Doctoral Program FAQs

Candidates who do not have backgrounds in one of the School of Design's area of focus (Communication Design, Product Design, Interaction Design, UX design, Environments Design, Service Design, Design for Social Innovation, design research, design theory) would not be eligible for Teaching Fellowships. They may, however, be considered for the self-funded PhD option. Additional study, such as the School’s MA, MPS or MDes degree could make such candidates eligible for PhD Teaching Fellowships. Please contact us for advice on this matter.

Yes. Candidates with expertise on housing, interiors and smaller-scale architecture and an interest in Transition Design may apply and help the School build out its offerings in Environments Design.

No. The Human Computer Interaction Institute offers a PhD with pathways in Interaction Design. Consequently, applicants with research topics and approaches that demand significant amounts of coding or more cognitive science based research methods will be encouraged to apply to HCII.

In some cases, 3+ years of high-level professional design experience, demonstrated with a portfolio and a well-formulated research proposal may meet the application requirements.

In some cases, yes. Applicants with backgrounds in Business and Management, but with additional expertise and experience in Design, and who are interested in Transition Design, should apply to this program and will be encouraged to seek faculty advisers from other areas on campus. We would be particularly interested in candidates with business and management expertise related to Transition Design such as circular economies, sustainable design, and B corps.

Carnegie Mellon is a highly ranked research university and there are potential advisors from a wide range of disciplines on the campus. We also have a network of potential advisors who are based in other institutions.

No. The language requirements for application to the program cannot be waived. Please review these carefully.

No. Unfortunately we do not have the ability to review portfolio materials for each inquiry that we receive. To be considered for the program you will need to formally apply.

No. We do not currently offer an online option for our PhD degree. We hope to eventually offer a part time PhD degree but it is not an option at this time.

No. The only funding opportunity available is the Teaching Fellowship which requires students to teach 1-2 courses during the academic year.

We use technologies, such as cookies, to customize content and advertising, to provide social media features, and to analyze traffic to the site. By using or registering on any portion of this site, you agree to our privacy and cookie statement.

- PhD in Design

The first PhD in design program in the US, Institute of Design’s PhD is a top-rated graduate program for those seeking to teach or conduct fundamental research in the field. Our PhD alumni have gone on to lead noted design programs at universities all over the world and lead practices at global corporations.

By pursuing rigorous research in an area that aligns with work by our PhD faculty, you’ll work directly in some of the most exciting design-focused work being done today. To learn more about research at ID and our PhD in Design, complete this form .

PhD Faculty Advisors

Weslynne ashton.

Professor of Environmental Management and Sustainability & Food Systems Action Lab Co-Director

Anijo Mathew

Dean, Professor of Entrepreneurship and Urban Technology, & ID Academy Director

Assistant Professor of Data-Driven Design

Ruth Schmidt

Associate Professor of Behavioral Design

Carlos Teixeira

Charles L. Owen Professor of Systems Design and PhD Program Director

Degree Requirements

All PhD students will work closely with their advisors to plan their course of study and research. Students complete a total of 92 credit hours:

- Up to 32 credits can be transferred from a master’s program

- 12 course credits

- 48 research credits

Courses may be selected from across the university’s course offerings to complement the objectives of the student’s program.

Admitted doctoral students will be required to submit and obtain approval for a program of study. Within two years of being admitted, students take a comprehensive examination, after which, students will be considered candidates for the PhD degree.

The research component of the program grows as the student progresses. The dissertation created from this work is intended to create a substantial and original contribution to design knowledge.

Featured Courses

Phd principles & methods of design research, phd research and thesis, phd philosophical context of design research, student work, future archetypes of ev charging, exploring controlled environment agriculture, partnership with city clerk’s office aims to reform fines and fees, phd corporate partnership initiative.

Designed for professionals who want to reach the next level of design leadership, ID’s PhD Corporate Partnership provides candidates and organizations the tools and techniques needed to grow leadership and innovation within your organization.

Candidates should have a master’s degree in design (or equivalent) and/or significant experience as a professional designer.

A Global Network

Across the entire school, ID alumni make up a strong network—a uniquely skilled set of more than 2,400 people across 32+ countries who deal with difficult issues and navigate them with clarity, purpose, and discipline.

Alumni Hiighlights

Jessica meharry, phd, associate professor, columbia college chicago, id’s phds make their mark, andré nogueira, co-founder and deputy director of the design laboratory at the harvard t.h. chan school of public health, estimated costs.

Tuition and research stipends are extremely limited. Only self-funded applicants will be considered.

Fall 2024 Admission

January 19, 2024 (priority admission) March 1, 2024 (final general admission)

Spring 2025 Admission

October 26, 2024 (final admission)

Request More Info

Request more information.

Please complete the form to request more information or if you have additional questions regarding our application process or requirements.

For Learners

- Graduate School

- Master of Design

- Master of Design + MBA

- Master of Design + MPA

- Master of Design Methods

- Career Support

For Organizations

- Executive Academy

- PhD Corporate Partnerships

- Hire from ID

For Everyone

- Action Labs

- Equitable Healthcare

- Food Systems

- Sustainable Solutions

- More Ways to Partner

- Mission & Values

- The New Bauhaus

- ID Experience

- ID & Chicago

- Faculty & Staff

- News & Stories

- End of Year Show

- Lucas J. Daniel Series in Sustainable Systems

- Latham 2024–25

- From the Dean

- Faculty and Staff Directory

- Strategic Plan 2022-2027

- History of the College

- Initiative for Community Growth and Development

- Architecture

- Design Studies

- Graphic and Experience Design

- Industrial Design

- Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning

- Media Arts, Design and Technology

Doctor of Design

- Ph.D. in Design

- Undergraduate Programs

- Masters Programs

Doctoral Programs

- Graduate Certificates

- Schedule a Tour

- Research Initiatives and Labs

- Student Enrichment

- Design Lab for K-12 Education

- Design Ambassadors

- Student Organizations

- IT Resources

- Materials Lab

- Career Resources

- Study Abroad

- The Student Publication

- Design + Build

- First Year Experience

- Sponsored Studios

- Get Involved

- Alumni and Friends Receptions

- Leaders Council

- Leaders Council Members

- College of Design Awards

- Designlife Award Gala

- Support the College

- Contact the Development Team

- Ways to Give

- News and Events

- Calendar of Events

- NC State Creatives Video Series

- Designlife Podcast

- Lectures and Educational Programs

- Designlife Magazine

- Newsletter Signup

Join a premier group of graduate students from twenty-four countries who are preparing to shape the world by addressing the complex challenges facing society through design practice and research.

Experts in the Field

The College of Design offers two distinct doctoral programs aimed at broadening student knowledge within the design field.

PhD in Design

The PhD in Design is an on-campus program intended for students who seek to deepen their knowledge of both theory and research. The PhD in Design program offers very generous financial support including: tuition, insurance, travel support, and a stipend. All majors, freshmen through doctoral students, have dedicated studio space with 24-hour access. Lab spaces are state-of-the-art, and the College of Design facilities are among the best in the nation.

The Doctor of Design program is a distance education program for established practicing professionals working with creative and case-based research problems who intend to apply the results of their studies to design practice. DDes students conduct original investigations through design-based practices, cases, and methods. The program provides a forum for connecting design research to the needs of society, by promoting the application of new knowledge in design and addressing design impacts on larger systems.

Recent News

April 01, 2024

M. Elen Deming Honored for Exceptional Service to CELA and LAF

Educator and researcher M. Elen Deming was presented with the Forster Ndubisi Professional Service Award at the Council of Educators in Landscape Architecture (CELA) Dinner on March 22, 2024.

December 12, 2023

Breaking the Stereotype: Using AI to Support Diversity in STEM

Ashley Anderson’s research looks at why there aren’t as many Black students earning degrees in STEM fields, and is looking at how generative AI can be used a tool to foster diversity and belonging.

May 10, 2023

College of Design Faculty win NC State Awards in Teaching and Research

Six College of Design faculty were recognized with awards from the Alumni Association, Graduate School, Libraries and Office of the Provost this spring.

Additional Resources

- Admissions

- First Year Admissions

- On-Campus Transfer

- Off-Campus Transfer

- Master’s Programs

- Doctoral Programs

- Graduate Certificates

- Schedule a Tour

- Financial Aid

Frequently searched items

- Director's Message

- History of NID

- NID Act, Rules, Ordinances And Statutes

- Annual Reports

- International Programmes

- Knowledge Management Centre

- Network & Linkages

- Centre for Teaching and Learning

- Academic Notifications

Curriculum Objectives

- Admission Process

- Life at NID

- Governing Council

- Continuing Education Programme

- Integrated Design Services

- Intellectual Property Rights Cell

- Innovation Center for Natural Fiber

- International Centre for Indian Crafts (ICIC)

- Center for Bamboo Initiatives

- Railway Design Center

- Smart Handloom Innovation Centre

Attention! Deadline for application to 2024 PhD Admissions approaching: 28 March! APPLY NOW

New!!!!! SAGE Fellowships for full-time doctoral applicants. Read in section on SAGE Fellowships .

NID’s doctoral program

In pursuit of its continued commitment to Design research, NID started a doctoral programme in Design in the year 2017. The goal was to take a step further from the practice of Design so well pursued in its Bachelors and Masters programs into the world of advanced and detailed in-depth research study of particular aspects of Design that might hitherto not have been studied. NID’s PhD programme in Design aims to promote deep reflection, inquiry, and rigour in the development and dissemination of new ideas, expressions and skills in the field of Design and allied fields and contribute new theories and knowledge to Design, Design education and Design practice.

A Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) degree in Design is awarded at NID for advanced study of the creation of innovative solutions/ approaches/ methods/ interfaces for products/ communications/ services/ experiences along with an accompanying thesis that extends the body of knowledge of application of design thinking, process, and practice.

The programme is open to educators and professionals in design and allied fields who wish to reinvent their own practice or knowledge base while pushing the boundaries of the discipline through innovation in practice and create new design theories. The PhD programme at NID aims to be a national and international benchmark for doctoral research in design.

With the scholars of the first batch now graduating with their doctoral degrees, the program is drawing more and more applicants for doctoral pursuit in Design.

Practice- vs Theory-led doctoral research in Design

The PhD programme in Design at NID may be undertaken in one of the following modes:

Practice-led Research: Original investigation undertaken in order to gain new knowledge mostly by means of practice and the outcomes of that practice. Such research includes practice as an integral part of its method and often falls within the general area of action research outcomes accompanied by substantiated claims of originality and contribution to knowledge. Creative outcomes may be in the form of artefacts such as objects, images, film, fashion, music, Design collections, models, samples, prototypes, digital media, performances and exhibitions or other outcomes. The doctoral submissions for this kind of research must include contextualisation of the creative work.

Theory-led Research: Such research would be concerned with the nature of practice and lead to new knowledge that has operational significance for that practice. The main focus is to advance knowledge about practice, or to advance knowledge within practice. Such research may be fully described in text form in the doctoral thesis.

Part-time vs Full-time engagement

The PhD programme is allowed to be taken up in part-time or full-time formats.

Residence: Full-time candidates are required to be present on campus throughout the duration of their doctoral study period.

Duration: The maximum duration allowed for a full-time candidate is 3 years, which can be extended upto 5 years upon formal application by the candidate and endorsement by their guide and co-guide.

Eligibility for financial support: Occasionally the Institute might make announcements of financial support if sources make such support available. On such occasions only full-time candidates are eligible to apply for the support.

Attention: SAGE Fellowships for full-time doctoral applicants

Read in section on SAGE Fellowships .

Residence: Part-time candidates are required to be present on campus for the duration of scheduled coursework, seminars, and other academic requirements that are declared to be held in person.

Duration: The maximum duration allowed for a full-time candidate is 5 years, which can be extended upto 7 years upon formal application by the candidate and endorsement by their guide and co-guide.

Employer’s No-Objection Certificate: Working professionals in employment elsewhere and seeking admission to the part-time PhD programme are required to obtain a No-Objection Certificate (NOC) from their employer, stating that the employer has no objection to the employee pursuing a PhD from the Institute, and that the employee will be available in person or online as the Institute may require for doctoral consultations with the guide, for all Institute coursework, periodic seminars and presentations, as the case may be, and will fulfil residential requirements as per the Institute’s requirements. This certificate should be submitted no later than acceptance of offer of admission if made.

Eligibility for financial support: Part-time candidates would NOT be eligible for ANY financial support from the Institute.

Part-time candidates shall also be governed by all rules and regulations of the Institute.

NID-HSLU Cooperation PhD Program

In the year 2022 NID entered into an agreement with Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts—School of Design, Film and Art (HSLU), Switzerland, to offer an NID-HSLU PhD Cooperation program separate from its own PhD program alluded to above, on the theme Eco-Social Innovation by Design . This program is open to people worldwide to apply. A common portal is used for application to both programs. Information on this program is available on the website https://www.hslu.ch/en/lucerne-school-of-art-and-design/research/doctorate/phd-programme-eco-social-innovation-by-design/ .

The SAGE PhD Fellowship

NID is pleased to offer one (1) full-time PhD Fellowship on the topic of Biopackaging through the SAGE PhD Fellows program of Echo Network of Bangalore, a Denmark-based organisation that works with the Nordic Centre of India to promote research on Sustainability. Research proposals are invited for this Fellowship opportunity.

The terms of this Fellowship are as follows:

- This Fellowship would be available for research only on the topic of Biopackaging . The research must also relate to the field of Design and thus make a contribution to theoretical knowledge of the two fields (Design and Biopackaging) combined.

- The Fellowship would be available only to full-time candidates . The candidate would be required to fulfil physical attendance requirements at NID's Ahmedabad campus for the entire duration of their doctoral study.

- The Fellowship would be available for three (3) years . If more time is required for the research work to be completed, the candidate could apply for it (extending the duration upto a maximum of 5 years) but the duration of funding is limited to 3 years.

- The fellowship would include a stipend for living expenses in Ahmedabad, tuition fees of the PhD program, and all costs (eg, travel, conferences, material) related to the research being conducted.

- The candidate on this Fellowship is required to spend up to 7 months in Denmark (over the three-year Fellowship period) working with Danish institutes associated with Echo Network on this project. The costs of this would be covered in addition to the fellowship.

- Applicants to this Fellowship must clearly include the following in the title of their research proposals: “Application for SAGE Fellowship” to indicate their intent of applying for the fellowship. Absence of this phrase in the title would be taken to mean that the applicant does not wish to be considered for the fellowship even if the topic is related to Biopackaging.

- Only one (1) position is available for the Fellowship.

- Applicants for the Fellowship would go through the same Admissions process as that published in the Admissions Handbook for 2024.

- The candidate who is awarded the Fellowship would be required to go through all the academic processes of all doctoral students of NID during their doctoral tenure at the Institute.

Disciplines

The PhD programme in Design will include:

- Original investigation undertaken through a design project, in order to gain new knowledge by means of practice and the outcomes of that practice. Claims of originality and contribution to knowledge may be demonstrated through creative outcomes, which may include artefacts such as objects, images, film, fashion, music, design collections, models, samples, prototypes, digital media or other outcomes such as performances and exhibitions. Doctoral submissions for this kind of research must include a contextualisation of the creative work. A written/video thesis will form a part of the dissertation,which shall be in a dialogic and analytic relation to the outcome, with a suitable articulation of the objective, methods, process and findings.

- The research may also be concerned with the nature of practice and lead to new knowledge that has operational significance for that practice. The main focus of this kind of research shall be to advance knowledge about practice or to advance knowledge within practice. The results of the research, in this case, may be fully described in text form in the doctoral thesis.

The programme shall promote the accumulation and application of diverse research methods that should be customised as per Indian variables and the context of Indian socio-cultural heritage and should be relevant to the needs of the country. The main emphasis of the programme will be the generation of new knowledge through testing and implementing new materials, techniques, processes and design ideas. The programme will nurture design thinking as an inquiry-based field of research and knowledge production that, in turn, inform better design practices.

The PhD programme in Design aims to promote deep reflection, inquiry, and rigor in the development and dissemination of new ideas, expressions and skills in the field of design and allied fields and shall lead to their meaningful manifestations in the form of new design collections, objects, communication, services, strategies, etc. The work shall contribute new theories and knowledge to design, design education and design practice.

The purpose of the programme is to support the creation of products or services that improve the quality of life of people, meet demands to sustain the environment, improve policymaking; and better the understanding and use of design in industry, education and society at large.

To foster original research and create new knowledge about the nature and practice of design.

To engage in a deeperunderstanding of expressions, methods and the role of design in problem solving activity.

To foster NID’s pedagogic principlesof ‘Learning to Know’and ‘Learning to Do’alongside itscore ideals and culture.

To enable collaboration in research, scholarship, design development and service.

To enable students to engage in advanced research and practice with design theorists and practitioners in a broad varietyof fields.

To contribute towards the Institute’s objective of design for dignity and service to society, and to participate in meaningful design for change and sustainability.

How to Apply

Admission to the PhD programme at NID as well as to the NID-HSLU Cooperation program is conducted annually, through NID’s Admissions portal https://admissions.nid.edu . The admission process is a multi-stage one consisting of the following steps:

- Submission of application form. The applicant must fill out the form for PhD Admissions on the link above. If the applicant wishes to apply to both, the PhD programme at NID and the NID-HSLU Cooperation program, separate applications (with different email ids) must be made for the two.

The application process is completed with payment of application fee. Once the payment is made, the information in the application may only be changed in a small Edit Window provided between 29 Mar and 31 Mar on payment of a processing fee.

- Screening of applications on the basis of educational qualification. The applicant’s qualifications have to abide by the requirements mentioned in Section 5 of the Admissions Handbook 2024-25 . Deviation from them would be cause for rejection of application.

- Scrutiny of research proposal submitted. As part of the application, submission of a research proposal is required. The proposals of eligible candidates would be evaluated on criteria mentioned in the Admissions Handbook.

Attention! Research proposals are especially invited on the topic of Bio-packaging, for which a funding opportunity in the form of the SAGE PhD Fellowship is available. Please read about this in the section on SAGE Fellowship . This opportunity is available only to applicants to NID’s PhD Program, not to the NID-HSLU Cooperation Program.

- Passing of the Doctoral Research Test (DRT). This test is required to be taken by all applicants who are less than 15 years from their basic educational qualification.

- Interview. Candidates who pass the DRT would be interviewed by a selection panel appointed by NID.

The candidates who pass the interview stage would be ranked according to merit and the top 12 would be made offers of admission. All government norms that apply (eg, reservation based on caste and disability) would be followed in the process.

- Schools & departments

Design PhD, MPhil

Awards: PhD, MPhil

Study modes: Part-time, Full-time

Funding opportunities

Programme website: Design

Discovery Day

Join us online on 18th April to learn more about postgraduate study at Edinburgh

View sessions and register

Research profile

Design research is part of a dynamic and supportive environment within a vibrant community of world-class research. Design research integrates practice and theory within a dynamic and supportive environment. It connects across disciplines and research initiatives to support doctoral study within a vibrant community of world-class research. The range of subjects possible is vast and includes but is not limited to:

- Design anthropology

- Design history and theory

- Methodological development

- Design informatics

- Design for healthcare and wellbeing

- Design management

- Craft studies

- Service design

- Design for change (transition and transformation)

- Cultural and heritage studies

- Sustainability and the circular economy

- Design Cultures

- Design and Digital Media

You will also be supported through our practice specialisms (in theory or practice) in:

- Film and television

- Graphic design

- Illustration

- Performance costume

- Product design

- Screen studies (film and animation)

- Silversmithing

Programme structure

You can undertake the Design MPhil or PhD programme either as a practice-based programme of research, or theory based. And it is possible to change between approaches during your programme of study.

The PhD programme comprises three years of full-time (six years part-time) research under the supervision of an expert in your chosen research topic within Design. If you study by theory then the period of research culminates in a supervised thesis of up to a maximum of 100,000 words. For the practice-based approach your research would culminate in a portfolio of artefacts or artworks which would be accompanied by a thesis of up to a maximum of 50,000 words.

The MPhil programme comprises two years of full-time (four years part-time) research under the supervision of an expert in your chosen research topic within Design. If you study by theory then the period of research culminates in a supervised thesis of up to a maximum of 60,000 words. For the practice-based approach your research would culminate in a portfolio of artefacts or artworks which should be accompanied by a thesis of up to a maximum of 20,000 words.

Regular individual meetings with your supervisor provide guidance and focus for the course of research you are undertaking.

You will be encouraged to attend research methods courses at the beginning of your research studies.

And for every year you are enrolled on programme you will be required to complete an annual progression review.

Training and support

All of our research students benefit from Edinburgh College of Art's interdisciplinary approach, and you will be assigned at least two research supervisors.

Your first/ lead supervisor would normally be based in the same subject area as your degree programme. Your second supervisor may be from another discipline within Edinburgh College of Art or elsewhere within the University of Edinburgh, according to the expertise required. On occasion more than two supervisors will be assigned, particularly where the degree brings together multiple disciplines.

Our research culture is supported by seminars and public lecture programmes and discussion groups.

Tutoring opportunities will be advertised to the postgraduate research community, which you can apply for should you wish to gain some teaching experience during your studies. But you are not normally advised to undertake tutoring work in the first year of your research studies, while your main focus should be on establishing the direction of your research.

You are encouraged to attend courses at the Institute for Academic Development ( IAD ), where all staff and students at the University of Edinburgh are supported through a range of training opportunities, including:

- short courses in compiling literature reviews

- writing in a second language

- preparing for your viva

The Scottish Graduate School for Arts and Humanities ( SGSAH ) offers further opportunities for development. You will also be encouraged to refer to the Vitae research development framework as you grow into a professional researcher.

You will have access to study space (some of which are 24-hour access), studios and workshops at Edinburgh College of Art’s campus, as well as University wide resources. There are several bookable spaces for the development of exhibitions, workshops or seminars. And you will have access to well-equipped multimedia laboratories, photography and exhibition facilities, shared recording space, access to recording equipment available through Bookit the equipment loan booking system.

You will have access to high quality library facilities. Within the University of Edinburgh, there are three libraries; the Main Library, the ECA library and the Art and Architecture Library. The Centre for Research Collections which holds the University of Edinburgh’s historic collections is also located in the Main Library.

The Talbot Rice Gallery is a public art gallery of the University of Edinburgh and part of Edinburgh College of Art, which is committed to exploring what the University of Edinburgh can contribute to contemporary art practice today and into the future. You will also have access to the extraordinary range and quality of exhibitions and events associated with a leading college of art situated within a world-class research-intensive University.

St Cecilia’s Hall which is Scotland’s oldest purpose-built concert hall also houses the Music Museum which holds one of the most important historic musical instrument collections anywhere in the world.

In addition to the University’s facilities you will also be able to access wider resources within the City of Edinburgh. Including but not limited to; National Library of Scotland, Scottish Studies Library and Digital Archives, City of Edinburgh Libraries, Historic Environment Scotland and the National Trust for Scotland.

You will also benefit from the University of Edinburgh’s extensive range of student support facilities provided, including student societies, accommodation, wellbeing and support services.

PhD by Distance option

The PhD by Distance is available to suitably qualified applicants in all the same areas as our on-campus programmes.

The PhD by Distance allows students who do not wish to commit to basing themselves in Edinburgh to study for a PhD in an ECA subject area from their home country or city.

There is no expectation that students studying for an ECA PhD by Distance study mode should visit Edinburgh during their period of study. However, short term visits for particular activities could be considered on a case-by-case basis.

- For further information on the PhD by Distance, please see the ECA website

Entry requirements

These entry requirements are for the 2024/25 academic year and requirements for future academic years may differ. Entry requirements for the 2025/26 academic year will be published on 1 Oct 2024.

Normally a UK 2:1 honours degree or its international equivalent. If you do not meet the academic entry requirements, we may still consider your application on the basis of relevant professional experience.

You must also submit a research proposal; see How to Apply section for guidance.

If your research is practice-based a portfolio should also be submitted; see How to Apply section for guidance.

International qualifications

Check whether your international qualifications meet our general entry requirements:

- Entry requirements by country

- English language requirements

Regardless of your nationality or country of residence, you must demonstrate a level of English language competency at a level that will enable you to succeed in your studies.

English language tests

We accept the following English language qualifications at the grades specified:

- IELTS Academic: total 7.0 with at least 6.0 in each component. We do not accept IELTS One Skill Retake to meet our English language requirements.

- TOEFL-iBT (including Home Edition): total 100 with at least 20 in each component. We do not accept TOEFL MyBest Score to meet our English language requirements.

- C1 Advanced ( CAE ) / C2 Proficiency ( CPE ): total 185 with at least 169 in each component.

- Trinity ISE : ISE III with passes in all four components.

- PTE Academic: total 70 with at least 59 in each component.

Your English language qualification must be no more than three and a half years old from the start date of the programme you are applying to study, unless you are using IELTS , TOEFL, Trinity ISE or PTE , in which case it must be no more than two years old.

Degrees taught and assessed in English

We also accept an undergraduate or postgraduate degree that has been taught and assessed in English in a majority English speaking country, as defined by UK Visas and Immigration:

- UKVI list of majority English speaking countries

We also accept a degree that has been taught and assessed in English from a university on our list of approved universities in non-majority English speaking countries (non-MESC).

- Approved universities in non-MESC

If you are not a national of a majority English speaking country, then your degree must be no more than five years old* at the beginning of your programme of study. (*Revised 05 March 2024 to extend degree validity to five years.)

Find out more about our language requirements:

Fees and costs

Tuition fees, scholarships and funding, featured funding.

- Edinburgh College of Art scholarships

UK government postgraduate loans

If you live in the UK, you may be able to apply for a postgraduate loan from one of the UK’s governments.

The type and amount of financial support you are eligible for will depend on:

- your programme

- the duration of your studies

- your tuition fee status

Programmes studied on a part-time intermittent basis are not eligible.

- UK government and other external funding

Other funding opportunities

Search for scholarships and funding opportunities:

- Search for funding

Further information

- Edinburgh College of Art Postgraduate Research Team

- Phone: +44 (0)131 651 5741

- Contact: [email protected]

- Postgraduate Research Director, Design, Dr Craig Martin

- Contact: [email protected]

- Edinburgh College of Art Postgraduate Office Student and Academic Support Service

- The University of Edinburgh

- Evolution House, 78 West Port

- Central Campus

- Programme: Design

- School: Edinburgh College of Art

- College: Arts, Humanities & Social Sciences

Select your programme and preferred start date to begin your application.

PhD Design by Distance - 6 Years (Part-time)

Phd design by distance - 3 years (full-time), phd design - 3 years (full-time), phd design - 6 years (part-time), mphil design - 2 years (full-time), mphil design - 4 years (part-time), application deadlines.

If you are applying for funding or will require a visa then we strongly recommend you apply as early as possible. All applications must be received by the deadlines listed above.

- How to apply

You must submit two references with your application.

One of your references must be an academic reference and preferably from your most recent studies.

You should submit a research proposal that outlines your project's aims, context, process and product/outcome. Read the application guidance before you apply. If you wish to undertake research that involves practice then a portfolio will also be required, full details are listed in the application guidance document.

- Preparing your application - postgraduate research degrees (PDF)

Find out more about the general application process for postgraduate programmes:

Imperial College London Imperial College London

Latest news.

Imperial wins University Challenge for historic fifth time

Innovators of the future to compete in Venture Catalyst Challenge final

Long COVID leaves telltale traces in the blood

- Dyson School of Design Engineering

- Faculty of Engineering

- Departments, institutes and centres

- Study With Us

- Postgraduate Research (PhD)

Applying for a PhD in Design Engineering

All applications to the Design Engineering PhD Programme are made online via the Imperial College Application System . Please see below for a step-by-step guide on what you need to do to apply.

- Check the entry requirements below to ensure you meet the minimum entry criteria for research.

- You need to determine a potential supervisor before submitting an application. Please see here for our current academic and teaching staff to identify topics of interest and an appropriate supervisor in the department.

- Contact your proposed supervisor to devise and discuss your potential PhD project. You can find their contact email address in their profile on the academic and teaching staff page.

- Consider how you will fund your PhD - both tuition fees and living costs. You can find information on the College's tuition fees here , and information on scholarships available here . Please also consult the 'Funding your PhD page' here for more information.

- Make your official PhD application via the Application system . Make sure you state your chosen topic and supervisor(s) on the form and details of any department/College funding you may be applying for, as well as attaching all necessary documents. Please note that we do not accept applications that do not detail a proposed supervisor or a research topic. Once submitted, you can monitor the status of your application in the portal.

- If successful, your proposed supervisor will contact you to arrange an interview. Following the interview, your proposed supervisor will inform you whether they would like to offer you a PhD position and/or nominate you for funding (if appropriate).

PhD applications can be made all year-round. However, we encourage you to apply as early as possible. Specific application deadlines apply if applicants would like to be considered for certain scholarships. Such deadlines are driven by the funding requirements. Please refer to the application deadlines highlighted on the Imperial College Scholarship page for full details.

For general information about joining us to do PhD research, please refer to the online postgraduate prospectus.

Additional Information for the Application Process

Entrance requirements.

Design Engineering requires higher than the minimum Imperial College entry requirements; our PhD applicants are expected to have a First Class (Distinction) Degree or equivalent at Masters level in a relevant engineering, design or scientific discipline. In exceptional cases where extensive research/industry experience can be demonstrated, candidates with a UK-equivalent of 2:1 (Merit) at Masters level can be considered.

As part of the application process applicants will need to show that they have met the College’s English-language requirements. Details can be found here .

Candidates with study up to Bachelors degree level will not normally be considered without evidence of significant industrial, research, or field experience. However, they are welcome to apply for our Master's Degrees, Innovation Design Engineering and Global Innovation Design .

If your undergraduate and/or master's qualifications are from overseas institutions, please see here for information on international grade equivalencies and how they relate to the Imperial College entry requirements.

International Applicants

If you are applying to the PhD Programme as an overseas student, there are a number of additional requirements you may need to fulfil as part of the application process:

- Meeting the College's English language requirements .

- Securing a tier 4 student visa to study in the UK.

- Most nationals who require immigration permission to be in the UK and intend to study an Engineering PhD will require ATAS clearance. Further information on this is available here . Please note that nationals from the EU, EEA, Switzerland, Australia, Canada, Japan, New Zealand, Singapore, South Korea and the USA are NOT required to have ATAS clearance (as of 5th October 2020). The CAH code used in ATAS applications for Design Engineering is CAH10-01-01.

Submitting your Application

You should apply online using the College's application portal. Please keep in mind the following:

- Enter ‘Design Engineering Research’ in the programme title field on the application form

- Start your application as early as possible

- Many studentships have application deadlines well ahead of your planned start date

- Sponsors will be more impressed if you can show you already meet our requirements

As part of the application, you will need to upload the following supporting documents:

- Degree transcripts

- 2 references

- Evidence of your English language qualifications (where applicable)

- A short personal statement and/or a research proposal (maximum 1-2 pages)

The main thing to keep in mind is to answer the following questions:

- What is your motivation to undertake a PhD and why now?

- Why Imperial and why Design Engineering? Why this particular research team?

- What is your research question or what is the area you are interested in? What is the need/gap for this research?

Preparing for Interviews

All applicants must be interviewed before a formal offer of admission can be made. This interview will be conducted by at least 2 members of academic staff; on occasions the Director of Postgraduate Research or the Head of Department may be present. The interview should be carried out in English.

Normally, interviews are carried out face-to-face. If it is not feasible for the candidate to meet with the potential supervisor – for instance if they are an overseas applicant – candidates may be interviewed by phone or via Teams/Zoom. Due to Covid-19, all interviews are currently being held remotely.

You are requested to prepare an appox 20-minute (maximum) PowerPoint presentation that should include the following items.

- Highlights of your CV: Academic performance, skills, achievements, etc.

- Description of your undergraduate project.

- Description of your MSc project or equivalent.

- Description of any advanced project (for candidates with industrial experience).

- Highlight skills of particular relevance to your PhD topic.

Funding your PhD

The College has a number of scholarships available for you to apply for. We would recommend you look at the available scholarships to help you find all available sources of funding.

The application form will request information on how you plan to fund your PhD, and this will be considered in appraising the strength of your application. Applications to the College's President's Scholarship Scheme are made in the PhD application form.

It is important to consider the deadline dates of scholarship schemes when applying for to the PhD programme. Scholarship applications can take some time, and it is therefore best to apply in good time in order to secure funding.

IJDesign Vol 2, No 3 (2008)

Table of Contents

Why Do We Need Do...

Reading tools.

- Review policy

- About the author

- How to cite item

- Indexing metadata

- Email the author*

Navigation Menu

Introduction

New Paradigms for Design Practice

What Does the Field Think about Research?

Institutional Thresholds for Doctoral Study

Why Do We Need Doctoral Study in Design?

Meredith Davis

North Carolina State University, North Carolina, USA

This article makes a case for why design research is important to contemporary design practice and the deepening of the design disciplines, especially at this point in our history. It identifies the pressures on knowledge generation exerted by the shift from a mechanical, object-centered paradigm for design practice to one characterized by systems that: evolve and behave organically; transfer control from designers to users or participants; emphasize the importance of community; acknowledge media convergence; and require work by interdisciplinary teams to address the complexity of contemporary problems.

Further, the text addresses the rather checkered past of design research programs in universities in the United States of America (USA), and the international positions by professional design associations on the development of research cultures. Included in this discussion is data on what American design professionals, faculty, and students think about design research and what this data tells us about growing research activity.

Finally, the article talks about the pre-requisite, institutional conditions for establishing and differentiating research-oriented master’s and doctoral degrees. These threshold criteria include: 1) institutional research infrastructure; 2) faculty qualifications to provide curricular leadership in research education; 3) library resources; 4) resources under nascent design research funding models; 5) balance between disciplinary research programs and interdisciplinary challenges; 6) assessment of faculty and student research activity; and 7) research publication and presentation imperatives.

Keywords ─ Doctoral Education, PhD in Design, Design Research, Research Education, Design Knowledge, Design Education.

Relevance to Design Practice ─ There is a general lag by college-level programs in responding to major paradigm shifts in the profession; this article attempts to define the role of advanced programs and research in addressing those shifts in ways not possible under traditional models of professional education.

Citation: Davis, M. (2008). Why do we need doctoral study in design? International Journal of Design, 2 (3), 71-79.

Received October 15, 2008; Accepted December 7, 2008; Published December 31, 2008

Copyright: © 2008 Davis. Copyright for this article is retained by the author, with first publication rights granted to the International Journal of Design. All journal content, except where otherwise noted, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License. By virtue of their appearance in this open access journal, articles are free to use, with proper attribution, in educational and other non-commercial settings.

Corresponding Author: [email protected]

Meredith Davis is Director of Graduate Programs in Graphic Design and Head of the interdisciplinary PhD in Design at North Carolina State University, where she teaches on the issues of design and cognition. She is a medalist and fellow of the AIGA, former president of the American Center for Design, former member of the accreditation commission of the National Association of Schools of Art and Design, and grant reviewer for the National Endowment for the Arts, US Department of Education, National Science Foundation, and Institute for Museum Services. Her book, Design as a Catalyst for Learning, was awarded the 1999 CHOICE award from the Association of College and Research Libraries and she is currently under contract for a textbook series on design with Thames and Hudson Ltd./UK. Meredith is a member of the AIGA Visionary Design Council, NASAD working group on the future of design education, and Cumulus working group on benchmarking doctoral programs.

Many of the interviews and presentations I do today address the question: why do we need doctoral study in design? This question most often comes from practitioners and faculty in a field that has only a short history of research and a long tradition of training in know-how, in the craft of solving problems with the information immediately at hand. It is a reasonable question to ask about a field that is not well understood by the public or by popular media that view design mostly in terms of how things look. But ironically, the greatest skepticism about expanding design research programs seems to reside within the discipline itself, where there is ongoing debate about what constitutes design knowledge.

By contrast, the notion of a design research culture does not seem odd to people in fields outside design, where among the defining characteristics of professions, as opposed to trades, are segments of practice in which the sole activity is the generation of new knowledge. There is broad recognition that knowledge generation sustains the evolution of a discipline and particular interest in the value of design research in cross-disciplinary investigations.

In this commentary, therefore, I first make a case for why design research is important to contemporary design practice and the deepening of the design disciplines, especially at this point in our history. Further, I address the trajectory of design research programs in universities and talk about the pre-requisite conditions for establishing research degrees.

This paper is from the perspective of design in the United States of America (USA), where design research has been especially slow to develop. Discussions of these issues pervade the field worldwide, however, and several working groups have been established to debate these very topics for publication in the coming year.

The modern practice of design has been the model for design education since the days of the Bauhaus. Defined as an object-centered process, the traditional goal of design has been to produce an artifact or environment that solves a problem. For academic programs arising from the arts, the beauty and humanity of such objects or environments are important. For programs arising from the sciences and engineering, usability and efficiency are paramount. And in between are the social sciences, where the issues of culture and social interaction reside.

The distinctions within each of these disciplines are not simplistic, but the research paradigms they represent for producing objects and environments clearly have different value systems and methods, and historically, they have argued for very different curricular paths at the graduate level.

The demands on design practice in the twenty-first century, however, are significantly different from those of the past, suggesting that these paradigms may require re-examination. A number of current trends challenge the traditional notions of what we do and, more importantly what we need to know:

Increasing complexity in the nature of design problems:

Christopher Jones (1970) articulates the scale of design problems which exist in a post-industrial society. He described a hierarchy of design problems, beginning with components and products and extending to systems of interrelated products and communities composed of interacting systems. Jones asserted that the problems of contemporary society are defined at the level of systems and communities; that design action must address an intricate web of connections among people, activities, objects, and settings. He admonished the design professions arguing that our conventional methods for addressing problems are woefully inadequate at these levels of complexity and better suited to work on components and products.

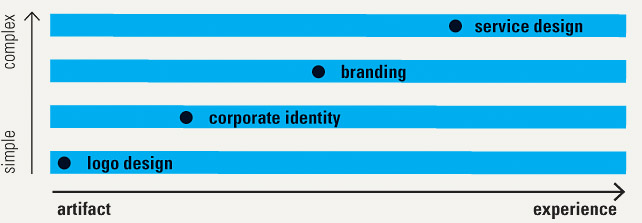

The chart in Figure 1 shows various problem types, ranging from simple to complex and from artifacts to experiences. The evolution of design practice evidences increasing complexity and greater focus on experience and behavior. We now understand that logos do not mean much if they are not nested within a branding strategy and that software systems succeed or fail on how well suited they are to the broader role of technology and the networked economy in people’s lives. This does not mean that work at the experience end of the continuum is devoid of artifacts only that its goal is to engage or mediate some kind of human interaction with a larger context.

Figure 1. The shift from designing artifacts to designing the conditions for experience.

As an explanation of this trajectory I compare two presentations of a design problem with respect to their complexity and experience. These presentations were made by graphic designer Milton Glaser and technologist Nicholas Negroponte. These presenters shared the stage at a conference of the American Institute of Graphic Arts (2005). First, Glaser unveiled a poster for ONE.org, showing a human hand, with each finger in a different skin tone, and the phrase “We are all African.” ONE.org is a website that encourages people to lobby politicians on the problems of poverty. Second, Negroponte showed MIT’s $100 laptop ( http://laptop.media.mit.edu/laptop/ ), designed to bring the educational opportunities of the Internet to children in developing countries. Both objects addressed the issues of poverty, but Glaser’s poster reduced an enormously complex, systems-level problem to a phrase and an emotional image distributed on the streets of New York City. Negroponte’s solution, on the other hand, addressed the complexity of poverty as something to be managed – not simplified – through tools and systems.

More recently, in an article for Interactions , design strategist Hugh Dubberly (2008) made a similar argument saying that traditional notions of design thinking and the innovation process are object-centered and organize our work according to mechanical principles. He described an organic, systems-based alternative that seeks to address friction in the relationships among communities, conventions, and contexts. The results of Dubberly’s process are insight and opportunities for change that create value and that may take the form of experiences, extendable platforms, or evolving systems. Unlike the final state of an object-centered process, which seeks to be “almost perfect”, the results of a systems-based approach are “good enough for now,” acknowledging that conditions will continue to evolve (Dubberly, 2008).

This paradigm shift in the focus of the design process from objects to experiences demands new knowledge and methods to inform decision-making. It broadens the scope of investigation beyond people’s immediate interactions with artifacts and includes the influence of design within larger and more complex social, cultural, physical, economic, and technological systems.

The transfer of control from designers to participants:

Computer scientist Gerhard Fischer (2002) writes that as the influence of technology expands, control moves from the designer to the people for whom we design. Design researcher Liz Sanders (2006) argues that designers need to think less about consumers and users, and more about participants and co-creators ; about designing with people rather than for them. MIT comparative media professor Henry Jenkins (2006) discusses the consequences of media convergence on people’s sense of agency or control of outcomes. Spend a little time on facebook, SecondLife, or ebay and you understand who is in charge.

Design is in uncharted territory with respect to emergent systems and many of the current strategies for studying people are neither predictive of, nor responsive to, a rapidly changing environment of new technology and the resulting relationships among people, places, and things. If we accept the position of activity theorists (Nardi & Kapetlinin, 2006) – that design mediates the relationships between people and the activities they use to influence or interact with their environment – then our research strategies have to go beyond testing actions and operations in human factors labs and asking questions in focus groups that separate people from the settings in which relevant behavior takes place.

The rising importance of community:

Design anthropologist Elizabeth (Dori) Tunstall (2008) talks about the role of community in design: that historical consciousness (people’s understanding of where they come from); life goals (what matters most to members of a community); organizational structure (how collective decisions are made and how individuals fit in); relationships (the means through which people gain understanding of common values and establish trust); and agency (the degree of an individual’s control or influence over things that matter to the community) are important factors in determining the level of communitas. In this sense, we can talk about learning communities and communities of practice that may exist only through online interactions. Further, such perspectives signal that globalization and the complicated issues of designing for and within culture involve more than simply adopting an appropriate visual language.

If design both illustrates the axiology of a culture (i.e. mirrors its highest or most dominant values) and shapes its social interaction (i.e. influences interpretive perspectives and behaviors), then the consequences of design have implications that reach far beyond the immediate consumption of goods, information, and services. And because “community” is no longer defined by geographic location, or even common histories, our understanding of these issues should be re-evaluated through research.

Technological expansion and media convergence:

We now live in a culture of emergent, convergent, sensor, and mobile technology. Traditional object-driven design paradigms, which often result in fixed features and physical attributes, fall short in an experience-oriented world. Networks, tools, platforms, and systems – the means through which people create experience and shape behavior – are the “products” of design efforts in a vastly reconfigured technological world. Design consultant Adam Greenfield (2006) describes ubiquitous computing as “everyware”, “the colonization of everyday life by information technology…a situation…in which information processing dissolves into behavior” (p. 33).

Not only does this shift in the output of design challenge the traditional body of knowledge that informs our design decisions, but it also points to a need for research into the very methods by which we design. If the goal of design is to provide an increasingly invisible interface (which may, for example, be comprised of sensors that are activated only by unconscious gestures), what methods replace a design process that has been all about designing visible representations of mechanical and text-based information systems? And by what criteria do we judge success?

The necessity of interdisciplinary work:

The complex scale of problems, diversity of settings and participants, and demand for adaptable and adaptive technological systems argues for work being done by interdisciplinary teams composed of experts with very different modes of inquiry. How such experts collaborate as peers and the roles design can play in mediating collaboration present new opportunities for designers.

To participate at this level of engagement, therefore, designers must deploy team-based strategies that argue successfully for effectiveness as well as efficiency, sustainability as well as feasibility, and human-centeredness as well as technical viability. Nothing about design education in the past explicitly prepared designers for teamwork; most design professionals do it intuitively. How teams of diverse experts innovate and the role designers play in that innovation, although the subject of many claims in the popular press, is another area about which there is little empirical research.

It is apparent from these challenges that the traditional knowledge base of design has its limits and that for design practice to remain relevant in this rapidly changing environment, the field must generate new knowledge and methods. Because design is subject to modulations in the culture, such knowledge seeking must anticipate where design is going, not focus only on where it has been.

Further, unlike research in other fields, where the first years of doctoral study are spent surveying what has not been done, the question for doctoral students in design is “What is worth doing?” The choices doctoral students and their faculty make in determining dissertation topics have somewhat greater significance in shaping others’ perceptions of design research than do topics in more mature research fields. These topics tell professionals, scholars, and the public what issues truly matter with respect to design and set the stage for the kinds of students who will be attracted to advanced study. When there is so little history of design research to cite, the collection of dissertation topics in graduate programs around the world are indicators of priorities in the field.

In September 2005, Metropolis published a survey of 1051 designers, design faculty, and students in a variety of design disciplines on the issue of research (Manfra, 2005). Admittedly, the survey respondents had varying levels of research understanding and represented only a small portion of the field. But in all of its confusion, this survey still captures some of the challenges facing research professionals.

The first finding was that there is no general consensus about what is meant by the term “research.”

Respondents’ ideas ranged from deep investigations of users to selecting color swatches. This equivocation is exacerbated by the association of research with library information retrieval in most undergraduate design programs; ambiguity regarding the meaning of degree titles around the world; and the politics of tenure and promotion in colleges and universities, especially in the USA.

Few undergraduate design students, especially those in single-discipline colleges of art in the USA, engage in original, disciplined inquiry intended to inform design decisions, nor do most learn how to read and apply research findings from other fields. Starting with first-year foundation courses, undergraduate curricula generally infer that the way to begin work on a design problem is by drawing, that solutions reside in an abstract visual language, and that reading and writing belong primarily to the domains of history and criticism. General education is usually proximate to but not integrated with design study and depends entirely on the resources and general requirements of the institution. Design faculty rarely make explicit use of content and skills acquired from outside the design curriculum, except to “pour it into formats” as the hypothetical subject matter for design projects. There is often little in the faculty’s own educational backgrounds to encourage a deep understanding of how the social sciences can inform an understanding of audience and context.

A small portion of American undergraduate design students eventually enroll in master’s programs, where the dominant educational model – borrowed from the studio arts – addresses the refinement of practice-oriented skills and portfolios. The tiny number of students who make it to doctoral programs, therefore, frequently must start from scratch in developing any operational understanding of what constitutes research. In the USA, Ph.D. programs spend a significant amount of time explaining to prospective applicants, especially those for whom R&D means the next product feature or styling iteration, that curricula do not include studio courses.

Practice-based Ph.D. programs are not common in the USA, where all four of the doctoral programs offering admission to graphic and industrial designers reside in research universities and focus on empirical research. In some cases, professional master’s degree programs in American colleges and universities carve out practice-based research agendas in which demonstration projects take on theoretical or methodological perspectives, but the goal of these programs is not to produce new knowledge. Rather, they speculate on the practice-based consequences of adopting certain theories about design or they illustrate how such viewpoints may be applied in specific contexts. In the USA, the practice-based agenda is generally reflected in professional doctorates (Doctor of Arts, Doctor of Architecture, Doctor of Design, etc.), but there is debate about what these degrees really do to advance practice that is not already achieved under the professional master’s degree or by very accomplished practitioners. Given that tuition in some American schools is nearly $40,000 per year, the actual benefit of these degrees to someone’s career is a topic of discussion.

Further complicating the definition of research is the reward system for design faculty in many American universities. In an effort to establish credibility for art and design programs within academic research settings and to achieve tenure and promotion, college-level faculty have described an array of activities under the term “research.” Freelance design practice, writing for popular design magazines, expressive investigations in the arts, and supervision of student projects with industry frequently appear in faculty vitae as “research” contributions. While these activities may merit tenure and promotion consideration, they usually do not contribute to the body of knowledge in the field, nor are they routinely subjected to the rigorous criteria for scholarship found in the sciences, social sciences, and humanities. Few bring resources to the institution, and when faculty receive funding for proposed projects it is frequently through internal sources, such as professional development grants for new employees. This dilution of the traditional concept of university research stunts American efforts to launch a research culture in design and distracts faculty from the hard work necessary to move a discipline forward. Design faculty, therefore, spend much of their time making the case that they are special rather than integral to the overall research mission of the university.

In some institutions, however, there are more mature research cultures and faculty routinely apply for government and foundation grants. In these cases, tenure, promotion, and merit pay may depend on the submission of proposals and the frequency with which faculty are listed as principal investigators. It is not uncommon for such schools to have dedicated research space and support staff. The challenge in these settings is to integrate research activities with the other academic work of the college; to avoid a bifurcated faculty in which research is viewed as the opposite of creative practice.

Ernest Boyer (1990), the late president of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching and Learning, provided another definition of scholarship in the academy under a 1990 study titled, “Scholarship reconsidered: Priorities of the professoriate” (pp. 16-21). Boyer identified four areas of faculty scholarship: 1) the scholarship of discovery , which is consistent with traditional definitions of research as knowledge generation; 2) the scholarship of integration, which encourages multidisciplinary work that “is serious, disciplined work that seeks to interpret, draw together, and bring new insight to bear on original research” (p. 19); 3) the scholarship of application, which addresses how knowledge can be responsibly applied to consequential problems; and 4) the scholarship of teaching, in which teaching is not seen merely as the execution of instruction, but as an activity involving particular knowledge, reflection, and review as a subject in its own right. Boyer’s classifications imply that faculty may conduct research in any of these areas, but that work in each category is accountable to rigorous standards of quality and peer review within that paradigm.

More recently there have been attempts by professional design associations to benchmark research practices through policy statements. The Australian Institute of Architects, for example, published a research policy in March 2004. Its definition of research describes a “systematic inquiry for new knowledge” and the implementation of “credible and systematic modes of inquiry… [documentation of] findings in a form that is publicly verifiable and open to peer appraisal” (p. 2).

The Design Research Society’s website ( http://www.designresearchsociety.org/ ) states its domain as “ranging from the expressive arts to engineering” and declares one of its three primary interests as “recognizing design as a creative act.” The Asian design research societies, such as the Japanese Society for the Science of Design ( http://wwwsoc.nii.ac.jp/ ) and the Korean Society for Design Science ( http://www.design-science.or.kr/ ), appear to have broad research missions, with some special interest categories strongly encouraging empirical research. Cumulus, an international consortium of approximately 125 schools of art and design, has formed a working group to author guidelines for establishing research programs; the group will distribute a survey this coming year to determine current practices.

While 81% of professionals polled in the Metropolis survey claim to engage regularly in research and 69% of university department chairs say it is a required and integral part of the curriculum, fewer than 70% of professional respondents say they include students in research that is important to their practices (Manfra, 2005).

Consequently, there appears to be no professional infrastructure in the USA for placing students in positions as research assistants in the field, unlike in the sciences, and few links between curricular expectations and the kind of help professionals need in carrying out their research activities. And because there is no unified theory of design, the basis for encouraging a particular research skill set in undergraduate or master’s programs is contested among institutions and across the design disciplines.

There is a history of sponsored projects in American schools, focused primarily in institutions that have high records of graduate placement in practice. While these projects frequently boast a “think tank” approach to a problem posed by business or industry, they often come with patent and copyright entanglements, either from the company or the institution. Such problems often discourage implementation of student ideas in real settings. Therefore, it is unclear what companies actually gain from these projects in a research sense. Most typically, students bring fresh ideas to the invention of form, use of materials, or understanding of process, but it is not apparent whether companies see the benefits of such activity as significant to their businesses, as a recruitment strategy for future employees, or as a philanthropic gesture. The Metropolis study would suggest that, for the most part, student researchers are not considered part of a larger business plan.

It is obvious in many institutions, however, that the primary career goal for doctoral students is framed by the curriculum as teaching at the college level. A 2000 conference at the University of Washington, titled Re-envisioning the Ph.D. , recommended that doctoral students be provided with a wide variety of career options, not just teaching, and that “departments need to take responsibility for student access to [research] internships and provide visits from professionals outside the University who will share their professional career journeys with students” (Nyquist & Wulff, 2000). Apparently, this practice has yet to be adopted widely by doctoral programs in design, despite the presence of design research firms.

When asked which areas of design are among the highest priorities for research, most respondents (80%+) identified sustainability as a top issue (Manfra, 2005).

Yet these same respondents ranked systems theory at the bottom of the list. It is not clear how people can conduct sustainability research without a deep knowledge of systems or how the shift from designing objects to designing systems and tools will flourish if not grounded in such theory.

History and criticism also ranked high in the Metropolis poll, attesting to the growth of scholarship in these areas over the last two decades. Clearly, the history/criticism model is one many designers are accustomed to when thinking of design research and there is organizational infrastructure (e.g. Design Studies Forum) to support faculty and student exchange on these topics. There is, however, no evidence that design practice makes use of such research, so its contribution appears to be mostly at the level of the discipline.

The professional associations in the USA have been silent on the matter of research topics, while generally lending moral support to original investigations but not building conference sessions or publications around specific issues of knowledge generation.

Complicating matters is the absence of a dependable research database to support the design fields.

Existing search engines and library catalogs often fail to recognize design-sensitive terms (i.e. a search under “branding” often yields books on “cattle”) and too few research practitioners are willing to share findings. 22% of practitioners responding to the Metropolis survey said that research outcomes never leave their offices, while 29% present them only at conferences, where proceedings may or may not be available following sessions (Manfra, 2005, p. 132-135). Statistics show that much of the research produced in design offices is considered proprietary, until findings are so old as to no longer be relevant to current practice. And because there are few doctoral programs in design that produce published dissertations, most practitioners appear not to consult universities for original research and relevant literature that may support design practice.

Only 17% of university faculty responding to the Metropolis survey said they publish in books, and many of these may be in the areas of criticism and history, not investigations that inform practice directly. Only 4% disseminate research findings online (Manfra, 2005, p. 132-135).

A project at North Carolina State University took on the task of developing a “proof of concept” for a design research database, recommending that a curated portal to dissertations, conference proceedings, and published literature be established under the American Institute of Graphic Arts in New York City. With the support of AIGA, graduate students advocated standardizing formats for thesis and dissertation abstracts and bibliographies and placing preliminary screening of accessible sources and literature in the hands of institutions and researchers with expertise in particular content areas. The proposed system makes visible the debate over keywords and critical frameworks, acknowledging that an emerging research culture must negotiate both its lexicon and research paradigms. Similar discussions have taken place among members of the Design Research Society.

If these complicated issues could be addressed by the availability of master’s programs, it seems the field would have done so by now. Master’s study in design in many countries has at least a 60-year history, although much of it is configured to serve day-to-day practice, not to build theory and knowledge that can be generalized to many projects.

In the USA, the two-year MFA is the “terminal” degree, granting holders many of the same privileges as the Ph.D. in other fields. Some schools offer the MDes and MS as alternatives, but the one-year MA is designated as an “initial” master’s degree by the accrediting body (National Association of Schools of Art and Design) and does not meet tenure qualifications in many American universities. In some cases, particularly in design history, the MA serves as the bridge to the Ph.D.

Very few American students advance to doctoral study. For students in the areas of graphic and industrial design, there are only four Ph.D. programs in the USA. Doctoral study in architecture and landscape architecture has a longer history, but a doctoral degree is not required to teach in these disciplines in American universities.

There is confusion, therefore, regarding what constitutes research and how someone might prepare to participate in an emerging research culture. Further, despite increasing interest in offering doctoral study, schools have few guidelines about how to go about building advanced programs.

The resources for supporting doctoral education are considerable and the decision to offer doctoral study involves significant commitments, both financial and intellectual. In the USA, the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching (2005) classifies universities as doctorate granting on the basis of the following:

- Level of research activity (i.e. R&D expenditures; research staff; doctoral conferrals)

- Confirmation that the institution awarded at least 20 doctorates in 2003-2004

Under previous Carnegie Foundation categories, the level of federal funding (at least $40 million) and a full range of baccalaureate offerings distinguished research-extensive universities from other kinds of institutions. This definition of research universities guides standards within American institutions for how doctoral programs develop and operate. It also presents particular challenges for design.

Financial support for design programs is limited and a model for research funding in design is nascent.