Jump to navigation

- Undergraduate Admissions

- Transfer Admissions

- Graduate Admissions

- Honors and Scholars Admissions

- International Admissions

- Law Admissions

- Office of Financial Aid

- Orientation

- Pre-College Programs

- Scholarships

- Tuition & Fees

- Academic Calendar

- Academic Colleges

- Degree Programs

- Online Programs

- Class Schedule

- Workforce Development

- Sponsored Programs and Research Services

- Technology Transfer

- Faculty Expertise Database

- Research Centers

- College of Graduate Studies

- Institutional Research and Analysis

- At a Glance

- Concerned Vikes

- Free Speech on Campus

- Policies and Procedures

- Messages & Updates

- In the News

- Board of Trustees

- Senior Leadership Team

- Services Near CSU

Cleveland State University

Search this site

How professors grade a research paper.

This sheet is designed for grading research papers. Scores range from 1 (low) to 5 (high).

Higher Order Concerns

What’s working: tell the writer the best features of his or her text here

Focus 1 2 3 4 5

A focus is the thesis or main point of your writing. Is it clear? Is the whole paper on the focus? Write out the focus right here.

Development

Development refers to the support you give your focus.

Comprehensiveness 1 2 3 4 5

Are there enough quotes, paraphrases, examples, inferences, reasoning, opinions, forecasts? Has the writer given a reasonable number of sources to be comprehensive on this subject for this assignment?

Background Information 1 2 3 4 5

Has the writer from the beginning of the paper introduced the research cited appropriately (i.e. full name, year of book/article, general goals of research, context for research)? Do any definitions or histories need to be given before the body of the paper begins?

Integration of Sources 1 2 3 4 5

How well has the writer paraphrased and quoted so that the voice of the writer, not the sources, guides the text? Is the in-text citation done well?

Audience Adaptation 1 2 3 4 5

Is the text written for a college-level audience with appropriate vocabulary and length of explanations? Are appropriate materials explained well? Some potential problems occur when writers write seemingly for themselves without addressing an audience (and the text can be too personal or informal), or sometimes writers address only experts, making the text too dense and short.

Argument 1 2 3 4 5

If the writer presents an argument, is it a full one? Does it lack any information? Does the argument follow through to a conclusion? Does it include a rebuttal? Is the rebuttal a fair one? Has the writer respectfully treated the views of all sides?

Organization 1 2 3 4 5

Has the writer organized or structured the paper in the way that the discipline suggests? That is, if it is a lab report, does it adhere to the proper structure? If an argumentative essay, is it organized to present an argument? Can the reader follow individual paragraphs—are they well organized? Does the writer use meta-discourse (language about language) to direct the reader through the text?

Lower Order Concerns

Style 1 2 3 4 5.

Style can be considered in terms of sentence patterns and diction. Are the sentence patterns varied or all the same? Variety produces more interesting reading. Is the diction appropriate for a college-level assignment? Is the diction appropriate for the discipline? Has the writer included too many informal elements (e.g. cliché, contractions, the use of you or I, informal diction)?

Mechanics 1 2 3 4 5

Mechanics refer to punctuation, spelling and grammar. Could the writer benefit from a brush up on some grammatical points? Could the writer learn new punctuation strategies?

Return to WAC index

©2024 Cleveland State University | 2121 Euclid Avenue, Cleveland, OH 44115-2214 | (216) 687-2000. Cleveland State University is an equal opportunity educator and employer. Affirmative Action | Diversity | Employment | Tobacco Free | Non-Discrimination Statement | Web Privacy Statement | Accreditations

How To Write A Research Paper

Step-By-Step Tutorial With Examples + FREE Template

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewer: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | March 2024

For many students, crafting a strong research paper from scratch can feel like a daunting task – and rightly so! In this post, we’ll unpack what a research paper is, what it needs to do , and how to write one – in three easy steps. 🙂

Overview: Writing A Research Paper

What (exactly) is a research paper.

- How to write a research paper

- Stage 1 : Topic & literature search

- Stage 2 : Structure & outline

- Stage 3 : Iterative writing

- Key takeaways

Let’s start by asking the most important question, “ What is a research paper? ”.

Simply put, a research paper is a scholarly written work where the writer (that’s you!) answers a specific question (this is called a research question ) through evidence-based arguments . Evidence-based is the keyword here. In other words, a research paper is different from an essay or other writing assignments that draw from the writer’s personal opinions or experiences. With a research paper, it’s all about building your arguments based on evidence (we’ll talk more about that evidence a little later).

Now, it’s worth noting that there are many different types of research papers , including analytical papers (the type I just described), argumentative papers, and interpretative papers. Here, we’ll focus on analytical papers , as these are some of the most common – but if you’re keen to learn about other types of research papers, be sure to check out the rest of the blog .

With that basic foundation laid, let’s get down to business and look at how to write a research paper .

Overview: The 3-Stage Process

While there are, of course, many potential approaches you can take to write a research paper, there are typically three stages to the writing process. So, in this tutorial, we’ll present a straightforward three-step process that we use when working with students at Grad Coach.

These three steps are:

- Finding a research topic and reviewing the existing literature

- Developing a provisional structure and outline for your paper, and

- Writing up your initial draft and then refining it iteratively

Let’s dig into each of these.

Need a helping hand?

Step 1: Find a topic and review the literature

As we mentioned earlier, in a research paper, you, as the researcher, will try to answer a question . More specifically, that’s called a research question , and it sets the direction of your entire paper. What’s important to understand though is that you’ll need to answer that research question with the help of high-quality sources – for example, journal articles, government reports, case studies, and so on. We’ll circle back to this in a minute.

The first stage of the research process is deciding on what your research question will be and then reviewing the existing literature (in other words, past studies and papers) to see what they say about that specific research question. In some cases, your professor may provide you with a predetermined research question (or set of questions). However, in many cases, you’ll need to find your own research question within a certain topic area.

Finding a strong research question hinges on identifying a meaningful research gap – in other words, an area that’s lacking in existing research. There’s a lot to unpack here, so if you wanna learn more, check out the plain-language explainer video below.

Once you’ve figured out which question (or questions) you’ll attempt to answer in your research paper, you’ll need to do a deep dive into the existing literature – this is called a “ literature search ”. Again, there are many ways to go about this, but your most likely starting point will be Google Scholar .

If you’re new to Google Scholar, think of it as Google for the academic world. You can start by simply entering a few different keywords that are relevant to your research question and it will then present a host of articles for you to review. What you want to pay close attention to here is the number of citations for each paper – the more citations a paper has, the more credible it is (generally speaking – there are some exceptions, of course).

Ideally, what you’re looking for are well-cited papers that are highly relevant to your topic. That said, keep in mind that citations are a cumulative metric , so older papers will often have more citations than newer papers – just because they’ve been around for longer. So, don’t fixate on this metric in isolation – relevance and recency are also very important.

Beyond Google Scholar, you’ll also definitely want to check out academic databases and aggregators such as Science Direct, PubMed, JStor and so on. These will often overlap with the results that you find in Google Scholar, but they can also reveal some hidden gems – so, be sure to check them out.

Once you’ve worked your way through all the literature, you’ll want to catalogue all this information in some sort of spreadsheet so that you can easily recall who said what, when and within what context. If you’d like, we’ve got a free literature spreadsheet that helps you do exactly that.

Step 2: Develop a structure and outline

With your research question pinned down and your literature digested and catalogued, it’s time to move on to planning your actual research paper .

It might sound obvious, but it’s really important to have some sort of rough outline in place before you start writing your paper. So often, we see students eagerly rushing into the writing phase, only to land up with a disjointed research paper that rambles on in multiple

Now, the secret here is to not get caught up in the fine details . Realistically, all you need at this stage is a bullet-point list that describes (in broad strokes) what you’ll discuss and in what order. It’s also useful to remember that you’re not glued to this outline – in all likelihood, you’ll chop and change some sections once you start writing, and that’s perfectly okay. What’s important is that you have some sort of roadmap in place from the start.

At this stage you might be wondering, “ But how should I structure my research paper? ”. Well, there’s no one-size-fits-all solution here, but in general, a research paper will consist of a few relatively standardised components:

- Introduction

- Literature review

- Methodology

Let’s take a look at each of these.

First up is the introduction section . As the name suggests, the purpose of the introduction is to set the scene for your research paper. There are usually (at least) four ingredients that go into this section – these are the background to the topic, the research problem and resultant research question , and the justification or rationale. If you’re interested, the video below unpacks the introduction section in more detail.

The next section of your research paper will typically be your literature review . Remember all that literature you worked through earlier? Well, this is where you’ll present your interpretation of all that content . You’ll do this by writing about recent trends, developments, and arguments within the literature – but more specifically, those that are relevant to your research question . The literature review can oftentimes seem a little daunting, even to seasoned researchers, so be sure to check out our extensive collection of literature review content here .

With the introduction and lit review out of the way, the next section of your paper is the research methodology . In a nutshell, the methodology section should describe to your reader what you did (beyond just reviewing the existing literature) to answer your research question. For example, what data did you collect, how did you collect that data, how did you analyse that data and so on? For each choice, you’ll also need to justify why you chose to do it that way, and what the strengths and weaknesses of your approach were.

Now, it’s worth mentioning that for some research papers, this aspect of the project may be a lot simpler . For example, you may only need to draw on secondary sources (in other words, existing data sets). In some cases, you may just be asked to draw your conclusions from the literature search itself (in other words, there may be no data analysis at all). But, if you are required to collect and analyse data, you’ll need to pay a lot of attention to the methodology section. The video below provides an example of what the methodology section might look like.

By this stage of your paper, you will have explained what your research question is, what the existing literature has to say about that question, and how you analysed additional data to try to answer your question. So, the natural next step is to present your analysis of that data . This section is usually called the “results” or “analysis” section and this is where you’ll showcase your findings.

Depending on your school’s requirements, you may need to present and interpret the data in one section – or you might split the presentation and the interpretation into two sections. In the latter case, your “results” section will just describe the data, and the “discussion” is where you’ll interpret that data and explicitly link your analysis back to your research question. If you’re not sure which approach to take, check in with your professor or take a look at past papers to see what the norms are for your programme.

Alright – once you’ve presented and discussed your results, it’s time to wrap it up . This usually takes the form of the “ conclusion ” section. In the conclusion, you’ll need to highlight the key takeaways from your study and close the loop by explicitly answering your research question. Again, the exact requirements here will vary depending on your programme (and you may not even need a conclusion section at all) – so be sure to check with your professor if you’re unsure.

Step 3: Write and refine

Finally, it’s time to get writing. All too often though, students hit a brick wall right about here… So, how do you avoid this happening to you?

Well, there’s a lot to be said when it comes to writing a research paper (or any sort of academic piece), but we’ll share three practical tips to help you get started.

First and foremost , it’s essential to approach your writing as an iterative process. In other words, you need to start with a really messy first draft and then polish it over multiple rounds of editing. Don’t waste your time trying to write a perfect research paper in one go. Instead, take the pressure off yourself by adopting an iterative approach.

Secondly , it’s important to always lean towards critical writing , rather than descriptive writing. What does this mean? Well, at the simplest level, descriptive writing focuses on the “ what ”, while critical writing digs into the “ so what ” – in other words, the implications. If you’re not familiar with these two types of writing, don’t worry! You can find a plain-language explanation here.

Last but not least, you’ll need to get your referencing right. Specifically, you’ll need to provide credible, correctly formatted citations for the statements you make. We see students making referencing mistakes all the time and it costs them dearly. The good news is that you can easily avoid this by using a simple reference manager . If you don’t have one, check out our video about Mendeley, an easy (and free) reference management tool that you can start using today.

Recap: Key Takeaways

We’ve covered a lot of ground here. To recap, the three steps to writing a high-quality research paper are:

- To choose a research question and review the literature

- To plan your paper structure and draft an outline

- To take an iterative approach to writing, focusing on critical writing and strong referencing

Remember, this is just a b ig-picture overview of the research paper development process and there’s a lot more nuance to unpack. So, be sure to grab a copy of our free research paper template to learn more about how to write a research paper.

You Might Also Like:

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

College Info Geek

How to Write a Killer Research Paper (Even If You Hate Writing)

C.I.G. is supported in part by its readers. If you buy through our links, we may earn an affiliate commission. Read more here.

Research papers.

Unless you’re a weirdo like me, you probably dread them. When I was in college, depending on the class, I even dreaded these.

It’s the sort of project that can leave even the most organized student quaking in their boots, staring at the assignment like they’re Luke Skywalker and it’s the Death Star.

You have to pick a broad topic, do some in-depth research, hone in on a research question, and then present your answer to that question in an interesting way. Oh, and you have to use citations, too.

How on earth are you supposed to tackle this thing?

Fear not, for even the Death Star had weaknesses. With a well-devised plan, some courage, and maybe a little help from a few midichlorians, you can conquer your research paper, too.

Let’s get started.

1. Pick a Topic

And pick one that interests you. This is not up for debate.

You and this topic are going to be spending a lot of time together, so you might as well pick something you like, or, at the very least, have a vague interest in. Even if you hate the class, there’s probably at least one topic that you’re curious about.

Maybe you want to write about “mental health in high schools” for your paper in your education class. That’s a good start, but take a couple steps to hone your idea a little further so you have an idea of what to research. Here’s a couple of factors to look at when you want to get more specific:

- Timeframe : What are the most important mental health issues for high schoolers that have come up in the last five years?

- Location : How does the mental health of students in your area compare to students in the next state (or country) over?

- Culture or Group : How does the mental health of inner-city students compare to those in the suburbs or places like Silicon Valley?

- Solution : If schools were to make one change to high schools to improve the well-being of their students, what would be most effective, and why?

It’s good to be clear about what you’re researching, but make sure you don’t box yourself into a corner. Try to avoid being too local (if the area is a small town, for example), or too recent, as there may not be enough research conducted to support an entire paper on the subject.

Also, avoid super analytical or technical topics that you think you’ll have a hard time writing about (unless that’s the assignment…then jump right into all the technicalities you want).

You’ll probably need to do some background research and possibly brainstorm with your professor before you can identify a topic that’s specialized enough for your paper.

At the very least, skim the Encyclopedia Britannica section on your general area of interest. Your professor is another resource: use them! They’re probably more than happy to point you in the direction of a possible research topic.

Of course, this is going to be highly dependent on your class and the criteria set forth by your professor, so make sure you read your assignment and understand what it’s asking for. If you feel the assignment is unclear, don’t go any further without talking to your professor about it.

2. Create a Clear Thesis Statement

Say it with me: a research paper without a thesis question or statement is just a fancy book report.

All research papers fall under three general categories: analytical, expository, or argumentative.

- Analytical papers present an analysis of information (effects of stress on the human brain)

- Expository papers seek to explain something (Julius Caesar’s rise to power)

- Argumentative papers are trying to prove a point (Dumbledore shouldn’t be running a school for children).

So figure out what sort of paper you’d like to write, and then come up with a viable thesis statement or question.

Maybe it starts out looking like this:

- Julius Caesar’s rise to power was affected by three major factors.

Ok, not bad. You could probably write a paper based on this. But it’s not great , either. It’s not specific, neither is it arguable . You’re not really entering any sort of discussion.

Maybe you rework it a little to be more specific and you get:

- Julius Caesar’s quick rise to power was a direct result of a power vacuum and social instability created by years of war and internal political corruption.

Better. Now you can actually think about researching it.

Every good thesis statement has three important qualities: it’s focused , it picks a side , and it can be backed up with research .

If you’re missing any of these qualities, you’re gonna have a bad time. Avoid vague modifier words like “positive” and “negative.” Instead use precise, strong language to formulate your argument.

Take this thesis statement for example:

- “ High schools should stop assigning so much homework, because it has a negative impact on students’ lives.”

Sure, it’s arguable…but only sort of . It’s pretty vague. We don’t really know what is meant by “negative”, other than “generically bad”. Before you get into the research, you have to define your argument a little more.

Revised Version:

- “ High schools in the United States should assign less homework, as lower workloads improve students’ sleep, stress levels, and, surprisingly, their grades.”

When in doubt, always look at your thesis and ask, “Is this arguable?” Is there something you need to prove ? If not, then your thesis probably isn’t strong enough. If yes, then as long as you can actually prove it with your research, you’re golden.

Good thesis statements give you a clear goal. You know exactly what you’re looking for, and you know exactly where you’re going with the paper. Try to be as specific and clear as possible. That makes the next step a lot easier:

3. Hit the Books

So you have your thesis, you know what you’re looking for. It’s time to actually go out and do some real research. By real research, I mean more than a quick internet search or a quick skim through some weak secondary or tertiary sources.

If you’ve chosen a thesis you’re a little unsteady on, a preliminary skim through Google is fine, but make sure you go the extra mile. Some professors will even have a list of required resources (e.g. “Three academic articles, two books, one interview…etc).

It’s a good idea to start by heading to the library and asking your local librarian for help (they’re usually so excited to help you find things!).

Check your school library for research papers and books on the topic. Look for primary sources, such as journals, personal records, or contemporary newspaper articles when you can find them.

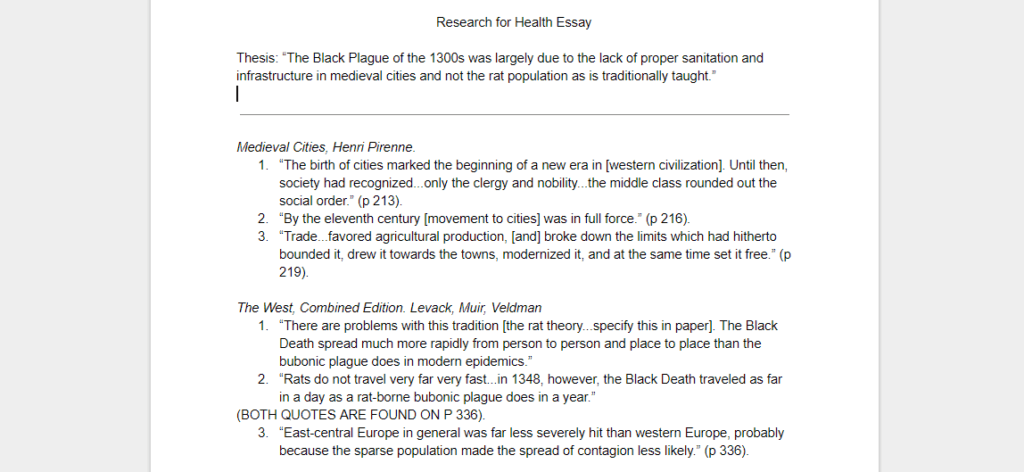

As you’re starting your research, create some kind of system for filing helpful quotes, links, and other sources. I preferred it to all be on one text document on my computer, but you could try a physical file, too.

In this text document, I start compiling a list of all the sources I’m using. It tends to look like this:

Remember that at this point, your thesis isn’t solid. It’s still in a semi-squishy state. If your research starts to strongly contradict your thesis, then come up with a new thesis, revise, and keep on compiling quotes.

The more support you can find, the better. Depending on how long your paper is, you should have 3-10 different sources, with all sorts of quotes between them.

Here are some good places to look for reputable sources:

- Google Scholar

- Sites ending in .edu, .org, or .gov. While it’s not a rule, these sites tend to represent organizations, and they are more likely to be reputable than your run-of-the-mill .com sites

- Your school library. It should have a section for articles and newspapers as well as books

- Your school’s free academic database

- Online encyclopedias like Britannica

- Online almanacs and other databases

As you read, analyze your sources closely, and take good notes . Jot down general observations, questions, and answers to those questions when you find them. Once you have a sizable stack of research notes, it’s time to start organizing your paper.

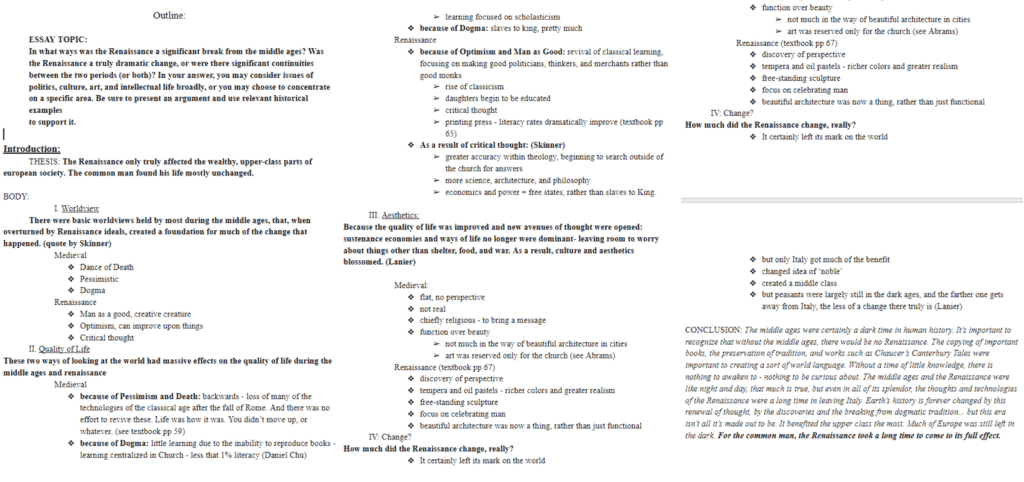

4. Write an Outline

Even if you normally feel confident writing a paper without one, use an outline when you’re working on a research paper.

Outlines basically do all the heavy lifting for you when it comes to writing. They keep you organized and on track. Even if you feel tempted to just jump in and brain-dump, resist. You’ll thank me later.

Here’s how to structure an outline:

You’ll notice it’s fairly concise, and it has three major parts: the introduction , the body , and the conclusion . Also notice that I haven’t bothered to organize my research too much.

I’ve just dumped all the relevant citations under the headings I think they’ll end up under, so I can put in my quotes from my research document later as they fit into the overall text.

Let’s get a little more in-depth with this:

The Introduction

The introduction is made up of two main parts: the thesis and the introduction to the supporting points. This is where you essentially tell your reader exactly what sort of wild ride they’re in for if they read on.

It’s all about preparing your reader’s mind to start thinking about your argument or question before you even really get started.

Present your thesis and your supporting points clearly and concisely. It should be no longer than a paragraph or two. Keep it simple and easy to read.

Body Paragraphs

Okay, now that you’ve made your point, it’s time to prove it. This is where your body paragraphs come in. The length of this is entirely dependent on the criteria set by your professor, so keep that in mind.

However, as a rule, you should have at least three supporting points to help defend, prove, or explain your thesis. Put your weakest point first, and your strongest point last.

This doesn’t need a lot of outlining. Basically, take your introduction outline and copy it over. Your conclusion should be about a paragraph long, and it should summarize your main points and restate your thesis.

There’s also another key component to this outline example that I haven’t touched on yet:

Research and Annotations

Some people like to write first, and annotate later. Personally, I like to get my quotes and annotations in right at the start of the writing process.

I find the rest of the paper goes more smoothly, and it’s easier to ensure that I’ve compiled enough support for my claim. That way, I don’t go through all the work of writing the paper, only to discover that my thesis doesn’t actually hold any water!

As a general rule, it’s good to have at least 3-5 sources for every supporting point. Whenever you make a claim in your paper, you should support it with evidence.

Some professors are laxer on this, and some are more stringent. Make sure you understand your assignment requirements really, really, really well. You don’t want to get marked down for missing the correct number of sources!

At this stage, you should also be sure of what sort of format your professor is looking for (APA, MLA, etc.) , as this will save you a lot of headache later.

When I was in college, some professors wanted in-text parenthetical citations whenever I made a claim or used my research at all. Others only wanted citations at the end of a paragraph. And others didn’t mind in-text citations at all, so long as you had a bibliography at the end of your entire paper.

So, go through your outline and start inserting your quotes and citations now. Count them up. If you need more, then add them. If you think you have enough (read: your claims are so supported that even Voldemort himself couldn’t scare them), then move on to the next step:

5. Write the First Draft

Time to type this thing up. If you created a strong enough outline, this should be a breeze. Most of it should already be written for you. All you have to do at this point is fill it in. You’ve successfully avoided the initial blank-screen panic .

Don’t worry too much about grammar or prose quality at this point. It’s the rough draft, and it’s not supposed to see the light of day.

I find it helpful to highlight direct quotes, summaries, paraphrases, and claims as I put them in. This helps me ensure that I never forget to cite any of them.

So, do what you’ve gotta do . Go to a studious place or create one , put on an awesome playlist, close your social media apps, and get the work done.

Once you’ve gotten the gist of your paper down, the real work begins:

6. Revise Your Draft

Okay, now that you’ve word-vomited everywhere in a semi-organized fashion, it’s time to start building this thing into a cohesive paper. If you took the time to outline properly, then this part shouldn’t be too difficult.

Every paper has two editing stages:the developmental edit , and the line edit.

The developmental edit (the first one, at least) is for your eyes only. This is the part where you take a long, hard look at your paper and ask yourself, “Does this make sense, and does it accomplish what I want it to accomplish?” If it does, then great. If it doesn’t, then how can you rearrange or change it so that it does?

Here are a few good questions to ask yourself at this stage:

- Is the paper well-organized, and does it have a logical flow of thought from paragraph to paragraph?

- Does your thesis hold up to the three criteria listed earlier? Is it well supported by your research and arguments?

- Have you checked that all your sources are properly cited?

- How repetitive is the paper? Can you get rid of superlative points or language to tighten up your argument?

Once you’ve run the paper through this process at least once, it’s time for the line edit . This is the part where you check for punctuation, spelling, and grammar errors.

It helps to let your paper sit overnight, and then read it out loud to yourself, or the cat, or have a friend read it. Often, our brains know what we “meant” to say, and it’s difficult for us to catch small grammatical or spelling errors.

Here are a couple more final questions to ask yourself before you call it a day:

- Have you avoided filler words , adverbs , and passive voice as much as possible?

- Have you checked for proper grammar, spelling, and punctuation? Spell-checker software is pretty adept these days, but it still isn’t perfect.

If you need help editing your paper, and your regular software just isn’t cutting it, Grammarly is a good app for Windows, Mac, iOS, and Chrome that goes above and beyond your run-of-the-mill spell-checker. It looks for things like sentence structure and length, as well as accidental plagiarism and passive tense.

7. Organize Your Sources

The paper’s written, but it’s not over. You’ve still got to create the very last page: the “works cited” or bibliography page.

Now, this page works a little differently depending on what style your professor has asked you to use, and it can get pretty confusing, as different types of sources are formatted completely differently.

The most important thing to ensure here is that every single source, whether big or small, is on this page before you turn your paper in. If you forget to cite something, or don’t cite it properly, you run the risk of plagiarism.

I got through college by using a couple of different tools to format it for me. Here are some absolute life-savers:

- EasyBib – I literally used this tool all throughout college to format my citations for me, it does all the heavy lifting for you, and it’s free .

- Microsoft Word – I honestly never touched Microsoft Word throughout my college years, but it actually has a tool that will create citations and bibliographies for you, so it’s worth using if you have it on your computer.

Onwards: One Step at a Time

I leave you with this parting advice:

Once you understand the method, research papers really aren’t as difficult as they seem. Sure, there’s a lot to do, but don’t be daunted. Just take it step by step, piece by piece, and give yourself plenty of time. Take frequent breaks, stay organized, and never, ever, ever forget to cite your sources. You can do this!

Looking for tools to make the writing process easier? Check out our list of the best writing apps .

Image Credits: featured

How to Do Research With a Professor

By jason eisner (2012).

This is a bit of advice for lucky students who get to do research with a professor.

Take this opportunity seriously. Either you make it your top priority, or you don't do it at all. That's the message. Read the rest of the page if you want to know why and how.

Why This Webpage?

I'd find it awkward to say these things directly to a nice undergrad or master's student I was starting to work with. It would feel like talking down to them, whereas I like my research collaborators—however junior—to talk with me comfortably as equals, have fun, and come up with half the ideas.

Still, it's important to understand up front what the pressures are on faculty-student collaborations. So here are some things to bear in mind.

How the Professor Sees It

[If the professor is female/male, click here .]

Your research advisor doesn't get much credit for working with junior students, and would find it easier and safer to work with senior students. It's just that someone gave him/her a chance once: that's how he/she ended up where he/she is today. He/She'd like to pay that debt forward.

But should it be paid forward to you ? Choosing you represents a substantial commitment on your advisor's part, and a vote of confidence in you.

Time Investment

The hours that your advisor spends with you, one-on-one, are hours that he/she no longer has available for

So he/she does expect that you'll pay him/her back, by working as hard as he/she did when he/she got his/her chance.

Research Agenda Investment

Your advisor is not only devoting time to you, but taking a risk. You are being entrusted with part of his/her research agenda. The goal is to make new discoveries and publish them on schedule. If you drop the ball, then your advisor and others in the lab will miss important publication deadlines, or will get scooped by researchers elsewhere, or will be unable to take the next step that was depending on you.

So, don't start doing research with the idea that it's something "extra" that may or may not work out. This is not an advanced course that you can just drop or do poorly in. Unless your advisor agrees otherwise, you are a critical player in the mission—you have a responsibility not to let others down. Remember, someone is taking a chance on you.

Opportunity Cost

I heard once that your boyfriend or girlfriend will ask increasingly tough questions as your relationship ages:

Your advisor may also ask these questions. At first, he/she'll be happy that he/she attracted a smart student to work on a problem that needed working on. But he/she may sour if he/she comes to feel that he/she's wasting his/her time on you, or would have been wiser to assign the project to someone else.

What Do You Get Out Of It?

You too are giving up time from your other activities (including classwork!) to do this. So what do you get out of it?

Most important, you get research experience. This is exceptionally important if you are considering doing a Ph.D.

The Ph.D. puts you on a track to focus on research for the next 5+ years and possibly for your whole life. Are you sure you want to get married to research? Maybe, but try dating research first before you commit.

Ph.D. programs are looking for students who are already proven researchers. Grades are not so strongly correlated with research success. The most crucial part of your application is letters from one or more credible faculty who can attest—with lots of supporting detail—that you have the creativity, intelligence, enthusiasm, productivity, technical background, and interpersonal and intrapersonal skills to do a great Ph.D. with your future advisor.

A good friend of mine in college was taken under the wing of a senior professor in a different department. She was a demanding taskmaster, and my friend ended up spending much more time working in her lab than he expected. But it changed his life. She insisted that he apply to grad school in her field, and she got him accepted to a top Ph.D. program. He became a professor and is now the chairman of a department at a highly respected school, where he enjoys doing research with his own undergraduates.

Even if you are not considering a Ph.D., you will learn a great deal from working closely with a professor. Often you may be working with the world's leading expert on a particular topic— that's the main criterion for tenure here. (So our tenured faculty have passed this bar at some point, and most of our untenured faculty are successfully building a case that they will do so.)

Students don't always realize how respected and innovative our faculty are within their own subfields, but that's why you chose to attend a highly-ranked research university. Your advisor may or may not be a great classroom teacher, but he/she has shown himself/herself to be extremely good at working with graduate students to produce papers that advance the field. What you'll learn from doing that is quite different from what you'll learn in the classroom.

What You Can Do to Succeed

Here's some basic advice targeted at new research students. There are also many webpages about how to be a "good grad student," which should also be useful to undergrads doing research.

Time Commitment

Make plenty of room. In order to make research your first priority, you may need to reduce your courseload or extracurriculars. This is worth discussing with both your academic advisor and your research advisor.

Find out what the deadlines are. For example, there may be a target for submitting a paper to a particular conference. When planning for deadlines, bear in mind that everything will take twice as long as you expect—or four times as long if you've never done it before. Often a paper takes roughly a year of work for a grad student (if it includes experiments), although they may be working on other things during that year as well.

Be honest. If you suspect that you may not have time to do justice to the project after all, don't string your advisor along. Take a deep breath, apologize, and explain the situation. Then your advisor can make an informed decision about whether to suspend the project, give it to someone else, get a grad student involved, etc. This is better than a slow burn of agitation on both sides.

Time Management

Make weekly progress. Set goalposts, and be sure you make real progress from week to week. Use your meeting time or email each week to make sure that you agree on what the goal for next week is.

" Write the paper first. " The evolving paper is a way of organizing and sharing your thoughts and hammering out details. New ideas (including future plans) can go into that document, or appendices to it.

Experimental logbook. This is a file recording the questions you asked, the experiments you ran to answer them (including the command-line details needed to reproduce them perfectly), the results, and your analysis of the results.

Notes on your reading, including reading you plan to do. This should be organized by paper and/or by topic, aimed at helping you quickly recover the important points.

Working With Others

Again, be honest. Be very clear at all times about what you do and don't understand. Don't fake it. It's okay to say you're confused or don't know something; you need to ask questions to get unconfused. Also be clear about what you have and haven't done.

Pick a topic of mutual interest that you can handle. This is a matter for careful discussion at the start of the relationship.

Be explicit about what you need from your advisor. You can take some initiative in shaping the kind of advising relationship that will work best for you. Every advisor has a typical advising style, which is some compromise between his/her advising philosophy, his/her personality, your personality, and the realities of limited time. But if you need a different kind of guidance or a different way of organizing your relationship, ask for it. Most advisors will appreciate the initiative and can adapt to some extent.

Know how to ask for help. If you feel you would benefit from closer guidance, say: "Please tell me exactly what you want me to do by next Wednesday and I will have it done." If you get stuck technically, ask your advisor to help you get unstuck! He/She can write out a more detailed plan for you, give you things to read, ask a senior grad student to work with you, point you to software libraries, etc. Asking the right person can be 100 times faster than doing it yourself.

Your value to the project lies in how much you get done—it doesn't matter whether you invented it all yourself. This is not homework and getting help is not cheating. Anything that is already known in the field is fair game to reuse (with citations). And people can also help you invent the new stuff, as long as you acknowledge their help appropriately (possibly with co-authorship). Getting them to help you is part of the research.

Get right as much as you can. Before you hand off a piece of code or writing to someone else -- including another student, your advisor, or a reviewer -- you ought to catch all the problems you can catch by yourself. For a problem that you intend to fix later, include a note to this effect. This allows the other person to focus their limited time on spotting the problems that were beyond your own horizon.

Be a team player. If there are other people on the project, find out what they're working on. Ask plenty of questions. Get a broader sense of the project beyond your own little corner. Help out where you can.

Share what you do. Back up your work, comment your code, log your experiments, and be ready to hand off your code and notes at any time. The project may live on after you. It's not necessary to keep private files. The best plan is to keep everything valuable in a shared version control repository that you, your advisor, and any other collaborators can browse and edit at any time. (A README file in the repository can describe the layout and list any additional resources, e.g., the URLs of a wiki, a Google Doc, etc.) An issue tracker is also useful. Discuss with your advisor how to set up this kind of project infrastructure, e.g., on github.

Avoid diffusion. As a matter of etiquette, try not to spread your work over many different local directories, repositories, email threads, chat logs, Google documents, etc. For example, when sending email, try to continue on an existing thread where appropriate, rather than starting a new one. Your advisor is juggling more email and projects than you, so will find it helpful to keep related things together.

But I Don't Have a Project Yet!

Now that you've read this page, you understand more about how to ask a professor about research opportunities.

When to ask (not too early). Usually you'll need to have taken at least a 300- or 400-level course in the appropriate research area. If you don't know basic concepts and terms, then it is hard to even discuss the research problem. Don't expect the professor to teach you the basics in his/her office: that's what the course is for.

Who to ask. If you are doing extremely well in an upper-level course, then talk to the professor about whether he/she knows of any research opportunities in that area. It helps if the professor already has a high opinion of you from good interactions in class and through office hours. (You did go to office hours just to chat about ideas, right?) Even if he/she doesn't have anything for you, he/she may be able to hook you up with a colleague.

How to ask. Advice from Marie desJardins: "Ask the professor about his/her research. Professors love to talk about their research. But don't just sit there and nod. Listen carefully to what he/she's saying, think about it, and respond." He/She is trying to get a conversation going to assess where you can contribute meaningfully.

To help the professor decide where to start the conversation, be sure to show him/her your resume and your transcript. Also describe the kinds of problems you excel at. Special skills or a remarkable track record may give you a foot in the door. For example, although my main research area is NLP, occasionally I do have problems that don't require much NLP knowledge. Rather, I'm looking for someone who can develop a particular theorem or algorithm, or build a solid piece of system software, or design a beautiful user interface. So in this case, I might consider working with a great student who hasn't taken my NLP course.

How to ask early. If you're not ready to start research yet, it's certainly still okay to ask a professor (or a senior grad student) how you could prepare to do research in his/her area. This might involve taking courses or MOOCs, reading a textbook or papers, or building certain mathematical or programming skills.

When to ask (not too late). Timing is important. Research may not fit neatly into a semester. So approach the professor at least a year before you graduate. This gives you a couple of semesters plus summer and intersession. Hopefully, that's enough time for the professor to find an appropriate role for you and for you to get up to speed, define the problem and approach, do some initial work, refine the ideas, do some more work, fail, think hard, try again, succeed, write and submit a conference paper, revise the paper after acceptance, and present the paper at the conference. It's very common for a research project to take over a year even for a grad student who is doing research full-time!

Speech Communication

- Faculty & Staff Directory

- B.A. Degree Plan: 4 Year Graduation Guarantee

- B.S. Degree Plan: 4 year Graduation Guarantee

- Graduate Studies

- Speech Communication Minor

- Academic Advising

- Lambda Pi Eta Honor Society

- Forensics Team

- Scholarships

- COMM Internship Requirements (COMM 410)

- Alumni and Friends

- Mind Work/Brainstorming

- Constructing a Thesis

- Writing an Introduction

- Supporting a Thesis

- Developing Arguments

- Writing a Conclusion

- Punctuation

- Style and Organization

- What's the purpose of a style manual? How do I choose a style manual for my paper?

- How do I get started planning a research paper? How do I select a topic?

- How does research fit into my writing plan?

- When I write a research paper, what resources should I have on hand?

- Bibliographic Information

- Citation Information

- Title Pages, Headings, Margins, Pagination, and Fonts

- Internet Links/Resources

- OSU Writing Center

- Communication Journals

- Tips on In-Class Writing

- Sample of a Professor's Remarks on a Student Paper

You are here

Sample of a professor's remarks on a student paper.

This section includes a response written by a professor to a student who was working on an independent study project. Reading through the response may provide you a better understanding of the application of concepts mentioned elsewhere on this writing web site. You may be able to apply the professor's comments to your own paper as you edit one of your rough drafts. Always remember: Your professors in Speech Communication are interested in your questions and writing problems. They can be useful resources. If you are invited to contact them for further help, do not hesitate to do so.

Professor's reply to a rough draft written during an independent study:

To the student: Use the following comments to guide you through a close reading of the first few paragraphs of your paper. Edit these paragraphs, and then keep the comments in mind as you read the rest of your paper; apply the comments to other paragraphs when you see similar problems. Avoid simply reading the comments and changing the particular sentence or paragraph named; use the comments to learn how to closely edit your work.

You may have a good idea for an argument in this paper, but the form of the paper is interfering with the reader's ability to understand what constitutes your claim and your support. The argument is not clear. Providing a better organization for the paper can improve the reader's ability to identify the claims you are making and the evidence you present to support those claims. Perhaps some of the following comments will help improve the organization of the paper and make clearer the ideas you are presenting.

Reread the first paragraph of the paper. Rewrite the paragraph to clarify whether this paper is focusing on the rhetoric of the event (eg "lies" and "gave the message that. . . .") or the sociological aspects of the event (eg "not allowing outsiders to participate"). The two are related; rewrite the paragraph to make clear the specific focus and make evident the relationship between the sociology and the rhetoric.

The second paragraph. Notice that the first and second sentences are about the messages of "American society" toward "outsiders." Notice that the third, fourth, and fifth sentences are about something else--a related idea, but not the same idea. Divide this paragraph into two; develop each paragraph completely, but each with a clear central idea.

The third paragraph. Revise this paragraph to repair the following:

- Make the meaning clearer in the first sentence. What do you mean by a parody? Make your intention more explicit.

- Repair the second sentence. It doesn't make sense right now partly because of the "issues" error.

- Repair the third sentence. You begin the sentence with "The questions" but you have not introduced anything as "questions" so the reader doesn't know what you are referencing.

- Rewrite the paragraph either in the third person (where you would refer to "the society" and "Americans") or in the first person (where you would refer to "we"). Don't mix the two.

In the first paragraph on page 2, revise the sentences to use parallel structures. For example, look at the first sentence. When you list the items the paper will cover, you use very different structures for each item. You need to use the same grammatical structure for each. You name the items as "the development of the a new way of life," "what it meant to insiders," "the white versus the black perspective," and "how competition emerged into discontentment." If you use the construction "the development of . . ." in the first item, you need to use a similar construction in all the other items. For example, if you use "the development of . . ." in the first item, you might use "the discrepancy between . . ." in the third item. The point of using like constructions is to help the reader know that these four items all are weighted similarly, that they all are significant parts of the paper, and that they all are components of the rhetorical issue you will discuss. Revise the sentence you wrote in this fourth paragraph to make those four items parallel.

Transitions between paragraphs must be strong to help the reader move from one idea to the next. Look at the beginning sentence in Paragraph 5 ("Competition is a story of . . ."). Rewrite this paragraph to include a better transition from the previous section to this one. Perhaps you will decide to make a division here and use a heading to start this next section. Perhaps you will add a sentence that ties these ideas (the one in Para. 4 and the one in Para. 5) together. Revise the transition between this paragraph and the next.

Paragraph 5 also lacks cohesion. Cohesion is the quality of a paragraph that helps a reader stay on track throughout the idea presented in the paragraph. You can test the cohesion of a paragraph in an easy way. Separate the sentences of the paragraph onto another piece of paper, listing each sentence on a separate line. See if they fit together in any other way. A paragraph with well-developed cohesion cannot be constructed in any other sentence order than the one used without changing words around. In this paragraph, the leaps between sentences are too large; the sentences do not seem to follow one another in a particular order. Part of the problem is that too many ideas are being tied together without explanation of their relationship to one another. Rewrite the paragraph with the intent of improving the cohesion.

Look again at the quotation you used in the third paragraph on the second page. Notice what you said in the sentence just preceding the quotation. Does the information in that sentence agree with the information in the quotation? Revise this paragraph to better match the comments you are making to the comments you are quoting.

One reason your transitions are not working is that the organization of material is not clear. Using these first two pages, write a one-sentence summary of each paragraph. You have 7 paragraphs, so you should have 7 sentences. As you look at these 7 sentences, what pattern do you see? Are the ideas represented in these 7 sentences somehow related? Are some sub-ideas of others? Do they create a star shape? A pyramid? A straight line? Figure out how these ideas relate to one another and then present them in that pattern in the paper. Rewrite these first two pages in an organizational pattern that makes sense to you. Be sure the transitions between the paragraphs reflect that organization. For example, if you see all the ideas equally important, you will want to introduce them saying something like, "Five historical pieces are important to the development of . . ." Then you would present the five pieces, using transitions like, "next," "following that development," or "the last development."

Look back again at the thesis for this paper. Check each of these 7 paragraphs to determine how the idea presented in each paragraph relates to the thesis. Look for signals in the paragraph that tell the reader how to hook this idea to the thesis. If no signals occur, revise the paragraph to include them.

Now look over the first two pages as a whole. See if you can find a direction in which they move. Overall, as a reader reads from page one to page two, where have you moved that reader? Look to the end of your paper. Have you moved the reader far enough in those two pages? Have you moved over the material too quickly? How do you assess the progress you have made in the first two pages toward the goal of the paper?

I hope these comments help you revise your organizational plan to better serve your thesis. Cohesion, transitions, and paragraph development all are important toward making an effective argument in your paper. I believe you have the makings for the argument embedded in this paper; clearly you have thought about this topic and have developed some good ideas. The expression of that argument is not clear; as a consequence, the argument is not effective. It could be. Let me know if I can be of other help.

writingguide-highlight.jpg

Writing Guide Home

- Beginning the Writing

- Editing for Common Errors

- Questions about the Nature of Academic Writing

- Formatting the Paper

- Other Writing Sources

Contact Info

Email: [email protected]

College of Liberal Arts Student Services 214 Bexell Hall 541-737-0561

Deans Office 200 Bexell Hall 541-737-4582

Corvallis, OR 97331-8600

liberalartsosu liberalartsosu liberalartsosu liberalartsosu CLA LinkedIn

School of Communication

E-Mail: School of Communication Contact Form Phone: 541-737-6592 Hours of Operation: 8 a.m. - 5 p.m. Monday - Friday

How to Write a College Research Paper (With Examples)

- by Daniel Friedman

- 9 minute read

Want to know how to write A+ essays from an A+ student? This guide will show you how to write a college research paper perfectly!

Some of the most common assignments you will receive in college are essays. They can be intimidating and time consuming, but they don’t have to be.

I’m going to share with you how I approach essays, from the initial preparation, to how I create an outline which basically writes the essay for me.

Let’s get started!

Before you write your college research paper, it’s essential that you review the guidelines of your essay.

Create a document with the following basic guidelines of the paper:

- The number of sources needed

- Where your sources have to come from

This gives you an easy place to refer back to without reading the whole page of guidelines everytime.

I recommend using the same document to write your outline so you have everything in one place at all times.

Related Post: 10 College Dorm Essentials Every Guys Needs

Research question example.

Writing out your research question (if necessary) or topic up front is really helpful as well. Do a bit of googling on several topics that match your prompt.

For example, if the prompt is to pick a historical event between 1950-1970 which impacted the United States in a negative way and explain the history of the event, how it impacted the US when it occurred, and the effects of the event, you’ll want to begin by looking up historical events between 1950 and 1970 which were impactful for the United States.

From there, choose events which have a lot of research essays, news articles, and papers written about them.

This just makes it a lot easier to find research to back up your essay claims compared to picking a niche topic with only 2 papers written about them.

This will also allow you to create a more original essay because there’s more research to choose from than merely 2 academic essays.

How to Research for a College Paper

To write a college research paper, it boils to down to one main thing… the research.

Often professors will give you guidelines as to where your research must come from. Remember to pay attention to these guidelines and use the databases your professor suggests.

Use databases provided by your university library’s website that match the genre you’re writing about. If it’s a history paper, be sure to use a historical database. Same for political science, english, or any other subject.

Research Example

With the example we’ve been working with, let’s say we chose the Cuban Missile Crisis as our event. I would then type the Cuban Missile Crisis into my database and see what academic papers come up.

There will be LOTS of options with a topic like the Cuban missile crisis which is good.

It can also be a bit daunting, so it may help to add something a little more specific to your search.

For example, searching “Cuban Missile Crisis long term effects on the United States” may give you a better pool of options for the “effects” portion of your essay. Doing the same for each section will help you find the right research papers for your essay.

You will need to read through several research papers. I say need because this is what will help you write MUCH better papers. By reading through a good few papers, you not only gain a much better understanding of what your topic is about, but it helps you figure out which papers are the best for your topic.

Related Post: How to Get Free Textbooks in College

Start taking notes of the papers. This is super important when you need lots of sources.

When more than 5 sources are needed, reading so many papers without taking notes means you will forget everything you’ve read. You can then refer back to these notes and quotes when writing out your essay, and you’ll easily know which source to use for your point and which source to cite.

Keep in mind, your notes don’t have to be crazy. Getting the general idea with a few key points to recite back to is all you need to sort out the best ideas.

How to Create an Effective Outline

Once you know the instructions, the topic, and which research you’ll be pulling from, the next step is an outline. Each outline differs based on what your professor asks of you, but I will give you several examples of different outlines.

Always begin an outline by writing out the basic structure of your paper. Most papers will start with an introduction, followed by several sections/paragraphs depending on the length of your paper, and ending with a conclusion.

For longer essays, the best approach is to create sections. Sections will be titled based on the content, and split up into paragraphs within the section.

Sample College Research Paper Outline

If we continue with the aforementioned example prompt, this is how the sections would be split up:

- Introduction

- Background/history

- The Cuban Missile Crisis (a description of the event and how it impacted the United States)

- Effects of the Cuban Missile Crisis

Your introduction and conclusion should be short. Most professors don’t want a lot of information in those two sections, and prefer instead that you put the bulk of your essay into the main sections.

Your introduction should include the following:

- Your research question/topic

- The context of the event (what’s going on in the United States around the time of the event)

- A brief overview of what your paper talks about.

This includes your thesis!

Your conclusion is merely a summary of what you spoke about in your paper. Do not include new information in your conclusion! Doing so takes away from what the paper was really about and confuses the reader.

In your outline, bullet point these things so you know exactly what to write out in your essay.

Related Post: 10 Time Management Tips for College Students

Creating proper sections.

The most important part of your outline is your sections. This is where you’ll bullet point exactly what you’ll be talking about, and which research/sources you will be pulling from.

Group your sources based on which section they go into. If it’s a good source on the context of your main topic, put it under your background section with your source notes included, and create points based on that research.

This is generally how you should outline your college research paper. By already having your sources, notes from those sources, and creating points based on it, You’ll already have the bulk of your paper mapped out.

Theories and Hypotheses

Some research papers require you to come up with a theory made up of hypotheses. Your hypothesis will be based on your research question if this is the case.

Here’s an example of a research question, and a practical theory created from it:

Research Question – What are the causes of the use of terrorism by the Palestinians and how has its use affected Arab-Israeli relations?

Hypothesis of causes are: a sense of abandonment from the Arab world, humiliation at the hands of Israelis, and demands falling on deaf ears, all of this caused Palestininans to utilize more drastic measures in order to get their needs heard and acted on.

Hypothesis of how its use affected Arab-Israeli relations: Terrorism created more distrust and fearfulness between Israel and Palestine wherein Israelis didn’t and don’t feel comfortable trusting any group of Palestinians due to the extreme actions of several groups, and utilize harsher retaliation or countermeasures as a result of the Palestinian terrorism, pushing both sides farther from cooperation.

A hypothesis is essentially coming up with what you believe the research will prove, and then supporting or contrasting that hypothesis based on what the research proves.

How to Write a Thesis for a College Research Paper

Getting a clear idea of your sections and what they’re about is how to write a college research paper with an effective thesis.

By doing so, your thesis will include the main points of your sections rather than just the names of your sections, which gives a better overview of what your paper is actually about.

You don’t have to create it at the end though. You might find often that you’ll write a thesis at the start and just correct it as your essay points change while writing.

Here’s an example of an A+ thesis in an introduction of an essay:

In the example above, I’ve highlighted the main issue of the poem in blue and the main argument of the poem in red.

Keep in mind, the whole point of a thesis is to explain what your entire paper is going to be discussing/arguing for within 1 or 2 sentences.

As long as you get the issue across along with (more importantly) the main argument of discussion, then your thesis will be formatted perfectly.

Related Post: 10 College Study Hacks Every Student Needs

How to structure a college research paper.

Structuring your paper is fairly simple. Often just asking your professor or TA will give you the best idea of how to structure. But if they don’t give you structure, the best way to go about it is in the way I mentioned before.

Introduction, sections, conclusion. It’s simple and clear cut, and most professors will appreciate that.

Reading through the sources also helps with structure. Often the sequence of events will guide the structure of your paper, so really understanding your topic helps not only with the content of your paper, but with the structure as well.

How to Cite Properly to Avoid Plagiarism

In my experience most professors won’t ask for a specific format in their essay guidelines. This means you’ll want to use whatever you’re most comfortable with.

MLA format is very common amongst most classes. If you didn’t have a clear format you learned in class, or don’t feel particularly comfortable with any one format, I suggest you use MLA.

A quick google search will give you the basic guidelines of MLA. Use this MLA format tool if you’re confused about how to cite sources properly.

Parenthetical Citations

An important part of citing is including parenthetical citations, AKA citing after a quote or paraphrased section.

It’s crucial that you cite ANY quote you use. This also goes for any section where you paraphrase from a source.

Both of these need parenthetical citations right after the direct quote or paraphrase.

Related Post: 10 College Hacks Every Freshman Should Know

Works cited.

The last portion of Citing you need to think about is your works cited or bibliography page. This has all your sources in one place, in the format you’re using.

In order to make this I always use EasyBib . EasyBib will cite your sources for you and create a bibliography with very little effort on your part, and it can be in any format you choose.

Your works cited page will go at the end of your essay, after your conclusion, on a separate page. Not including one means you are plagiarizing , so make sure you don’t forget it!

Hopefully these tips help you how to write a college research paper and better college essays overall.

Take it from an A+ student who can help you achieve the same goal in your college classes.

A huge thanks to Nivi at nivishahamphotography.com for helping out Modern Teen with this incredible post!

If you have any comments, questions, or suggestions leave them below. Thanks for reading!

Daniel Friedman

Hey, I'm Daniel - The owner of Modern Teen! I love sharing everything I've experienced and learned through my teen and college years. I designed this blog to build a community of young adults from all around the world so we can grow together and share our knowledge! Enjoy and Welcome!

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

7 First Day of High School Tips for Freshman to Succeed

10 stylish fall outfits for teenage guys (with pictures), you may also like.

- 6 minute read

25 Best Anything But Clothes Costume Ideas (For Girls & Guys)

- February 9, 2022

- 502 shares 502

- No comments

- 3 minute read

15 Best Holiday Gifts You Have To Get Your Man – Christmas Gift for Men

- October 8, 2019

- 599 shares 599

Research Paper Outline: Designing Your Research Narrative

Table of contents

- 1.1 What is an outline in college papers?

- 2.1 Formatting

- 2.2 Length and detail

- 3 How to Make an Outline for a Research Paper: 4 Essential Tips

- 4 Example of a Research Paper Outline

- 5 How to Make a Research Outline: Final Words

Starting work on the student research paper can be daunting, especially if you have doubts about a topic. A meticulously organized outline serves as a guide through the extensive landscape of knowledge. In this article, you will discover how to make a research paper outline quickly and effectively. These steps will streamline your research and creative process. It will ensure a cohesive and compelling final assignment.

This article delves into the essential aspects of crafting a research paper outline, a foundational tool in academic writing.

- We will explore its primary purpose, providing structure and clarity to your research.

- Key components of a research paper outline, such as formatting with Roman numerals, maintaining a parallel structure, and choosing the right citation style.

- Additionally, we’ll offer insights into balancing the outline’s length and detail to meet assignment requirements and provide effective tips for refining your outline.

Keep reading and find the answers to the most complicated questions about your academic research. Following our advice will give you a high-quality and robust outline for your research paper.

Purpose of the Research Paper Outline

The purpose of an outline for a research paper is paramount to guiding a comprehensive scholarly document. It serves as a roadmap, delineating your research path and ensuring every aspect is noticed. The primary function is to provide a clear and helpful research paper layout.

What is an outline in college papers?

This type of document allows you to present thoughts in a proper order and get needed readers’ reactions. Such an approach helps you avoid confusion while presenting a persuasive case.

Moreover, a customizable research paper outline template proves invaluable for students. It offers a structured format that can be adapted to individual needs. This adaptability enables students to concentrate on the substance of their analysis. Recognizing that activity when you create a research paper outline can be challenging. However, having all the facts and results empowers you to create essays quickly and effectively. That’s why there is no basic research paper outline. This piece of paper is always unique!

Crucially, the utility of an assignment extends beyond mere structural guidance. It serves as a record-keeping tool, allowing you to track and manage the citations mentioned in your essay meticulously. A well-crafted outline of a research paper becomes an indispensable tool. In the subsequent sections, we will discuss the intricacies of constructing a good research paper outline. It will meet the main criteria and elevate the quality and impact of your academic results.

Key Components of Research Paper Outline

Writing a research paper outline is a pivotal phase in the creative process. It furnishes a guide to navigating the complexities of students’ work. The foundational framework often comprises three main elements: a draft, a list of cited works, and an abstract. The comprehensive plan encompasses various elements crucial for a well-rounded and organized academic document. Title page: This page includes the title, author’s name, educational institution, and publication date. It serves as the first impression, offering an academic snapshot. Abstract: This part shows essential discoveries and their connection to earlier research. A well-crafted abstract is concise, focusing on the primary thoughts described in the study. It provides a brief yet comprehensive overview, enticing readers to delve deeper into the text. First part: Sets the stage with background information leading to the central argument. The opening should engage the reader’s curiosity and offer a background for studying the subject. Body: Encompassing various sections such as methods, materials, discoveries, and your views and suggestions, this segment constitutes the essence of the college paper. Here, you will find an exposition of the investigation methods employed, the gathered discoveries, the obtained results, and a reflective discussion of the new information. Last part: Restates the argument, reaffirming the study’s importance and relevance. It should convey that the research has achieved its mission and summarize key takeaways. References/Bibliography: Lists all cited works, encompassing both directly quoted and paraphrased sources. Obviously, adherence to a specified formatting style (e.g., MLA format research paper outline, APA, Harvard) is crucial. Additional resources: Incorporates additional elements such as tables, charts, figures, and specialized terminology. These additions enhance the presentation of data and help a deeper discussion of the topic.

Research essay outlines can be formal or informal. Formal ones are typically submitted to professors during the early stages of writing. Informal outlines serve as drafts where students jot down their initial ideas.

Clarity and organization are paramount when you set up a research paper. A meticulously organized plan is a foundational tool for guiding the writer through the intricacies of academic inquiry. Besides, it streamlines the process of writing an outline for a research paper, it also makes your assignment emerge as a compelling and great contribution. If you need help, you can always ask for support from research paper writers .

Formatting is crucial to crafting a research paper outline and creates a framework for your thoughts. Here are key considerations for the outline format for the research paper:

- Roman numerals, letters, and numbers: use Roman numerals (I, II, III) for main sections, capital letters (A, B, C) for subsections, and Arabic numerals (1, 2, 3) for further divisions. This tiered structure visually arranges the outline, offering a guide for the reader.

- Sustaining parallel structure: guaranteeing grammatical structure and formatting uniformity across the outline, heightening readability and coherence. Thus, it will foster an easier comprehension of the progression of your ideas.

- Selecting a citation style: select a specific citation style as per the requirements set by the professor. For example, the teacher tells you to use a research paper outline in Chicago style. Common styles include APA, MLA, Chicago, and others. Adhering to a particular style maintains consistency in referencing sources. It contributes to professionalism.

There are several standards you need to consider during formatting. Have you written everything according to the APA research paper outline style? Look at the research paper format numbering. For example, by employing Roman numerals, letters, and numbers, maintaining parallel structure, and adhering to a designated citation style, you not only enhance the visual appeal of your plan but also demonstrate a commitment to precision and scholarly standards. Indeed, constant style is integral to presenting your research cohesively and professionally.

Length and detail

Striking a delicate balance between consciousness and information is critical, particularly when creating an outline for a research paper. Besides, tailoring the level of detail to match assignment requirements is essential too. Some projects call for a comprehensive and detailed outline. They provide a thorough roadmap for the entire research paper. Conversely, other assignments may benefit from a more brief approach.

If you don’t have time and need help with outline specifics, you can always purchase a research paper online from well-versed professionals.

How to Make an Outline for a Research Paper: 4 Essential Tips

Creating an effective plan for a research paper is an unfast process. It requires a focus on detail and adaptability. There is no basic outline for a research paper. Yet, it must be specific. Here are some tips to enhance your outline-writing skills:

- Frequent Revisions:

Treat your research outline as a dynamic document. Frequently review and revise it as your research advances and your comprehension deepens. This iterative method guarantees that your plan stays in sync with the evolving structure of your research paper .

- Be Specific:

Add specificity to your topic outline for the research paper. Accordingly, begin a research paper with the main idea. Precisely express the primary concepts in each section, strengthening them with relevant particulars. Thus, understandable subpoints steer your writing process, contributing to the coherence and depth of your research paper.

- Detail or Conciseness:

Strive for a balance between detail and conciseness. That is why adding sufficient information to guide your writing is crucial. Avoid overwhelming your detailed outline for a research paper with unnecessary information. Consequently, keep it focused on the key elements to maintain clarity and coherence.

- Be Flexible: