Essay on Coronavirus Prevention

500+ words essay on coronavirus prevention.

The best way of coronavirus prevention is not getting it in the first place. After extensive research, there are now COVID-19 vaccines available to the public. Everyone must consider getting it to lead healthy lives. Further, we will look at some ways in this essay in how one can lower their chances of getting the virus or stopping it from spreading.

The Spread of Coronavirus

The COVID-19 virus spreads mainly via droplets that are sent out by people while talking, sneezing, or coughing. However, they do not generally stay in the air for long. Similarly, they cannot go farther than 6 feet.

However, this virus can also travel via tiny aerosol particles that have the capacity to linger for around three hours. Likewise, they may also travel farther away. Therefore, it is essential to wear a face covering.

The face mask can prevent you from getting the virus as it helps you to avoid breathing it in. Further, one can also catch this virus if they touch something that an infected person has touched and then they touch their eyes, mouth, or nose.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

How to Prevent Coronavirus

The first and foremost thing for coronavirus prevention is that everyone must do is get the vaccine as soon as it is their turn. It helps you avoid the virus or prevent you from falling seriously ill. Apart from this, we must not forget to take other steps as well to reduce the risk of getting the virus.

It includes avoiding close contact with people who are sick or are showing symptoms. Make sure you are at least 6 feet away from them. Similarly, you also remain at the same distance as others if you have contracted the virus.

What’s important to know is that you may have COVID-19 and spread it to others even if you are not showing any symptoms or aren’t aware that you have COVID-19. Moreover, we must avoid crowds and indoor places that are not well-ventilated.

Most importantly, keep washing your hands frequently with soap and water. If these are not present, carry an alcohol-based sanitiser with you. It must have a minimum amount of 60% alcohol.

In addition, wearing a face mask is of utmost importance in public spaces. Such places come with a higher risk of transmission of the virus. Thus, use surgical masks if they are available.

It is important to cover your mouth and nose when you are coughing or sneezing. If you don’t have a tissue, cover it with your elbow. Do not touch your eyes, nose and mouth. Likewise, do not share dishes, towels, glasses and other household items with a sick person.

Do not forget to clean and disinfect surfaces that people touch frequently like electronics, switchboards, counters, doorknobs, and more. Also, stay at home if you feel sick and do not take public transport as well.

To sum it up, coronavirus prevention can be done easily. We must work together to create a safe environment for everyone to live healthily. Make sure to do your bit so that everyone can stay safe and fit and things may return to normal like before.

FAQ of Essay on Coronavirus Prevention

Question 1: How long does it take for coronavirus symptoms to appear?

Answer 1: It may take around five to six days on average when someone gets infected with the virus. But, some people also take around 14 days.

Question 2: What are some coronavirus prevention tips?

Answer 2: One must get the vaccine as soon as possible. Further, always wear a mask properly and sanitize or wash your hands. Clean or disinfect areas that people touch frequently like door handles, electronics, and more. Always cover your mouth when sneezing or coughing and maintain physical distancing.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

The 12 Best COVID-19 Prevention Strategies

BY CARRIE MACMILLAN , JEREMY LEDGER October 12, 2020

Note: Information in this article was accurate at the time of original publication. Because information about COVID-19 changes rapidly, we encourage you to visit the websites of the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC), World Health Organization (WHO), and your state and local government for the latest information.

It’s been many months since COVID-19 upended our lives. We’ve adjusted to wearing masks, social distancing, constantly our washing hands , and working and learning remotely . But what do we really know about how to prevent COVID-19 infection ?

Scientists, doctors, and public health officials are still trying to fully understand how the virus spreads, what to do to prevent it, and the best ways to treat it. New findings sometimes lead to advice that conflicts with what we’ve been told previously—and it can be a challenge to keep track of it all. Fortunately, there is plenty of solid advice we can still follow.

“It can be really exhausting to be constantly vigilant and to take precautions, like wearing a mask and physically distancing, which may be physically and emotionally uncomfortable,” says Jaimie Meyer, MD, MS , a Yale Medicine infectious disease expert. “But sustaining these types of behaviors is really key to curbing this pandemic, especially before a vaccine is available.”

Plus, cooler weather is bringing more of us indoors, which is riskier than being outside because there is less airflow and it can be more difficult to keep people 6 feet apart. What’s more, says Dr. Meyer, there’s the possibility that SARS-CoV-2 , the virus that causes COVID-19, is airborne, making ventilation even more important.

The upcoming months also bring seasonal respiratory viruses, like cold and flu , leading to concern about the possibility of a “twindemic” that may overwhelm health care systems already spread thin by COVID-19. These other illnesses can bring confusion because symptoms are very similar to those of COVID-19.

Meanwhile, COVID-19 remains with us, resulting in more than 210,000 deaths in the U.S. to date. As we leave a chaotic spring and summer behind and head into fall, now is a good time to check in with Yale Medicine experts and review the standard—and most recent—advice on how to stay safe.

1. Wear your mask

Wearing a mask that covers your mouth and nose can prevent those who have COVID-19 from spreading the virus to others. Recent evidence suggests that masks may even benefit the wearer, offering some level of protection against infections.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that everyone age 2 years and older wear masks in public settings and around people who don’t live in the same household—when you can’t stay 6 feet apart from others.

Masks should be made of two or more layers of washable, breathable fabric and fit snugly on your face. “A quick and easy test is to hold your mask up to the light. If light passes through, it’s too thin,” Dr. Meyer says. “Masks only work when they cover the nose and mouth because that is where infected droplets are expelled and because the virus infects people through the mucous membranes in their nose and throat.”

2. Stay socially distant

COVID-19 spreads mainly among people who are within 6 feet of one another (about two arms’ length) for a prolonged period (at least 15 minutes). Virus transmission can occur when an infected person coughs, sneezes, or talks, which releases droplets from the mouth or nose into the air.

People can be asymptomatic and spread the virus without knowing that they are sick, which makes it especially important to remain 6 feet away from others, whether you are inside or outside. Plus, the more people you interact with at a gathering and the longer time you spend interacting with each, the higher your risk of becoming infected with the virus by someone who has it.

If you are attending an event or gathering of some kind, it’s also important to be aware of the level of community transmission. One method of estimating how high the risk may be is referred to as R 0.

“Pronounced ‘R naught,’ and also known as the reproduction number, this is a measure of how fast a disease is spreading,” explains Onyema Ogbuagu, MBBCh , a Yale Medicine infectious disease expert. “If the reproduction number is 5.0, that means one infected person will spread the virus to an average of five people. Therefore, the lower the rate, the safer it is.”

The R 0 for COVID-19 is believed to be in the range of 1.4 to 2.9. For comparison, measles, which has the highest reproduction number known among humans, ranges from 12 to 18. Seasonal influenza is around 0.9 and 2.1.

While R 0 refers to the basic, or initial, reproduction number, there is another measurement called R t, which is the current reproduction number and is the average number of people who become infected by an infectious person. If R t is above 1.0, it spreads quickly. If it’s below 1.0, it will eventually stop spreading. You can check the number for each state here .

3. Keep washing your hands

Washing your hands—and well—remains a key step to preventing COVID-19 infection. Wash your hands with soap often, and especially after you have been in a public place or have blown your nose, coughed, or sneezed, the CDC recommends.

You should wash your hands for at least 20 seconds and lather the back of your hands and scrub between all fingers, under all fingernails, and reach up to the wrist, the CDC advises. After washing, dry them completely (with an air dryer or paper towel) and avoid touching the sink, faucet, door handles, or other objects. If no soap is available, use a hand sanitizer with at least 60% alcohol content, and rub the sanitizer on your hands until they are dry.

Though the CDC states that the primary way the virus spreads is through close person-to-person contact, it may be possible to become infected with COVID-19 by touching a surface or object that has the virus on it and then touching your own mouth, nose, or eyes.

Therefore, you should also wash your hands after touching anything that may have been contaminated—such as a banister or door handle in a public place—and before you touch your face.

While the virus can survive for a short period on some surfaces, it is unlikely to be spread from mail or from products or packaging, the CDC says. Likewise, the risk of infection from food (that you cook, is prepared in a restaurant, or is ordered via takeout) is considered to be very low, as is the risk from food packaging or bags.

Still, there is much that is unknown about the virus, and it remains advisable to wash hands thoroughly after handling any food or products that come into your home.

4. Keep holiday gatherings small

Fall and winter also bring holidays, when many families get together. This can be especially tricky for those of us who live in parts of the country where it will no longer be easy to gather outside. “After months apart during this pandemic, families may be less willing to do a group Zoom call,” says Dr. Meyer. “This may be a year where we need to get creative and rethink how to celebrate together.”

That may simply mean more planning for the holidays, Dr. Meyer says. “Consider quarantining for 14 days prior to the event and/or having everyone get tested for COVID-19 if tests are available in your community,” she suggests. “If possible, limit gatherings to as few people as possible—perhaps just immediate family and close friends. When it is not possible to be outside, encourage your guests to wear masks indoors. Consider spreading out food and eating areas so people are distanced while eating with their masks down.”

Remember that your elderly family members and those with other medical conditions are most vulnerable to COVID-19, so take extra measures to protect them, says Dr. Meyer.

5. Dine out carefully

Although many restaurants offer outdoor dining, which experts say is the safer option, a recent CDC study showed that adults with COVID-19 infections were twice as likely to have visited a restaurant in the two weeks preceding their illness than those without an infection.

The study did not distinguish between indoor or outdoor dining, or consider adherence to social distancing and mask use. (Those with COVID-19 infections were more likely to report having dined out at places where few other people were wearing masks or socially distancing.)

“If you are meeting with others at a restaurant and sharing tables while eating, which does not allow for appropriate social distancing and mask use, it provides opportunities for the virus to spread from person to person,” Dr. Ogbuagu notes. “The probability of spreading infection is higher with each additional person you are in contact with, especially when people congregate.”

6. Travel safely

While you should avoid traveling if you can—as the CDC says staying home is the best way to avoid COVID-19—sometimes, it is necessary. But before you leave, you can check to see if the virus is spreading at your destination. More cases at your destination increases your risk of contracting the virus and spreading it to others. You can view each state’s weekly number of cases here on the CDC web site.

“Also, don’t forget to check the regulations for quarantining or testing at your destination or for when you return home,” says Dr. Meyer. Whether you are traveling by car, plane, bus, or train, there are precautions you can take along the way. The CDC has a detailed list of recommendations for each mode of transportation that mostly follows the advice listed above of practicing social distancing, wearing a mask, and washing hands, but also includes specific advice for various scenarios.

7. Get your flu shot

Health officials are concerned about an influx of flu and COVID-19 cases overwhelming hospitals. In the 2018-2019 flu season, 490,600 Americans were hospitalized for the flu, according to the CDC.

Public health experts say this is not the year to skip the flu vaccine. While measures to prevent COVID-19, including mask-wearing, washing hands, and social distancing, can also protect against the flu, the vaccine is especially important—and safe, doctors say.

Though many people claim that the flu shot “gave them the flu,” it is not possible to get infected with the influenza virus from the vaccine itself, Dr. Meyer says. “The vaccine is made up of inactivated virus and is designed to ‘tickle’ the immune system to respond to the real thing when it sees it,” she explains. “The most common side effect from the flu shot is soreness or redness at the site of the injection, which resolves within a day or two.”

The flu vaccine is recommended for everyone 6 months old and up. Talk to your doctor about finding a vaccine near you.

8. Differentiate between flu, colds, and COVID-19

Many people will likely struggle to differentiate between the flu, the common cold, and COVID-19, all of which have similar symptoms.

For example, both COVID-19 and the flu can cause fever, shortness of breath, fatigue, headache, cough, sore throat, runny nose, muscle pain, or body aches, as well as vomiting and diarrhea (though these last two are more common in children). Meanwhile, colds may be milder than the flu and are more likely to involve a runny or stuffy nose. One difference, however, is that COVID-19 is associated with a loss of taste and smell .

So, if you or someone in your family comes down with any of these symptoms, what should you do?

“First, you should stay away from others as much as possible and perform hand washing before you make contact with your face,” Dr. Ogbuagu says. “And certainly go see a doctor or to the hospital if you have serious symptoms, such as a high fever or shortness of breath. Otherwise, getting a COVID-19 test at a testing facility near you would help to define what type of respiratory illness you have and also how to advise people you had been in contact with.”

Parents, Dr. Meyer adds, will need to contact their children’s pediatricians about these symptoms because otherwise their children likely won’t be able to return to school.

“I would also add that people who are older and have underlying medical conditions should have a low threshold to seek care for any of these symptoms,” she says. “Earlier is better, especially for influenza, as we have antiviral medications that work if given within 72 hours of the onset of symptoms.”

9. Seek routine medical care

You should continue to seek any routine or emergency medical care or treatments you need. Many health centers and doctors are offering telehealth appointments (via video or phone) and most have protocols to minimize risk of exposure to the coronavirus.

Getting emergency care when you need it is especially important. Earlier in the pandemic, pediatric and adult physicians reported fewer emergency department visits, leading to a concern that patients were avoiding seeking care due to fears of contracting COVID-19.

“As important as it is to continue to engage in care for known medical issues, there is also a concern that people are falling behind on their preventive healthcare, like getting routine procedures including colonoscopies and pap smears, as well as vaccines,” Dr. Meyer says. “Those other health issues don’t go away just because there is a pandemic. Reach out to your primary care doctor if you’re unsure what you are due to receive.”

10. Be mindful of your mental health

Many people are experiencing anxiety, depression, and other mental health issues during the pandemic as it is a time of stress and uncertainty. All of this is normal, say mental health experts, who recommend that you allow yourself to embrace all emotions, including those that are unpleasant, in order to better manage them.

Experts advise limiting exposure to news if the events of the world are too much right now, practicing mindfulness (even just breathing exercises), eating healthy, and remaining physically active.

For kids, who are still adjusting to a lack of play dates, canceled activities, and different school schedules, parents can help by fully listening to their concerns and providing age-appropriate answers to their questions. By talking with kids about what they know and how they are doing, parents may be able to determine if further emotional support is needed.

11. Watch your weight

At a time when routines are disrupted and many people are working at home—where snacks are readily available—some may be gaining weight (the so-called quarantine 15). Now more than ever, Yale Medicine doctors recommend that you focus on eating a healthy diet, incorporating regular exercise, getting good sleep, and finding healthy ways to manage stress.

Meanwhile, obesity is emerging as an independent risk factor for severe COVID-19 illness—even among younger patients. One study, which examined hospitalized COVID-19 patients under age 60, found that those with obesity were twice as likely to require hospitalization and even more likely to need critical care than those who did not have it. Given that an estimated 42% of Americans have obesity (having a body mass index equal to or more than 30), this is important.

12. Keep up the good (safety) work

It is likely that COVID-19 will be with us for a while. “But with good efforts to continue to follow the public health measures to protect each other, and, hopefully, a successful vaccine in the future, there is a light at the end of the tunnel,” Dr. Ogbuagu says.

But even before a safe and effective vaccine is available, COVID-19 is a preventable disease, Dr. Meyer points out. “It just requires all of us to do the hard work of practicing the behaviors—described above—to keep our communities safe and healthy.”

Note: Information provided in Yale Medicine articles is for general informational purposes only. No content in the articles should ever be used as a substitute for medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician. Always seek the individual advice of your health care provider with any questions you have regarding a medical condition.

More news from Yale Medicine

Students’ Essays on Infectious Disease Prevention, COVID-19 Published Nationwide

As part of the BIO 173: Global Change and Infectious Disease course, Professor Fred Cohan assigns students to write an essay persuading others to prevent future and mitigate present infectious diseases. If students submit their essay to a news outlet—and it’s published—Cohan awards them with extra credit.

As a result of this assignment, more than 25 students have had their work published in newspapers across the United States. Many of these essays cite and applaud the University’s Keep Wes Safe campaign and its COVID-19 testing protocols.

Cohan, professor of biology and Huffington Foundation Professor in the College of the Environment (COE), began teaching the Global Change and Infectious Disease course in 2009, when the COE was established. “I wanted very much to contribute a course to what I saw as a real game-changer in Wesleyan’s interest in the environment. The course is about all the ways that human demands on the environment have brought us infectious diseases, over past millennia and in the present, and why our environmental disturbances will continue to bring us infections into the future.”

Over the years, Cohan learned that he can sustainably teach about 170 students every year without running out of interested students. This fall, he had 207. Although he didn’t change the overall structure of his course to accommodate COVID-19 topics, he did add material on the current pandemic to various sections of the course.

“I wouldn’t say that the population of the class increased tremendously as a result of COVID-19, but I think the enthusiasm of the students for the material has increased substantially,” he said.

To accommodate online learning, Cohan shaved off 15 minutes from his normal 80-minute lectures to allow for discussion sections, led by Cohan and teaching assistants. “While the lectures mostly dealt with biology, the discussions focused on how changes in behavior and policy can solve the infectious disease problems brought by human disturbance of the environment,” he said.

Based on student responses to an introspective exam question, Cohan learned that many students enjoyed a new hope that we could each contribute to fighting infectious disease. “They discovered that the solution to infectious disease is not entirely a waiting game for the right technologies to come along,” he said. “Many enjoyed learning about fighting infectious disease from a moral and social perspective. And especially, the students enjoyed learning about the ‘socialism of the microbe,’ how preventing and curing others’ infections will prevent others’ infections from becoming our own. The students enjoyed seeing how this idea can drive both domestic and international health policies.”

A sampling of the published student essays are below:

Alexander Giummo ’22 and Mike Dunderdale’s ’23 op-ed titled “ A National Testing Proposal: Let’s Fight Back Against COVID-19 ” was published in the Journal Inquirer in Manchester, Conn.

They wrote: “With an expansive and increased testing plan for U.S. citizens, those who are COVID-positive could limit the number of contacts they have, and this would also help to enable more effective contact tracing. Testing could also allow for the return of some ‘normal’ events, such as small social gatherings, sports, and in-person class and work schedules.

“We propose a national testing strategy in line with the one that has kept Wesleyan students safe this year. The plan would require a strong push by the federal government to fund the initiative, but it is vital to successful containment of the virus.

“Twice a week, all people living in the U.S. should report to a local testing site staffed with professionals where the anterior nasal swab Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) test, used by Wesleyan and supported by the Broad Institute, would be implemented.”

Kalyani Mohan ’22 and Kalli Jackson ’22 penned an essay titled “ Where Public Health Meets Politics: COVID-19 in the United States ,” which was published in Wesleyan’s Arcadia Political Review .

They wrote: “While the U.S. would certainly benefit from a strengthened pandemic response team and structural changes to public health systems, that alone isn’t enough, as American society is immensely stratified, socially and culturally. The politicization of the COVID-19 pandemic shows that individualism, libertarianism and capitalism are deeply ingrained in American culture, to the extent that Americans often blind to the fact community welfare can be equivalent to personal welfare. Pandemics are multifaceted, and preventing them requires not just a cultural shift but an emotional one amongst the American people, one guided by empathy—towards other people, different communities and the planet. Politics should be a tool, not a weapon against its people.”

Sydnee Goyer ’21 and Marcel Thompson’s ’22 essay “ This Flu Season Will Be Decisive in the Fight Against COVID-19 ” also was published in Arcadia Political Review .

“With winter approaching all around the Northern Hemisphere, people are preparing for what has already been named a “twindemic,” meaning the joint threat of the coronavirus and the seasonal flu,” they wrote. “While it is known that seasonal vaccinations reduce the risk of getting the flu by up to 60% and also reduce the severity of the illness after the contamination, additional research has been conducted in order to know whether or not flu shots could reduce the risk of people getting COVID-19. In addition to the flu shot, it is essential that people remain vigilant in maintaining proper social distancing, washing your hands thoroughly, and continuing to wear masks in public spaces.”

An op-ed titled “ The Pandemic Has Shown Us How Workplace Culture Needs to Change ,” written by Adam Hickey ’22 and George Fuss ’21, was published in Park City, Utah’s The Park Record .

They wrote: “One review of academic surveys (most of which were conducted in the United States) conducted in 2019 found that between 35% and 97% of respondents in those surveys reported having attended work while they were ill, often because of workplace culture or policy which generated pressure to do so. Choosing to ignore sickness and return to the workplace while one is ill puts colleagues at risk, regardless of the perceived severity of your own illness; COVID-19 is an overbearing reminder that a disease that may cause mild, even cold-like symptoms for some can still carry fatal consequences for others.

“A mandatory paid sick leave policy for every worker, ideally across the globe, would allow essential workers to return to work when necessary while still providing enough wiggle room for economically impoverished employees to take time off without going broke if they believe they’ve contracted an illness so as not to infect the rest of their workplace and the public at large.”

Women’s cross country team members and classmates Jane Hollander ’23 and Sara Greene ’23 wrote a sports-themed essay titled “ This Season, High School Winter Sports Aren’t Worth the Risk ,” which was published in Tap into Scotch Plains/Fanwood , based in Scotch Plains, N.J. Their essay focused on the risks high school sports pose on student-athletes, their families, and the greater community.

“We don’t propose cutting off sports entirely— rather, we need to be realistic about the levels at which athletes should be participating. There are ways to make practices safer,” they wrote. “At [Wesleyan], we began the season in ‘cohorts,’ so the amount of people exposed to one another would be smaller. For non-contact sports, social distancing can be easily implemented, and for others, teams can focus on drills, strength and conditioning workouts, and skill-building exercises. Racing sports such as swim and track can compete virtually, comparing times with other schools, and team sports can focus their competition on intra-team scrimmages. These changes can allow for the continuation of a sense of normalcy and team camaraderie without the exposure to students from different geographic areas in confined, indoor spaces.”

Brook Guiffre ’23 and Maddie Clarke’s ’22 op-ed titled “ On the Pandemic ” was published in Hometown Weekly, based in Medfield, Mass.

“The first case of COVID-19 in the United States was recorded on January 20th, 2020. For the next month and a half, the U.S. continued operating normally, while many other countries began their lockdown,” they wrote. “One month later, on February 29th, 2020, the federal government approved a national testing program, but it was too little too late. The U.S. was already in pandemic mode, and completely unprepared. Frontline workers lacked access to N-95 masks, infected patients struggled to get tested, and national leaders informed the public that COVID-19 was nothing more than the common flu. Ultimately, this unpreparedness led to thousands of avoidable deaths and long-term changes to daily life. With the risk of novel infectious diseases emerging in the future being high, it is imperative that the U.S. learn from its failure and better prepare for future pandemics now. By strengthening our public health response and re-establishing government organizations specialized in disease control, we have the ability to prevent more years spent masked and six feet apart.”

In addition, their other essay, “ On Mass Extinction ,” was also published by Hometown Weekly .

“The sixth mass extinction—which scientists have coined as the Holocene Extinction—is upon us. According to the United Nations, around one million plant and animal species are currently in danger of extinction, and many more within the next decade. While other extinctions have occurred in Earth’s history, none have occurred at such a rapid rate,” they wrote. “For the sake of both biodiversity and infectious diseases, it is in our best interest to stop pushing this Holocene Extinction further.”

An essay titled “ Learning from Our Mistakes: How to Protect Ourselves and Our Communities from Diseases ,” written by Nicole Veru ’21 and Zoe Darmon ’21, was published in My Hometown Bronxville, based in Bronxville, N.Y.

“We can protect ourselves and others from future infectious diseases by ensuring that we are vaccinated,” they wrote. “Vaccines have high levels of success if enough people get them. Due to vaccines, society is no longer ravaged by childhood diseases such as mumps, rubella, measles, and smallpox. We have been able to eradicate diseases through vaccines; smallpox, one of the world’s most consequential diseases, was eradicated from the world in the 1970s.

“In 2000, the U.S. was nearly free of measles, yet, due to hesitations by anti-vaxxers, there continues to be cases. From 2000–2015 there were over 18 measles outbreaks in the U.S. This is because unless a disease is completely eradicated, there will be a new generation susceptible.

“Although vaccines are not 100% effective at preventing infection, if we continue to get vaccinated, we protect ourselves and those around us. If enough people are vaccinated, societies can develop herd immunity. The amount of people vaccinated to obtain herd immunity depends on the disease, but if this fraction is obtained, the spread of disease is contained. Through herd immunity, we protect those who may not be able to get vaccinated, such as people who are immunocompromised and the tiny portion of people for whom the vaccine is not effective.”

Dhruvi Rana ’22 and Bryce Gillis ’22 co-authored an op-ed titled “ We Must Educate Those Who Remain Skeptical of the Dangers of COVID-19 ,” which was published in Rhode Island Central .

“As Rhode Island enters the winter season, temperatures are beginning to drop and many studies have demonstrated that colder weather and lower humidity are correlated with higher transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19,” they wrote. “By simply talking or breathing, we release respiratory droplets and aerosols (tiny fluid particles which could carry the coronavirus pathogen), which can remain in the air for minutes to hours.

“In order to establish herd immunity in the US, we must educate those who remain skeptical of the dangers of COVID-19. Whether community-driven or state-funded, educational campaigns are needed to ensure that everyone fully comprehends how severe COVID-19 is and the significance of airborne transmission. While we await a vaccine, it is necessary now more than ever that we social distance, avoid crowds, and wear masks, given that colder temperatures will likely yield increased transmission of the virus.”

Danielle Rinaldi ’21 and Verónica Matos Socorro ’21 published their op-ed titled “ Community Forum: How Mask-Wearing Demands a Cultural Reset ” in the Ewing Observer , based in Lawrence, N.J.

“In their own attempt to change personal behavior during the pandemic, Wesleyan University has mandated mask-wearing in almost every facet of campus life,” they wrote. “As members of our community, we must recognize that mask-wearing is something we are all responsible and accountable for, not only because it is a form of protection for us, but just as important for others as well. However, it seems as though both Covid fatigue and complacency are dominating the mindsets of Americans, leading to even more unwillingness to mask up. Ultimately, it is inevitable that this pandemic will not be the last in our lifespan due to global warming creating irreversible losses in biodiversity. As a result, it is imperative that we adopt the norm of mask-wearing now and undergo a culture shift of the abandonment of an individualistic mindset, and instead, create a society that prioritizes taking care of others for the benefit of all.”

Shayna Dollinger ’22 and Hayley Lipson ’21 wrote an essay titled “ My Pandemic Year in College Has Brought Pride and Purpose. ” Dollinger submitted the piece, rewritten in first person, to Jewish News of Northern California . Read more about Dollinger’s publication in this News @ Wesleyan article .

“I lay in the dead grass, a 6-by-6-foot square all to myself. I cheer for my best friend, who is on the stage constructed at the bottom of Foss hill, dancing with her Bollywood dance group. Masks cover their ordinarily smiling faces as their bodies move in sync. Looking around at friends and classmates, each in their own 6-by-6 world, I feel an overwhelming sense of normalcy.

“One of the ways in which Wesleyan has prevented outbreaks on campus is by holding safe, socially distanced events that students want to attend. By giving us places to be and things to do on the weekends, we are discouraged from breaking rules and causing outbreaks at ‘super-spreader’ events.”

An op-ed written by Luna Mac-Williams ’22 and Daëlle Coriolan ’24 titled “ Collectivist Practices to Combat COVID-19 ” was published in the Wesleyan Argus .

“We are embroiled in a global pandemic that disproportionately affects poor communities of color, and in the midst of a higher cultural consciousness of systemic inequities,” they wrote. “A cultural shift to center collectivist thought and action not only would prove helpful in disease prevention, but also belongs in conversation with the Black Lives Matter movement. Collectivist models of thinking effectively target the needs of vulnerable populations including the sick, the disenfranchised, the systematically marginalized. Collectivist systems provide care, decentering the capitalist, individualist system, and focusing on how communities can work to be self-sufficient and uplift our own neighbors.”

An essay written by Maria Noto ’21 , titled “ U.S. Individualism Has Deadly Consequences ,” is published in the Oneonta Daily Star , based in Oneonta, N.Y.

She wrote, “When analyzing the cultures of certain East Asian countries, several differences stand out. For instance, when people are sick and during the cold and flu season, many East Asian cultures, including South Korea, use mask-wearing. What is considered a threat to freedom by some Americans is a preventive action and community obligation in this example. This, along with many other cultural differences, is insightful in understanding their ability to contain the virus.

“These differences are deeply seeded in the values of a culture. However, there is hope for the U.S. and other individualistic cultures in recognizing and adopting these community-centered approaches. Our mindset needs to be revolutionized with the help of federal and local assistance: mandating masks, passing another stimulus package, contact tracing, etc… However, these measures will be unsuccessful unless everyone participates for the good of a community.”

A published op-ed by Madison Szabo ’23 , Caitlyn Ferrante ’23 ran in the Two Rivers Times . The piece is titled “ Anxiety and Aspiration: Analyzing the Politicization of the Pandemic .”

John Lee ’21 and Taylor Goodman-Leong ’21 have published their op-ed titled “ Reassessing the media’s approach to COVID-19 ” in Weekly Monday Cafe 24 (Page 2).

An essay by Eleanor Raab ’21 and Elizabeth Nefferdorf ’22 titled “ Preventing the Next Epidemic ” was published in The Almanac .

- Keep Wes Safe

- student publications

- Teaching during the pandemic

Related Articles

Student’s Agricultural Project in Rwanda Wins Davis Projects for Peace Grant

Gallery: wesleyan, local communities flock to foss hill for eclipse.

Students Research Works in Davison Art Collection for New Print Exhibition

Previous matesan's new book explores political violence, islamist mobilization in egypt and indonesia, next students launch fun, interactive virtual program for school-aged kids.

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 29 April 2021

Effectiveness of personal protective health behaviour against COVID-19

- Chon Fu Lio 1 ,

- Hou Hon Cheong 1 ,

- Chin Ion Lei 2 , 3 ,

- Iek Long Lo 4 ,

- Lan Yao 4 ,

- Chong Lam 5 &

- Iek Hou Leong 5

BMC Public Health volume 21 , Article number: 827 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

10k Accesses

34 Citations

153 Altmetric

Metrics details

Novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has become a pandemic, and over 80 million cases and over 1.8 million deaths were reported in 2020. This highly contagious virus is spread primarily via respiratory droplets from face-to-face contact and contaminated surfaces as well as potential aerosol spread. Over half of transmissions occur from presymptomatic and asymptomatic carriers. Although several vaccines are currently available for emergency use, there are uncertainties regarding the duration of protection and the efficacy of preventing asymptomatic spread. Thus, personal protective health behaviour and measures against COVID-19 are still widely recommended after immunization. This study aimed to clarify the efficacy of these measures, and the results may provide valuable guidance to policymakers to educate the general public about how to reduce the individual-level risk of COVID-19 infection.

This case-control study enrolled 24 laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 patients from Centro Hospitalar Conde de São Januário (C.H.C.S.J.), which was the only hospital designated to manage COVID-19 patients in Macao SAR, China, and 1113 control participants who completed a 14-day mandatory quarantine in 12 designated hotels due to returning from high-risk countries between 17 March and 15 April 2020. A questionnaire was developed to extract demographic information, contact history, and personal health behaviour.

Participants primarily came from the United Kingdom (33.2%), followed by the United States (10.5%) and Portugal (10.2%). Independent factors for COVID-19 infection were having physical contact with confirmed/suspected COVID-19 patients (adjusted OR, 12.108 [95% CI, 3.380–43.376], P < 0.005), participating in high-risk gathering activities (adjusted OR, 1.129 [95% CI, 1.048–1.216], P < 0.005), handwashing after outdoor activity (adjusted OR, 0.021 [95% CI, 0.003–0.134], P < 0.005), handwashing before touching the mouth and nose area (adjusted OR, 0.303 [95% CI, 0.114–0.808], P < 0.05), and wearing a mask whenever outdoors (adjusted OR, 0.307 [95% CI, 0.109–0.867], P < 0.05). The daily count of handwashing remained similar between groups. Only 31.6% of participants had a sufficient 20-s handwashing duration.

Conclusions

Participating in high-risk gatherings, wearing a mask whenever outdoors, and practising hand hygiene at key times should be advocated to the public to mitigate COVID-19 infection.

Peer Review reports

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) evolved from a global public health emergency to a pandemic after the declaration by the World Health Organization (WHO) on March 11, 2020 [ 1 ]. The outbreak caused public fear and serious burdens on healthcare systems, social relationships and economies worldwide. As of January 3, 2021, over 80 million cases had been confirmed, with more than 1.8 million deaths globally [ 2 ]. Nevertheless, the high transmissibility from pre- or asymptomatic patients concurred with virus RNA levels peaking at day 4 from symptom onset, possibly exacerbating the spread [ 3 ]. This highly contagious virus is spread primarily via respiratory droplets from face-to-face contact and contaminated surfaces as well as potential aerosol spread [ 4 ]. It is estimated that over half of transmissions occur from presymptomatic and asymptomatic carriers [ 5 ]. Although vaccines for COVID-19 have become available recently, there are uncertainties regarding the duration of protection and the efficacy of preventing asymptomatic spread [ 6 ].

Initially, various public health policies were adopted among different countries to attempt to mitigate the outbreak, and the preliminary outcomes of these measures including “lockdown” or sanitary cordon, travel restrictions, quarantines for travellers, stay-at-home orders, closure of schools and business, and bans on gatherings were encouraging [ 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 ]. It is recognized that some leading causes of morbidity and mortality could be attributed to health determinants associated with the health behaviour of individuals, such as the adoption of health behaviour against virus transmission (e.g., hand washing and use of masks outdoors) and the avoidance of health-harming behaviours (e.g., touching the face and gathering for occasions) [ 12 ]. Though personal hygiene practices such as washing hands, wearing masks, and maintaining social distance are widely recommended to the public based on the knowledge of droplet transmission, there is still scarce evidence of the effectiveness of these personal measures in preventing COVID-19 infection at the individual level.

Therefore, a case-control study was conducted to determine the risk and protective factors for COVID-19 infection at the individual level, with a specific emphasis on personal behaviours such as mask use, the number of gatherings, and hand hygiene practices. A questionnaire was designed to extract related information among COVID-19 patients in Centro Hospitalar Conde de São Januário (C.H.C.S.J.), the only hospital designated to manage COVID-19 patients in Macao SAR. People who had been in a COVID-19 high-risk foreign country undergoing a 14-day mandatory quarantine in 12 designated hotels in Macao SAR served as the control group. This article is structurally divided into the introduction, methods describing the study design and statistical analysis, the results of effect sizes of different measures against COVID-19 infection, discussion and conclusions.

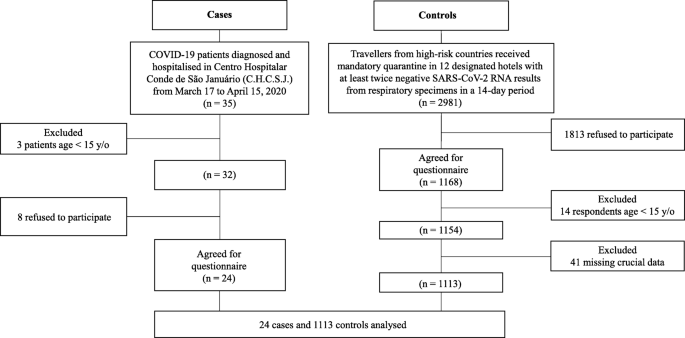

Study design and population

A cross-sectional questionnaire survey was conducted in Macao from March 17, 2020, to April 15, 2020 (the flowchart of participant recruitment in the case-control study is shown in Fig. 1 ). The study population consisted of the following: 1) people who had been in a COVID-19 high-risk foreign country in the past 14 days before entry to Macao and would have completed a 14-day mandatory quarantine in 12 designated hotels in Macao before the end of the study period and 2) people diagnosed with COVID-19 and hospitalized in C.H.C.S.J., the only hospital designated to manage COVID-19 cases. All participants who could understand and complete the questionnaire written in Chinese, English or Portuguese were included.

Flowchart of participant recruitment in the case-control study

Instrument and data collection

For the case group, 35 patients were included, 3 patients under the age of 15 were excluded, and 6 patients refused to participate. For the control group, 2981 travellers were initially included, 1813 of whom refused to participate, while 14 respondents under the age of 15 and 41 questionnaires without crucial data were subsequently excluded. The exclusion criteria included age less than 15 years, refusal to participate and questionnaires with missing crucial data. Questions covered the following topics: personal data and information, personal health status and living habits, epidemic prevention and control situation of the main country in which one stayed, contact history, personal protective health behaviour and measures before returning to Macao. The detailed content can be found in the questionnaire template in the Additional file 1 .

Informed consent

The Macao Health Bureau, Centro Hospitalar Conde de São Januário, Medical Ethical Committee approved the research protocol. All procedures performed in the study involving human participants were consistent with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. All participants gave informed consent via web-based systems before answering questionnaires. Using a paper questionnaire, written informed consent was acquired and collected.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics for demographic information, preventive policy, contact history, and personal protective health behaviour and measures were calculated. Then, patients were divided into “COVID-19 infected” and “non-infected” groups. Differences in percentages between groups were examined using Pearson’s chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U test was utilized to examine the differences among continuous variables depending on the data normality. Univariate logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with COVID-19 infection. Then, those significant factors were pooled and selected to build a multivariate logistic model via a forward-selection stepwise method. The level of statistical significance was set at α = 0.05. R (version 3.5.2, R Development Core Team 2018) was used to conduct statistical analyses.

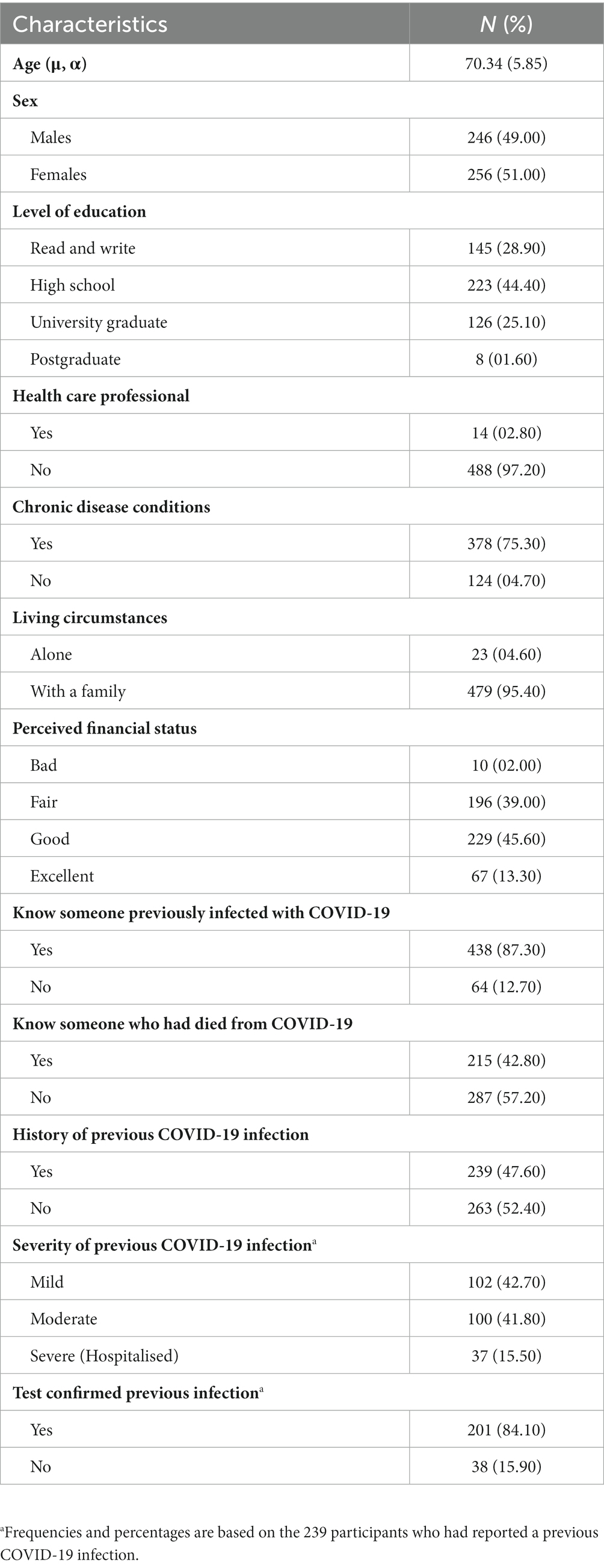

Overall, 1137 questionnaires were considered effective and were analysed accordingly. The total response rate was 37.7% (1137/3013), and the response rate of the infected group was 75% (24/32). Demographic information and the comparison between infected and non-infected groups are summarized in Table 1 . The majority of the participants were aged between 20 and 44 years (65.5%) and had received secondary education or above (55.5%). Overall, 93% of participants denied having any chronic diseases. The most common comorbid diseases were hypertension (3.3%), followed by diabetes mellitus (1.1%) and dyslipidaemia (0.9%). The majority of respondents were non-smokers (80.7%). The top 10 countries in which the participants stayed before returning to Macao were the United Kingdom (33.2%), United States (10.5%), Portugal (10.2%), Australia (9.1%), Canada (4.7%), Philippines (3.5%), China (3.3%), Malaysia (2.4%), Cambodia (2.2%), and Thailand (2%). The main reasons for staying abroad were “study abroad” (60.9%), “visiting relatives” (12.9%), “travel” (11.6%), and “business trip” (6.0%).

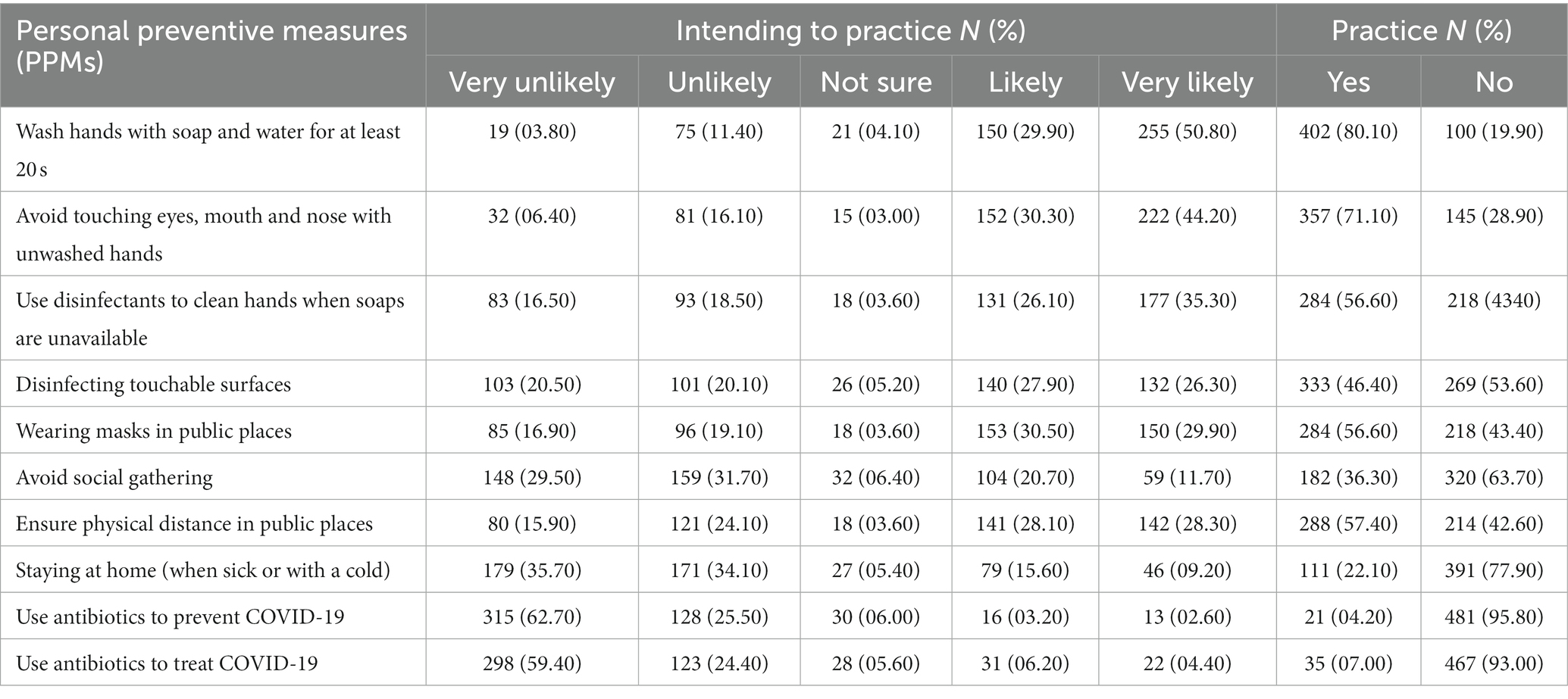

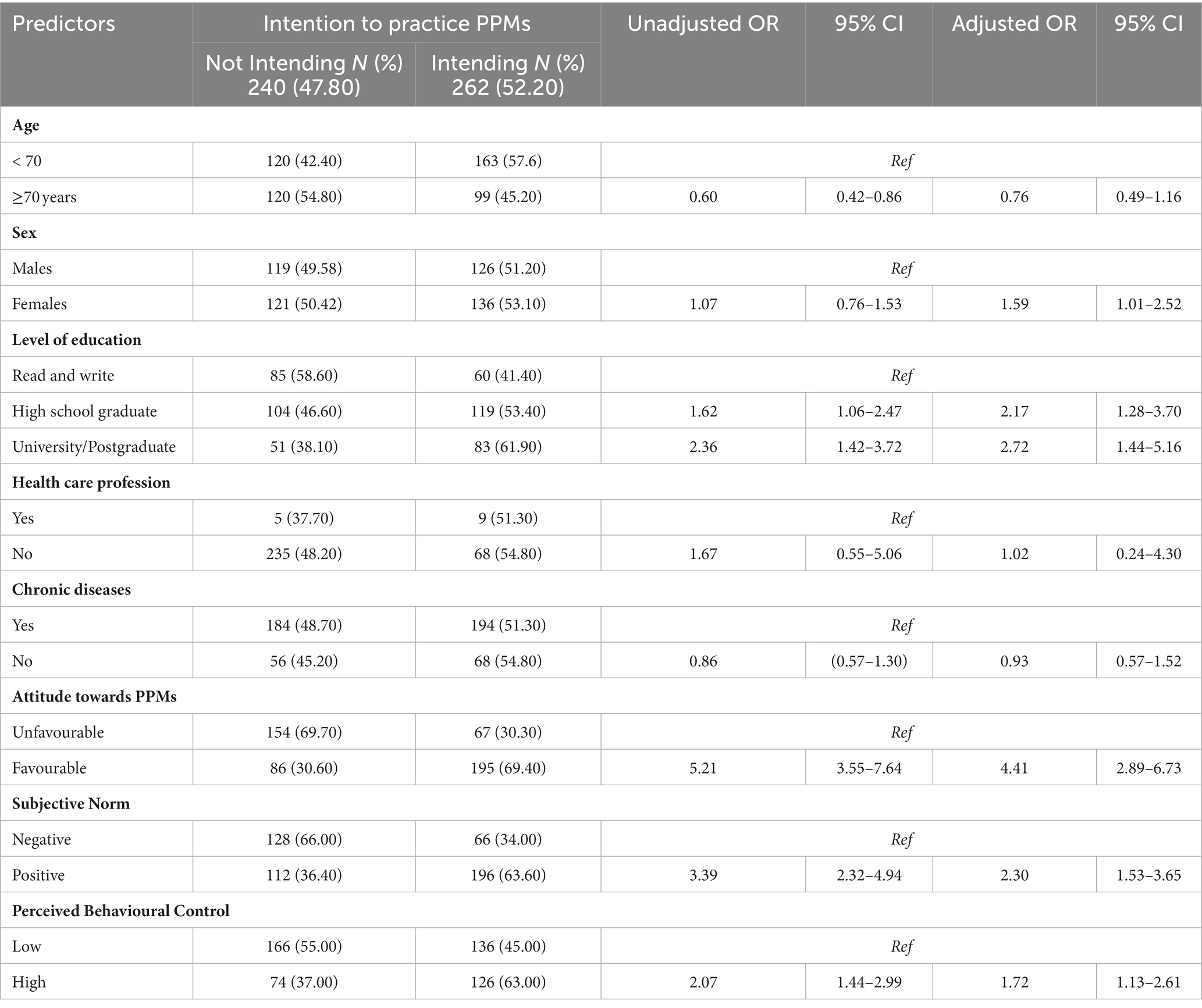

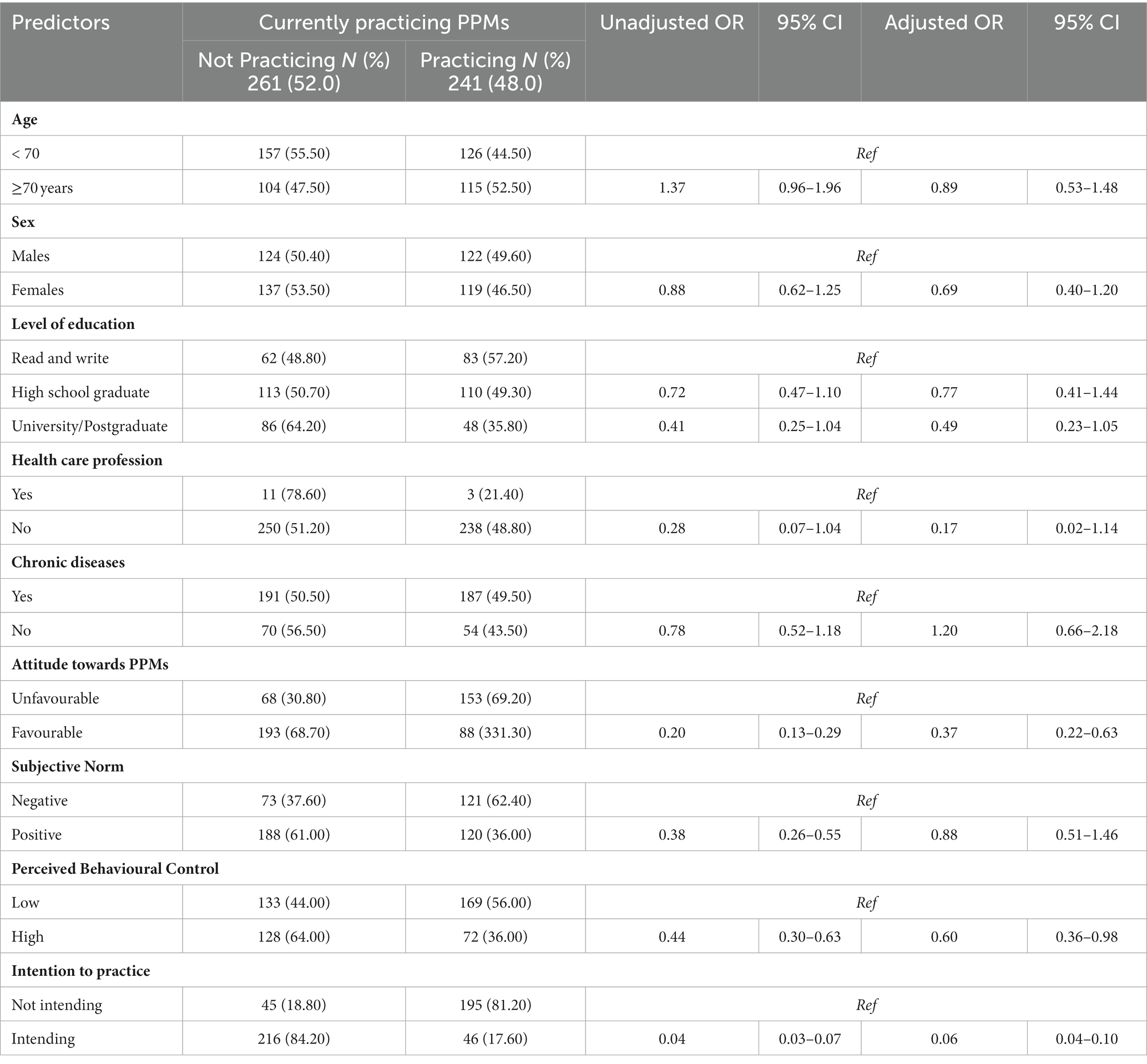

Personal protective health behaviour and measures for COVID-19 in the local community in which the participants stayed before returning to Macao

Within 14 days before returning to Macao, the majority of respondents (79.3%) stated that COVID-19 was spreading in the countries in which they stayed (Table 2 ). In total, 42.9% of participants were requested to undergo self-quarantine at home. There were seemingly lower proportions of traffic restrictions (20.8% vs 33.2%; P = 0.201) and closures of public entertainment venues (37.5% vs 49.2%; P = 0.255) in the COVID-19-infected group than in the non-infected group in the countries in which they stayed; however, the statistical power was insufficient to differentiate the extent of these differences due to the limited sample size in the COVID-19 patient group.

Contact history and frequency of outdoor activities

In total, only a minority of participants had visited medical facilities for any reason (4.9%) and had contact with those who had respiratory symptoms (8%) or confirmed/suspected COVID-19 patients (2.2%) (Table 3 ). Notably, there were significantly higher percentages of these activities in the infected group than in the non-infected group, such as having physical contact with those who had respiratory symptoms (25% vs 7.6%; P = 0.002) or confirmed/suspected COVID-19 patients (16.7% vs 1.9%; P = 0.001). Moreover, compared to the non-infected populations, the infected group presented fewer protective measures during/after contact with high-risk people, such as washing hands (50% vs 95.3%; P = 0.005) and wearing a mask (16.7% vs 67.1%; P = 0.022) following contact with someone who was symptomatic. Participants were asked to calculate the total number of outdoor activities within a 14-day interval before returning to Macao. Notably, there were significantly more high-risk gathering activities defined by interacting with people within 2 m without wearing a mask (5.4 ± 10.1 vs 0.7 ± 2.3; P = 0.034) in the infected group than in the non-infected group within 14 days before returning to Macao.

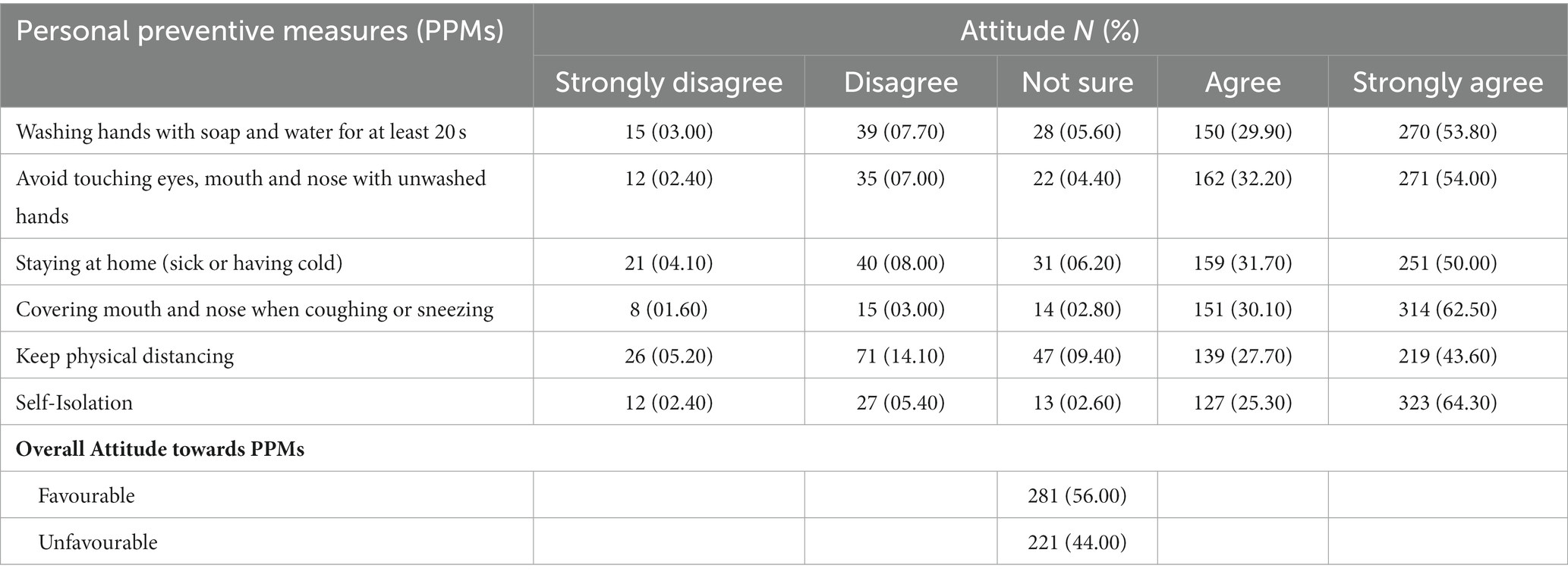

Mask usage behaviour, timing and duration for handwashing

More than half (63.5%) of the participants admitted that they wore a mask whenever they stayed outdoors within 14 days before returning to Macao. There was a larger proportion of non-infected participants wearing a mask whenever outdoors than the infected group (63.5% vs 25.0%; P < 0.001) (Table 4 ). The majority of participants believed that there was a lower chance of accidentally touching the mouth and nose area after wearing a mask (79.8%), and almost all of them acknowledged that hand hygiene was still important after mask usage (95.1%).

With regard to hand hygiene, the practice of handwashing was substantially less common in the infected population than in the non-infected population, such as handwashing after handling food or cooking (75% vs 94.2%; P < 0.001), after a toilet trip (79.2% vs 91.5%; P = 0.035), after outdoor activity (83.3% vs 99.5%, P < 0.001), after sneezing or coughing (54.2% vs 80.5%; P = 0.001), after handling pets (58.3% vs 81.2%; P = 0.005), and before touching the mouth and nose area (50.0% vs 86.5%; P < 0.001). However, only approximately one-third of the total population (31.6%) achieved a sufficient 20-s duration for handwashing. Furthermore, only 16.7% of the infected population washed hands for over 20 s each time, compared with 31.9% in the noninfected group ( P = 0.125), and the mean duration of handwashing each time was less than 20 s in the infected group (18.8 ± 11.2 s). On the other hand, the average number of handwashes with soap or alcoholic sanitizers per day remained similar between the two groups (9.1 ± 8.4 vs 9.2 ± 8.4, P = 0.958).

Risk and protective factors associated with COVID-19 infection

In univariate analysis (Table 5 ), those who had physical contact with people having respiratory symptoms (crude OR, 10.4 [95% CI, 3.270–33.079], P < 0.005) or confirmed/suspected COVID-19 patients (crude OR, 12.381 [95% CI, 4.261–35.973], P < 0.005) had a higher risk of COVID-19 infection than those who did not. A risk reduction of 80.9% was noted in those who wore masks whenever outdoors (crude OR, 0.191 [95% CI, 0.075–0.486], P < 0.005) compared with those who did not. Outdoor activities, such as “high-risk gathering”, defined as interacting with people within 2 m without wearing masks, significantly increased the COVID-19 risk by up to 15.5% each time (crude OR, 1.155 [95% CI, 1.089–1.225], P < 0.005). Decent handwashing habits showed protective effects on COVID-19 infection, such as after handling food or cooking (crude OR, 0.186 [95% CI, 0.071–0.485], P < 0.005), after a toilet trip (crude OR, 0.355 [95% CI, 0.130–0.971], P < 0.05), after outdoor activity (crude OR, 0.027 [95% CI, 0.007–0.104], P < 0.005), after sneezing or coughing (crude OR, 0.286 [95% CI, 0.127–0.648], P < 0.005), after handling pets (crude OR, 0.324 [95% CI, 0.142–0.739], P < 0.01), and before touching the mouth and nose area (crude OR, 0.156 [95% CI, 0.069–0.353], P < 0.005). In multivariate logistic regression via a forward-selection stepwise method, independent factors for COVID-19 infection were having physical contact with confirmed/suspected COVID-19 patients (adjusted OR, 12.108 [95% CI, 3.380–43.376], P < 0.005), wearing a mask whenever outdoors (adjusted OR, 0.307 [95% CI, 0.109–0.867], P < 0.05), the number of high-risk gathering activities (interact with people within 2 m without wearing a mask) in a 14-day interval (adjusted OR, 1.129 [95% CI, 1.048–1.216], P < 0.005), handwashing after outdoor activity (adjusted OR, 0.021 [95% CI, 0.003–0.134], P < 0.005), and before touching the mouth and nose area (adjusted OR, 0.303 [95% CI, 0.114–0.808], P < 0.05).

Ultimately, our findings showed that the most commonly advised measures were effective against COVID-19 infection. Most of the participants in both the infected and non-infected groups were healthy, young students studying abroad. The infected group consisted of large numbers of people returning from the United Kingdom and the Philippines. This factor somehow correlated with these countries’ community outbreaks during that period. Moreover, COVID-19 patients responded that there were fewer public preventive measures taken in the local community where they stayed before returning to Macao SAR, such as closing entertainment venues, traffic restrictions, and testing COVID-19 for all symptomatic patients. From Wuhan’s report in China, suspending intracity public transport, closing entertainment venues, and banning public gatherings were associated with reductions in case incidence [ 13 ]. Although the statistical power was insufficient to distinguish differences in public measures among the uninfected and infected groups in this study, our data showed that each high-risk gathering activity (interacting with people within 2 m without wearing a mask) increased the risk of COVID-19 infection by 12.9%.

Significant exposure to COVID-19 was commonly defined as face-to-face contact within 6 ft (~ 1.83 m) with symptomatic COVID-19 patients that was sustained for at least a few minutes [ 14 ]. The transmission of viruses was reported to be lower with physical distancing of 1 m or more, for which protection would be increased with increasing distance [ 15 ]. Based on our data, physical contact with suspected/confirmed COVID-19 cases increased the risk of infection by 12-fold. While this contact history may be retrospective in nature, this finding revealed the differences in personal hygiene behaviour between the control group and the COVID-19 infection group when they had contact with symptomatic individuals. In the infection group, 50.4% fewer people wore a mask when contacting people with respiratory symptoms, and 45.3% fewer people washed hands afterwards. As a result, we believe that personal protective health behaviour such as hand hygiene, especially after high-risk activities, and mask-wearing could be crucial to prevent transmission from highly contagious individuals. However, in this study, the small sample size of patients with definite contact history limited the calculation of the actual effect size of these protective measures.

The WHO stated that the use of a mask alone is insufficient to provide an adequate level of protection and that other measures such as hand hygiene should also be adopted to prevent human-to-human transmission of COVID-19 [ 16 ]. Traditionally, the role of wearing a mask by a healthy citizen has been controversial, and the limited evidence has mostly been associated with a healthcare setting [ 17 , 18 ]. From a systematic review and meta-analysis, face mask use could result in a large reduction in the risk of reduction (pooled adjusted odds ratio 0.18) [ 15 ]. Our data showed similar evidence in that outdoor mask wearing in healthy populations reduced COVID-19 risk by 69.3% after adjusting for contact history, hand hygiene practice, and high-risk gathering activities. However, the questionnaire in this study did not specify the type of face mask worn. Although incorrect use of masks may lead to virus colonization and self-contamination, [ 19 ] 79.9% of our participants thought that mask wearing reduced the frequency of accidentally touching the mouth and nose area, with 95.1% of them recognizing the importance of hand hygiene after using a mask. This result indicated that most of the participants had a good perceived hygiene attitude on mask usage; hence, the protective effect might exceed the potential risk in this circumstance. We believe that mask wearing by “non-sick” people could potentially block the spread of contagious droplets from asymptomatic patients during social activities as well as provide the wearer with a symbol to enhance the awareness of protective measures and generate a sense of safety and well-being. Nonetheless, multiple factors should be taken into consideration before implementing a universal mask policy in a healthy population, including cultural differences, scientific evidence in different settings, adequacy of perceived knowledge on mask use in the general population, adaptation difficulties in people with special needs and, most importantly, the scarcity of resources and logistic support [ 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 ].

Previous studies mostly aimed to evaluate the protective efficacy of physical distancing, wearing masks, eye protection, etc., in both healthcare and non-healthcare settings [ 15 , 24 , 25 ]. However, there is still scarce evidence regarding hand hygiene in preventing individual COVID-19 infections. Hand hygiene is regarded as one of the most effective measures for transmissible disease prevention [ 18 , 26 ]. Special emphases were placed on the timing and duration of cleaning in this study. Our data suggested that the most important protective factor for COVID-19 was the timing of hand hygiene practice and not the frequency. The habit of frequent handwashing after outdoor activities and before touching the mouth/nose area reduced the risk of infection by 97.9 and 69.7%, respectively. There is evidence that viruses can remain viable and infectious on surfaces for up to days, leading to plausible fomite transmission [ 27 ]. Transmission of the virus via contaminated surfaces was also proven to be a possible means other than via respiratory droplets from face-to-face contact [ 28 , 29 ]. These results reiterate the importance of practising hand hygiene following outdoor activities, even if no obvious high-risk contact was noted, as the battlefield is limited not only to healthcare settings but also to asymptomatic or presymptomatic carriers in public places [ 4 ]. Nevertheless, the duration of handwashing was seemingly shorter in the infected group than in the non-infected group, although the difference was not statistically significant. The primary challenges associated with hand hygiene efficacy are the laxity of practice and atopic dermatitis [ 30 , 31 ]. A cross-sectional survey of the general public reported that only approximately 31% of the expected behaviour and practices were observed in at least 80% of the participants [ 32 ]. Our data showed that the percentages of each hand hygiene behaviour were higher than those reported previously [ 32 ]. This fact may contribute to awareness of the COVID-19 pandemic and active advocation and education to the public by different authorities and organizations. During the 2003 SARS outbreak, compliance with hand hygiene practice was also improved among medical students [ 33 ].

This study had several limitations. First, this was a retrospective survey, and recall bias was inevitable. However, the effect of bias was minimized since the information requested was about simple concrete behaviour and events that happened recently, and the associations had strong effect sizes. Second, the sample size of the infected group was relatively small compared to that of the non-infected group, which was limited due to the unavailability of confirmed cases. In addition, the low response rate in the control group may have been a consequence of implementing an internet-based questionnaire. Future studies may consider using reminders to boost the response rate. Third, the lack of objective evaluation of behaviour and practice may not reflect the consistency between attitude and actual behaviour. Furthermore, the results may be limited to the Asian population during the COVID-19 outbreak, and generalization of these interpretations to other populations should be thoughtfully considered.

Our data provide evidence of the effectiveness of personal protective measures against COVID-19 infection. Although vaccines are now available for emergency use in many countries, there is some uncertainty around the efficacy of stopping asymptomatic spread via vaccination. It is not unreasonable that policymakers continue to educate the public about avoiding high-risk gatherings, wearing a mask whenever outdoors, and practising decent hand hygiene along with the immunization scheme. Based on the relatively small sample size in our patient group, future studies may recruit more participants to validate the effectiveness of these measures in different populations.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the article and its additional file [see Additional file 1 ].

Abbreviations

Novel coronavirus disease 2019; WHO: World Health Organization

Centro Hospitalar Conde de São Januário

WHO. WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020: World Health Organization; 2020 [13 April 2020]. Available from: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19%2D%2D-11-march-2020 .

WHO. Weekly epidemiological update - 5 January 2021. World Health Organization. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update%2D%2D-5-january-2021 .

Wolfel R, Corman VM, Guggemos W, Seilmaier M, Zange S, Muller MA, et al. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature. 2020. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x .

Wiersinga WJ, Rhodes A, Cheng AC, Peacock SJ, Prescott HC. Pathophysiology, transmission, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA. 2020;324(8):782–93. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.12839 .

Ganyani T, Kremer C, Chen D, Torneri A, Faes C, Wallinga J, et al. Estimating the generation interval for coronavirus disease (COVID-19) based on symptom onset data, March 2020. 2020;25(17):2000257. Available from: https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.17.2000257 .

Haynes BF, Corey L, Fernandes P, Gilbert PB, Hotez PJ, Rao S, et al. Prospects for a safe COVID-19 vaccine. Science translational medicine. 2020;12(568). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.abe0948 .

Gostin LO, Wiley LF. Governmental Public Health Powers During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Stay-at-home Orders, Business Closures, and Travel Restrictions. JAMA. 2020. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.5460 .

Colbourn T. COVID-19: extending or relaxing distancing control measures. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(5):e236–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30072-4 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Klompas M, Morris CA, Sinclair J, Pearson M, Shenoy ES. Universal masking in hospitals in the Covid-19 era. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):e63. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2006372 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Phelan AL, Katz R, Gostin LO. The novel coronavirus originating in Wuhan, China: challenges for Global Health governance. JAMA. 2020;323(8):709–10. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.1097 .

The Lancet Respiratory M. COVID-19: delay, mitigate, and communicate. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(4):321. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30128-4 .

Norman P, Conner M. Health Behavior. Reference Module in Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Psychology: Elsevier. 2017. p. 1–37.

Google Scholar

Tian H, Liu Y, Li Y, Wu C-H, Chen B, Kraemer MUG, et al. An investigation of transmission control measures during the first 50 days of the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Science. 2020:eabb6105. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abb6105 .

CDC. Prevent Getting Sick, How COVID-19 Spreads: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/how-covid-spreads.html .

Chu DK, Akl EA, Duda S, Solo K, Yaacoub S, Schünemann HJ, et al. Physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2020;395(10242):1973–87. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31142-9 .

WHO. Advice on the use of masks in the context of COVID-19. 2020 [13 April 2020]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail/advice-on-the-use-of-masks-in-the-community-during-home-care-and-in-healthcare-settings-in-the-context-of-the-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov)-outbreak .

Offeddu V, Yung CF, Low MSF, Tam CC. Effectiveness of masks and respirators against respiratory infections in healthcare workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(11):1934–42. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cix681 .

Seto WH, Tsang D, Yung RWH, Ching TY, Ng TK, Ho M, et al. Effectiveness of precautions against droplets and contact in prevention of nosocomial transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). The lancet. 2003;361(9368):1519-20. Available from: 2003. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13168-6 .

Chughtai AA, Stelzer-Braid S, Rawlinson W, Pontivivo G, Wang Q, Pan Y, et al. Contamination by respiratory viruses on outer surface of medical masks used by hospital healthcare workers. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):491. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4109-x .

Ranney ML, Griffeth V, Jha AK. Critical supply shortages — the need for ventilators and personal protective equipment during the Covid-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):e41. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2006141 .

Emanuel EJ, Persad G, Upshur R, Thome B, Parker M, Glickman A, et al. Fair Allocation of Scarce Medical Resources in the Time of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsb2005114 .

Lamptey E, Serwaa D. The use of Zipline drones technology for COVID-19 samples transportation in Ghana. HighTech Innov J. 2020;1(2):67–71. Available from: https://doi.org/10.28991/HIJ-2020-01-02-03 .

Parenteau CI, Bent S, Hossain B, Chen Y, Widjaja F, Breard M, et al. COVID-19 Related Challenges and Advice from Parents of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. SciMed J. 2020;2:73–82. Available from: https://doi.org/10.28991/SciMedJ-2020-02-SI-6 .

Tipaldi MA, Lucertini E, Orgera G, Zolovkins A, Lauirno F, Ronconi E, et al. How to Manage the COVID-19 Diffusion in the Angiography Suite: Experiences and Results of an Italian Interventional Radiology Unit. SciMed J. 2020;2:1–8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.28991/SciMedJ-2020-02-SI-1 .

Hanscom D, Clawson DR, Porges SW, Bunnage R, Aria L, Lederman S, et al. Polyvagal and global cytokine theory of safety and threat Covid-19 – plan B. SciMed J. 2020;2:9–27. Available from: https://doi.org/10.28991/SciMedJ-2020-02-SI-2 .

Aiello AE, Coulborn RM, Perez V, Larson EL. Effect of hand hygiene on infectious disease risk in the community setting: a meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(8):1372-81. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.35057 .

van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, Holbrook MG, Gamble A, Williamson BN, et al. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(16):1564–7. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2004973 .

Chia PY, Coleman KK, Tan YK, Ong SWX, Gum M, Lau SK, et al. Detection of air and surface contamination by SARS-CoV-2 in hospital rooms of infected patients. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):2800. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16670-2 .

van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, Holbrook MG, Gamble A, Williamson BN, et al. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. 2020;382(16):1564-7. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2004973 .

Trampuz A, Widmer AF. Hand hygiene: a frequently missed lifesaving opportunity during patient care. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79(1):109–16. Available from: https://doi.org/10.4065/79.1.109 .

Beiu C, Mihai M, Popa L, Cima L, Popescu MN. Frequent hand washing for COVID-19 prevention can cause hand dermatitis: management tips. Cureus. 2020;12(4):e7506. Available from: https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.7506 .

Pang J, Chua SWJL, Hsu L. Current knowledge, attitude and behaviour of hand and food hygiene in a developed residential community of Singapore: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):577. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1910-3 .

Wong T-W, Tam WW-S. Handwashing practice and the use of personal protective equipment among medical students after the SARS epidemic in Hong Kong. Am J Infect Control. 2005;33(10):580–6. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2005.05.025 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

All authors received no specific funding for this work.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Macao Academy of Medicine, Health Bureau, Macao SAR, China

Chon Fu Lio & Hou Hon Cheong

Department of Internal Medicine, Centro Hospitalar Conde de São Januário, Health Bureau, 2nd Floor, Health Bureau Admin, Building, No.339 Rua Nova a Guia, Macao SAR, China

Chin Ion Lei

Serviços de Saúde, Edifício da Administração dos Serviços de Saúde, Rua Nova à Guia, n.° 339, Macau SAR, China

Health Bureau, Macao SAR, China

Iek Long Lo & Lan Yao

Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Health Bureau, Macao SAR, China

Chong Lam & Iek Hou Leong

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

C.I.L. and I.L.L. conceived and designed the study. C.F.L. and H.H.C. wrote the main manuscript text and prepared figures and tables. L.Y., C.L. and I.H.L. analysed the data. All authors reviewed the manuscript and contributed to the preparation of the manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Chin Ion Lei .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The research was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee, Centro Hospitalar Conde de São Januário, Health Bureau, Macao SAR, China. Informed consent was acquired from all participants when they accessed the electronic questionnaire via web-based systems before answering the questionnaires, while written informed consent was acquired and collected if a participant used a paper questionnaire. For participants aged between 15 and 18 years, written parental consent was waived by Medical Ethical Committee, Centro Hospitalar Conde de São Januário, Health Bureau based on the following: 1) the risk of the research to the participants was relatively low compared to the general risk encountered in daily life; 2) quarantine and infection control procedures precluded the possibility of obtaining written parental consent; and 3) only those aged 15 years or above were enrolled, as they are more capable of expressing their wishes for participation and better understand the research consent than younger people.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1., rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Lio, C.F., Cheong, H.H., Lei, C.I. et al. Effectiveness of personal protective health behaviour against COVID-19. BMC Public Health 21 , 827 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10680-5

Download citation

Received : 16 October 2020

Accepted : 22 March 2021

Published : 29 April 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10680-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Handwashing

- Social distancing

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Open access

- Published: 23 November 2020

Global strategies and effectiveness for COVID-19 prevention through contact tracing, screening, quarantine, and isolation: a systematic review

- Tadele Girum 1 ,

- Kifle Lentiro 1 ,

- Mulugeta Geremew 2 ,

- Biru Migora 2 &

- Sisay Shewamare 3

Tropical Medicine and Health volume 48 , Article number: 91 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

44k Accesses

103 Citations

27 Altmetric

Metrics details

COVID-19 is an emerging disease caused by highly contagious virus called SARS-CoV-2. It caused an extensive health and economic burden around the globe. There is no proven effective treatment yet, except certain preventive mechanisms. Some studies assessing the effects of different preventive strategies have been published. However, there is no conclusive evidence. Therefore, this study aimed to review evidences related to COVID-19 prevention strategies achieved through contact tracing, screening, quarantine, and isolation to determine best practices.

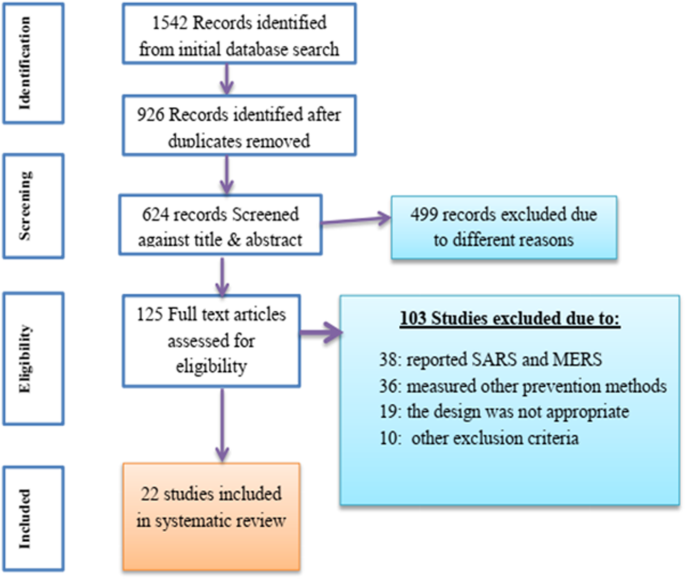

We conducted a systematic review in accordance with the PRISMA and Cochrane guidelines by searching articles from major medical databases such as PubMed/Medline, Global Health Database, Embase, CINAHL, Google Scholar, and clinical trial registries. Non-randomized and modeling articles published to date in areas of COVID prevention with contact tracing, screening, quarantine, and isolation were included. Two experts screened the articles and assessed risk of bias with ROBINS-I tool and certainty of evidence with GRADE approach. The findings were presented narratively and in tabular form.

We included 22 (9 observational and 13 modeling) studies. The studies consistently reported the benefit of quarantine, contact tracing, screening, and isolation in different settings. Model estimates indicated that quarantine of exposed people averted 44 to 81% of incident cases and 31 to 63% of deaths. Quarantine along with others can also halve the reproductive number and reduce the incidence, thus, shortening the epidemic period effectively. Early initiation of quarantine, operating large-scale screenings, strong contact tracing systems, and isolation of cases can effectively reduce the epidemic. However, adhering only to screening and isolation with lower coverage can miss more than 75% of asymptomatic cases; hence, it is not effective.

Quarantine, contact tracing, screening, and isolation are effective measures of COVID-19 prevention, particularly when integrated together. In order to be more effective, quarantine should be implemented early and should cover a larger community.

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an emerging infectious disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The novel coronavirus was first identified in December 2019 in Wuhan China, then spread globally within weeks and resulted in an ongoing pandemic [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ]. Currently, coronavirus is affecting 213 countries and territories around the world. As of 27 May 2020, more than 5.7 million cases and 353,664 deaths were reported globally [ 2 , 3 ]. Thirteen percent of the closed cohorts and 2–5% of the total cohort reportedly died [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ]. The USA, Brazil, Russia, Spain, Italy, France, and the UK are the most affected countries [ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ].