- OC Test Preparation

- Selective School Test Preparation

- Maths Acceleration

- English Advanced

- Maths Standard

- Maths Advanced

- Maths Extension 1

- English Standard

- English Common Module

- Maths Standard 2

- Maths Extension 2

- Business Studies

- Legal Studies

- UCAT Exam Preparation

Select a year to see available courses

- Level 7 English

- Level 7 Maths

- Level 8 English

- Level 8 Maths

- Level 9 English

- Level 9 Maths

- Level 9 Science

- Level 10 English

- Level 10 Maths

- Level 10 Science

- VCE English Units 1/2

- VCE Biology Units 1/2

- VCE Chemistry Units 1/2

- VCE Physics Units 1/2

- VCE Maths Methods Units 1/2

- VCE English Units 3/4

- VCE Maths Methods Units 3/4

- VCE Biology Unit 3/4

- VCE Chemistry Unit 3/4

- VCE Physics Unit 3/4

- Castle Hill

- Strathfield

- Sydney City

- Inspirational Teachers

- Great Learning Environments

- Proven Results

- OC Test Guide

- Selective Schools Guide

- Reading List

- Year 6 English

- NSW Primary School Rankings

- Year 7 & 8 English

- Year 9 English

- Year 10 English

- Year 11 English Standard

- Year 11 English Advanced

- Year 12 English Standard

- Year 12 English Advanced

- HSC English Skills

- How To Write An Essay

- How to Analyse Poetry

- English Techniques Toolkit

- Year 7 Maths

- Year 8 Maths

- Year 9 Maths

- Year 10 Maths

- Year 11 Maths Advanced

- Year 11 Maths Extension 1

- Year 12 Maths Standard 2

- Year 12 Maths Advanced

- Year 12 Maths Extension 1

- Year 12 Maths Extension 2

- Year 11 Biology

- Year 11 Chemistry

- Year 11 Physics

- Year 12 Biology

- Year 12 Chemistry

- Year 12 Physics

- Physics Practical Skills

- Periodic Table

- NSW High Schools Guide

- NSW High School Rankings

- ATAR & Scaling Guide

- HSC Study Planning Kit

- Student Success Secrets

- Set Location

- 1300 008 008

Welcome to Matrix Education

To ensure we are showing you the most relevant content, please select your location below.

How to Write a Scientific Report | Step-by-Step Guide

Got to document an experiment but don't know how? In this post, we'll guide you step-by-step through how to write a scientific report and provide you with an example.

Get free study tips and resources delivered to your inbox.

Join 75,893 students who already have a head start.

" * " indicates required fields

You might also like

- Grace’s Hacks: How to Stay Motivated and Banish Bad Habits

- 9 Must-Know Tips to Study Effectively in the Holidays and Stay Motivated

- Ultimate King Lear Cheatsheet | English Advanced

- Scientific Method and Science Skills

- 20 Must-Read Books For Year 7-10 Students

Related courses

Year 9 science, year 10 science.

Is your teacher expecting you to write an experimental report for every class experiment? Are you still unsure about how to write a scientific report properly? Don’t fear! We will guide you through all the parts of a scientific report, step-by-step.

How to write a scientific report:

- What is a scientific report

- General rules to write Scientific reports

- Syllabus dot point

- Introduction/Background information

- Risk assessment

What is a scientific report?

A scientific report documents all aspects of an experimental investigation. This includes:

- The aim of the experiment

- The hypothesis

- An introduction to the relevant background theory

- The methods used

- The results

- A discussion of the results

- The conclusion

Scientific reports allow their readers to understand the experiment without doing it themselves. In addition, scientific reports give others the opportunity to check the methodology of the experiment to ensure the validity of the results.

A scientific report is written in several stages. We write the introduction, aim, and hypothesis before performing the experiment, record the results during the experiment, and complete the discussion and conclusions after the experiment.

But, before we delve deeper into how to write a scientific report, we need to have a science experiment to write about! Read our 7 Simple Experiments You Can Do At Home article and see which one you want to do.

General rules about writing scientific reports

Learning how to write a scientific report is different from writing English essays or speeches!

You have to use:

- Passive voice (which you should avoid when writing for other subjects like English!)

- Past-tense language

- Headings and subheadings

- A pencil to draw scientific diagrams and graphs

- Simple and clear lines for scientific diagrams

- Tables and graphs where necessary

Structure of scientific reports:

Now that you know the general rules on how to write scientific reports, let’s look at the conventions for their structure!

The title should simply introduce what your experiment is about.

The Role of Light in Photosynthesis

2. Introduction/Background information

Write a paragraph that gives your readers background information to understand your experiment.

This includes explaining scientific theories, processes and other related knowledge.

Photosynthesis is a vital process for life. It occurs when plants intake carbon dioxide, water, and light, and results in the production of glucose and water. The light required for photosynthesis is absorbed by chlorophyll, the green pigment of plants, which is contained in the chloroplasts.

The glucose produced through photosynthesis is stored as starch, which is used as an energy source for the plant and its consumers.

The presence of starch in the leaves of a plant indicates that photosynthesis has occurred.

The aim identifies what is going to be tested in the experiment. This should be short, concise and clear.

The aim of the experiment is to test whether light is required for photosynthesis to occur.

4. Hypothesis

The hypothesis is a prediction of the outcome of the experiment. You have to use background information to make an educated prediction.

It is predicted that photosynthesis will occur only in leaves that are exposed to light and not in leaves that are not exposed to light. This will be indicated by the presence or absence of starch in the leaves.

5. Risk assessment

Identify the hazards associated with the experiment and provide a method to prevent or minimise the risks. A hazard is something that can cause harm, and the risk is the likelihood that harm will occur from the hazard.

A table is an excellent way to present your risk assessment.

Remember, you have to specify the type of harm that can occur because of the hazard. It is not enough to simply identify the hazard.

- Do not write: “Scissors are sharp”

- Instead, you have to write: “Scissors are sharp and can cause injury”

The method has 3 parts:

- A list of every material used

- Steps of what you did in the experiment

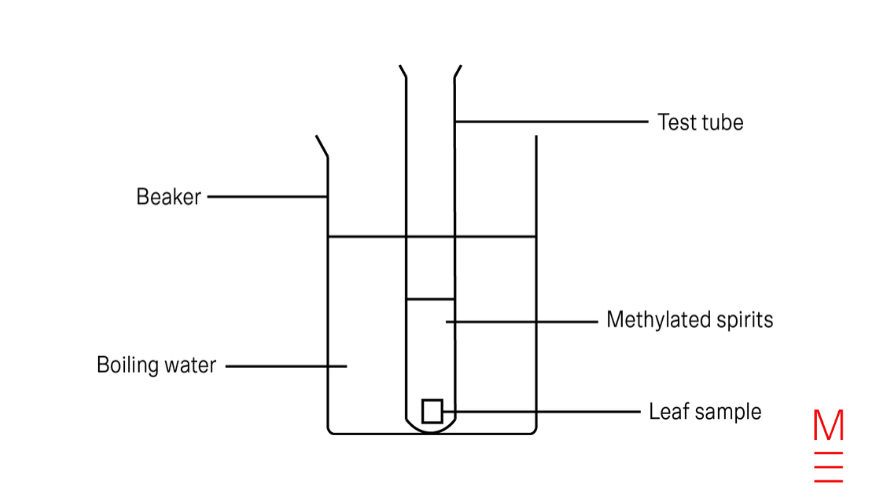

- A scientific diagram of the experimental apparatus

Let’s break down what you need to do for each section.

6a. Materials

This must list every piece of equipment and material you used in the experiment.

Remember, you need to also specify the amount of each material you used.

- 1 geranium plant

- Aluminium foil

- 2 test tubes

- 1 test tube rack

- 1 pair of scissors

- 1 250 mL beaker

- 1 pair of forceps

- 1 10 mL measuring cylinder

- Iodine solution (5 mL)

- Methylated spirit (50ml)

- Boiling water

- 2 Petri dishes

The rule of thumb is that you should write the method in a clear way so that readers are able to repeat the experiment and get similar results.

Using a numbered list for the steps of your experimental procedure is much clearer than writing a whole paragraph of text. The steps should:

- Be written in a sequential order, based on when they were performed.

- Specify any equipment that was used.

- Specify the quantity of any materials that were used.

You also need to use past tense and passive voice when you are writing your method. Scientific reports are supposed to show the readers what you did in the experiment, not what you will do.

- Aluminium foil was used to fully cover a leaf of the geranium plant. The plant was left in the sun for three days.

- On the third day, the covered leaf and 1 non-covered leaf were collected from the plant. The foil was removed from the covered leaf, and a 1 cm square was cut from each leaf using a pair of scissors.

- 150 mL of water was boiled in a kettle and poured into a 250 mL beaker.

- Using forceps, the 1 cm square of covered leaf was placed into the beaker of boiling water for 2 minutes. It was then placed in a test tube labelled “dark”.

- The water in the beaker was discarded and replaced with 150 mL of freshly boiled water.

- Using forceps, the 1 cm square non-covered leaf was placed into the beaker of boiling water for 2 minutes. It was then placed in a test tube labelled “light”

- 5 mL of methylated spirit was measured with a measuring cylinder and poured into each test tube so that the leaves were fully covered.

- The water in the beaker was replaced with 150 mL of freshly boiled water and both the “light” and “dark” test tubes were immersed in the beaker of boiling water for 5 minutes.

- The leaves were collected from each test tube with forceps, rinsed under cold running water, and placed onto separate labelled Petri dishes.

- 3 drops of iodine solution were added to each leaf.

- Both Petri dishes were placed side by side and observations were recorded.

- The experiment was repeated 5 times, and results were compared between different groups.

6c. Diagram

After you finish your steps, it is time to draw your scientific diagrams! Here are some rules for drawing scientific diagrams:

- Always use a pencil to draw your scientific diagrams.

- Use simple, sharp, 2D lines and shapes to draw your diagram. Don’t draw 3D shapes or use shading.

- Label everything in your diagram.

- Use thin, straight lines to label your diagram. Do not use arrows.

- Ensure that the label lines touch the outline of the equipment you are labelling and not cross over it or stop short of it

- The label lines should never cross over each other.

- Use a ruler for any straight lines in your diagram.

- Draw a sufficiently large diagram so all components can be seen clearly.

This is where you document the results of your experiment. The data that you record for your experiment will generally be qualitative and/or quantitative.

Qualitative data is data that relates to qualities and is based on observations (qualitative – quality). This type of data is descriptive and is recorded in words. For example, the colour changed from green to orange, or the liquid became hot.

Quantitative data refers to numerical data (quantitative – quantity). This type of data is recorded using numbers and is either measured or counted. For example, the plant grew 5.2 cm, or there were 5 frogs.

You also need to record your results in an appropriate way. Most of the time, a table is the best way to do this.

Here are some rules to using tables

- Use a pencil and a ruler to draw your table

- Draw neat and straight lines

- Ensure that the table is closed (connect all your lines)

- Don’t cross your lines (erase any lines that stick out of the table)

- Use appropriate columns and rows

- Properly name each column and row (including the units of measurement in brackets)

- Do not write your units in the body of your table (units belong in the header)

- Always include a title

Note : If your results require calculations, clearly write each step.

Observations of the effects of light on the amount of starch in plant leaves.

If quantitative data was recorded, the data is often also plotted on a graph.

8. Discussion

The discussion is where you analyse and interpret your results, and identify any experimental errors or possible areas of improvements.

You should divide your discussion as follows.

1. Trend in the results

Describe the ‘trend’ in your results. That is, the relationship you observed between your independent and dependent variables.

The independent variable is the variable that you are changing in the experiment. In this experiment, it is the amount of light that the leaves are exposed to.

The dependent variable is the variable that you are measuring in the experiment, In this experiment, it is the presence of starch in the leaves.

Explain how a particular result is achieved by referring to scientific knowledge, theories and any other scientific resources you find. 2. Scientific explanation:

The presence of starch is indicated when the addition of iodine causes the leaf to turn dark purple. The results show that starch was present in the leaves that were exposed to light, while the leaves that were not exposed to light did not contain starch.

2. Scientific explanation:

Provide an explanation of the results using scientific knowledge, theories and any other scientific resources you find.

As starch is produced during photosynthesis, these results show that light plays a key role in photosynthesis.

3. Validity

Validity refers to whether or not your results are valid. This can be done by examining your variables.

VA lidity = VA riables

Identify the independent, dependent, controlled variables and the control experiment (if you have one).

The controlled variables are the variables that you keep the same across all tests e.g. the size of the leaf sample.

The control experiment is where you don’t apply an independent variable. It is untouched for the whole experiment.

Ensure that you never change more than one variable at a time!

The independent variable of the experiment was amount of light that the leaves were exposed to (the covered and uncovered geranium leaf), while the dependent variable was the presence of starch. The controlled variables were the size of the leaf sample, the duration of the experiment, the amount of time the solutions were heated, and the amount of iodine solution used.

4. Reliability

Identify how you ensured the reliability of the results.

RE liability = RE petition

Show that you repeated your experiments, cross-checked your results with other groups or collated your results with the class.

The reliability of the results was ensured by repeating the experiment 5 times and comparing results with other groups. Since other groups obtained comparable results, the results are reliable.

5. Accuracy

Accuracy should be discussed if your results are in the form of quantitative data, and there is an accepted value for the result.

Accuracy would not be discussed for our example photosynthesis experiment as qualitative data was collected, however it would if we were measuring gravity using a pendulum:

The measured value of gravity was 9.8 m/s 2 , which is in agreement with the accepted value of 9.8 m/s 2 .

6. Possible improvements

Identify any errors or risks found in the experiment and provide a method to improve it.

If there are none, then suggest new ways to improve the experimental design, and/or minimise error and risks.

Possible improvements could be made by including control experiments. For example, testing whether the iodine solution turns dark purple when added to water or methylated spirits. This would help to ensure that the purple colour observed in the experiments is due to the presence of starch in the leaves rather than impurities.

9. Conclusion

State whether the aim was achieved, and if your hypothesis was supported.

The aim of the investigation was achieved, and it was found that light is required for photosynthesis to occur. This was evidenced by the presence of starch in leaves that had been exposed to light, and the absence of starch in leaves that had been unexposed. These results support the proposed hypothesis.

Written by Matrix Science Team

© Matrix Education and www.matrix.edu.au, 2023. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Matrix Education and www.matrix.edu.au with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Year 9 Science tutoring at Matrix is known for helping students build a strong foundation before studying Biology, Chemistry or Physics in senior school.

Learning methods available

Level 9 Science course that covers every aspect of the new Victorian Science Curriculum.

Level 10 Science course that covers every aspect of the new Victorian Science Curriculum.

Year 10 Science tutoring at Matrix is known for helping students build a strong foundation before studying Biology, Chemistry or Physics in Year 11 and 12.

Related articles

Overcoming an English Slump in Years 9 and 10

English slumps during Years 9 and 10 can really impact a student's performance when they get in Year 12. Read this post and learn how to stay on top of English so you don't need to play catch up later.

How to Use Quotations and Examples – Dos and Don’ts

Do you struggle incorporating examples or quotations into your writing? In this article, we share the dos and don'ts that Matrix students learn so they can impress their teachers at school.

Amanda’s Hacks: How to Get into a Routine for Exam Success to Achieve a 99.85 ATAR

Exams are stressful... However, that doesn't mean you can't reduce the stress! In this article, Amanda shares her best tips to prepare for exams and ace them.

Scientific Reports

What this handout is about.

This handout provides a general guide to writing reports about scientific research you’ve performed. In addition to describing the conventional rules about the format and content of a lab report, we’ll also attempt to convey why these rules exist, so you’ll get a clearer, more dependable idea of how to approach this writing situation. Readers of this handout may also find our handout on writing in the sciences useful.

Background and pre-writing

Why do we write research reports.

You did an experiment or study for your science class, and now you have to write it up for your teacher to review. You feel that you understood the background sufficiently, designed and completed the study effectively, obtained useful data, and can use those data to draw conclusions about a scientific process or principle. But how exactly do you write all that? What is your teacher expecting to see?

To take some of the guesswork out of answering these questions, try to think beyond the classroom setting. In fact, you and your teacher are both part of a scientific community, and the people who participate in this community tend to share the same values. As long as you understand and respect these values, your writing will likely meet the expectations of your audience—including your teacher.

So why are you writing this research report? The practical answer is “Because the teacher assigned it,” but that’s classroom thinking. Generally speaking, people investigating some scientific hypothesis have a responsibility to the rest of the scientific world to report their findings, particularly if these findings add to or contradict previous ideas. The people reading such reports have two primary goals:

- They want to gather the information presented.

- They want to know that the findings are legitimate.

Your job as a writer, then, is to fulfill these two goals.

How do I do that?

Good question. Here is the basic format scientists have designed for research reports:

- Introduction

Methods and Materials

This format, sometimes called “IMRAD,” may take slightly different shapes depending on the discipline or audience; some ask you to include an abstract or separate section for the hypothesis, or call the Discussion section “Conclusions,” or change the order of the sections (some professional and academic journals require the Methods section to appear last). Overall, however, the IMRAD format was devised to represent a textual version of the scientific method.

The scientific method, you’ll probably recall, involves developing a hypothesis, testing it, and deciding whether your findings support the hypothesis. In essence, the format for a research report in the sciences mirrors the scientific method but fleshes out the process a little. Below, you’ll find a table that shows how each written section fits into the scientific method and what additional information it offers the reader.

Thinking of your research report as based on the scientific method, but elaborated in the ways described above, may help you to meet your audience’s expectations successfully. We’re going to proceed by explicitly connecting each section of the lab report to the scientific method, then explaining why and how you need to elaborate that section.

Although this handout takes each section in the order in which it should be presented in the final report, you may for practical reasons decide to compose sections in another order. For example, many writers find that composing their Methods and Results before the other sections helps to clarify their idea of the experiment or study as a whole. You might consider using each assignment to practice different approaches to drafting the report, to find the order that works best for you.

What should I do before drafting the lab report?

The best way to prepare to write the lab report is to make sure that you fully understand everything you need to about the experiment. Obviously, if you don’t quite know what went on during the lab, you’re going to find it difficult to explain the lab satisfactorily to someone else. To make sure you know enough to write the report, complete the following steps:

- What are we going to do in this lab? (That is, what’s the procedure?)

- Why are we going to do it that way?

- What are we hoping to learn from this experiment?

- Why would we benefit from this knowledge?

- Consult your lab supervisor as you perform the lab. If you don’t know how to answer one of the questions above, for example, your lab supervisor will probably be able to explain it to you (or, at least, help you figure it out).

- Plan the steps of the experiment carefully with your lab partners. The less you rush, the more likely it is that you’ll perform the experiment correctly and record your findings accurately. Also, take some time to think about the best way to organize the data before you have to start putting numbers down. If you can design a table to account for the data, that will tend to work much better than jotting results down hurriedly on a scrap piece of paper.

- Record the data carefully so you get them right. You won’t be able to trust your conclusions if you have the wrong data, and your readers will know you messed up if the other three people in your group have “97 degrees” and you have “87.”

- Consult with your lab partners about everything you do. Lab groups often make one of two mistakes: two people do all the work while two have a nice chat, or everybody works together until the group finishes gathering the raw data, then scrams outta there. Collaborate with your partners, even when the experiment is “over.” What trends did you observe? Was the hypothesis supported? Did you all get the same results? What kind of figure should you use to represent your findings? The whole group can work together to answer these questions.

- Consider your audience. You may believe that audience is a non-issue: it’s your lab TA, right? Well, yes—but again, think beyond the classroom. If you write with only your lab instructor in mind, you may omit material that is crucial to a complete understanding of your experiment, because you assume the instructor knows all that stuff already. As a result, you may receive a lower grade, since your TA won’t be sure that you understand all the principles at work. Try to write towards a student in the same course but a different lab section. That student will have a fair degree of scientific expertise but won’t know much about your experiment particularly. Alternatively, you could envision yourself five years from now, after the reading and lectures for this course have faded a bit. What would you remember, and what would you need explained more clearly (as a refresher)?

Once you’ve completed these steps as you perform the experiment, you’ll be in a good position to draft an effective lab report.

Introductions

How do i write a strong introduction.

For the purposes of this handout, we’ll consider the Introduction to contain four basic elements: the purpose, the scientific literature relevant to the subject, the hypothesis, and the reasons you believed your hypothesis viable. Let’s start by going through each element of the Introduction to clarify what it covers and why it’s important. Then we can formulate a logical organizational strategy for the section.

The inclusion of the purpose (sometimes called the objective) of the experiment often confuses writers. The biggest misconception is that the purpose is the same as the hypothesis. Not quite. We’ll get to hypotheses in a minute, but basically they provide some indication of what you expect the experiment to show. The purpose is broader, and deals more with what you expect to gain through the experiment. In a professional setting, the hypothesis might have something to do with how cells react to a certain kind of genetic manipulation, but the purpose of the experiment is to learn more about potential cancer treatments. Undergraduate reports don’t often have this wide-ranging a goal, but you should still try to maintain the distinction between your hypothesis and your purpose. In a solubility experiment, for example, your hypothesis might talk about the relationship between temperature and the rate of solubility, but the purpose is probably to learn more about some specific scientific principle underlying the process of solubility.

For starters, most people say that you should write out your working hypothesis before you perform the experiment or study. Many beginning science students neglect to do so and find themselves struggling to remember precisely which variables were involved in the process or in what way the researchers felt that they were related. Write your hypothesis down as you develop it—you’ll be glad you did.

As for the form a hypothesis should take, it’s best not to be too fancy or complicated; an inventive style isn’t nearly so important as clarity here. There’s nothing wrong with beginning your hypothesis with the phrase, “It was hypothesized that . . .” Be as specific as you can about the relationship between the different objects of your study. In other words, explain that when term A changes, term B changes in this particular way. Readers of scientific writing are rarely content with the idea that a relationship between two terms exists—they want to know what that relationship entails.

Not a hypothesis:

“It was hypothesized that there is a significant relationship between the temperature of a solvent and the rate at which a solute dissolves.”

Hypothesis:

“It was hypothesized that as the temperature of a solvent increases, the rate at which a solute will dissolve in that solvent increases.”

Put more technically, most hypotheses contain both an independent and a dependent variable. The independent variable is what you manipulate to test the reaction; the dependent variable is what changes as a result of your manipulation. In the example above, the independent variable is the temperature of the solvent, and the dependent variable is the rate of solubility. Be sure that your hypothesis includes both variables.

Justify your hypothesis

You need to do more than tell your readers what your hypothesis is; you also need to assure them that this hypothesis was reasonable, given the circumstances. In other words, use the Introduction to explain that you didn’t just pluck your hypothesis out of thin air. (If you did pluck it out of thin air, your problems with your report will probably extend beyond using the appropriate format.) If you posit that a particular relationship exists between the independent and the dependent variable, what led you to believe your “guess” might be supported by evidence?

Scientists often refer to this type of justification as “motivating” the hypothesis, in the sense that something propelled them to make that prediction. Often, motivation includes what we already know—or rather, what scientists generally accept as true (see “Background/previous research” below). But you can also motivate your hypothesis by relying on logic or on your own observations. If you’re trying to decide which solutes will dissolve more rapidly in a solvent at increased temperatures, you might remember that some solids are meant to dissolve in hot water (e.g., bouillon cubes) and some are used for a function precisely because they withstand higher temperatures (they make saucepans out of something). Or you can think about whether you’ve noticed sugar dissolving more rapidly in your glass of iced tea or in your cup of coffee. Even such basic, outside-the-lab observations can help you justify your hypothesis as reasonable.

Background/previous research

This part of the Introduction demonstrates to the reader your awareness of how you’re building on other scientists’ work. If you think of the scientific community as engaging in a series of conversations about various topics, then you’ll recognize that the relevant background material will alert the reader to which conversation you want to enter.

Generally speaking, authors writing journal articles use the background for slightly different purposes than do students completing assignments. Because readers of academic journals tend to be professionals in the field, authors explain the background in order to permit readers to evaluate the study’s pertinence for their own work. You, on the other hand, write toward a much narrower audience—your peers in the course or your lab instructor—and so you must demonstrate that you understand the context for the (presumably assigned) experiment or study you’ve completed. For example, if your professor has been talking about polarity during lectures, and you’re doing a solubility experiment, you might try to connect the polarity of a solid to its relative solubility in certain solvents. In any event, both professional researchers and undergraduates need to connect the background material overtly to their own work.

Organization of this section

Most of the time, writers begin by stating the purpose or objectives of their own work, which establishes for the reader’s benefit the “nature and scope of the problem investigated” (Day 1994). Once you have expressed your purpose, you should then find it easier to move from the general purpose, to relevant material on the subject, to your hypothesis. In abbreviated form, an Introduction section might look like this:

“The purpose of the experiment was to test conventional ideas about solubility in the laboratory [purpose] . . . According to Whitecoat and Labrat (1999), at higher temperatures the molecules of solvents move more quickly . . . We know from the class lecture that molecules moving at higher rates of speed collide with one another more often and thus break down more easily [background material/motivation] . . . Thus, it was hypothesized that as the temperature of a solvent increases, the rate at which a solute will dissolve in that solvent increases [hypothesis].”

Again—these are guidelines, not commandments. Some writers and readers prefer different structures for the Introduction. The one above merely illustrates a common approach to organizing material.

How do I write a strong Materials and Methods section?

As with any piece of writing, your Methods section will succeed only if it fulfills its readers’ expectations, so you need to be clear in your own mind about the purpose of this section. Let’s review the purpose as we described it above: in this section, you want to describe in detail how you tested the hypothesis you developed and also to clarify the rationale for your procedure. In science, it’s not sufficient merely to design and carry out an experiment. Ultimately, others must be able to verify your findings, so your experiment must be reproducible, to the extent that other researchers can follow the same procedure and obtain the same (or similar) results.

Here’s a real-world example of the importance of reproducibility. In 1989, physicists Stanley Pons and Martin Fleischman announced that they had discovered “cold fusion,” a way of producing excess heat and power without the nuclear radiation that accompanies “hot fusion.” Such a discovery could have great ramifications for the industrial production of energy, so these findings created a great deal of interest. When other scientists tried to duplicate the experiment, however, they didn’t achieve the same results, and as a result many wrote off the conclusions as unjustified (or worse, a hoax). To this day, the viability of cold fusion is debated within the scientific community, even though an increasing number of researchers believe it possible. So when you write your Methods section, keep in mind that you need to describe your experiment well enough to allow others to replicate it exactly.

With these goals in mind, let’s consider how to write an effective Methods section in terms of content, structure, and style.

Sometimes the hardest thing about writing this section isn’t what you should talk about, but what you shouldn’t talk about. Writers often want to include the results of their experiment, because they measured and recorded the results during the course of the experiment. But such data should be reserved for the Results section. In the Methods section, you can write that you recorded the results, or how you recorded the results (e.g., in a table), but you shouldn’t write what the results were—not yet. Here, you’re merely stating exactly how you went about testing your hypothesis. As you draft your Methods section, ask yourself the following questions:

- How much detail? Be precise in providing details, but stay relevant. Ask yourself, “Would it make any difference if this piece were a different size or made from a different material?” If not, you probably don’t need to get too specific. If so, you should give as many details as necessary to prevent this experiment from going awry if someone else tries to carry it out. Probably the most crucial detail is measurement; you should always quantify anything you can, such as time elapsed, temperature, mass, volume, etc.

- Rationale: Be sure that as you’re relating your actions during the experiment, you explain your rationale for the protocol you developed. If you capped a test tube immediately after adding a solute to a solvent, why did you do that? (That’s really two questions: why did you cap it, and why did you cap it immediately?) In a professional setting, writers provide their rationale as a way to explain their thinking to potential critics. On one hand, of course, that’s your motivation for talking about protocol, too. On the other hand, since in practical terms you’re also writing to your teacher (who’s seeking to evaluate how well you comprehend the principles of the experiment), explaining the rationale indicates that you understand the reasons for conducting the experiment in that way, and that you’re not just following orders. Critical thinking is crucial—robots don’t make good scientists.

- Control: Most experiments will include a control, which is a means of comparing experimental results. (Sometimes you’ll need to have more than one control, depending on the number of hypotheses you want to test.) The control is exactly the same as the other items you’re testing, except that you don’t manipulate the independent variable-the condition you’re altering to check the effect on the dependent variable. For example, if you’re testing solubility rates at increased temperatures, your control would be a solution that you didn’t heat at all; that way, you’ll see how quickly the solute dissolves “naturally” (i.e., without manipulation), and you’ll have a point of reference against which to compare the solutions you did heat.

Describe the control in the Methods section. Two things are especially important in writing about the control: identify the control as a control, and explain what you’re controlling for. Here is an example:

“As a control for the temperature change, we placed the same amount of solute in the same amount of solvent, and let the solution stand for five minutes without heating it.”

Structure and style

Organization is especially important in the Methods section of a lab report because readers must understand your experimental procedure completely. Many writers are surprised by the difficulty of conveying what they did during the experiment, since after all they’re only reporting an event, but it’s often tricky to present this information in a coherent way. There’s a fairly standard structure you can use to guide you, and following the conventions for style can help clarify your points.

- Subsections: Occasionally, researchers use subsections to report their procedure when the following circumstances apply: 1) if they’ve used a great many materials; 2) if the procedure is unusually complicated; 3) if they’ve developed a procedure that won’t be familiar to many of their readers. Because these conditions rarely apply to the experiments you’ll perform in class, most undergraduate lab reports won’t require you to use subsections. In fact, many guides to writing lab reports suggest that you try to limit your Methods section to a single paragraph.

- Narrative structure: Think of this section as telling a story about a group of people and the experiment they performed. Describe what you did in the order in which you did it. You may have heard the old joke centered on the line, “Disconnect the red wire, but only after disconnecting the green wire,” where the person reading the directions blows everything to kingdom come because the directions weren’t in order. We’re used to reading about events chronologically, and so your readers will generally understand what you did if you present that information in the same way. Also, since the Methods section does generally appear as a narrative (story), you want to avoid the “recipe” approach: “First, take a clean, dry 100 ml test tube from the rack. Next, add 50 ml of distilled water.” You should be reporting what did happen, not telling the reader how to perform the experiment: “50 ml of distilled water was poured into a clean, dry 100 ml test tube.” Hint: most of the time, the recipe approach comes from copying down the steps of the procedure from your lab manual, so you may want to draft the Methods section initially without consulting your manual. Later, of course, you can go back and fill in any part of the procedure you inadvertently overlooked.

- Past tense: Remember that you’re describing what happened, so you should use past tense to refer to everything you did during the experiment. Writers are often tempted to use the imperative (“Add 5 g of the solid to the solution”) because that’s how their lab manuals are worded; less frequently, they use present tense (“5 g of the solid are added to the solution”). Instead, remember that you’re talking about an event which happened at a particular time in the past, and which has already ended by the time you start writing, so simple past tense will be appropriate in this section (“5 g of the solid were added to the solution” or “We added 5 g of the solid to the solution”).

- Active: We heated the solution to 80°C. (The subject, “we,” performs the action, heating.)

- Passive: The solution was heated to 80°C. (The subject, “solution,” doesn’t do the heating–it is acted upon, not acting.)

Increasingly, especially in the social sciences, using first person and active voice is acceptable in scientific reports. Most readers find that this style of writing conveys information more clearly and concisely. This rhetorical choice thus brings two scientific values into conflict: objectivity versus clarity. Since the scientific community hasn’t reached a consensus about which style it prefers, you may want to ask your lab instructor.

How do I write a strong Results section?

Here’s a paradox for you. The Results section is often both the shortest (yay!) and most important (uh-oh!) part of your report. Your Materials and Methods section shows how you obtained the results, and your Discussion section explores the significance of the results, so clearly the Results section forms the backbone of the lab report. This section provides the most critical information about your experiment: the data that allow you to discuss how your hypothesis was or wasn’t supported. But it doesn’t provide anything else, which explains why this section is generally shorter than the others.

Before you write this section, look at all the data you collected to figure out what relates significantly to your hypothesis. You’ll want to highlight this material in your Results section. Resist the urge to include every bit of data you collected, since perhaps not all are relevant. Also, don’t try to draw conclusions about the results—save them for the Discussion section. In this section, you’re reporting facts. Nothing your readers can dispute should appear in the Results section.

Most Results sections feature three distinct parts: text, tables, and figures. Let’s consider each part one at a time.

This should be a short paragraph, generally just a few lines, that describes the results you obtained from your experiment. In a relatively simple experiment, one that doesn’t produce a lot of data for you to repeat, the text can represent the entire Results section. Don’t feel that you need to include lots of extraneous detail to compensate for a short (but effective) text; your readers appreciate discrimination more than your ability to recite facts. In a more complex experiment, you may want to use tables and/or figures to help guide your readers toward the most important information you gathered. In that event, you’ll need to refer to each table or figure directly, where appropriate:

“Table 1 lists the rates of solubility for each substance”

“Solubility increased as the temperature of the solution increased (see Figure 1).”

If you do use tables or figures, make sure that you don’t present the same material in both the text and the tables/figures, since in essence you’ll just repeat yourself, probably annoying your readers with the redundancy of your statements.

Feel free to describe trends that emerge as you examine the data. Although identifying trends requires some judgment on your part and so may not feel like factual reporting, no one can deny that these trends do exist, and so they properly belong in the Results section. Example:

“Heating the solution increased the rate of solubility of polar solids by 45% but had no effect on the rate of solubility in solutions containing non-polar solids.”

This point isn’t debatable—you’re just pointing out what the data show.

As in the Materials and Methods section, you want to refer to your data in the past tense, because the events you recorded have already occurred and have finished occurring. In the example above, note the use of “increased” and “had,” rather than “increases” and “has.” (You don’t know from your experiment that heating always increases the solubility of polar solids, but it did that time.)

You shouldn’t put information in the table that also appears in the text. You also shouldn’t use a table to present irrelevant data, just to show you did collect these data during the experiment. Tables are good for some purposes and situations, but not others, so whether and how you’ll use tables depends upon what you need them to accomplish.

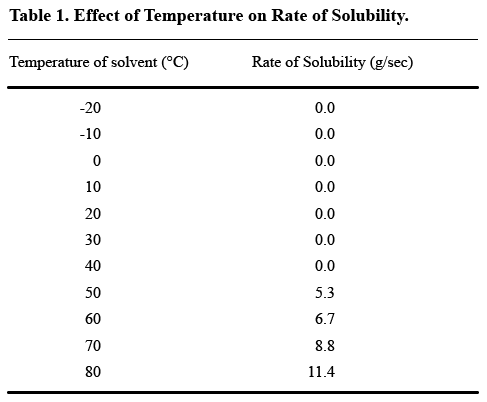

Tables are useful ways to show variation in data, but not to present a great deal of unchanging measurements. If you’re dealing with a scientific phenomenon that occurs only within a certain range of temperatures, for example, you don’t need to use a table to show that the phenomenon didn’t occur at any of the other temperatures. How useful is this table?

As you can probably see, no solubility was observed until the trial temperature reached 50°C, a fact that the text part of the Results section could easily convey. The table could then be limited to what happened at 50°C and higher, thus better illustrating the differences in solubility rates when solubility did occur.

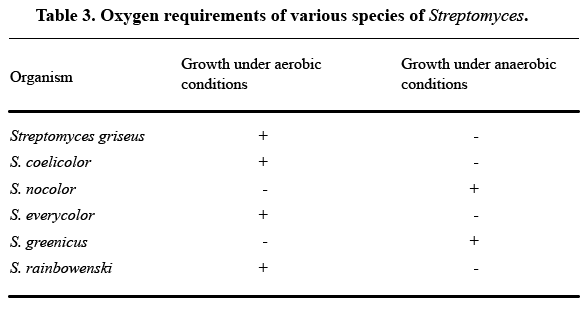

As a rule, try not to use a table to describe any experimental event you can cover in one sentence of text. Here’s an example of an unnecessary table from How to Write and Publish a Scientific Paper , by Robert A. Day:

As Day notes, all the information in this table can be summarized in one sentence: “S. griseus, S. coelicolor, S. everycolor, and S. rainbowenski grew under aerobic conditions, whereas S. nocolor and S. greenicus required anaerobic conditions.” Most readers won’t find the table clearer than that one sentence.

When you do have reason to tabulate material, pay attention to the clarity and readability of the format you use. Here are a few tips:

- Number your table. Then, when you refer to the table in the text, use that number to tell your readers which table they can review to clarify the material.

- Give your table a title. This title should be descriptive enough to communicate the contents of the table, but not so long that it becomes difficult to follow. The titles in the sample tables above are acceptable.

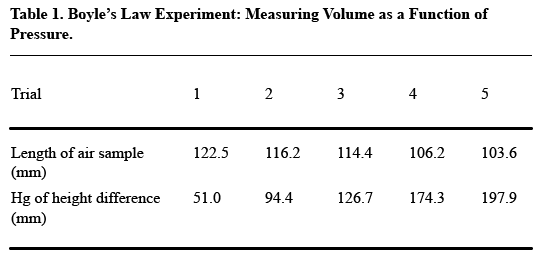

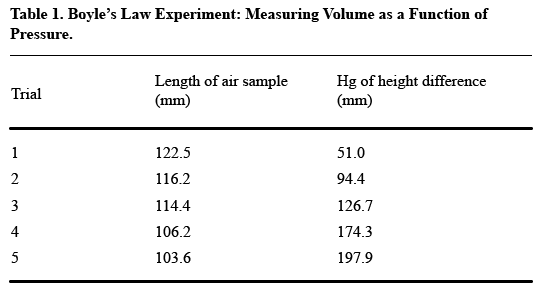

- Arrange your table so that readers read vertically, not horizontally. For the most part, this rule means that you should construct your table so that like elements read down, not across. Think about what you want your readers to compare, and put that information in the column (up and down) rather than in the row (across). Usually, the point of comparison will be the numerical data you collect, so especially make sure you have columns of numbers, not rows.Here’s an example of how drastically this decision affects the readability of your table (from A Short Guide to Writing about Chemistry , by Herbert Beall and John Trimbur). Look at this table, which presents the relevant data in horizontal rows:

It’s a little tough to see the trends that the author presumably wants to present in this table. Compare this table, in which the data appear vertically:

The second table shows how putting like elements in a vertical column makes for easier reading. In this case, the like elements are the measurements of length and height, over five trials–not, as in the first table, the length and height measurements for each trial.

- Make sure to include units of measurement in the tables. Readers might be able to guess that you measured something in millimeters, but don’t make them try.

- Don’t use vertical lines as part of the format for your table. This convention exists because journals prefer not to have to reproduce these lines because the tables then become more expensive to print. Even though it’s fairly unlikely that you’ll be sending your Biology 11 lab report to Science for publication, your readers still have this expectation. Consequently, if you use the table-drawing option in your word-processing software, choose the option that doesn’t rely on a “grid” format (which includes vertical lines).

How do I include figures in my report?

Although tables can be useful ways of showing trends in the results you obtained, figures (i.e., illustrations) can do an even better job of emphasizing such trends. Lab report writers often use graphic representations of the data they collected to provide their readers with a literal picture of how the experiment went.

When should you use a figure?

Remember the circumstances under which you don’t need a table: when you don’t have a great deal of data or when the data you have don’t vary a lot. Under the same conditions, you would probably forgo the figure as well, since the figure would be unlikely to provide your readers with an additional perspective. Scientists really don’t like their time wasted, so they tend not to respond favorably to redundancy.

If you’re trying to decide between using a table and creating a figure to present your material, consider the following a rule of thumb. The strength of a table lies in its ability to supply large amounts of exact data, whereas the strength of a figure is its dramatic illustration of important trends within the experiment. If you feel that your readers won’t get the full impact of the results you obtained just by looking at the numbers, then a figure might be appropriate.

Of course, an undergraduate class may expect you to create a figure for your lab experiment, if only to make sure that you can do so effectively. If this is the case, then don’t worry about whether to use figures or not—concentrate instead on how best to accomplish your task.

Figures can include maps, photographs, pen-and-ink drawings, flow charts, bar graphs, and section graphs (“pie charts”). But the most common figure by far, especially for undergraduates, is the line graph, so we’ll focus on that type in this handout.

At the undergraduate level, you can often draw and label your graphs by hand, provided that the result is clear, legible, and drawn to scale. Computer technology has, however, made creating line graphs a lot easier. Most word-processing software has a number of functions for transferring data into graph form; many scientists have found Microsoft Excel, for example, a helpful tool in graphing results. If you plan on pursuing a career in the sciences, it may be well worth your while to learn to use a similar program.

Computers can’t, however, decide for you how your graph really works; you have to know how to design your graph to meet your readers’ expectations. Here are some of these expectations:

- Keep it as simple as possible. You may be tempted to signal the complexity of the information you gathered by trying to design a graph that accounts for that complexity. But remember the purpose of your graph: to dramatize your results in a manner that’s easy to see and grasp. Try not to make the reader stare at the graph for a half hour to find the important line among the mass of other lines. For maximum effectiveness, limit yourself to three to five lines per graph; if you have more data to demonstrate, use a set of graphs to account for it, rather than trying to cram it all into a single figure.

- Plot the independent variable on the horizontal (x) axis and the dependent variable on the vertical (y) axis. Remember that the independent variable is the condition that you manipulated during the experiment and the dependent variable is the condition that you measured to see if it changed along with the independent variable. Placing the variables along their respective axes is mostly just a convention, but since your readers are accustomed to viewing graphs in this way, you’re better off not challenging the convention in your report.

- Label each axis carefully, and be especially careful to include units of measure. You need to make sure that your readers understand perfectly well what your graph indicates.

- Number and title your graphs. As with tables, the title of the graph should be informative but concise, and you should refer to your graph by number in the text (e.g., “Figure 1 shows the increase in the solubility rate as a function of temperature”).

- Many editors of professional scientific journals prefer that writers distinguish the lines in their graphs by attaching a symbol to them, usually a geometric shape (triangle, square, etc.), and using that symbol throughout the curve of the line. Generally, readers have a hard time distinguishing dotted lines from dot-dash lines from straight lines, so you should consider staying away from this system. Editors don’t usually like different-colored lines within a graph because colors are difficult and expensive to reproduce; colors may, however, be great for your purposes, as long as you’re not planning to submit your paper to Nature. Use your discretion—try to employ whichever technique dramatizes the results most effectively.

- Try to gather data at regular intervals, so the plot points on your graph aren’t too far apart. You can’t be sure of the arc you should draw between the plot points if the points are located at the far corners of the graph; over a fifteen-minute interval, perhaps the change occurred in the first or last thirty seconds of that period (in which case your straight-line connection between the points is misleading).

- If you’re worried that you didn’t collect data at sufficiently regular intervals during your experiment, go ahead and connect the points with a straight line, but you may want to examine this problem as part of your Discussion section.

- Make your graph large enough so that everything is legible and clearly demarcated, but not so large that it either overwhelms the rest of the Results section or provides a far greater range than you need to illustrate your point. If, for example, the seedlings of your plant grew only 15 mm during the trial, you don’t need to construct a graph that accounts for 100 mm of growth. The lines in your graph should more or less fill the space created by the axes; if you see that your data is confined to the lower left portion of the graph, you should probably re-adjust your scale.

- If you create a set of graphs, make them the same size and format, including all the verbal and visual codes (captions, symbols, scale, etc.). You want to be as consistent as possible in your illustrations, so that your readers can easily make the comparisons you’re trying to get them to see.

How do I write a strong Discussion section?

The discussion section is probably the least formalized part of the report, in that you can’t really apply the same structure to every type of experiment. In simple terms, here you tell your readers what to make of the Results you obtained. If you have done the Results part well, your readers should already recognize the trends in the data and have a fairly clear idea of whether your hypothesis was supported. Because the Results can seem so self-explanatory, many students find it difficult to know what material to add in this last section.

Basically, the Discussion contains several parts, in no particular order, but roughly moving from specific (i.e., related to your experiment only) to general (how your findings fit in the larger scientific community). In this section, you will, as a rule, need to:

Explain whether the data support your hypothesis

- Acknowledge any anomalous data or deviations from what you expected

Derive conclusions, based on your findings, about the process you’re studying

- Relate your findings to earlier work in the same area (if you can)

Explore the theoretical and/or practical implications of your findings

Let’s look at some dos and don’ts for each of these objectives.

This statement is usually a good way to begin the Discussion, since you can’t effectively speak about the larger scientific value of your study until you’ve figured out the particulars of this experiment. You might begin this part of the Discussion by explicitly stating the relationships or correlations your data indicate between the independent and dependent variables. Then you can show more clearly why you believe your hypothesis was or was not supported. For example, if you tested solubility at various temperatures, you could start this section by noting that the rates of solubility increased as the temperature increased. If your initial hypothesis surmised that temperature change would not affect solubility, you would then say something like,

“The hypothesis that temperature change would not affect solubility was not supported by the data.”

Note: Students tend to view labs as practical tests of undeniable scientific truths. As a result, you may want to say that the hypothesis was “proved” or “disproved” or that it was “correct” or “incorrect.” These terms, however, reflect a degree of certainty that you as a scientist aren’t supposed to have. Remember, you’re testing a theory with a procedure that lasts only a few hours and relies on only a few trials, which severely compromises your ability to be sure about the “truth” you see. Words like “supported,” “indicated,” and “suggested” are more acceptable ways to evaluate your hypothesis.

Also, recognize that saying whether the data supported your hypothesis or not involves making a claim to be defended. As such, you need to show the readers that this claim is warranted by the evidence. Make sure that you’re very explicit about the relationship between the evidence and the conclusions you draw from it. This process is difficult for many writers because we don’t often justify conclusions in our regular lives. For example, you might nudge your friend at a party and whisper, “That guy’s drunk,” and once your friend lays eyes on the person in question, she might readily agree. In a scientific paper, by contrast, you would need to defend your claim more thoroughly by pointing to data such as slurred words, unsteady gait, and the lampshade-as-hat. In addition to pointing out these details, you would also need to show how (according to previous studies) these signs are consistent with inebriation, especially if they occur in conjunction with one another. To put it another way, tell your readers exactly how you got from point A (was the hypothesis supported?) to point B (yes/no).

Acknowledge any anomalous data, or deviations from what you expected

You need to take these exceptions and divergences into account, so that you qualify your conclusions sufficiently. For obvious reasons, your readers will doubt your authority if you (deliberately or inadvertently) overlook a key piece of data that doesn’t square with your perspective on what occurred. In a more philosophical sense, once you’ve ignored evidence that contradicts your claims, you’ve departed from the scientific method. The urge to “tidy up” the experiment is often strong, but if you give in to it you’re no longer performing good science.

Sometimes after you’ve performed a study or experiment, you realize that some part of the methods you used to test your hypothesis was flawed. In that case, it’s OK to suggest that if you had the chance to conduct your test again, you might change the design in this or that specific way in order to avoid such and such a problem. The key to making this approach work, though, is to be very precise about the weakness in your experiment, why and how you think that weakness might have affected your data, and how you would alter your protocol to eliminate—or limit the effects of—that weakness. Often, inexperienced researchers and writers feel the need to account for “wrong” data (remember, there’s no such animal), and so they speculate wildly about what might have screwed things up. These speculations include such factors as the unusually hot temperature in the room, or the possibility that their lab partners read the meters wrong, or the potentially defective equipment. These explanations are what scientists call “cop-outs,” or “lame”; don’t indicate that the experiment had a weakness unless you’re fairly certain that a) it really occurred and b) you can explain reasonably well how that weakness affected your results.

If, for example, your hypothesis dealt with the changes in solubility at different temperatures, then try to figure out what you can rationally say about the process of solubility more generally. If you’re doing an undergraduate lab, chances are that the lab will connect in some way to the material you’ve been covering either in lecture or in your reading, so you might choose to return to these resources as a way to help you think clearly about the process as a whole.

This part of the Discussion section is another place where you need to make sure that you’re not overreaching. Again, nothing you’ve found in one study would remotely allow you to claim that you now “know” something, or that something isn’t “true,” or that your experiment “confirmed” some principle or other. Hesitate before you go out on a limb—it’s dangerous! Use less absolutely conclusive language, including such words as “suggest,” “indicate,” “correspond,” “possibly,” “challenge,” etc.

Relate your findings to previous work in the field (if possible)

We’ve been talking about how to show that you belong in a particular community (such as biologists or anthropologists) by writing within conventions that they recognize and accept. Another is to try to identify a conversation going on among members of that community, and use your work to contribute to that conversation. In a larger philosophical sense, scientists can’t fully understand the value of their research unless they have some sense of the context that provoked and nourished it. That is, you have to recognize what’s new about your project (potentially, anyway) and how it benefits the wider body of scientific knowledge. On a more pragmatic level, especially for undergraduates, connecting your lab work to previous research will demonstrate to the TA that you see the big picture. You have an opportunity, in the Discussion section, to distinguish yourself from the students in your class who aren’t thinking beyond the barest facts of the study. Capitalize on this opportunity by putting your own work in context.

If you’re just beginning to work in the natural sciences (as a first-year biology or chemistry student, say), most likely the work you’ll be doing has already been performed and re-performed to a satisfactory degree. Hence, you could probably point to a similar experiment or study and compare/contrast your results and conclusions. More advanced work may deal with an issue that is somewhat less “resolved,” and so previous research may take the form of an ongoing debate, and you can use your own work to weigh in on that debate. If, for example, researchers are hotly disputing the value of herbal remedies for the common cold, and the results of your study suggest that Echinacea diminishes the symptoms but not the actual presence of the cold, then you might want to take some time in the Discussion section to recapitulate the specifics of the dispute as it relates to Echinacea as an herbal remedy. (Consider that you have probably already written in the Introduction about this debate as background research.)

This information is often the best way to end your Discussion (and, for all intents and purposes, the report). In argumentative writing generally, you want to use your closing words to convey the main point of your writing. This main point can be primarily theoretical (“Now that you understand this information, you’re in a better position to understand this larger issue”) or primarily practical (“You can use this information to take such and such an action”). In either case, the concluding statements help the reader to comprehend the significance of your project and your decision to write about it.

Since a lab report is argumentative—after all, you’re investigating a claim, and judging the legitimacy of that claim by generating and collecting evidence—it’s often a good idea to end your report with the same technique for establishing your main point. If you want to go the theoretical route, you might talk about the consequences your study has for the field or phenomenon you’re investigating. To return to the examples regarding solubility, you could end by reflecting on what your work on solubility as a function of temperature tells us (potentially) about solubility in general. (Some folks consider this type of exploration “pure” as opposed to “applied” science, although these labels can be problematic.) If you want to go the practical route, you could end by speculating about the medical, institutional, or commercial implications of your findings—in other words, answer the question, “What can this study help people to do?” In either case, you’re going to make your readers’ experience more satisfying, by helping them see why they spent their time learning what you had to teach them.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

American Psychological Association. 2010. Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association . 6th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Beall, Herbert, and John Trimbur. 2001. A Short Guide to Writing About Chemistry , 2nd ed. New York: Longman.

Blum, Deborah, and Mary Knudson. 1997. A Field Guide for Science Writers: The Official Guide of the National Association of Science Writers . New York: Oxford University Press.

Booth, Wayne C., Gregory G. Colomb, Joseph M. Williams, Joseph Bizup, and William T. FitzGerald. 2016. The Craft of Research , 4th ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Briscoe, Mary Helen. 1996. Preparing Scientific Illustrations: A Guide to Better Posters, Presentations, and Publications , 2nd ed. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Council of Science Editors. 2014. Scientific Style and Format: The CSE Manual for Authors, Editors, and Publishers , 8th ed. Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press.

Davis, Martha. 2012. Scientific Papers and Presentations , 3rd ed. London: Academic Press.

Day, Robert A. 1994. How to Write and Publish a Scientific Paper , 4th ed. Phoenix: Oryx Press.

Porush, David. 1995. A Short Guide to Writing About Science . New York: Longman.

Williams, Joseph, and Joseph Bizup. 2017. Style: Lessons in Clarity and Grace , 12th ed. Boston: Pearson.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

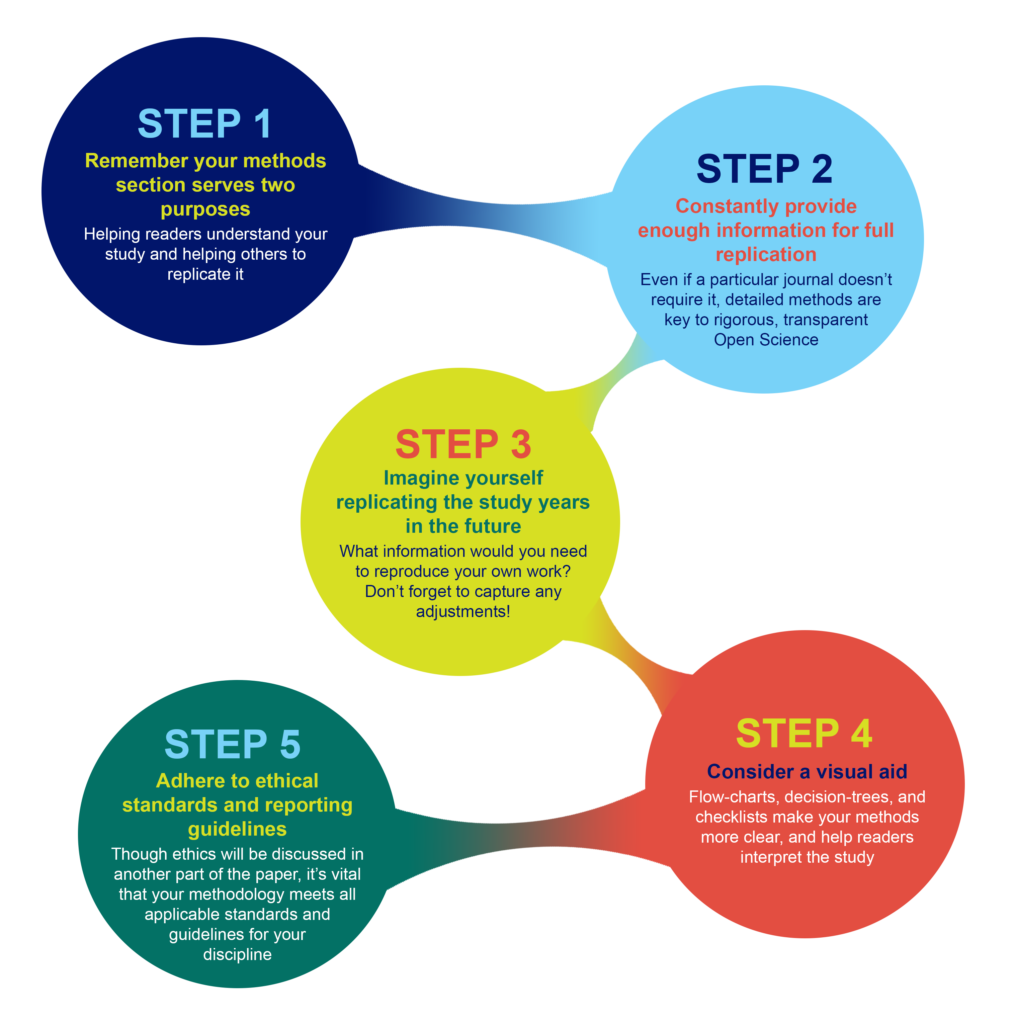

- How to Write Your Methods

Ensure understanding, reproducibility and replicability

What should you include in your methods section, and how much detail is appropriate?

Why Methods Matter

The methods section was once the most likely part of a paper to be unfairly abbreviated, overly summarized, or even relegated to hard-to-find sections of a publisher’s website. While some journals may responsibly include more detailed elements of methods in supplementary sections, the movement for increased reproducibility and rigor in science has reinstated the importance of the methods section. Methods are now viewed as a key element in establishing the credibility of the research being reported, alongside the open availability of data and results.

A clear methods section impacts editorial evaluation and readers’ understanding, and is also the backbone of transparency and replicability.

For example, the Reproducibility Project: Cancer Biology project set out in 2013 to replicate experiments from 50 high profile cancer papers, but revised their target to 18 papers once they understood how much methodological detail was not contained in the original papers.

What to include in your methods section

What you include in your methods sections depends on what field you are in and what experiments you are performing. However, the general principle in place at the majority of journals is summarized well by the guidelines at PLOS ONE : “The Materials and Methods section should provide enough detail to allow suitably skilled investigators to fully replicate your study. ” The emphases here are deliberate: the methods should enable readers to understand your paper, and replicate your study. However, there is no need to go into the level of detail that a lay-person would require—the focus is on the reader who is also trained in your field, with the suitable skills and knowledge to attempt a replication.

A constant principle of rigorous science

A methods section that enables other researchers to understand and replicate your results is a constant principle of rigorous, transparent, and Open Science. Aim to be thorough, even if a particular journal doesn’t require the same level of detail . Reproducibility is all of our responsibility. You cannot create any problems by exceeding a minimum standard of information. If a journal still has word-limits—either for the overall article or specific sections—and requires some methodological details to be in a supplemental section, that is OK as long as the extra details are searchable and findable .

Imagine replicating your own work, years in the future

As part of PLOS’ presentation on Reproducibility and Open Publishing (part of UCSF’s Reproducibility Series ) we recommend planning the level of detail in your methods section by imagining you are writing for your future self, replicating your own work. When you consider that you might be at a different institution, with different account logins, applications, resources, and access levels—you can help yourself imagine the level of specificity that you yourself would require to redo the exact experiment. Consider:

- Which details would you need to be reminded of?

- Which cell line, or antibody, or software, or reagent did you use, and does it have a Research Resource ID (RRID) that you can cite?

- Which version of a questionnaire did you use in your survey?

- Exactly which visual stimulus did you show participants, and is it publicly available?

- What participants did you decide to exclude?

- What process did you adjust, during your work?

Tip: Be sure to capture any changes to your protocols

You yourself would want to know about any adjustments, if you ever replicate the work, so you can surmise that anyone else would want to as well. Even if a necessary adjustment you made was not ideal, transparency is the key to ensuring this is not regarded as an issue in the future. It is far better to transparently convey any non-optimal methods, or methodological constraints, than to conceal them, which could result in reproducibility or ethical issues downstream.

Visual aids for methods help when reading the whole paper

Consider whether a visual representation of your methods could be appropriate or aid understanding your process. A visual reference readers can easily return to, like a flow-diagram, decision-tree, or checklist, can help readers to better understand the complete article, not just the methods section.

Ethical Considerations

In addition to describing what you did, it is just as important to assure readers that you also followed all relevant ethical guidelines when conducting your research. While ethical standards and reporting guidelines are often presented in a separate section of a paper, ensure that your methods and protocols actually follow these guidelines. Read more about ethics .

Existing standards, checklists, guidelines, partners

While the level of detail contained in a methods section should be guided by the universal principles of rigorous science outlined above, various disciplines, fields, and projects have worked hard to design and develop consistent standards, guidelines, and tools to help with reporting all types of experiment. Below, you’ll find some of the key initiatives. Ensure you read the submission guidelines for the specific journal you are submitting to, in order to discover any further journal- or field-specific policies to follow, or initiatives/tools to utilize.

Tip: Keep your paper moving forward by providing the proper paperwork up front

Be sure to check the journal guidelines and provide the necessary documents with your manuscript submission. Collecting the necessary documentation can greatly slow the first round of peer review, or cause delays when you submit your revision.

Randomized Controlled Trials – CONSORT The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) project covers various initiatives intended to prevent the problems of inadequate reporting of randomized controlled trials. The primary initiative is an evidence-based minimum set of recommendations for reporting randomized trials known as the CONSORT Statement .

Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses – PRISMA The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses ( PRISMA ) is an evidence-based minimum set of items focusing on the reporting of reviews evaluating randomized trials and other types of research.

Research using Animals – ARRIVE The Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments ( ARRIVE ) guidelines encourage maximizing the information reported in research using animals thereby minimizing unnecessary studies. (Original study and proposal , and updated guidelines , in PLOS Biology .)

Laboratory Protocols Protocols.io has developed a platform specifically for the sharing and updating of laboratory protocols , which are assigned their own DOI and can be linked from methods sections of papers to enhance reproducibility. Contextualize your protocol and improve discovery with an accompanying Lab Protocol article in PLOS ONE .

Consistent reporting of Materials, Design, and Analysis – the MDAR checklist A cross-publisher group of editors and experts have developed, tested, and rolled out a checklist to help establish and harmonize reporting standards in the Life Sciences . The checklist , which is available for use by authors to compile their methods, and editors/reviewers to check methods, establishes a minimum set of requirements in transparent reporting and is adaptable to any discipline within the Life Sciences, by covering a breadth of potentially relevant methodological items and considerations. If you are in the Life Sciences and writing up your methods section, try working through the MDAR checklist and see whether it helps you include all relevant details into your methods, and whether it reminded you of anything you might have missed otherwise.

Summary Writing tips

The main challenge you may find when writing your methods is keeping it readable AND covering all the details needed for reproducibility and replicability. While this is difficult, do not compromise on rigorous standards for credibility!

- Keep in mind future replicability, alongside understanding and readability.

- Follow checklists, and field- and journal-specific guidelines.

- Consider a commitment to rigorous and transparent science a personal responsibility, and not just adhering to journal guidelines.

- Establish whether there are persistent identifiers for any research resources you use that can be specifically cited in your methods section.

- Deposit your laboratory protocols in Protocols.io, establishing a permanent link to them. You can update your protocols later if you improve on them, as can future scientists who follow your protocols.

- Consider visual aids like flow-diagrams, lists, to help with reading other sections of the paper.

- Be specific about all decisions made during the experiments that someone reproducing your work would need to know.

Don’t

- Summarize or abbreviate methods without giving full details in a discoverable supplemental section.

- Presume you will always be able to remember how you performed the experiments, or have access to private or institutional notebooks and resources.

- Attempt to hide constraints or non-optimal decisions you had to make–transparency is the key to ensuring the credibility of your research.

- How to Write a Great Title

- How to Write an Abstract

- How to Report Statistics

- How to Write Discussions and Conclusions

- How to Edit Your Work

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

- Langson Library

- Science Library

- Grunigen Medical Library

- Law Library

- Connect From Off-Campus

- Accessibility

- Gateway Study Center

Email this link

Writing a scientific paper.

- Writing a lab report

- INTRODUCTION

Writing a "good" methods section

"methods checklist" from: how to write a good scientific paper. chris a. mack. spie. 2018..

- LITERATURE CITED

- Bibliography of guides to scientific writing and presenting

- Peer Review

- Presentations

- Lab Report Writing Guides on the Web