Daniel Caesar, Case Study 01 | Album Review 💿

Published by the musical hype on july 3, 2019 july 3, 2019.

Fresh off of his first Grammy win, Canadian R&B standout Daniel Caesar delivers a strong follow-up to his debut album (‘ Freudian ’) with ‘ Case Study 01 .’

R&B music has hit it fair share of “bumps in the road” over the years, cooling down tremendously over the years. Regardless, the genre has still managed to have its fair share of bright spots, including Grammy-winning, Canadian standout, Daniel Caesar. Caesar delivered one of the very best albums, regardless of genre, with his debut LP, Freudian in 2017. Freudian blended themes of love and spirituality superbly. Since then, the artist has had some missteps , not musically mind you, but socially and culturally . Focusing on solely on the music, his highly-anticipated follow-up, Case Study 01 , continues the excellence, while bringing in some talented collaborators: Brandy , Pharrell Williams , Sean Leon , Jacob Collier , and John Mayer .

It’s not every album that features a song that references physics, particular a R&B album. Standout ✓ “Entropy” earns that distinction, and Daniel Caesar actually says the word on the chorus of the song:

“Oh, how can this be? I finally found peace Just how long ‘til she’s stripped from me? So, come on, baby, in time we’ll all freeze Ain’t no stoppin’ that entropy .”

Sure, the concept of entropy itself can get technical, but in broad terms, it boils down to “chaos, disorganization, randomness”; a lack of order or predictability. Within the soulful song, Caesar highlights the unpredictability of life and love. He even manages to fuse science and spirituality on the outro: “Drifting towards the deep freeze / Thermodynamics, there’s no escape / The good Lord he gives, the Lord he takes / No life without energy.”

The love-centric ✓ “Cyanide” keeps Case Study 01 an intriguing listening experience. The production remains soulful, benefiting from an old-school Tommy James and the Shondells sample ( “Candy Maker” ). Also, keeping things fresh, are guest vocals by Toronto rapper Kardinal Offishall , which brings a cool Jamaican element into the picture. As if the first two songs weren’t great in their own right, Brandy joins Caesar for the terrific duet, ✓ “Love Again.” The relationship has ended, yet both seem to be willing to find reconciliation. Both offer their perspective on where things fell short, offering up a seemingly simple solution: “If you can take my hand / I promise we’ll find love again.”

“Frontal Lobe Muzik”

If “Love Again” was kinder, gentler Daniel Caesar, than he toughens up his sound on “Frontal Lobe Muzik” featuring Pharrell Williams . Williams sings on the love-centric chorus, while The Neptunes handle production duties. No, Caesar doesn’t go extremely left of center, but as he did throughout Freudian , he is more profane, uses more slang, and embraces a more ‘street smart’ sensibility. He still retains an approach idiomatic of R&B, even if it dips into hip-hop without crossing any lines.

✓ “Open Up” is the gospel-tinged slow-jam that R&B lovers definitely need in their lives. That said, there’s nothing ‘spiritual’ about “Open Up,” which finds Caesar being overtly sexual yet also emotionally invested – “The piano that I fuck you on / Same one that on which I write these songs for you.” The big thing he desires from her is to “…Open up to me, girl / Let me plant my seed, girl / Let me fill your needs, girl.”

“Restore the Feeling”

“Restore the Feeling” brings Sean Leon and Jacob Collier into the mix. Caesar sings the first verse himself, while Collier joins him on the memorable chorus, adding some smooth harmonies. Leon sings and raps the second verse, providing a clear contrast to Caesar. The best moment of “Restore the Feeling” is arguably the outro, which expands upon Collier’s awesome contributions. This is a good song, but arguably, it could use just a slight bit more finesse to make it truly great.

Physics once more enters the mix on ✓ “Superposition” featuring John Mayer . True to the title, Caesar bases the record itself on the idea/theory of superposition . It begins from the start, where he sings on the first verse, “Isn’t it an irony? / The things that inspire me / they make me bleed / so profusely.” On the chorus, much like “Entropy,” he directly references superposition:

“Exist in superposition Life’s all about contradiction Yin and yang Fluidity and things I’m me, I’m God I’m everything I’m my own reason why I sing And so are you, are you understanding?”

The second verse is quite deep, highlighted by the lyric, “If I should die before I wake / Oh, please do not resuscitate / I know I didn’t live my life in vain / This music shit’s a piece of cake / The rest of my life’s in a state of chaos…”

“Too Deep to Turn Back”

“So, what’s the price / We’re like mosquitos to light, in a sense / I feed off bioluminescence…” Case Study 01 continues to be complex, yet rewarding project, further evidenced by the lovely “Too Deep to Turn Back.” If it hasn’t been highlighted, Daniel Caesar sounds fantastic, never needing to ‘break a sweat’ to pack a punch. Here, religion plays a significant role, specifically on the chorus, which features vocals by Arianna Reid , as well as the fourth verse (“I’ve slept like Jacob, a rock for a pillow / Run swift like Elijah, away from the middle”).

Two more songs grace Case Study 001 . “Complexities” possesses a lovely backdrop by all means, even if the song itself isn’t as cutting edge or as intriguing as the best of the album. “Are You Ok?” closes equally lovely, featuring more introspection from Caesar that has characterized the album as a whole. An instrumental break signals a change of pace, one that finds Caesar addressing ‘Emily’ a couple of times (“Sweet Emily, my bride to be / Struggle with me, if I’d entropy …”) At six-and-a-half minutes it is a bit demanding, but also rewarding in many respects.

Final Thoughts

So, earlier, we said that Freudian was one of the best albums released regardless of genre in 2017. The same can be said of Case Study 01 , which gives R&B lovers another reason to have faith in the genre. Furthermore, this particular project gives all music lovers a truly creative and well-rounded album, one with many memorable moments. One thing is for sure – Daniel Caesar is a truly special, truly talented musician. You can argue that the end of the album isn’t quite as punchy as the beginning, but all in all, Case Study 01 has its fair share of excellence.

✓ Gems : “Entropy,” “Cyanide,” “Love Again,” “Open Up” & “Superposition”

Daniel Caesar • Case Study 01 • Golden Child Recordings • Release : 6.28.19

Photo credit : golden child recordings.

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

the musical hype

the musical hype aka Brent Faulkner has earned Bachelor and Masters degrees in music (music Education, music theory/composition respectively). A multi-instrumentalist, he plays piano, trombone, and organ among numerous other instruments. He's a certified music educator, composer, and a freelance music journalist. Faulkner cites music and writing as two of the most important parts of his life. Notably, he's blessed with a great ear, possessing perfect pitch.

13 Totally Captivating Songs That Reference Science | Playlist · July 5, 2019 at 12:01 am

[…] Daniel Caesar, Case Study 01 | Album Review Fresh off of his first Grammy win, Canadian R&B standout…Read More […]

Comments are closed.

Related posts.

![case study 001 Dan Jarman, boys hurting boys: Beaming with Pride 🏳️🌈 No. 38 (2024) [📷: Brent Faulkner/ The Musical Hype; Dan Jarman; Elias Souza, Los Muertos Crew from Pexels; CatsWithGlasses, David, Maicon Fonseca Zanco, Square Frog, Sudo from Pixabay]](https://i0.wp.com/themusicalhype.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/dan-jarman-boys-hurting-boys-beaming-with-pride-38-2024.jpg?resize=360%2C240&ssl=1)

- Beaming with Pride 🏳️🌈

Dan Jarman, boys hurting boys | Beaming with Pride 🏳️🌈

In the 38th edition of Beaming with Pride 🏳️🌈 (2024), we highlight the song, “boys hurting boys” performed by Dan Jarman.

![case study 001 The Rascals, A Beautiful Morning: Throwback Vibez 🕶️🎶 No. 109 (2024) [📷: Brent Faulkner / The Musical Hype; Atlantic; OpenClipart-Vectors, Speedy McVroom from Pixabay]](https://i0.wp.com/themusicalhype.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/the-rascals-a-beautiful-morning-throwback-vibez-109-2024.jpg?resize=360%2C240&ssl=1)

The Rascals, A Beautiful Morning | Throwback Vibez 🕶️🎶

In the 109th edition of Throwback Vibez (2024), we recollect and reflect on “A Beautiful Morning” by The Rascals.

![case study 001 13 Ill Songs with 🎶 MUSIC 🎶 in the Title (2024) [📷: Brent Faulkner / The Musical Hype; Gordon Johnson, Mickey Mikolauskas, OpenClipart-Vectors, Paulo365, from Pixabay]](https://i0.wp.com/themusicalhype.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/13-ill-songs-with-music-in-the-title.jpg?resize=360%2C240&ssl=1)

13 Ill Songs with 🎶 MUSIC 🎶 in the Title | Playlist 🎧

13 Ill Songs with 🎶 MUSIC 🎶 in the Title features MUSIC songs courtesy of Harry Styles, Hozier, Lana Del Rey, Prince, Rihanna, and Yarbrough & Peoples.

- About The Musical Hype

- Mini Playlists

- Bangerz N Bopz 🔥

- Throwback Vibez 🕶️🎶

- Midnight Heat 🕛 🔥

- Controversial Tunes 😈🎶

- Music Lifts 🎶 🏋

- Head 2 Head 🗣️

- 1 Hit WONDERful 👏👏👏

- Interviews / Q&As

- Music Submissions

- Privacy Policy

- Search for:

- Our Year So Far

- New Arrivals 166

- Not In Paris

- Highsnobiety HS05

- New Balance

- Acne Studios

- Dries Van Noten

- Stone Island

- Carhartt WIP

- Entire Studios

- All Clothing

- All Footwear

- Hiking Sneakers

- All Accessories

- Winter Accessories

- All Objects

- Collectables

Daniel Caesar Struggles to Find His Footing on 'CASE STUDY 01'

It’s been an interesting year for Canadian R&B star Daniel Caesar , one that has been riddled with more controversy than actual music-making. First there was the moment he was called “very gay” by legendary comedian (and very stoned) Dave Chappelle while the two were guests on John Mayer’s Current Mood show. The pair’s subsequent argument, recorded live on Instagram , was a cringe thing to sit through. Then there were his comments supporting divisive industry insider YesJulz, an influencer who has spurned outrage due to her ‘blaccent’ , in addition to being seen in T-shirts that have the N-word written on them. Caesar passionately defended her but was later forced to apologize after calling black people “too sensitive” and insinuating that a victim mentality prevents many of them from making money.

It would be a stretch to assume this hasn't flattened the buzz around his second studio album, CASE STUDY 01 , which arrives with a more of a whimper than a bang — a real shame given how brilliant his 2017 debut Freudian , an intricate soul record that found the beauty in both falling in and out of love, remains. Yet in the fickle world of music, artists can get away with saying just about anything so long as the songs are good; something the talented Caesar will be acutely aware of.

It's fair to say this isn’t a record that will blow you away enough to consider forgetting Caesar’s recent spate of problematic behavior. The first half of CASE STUDY 01 is wildly inventive, filled with sexy slow jams and funky introspection, but the second half is indulgent verging on the pretentious, and proof Caesar is still far from the finished product.

The creative way Caesar switches from a high to low falsetto on the funky “ENTROPY” is a reminder of his boundless vocal talent. Meanwhile, Brandy duet "LOVE AGAIN" will take you right back to the slow jams of the '90s. The pair’s chemistry is really fun to sit through, and it's destined to become a hit single. “FRONTAL LOBE MUZIK” (on which Pharrell provides backing vocals) is a sizzling slice of summer, and the synths that kick in will give you that same transcendent feeling of hearing Kool & the Gang’s “Summer Madness” on a deckchair in August. The track is also the closest Caesar comes to underdog relatability on the project, as he croons: “Used to steal all my groceries/ now I get to the racks.”

I say this because there’s a misogynist tone to a lot of the other lyrics here, with Caesar unconvincingly playing the role of the gangster heartbreaker. Lyrics such as “It's you baby girl I'm trying to breed/ I'm not a monster/ I'm just a man with needs” on "CYANIDE" border on chauvinism. It’s weird hearing a singer who was once so empathetic to women suddenly sounding so dismissive of them — it’s almost as if he’s doing absolutely everything he can to convince Chappelle that he’s straight, with a lot of the sex talk here, which includes making love to a woman on a piano (“OPEN UP”), feeling clichéd at best, reminiscent of even more unsavory hallmarks of the genre at worst.

The second half of the album takes on a much more experimental, psychedelic tone, but Caesar is at his best when he’s having fun and not overthinking it, with a lot of these latter tracks sounding like a discount store version of far edgier artists such as Moses Sumney and Frank Ocean. “SUPERPOSITION” is incredibly indulgent, with its attempts at being philosophical (at one point, Caesar, without a hint of irony, sings the lyrics: “Life's all about contradiction/ Yin and yang/ Fluidity and things") sounding like it was inspired by the inside of a fortune cookie. The minimalist guitar of "RESTORE THE FEELING" also isn’t nearly as interesting as Caesar clearly thinks it is, with the song feeling muddled and undercooked.

Perhaps the most telling track on the album is “COMPLEXITIES,” a drugged out diary entry that sounds more like a demo than anything fully formed. Descending into hopelessness, Caesar sings: “I don’t give a damn because it doesn’t make a difference” - bars that inevitably provide an insight into his current world view. If Caesar starts to offer more by album number three, he could yet consolidate his obvious talent into something enduring, but if it’s another record created just for the sake of it, then many of the people who once believed in Caesar might feel like it’s time to move on.

There’s nothing truly terrible here, but - beyond Brandy rolling back the years - there’s nothing that will make you reach for the replay button either. It’s okay, but after the year Caesar has had, okay just won’t do.

Listen to Daniel Caesar's 'CASE STUDY 01' here . For more of our album reviews, head here .

CASE STUDY 01

After Daniel Caesar released his soul-baring debut album, Freudian, tracing his decision to leave home and the church at 17, he became one of R&B’s most promising poets, able to distill spiritual complexities into deceptively simple love songs. Then, he got lost in his own head. “I got pretty depressed,” he tells Apple Music, citing artistic pressure, social media, and the isolation of fame as factors. “For a while, I didn’t want to leave my house.” The thing that ultimately freed him from his creative rut was finding comfort in his own mortality. “Everything dies, everything changes—I had to embrace that,” he says. “To not be so scared of failure.” CASE STUDY 01, his existential follow-up, is denser, headier, and riskier, confronting ideas like good and evil, life and death, loneliness, and God. “I’m drawn to touchy subjects,” he says. “They’re my favorite.” He found he kept circling back to themes of death and spirituality. “I’d been reading a lot about Judaism and Kabbalah and meditation. And I was raised religious, so it’s like my operating system,” he says. “But I also needed to free myself from that—to live.” Once he’d regained some creative confidence, he drafted a fantasy lineup of artists to work with on the new music—Pharrell, Brandy, John Mayer. “These are my heroes,” he says. “People who I never thought I’d ever collaborate with, until the opportunity came up and it was like, ‘Is this really real?’” Even more surprising, perhaps, was the degree to which the studio sessions felt like true artistic exchanges. “There were obviously things I admired about these artists,” he says, “but I realized there were also things they admired about me.” Pharrell was drawn to Caesar’s palette of influences—a mix of gospel, R&B, rock, and soul—while Caesar hoped he’d absorb some of Pharrell’s signature playfulness. “I take myself very seriously,” he says, “and there’s something so childlike and fun about his music.” Similarly, Mayer, his all-time favorite artist, was interested in seeing how Caesar pieced lyrics together: “He liked what I say and how I say it.” “SUPERPOSITION” perfectly marries their mutual love of romantic, tuneful melodies and densely layered production. “I wanted a song that could’ve fit on [Mayer's 2006 album] Continuum,” Caesar says. “But, you know, right on the edge.”

June 28, 2019 10 Songs, 43 minutes ℗ 2019 Golden Child Recordings

More By Daniel Caesar

Featured on.

Apple Music Hip-Hop

Apple Music R&B

Apple Music

You Might Also Like

Frank Ocean

Brent Faiyaz

Summer Walker

Africa, Middle East, and India

- Côte d’Ivoire

- Congo, The Democratic Republic Of The

- Guinea-Bissau

- Niger (English)

- Congo, Republic of

- Saudi Arabia

- Sierra Leone

- South Africa

- Tanzania, United Republic Of

- Turkmenistan

- United Arab Emirates

Asia Pacific

- Indonesia (English)

- Lao People's Democratic Republic

- Malaysia (English)

- Micronesia, Federated States of

- New Zealand

- Papua New Guinea

- Philippines

- Solomon Islands

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

- France (Français)

- Deutschland

- Luxembourg (English)

- Moldova, Republic Of

- North Macedonia

- Portugal (Português)

- Türkiye (English)

- United Kingdom

Latin America and the Caribbean

- Antigua and Barbuda

- Argentina (Español)

- Bolivia (Español)

- Virgin Islands, British

- Cayman Islands

- Chile (Español)

- Colombia (Español)

- Costa Rica (Español)

- República Dominicana

- Ecuador (Español)

- El Salvador (Español)

- Guatemala (Español)

- Honduras (Español)

- Nicaragua (Español)

- Paraguay (Español)

- St. Kitts and Nevis

- Saint Lucia

- St. Vincent and The Grenadines

- Trinidad and Tobago

- Turks and Caicos

- Uruguay (English)

- Venezuela (Español)

The United States and Canada

- Canada (English)

- Canada (Français)

- United States

- Estados Unidos (Español México)

- الولايات المتحدة

- États-Unis (Français France)

- Estados Unidos (Português Brasil)

- 美國 (繁體中文台灣)

- CASE STUDY 01

- Daniel Caesar

CASE STUDY 01 Tracklist

Entropy lyrics, cyanide lyrics, love again by brandy & daniel caesar lyrics, frontal lobe muzik (ft. pharrell williams) lyrics, open up lyrics, restore the feeling (ft. jacob collier & sean leon) lyrics, superposition (ft. john mayer) lyrics, too deep to turn back lyrics, complexities lyrics, are you ok lyrics.

Nearly two years on from delivering his celebrated studio debut Freudian , Daniel Caesar returned with his second studio album, CASE STUDY 01 .

The arrival of the album was first teased on social media, sharing a cryptic video of a figure walking through a barren desert, set to the opening track ENTROPY . A listening party was held on the 4 days prior to its release for 200 guests and industry figures.

“CASE STUDY 01” Q&A

What has the artist said about the album.

Regarding the period that follows the release of his debut album : - “I got pretty depressed. For a while, I didn’t want to leave my house” - “Everything dies, everything changes—I had to embrace that. To not be so scared of failure.”

Regarding the themes and subjects addressed by the album: - “I’m drawn to touchy subjects. They’re my favorite.” - “I’d been reading a lot about Judaism and Kabbalah and meditation. And I was raised religious, so it’s like my operating system. But I also needed to free myself from that—to live.”

Regarding the collaborators on the album: - “These are my heroes. People who I never thought I’d ever collaborate with, until the opportunity came up and it was like, ‘Is this really real?’” - “There were obviously things I admired about these artists, but I realized there were also things they admired about me.”

- Daniel Caesar via Apple Music

Album Credits

NEVER ENOUGH (Deluxe)*

Never enough (bonus version).

- CDs & Vinyl

Sorry, there was a problem.

Image unavailable.

- Sorry, this item is not available in

- Image not available

- To view this video download Flash Player

CASE STUDY 01 Explicit Lyrics

| Listen Now with Amazon Music |

| Amazon Music Unlimited |

| New from | Used from |

| — |

| — |

| Vinyl, Explicit Lyrics, December 13, 2019 | — | — |

- Streaming Unlimited MP3 $7.99 Listen with our Free App

- Audio CD from $10.72 5 Used from $10.72 22 New from $11.82

- Vinyl from $99.99 1 Collectible from $99.99

Track Listings

| 1 | Entropy |

| 2 | Cyanide |

| 3 | Love Again |

| 4 | Frontal Lobe Muzik (Feat. Pharrell Williams) |

| 5 | Open Up |

| 1 | Restore the Feeling (Feat. Sean Leon and Jacob Collier) |

| 2 | Superposition (Feat. John Mayer) |

| 3 | Too Deep to Turn Back |

| 4 | Complexities |

| 5 | Are You Ok? |

Editorial Reviews

Grammy Award-winning R&B singer/songwriter Daniel Caesar releases his second full-length album, Case Study 01. He introduces the record with lead single "Love Again" and over a smoky beat enhanced by swells of guitar and keys, he locks into a heavenly and hypnotic harmony with none other than the legendary Brandy. These two voices merge their respective eras of R&B and deliver a blockbuster timeless collaboration steeped in sweet soul. It hinges on a redemptive and real refrain, "If you can take my hand, I promise we'll find love again." Additional guests include Pharrell Williams, John Mayer, Sean Leon and Jacob Collier. The album as a whole represents Caesar's continued evolution as one of R&B's most undeniable outliers.

Product details

- Product Dimensions : 12.1 x 12.3 x 0.3 inches; 12 ounces

- Manufacturer : Golden Child Recordings (Daniel Caesar)

- Original Release Date : 2019

- Date First Available : October 18, 2019

- Label : Golden Child Recordings (Daniel Caesar)

- ASIN : B07Z75QZ6Y

- Number of discs : 1

- #20,468 in Pop (CDs & Vinyl)

Videos for this product

Click to play video

Customer Review: Love it

Spaceodditykelly

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

Reviews with images

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- About Amazon

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell products on Amazon

- Sell on Amazon Business

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Become an Affiliate

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Make Money with Us

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Amazon and COVID-19

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

- Harvard Business School →

- Faculty & Research →

- July 2008 (Revised January 2012)

- HBS Case Collection

Enterprise Risk Management at Hydro One (A)

- Format: Print

- | Pages: 22

More from the Author

- Winter 2015

- Journal of Applied Corporate Finance

When One Size Doesn't Fit All: Evolving Directions in the Research and Practice of Enterprise Risk Management

- August 2014

- Faculty Research

Enterprise Risk Management at Hydro One (B): How Risky are Smart Meters?

Learning from the kursk submarine rescue failure: the case for pluralistic risk management.

- When One Size Doesn't Fit All: Evolving Directions in the Research and Practice of Enterprise Risk Management By: Anette Mikes and Robert S. Kaplan

- Enterprise Risk Management at Hydro One (B): How Risky are Smart Meters? By: Anette Mikes and Amram Migdal

- Learning from the Kursk Submarine Rescue Failure: the Case for Pluralistic Risk Management By: Anette Mikes and Amram Migdal

(918) 664-7822

- Hairpin Heat Exchangers

- Finned Coils and Heaters

- Suction and Line Heaters

- Plug-n-Play

- Spare Parts

- Oil and Gas

- Power Generation

- Food and Beverage

- International Representatives

- Domestic Representatives

- Representatives by State

- Case Studies

Case Study 001: REGEN GAS HEATER Hairpin Heat Exchanger vs. BEM Style Shell and Tube

A Regen Gas Heater is used to help de-water natural gas. Natural gas is normally saturated with water that can cause problems and damage to equipment and components. It’s necessary for the gas to go through a dehydration process. Moisture and hydrocarbons in the gas are absorbed by using dewatering agents or desiccants. When the desiccants become overly saturated with moisture and hydrocarbons, a Regen gas heater or reboiler vaporizes the moisture and hydrocarbons to dry the desiccants.

CASE STUDY 001

The BEM Style S&T Exchanger requires an expansion joint to deal with temperature differentials. When the 1400psi HP gas tubeside leaked into the hot oil shellside, the expansion joint was immediately compromised. In this case study the process plant was shut down due to a safety violation, creating a 5-week loss of production, not to mention rework costs.

The safest and most efficient choice for this service is a Hairpin Heat Exchanger. Our design allows the tubeside to naturally expand and contract with differentials in temperature, therefore, the shellside is not affected by the temperature on the tubeside. Due to its unique design the HPHX is safe and durable for these service conditions.

One of the Largest Manufacturers of Hairpin Heat Exchanger Lines in the United States

Download the PDF version of Case Study 001

MUSIC JUSTICE /

Case study 001 – intimate music versus atlantic records inc.

Case presented by: Errol Michael Henry

In 1997 I was running my independent record label (Intimate Music) from my studio in Northwest London. I had a couple of artists signed to major labels, releases coming out on the label, plus new artists in development. I received a call from Paul Samuels (UK A&R Representative for Atlantic Records) requesting a meeting with me. He came over to studio the following week and told me that he worked for Craig Kallman who ran the entire A&R division for Atlantic Records from their Head Office in New York. Paul wanted to hear the new music I was working on to see if anything I had might be of interest to Craig. I had been working on a gospel album with a recently formed all-girl group and when the song I had written for them came on, Paul declared: “That’s a smash hit!” He asked for a copy to send to Craig – a request I refused, as I was not interested at that point in handing over my music to people I didn’t know nor had any working relationship with.

The following week Paul called me again to tell me that Craig was in the UK and was keen to hear the song. I went to the Atlantic Records office in Kensington and met with Craig. He heard the song and immediately agreed with Paul’s view that it was a ‘hit’ and urged me not play it to anyone else. He told me that he wanted not only to sign the group, but to create a joint venture between my company and Atlantic Records. Having grown up listening to the likes of Chic, Roberta Flack, Otis Redding and Aretha Franklin, it’s not difficult to understand why I was really happy at the prospect of such an alliance. Once the framework of the deal was agreed, it was clear that I could not deliver the work required and continue to manage the other projects I was involved with, so based on the assurances I had received from Craig (especially in regards to future projects) I withdrew from the other arrangements that had previously provided much of my income.

Craig recommended that I use Fred Davis, a well-known music industry lawyer who was also based in New York, as he had plenty of experience doing deals with Atlantic and would help to smooth the path to completion. The deal involved 3 parties (True Solace, Intimate Music and Atlantic Records) and required the creation of complex legal documents, which took a considerable amount of time to resolve. After months of wrangling, we were ready to sign. I noted that some of the promises Craig had made to me in person hadn’t made it into the final draft of the agreement, but during another meeting in London he told me not to worry and that such was his influence within Atlantic Records, his word carried even more weight than anything that could be written down on paper – guarantees that later proved to be utterly worthless .

The Shakedown

Once the deal was signed in February 1998, I devoted every waking hour to writing and producing the music required to complete the album. I often worked 7 days a week and refused all offers from other companies to take on projects for them because I was totally committed to making my arrangement with Atlantic work and didn’t want anything else to get in the way. I travelled to New York in the autumn of 1998 to complete the mixing process and then to Los Angeles to oversee the mastering. By January 1999, the creative process was complete and it was time to set-up the marketing and release schedule. To this end, I was invited to meet Val Azzoli (President of Atlantic Records), Armhet Ertegun (founder of Atlantic Records) and various other Heads of Departments. Armhet Ertegun told me that the record I had delivered was one of the finest recordings he’d ever heard and was proud to have it on the label, which was an endorsement that seemed to vindicate all of the hard work and effort it had taken to get the album finished.

Craig Kallman has cultivated an image as ‘the musician’s friend’ but my experiences with him tell an entirely different story. Having already approved the record for commercial release, agreed the final artwork and set a release date, he made a move that left me utterly stunned. He called me and told me that he wanted me to change the lyrics to ‘Thank You’, which was the song that had been chosen as the lead single to promote the album. What made this request so perplexing is that on a visit to London, I had played the song to Craig at my studio and he has declared it to be potentially one of the biggest records in the history of the label. He went on to say that he’d personally compel the people charged with radio promotions to ensure that the song was given ‘priority status’ which I was obviously pleased to hear.

So why was Craig now asking me to do what he knew I could never agree to? ‘Thank You’ was written for the sole purpose of expressing my gratitude and an open expression of my faith, so to ask me remove such references was as disturbing as it was calculated. During the call Craig told me in no uncertain terms that if I didn’t do as he asked, he would set in motion a series of events that would damage me in ways that I could not begin to imagine. At the time I simply could not understand why this was happening. I later learned that there were all sorts of inter-departmental politics in play – corporate back stabbing that had nothing whatsoever to do with me.

I came to realise that Craig Kallman’s insistence that I remove the most important lyrics, from what everyone concerned agreed was the most influential and commercially viable song, was a power play and had I agreed, it would have led to my decent into an on going series of compromises. I have been around this business long enough to know that once you start down that road, there’s always ‘one more thing’ that people demand of you that leads to ‘yet another thing’ and before you know it – you’ve sold your soul for a price. This idea was proven beyond doubt during that fateful call. Craig named several household names that had achieved fame and fortune by ‘selling out’ and simply could not understand why I would not follow suit. When gentle persuasion failed to have the desired effect, direct threats soon followed but my answer remained the same: “No.”

The Penalty

Timing is everything in life and Craig knew that I had invested all of my time, all of my creative energy, all of my money and the future of my company in this record. He had timed his play to coincide with the point of the process when he perhaps believed that I would compromise because I had too much to lose and would simply fall into line – as so many before me had willingly done . Kallman warned me that all of the good will that had been built around the project within Atlantic Records would be cancelled out at his command and in this regard he was true to his word. My commitment to the True Solace project had led to my company being entirely dependent on the revenue coming from my Atlantic deal, plus the associated deal with Warner Chappell Music Publishing (another company within the Warner Music Group who also own Atlantic Records). Mr Kallman’s message was very clear indeed: “Do what I say or face the consequences.”

The album came out in August 1999 with little fuss or fanfare. The promised withdrawal of marketing and promotional support meant that the record stood no chance of success and soon disappeared without a trace. I was devastated, angry and distraught that supposedly professional people could behave in such a callous way, but this is typical behaviour within the music business and represents a cruel attitude to artistic people that I am determined to expose. Atlantic Records wrote off the money they had spent on the project up to that point but the fiscal losses were not an issue for them. They cared nothing for the deep hurt their actions would inflict on me and the other creative contributors to the project. I had given up all of my other income sources and the members of the group had all given up their jobs in order to complete the album – all for nothing . More than 2 years of work, hundreds of hours of writing, recording, editing and mixing were to be thrown away and forgotten.

I called Craig Kallman at his home to express my surprise and displeasure at what had transpired and he said: “I am in a battle with Ron Shapiro to become President of the label and I’ll do whatever I need to do in order to make that happen. I saw an opportunity to get out of the deal so I took it.” I also asked him about the personal assurances he had given me and about the promises of future projects – he hasn’t answered me to this day. I was simply collateral damage in a high stakes game being played by a man who demonstrated to me beyond doubt that he cannot be trusted.

It was the stated intention of Atlantic Records to simply walk away from their commitments and leave me fiscally destitute and with my music eternally locked up in their vaults. I called Fred Davis (the attorney who had originally negotiated the deal) who promptly advised me that he could not comment nor act on the matter because he was also Craig Kallman’s personal lawyer and was legally ‘conflicted’. It transpires that he’d been Craig’s lawyer throughout the period he acted for me yet had no problem relieving me of thousands of dollars in legal fees! In that moment I better understood why Fred and his associates had advised me against inserting key clauses that I felt were necessary to protect my interests.

There had been specific stipulations inserted into the agreement at my behest – clear legal requirements that Atlantic Records failed to comply with. The contract had provisions to rectify any ‘breaches’ within a predetermined period of time. Atlantic Records had not ‘healed’ the relevant breaches within the time allocated, so I pointed these breaches out to Craig who told me that although he was well aware of them, they were no longer his concern and that the matter was now in the hands of others.

I received a call from Atlantic’s legal department informing that they had no plans to make restitution or settle with me in any way. They advised me that if I had the means, money or time, I could take them to court and would definitely win – as there were clear breaches of the agreement that could not be repaired. What came next was quite chilling. During this period of time, Time Warner (then the parent of Warner Music) was in the middle of a multi-billion dollar merger with AOL. I was told that a fund has been set-aside to fight all of the legal cases arising from recording agreements (including mine) that had been summarily terminated outside of proper protocol. I was warned that most of the most reputable legal firms with the expertise and skill to fight my case had been put on retainer by Atlantic Records, which meant that they could not be hired to represent victims of contractual breaches.

The Legal Shenanigans

I didn’t believe that any company could be quite so brazen so I asked my lawyers here in the UK to recommend 3 legal firms based in New York who were suitably qualified to fight cases at this level. I called all three companies and on each occasion, the lawyer on the other end of the line, asked for details of the case before declaring themselves ‘conflicted’ because they had already been retained by Atlantic Records. Another firm I spoke to originally agreed to take my case only to call back the next day to tell me they too had been retained by Atlantic Records, but had no idea why! I clearly had a simple choice to make: fight or walk away empty-handed .

Silda Palerm (a litigator working for Atlantic’s legal department) had told me quite openly of Atlantic’s intention to ‘starve me out.’ They knew that I had overheads to meet and with the immediate loss of funding, I would simply collapse into financial ruin. I knew that I could not afford to sue Atlantic in a New York court. I also knew that I simply couldn’t just let them walk away scot free – having treated me worse than a rabid dog. My own lawyers here in the UK advised me that there was no chance of winning a legal battle with Atlantic due to the logistics and costs involved – so I sacked those lawyers immediately . I started selling personal assets including rare musical instruments so that I could provide food for my family and to keep my phone lines working – such was the extent of the damage that Atlantic Records were inflicting on my life.

Things dragged on for what seemed like an eternity because Atlantic Records proved quite expert at stalling, avoiding phone calls and generally evading me wherever possible. I realised that I needed to take more drastic action. My recording studio was my most prized possession and also my most valuable asset. I knew that selling it would enable me to raise sufficient funds to fight on a little longer, but would also result in me losing the very means by which I made my living. With a heavy heart, I set about selling off all of my equipment (taking huge losses along the way) until nothing was left. The mental picture of the (now) empty room where my purpose designed facility used to be will stay with me until my dying day. I had built that place from being a rundown dilapidated ruin into a state-of the-art studio and now I had torn it all apart – just to get Atlantic Records to do the right thing .

The back and forth between me and Atlantic’s legal department went on for months before I decided to write to Val Azolli and let him know that since the forthcoming merger stood to earn all of the senior executives at Atlantic millions of dollars in share options, I would do everything in my power to alert the media and all other authorities to what was going on with me. 48 hours later, I received another call from Atlantic’s legal department who were ready to reach some kind of settlement. My music was what I had before Atlantic Records ever came into my life so getting it back was pivotal to me . I was told in no uncertain terms that such an outcome was simply impossible as Atlantic had never in its history returned copyrights and doing so would set a dangerous precedent. I didn’t care – I wanted my music back and would not countenance any deal that did not result in its return.

After yet more arguments, offers and counter-offers, Atlantic finally relented and agreed to return my recordings to me which meant that I got a lot less cash up front, but the matter would be put to bed. A fully executed agreement arrived nearly six months after the contract had originally been terminated and I was ready to move on with my life, but the settlement was conditional on me signing a ‘non disclosure agreement’ (NDA). The document required me not suggest that there had been any breaches at all. In effect, the settlement required me to pretend that everything I had been through did not happen .

In all honesty by that point, my health was suffering and months of dealing with extreme levels of stress and coping with severe fiscal hardship had taken its toll. I was concerned for the well being of my family and honestly had no idea how I would provide for them, so I signed the NDA.

The Aftermath

I had done everything that was required of me under the terms of my agreement with Atlantic Records – and much more. I worked tirelessly, travelled back and forth across the ocean to make sure that I had done everything possible to ensure the success of the music I had invested so heavily in. The general public (understandably) have no idea of just how much is required from creative people in order to get their music made, marketed and sold. Countless meetings with music executives, dealing with ‘money men’ in the boardroom, radio promoters, press officers, lawyers and various other related personnel – and that’s before a single note is written or recorded. Dealing with all of that stress was difficult enough, but realising that is was all for nothing due to broken promises, is something that I am still recovering from.

Would I ever commit so much emotionally, creatively, or fiscally to anyone else ever again? – Absolutely not. I can’t get back the effort I expended, the years I wasted, or the money I lost. I am still coming to terms with the sheer scale of the disappointment, pain and circumstantial losses I endured as a result of the way that Atlantic Records behaved towards me. It is very difficult to properly articulate to anyone else just how low I got during that period. I was totally isolated. There was no available work, no money and no means to record new material – since the tools of my trade had all been sold off on the cheap.

In one calendar year I lost all of my most valued possessions, including my unique Gibson Les Paul guitar, my vintage keyboards, plus custom made, irreplaceable sound equipment. I lost my recording studio, my office facility and was forced to sell off my cars at knocked down prices. My sense of well being plummeted and feelings of despair totally enveloped me. It took me many years even to accept that I was a victim of wrongdoing and being forced to remain silent by virtue of an NDA that I now consider legally and morally redundant – just made the whole experience even worse. I have come to realise that I must lead by example. My NDA must serve a higher purpose and breaking it is absolutely necessary if other creative people who have suffered similar fates to mine, are to gain the confidence to speak up. It is imperative that they feel able to tell their stories and to share their experiences without fear of reprisals from those who seek to confine them within intimidating walls of silence.

Prior to my horrific encounter with Atlantic Records, I was a prolific songwriter and producer. In the years that passed since they devastated my business I could not even listen to music, let alone make it . I couldn’t write anything, I didn’t want to play any musical instruments, or to produce music at all. The very thing I had once loved, now haunted me like a ghost. It’s difficult to make sincere music if you don’t love it and it’s hard to love it when untrustworthy people ‘infect’ the creative process with their devious endeavours. It has taken many years for my scars to heal and now emboldened with the knowledge that they’ve done their worst, but they didn’t finish me – I have resolved expose their evil ways for all the world to see. Companies like Atlantic Records love to do their dirty dealings in secret while selling an entirely different ‘face’ to the wider world. I’ve seen what goes on behind the scenes and I can say with experiential insight: “don’t believe the hype.”

I believe that everything happens for a reason and I know now (what many others have yet to discover) that dealing with companies like Atlantic Records is like dicing with death. They don’t necessarily kill you in actuality, but they do ‘murder’ your creative endeavour – which is in some ways far worse. I have had a lot of time to consider the events that unfolded and plenty of time to draw conclusions. I am finally ready to admit that I was severely wounded by wicked people who sought to do me harm. I was promised retribution if I did not surrender my beliefs and the aftermath was every bit as destructive as Kallman had assured me it would be. He is still propagating his ‘friend of the artist’ spiel to anyone who will listen, but I know who he really is, I know who he really works for and I know from personal experience what he really does to people given half-a-chance .

I have no intention of slandering anyone nor does Music Justice seek to assert false allegations against anyone. My purpose in speaking out at this time is simply to warn others about what goes on in this business beyond the glamorous ‘sheen’ that is proven so seductive to so many people. It is my duty to warn people about the reality of dealing with an industry that regards human beings as ‘tradable assets’ and contracts as worthless pieces of paper – when it suits their own corporate interests. I cannot realistically expect others to open their hearts and share experiences that might still have a great deal of pain attached, unless I first acknowledge what I went through and explain how awful the whole experience made me feel.

I wish I could tell you that individuals like Craig Kallman are one-offs – alas, I have seen the likes of him many times before and quite a few times since. The music industry willingly makes room for liars, thieves, manipulators and people of dubious moral character. It promotes them, rewards them, ennobles them and protects them from the consequences of their misdeeds. It is highly probable that both Craig and Atlantic Records thought they’d seen the last of me once the settlement agreement (and the silence enshrined within it) had been signed – they are about to discover that they were as wrong about me as I was about them . I have recently published another case related to Atlantic Records/Warner Music because despite the hell they originally put me through – they came back for a second helping a few years later . Read it here .

Sign up for the Music Justice Newsletter and we’ll send you the next case study the moment it leaves the presses.

- Open access

- Published: 02 July 2024

A naturalistic study of plasma lipid alterations in female patients with anorexia nervosa before and after weight restoration treatment

- Alia Arif Hussain 1 , 2 ,

- Jessica Carlsson 2 , 3 ,

- Erik Lykke Mortensen 4 , 5 ,

- Simone Daugaard Hemmingsen 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ,

- Cynthia M. Bulik 10 , 11 , 12 ,

- René Klinkby Støving 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 &

- Jan Magnus Sjögren 1 , 13

Journal of Eating Disorders volume 12 , Article number: 92 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

68 Accesses

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

Plasma lipid concentrations in patients with anorexia nervosa (AN) seem to be altered.

We conducted a naturalistic study with 75 adult female patients with AN and 26 healthy female controls (HC). We measured plasma lipid profile, sex hormones and used self-report questionnaires at admission and discharge.

Total cholesterol (median (IQR): 4.9 (1.2)) and triglycerides (TG) (1.2 (0.8)) were elevated in AN at admission (BMI 15.3 (3.4)) compared with HC (4.3 (0.7), p = 0.003 and 0.9 (0.3), p = 0.006) and remained elevated at discharge (BMI 18.9 (2.9)) after weight restoration treatment. Estradiol (0.05 (0.1)) and testosterone (0.5 (0.7)) were lower in AN compared with HC (0.3 (0.3), p = < 0.001 and 0.8 (0.5), p = 0.03) and remained low at discharge. There was no change in eating disorder symptoms. Depression symptoms decreased (33 (17) to 30.5 (19), ( p = 0.007)). Regression analyses showed that illness duration was a predictor of TG, age was a predictor of total cholesterol and LDL, while educational attainment predicted LDL and TG.

Lipid concentrations remained elevated following weight restoration treatment, suggesting an underlying, premorbid dysregulation in the lipid metabolism in AN that persists following weight restoration. Elevated lipid concentrations may be present prior to illness onset in AN.

Level of evidence: III

Evidence obtained from well-designed cohort or case–control analytic studies.

Plain English summary

Fat is essential for the human body. Too much fat in the blood can be a sign of underlying illness including heart disease. This study investigated how plasma lipids (fats) are affected in individuals with anorexia nervosa (AN). We included 75 adult female individuals with AN and 26 healthy female controls, and measured lipids, sex hormones, and used questionnaires upon admission and discharge from treatment. We found that low-weight individuals with AN had higher lipids than the healthy controls, and these lipids remained elevated after weight restoration treatment. Additionally, individuals with AN had lower levels of sex hormones (estradiol and testosterone) at their low weight, and they stayed low even after weight restoration treatment. Eating disorder symptoms remained unchanged, but depression symptoms decreased during treatment. In conclusion, the study suggests that individuals with AN have changes in their lipid metabolism, which persists even after weight restoration treatment. We don’t know the reason behind these elevated lipids, and therefore, this should be investigated further in future study.

Introduction

Anorexia nervosa (AN) has one of the highest mortality rates of all psychiatric disorders [ 1 ]. AN is characterized by restricted food intake, resulting in low body mass index (BMI) [ 2 ]. Accompanying symptoms include fear of weight gain, aversion to foods rich in fat and sugar, excessive exercise, distorted body image, and an inability to recognize the seriousness of the low weight.

Evidence for effective treatment strategies is lacking especially in adults [ 3 ] and chronicity in AN has been reported to be as high as 33% [ 4 ]. Furthermore, as the etiology of AN remains largely unclear, we urgently need a better understanding of the etiology and pathophysiology of AN to identify effective treatments.

A recent genome-wide association study has identified eight risk loci associated with AN risk, and single nucleotide polymorphism based genetic correlations suggest that AN has both psychiatric and metabolic components [ 5 ]. Moreover, a significant positive genetic correlation between AN and elevated high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol has been reported, while there was a negative genetic correlation with fat mass, fat-free mass, BMI, obesity, type 2 diabetes, fasting insulin, insulin resistance, and leptin [ 5 ].

Likewise, decades of clinical research have provided evidence for elevated lipid concentrations in the majority of patients with AN, mirroring the recently reported significant genetic correlations [ 6 ]. However, only few longitudinal studies measure lipid concentrations during weight restoration. These studies included small samples and reported conflicting results. Some studies found normalized lipid concentrations following (partial) weight restoration, whereas others found persistently elevated concentrations [ 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ]. Follow-up was 1–14 months across these longitudinal studies and two studies investigated lipids in fully weight recovered patients with sample size n = 21 [ 17 ] and n = 5 [ 12 ], respectively. Matzkin et al. included a 4-month follow-up (median BMI increased from 18 to 20 kg/m 2 ) and found significantly elevated total cholesterol at baseline in AN compared with healthy control participants (HC), and total cholesterol non-significantly decreased at follow-up in the AN group. Mordasini et al. followed-up the patients with AN after 14 months with BMI increasing from 13.1 to “original weight” without further specifications on the follow-up BMI. Likewise, this study found significantly elevated cholesterol concentrations in the AN group at baseline compared with HC; however, after weight restoration, cholesterol concentrations normalized/decreased again.

The high mortality rates for AN are related to both severe somatic complications and suicidality [ 1 , 18 ]. Altered lipid concentrations have also been reported in individuals with higher suicidality risk in both AN [ 19 ] and in other psychiatric illnesses [ 20 ] which, furthermore, could be influenced by the changes in serotonin system functionality found in individuals with higher suicidality risk and in victims of suicide [ 21 ].

Numerous other endocrine and metabolic changes have been reported in low-weight individuals with AN, and most of these changes seem to be adaptive in the state of malnutrition and underweight [ 22 ]. These alterations include amenorrhea and sex hormone changes. It has been suggested that irregularities in the menstrual cycle could be explained by changes in lipid concentrations affecting metabolism and steroid hormones, i.e. estradiol, a precursor to cholesterol [ 23 ]. Blood estradiol concentrations are usually decreased in AN. Endogenous estradiol appears to be cardioprotective, and studies of postmenopausal estradiol deficiency [ 24 ] show associations with adverse changes in metabolic risk factors [ 25 ]. A small (n = 18) cross-sectional study in individuals with AN also observed a shift to more atherogenic lipoprotein subclasses [ 26 ]. Furthermore, a recent lipidomic study investigating adolescents with AN before and after weight restoration (from BMI 15 to 19.5) points towards lipid dysregulation with similarities to obesity and other features of the metabolic syndrome despite the low weight of the patients with AN [ 27 ]. A similar investigation of the lipidome in an adult population with AN pointed in the same direction [ 28 ]. Persistently elevated lipid concentrations were reported in a study investigating long-term outcomes from a 10-year follow-up of women living with AN of the restrictive subtype according to The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edition (DSM-5) [ 29 ], although longitudinal studies with larger sample sizes would improve the level of evidence for this finding.

The longitudinal investigation of lipid concentrations and sex hormones in AN could reveal the underlying pathophysiology by determining whether the observed alteration in lipid concentrations is a merely a consequence of starvation (state-related), or part of an actual premorbid illness mechanism /trait-related). Further clarification of the role of lipids and sex hormones in AN in large longitudinal studies could help identify mechanisms underlying AN, and ultimately, lead to better treatment options and decrease in mortality.

We hypothesized, that (1) plasma lipid concentrations would be elevated in patients with AN pre-treatment compared with HC, whereas sex hormones would be lower; (2) plasma lipid concentrations would remain elevated after weight restoration treatment (measured at discharge); (3) plasma lipids concentrations would be higher in patients with longer illness duration and with severe eating disorder and depressive symptoms.

Therefore, the objectives of the present naturalistic study were to (1) compare plasma lipid and sex hormone concentrations in individuals with AN and in healthy controls; (2) compare plasma lipid and sex hormone concentrations before and after weight restoration treatment in individuals with AN; (3) explore age, BMI, AN subtype, illness duration, education level, and eating disorder and depression symptoms as predictors of lipid concentration in individuals with AN.

Materials and methods

This study is part of the naturalistic PROspective Longitudinal all-comers inclusion study in Eating Disorders (PROLED) [ 30 ] at Mental Health Centre Ballerup, Denmark, and includes patients and controls enrolled between 2016–2020. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03224091. All patients attending a pre-treatment assessment for eating disorders at Mental Health Centre Ballerup are offered to participate in the PROLED-study if they fulfill the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

The recruitment of patients with eating disorders for the overall PROLED-study started the 10th of January 2016 and is planned to continue for 10 years. The PROLED inclusion criteria for patients are: Eating disorder diagnosis according to DSM-5 (AN, bulimia nervosa, binge-eating disorder, avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), and eating disorder not otherwise specified), female or male sex assigned at birth, and ages between 18–65 years. Exclusion criteria are: Involuntary treatment. Patients were recruited from the in- and outpatient departments and day hospital for eating disorders.

The inclusion criteria for HC are: Female or male sex assigned at birth, BMI in the normal range, and ages between 18–65 years. Exclusion criteria: Any sign of a disorder, mental or physical, as judged by the physician after a complete health investigation. Healthy volunteers were recruited from advertisements in newspapers and from the PROLED website.

Pregnancy and lactation are not exclusion criteria, as no experimental medicine is used in the PROLED-study.

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Central Region in Copenhagen. All participants signed informed consent prior to the study.

Participants in the present study

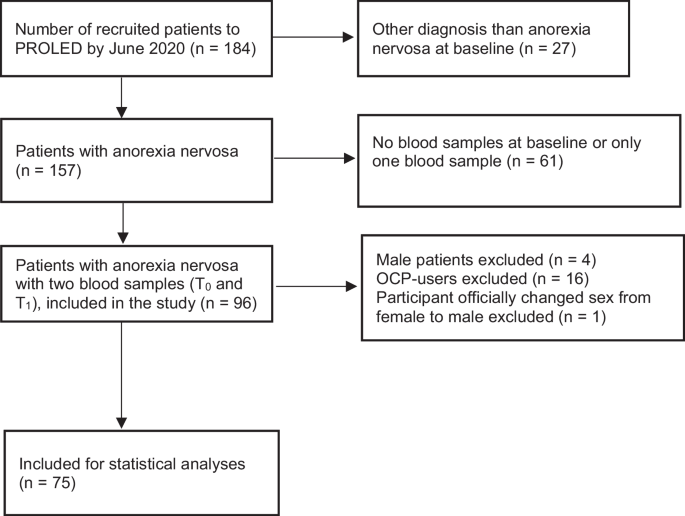

The current study is a substudy of the PROLED-study, and therefore all participants fulfilled the inclusion criteria and did not meet the exclusion criteria for participation in the PROLED-study. Furthermore, for the present study we only included female patients with plasma blood samples at two time points i.e., at baseline (T 0 ) and after weight restoration treatment (T 1 ). Seventy-five female individuals with AN (median age 24 years, baseline BMI 15.3 kg/m 2 ) and 26 healthy female control participants (HC) (median age 28 years, BMI 22.4 kg/m 2 ) were included in the present study. We also excluded participants using oral contraceptive pills as their plasma lipid concentrations could be affected [ 31 ]. Inclusion flowchart is presented in Fig. 1 . The patients met the diagnostic criteria in DSM-5 for AN [ 2 ] and were further divided into the restricting AN and binge-eating/purging AN subtypes. Diagnosis and clinical evaluation of all referred and included patients at baseline were performed by an experienced clinician with the semi-structured interview Eating Disorder Examination (EDE). Furthermore, psychometric self-report questionnaires were completed by the included patients.

Flowchart over inclusion for the present study. PROLED, PROspective Longitudinal all-comers inclusion study in eating disorders; n, number of participants; OCP, oral contraceptive pills

The HC were included in the study to assess whether the measured biomarkers and clinical findings differed from the included patients with AN at baseline. The HC were examined identically to the patients at baseline by an experienced clinician. Assessments included screening with Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders (SCID), questions about mental illnesses in the past 5 years, and the psychometric questionnaires.

The psychometric self-report questionnaires were completed at the time of blood samples at T 0 and again at T 1 . Questionnaires were e-mailed via Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap; [ 32 ]) hosted at www.redcap.regionh.dk .

For the majority of patients, blood was drawn at the day of discharge or a few days before. In the case of premature discharge, the last weekly blood sample was used for the follow-up/T 1 timepoint analyses and questionnaires were sent electronically through the secure platform digital postbox e-Boks used by public authorities.

Anthropometric examination and blood sampling

All participants with AN and HC were examined at baseline upon entering the PROLED-study, the AN group after basic stabilizing treatment including prevention of the refeeding syndrome. Every patient was individually monitored for the refeeding syndrome at the beginning of treatment and until they were somatically stable with acceptable blood electrolyte concentrations and without objective signs of the refeeding syndrome (usually within a week). The initial renourishment schedule was based on the patient’s caloric intake prior to treatment i.e., starting low, if the patient had a very low calorie intake. Once the patient was medically stable, they proceeded to a weight restoration renourishment schedule adjusted to meet the weight restoration requirement of 1 kg/week with the target BMI 20 kg/m 2 . The patients were prescribed five supervised daily meals (three main meals and two snack meals). In the case of somatic complications, the patient was transferred to the Department of Endocrinology at Herlev Hospital, Denmark, and returned to the Department of Eating Disorders, once they were somatically stable.

Anthropometric examination and blood sampling were repeated when the participants with AN were discharged. For all participants, weight and height were determined by a nurse, research assistant or medical doctor on a calibrated scale without clothes and shoes. BMI was calculated (weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared: kg/m 2 ).

Blood samples for total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), triglycerides (TG), free fatty acids (FFA), sex-hormone binding globulin (SHBG), testosterone, estradiol, progesterone, luteinizing hormone (LH), and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) were sampled between 8 a.m. and 12 p.m. Lipid concentrations were measured by enzymatic determination and absorption photometry on Cobas 8000, c702 modul (Roche Diagnostics, 2014, CV max 5%). Sex hormones were measured by electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (ECLIA) on Cobas 8000, e801 module (Roche Diagnostics, 2017, CV max 7%). VLDL was calculated as TG/2.2 (unit: mmol/L). The patients followed their prescribed meal schedules eating 5 times per day. Since this was a naturalistic study and it was regarded as disruptive to treatment goals and potentially triggering of ED behaviors thereby jeopardizing treatment adherence, patients were not fasting at the time of blood draws. However, although fasting lipid concentrations are commonly preferred, non-fasting concentrations have been used in research and shown to be useful in clinical decision making [ 33 , 34 ]. Moreover, studies have shown that the measured lipids are only minimally affected by the fat composition in the diet [ 35 , 36 ], and the non-fasting state was therefore accepted for the present study, as the purpose is to show the lipid profile in a naturalistic population. The HC participants were not fasting either and ate as usual. Samples were stored at − 80 °C until analysis at Denmark’s National Biobank at Statens Serum Institut, and afterwards analyzed at the National University Hospital, Rigshospitalet.

Questionnaires

Eating Disorder Examination (EDE-Q) : The EDE-Q is a 28-item self-reported questionnaire derived from the Eating Disorder Examination (EDE) interview [ 37 ]. The EDE-Q has four subscales and a global score designed to assess eating disorder psychopathology. It concerns behaviors over a 28-day time period on the Restraint, Eating Concern, Shape Concern, and Weight Concern subscales. The global score is the sum of the four subscale scores divided by four (the number of subscales). Higher scores indicate greater levels of symptomatology.

Eating Disorder Inventory (EDI-2) : The EDI-2 is a self-report questionnaire for assessing the presence of behaviors and cognitions associated with eating disorders including AN (both restricting and binge-eating/purging subtypes), bulimia nervosa, eating disorder not otherwise specified including binge-eating disorder [ 38 ]. EDI-2 items are summed into 12 subscales: Drive for Thinness, Bulimia, Body Dissatisfaction, Low Self-Esteem, Personal Alienation, Interpersonal Insecurity, Interpersonal Alienation, Interoceptive Deficits, Emotional Dysregulation, Perfectionism, Ascetism, and Maturity Fears. The total score is the sum of the subscales.

Major Depression Inventory (MDI) : The MDI is a 10-item self-reported questionnaire used as a screening instrument for major depression and for measuring the severity of clinical depression [ 39 ]. Symptoms are assessed for the past 2 weeks, and a higher score signifies more severe depression. The score range is 0–50 with 0–20 indicating no or doubtful depression, 21–25 mild depression, 26–30 moderate depression, and 31–50 severe depression.

Furthermore, an in-house self-reported questionnaire was used to extract basic personal information, problems in relation to eating, socioeconomic status, and eating disorder history. Educational attainment was divided into four categories: short education (primary school and trained workers), secondary school (gymnasium), medium long (university college), long (university degree and doctorate).

Statistical analyses were performed on the open-source software R (version 3.6.3, Holding the Windsock, released on 2020-02-29, The R Foundation for Statistical Computing Platform: x86_64-w64-mingw32/×64) and STATA 17 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Distribution was investigated, and due to skewness, non-parametric tests were used [ 40 ]. The differences between the AN and HC groups were assessed by the nonparametric test on the equality of medians, and the difference in the AN group before and after weight restoration treatment was assessed by Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05. Due to the explorative nature of the study and suboptimal power of non-parametric statistical tests, the results were not adjusted for multiple tests. Furthermore, an adjustment for multiple tests would primarily affect the results in Table 5 i.e., the median regression analyses.

To analyze potential predictors of plasma lipid concentration, median regression analyses were carried out with pre-treatment plasma lipid concentrations (total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, VLDL, TG, and FFA) as the dependent variables, and age, BMI, MDI score, AN subtype (restrictive/binge-purge), illness duration, educational attainment, and illness severity as independent variables. Lower educational level has been linked to unfavorable lipid concentrations, and therefore, educational attainment was included as a potential predictor [ 41 ].

Characteristics of the AN sample are presented in Table 1 . Almost two thirds of the sample had AN of the restricting type while the binge-eating/purging type comprised 37%. The most common comorbidities were depression and anxiety, diagnosed in about 40% of the sample (diagnostic information on comorbidities was extracted from the medical records). The median illness duration was 7 years (IQR 4.0–12.0), and of the 75 patients with AN, 90% were recruited from an inpatient ward. Median BMI increased from 15.3 (3.4) to 18.9 (2.9) kg/m 2 during a median weight restoration treatment period of 63 days (IQR 35.0–90.5) .

When we excluded the 23 patients (30.7%) who were taking antipsychotic medication (n = 52), results were similar to the full sample (n = 75) with significantly elevated plasma total cholesterol ( p = 0.007) and plasma TG ( p = 0.009) in patients with AN compared with HC. Additionally, plasma HDL concentration was significantly elevated in patients not taking antipsychotics, and FFA was significantly lower. Similar to the full sample, there were no changes in plasma lipid concentrations after weight restoration treatment. Therefore, we chose to use the full sample for further analyses. Additionally, when we excluded day hospital patients, results were also similar to the full sample, and therefore the full sample was used.

Comparison of the AN and HC groups

Baseline characteristics for the AN and HC samples are presented in Table 2 . Baseline BMI and weight were significantly lower for individuals with AN compared with HC. A significantly higher number of HC had a partner and the distribution of education differed significantly between the two groups with longer education in the HC group. Pre-treatment BMI, plasma lipid and sex hormone concentrations for the AN group are compared with the HC group in Table 3 . Pre-treatment concentrations of plasma total cholesterol and TG were significantly higher in the AN group compared with the HC group, while estradiol, testosterone, and LH were significantly lower. Similar differences between the AN and HC groups were observed between the AN post-treatment levels and the HC group ( p value for AN post-treatment compared with HC not shown). Table 4 shows substantial and highly significant differences between the pre-treatment scores of the AN group and the scores of the HC group on all EDE-Q and the EDI scales as well as the MDI depression scale.

Change with weight restoration

Table 3 shows a significant increase in BMI after weight restoration treatment (median 18.9 kg/m 2 ), but no significant changes in plasma concentrations of the lipids (total cholesterol and TG). In fact, the only significant change was observed in the sex hormone category, where SHBG showed a significant decrease and FSH and LH a significant increase. However, Table 4 shows no significant changes in EDI and EDE-Q subscales or global scores after weight restoration treatment; yet there was a relatively small, but significant decrease in MDI depression scores.

Predictors of plasma lipid concentrations

In the AN group, pre-treatment total cholesterol (r = 0.29, p = 0.01), TG (r = 0.40, p = 0.0004), and VLDL (r = 0.34, p = 0.003) were significantly positively correlated with illness duration. However, in median regression models no significant predictors of HDL, VLDL, and FFA were identified (see Table 5 ). Illness duration was positively associated with only TG. Age was positively associated with both total cholesterol and LDL, whereas long education was positively associated with TG and negatively associated with LDL. Yet, Table 5 shows that most of these associations were only significant at the 0.05 level and would not be significant if multiple testing was considered.

The findings of the present study are based on data from a large, prospective cohort study including a case–control study at baseline comparing patients with AN with HC. Previous longitudinal studies investigating lipids in AN are few and inconsistent, and with the present study we confirmed that (1) plasma concentrations of lipids are significantly higher in individuals with AN compared with HC, and that (2) plasma lipid concentrations are persistently elevated with weight restoration. The median regression analyses suggested that age, illness duration, and long educational level are associated with plasma lipid concentrations.

Lipids: comparison of the AN and HC groups

The observed significantly elevated total cholesterol concentrations are in accordance with a systematic review and meta-analysis [ 6 ]. Similarly, we also found significantly elevated TG in accordance with other studies [ 6 , 9 , 17 ].

Lipids: change after weight restoration treatment

The concentration of total cholesterol and TG was higher in individuals with AN compared with HC, and these lipids remained elevated after partial weight restoration treatment despite significantly increased BMI in the same time period. Similarly, FFA, estradiol, testosterone, and progesterone were significantly lower compared with HC and remained so after partial weight restoration. While lipid concentrations were stable, a significant decrease in depressive symptoms after partial weight restoration was observed, but there was no significant change in self-reported eating disorder symptoms.

The studies included in the meta-analysis on lipid concentrations in patients with AN compared with HC, were heterogenous and included few longitudinal studies [ 6 ]. Consequently, the replication in the present study of significantly increased total cholesterol and TG, and of no significant change after weight restoration treatment, corroborate previous findings in a larger, homogenous sample with normalized weight at follow-up.

The findings in the present study, with no significant changes after weight restoration treatment, could be due to an underlying pathophysiology with increased lipids not merely being a consequence rapid weight loss caused by starvation, but potentially part of an underlying, premorbid illness specific mechanism i.e., a trait/biomarker of AN. However, further investigation, with longer-follow-up is required to firmly conclude whether lipid alterations are a state or trait effect of AN.

The non-significant change in eating disorder symptoms, as assessed by EDI-2 and EDE-Q, were not consistent with the literature [ 42 ], and underscores that weight restoration treatment is only one component of recovery from eating disorder symptoms [ 43 ]. A possible explanation for the observed persistently high levels of eating disorder symptoms in the present study could be explained by the long median illness duration of 7 years. Weight restoration treatment was associated with changes in depressive symptoms (MDI score decreased from 33 to 30.5); however, core eating disorder symptoms usually take longer to change and require other forms of interventions. The majority of participants were admitted to inpatient departments (95%) reflecting their illness severity i.e., the eating disorder behavior could not be managed by outpatient treatment alone. It is possible that there is a sub-group in the AN population (e.g., with severe comorbidities or high levels of emotional dysregulation) with more crystallized eating disorder core pathology, which may require more intensive interventions beyond standard inpatient eating disorder treatment.

Predictors of lipid concentrations

Despite a significant bivariate correlation between total cholesterol and AN illness duration, median regression analyses showed only age as a predictor of total cholesterol. However, the regression analyses suggested a number of associations with LDL and TG: age and long education predicted LDL, and illness duration and long education predicted TG. Similarly, the meta-analysis showed a positive association with TG for mean illness duration [ 6 ]. A study found an association between treatment non-response and illness duration, and expectedly the likelihood of poor therapy response was increased for individuals with AN with higher eating disorder symptomatology [ 44 ]. Longer illness duration could be related to illness progression which, perhaps, could be linked to high cholesterol. In the present study 47 individuals had restrictive type AN (62.7%) and 28 individuals had binge-eating/purging type AN (37.3%). Based on the worse outcome in the binge-eating/purging subtype [ 45 ], a larger sample size of both AN subtypes would enable an in-depth investigation. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis [ 45 ] collected evidence on the transition from restrictive AN to binge-eating/purging AN, and reported several worse outcomes including longer duration of illness, higher prevalence of past traumatic experience, comorbid mental disorders, somatoform dissociation and, suicidality related to the binge-eating/purging AN subtype [ 46 , 47 , 48 ]. As AN has one of the highest mortalities of all psychiatric disorders, partly due to suicide [ 49 , 50 ], it could also be relevant to further investigate if there are specific subgroups, e.g. the binge-eating/purging subtype, with higher prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicide in relation to altered lipid concentrations [ 19 ]. As high blood cholesterol concentrations could act by increasing serotonin activity, high concentrations could also be a protective factor against suicidality [ 19 , 20 ]. However, the present study only included 28 patients with the binge-eating/purging subtype of AN, and a larger sample would be required for further investigation.

- Sex hormones

At baseline, the significantly lower plasma estradiol, testosterone, and LH concentrations in AN compared with HC are consistent with the literature [ 22 ]. Diverging from the literature, we did not observe a significant difference in plasma progesterone and FSH concentrations between AN and HC [ 22 , 51 ].