- MyU : For Students, Faculty, and Staff

Who was Charles Babbage?

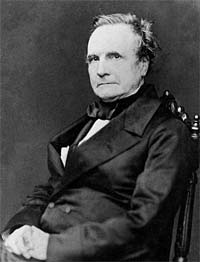

The calculating engines of English mathematician Charles Babbage (1791-1871) are among the most celebrated icons in the prehistory of computing. Babbage’s Difference Engine No.1 was the first successful automatic calculator and remains one of the finest examples of precision engineering of the time. Babbage is sometimes referred to as "father of computing." The International Charles Babbage Society (later the Charles Babbage Institute) took his name to honor his intellectual contributions and their relation to modern computers.

Charles Babbage was born on December 26, 1791, the son of Benjamin Babbage, a London banker. As a youth Babbage was his own instructor in algebra, of which he was passionately fond, and was well read in the continental mathematics of his day. Upon entering Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1811, he found himself far in advance of his tutors in mathematics. Babbage co-founded the Analytical Society for promoting continental mathematics and reforming the mathematics of Newton then taught at the university.

In his twenties Babbage worked as a mathematician, principally in the calculus of functions. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1816 and played a prominent part in the foundation of the Astronomical Society (later Royal Astronomical Society) in 1820. It was about this time that Babbage first acquired the interest in calculating machinery that became his consuming passion for the remainder of his life.

In 1821 Babbage invented the Difference Engine to compile mathematical tables. On completing it in 1832, he conceived the idea of a better machine that could perform not just one mathematical task but any kind of calculation. This was the Analytical Engine (1856), which was intended as a general symbol manipulator, and had some of the characteristics of today’s computers.

Unfortunately, little remains of Babbage's prototype computing machines. Critical tolerances required by his machines exceeded the level of technology available at the time. And, though Babbage’s work was formally recognized by respected scientific institutions, the British government suspended funding for his Difference Engine in 1832, and after an agonizing waiting period, ended the project in 1842. There remain only fragments of Babbage's prototype Difference Engine, and though he devoted most of his time and large fortune towards construction of his Analytical Engine after 1856, he never succeeded in completing any of his several designs for it. George Scheutz, a Swedish printer, successfully constructed a machine based on the designs for Babbage's Difference Engine in 1854. This machine printed mathematical, astronomical and actuarial tables with unprecedented accuracy, and was used by the British and American governments. Though Babbage's work was continued by his son, Henry Prevost Babbage, after his death in 1871, the Analytical Engine was never successfully completed, and ran only a few "programs" with embarrassingly obvious errors.

Babbage occupied the Lucasian chair of mathematics at Cambridge from 1828 to 1839. He played an important role in the establishment of the Association for the Advancement of Science and the Statistical Society (later Royal Statistical Society). He also attempted to reform the scientific organizations of the period while calling upon government and society to give more money and prestige to scientific endeavor. Throughout his life Babbage worked in many intellectual fields typical of his day, and made contributions that would have assured his fame irrespective of the Difference and Analytical Engines.

Despite his many achievements, the failure to construct his calculating machines, and in particular the failure of the government to support his work, left Babbage in his declining years a disappointed and embittered man. He died at his home in London on October 18, 1871.

Learn more about Charles Babbage

+ manuscript materials and exhibits.

- CBI holds a microfilmed copy of the Papers of Charles Babbage. The original papers are in the British Library .

- The University of Auckland, New Zealand , also has some of Babbage’s materials. CBI has photocopies of their holdings and the inventory to these copies, as well as other Charles Babbage materials held in the Charles Babbage Collection (CBI 54)

- The Science Museum in London constructed Babbage's Difference Engine No. 2 in 1991. The Science Museum Library and Archives in Wroughton holds the most comprehensive set of original manuscripts and design drawings.

+ CHARLES BABBAGE’S PUBLISHED WORKS

- A Comparative View of the Various Institutions for the Assurance of Lives (1826)

- Table of Logarithms of the Natural Numbers from 1 to 108,000 (1827)

- Reflections on the Decline of Science in England (1830)

- On the Economy of Machinery and Manufactures (1832)

- Ninth Bridgewater Treatise (1837)

- Passages from the Life of a Philosopher (1864)

+ PUBLICATIONS ABOUT CHARLES BABBAGE

- Charles Babbage. Passages from the Life of a Philosopher . (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, Piscataway, NJ, 1994)

- Babbage, Henry Prevost . Babbage's Calculating Engines: A Collection of Papers . (Los Angeles: Tomash, 1982) Charles Babbage Institute Reprint Series, vol. 2.

- Bromley, Allan G. "The Evolution of Babbage's Calculating Engines " Annals of the History of Computing , 9 (1987): 113-136.

- Buxton, H. W. Memoir of the Life and Labours of the Late Charles Babbage Esq ., F.R.S. (Cambridge, MA.: MIT Press, 1988) Charles Babbage Institute Reprint Series, vol. 13.

- Cambell-Kelly, Martin (ed.) The Works of Charles Babbage (11 vols.) (New York: New York University Press, 1989)

- Dubbey, John Michael. Mathematical Work of Charles Babbage . (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 1978)

- Hyman, Anthony. Charles Babbage: Pioneer of the Computer . (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1983)

- Moseley, Maboth. Irascible Genius: a Life of Charles Babbage, Inventor . (London: Hutchinson, 1964)

- Randell, Brian. "From Analytical Engine to Electronic Digital Computer: The Contributions of Ludgate, Torres, and Bush" Annals of the History of Computing , 4 (October 1982): 327.

- Swade, Doron. Charles Babbage and his Calculating Engines . (London: Science Museum, 1991)

- Swade, Doron. The Cogwheel Brain: Charles Babbage and the Quest to build the first Computer . (London: Little, Brown, 2001)

- Van Sinderen, Alfred W. "The Printed Papers of Charles Babbage" Annals of the History of Computing , 2 (April 1980); 169-185.

+ PUBLICATIONS ON BABBAGE AND ADA LOVELACE

- Huskey, Velma R., and Harry D. Huskey. "Lady Lovelace and Charles Babbage" Annals of the History of Computing 2 (October 1980): 299-329.

- Stein, Dorothy. Ada: A Life and A Legacy . (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1985)

- Toole, B.A. "Ada Byron, Lady Lovelace, an analyst and metaphysician." Annals of the History of Computing 18 #3 (Fall 1996): 4-12.

- Fuegi, John, and Jo Francis. "Lovelace & Babbage and the creation of the 1843 'notes'." Annals of the History of Computing 25 #4 (Oct-Dec 2003): 16-26.

- Wikipedia entry on Ada Lovelace .

- Future undergraduate students

- Future transfer students

- Future graduate students

- Future international students

- Diversity and Inclusion Opportunities

- Learn abroad

- Living Learning Communities

- Mentor programs

- Programs for women

- Student groups

- Visit, Apply & Next Steps

- Information for current students

- Departments and majors overview

- Departments

- Undergraduate majors

- Graduate programs

- Integrated Degree Programs

- Additional degree-granting programs

- Online learning

- Academic Advising overview

- Academic Advising FAQ

- Academic Advising Blog

- Appointments and drop-ins

- Academic support

- Commencement

- Four-year plans

- Honors advising

- Policies, procedures, and forms

- Career Services overview

- Resumes and cover letters

- Jobs and internships

- Interviews and job offers

- CSE Career Fair

- Major and career exploration

- Graduate school

- Collegiate Life overview

- Scholarships

- Diversity & Inclusivity Alliance

- Anderson Student Innovation Labs

- Information for alumni

- Get engaged with CSE

- Upcoming events

- CSE Alumni Society Board

- Alumni volunteer interest form

- Golden Medallion Society Reunion

- 50-Year Reunion

- Alumni honors and awards

- Outstanding Achievement

- Alumni Service

- Distinguished Leadership

- Honorary Doctorate Degrees

- Nobel Laureates

- Alumni resources

- Alumni career resources

- Alumni news outlets

- CSE branded clothing

- International alumni resources

- Inventing Tomorrow magazine

- Update your info

- CSE giving overview

- Why give to CSE?

- College priorities

- Give online now

- External relations

- Giving priorities

- CSE Dean's Club

- Donor stories

- Impact of giving

- Ways to give to CSE

- Matching gifts

- CSE directories

- Invest in your company and the future

- Recruit our students

- Connect with researchers

- K-12 initiatives

- Diversity initiatives

- Research news

- Give to CSE

- CSE priorities

- Corporate relations

- Information for faculty and staff

- Administrative offices overview

- Office of the Dean

- Academic affairs

- Finance and Operations

- Communications

- Human resources

- Undergraduate programs and student services

- CSE Committees

- CSE policies overview

- Academic policies

- Faculty hiring and tenure policies

- Finance policies and information

- Graduate education policies

- Human resources policies

- Research policies

- Research overview

- Research centers and facilities

- Research proposal submission process

- Research safety

- Award-winning CSE faculty

- National academies

- University awards

- Honorary professorships

- Collegiate awards

- Other CSE honors and awards

- Staff awards

- Performance Management Process

- Work. With Flexibility in CSE

- K-12 outreach overview

- Summer camps

- Outreach events

- Enrichment programs

- Field trips and tours

- CSE K-12 Virtual Classroom Resources

- Educator development

- Sponsor an event

- Collectibles

Charles Babbage: The Pioneering Father of Computing

- by history tools

- November 19, 2023

Imagine a time without computers. Today, we take for granted how these revolutionary machines have transformed everything from science to business and commerce. But their origins can be traced back to the pioneering work of a 19th century English mathematician and inventor named Charles Babbage. Often called the "father of computing", his ingenious mechanical computers were the first automatic calculation machines – the precursors to modern electronic digital computers that you and I rely on today.

Babbage overcame many challenges during his lifetime to design and build devices that were far ahead of his time. Powered by steam, his complex Analytical Engine contained many key elements of a real programmable computer. From his earliest Difference Engine to handle polynomial equations to the multifunctional Analytical Engine capable of any arithmetical operation, Babbage planted the seeds that blossomed into the age of computing.

Let‘s take a closer look at the remarkable life and inventions of the trailblazing innovator who helped launch the computer revolution.

Overcoming Adversity in Early Life

Born in 1791 in London, England, Charles Babbage grew up in a life of privilege as the son of a wealthy banker. Tragically, his father passed away when Charles was just eight years old, causing the family to spiral into financial hardship. As a child, Babbage disliked his classical schooling, preferring to tinker with tools instead of studying Latin and Greek.

After his father‘s death, Babbage transferred to a country academy. There, he suffered cruelty from older boys who would beat him for sporting his typically fancy clothes. Overcoming these early challenges instilled in Babbage a grit and resilience that served him well as an innovator later in life.

In 1810, Babbage enrolled at Trinity College, Cambridge. Though he did not excel academically, he soaked up new ideas, co-founding a society to introduce modern algebra to England. After graduating in 1814, he lectured at the Royal Institution on astronomy and mathematics. By age 25, Babbage was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society, hinting at the greatness to come.

Conceiving the Difference Engine

As a mathematician, Babbage was frustrated by the time-consuming process of generating mathematical tables by hand calculation. Such tables were critical for navigation, science, and engineering, but mistakes often crept in during manual preparation.

In 1822, Babbage proposed a steam-powered calculating machine called the Difference Engine to automatically tabulate polynomial functions. This prototype mechanical computer aimed to calculate using the method of finite differences, avoiding human error in tables used for vital fields like shipbuilding and railways.

The British government initially funded development of the project but later withdrew support. While the unfinished Difference Engine proved too complex to build with available manufacturing methods, it cemented Babbage‘s vision for calculating machines.

The Revolutionary Analytical Engine

Undeterred by the setback, Babbage worked tirelessly to refine his designs throughout the 1820s and 1830s. By 1834, he conceived his most revolutionary invention – the Analytical Engine.

This machine represented a giant leap forward, incorporating major innovations like:

- Sequential program control – Allowing automated, sequential operations controlled by a "store" of data and instructions

- Memory storage – Thousands of numbers could be held in the Engine‘s "store"

- Arithmetical unit – To perform calculations

- Punch cards – For inputting instructions and data

The Analytical Engine was essentially a general purpose, fully programmable mechanical computer. Its design contained the key elements of a real modern computer as you know it – input, memory, processor, and output.

Table: Comparing the Difference and Analytical Engines

Unfortunately, fabrication of the elaborate Analytical Engine also proved beyond 19th century engineering capabilities. But the blueprint was complete for the first general purpose computer.

Partnership with Ada Lovelace – Programming Pioneer

Babbage collaborated with an unlikely partner in pioneering computer programming – Ada Lovelace, daughter of famous poet Lord Byron. Lovelace took keen interest in Babbage‘s Engines. In 1842, she translated an Italian mathematician‘s paper on the Analytical Engine into English.

Lovelace‘s translation contained extensive, original notes detailing how codes could symbolically represent more than just numbers. She described how the machine could compose music, produce graphics, and complete many tasks beyond calculation. Her notes included the first published computer program – an algorithm for the Analytical Engine to calculate Bernoulli numbers.

Though the Analytical Engine was never built, Lovelace correctly predicted its potential impact, writing:

"[The Analytical Engine] weaves algebraic patterns just as the Jacquard loom weaves flowers and leaves."

This genius woman mathematician was history‘s first computer programmer – and a fitting partner to Babbage in ushering in modern computing.

Lasting Legacy as Computing Pioneer

Frustrated at being unable to build his wondrous Engines, Charles Babbage died in 1871 in London, never gaining the wealth or acclaim he deserved during his lifetime. But future generations would come to appreciate his genius.

Babbage‘s mechanical computer designs were visionary – conceived at a time when electricity itself was still in its infancy. The concepts he introduced predated electronics by over a century: automatic, programmed computation with memory storage. These breakthroughs provided the conceptual blueprint for modern programmable computers.

In the 1990s, London‘s Science Museum successfully built a working Difference Engine based on Babbage‘s designs, vindicating his mechanical computing concepts. While he did not invent the first complete digital computer, Charles Babbage‘s pioneering work earned him rightful status as the "father of computing" – lighting the spark that led to today‘s computer revolution.

Related posts:

- Peter Thiel: The Visionary Silicon Valley Billionaire

- John Patterson — Complete Biography, History and Inventions

- Hello There! Let‘s Explore How Jabez Burns‘ Addometer Paved the Way for Modern Computing

- Percy Ludgate – Complete Biography, History, and Inventions

- Samuel Kelso: Complete Biography, History, and Inventions

- Elizur Wright: The Father of Life Insurance Reform

- Friedrich Kaufmann and the Trumpet Player: A Complete History

- The Innovative Journey of YouTube Co-Founder Chad Hurley

The First Computer

Charles Babbage's Analytical Engine

Mrjohncummings/Wikimedia Commons/CC ASA 2.0G

- European History Figures & Events

- Wars & Battles

- The Holocaust

- European Revolutions

- Industry and Agriculture History in Europe

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

- M.A., Medieval Studies, Sheffield University

- B.A., Medieval Studies, Sheffield University

The modern computer was born out of the urgent necessity after the Second World War to face the challenge of Nazism through innovation. But the first iteration of the computer as we now understand it came much earlier when, in the 1830s, an inventor named Charles Babbage designed a device called the Analytical Engine.

Who Was Charles Babbage?

Born in 1791 to an English banker and his wife, Charles Babbage (1791–1871) became fascinated by math at an early age, teaching himself algebra and reading widely on continental mathematics. When in 1811, he went to Cambridge to study, he discovered that his tutors were deficient in the new mathematical landscape, and that, in fact, he already knew more than they did. As a result, he took off on his own to found the Analytical Society in 1812, which would help transform the field of math in Britain. He became a Royal Society member in 1816 and was a co-founder of several other societies. At one stage he was Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at Cambridge, although he resigned this to work on his engines. An inventor, he was at the forefront of British technology and helped create Britain’s modern postal service, a cowcatcher for trains, and other tools.

The Difference Engine

Babbage was a founding member of Britain’s Royal Astronomical Society, and he soon saw opportunities for innovation in this field. Astronomers had to make lengthy, difficult, and time-consuming calculations that could be riddled with errors. When these tables were being used in high stakes situations, such as for navigation logarithms, the errors could prove fatal. In response, Babbage hoped to create an automatic device that would produce flawless tables. In 1822, he wrote to the Society’s president, Sir Humphry Davy (1778–1829), to express this hope. He followed this up with a paper, on the "Theoretical Principles of Machinery for Calculating Tables," which won the first Society gold medal in 1823. Babbage had decided to try and build a "Difference Engine."

When Babbage approached the British government for funding, they gave him what was one of the globe’s first government grants for technology. Babbage spent this money to hire one of the best machinists he could find to make the parts: Joseph Clement (1779–1844). And there would be a lot of parts: 25,000 were planned.

In 1830, Babbage decided to relocate, creating a workshop that was immune to fire in an area that was free from dust on his own property. Construction ceased in 1833, when Clement refused to continue without advance payment. However, Babbage was not a politician; he lacked the ability to smooth relationships with successive governments, and, instead, alienated people with his impatient demeanor. By this time the government had spent £17,500, no more was coming, and Babbage had only one-seventh of the calculating unit finished. But even in this reduced and nearly hopeless state, the machine was at the cutting edge of world technology.

Difference Engine #2

Babbage wasn't going to give up so quickly. In a world where calculations were usually carried to no more than six figures, Babbage aimed to produce over 20, and the resulting Engine 2 would only need 8,000 parts. His Difference Engine used decimal figures (0–9)—rather than the binary ‘bits’ that Germany’s Gottfried von Leibniz (1646–1716) preferred—and they would be set out on cogs/wheels that interlinked to build up calculations. But the Engine was designed to do more than mimic an abacus: it could operate on complex problems using a series of calculations and could store results within itself for later use, as well as stamp the result onto a metal output. Although it could still only run one operation at once, it was far beyond any other computing device the world had ever seen. Unfortunately for Babbage, he never finished the Difference Engine. Without any further government grants, his funding ran out.

In 1854, a Swedish printer called George Scheutz (1785–1873) used Babbage’s ideas to create a functioning machine that did produce tables of great accuracy. However, they had omitted security features and it tended to break down, and, consequently, the machine failed to make an impact. In 1991, researchers at the London’s Science Museum, where Babbage's records and trials kept, created a Difference Engine 2 to the original design after six years of work. DE2 used around 4,000 parts and weighed just over three tons. The matching printer was completed in 2000, and had as many parts again, although a slightly smaller weight of 2.5 tons. More importantly, it worked.

The Analytical Engine

During his lifetime, Babbage was accused of being more interested in the theory and cutting edge of innovation than actually producing the tables the government was paying him to create. This wasn’t exactly unfair, because by the time the funding for the Difference Engine had evaporated, Babbage had come up with a new idea: the Analytical Engine. This was a massive step beyond the Difference Engine: it was a general-purpose device that could compute many different problems. It was to be digital, automatic, mechanical, and controlled by variable programs. In short, it would solve any calculation you wished. It would be the first computer.

The Analytical Engine had four parts:

- A mill, which was the section that did the calculations (essentially the CPU)

- The store, where the information was kept recorded (essentially the memory)

- The reader, which would allow data to be entered using punched cards (essentially the keyboard)

- The printer

The punch cards were modeled on those developed for the Jacquard loom and would allow the machine a greater flexibility than anything ever invented to do calculations. Babbage had grand ambitions for the device, and the store was supposed to hold 1,050 digit numbers. It would have a built-in ability to weigh up data and process instructions out of order if necessary. It would be steam-driven, made of brass, and require a trained operator/driver.

Babbage was aided by Ada Lovelace (1815–1852), daughter of the British poet Lord Byron and one of the few women of the era with an education in mathematics. Babbage greatly admired her published translation of a French article on Babbage's work, which included her voluminous notes.

The Engine was beyond what Babbage could afford and maybe what technology could then produce, but the government had grown exasperated with Babbage and funding was not forthcoming. Babbage continued to work on the project until he died in 1871, by many accounts an embittered man who felt more public funds should be directed towards the advancement of science. It might not have been finished, but the Analytical Engine was a breakthrough in imagination, if not practicality. Babbage’s engines were forgotten, and supporters had to struggle to keep him well regarded; some members of the press found it easier to mock. When computers were invented in the twentieth century, the inventors did not use Babbage’s plans or ideas, and it was only in the seventies that his work was fully understood.

Computers Today

It took over a century, but modern computers have exceeded the power of the Analytical Engine. Now experts have created a program that replicates the abilities of the Engine , so you can try it yourself .

Sources and Further Reading

- Bromley, A. G. " Charles Babbage's Analytical Engine, 1838 ." Annals of the History of Computing 4.3 (1982): 196–217.

- Cook, Simon. " Minds, Machines and Economic Agents: Cambridge Receptions of Boole and Babbage ." Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A 36.2 (2005): 331–50.

- Crowley, Mary L. " The "Difference" in Babbage's Difference Engine ." The Mathematics Teacher 78.5 (1985): 366–54.

- Hyman, Anthony. "Charles Babbage, Pioneer of the Computer." Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982.

- Lindgren, Michael. "Glory and Failure: The Difference Engines of Johann Müller, Charles Babbage, and Georg and Edvard Scheutz." Trans. McKay, Craig G. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1990.

- History's 15 Most Famous Inventors

- Biography of Charles Babbage, Mathematician and Computer Pioneer

- The History of Computers

- Biography of Ada Lovelace

- Biography of Ada Lovelace, First Computer Programmer

- Biography of Konrad Zuse, Inventor and Programmer of Early Computers

- The Atanasoff-Berry Computer: The First Electronic Computer

- The History of Computer Peripherals: From the Floppy Disk to CDs

- The IBM 701

- History of Computer Memory

- The History of the ENIAC Computer

- Timeline of IBM History

- The History of the Computer Keyboard

- Biography of Mark Dean, Computer Pioneer

- Important Innovations and Inventions, Past and Present

- The History of Ethernet

BROUGHT TO YOU BY

- Applications

- Computer Science

- Data Science Icons

- Machine Learning

- Mathematics

Charles Babbage, The Father of the Computer

Charles babbage (1791–1871) was an english mathematician and inventor. he is credited with designing the first digital automatic computer, which contained all the essential concepts found in the ones we use today..

Born in London, Charles Babbage studied at Trinity College Cambridge — although he had already taught himself many aspects of contemporary mathematics. It was during this time that he first had the idea of mechanically calculating mathematical tables. In 1823, he obtained government support to design a projected machine, the Difference Engine, with a 20-decimal capacity. Like modern computers, it could store data for later processing. Charles began developing the mechanical engineering techniques while serving as Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge. However, the full room-sized engine was never built as the metalworking techniques of the era were not precise enough and too costly.

“Errors using inadequate data are much less than those using no data at all.”

Brilliant Ideas Before Their Time

By the mid-1830s, Charles was already preparing plans for an improved and more complex design: the Analytical Engine, the precursor of the modern digital computer. He envisaged that it would be capable of performing any arithmetical operation based on instructions from punched cards, a memory unit to store numbers, sequential control, and many other basics found in present-day computers. The project was far more advanced than anything that had ever been built before — with a memory unit large enough to hold 1,000 50-digit numbers. It was intended to be steam-driven and run by one attendant. In 1843, Charles Babbage’s friend mathematician Ada Lovelace published a paper explaining how the engine could perform a sequence of calculations. The first computer program was born.

The Analytical Engine, however, was never completed. The ambitious design was, once again, difficult to implement with the technology that existed in the 19th century. In 1991, British scientists built the Difference Engine No. 2 — accurate to 31 digits — to Charles’ specifications. Their success indicates that his idea would have worked. In 2000, the printer for the Difference Engine was also built.

In addition to inventing early computer concepts, Charles Babbage also helped establish the modern postal system in England and compiled the first reliable actuarial tables. He invented a speedometer, as well as the train cow-catcher to deflect obstacles on the track.

Learning From Europe

Charles Babbage helps found the Analytical Society to introduce mathematical developments from Europe to England.

Early Recognition

Charles Babbage is elected a fellow of the Royal Society of London. He also plays a key role in founding the Royal Astronomical (1820) and Statistical (1834) Societies.

Industrial Insights

Charles Babbage publishes “On the Economy of Machinery and Manufactures,” which explores the organization of industrial production. The book sells well and goes to a fourth edition.

Discover more articles

John forbes nash jr., the mathematics genius, bell labs: the idea factory, karen spärck jones: the search engineer enabler, your inbox will love data science.

Charles Babbage

Born: December 26, 1791, in Teignmouth, Devonshire, UK- died 1871, London; known to some as the "Father of Computing" for his contributions to the basic design of the computer through his Analytical Engine. His previous Difference Engine was a special purpose device intended for the production of tables. While he did produce prototypes of portions of the Difference Engine, it was left to Georg and Edvard Schuetz to construct the first working devices to the same design, which were successful in limited applications.

Significant Events in His Life: 1791, born; 1810, entered Trinity College, Cambridge; 1814, graduated Peterhouse; 1817, received MA from Cambridge; 1820, founded the Analytical Society with Herschel and Peacock; 1823, started work on the Difference Engine through funding from the British Government; 1827, published a table of logarithms from 1 to 108000; 1828, appointed to the Lucasian Chair of Mathematics at Cambridge (never presented a lecture); 1831, founded the British Association for the Advancement of Science; 1832, published Economy of Manufactures and Machinery ; 1833, began work on the Analytical Engine; 1834, founded the Statistical Society of London; 1864, published Passages from the Life of a Philosopher ; 1871, died.

Other Inventions: The cowcatcher, dynamometer, standard railroad gauge, uniform postal rates, occulting lights for lighthouses, Greenwich time signals, heliograph ophthalmoscope. He also had an interest in cyphers and lock-picking, but abhorred street musicians.

Babbage Observed

Near the northern pole of the moon there is a crater named for Charles Babbage. When he died in 1871, however, few people knew who he was. Only one carriage (the Duchess of Somerset's) followed in the burial procession that took his remains to Kensal Green Cemetery. The Royal Society printed no obituary, and the [London] Times ridiculed him. The parts of the Difference Engine that had seemed possible of completion in 1830 gathered dust in the Museum of King's College.

In 1878 the Cayley committee told the government not to bother constructing Babbage's Analytical Engine. By the 1880s Babbage was known primarily for his reform of mathematics at Cambridge. In 1899 the magazine Temple Bar reported that "the present generation appears to have forgotten Babbage and his calculating machine." In 1908, after being preserved for 37 years in alcohol, Babbage's brain was dissected by Sir Victor Horsley of the Royal Society. Horsley had to remind the society that Babbage had been a "very profound thinker."

Charles Babbage was born in Devonshire in 1791. Like John von Neumann , he was the son of a banker: Benjamin (Old Five Percent) Babbage. He attended Trinity College, Cambridge, receiving his MA in 1817. As the inventor of the first universal digital computer, he can indeed be considered a profound thinker. The use of Jacquard punch cards, of chains (sequences of instructions), and subassemblies, and ultimately the logical structure of the modern computer-all emanated from Babbage.

Popularly, Babbage is a sort of Abner Doubleday of data processing, a colorful fellow whose portrait hangs in the anteroom but whose actual import is slight. He is thought about, if at all, as a funny sort of distracted character with a dirty collar. But Babbage was much more than that. He was an amazing intelligence.

The Philosopher

Babbage was an aesthete, but not a typical Victorian one. He found beauty in things: stamped buttons, stomach pumps, railways and tunnels, man's mastery over nature.

A social man, he was obliged to attend the theater. While others dozed at Mozart, Babbage grew restless. "Somewhat fatigued with the opera [Don Juan]," he writes in the autobiographical Passages From the, Life of a Philosopher , "I went behind the scenes to look at the mechanism." There, a workman offered to show him around. Deserted when his Cicerone answered a cue, he met two actors dressed as "devils with long forked tails." The devils were to convey Juan, via trapdoor and stage elevator, to hell.

In his box at the German Opera some time later (again not watching the stage), Babbage noticed "in the cloister scene at midnight" that his companion's white bonnet had a pink tint. He thought about "producing colored lights for theatrical representation." In order to have something on which to shine his experimental lights, Babbage devised "Alethes and Iris," a ballet in which sixty damsels in white were to dance. In the final scene, a series of dioramas were to represent Alethes' travels. One diorama would show animals "whose remains are contained in each successive layer of the earth. In the lower portions, symptoms of increasing heat show themselves until the centre is reached, which contains a liquid transparent sea, consisting of some fluid at white heat, which, however, is filled up with little infinitesimal eels, all of one sort, wriggling eternally."

Two fire engines stood ready for the "experiment of the dance," as Babbage termed the rehearsal. Dancers "danced and attitudinized" while he shone colored lights on them. But the theater manager feared fire, and the ballet was never publicly staged.

Babbage enjoyed fire. He once was baked in an oven at 265' for "five or six minutes without any great discomfort," and on another occasion was lowered into Mt. Vesuvius to view molten lava. Did he ponder hell? He had considered becoming a cleric, but this was not an unusual choice for the affluent graduate with little interest in business or law. In 1837 he published his Ninth Bridgewater Treatise, to reconcile his scientific beliefs with Christian dogma. Babbage argued that miracles were not, as Hume wrote, violations of laws of nature, but could exist in a mechanistic world. As Babbage could program long series on his calculating machines, God could program similar irregularities in nature.

Babbage investigated biblical miracles. "In the course of his analysis," wrote B.V. Bowden in Faster than Thought (Pitman, London, 1971), "he made the assumption that the chance of a man rising from the dead is one in 10 12 ." Miracles are not, as he wrote in Passages From the Life of a Philosopher, "the breach of established laws, but ... indicate the existence of far higher laws."

The Politician

Of all his roles, Babbage was least successful at this one. He had himself to blame: he was too impatient, too severe with criticism, too crotchety. Bowden wrote that in later life Babbage "was frequently and almost notoriously incoherent when he spoke in public." What ultimately kept him from building an Analytical Engine was not his inability to finish a project, but his inadequacies as a political man, as a persuader. His vision was not matched by his judgment, patience, or sympathy.

Babbage was a confusing political figure. A liberal republican, he was pro-aristocratic and strongly antisocialist. Friend to Charles Dickens and to the workman, he was a crony to the Midlands industrialist. The son of a Tory banker, he supported the cooperative movement and was twice an unsuccessful Whig candidate to Parliament. But his liberalism waned during the 1840s; by 1865, he was a conservative utilitarian for whom capitalism and democracy were incompatible.

In July 1822, Babbage wrote a letter to the president of the Royal Society, describing his plan for calculating and printing mathematical tables by machine. By June 1823 Babbage met with the Chancellor of the Exchequer, who granted money and told Babbage to proceed with the engine (which he did, starting work in July). But no minutes were made of this initial meeting.

In August 1827, Babbage's 35 year-old wife, Georgiana, died. Babbage traveled to the Continent. By the end of 1828 he returned to England, the initial £1,500 grant gone. Babbage was financing the construction himself. And the exchequer could not recall promising further funds.

Convincing the government to continue with two tons of brass, hand-fitted steel, and pewter clockwork was not easy. In 1829 a group of Babbage's friends solicited the attention of the Duke of Wellington, and then the Prime Minister. Wellington went to see a model of the engine and in December ordered a grant of £3,000. Engineer Joseph Clement [See separate biography of Joseph Clement .] was hired to construct the engine for the government, and to oversee the fabrication of special tools. By the end of 1830 Babbage wanted to move the engine's workshop to his house on Dorset Street. A fireproof shop was built where Babbage's stables had stood. A man of great ego, Clement refused to move from his own workshop, and made, according to Babbage, "inordinately extravagant demands." Babbage would not advance Clement further money, so Clement dismissed his crew, and work on the Difference Engine ceased.

This did not seem to perturb Babbage. His initial scheme for the Difference Engine called for six decimal places and a second-order difference; now he began planning for 20 decimal places and a sixth-order difference. "His ambition to build immediately the largest Difference Engine that could ever be needed," wrote Bowden, "probably delayed the exploitation of his own ideas for a century."

With Clement and his tools gone, Babbage wanted to meet with Prime Minister Lord Melbourne in 1834 to tell him of a new machine he had conceived-the Analytical Engine, an improved device capable of any mathematical operation. He contended it would cost more to finish the original engine than to construct this new one. But the government did not wish to fund a new engine until the old one was complete. "He was ill judged enough," wrote the Reverend Richard Sheepshanks, a secretary of the Royal Astronomical Society, "to press the consideration of this new machine upon the members of Government, who were already sick of the old one." (Sheepshanks was Babbage's archenemy. In 1854 he published a vituperative 100-page work, "Letter to the Board of Visitors of the Greenwich Royal Observatory, in Reply to the Calumnies of Mr. Babbage," at its meeting in June 1853, and in his book entitled The Exposition of 1851 .)

For the next eight years Babbage continued to apply to the government for a decision on whether to continue the suspended Difference Engine or begin the Analytical Engine, seemingly unaware of the social problems that preoccupied Britain's leaders during what Macauley called the Hungry Forties. Although £17,000 of public money had been spent, and a similar amount by Babbage, the Prime Minister avoided him. "It is nonsense," wrote Sheepshanks, "to talk of consulting a Prime Minister about the kind of Calculating Machine that he wants." Prime Minister Robert Peel recommended that Babbage's machine be set to calculate the time at which it would be of use. " I would like a little previous consideration," wrote Peel, "before I move in a thin house of country gentlemen a large vote for the creation of a wooden man to calculate tables from the formula x 2 +x+41 ."

Finally, in November 1842, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, having sought the opinion of Sir George Airy on the utility of the machine, and having been told it was "worthless," said he and Peel regretted the necessity of abandoning the project. On November 11, Babbage finally met with Peel and was told the bad news.

By 1851 Babbage had "given up all expectation of constructing the Analytic Engine," even though he was to try once more with Disraeli the next year. He wrote in the vitriolic Exposition of 1851: "Thus bad names are coined by worse men to destroy honest people, as the madness of innocent dogs arises from the cry of insanity raised by their villainous pursuers."

Some believed Babbage had "been rewarded for his time and labor by grants from the public use," according to biographer Moseley Maboth ( Irascible Genius ). "We got nothing for our £17,000 but Mr. Babbage's grumblings," wrote Sheepshanks in his "Letter to the Board of Visitors of the Greenwich Royal Observatory." "We should at least have had a clever toy for our money."

Peel, however, declared in Parliament that Babbage "had derived no emolument whatsoever from the government." Offered a baronetcy in recognition of his work, Babbage refused, demanding a life peerage instead. It was never granted.

The Music Hater

Lady Lovelace wrote that Babbage hated music. He tolerated its more exquisite forms, but abhorred it as practiced on the street. "Those whose minds are entirely unoccupied," he wrote with some seriousness in Observations of Street Nuisances in 1864, "receive [street music] with satisfaction, as filling up the vacuum of time." He calculated that 25% of his working power had been destroyed by street nuisances, many of them intentional. Letters to the Times and the eventual enforcement of "Babbage's Act," which would squelch street nuisances, made him the target of ridicule.

The public tormented him with an unending parade of fiddlers, Punch-and Judys, stilt-walkers, fanatic psalmists, and tub-thumpers. Some neighbors hired musicians to play outside his windows. Others willfully annoyed him with worn-out or damaged wind instruments. Placards were hung in local shops, abusing him. During one 80-day period Babbage counted 165 nuisances. One brass band played for five hours, with only a brief intermission. Another blew a penny tin whistle out his window toward Babbage's garden for a half hour daily, for "many months."

When Babbage went out, children followed and cursed him. Adults followed, too, but at a distance. Over a hundred people once skulked behind him before he could find a constable to disperse them. Dead cats and other "offensive materials" were thrown at his house. Windows were broken. A man told him, "You deserve to have your house burnt up, and yourself in it, and I will do it for you, you old villain." Even when he was on his deathbed, the organ-grinders ground away implacably.

In Babbage's relation with "the Mob," we see his curious naïveté in matters social. Although he was far above the rabble-"not unknown" to the Duke of Wellington and Lord Ashley-he seemed unaware of it at times. He expected the same civility from a drunken brothel-keeper as he would from a gentleman. In 1860, the London of the multitudinous poor was far from gentle. Yet, in his ingenuousness, he could fathom neither bums nor bamboozlers. He would cross town to check the tale of a mendicant, and frequently was surprised to encounter deceit.

Babbage once met a man who claimed not to have eaten for two days. Babbage invited him to breakfast. The next morning he called at Babbage's house, claiming hard times. Eventually, the man hired on as a steward on a small West Indian ship. "A few evenings after the ship had supposed to have sailed, he called at my house," wrote Babbage, "apparently much agitated and stated that, in raising the anchor, an accident had happened, by which the captain's leg had been broken." Babbage later tried to verify this tale, but found his steward "had been living riotously at some public-house in another quarter, and had been continually drunk."

Babbage never understood that the growth and crowdedness of London resulted from the industrial expansion he championed. By 1850 industry had taken over in Britain. "Many years before, I had purchased a house in a very quiet locality," he wrote in 1864. Then came a hackney stand, and beer shops and coffeehouses, and people. The din beneath his window, the German bands, the pickpockets, came with industry. The railroad and factory brought crowds to London, and with them came meanness and thievery.

The Newtonian

Like Newton, Babbage was Lucasian professor of mathematics at Cambridge. He founded both the British Association's Statistical Society and the Royal Astronomical Society. His Difference Engine calculated by Newton's method of successive differences, and would even accomplish "operations of human intellect" by motive power. Babbage believed in a world where, once all things were dutifully quantified, all things could be predicted. As such, he was a perfect Newtonian.

Nature, according to Question 31 of Newton's Opticks, is "very consonant and conformable to herself." Newton's program was official in Babbage's time. Science "consisted in isolating some central, specific act, and then using it as the basis for all further deductions concerning a given set of phenomena," writes Ilya Prigogine in Order Out of Chaos . The Marquis Laplace, an avid Newtonian and friend of Babbage, said that if a mind could know everything about particle behavior, it could describe everything: "Nothing would be uncertain, and the future, as the past, could be present to our eyes."

Babbage wanted to quantify everything. Fact and data intoxicated him. He tried handicapping horse races mathematically. Babbage's love of numbers was well known: in the mail he received requests for statistics. He would preserve any fact, simply because he thought "the preservation of any fact might ultimately be useful."

He would stop to measure the heartbeat of a pig (to be listed in his "Table of Constants of the Class Mammalia"), or to affix a numerical value to the breath of a calf. In 1856 he proposed to the Smithsonian Institution that an effort be made to produce "Tables of Constants of Nature and Art," which would "contain all those facts which can be expressed by numbers in the various sciences and arts."

Babbage delighted in the thought of having a daily account of food consumed by zoo animals, or the "proportion of sexes amongst our poultry." He proposed tables to calibrate the amount of wood (elm or oak) a man would saw in ten hours, or how much an ox or camel could plow or mow in a day.

Babbage's unflagging fascination with statistics occasionally overwhelmed him, as is seen in the animation of his Smithsonian proposal. "If I should be successful," he wrote, ". . . it will thus call into action a permanent cause of advancement toward truth, continually leading to the more accurate determination of established fact, and to the discovery and measurement of new ones."

In Mechanics Magazine in 1857 Babbage published a "Table of the Relative Frequency of the Causes of Breaking of Plate Glass Windows," detailing 464 breakages, of which "drunken men, women, or boys" were responsible for fourteen. Babbage thought the table would be "of value in many respects," and might "induce others to furnish more extensive collections of similar and related facts."

Babbage faced significant problems with mechanical techniques. He had to invent the tools for his engine. His thought is so thoroughly modern that we wonder why he did not pursue electromechanical methods for his engines (especially after Faraday's 1831 discovery of induction and Babbage's own electrical experiments). It is easy to forget how long ago Babbage worked.

Even under the best of circumstances, the limitations of Newtonian physics might have prevented Babbage from completing any Analytical Engine. He did not know the advances of Maxwell (and could not know those of Boltmann, Gödel, and Heisenberg). Although he knew Fourier socially, Babbage did not seem to grasp the importance of his 1811 work on heat propagation, nor did he seem to know of Joule's efforts with heat and mechanical energy.

The reversibility of attraction is a basic tenet of Newtonian mechanics. A body, or piece of information, may retrace its path and return to where it started. In Babbage's design for the Analytical Engine, the discrete functions of mill (in which "all operations are performed") and store (in which all numbers are originally placed, and, once computed, are returned) rely on this supposition of reversibility.

In his 1824 essay on heat, Carnot formulated the first quantitative expression of irreversibility, by showing that a heat engine cannot convert all supplied heat energy into mechanical energy. Part of it is converted to useful work, but most is expelled into a low-temperature reservoir and wasted.

From this observation came William Thomson's discovery of the Second Law of Thermodynamics in 1852, and Rudolf Clausius' discovery of entropy in 1865. In ideal reversible processes, entropy remains constant. But in others, as Eddington showed with his "arrow of time," entropy only increases; thus, information cannot be shuttled between mill and store without leaking (some possibility of error), like faulty sacks of flour. Babbage did not consider this problem, and it was perhaps his greatest obstacle to building the engine.

It is easy to forget that Babbage was essentially a child of the Enlightenment, and that his epoch was much different from our own. He resided in an era of wood and coal, and the later era of steel and oil would not begin for perhaps a decade after his death.

The Industrialist

"Faith in machinery," wrote Matthew Arnold in Culture and Anarchy in 1869, "is our besetting danger." The Whiggery of the mid-Victorian era optimistically endorsed the principle of progress. Britain changed from the relatively pastoral society of 1820 to the brutishly materialistic one of the 1840s and 1850s.

Babbage shared his era's enthusiasm for industry. His finest work, On the Economy of Manufactures, was published in 1832. In it, with watch in hand, Babbage discovers operational research, the scientific study of manufacturing processes. It is a tour of the manufacturing processes of the period, from needle-making to tanning. Babbage detailed how things both ornamental and functional were made in mid-nineteenth century Britain. His characteristically blunt analysis of the printing trade caused publishers to refuse his books.

Babbage worked when industry was in a frenzy to improve and expand. Increases in manufacturing and population were viewed as "absolute goods in themselves," noted Matthew Arnold. In Das Kapital, Marx quoted from Economy of Manufactures on this rage to improve: "Improvements succeeded each other so rapidly, that machines which had never been finished were abandoned in the hands of their makers, because new improvements had superseded their utility."

Babbage disliked Plato, according to his friend Wilmot Buxton, because of Plato's condemnation of Archytas, "who had constructed machines of extraordinary power on mathematical principles." Plato thought such an application of geometry degraded a noble intellectual exercise, "reducing it to the low level of a craft fit only for mechanics and artisans."

Babbage loved practical science, and was among the first to apply higher mathematics to certain commercial and industrial problems. He took no part in what Anthony Hyman (in his book, Charles Babbage ) called the era's "growing divorce between academic science and engineering practice."

Babbage had a forge built in his house on Devonshire Street, and accomplished, with his draftsmen, pioneering work in precision engineering. Because conventional mechanical drawing proved inadequate for his engines, he had to develop his own abstract notation. He called his work with mechanical notation "one of the most important additions I have made to human knowledge."

With the die-cast pewter gear wheels of his Difference Engine, and with his design of lathes and tool-shapers, Babbage did much to advance the British machine tool industry. Joseph Whitworth (later Sir), foreman in Babbage's shop, was responsible for the introduction of the first series of standard screw threads.

The expansion of the railways marked the grandest phase of the industrial revolution. Railroads freed manufacturing from its dependence on water transport, and opened new markets. When the first public railroad, the Stockton & Darlington, opened on September 27, 1823, Babbage was 34. By 1841 there were over 1,300 miles of rail in Britain, and 13,500 miles by 1870. J.D. Bernal wrote in Science and Industry in the Nineteenth Century, that "Babbage seems to have been one of the few who interested themselves scientifically in its [the railroad's] working." Babbage's life was intertwined with the railroad. He invented a cow catcher in 1838, apparently the first in Britain. He was present for opening ceremonies of George Stephenson's Manchester & Liverpool line in 1830. Of the cheering crowds at the initial run, he wrote, "I feared . . . the people madly attempting to stop by their feeble arms the momentum of our enormous train."

Babbage's great formal association with railroads came in 1837 and 1838, when he conducted experiments for I.K. Brunel's Great Western Railway, which ran from London to Bristol. Babbage argued for the superiority of Brunel's wide-gauge track. His research into the safety and efficiency of the line was, according to Bernal, "100 years ahead of his time."

Babbage rode the rails like a river pilot road the Mississippi, knowing every turn on the route, every crossing, every intersection. "My ear," he wrote, "had become peculiarly sensitive to the distant sound of an engine."

The Misanthrope

Babbage was known as a "mathematical Timon." In his later years he came to suffer from a mechanist's misanthropy, regarding men as fools and grubby thieves. By 1861 he said he had never spent a happy day in his life, and would gladly give up the rest of it if he could live three days 500 years thence.

Laughed at by costermongers and viscounts, met with diffidence by his lessers, the impatient Babbage grew angry, like the cave-dwelling Timon, with a changing world. Nevertheless, as his friend Lionel Tollemache wrote, "there was something harmless and even kindly in his misanthropy, for ... he hated mankind rather than man, and his aversion was lost in its own generality."

Like Shakespeare's Timon, Babbage would have made a fascinating leader. (Sheepshanks, of course, disagreed: "I don't know any Government office or any other office for which he is fit, certainly none which requires sense and good temper.")

What a delightful, if distracting, place it would be where Babbage was in charge. Consider his plan in Economy of Manufactures for a "simple contrivance of tin tubes for speaking through." (Babbage calculated it would take 17 minutes for words spoken in London to reach Liverpool.) Or his plan for sending messages "enclosed in small cylinders," along wires suspended from high pillars (he thought church steeples could be used for this purpose.)

In Passages, Babbage relates how, as a youth, he nearly drowned while testing his contrivance for walking on water. In Conjectures on the Conditions of the Surface of the Moon, we find him describing his 1837 experiments in cooking a "very respectable stew of meat and vegetables" in blackened boxes (with window glass) buried in the earth. Toward the end of his life we find him mulling the prevention of bank note forgery and working in marine navigation. We realize that, with his harlequin curiosity about all things, and with his wonderfully human sense of wonder, Babbage escapes pathos and attains greatness.

"Some of my critics have amused their readers with the wildness of the schemes I have occasionally thrown out; and I myself have sometimes smiled along with them. Perhaps it were wiser for present reputation to offer nothing but profoundly meditated plans, but I do not think knowledge will be most advanced by that course; such sparks may kindle the energies of other minds more favorably circumstanced for pursuing the enquiries." (On the Economy of Machinery and Manufactures, 1832, preface to second edition)

"Every moment dies a man / Every moment 1 1 / 16 is born." (A correction to Tennyson's "Every moment a man dies/Every moment one is born.")

"If unwarned by my example, any man shall undertake and shall succeed in really constructing an engine ... upon difference principles or by simpler means, I have no fear of leaving my reputation in his charge, for he alone will be fully able to appreciate the nature of my efforts and the value of their results." [Quoted in the Babbage exhibit at the Science Museum, Kensington; attributed to Babbage in 1864.]

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Biographical.

Babbage, Henry P., ed., Babbage's Calculating Engines: Being a Collection of Papers Relating to Them, Their History, and Construction , E. and F.N. Spoon, London, 1889.

Babbage, H.P., "Babbage's Analytical Engine," reprinted in Randell, Brian, ed., Origins of Digital Computers: Selected Papers , Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg, 1982, pp. 19-54.

Babbage, Neville F., "Autopsy Report on the Body of Charles Babbage ("the father of the computer")," Medical J. Australia, Vol. 154, 1991, pp. 758-759.

Bromley, Alan G., "Charles Babbage's Analytical Engine," Ann. Hist. Comp. , Vol. 4, No. 3, 1982, p. 196.

Buxton, W.H., Memoir of the Life and Labours of the Late Charles Babbage E'sq. FR.S. , Vol. 13, Charles Babbage Institute Reprint Series of the History of Computing, MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1988.

Campbell-Kelly, Martin, "Charles Babbage's Table of Logarithms," Ann. Hist. Comp. , Vol. 10, No. 3, 1988, p. 159ff.

Campbell-Kelly, Martin, ed., The Works of Charles Babbage , Pickering and Chatto, London, 1989, 11 Volumes.

Cohen, L Bernard, "Babbage and Aiken," Ann. Hist. Comp. , Vol. 10, No. 3, 1988, p. 171ff.

Davies, Donald Watts, "Babbage's Friend," (CQD), Ann. Hist. Comp. , Vol. 12, No. 2, 1990, p. 147ff.

Dubbey, J. M., The Mathematical Work of Charles Babbage , Cambridge Univ. Press, New York, 1978.

Froehlich, Leopold, "Babbage Observed," Datamation , Cahners/Ziff Pub. Assoc., Mar. 1985.

Gridgeman, N. T., The Mathematical Work of Charles Babbage (review), Ann. Hist. Comp. , Vol. 1, No. 1, 1979.

Halacy, Dan, Charles Babbage, Father of the Computer , Macmillan, New York, 1970.

Harrison, Thomas J., "Charles and the Computer," Measurement and Control , Vol. 19, Apr. 1986, pp. 84-91.

Hyman, Anthony, Charles Babbage, Pioneer of the Computer , Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton, N.J.,1982.

Hyman, Anthony, "Babbage Studies," (CQD), Ann. Hist. Comp. , Vol. 11, No. 3, 1989, p. 225ff.

Huskey, Harry and Velma, "Lady Lovelace and Charles Babbage," Ann. Hist. Comp. , Vol. 2, No. 4, 1980, pp. 299-329.

Huskey, Harry and Velma, "Charles Babbage and Lady Lovelace," (anecdote), Ann. Hist. Comp. , Vol. 3, No. 4, 198 1, p. 414ff.

Huskey, Velma, "Who Was the Mysterious Countess?," (anecdote), Ann. Hist. Comp. , Vol. 7, No. 1, 1985, p. 58ff.

Kean, David W., The Author of the Analytical Engine , Thompson Book Co., Washington D.C., 1966.

Morrison, Philip and Emily, Charles Babbage and his Calculating Machines , Dover Publications, New York, 1961.

Nagler, Harry, "Napier and Babbage," (anecdote), Ann. Hist. Comp. , Vol. 2, No. 2, 1980, p. 186ff.

Robert, C.J.D., "Babbage's Diff. Eng. No.1 and ... Sine Tables," (CQD), Ann. Hist. Comp. , Vol. 9, No. 2, 1987, p. 210ff.

Slater, Robert, Portraits in Silicon , MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1987.

Smillie, K. W., "Mr. Babbage's Calculating Machine," (CQD), Ann. Hist. Comp. , Vol. 2, No. 3, 1980, p. 268ff.

van Sinderen, Alfred, "The Printed Papers of Charles Babbage," Ann. Hist. Comp ., Vol. 2, No. 2,1980, pp. 169-185.

van Sinderen, Alfred, "The Trinity House," (correction), Ann. Hist. Comp. , Vol. 3, No. 1, 1981, p. 73.

van Sinderen, Alfred, "A. Hyman: Charles Babbage" (review), Ann. Hist. Comp. , Vol. 5, No. 1, 1983, p. 76.

van Sinderen, Alfred, "Babbage's Letter to Quetelet, May 1835," Ann. Hist. Comp. , Vol. 5 No. 3, 1983, p. 263ff.

van Sinderen, Alfred, "Babbage and the Scheutz Machine Ann. Hist. Comp. , Vol. 10, No. 2, 1988, p. 133ff.

van Sinderen, Alfred, "Babbage and Bowditch," (CQD), Ann. Hist. Comp. , Vol. 10, No. 3, 1988, p. 218ff.

Wilkes, Maurice V., "Babbage, Charles" in Ralston, Anthony, and Edwin D. Reilly Jr., Encyclopedia of Computer Science and Engineering , Van Nostrand Reinhold Co., New York, 1983. [Also in 3ed edition.]

Wilkes, Maurice V., "Babbage's Expectations for the Diff. Engine," (anecdote), Ann. Hist. Comp. , Vol. 9, No. 2, 1987, p. 203ff.

Wilkes, Maurice V., "Babbage and the Colossus," (CQD), Ann. Hist. Comp. , Vol. 10, No. 3, 1988, p. 218ff.

Wilkes, Maurice V., "Babbage's Expectations for his Engines," Ann. Hist. Comp. , Vol. 13, No. 2, 199 1, pp. 141-146.

Wilkes, Maurice V., "Pray, Mr. Babbage...", A Play, Ann. Hist. Comp. , Vol. 13, No. 2,1991, pp. 147-154.

Wilkes, Maurice V., "Charles Babbage-The Great Uncle of Computing?," Comm. ACM , Vol. 35, No. 3, 1992, pp. 15-16,21.

Significant Publications

Babbage, Charles, "Observations on the Application of Machinery to the Computation of Mathematical Tables," Memoirs of the Astronomical Society , Vol. 1, No. 2, 1825, pp. 311-314.

Babbage, Charles, Economy of Machinery and Manufactures , Charles Knight, London, 1832.

Babbage, Charles, "On the Mathematical Powers of the Calculating Engine, unpublished MS, reprinted in Randell, B., ed., The Origins of Digital Computers: Selected Papers , Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 1973, pp. 19-54.

Babbage, Charles, Passages from the Life of a Philosopher , Longmans and Green, London, 1864, reprinted with introduction by Martin Campbell-Kelly, IEEE Press, Piscataway, NJ., 1994.

(Babbage portrait inserted by MRW, 2012)

PDF version

Alan Turing

(1912-1954)

Who Was Alan Turing?

Alan Turing was a brilliant British mathematician who took a leading role in breaking Nazi ciphers during WWII. In his seminal 1936 paper, he proved that there cannot exist any universal algorithmic method of determining truth in mathematics, and that mathematics will always contain undecidable propositions. His work is widely acknowledged as foundational research of computer science and artificial intelligence.

English scientist Alan Turing was born Alan Mathison Turing on June 23, 1912, in Maida Vale, London, England. At a young age, he displayed signs of high intelligence, which some of his teachers recognized, but did not necessarily respect. When Turing attended the well-known independent Sherborne School at the age of 13, he became particularly interested in math and science.

After Sherborne, Turing enrolled at King's College (University of Cambridge) in Cambridge, England, studying there from 1931 to 1934. As a result of his dissertation, in which he proved the central limit theorem, Turing was elected a fellow at the school upon his graduation.

In 1936, Turing delivered a paper, "On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem," in which he presented the notion of a universal machine (later called the “Universal Turing Machine," and then the "Turing machine") capable of computing anything that is computable: It is considered the precursor to the modern computer.

Over the next two years, Turing studied mathematics and cryptology at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey. After receiving his Ph.D. from Princeton University in 1938, he returned to Cambridge, and then took a part-time position with the Government Code and Cypher School, a British code-breaking organization.

Cryptanalysis and Early Computers

During World War II, Turing was a leading participant in wartime code-breaking, particularly that of German ciphers. He worked at Bletchley Park, the GCCS wartime station, where he made five major advances in the field of cryptanalysis, including specifying the bombe, an electromechanical device used to help decipher German Enigma encrypted signals.

Turing’s contributions to the code-breaking process didn’t stop there: He also wrote two papers about mathematical approaches to code-breaking, which became such important assets to the Code and Cypher School (later known as the Government Communications Headquarters) that the GCHQ waited until April 2012 to release them to the National Archives of the United Kingdom.

Turing moved to London in the mid-1940s, and began working for the National Physical Laboratory. Among his most notable contributions while working at the facility, Turing led the design work for the Automatic Computing Engine and ultimately created a groundbreaking blueprint for store-program computers. Though a complete version of the ACE was never built, its concept has been used as a model by tech corporations worldwide for several years, influencing the design of the English Electric DEUCE and the American Bendix G-15 — credited by many in the tech industry as the world’s first personal computer — among other computer models.

Turing went on to hold high-ranking positions in the mathematics department and later the computing laboratory at the University of Manchester in the late 1940s. He first addressed the issue of artificial intelligence in his 1950 paper, "Computing machinery and intelligence," and proposed an experiment known as the “Turing Test” — an effort to create an intelligence design standard for the tech industry. Over the past several decades, the test has significantly influenced debates over artificial intelligence.

Homosexuality, Conviction and Death

Homosexuality was illegal in the United Kingdom in the early 1950s, so when Turing admitted to police, called to his house after a January 1952 break-in, that he'd had a sexual relationship with the perpetrator, 19-year-old Arnold Murray, he was charged with gross indecency. Following his arrest, Turing was forced to choose between temporary probation on the condition that he receive hormonal treatment for libido reduction, or imprisonment. He chose the former, and soon underwent chemical castration through injections of a synthetic estrogen hormone for a year, which eventually rendered him impotent.

As a result of his conviction, Turing's security clearance was removed and he was barred from continuing his work with cryptography at the GCCS, which had become the GCHQ in 1946.

Turing died on June 7, 1954. Following a postmortem exam, it was determined that the cause of death was cyanide poisoning. The remains of an apple were found next to the body, though no apple parts were found in his stomach. The autopsy reported that "four ounces of fluid which smelled strongly of bitter almonds, as does a solution of cyanide" was found in the stomach. Trace smell of bitter almonds was also reported in vital organs. The autopsy concluded that the cause of death was asphyxia due to cyanide poisoning and ruled a suicide.

In a June 2012 BBC article, philosophy professor and Turing expert Jack Copeland argued that Turing's death may have been an accident: The apple was never tested for cyanide, nothing in the accounts of Turing's last days suggested he was suicidal and Turing had cyanide in his house for chemical experiments he conducted in his spare room.

Awards, Recognition and Royal Pardon

Shortly after World War II, Turing was awarded an Order of the British Empire for his work. For what would have been his 86th birthday, Turing biographer Andrew Hodges unveiled an official English Heritage blue plaque at his childhood home.

Turing was honored in a number of other ways, particularly in the city of Manchester, where he worked toward the end of his life. In 1999, Time magazine named him one of its "100 Most Important People of the 20th century," saying, "The fact remains that everyone who taps at a keyboard, opening a spreadsheet or a word-processing program, is working on an incarnation of a Turing machine." Turing was also ranked 21st on the BBC nationwide poll of the "100 Greatest Britons" in 2002. By and large, Turing has been recognized for his impact on computer science, with many crediting him as the "founder" of the field.

Following a petition started by John Graham-Cumming, then-Prime Minister Gordon Brown released a statement on September 10, 2009, on behalf of the British government, which posthumously apologized to Turing for prosecuting him as a homosexual.

"This recognition of Alan's status as one of Britain's most famous victims of homophobia is another step towards equality and long overdue. But even more than that, Alan deserves recognition for his contribution to humankind," Brown stated. "It is thanks to men and women who were totally committed to fighting fascism, people like Alan Turing, that the horrors of the Holocaust and of total war are part of Europe's history and not Europe's present. So on behalf of the British government, and all those who live freely thanks to Alan's work I am very proud to say: we're sorry, you deserved so much better."

In 2013, Queen Elizabeth II posthumously granted Turing a rare royal pardon almost 60 years after he committed suicide. Three years later, on October 20, 2016, the British government announced “Turing’s Law” to posthumously pardon thousands of gay and bisexual men who were convicted for homosexual acts when it was considered a crime. According to a statement issued by Justice Minister Sam Gyimah , the law also automatically pardons living people who were “convicted of historical sexual offenses who would be innocent of any crime today.

In July 2019, the Bank of England announced that Turing would appear on the UK's new £50 note, along with images of his work. The famed scientist was chosen from a list of nearly 1,000 candidates nominated by the general public, including theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking and mathematician Ada Lovelace .

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Alan Turing

- Birth Year: 1912

- Birth date: June 23, 1912

- Birth City: London

- Birth Country: United Kingdom

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: The famed code-breaking war hero, now considered the father of computer science and artificial intelligence, was criminally convicted and harshly treated under the U.K.'s homophobic laws.

- Astrological Sign: Cancer

- Sherborne School

- Princeton University

- Princeton Institute for Advanced Study

- St. Michael's School

- King's College (University of Cambridge)

- Death Year: 1954

- Death date: June 7, 1954

- Death City: Wilmslow

- Death Country: United Kingdom

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Alan Turing Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/scientists/alan-turing

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: July 22, 2020

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

- We can only see a short distance ahead, but we can see plenty there that needs to be done.

- I believe that at the end of the century the use of words and general educated opinion will have altered so much that one will be able to speak of machines thinking without expecting to be contradicted.

- Science is a differential equation. Religion is a boundary condition.

- A computer would deserve to be called intelligent if it could deceive a human into believing that it was human.

Famous British People

Amy Winehouse

Mick Jagger

Agatha Christie

Alexander McQueen

The Real Royal Scheme Depicted in ‘Mary & George’

William Shakespeare

Anya Taylor-Joy

Kate Middleton, Princess of Wales

Kensington Palace Shares an Update on Kate

Prince William

Who is the father of the computer?

There are hundreds of people who have made major contributions to the field of computing. The following sections detail the primary founding fathers of computing, the computer, and the personal computer we use today.

Father of computing

Charles Babbage was considered the father of computing after his concept and invention of the Analytical Engine in 1837 . The Analytical Engine contained an ALU (arithmetic logic unit), basic flow control , and integrated memory , hailed as the first general-purpose computer concept. Unfortunately, because of funding issues, this computer was not built while Charles Babbage was alive.

However, in 1910 , Henry Babbage, Charles Babbage's youngest son, completed a portion of the machine that could perform basic calculations. In 1991 , the London Science Museum completed a working version of the Analytical Engine No. 2. This version incorporated Babbage's refinements, which he developed while creating the Analytical Engine.

Although Babbage never completed his invention in his lifetime, his radical ideas and concepts of the computer make him the father of computing.

Father of the computer

Several people can be considered the father of the computer, including Alan Turing , John Atanasoff , and John von Neumann . However, we consider Konrad Zuse as the father of the computer with the advent of the Z1, Z2, Z3, and Z4.

From 1936 to 1938 , Konrad Zuse created the Z1 in his parent's living room. The Z1 had over 30,000 metal parts and was the first electromechanical binary programmable computer. In 1939 , the German military commissioned Zuse to build the Z2, largely based on the Z1. Later, he completed the Z3 in May 1941 ; the Z3 was a revolutionary computer for its time and is considered the first electromechanical and program-controlled computer. Finally, on July 12, 1950 , Zuse completed and shipped the Z4 computer, the first commercial computer.

Father of the personal computer

Henry Edward Roberts coined the term "personal computer" and is considered the father of modern personal computers after he released the Altair 8800 on December 19, 1974 . It was later published on the front cover of Popular Electronics in 1975 , making it an overnight success. The computer was available as a kit for $439 or assembled for $621 and had several additional add-ons, such as a memory board and interface boards. By August 1975, over 5,000 Altair 8800 personal computers were sold, starting the personal computer revolution.

Other computer pioneers

Thousands of pioneers have helped contribute to developing the computer we know today. See our computer pioneer list for additional biographies of foundational computer visionaries.

Related information

- When was the first computer invented?

- Computer people and pioneers.

- See our mother page for female pioneers.

- Computer history questions and answers.

Advertisement

Alan Turing

By Jacob Aron

Alan Turing was one of the most influential British figures of the 20th century. In 1936, Turing invented the computer as part of his attempt to solve a fiendish puzzle known as the Entscheidungsproblem .

This mouthful was a big headache for mathematicians at the time, who were attempting to determine whether any given mathematical statement can be shown to be true or false through a step-by-step procedure – what we would call an algorithm today.

Turing attacked the problem by imagining a machine with an infinitely long tape. The tape is covered with symbols that feed instructions to the machine, telling it how to manipulate other symbols. This universal Turing machine , as it is known, is a mathematical model of the modern computers we all use today.

Using this model, Turing determined that there are some mathematical problems that cannot be solved by an algorithm, placing a fundamental limit on the power of computation . This is known as the Church–Turing thesis , after the work of US mathematician Alonzo Church, who Turing would go on to study his doctorate under at Princeton University in the United States.

Turing’s wartime legacy

Turing’s contributions to the modern world were not merely theoretical. During the second world war, he worked as a codebreaker for the UK government, attempting to decode the Enigma cipher machine encryption devices used by the German military.

Enigma was a typewriter-like device that worked by mixing up the letters of the alphabet to encrypt a message. UK spies were able to intercept German transmissions, but with nearly 159 billion billion possible encryption schemes, they seemed impossible to decode.

Building on work by Polish mathematicians, Turing and his colleagues at the codebreaking centre Bletchley Park developed a machine called the bombe capable of scanning through these possibilities.