

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you should be able to:

- Discuss the historical view of religion from a sociological perspective

- Describe how the major sociological paradigms view religion

From the Latin religio (respect for what is sacred) and religare (to bind, in the sense of an obligation), the term religion describes various systems of belief and practice that define what people consider to be sacred or spiritual (Fasching and deChant 2001; Durkheim 1915). Throughout history, and in societies across the world, leaders have used religious narratives, symbols, and traditions in an attempt to give more meaning to life and understand the universe. Some form of religion is found in every known culture, and it is usually practiced in a public way by a group. The practice of religion can include feasts and festivals, intercession with God or gods, marriage and funeral services, music and art, meditation or initiation, sacrifice or service, and other aspects of culture.

While some people think of religion as something individual because religious beliefs can be highly personal, religion is also a social institution. Social scientists recognize that religion exists as an organized and integrated set of beliefs, behaviors, and norms centered on basic social needs and values. Moreover, religion is a cultural universal found in all social groups. For instance, in every culture, funeral rites are practiced in some way, although these customs vary between cultures and within religious affiliations. Despite differences, there are common elements in a ceremony marking a person’s death, such as announcement of the death, care of the deceased, disposition, and ceremony or ritual. These universals, and the differences in the way societies and individuals experience religion, provide rich material for sociological study.

In studying religion, sociologists distinguish between what they term the experience, beliefs, and rituals of a religion. Religious experience refers to the conviction or sensation that we are connected to “the divine.” This type of communion might be experienced when people pray or meditate. Religious beliefs are specific ideas members of a particular faith hold to be true, such as that Jesus Christ was the son of God, or that reincarnation exists. Another illustration of religious beliefs is the creation stories we find in different religions. Religious rituals are behaviors or practices that are either required or expected of the members of a particular group, such as bar mitzvah or confession of sins (Barkan and Greenwood 2003).

The History of Religion as a Sociological Concept

In the wake of nineteenth century European industrialization and secularization, three social theorists attempted to examine the relationship between religion and society: Émile Durkheim, Max Weber, and Karl Marx. They are among the founding thinkers of modern sociology.

As stated earlier, French sociologist Émile Durkheim (1858–1917) defined religion as a “unified system of beliefs and practices relative to sacred things” (1915). To him, sacred meant extraordinary—something that inspired wonder and that seemed connected to the concept of “the divine.” Durkheim argued that “religion happens” in society when there is a separation between the profane (ordinary life) and the sacred (1915). A rock, for example, isn’t sacred or profane as it exists. But if someone makes it into a headstone, or another person uses it for landscaping, it takes on different meanings—one sacred, one profane.

Durkheim is generally considered the first sociologist who analyzed religion in terms of its societal impact. Above all, he believed religion is about community: It binds people together (social cohesion), promotes behavior consistency (social control), and offers strength during life’s transitions and tragedies (meaning and purpose). By applying the methods of natural science to the study of society, Durkheim held that the source of religion and morality is the collective mind-set of society and that the cohesive bonds of social order result from common values in a society. He contended that these values need to be maintained to maintain social stability.

But what would happen if religion were to decline? This question led Durkheim to posit that religion is not just a social creation but something that represents the power of society: When people celebrate sacred things, they celebrate the power of their society. By this reasoning, even if traditional religion disappeared, society wouldn’t necessarily dissolve.

Whereas Durkheim saw religion as a source of social stability, German sociologist and political economist Max Weber (1864–1920) believed it was a precipitator of social change. He examined the effects of religion on economic activities and noticed that heavily Protestant societies—such as those in the Netherlands, England, Scotland, and Germany—were the most highly developed capitalist societies and that their most successful business leaders were Protestant. In his writing The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1905), he contends that the Protestant work ethic influenced the development of capitalism. Weber noted that certain kinds of Protestantism supported the pursuit of material gain by motivating believers to work hard, be successful, and not spend their profits on frivolous things. (The modern use of “work ethic” comes directly from Weber’s Protestant ethic, although it has now lost its religious connotations.)

Big Picture

The protestant work ethic in the information age.

Max Weber (1904) posited that, in Europe in his time, Protestants were more likely than Catholics to value capitalist ideology, and believed in hard work and savings. He showed that Protestant values directly influenced the rise of capitalism and helped create the modern world order. Weber thought the emphasis on community in Catholicism versus the emphasis on individual achievement in Protestantism made a difference. His century-old claim that the Protestant work ethic led to the development of capitalism has been one of the most important and controversial topics in the sociology of religion. In fact, scholars have found little merit to his contention when applied to modern society (Greeley 1989).

What does the concept of work ethic mean today? The work ethic in the information age has been affected by tremendous cultural and social change, just as workers in the mid- to late nineteenth century were influenced by the wake of the Industrial Revolution. Factory jobs tend to be simple, uninvolved, and require very little thinking or decision making on the part of the worker. Today, the work ethic of the modern workforce has been transformed, as more thinking and decision making is required. Employees also seek autonomy and fulfillment in their jobs, not just wages. Higher levels of education have become necessary, as well as people management skills and access to the most recent information on any given topic. The information age has increased the rapid pace of production expected in many jobs.

On the other hand, the “McDonaldization” of the United States (Hightower 1975; Ritzer 1993), in which many service industries, such as the fast-food industry, have established routinized roles and tasks, has resulted in a “discouragement” of the work ethic. In jobs where roles and tasks are highly prescribed, workers have no opportunity to make decisions. They are considered replaceable commodities as opposed to valued employees. During times of recession, these service jobs may be the only employment possible for younger individuals or those with low-level skills. The pay, working conditions, and robotic nature of the tasks dehumanizes the workers and strips them of incentives for doing quality work.

Working hard also doesn’t seem to have any relationship with Catholic or Protestant religious beliefs anymore, or those of other religions; information age workers expect talent and hard work to be rewarded by material gain and career advancement.

German philosopher, journalist, and revolutionary socialist Karl Marx (1818–1883) also studied the social impact of religion. He believed religion reflects the social stratification of society and that it maintains inequality and perpetuates the status quo. For him, religion was just an extension of working-class (proletariat) economic suffering. He famously argued that religion “is the opium of the people” (1844).

For Durkheim, Weber, and Marx, who were reacting to the great social and economic upheaval of the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century in Europe, religion was an integral part of society. For Durkheim, religion was a force for cohesion that helped bind the members of society to the group, while Weber believed religion could be understood as something separate from society. Marx considered religion inseparable from the economy and the worker. Religion could not be understood apart from the capitalist society that perpetuated inequality. Despite their different views, these social theorists all believed in the centrality of religion to society.

Theoretical Perspectives on Religion

Modern-day sociologists often apply one of three major theoretical perspectives. These views offer different lenses through which to study and understand society: functionalism, symbolic interactionism, and conflict theory. Let’s explore how scholars applying these paradigms understand religion.

Functionalism

Functionalists contend that religion serves several functions in society. Religion, in fact, depends on society for its existence, value, and significance, and vice versa. From this perspective, religion serves several purposes, like providing answers to spiritual mysteries, offering emotional comfort, and creating a place for social interaction and social control.

In providing answers, religion defines the spiritual world and spiritual forces, including divine beings. For example, it helps answer questions like, “How was the world created?” “Why do we suffer?” “Is there a plan for our lives?” and “Is there an afterlife?” As another function, religion provides emotional comfort in times of crisis. Religious rituals bring order, comfort, and organization through shared familiar symbols and patterns of behavior.

One of the most important functions of religion, from a functionalist perspective, is the opportunities it creates for social interaction and the formation of groups. It provides social support and social networking and offers a place to meet others who hold similar values and a place to seek help (spiritual and material) in times of need. Moreover, it can foster group cohesion and integration. Because religion can be central to many people’s concept of themselves, sometimes there is an “in-group” versus “out-group” feeling toward other religions in our society or within a particular practice. On an extreme level, the Inquisition, the Salem witch trials, and anti-Semitism are all examples of this dynamic. Finally, religion promotes social control: It reinforces social norms such as appropriate styles of dress, following the law, and regulating sexual behavior.

Conflict Theory

Conflict theorists view religion as an institution that helps maintain patterns of social inequality. For example, the Vatican has a tremendous amount of wealth, while the average income of Catholic parishioners is small. According to this perspective, religion has been used to support the “divine right” of oppressive monarchs and to justify unequal social structures, like India’s caste system.

Conflict theorists are critical of the way many religions promote the idea that believers should be satisfied with existing circumstances because they are divinely ordained. This power dynamic has been used by Christian institutions for centuries to keep poor people poor and to teach them that they shouldn’t be concerned with what they lack because their “true” reward (from a religious perspective) will come after death. Conflict theorists also point out that those in power in a religion are often able to dictate practices, rituals, and beliefs through their interpretation of religious texts or via proclaimed direct communication from the divine.

The feminist perspective is a conflict theory view that focuses specifically on gender inequality. In terms of religion, feminist theorists assert that, although women are typically the ones to socialize children into a religion, they have traditionally held very few positions of power within religions. A few religions and religious denominations are more gender equal, but male dominance remains the norm of most.

Sociology in the Real World

Rational choice theory: can economic theory be applied to religion.

How do people decide which religion to follow, if any? How does one pick a church or decide which denomination “fits” best? Rational choice theory (RCT) is one way social scientists have attempted to explain these behaviors. The theory proposes that people are self-interested, though not necessarily selfish, and that people make rational choices—choices that can reasonably be expected to maximize positive outcomes while minimizing negative outcomes. Sociologists Roger Finke and Rodney Stark (1988) first considered the use of RCT to explain some aspects of religious behavior, with the assumption that there is a basic human need for religion in terms of providing belief in a supernatural being, a sense of meaning in life, and belief in life after death. Religious explanations of these concepts are presumed to be more satisfactory than scientific explanations, which may help to account for the continuation of strong religious connectedness in countries such as the United States, despite predictions of some competing theories for a great decline in religious affiliation due to modernization and religious pluralism.

Another assumption of RCT is that religious organizations can be viewed in terms of “costs” and “rewards.” Costs are not only monetary requirements, but are also the time, effort, and commitment demands of any particular religious organization. Rewards are the intangible benefits in terms of belief and satisfactory explanations about life, death, and the supernatural, as well as social rewards from membership. RCT proposes that, in a pluralistic society with many religious options, religious organizations will compete for members, and people will choose between different churches or denominations in much the same way they select other consumer goods, balancing costs and rewards in a rational manner. In this framework, RCT also explains the development and decline of churches, denominations, sects, and even cults; this limited part of the very complex RCT theory is the only aspect well supported by research data.

Critics of RCT argue that it doesn’t fit well with human spiritual needs, and many sociologists disagree that the costs and rewards of religion can even be meaningfully measured or that individuals use a rational balancing process regarding religious affiliation. The theory doesn’t address many aspects of religion that individuals may consider essential (such as faith) and further fails to account for agnostics and atheists who don’t seem to have a similar need for religious explanations. Critics also believe this theory overuses economic terminology and structure and point out that terms such as “rational” and “reward” are unacceptably defined by their use; they would argue that the theory is based on faulty logic and lacks external, empirical support. A scientific explanation for why something occurs can’t reasonably be supported by the fact that it does occur. RCT is widely used in economics and to a lesser extent in criminal justice, but the application of RCT in explaining the religious beliefs and behaviors of people and societies is still being debated in sociology today.

Symbolic Interactionism

Rising from the concept that our world is socially constructed, symbolic interactionism studies the symbols and interactions of everyday life. To interactionists, beliefs and experiences are not sacred unless individuals in a society regard them as sacred. The Star of David in Judaism, the cross in Christianity, and the crescent and star in Islam are examples of sacred symbols. Interactionists are interested in what these symbols communicate. Because interactionists study one-on-one, everyday interactions between individuals, a scholar using this approach might ask questions focused on this dynamic. The interaction between religious leaders and practitioners, the role of religion in the ordinary components of everyday life, and the ways people express religious values in social interactions—all might be topics of study to an interactionist.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Introduction to Sociology 3e

- Publication date: Jun 3, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/15-1-the-sociological-approach-to-religion

© Jan 18, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

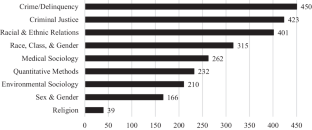

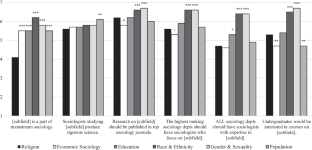

ABOUT OUR JOURNAL: SOCIOLOGY OF RELIGION

Sociology of Religion , the official journal of the Association for the Sociology of Religion, is published quarterly for the purpose of advancing scholarship in the sociological study of religion. The journal publishes original (not previously published) work of exceptional quality and interest without regard to substantive focus, theoretical orientation, or methodological approach. Although theoretically ambitious, empirically grounded articles are the core of what we publish, we also welcome agenda setting essays, comments on previously published works, critical reflections on the research act, and interventions into substantive areas or theoretical debates intended to push the field ahead.

Articles published in Sociology of Religion have won many professional awards, including most recently the ASA Religion Section’s Graduate Student Paper Award (Darwin in 2019), the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion’s Distinguished Article Award (Whitehead, Perry, and Baker in 2019), and the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion’s Graduate Student Paper Award (Rotolo 2021). Building on this legacy, Sociology of Religion aspires to be the premier English-language publication for sociological scholarship on religion and an essential source for agenda-setting work in the field.

Click HERE to visit the journal page at Oxford University Press

Sor journal submission.

ASR Members can submit articles to the journal for free. Sign into the Member Section on the Home Page to submit an article.

Non-members must pay a submission fee, to cover the cost of editorial review. (This fee is not refundable.) Go to the Home Page and scroll down the left column, then click the Pay Now button to pay your fee.

The Journal staff sponsors a podcast series highlighting recent articles. Click the image below to visit the podcast page on the Oxford University Press site.

Sociology of Religion Journal Podcasts

Click HERE to visit the Podcast Page (opens in a new tab)

- How It Works

- PhD thesis writing

- Master thesis writing

- Bachelor thesis writing

- Dissertation writing service

- Dissertation abstract writing

- Thesis proposal writing

- Thesis editing service

- Thesis proofreading service

- Thesis formatting service

- Coursework writing service

- Research paper writing service

- Architecture thesis writing

- Computer science thesis writing

- Engineering thesis writing

- History thesis writing

- MBA thesis writing

- Nursing dissertation writing

- Psychology dissertation writing

- Sociology thesis writing

- Statistics dissertation writing

- Buy dissertation online

- Write my dissertation

- Cheap thesis

- Cheap dissertation

- Custom dissertation

- Dissertation help

- Pay for thesis

- Pay for dissertation

- Senior thesis

- Write my thesis

215 Religion Research Paper Topics for College Students

Studying religion at a college or a university may be a challenging course for any student. This isn’t because religion is always a sensitive issue in society, it is because the study of religion is broad, and crafting religious topics for research papers around them may be further complex for students. This is why sociology of religion research topics and many others are here, all for your use.

As students of a university or a college, it is essential to prepare religious topics for research papers in advance. There are many research paper topics on religion, and this is why the scope of religion remains consistently broad. They extend to the sociology of religion, research paper topics on society, argumentative essay topics, and lots more. All these will be examined in this article. Rather than comb through your books in search of inspiration for your next essay or research paper, you can easily choose a topic for your religious essay or paper from the following recommendations:

World Religion Research Paper Topics

If you want to broaden your scope as a university student to topics across religions of the world, there are religion discussion topics to consider. These topics are not just for discussion in classes, you can craft research around them. Consider:

- The role of myths in shaping the world: Greek myths and their influence on the evolution of European religions

- Modern History: The attitude of modern Europe on the history of their religion

- The connection between religion and science in the medieval and modern world

- The mystery in the books of Dan Brown is nothing but fiction: discuss how mystery shapes religious beliefs

- Theocracy: an examination of theocratic states in contemporary society

- The role of Christianity in the modern world

- The myth surrounding the writing of the Bible

- The concept of religion and patriarchy: examine two religions and how it oppresses women

- People and religion in everyday life: how lifestyle and culture is influenced by religion

- The modern society and the changes in the religious view from the medieval period

- The interdependence of laws and religion is a contemporary thing: what is the role of law in religion and what is the role of religion in law?

- What marked the shift from religion to humanism?

- What do totemism and animalism denote?

- Pre Colonial religion in Africa is savagery and barbaric: discuss

- Cite three religions and express their views on the human soul

- Hinduism influenced Indian culture in ways no religion has: discuss

- Africans are more religious than Europeans who introduced Christian religion to them: discuss

- Account for the evolution of Confucianism and how it shaped Chinese culture to date

- Account for the concept of the history of evolution according to Science and according to a religion and how it influences the ideas of the religious soul

- What is religious education and how can it promote diversity or unity?7

- Workplace and religion: how religion is extended to all facets of life

- The concept of fear in maintaining religious authorities: how authorities in religious places inspire fear for absolute devotion

- Afro-American religion: a study of African religion in America

- The Bible and its role in religions

- Religion is more of emotions than logic

- Choose five religions of the world and study the similarities in their ideas

- The role of religious leaders in combating global terrorism

- Terrorism: the place of religion in promoting violence in the Middle East

- The influence of religion in modern-day politics

- What will the world be like without religion or religious extremists?

- Religion in the growth of communist Russia: how cultural revolution is synonymous with religion

- Religion in the growth of communist China: how cultural revolution is synonymous with religion

- The study of religions and ethnic rivalries in India

- Terrorism in Islam is a comeback to the crusades

- The role of the Thirty Years of War in shaping world diplomacy

- The role of the Thirty Years of War in shaping plurality in Christianity

- The religion and the promotion of economics

- The place of world religions on homosexuality

- Why does a country, the Vatican City, belong to the Catholic Church?

- God and the concept of the supernatural: examine the idea that God is a supernatural being

- The influence of religion in contemporary Japan

- Religion and populism in the modern world

- The difference between mythical creatures and gods

- Polytheism and the possibility of world peace

- Religion and violence in secular societies?

- Warfare and subjugation in the spread of religion

- The policies against migrant in Poland is targeted against Islam

- The role of international organizations in maintaining religious peace

- International terrorist organizations and the decline of order

Research Paper Topics Religion and Society

As a student in a university or MBA student, you may be requested to write an informed paper on sociology and religion. There are many sociology religion research paper topics for these segments although they may be hard to develop. You can choose out of the following topics or rephrase them to suit your research interest:

- The influence of religion on the understanding of morality

- The role of religion in marginalizing the LGBTQ community

- The role of women in religion

- Faith crisis in Christianity and Islamic religions

- The role of colonialism in the spreading of religion: the spread of Christianity and Islam is a mortal sin

- How does religion shape our sexual lifestyle?

- The concept of childhood innocence in religion

- Religion as the object of hope for the poor: how religion is used as a tool for servitude by the elite

- The impact of traditional beliefs in today’s secular societies

- How religion promotes society and how it can destroy it

- The knowledge of religion from the eyes of a sociologist

- Religious pluralism in America: how diverse religions struggle to strive

- Social stratification and its role in shaping religious groups in America

- The concept of organized religion: why the belief in God is not enough to join a religious group

- The family has the biggest influence on religious choices: examine how childhood influences the adult’s religious interests

- Islamophobia in European societies and anti-Semitism in America

- The views of Christianity on interfaith marriage

- The views of Islam on interfaith marriage

- The difference between spirituality and religion

- The role of discipline in maintaining strict religious edicts

- How do people tell others about their religion?

- The features of religion in sociology

- What are the views of Karl Marx on religion?

- What are the views of Frederic Engels on religion?

- Modern Islam: the conflict of pluralism and secularism

- Choose two religions and explore their concepts of divorce

- Governance and religion: how religion is also a tool of control

- The changes in religious ideas with technological evolution

- Theology is the study of God for God, not humans

- The most feared religion: how Islamic extremists became identified as terrorist organizations

- The role of cults in the society: why religious people still have cults affiliations

- The concept of religious inequality in the US

- What does religion say about sexual violence?

Religion Essay Topics

As a college student, you may be required to write an essay on religion or morality. You may need to access a lot of religious essay topics to find inspiration for a topic of your choice. Rather than go through the stress of compiling, you can get more information for better performance from religion topics for research paper like:

- The origin of Jihad in Islam and how it has evolved

- Compare the similarities and differences between Christian and Judaism religions

- The Thirty Years War and the Catholic church

- The Holocaust: historic aggression or a religious war

- Religion is a tool of oppression from the political and economic perspectives

- The concept of patriarchy in religion

- Baptism and synonym to ritual sacrifice

- The life of Jesus Christ and the themes of theology

- The life of Prophet Muhammad (S.A.W.) and the themes of theology

- How can religion be used to promote world peace?

- Analyze how Jesus died and the reason for his death

- Analyze the event of the birth of Christ

- The betrayal of Jesus is merely to fulfill a prophecy

- Does “prophecy” exist anywhere in religion?

- The role of war in promoting religion: how crusades and terrorist attacks shape the modern world

- The concept of Karma: is Karma real?

- Who are the major theorists in religion and what do they say?

- The connection of sociology with religion

- Why must everyone be born again according to Christians?

- What does religious tolerance mean?

- What is the benefit of religion in society?

- What do you understand about free speech and religious tolerance?

- Why did the Church separate from the state?

- The concept of guardian angels in religion

- What do Islam and Christianity say about the end of the world?

- Religion and the purpose of God for man

- The concept of conscience in morality is overrated

- Are there different sects in Christianity?

- What does Islam or Christianity say about suicide?

- What are the reasons for the Protestant Reformation?

- The role of missionaries in propagating Christianity in Africa

- The role of the Catholic church in shaping Christianity

- Do we need an international religious organization to maintain international religious peace?

- Why do people believe in miracles?

Argumentative Essay Topics on Religion

Creating argumentative essay topics on religion may be a daunting exercise regardless of your level. It is more difficult when you don’t know how to start. Your professor could be interested in your critical opinions about international issues bordering on religion, which is why you need to develop sensible topics. You can consider the following research paper topics religion and society for inspiration:

- Religion will dominate humanity: discuss

- All religions of the world dehumanize the woman

- All men are slaves to religion

- Karl Marx was right when he said religion is the return of the repressed, “the sigh of the oppressed creature”: discuss

- Christianity declined in Europe with the Thirty Years War and it separated brothers and sisters of the Christian faith?

- Islamic terrorism is a targeted attack on western culture

- The danger of teen marriage in Islam is more than its benefits

- The church should consider teen marriages for every interested teenager

- Is faith fiction or reality?

- The agape love is restricted to God and God’s love alone

- God: does he exist or is he a fiction dominating the world?

- Prayer works better without medicine: why some churches preach against the use of medicine

- People change religion because they are confused about God: discuss

- The church and the state should be together

- Polygamous marriage is evil and it should be condemned by every religion

- Cloning is abuse against God’s will

- Religious leaders should also be political leaders

- Abortion: a sin against God or control over your body

- Liberty of religious association affects you negatively: discuss

- Religious leaders only care about themselves, not the people

- Everyone should consider agnosticism

- Natural laws are the enemy of religion

- It is good to have more than two faiths in a family

- It is hard for the state to exist without religion

- Religion as a cause of the World War One

- Religion as a tool for capitalists

- Religion doesn’t promote morality, only extremisms

- Marriage: should the people or their religious leaders set the rules?

- Why the modern church should acknowledge the LGBTQ: the fight for true liberalism

- Mere coexistence is not religious tolerance

- The use of candles, incense, etc. in Catholic worship is idolatrous and the same as pagan worship: discuss

- The Christian religion is the same as Islam

Christianity Research Paper Topics on Religion

It doesn’t matter if you’re a Christian or not as you need to develop a range of topics for your essay or project. To create narrow yet all-inclusive research about Christianity in the world today, you can consider research topics online. Rather than rack your head or go through different pages on the internet, consider these:

- Compare and contrast Christian and Islam religions

- Trace the origin of Christianity and the similarity of the beliefs in the contemporary world

- Account for the violent spread of Christianity during the crusades

- Account for the state of Christianity in secular societies

- The analysis of the knowledge of rapture in Christianity

- Choose three contemporary issues and write the response of Christianity on them

- The Catholic church and its role towards the continuance of sexual violence

- The Catholic church and the issues of sexual abuse and scandals

- The history of Christianity in America

- The history of Christianity in Europe

- The impact of Christianity on American slaves

- The belief of Christianity on death, dying, and rapture

- The study of Christianity in the medieval period

- How Christianity influenced the western world

- Christianity: the symbols and their meaning

- Why catholic priests practice celibacy

- Christianity in the Reformation Era

- Discuss the Gnostic Gospels and their distinct historic influence on Christianity

- The catholic church in the Third Reich of Germany

- The difference between the Old Testament and the New Testament

- What the ten commandments say from a theological perspective

- The unpredictable story of Moses

- The revival of Saul to Paul: miracle or what?

- Are there Christian cults in the contemporary world?

- Gender differences in the Christian church: why some churches don’t allow women pastors

- The politics of the Catholic church before the separation of the church and the state

- The controversies around Christian religion and atheism: why many people are leaving the church

- What is the Holy Trinity and what is its role in the church?

- The miracles of the New Testament and its difference from the Old Testament’s

- Why do people question the existence of God?

- God is a spirit: discuss

Islam Research Paper Topics

As a student of the Islamic religion or a Muslim, you may be interested in research on the religion. Numerous Islam research paper topics could be critical in shaping your research paper or essay. These are easy yet profound research paper topics on religion Islam for your essays or papers:

- Islam in the Middle East

- Trace the origin of Islam

- Who are the most important prophets in Islam?

- Discuss the Sunni and other groups of Muslims

- The Five Pillars of Islam are said to be important in Islam, why?

- Discuss the significance of the Holy Month

- Discuss the significance of the Holy Pilgrimage

- The distinctions of the Five Pillars of Islam and the Ten Commandments?

- The controversies around the hijab and the veil

- Western states are denying Muslims: why?

- The role of religious leaders in their advocacy of sexual abuse and violence

- What the Quran says about rape and what does Hadiths say, too?

- Rape: men, not the women roaming the street should be blamed

- What is radicalism in Islam?

- The focus of Islam is to oppress women: discuss

- The political, social, and economic influence of modernity on Islam

- The notable wives of prophet Muhammad and their role in Islam: discuss

- Trace the evolution of Islam in China and the efforts of the government against them

- Religious conflict in Palestine and Israel: how a territorial conflict slowly became a religious war

- The study of social class and the Islamic religion

- Suicide bombers and their belief of honor in death: the beliefs of Islamic jihadists

- Account for the issues of marginalization of women in Muslim marriages

- The role of literature in promoting the fundamentals of Islam: how poetry was used to appeal to a wider audience

- The concept of feminism in Islam and why patriarchy seems to be on a steady rise

- The importance of Hadiths in the comprehension of the Islamic religion

- Does Islam approve of democracy?

- Islamic terrorism and the role of religious leaders

- The relationship of faith in Islam and Christianity: are there differences in the perspectives of faith?

- How the Quran can be used as a tool for religious tolerance and religious intolerance

- The study of Muslims in France: why is there religious isolation and abuse in such a society?

- Islam and western education: what are the issues that have become relevant in recent years?

- Is there a relationship between Islam and Science?

- Western culture: why there are stereotypes against Muslims abroad

- Mythology in Islam: what role does it play in shaping the religion?

- Islam and the belief in the afterlife: are there differences between its beliefs with other religions’?

- Why women are not allowed to take sermons in Islam

Can’t Figure Out Your Religion Paper?

With these religious research paper topics, you’re open to change the words or choose a topic of your choice for your research paper or essay. Writing an essay after finding a topic is relatively easy. Since you have helpful world religion research paper topics, research paper topics on religion and society, religion essay topics, argumentative essay topics on religion, Christianity research paper topics, and Islam research paper topics, you can go online to research different books that discuss the topic of your choice.

However, if you require the assistance of professional academic experts who offer custom academic help, you’ll find them online. There are a few writing help online groups that assist in writing your essays or research paper as fast as possible. You can opt for their service if you’re too busy or unmotivated to write your research paper or essay.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Comment * Error message

Name * Error message

Email * Error message

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

As Putin continues killing civilians, bombing kindergartens, and threatening WWIII, Ukraine fights for the world's peaceful future.

Ukraine Live Updates

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

IResearchNet

Academic Writing Services

Sociology of religion.

The task of building a scientific understanding of religion is a central part of the sociological enterprise. Indeed, in one sense the origins of the sociology can be attributed to the efforts of nineteenth-century Europeans to come to grips with the crisis of faith that shook Western society during the revolutionary upheavals of its industrial transformation. Most of the great European intellectuals of this era sought to formulate some sort of rational scientific paradigm to replace the religious foundations of Western culture, and such founding sociologists as Comte, Marx, and Durkheim were no exceptions.

Introduction

What is religion, durkheim and the functionalists, weber and the historical-comparative approach, the sacred canopy, the religious marketplace, the religious experience, religion and identity, conversion and commitment, religious movements, religion and social structure, religion in an age of globalization, the future of the sociology of religion.

Since the early sociologists were trying to break free from the hegemonic religious paradigm that had long dominated European thought, it is not surprising that they were fascinated with the phenomena of religion itself. As they became increasingly aware of the fecund diversity of religious life around the world, a number of basic questions arose that still lie at the heart of the quest for a sociological understanding of religion. Why are religious beliefs and practices so universal? Why do they take such diverse forms? How do social forces help shape those beliefs and practices? What role does religion, in turn, play in social, economic , and political life?

The first step in understanding religion is obviously to decide what it is, but as is so often the case, defining this basic concept is a far more difficult business than it appears at first glance. A good place to start is with Émile Durkheim. According to this classic sociologist, religion is a “unified system of beliefs and practices relative to sacred things, that is to say things set apart and forbidden—beliefs and practices which unite into one single moral community called a Church , all those who adhere to them” (Dukheim [1915] 1965:62). Although this definition clearly requires some surgery to remove its Eurocentrism, it shows remarkable insight into the fundamental sociological characteristics of religion. The most obvious change that needs to be made is to remove the word “church,” because that normally refers only to Christian religions. There are, however, some more fundamental problems especially with Durkheim’s inclusion of the concept of the sacred in his definition. While “sacred things” play a major role in most religions, they are certainly not the sine qua non of religious life. In the Buddhist view, for example, there is nothing “set apart and forbidden” about meditation, ethical behavior, the cultivation of wisdom, or the other central tenets of their beliefs and practices. On the other hand, however, it doesn’t seem justified to call any system of beliefs and practices a religion. The Christian theologian Paul Tillich’s (1967) contention that religion involves issues of “ultimate concern” is far more broadly applicable (see Kurtz 1995:8–9).

For sociological purposes, at least, we can then say that religion involves three key elements: beliefs, practices, and a social group. Although religious beliefs are not always as systematically organized as Durkheim seemed to believe, those beliefs do deal in some way or other with the questions of ultimate concern the believers face. The realm of religious practice is too vast to enumerate here, because it involves everything from rituals and ceremonies to dietary and behavioral standards and various spiritual disciplines, but it is clearly a central part of religious life. Finally, religion is a social phenomenon that involves groups of people. The solitary philosopher does not become a religious figure until one shares his or her ideas with a group of people.

Sociological Theories of Religion

Sociology starts with the rather eccentric figure of August Comte (1798–1857). Like many young intellectuals of his time, Comte believed that religion was an archaic holdover from the past. Comte held that in the course of history, theological thinking gave way to metaphysical thinking, which in turn gave way to scientific thinking or what he called “positive philosophy.” Science, then, was the replacement for religion. When applied to the systematic study of society, it could be used to construct a rational social order guided by the sociologists that would eliminate the ancient problems that plagued humanity. Ironically, this determined opponent of religion suffered a mental breakdown toward the end of his life and refused to read anything but a medieval devotional text known as The Imitation of Christ.

Marx (1818–1883) was of course far more influential than Comte, and he was the first of the sociological giants to address the issue of religion. Although he shared the idea with many nineteenth-century thinkers that religious faith was an unscientific holdover from earlier times, his economic determinism and revolutionary commitment gave his views a particular slant. Religion in his perspective was merely part of the ideological superstructure erected on and shaped by the underlying economic realities and had no kind of independence of its own. Nonetheless, religion does play an important and clearly negative social role. For Marx (1844), religion was a profound form of social alienation because

the worker is related to the product of his labor as to an alien object. . . . The more the worker expends himself in work the more powerful becomes the world of objects which he creates in face of himself, the poorer he becomes in his inner life, and the less he belongs to himself. It’s just the same as in religion. The more of himself man attributes to God the less he has left in himself. (P. 122)

Religion in capitalist society provides a comforting illusion that obscures the realities of class conflict and class interest and, thus, is a profound example of false consciousness. By consoling the frustrated and oppressed, it helps prevent collective action to change the real source of their problems. Thus, religion was, in Marx’s famous phrase, “the opiate of the masses.”

Others in the Marxist tradition have taken a more nuanced position on religion, including his benefactor Fredrich Engels. Engels recognized that religion in some circumstances actually supported the struggle of the oppressed, as he felt was the case with early Christianity (Marx and Engels 1957). Most contemporary Marxists follow Engels’s position holding a general skepticism and suspicion of religious institutions, but recognizing that some religious developments, such as liberation theology in Latin American Catholicism , can be a progressive force.

While religion was of only a passing concern to Marx, it was central to the foundational French sociologist Émile Durkheim (1858–1917). In his major work on the sociology of religion, The Elementary Forms of Religious Life, Durkheim ([1915] 1965) studied the religious life of the Australian aborigines on the questionable assumption that it was more primitive and simple than in the European nations and thus reflected religion in its most basic forms. Durkheim was particularly fascinated with the totemistic aspects of aboriginal religion. He concluded that the totems, objects or animals held in special awe by a particular clan, actually had little to do with the supernatural but were in fact symbols of the social group. He went on to argue that if the totem “is at once the symbol of the god and of the society, is that not because the god and the society are only one?” (Durkheim [1915] 1965:236). Thus, even in European society, Durkheim saw the worship of God to be nothing more than the worship of society. Society is the transcendent reality that religion symbolizes, and it not only has its own needs but even takes on a kind of anthropomorphic form in some of his writings. Society personifies itself in the form of totems or Gods to be revered and worshiped because it needs to reaffirm its legitimacy and worth to its members. And just as the Gods symbolize society, the soul is the symbol of the social element within the individual that lives on long after the people themselves.

Although the almost metaphysical elements in Durkheim’s thought were not particularly influential, his idea that religion functioned to meet basic social needs became a sociological truism. Over the years, functionalist theory grew more complex and sophisticated and is now one of the most widely used theoretical paradigms in the sociology of religion. Of particular importance was the contribution of Robert Merton (1957), who introduced the concept of the dysfunction. In his view, social institutions not only perform functions for society, but they also have dysfunctional consequences. Over the years, functionalists have developed a long list of the functions and dysfunctions of religion. Following O’Dea (1966:4–18), we can divide the human needs that religion meets into two categories—expressive and adaptive. Religion helps meet our expressive emotional needs by providing a supernatural context in which the hard realities of human life— powerlessness, uncertainty, injustice, and the inevitability of death—can be given meaning and purpose. Religion provides support and consolation, and its cult and ceremonies can encourage a sense of security and identity with something larger than the self. According to the functionalists, religion’s most important adaptive function is the way it sacralizes and reinforces the norms and values on which social order depends. Common rituals and common beliefs also help bind people together into a common community. In a different context, however, each function can become a dysfunction. By comforting and consoling people, religion may also discourage action for the needed social change. By making norms and values sacred, it not only strengthens them, but it may make them much harder to change when the times require it.

Like Durkheim, Max Weber (1864–1920) devoted a great deal of his enormous intellectual energy to the study of religion. Ever the rationalist, however, he was disinclined toward Durkheim’s kind of philosophical speculation or Marx’s political partisanship. If there is one underlying objective of Weber’s richly detailed historical and comparative examination of religion, it was to understand the relationship between religion and economic life. Where Marx saw a simple economic determinism, Weber saw a complex reciprocal interaction. In his most famous work, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, Weber (1930) argued the revolutionary thesis that Puritanism was one key factor in the Industrial Revolution. It was not, as Weber’s argument is sometimes misconstrued, just that Puritanism encouraged hard work (a strong work ethnic is certainly found in many non-European cultures). But also that Puritanism saw economic success as a sign of divine favor while demanding extreme rational self-control and a frugal lifestyle—conditions ideally suited to encourage the capital accumulation needed for the process of industrialization. Weber subsequently expanded his studies by examining the obstacles to economic rationalization posed by the religious and cultural traditions in other parts of the world, especially in China (1951) and India (1958).

Weber (1952, 1963) saw the influence of socioeconomic forces on religion in terms of what he called elective affinities. Weber felt that people in social groups with different lifestyles had an affinity for different kinds of religious beliefs. Those affinities may be based on the characteristics of entire societies, such as the tendency for foragers to believe in nature spirits or the appeal to monotheism for pastoralists. Or they may affect smaller-status groups, such as merchants who are attracted to rational calculating religions, or privileged elites with their proclivity for elaborate ritual and ceremony. However, Weber saw these relationships only as affinities, not as fixed and deterministic. Historical forces such as a foreign conquest can induce persons from a particular status group to adopt a religion for which they do not have a natural affinity.

One of the most popular of the more recent sociological theories of religion is built around Peter Berger’s (1969) metaphor of the “sacred canopy.” Drawing on the phenomenological and interactionist traditions, Berger holds human society to be an enterprise of world-building. It is, in other words, an effort to create a meaningful reality in which to live. This is a dialectical process that has three underlying movements. The first is “externalization,” which “is the ongoing outpouring of human beings into the world, both in the physical and the mental activities of man” (Berger 1969:4). Next comes the process of “objectivation,” which gives the products of this activity a reality and power that is independent of those who created it. Finally, individuals take this socially constructed reality into their own inner life in the process of “internalization.” Through this process society creates a nomos—a meaningful order that is imposed on the universe. The most important aspect of this socially established nomos is that it is “a shield against terror” protecting us from the “danger of meaninglessness” (Berger 1969:22).

Religion plays a key role in this process because it is the human enterprise by which a sacred cosmos is established. It is, in turn, the awesome mysterious power of the sacred that confronts the specter of chaos and the inevitability of death. According to Berger (1969), the “power of religions depends, in the last resort, upon the credibility of the banners it puts in the hands of men as they stand before death, or more accurately, as they walk inevitably, toward it” (p. 51).

Despite the powerful way Berger’s theory links the existential and the social dimension of religion, the idea that religion provides a single scared canopy over today’s pluralistic societies has it limitations. A number of current scholars are now using a different theoretical paradigm— rational choice theory—to construct a model that explicitly recognizes the reality of religious diversity (Stark and Bainbridge 1985; Finke and Stark 1992; Warner 1993; Iannaccone 1994). The basic idea is that the kind of consumer decision making analyzed by economic theory also applies to religious behavior. This approach looks at the public as consumers of religious who are out to satisfy their needs by obtaining the best “product.” Religious organizations are entrepreneurial establishments competing in a religious marketplace ruled by the laws of supply and demand.

Although religious “merchandise” is considered in just the same way as any other product, there is one important difference. The costs and benefits the consumers must weigh are often supernatural (such as the promise of an afterlife) and therefore cannot be empirically proven. This leaves the religious organization free to make almost any kind of claims it wishes, but it also creates the problem that the consumers are often uncertain about whether or not they will actually receive the benefits it promises. Thus, demanding groups that require high commitment often have the most attractive product, because they create greater feelings of certainty among consumers that they will actually receive the promised rewards. Another important point stressed by these theorists is that greater religious pluralism will encourage greater religiosity among the public, because it stimulates competition among different religious groups to improve their “product” in order to protect and expand their market share. Societies with a state religion, on the other hand, will tend to have less religious vitality because the established religion will be less responsive to the needs of the public (Finke and Stark 1992).

The metaphor of the marketplace is a useful tool for sociological analysis, but it can also be seriously misleading because there are also some fundamental ways in which religion is unlike an economic commodity. One of the most obvious is that the majority of people stay in the religion into which they were born and do not change even if another religion in the “marketplace” offers more benefits and less costs. Moreover, “religious products” are not really subject to market exchange, because they have no direct monetary value. A church cannot put its product on sale if the customers don’t come. Finally, as in other aspects of human life, rational choice theory fails to recognize the deep emotional forces involved in religious life that are often quite impervious to the beckonings of reason.

The Social Psychology of Religion

This examination of the theory of religion would not be complete without mentioning one other great nineteenth-century thinker, Sigmund Freud (1856–1939). His thinking contains many similarities to the more sociological-oriented theorists who have grappled with the problem of religion. Like Berger, for example, Freud saw religion as an attempt to deal with the fundamental problem of human existence. For Berger, that problem was the need for meaning, whereas for Freud, it was our inability to obtain the things we want and need. Religion in Freud’s (1957) words “is born of the need to make tolerable the helplessness of man” (p. 54). Religion helps create a world in which we feel less threatened and more at home. But like so many other social scientists of this time, Freud felt that while religion may be comforting, it is a comforting illusion. Thus, religion is a kind of infantile wish fulfillment. In the face of our helplessness and defenselessness, we crave the solace and support we received from our parents when we were children, so we project a father figure into the heavens and call it God. While more recent psychological thinkers do not necessarily share Freud’s metaphysical position, the idea that the patriarchal God of Western monotheism is a father figure and that the female Goddesses in other traditions are symbolic representations of the mother is widespread.

Because these sociological and psychological theorists focus on the roles religion plays and the needs it meets, they often lose sight of the experiential foundations of religious life. But no matter how skeptical one may be about their meaning, there is no doubt that many people have religious or mystical experiences. Indeed, most of the world’s major religions trace their origins to such events. The experience Moses had when Yahweh gave him the Ten Commandments, Mohammad’s experience as the Angel Gabriel revealed Allah’s words in the Koran, and Siddhartha Gautama’s great enlightenment experience under the Bodhi tree are just a few examples of religious experiences that have literally changed the course of human history. But how, then, is the social scientist to understand such events? Freud, Durkheim, and Marx along with many of the other founders of the sociology of religion would dismiss such experiences as hallucinations, but that hardly seems to do such momentous events justice. Believers in the various faiths founded on such visions would say their accounts of what happened are literally true, but that of course leaves the problem that the “truths” revealed in one religious tradition often contradict the “truths” of another. The inescapable fact is that fact experiences that lie completely beyond the bounds of the ordinary must be still expressed in terms of the cultural expectations, assumptions, and language of the individuals who try to report them.

In his classic study The Idea of the Holy, Rudolf Otto (1923) argues that religious experiences involve what he calls mysterium tremendum et fascinosum. That is, the experience of the holy is one of a terrifying power, fascinating yet absolutely unapproachable and wholly other. Ironically, most mystics in the Asian tradition and many Westerners as well describe such peak experiences in just the opposite way—a complete dissolution of the bounds of the normal self that produces an absolute unity with the entire universe (see Anonymous 1978; Kapleau 1989).

Of course, all religious experiences are not so overwhelming and profound. Like other experiences, they come in all ranges of intensities and in countless different forms. The feeling of holiness and tranquility one feels when entering a beautiful church or the sense of wonder and joy when seeing a mountain sunset are milder forms of religious experience, as are the states produced by effective rituals that invoke a sense of reverence and awe in the participant.

There is often a considerable difference in the importance placed on religious experience even among religious groups with relatively similar backgrounds. Among Protestant Christians, for example, the Pentacostalists give great importance to the direct emotional experience of the spirit of God, whereas the Puritans reject such emotionalism in favor of Bible studies and ethical discipline.

In societies with a single dominant faith, religious affiliation often becomes a taken-for-granted assumption and does not necessarily play a significant role in personal identity. The more religiously divided a society is, however, the more central the religion is likely to become in defining who one is. In pluralistic countries such as the United States, religious affiliation commonly provides a sense of belonging amid the anonymous institutions of mass society.

Religious identity is often mixed with ethnic identity— to be an Arab in many parts of the world is to be a Muslim, just as Serbs are identified with Orthodoxy , Croatians with Catholicism, and Thais with Buddhism . This combination can be an explosive one in areas with high levels of ethnic conflict. Religious differences aggravate ethnic conflict by providing emotionally charged symbols, systems of meaning that compete for cultural dominance, and a certain tendency to see one’s own group as having a monopoly on the truth.

Religion can play another role in personal identity by reinforcing a definition of oneself as a particular kind of person. Those with high levels of religious involvement and commitment often define themselves as more moral, more spiritual, or more wise than other people. Many religious groups hold that their faith is the one true faith, and even that fellow believers are an elite group that will receive heavenly rewards in the afterlife, whereas all others will suffer horrible torments. So the members of such groups tend to see themselves as part of a special elite of the “saved.” Although such beliefs can obviously reinforce self-esteem, they can also foster fear and anxiety if one fails to live up to the expectations of the religious group or begins to doubt the truth of its doctrines. They can also encourage a sense of hostility or even violence toward nonbelievers.

Religion may also have a critical role in sustaining identity change. In most societies, religiously rooted rites of passage publicly declare and reinforce changes in social status and the new identity that goes with them, for example, coming of age or marriage ceremonies. Religious groups may play a critical role in helping individuals make other radical changes in their lives as well. Religious organizations have often succeeded in helping drug abusers and compulsive gamblers where other programs have failed, because they offer an attractive new identity and a strong community to support it. A religious conversion or recommitment often follows various kinds of personal crises for much the same reasons.

Although there is a considerable amount of sociological research about “religious conversion,” the concept is in some ways an unfortunate one for it seems to imply an all-or-nothing dichotomy. One is a member of one religion and then “converts” to a different one. In many cases, however, a “conversion” is more like a renewal or return to existing religious beliefs. Moreover, despite the exclusivity of many Western religions, there is no particular reason to assume that people must leave their old religion before joining a new one. A substantial percentage of the population of Japan would, for example, identify themselves as both Shintoists and Buddhists.

Most of the sociological research on conversion and commitment focuses on one of two types of religions— fundamentalist Christians and members of what are called the new religious movements . The most striking finding of the research on conservative Christian faiths is that most of their “converts” actually came from the same kind of conservative Christian background. Richardson and Stewart’s (1978) study of the Jesus Movement in the 1960s and 1970s found that most of their converts were “hippies” who were returning to their original fundamentalist roots. Bibby and Brinkerhoff’s (1974) study of fundamentalist churches in a large metropolitan area in the United States also found that most converts were already religious insiders from evangelical backgrounds. Unlike the popular image of religious conversion, Zetterberg (1952) found that only 16 percent of converts to the Christian Church he studied experienced a sudden change in lifestyle. For most of his subjects, religious “conversion” was more like a “sudden role identification” in which they identified themselves more clearly in religious terms.

The media attention in the 1960s and 1970s to religious cults that appeared to be brainwashing young converts stimulated considerable sociological attention on this subject. To avoid the stigma attached to the term cult, however, sociologists now more often use the term new religious movements (NRMs) (see Roberts 2004:187–197). But somewhat confusingly, the term does not apply to any new religion only but to groups outside the religious mainstream that have an intense encapsulating community and often a strong charismatic leader. The most well-known study of conversion to NRMs is John Lofland’s work on the Unification Church of Reverend Sun Myung Moon. Lofland (1966) found that conversion to the Unification Church followed a series of stages. First, the potential convert was “picked up” by members of the group, then he or she was showered with attention and “hooked.” In the next stage, they are “encapsulated”—isolated from contacts with those outside the group—and the final result is “commitment” to the group. Lofland’s model has been criticized for giving potential converts too passive a role in the process, something he himself later recognized (Snow and Phillips 1980; Lofland and Skonovd 1981).

Like other researchers, Lofland (1966) concluded that people with high levels of emotional tension and dislocations are more prone to religious conversions. Conversion or a renewed religious commitment is, then, one possible response to intractable personal problems. Thomas O’Dea (1966) argued that religious conversion was also part of a “quest for community.” Migrants, marginalized people seen as deviants by mainstream society, and others suffering from anomie and social disorganization are therefore prime candidates for a transforming religious commitment.

Sociologists, however, often neglect the obvious point that in addition to the desire to deal with pressing personal difficulties and to be part of a supportive community, people also make religious conversions for religious reasons. That is, they seek some kind of spiritual growth or religious experience. The members of the Western Buddhist groups that Coleman (2001) surveyed ranked the desire for spiritual growth as a more important reason for getting involved in Buddhism than a desire to deal with personal problems or to be with other members of those groups. More tellingly, the average respondent reported that they began to meditate about four years before they joined a Buddhist group—obviously, not something we would expect of someone whose primary goal was to find a supportive social community.

There is probably no other sphere of human life in which more effort is made to maintain unchanging traditions than in religion. Yet religious life everywhere is in a constant state of dynamic change. Even in the most stable eras, religious beliefs and practices are undergoing continual change from generation to generation, and new religious movements often spring up unexpectedly to challenge orthodox views.

Weber traced the origins of most religious movements to charismatic leaders, who are often the bearers of radical new religious ideas. The charismatic leader, according to Weber (1947), has “a certain quality of . . . individual personality by virtue of which he is set apart from ordinary men and treated as endowed with supernatural, superhuman, or at least specifically exceptional powers or qualities” (pp. 358–59). The qualities and insights of the charismatic leader are creative, out of the ordinary, and spontaneous, and as such she or he is a major source of social change and innovation. When the charismatic leader issues a call, people follow, and things change. Thus, charismatic leaders are often seen as a threat to established religion, which may respond with various repressive measures.

In its early days, the charismatic religious movement draws its legitimacy and inspiration from its leader. But once the charismatic leader dies, the movement is thrown into crisis. If the movement is to survive, it must undergo a process Weber termed the “routinization of charisma.” The special inspiration and magical quality of the leader must be incorporated into the routine institutionalized structures of society. In literate societies, the words and actions of the leader are written down and become revered holy books. The followers who gathered around the leader are typically subsumed into a formalized religious institution with the charismatic figure’s inner circle as its leaders. Rules, rituals, and specialized roles are developed to keep the leader’s message and the religious movement going.

This process of institutionalization is essential if the movement is to survive, but ironically, it can also sap its religious vitality and even subvert the intentions of the founder. As religious institutions become more powerful and more bureaucratic, the goals of the leaders are often displaced from spiritual objectives to the maintenance and enhancement of their own positions. Rituals and practices that were once vital and alive become stale, and the enthusiasm of the original converts is replaced by the complacency of those born into the faith. As this trend continues, the religion often generates revival movements that seek to shake things up and return to the original message of its charismatic founder.

The success of a new religious movement depends on both the qualities and skill of the charismatic leader and its sociological context. The religious message of the successful movement must have a stronger affinity to the needs and aspirations of particular status groups than competing religions. Political power is often critical to the expansion of the religion, as when conquering Islamic warriors propagated their faith across North Africa and the Middle East, or when the Christian faith of the European colonialists was spread throughout the vast empires they subjugated.

The most widely used typology of religious organization is probably Weber’s church- sect dichotomy. This useful, if somewhat Eurocentric, typology has been the subject of repeated elaborations and refinements over the years. Niebuhr (1957) added a third category, the denomination , between the first two, and some add a fourth (the cult), while still others have created subcategories within each broad type (Troeltsch 1931; Yinger 1970; Stark and Bainbridge 1985). Unfortunately, as the categories proliferated and their contents were elaborated in different ways by different sociologists, the classificatory scheme has become increasingly unwieldy.

The basic idea behind Weber’s original classification is, however, still a valuable one especially when conceptualized as a continuum rather than a series of ideal types. At one end is the “church” or, less Eurocentrically, the “established religion.” It is broad and universal and its members are usually born into the faith. It is well accommodated to the established order and, indeed, often receives official state support. At the other end is the sect, which is small and exclusive. Membership in the sect is by choice, and it demands a high degree of commitment and involvement. The roots of sectarianism are usually in some kind of protest movement, and in contrast to the established religion, there is an ongoing tension between the sect and the social order. As time goes by, however, both extreme types of religious organization tend to move more toward the middle. As the original members of the sect are succeeded by later generations, it tends to accommodate itself with the dominant social order, while established religions eventually split or see their hegemony eroded by new religious competition. European Christianity, for example, started as a sect, grew into an established religion, and then fragmented into multiple denominations.

Sectarian movements are most popular among the poor and disprivileged, groups that are naturally in a greater state of tension with the established order. But there are significant class differences even within established religions. In general, lower social strata have an affinity for emotional and expressive religion, while the middle and upper middle classes prefer more self-controlled rationalistic practice, and the upper class shows an attraction to elegant ceremony. In traditional Japan, for example, devotional Pure Land Buddhism was most popular among the peasants, and the disciplined Zen sect among the samurai, while the ritualistic Shigon held special appeal to the royalty.

Religion commonly plays another important role in the stratification system by legitimizing social inequality. One classic example concerning class inequality is the Hindu belief that someone who diligently carries out the obligations of their caste will be reborn into a higher caste in the future. Religion often plays a similar role in perpetuating gender inequality. First, many religious doctrines explicitly relegate women to subordinate positions. The Koran, for example, instructs women but not men to obey their spouse, dress modestly, and limit themselves to a single marital partner. Second, religious organizations often themselves discriminate against women as a matter of official policy. In Christianity, for example, the Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and many Protestant churches categorically exclude women from the clergy. Many religions, especially in the Western tradition, also encourage or even require discrimination based on sexual orientation. However, because organized religion has often sided with the privileged and the powerful, it does not mean that it always does, and there are also numerous examples of religious movements that sought to overturn or reform an unjust social order.

The relationship between religion and politics is therefore a complex one. In some cases, religious groups are an oppositional force challenging the established order, although some form of accommodation or active support is far more common. But even in the latter case, the relationship between religion and government takes many forms. At one extreme we have the theocracy, such as contemporary Iran, in which religious elites dominate state organization. At the other extreme are the totalitarian states that rigidly control religious practice, as occurred in most of the Communist countries, or that use religion as a tool of government policy, as was the case with State Shinto in Meiji Japan. Religion offers a way to legitimize ruling elites in much the same way as it does for the overall stratification system as, for example, in the European belief in the divine right of kings. Equally important, it can provide a palate of powerful symbols that can be used to justify specific government actions. In the contemporary conflicts in the Middle East, for example, one side justifies its actions in terms of an Islam Jihad, whereas the other does the same in terms of what Bellah (1970) termed America’s “ civil religion ” (the belief that God supports America and that it has a moral duty to spread freedom and democracy around the world).

Like all social institutions, religion has undergone a sweeping transformation as a result of the Industrial Revolution and the global changes it has wrought. Many of the early founders of the sociology of religion saw this religious change in relatively simplistic terms as a process of secularization in which old religious ideas and institutions were being replaced by new rational-scientific ones. Over the years, the advocates of this secularization thesis moderated their claims holding merely that the influence of religion on society and social life has declined as a result of this process of modernization (Roberts 2004:305–28). More recently, a number of scholars have challenged this thesis holding that people are as religious as they ever were and that the process of secularization has ground to a halt (e.g., Stark and Bainbridge 1985). Such claims touched off a powerful counterattack, and this remains one of the most hotly debated issues in the sociology of religion (Bruce 1996).

Much of the differences between the contestants rest on conflicting definitions of secularization, and, polemics aside, several points seem clear. First, although the trend is more marked in the core than the periphery, societies in all parts of the world are becoming more secular if by that we mean mythical and magical thought is being replaced by rational-scientific thought in many (but certainly not all) areas of social life. The world, in Max Weber’s term, is being “disenchanted.”