- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Common Assignments: Literature Review Matrix

Literature review matrix.

As you read and evaluate your literature there are several different ways to organize your research. Courtesy of Dr. Gary Burkholder in the School of Psychology, these sample matrices are one option to help organize your articles. These documents allow you to compile details about your sources, such as the foundational theories, methodologies, and conclusions; begin to note similarities among the authors; and retrieve citation information for easy insertion within a document.

You can review the sample matrixes to see a completed form or download the blank matrix for your own use.

- Literature Review Matrix 1 This PDF file provides a sample literature review matrix.

- Literature Review Matrix 2 This PDF file provides a sample literature review matrix.

- Literature Review Matrix Template (Word)

- Literature Review Matrix Template (Excel)

Related Resources

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Commentary Versus Opinion

- Next Page: Professional Development Plans (PDPs)

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

- Generating Ideas

- Drafting and Revision

- Sources and Evidence

- Style and Grammar

- Specific to Creative Arts

- Specific to Humanities

- Specific to Sciences

- Specific to Social Sciences

- CVs, Résumés and Cover Letters

- Graduate School Applications

- Other Resources

- Hiatt Career Center

- University Writing Center

- Classroom Materials

- Course and Assignment Design

- UWP Instructor Resources

- Writing Intensive Requirement

- Criteria and Learning Goals

- Course Application for Instructors

- What to Know about UWS

- Teaching Resources for WI

- FAQ for Instructors

- FAQ for Students

- Journals on Writing Research and Pedagogy

- University Writing Program

- Degree Programs

- Graduate Programs

- Brandeis Online

- Summer Programs

- Undergraduate Admissions

- Graduate Admissions

- Financial Aid

- Summer School

- Centers and Institutes

- Funding Resources

- Housing/Community Living

- Clubs and Organizations

- Community Service

- Brandeis Arts Engagement

- Rose Art Museum

- Our Jewish Roots

- Mission and Diversity Statements

- Administration

- Faculty & Staff

- Alumni & Friends

- Parents & Families

- 75th Anniversary

- Campus Calendar

- Directories

- New Students

- Shuttle Schedules

- Support at Brandeis

Writing Resources

The matrix method for literature reviews.

This handout is available for download in DOCX format and PDF format .

What is the Matrix Method, and why should I use it?

Using a review matrix enables you to quickly compare and contrast articles in order to determine the scope of research across time. A review matrix can help you more easily spot differences and similarities between journal articles about a research topic. While they may be helpful in any discipline, review matrices are especially helpful for health sciences literature reviews covering the complete scope of a research topic over time. This guide focuses on the review matrix step in the literature review process and offers tips on how to use it effectively.

Organize your sources

Once you complete your research, organize your source by date in order to make it easier to see changes in research over time.

Begin by creating the blank matrix. The matrices can be easily constructed using table-making software such as Microsoft Excel, Word or OneNote, Google Sheets, or Numbers. Every review matrix should have the same first three column headings: (1) authors, title, and journal, (2) publication year, and (3) purpose.

Be aware that it may be difficult to determine purpose from just a cursory review of the article. In some cases, it may be necessary to first read the paper fully to identify its purpose.

Choose your remaining column topics

Next, carefully read all your articles. Note any important issues you identify. The following broad categories provide some suggestions for determining your own subject headings:

Methodological

Methodology is often an important question. For example, if you are looking at tests of an Ebola vaccine beyond human subjects, it will be important to note what type of animal the test was carried out on, i.e. macaques or mice.

Content-specific

Consider noting what was actually studied. For example, when looking at the effectiveness of traditional Chinese medicine in the treatment of illnesses, it would be important to note what illness was being studied.

Geographical

It may be important to note where the research was completed. For example, if you want to compare the effects of the AIDS epidemic in different countries, you would use country as a column heading.

There are many ways to choose your column headings, and these are just a few suggestions. As you create your own matrix, choose column headings that support your research question and goals.

- Do not include column headings that are explicit in your research question. For example, if you are looking at drug use in adolescents, do not include a column heading for age of study participants. If the answer will be the same for every study, it's generally a bad choice for a column heading.

- Do not try to fully complete a review matrix before reading the articles. Reading the articles is an important way to discern the nuances between studies.

Credit: Adapted from David Nolfi, “Matrix Method for Literature Review: The Review Matrix,” Duquesne University, https://guides.library.duq.edu/matrix , 2020.

- Resources for Students

- Writing Intensive Instructor Resources

- Research and Pedagogy

Chapter 9. Reviewing the Literature

What is a “literature review”.

No researcher ever comes up with a research question that is wholly novel. Someone, somewhere, has asked the same thing. Academic research is part of a larger community of researchers, and it is your responsibility, as a member of this community, to acknowledge others who have asked similar questions and to put your particular research into this greater context. It is not simply a convention or custom to begin your study with a review of previous literature (the “ lit review ”) but an important responsibility you owe the scholarly community.

Too often, new researchers pursue a topic to study and then write something like, “No one has ever studied this before” or “This area is underresearched.” It may be that no one has studied this particular group or setting, but it is highly unlikely no one has studied the foundational phenomenon of interest. And that comment about an area being underresearched? Be careful. The statement may simply signal to others that you haven’t done your homework. Rubin ( 2021 ) refers to this as “free soloing,” and it is not appreciated in academic work:

The truth of the matter is, academics don’t really like when people free solo. It’s really bad form to omit talking about the other people who are doing or have done research in your area. Partly, I mean we need to cite their work, but I also mean we need to respond to it—agree or disagree, clarify for extend. It’s also really bad form to talk about your research in a way that does not make it understandable to other academics.…You have to explain to your readers what your story is really about in terms they care about . This means using certain terminology, referencing debates in the literature, and citing relevant works—that is, in connecting your work to something else. ( 51–52 )

A literature review is a comprehensive summary of previous research on a topic. It includes both articles and books—and in some cases reports—relevant to a particular area of research. Ideally, one’s research question follows from the reading of what has already been produced. For example, you are interested in studying sports injuries related to female gymnasts. You read everything you can find on sports injuries related to female gymnasts, and you begin to get a sense of what questions remain open. You find that there is a lot of research on how coaches manage sports injuries and much about cultures of silence around treating injuries, but you don’t know what the gymnasts themselves are thinking about these issues. You look specifically for studies about this and find several, which then pushes you to narrow the question further. Your literature review then provides the road map of how you came to your very specific question, and it puts your study in the context of studies of sports injuries. What you eventually find can “speak to” all the related questions as well as your particular one.

In practice, the process is often a bit messier. Many researchers, and not simply those starting out, begin with a particular question and have a clear idea of who they want to study and where they want to conduct their study but don’t really know much about other studies at all. Although backward, we need to recognize this is pretty common. Telling students to “find literature” after the fact can seem like a purposeless task or just another hurdle for completing a thesis or dissertation. It is not! Even if you were not motivated by the literature in the first place, acknowledging similar studies and connecting your own research to those studies are important parts of building knowledge. Acknowledgment of past research is a responsibility you owe the discipline to which you belong.

Literature reviews can also signal theoretical approaches and particular concepts that you will incorporate into your own study. For example, let us say you are doing a study of how people find their first jobs after college, and you want to use the concept of social capital . There are competing definitions of social capital out there (e.g., Bourdieu vs. Burt vs. Putnam). Bourdieu’s notion is of one form of capital, or durable asset, of a “network of more or less institutionalized relationships of mutual acquaintance or recognition” ( 1984:248 ). Burt emphasizes the “brokerage opportunities” in a social network as social capital ( 1997:355 ). Putnam’s social capital is all about “facilitating coordination and cooperation for mutual benefit” ( 2001:67 ). Your literature review can adjudicate among these three approaches, or it can simply refer to the one that is animating your own research. If you include Bourdieu in your literature review, readers will know “what kind” of social capital you are talking about as well as what kind of social scientist you yourself are. They will likely understand that you are interested more in how some people are advantaged by their social capital relative to others rather than being interested in the mechanics of how social networks operate.

The literature review thus does two important things for you: firstly, it allows you to acknowledge previous research in your area of interest, thereby situating you within a discipline or body of scholars, and, secondly, it demonstrates that you know what you are talking about. If you present the findings of your research study without including a literature review, it can be like singing into the wind. It sounds nice, but no one really hears it, or if they do catch snippets, they don’t know where it is coming from.

Examples of Literature Reviews

To help you get a grasp of what a good literature review looks like and how it can advance your study, let’s take a look at a few examples.

Reader-Friendly Example: The Power of Peers

The first is by Janice McCabe ( 2016 ) and is from an article on peer networks in the journal Contexts . Contexts presents articles in a relatively reader-friendly format, with the goal of reaching a large audience for interesting sociological research. Read this example carefully and note how easily McCabe is able to convey the relevance of her own work by situating it in the context of previous studies:

Scholars who study education have long acknowledged the importance of peers for students’ well-being and academic achievement. For example, in 1961, James Coleman argued that peer culture within high schools shapes students’ social and academic aspirations and successes. More recently, Judith Rich Harris has drawn on research in a range of areas—from sociological studies of preschool children to primatologists’ studies of chimpanzees and criminologists’ studies of neighborhoods—to argue that peers matter much more than parents in how children “turn out.” Researchers have explored students’ social lives in rich detail, as in Murray Milner’s book about high school students, Freaks, Geeks, and Cool Kids , and Elizabeth Armstrong and Laura Hamilton’s look at college students, Paying for the Party . These works consistently show that peers play a very important role in most students’ lives. They tend, however, to prioritize social over academic influence and to use a fuzzy conception of peers rather than focusing directly on friends—the relationships that should matter most for student success. Social scientists have also studied the power of peers through network analysis, which is based on uncovering the web of connections between people. Network analysis involves visually mapping networks and mathematically comparing their structures (such as the density of ties) and the positions of individuals within them (such as how central a given person is within the network). As Nicholas Christakis and James Fowler point out in their book Connected , network structure influences a range of outcomes, including health, happiness, wealth, weight, and emotions. Given that sociologists have long considered network explanations for social phenomena, it’s surprising that we know little about how college students’ friends impact their experiences. In line with this network tradition, I focus on the structure of friendship networks, constructing network maps so that the differences we see across participants are due to the underlying structure, including each participant’s centrality in their friendship group and the density of ties among their friends. ( 23 )

What did you notice? In her very second sentence, McCabe uses “for example” to introduce a study by Coleman, thereby indicating that she is not going to tell you every single study in this area but is going to tell you that (1) there is a lot of research in this area, (2) it has been going on since at least 1961, and (3) it is still relevant (i.e., recent studies are still being done now). She ends her first paragraph by summarizing the body of literature in this area (after giving you a few examples) and then telling you what may have been (so far) left out of this research. In the second paragraph, she shifts to a separate interesting focus that is related to the first but is also quite distinct. Lit reviews very often include two (or three) distinct strands of literature, the combination of which nicely backgrounds this particular study . In the case of our female gymnast study (above), those two strands might be (1) cultures of silence around sports injuries and (2) the importance of coaches. McCabe concludes her short and sweet literature review with one sentence explaining how she is drawing from both strands of the literature she has succinctly presented for her particular study. This example should show you that literature reviews can be readable, helpful, and powerful additions to your final presentation.

Authoritative Academic Journal Example: Working Class Students’ College Expectations

The second example is more typical of academic journal writing. It is an article published in the British Journal of Sociology of Education by Wolfgang Lehmann ( 2009 ):

Although this increase in post-secondary enrolment and the push for university is evident across gender, race, ethnicity, and social class categories, access to university in Canada continues to be significantly constrained for those from lower socio-economic backgrounds (Finnie, Lascelles, and Sweetman 2005). Rising tuition fees coupled with an overestimation of the cost and an underestimation of the benefits of higher education has put university out of reach for many young people from low-income families (Usher 2005). Financial constraints aside, empirical studies in Canada have shown that the most important predictor of university access is parental educational attainment. Having at least one parent with a university degree significantly increases the likelihood of a young person to attend academic-track courses in high school, have high educational and career aspirations, and ultimately attend university (Andres et al. 1999, 2000; Lehmann 2007a). Drawing on Bourdieu’s various writing on habitus and class-based dispositions (see, for example, Bourdieu 1977, 1990), Hodkinson and Sparkes (1997) explain career decisions as neither determined nor completely rational. Instead, they are based on personal experiences (e.g., through employment or other exposure to occupations) and advice from others. Furthermore, they argue that we have to understand these decisions as pragmatic, rather than rational. They are pragmatic in that they are based on incomplete and filtered information, because of the social context in which the information is obtained and processed. New experiences and information can, however, also be allowed into one’s world, where they gradually or radically transform habitus, which in turn creates the possibility for the formation of new and different dispositions. Encountering a supportive teacher in elementary or secondary school, having ambitious friends, or chance encounters can spark such transformations. Transformations can be confirming or contradictory, they can be evolutionary or dislocating. Working-class students who enter university most certainly encounter such potentially transformative situations. Granfield (1991) has shown how initially dislocating feelings of inadequacy and inferiority of working-class students at an elite US law school were eventually replaced by an evolutionary transformation, in which the students came to dress, speak and act more like their middle-class and upper-class peers. In contrast, Lehmann (2007b) showed how persistent habitus dislocation led working-class university students to drop out of university. Foskett and Hemsley-Brown (1999) argue that young people’s perceptions of careers are a complex mix of their own experiences, images conveyed through adults, and derived images conveyed by the media. Media images of careers, perhaps, are even more important for working-class youth with high ambitions as they offer (generally distorted) windows into a world of professional employment to which they have few other sources of access. It has also been argued that working-class youth who do continue to university still face unique, class-specific challenges, evident in higher levels of uncertainty (Baxter and Britton 2001; Lehmann 2004, 2007a; Quinn 2004), their higher education choices (Ball et al. 2002; Brooks 2003; Reay et al. 2001) and fears of inadequacy because of their cultural outsider status (Aries and Seider 2005; Granfield 1991). Although the number of working-class university students in Canada has slowly increased, that of middle-class students at university has risen far more steeply (Knighton and Mizra 2002). These different enrolment trajectories have actually widened the participation gap, which in tum explains our continued concerns with the potential outsider status Indeed, in a study comparing first-generation working-class and traditional students who left university without graduating, Lehmann (2007b) found that first-generation working-class students were more likely to leave university very early in some cases within the first two months of enrollment. They were also more likely to leave university despite solid academic performance. Not “fitting in,” not “feeling university,” and not being able to “relate to these people” were key reasons for eventually withdrawing from university. From the preceding review of the literature, a number of key research questions arise: How do working-class university students frame their decision to attend university? How do they defy the considerable odds documented in the literature to attend university? What are the sources of information and various images that create dispositions to study at university? What role does their social-class background- or habitus play in their transition dispositions and how does this translate into expectations for university? ( 139 )

What did you notice here? How is this different from (and similar to) the first example? Note that rather than provide you with one or two illustrative examples of similar types of research, Lehmann provides abundant source citations throughout. He includes theory and concepts too. Like McCabe, Lehmann is weaving through multiple literature strands: the class gap in higher education participation in Canada, class-based dispositions, and obstacles facing working-class college students. Note how he concludes the literature review by placing his research questions in context.

Find other articles of interest and read their literature reviews carefully. I’ve included two more for you at the end of this chapter . As you learned how to diagram a sentence in elementary school (hopefully!), try diagramming the literature reviews. What are the “different strands” of research being discussed? How does the author connect these strands to their own research questions? Where is theory in the lit review, and how is it incorporated (e.g., Is it a separate strand of its own or is it inextricably linked with previous research in this area)?

One model of how to structure your literature review can be found in table 9.1. More tips, hints, and practices will be discussed later in the chapter.

Table 9.1. Model of Literature Review, Adopted from Calarco (2020:166)

| What we know about some issue | Lays the foundation for your |

| What we don't know about that issue | Lays foundation for your |

| Why that unanswered question is important to ask | Hints at of your study |

| What existing research tells us about the best way to answer that unanswered question | Lays foundation for justifying your |

| What existing research might predict as the answer to the question | Justifies your "hypothesis" or |

Embracing Theory

A good research study will, in some form or another, use theory. Depending on your particular study (and possibly the preferences of the members of your committee), theory may be built into your literature review. Or it may form its own section in your research proposal/design (e.g., “literature review” followed by “theoretical framework”). In my own experience, I see a lot of graduate students grappling with the requirement to “include theory” in their research proposals. Things get a little squiggly here because there are different ways of incorporating theory into a study (Are you testing a theory? Are you generating a theory?), and based on these differences, your literature review proper may include works that describe, explain, and otherwise set forth theories, concepts, or frameworks you are interested in, or it may not do this at all. Sometimes a literature review sets forth what we know about a particular group or culture totally independent of what kinds of theoretical framework or particular concepts you want to explore. Indeed, the big point of your study might be to bring together a body of work with a theory that has never been applied to it previously. All this is to say that there is no one correct way to approach the use of theory and the writing about theory in your research proposal.

Students are often scared of embracing theory because they do not exactly understand what it is. Sometimes, it seems like an arbitrary requirement. You’re interested in a topic; maybe you’ve even done some research in the area and you have findings you want to report. And then a committee member reads over what you have and asks, “So what?” This question is a good clue that you are missing theory, the part that connects what you have done to what other researchers have done and are doing. You might stumble upon this rather accidentally and not know you are embracing theory, as in a case where you seek to replicate a prior study under new circumstances and end up finding that a particular correlation between behaviors only happens when mediated by something else. There’s theory in there, if you can pull it out and articulate it. Or it might be that you are motivated to do more research on racial microaggressions because you want to document their frequency in a particular setting, taking for granted the kind of critical race theoretical framework that has done the hard work of defining and conceptualizing “microaggressions” in the first place. In that case, your literature review could be a review of Critical Race Theory, specifically related to this one important concept. That’s the way to bring your study into a broader conversation while also acknowledging (and honoring) the hard work that has preceded you.

Rubin ( 2021 ) classifies ways of incorporating theory into case study research into four categories, each of which might be discussed somewhat differently in a literature review or theoretical framework section. The first, the least theoretical, is where you set out to study a “configurative idiographic case” ( 70 ) This is where you set out to describe a particular case, leaving yourself pretty much open to whatever you find. You are not expecting anything based on previous literature. This is actually pretty weak as far as research design goes, but it is probably the default for novice researchers. Your committee members should probably help you situate this in previous literature in some way or another. If they cannot, and it really does appear you are looking at something fairly new that no one else has bothered to research before, and you really are completely open to discovery, you might try using a Grounded Theory approach, which is a methodological approach that foregrounds the generation of theory. In that case, your “theory” section can be a discussion of “Grounded Theory” methodology (confusing, yes, but if you take some time to ponder, you will see how this works). You will still need a literature review, though. Ideally one that describes other studies that have ever looked at anything remotely like what you are looking at—parallel cases that have been researched.

The second approach is the “disciplined configurative case,” in which theory is applied to explain a particular case or topic. You are not trying to test the theory but rather assuming the theory is correct, as in the case of exploring microaggressions in a particular setting. In this case, you really do need to have a separate theory section in addition to the literature review, one in which you clearly define the theoretical framework, including any of its important concepts. You can use this section to discuss how other researchers have used the concepts and note any discrepancies in definitions or operationalization of those concepts. This way you will be sure to design your study so that it speaks to and with other researchers. If everyone who is writing about microaggressions has a different definition of them, it is hard for others to compare findings or make any judgments about their prevalence (or any number of other important characteristics). Your literature review section may then stand alone and describe previous research in the particular area or setting, irrespective of the kinds of theory underlying those studies.

The third approach is “heuristic,” one in which you seek to identify new variables, hypotheses, mechanisms, or paths not yet explained by a theory or theoretical framework. In a way, you are generating new theory, but it is probably more accurate to say that you are extending or deepening preexisting theory. In this case, having a single literature review that is focused on the theory and the ways the theory has been applied and understood (with all its various mechanisms and pathways) is probably your best option. The focus of the literature reviewed is less on the case and more on the theory you are seeking to extend.

The final approach is “theory testing,” which is much rarer in qualitative studies than in quantitative, where this is the default approach. Theory-testing cases are those where a particular case is used to see if an existing theory is accurate or accurate under particular circumstances. As with the heuristic approach, your literature review will probably draw heavily on previous uses of the theory, but you may end up having a special section specifically about cases very close to your own . In other words, the more your study approaches theory testing, the more likely there is to be a set of similar studies to draw on or even one important key study that you are setting your own study up in parallel to in order to find out if the theory generated there operates here.

If we wanted to get very technical, it might be useful to distinguish theoretical frameworks properly from conceptual frameworks. The latter are a bit looser and, given the nature of qualitative research, often fit exploratory studies. Theoretical frameworks rely on specific theories and are essential for theory-testing studies. Conceptual frameworks can pull in specific concepts or ideas that may or may not be linked to particular theories. Think about it this way: A theory is a story of how the world works. Concepts don’t presume to explain the whole world but instead are ways to approach phenomena to help make sense of them. Microaggressions are concepts that are linked to Critical Race Theory. One could contextualize one’s study within Critical Race Theory and then draw various concepts, such as that of microaggressions from the overall theoretical framework. Or one could bracket out the master theory or framework and employ the concept of microaggression more opportunistically as a phenomenon of interest. If you are unsure of what theory you are using, you might want to frame a more practical conceptual framework in your review of the literature.

Helpful Tips

How to maintain good notes for what your read.

Over the years, I have developed various ways of organizing notes on what I read. At first, I used a single sheet of full-size paper with a preprinted list of questions and points clearly addressed on the front side, leaving the second side for more reflective comments and free-form musings about what I read, why it mattered, and how it might be useful for my research. Later, I developed a system in which I use a single 4″ × 6″ note card for each book I read. I try only to use the front side (and write very small), leaving the back for comments that are about not just this reading but things to do or examine or consider based on the reading. These notes often mean nothing to anyone else picking up the card, but they make sense to me. I encourage you to find an organizing system that works for you. Then when you set out to compose a literature review, instead of staring at five to ten books or a dozen articles, you will have ten neatly printed pages or notecards or files that have distilled what is important to know about your reading.

It is also a good idea to store this data digitally, perhaps through a reference manager. I use RefWorks, but I also recommend EndNote or any other system that allows you to search institutional databases. Your campus library will probably provide access to one of these or another system. Most systems will allow you to export references from another manager if and when you decide to move to another system. Reference managers allow you to sort through all your literature by descriptor, author, year, and so on. Even so, I personally like to have the ability to manually sort through my index cards, recategorizing things I have read as I go. I use RefWorks to keep a record of what I have read, with proper citations, so I can create bibliographies more easily, and I do add in a few “notes” there, but the bulk of my notes are kept in longhand.

What kinds of information should you include from your reading? Here are some bulleted suggestions from Calarco ( 2020:113–114 ), with my own emendations:

- Citation . If you are using a reference manager, you can import the citation and then, when you are ready to create a bibliography, you can use a provided menu of citation styles, which saves a lot of time. If you’ve originally formatted in Chicago Style but the journal you are writing for wants APA style, you can change your entire bibliography in less than a minute. When using a notecard for a book, I include author, title, date as well as the library call number (since most of what I read I pull from the library). This is something RefWorks is not able to do, and it helps when I categorize.

I begin each notecard with an “intro” section, where I record the aims, goals, and general point of the book/article as explained in the introductory sections (which might be the preface, the acknowledgments, or the first two chapters). I then draw a bold line underneath this part of the notecard. Everything after that should be chapter specific. Included in this intro section are things such as the following, recommended by Calarco ( 2020 ):

- Key background . “Two to three short bullet points identifying the theory/prior research on which the authors are building and defining key terms.”

- Data/methods . “One or two short bullet points with information about the source of the data and the method of analysis, with a note if this is a novel or particularly effective example of that method.” I use [M] to signal methodology on my notecard, which might read, “[M] Int[erview]s (n-35), B[lack]/W[hite] voters” (I need shorthand to fit on my notecard!).

- Research question . “Stated as briefly as possible.” I always provide page numbers so I can go back and see exactly how this was stated (sometimes, in qualitative research, there are multiple research questions, and they cannot be stated simply).

- Argument/contributions . “Two to three short bullet points briefly describing the authors’ answer to the central research question and its implication for research, theory, and practice.” I use [ARG] for argument to signify the argument, and I make sure this is prominently visible on my notecard. I also provide page numbers here.

For me, all of this fits in the “intro” section, which, if this is a theoretically rich, methodologically sound book, might take up a third or even half of the front page of my notecard. Beneath the bold underline, I report specific findings or particulars of the book as they emerge chapter by chapter. Calarco’s ( 2020 ) next step is the following:

- Key findings . “Three to four short bullet points identifying key patterns in the data that support the authors’ argument.”

All that remains is writing down thoughts that occur upon finishing the article/book. I use the back of the notecard for these kinds of notes. Often, they reach out to other things I have read (e.g., “Robinson reminds me of Crusoe here in that both are looking at the effects of social isolation, but I think Robinson makes a stronger argument”). Calarco ( 2020 ) concludes similarly with the following:

- Unanswered questions . “Two to three short bullet points that identify key limitations of the research and/or questions the research did not answer that could be answered in future research.”

As I mentioned, when I first began taking notes like this, I preprinted pages with prompts for “research question,” “argument,” and so on. This was a great way to remind myself to look for these things in particular. You can do the same, adding whatever preprinted sections make sense to you, given what you are studying and the important aspects of your discipline. The other nice thing about the preprinted forms is that it keeps your writing to a minimum—you cannot write more than the allotted space, even if you might want to, preventing your notes from spiraling out of control. This can be helpful when we are new to a subject and everything seems worth recording!

After years of discipline, I have finally settled on my notecard approach. I have thousands of notecards, organized in several index card filing boxes stacked in my office. On the top right of each card is a note of the month/day I finished reading the item. I can remind myself what I read in the summer of 2010 if the need or desire ever arose to do so…those invaluable notecards are like a memento of what my brain has been up to!

Where to Start Looking for Literature

Your university library should provide access to one of several searchable databases for academic books and articles. My own preference is JSTOR, a service of ITHAKA, a not-for-profit organization that works to advance and preserve knowledge and to improve teaching and learning through the use of digital technologies. JSTOR allows you to search by several keywords and to narrow your search by type of material (articles or books). For many disciplines, the “literature” of the literature review is expected to be peer-reviewed “articles,” but some disciplines will also value books and book chapters. JSTOR is particularly useful for article searching. You can submit several keywords and see what is returned, and you can also narrow your search by a particular journal or discipline. If your discipline has one or two key journals (e.g., the American Journal of Sociology and the American Sociological Review are key for sociology), you might want to go directly to those journals’ websites and search for your topic area. There is an art to when to cast your net widely and when to refine your search, and you may have to tack back and forth to ensure that you are getting all that is relevant but not getting bogged down in all studies that might have some marginal relevance.

Some articles will carry more weight than others, and you can use applications like Google Scholar to see which articles have made and are continuing to make larger impacts on your discipline. Find these articles and read them carefully; use their literature review and the sources cited in those articles to make sure you are capturing what is relevant. This is actually a really good way of finding relevant books—only the most impactful will make it into the citations of journals. Over time, you will notice that a handful of articles (or books) are cited so often that when you see, say, Armstrong and Hamilton ( 2015 ), you know exactly what book this is without looking at the full cite. This is when you know you are in the conversation.

You might also approach a professor whose work is broadly in the area of your interest and ask them to recommend one or two “important” foundational articles or books. You can then use the references cited in those recommendations to build up your literature. Just be careful: some older professors’ knowledge of the literature (and I reluctantly add myself here) may be a bit outdated! It is best that the article or book whose references and sources you use to build your body of literature be relatively current.

Keep a List of Your Keywords

When using searchable databases, it is a good idea to keep a list of all the keywords you use as you go along so that (1) you do not needlessly duplicate your efforts and (2) you can more easily adjust your search as you get a better sense of what you are looking for. I suggest you keep a separate file or even a small notebook for this and you date your search efforts.

Here’s an example:

Table 9.2. Keep a List of Your Keywords

| JSTOR search: “literature review” + “qualitative research” limited to “after 1/1/2000” and “articles” in abstracts only | 5 results: go back and search titles? Change up keywords? Take out qualitative research term? | |

| JSTOR search: “literature review” + and “articles” in abstracts only | 37,113 results – way too many!!!! |

Think Laterally

How to find the various strands of literature to combine? Don’t get stuck on finding the exact same research topic you think you are interested in. In the female gymnast example, I recommended that my student consider looking for studies of ballerinas, who also suffer sports injuries and around whom there is a similar culture of silence. It turned out that there was in fact research about my student’s particular questions, just not about the subjects she was interested in. You might do something similar. Don’t get stuck looking for too direct literature but think about the broader phenomenon of interest or analogous cases.

Read Outside the Canon

Some scholars’ work gets cited by everyone all the time. To some extent, this is a very good thing, as it helps establish the discipline. For example, there are a lot of “Bourdieu scholars” out there (myself included) who draw ideas, concepts, and quoted passages from Bourdieu. This makes us recognizable to one another and is a way of sharing a common language (e.g., where “cultural capital” has a particular meaning to those versed in Bourdieusian theory). There are empirical studies that get cited over and over again because they are excellent studies but also because there is an “echo chamber effect” going on, where knowing to cite this study marks you as part of the club, in the know, and so on. But here’s the problem with this: there are hundreds if not thousands of excellent studies out there that fail to get appreciated because they are crowded out by the canon. Sometimes this happens because they are published in “lower-ranked” journals and are never read by a lot of scholars who don’t have time to read anything other than the “big three” in their field. Other times this happens because the author falls outside of the dominant social networks in the field and thus is unmentored and fails to get noticed by those who publish a lot in those highly ranked and visible spaces. Scholars who fall outside the dominant social networks and who publish outside of the top-ranked journals are in no way less insightful than their peers, and their studies may be just as rigorous and relevant to your work, so it is important for you to take some time to read outside the canon. Due to how a person’s race, gender, and class operate in the academy, there is also a matter of social justice and ethical responsibility involved here: “When you focus on the most-cited research, you’re more likely to miss relevant research by women and especially women of color, whose research tends to be under-cited in most fields. You’re also more likely to miss new research, research by junior scholars, and research in other disciplines that could inform your work. Essentially, it is important to read and cite responsibly, which means checking that you’re not just reading and citing the same white men and the same old studies that everyone has cited before you” ( Calarco 2020:112 ).

Consider Multiple Uses for Literature

Throughout this chapter, I’ve referred to the literature of interest in a rather abstract way, as what is relevant to your study. But there are many different ways previous research can be relevant to your study. The most basic use of the literature is the “findings”—for example, “So-and-so found that Canadian working-class students were concerned about ‘fitting in’ to the culture of college, and I am going to look at a similar question here in the US.” But the literature may be of interest not for its findings but theoretically—for example, employing concepts that you want to employ in your own study. Bourdieu’s definition of social capital may have emerged in a study of French professors, but it can still be relevant in a study of, say, how parents make choices about what preschools to send their kids to (also a good example of lateral thinking!).

If you are engaged in some novel methodological form of data collection or analysis, you might look for previous literature that has attempted that. I would not recommend this for undergraduate research projects, but for graduate students who are considering “breaking the mold,” find out if anyone has been there before you. Even if their study has absolutely nothing else in common with yours, it is important to acknowledge that previous work.

Describing Gaps in the Literature

First, be careful! Although it is common to explain how your research adds to, builds upon, and fills in gaps in the previous research (see all four literature review examples in this chapter for this), there is a fine line between describing the gaps and misrepresenting previous literature by failing to conduct a thorough review of the literature. A little humility can make a big difference in your presentation. Instead of “This is the first study that has looked at how firefighters juggle childcare during forest fire season,” say, “I use the previous literature on how working parents juggling childcare and the previous ethnographic studies of firefighters to explore how firefighters juggle childcare during forest fire season.” You can even add, “To my knowledge, no one has conducted an ethnographic study in this specific area, although what we have learned from X about childcare and from Y about firefighters would lead us to expect Z here.” Read more literature review sections to see how others have described the “gaps” they are filling.

Use Concept Mapping

Concept mapping is a helpful tool for getting your thoughts in order and is particularly helpful when thinking about the “literature” foundational to your particular study. Concept maps are also known as mind maps, which is a delightful way to think about them. Your brain is probably abuzz with competing ideas in the early stages of your research design. Write/draw them on paper, and then try to categorize and move the pieces around into “clusters” that make sense to you. Going back to the gymnasts example, my student might have begun by jotting down random words of interest: gymnasts * sports * coaches * female gymnasts * stress * injury * don’t complain * women in sports * bad coaching * anxiety/stress * careers in sports * pain. She could then have begun clustering these into relational categories (bad coaching, don’t complain culture) and simple “event” categories (injury, stress). This might have led her to think about reviewing literature in these two separate aspects and then literature that put them together. There is no correct way to draw a concept map, as they are wonderfully specific to your mind. There are many examples you can find online.

Ask Yourself, “How Is This Sociology (or Political Science or Public Policy, Etc.)?”

Rubin ( 2021:82 ) offers this suggestion instead of asking yourself the “So what?” question to get you thinking about what bridges there are between your study and the body of research in your particular discipline. This is particularly helpful for thinking about theory. Rubin further suggests that if you are really stumped, ask yourself, “What is the really big question that all [fill in your discipline here] care about?” For sociology, it might be “inequality,” which would then help you think about theories of inequality that might be helpful in framing your study on whatever it is you are studying—OnlyFans? Childcare during COVID? Aging in America? I can think of some interesting ways to frame questions about inequality for any of those topics. You can further narrow it by focusing on particular aspects of inequality (Gender oppression? Racial exclusion? Heteronormativity?). If your discipline is public policy, the big questions there might be, How does policy get enacted, and what makes a policy effective? You can then take whatever your particular policy interest is—tax reform, student debt relief, cap-and-trade regulations—and apply those big questions. Doing so would give you a handle on what is otherwise an intolerably vague subject (e.g., What about student debt relief?).

Sometimes finding you are in new territory means you’ve hit the jackpot, and sometimes it means you’ve traveled out of bounds for your discipline. The jackpot scenario is wonderful. You are doing truly innovative research that is combining multiple literatures or is addressing a new or under-examined phenomenon of interest, and your research has the potential to be groundbreaking. Congrats! But that’s really hard to do, and it might be more likely that you’ve traveled out of bounds, by which I mean, you are no longer in your discipline . It might be that no one has written about this thing—at least within your field— because no one in your field actually cares about this topic . ( Rubin 2021:83 ; emphases added)

Don’t Treat This as a Chore

Don’t treat the literature review as a chore that has to be completed, but see it for what it really is—you are building connections to other researchers out there. You want to represent your discipline or area of study fairly and adequately. Demonstrate humility and your knowledge of previous research. Be part of the conversation.

Supplement: Two More Literature Review Examples

Elites by harvey ( 2011 ).

In the last two decades, there has been a small but growing literature on elites. In part, this has been a result of the resurgence of ethnographic research such as interviews, focus groups, case studies, and participant observation but also because scholars have become increasingly interested in understanding the perspectives and behaviors of leaders in business, politics, and society as a whole. Yet until recently, our understanding of some of the methodological challenges of researching elites has lagged behind our rush to interview them.

There is no clear-cut definition of the term elite, and given its broad understanding across the social sciences, scholars have tended to adopt different approaches. Zuckerman (1972) uses the term ultraelites to describe individuals who hold a significant amount of power within a group that is already considered elite. She argues, for example, that US senators constitute part of the country’s political elite but that among them are the ultraelites: a “subset of particularly powerful or prestigious influentials” (160). She suggests that there is a hierarchy of status within elite groups. McDowell (1998) analyses a broader group of “professional elites” who are employees working at different levels for merchant and investment banks in London. She classifies this group as elite because they are “highly skilled, professionally competent, and class-specific” (2135). Parry (1998:2148) uses the term hybrid elites in the context of the international trade of genetic material because she argues that critical knowledge exists not in traditional institutions “but rather as increasingly informal, hybridised, spatially fragmented, and hence largely ‘invisible,’ networks of elite actors.” Given the undertheorization of the term elite, Smith (2006) recognizes why scholars have shaped their definitions to match their respondents . However, she is rightly critical of the underlying assumption that those who hold professional positions necessarily exert as much influence as initially perceived. Indeed, job titles can entirely misrepresent the role of workers and therefore are by no means an indicator of elite status (Harvey 2010).

Many scholars have used the term elite in a relational sense, defining them either in terms of their social position compared to the researcher or compared to the average person in society (Stephens 2007). The problem with this definition is there is no guarantee that an elite subject will necessarily translate this power and authority in an interview setting. Indeed, Smith (2006) found that on the few occasions she experienced respondents wanting to exert their authority over her, it was not from elites but from relatively less senior workers. Furthermore, although business and political elites often receive extensive media training, they are often scrutinized by television and radio journalists and therefore can also feel threatened in an interview, particularly in contexts that are less straightforward to prepare for such as academic interviews. On several occasions, for instance, I have been asked by elite respondents or their personal assistants what they need to prepare for before the interview, which suggests that they consider the interview as some form of challenge or justification for what they do.

In many cases, it is not necessarily the figureheads or leaders of organizations and institutions who have the greatest claim to elite status but those who hold important social networks, social capital, and strategic positions within social structures because they are better able to exert influence (Burt 1992; Parry 1998; Smith 2005; Woods 1998). An elite status can also change, with people both gaining and losing theirs over time. In addition, it is geographically specific, with people holding elite status in some but not all locations. In short, it is clear that the term elite can mean many things in different contexts, which explains the range of definitions. The purpose here is not to critique these other definitions but rather to highlight the variety of perspectives.

When referring to my research, I define elites as those who occupy senior-management- and board-level positions within organizations. This is a similar scope of definition to Zuckerman’s (1972) but focuses on a level immediately below her ultraelite subjects. My definition is narrower than McDowell’s (1998) because it is clear in the context of my research that these people have significant decision-making influence within and outside of the firm and therefore present a unique challenge to interview. I deliberately use the term elite more broadly when drawing on examples from the theoretical literature in order to compare my experiences with those who have researched similar groups.

”Changing Dispositions among the Upwardly Mobile” by Curl, Lareau, and Wu ( 2018 )

There is growing interest in the role of cultural practices in undergirding the social stratification system. For example, Lamont et al. (2014) critically assess the preoccupation with economic dimensions of social stratification and call for more developed cultural models of the transmission of inequality. The importance of cultural factors in the maintenance of social inequality has also received empirical attention from some younger scholars, including Calarco (2011, 2014) and Streib (2015). Yet questions remain regarding the degree to which economic position is tied to cultural sensibilities and the ways in which these cultural sensibilities are imprinted on the self or are subject to change. Although habitus is a core concept in Bourdieu’s theory of social reproduction, there is limited empirical attention to the precise areas of the habitus that can be subject to change during upward mobility as well as the ramifications of these changes for family life.

In Bourdieu’s (1984) highly influential work on the importance of class-based cultural dispositions, habitus is defined as a “durable system of dispositions” created in childhood. The habitus provides a “matrix of perceptions” that seems natural while also structuring future actions and pathways. In many of his writings, Bourdieu emphasized the durability of cultural tastes and dispositions and did not consider empirically whether these dispositions might be changed or altered throughout one’s life (Swartz 1997). His theoretical work does permit the possibility of upward mobility and transformation, however, through the ability of the habitus to “improvise” or “change” due to “new experiences” (Friedman 2016:131). Researchers have differed in opinion on the durability of the habitus and its ability to change (King 2000). Based on marital conflict in cross-class marriages, for instance, Streib (2015) argues that cultural dispositions of individuals raised in working-class families are deeply embedded and largely unchanging. In a somewhat different vein, Horvat and Davis (2011:152) argue that young adults enrolled in an alternative educational program undergo important shifts in their self-perception, such as “self-esteem” and their “ability to accomplish something of value.” Others argue there is variability in the degree to which habitus changes dependent on life experience and personality (Christodoulou and Spyridakis 2016). Recently, additional studies have investigated the habitus as it intersects with lifestyle through the lens of meaning making (Ambrasat et al. 2016). There is, therefore, ample discussion of class-based cultural practices in self-perception (Horvat and Davis 2011), lifestyle (Ambrasat et al. 2016), and other forms of taste (Andrews 2012; Bourdieu 1984), yet researchers have not sufficiently delineated which aspects of the habitus might change through upward mobility or which specific dimensions of life prompt moments of class-based conflict.

Bourdieu (1999:511; 2004) acknowledged simmering tensions between the durable aspects of habitus and those aspects that have been transformed—that is, a “fractured” or “cleft” habitus. Others have explored these tensions as a “divided” or “fragmented” habitus (Baxter and Britton 2001; Lee and Kramer 2013). Each of these conceptions of the habitus implies that changes in cultural dispositions are possible but come with costs. Exploration of the specific aspects of one’s habitus that can change and generate conflict contributes to this literature.

Scholars have also studied the costs associated with academic success for working-class undergraduates (Hurst 2010; Lee and Kramer 2013; London 1989; Reay 2017; Rondini 2016; Stuber 2011), but we know little about the lasting effects on adults. For instance, Lee and Kramer (2013) point to cross-class tensions as family and friends criticize upwardly mobile individuals for their newly acquired cultural dispositions. Documenting the tension many working-class students experience with their friends and families of origin, they find that the source of their pain or struggle is “shaped not only by their interactions with non-mobile family and friends but also within their own minds, by their own assessments of their social positions, and by how those positions are interpreted by others” (Lee and Kramer 2013:29). Hurst (2010) also explores the experiences of undergraduates who have been academically successful and the costs associated with that success. She finds that decisions about “class allegiance and identity” are required aspects of what it means to “becom[e] educated” (4) and that working-class students deal with these cultural changes differently. Jack (2014, 2016) also argues that there is diversity among lower-income students, which yields varied college experiences. Naming two groups, the “doubly disadvantaged” and the “privileged poor,” he argues that previous experience with “elite environments” (2014:456) prior to college informs students’ ability to take on dominant cultural practices, particularly around engagement, such as help seeking or meeting with professors (2016). These studies shed light on the role college might play as a “lever for mobility” (2016:15) and discuss the pain and difficulty associated with upward mobility among undergraduates, but the studies do not illuminate how these tensions unfold in adulthood. Neither have they sufficiently addressed potential enduring tensions with extended family members as well as the specific nature of the difficulties.

Some scholars point to the positive outcomes upwardly mobile youth (Lehmann 2009) and adults (Stuber 2005) experience when they maintain a different habitus than their newly acquired class position, although, as Jack (2014, 2016) shows, those experiences may vary depending on one’s experience with elite environments in their youth. Researchers have not sufficiently explored the specific aspects of the habitus that upwardly mobile adults change or the conflicts that emerge with family and childhood friends as they reach adulthood and experience colliding social worlds. We contribute to this scholarship with clear examples of self-reported changes to one’s cultural dispositions in three specific areas: “horizons,” food and health, and communication. We link these changes to enduring tension with family members, friends, and colleagues and explore varied responses to this tension based on race.

Further Readings

Bloomberg, Linda Dale, and Marie F. Volpe. 2012. Completing Your Qualitative Dissertation: A Road Map from Beginning to End . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. In keeping with its general approach to qualitative research, includes a “road map” for conducting a literature review.

Hart, Chris. 1998. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . London: SAGE. A how-to book dedicated entirely to conducting a literature review from a British perspective. Useful for both undergraduate and graduate students.

Machi, Lawrence A., and Brenda T. McEvoy. 2022. The Literature Review: Six Steps to Success . 4th ed. Newbury Park, CA: Corwin. A well-organized guidebook complete with reflection sections to prompt successful thinking about your literature review.

Ridley, Diana. 2008. The Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students . London: SAGE. A highly recommended companion to conducting a literature review for doctoral-level students.

The process of systematically searching through pre-existing studies (“literature”) on the subject of research; also, the section of a presentation in which the pre-existing literature is discussed.

Follow-up questions used in a semi-structured interview to elicit further elaboration. Suggested prompts can be included in the interview guide to be used/deployed depending on how the initial question was answered or if the topic of the prompt does not emerge spontaneously.

A tool for identifying relationships among ideas by visually representing them on paper. Most concept maps depict ideas as boxes or circles (also called nodes), which are structured hierarchically and connected with lines or arrows (also called arcs). These lines are labeled with linking words and phrases to help explain the connections between concepts. Also known as mind mapping.

The people who are the subjects of an interview-based qualitative study. In general, they are also known as the participants, and for purposes of IRBs they are often referred to as the human subjects of the research.

Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods Copyright © 2023 by Allison Hurst is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

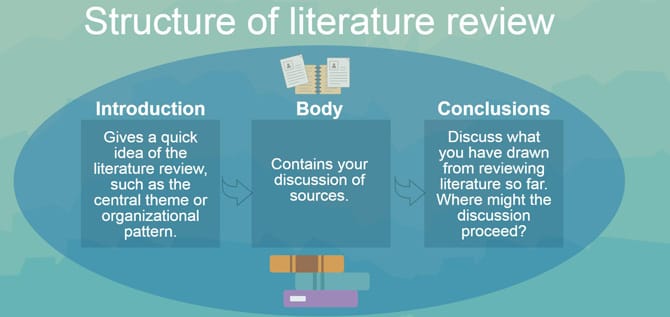

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved July 2, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".