- Literary Terms

- Definition & Examples

- When & How to Use Irony

I. What is Irony?

Irony (pronounced ‘eye-run-ee’) is when there are two contradicting meanings of the same situation, event, image, sentence, phrase, or story. In many cases, this refers to the difference between expectations and reality.

For example, if you go sight-seeing anywhere in the world today, you will see crowds of people who are so busy taking cell-phone pictures of themselves in front of the sight that they don’t actually look at what they came to see with their own eyes. This is ironic, specifically, situational irony . This one situation has two opposing meanings that contradict expectations: (1) going to see a sight and prove that you were there (2) not enjoying the thing you went to see.

Irony is often used for critical or humorous effect in literature, music, art, and film (or a lesson). In conversation, people often use verbal irony to express humor, affection, or emotion, by saying the opposite of what they mean to somebody who is expected to recognize the irony. “I hate you” can mean “I love you”—but only if the person you’re saying it to already knows that! This definition is, of course, related to the first one (as we expect people’s words to reflect their meaning) and in most cases, it can be considered a form of sarcasm.

II. Examples of Irony

A popular visual representation of irony shows a seagull sitting on top of a “no seagulls” sign. The meaning of the sign is that seagulls are not allowed in the area. The seagull sitting on the sign not only contradicts it, but calls attention to the absurdity of trying to dictate where seagulls may or may not go, which makes us laugh.

Another example is a staircase leading up to a fitness center, with an escalator running alongside it. All the gym patrons are using the escalator and no one is on the stairs. Given that this is a fitness center, we’d expect that everyone should be dedicated to health and exercise, and so they would use the free exercise offered by the stairs. But instead, they flock to the comfort of the escalator, in spite of the fact that they’ve come all this way just to exercise. Once again, our expectations are violated and the result is irony and humor.

Aleister Crowley, a famous English mystic of the early twentieth century, who taught that a person could do anything if they mastered their own mind, died of heroin addiction. This is ironic because the way he died completely contradicts what he taught.

III. The Importance of Irony

The most common purpose of irony is to create humor and/or point out the absurdity of life. As in the all of the examples above, life has a way of contradicting our expectations, often in painful ways. Irony generally makes us laugh, even when the circumstances are tragic, such as in Aleister Crowley’s failure to beat his addiction. We laugh not because the situations were tragic, but because they violate our expectations. The contrast between people’s expectations and the reality of the situations is not only funny, but also meaningful because it calls our attention to how wrong human beings can be. Irony is best when it points us towards deeper meanings of a situation.

IV. Examples of Irony in Literature

In O. Henry’s famous short story The Gift of the Magi , a husband sells his prized watch so that he can buy combs as a gift for his wife. Meanwhile, the wife sells her beautiful hair so she can buy a watch-chain for her husband. The characters ’ actions contradict each other’s expectations and their efforts to give each other gifts make the gifts useless.

Edgar Allen Poe’s The Cask of Amantillado is full of verbal and situational irony, including the name of the main character. He’s called Fortunato (Italian for “fortunate”), in spite of the fact that he’s extremely unlucky throughout the story.

Water, water everywhere, nor any a drop to drink.

This line from Samuel Coleridge’s “Rime of the Ancient Mariner” describes the dark irony of a sailor dying of thirst on his boat while he is surrounded by water.

V. Examples of Irony in Pop Culture

Alannis Morisette’s popular song “Ironic” contains such lyrics as:

Rain on your wedding day A free ride when you’ve already paid Good advice that you just didn’t take

These are not examples of irony . They’re just unfortunate coincidences. However, the fact that her song is called “Ironic” and yet has such unironic lyrics is itself ironic. The title contradicts the lyrics of the song. It isn’t, so your expectations are violated.

In Disney’s Aladdin , Aladdin wishes for riches and power so that he can earn the right to marry Princess Jasmine. Thanks to the genie’s magic, he gets all the wealth he could ask for and parades through the streets as a prince. But, ironically, this makes him unattractive to the princess and he finds himself further away from his goal than he was as a poor beggar. In this case, it’s the contrast between Aladdin’s expectations and results which are ironic.

Related terms

Sarcasm is a kind of verbal irony that has a biting or critical tone, although it can be used to express affection between friends It is one of the most common forms of irony in fiction and in real life. We’ve all heard people use verbal irony to mock, insult, or poke fun at someone or something. For example, here’s a famous sarcastic line from The Princess Bride :

Truly, you have a dizzying intellect.

In the scene, Wesley is insulting the intelligence of Vizzini the Sicilian using verbal irony (the word “truly” makes it even more ironic, since Wesley is reassuring Vizzini of the truth of an untrue statement). The line is both ironic and mean, and therefore it’s sarcastic . One needs to be a little careful with sarcasm, since you can easily hurt people’s feelings or make them angry.

List of Terms

- Alliteration

- Amplification

- Anachronism

- Anthropomorphism

- Antonomasia

- APA Citation

- Aposiopesis

- Autobiography

- Bildungsroman

- Characterization

- Circumlocution

- Cliffhanger

- Comic Relief

- Connotation

- Deus ex machina

- Deuteragonist

- Doppelganger

- Double Entendre

- Dramatic irony

- Equivocation

- Extended Metaphor

- Figures of Speech

- Flash-forward

- Foreshadowing

- Intertextuality

- Juxtaposition

- Literary Device

- Malapropism

- Onomatopoeia

- Parallelism

- Pathetic Fallacy

- Personification

- Point of View

- Polysyndeton

- Protagonist

- Red Herring

- Rhetorical Device

- Rhetorical Question

- Science Fiction

- Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

- Synesthesia

- Turning Point

- Understatement

- Urban Legend

- Verisimilitude

- Essay Guide

- Cite This Website

What Is Irony? Definition, Usage, and Literary Examples

Irony definition.

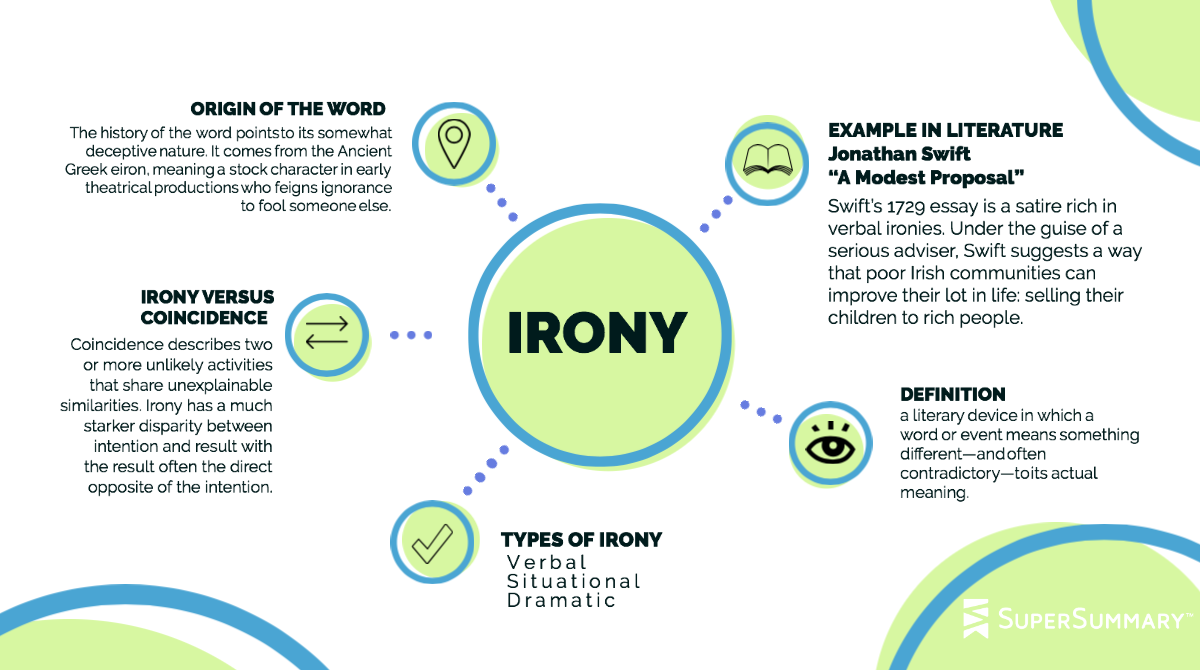

Irony (EYE-run-ee) is a literary device in which a word or event means something different—and often contradictory—to its actual meaning. At its most fundamental, irony is a difference between reality and something’s appearance or expectation, creating a natural tension when presented in the context of a story. In recent years, irony has taken on an additional meaning, referring to a situation or joke that is subversive in nature; the fact that the term has come to mean something different than what it actually does is, in itself, ironic.

The history of the word points to its somewhat deceptive nature. It comes from the Ancient Greek eiron , meaning a stock character in early theatrical productions who feigns ignorance to fool someone else.

Types of Irony

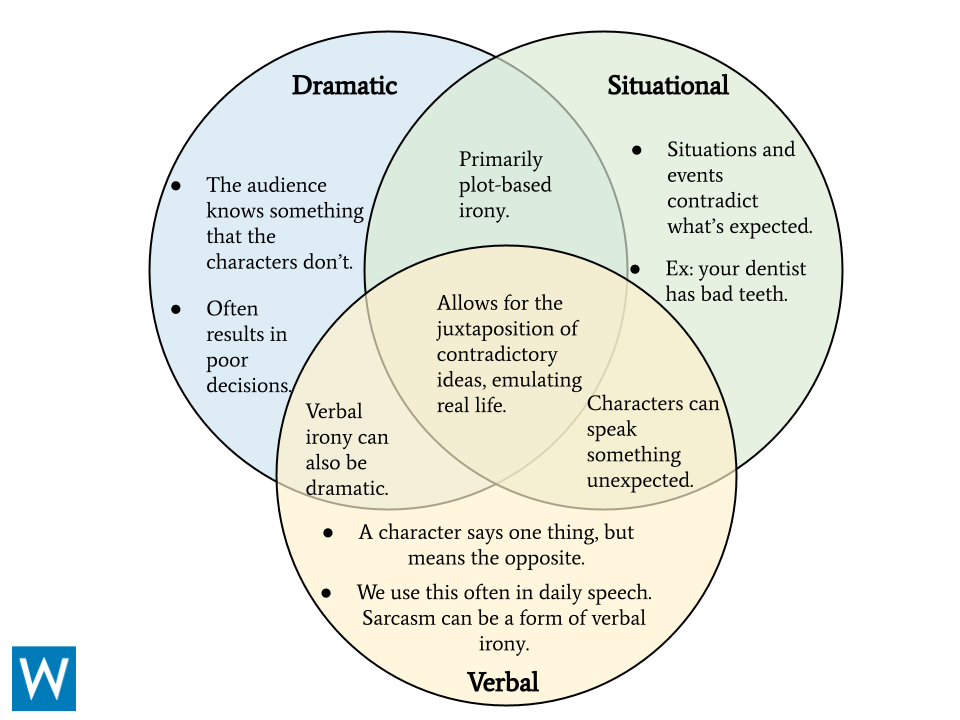

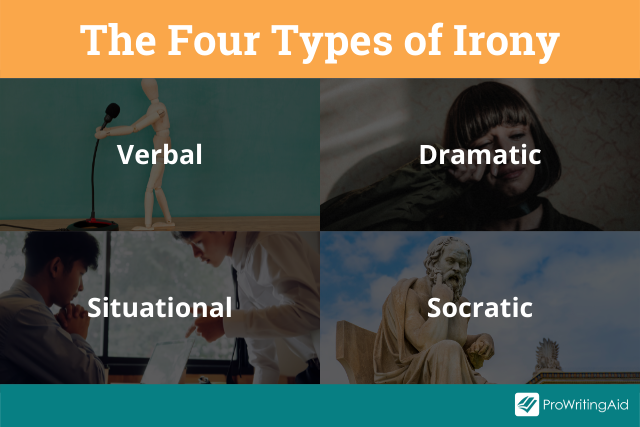

When someone uses irony, it is typically in one of the three ways: verbal, situational, or dramatic.

Verbal Irony

In this form of irony, the speaker says something that differs from—and is usually in opposition with—the real meaning of the word(s) they’ve used. Take, for example, Edgar Allan Poe’s short story “The Cask of Amontillado.” As Montresor encloses Fortunato into the catacombs’ walls, he mocks Fortunato’s plea—”For the love of God, Montresor!”—by replying, “Yes, for the love of God!” Poe uses this to underscore how Montresor’s actions are anything but loving or humane—thus, far from God.

Situational Irony

This occurs when there is a difference between the intention of a specific situation and its result. The result is often unexpected or contrary to a person’s goal. The entire plot of L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz hinges on situational irony. Dorothy and her friends spend the story trying to reach the Wizard so Dorothy can find a way back home, but in the end, the Wizard informs her that she had the power and knowledge to return home all along.

Dramatic Irony

Here, there is a disparity in how a character understands a situation and how the audience understands it. In Henrik Ibsen’s play A Doll’s House , the married Nora excitedly anticipates the day when she’ll be able to repay Krogstad, who illegally lent her money. She imagines a future “free from care,” but the audience understands that, because Nora must continue to lie to her husband about the loan, she will never be free.

Not all irony adheres perfectly to one of these definitions. In some cases, irony is simply irony, where something’s appearance on the surface is substantially different from the truth.

Irony vs. Coincidence

Irony is often confused with coincidence. Though there is some overlap between the two terms, they are not the same thing. Coincidence describes two or more unlikely activities that share unexplainable similarities. It is often confused with situational irony. For example, finding out a friend you made in adulthood went to your high school is a coincidence, not an ironic event. Additionally, coincidence isn’t classifiable by type.

Irony, on the other hand, has a much starker and more substantial disparity between intention and result, with the result often the direct opposite of the intention. For example, the fact that the word lisp is ironic, considering it refers to an inability to properly pronounce s sounds but itself contains an s .

The Functions of Irony

How an author uses irony depends on their intentions and the story or scene’s larger context . In much of literature, irony highlights a larger point the author is making—often a commentary on the inherent difficulties and messiness of human existence.

With verbal irony, a writer can demonstrate a character’s intelligence, wit, or snark—or, as in the case of “ The Cask of Amontillado ,” a character’s unmitigated evil. It is primarily used in dialogue and rarely offers up any insight into the plot or meaning of a story.

With dramatic irony, a writer illustrates that knowledge is always a work in progress. It reiterates that people rarely have all the answers in life and can easily be wrong when they don’t have the right information. By giving readers knowledge the characters do not have, dramatic irony keeps readers engaged in the story; they want to see if and when the characters learn this information.

Finally, situational irony is a statement on how random and unpredictable life can be. It showcases how things can change in the blink of an eye and in bigger ways than one ever anticipated. It also points out how humans are at the mercy of unexplained forces, be they spiritual, rational, or matters of pure chance.

Irony as a Function of Sarcasm and Satire

Satire and sarcasm often utilize irony to amplify the point made by the speaker.

Sarcasm is a rancorous or stinging expression that disparages or taunts its subject. Thus, it usually possesses a certain amount of irony. Because inflection conveys sarcasm more clearly, saying a sarcastic remark out loud helps make the true meaning known. If someone says “Boy, the weather sure is beautiful today” when it is dark and storming, they’re making a sarcastic remark. This statement is also an example of verbal irony because the speaker is saying something in direct opposition to reality. But an expression doesn’t necessarily need to be verbal to communicate its sarcastic nature. If the previous example appeared in a written work, the application of italics would emphasize to the reader that the speaker’s use of the word beautiful is suspect. To further clarify, the remark would closely precede or follow a description of the day’s unappealing weather.

Satire is an entire work that critiques the behavior of specific individuals, institutions, or societies through outsized humor. Satire normally possesses both irony and sarcasm to further underscore the illogicality or ridiculousness of the targeted subject. Satire has a long history in literature and popular culture. The first known satirical work, “The Satire of the Trades,” dates back to the second millennium BCE. It discusses a variety of trades in an exaggerated, negative light, while presenting the trade of writer as one of great honor and nobility. Shakespeare famously satirized the cultural and societal norms of his time in many of his plays. In 21st-century pop culture, The Colbert Report was a political satire show, in which host Stephen Colbert played an over-the-top conservative political commentator. By embodying the characteristics—including vocal qualities—and beliefs of a stereotypical pundit, Colbert skewered political norms through abundant use of verbal irony. This is also an example of situational irony, as the audience knew Colbert, in reality, disagreed with the kind of ideas he was espousing.

Uses of Irony in Popular Culture

Popular culture has countless examples of irony.

One of the most predominant, contemporary references, Alanis Morissette’s hit song “Ironic” generated much controversy and debate around what, exactly, constitutes irony. In the song, Morissette sings about a variety of unfortunate situations, like rainy weather on the day of a wedding, finding a fly floating in a class of wine, and a death row inmate being pardoned minutes after they were killed. Morissette follows these lines with the question, “Isn’t it ironic?” In reality, none of these situations is ironic, at least not according to the traditional meaning of the word. These situations are coincidental, frustrating, or plain bad luck, but they aren’t ironic. The intended meaning of these examples is not disparate from their actual meanings. For instance, another line claims that having “ten thousand spoons when all you need is a knife” is ironic. This would only be ironic, if, say, the person being addressed made knives for a living. Morissette herself has acknowledged the debate and asserted that the song itself is ironic because none of the things she sings about are ironic at all.

Pixar/Disney’s movie Monsters, Inc. is an example of situational irony. In the world of this movie, monsters go into the human realm to scare children and harvest their screams. But, when a little girl enters the monster world, it’s revealed that the monsters are actually terrified of children. There are also moments of dramatic irony. As protagonist Sully and Mike try to hide the girl’s presence, she instigates many mishaps that amuse the audience because they know she’s there but other characters have no idea.

In the iconic television show Breaking Bad , DEA agent Hank Schrader hunts for the elusive drug kingpin known as Heisenberg. But what Hank doesn’t know is that Heisenberg is really Walter White, Hank’s brother-in-law. This is a perfect example of dramatic irony because the viewers are aware of Walter’s secret identity from the moment he adopts it.

Examples of Irony in Literature

1. Jonathan Swift, “A Modest Proposal”

Swift’s 1729 essay is a satire rich in verbal ironies. Under the guise of a serious adviser, Swift suggests a way that poor Irish communities can improve their lot in life: selling their children to rich people. He even goes a step further with his advice:

I have been assured by a very knowing American of my acquaintance in London, that a young healthy child well nursed is at a year old a most delicious, nourishing, and wholesome food, whether stewed, roasted, baked, or boiled; and I make no doubt that it will equally serve in a fricassee or a ragout.

Obviously, Swift does not intend for anyone to sell or eat children. He uses verbal ironies to illuminate class divisions, specifically many Britons’ attitudes toward the Irish and the way the wealthy disregard the needs of the poor.

2. William Shakespeare, Titus Andronicus

This epic Shakespeare tragedy is brutal, bloody, farcical, and dramatically ironic. It concerns the savage revenge exacted by General Titus on those who wronged him. His plans for revenge involve Tamora, Queen of the Goths, who is exacting her own vengeance for the wrongs she feels her sons have suffered. The audience knows from the outset what these characters previously endured and thus understand the true motivations of Titus and Tamora.

In perhaps the most famous scene, and likely one of literature’s most wicked dramatic ironies, Titus slays Tamora’s two cherished sons, grinds them up, and bakes them into a pie. He then serves the pie to Tamora and all the guests attending a feast at his house. After revealing the truth, Titus kills Tamora—then the emperor’s son, Saturninus, kills Titus, then Titus’s son Lucius kills Saturninus and so on.

3. O. Henry, “The Gift of the Magi”

In this short story, a young married couple is strapped for money and tries to come up with acceptable Christmas gifts to exchange. Della, the wife, sells her hair to get the money to buy her husband Jim a watchband. Jim, however, sells his watch to buy Della a set of combs. This is a poignant instance of situational irony, the meaning of which O. Henry accentuates by writing that, although “[e]ach sold the most valuable thing he owned in order to buy a gift for the other,” they were truly “the wise ones.” That final phrase compares the couple to the biblical Magi who brought gifts to baby Jesus, whose birthday anecdotally falls on Christmas Day.

4. Margaret Atwood, The Handmaid’s Tale

Atwood’s dystopian novel takes place in a not-too-distant America. Now known as Gilead, it is an isolated and insular country run by a theocratic government. Since an epidemic left many women infertile, the government enslaves those still able to conceive and assigns them as handmaids to carry children for rich and powerful men. If a handmaid and a Commander conceive, the handmaid must give the child over to the care of the Commander and his wife. Then, the handmaid is reassigned to another “post.”

A primary character in the story is Serena Joy, a Commander’s wife. In one of the book’s many ironic instances, it is revealed that Serena, in her pre-Gilead days, was a fierce advocate for a more conservative society. Though she now has the society she fought for, women—even Commanders’ wives—have few rights. Thus, she ironically suffers from the very reforms she spearheaded.

Further Resources on Irony

The Writer has an article about writing and understanding irony in fiction.

Penlighten ‘s detailed list of irony examples includes works mainly from classic literature.

Publishing Crawl offers five ways to incorporate dramatic irony into your writing .

Harvard Library has an in-depth breakdown of the evolution of irony in postmodern literature .

TV Tropes is a comprehensive resource for irony in everything from literature and anime to television and movies.

Related Terms

Improve your writing in one of the largest and most successful writing groups online

Join our writing group!

What Is Irony? Definition and 5 Different Types of Irony to Engage Readers

by Fija Callaghan

Most of us are familiar with irony in our day to day lives—for instance, if you buy a brand new car only to have it break down on its very first ride (situational irony). Or if someone tells you they love your new dress, when what they actually mean is that it flatters absolutely no one and wasn’t even fashionable in their grandparent’s time (verbal irony).

Ironic understatement and ironic overstatement make their way into our conversations all the time, but how do you take those rascally twists of fate and use them to create a powerful story?

There are countless examples of irony in almost all storytelling, from short stories and novels to stage plays, film, poetry, and even sales marketing. Its distinctive subversion of expectation keeps readers excited and engaged, hanging on to your story until the very last page.

What is irony?

Irony is a literary and rhetorical device in which a reader’s expectation is sharply contrasted against what’s really happening. This might be when someone says the opposite of what they mean, or when a situation concludes the opposite of how one would expect. There are five types of irony: Tragic, Comic, Situational, Verbal, and Socratic.

The word irony comes from the Latin ironia , which means “feigned ignorance.” This can be a contradiction between what someone says and what they mean, between what a character expects and what they go on to experience, or what the reader expects and what actually happens in the plot. In all cases there’s a twist that keeps your story fresh and unpredictable.

By using different kinds of irony—and we’ll look at the five types of irony in literature down below—you can manage the reader’s expectations to create suspense and surprise in your story.

What’s not irony?

The words irony and ironic get thrown around a fair bit, when sometimes what someone’s really referring to is coincidence or plain bad luck. So what constitutes irony? It’s not rain on your wedding day, or or a free ride when you’ve already paid. Irony occurs when an action or event is the opposite of its literal meaning or expected outcome.

For example, if the wedding was between a woman who wrote a book called Why You Don’t Need No Man and a man who held a TEDtalk called “Marriage As the Antithesis of Evolution,” their wedding (rainy or not) would be ironic—because it’s the opposite of what we would expect.

Another perfect example of irony would be if you listened a song called “Ironic,” and discovered it wasn’t about irony after all.

Why does irony matter in writing?

Irony is something we all experience, sometimes without even recognizing it. Using irony as a literary technique in your writing can encourage readers to look at your story in a brand new way, making them question what they thought they knew about the characters, theme, and message that your story is trying to communicate.

Subverting the expectations of both your readers and the characters who populate your story world is one of the best ways to convey a bold new idea.

Aesop used this idea very effectively in his moralistic children’s tales, like “The Tortoise and the Hare.” The two title characters are set up to race each other to the finish line, and it seems inevitable that the hare will beat the tortoise easily. By subverting our expectations, and leading the story to an unexpected outcome, the author encourages the reader to think about what the story means and why it took the turn that it did.

The 5 types of irony

While all irony functions on the basis of undermining expectations, this can be done in different ways. Let’s look at the different types of irony in literature and how you can make them work in your own writing.

1. Tragic irony

Tragic irony is the first of two types of dramatic irony—both types always show the reader more than it shows its characters. In tragic dramatic irony, the author lets the reader in on the downfall waiting for the protagonist before the character knows it themselves.

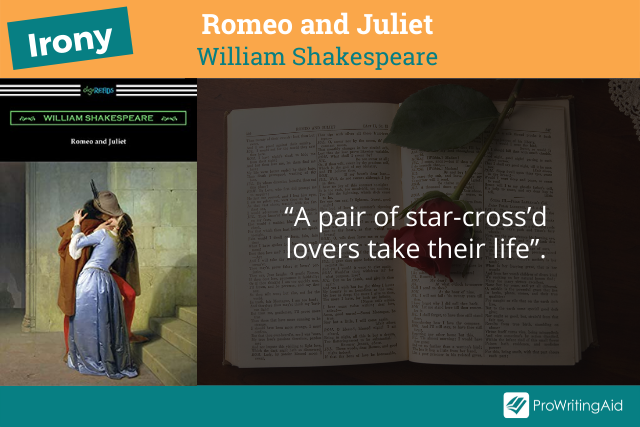

This is a very common and effective literary device in many classic tragedies; Shakespeare was a big fan of using tragic irony in many of his plays. One famous example comes at the end of Romeo and Juliet , when poor Romeo believes that his girlfriend is dead. The audience understands that Juliet, having taken a sleeping potion, is only faking.

Carrying this knowledge with them as they watch the lovers hurtle towards their inevitable, heartbreaking conclusion makes this story even more powerful.

Another example of tragic irony is in the famous fairy tale “Red Riding Hood,” when our red-capped heroine goes to meet her grandmother, oblivious of any danger. The reader knows that the “grandmother” is actually a vicious, hungry wolf waiting to devour the girl, red hood and all. Much like curling up with a classic horror movie, the reader can only watch as the protagonist comes closer and closer to her doom.

This type of irony makes the story powerful, heartbreaking, and deliciously cathartic.

2. Comic irony

Comic irony uses the same structure as dramatic irony, only in this case it’s used to make readers laugh. Just like with tragic irony, this type of irony depends on allowing the reader to know more than the protagonist.

For example, a newly single man might spend hours getting ready for a blind date only to discover that he’s been set up with his former girlfriend. If the reader knows that both parties are unaware of what’s waiting for them, it makes for an even more satisfying conclusion when the two unwitting former lovers finally meet.

TV sitcoms love to use comedic irony. In this medium, the audience will often watch as the show’s characters stumble through the plot making the wrong choices. For example, in the TV series Friends , one pivotal episode shows a main character accepting a sudden marriage proposal from another—even though the audience knows the proposal was made unintentionally.

By letting the audience in on the secret, it gives the show an endearing slapstick quality and makes the viewer feel like they’re a part of the story.

3. Situational irony

Situational irony is when a story shows us the opposite of what we expect. This might be something like an American character ordering “shop local” buttons from a factory in China, or someone loudly championing the ethics of a vegan diet while wearing a leather jacket.

When most people think about ironic situations in real life, they’re probably thinking of situational irony—sometimes called cosmic irony. It’s also one of the building blocks of the twist ending, which we’ll look at in more detail below.

The author O. Henry was a master of using situational irony. In his short story “ The Ransom of Red Chief ,” two desperate men decide to get rich quick by kidnapping a child and holding him for ransom. However, the child in question turns out to be a horrendous burden and, after some negotiating, the men end up paying the parents to take him off their hands. This ironic twist is a complete reversal from the expectation that was set up at the beginning.

When we can look back on situational irony from the past, it’s sometimes called historical irony; we can retrospectively understand that an effort to accomplish one thing actually accomplished its opposite.

4. Verbal irony

Verbal irony is what we recognize most in our lives as sarcasm. It means saying the opposite of your intended meaning or what you intend the reader to understand, usually by either understatement or overstatement. This can be used for both tragic and comic effect.

For example, in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar , Mark Anthony performs a funeral speech honoring the character Brutus. He repeatedly calls him “noble” and “an honorable man,” even though Brutus was actually involved in the death of the man for which the funeral is being held. Mark Anthony’s ironic overstatement makes the audience aware that he actually holds the opposite regard for the villain, though he is sharing his inflammatory opinion in a tactful, politically safe way.

Verbal irony is particularly common in older and historical fiction in which societal constraints limited what people were able to say to each other. For example, a woman might say that it was dangerous for her to walk home all alone in the twilight, when what she really meant is that she was open to having some company.

In Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice , the two younger girls wail that they’ve hurt their ankles, hoping to elicit some sympathy from the strong arms of the men. You can use this kind of rhetorical device to enhance your character development.

5. Socratic irony

Socratic irony is actually a little bit like dramatic irony, except that it happens between two characters rather than between the characters and the reader. This type of irony happens when one character knows something that the other characters don’t.

It’s a manipulative technique that a character uses in order to achieve a goal—to get information, to gain a confession, or to catch someone in a lie. For example, police officers and lawyers will often use this technique to trip someone up: They’ll pretend they don’t know something and ask questions in order to trick someone into saying something they didn’t intend.

Usually Socratic irony is used in a sly and manipulative way, but not always; a teacher might use the Socratic irony technique to make a child realize they know more about a subject than they thought they did, by asking them leading questions or to clarify certain points. Like verbal irony, Socratic irony involves a character saying something they don’t really mean in order to gain something from another character.

Is irony the same as a plot twist?

The “plot twist” is a stylistic way of using situational irony. In the O. Henry example we looked at above, the author sets up a simple expectation at the start of the story: the men will trade in the child for hard cash and walk away happy. Alas, life so rarely goes according to plan. By the time we reach the story’s conclusion, our expectation of the story has been completely twisted around in a fun, satisfying way.

Not all situational irony is a plot twist, though. A plot twist usually comes either at the end or at the midpoint of your story. Situational irony can happen at any time as major plot points, or as small, surprising moments that help us learn something about our characters or the world we live in.

You’ll often see plot twists being compared to dramatic irony, because they have a lot in common. Both rely on hidden information and the gradual unfurling of secrets. The difference is that with a plot twist, the reader is taken by surprise and given the new information right along with the characters. With dramatic irony, the reader is in on the trick and they get to watch the characters being taken off guard.

Both dramatic irony and plot twists can be used quite effectively in writing. It’s up to you as the writer to decide how close you want your readers and your characters to be, and how much you want them to experience together.

How to use irony in your own writing

One of the great advantages of irony is that it forces us to look at things in a new way. This is essential when it comes to communicating theme to your reader.

In literature, theme is the underlying story that’s being told—a true story, a very real message or idea about the world we live in, the way we behave within it, or how we can make it a better place. In order to get that message across to our readers, we need to give them a new way to engage with that story. The innate subversion of expectations in irony is a wonderful way to do this.

For example, the classic fairy tale “Beauty and the Beast” uses irony very effectively to communicate its theme: don’t judge a person by their appearance.

Based on our preconceptions of this classic type of fairy tale, we would go in expecting the handsome young soldier to be the hero and the beastly monster to be the adversary. We might also expect the beautiful girl to be helpless and weak-spirited, waiting for her father to come in and save her. In this story, however, it’s the girl who saves her foolish father, the handsome soldier who shows himself to be the true monster, and the beast who becomes a hero to fight for those he cares about.

Not only do these subversions make for a powerful and engaging story, they do something very important for our readers: they make them ask themselves why they had these preconceptions in the first place. Why do we expect the handsome soldier to be noble and kind? Why do we expect the worst from the man with the beastly face before even giving him the chance to speak?

It’s these honest, sometimes uncomfortable questions, more than anything else, that make the theme real for your reader.

When looking for ways to weave theme throughout your story, consider what preconceived ideas your reader might be coming into the story with that might stand in the way of what you’re trying to say. Then see if you can find ways to make those ideas stand on their head. This will make the theme of your story more convincing, resonant, and powerful.

The one mistake to never make when using irony in your story

I’m going to tell you one of life’s great truths, which might be a bit difficult for some people to wrap their heads around. Embrace it, and you’ll leave your readers feeling a lot happier and more satisfied at the end of your story. Here it is:

You don’t need to be the smartest person in the room.

Have you ever been faced with a plot twist in a story and thought, “but that doesn’t make any sense”? Or realized that a surprising new piece of information rendered the events of the plot , or the effective slow build of characterization, absolutely meaningless?

These moments happen because the author became so enamored with the idea of pulling a fast one on the reader, revealing their cleverly assembled sleight-of-hand with the flourish of a theater curtain, that they forget the most important thing: the story .

When using irony in your work, the biggest mistake you can make is to look at it like a shiny, isolated hat trick. Nothing in your story is isolated; every moment fits together as a thread in a cohesive tapestry.

Remember that even if an ironic turn is unexpected, it needs to make sense within the world of your story. This means within the time and place you’ve created—for instance, you wouldn’t create an ironic twist in a medieval fantasy by suddenly having a character whip out a cellphone—but also within the world of your characters.

For example, if it turns out your frail damsel in distress is actually a powerful sorceress intent on destroying the hero, that’s not something you can just drop into your story unannounced like a grenade (no matter how tempting it might be). You need to begin laying down story seeds for that moment right from the beginning. You want your reader to be able to go back and say “ ohhh , I see what they did there. It all makes sense now.”

Irony—in particular the “twist ending”—can be fun, surprising, and unexpected, but it also needs to be a natural progression of the world you’ve created.

Irony is a literary device that reveals new dimension

To understand irony, we need to understand expectation in our audience or readers. When you’re able to manipulate these expectations, you engage your audience in surprising ways and maybe even teach them something new.

Get feedback on your writing today!

Scribophile is a community of hundreds of thousands of writers from all over the world. Meet beta readers, get feedback on your writing, and become a better writer!

Join now for free

Related articles

What is an Oxymoron? Easy Definition, With Examples from Literature

What is Shadow Writing? Complete Guide Plus 35+ Prompts

Literary Devices List: 33 Main Literary Devices with Examples

Active vs. Passive Voice: What’s the Difference?

What is a Paradox? Definition, Types, and Examples

What Is Personification? Definition and Examples from Literature

What is irony? Well, it’s like rain on your wedding day. It’s a free ride, when you’ve already paid. ’90s radio is helpful here.

Okay; but what is irony? It can often be easier to point to specific ironies than to find a definition of irony itself that hits home.

Irony definition: contradiction of our perceived reality.

At root, irony involves contradiction of our perceived reality. This powerful literary device is often misunderstood or misused, but when wielded correctly, it can reveal deeper truths by highlighting the many strange contradictions and juxtapositions woven through life.

This article examines the different types of irony in literature, including dramatic irony, situational irony, verbal irony, and others. Along the way, we look at different irony examples in literature, and end on tips for using this device in your own writing.

But first, let’s further clarify what this tricky writing technique means. What is irony in literature?

Irony Definition: Contents

Irony Definition: What is Irony in Literature?

Irony vs. sarcasm, irony vs. satire, different types of irony in literature, dramatic irony definition, situational irony definition, verbal irony definition, irony in poetry, types of irony in literature: venn diagram, other types of irony in literature, using irony in your own writing.

Irony occurs when a moment of dialogue or plot contradicts what the audience expects from a character or story. In other words, irony in literature happens when the opposite of what you’d expect actually occurs.

Irony definition: a moment in which the opposite of what’s expected actually occurs; a contrast between “what seems to be” and “what is.”

To put it another way: irony is a contrast between “what seems to be” and “what is.”

For example, let’s say you’re having an awful day. You got stuck in traffic, your head hurt, it was storming all afternoon, the deli messed up your lunch order, and your son’s school called to say he got in a fight. Finally, you get home and check your email, and see a message from the dream job you just interviewed for. You’re expecting the worst, because it’s been such a crappy day, and—you got the job.

As a literary technique, this device primarily accomplishes two goals. First, it allows you to juxtapose contradictory ideas in your writing. By diverging from what the reader or character expects, an ironic plot or dialogue exchange allows opposing ideas to sit side-by-side, creating a fertile space for interpretation and creative inquiry.

Second, irony in literature emulates real life. We’ve all had days like the one described above, where everything seems awful and suddenly the best news reaches us (or vice versa). The real world follows no logical trajectory, and we find ourselves surrounded by competing ideas and realities. Irony makes talking about these contradictions possible.

Because both irony and sarcasm come across as wry statements about certain situations, people often confuse the two terms. However, sarcasm has a much narrower use.

Sarcasm only occurs in dialogue: you can speak something with sarcasm, but an event cannot be sarcastic. Additionally, sarcasm is usually intended to be mean or point at the folly of a certain person. By speaking wryly or ironically about another person’s faults, an individual’s use of sarcasm will often be insulting or derogatory, even if both parties understand that the sarcasm is simple banter. (Sarcasm comes from the Greek for “cutting flesh.”)

For example, let’s say someone you know just came to a very obvious or delayed realization. You might say to them “nice thinking, Einstein,” obviously implying that their intelligence is on the other side of the bell curve.

So, the difference between irony vs. sarcasm is that sarcasm is a verbal insult that points towards someone’s flaws ironically, whereas irony encompasses contradictory ideas, statements, and events. As such, sarcasm is sometimes a form of irony, but only partially falls under a much broader umbrella.

Satire is another term that’s often confused with irony and sarcasm. Satire, like sarcasm, is a form of expression; but, satire is also a literary genre with its own complex history.

Satire is the art of mocking human follies. Often, satire has the goal of critiquing or correcting those follies. A good piece of satire will hold a mirror up against the reader, against politicians, or against society at large. By recognizing, perhaps, our own logical fallacies or erroneous ways of living, satire hopes to help people live more honest, moral lives (as defined by the satirist).

Irony is certainly an element of good satire. We all act in contradictory or hypocritical ways. Irony in satire helps the satirist illuminate those contradictions. But, the two are fundamentally different: irony notices contradictions, whereas satire wields this and other devices to mock human follies.

Learn more about satire (and how to write it!) here:

Satire Definition: How to Write Satire

There are, primarily, three different types of irony in literature: dramatic, situational, and verbal irony. Each form has its own usage in literature, and there are also many sub-types of irony that fall under each of these categories.

For now, let’s define each type and look at specific irony examples in literature.

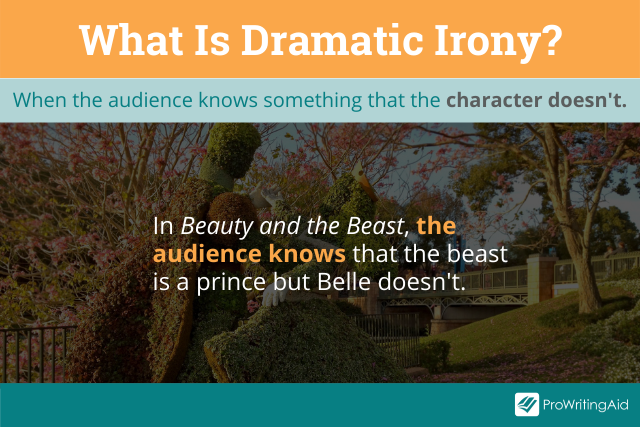

Dramatic irony occurs when the audience knows something that the story’s characters do not. As such, fictional characters make erroneous decisions and face certain avoidable consequences. If only they had known what the audience knows!

Dramatic irony definition: when the audience knows something that the story’s characters do not, resulting in poor decision making or ironic consequences.

You will most likely find dramatic irony examples in plays, screenplays, and other forms of theater. Shakespeare employs this device often, as do playwrights like Henrik Ibsen, Tennessee Williams, and the filmmaker Alfred Hitchcock. Nonetheless, fiction writers also employ dramatic irony, particularly when the story involves multiple narrative points of view .

Dramatic Irony Examples in Literature

Shakespeare was truly a master of dramatic irony, as he employed the device to entertain, captivate, and frustrate his audience.

In Romeo & Juliet , Juliet is apparently dead, having taken a strong sleeping potion, and is laid in the Capulet crypt. The message was supposed to be conveyed to Romeo that, upon her waking, the two would run off together. But, this message never arrives, so when Romeo hears of Juliet’s death and goes to her tomb to mourn, he kills himself with poison. The audience knows that Juliet is just asleep, making Romeo’s death a particularly tragic example of dramatic irony.

A Series of Unfortunate Events by Lemony Snicket is also laden with dramatic irony examples. In The Reptile Room , the narrator addresses this directly:

Of course, this is a series written towards children, so the direct translation of what dramatic irony means might seem a bit juvenile for adult fiction writers. Nonetheless, this excerpt defines the precise feeling that dramatic irony can bestow upon the reader, illustrating it through the contrast of Uncle Monty’s dialogue against the impending doom the Baudelaires face.

(Note: this is not an example of verbal irony, because Uncle Monty’s dialogue is not intentionally contradicting what he means. More on this later in the article.)

Also known as irony of fate, of events, or of circumstance, situational irony describes plot events with unexpected or contradictory outcomes.

Situational irony definition: plot events with unexpected or contradictory outcomes.

Let’s say, for example, your local fire department burns down. Or the new moisturizer you bought actually wrinkles your skin. Or, heaven forbid, you finish working on your manuscript, click “save” for the final time, and your laptop completely shuts down. All of these possibilities point towards the unpredictability of the future—as do the below situational irony examples in literature.

Situational Irony Examples in Literature

Situational irony happens when a certain event or reaction is expected, and an entirely contradictory one occurs.

For example, in the story “ The Gift of the Magi ” by O. Henry, two young lovers have no money to spare, but are trying to find each other the perfect Christmas gift. The girl, Della, has beautiful hair, which she cuts and sells to buy Jim a fob chain for his watch. Jim, in turn, sells his watch to buy Della some combs for her hair. As a result, each lover’s gift turns out to be useless, since each has sold their most prized possession to show their love to each other.

The narrator summarizes this beautiful moment of situational irony thus:

Of course, ironic situations occur all the time in real life, so there are many situational irony examples in nonfiction. This excerpt comes from the essay “ My Mother’s Eyes ” by Henriette Lazaridis:

Certainly, the speaker would not expect to see herself resembled in her mother’s gaunt, dying face, but that’s exactly what happens. This moment of situational irony encourages the reader to examine the relationship between death, family, and heritage.

Verbal irony refers to the use of dialogue where one thing is spoken, but a contrasting meaning is intended. The key word here is intentional: verbal irony is not merely lying or speaking a faux pas, it’s an intentional use of contrasting language to describe something in particular.

Verbal irony definition: An instance of dialogue where one thing is spoken, but a contrasting meaning is intended.

We do this all the time in conversational English. For example, you might walk into a storm and say “wonderful weather we’re having!” Or, if someone is wearing a jacket you love, you might say “that’s hideous!”

We’ve already contrasted irony vs. sarcasm, so as you may have inferred, verbal irony can sometimes be a form of sarcasm. (For example, telling someone with an ugly shirt “nice shirt!”) That said, verbal irony is not always sarcasm, so remember that sarcasm is intentionally used to insult someone’s folly.

Verbal Irony Examples in Literature

Because verbal irony is always spoken, you will almost always see this device utilized in dialogue. (The only time it isn’t used in dialogue is when a narrator, usually first person, speaks to the audience ironically.)

In George Bernard Shaws’ Pygmalian , Professor Higgins’ housekeeper has just told the professor not to swear. To this he replies:

You and I might not think “what the devil” counts as swearing, but it’s certainly ironic for Professor Higgins to invoke the devil after claiming he never swears.

Many more verbal irony examples come to us, again, from Shakespeare. In Othello , the character Iago—a complex antagonist who feigns loyalty to Othello but seeks his demise—proclaims “My lord, you know I love you.” The audience knows that Iago hates Othello, but Othello himself does not know this, making this bit of dialogue particularly ironic.

In a different Shakespeare play, Julius Caesar , Caesar describes Brutus (his later-betrayer) as an “honorable man.” At this point, the audience knows that Brutus plans to join the conspiracy to kill Caesar.

With verbal irony, sometimes the dialogue is understood as ironic by the other characters, and sometimes only by the audience. Either way, an attentive reader will recognize when a character means the opposite of what they say, or when their intentions simply do not align with their speech.

Most of the irony examples in this article have come from fiction. But, poets certainly make use of this literary device as well, though often much more subtly.

Irony occurs in poetry when the poet wants to illuminate contradictions or awkward juxtapositions. T. S. Eliot gives us a great example in “ The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock .” The speaker describes a beautiful evening as “a patient etherized on a table.” It’s a rather dramatic metaphor , incongruous with the beauty of the evening itself. Eliot’s poem is, among other things, a lament of modernity, which he believes is corrupting all the beauty in the world. By using a modern medical procedure to describe the natural world, Eliot’s hyperbolic metaphor imparts a subtle, yet vicious, irony about the modern day.

Of course, irony can operate in poetry in much more obvious ways. Here’s an example from Louise Glück, “ Telemachus’ Detachment “:

When I was a child looking at my parents’ lives, you know what I thought? I thought heartbreaking. Now I think heartbreaking, but also insane. Also very funny.

Telemachus is, in Greek mythology, the son of Odysseus and Penelope. This short poem is a commentary on that wild myth (The Odyssey). It is also deeply relatable to any child wondering at their parents’ insane ways of living. It is a poem whose central device is irony, and it uses this device to draw a connection between myth and reality, which are much more similar to one another than they seem.

You may have heard of some other types of irony, such as socratic, historical, or cosmic irony. These forms are technically subcategories of the above 3, but it is useful to make these distinctions, especially as they relate to particular genres of literature.

Cosmic irony in literature: an instance where a character’s outcome in the story is outside of their control. For example, in Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles , the titular Tess is a mostly-innocent protagonist to whom one thing after another goes wrong. Despite her innocence, a malevolent series of misfortunes forces her to murder someone, resulting in her imprisonment and execution. The narrator then writes that “Justice was done, and the President of the Immortals, in Aeschylean phrase, had ended his sport with Tess.” In other words, Tess is the plaything of fate, and the justice bestowed upon her is extremely ironic, given she is the victim of poor circumstance. This is a subcategory of situational irony (although the narrator’s use of the word Justice is, indeed, verbal irony).

Historical irony in literature: a situation that, in hindsight, was deeply ironic. There are countless examples of this in the real world. For example, gunpowder was invented by Chinese alchemists searching for the elixir of life—if anything, they created an elixir of death. Or, the introduction of the Kudzu vine in the United States was intended to prevent soil erosion, particularly after the dust bowl in the 1930s. Kudzu became an invasive species, choking plants of resources instead of preserving the ecosystem. This form of situational irony occurs countless times in history, showing up whenever a person’s or government’s decision backfires tremendously.

Socratic irony in literature: the use of verbal irony as part of the Socratic method. The teacher will either pretend to be dumb, or pretend that the student is wise, to draw out the flaws in a student’s argument. While you don’t see this often in literature, it’s a possible rhetorical strategy for teachers, lawyers, and even comedians.

The discrepancy between “what seems to be” and “what is” can prove particularly useful for writers. Irony helps writers delay the reveal of crucial information, challenge the reader’s worldview, and juxtapose contradictory ideas and themes. As such, this literary device can pull together your stories and plays, so long as you wield it effectively and with discretion.

Here are some possibilities for your writing:

Building tension

When the audience knows something that the characters don’t, we can only watch in horror as those characters make ill-informed decisions.

Playing with fate

Why do bad things happen to good people? A commentary on fate—or, at the very least, the seeming randomness of the universe—often goes hand-in-hand with this literary device.

Stringing the plot forward

If every character made perfect decisions, there would be no plot. Irony helps throw characters into challenging, even preventable situations, forcing the story to reckon with that character’s imperfections.

Generating conflict

For many stories, conflict is the engine that drives the plot forward. When a character’s actions and words don’t match, or when the world’s treatment of a character is opposite that character’s moral purity, a good story ensues.

Challenging the reader

What does it mean for society when a fire department burns down, a lung doctor smokes cigarettes, or a government causes chaos by trying to instill democracy? These themes are aided and expounded by the use of irony in literature.

Entertaining exchanges

Whether the narrator speaks wryly to the audience, or two characters have witty banter, verbal irony certainly makes a text more entertaining.

Juxtaposition

What does it mean to love the person you hate? Can justice be served to the most unjust of human beings? The juxtaposition of contradictory themes allows us to examine the world with nuance, discretion, and creativity.

Making fiction true-to-life

We all find ourselves from time to time in the midst of ironic situations. Including irony in your stories isn’t just a clever literary device, it’s an attempt at making your stories as believable as possible.

Master the Different Types of Irony at Writers.com

Does the irony work in your writing? How can you tell? Getting the feedback you need from experienced writers is essential to polishing your craft. Take a look at the upcoming writing courses at Writers.com, where you’ll find the expertise and creativity that takes your writing to the next level.

Sean Glatch

Excellent explanation of terms that are easy to confuse

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

School of Writing, Literature, and Film

- BA in English

- BA in Creative Writing

- About Film Studies

- Film Faculty

- Minor in Film Studies

- Film Studies at Work

- Minor in English

- Minor in Writing

- Minor in Applied Journalism

- Scientific, Technical, and Professional Communication Certificate

- Academic Advising

- Student Resources

- Scholarships

- MA in English

- MFA in Creative Writing

- Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies (MAIS)

- Low Residency MFA in Creative Writing

- Undergraduate Course Descriptions

- Graduate Course Descriptions

- Faculty & Staff Directory

- Faculty by Fields of Focus

- Promoting Your Research

- 2024 Spring Newsletter

- Commitment to DEI

- Twitter News Feed

- 2022 Spring Newsletter

- OSU - University of Warsaw Faculty Exchange Program

- SWLF Media Channel

- Student Work

- View All Events

- The Stone Award

- Conference for Antiracist Teaching, Language and Assessment

- Continuing Education

- Alumni Notes

- Featured Alumni

- Donor Information

- Support SWLF

What is Irony? | Definition & Examples

"what is irony": a guide for english students and teachers.

View the Full Series: The Oregon State Guide to Literary Terms

- Guide to Literary Terms

- BA in English Degree

- BA in Creative Writing Degree

- OSU Admissions Info

What is Irony? - Transcription (English and Spanish Subtitles Available in the Video. Click HERE for the Spanish transcript)

By Raymond Malewitz , Oregon State University Associate Professor of American Literature

5 November 2019

As we transition from childhood into adulthood, we begin to realize that things, people, and events are often not what they appear to be. At times, this realization can be funny, but it can also be disturbing or confusing. Children often recoil at this murky confusion, preferring a simple world in which what you see is what you get. Adults, on the other hand, often LOVE this confusion-- so much so that we often tell ourselves stories just to conjure up this state. Whether we run from it or savor it, make no mistake: “irony” is a dominant feature of our lives.

In simplest terms, irony occurs in literature AND in life whenever a person says something or does something that departs from what they (or we) expect them to say or do. Just as there are countless ways of misunderstanding the world [sorry kids], there are many different kinds of irony. The three most common kinds you’ll find in literature classrooms are verbal irony, dramatic irony, and situational irony .

Verbal irony occurs whenever a speaker or narrator tells us something that differs from what they mean, what they intend, or what the situation requires. Many popular internet memes capitalize upon this difference, as in this example.

maxresdefault.jpg

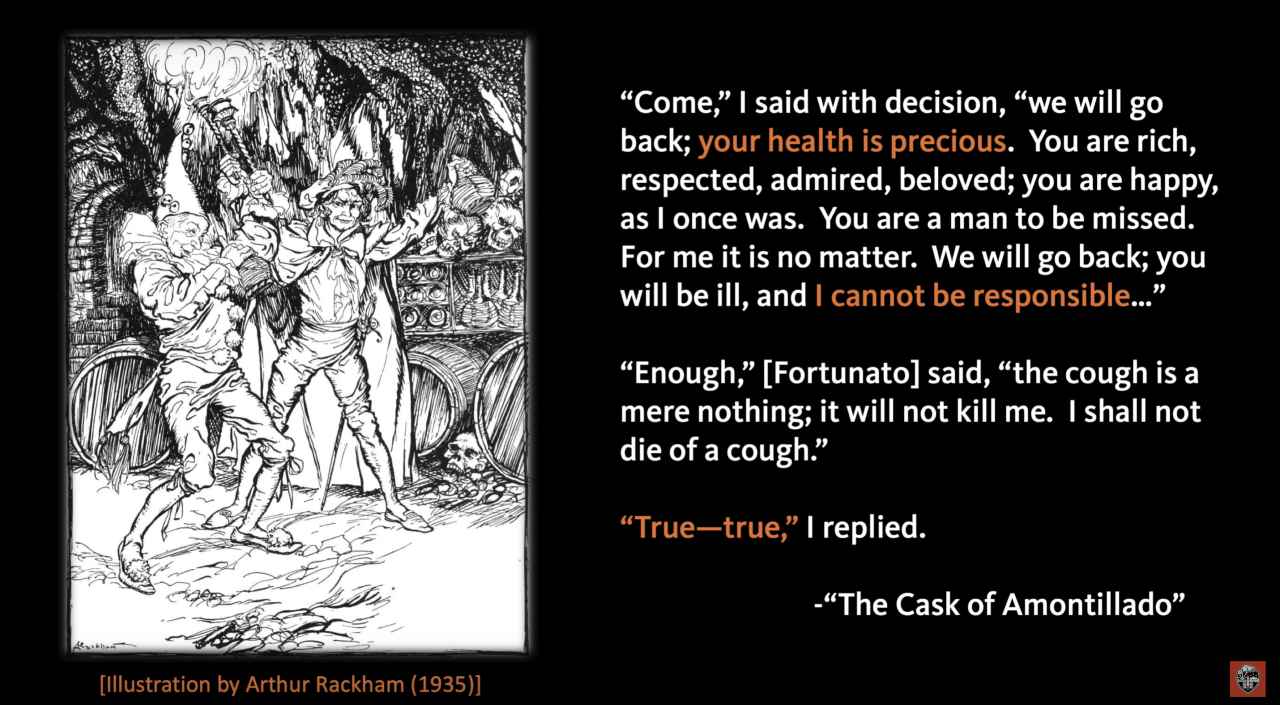

Edgar Allan Poe’s short story “The Cask of Amontillado” offers a more complex example of verbal irony. In the story, a man named Montresor lures another man named Fortunato into the catacombs beneath his house by appearing to ask him for advice on a recent wine purchase. In reality, he means to murder him. Brutally. By walling him up in those catacombs [spoiler alert]!

As the two men travel deeper underground, Fortunato has a coughing fit. Montresor appears to comfort him in the following richly ironic exchange:

“Come,” I said with decision, “we will go back; your health is precious. You are rich, respected, admired, beloved; you are happy, as I once was. You are a man to be missed. For me it is no matter. We will go back; you will be ill, and I cannot be responsible…”

“Enough,” [Fortunato] said, “the cough is a mere nothing; it will not kill me. I shall not die of a cough.”

“True—true,” I replied.”

from_poes_cask_of_amontillado.jpg

If we only paid attention to the appearance of Montresor’s words, we would think he was genuinely concerned with poor Fortunato’s health as he hacks up a lung. We would also think that Montresor was trying to be nice to Fortunato by agreeing with him that he won’t die of a cough. But knowing Montresor’s true intentions, which he reveals at the start of the story, we are able to understand the verbal irony that colors these assurances. Fortunato won’t die of a cough, Montresor knows, but he will definitely die.

This scene is also a great example of dramatic irony . Dramatic irony occurs whenever a character in a story is deprived of an important piece of information that governs the plot that surrounds them. Fortunato, in this case, believes that Montresor is a friendly schlub with a terrible wine palette and a curious habit of storing his wine near the dead bodies of his ancestors. The pleasure of reading the story stems in part from knowing what he doesn’t—that he’s walking into Montresor’s trap. We delight, in other words, in the ironic difference between our complex way of understanding of the world and Fortunato’s simple worldview.

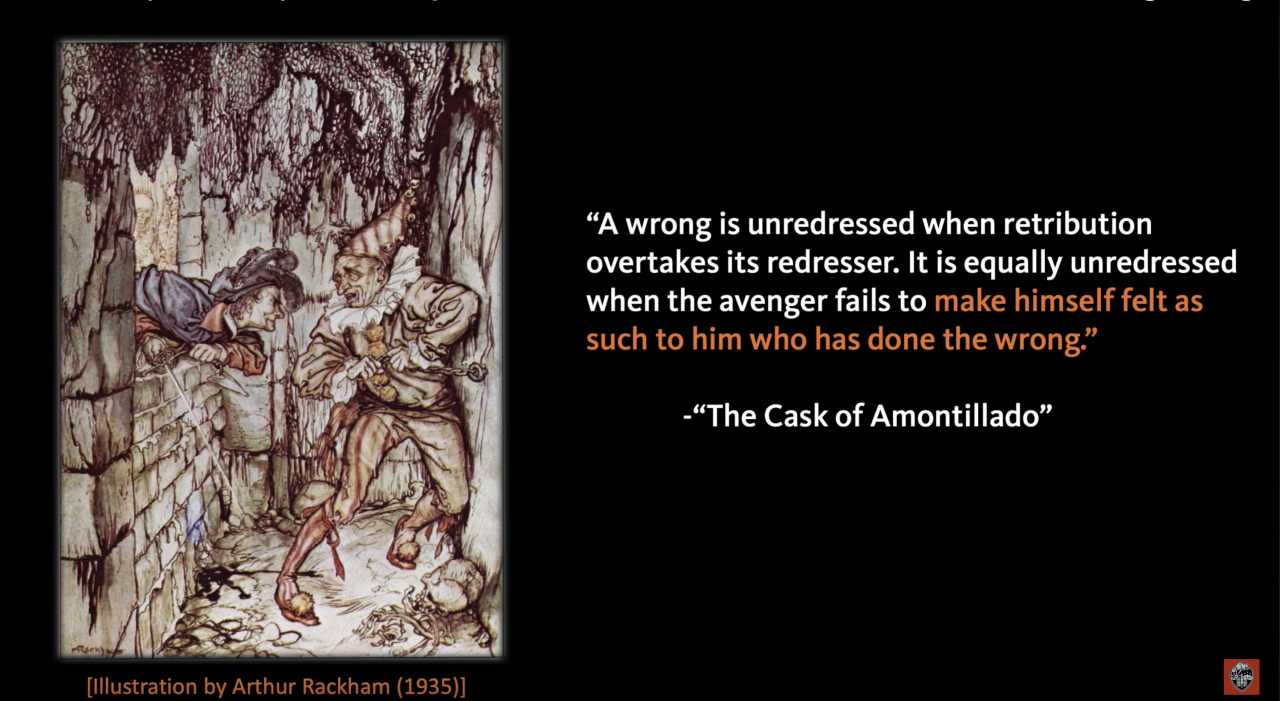

Finally, the story also includes, arguably, a great example of situational irony . As its name suggests, situational irony occurs when characters’ intentions are foiled, when people do certain things to bring about an intended result, but in fact produce the opposite result. At the start of the story, Montresor tells his readers that his project will succeed only if he “makes himself felt as such to him who has done the wrong.”

from_poes_cask_of_amontillado_ii.jpg

In other words, Fortunato must not only know that he has been tricked but also why he was tricked and why he must die. If this is Montresor’s intention, however, he goes about it in a rather strange way, offering Fortunato countless sips of wine on their trip into the catacombs that gets his antagonist pretty drunk. By the end of the story, Montresor has certainly got away with the crime, but it’s far from certain that Fortunato (or even Montresor) knows why he is given such a terrible death.

So why does Montresor insist on telling us that his story is a success? One reason might be that he is anxious about the situational irony that envelopes his story and wants to cover the reality of that irony with a simple appearance of triumph. He’s gotten away with it, and Fortunato knows why he must die. If readers push back against this desired outcome, testing it against Fortunato’s confusion at being chained to a wall and bricked into place, they travel further than even Montresor is willing to go into the murky catacombs of irony.

Want to cite this?

MLA Citation: Malewitz, Raymond. "What is Irony?" Oregon State Guide to English Literary Terms, 5 Nov. 2019, Oregon State University, https://liberalarts.oregonstate.edu/wlf/what-irony. Accessed [insert date].

Further Resources for Teachers:

Check out the following "What is Irony?" lesson, which models three kinds of irony using Bill Watterson's Calvin and Hobbes comic strip. We've also included a quiz beneath it.

irony_exercise_with_calvin_and_hobbes.pptx

irony_quiz.docx

Kate Chopin's story "The Story of an Hour" offers students many opportunities to discuss different kinds of irony. These ideas are indirectly discussed in our "What is Imagery?" video. Many other literary terms can be used for ironic effect, including Understatement , Free Indirect Discourse , Dramatic Monologue , and Unreliable Narrator . Yiyun Li's short story "A Thousand Years of Good Prayers" is another story suitable for this kind of analysis.

Writing Prompt: Identify examples of verbal irony, dramatic irony, and situational irony in Chopin's or Li's story. When you have made these determinations, explain how they operate together to convey meaning.

Writing Prompt #2: See the prompt in our " What is a Sonnet? " video.

Interested in more video lessons? View the full series:

The oregon state guide to english literary terms, contact info.

Email: [email protected]

College of Liberal Arts Student Services 214 Bexell Hall 541-737-0561

Deans Office 200 Bexell Hall 541-737-4582

Corvallis, OR 97331-8600

liberalartsosu liberalartsosu liberalartsosu liberalartsosu CLA LinkedIn

- Dean's Office

- Faculty & Staff Resources

- Research Support

- Featured Stories

- Undergraduate Students

- Transfer Students

- Graduate Students

- Career Services

- Internships

- Financial Aid

- Honors Student Profiles

- Degrees and Programs

- Centers and Initiatives

- School of Communication

- School of History, Philosophy and Religion

- School of Language, Culture and Society

- School of Psychological Science

- School of Public Policy

- School of Visual, Performing and Design Arts

- School of Writing, Literature and Film

- Give to CLA

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

20 Irony Examples: In Literature and Real Life

Millie Dinsdale

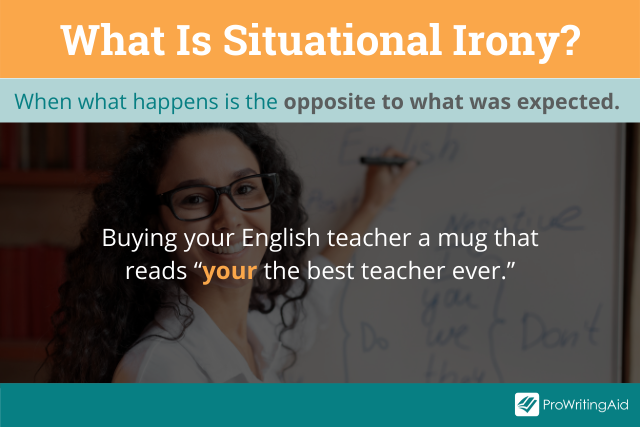

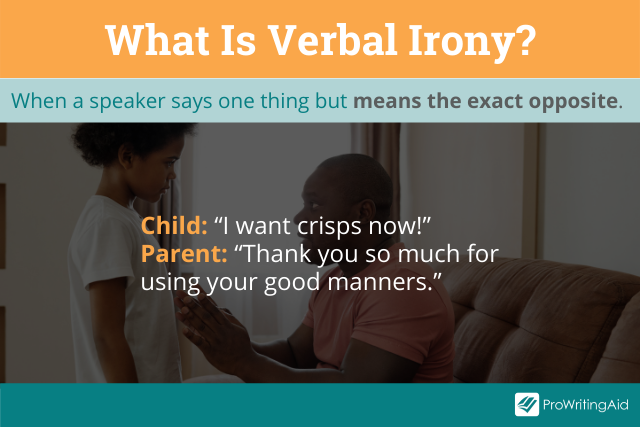

Irony occurs when what happens is the opposite from what is expected.

Writers use irony as a literary technique to add humor, create tension, include uncertainty, or form the central plot of a story.

We will be looking at the four types of irony (three common and one uncommon) and providing examples and tips to help you identify and use them in your work.

Quick Reminder of What Irony Is

Irony examples in literature, irony examples in real life, which scenario is an example of irony.

Irony is a rhetorical device in which the appearance of something is opposite to its reality .

There are four main types of irony: verbal irony, dramatic irony, situational irony, and Socratic irony . Socratic irony is not a literary device, and therefore we will not be looking at examples, but it is worth being aware of.

- Verbal Irony is when a speaker says one thing but means something entirely different. The literal meaning is at odds with the intended meaning.

- Dramatic Irony is when the audience knows something that the characters don’t.

- Situational Irony is when what happens is the opposite of what you expect.

- Socratic Irony is when a person feigns ignorance in order to get another to admit to knowing or doing something. It is named after Socrates, the Greek philosopher, who used this technique to tease information out of his students.

Why is irony important to understand? Along with being a key rhetorical device, irony can also be very effective when used correctly in writing.

To demonstrate this fact we have selected ten examples of irony usage from popular literature. Warning: this list includes a few spoilers.

1) The main characters’ wishes in L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz are a perfect example of situational irony .

The characters go on a quest to fulfill their hearts’ desires and instead of doing so they realize that they already had what they wanted all along. It is unexpected because the reader might assume that all of their desires will be gifted to the four main characters but, in the end, it’s unnecessary.

2) The conclusion between the two primary opponents in The Night Circus contains a large amount of situational irony .

The reader is led to expect that either Marco or Celia will win but, in the end, they both end up working together to keep their creation alive. The competition is not as black and white (pardon the pun) as it initially seems.

3) The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde is full of verbal irony . A great example of this is when Dr Jekyll says “I am quite sure of him,” when referring to Mr Hyde.

This is verbal irony because the reader finds out that Hyde is actually Jekyll’s alter ego, so it would be expected that he knows himself well.

4) Shakespeare creates dramatic irony in the prologue of Romeo and Juliet through the line: “A pair of star-cross’d lovers take their life.”

This well-known example is ironic because the reader knows from the very beginning that their romance will end in death, but they don’t yet know how.

5) Alice’s changing relationship with the Bandersnatch in Alice in Wonderland is situationally ironic .

When we first meet the Bandersnatch, he is ferocious and attempts to harm Alice. When Alice returns his eye, they become friends and the two work together to defeat the Jabberwocky. The audience expects to see an enemy but are instead presented with an ally.

6) George Orwell masters situational irony in Animal Farm through the animals’ endless and fruitless battle to obtain freedom.

All of the animals work together to escape the tyranny of the humans who own them. In doing so they end up under the even stricter rule of the pigs.

7) Roald Dahl’s short story A Lamb to a Slaughter is full of dramatic irony .

A housewife kills her husband with a frozen leg of lamb when he asks for a divorce. The police come looking for evidence and unknowingly dispose of it when they are fed the murder weapon for dinner.

8) The repeated line “May the odds be ever in your favor” in Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games is verbally ironic .

Everyone from district 1 through 12 can be offered as a child sacrifice and has a 1/24 chance of surviving. Even if they do survive they are then delivered back under the control of the Capitol, so the odds are in nobody’s favor.

9) The disparity between children and adults in Roald Dahl’s Matilda is situationally ironic .

Most of the adults in Matilda’s life are hot-headed, uneducated, and unreasonable, while she as a six-year old is more mature than most of them. The traditional roles of child and adult are unexpectedly flipped on their heads.

10) The hit-and-run in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby is situationally ironic .

Daisy Buchanan kills Myrtle when Myrtle runs in front of Gatsby’s car. It is ironic because Myrtle is Tom Buchanan’s mistress but Daisy does not know this. She unintentionally killed her husband's mistress.

Irony works so well in literature because it is so common in real life. Have you ever found yourself saying “well that’s ironic” to a situation in your life?

You could be talking about verbal, situational, or dramatic irony. Let’s take a look at a few everyday examples of each type.

11) When you find out that your pulmonologist (lung doctor) smokes.

This is situationally ironic because you’d expect this doctor of all people to avoid smoking because they understand all of the risks.

12) When someone falls over for the tenth time while ice-skating and says “I meant to do that.”

This person cannot be intending to fall over all the time but they are using verbal irony to make light of a possibly painful situation.

13) Your dog eats his certificate of dog-training obedience.

You would expect that in the process of having obtained an obedience certificate, the dog would also have learnt not to eat random objects. This is an example of situational irony .

14) The fire hydrant is on fire.

This is situationally ironic because the last thing that you would expect to be on fire is the object that is designed to fight fires. A similar example to this would be if a fire station were on fire.

15) A girl is teasing her friend for having mud on his face but she doesn’t know that she also has mud on her face.

From the point of view of the friend, this is an example of dramatic irony because he knows something that she does not.

16) Your mom buys a non-stick pan but has to throw it away because the label is so sticky she cannot get it off.

You would predict that the pan was completely non-stick but are proven wrong at the first hurdle, which is situationally ironic .

17) When someone crashes into a “thank you for driving carefully'' sign.

The vision of a car crashed into the sign makes it clear that they did not drive carefully at all, which is situationally ironic .

18) Buying your English teacher a mug that reads “your the best teacher ever.”

The poor English teacher may feel like they have failed in their job in this situationally ironic situation where their student has bought them a mug with a grammar mistake.

19) When a child says “I want crisps now!” and the parent says: “Thank you so much for using your good manners.”

The child is being impolite and the parent is not actually congratulating the child on their manners in this example of verbal irony . They mean the exact opposite.

20) You can’t open your new scissors because you don’t have any scissors to cut through the plastic.

This example of situational irony is far too common. In buying scissors, it can be expected that you do not have any, so it is ironic that the packaging is designed for someone who already has a pair.

Are you ready for a quick quiz to test your knowledge of irony? The test is split into the three types of irony.

Which of These Are Examples of Situational Irony?

1) A police station is robbed.

2) A child loses his rucksack after being told to take care not to lose it.

3) A person eats sweets while preaching about healthy eating

Only 1) and 3) are examples of situational irony. Sentence 2) is not a situational irony example because it could be expected that the child might lose the rucksack and that is why they were told to take care.

It would, however, be ironic if he subsequently lost his “Most Organized in 2nd Grade” certificate five minutes after being awarded it.

Which of These Are Examples of Verbal Irony?

1) Saying “The weather is lovely today” while it is hailing.

2) “Wow that perfume is so lovely, did you bathe in it?”

3) Saying “Thank you so much for your help” after someone has crushed your new glasses while helping to look for them.

Only example 1) is verbally ironic, the other two are sarcastic comments.

Verbal irony and sarcasm are often confused but there is one big difference between them: verbal irony is when what you say is the opposite of what you mean while sarcasm is specifically meant to embarrass or insult someone.

Which of These Are Examples of Dramatic Irony?

1) A small ship without life boats is stuck in a monumental storm in the middle of the Atlantic.

2) Three characters are killed and a fourth seems to be going the same way.

3) A girl walks down the same alley we have just seen a known murderer walk down.

Only option 3) is an example of dramatic irony because the audience knows that the murderer is down the alley but the girl does not.

Although the other two examples are undeniably dramatic, there is no inherent irony because the audience has no more knowledge about what will happen than those involved.

Why Should You Use Irony in Your Writing?

Irony can be an effective tool to make a reader stop and think about what has just happened.

It can also emphasize a central theme or idea by adding an unexpected twist to the events of the story.

What brilliant examples of irony in literature have we missed? Share your favorites in the comments.

Take your writing to the next level:

20 Editing Tips from Professional Writers

Whether you are writing a novel, essay, article, or email, good writing is an essential part of communicating your ideas., this guide contains the 20 most important writing tips and techniques from a wide range of professional writers..

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

Millie is ProWritingAid's Content Manager. Aa an English Literature graduate, she loves all things books and writing. When she isn't working, Millie enjoys adding to her vast indoor plant collection, dancing, re-reading books by Daphne Du Maurier, and running.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

Dramatic Irony

Dramatic Irony Definition

What is dramatic irony? Here’s a quick and simple definition:

Dramatic irony is a plot device often used in theater, literature, film, and television to highlight the difference between a character's understanding of a given situation, and that of the audience. More specifically, in dramatic irony the reader or audience has knowledge of some critical piece of information, while the character or characters to whom the information pertains are "in the dark"—that is, they do not yet themselves have the same knowledge as the audience. A straightforward example of this would be any scene from a horror film in which the audience might shout "Don't go in there!"—since that character doesn't suspect anything, but the audience already knows their fate.

Some additional key details about dramatic irony:

- This type of irony is called "dramatic" not because it has any exaggerated or tragic qualities, but because it originated in ancient Greek drama. Dramatic irony is particularly well-suited for the stage: in an ordinary play, the characters enter and exit constantly and even the scenery may change, but the audience stays in place, so at any given point their understanding of the story is bound to be more complete than any one character's understanding may be.

- Classical theatre typically employed the device to create a sense of tension—it's a very common device in tragedies. Modern-day cinema and television also often use dramatic irony to rack up laughs, since it can have a strong comedic effect.

- In the last twenty years or so, the term " irony " has become popular to describe an attitude of detachment or subversive humor. This entry isn't about that type of irony—or any of the other types of irony that exist (see more below). This entry focuses on dramatic irony as a literary device.

How to Pronounce Dramatic Irony

Here's how to pronounce dramatic irony: druh- mat -ick eye -run-ee

Dramatic Irony in Depth

Dramatic irony is used to create several layers of perspective on a single set of events: some characters know very little, some know quite a lot, and the audience in most cases knows the fullest version of the story. This device allows the audience to perceive the events in many different ways at once, and to appreciate the ways in which certain slight deficits of information can create vastly different responses to the same set of events. Sometimes these differences are comical, and sometimes they are painful and tragic. It's funny to watch Regina from Mean Girls stuff down "weight loss bars" we really know are weight gain bars, but it is painful to watch Snow White unknowingly bite into an apple that we the audience know is poisoned.

When Characters are in on the Dramatic Irony

In some literary works, one of the characters knows much more than the others, and so becomes a kind of secondary audience, displaying the pleasures and misunderstandings of dramatic irony directly on the stage. For instance, In Oscar Wilde's The Importance of Being Earnest , only Algernon and the audience know that Jack and Ernest are really one and the same person (or, rather, that Jack has invented Ernest). Algernon's amusement at the mishaps that ensue from this lie mirrors the audience's delight.

How Dramatic Irony Relates to Other Types of Irony

Irony is a broad term that encompasses quite a few types of irony, which we describe below. To better understand dramatic irony, it's helpful to compare it briefly with the other types of irony, each of which has a separate meaning and uses.

Dramatic Irony vs. Irony

Generally speaking, irony is a disconnect between appearance and reality which points toward a greater insight. Aristotle described irony in loftier terms as a “dissembling toward the inner core of truth.” Dramatic irony fits under this broader definition, since it involves a character having a disconnect between what they perceive (which is an incomplete version of the story) and reality (about which the audience, and perhaps other characters, have knowledge). Therefore, every example of dramatic irony is also an example of irony, but not every example of irony is an example of dramatic irony.

Dramatic Irony vs. Verbal Irony