Search form

- Table of Contents

- Troubleshooting Guide

- A Model for Getting Started

- Justice Action Toolkit

- Best Change Processes

- Databases of Best Practices

- Online Courses

- Ask an Advisor

- Subscribe to eNewsletter

- Community Stories

- YouTube Channel

- About the Tool Box

- How to Use the Tool Box

- Privacy Statement

- Workstation/Check Box Sign-In

- Online Training Courses

- Capacity Building Training

- Training Curriculum - Order Now

- Community Check Box Evaluation System

- Build Your Toolbox

- Facilitation of Community Processes

- Community Health Assessment and Planning

- Section 2. Developing Facilitation Skills

Chapter 16 Sections

- Section 1. Conducting Effective Meetings

- Section 3. Capturing What People Say: Tips for Recording a Meeting

- Section 4. Techniques for Leading Group Discussions

- Main Section

What are facilitation skills?

Community organizations are geared towards action. There are urgent problems and issues we need to tackle and solve in our communities. That's why we came together in the first place, isn't it? But for groups to be really successful, we need to spend some time focusing on the skills our members and leaders use to make all of this action happen, both within and outside our organizations.

One of the most important sets of skills for leaders and members are facilitation skills. These are the "process" skills we use to guide and direct key parts of our organizing work with groups of people such as meetings, planning sessions, and training of our members and leaders.

Whether it's a meeting (big or small) or a training session, someone has to shape and guide the process of working together so that you meet your goals and accomplish what you've set out to do. While a group of people might set the agenda and figure out the goals, one person needs to concentrate on how you are going to move through your agenda and meet those goals effectively. This is the person we call the "facilitator."

So, how is facilitating different than chairing a meeting?

Well, it is and it isn't. Facilitation has three basic principles:

- A facilitator is a guide to help people move through a process together, not the seat of wisdom and knowledge. That means a facilitator isn't there to give opinions, but to draw out opinions and ideas of the group members.

- Facilitation focuses on how people participate in the process of learning or planning, not just on what gets achieved

- A facilitator is neutral and never takes sides

The best meeting chairs see themselves as facilitators. While they have to get through an agenda and make sure that important issues are discussed, decisions made, and actions taken, good chairs don't feel that they have all of the answers or should talk all the time. The most important thing is what the participants in the meeting have to say. So, focus on how the meeting is structured and run to make sure that everyone can participate. This includes things like:

- Making sure everyone feels comfortable participating

- Developing a structure that allows for everyone's ideas to be heard

- Making members feel good about their contribution to the meeting

- Making sure the group feels that the ideas and decisions are theirs, not just the leader's.

- Supporting everyone's ideas and not criticizing anyone for what they've said.

Why do you need facilitation skills?

If you want to do good planning, keep members involved, and create real leadership opportunities in your organization and skills in your members, you need facilitator skills. The more you know about how to shape and run a good learning and planning process, the more your members will feel empowered about their own ideas and participation, stay invested in your organization, take on responsibility and ownership, and the better your meetings will be.

How do you facilitate?

Meetings are a big part of our organizing life. We seem to always be going from one meeting to the next. Other parts of the Tool Box cover planning and having good meetings in depth. But here, we're going to work on the process skills that good meeting leaders need to have. Remember, these facilitation skills are useful beyond meetings: for planning; for "growing" new leaders; for resolving conflicts; and for keeping good communication in your organization.

Can anyone learn to facilitate a meeting?

Yes, to a degree. Being a good facilitator is both a skill and an art. It is a skill in that people can learn certain techniques and can improve their ability with practice. It is an art in that some people just have more of a knack for it than others. Sometimes organization leaders are required to facilitate meetings: thus, board presidents must be trained in how to facilitate. But other meetings and planning sessions don't require that any one person act as facilitators, so your organization can draw on members who have the skill and the talent.

To put it another way, facilitating actually means:

- Understanding the goals of the meeting and the organization

- Keeping the group on the agenda and moving forward

- Involving everyone in the meeting, including drawing out the quiet participants and controlling the domineering ones

- Making sure that decisions are made democratically

How do you plan a good facilitation process?

A good facilitator is concerned with both the outcome of the meeting or planning session, with how the people in the meeting participate and interact, and also with the process. While achieving the goals and outcomes that everyone wants is of course important, a facilitator also wants to make sure that the process is sound, that everyone is engaged, and that the experience is the best it can be for the participants.

In planning a good meeting process, a facilitator focuses on:

- Climate and environment

- Logistics and room arrangements

- Ground rules

A good facilitator will make plans in each of these areas in advance. Let's look at some of the specifics.

Climate and Environment

There are many factors that impact how safe and comfortable people feel about interacting with each other and participating. The environment and general "climate" of a meeting or planning session sets an important tone for participation.

Key questions you would ask yourself as a facilitator include:

- Is the location a familiar place, one where people feel comfortable? Face it, if you're planning to have an interactive meeting sitting around a conference table in the Mayor's office, some of your folks might feel intimidated and out of their environment. A comfortable and familiar location is key.

- Is the meeting site accessible to everyone? If not, have you provided for transportation or escorts to help people get to the site? Psychologically, if people feel that the site is too far from them or in a place they feel is "dangerous," it may put them off from even coming. If they do come, they may arrive with a feeling that they were not really wanted or that their needs were not really considered. This can put a real damper on communication and participation. Another reminder: can people with disabilities access the site as well? Ensure the meeting site is accessible to all.

- Is the space the right size? Too large? Too small? If you're wanting to make a planning group feel that it's a team, a large meeting hall for only 10 or 15 people can feel intimidating and make people feel self-conscious and quiet. On the other hand, if you're taking a group of 30 folks through a meeting, a small conference room where people are uncomfortably crunched together can make for disruption: folks shifting in their seats, getting up to stretch and get some air. This can cause a real break in the mood and feeling of your meeting or planning session. You want folks to stay focused and relaxed. Be sure to choose a room size that matches the size of your group.

Logistics and Room Arrangements

Believe it or not: how people sit, whether they are hungry and whether they can hear can make or break your planning process. As a facilitator, the logistics of the meeting should be of great concern to you, whether you're responsible for them or not. Some things to consider are:

- Chair arrangements: Having chairs in a circle or around a table encourages discussion, equality, and familiarity. Speaker's podiums and lecture style seating make people feel intimidated and formal. Avoid them at all costs.

- Places to hang newsprint: You may be using a lot of newsprint or other board space during your meeting. Can you use tape without damaging the walls? Is an easel available? Is there enough space so that you can keep important material visible instead of removing it?

- Sign-In sheet: Is there a table for folks to use? Would it be helpful to provide nametags?

- Refreshments: Grumbling stomachs will definitely take folks' minds off the meeting. If you're having refreshments, who is bringing them? Do you need outlets for coffee pots? Can you set things up so folks can get food without disrupting the meeting? And who's cleaning up afterwards?

- Microphones and audio-visual equipment: Do you need a microphone? Video cameras? Be sure to have someone set up and test the equipment before you start.

To build a safe as well as comfortable environment, a good facilitator has a few more points to consider. How do you protect folks who are worried their ideas will be attacked or mocked? How do you hold back the big talkers who tend to dominate while still making them feel good about their participation? Much of the answer lies in the Ground Rules.

Ground Rules

Most meetings have some kind of operating rules. Some groups use Robert's Rules of Order (parliamentary procedure) to run their meetings while others have rules they've adopted over time. When you want the participation to flow and for folks to really feel invested in following the rules, the best way to go is to have the group develop them as one of the first steps in the process. This builds a sense of power in the participants ("Hey, she isn't telling us how to act. It's up to us to figure out what we think is important!") and a much greater sense of investment in following the rules. Common ground rules are:

- One person speaks at a time

- Raise your hand if you have something to say

- Listen to what other people are saying

- No mocking or attacking other people's ideas

- Be on time coming back from breaks (if it's a long meeting)

- Respect each other

A process to develop ground rules is:

- Begin by telling folks that you want to set up some ground rules that everyone will follow as we go through our meeting. Put a blank sheet of newsprint on the wall with the heading "Ground Rules."

- Ask for any suggestions from the group. If no one says anything, start by putting one up yourself. That usually starts people off.

- Write any suggestions up on the newsprint. It's usually most effective to "check -in" with the whole group before you write up an idea ("Sue suggested raising our hands if we have something to say. Is that okay with everyone?") Once you have gotten 5 or 6 good rules up, check to see if anyone else has other suggestions.

- When you are finished, check in with the group to be sure they agree with these Ground Rules and are willing to follow them.

Facilitating a meeting or planning session

The facilitator is responsible for providing a "safe" climate and working atmosphere for the meeting. But you're probably wondering, "What do I actually do during the meeting to guide the process along?" Here are the basic steps that can be your facilitator's guide:

Start the meeting on time

Few of us start our meetings on time. The result? Those who come on time feel cheated that they rushed to get there! When latecomers straggle in, don't stop your process to acknowledge them. Wait until after a break or another appropriate time to have them introduce themselves.

Welcome everyone

Make a point to welcome everyone who comes. Don't complain about the size of a group if the turnout is small! Nothing will turn the folks off who did come out faster. Thank all of those who are there for coming and analyze the turnout attendance later. Go with who you have.

Make introductions

There are lots of ways for people to introduce themselves to each other that are better than just going around the room. The kinds of introductions you do should depend on what kind of meeting you are having, the number of people, the overall goals of the meeting, and what kind of information it would be useful to know. Some key questions you can ask members to include in their introductions are:

- How did you first get involved with our organization? (if most people are already involved, but the participants don't know each other well)

- What do you want to know about our organization? (if the meeting is set to introduce your organization to another organization)

- What makes you most angry about this problem? (if the meeting is called to focus on a particular problem)

Sometimes, we combine introductions with something called an "ice breaker." Ice breakers can:

- Break down feelings of unfamiliarity and shyness

- Help people shift roles--from their "work" selves to their "more human" selves

- Build a sense of being part of a team

- Create networking opportunities

- Help share participants' skills and experiences

Some ways to do introductions and icebreakers are:

- In pairs, have people turn to the person next to them and share their name, organization and three other facts about themselves that others might not know. Then, have each pair introduce each other to the group. This helps to get strangers acquainted and for people to feel safe--they already know at least one other person, and didn't have to share information directly in front of a big group at the beginning of the meeting.

- Form small groups and have each of them work on a puzzle. Have them introduce themselves to their group before they get to work. This helps to build a sense of team work.

- In a large group, have everyone write down two true statements about themselves and one false one. Then, every person reads their statements and the whole group has to guess which one is false. This helps folks get acquainted and relaxed.

- Give each participant a survey and have the participants interview each other to find the answers. Make the questions about skills, experience, opinions on the issue you'll be working on, etc. When everyone is finished, have folks share the answers they got.

When doing introductions and icebreakers, it's important to remember:

- Every participant needs to take part in the activity. The only exception may be latecomers who arrive after the introductions are completed. At the first possible moment, ask the latecomers to say their name and any other information you feel they need to share in order for everyone to feel comfortable and equal.

- Be sensitive to the culture, age, gender and literacy levels of participants and any other factors when deciding how to do introductions. For example, an activity that requires physical contact or reading a lengthy instruction sheet may be inappropriate for your group. Also, keep in mind what you want to accomplish with the activity. Don't make a decision to do something only because it seems like fun.

- It is important to make everyone feel welcome and listened to at the beginning of the meeting. Otherwise, participants may feel uncomfortable and unappreciated and won't participate well later on. Also, if you don't get some basic information about who is there, you may miss some golden opportunities. For example, the editor of the regional newspaper may be in the room; but if you don't know, you'll miss the opportunity for a potential interview or special coverage.

- And don't forget to introduce yourself. You want to make sure that you establish some credibility to be facilitating the meeting and that folks know a bit about you. Credibility doesn't mean you have a college degree or 15 years of facilitation experience. It just means that you share some of your background so folks know why you are doing the facilitation and what has led you to be speaking up.

Review the agenda, objectives and ground rules for the meeting

Go over what's going to happen in the meeting. Check with the group to make sure they agree with and like the agenda. You never know if someone will want to comment and suggest something a little different. This builds a sense of ownership of the meeting and lets people know early on that you're there to facilitate their process and their meeting, not your own agenda.

The same is true for the outcomes of the meeting. You'll want to go over these with folks as well to get their input and check that these are the desired outcomes they're looking for. This is also where the ground rules that we covered earlier come in.

Encourage participation

This is one of your main jobs as a facilitator. It's up to you to get those who need to listen to listen and those who ought to speak. Encourage people to share their experiences and ideas and urge those with relevant background information share it at appropriate times.

Stick to the agenda

Groups have a tendency to wander far from the original agenda, sometimes without knowing it. When you hear the discussion wandering off, bring it to the group's attention. You can say "That's an interesting issue, but perhaps we should get back to the original discussion."

Avoid detailed decision-making

Sometimes, it's easier for groups to discuss the color of napkins than the real issues they are facing. Help the group not to get immersed in details. Suggest instead, "Perhaps the committee could resolve the matter." Do you really want to be involved in that level of detail?

Seek commitments

Getting commitments for future involvement is often a meeting goal. You want leaders to commit to certain tasks, people to volunteer to help on a campaign, or organizations to support your group. Make sure adequate time is allocated for seeking commitment. For small meetings, write people's names down on newsprint next to the tasks they agreed to undertake.

One important rule of thumb is that no one should leave a meeting without something to do. Don't ever close a meeting by saying "We'll get back to you to confirm how you might like to get involved." Seize the moment! Sign them up!

Bring closure to each item

Many groups will discuss things ten times longer than they need to unless a facilitator helps them to recognize they're basically in agreement. Summarize a consensus position, or ask someone in the group to summarize the points of agreement, and then move forward. If one or two people disagree, state the situation as clearly as you can: "Tom and Levonia seem to have other feelings on this matter, but everyone else seems to go in this direction. Perhaps we can decide to go in the direction that most of the group wants, and maybe Tom and Levonia can get back to us on other ways to accommodate their concerns." You may even suggest taking a break so Tom and Levonia can caucus to come up with some options.

Some groups feel strongly about reaching consensus on issues before moving ahead. If your group is one of them, be sure to read a good manual or book on consensus decision making. Many groups, however, find that voting is a fine way to make decisions. A good rule of thumb is that a vote must pass by a two-thirds majority for it to be a valid decision. For most groups to work well, they should seek consensus where possible, but take votes when needed in order to move the process forward.

Respect everyone's rights

The facilitator protects the shy and quiet folks in a meeting and encourages them to speak out. There is also the important job of keeping domineering people from monopolizing the meeting or ridiculing the ideas of others.

Sometimes, people dominate a discussion because they are really passionate about an issue and have lots of things to say. One way to channel their interest is to suggest that they consider serving on a committee or task force on that issue. Other people, however, talk to hear themselves talk. If someone like that shows up at your meeting, look further ahead in this chapter for some tips on dealing with "disrupters."

Be flexible

Sometimes issues will arise in the meeting that are so important, they will take much more time than you thought. Sometimes, nobody will have thought of them at all. You may run over time or have to alter your agenda to discuss them. Be sure to check with group about whether this is O.K. before going ahead with the revised agenda. If necessary, ask for a five-minute break to confer with key leaders or participants on how to handle the issue and how to restructure the agenda. Be prepared to recommend an alternate agenda, dropping some items if necessary.

Summarize the meeting results and needed follow-ups

Before ending the meeting, summarize the key decisions that were made and what else happened. Be sure also to summarize the follow-up actions that were agreed to and need to take place. Remind folks how much good work was done and how effective the meeting hopefully was. Refer back to the objectives or outcomes to show how much you accomplished.

Thank the participants

Take a minute to thank people who prepared things for the meeting, set up the room, brought refreshments, or did any work towards making the meeting happen. Thank all of the participants for their input and energy and for making the meeting a success.

Close the meeting

People appreciate nothing more than a meeting that ends on time! It's usually a good idea to have some "closure" in a meeting, especially if it was long, if there were any sticky situations that caused tension, or if folks worked especially hard to come to decisions or make plans.

A nice way to close a meeting is to go around the room and have people say one word that describes how they are feeling now that all of this work has been done. You'll usually get answers from "exhausted" to "energized!" If it's been a good meeting, even the "exhausted" ones will stick around before leaving.

Facilitator skills and tips

Here are a few more points to remember that will help to maximize your role as a facilitator:

Don't memorize a script

Even with a well-prepared agenda and key points you must make, you need to be flexible and natural. If people sense that you are reading memorized lines, they will feel like they are being talked down to, and won't respond freely.

Watch the group's body language

Are people shifting in their seats? Are they bored? Tired? Looking confused? If folks seem restless or in a haze, you may need to take a break, or speed up or slow down the pace of the meeting. And if you see confused looks on too many faces, you may need to stop and check in with the group, to make sure that everyone knows where you are in the agenda and that the group is with you.

Always check back with the group

Be careful about deciding where the meeting should go. Check back after each major part of the process to see if there are questions and that everyone understands and agrees with decisions that were made.

Summarize and pause

When you finish a point or a part of the meeting process, sum up what was done and decided, and pause for questions and comments before moving on. Learn to "feel out" how long to pause -- too short, and people don't really have time to ask questions; too long, and folks will start to get uncomfortable from the silence.

Be aware of your own behavior

Take a break to calm down if you feel nervous or are losing control. Watch that you're not repeating yourself, saying "ah" between each word, or speaking too fast. Watch your voice and physical manner. (Are you standing too close to folks so they feel intimidated, making eye contact so people feel engaged?) How you act makes an impact on how participants feel.

Occupy your hands

Hold onto a marker, chalk, or the back of a chair. Don't play with the change in your pocket!

Watch your speech

Be careful you are not offending or alienating anyone in the group. Use swear words at your own risk!

Use body language of our own

Using body language to control the dynamics in the room can be a great tool. Moving up close to a shy, quiet participant and asking them to speak may make them feel more willing, because they can look at you instead of the big group and feel less intimidated. Also, walking around engages people in the process. Don't just stand in front of the room for the entire meeting.

Don't talk to the newsprint, blackboard or walls--they can't talk back!

Always wait until you have stopped writing and are facing the group to talk.

Dealing with disrupters: Preventions and interventions

Along with these tips on facilitation, there are some things you can do both to prevent disruption before it occurs to stop it when it's happening in the meeting. The most common kinds of disrupters are people who try to dominate, keep going off the agenda, have side conversations with the person sitting next to them, or folks who think they are right and ridicule and attack other's ideas.

Preventions. Try using these "Preventions" when you set up your meeting to try to rule out disruption:

Get agreement on the agenda, ground rules and outcomes. In other words, agree on the process. These process agreements create a sense of shared accountability and ownership of the meeting, joint responsibility for how the meeting is run, and group investment in whether the outcomes and goals are achieved.

Listen carefully. Don't just pretend to listen to what someone in the meeting is saying. People can tell. Listen closely to understand a point someone is making. And check back if you are summarizing, always asking the person if you understood their idea correctly.

Show respect for experience. We can't say it enough. Encourage folks to share strategies, stories from the field, and lessons they've learned. Value the experience and wisdom in the room.

Find out the group's expectations. Make sure that you uncover at the start what participants think they are meeting for. When you find out, be clear about what will and won't be covered in this meeting. Make plans for how to cover issues that won't be dealt with: Write them down on newsprint and agree to deal with them at the end of the meeting, or have the group agree on a follow-up meeting to cover unfinished issues.

There are lots of ways to find out what the group's expectations of the meeting are: Try asking everyone to finish this sentence: "I want to leave here today knowing...." You don't want people sitting through the meeting feeling angry that they're in the wrong place and no one bothered to ask them what they wanted to achieve here. These folks may act out their frustration during the meeting and become your biggest disrupters.

Stay in your facilitator role. You cannot be an effective facilitator and a participant at the same time. When you cross the line, you risk alienating participants, causing resentment, and losing control of the meeting. Offer strategies, resources, and ideas for the group to work with, but not opinions.

Don't be defensive. If you are attacked or criticized, take a "mental step" backwards before responding. Once you become defensive, you risk losing the group's respect and trust, and might cause folks to feel they can't be honest with you.

"Buy-in" power players. These folks can turn your meeting into a nightmare if they don't feel that their influence and role are acknowledged and respected. If possible, give them acknowledgment up front at the start of the meeting. Try giving them roles to play during the meeting such as a "sounding board" for you at breaks, to check in with about how the meeting is going.

Interventions. Try using these "Interventions" when disruption is happening during the meeting:

- First try to remind them about the agreed-on agenda. If that doesn't work, throw it back to the group and ask them how they feel about that person's participation. Let the group support you.

- Go back to that agenda and those ground rules and remind folks of the agreements made at the beginning of the meeting.

- It's better to say what's going on than try to cover it up. Everyone will be aware of the dynamic in the room. The group will get behind you if you are honest and up -front about the situation.

- Try a humorous comment or a joke. If it's self-deprecating, so much the better. Humor almost always lightens the mood. It's one of the best tension-relievers we have.

- Try one or more of these approaches : Show that you understand their issue by making it clear that you hear how important it is to them. Legitimize the issue by saying, "It's a very important point and one I'm sure we all feel is critical." Make a bargain to deal with their issue for a short period of time ("O.K., let's deal with your issue for 5 minutes and then we ought to move on.") If that doesn't work, agree to defer the issue to the end of the meeting, or set up a committee to explore it further.

- Use body language. Move closer to conversers, or to the quiet ones. Make eye contact with them to get their attention and covey your intent.

- In case you've tried all of the above suggestions and nothing has worked, it's time to take a break, invite the disruptive person outside the room and politely but firmly state your feelings about how disruptive their behavior is to the group. Make it clear that the disruption needs to end. But also try to find out what's going on, and see if there are other ways to address that person's concerns.

- Confront the disruptive person politely but very firmly in the room. Tell the person very explicitly that the disruption needs to stop now. Use body language to encourage other group members to support you. This is absolutely the last resort when action must be taken and no alternatives remain!

Online Resources

Facilitating Political Discussions from the Institute for Democracy and Higher Education at Tufts University is designed to assist experienced facilitators in training others to facilitate politically charged conversations. The materials are broken down into "modules" and facilitation trainers can use some or all of them to suit their needs.

Inclusive Facilitation for Social Change from FSG provides assistance in facilitating inclusive meetings to create effective and empowering experiences for everyone involved.

Making Meetings Work from the Collective Impact Forum is a blog post from Paul Schmitz discussing lessons we can apply to ensure that meetings are purposeful, engaging, and advance our work in ways that people anticipate with enthusiasm instead of dread.

Print Resources

Auvine, B., Dinsmore, B., Extrom, M., Poole, S., & Shanklin, M. (1978). A manual for group facilitators . Madison, WI: The Center for Conflict Resolution.

Bobo, K., Kendall, J., & Max, S., (1991). A manual for activists in the 1990s . Cabin John, MD: Seven Locks Press.

Nelson-Jones, R. (1992). Group leadership: A training approach . Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Schwarz, R. (1994). The skilled facilitator: Practical wisdom for developing effective groups . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

How to Facilitate Creative Problem Solving Workshops

Posted in Blog , Create , Facilitation , Innovation , Virtual Facilitation by Jo North

This article gives you a comprehensive guide to creative problem solving, what it is and a brief history. It also covers how creative problem solving works, with a step-by-step guide to show you how to solve challenging opportunities and problems in your own organization through fresh approaches, and how to facilitate a creative problem solving workshop.

Here are The Big Bang Partnership we are expert facilitators of creative problem solving workshops . Please do comment or email us if you would like any further tips or advice, or if you’d like to explore having us design and facilitate a workshop for you.

What is Creative Problem Solving?

Creative problem solving, sometimes abbreviated to CPS, is a step-by-step process designed to spark creative thinking and innovative solutions for purposeful change.

The creative problem solving process is at the root of other contemporary creativity and innovation processes, such as innovation sprints and design sprints or design thinking . These methods have adapted and repackaged the fundamental principles of creative problem solving.

Creative Problem Solving Definition

Here are definitions of each component of the term creative problem solving process:

- Creative – Production of new and useful ideas or options.

- Problem – A gap between what you have and what you want.

- Solving – Taking action.

- Process – Steps; a method of doing something.

Source: Creative Leadership: Skills that Drive Change Puccio, Murdock, Mance (2007)

The definition of creative problem solving (CPS) is that it’s a way of solving challenges or opportunities when the usual ways of thinking have not worked.

The creative problem solving process encourages people to find fresh perspectives and come up with novel solutions. This means that they can create a plan to overcome obstacles and reach their goals by combining problem solving and creative thinking skills in one process.

Using creative problem-solving removes the haphazard way in which most organizations approach challenges and increases the probability of a successful solution that all stakeholders support.

For an overview of the history of the creative problem solving process, have a read of my article here .

Creative Problems to Solve

Just a few examples of creative problems to solve using the creative problem solving process are:

- Shaping a strategy for your organization

- Developing or improving a new product or service

- Creating a new marketing campaign

- Bringing diverse stakeholders together to collaborate on a joint plan

- Formulating work-winning solutions for new business proposals, bids or tenders

- Working on a more sustainable business model

- Finding eco-innovation solutions

- Social or community innovation

- Co-creation leading to co-production

Messy, Wicked and Tame Problems

If your problem or challenge is ‘ messy ’ or ‘ wicked ’, using the creative problem solving process is an excellent method for getting key stakeholders together to work on it collaboratively. The creative problem solving process will help you to make progress towards improving elements of your challenge.

Messy Problems

In the field of innovation, a messy problem is made up of clusters of interrelated or interdependent problems, or systems of problems. For example, the problems of unemployment in a community, the culture in a workplace or how to reach new markets are likely to be caused by multiple factors.

It’s important to deconstruct messy problems and solve each key problem area. The creative problem solving process provides a valuable method of doing so.

Wicked Problems

Design theorists Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber introduced the term “ wicked problem ” in 1973 to describe the complexities of resolving planning and social policy problems.

Wicked problems are challenges that have unclear aims and solutions. They are often challenges that keep changing and evolving. Some examples of current wicked problems are tackling climate change, obesity, hunger, poverty and more.

Tame Problems

‘ Tame ’ problems are those which have a straightforward solution and can be solved through logic and existing know-how. There is little value in using the creative problem solving process to solve tame problems.

Creative Problem Solving Skills

Specific thinking skills are essential to various aspects of the creative problem solving process. They include both cognitive (or intellectual) skills and affective (or attitudinal, motivational) skills.

There are also three overarching affective skills that are needed throughout the entire creative problem solving Process. These creative problem solving skills are:

- Openness to new things, meaning the ability to entertain ideas that at first seem outlandish and risky

- Tolerance for ambiguity, which is the ability to deal with uncertainty without leaping to conclusions

- Tolerance for complexity, defined as being able to stay open and persevere without being overwhelmed by large amounts of information, interrelated and complex issues and competing perspectives

They show an individual’s readiness to participate in creative problem solving activities.

Creative Problem Solving and Critical Thinking

Critical thinking involves reflecting analytically and more objectively on your learning experiences and working processes. Based on your reflection, you can identify opportunities for improvement and make more effective decisions.

Critical thinking is an important skill when using the creative problem solving process because it will drive you to seek clarity, accuracy, relevance and evidence throughout.

Strategies for Creative Problem Solving

One of the most successful strategies for creative problem solving process is to get a multi-disciplinary team of internal, and sometimes external, stakeholders together for a creative problem solving workshop. Here is a process that you can use to facilitate your own creative problem solving workshop.

How to Facilitate a Creative Problem Solving Workshop

Challenge or problem statement.

The first, potentially most important, stage of the creative problem solving process is to create a challenge statement or problem statement. This means clearly defining the problem that you want to work on.

A challenge or problem statement is usually a sentence or two that explains the problem that you want to address through your creative problem solving workshop.

How might we…?

A good way of expressing your challenge is to use the starting phrase “How might we …?” to produce a question that will form the core of your creative problem solving mission. Framing your problem as a question in this way helps people to begin to think about possibilities and gives scope for experimentation and ideation.

Why it’s important to have a clear problem statement

Defining your problem or challenge statement matters because it will give you and your colleagues clarity from the outset and set out a specific mission for your collaborative working.

If you begin the creative problem solving process without a clear problem or challenge statement, you’ll likely experience misunderstanding and misalignment, and need to retrace your steps. Taking time to get your challenge or problem statement right is time well spent. You can download my free resources on how to create a challenge statement for innovation and growth here .

Creative Problem Solving Process

Once you have defined your creative problem to solve, and the strategies for creative problem solving that you want to use, the next steps are to work through each stage of the creative problem solving process. You can do this on your own, with your team, working cross-functionally with people from across your organization and with external stakeholders. For every step in the creative problem solving process there is a myriad of different techniques and activities that you can use. You could literally run scores of creative problem solving workshops and never have to repeat the same format or techniques! The creative problem solving techniques that I’m sharing here are just a few examples to get you started.

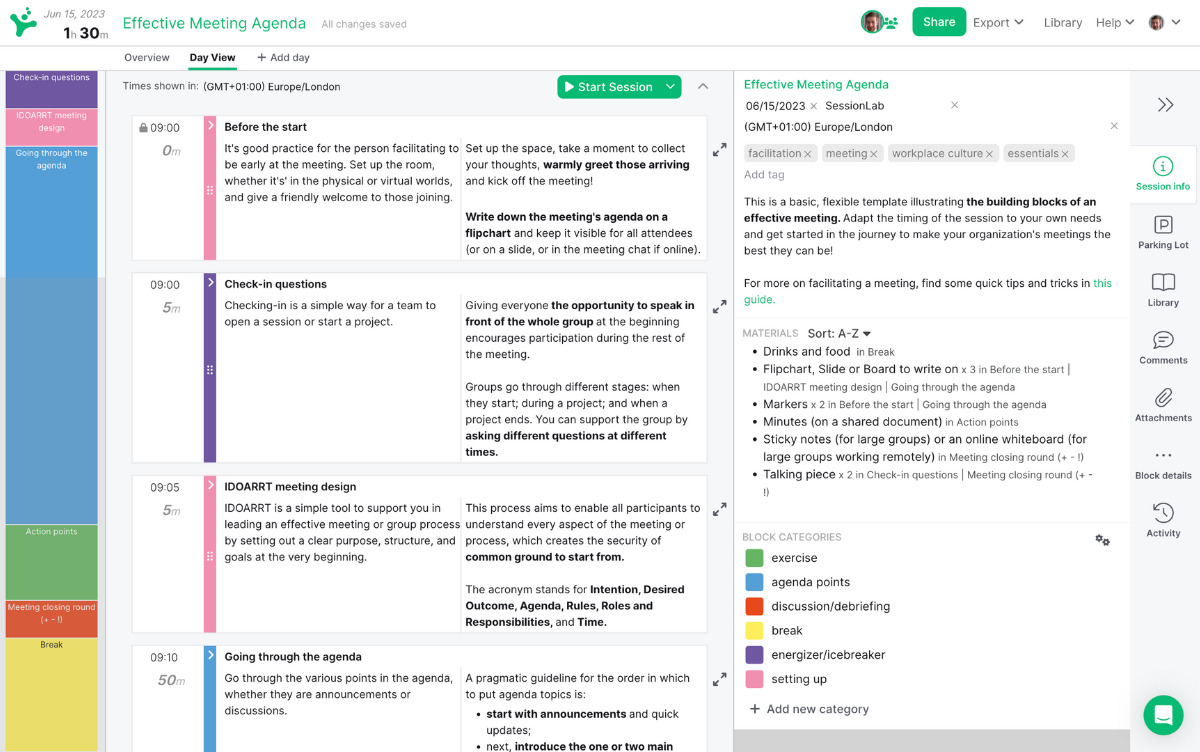

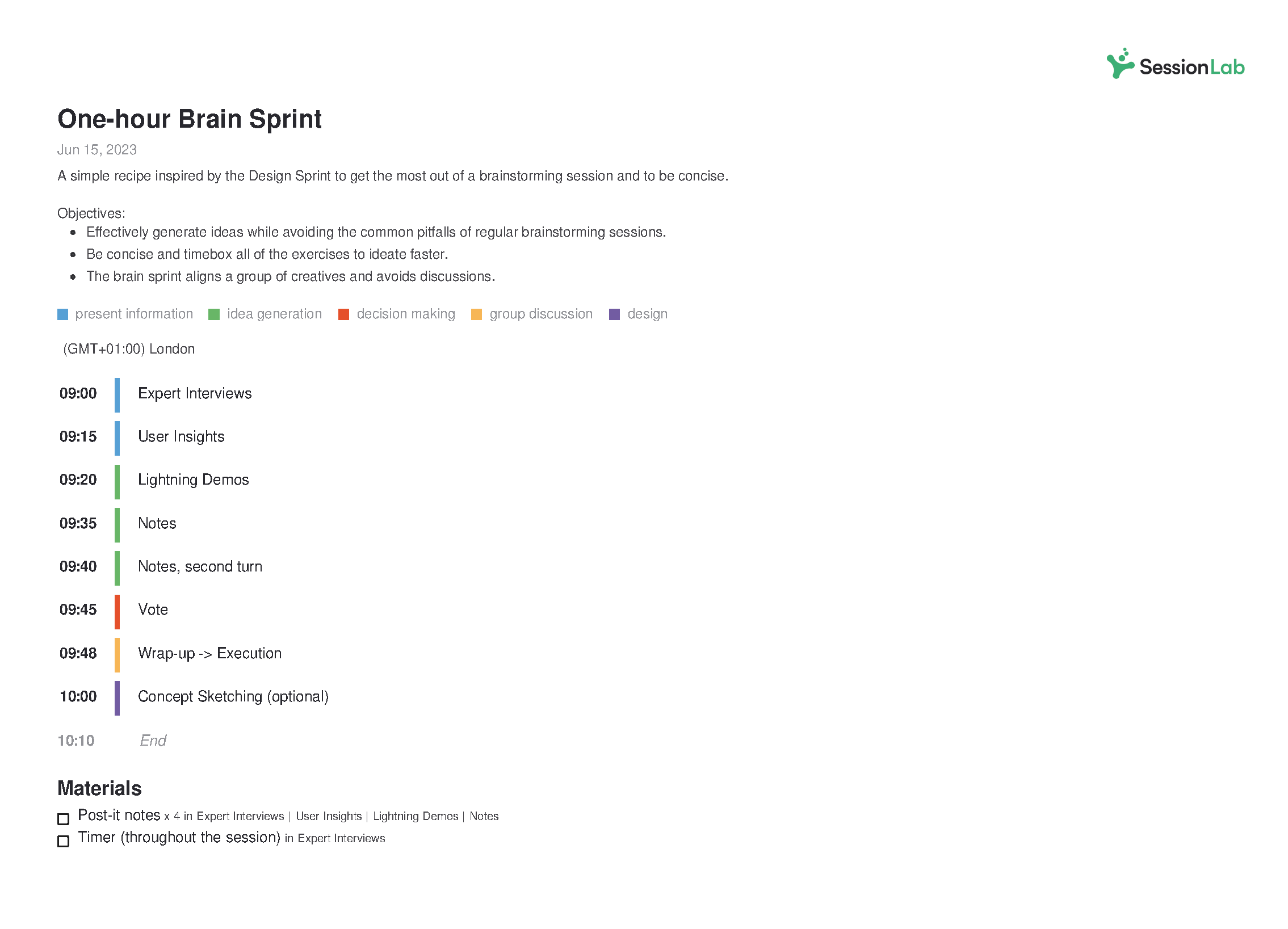

Creative Problem Solving Workshop Agenda

To make the creative problem solving process more accessible to more people, I’ve built on the work by Osborn, Parnes, Puccio and others, to create our Creative Problem Solving Workshop Journey Approach that you can use and adapt to work on literally any problem or challenge statement that you have. I’ve used it in sectors as diverse as nuclear engineering, digital and tech, utilities, local government, retail and e-ecommerce, transport, financial services, not-for-profit and many, many more.

Every single workshop we design for our clients is unique, and our starting point is always our ‘go-to’ outline agenda that we can use to save ourselves time and know that our sessions are well-designed and put together.

The timings are just my suggestion, so please do change them to suit the specific needs of your creative problem-solving workshop.

All the activities I suggest are presented for in-person workshops, and they can be adapted super-easily for virtual workshops, using and online whiteboard such as Miro .

Keep the activities for each agenda item long enough to allow people to get into it, but not too long. You want the sessions to feel appropriately pacey, active and engaging. Activities that are allowed to go on too long drag and sap creative energy.

Outline Agenda

Welcome and Warm-up 0900-0930

Where do we want to be, and why? 0930-1000

Where are we today? 1000-1030

Break 1030-1045

Why are we where we are today? 1045-1115

Moving forward – Idea generation 1115-1230

Lunch 1230-1315

Energiser 1315-1330

Moving forward – Idea development 1330-1415

Break 1415-1445

Action Planning 1445-1530

Review, feedback and close 1530-1600

Here is the agenda with more detail, and suggested activities for each item.

Detailed Creative Problem Solving Workshop Agenda

Welcome and warm-up.

The welcome and warm-up session is important because:

- For groups who don’t know each other, it’s essential that people introduce themselves and start to get to know who everyone is.

- This session also helps people to transition from their other work and activities to focusing on the purpose of the day.

- It sets the tone for the rest of the event.

Items to include in the welcome and warm-up are:

- Welcome to the event.

- Thank people for taking the time.

- The purpose and objectives of the event, and an overview of the agenda for the day. Introduce your problem or challenge statement.

- Ground rules in terms of phone usage, breaks, confidentiality.

It’s good to have the agenda and ground rules visible so that everyone can see them throughout the day, and don’t forget to inform people of any fire evacuation instructions that need to be shared, and information on refreshments, washrooms and so on.

Remember to introduce yourself and say a little bit about you as the workshop leader, keeping it brief.

Things to look out for are:

- How people are feeling – energy, interest, sociability, nervousness and so on.

- Cliques or groups of people who choose to sit together. Make a mental note to move the groups around for different activities so that people get to work with as many different people as possible to stimulate thinking and make new connections.

If you’d like some ideas for icebreakers and warmups, there are lots to choose from in these articles:

Icebreakers for online meetings

Creative warmups and energizers that you can do outside

Where do we want to be, and why?

The first session in your creative problem-solving workshop aims to start with thinking about what the group wants to achieve in the future. As well as setting the direction for your problem statement for the day, it allows delegates to stretch their thinking before they become too embedded in working through their current position, issues and concerns. It is positive and motivational to identify those aspirations that everyone shares, even if the reasons or details differ from person to person.

Suggested creative problem-solving techniques for Where do we want to be, and why ?

Horizon Scanning

Brief the delegates as follows:

- Use the resources / idea generators provided [e.g. magazines, newspapers, scissors, glue, stickers, glitter, any other craft items you like, flip chart paper) and your own thoughts.

- Identify a range of themes that are relevant to the challenge statement you are working on in this workshop. Feel free to use your imagination and be creative!

- For each theme, explain why it is important to the challenge statement.

This activity can be adapted for virtual workshops using online whiteboards such as Miro.

WIFI – Wouldn’t It Be Fantastic If…

This creative problem solving technique opens up delegates’ thinking and frames challenges as a positive and motivational possibility.

Ask delegates to spend just a few minutes completing the following statement as many times as they can with real items relating to their challenge for the workshop:

Wouldn’t it be fantastic if… (‘wifi’)

Delegates should then select the wibfi statements that would make the most material difference to their challenge.

They might have a couple or more of connected statements that they want to combine into a new one. If so, that’s completely fine.

Ask them to write their final statement on a flipchart.

Where are we today?

After establishing the vision for the future, it is important to gain a collective view on the starting point, and gain different, individual perspectives on the current position.

Suggested creative techniques for Where are we today?

Rich pictures

Rich pictures provide a useful way of capturing the elements of messy, unstructured situations and ambiguous and complex problems.

A rich picture is intended to portray the unstructured situation that the delegates are working with.

Brief the activity in as follows, noting that they can assist in the construction of a rich picture which should initially be rich in content, but the meaning of which may not be initially apparent.

- Ask delegates to consider the messy problem or situation that they are facing and dump all the elements of the scenario they are viewing in an unstructured manner using symbols and doodles.

- Ask them to look for elements of structure such as buildings and so on, and elements of process such as things in a state of change. They may see ways in which the structure and process interact as they use hard factual data and soft subjective information in the picture.

- If appropriate, ask the delegates to include themselves in the picture as participants or observers, or both, and to give the rich picture meaningful and descriptive title.

- Without explanation, one group’s rich picture is often a mystery to another observer, so ask small working groups to talk through the, to the wider group. It is not meant to be a work of art but a working tool to assist your delegates in understanding an unstructured problem or change scenario.

Out of the box

Representing a problem in any new medium can help bring greater understanding and provide a rich vehicle for discussion and idea generation.

Collect a range of (clean and safe!) junk materials, such as cardboard boxes, empty packets, old magazines and newspapers etc.

You will also need some string, glue and tape.

Ask delegates to use the items around them to create (a) 3D vision(s) of the solution(s) to their challenge.

This provides a different perspective, as well as getting everyone engaged, active and conversing.

Why are we here?

This stage of the away day focuses on helping the group to understand the critical success factors that have driven positive outcomes, as well as any constraints, perceived or real, that are getting in the way of future progress. It identifies items that can be explored further in the idea generation, selection and development stages.

Suggested creative techniques for Why are we here?

Ishikawa Fish Bone

The fishbone diagram was developed by Professor Ishikawa of the University of Tokyo. It can encourage development of a comprehensive and balanced picture, involving everyone, keeping everyone on track, discouraging partial or premature solutions, and showing the relative importance and interrelationships between different parts of the challenge.

Ask the delegates to write their problem statement to the fish bone template, like the example shown here.

Then ask them to identify the major categories of causes of the problem. If they are stuck on this, suggest some generic categories to get them going, such as:

Delegates should then write the categories of causes as branches from the main arrow.

Next, they will identify all the possible causes of the problem, asking: “Why does this happen?”

As each idea is given, one of the delegates in each group writes it as a branch from the appropriate category. Causes can be written in several places if they relate to several categories.

Again, get the delegates to ask: “why does this happen?” about each cause, and write sub–causes branching off the causes.

If you have time, ask the delegates to carry on asking “Why?” and generating deeper levels of causes.

Mind mapping

The term mind mapping was devised by Tony Buzan for the representation of ideas, notes, information and so on in radial tree diagrams, sometimes also called spider diagrams.

These are now very widely used.

To brief in the mind map technique, the instructions below are usually best communicated via a quick demonstration by the facilitator, using an everyday, fun topic and asking delegates to shout out ideas for you to capture.

How to mind map:

- Ask delegates to turn their paper to landscape format and write a brief title for the overall topic in the middle of the page.

- For each major subtopic or cluster of materials ask them to start a new major branch from the central topic and label it.

- Continue in this way for ever finer sub-branches.

- Delegates may find that they want to put an item in more than one place. They could just copy it into each place or they could just draw a line to show the connections.

- Encourage delegates to use colour, doodles and to have fun with their mind map. This stimulates more right brain, creative thinking.

Moving forward – Idea generation

The next sessions are all about coming up with ideas, potential solutions to get from your starting position to the vision for the future that you all created earlier.

I recommend that you use at least two, or preferably all three of the idea generation techniques I have provided here because if you only use one, you are more likely to only get the most obvious, top of mind ideas from your team.

By looking at your challenge or opportunity from different perspectives using a range of techniques, you are more likely to create greater diversity of ideas.

This technique is really good for almost any subject, and especially…

…getting input from everyone. The noisy ones have much less opportunity to dominate!

…getting all the thoughts that people have out of their heads and onto paper.

…getting you started. This is a really accessible technique that is easy to run.

…getting people talking and engaged.

You will need plenty of sticky notes and pens.

Clustering with sticky notes – step-by-step guide

- Ask people to focus on the challenge that is the subject of the session.

- Each person is to work individually at first. They will take a pile of post-it notes and a pen, and get as many items down on the post-it notes as they can, writing only one item on each post-it note so that each person has a pile of written notes in front of them (12-15 each would be great).

- Say to the group that if they think they have finished, it probably is just a mental pause. The best thing for them to do is to look out of the window or move around briefly (but not look at their phones, laptop or disturb other people!) because they are likely to have a second burst of thinking. This is really important because it means you will get more thoughts down than just the obvious front-of-mind ones that come out early on. Allow 5-10 minutes for this step.

- Make sure that people don’t put more than one item on a post-it note.

- When everyone has got a pile of sticky notes and generally have run out of steam, ask them to “cluster” their notes as a group into similar themes on the flip chart paper, a bit like playing the card game “Snap”. Things that no-one else has should be included as a cluster of one item.

- Ask the groups to put a ring around each cluster and give it a name that summarises the content.

- Ask each group to feedback on the contents of their clusters, note similarities and differences and agree your next steps, writing them up on the flip chart for everyone to see.

Force-fitting with pictures

Force-fitting is about using dissimilar, or apparently unrelated, objects, elements, or ideas to obtain fresh new possibilities for a challenge or opportunity. You will need some magazines, photos or newspapers for this activity.

It is a very useful and fun-filled method of generating ideas. The idea is to compare the problem with something else that has little or nothing in common and gain new insights as a result.

You can force a relationship between almost anything, and get new insights – companies and whales, management systems and data networks, or your relationship and a hedgehog. Forcing relationships is one of the most powerful ways to develop ways to develop new insights and new solutions.

The following activity – Random Stimulus, a useful way of generating ideas through a selection of objects or cards with pictures – takes about 15 to 20 minutes to complete in total.

It is important to brief delegates to work intuitively through this process rather than over-thinking it. Just follow each of the simple steps outlined here in order.

Force-fitting with pictures step-by-step guide

Step 1 : Choose an image from the ones below at random. It really does not matter which one you choose, so just pick one that you think is interesting. This should take you no longer than a few seconds! Do this first before you move to the next steps.

Step 2: Now look at the image that you have selected. Feel free to pull it out so you can have it in front of you as you work. Write down as many interesting words as you can that come to mind when you look at the picture you have selected.

Step 3 : Now go back and “force fit” each of your interesting words into a potential solution for your challenge. If you have a negative word, turn it into a positive solution. Do this for every word on your list. You don’t have to work through the list in order – if you get stuck on a word, do another one and then come back to it when you’re ready. Don’t forget – premature evaluation stifles creativity. Just write stuff down without judging anything. You will have the opportunity to go back and select what you want / don’t want to use later.

Step 4 : Look at your outputs from this activity and highlight the things that resonate with you in terms of making progress with your challenge.

The SCAMPER technique is based very simply on the idea that anything new is actually a modification of existing old things around us.

SCAMPER was first introduced by Bob Eberle to address targeted questions that help solve problems or ignite creativity during creative meetings.

The name SCAMPER is acronym for seven thinking activities: ( S ) substitute, ( C ) combine, ( A ) adapt, ( M ) modify, ( P ) put to another use, ( E ) eliminate and ( R ) reverse. These keywords represent the necessary questions addressed during the creative thinking meeting. Ask you delegates to work through each one.

- S —Substitute (e.g., components, materials, people)

- C —Combine (e.g., mix, combine with other assemblies or services, integrate)

- A —Adapt (e.g., alter, change function, use part of another element)

- M —Magnify/Modify (e.g., increase or reduce in scale, change shape, modify attributes)

- P —Put to other uses

- E —Eliminate (e.g., remove elements, simplify, reduce to core functionality)

- R —Rearrange/Reverse (e.g., turn inside out or upside down)

Moving forward – Idea development

The objective of this session is to select the most useful or interesting ideas that you have come up with in the earlier idea generation activities, and shape them into a useful solution.

Suggested creative techniques for Moving forward – Idea development:

This is a useful exercise to help your delegates to quickly prioritise their ideas as a team.

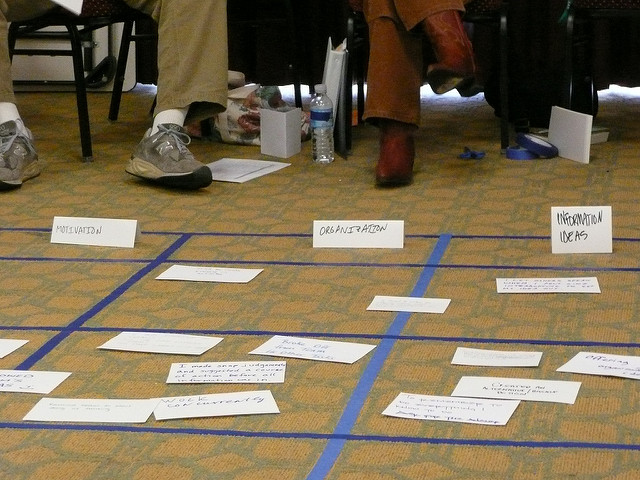

- Ask delegates to use the grid shown here to plot their ideas, using sticky notes/

- They should then write a question for each of their ‘yes’ and perhaps some of your ‘maybe’ items that begins with the words ‘ How could we …? ’

- Then ask them to work on each of their questions, capturing their work a flipchart.

Sticky dot voting

Sticky dot voting is a quick, widely used voting method. Once all the ideas are on display give each group member a number of sticky dots (for example 5 each) to ‘vote’ for their favourite solution or preferred option. The number of sticky dots can vary according to what you think will work.

- Give everyone a few minutes of quiet planning time so that they can privately work out their distribution of votes.

- They may distribute their votes as they wish, for example: 2 or 3 on one idea, one each on a couple of others, all on one idea or one each on a whole series of ideas.

- To minimise the risk of people being influenced by one another’s votes, no votes are placed until everyone is ready. When everyone is finished deciding, they go up to the display and place their votes by sticking dots beside the items of their choice.

- As facilitator, lead a discussion on the vote pattern, and help the group to translate it into a shortlist for further development.

Once your delegates have selected their most promising ideas, choose from these creative problem solving techniques to help your group develop their thinking.

Assumption surfacing

Assumption surfacing is all about making underlying assumptions more visible.

- Ask the group to identify the key choices they have made, thinking about what assumptions have guided these choices and why they feel they are appropriate.

- Delegates should list the assumptions, and then add in a possible counter-assumption for each one.

- They should then work down the list and delete any assumption / counter assumption pairs that do not materially affect the outcome of the choice.

- Finally, ask delegates to reflect on the remaining assumptions, consider how these assumptions potentially impact their thinking and whether anything needs to be done as a result.

The words who, why, what, where, when, how are known as 5Ws and H, or Kipling’s list.

They provide a powerful checklist for imagination or enquiry that is simple enough to prompt thinking but not get in the way.

Ask delegates to:

- Create a list of key questions relating to their challenge, using 5Ws and H as prompts.

- Then ask them to answer of their questions as a way of info gathering and solution-finding for their challenge.

Force field analysis

Force field analysis represents the opposing driving and restraining forces in situation.

For example, it can help to map out the factors involved in a problematic situation at the problem exploration stage, or to understand factors likely to help or hinder the action planning and implementation stages.

The process is as follows:

- Delegates identify a list of the driving and restraining forces and discuss their perceptions of them.

- All the driving forces are arrows propelling the situation, and all the restraining forces are arrows that push back against the direction of the current situation.

- Delegates can use arrow thickness to indicate strength of the force, and arrow lengths to indicate either how difficult the force would be to modify, although these elements are optional.

- Delegates can then use the diagrams to generate ideas around possible ways to move in the desired direction by finding ways to remove the restraining forces and by increasing the driving forces.

Wizard of Oz prototyping

In the classic story of the Wizard of Oz, Dorothy and her friends go to see the Great and Powerful Wizard of Oz only to discover that he’s a fraud with no real magic.

Wizard of Oz Prototyping means creating a user experience that looks and feels very realistic, but is an illusion created to test an idea and generate a lot of really useful feedback very quickly and early on in your design process. The approach also means that you avoid incurring the cost of having to build the real solution.

In the workshop, ask delegates to consider how they could create a Wizard of Oz prototype through rough design sketches, lego or modelling clay.

Action Planning

I’m sure that many of us have been to meetings or events that have been interesting and maybe even fun at the time, but quickly forgotten due to lack of follow up or commitment to take action once the workshop is over.

The action planning phase is an essential part of mobilising the thinking from the workshop into meaningful, pragmatic activity and progress in the organisation. Getting commitment to deliver specific actions within agreed timescales from individuals at the workshop is as essential part of any event.

Suggested creative technique for Action Planning :

Blockbusters

You may remember the 80s quiz show called Blockbusters? Teenage contestants had to get from one side of the board to the other by answering questions.

This technique is based on a similar (sort of!) principle, and it is useful for action planning and helping delegates to visualise moving from where they are now to where they want to be.

- First ask delegates to write down the key aspects of where they are now on sticky notes (one item per sticky note) and put them down the left-hand side of a piece of flipchart paper, landscape.

- Then delegates are to do the same for the key aspects of where they would like to be, this time placing the sticky notes on the right-hand side of the paper, each one aligned to a relevant note on the left-hand side. For example, of they have a sticky note that says ‘struggling for sales’ on the left, they might have one that says ‘increase turnover by 35%’ on the right, both positioned level with each other.

- The final step is for delegates to fill in the space between with the 5 key actions for each item that will get them from where they are now to where they want to be. These can be different and separate actions, and don’t have to be in chronological order.

- You can ask delegates to add in target timescales and owners for each action as well.

Review, feedback and close

At the end of the day, it’s essential to bring everything together, review the progress and thank attendees.

It’s also a great opportunity to gain some feedback on the participants’ experience of the session.

Suggested creative technique for Review, feedback and close :

Goldfish Bowl

The general idea of this technique is that a small group (the core) is the focus of the wider group. The small group discusses while the rest of the participants sit around the outside and observe without interrupting. Facilitation is focused on the core group discussion.

A variation is to invite people from the outside group to ‘jump in’ and replace a member of the core group. It sounds a bit odd on paper, but it works very well and can be great fun.

Sometimes people in the core group are quite pleased to be ‘relieved’ of their duties!

In smaller events, it is also a good idea to make it a game. Make sure that everyone jumps into the core group at least once.

This can really help people focus on active listening, and on building on each other’s points.

Often the best way to brief this in is by demonstrating it with a willing volunteer.

For more facilitation tips, techniques and ideas, have a look at my articles here:

How to design a virtual innovation sprint

How to facilitate a virtual brainstorming session

How to facilitate a goal setting workshop

How to be a great facilitator

I’d love to hear from you, whether you’re facilitating your own creative problem solving workshops, or would like some help from us to design and facilitate them for you. I hope you’ve found this article helpful. If you’d like to join my free, private Facebook group, Idea Time for Workshop Facilitators , for even more ideas and resources, please do come and join us.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Some of our clients

- Jo's PhD Research

- CONTENT STUDIO

- Idea Time Book

- Innovation Events

- Innovation Consulting

- Creative Facilitation Skills

- Executive Development

Privacy Policy © The Big Bang Partnership Limited 2023

Privacy Overview

10 Tips for Facilitating Your Problem-Solving Workshop

A problem-solving workshop is a structured approach to address a particular challenge or issue that a team or organization is facing. The workshop is designed to bring together a diverse group of individuals with different perspectives, skills, and knowledge to collaborate on identifying and solving the problem at hand.

The workshop typically involves a series of activities and exercises designed to help participants understand the problem, generate ideas for potential solutions, and evaluate and prioritise those solutions based on a set of criteria or metrics . Depending on the nature of the problem and the desired outcomes of the workshop, the exercises may include brainstorming sessions, group discussions, role-playing exercises, prototyping, or other activities.

The goal of a problem-solving workshop is to create a collaborative, creative, and open environment where participants feel empowered to share their ideas, challenge assumptions, and work together towards a common goal. By bringing together a diverse group of individuals with different perspectives and expertise, the workshop can tap into a wide range of knowledge and experience, which can lead to more innovative and effective solutions.

The workshop may be facilitated by an internal or external facilitator, who can help to guide the participants through the process and keep them focused on the problem at hand. Depending on the complexity of the problem and the size of the group, the workshop may take anywhere from a few hours to several days to complete.

Our top tips for facilitating a problem solving workshop are:

- Clearly define the problem: Before starting the workshop, make sure the problem is clearly defined and understood by all participants.

- Establish ground rule s: Set clear guidelines for how the workshop will be conducted, including rules for respectful communication and decision-making.

- Encourage diverse perspectives: Encourage participants to share their diverse perspectives and experiences, and consider using techniques such as brainstorming to generate a wide range of ideas.

- Use a structured process: Utilize a structured problem-solving process, such as the six-step process outlined by the International Association of Facilitators, to guide the workshop.

- Promote active listening : Encourage participants to actively listen to each other and seek to understand different viewpoints.

- Encourage collaboration : Foster a collaborative atmosphere by encouraging teamwork and shared ownership of the problem-solving process.

- Facilitate decision making : Help participants make informed decisions by providing them with the necessary information and resources.

- Encourage creativity : Encourage participants to think creatively and outside the box to generate new ideas and solutions.

- Monitor and manage group dynamics : Pay attention to group dynamics and intervene as needed to keep the workshop on track and prevent conflicts.

- Follow up and review: Follow up on the outcomes of the workshop and review the results to continually improve the problem-solving process.

Here are some exercises that may be more fun and engaging for a problem-solving workshop:

- Escape room : Create an escape room-style challenge that requires participants to solve a series of problems to escape the room.

- Treasure hunt: Create a treasure hunt that requires participants to solve clues and riddles to find hidden objects or reach a goal.

- Charades: Have participants act out different scenarios related to the problem and have the rest of the group guess what they are trying to communicate.

- Jigsaw puzzles : Use jigsaw puzzles as a metaphor for solving problems and have participants work together to piece the puzzle together.

- Improv games: Use improv games, such as “Yes, And,” to encourage creativity and build teamwork skills.

- Scavenger hunt : Create a scavenger hunt that requires participants to solve clues and challenges to find hidden objects or complete tasks.

- Board games : Use board games that require problem-solving skills, such as escape room-style games or strategy games, to make problem-solving more interactive and fun.

- Puzzle-based challenges: Create puzzle-based challenges that require participants to solve a series of interconnected problems to reach a goal.

- Role-playing games : Use role-playing games, such as Dungeons and Dragons, to encourage creative problem solving and teamwork.

- Creativity challenges : Use creativity challenges, such as “the Marshmallow Challenge,” to encourage out-of-the-box thinking and teamwork.

In conclusion, a problem-solving workshop can be a powerful tool for teams and organisations looking to tackle complex challenges and drive innovation. By bringing together a diverse group of individuals with different perspectives and expertise, the workshop can create a collaborative, creative, and open environment where participants feel empowered to share their ideas, challenge assumptions, and work towards a common goal.

While the success of a problem-solving workshop depends on many factors, such as the facilitation, the quality of the problem statement, and the engagement of the participants, the potential benefits are significant. By tapping into the collective intelligence of the group, the workshop can generate new ideas, identify blind spots, and build consensus around potential solutions. Moreover, the workshop can help to foster a culture of collaboration, learning, and innovation that can have a lasting impact on the team or organization.

Related Posts

The 16th Annual State of Agile Report

How Do Web3 and Agile Combine To Enhance Development

Difference Between Agile and Explain Organic Agile

Why Spillover Happens and Why You Shouldn’t Worry

The Johari Window and Agile Methodologies – An Explosive Combo

“Dual Track” Agile

Main Differences Between Three Concepts – Agile, Scrum, And Kanban

Why Teams Outcome Is More Important Than Its Velocity or Even Output

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Copyright © 2023 Agile Heuristics. All rights reserved. Agile Heuristics Ltd is a private limited company, registered in the United Kingdom, with company number 14699131

- White Papers

The Value of a Facilitator in Organizational Problem Solving and Decision Making

- Facilitation Services Integrate analytic thinking skills into the way work gets done Learn More

Overcome the five biggest barriers to group troubleshooting success

In today´s world of complex technology, dealing with multiple teams of hard-core specialists, it becomes more and more difficult to manage actions and stay in control. At Kepner-Tregoe (KT), our research and experience show that one specific role can provide a troubleshooting group with the clear focus and strong leadership that brings closure more quickly and initiates the actions to prevent a reoccurrence. That role is the facilitator.

In many organizations, the initial response to a major incident such as a service outage is to hold a meeting or set up a bridge call. The hope, obviously, is that the problem at hand can be solved by bringing together people with the right knowledge and experience. That these meetings often occur under high pressure—with services already down and stakeholders demanding resolution—makes achieving a positive outcome that much more difficult.

So, the way these meetings are run becomes extremely important. It not only determines whether they produce an effective solution, it also makes a difference in the emotional burden, financial cost and the reputation of the support organization.

Bridge calls and meetings benefit from strong leadership that keeps the group focused on the issues and avoids finger pointing or jumping to conclusions. Guidance and focus are just as important for meetings or calls which don’t take place under pressure but are convened to address ongoing problems. After all, it can be de-motivating to the whole team to be working on an issue which has been open for many months only to discover that the wrong actions have been taken.

Answering questions such as the following, can help you determine the effectiveness of these meetings or their leadership:

- What progress was made during group troubleshooting sessions?

- How much clarity was gained from the meeting?

- To what extent were people involved?

- Were the right people present?

- Was there a free exchange of ideas or was the group forced to listen to the one who shouted the loudest?

Imagine yourself as the leader, or recall the last time you led a problem-solving group. How well do you think you were in control? What tips, tricks or magic did you use to assert your leadership and direct the group in the right direction? Do you know the most effective way to lead a group to a successful outcome?

This article will describe the role of a facilitator: the challenges organizations face which call for a facilitator’s help, the skills they need in order to stay in control and the benefits of having this role recognized within an organization.

What is a facilitator?

The dictionary defines a facilitator as someone who helps a group of people understand their common objectives and assists them in achieving them without taking a particular position in the discussion. In performing this function, a facilitator:

- Stays neutral, while guiding the group to consensus.

- Uses a structured process to gain an overview of the issue.

- Supports everyone to do their best thinking and work.

- Synergizes the group to work more effectively.

- Stimulates group creativity and encourages everyone to contribute.

A facilitator makes it easier for the group to work together as a team. In this sense, a facilitator acts like a catalyst. He or she does not wield a magic wand that will solve all the issues facing the group, but rather focuses the group on the process that leads towards a common resolution. The role of a facilitator is very much like a conductor in front of an orchestra.

Why is facilitation needed?

Now that we understand what a facilitator is, why is it valuable to distinguish this role and give people the skills to become a process facilitator?

Based on our research, the primary value of a skilled facilitator is the ability to lead groups to effective solutions by helping them to overcome the five biggest challenges in problem solving and decision making. In project meetings, shift-handovers, troubleshooting sessions, decision making bodies, operational meetings and crisis management situations, we have seen effective application of facilitator skills prove invaluable in overcoming these challenges.

Challenge 1: Thinking within the box

Groups assembled to solve an organizational problem typically consist of people who fill any one of four primary roles:

- Subject Matter Experts: those who have a deep, technical understanding of the issue at hand. They are needed for the correct and factual information they can provide for solving the problem. Subject matter experts may come from inside or from outside the company; for example, they could be partners, sub-contractors or suppliers.

- Problem Owner: the one person who has the authority and accountability to address a problem’s cause, and initiate the solution, thus resolving the problem and reversing its effects. This is the person who most feels the need to get the issue resolved, and who should be able to command the influence and budget to make that happen. The group could also include a person representing the end-customers who are affected by the problem, but do not have ownership of its cause or resolution.

- Third Parties: representatives from other teams—for example legal, insurance or marketing—who are interested in “who to blame”.

- Facilitator: the one who chairs the meeting and takes a leading role in managing the underlying structure of the problem resolution. The facilitator provides guidance for the group by keeping an oversight of the issue and managing the group’s troubleshooting process.

Because of the different viewpoints that people bring to these different roles, some of them may not be the best choice to serve as a facilitator.

Subject matter experts who attempt the facilitator role may have difficulty seeing beyond their particular areas of competency, knowledge and experience. Expertise in itself doesn’t make them the right facilitator. Often too focused on the content, experts may elaborate on the details of a specific operation and jump to incorrect conclusions.