The top 10 journal articles of 2020

In 2020, APA’s 89 journals published more than 5,000 articles—the most ever and 25% more than in 2019. Here’s a quick look at the 10 most downloaded to date.

Vol. 52 No. 1 Print version: page 24

1. Me, My Selfie, and I: The Relations Between Selfie Behaviors, Body Image, Self-Objectification, and Self-Esteem in Young Women

Veldhuis, j., et al..

Young women who appreciate their bodies and consider them physical objects are more likely to select, edit, and post selfies to social media, suggests this study in Psychology of Popular Media (Vol. 9, No. 1). Researchers surveyed 179 women, ages 18 to 25, on how often they took selfies, how they selected selfies to post, how often they used filters and editing techniques, and how carefully they planned their selfie postings. They also assessed participants’ levels of body appreciation and dissatisfaction, self-objectification, and self-esteem. Higher levels of self-objectification were linked to more time spent on all selfie behaviors, while body appreciation was related to more time spent selecting selfies to post, but not frequency of taking or editing selfies. Body dissatisfaction and self-esteem were not associated with selfie behaviors. DOI: 10.1037/ppm0000206

2. A Closer Look at Appearance and Social Media: Measuring Activity, Self-Presentation, and Social Comparison and Their Associations With Emotional Adjustment

Zimmer-gembeck, m. j., et al..

This Psychology of Popular Media (online first publication) article presents a tool to assess young people’s preoccupation with their physical appearance on social media. Researchers administered a 21-item survey about social media to 281 Australian high school students. They identified 18 items with strong inter-item correlation centered on three categories of social media behavior: online self-presentation, appearance-related online activity, and appearance comparison. In a second study with 327 Australian university students, scores on the 18-item survey were found to be associated with measures of social anxiety and depressive symptoms, appearance-related support from others, general interpersonal stress, coping flexibility, sexual harassment, disordered eating, and other factors. The researchers also found that young women engaged in more appearance-related social media activity and appearance comparison than did young men. DOI: 10.1037/ppm0000277

3. The Novel Coronavirus (COVID-2019) Outbreak: Amplification of Public Health Consequences by Media Exposure

Garfin, d. r., et al..

Repeated media exposure to the COVID-19 pandemic may be associated with psychological distress and other public health consequences, according to this commentary in Health Psychology (Vol. 39, No. 5). The authors reviewed research about trends in health behavior and psychological distress as a response to media coverage of crises, including terrorist attacks, school shootings, and disease outbreaks. They found that repeated media exposure to collective crises was associated with increased anxiety and heightened acute and post-traumatic stress, with downstream effects on health outcomes such as new incidence of cardiovascular disease. Moreover, misinformation can further amplify stress responses and lead to misplaced or misguided health-protective and help-seeking behaviors. The authors recommended public health agencies use social media strategically, such as with hashtags, to keep residents updated during the pandemic. They also urged the public to avoid sensationalism and repeated coverage of the same information. DOI: 10.1037/hea0000875

4. Barriers to Mental Health Treatment Among Individuals With Social Anxiety Disorder and Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Goetter, e. m., et al..

This study in Psychological Services (Vol. 17, No. 1) indicates that 3 in 4 people who suffer from anxiety do not receive proper care. Researchers recruited 226 participants in the United States who were previously diagnosed with social anxiety disorder or generalized anxiety disorder and assessed their symptom severity and asked them to self-report any barriers to treatment. Shame and stigma were the highest cited barriers, followed by logistical and financial barriers and not knowing where to seek treatment. Participants with more severe symptoms reported more barriers to treatment than those with milder symptoms. Racial and ethnic minorities reported more barriers than racial and ethnic majorities even after controlling for symptom severity. The researchers called for increased patient education and more culturally sensitive outreach to reduce treatment barriers. DOI: 10.1037/ser0000254

5. The Construction of “Critical Thinking”: Between How We Think and What We Believe

This History of Psychology (Vol. 23, No. 3) article examines the emergence of “critical thinking” as a psychological concept. The author describes how, between World War I and World War II in the United States, the concept emerged out of growing concerns about how easily people’s beliefs could be changed and was constructed in a way that was independent of what people believed. The author delves into how original measurements of critical thinking avoided assumptions about the accuracy of specific real-world beliefs and details how subsequent critical thinking tests increasingly focused on logical abilities, often favoring outcome (what we believe) over process (how we think). DOI: 10.1037/hop0000145

6. Treatment of Alcohol Use Disorder: Integration of Alcoholics Anonymous and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Breuninger, m. m., et al..

This article in Training and Education in Professional Psychology (Vol. 14, No. 1) details how to work with alcohol use disorder patients who are participating in both cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and Alcoholics Anonymous (AA). The authors point to distinctions between AA and CBT: The goal of AA is total abstinence and the primary therapeutic relationship is with a peer in recovery, while CBT takes a less absolute approach and the primary relationship is with a psychotherapist. The authors also point to commonalities: both approaches emphasize identifying and replacing dysfunctional beliefs and place value in social support. The authors recommend clinicians and trainees become more educated about AA and recommend a translation of the 12-step language into CBT terminology to bridge the gap. DOI: 10.1037/tep0000265

7. Positivity Pays Off: Clients’ Perspectives on Positive Compared With Traditional Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Depression

Geschwind, n., et al..

Positive cognitive behavioral therapy, a version of CBT focused on exploring exceptions to the problem rather than the problem itself, personal strengths, and embracing positivity, works well to counter depressive symptoms and build well-being, according to this study in Psychotherapy (Vol. 57, No. 3). Participants received a block of eight sessions of traditional CBT and a block of eight sessions of positive CBT. Researchers held in-depth interviews with 12 of these participants. Despite initial skepticism, most participants reported preferring positive CBT but indicated experiencing a steeper learning curve than with traditional CBT. Researchers attributed positive CBT’s favorability to four factors: feeling empowered, benefiting from effects of positive emotions, learning to appreciate baby steps, and rediscovering optimism as a personal strength. DOI: 10.1037/pst0000288

8. Targeted Prescription of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Versus Person-Centered Counseling for Depression Using a Machine Learning Approach

Delgadillo, j., & gonzalez salas duhne, p..

Amachine learning algorithm can identify which patients would derive more benefit from cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) versus counseling for depression, suggests research in this Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology (Vol. 88, No. 1) article. Researchers retrospectively explored data from 1,085 patients in the United Kingdom treated with either CBT or counseling for depression and discovered six patient characteristics—age, employment status, disability, and three diagnostic measures of major depression and social adjustment—relevant to developing an algorithm for prescribing the best approach. The researchers then used the algorithm to determine which therapy would work best for an additional 350 patients with depression. They found that patients receiving their optimal treatment type were twice as likely to improve significantly. DOI: 10.1037/ccp0000476

9. Traumatic Stress in the Age of COVID-19: A Call to Close Critical Gaps and Adapt to New Realities

Horesh, d., & brown, a. d..

This article in Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy (Vol. 12, No. 4) argues that COVID-19 should be examined from a post-traumatic stress perspective. The authors call for mental health researchers and clinicians to develop better diagnoses and prevention strategies for COVID-related traumatic stress; create guidelines and talking points for the media and government officials to use when speaking to an anxious, and potentially traumatized, public; and provide mental health training to professionals in health care, education, childcare, and occupational support in order to reach more people. DOI: 10.1037/tra0000592

10. Emotional Intelligence Predicts Academic Performance: A Meta-Analysis

Maccann, c., et al..

Students with high emotional intelligence get better grades and score higher on standardized tests, according to the research presented in this article in Psychological Bulletin (Vol. 146, No. 2). Researchers analyzed data from 158 studies representing more than 42,529 students—ranging in age from elementary school to college—from 27 countries. The researchers found that students with higher emotional intelligence earned better grades and scored higher on achievement tests than those with lower emotional intelligence. This finding was true even when controlling for intelligence and personality factors, and the association held regardless of age. The researchers suggest that students with higher emotional intelligence succeed because they cope well with negative emotions that can harm academic performance; they form stronger relationships with teachers, peers, and family; and their knowledge of human motivations and socialinteractions helps them understand humanities subject matter. DOI: 10.1037/bul0000219

5 interviews to listen to now

Psychology’s most innovative thinkers are featured on APA’s Speaking of Psychology podcast , which highlights important research and helps listeners apply psychology to their lives. The most popular episodes of 2020, as measured by the number of downloads in the first 30 days, were:

- How to have meaningful dialogues despite political differences , with Tania Israel, PhD

- Canine cognition and the survival of the friendliest , with Brian Hare, PhD

- The challenges faced by women in leadership , with Alice Eagly, PhD

- How to choose effective, science-based mental health apps , with Stephen Schueller, PhD

- Psychedelic therapy , with Roland Griffiths, PhD

Listen to all of the Speaking of Psychology episodes .

Contact APA

You may also like.

Science News

These are the most-read science news stories of 2020.

When squeezed to high pressure between two diamonds (shown), a material made of carbon, sulfur and hydrogen can transmit electricity without resistance at room temperature. The discovery ranked among Science News ' most popular in 2020.

Adam Fenster

Share this:

By Cassie Martin

December 31, 2020 at 8:00 am

Science News drew over 22 million visitors to our website this year. Our COVID-19 coverage was most popular. Here’s a recap of the other most-read news stories and long reads of 2020.

Top news stories

1. In a first, a person’s immune system fought HIV — and won

Scientists analyzed billions of cells from two people with HIV who don’t require medication to keep the virus under control. What the team found was astonishing: One person had no working copies of HIV in any of the cells, while the other person had just one working copy. What’s more, that one copy was imprisoned in tightly wound DNA.

2. The first room-temperature superconductor has finally been found

Up to 15° Celsius, a material made of carbon, sulfur and hydrogen can conduct electricity without resistance. While the room-temperature superconductor works only at high pressures, the discovery brings scientists a step closer to realizing a more energy-efficient future .

3. Astronomers have found the edge of the Milky Way at last

Computer simulations and observations of nearby galaxies have revealed that the Milky Way stretches 1.9 million light-years across. The measurement could help tease out how massive the galaxy is and exactly how many galaxies orbit it .

4. More ‘murder hornets’ are turning up. Here’s what you need to know

An invasion of Asian giant hornets into North America could spell trouble for honeybees. But the threat that the world’s largest hornet species poses to people is minimal .

5. A star orbiting the Milky Way’s black hole validates Einstein

The odd orbit of a star around the supermassive black hole at the Milky Way’s center confirms Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity. Rather than tracing out a single ellipse, the star’s orbit rotates over time — the result of the black hole warping spacetime .

Favorite visualization

“ A new 3-D map illuminates the ‘little brain’ within the heart ” ( SN: 6/2/20 ) enthralled online readers. An unprecedented view of the heart’s nerve cell cluster could help scientists better understand what those cells do and perhaps lead to targeted therapies for heart diseases.

Top feature stories

1. After the Notre Dame fire, scientists get a glimpse at the cathedral’s origins

A fire that ripped through Paris’ Notre Dame cathedral in April 2019 gave scientists the opportunity to dig into the cathedral’s history and study the building’s materials , including to learn more about climate change.

2. New fleets of private satellites are clogging the night sky

SpaceX and other private companies are planning to launch thousands of internet satellites into orbit around Earth. Hundreds of the satellites already in outer space are obstructing the view of ground-based telescopes and interfering with astronomers’ research .

3. It’s time to stop debating how to teach kids to read and follow the evidence

Research has identified the most effective approaches for teaching children how to read. Those findings could help resolve a long-standing debate that pits phonics against methods that emphasize understanding the meaning of words .

4. To fight discrimination, the U.S. census needs a different race question

The U.S. census has failed to accurately count certain minority groups. As a result, some sociologists are calling for more nuanced census questions that better reflect how respondents view themselves, as well as how society views them — a clearer metric for measuring discrimination .

5. What lifestyle changes will shrink your carbon footprint the most?

Individual actions around shelter, transportation and food can create ripple effects in society to help mitigate the effects of climate change. But to have the most impact, people need to tailor their efforts to their own circumstances .

Pandemic post

Science News has reported on the COVID-19 pandemic since it began, but none of those stories were included in our most-read lists of 2020. That’s because we think the coverage is in a league of its own.

Stories about when, during an infection, the coronavirus is most contagious and debunking the claim that the virus was made in a lab are among our most-read stories of all time. Readers also were drawn to stories about how the coronavirus spreads and COVID-19 vaccines .

As Feedback editor, I review every e-mail we receive from Science News readers. In 2020, more than a third of the thousands of e-mails that filled our inbox were about COVID-19. Hunger for information, for certainty in an uncertain time, has been insatiable.

We’ve strived to answer readers’ pandemic-related questions accurately, given the rapid pace of scientific research into the coronavirus and its effects. Some of those questions have been featured in the pages of this magazine, as well as in the Science News Coronavirus Update newsletter — a weekly e-mail that highlights the latest research, data and articles on the coronavirus and COVID-19.

Everyone at Science News thanks you, our readers, for your sharp, insightful comments and your continued support. We look forward to answering your many science questions, coronavirus-related and not, in the year ahead.

“ Radiation measurement could help guide lengthy lunar missions ” ( SN: 11/7/20, p. 5 ) incorrectly stated that the average daily exposure to cosmic radiation on the moon is 1.5 million times as high as the average daily exposure on Earth. The average daily exposure on the moon is 1,500 times as high as the average daily exposure on Earth.

Subscribers, enter your e-mail address for full access to the Science News archives and digital editions.

Not a subscriber? Become one now .

2020 year in review: Highlights from our publishing

Top 10 lists of most popular insights, overall top 10 for the year, mckinsey quarterly, mckinsey global institute, editors’ picks, diversity & inclusion, marketing, consumer, and retail, organization, strategy & corporate finance, sustainability.

A tale of 2020 in 20 McKinsey charts

Twenty images that offer a lens on 2020

Top reports this year.

Women in the Workplace 2022

State of Fashion report archive (2017-2023)

McKinsey’s Global Banking Annual Review archive: 2014 to 2022

Diversity wins: How inclusion matters

How executives can help sustain value creation for the long term

McKinsey’s Private Markets Annual Review: 2017 to 2022

New features this year, we are mckinsey, the mckinsey crossword, mckinsey’s annual reading list, 2020 favorites from gen z colleagues, new experiences this year, what now decisive actions to emerge stronger in the next normal, mckinsey for kids, do you know your life’s purpose, popular special collections this year.

The Next Normal: Emerging stronger from the coronavirus pandemic

COVID Response Center

McKinsey and the World Economic Forum

McKinsey on Books

The graduate’s guide to the world of work

Popular podcasts this year.

In this year of lockdowns, listeners tuned in to reflect and learn—how to be more productive, more inclusive, and more resilient in the face of adversity. Here are some of our most streamed podcasts of 2020.

Listen to more McKinsey Podcasts

Uncovering the state of fashion

The future of air travel

The mass personalization of change: Large-scale impact, one individual at a time

Building a business within a business: How to power continual organic growth

Getting the measure of corporate Asia

Meet Generation Z: Shaping the future of shopping

Newsletters.

The editors of our four most-read email newsletters and multimedia series chose their favorite issues of the year to share with you. Whether daily, weekly, or monthly, our newsletter offerings span functional, industry, and news-based topics—and we’re adding more in 2021.

The Shortlist

The Next Normal

The Five Fifty

Popular webinars from mckinsey live.

The COVID-19 pandemic has created and exacerbated countless challenges for leaders, organizations, and communities. In our most popular McKinsey Live webinars, McKinsey experts brought these issues to the forefront and offered perspectives on navigating beyond the crisis to shape the next normal.

Learn more about McKinsey Live

New at McKinsey blog: 2020 year in review

Mckinsey global institute: twelve highlights from our 2020 research, covid response center’s year in review.

Building a stronger, more inclusive US workforce

Leading voices on the pandemic

The emotional toll of COVID-19

Acknowledgments.

McKinsey Global Publishing would like to thank, first and foremost, the many authors of these articles and other insights for their contributions and analysis.

And we want to acknowledge the many direct contributors who offered vital energy and expertise—under extraordinary personal and professional circumstances—to the development, editing, risk review, copyediting, fact checking, data visualization, design, production, and dissemination of all of McKinsey’s content over the past year.

McKinsey Global Publishing

Raju Narisetti

Global Editorial Director

Lucia Rahilly

Julia Arnous, Diane Brady, Richard Bucci, Lang Davison, Tom Fleming, Roberta Fusaro, Eileen Hannigan, Heather Hanselman, Justine Jablonska, Bill Javetski, Jason Li, Cait Murphy, Josh Rosenfield, Astrid Sandoval, David Schwartz, Daniella Seiler, Mark Staples, Rick Tetzeli, Barbara Tierney, and Monica Toriello

Digital innovation and audience development

Nicole Adams, Heather Andrews, Mike Borruso, Sherri Capers, Torea Frey, Mary Halpin, Eleni Kostopoulos, and Philip Mathew

Vanessa Burke, Heather Byer, Nancy Cohn, Roger Draper, Drew Holzfeind, Julie Macias, LaShon Malone, Pamela Norton, Kanika Punwani, and Sarah Thuerk

Visual storytelling

Victor Cuevas, Nicole Esquerre, Richard Johnson, Maya Kaplun, Stephen Landau, Janet Michaud, Matthew Perry, Dan Redding, Jonathon Rivait, Dan Spector, and Nathan Wilson

Editorial and digital production

Michael Allen, Matt Baumer, Elana Brown, Andrew Cha, Paromita Ghosh, Gwyn Herbein, Chris Konnari, Milva Mantilla, Katrina Parker, Charmaine Rice, Dana Sand, Katie Shearer, Venetia Simcock, Chandan Srivastava, Sean Stebner, Sneha Vats, Pooja Yadav, and Belinda Yu

Social media/video

Devin Brown, Chelsea Bryan, Mona Hamouly, Lauren Holmes, Simon London, Puneet Mishra, Kathleen O’Leary, Elizabeth Schaub, and Rita Zonius

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- Virtual Tour

- Staff Directory

- En Español

You are here

Nih research matters.

December 22, 2020

2020 Research Highlights — Promising Medical Findings

Results with potential for enhancing human health.

With NIH support, scientists across the United States and around the world conduct wide-ranging research to discover ways to enhance health, lengthen life, and reduce illness and disability. Groundbreaking NIH-funded research often receives top scientific honors. In 2020, these honors included one of NIH’s own scientists and another NIH-supported scientist who received Nobel Prizes . Here’s just a small sample of the NIH-supported research accomplishments in 2020.

Full 2020 NIH Research Highlights List

20200929-covid.jpg

New approaches to COVID-19

As the global pandemic unfolded, researchers worked at unprecedented speed to develop new treatments and vaccines. Scientists studied antibodies from the blood of people who recovered from COVID-19 and identified potent, diverse ones that neutralize SARS-CoV-2 . Some antibody treatments have now been given emergency use authorization by the FDA, with many others in development . However, such antibodies—called monoclonal antibodies—are difficult to produce and must be given intravenously. NIH-researchers have been pursuing other approaches, including using antibodies from llamas , which are only about a quarter of the size of a typical human antibody and could be delivered directly to the lungs using an inhaler. Computer-designed “miniproteins” and other antiviral compounds are also under investigation.

20200622-mosquito.jpg

Universal mosquito vaccine tested

Most mosquito bites are harmless. But some mosquitoes carry pathogens, like bacteria and viruses, that can be deadly. A small trial showed that a vaccine against mosquito saliva—designed to provide broad protection against mosquito-borne diseases—is safe and causes a strong immune response in healthy volunteers. More studies are needed to test its effectiveness against specific diseases.

20201006-knee-stock.jpg

Machine learning detects early signs of osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis is the most common type of arthritis. It results when cartilage, the tissue that cushions the ends of the bones, breaks down. People with osteoarthritis can have joint pain, stiffness, and swelling. Some develop serious pain and disability from the disease. Using artificial intelligence and MRI scans, scientists identified signs of osteoarthritis three years before diagnosis. The results suggest a way to identify people who may benefit from early interventions.

20201103-eye.jpg

Advances in restoring vision

Several common eye diseases, such as age-related macular degeneration and retinitis pigmentosa, damage the retina, the light-sensitive tissue in the eye. They can eventually lead to vision loss. Two studies looked at ways to restore vision in mouse models. Researchers reprogrammed skin cells into light-sensing eye cells that restored sight in mice. The technique may lead to new approaches for modeling and treating eye diseases. Other scientists restored vision in blind mice by using gene therapy to add a novel light-sensing protein to cells in the retina. The therapy will soon be tested in people.

20200107-aging.jpg

Blood protein signatures change across lifespan

The bloodstream touches all the tissues of the body. Because of the constant flow of proteins through the body, some blood tests measure specific proteins to help diagnose diseases. Researchers determined that the levels of nearly 400 proteins in the blood can be used to determine people’s age and relative health. More research is needed to understand if these protein signatures could help identify people at greater risk of age-related diseases.

20201027-hiv-thumb.jpg

Understanding HIV’s molecular mechanisms

More than a million people nationwide are living with HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. HIV attacks the immune system by destroying immune cells vital for fighting infection. Researchers uncovered key steps in HIV replication by reconstituting and watching events unfold outside the cell. The system may be useful for future studies of these early stages in the HIV life cycle. In other work, experimental treatments in animal models of HIV led to the viruses emerging from their hiding places inside certain cells—a first step needed to make HIV vulnerable to the immune system.

20200225-parkinsons.jpg

Test distinguishes Parkinson’s disease from related condition

A protein called alpha-synuclein plays a major role in Parkinson’s disease as well as other brain disorders. Early symptoms of Parkinson’s disease and another disease involving alpha-synuclein, multiple system atrophy, can be similar. Researchers created a test using cerebrospinal fluid that can distinguish between these two diseases with 95% accuracy. The results have implications for the early diagnosis and treatment of these conditions and may help in the development of new targeted therapies.

20200114-cream.jpg

Understanding allergic reactions to skin care products

Personal care products like makeup, skin cream, and fragrances commonly cause rashes called allergic contact dermatitis. It’s not well understood how chemical compounds in personal care products trigger such allergic reactions. Scientists gained new insight into how personal care products may cause immune responses that lead to allergic responses in some people. Understanding how compounds in these products trigger immune reactions could lead to new ways to prevent or treat allergic contact dermatitis.

Connect with Us

- More Social Media from NIH

Select Your Interests

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

- Download PDF

- Share X Facebook Email LinkedIn

- Permissions

Older Adults and the Mental Health Effects of COVID-19

- 1 McLean Hospital, Belmont, Massachusetts

- 2 Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts

- 3 University of California, San Diego, La Jolla

- 4 University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

- Viewpoint Mental Health Disorders Related to COVID-19–Related Deaths Naomi M. Simon, MD, MSc; Glenn N. Saxe, MD; Charles R. Marmar, MD JAMA

- Viewpoint Addressing the Long-term Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Children and Families Tumaini R. Coker, MD, MBA; Tina L. Cheng, MD, MPH; Marci Ybarra, MSW, PhD JAMA

- Viewpoint The Mental Health Consequences of COVID-19 and Physical Distancing Sandro Galea, MD; Raina M. Merchant, MD; Nicole Lurie, MD JAMA Internal Medicine

- Viewpoint Meeting the Care Needs of Older Adults Isolated at Home During the COVID-19 Pandemic Michael A. Steinman, MD; Laura Perry, MD; Carla M. Perissinotto, MD, MHS JAMA Internal Medicine

- Original Investigation Delirium in Older Patients With COVID-19 Presenting to the Emergency Department Maura Kennedy, MD, MPH; Benjamin K. I. Helfand, MSc; Ray Yun Gou, MA; Sarah L. Gartaganis, MSW, MPH; Margaret Webb, BA; J. Michelle Moccia, DNP, ANP-BC, GS-C; Stacey N. Bruursema, LMSW-C; Belinda Dokic, MHA; Brigid McCulloch, DO; Hope Ring, MD; Justin D. Margolin, BS; Ellen Zhang, BA; Robert Anderson, MD; Rhonda L. Babine, MS, APRN, ACNS-BC; Tammy Hshieh, MD, MPH; Ambrose H. Wong, MD, MSEd; R. Andrew Taylor, MD, MHS; Kathleen Davenport, MD; Brittni Teresi, BA; Tamara G. Fong, MD, PhD; Sharon K. Inouye, MD, MPH JAMA Network Open

- Viewpoint The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak and Mental Health Doron Amsalem, MD; Lisa B. Dixon, MD; Yuval Neria, PhD JAMA Psychiatry

As the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) began to spread in the US in early 2020, older adults experienced disproportionately greater adverse effects from the pandemic including more severe complications, higher mortality, concerns about disruptions to their daily routines and access to care, difficulty in adapting to technologies like telemedicine, and concerns that isolation would exacerbate existing mental health conditions. Older adults tend to have lower stress reactivity, and in general, better emotional regulation and well-being than younger adults, 1 but given the scale and magnitude of the pandemic, there was concern about a mental health crisis among older adults. The concern pertained to older adults both at home and in residential care facilities, where contact with friends, family, and caregivers became limited. The early data suggest a much more nuanced picture. This Viewpoint summarizes evidence suggesting that, counter to expectation, older adults as a group may be more resilient to the anxiety, depression, and stress-related mental health disorders characteristic of younger populations during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Approximately 8 months into the pandemic, multiple studies have indicated that older adults may be less negatively affected by mental health outcomes than other age groups. In August 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published a survey, conducted June 24-30, 2020, of 5412 community-dwelling adults across the US, 2 noting that the 933 participants aged 65 years or older reported significantly lower percentages of anxiety disorder (6.2%), depressive disorder (5.8%), or trauma- or stress-related disorder (TSRD) (9.2%) than participants in younger age groups. According to the report, of the 731 participants aged 18 through 24 years, 49.1% reported anxiety disorder; 52.3%, depressive disorder; and 46%, TSRD. Of the 1911 participants aged 25 through 44 years, 35.3% reported anxiety disorder; 32.5%, depressive disorder; and 36% for TSRD. Of the 895 participants aged 45 through 64 years, 16.1% reported anxiety disorder; 14.4%, depressive disorder; and 17.2%, TSRD. Older adults, compared with other age groups, also reported lower rates of new or increased substance use and suicidal ideation in the preceding 30 days, with rates of 3% and 2%, respectively.

These findings are similar to other reports from high-income countries. A cross-sectional study involving 3840 community-dwelling older adults aged 18 through 80 years from Spain noted that older age (60-80 years) compared with younger age (40-59 years) was associated with lower rates of anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). 3 In this study, women had higher prevalence of anxiety, PTSD, and depressive symptoms than men. A study involving 776 community-dwelling US and Canadian adults who used a 7-day daily diary to track affect and stress found that older adults (>60 years; n = 193), compared with younger adults (18-39 years; n = 330) and middle-aged adults (40-59 years; n = 253) had less negative affect and more positive affect and more often reported positive daily events than the younger groups, despite similar level of perceived stress. 4 A longitudinal study involving 1679 community-dwelling older adults (65-102 years) in the Netherlands found that although loneliness increased after the pandemic, mental health levels remained unchanged before and after the start of the pandemic. 5

There are several caveats to consider about these data. The findings represent the experience during the first few months of the pandemic. The longer-term effects of COVID-19, especially in countries like the US with very high rates of disease, remain unclear. Long-term population-level stressors can increase the rates of mental health conditions such as prolonged grief disorder, depression, and anxiety. Positive short-term outcomes among older adults at the population level may not necessarily capture the heterogeneity of outcomes at the level of individuals or circumscribed communities or environments (eg, nursing homes, assisted living facilities). According to the CDC report, 2 even though older adults may have better mental health outcomes than expected, those from underrepresented minorities or with lower household incomes or who are serving as unpaid caregivers are at disproportionally elevated risk of experiencing negative health outcomes. The currently available data also do not provide perspectives on subgroups of older adults like those with dementia, those caring for persons with dementia, or those residing in assisted living facilities or nursing homes. The effect of comorbid chronic medical or psychiatric conditions also remains unclear thus far.

Despite these caveats, the early findings suggest higher resilience to the mental health effects of COVID-19 at least in a proportion of community-dwelling older adults. This resilience may reflect an interaction among internal factors (eg, biological stress response, cognitive capacity, personality traits, physical health) and external resources (eg, social status, financial stability). 6

Much of the initial concern related to how older adults would respond to COVID-19 was based on how loneliness and isolation would be exacerbated as lockdown measures were implemented. The negative influence of loneliness among older adults has been well documented. However, this reaction might have been partially countered by a range of coping mechanisms. In a mixed-methods study involving 73 older adults 7 (mean age, 69.2 years) with known depression or anxiety who had demonstrated resilience (ie, no worsening of symptoms) 2 months after the start of the pandemic, investigators noted that study participants appeared to withstand the influence of isolation, especially with social connectedness and access to mental health care. However, despite this early resilience, older adults expressed concerns about their longer-term physical and financial well-being.

A cross-sectional study of 515 community-dwelling adults (20-79 years) in the US noted that the use of proactive precautionary measures such as avoiding people who cough, unnecessary travel, and use of public transportation or public places 8 was associated with lower COVID-related anxiety among older adults. The quality rather than the number of social connections may also be a factor. Thus, for older adults experiencing isolation, having more close or meaningful relationships may be protective, rather than just having more interactions with others. 5 Maintaining these connections during the pandemic may require better ability to use technology to connect with loved ones.

An additional factor to consider is wisdom, a complex personality trait comprised of specific components, including prosocial behaviors like empathy and compassion, emotional regulation, the ability to self-reflect, decisiveness while accepting uncertainty and diversity of perspectives, social advising, and spirituality. 9 Several recent studies involving various groups of people across the adult lifespan (25-≥100 years) have shown a significant inverse correlation between loneliness and wisdom, based on validated scales for measuring these constructs. The component of wisdom that is correlated most strongly (and inversely) with loneliness is compassion. Other data also suggest that enhancing compassion may reduce loneliness and promote greater well-being. 10 Cross-sectional studies show higher levels of wisdom, especially the compassion component, in older than in younger adults. Additional studies are needed to shed more light on risk and protective factors as well as the nature of mediating and moderating relationships among these factors with respect to the mental health consequences of COVID-19 among older adults. There should also be more longitudinal studies on mental health trajectories among specific high-risk populations like older individuals in assisted living facilities and nursing homes.

The data from various studies contrast the numerous personal stories about how difficult the pandemic has been for the older population. This divergence likely represents the heterogeneity that is a hallmark of aging. Also, resilience captured at the population level may not translate to individuals in specific circumstances. Thus far, there is not a clear understanding of which risk factors and protective factors are the strongest determinants of mental health outcomes, although these may vary from person to person.

Many older adults do not have the resources required to deal with the stress of COVID-19. This may include material (eg, lack of access to smart technology), social (eg, few family members or friends), or cognitive or biological (eg, inability to engage in physical exercise or participate in activities or routines) resources. Clinicians and caregivers must estimate resource availability and consider how the absence of resources can be mitigated for a given individual and family. Of particular importance is the role of technology, which has emerged as an important factor for maintaining social connection as well as accessing mental health services.

Moreover, clinicians must recognize the importance of nonpharmacological approaches, which are more effective than pharmacotherapy in the treatment of chronic stress, anxiety, and prolonged grief. Such approaches include manualized therapies such as cognitive behavior therapy, as well as promoting physical activity, greater connectedness, compassion training, and engaging in spirituality as appropriate. These approaches have also been shown to enhance coping, promote resilience, and reduce loneliness. 9

The great pandemic of 2020 has been a unique stressor that has affected communities all around the world. Yet it is noteworthy that some individual studies from different countries have shown that at least some older adults are not experiencing disproportionately increased negative mental health consequences commensurate with the elevated risks they faced during the first few months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Understanding the factors and mechanisms that drive this resilience can guide intervention approaches for other older people and for other groups whose mental health may be more severely affected— eg, increasing components of wisdom like emotional regulation, empathy, and compassion. 10 It would also be useful to consider how technology may be leveraged to this end. However, it is critical to recognize that these apparently positive early findings notwithstanding, careful monitoring and additional research will be needed to understand the psychological and mental health effects of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic among the older population.

Corresponding Author: Ipsit V. Vahia, MD, McLean Hospital, 115 Mill St, Mail Stop 234, Belmont, MA 02478 ( [email protected] ; [email protected] ).

Published Online: November 20, 2020. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.21753

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Drs Vahia and Reynolds reported receiving honorarium, respectively, as editor and editor in chief of the American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry . Dr Jeste reported receiving a stipend as editor-in-chief of International Psychogeriatrics . No other disclosures were reported.

Additional Contributions: We thank Hailey Cray, BA, McLean Hospital, Belmont, Massachusetts, for her assistance in preparing this manuscript, for which she received no compensation.

See More About

Vahia IV , Jeste DV , Reynolds CF. Older Adults and the Mental Health Effects of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324(22):2253–2254. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.21753

Manage citations:

© 2024

Artificial Intelligence Resource Center

Cardiology in JAMA : Read the Latest

Browse and subscribe to JAMA Network podcasts!

Others Also Liked

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

Durvalumab Extends Lives of People with Early-Stage Small Cell Lung Cancer

June 25, 2024 , by Nadia Jaber

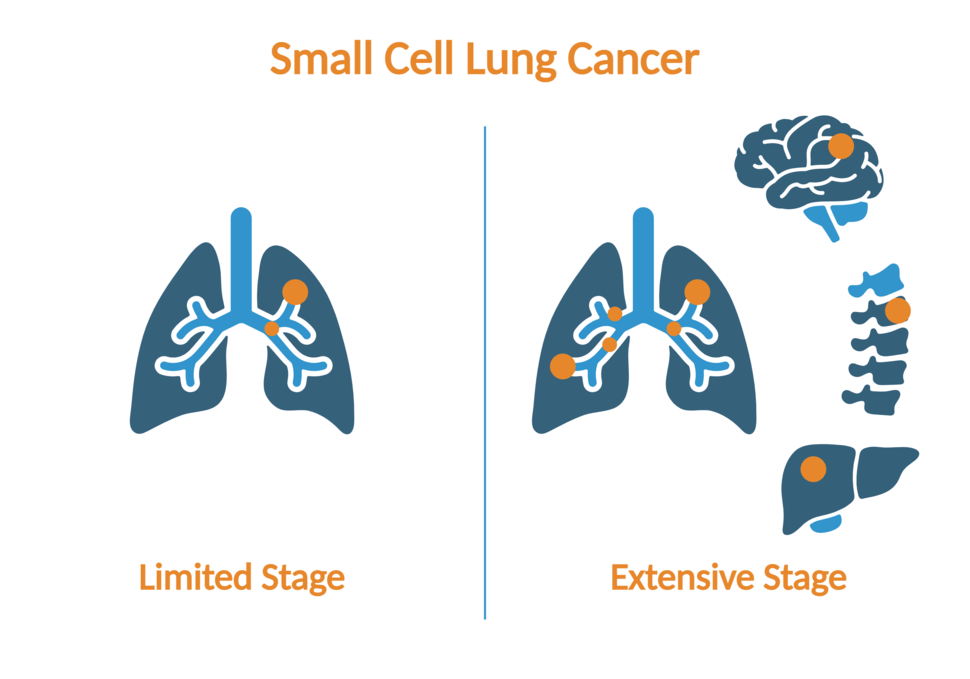

A clinical trial has shown that durvalumab (Imfinzi) helps people with limited-stage small cell lung cancer live longer. Durvalumab is already used to treat people with extensive-stage small cell lung cancer.

The immunotherapy drug durvalumab (Imfinzi) helped people with early-stage small cell lung cancer live longer, according to initial results from a large clinical trial. Durvalumab is a type of immunotherapy called an immune checkpoint inhibitor .

The standard initial treatment for early-stage (also called limited-stage) small cell lung cancer—cancer that is confined to one lung or one side of the chest—is chemotherapy and radiation given at the same time. Although this treatment tends to work well at first, the cancer often comes back quickly, at which point it has typically spread throughout the body.

“There really have not been any major advances in the treatment of limited-stage small cell lung cancer for several decades,” said the study’s leader, David Spigel, M.D., of Sarah Cannon Research Institute in Nashville, Tennessee.

In the new trial, dubbed ADRIATIC, more than 500 people with limited-stage small cell lung cancer who had finished chemotherapy and radiation were randomly assigned to receive durvalumab or a placebo for up to 2 years.

People who received durvalumab stayed in remission longer and lived substantially longer than those treated with placebo. Three years after starting the treatment, 57% of people in the durvalumab group were still alive , compared with 48% in the placebo group, Dr. Spigel reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology on June 2.

“The ADRIATIC trial is a landmark study and provides a new standard of care for patients with early-stage small cell lung cancer,” said Lauren Byers, M.D., professor of thoracic head and neck medical oncology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, at a press briefing where the study was discussed. Dr. Byers was not involved in the trial.

The findings are “definitely practice changing,” said Anish Thomas, M.D., of NCI’s Center for Cancer Research , who studies small cell lung cancer but wasn’t involved in the new trial.

“This is really encouraging for patients as well as people who are working on this cancer,” Dr. Thomas said.

Durvalumab extends overall survival and progression-free survival

Small cell lung cancer grows quickly and often spreads beyond the lungs before it is even diagnosed. While targeted therapies have had less success for small cell than for non-small cell lung cancer, immunotherapy is a somewhat different story.

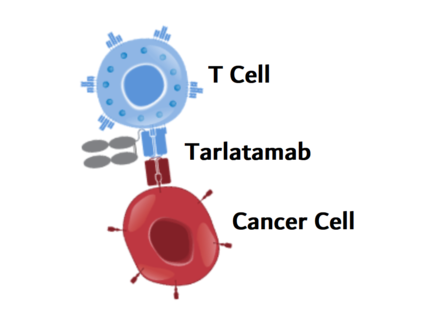

Over the past 5 years, durvalumab and two other immunotherapies— atezolizumab (Tecentriq) and tarlatamab (Imdelltra) —have been approved for the treatment of people with advanced, or extensive-stage, small cell lung cancer.

New Immunotherapy Drug Shows Promise for Small Cell Lung Cancer

In an early-stage clinical trial, tarlatamab shrank tumors that had progressed after previous treatments.

Spurred by the improvements seen with durvalumab for extensive-stage small cell lung cancer and non-small cell lung cancer, Dr. Spigel and his colleagues launched the ADRIATIC trial to see if durvalumab could improve outcomes of people with limited-stage small cell lung cancer.

All participants in the trial had cancer that had responded to standard chemotherapy and radiation.

Durvalumab was given after the standard treatment to help kill any leftover cancer cells—a strategy known as consolidation therapy . The trial was funded by AstraZeneca, the company that makes durvalumab.

Participants in the durvalumab group lived longer without their cancer growing back. Two years after the start of the trial, 46% of those in the durvalumab group and 34% in the placebo group didn’t have any sign of the cancer returning.

Durvalumab also extended the median overall survival by nearly 2 years, Dr. Spigel noted, from 33 months with placebo to 56 months with durvalumab.

That is in stark contrast to the magnitude of benefit seen in extensive-stage small cell lung cancer, Dr. Thomas emphasized. In that setting, atezolizumab and durvalumab each extended median overall survival by only 2 or 3 months, he explained.

“ADRIATIC is the first phase 3 study to establish the role of immunotherapy in [treating] limited-stage small cell lung cancer,” Dr. Spigel concluded.

However, the findings haven’t yet been peer-reviewed—meaning, evaluated for scientific quality and accuracy by other experts in the field.

Side effects of durvalumab consolidation therapy

Durvalumab, which is given every 4 weeks as an infusion, didn’t cause any unexpected side effects, Dr. Spigel noted. The side effects were typical of those seen with durvalumab and other immunotherapies, which rev up the immune system.

In particular, those in the durvalumab group experienced inflammatory conditions in the lungs, skin, and thyroid. Serious immune-related side effects occurred in 5% of people in the durvalumab group and 2% of those in the placebo group.

Durvalumab can also cause a serious and sometimes fatal lung inflammation called pneumonitis . This condition also develops frequently in people who have just received chest radiation, like the patients in this study.

In the ADRIATIC trial, 38% of people in the durvalumab group and 30% of those in the placebo group developed pneumonitis, including one participant in the durvalumab group who died of pneumonitis.

About a quarter of participants in both groups experienced a serious side effect of any kind. Side effects led 16% of patients in the durvalumab group and 11% of those in the placebo group to stop the treatment.

Next steps for small cell lung cancer research

The ADRIATIC trial is ongoing and more will be learned about durvalumab treatment, Dr. Spigel said.

In addition, another arm of the trial is evaluating the combination of durvalumab and another immunotherapy drug, tremelimumab (Imjudo) . Results from that group of 200 patients are still being collected.

Drug Combination Shrinks Small Cell Lung Cancers

When given together, topotecan and berzosertib produced lasting responses in some patients.

In the meantime, small cell lung cancer researchers are already thinking about what questions to investigate next.

“One important next step will be to understand who is benefitting the most from the addition of durvalumab and how we can start thinking about personalizing treatment for the different subtypes of small cell lung cancer,” Dr. Byers said.

Like many other kinds of cancer, small cell lung cancer can be separated into subtypes based on the molecular characteristics of the cancer cells, she explained. Some subtypes are more easily recognized by cancer-killing immune cells and may have better responses to immunotherapy, she added.

As for Dr. Thomas, his mind is on earlier detection because most small cell lung cancers are found when the disease is already widespread. If more of these cancers could be found when the disease is at an early stage, he said, patients could potentially get more benefit from durvalumab treatment.

The challenge is that low-dose CT scans , which are used to screen people at risk for lung cancer, don’t pick up small cell lung cancers early enough.

“Can we come up with methods to identify small cell [lung cancer] earlier than CT scans [can]?” Dr. Thomas asked. Given the recent progress with blood tests for early cancer detection , he said he’s hopeful that such a test will someday be developed for small cell lung cancer.

Featured Posts

June 5, 2024, by Linda Wang

May 3, 2024, by Carmen Phillips

May 1, 2024, by Edward Winstead

- Biology of Cancer

- Cancer Risk

- Childhood Cancer

- Clinical Trial Results

- Disparities

- FDA Approvals

- Global Health

- Leadership & Expert Views

- Screening & Early Detection

- Survivorship & Supportive Care

- February (6)

- January (6)

- December (7)

- November (6)

- October (7)

- September (7)

- February (7)

- November (7)

- October (5)

- September (6)

- November (4)

- September (9)

- February (5)

- October (8)

- January (7)

- December (6)

- September (8)

- February (9)

- December (9)

- November (9)

- October (9)

- September (11)

- February (11)

- January (10)

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission

Gill livingston.

a Division of Psychiatry, University College London, London, UK

d Camden and Islington NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK

Jonathan Huntley

Andrew sommerlad.

f National Ageing Research Institute and Academic Unit for Psychiatry of Old Age, University of Melbourne, Royal Melbourne Hospital, Parkville, VIC, Australia

Clive Ballard

g University of Exeter, Exeter, UK

Sube Banerjee

h Faculty of Health: Medicine, Dentistry and Human Sciences, University of Plymouth, Plymouth, UK

Carol Brayne

i Cambridge Institute of Public Health, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK

Alistair Burns

j Department of Old Age Psychiatry, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK

Jiska Cohen-Mansfield

k Department of Health Promotion, School of Public Health, Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel

l Heczeg Institute on Aging, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel

m Minerva Center for Interdisciplinary Study of End of Life, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel

Claudia Cooper

Sergi g costafreda.

n Department of Preventive and Social Medicine, Goa Medical College, Goa, India

b Dementia Research Centre, UK Dementia Research Institute, University College London, London, UK

o Institute of Neurology, National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK

Laura N Gitlin

p Center for Innovative Care in Aging, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MA, USA

Robert Howard

Helen c kales.

r Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, UC Davis School of Medicine, University of California, Sacramento, CA, USA

Mika Kivimäki

c Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, University College London, London, UK

Eric B Larson

s Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, Seattle, WA, USA

Adesola Ogunniyi

t University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria

Vasiliki Orgeta

Karen ritchie.

u Inserm, Unit 1061, Neuropsychiatry: Epidemiological and Clinical Research, La Colombière Hospital, University of Montpellier, Montpellier, France

v Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK

Kenneth Rockwood

w Centre for the Health Care of Elderly People, Geriatric Medicine Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada

Elizabeth L Sampson

e Barnet, Enfield, and Haringey Mental Health Trust, London, UK

Quincy Samus

q Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MA, USA

Lon S Schneider

x Department of Psychiatry and the Behavioural Sciences and Department of Neurology, Keck School of Medicine, Leonard Davis School of Gerontology of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Geir Selbæk

y Norwegian National Advisory Unit on Ageing and Health, Vestfold Hospital Trust, Tønsberg, Norway

z Institute of Clinical Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway

aa Geriatric Department, Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway

ab Department Psychosocial and Community Health, School of Nursing, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

Naaheed Mukadam

Associated data, executive summary.

The number of older people, including those living with dementia, is rising, as younger age mortality declines. However, the age-specific incidence of dementia has fallen in many countries, probably because of improvements in education, nutrition, health care, and lifestyle changes. Overall, a growing body of evidence supports the nine potentially modifiable risk factors for dementia modelled by the 2017 Lancet Commission on dementia prevention, intervention, and care: less education, hypertension, hearing impairment, smoking, obesity, depression, physical inactivity, diabetes, and low social contact. We now add three more risk factors for dementia with newer, convincing evidence. These factors are excessive alcohol consumption, traumatic brain injury, and air pollution. We have completed new reviews and meta-analyses and incorporated these into an updated 12 risk factor life-course model of dementia prevention. Together the 12 modifiable risk factors account for around 40% of worldwide dementias, which consequently could theoretically be prevented or delayed. The potential for prevention is high and might be higher in low-income and middle-income countries (LMIC) where more dementias occur.

Our new life-course model and evidence synthesis has paramount worldwide policy implications. It is never too early and never too late in the life course for dementia prevention. Early-life (younger than 45 years) risks, such as less education, affect cognitive reserve; midlife (45–65 years), and later-life (older than 65 years) risk factors influence reserve and triggering of neuropathological developments. Culture, poverty, and inequality are key drivers of the need for change. Individuals who are most deprived need these changes the most and will derive the highest benefit.

Policy should prioritise childhood education for all. Public health initiatives minimising head injury and decreasing harmful alcohol drinking could potentially reduce young-onset and later-life dementia. Midlife systolic blood pressure control should aim for 130 mm Hg or lower to delay or prevent dementia. Stopping smoking, even in later life, ameliorates this risk. Passive smoking is a less considered modifiable risk factor for dementia. Many countries have restricted this exposure. Policy makers should expedite improvements in air quality, particularly in areas with high air pollution.

We recommend keeping cognitively, physically, and socially active in midlife and later life although little evidence exists for any single specific activity protecting against dementia. Using hearing aids appears to reduce the excess risk from hearing loss. Sustained exercise in midlife, and possibly later life, protects from dementia, perhaps through decreasing obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk. Depression might be a risk for dementia, but in later life dementia might cause depression. Although behaviour change is difficult and some associations might not be purely causal, individuals have a huge potential to reduce their dementia risk.

In LMIC, not everyone has access to secondary education; high rates of hypertension, obesity, and hearing loss exist, and the prevalence of diabetes and smoking are growing, thus an even greater proportion of dementia is potentially preventable.

Amyloid-β and tau biomarkers indicate risk of progression to Alzheimer's dementia but most people with normal cognition with only these biomarkers never develop the disease. Although accurate diagnosis is important for patients who have impairments and functional concerns and their families, no evidence exists to support pre-symptomatic diagnosis in everyday practice.

Our understanding of dementia aetiology is shifting, with latest description of new pathological causes. In the oldest adults (older than 90 years), in particular, mixed dementia is more common. Blood biomarkers might hold promise for future diagnostic approaches and are more scalable than CSF and brain imaging markers.

Wellbeing is the goal of much of dementia care. People with dementia have complex problems and symptoms in many domains. Interventions should be individualised and consider the person as a whole, as well as their family carers. Evidence is accumulating for the effectiveness, at least in the short term, of psychosocial interventions tailored to the patient's needs, to manage neuropsychiatric symptoms. Evidence-based interventions for carers can reduce depressive and anxiety symptoms over years and be cost-effective.

Keeping people with dementia physically healthy is important for their cognition. People with dementia have more physical health problems than others of the same age but often receive less community health care and find it particularly difficult to access and organise care. People with dementia have more hospital admissions than other older people, including for illnesses that are potentially manageable at home. They have died disproportionately in the COVID-19 epidemic. Hospitalisations are distressing and are associated with poor outcomes and high costs. Health-care professionals should consider dementia in older people without known dementia who have frequent admissions or who develop delirium. Delirium is common in people with dementia and contributes to cognitive decline. In hospital, care including appropriate sensory stimulation, ensuring fluid intake, and avoiding infections might reduce delirium incidence.

Key messages

- • New evidence supports adding three modifiable risk factors—excessive alcohol consumption, head injury, and air pollution—to our 2017 Lancet Commission on dementia prevention, intervention, and care life-course model of nine factors (less education, hypertension, hearing impairment, smoking, obesity, depression, physical inactivity, diabetes, and infrequent social contact).

- • Modifying 12 risk factors might prevent or delay up to 40% of dementias.

- • Prevention is about policy and individuals. Contributions to the risk and mitigation of dementia begin early and continue throughout life, so it is never too early or too late. These actions require both public health programmes and individually tailored interventions. In addition to population strategies, policy should address high-risk groups to increase social, cognitive, and physical activity; and vascular health.

- • Aim to maintain systolic BP of 130 mm Hg or less in midlife from around age 40 years (antihypertensive treatment for hypertension is the only known effective preventive medication for dementia).

- • Encourage use of hearing aids for hearing loss and reduce hearing loss by protection of ears from excessive noise exposure.

- • Reduce exposure to air pollution and second-hand tobacco smoke.

- • Prevent head injury.

- • Limit alcohol use, as alcohol misuse and drinking more than 21 units weekly increase the risk of dementia.

- • Avoid smoking uptake and support smoking cessation to stop smoking, as this reduces the risk of dementia even in later life.

- • Provide all children with primary and secondary education.

- • Reduce obesity and the linked condition of diabetes. Sustain midlife, and possibly later life physical activity.

- • Addressing other putative risk factors for dementia, like sleep, through lifestyle interventions, will improve general health.

- • Many risk factors cluster around inequalities, which occur particularly in Black, Asian, and minority ethnic groups and in vulnerable populations. Tackling these factors will involve not only health promotion but also societal action to improve the circumstances in which people live their lives. Examples include creating environments that have physical activity as a norm, reducing the population profile of blood pressure rising with age through better patterns of nutrition, and reducing potential excessive noise exposure.

- • Dementia is rising more in low-income and middle-income countries (LMIC) than in high-income countries, because of population ageing and higher frequency of potentially modifiable risk factors. Preventative interventions might yield the largest dementia reductions in LMIC.

For those with dementia, recommendations are:

- • Post-diagnostic care for people with dementia should address physical and mental health, social care, and support. Most people with dementia have other illnesses and might struggle to look after their health and this might result in potentially preventable hospitalisations.

- • Specific multicomponent interventions decrease neuropsychiatric symptoms in people with dementia and are the treatments of choice. Psychotropic drugs are often ineffective and might have severe adverse effects.

- • Specific interventions for family carers have long-lasting effects on depression and anxiety symptoms, increase quality of life, are cost-effective and might save money.

Acting now on dementia prevention, intervention, and care will vastly improve living and dying for individuals with dementia and their families, and thus society.

Introduction

Worldwide around 50 million people live with dementia, and this number is projected to increase to 152 million by 2050, 1 rising particularly in low-income and middle-income countries (LMIC) where around two-thirds of people with dementia live. 1 Dementia affects individuals, their families, and the economy, with global costs estimated at about US$1 trillion annually. 1

We reconvened the 2017 Lancet Commission on dementia prevention, intervention, and care 2 to identify the evidence for advances likely to have the greatest impact since our 2017 paper and build on its work. Our interdisciplinary, international group of experts presented, debated, and agreed on the best available evidence. We adopted a triangulation framework evaluating the consistency of evidence from different lines of research and used that as the basis to evaluate evidence. We have summarised best evidence using, where possible, good- quality systematic reviews, meta-analyses, or individual studies, where these add important knowledge to the field. We performed systematic literature reviews and meta-analyses where needed to generate new evidence for our analysis of potentially modifiable risk factors for dementia. Within this framework, we present a narrative synthesis of evidence including systematic reviews and meta-analyses and explain its balance, strengths, and limitations. We evaluated new evidence on dementia risk in LMIC; risks and protective factors for dementia; detection of Alzheimer's disease; multimorbidity in dementia; and interventions for people affected by dementia.

Nearly all the evidence is from studies in high-income countries (HIC), so risks might differ in other countries and interventions might require modification for different cultures and environments. This notion also underpins the critical need to understand the dementias related to life-course disadvantage—whether in HICs or LMICs.

Our understanding of dementia aetiology is shifting. A consensus group, for example, has described hippocampal sclerosis associated with TDP-43 proteinopathy, as limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy (LATE) dementia, usually found in people older than 80 years, progressing more slowly than Alzheimer's disease, detectable at post-mortem, often mimicking or comorbid with Alzheimer's disease. 3 This situation reflects increasing attention as to how clinical syndromes are and are not related to particular underlying pathologies and how this might change across age. More work is needed, however, before LATE can be used as a valid clinical diagnosis.

The fastest growing demographic group in HIC is the oldest adults, those aged over 90 years. Thus a unique opportunity exists to focus on both human biology, in this previously rare population, as well as on meeting their needs and promoting their wellbeing.

Prevention of dementia

The number of people with dementia is rising. Predictions about future trends in dementia prevalence vary depending on the underlying assumptions and geographical region, but generally suggest substantial increases in overall prevalence related to an ageing population. For example, according to the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study, the global age-standardised prevalence of dementia between 1990 and 2016 was relatively stable, but with an ageing and bigger population the number of people with dementia has more than doubled since 1990. 4

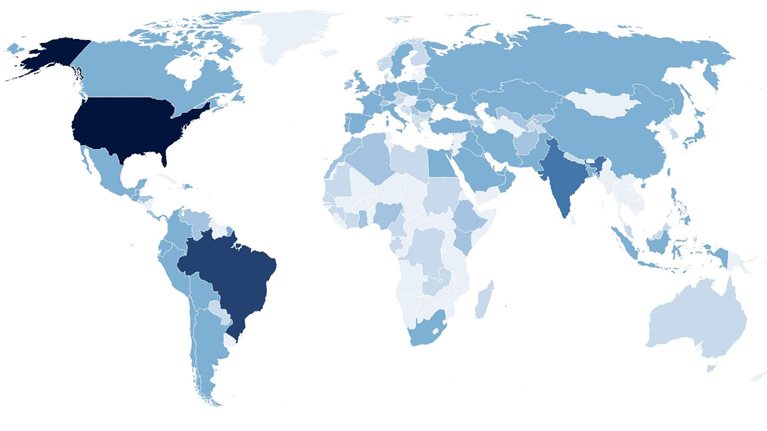

However, in many HIC such as the USA, the UK, and France, age-specific incidence rates are lower in more recent cohorts compared with cohorts from previous decades collected using similar methods and target populations 5 ( figure 1 ) and the age-specific incidence of dementia appears to decrease. 6 All-cause dementia incidence is lower in people born more recently, 7 probably due to educational, socio-economic, health care, and lifestyle changes. 2 , 5 However, in these countries increasing obesity and diabetes and declining physical activity might reverse this trajectory. 8 , 9 In contrast, age-specific dementia prevalence in Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong, and Taiwan looks as if it is increasing, as is Alzheimer's in LMIC, although whether diagnostic methods are always the same in comparison studies is unclear. 5 , 6 , 7

Incidence rate ratio comparing new cohorts to old cohorts from five studies of dementia incidence 5

IIDP Project in USA and Nigeria, Bordeaux study in France, and Rotterdam study in the Netherlands adjusted for age. Framingham Heart Study, USA, adjusted for age and sex. CFAS in the UK adjusted for age, sex, area, and deprivation. However, age-specific dementia prevalence is increasing in some other countries. IID=Indianapolis–Ibadan Dementia. CFAS=Cognitive Function and Ageing Study. Adapted from Wu et al, 5 by permission of Springer Nature.

Modelling of the UK change suggests a 57% increase in the number of people with dementia from 2016 to 2040, 70% of that expected if age-specific incidence rates remained steady, 10 such that by 2040 there will be 1·2 million UK people with dementia. Models also suggest that there will be future increases both in the number of individuals who are independent and those with complex care needs. 6

In our first report, the 2017 Commission described a life-course model for potentially modifiable risks for dementia. 2 Life course is important when considering risk, for example, obesity and hypertension in midlife predict future dementia, but both weight and blood pressure usually fall in later life in those with or developing dementia, 9 so lower weight and blood pressure in later life might signify illness, not an absence of risk. 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 We consider evidence on other potential risk factors and incorporate those with good quality evidence in our model.

Figure 2 summarises possible mechanisms of protection from dementia, some of which involve increasing or maintaining cognitive reserve despite pathology and neuropathological damage. There are different terms describing the observed differential susceptibility to age-related and disease-related changes and these are not used consistently. 15 , 16 A consensus paper defines reserve as a concept accounting for the difference between an individual's clinical picture and their neuropathology. It, divides the concept further into neurobiological brain reserve (eg, numbers of neurones and synapses at a given timepoint), brain maintenance (as neurobiological capital at any timepoint, based on genetics or lifestyle reducing brain changes and pathology development over time) and cognitive reserve as adaptability enabling preservation of cognition or everyday functioning in spite of brain pathology. 15 Cognitive reserve is changeable and quantifying it uses proxy measures such as education, occupational complexity, leisure activity, residual approaches (the variance of cognition not explained by demographic variables and brain measures), or identification of functional networks that might underlie such reserve. 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20

Possible brain mechanisms for enhancing or maintaining cognitive reserve and risk reduction of potentially modifiable risk factors in dementia

Early-life factors, such as less education, affect the resulting cognitive reserve. Midlife and old-age risk factors influence age-related cognitive decline and triggering of neuropathological developments. Consistent with the hypothesis of cognitive reserve is that older women are more likely to develop dementia than men of the same age, probably partly because on average older women have had less education than older men. Cognitive reserve mechanisms might include preserved metabolism or increased connectivity in temporal and frontal brain areas. 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 People in otherwise good physical health can sustain a higher burden of neuropathology without cognitive impairment. 22 Culture, poverty, and inequality are important obstacles to, and drivers of, the need for change to cognitive reserve. Those who are most deprived need these changes the most and will derive the highest benefit from them.

Smoking increases air particulate matter, and has vascular and toxic effects. 23 Similarly air pollution might act via vascular mechanisms. 24 Exercise might reduce weight and diabetes risk, improve cardiovascular function, decrease glutamine, or enhance hippocampal neurogenesis. 25 Higher HDL cholesterol might protect against vascular risk and inflammation accompanying amyloid-β (Aβ) pathology in mild cognitive impairment. 26

Dementia in LMIC

Numbers of people with dementia in LMIC are rising faster than in HIC because of increases in life expectancy and greater risk factor burden. We previously calculated that nine potentially modifiable risk factors together are associated with 35% of the population attributable fraction (PAFs) of dementia worldwide: less education, high blood pressure, obesity, hearing loss, depression, diabetes, physical inactivity, smoking, and social isolation, assuming causation. 2 Most research data for this calculation came from HIC and there is a relative absence of specific evidence of the impact of risk factors on dementia risk in LMIC, particularly from Africa and Latin America. 27

Calculations considering country-specific prevalence of the nine potentially modifiable risk factors indicate PAF of 40% in China, 41% in India and 56% in Latin America with the potential for these numbers to be even higher depending on which estimates of risk factor frequency are used. 28 , 29 Therefore a higher potential for dementia prevention exists in these countries than in global estimates that use data predominantly from HIC. If not currently in place, national policies addressing access to education, causes and management of high blood pressure, causes and treatment of hearing loss, socio-economic and commercial drivers of obesity, could be implemented to reduce risk in many countries. The higher social contact observed in the three LMIC regions provides potential insights for HIC on how to influence this risk factor for dementia. 30 We could not consider other risk factors such as poor health in pregnancy of malnourished mothers, difficult births, early life malnutrition, survival with heavy infection burdens alongside malaria and HIV, all of which might add to the risks in LMIC.

Diabetes is very common and cigarette smoking is rising in China while falling in most HIC. 31 A meta-analysis found variation of the rates of dementia within China, with a higher prevalence in the north and lower prevalence in central China, estimating 9·5 million people are living with dementia, whereas a slightly later synthesis estimated a higher prevalence of around 11 million. 30 , 32 These data highlight the need for more focused work in LMIC for more accurate estimates of risk and interventions tailored to each setting.

Specific potentially modifiable risk factors for dementia