6.4 Annotated Student Sample: “Slowing Climate Change” by Shawn Krukowski

Learning outcomes.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify the features common to proposals.

- Analyze the organizational structure of a proposal and how writers develop ideas.

- Articulate how writers use and cite evidence to build credibility.

- Identify sources of evidence within a text and in source citations.

Introduction

The proposal that follows was written by student Shawn Krukowski for a first-year composition course. Shawn’s assignment was to research a contemporary problem and propose one or more solutions. Deeply concerned about climate change, Shawn chose to research ways to slow the process. In his proposal, he recommends two solutions he thinks are most promising.

Living by Their Own Words

A call to action.

student sample text The earth’s climate is changing. Although the climate has been changing slowly for the past 22,000 years, the rate of change has increased dramatically. Previously, natural climate changes occurred gradually, sometimes extending over thousands of years. Since the mid-20th century, however, climate change has accelerated exponentially, a result primarily of human activities, and is reaching a crisis level. end student sample text

student sample text Critical as it is, however, climate change can be controlled. Thanks to current knowledge of science and existing technologies, it is possible to respond effectively. Although many concerned citizens, companies, and organizations in the private sector are taking action in their own spheres, other individuals, corporations, and organizations are ignoring, or even denying, the problem. What is needed to slow climate change is unified action in two key areas—mitigation and adaptation—spurred by government leadership in the United States and a global commitment to addressing the problem immediately. end student sample text

annotated text Introduction. The proposal opens with an overview of the problem and pivots to the solution in the second paragraph. end annotated text

annotated text Thesis Statement. The thesis statement in last sentence of the introduction previews the organization of the proposal and the recommended solutions. end annotated text

Problem: Negative Effects of Climate Change

annotated text Heading. Centered, boldface headings mark major sections of the proposal. end annotated text

annotated text Body. The three paragraphs under this heading discuss the problem. end annotated text

annotated text Topic Sentence. The paragraph opens with a sentence stating the topics developed in the following paragraphs. end annotated text

student sample text For the 4,000 years leading up to the Industrial Revolution, global temperatures remained relatively constant, with a few dips of less than 1°C. Previous climate change occurred so gradually that life forms were able to adapt to it. Some species became extinct, but others survived and thrived. In just the past 100 years, however, temperatures have risen by approximately the same amount that they rose over the previous 4,000 years. end student sample text

annotated text Audience. Without knowing for sure the extent of readers’ knowledge of climate change, the writer provides background for them to understand the problem. end annotated text

student sample text The rapid increase in temperature has a negative global impact. First, as temperatures rise, glaciers and polar ice are melting at a faster rate; in fact, by the middle of this century, the Arctic Ocean is projected to be ice-free in summer. As a result, global sea levels are projected to rise from two to four feet by 2100 (U.S. Global Change Research Program [USGCRP], 2014a). If this rise actually does happen, many coastal ecosystems and human communities will disappear. end student sample text

annotated text Discussion of the Problem. The first main point of the problem is discussed in this paragraph. end annotated text

annotated text Statistics as Evidence. The writer provides specific numbers and cites the source in APA style. end annotated text

annotated text Transitions . The writer uses transitions here (first, as a result , and second in the next paragraph) and elsewhere to make connections between ideas and to enable readers to follow them more easily. At the same time, the transitions give the proposal coherence. end annotated text

student sample text Second, weather of all types is becoming more extreme: heat waves are hotter, cold snaps are colder, and precipitation patterns are changing, causing longer droughts and increased flooding. Oceans are becoming more acidic as they increase their absorption of carbon dioxide. This change affects coral reefs and other marine life. Since the 1980s, hurricanes have increased in frequency, intensity, and duration. As shown in Figure 6.5, the 2020 hurricane season was the most active on record, with 30 named storms, a recording-breaking 11 storms hitting the U.S. coastline (compared to 9 in 1916), and 10 named storms in September—the highest monthly number on record. Together, these storms caused more than $40 billion in damage. Not only was this the fifth consecutive above-normal hurricane season, it was preceded by four consecutive above-normal years in 1998 to 2001 (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 2020). end student sample text

annotated text Discussion of the Problem. The second main point of the problem is discussed in this paragraph. end annotated text

annotated text Visual as Evidence. The writer refers to “Figure 6.4” in the text and places the figure below the paragraph. end annotated text

annotated text Source Citation in APA Style: Visual. The writer gives the figure a number, a title, an explanatory note, and a source citation. The source is also cited in the list of references. end annotated text

Solutions: Mitigation and Adaptation

annotated text Heading. The centered, boldface heading marks the start of the solutions section of the proposal. end annotated text

annotated text Body. The eight paragraphs under this heading discuss the solutions given in the thesis statement. end annotated text

student sample text To control the effects of climate change, immediate action in two key ways is needed: mitigation and adaptation. Mitigating climate change by reducing and stabilizing the carbon emissions that produce greenhouse gases is the only long-term way to avoid a disastrous future. In addition, adaptation is imperative to allow ecosystems, food systems, and development to become more sustainable. end student sample text

student sample text Mitigation and adaptation will not happen on their own; action on such a vast scale will require governments around the globe to take initiatives. The United States needs to cooperate with other nations and assume a leadership role in fighting climate change. end student sample text

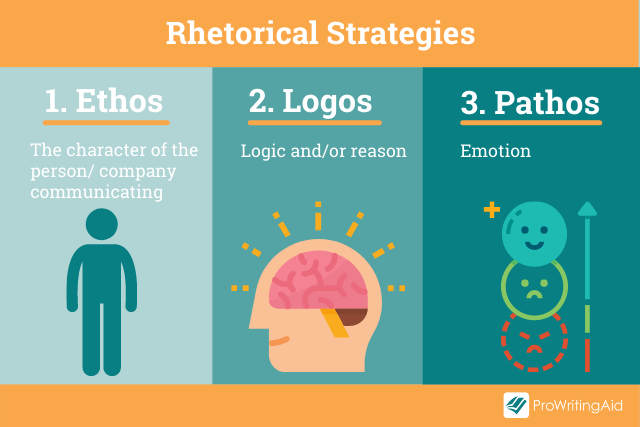

annotated text Objective Stance. The writer presents evidence (facts, statistics, and examples) in neutral, unemotional language, which builds credibility, or ethos, with readers. end annotated text

annotated text Heading. The flush-left, boldface heading marks the first subsection of the solutions. end annotated text

annotated text Topic Sentence. The paragraph opens with a sentence stating the solution developed in the following paragraphs. end annotated text

student sample text The first challenge is to reduce the flow of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. The Union of Concerned Scientists (2020) warns that “net zero” carbon emissions—meaning that no more carbon enters the atmosphere than is removed—needs to be reached by 2050 or sooner. As shown in Figure 6.6, reducing carbon emissions will require a massive effort, given the skyrocketing rate of increase of greenhouse gases since 1900 (USGCRP, 2014b). end student sample text

annotated text Synthesis. In this paragraph, the writer synthesizes factual evidence from two sources and cites them in APA style. end annotated text

annotated text Visual as Evidence. The writer refers to “Figure 6.5” in the text and places the figure below the paragraph. end annotated text

student sample text Significant national policy changes must be made and must include multiple approaches; here are two areas of concern: end student sample text

annotated text Presentation of Solutions. For clarity, the writer numbers the two items to be discussed. end annotated text

student sample text 1. Transportation systems. In the United States in 2018, more than one-quarter—28.2 percent—of emissions resulted from the consumption of fossil fuels for transportation. More than half of these emissions came from passenger cars, light-duty trucks, sport utility vehicles, and minivans (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency [EPA], 2020). Priorities for mitigation should include using fuels that emit less carbon; improving fuel efficiency; and reducing the need for travel through urban planning, telecommuting and videoconferencing, and biking and pedestrian initiatives. end student sample text

annotated text Source Citation in APA Style: Group Author. The parenthetical citation gives the group’s name, an abbreviation to be used in subsequent citations, and the year of publication. end annotated text

student sample text Curtailing travel has a demonstrable effect. Scientists have recorded a dramatic drop in emissions during government-imposed travel and business restrictions in 2020. Intended to slow the spread of COVID-19, these restrictions also decreased air pollution significantly. For example, during the first six weeks of restrictions in the San Francisco Bay area, traffic was reduced by about 45 percent, and emissions were roughly a quarter lower than the previous six weeks. Similar findings were observed around the globe, with reductions of up to 80 percent (Bourzac, 2020). end student sample text

annotated text Source Citation in APA Style: One Author. The parenthetical citation gives the author’s name and the year of publication. end annotated text

student sample text 2. Energy production. The second-largest source of emissions is the use of fossil fuels to produce energy, primarily electricity, which accounted for 26.9 percent of U.S. emissions (EPA, 2020). Fossil fuels can be replaced by solar, wind, hydro, and geothermal sources. Solar voltaic systems have the potential to become the least expensive energy in the world (Green America, 2020). Solar sources should be complemented by wind power, which tends to increase at night when the sun is absent. According to the Copenhagen Consensus, the most effective way to combat climate change is to increase investment in green research and development (Lomborg, 2020). Notable are successes in the countries of Morocco and The Gambia, both of which have committed to investing in national programs to limit emissions primarily by generating electricity from renewable sources (Mulvaney, 2019). end student sample text

annotated text Synthesis. The writer develops the paragraph by synthesizing evidence from four sources and cites them in APA style. end annotated text

student sample text A second way to move toward net zero is to actively remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Forests and oceans are so-called “sinks” that collect and store carbon (EPA, 2020). Tropical forests that once made up 12 percent of global land masses now cover only 5 percent, and the loss of these tropical forest sinks has caused 16 to 19 percent of greenhouse gas emissions (Green America, 2020). Worldwide reforestation is vital and demands both commitment and funding on a global scale. New technologies also allow “direct air capture,” which filers carbon from the air, and “carbon capture,” which prevents it from leaving smokestacks. end student sample text

student sample text All of these technologies should be governmentally supported and even mandated, where appropriate. end student sample text

annotated text Synthesis. The writer develops the paragraph by synthesizing evidence from two sources and cites them in APA style. end annotated text

annotated text Heading. The flush-left, boldface heading marks the second subsection of the solutions. end annotated text

student sample text Historically, civilizations have adapted to climate changes, sometimes successfully, sometimes not. Our modern civilization is largely the result of climate stability over the past 12,000 years. However, as the climate changes, humans must learn to adapt on a national, community, and individual level in many areas. While each country sets its own laws and regulations, certain principles apply worldwide. end student sample text

student sample text 1. Infrastructure. Buildings—residential, commercial, and industrial—produce about 33 percent of greenhouse gas emissions worldwide (Biello, 2007). Stricter standards for new construction, plus incentives for investing in insulation and other improvements to existing structures, are needed. Development in high-risk areas needs to be discouraged. Improved roads and transportation systems would help reduce fuel use. Incentives for decreasing energy consumption are needed to reduce rising demands for power. end student sample text

student sample text 2. Food waste. More than 30 percent of the food produced in the United States is never consumed, and food waste causes 44 gigatons of carbon emissions a year (Green America, 2020). In a landfill, the nutrients in wasted food never return to the soil; instead, methane, a greenhouse gas, is produced. High-income countries such as the United States need to address wasteful processing and distribution systems. Low-income countries, on the other hand, need an infrastructure that supports proper food storage and handling. Educating consumers also must be a priority. end student sample text

annotated text Source Citation in APA Style: Group Author. The parenthetical citation gives the group’s name and the year of publication. end annotated text

student sample text 3. Consumerism. People living in consumer nations have become accustomed to abundance. Many purchases are nonessential yet consume fossil fuels to manufacture, package, market, and ship products. During World War II, the U.S. government promoted the slogan “Use It Up, Wear It Out, Make It Do, or Do Without.” This attitude was widely accepted because people recognized a common purpose in the war effort. A similar shift in mindset is needed today. end student sample text

student sample text Adaptation is not only possible but also economically advantageous. One case study is Walmart, which is the world’s largest company by revenue. According to Dearn (2020), the company announced a plan to reduce its global emissions to zero by 2040. Among the goals is powering its facilities with 100 percent renewable energy and using electric vehicles with zero emissions. As of 2020, about 29 percent of its energy is from renewable sources. Although the 2040 goal applies to Walmart facilities only, plans are underway to reduce indirect emissions, such as those from its supply chain. According to CEO Doug McMillon, the company’s commitment is to “becoming a regenerative company—one that works to restore, renew and replenish in addition to preserving our planet, and encourages others to do the same” (Dearn, 2020). In addition to encouraging other corporations, these goals present a challenge to the government to take action on climate change. end student sample text

annotated text Extended Example as Evidence. The writer indicates where borrowed information from the source begins and ends, and cites the source in APA style. end annotated text

annotated text Source Citation in APA Style: One Author. The parenthetical citation gives only the year of publication because the author’s name is cited in the sentence. end annotated text

Objections to Taking Action

annotated text Heading. The centered, boldface heading marks the start of the writer’s discussion of potential objections to the proposed solutions. end annotated text

annotated text Body. The writer devotes two paragraphs to objections. end annotated text

student sample text Despite scientific evidence, some people and groups deny that climate change is real or, if they admit it exists, insist it is not a valid concern. Those who think climate change is not a problem point to Earth’s millennia-long history of changing climate as evidence that life has always persisted. However, their claims do not consider the difference between “then” and “now.” Most of the change predates human civilization, which has benefited from thousands of years of stable climate. The rapid change since the Industrial Revolution is unprecedented in human history. end student sample text

student sample text Those who deny climate change or its dangers seek primarily to relax or remove pollution standards and regulations in order to protect, or maximize profit from, their industries. To date, their lobbying has been successful. For example, the world’s fossil-fuel industry received $5.3 trillion in 2015 alone, while the U.S. wind-energy industry received $12.3 billion in subsidies between 2000 and 2020 (Green America, 2020). end student sample text

Conclusion and Recommendation

annotated text Heading. The centered, boldface heading marks the start of the conclusion and recommendation. end annotated text

annotated text Conclusion and Recommendation. The proposal concludes with a restatement of the proposed solutions and a call to action. end annotated text

student sample text Greenhouse gases can be reduced to acceptable levels; the technology already exists. But that technology cannot function without strong governmental policies prioritizing the environment, coupled with serious investment in research and development of climate-friendly technologies. end student sample text

student sample text The United States government must place its full support behind efforts to reduce greenhouse gasses and mitigate climate change. Rejoining the Paris Agreement is a good first step, but it is not enough. Citizens must demand that their elected officials at the local, state, and national levels accept responsibility to take action on both mitigation and adaptation. Without full governmental support, good intentions fall short of reaching net-zero emissions and cannot achieve the adaptation in attitude and lifestyle necessary for public compliance. There is no alternative to accepting this reality. Addressing climate change is too important to remain optional. end student sample text

Biello, D. (2007, May 25). Combatting climate change: Farming out global warming solutions. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/combating-climate-change-farming-forestry/

Bourzac, K. (2020, September 25). COVID-19 lockdowns had strange effects on air pollution across the globe. Chemical & Engineering News. https://cen.acs.org/environment/atmospheric-chemistry/COVID-19-lockdowns-had-strange-effects-on-air-pollution-across-the-globe/98/i37

Dearn, G. (2020, September 21). Walmart said it will eliminate its carbon footprint by 2040 — but not for its supply chain, which makes up the bulk of its emissions. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/walmart-targets-zero-carbon-emissions-2040-not-suppliers-2020-9

Green America (2020). Top 10 solutions to reverse climate change. https://www.greenamerica.org/climate-change-100-reasons-hope/top-10-solutions-reverse-climate-change.

Lomborg, B. (2020, July 17). The alarm about climate change is blinding us to sensible solutions. The Globe and Mail. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/article-the-alarm-about-climate-change-is-blinding-us-to-sensible-solutions/

Mulvaney, K. (2019, September 19). Climate change report card: These countries are reaching targets. National Geographic . https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/2019/09/climate-change-report-card-co2-emissions/

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (2020, November 24). Record-breaking Atlantic hurricane season draws to an end. https://www.noaa.gov/media-release/record-breaking-atlantic-hurricane-season-draws-to-end

Union of Concerned Scientists (2020). Climate solutions. https://www.ucsusa.org/climate/solutions

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (2020). Sources of greenhouse gas emissions. Greenhouse Gas Emissions. https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/sources-greenhouse-gas-emissions

U.S. Global Change Research Program (2014a). Melting ice. National Climate Assessment. https://nca2014.globalchange.gov/report/our-changing-climate/melting-ice

U.S. Global Change Research Program (2014b). Our changing climate. National Climate Assessment. https://nca2014.globalchange.gov/highlights/report-findings/our-changing-climate#tab1-images

annotated text References Page in APA Style. All sources cited in the text of the report—and only those sources—are listed in alphabetical order with full publication information. See the Handbook for more on APA documentation style. end annotated text

The following link takes you to another model of an annotated sample paper on solutions to animal testing posted by the University of Arizona’s Global Campus Writing Center.

Discussion Questions

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Authors: Michelle Bachelor Robinson, Maria Jerskey, featuring Toby Fulwiler

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Writing Guide with Handbook

- Publication date: Dec 21, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/6-4-annotated-student-sample-slowing-climate-change-by-shawn-krukowski

© Dec 19, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Environment Story Of The Day NPR hide caption

Environment

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

Transcript: Greta Thunberg's Speech At The U.N. Climate Action Summit

Climate activist Greta Thunberg, 16, addressed the U.N.'s Climate Action Summit in New York City on Monday. Here's the full transcript of Thunberg's speech, beginning with her response to a question about the message she has for world leaders.

"My message is that we'll be watching you.

"This is all wrong. I shouldn't be up here. I should be back in school on the other side of the ocean. Yet you all come to us young people for hope. How dare you!

"You have stolen my dreams and my childhood with your empty words. And yet I'm one of the lucky ones. People are suffering. People are dying. Entire ecosystems are collapsing. We are in the beginning of a mass extinction, and all you can talk about is money and fairy tales of eternal economic growth. How dare you!

'This Is All Wrong,' Greta Thunberg Tells World Leaders At U.N. Climate Session

"For more than 30 years, the science has been crystal clear. How dare you continue to look away and come here saying that you're doing enough, when the politics and solutions needed are still nowhere in sight.

"You say you hear us and that you understand the urgency. But no matter how sad and angry I am, I do not want to believe that. Because if you really understood the situation and still kept on failing to act, then you would be evil. And that I refuse to believe.

"The popular idea of cutting our emissions in half in 10 years only gives us a 50% chance of staying below 1.5 degrees [Celsius], and the risk of setting off irreversible chain reactions beyond human control.

"Fifty percent may be acceptable to you. But those numbers do not include tipping points, most feedback loops, additional warming hidden by toxic air pollution or the aspects of equity and climate justice. They also rely on my generation sucking hundreds of billions of tons of your CO2 out of the air with technologies that barely exist.

"So a 50% risk is simply not acceptable to us — we who have to live with the consequences.

"To have a 67% chance of staying below a 1.5 degrees global temperature rise – the best odds given by the [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change] – the world had 420 gigatons of CO2 left to emit back on Jan. 1st, 2018. Today that figure is already down to less than 350 gigatons.

"How dare you pretend that this can be solved with just 'business as usual' and some technical solutions? With today's emissions levels, that remaining CO2 budget will be entirely gone within less than 8 1/2 years.

"There will not be any solutions or plans presented in line with these figures here today, because these numbers are too uncomfortable. And you are still not mature enough to tell it like it is.

"You are failing us. But the young people are starting to understand your betrayal. The eyes of all future generations are upon you. And if you choose to fail us, I say: We will never forgive you.

"We will not let you get away with this. Right here, right now is where we draw the line. The world is waking up. And change is coming, whether you like it or not.

"Thank you."

- climate change

- greta thunberg

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, strategic gestures in bill mckibben's climate change rhetoric.

- 1 School of Communication Studies, James Madison University, Harrisonburg, VA, United States

- 2 Department of Communication Studies, University of Montana, Missoula, MT, United States

- 3 Department of Languages, Philosophy, and Communication Studies, Utah State University, Logan, UT, United States

- 4 School of Public Service, Boise State University, Boise, ID, United States

Although Bill McKibben is widely recognized as one of the leading strategists of the US climate change movement, several observers identify significant limitations to his approach to climate advocacy and politics. These criticisms are based on his reliance upon “symbolic gestures,” such as campaigns to promote fossil fuel divestment and stop fossil fuel infrastructure construction. In this essay we reconsider McKibben's work, drawing specifically on his speeches given in the US from 2013 to 2016 in support of the fossil fuel divestment campaign and campaigns attempting to block the construction of fossil fuel infrastructure, in order to show how McKibben's strategic orientation is grounded in a politics of gesture. His speeches provide a model for how to reconceive gestures and assemble them for political ends, and expand a sometimes narrow focus on policy mechanisms. Beyond the case of McKibben our analysis contributes the concept of strategic gestures to identify and theorize social movement interventions that have significant symbolic and material consequences.

Introduction

In 2006, author Bill McKibben found himself at “the end of my relatively quiet life as mostly a writer and the start of a hectic stint being mostly an activist” ( McKibben, 2016a ). McKibben had been speaking and writing about climate change since his 1989 publication of The End of Nature , one of the most influential books on climate change for a general audience. Despite growing scientific evidence and warnings about the climate crisis, there had been minimal political action and only modest grassroots activism on the issue, and McKibben was frustrated. “I wanted to do something. But there was no real climate movement to join” ( McKibben, 2016a ).

So McKibben set out to launch just such a movement. Starting with a march across his home state of Vermont, McKibben played a central role in a series of efforts to generate a large-scale, influential climate movement. In 2007, he and other organizers coordinated “Step It Up,” a set of climate events in over 1,400 communities in the US, intended as a call for Congressional action to reduce carbon emissions 80% by 2050. This network of activists subsequently formed 350.org, a 501(c)3 group in the US that connects and mobilizes climate activists around the world. Since then, McKibben has been a prominent voice in opposing the Keystone XL pipeline, fostering fossil fuel divestment campaigns, and orchestrating the 2014 and 2017 People's Climate Marches. His 2012 Rolling Stone article ( McKibben, 2012 ), “Global Warming's Terrifying New Math,” received over 14,000 online comments and was reproduced or hyperlinked thousands of times, “making it one of the most widely circulated online articles in Rolling Stone's history” ( Nisbet, 2013 , p. 47). The essay was a galvanizing rhetorical moment in the climate movement. As journalist Mark Hertsgaard (2014) put it, McKibben's efforts pushed “the threat of climate change into the mainstream American political agenda.” Communication scholar Matthew Nisbet acknowledges that McKibben is “arguably the most prominent climate change activist in the United States” ( Nisbet, 2013 , p. 41).

Although McKibben refers to himself as an “unlikely activist” ( McKibben, 2013a ) and resists the label of a movement leader, many observers claim that “he comes up with many of the big ideas about what to do, functioning as a—if not the—major strategist of the US climate change movement” ( Bronstein, 2014 ). Shortly after the 2014 Peoples Climate March, McKibben stepped down as executive director of 350.org, explaining that doing so would leave him “more energy and opportunity for figuring out strategies and organizing campaigns” ( Goldenberg, 2014 ) 1 . In turn, much of the scholarly analysis of McKibben focuses on the strategic dimensions and limitations of his work. For example, a multi-site study of the Step It Up (2007) events provides varying assessments of the efficacy of messages circulating across those sites ( Endres et al., 2008 , 2009 ). J. Robert Cox criticizes McKibben's approach to climate politics as failing to account for the strategic “considerations of effect” that can enable a movement to “contribute to a sustained influence” at the scale necessary to address a problem as significant as climate change ( Cox, 2009 , 2010 ).

Similarly, Nisbet, while acknowledging McKibben's influence, argues that his utopian rhetoric may appeal to the environmental base but has been unable to generate broad support or advance a viable political agenda. McKibben is more style than substance, argues Nisbet; his symbolic actions and political gestures, such as protests and non-violent civil disobedience, do not translate into “a pragmatic set of [policy] choices designed to effectively and realistically address the problem of climate change” ( Nisbet, 2013 , p. 3).

While noting merit in these critiques, we take a different approach to McKibben's work in order to propose an alternative mode of thinking about the strategic dimensions of climate activism and advocacy. Based on an analysis of McKibben's speeches, we offer the notion of strategic gestures as a concept to identify and theorize a rhetorical assemblage of movements, actions, and performances that have significant symbolic and material consequences. Whereas some critics use the label of gesture, or “gesture politics,” to dismiss particular interventions as empty, ineffectual, or “merely” symbolic, we contend that McKibben's speeches provide a model for how to reconceive gestures and assemble them strategically for political ends. In other words, we argue that McKibben's strategic orientation is productively considered in terms of a “politics of gesture.” Our analysis identifies four rhetorical actions that contribute to the strategic potential of gestures: promoting articulation and solidarity, interrupting dominant discourses, enacting alternative futures, and applying leverage at sites of decision making. In turn, the concept of strategic gestures provides scholars and activists alike with new insights into the relationship between rhetoric and social change.

In the subsequent analysis of McKibben's speeches, first we discuss McKibben's role as a strategist and speaker. Then we reconsider criticisms of McKibben made on strategic grounds. As noted above, both Cox and Nisbet argue that McKibben's strategies are inadequate to produce substantive change. In doing so, we review the concerns of those critics before developing our own interpretation of “the strategic” in McKibben's public address. In the third section we define and develop the concept of strategic gestures demonstrating how they can be utilized to build social movements and solidarity, interrupt dominant discourses, enact alternative futures, and apply leverage at local sites of decision making in order to produce wider systemic effects. In the fourth section we discuss practical implications of our analysis of strategic gestures focusing on their potential to produce social change. Finally, we conclude with some theoretical implications for scholars of environmental communication and social movement rhetoric. Ultimately, we present the concept of strategic gestures in order to account for and theorize how disparate acts of resistance and rhetorical interventions can be made to act in concert to produce social change and transform complex systems.

Bill McKibben, Strategist, and Speaker

Given McKibben's prominence, it is not surprising that scholars in environmental communication and related disciplines have closely analyzed his work ( Eckersley, 2005 ; Luke, 2005 ; Yearley, 2006 ; Cox, 2009 ; White, 2011 ; Merrill, 2012 ; Mitra, 2013 ; Nisbet, 2013 ; Ytterstad, 2015 ). However, most scholars have concentrated on his writing or his organizations rather than his speeches. Perhaps this is because McKibben's speeches and speaking style may not seem that notable. He began his 2015 Lannan Keynote Address at Georgetown University by confessing, “And what in some ways I would still most like to be doing…is thinking about things and writing them down.” He also drew attention to his lack of presentational polish by noting, “I may stumble a bit here and there” ( McKibben, 2015a ) 2 . He frequently makes such apologies, adopting humility to disarm and build trust with audiences, and his speeches contain incomplete thoughts, digressions, and apparent contradictions.

However, McKibben's oratory is significant for environmental communication in spite of its seeming lack of artistry. First, compared to his written works, which seek a general readership and rely upon familiar forms of environmental apocalyptic narrative and romanticism, McKibben's speeches are primarily addressed to those who already identify with the climate movement. Rather than minimize this type of rhetoric as simply “preaching to the choir,” we take it seriously as a means of promoting the “mobilization capacity” of the climate movement ( Brulle, 2010 ). When McKibben speaks to activists, he seems to understand that in order to be moved to further action, his audiences need to see how local actions will contribute to the larger goal of “solving” climate change.

Second, this audience-related constraint in the rhetorical situation leads McKibben to foreground his strategic thinking in his speeches. Whereas, his writings tend to focus on framing climate science for general audiences, his speeches provide a context and template for how climate activists might connect the local and the global, and the personal and the political, in ways that attract followers and advance the movement. Movement strategy is especially salient in the speeches we draw upon for our analysis: analyzing 11 publicly available speeches given by McKibben between 2013 and 2016, with particular attention given to his keynote address for the 2015 Lannan Symposium at Georgetown University. Several of these speeches were part of McKibben's 2012–2013 “Do the Math” tour, which sought to mobilize audiences around fossil fuel divestment and the keeping carbon in the ground campaign.

Third, these speeches reflect a moment in which the US climate movement was at a strategic crossroads. Hopes for strong climate action during the Obama administration were dashed by a weak agreement at the 2009 Conference of Parties meeting in Copenhagen and the failure of cap and trade legislation in 2010. However, in the years following, the climate movement also found reasons to be hopeful. In 2014, the rollout of the Clean Power Plan and the significant turnout for the People's Climate March suggested that public awareness was growing and policy action was not far behind. Also, President Obama vetoed legislation that would have forced construction of the Keystone XL pipeline to proceed, eventually denying the permit for its construction in 2016 3 . Thus, McKibben's speeches occur at a critical strategic moment for the US movement, and they can be interpreted as efforts to narrate the movement's successes and chart a path forward. Our findings may have even greater significance in the current period with its heightened political infighting, the US's exodus from global climate agreements, and the backsliding of federal environmental policy, making the need for strategic gestures even more pressing. At the end of this paper, we reflect on what McKibben's work, and our conceptualization of strategic gestures, might mean in the age of Trump.

Because of the compelling environmental rhetorical situation described above, especially the characteristics and motivations of the particular audiences, we chose to focus on McKibben's US speeches for this analysis. That noted, McKibben's work writ large is global and international in content and reach. His presentations reference environmental disputes and climate “wins” from around the globe. The Fossil Free: Divestment website shows activity from religious organizations, NGOs and governments from every continent other than Antarctica. Among those who divest are “some of the world largest pension funds and insurers, dozens of world-class universities, the world's largest sovereign wealth funds, the country of Ireland, major capital cities, as well as philanthropic foundations, health associations and world- renowned cultural institution” ( Hazan et al. ). Equally, the website for 350.org shows it having organizations that exist across the map ( https://350.org ). As is frequently noted by McKibben, each site has its own environmental issues, its own barriers, and its own points of leverage, varying the opportunities for strategic gestures by location.

Climate Advocacy and the Question of the Strategic

Cox advances his notion of “the strategic” as a heuristic for rhetorical invention in two essays that directly analyze McKibben and the Step It Up campaign ( Cox, 2009 , 2010 ). While that campaign appeared to generate interest among far-flung audiences around a consistent message, newly mobilized audiences were not organized to apply political pressure in support of the campaign's goals. Cox (2010) diagnoses the problem with this approach in terms of a faulty belief about how democratic political change takes place—in other words, a problem of strategy:

The implicit, strategic assumption seemed to be that, with news (and images) of enthusiastic and inspiring citizens sounding an alarm, more people would become informed and would—consistent with a democratic polity—rise up and demand that elected officials take necessary steps to protect our life-sustaining planet. (p. 127)

Cox's criticism lies less with the framing of Step It Up's messages or its awareness-raising efforts than with the failure to steer those efforts toward a consequential, systemic impact. This failure to align communication practices with opportunities to transform systems of power is at the heart of Cox's interest in “the strategic.” In his words, the notion of the strategic attempts to “account for communicative effects— how the application of a certain force, and the citizen mobilizations aligned with this, enable or initiate a process of events that influence larger effects within a system of power” ( Cox, 2010 , p. 131).

Nisbet shares Cox's interest in seeing more concrete political effects, but his major criticism lies with McKibben's alleged lack of pragmatism . He develops this argument in an in-depth white paper, tellingly titled “Nature's Prophet,” which surveys McKibben's influence as a “Journalist, Public Intellectual, and Activist” since The End of Nature ( Nisbet, 2013 ). Nisbet's central argument is that, “As a public intellectual, Bill McKibben has failed to offer pragmatic and achievable policy ideas;” throughout the paper, he consistently positions McKibben as having “little tolerance for political pragmatism” and clinging to the utopian values of deep ecology “rather than a pragmatic set of choices designed to both effectively manage the problem and to align a diversity of political interests in support of compromise” ( Nisbet, 2013 , p. 50–54). McKibben's moralistic rhetoric, his desire for small-scale agrarianism, his opposition to certain technologies, and his focus on symbolic acts of protest are marshaled by Nisbet as evidence of the narrow appeal of McKibben's activism. Furthermore, Nisbet argues that when faced with the failure of conventional policy proposals, McKibben refuses to adjust his strategy. “The response…from McKibben and other environmentalists has been to double-down in their commitment to their policy paradigm, attributing failure to the political prowess of conservatives and industry, and to a corresponding lack of grassroots pressure and moral outrage” ( Nisbet, 2013 , p. 50).

Nisbet's focus on pragmatism and Cox's focus on system transformation represent different approaches and assumptions with respect to what might make an intervention “strategic.” Nisbet's concerns emerge from a policy orientation rather than the social movement/pressure group perspective of Cox. Nisbet's (2014 ) critiques also represent an ecomodernist commitment to technological solutions to climate challenges, whereas Cox (2009) is more concerned with transforming the “complex whole” of economic, political, and ideological systems toward a low-carbon society. Likewise, while Cox (2010) is motivated by the need for “changes on the scale and timetable that climate and other system crises require” (p. 125), Nisbet (2013) favors incremental policy reforms; in his view, “breaking down the wicked nature of climate change into smaller, interconnected problems, achieving progress on these smaller challenges becomes more likely” (p. 51).

These differences illuminate some of the considerations and political visions that might inform strategic thinking in climate activism and environmental advocacy more generally. Cox and Nisbet's criticisms surface several key issues for strategizing about political and social change: what breadth and depth of social solidarity is needed to leverage change? To what degree should advocates challenge, or align with, dominant discourses, values, and interests? How do they craft a vision of the future that is both appealing and achievable? And where are the optimal sites for altering systems of power? Such questions are at the heart of strategic thinking about social change.

McKibben's speeches provide a distinctive set of answers to these questions. His take on the strategic is less dismissive of the role of so-called “symbolic” politics than Nisbet's, and his turn toward divestment arguably reflects greater attention to contingent openings in systems of power than was displayed in the Step it Up campaign, which Cox took issue with. Cox's focus is on leverage in economic and energy systems, perhaps at the expense of attention to the ideological and political systems that may also contribute to social and policy change. Strategic gestures, as deployed by McKibben, articulate how economic, political, and ideological systems can be leveraged in concert with each other to produce change. His approach is captured well by Engler and Engler (2013) , who argue that “if they are to spark mass movement, campaigns must be built with symbolic as well as instrumental considerations in mind; they must achieve outcomes that perpetuate further movement-building, even if they do not immediately advance a given policy goal” (online). McKibben's enactment of this principle is a significant instance of this move in social movement strategizing. We argue that it can be productively theorized as a politics of gesture that is orchestrated rhetorically through the assemblage of strategic gestures.

Strategic Gestures

The concept of gesture has traditionally been considered an adjunct to speech and associated with the canon of delivery in the study of rhetoric. However, some rhetoricians are rethinking gestures as part of a broader interest in body rhetoric and its inventional possibilities. Scholars such as Debra Hawhee and Cory Holding recuperate theories that explain how gestures give shape to speech and facilitate connections between bodies, rather than functioning as mere ornaments to rational discourse. Hawhee's (2006 ) reading of Sir Richard Paget, for example, identifies the mimetic and contagion-like character of gesture that not only moves a body to speech, but also facilitates communion with others. “The ability for those movements to ‘catch on' across bodies helped him account for the spread and resulting ‘staying power' of language. Put still more simply, speech gestures are communicative because they are both communicable and communal” (p. 335). Likewise, Holding (2015) re-reads John Bulwer's famed gesture manuals as what could be called a body-positive theory of invention, suggesting that contemporary rhetoricians can use Bulwer to “offer a theory of how gestures communicate, attitudinize, and forge pathways to listening, mutual acknowledgment, and identification” (p. 416).

The generative role of gestures heightens their significance as means for conserving or resisting established relations of power. Hariman (1992) , for example, illustrates how the courtly style relied on the “displacement of speech by gesture” as a form of “social control that makes the decorous body the sign of order” (p. 160). Conversely, Olson and Goodnight (1994) use the social controversy over fur to identify “gestures that widen and animate the non-discursive production of argument” as oppositional rhetorical strategies (p. 252). In their view, “non-discursive arguments work—in the new, ‘free' space of reassociation—to redefine and realign the boundaries of private and public space” (p. 252). More broadly, Phaedra Pezzullo calls attention to the importance of bodies and non-linguistic acts as components of cultural performances that critically interrupt dominant discourses and contribute to “the rhetorical force of counterpublics” ( Pezzullo, 2003 , p. 361).

These perspectives on the inventional and oppositional possibilities of gesture complicate any easy dismissal of gestures and their relevance to politics and social movements. Cambridge Dictionary 4 (online) defines “gesture politics” as “any action by a person or organization done for political reasons and intended to attract attention but having little real effect.” Similarly, Christopher Caldwell (2005) notes, “The expression ‘gesture politics' generally describes the substitution of symbols and empty promises for policy.” In contrast, other critical and cultural theorists position gesture as an important concept for theorizing power and resistance in ways consistent with Pezzullo's perspective. Lindsay Reckson (2014) explains that “cultural studies scholars have understood gesture as both communicative and performative ; gestures can express semantic content, but they can also enact (and reenact) cultural histories, identities, and commitments.” Scholars of performance and performativity, she adds, formulate gestures as “movements that produce, reproduce, and potentially interrupt embodied structures of power” (online). Building on this definition of gesture, we advance the notion of strategic gestures as a rhetorical assemblage of movements, actions, and performances that are intended to generate effects larger than a sum of individual or particular acts in systems of power . This approach to gestures embraces not an empty “gesture politics,” but a politics of gesture that takes seriously the political possibilities of certain kinds of gestures.

This conception of strategic gestures emphasizes the rhetorical processes through which gestures become strategic. Importantly, our plural description suggests that gestures are not necessarily strategic in isolation. Gestures become strategic when they are made to complement and amplify each other to effect systemic change. Because economic, political and ideological systems function in concert with each other to produce, in Cox's (2009 ) words “a complex whole articulated in dominance and resistant to change,” transforming systems necessitates multiple gestures designed to leverage change across the whole (p. 399). Such gestures might include traditional symbolic interventions such as speeches, image events, and protests, and they might include material interventions such as the installation of renewable energy, the use of electric cars, and the divestment of institutional funds from fossil fuel industries. Each of these actions may be perceived as little more than a symbolic gesture, but when assembled together they can function as strategic gestures to produce social movement and systemic change.

The rhetorical actions accomplished through gestures provide another means for considering how gestures become strategic. Our analysis of McKibben's speeches identifies four types of rhetorical action that contribute to the strategic potential of gestures. First, strategic gestures can facilitate articulation , linking different and dispersed groups, causes, and issues to generate social solidarity ( Laclau and Mouffe, 1985 ; Greene, 1998 ; DeLuca, 1999 ; Stormer, 2004 ; Peeples, 2011 ). As Brian Massumi (2015) puts it, “The gesture is a call to attunement. It is an invitation to mutual inclusion in a collective movement” (p. 105–106). Second, strategic gestures can interrupt dominant discourses ( Pezzullo, 2001 ) and “usher into the public realm aspects of life that are hidden away, habitually ignored, or routinely disconnected from public appearance” ( Olson and Goodnight, 1994 , p. 252). Third, strategic gestures can enact and display alternative futures . Massumi (2015) identifies how gestures are both affective, “felt as directly as they are thought,” and speculative, as they “convoke potential and carry alternatives” (p. 207). Strategic gestures capitalize on this to display new modes of being and action as possible and desirable. Fourth, strategic gestures can apply leverage at sites of decision making to alter systems of power relations. Even as the performative and affective power of gestures may signal cultural change, Cox's notion of the strategic helps us consider how gestures produced at the right time in the right place can leverage systemic change.

Assembling Gestures in McKibben's Speeches

McKibben's speeches lean heavily on the scenic construction, first articulated in “Global Warming's Terrifying New Math,” of a melodramatic climate “battle.” In that piece, McKibben squarely positions the fossil fuel industry as “Public Enemy #1” in a battle over the public interest. His Lannan keynote surveys the scene of climate politics as “maybe the most important pitched battle in human history” ( McKibben, 2015a ). The battle is urgent; there is no time for gradualist, market-driven, evolutionary social change. Instead, he argues, “We get, if we get anything, the difficult change that is won by winning power. And for that power to be won, we need a set of weapons that work to our advantage. We can't win it with money, because they have more of it than we do. They have more than anybody” ( McKibben, 2015a ). Because the “other side” has more money “and hence controls more political leverage,” the battle must be fought using non-traditional political means ( McKibben, 2015a ).

This scenic construction opens a space for McKibben to talk about the kinds of interventions that we are calling “strategic gestures.” Because traditional avenues for enacting policy change are closed, McKibben (2015a) makes a case for the creative use of symbolic actions. “Our weapons,” he argues, “have to be the other ones. Passion, spirit, creativity, um, um, our bodies.…The role of the imagination in these fights.” There are two important aspects of McKibben's discussion of symbolic weapons that inform our theorizing of strategic gestures.

First, McKibben (2015a) constitutes the battle as a contest of momentum in which each side attempts to demonstrate what will be inevitable: “It's a particular kind of fight…It's a battle for momentum. A battle for winning the sense of what's inevitable or not. What's the world going to look like. And that battle is, well—that's everything.” Here McKibben lays bare how the climate “battle” is a contest for ideological hegemony, for commonsense understandings not about what the future should look like, but about what it will look like. McKibben's battle lines resonate with Massumi's (2015 ) observation that, “capitalism hardly bothers to assert its rationality any more, contending itself with creating the affective ‘fact' of its inevitability” (p. 111). McKibben's symbolic weapons, then, are utilized both to challenge the affective “fact” of a fossil fuel economy and call an alternative future into being.

Second, the contest for the cultural commonsense about the future is fought with a series of gestures over an extended period of time. In his Lannan speech, for example, argues:

In a fight like that—and here's maybe the crucial word for me for this talk—in a fight like that, each gesture becomes essential. There's a kind of, um, fight of gestures, of images that are brought forward, and, and, and each time a gesture is made, each time—well, each time there's a new solar roof top, that's the kind of easy and obvious one—but each time there's a divested college, or even a strong, beautiful movement for it on a college, um, um, that sense of what's going to happen begins to shift McKibben (2015a) .

In other words, each gesture in the fight for momentum contributes to a larger goal. Social change is produced not in one fell swoop, but over an extended period of time. As such, gestures should not be viewed in a vacuum, but as part and parcel of an extended effort to build solidarity, enact a vision of a low-carbon future, and effect systemic change.

Articulating Solidarity

In almost every speech, McKibben registers a litany of successes related to climate change: acts of individuals and groups, government policies, or technological advances. During a speech in Brooklyn, before the 2016 Climate Talks in Paris, McKibben rallies:

No kidding, no kidding, this is powerful! I mean, look, that one mine that Charlie was talking about. A year ago we were pretty sure it was going to get built, and if it had been, it would have, just that one valley, put 5% of the carbon in the atmosphere necessary to take us past two degrees. One mine. If they have stopped it, same thing all over the world. It's not as if any of us started this movement. Local people, often indigenous people, in defending their land against intrusion for many years. More and more, more and more [clapping]—more and more, they've been winning. Look, in India, fishermen, farmers in the village of Sompeta. They waged a 5-year battle to keep this giant coal mine from destroying their town. Now, they won. They won at the cost of three activists being killed along the way, but they won. South Africa, intense pressure in the last months from local activists persuaded [a] big company, GDF Suez, to pull support for the new coal plant at Thabametsi. We're starting to win.

( McKibben, 2015c )

In other speeches, McKibben includes the Galilee Basin in Australia ( McKibben, 2015b ), Copenhagen and the Tar Sands in Canada ( McKibben, 2015d ), rooftop solar panels ( McKibben, 2013b ), the trial of the Delta 5, and the Lummi Nation and kayaktivists ( McKibben, 2016b ), among many other acts of resistance.

Discussing climate change movement strategies, but also providing insight into his rhetorical tendencies, he states: “There is no one answer to climate change. There is no silver bullet. There may be enough silver buckshot if we gather it all up” ( McKibben, 2013b ). By gathering the buckshot, McKibben is not only providing a sense of momentum; he is also articulating and building solidarity and affiliation with the climate cause.

Massumi's description of gesture as a call to attunement resonates with the concept of articulation as it has been developed in communication scholarship. In particular, it is similar to DeLuca's (1999 ) turn to articulation to interpret the enacted resistance of environmental activism. Articulation is typically understood as a linking of disparate elements that modifies their meaning. This linkage produces “chains of equivalence,” where those elements are constituted as signs of some larger phenomenon and evidence of domination; “each link in the chain remains distinct, but they operate together, in concert…around an agenda of equivalence” ( Purcell, 2009 , p. 159). From this perspective, articulation and chains of equivalence explain how social movements coordinate diverse struggles against hegemonic relations of power.

Although articulation is often associated with the linkage of demands into chains of equivalence, McKibben's rhetoric suggests that chains of equivalence also can be built by linking gestures. Two chains of equivalence are especially significant in McKibben's articulation of climate-related gestures. First, he links seemingly individualistic acts of consumption with collective political activity 5 . For example, in the quote from the Lannan speech above, McKibben compares the gesture of a new solar rooftop to that of a divested college or “even a strong, beautiful movement for [divestment].” In doing so, McKibben not only interpellates individual consumers as part of a collective political struggle, “the fossil fuel resistance,” but also calls attention to the political struggles that are necessary to enable such consumer choices. For example, when accused of not doing enough to support renewable energy policies by a questioner at Columbia University, McKibben folds that work into the “silver buckshot” analogy: “And the part you're talking about [creating policy] is an important part, and a part that people are deeply engaged in all throughout the country that I know of, certainly, every place I go” ( McKibben, 2013b ).

Second, McKibben articulates gestures to help his audience understand that although each gesture has a unique context, together they represent a global movement constituted in solidarity. For example, in the Lannan speech ( McKibben, 2015a ), he describes the Cowboy/Indian alliance, an action in which ranchers, farmers, and tribal communities joined together in Washington, DC, to protest the Keystone XL Pipeline. He encourages his audience to “[t]hink of the power of that gesture with the sort of two of the great romantic, um, um, forces in American history, no longer in opposition but together” ( McKibben, 2015a ). He also links divestment campaigns at Harvard, Stanford, the University of the Marshall Islands, and Swarthmore, the 2014 People's Climate March, the blockade of the world's largest coal port in New Castle, Australia, and Pope Francis' “soon-to-be-released” encyclical on the environment as akin to a “series of gestures with which his papacy has, um, unfolded. Kneeling down to kiss the feet of prisoners…Out amongst the poorest, um, much as he can be” ( McKibben, 2015a ). Here he calls upon his audience to see this “series of gestures” as “helping people re-discover some sense of solidarity with the rest of the world.” He describes organizing senior citizens to engage in civil disobedience to stop the Keystone XL pipeline, and provides the following illustration of an individual act from that event: “And on the last day there was a guy arrested with a sign around his neck that said, ‘World War II vet, handle with care”' ( McKibben, 2015a ).

McKibben's articulation of gestures creates a chain of equivalence across a wide geographic and demographic terrain, constituting solidarity amongst diverse activists around the world. Such a perspective resonates with Robert Asen's (2017 ) discussion of “the prospects for resistance to a neoliberal public through the coordinated action of networked locals” (p. 3). From “Cowboys” and “Indians” to Harvard and the Pacific Islands, McKibben links locals and their gestures in a chain of equivalence, describing the fossil fuel resistance as “spreading in every direction around the world, almost as sprawling and protean in its form as the fossil fuel industry itself” ( McKibben, 2015a ). Although McKibben articulates diverse gestures as comprising the fossil fuel resistance, he does not deny the uniqueness of each gesture. They remain distinct, but the gestures operate together, constituting a movement based on “open-source organizing” in dispersed locales. As McKibben explains with regard to the divestment movement, “everybody knows, in their own place, how best to do it” ( McKibben, 2015a ), (see also Sprain et al., 2009 ).

Each gesture may be vulnerable to critics' claims of it being fanciful, utopian, idealistic, individualist, self-serving or irrational. But McKibben does not leave them as isolated acts to be evaluated in their singularity. He piles up gestures to direct audience attention toward a new future, one that is not dictated by fossil fuel companies, but by the goal-driven actions of diverse organizations and individuals.

Interrupting Inevitability, Enacting a New Future

Critical theorists have long noted that bodily gestures do more than provide semiotic content; they are also the site or “citations” of culture, discipline, and power on the body. From Walter Benjamin's (1968 ) analysis of Brecht's epic theater to Judith Butler's (1990) explication of performative bodies, theorists have established the power of gestures to interrupt the commonplace. “Interrupting gestures,” Benjamin argues, “alienate” audiences from the existing “conditions of life” (p. 150). Similarly, Massumi (2015) contends that “resistance is of the nature of a gesture ” (p. 105). In McKibben's rhetoric, gestures are capable of puncturing the illusion of a preordained future underwritten by fossil fuels. For McKibben, the carbon economy is not simply a brute fact of infrastructure, but rather a relentlessly rhetorical effort to shape public perception of the way things are and always will be, an ideology—a set of beliefs that naturalize a particular set of market and social relations:

The battle, in the end, in this case, is for control of the zeitgeist, for control of how we think about the world, okay? Our sense of what is going to happen. And the other side understands that exquisitely. It's why the fossil fuel industry spends all their time trying to promote the inevitability of continuing down the current path.

( McKibben, 2015a )

McKibben uses gestures to challenge that sense of inevitability. He interprets actions that run counter to the business-as-usual path as gestures that confound this commonsense. “Each time a gesture is made… that sense of what's going to happen begins to shift ” ( McKibben, 2015a ; emphasis added). Multiple gestures build on one another to create a sense of movement and momentum that belies the fossil fuel industry's rhetoric of certitude. McKibben continues, “There's an almost mathematical sense of, of, of, gestures piling up on one side or the other, giving strength to one side or the other” ( McKibben, 2015a ).

McKibben's use of gesture is consistent with Massumi's emphasis on gesture as enactment. When he claims that resistance is gestured into existence and functions as immanent critique, he is suggesting that the exemplary power of gestures enacts alternative modes of engaging the world and invites others to participate, paradoxically altering the course of inevitability. For example, McKibben interprets the Rockefeller family's decision to divest from fossil fuels on the eve of the first People's Climate March as unique, but also as exemplary, as symbolic of an imminent cultural shift:

But just think about what that means. That the first great fossil fuel fortune had now recognized that the moment had come to switch, and the power of that was palpable. Um, it was the beginning of the end of the fossil fuel age that day, between that huge march and that announcement, and the question only is how quickly, how quickly we will make that end come, and whether it will come in time 6 .

( McKibben, 2015d )

This “palpable” switch resonates with Massumi's (2015) reference to C.S. Peirce's notion of “abduction,” or, “thought that is still couched in bodily feeling” to explain the exemplary power of gesture (p. 9–10). Massumi argues gestures of resistance “are thought in the immediacy of enactment,” which elicit affective response in conjunction with thought (p. 207). This way of considering gestures is consistent with the affective, contagion-like approach that Hawhee interprets in Paget, a theory that “figures speech as a bodily, mimetic, even affective art, thereby imagining bodily feeling, gesture, and posture as unconsciously contagious and iterable movements” ( Hawhee, 2006 , p. 336).

This affective quality of gestures, as communicable thinking-feelings in the process of becoming, means that gestures of resistance do not exactly make arguments for an alternative future; rather, they enact different ways of relating and orienting to the world, and thus gesture toward an alternative future. In envisioning a new future for the planet, McKibben differentiates between the vision put forth by the fossil fuel industry and the one that must be called forth by climate activists. “Their job is to make the status quo seem inevitable; our job is to the make the future, the change seem inevitable, and possible, and to get there. Creativity is the absolute most important thing in this fight” ( McKibben, 2015a ). In turn, McKibben emphasizes that “proper gestures, good gestures” are “beautiful, artistic moments” that enable “you to see behind them powerful truths” ( McKibben, 2015a ). For example, with respect to renewable energy, his alternative future integrates the material realities of innovation and engineering with romantic notions of beauty:

The engineers allow us to imagine; if the scientists tell us that we need a fossil freeze, the engineers allow us to imagine a solar farm, and also wind power and the other things that come quickly with it. But to imagine a solar farm, to imagine in the process of doing that, not just a world that might be able to keep from going over, but, but also a world that might work in many ways much more beautifully than the one we live on now.

Part of the beauty of this future is that it is more equitable, as power shifts from fossil fuels which divert wealth into the hands of a few, to a system of energy that rebalances power because of the diffusion of the sun and the wind:

That's the beginning of a different kind of world. So there is real possibility here. A glimmer of possibility. The fortifying thing, given that glimmer, is to see how little we are doing given that maybe an ember is the right, um, message, is the right image, to see how little we are doing to, to blow it into life, to make it spark, to make it spread, to make it blaze, to make it blow up into something big enough to light the world.

This vision may be fodder for criticisms such as Nisbet's—that McKibben relies too heavily on symbolic acts of resistance and romantic and utopian visions of the future. However, these criticisms fail to consider two things. First, that a utopian impulse plays an important role in social movement rhetoric enabling both a reconstructive vision and a reconstructive praxis. In this regard a utopian impulse includes both “critique of existing conditions and a vision of a reconstructed program for a new society” (Dan Chodorkoff, 1983 , see also Jameson, 1981 ). This reconstructive vision need not be limited to literary and philosophical blueprints; when it takes the form of a social movement, it can function as a praxis for concrete social change. Gestures for McKibben, then, function as both immanent critique and indexes of an unfolding inevitable social change, and as a vision for what that change can bring. Second, critiques of McKibben's utopian impulse fail to consider the “pragmatic capacities” of gestures to leverage systems to “achieve tangible effects” ( Foust, 2017 , p. 65).

Leveraging Systems

According to Mohan Dutta (2011) , “the performance of social change is fundamentally directed at articulating change through the disruption of structures” (p. 212). Strategic gestures can enable such articulations. To the extent that gestures are composed with an eye toward vulnerabilities and opportunities within systems of power, they can leverage systemic change. From this perspective, gestures become increasingly strategic as they locate sites for applying leverage to alter a system.

In his speeches and during question and answer periods, McKibben justifies several “symbolic” climate actions by arguing that such gestures are also material interventions intended to alter economic systems or apply political pressure. When one audience member asks him to explain how symbolic gestures are going to create “real” material change, McKibben (2015a) dismantles that distinction: “So let's look at Keystone as an example. It is a symbol, but it's only an effective symbol because it is real, okay?” As a result of the delays created by the campaigns to stop the pipelines, “They're already falling into huge difficulty; the expansion plans to triple and quadruple the draw in the tar sands” is “not gonna happen” ( McKibben, 2015a ). Similarly, when addressing Seattle “kayaktivists” who banded together to blockade fossil fuel infrastructure from leaving port, McKibben (2016b) refers to related efforts in nearby communities as taking advantage of “choke points by which we can stick a cork in the fossil fuel bottle. … If they don't, can't build the port at Cherry Point, and they can't build the port at Longview, then they're not gonna mine the coal in Montana and Wyoming. It's gonna stay underground, alright?”

McKibben's “choke points” discussion mirrors Cox's analysis of the Sierra Club's Beyond Coal campaign, in which he describes the strategic in terms of applying leverage at local sites of decision in order to alter systems of power. For Cox (2010) , this requires that a campaign create “strategic alignment of mobilization and its mode of influence or leverage that can enable wider outcomes or effects” (p. 128). These effects do more than disrupt structures and systems; they literally alter them. Project delays and denied permits are not only symbolic victories, which open space for articulation as Dutta suggests; they also have material, economic effects by producing signals in financial markets to shift investment to renewable energy. Such shifts can reduce the power of the fossil fuel industry and enable more alterations to the built environment that can further influence perceptions of inevitability.

Gestures also provide activists with opportunities to articulate policy agendas and apply leverage in transformed arenas of political discourse. Explaining how the divestment movement successfully influences public discourse, McKibben (2016b) avers: “And now it's not, you know, me in Rolling Stone . Now it's the head of the IMF, the head of the World Bank. It was the head of the Bank of England talking to the world's insurance industry” about the fact that they are “overexposed to what are going to be stranded assets from a carbon bubble.” Strategic gestures can intervene in systems of power by altering the symbolic field and reaching new audiences. McKibben identifies this function of gestures with respect to divestment. “If we can continue this divestment fight, we can call it symbolic if you want, but its huge effect has been to make it far more difficult for people to raise capital to do what they're gonna do” ( McKibben, 2015a ). Here McKibben effectively dissolves the symbolic/material distinction by positioning divestment as a gesture that has both symbolic and material effects.

In this way, gestures contribute to a strategy for social change that aligns with time-honored functionalist approaches to social movement organization and resource mobilization ( Simons, 1970 ): a strategy designed to bring the other side to the bargaining table. For example, McKibben explains how the piling up of gestures can create conditions that are amenable to policy changes:

We're going to have to impose that [carbon] tax in all the ways we can by making it difficult for business as usual to go on. And when we break their power some, then we'll get some kind of carbon tax, you know. They'll start to sue for peace, and we'll see what happens, but in the meantime that's our job. Their job is to make the status quo seem inevitable, our job is to make the future, the change seem inevitable, and possible and to get there.

Gestures can be strategic, then, to the extent that they integrate efforts at ideological transformation with opportunistic intervention in political and economic systems. In McKibben's (2015a ) words, “You want to pick things that have real outcome, and that'll also produce this change in the sense of inevitability, and the zeitgeist, because, you know, control of the zeitgeist is an important asset. It's, you know, in some ways the most important asset.”

Practical Implications

To this point we have argued that strategic gestures can have multiple rhetorical effects. But do such gestures “work?” Under what conditions might strategic gestures be more likely to achieve the kinds of effects that McKibben describes? Some observers have already posed such questions in relation to McKibben's work, specifically with respect to divestment. As Schneider et al. (2016) have argued, “The rhetorical power of divestment, therefore, lies in the movement's ability to change the terms of public discourse about fossil fuel production and incite more discourse about climate change from new and potentially powerful rhetorical audiences” (Schneider et al., p. 122). This argument is bolstered by Schifeling and Hoffman's (2017 ) research which demonstrates that McKibben and 350.org's divestment campaign “expanded the spectrum of the climate change debate and shifted its central focus” via a “radical flank effect,” whereby radical issues enter into a polarized and seemingly intractable debate to disrupt the field of discourse enabling “previously marginalized liberal policy ideas such as a carbon tax and carbon budget to gain greater traction in the debate” (p. 16).

However, our explanation of strategic gestures suggests a more complex account and a more mixed evaluation of the apparent “success” of the divestment campaign. On one hand, divestment activism may have disrupted the prevailing common sense on climate change, reconfigured relationships between activists and financial firms and investors, and created discursive space for discussing a carbon tax. McKibben (2016c) himself understands gestures as creating that space, and he sees such a tax as a necessary but not sufficient gesture toward an alternative future. At the same time, these productive interventions in “the zeitgeist” do not necessarily ensure policy victories, and the jury is still out as to whether the campaign will achieve the same success as other divestment campaigns, such as those around tobacco and South African apartheid.

More broadly, it is worth considering how an assemblage of strategic gestures might influence climate politics under a radically different US presidential administration. Regulatory rollbacks, the withdrawal from the Paris Agreement, and the gutting of agencies focused on climate change all interrupt McKibben's buoyant rhetoric of inevitability. This elevates a potential tension between the locus of inevitability that is so central to McKibben's rhetoric, and the locus of the irreparable that is one of Cox's significant contributions to the study of environmental communication ( Cox, 1982 ). For instance, it would be easy for activists today to despair of the rapid dismantling of climate research and Obama-era climate regulations under President Trump's administration, question McKibben's utopian invocations of inevitability, and embrace apocalyptic rhetoric that urges audiences to take extraordinary measures to forestall loss. The latter could be persuasive for McKibben's choir and the 21% of US residents who occupy the “Alarmed” category in Yale's Six Americas research as of March 2018—the largest proportion in the history of that survey ( Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, 2018 ). The blithe dismissal of the climate challenge by the Trump administration creates a situation that is ripe for appeals to the irreparable.