- Contact Contact icon Contact

- Training Training icon Training

- Portuguese, Brazil

- Chinese, Simplified

Check the spelling in your query or search for a new term.

Site search accepts advanced operators to help refine your query. Learn more.

Congratulations to the 2024 CAS Future Leaders

Announcing the 2024 CAS Future Leaders! This group of exceptional Ph.D. students and postdoctoral scholars from around the world will take the next steps in their leadership journeys this August in Columbus, Ohio, and Denver, Colorado.

2024 CAS Future Leaders

This year's participants were selected from among hundreds of highly qualified applicants, representing a wide array of scientific disciplines and organizations from around the world. Congratulations to our 2024 class:

Aziz Abu-Saleh , University of Windsor, Canada Noah Bartfield , Yale University, United States Michelle Brann , Harvard & Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, United States Rosemary L. Calabro , U.S. Army DEVCOM Armaments Center and United States Military Academy, United States Xiangkun (Elvis) Cao , Massachusetts Institute of Technology, United States Áine Coogan , Trinity College Dublin, Ireland Chiara Deriu , Politecnico di Torino, Italy Madison Elaine Edwards , Texas A&M University, United States Olga Eremina , University of Southern California, United States Inès Forrest , Scripps Research Institute, United States Patrick W. Fritz , University of Fribourg, Switzerland Nabojit Kar , Indiana University Bloomington, United States Stavros Kariofillis , Columbia University, United States Joshua Kofsky , Queen's University, Canada Eric Kohn , University of Wisconsin-Madison, United States Danielle Maxwell , University of Michigan, United States Keita Mori , Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology, Japan Aditya Nandy , University of Chicago, United States Akachukwu Obi , Massachusetts Institute of Technology, United States Ernest Opoku , Auburn University, United States Daisy Pooler , KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Sweden Pragti , Indian Institute of Technology Indore, India Stephanie Schneider , McMaster University, Canada Ekaterina Selivanovitch , Cornell University, United States Hanchen Shen , Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, China Lilian Sophie Szych , Freie Universität Berlin, Germany Alexander Umanzor , University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, United States Ken Aldren Usman , Institute for Frontier Materials, Deakin University - Waurn Ponds, Australia Sara T. R. Velasquez , University of Twente, Netherlands Gayatri Viswanathan , Iowa State University, United States Kunyu Wang , University of Pennsylvania, United States Athi Welsh , University of Cape Town, South Africa Kyra Yap , Stanford University, United States Yirui Zhang , Stanford University, United States Junyi Zhao , Washington University in St. Louis, United States

Join our global network of Ph.D. students and postdoctoral scholars in chemistry and related sciences.

Testimonials, "beyond learning life lessons and skills from top leaders in the chemical industry, participating in future leaders gave me the opportunity to connect with inspiring scientists from all over the world, creating strong friendships with remarkable individuals who continue to be a source of support and motivation long after finishing the program.".

—César A. Urbina-Blanco (2018), C&EN

"For a group of young scientists, strangers to one another, working in such diverse areas of chemical sciences, we connected on a level that no one had ever expected." —Felicia Lim (2018), CAS Blog

"Being part of the Future Leaders transforms your life. You never forget the moment you get that email from CAS. But more importantly, you never forget the people you meet during the program." —Fernando Gomollon Bel (2014), CAS Blog

Why You Should Apply

The CAS Future Leaders program supports the growth of science leadership among early-career scientists. Since 2010, the program has awarded Ph.D. students and postdoctoral scholars opportunities to learn leadership skills, engage in scientific discourse, and connect with peer scientists and innovators from around the world.

Get exclusive leadership training from industry experts and learn how CAS connects the world’s scientific knowledge.

Share your latest discoveries to advance scientific knowledge at the American Chemical Society fall meeting.

Network to make meaningful connections with peer scientists and innovators from around the world.

2024 CAS Future Leaders Benefits

The 2024 CAS Future Leaders Top 100 program recognizes additional outstanding applicants from our call for applications. This new initiative honors their accomplishments and provides exclusive Top 100 benefits to support the growth of their science leadership potential.

2024 CAS Future Leaders Top 100 Benefits

Frequently asked questions, am i eligible to apply .

You must be a current Ph.D. student (or plan to be enrolled in a Ph.D. program in 2024) or postdoctoral scholar in chemistry or related science, with a working knowledge of multiple research information tools.

How do you define “postdoctoral scholar”?

We consider a postdoctoral scholar as an individual who has received a doctoral degree (or equivalent) and is engaged in a temporary period of mentored advanced training to enhance the professional skills and research independence needed to pursue their chosen career path.

Questions about the CAS Future Leaders program? See our FAQ and Terms & Conditions or email the CAS Future Leaders team.

What matters most? Eight CEO priorities for 2024

Analyzing the CEO–CMO relationship and its effect on growth

The Exchange: Making the energy transition real with Tamara Lundgren

Travel Disruptors: Capturing B2B growth

How to prepare for the CEO role

Featured publications.

CEO Excellence

Deliberate Calm

Leadership at Scale: Better Leadership, Better Results

Leading the c-suite.

Building Great CEOs

Author Talks: Indra Nooyi on leadership, life, and crafting a better future

Leading from the heart: How Freshworks’ CEO built a global tech unicorn

What resilience means to Nextdoor CEO Sarah Friar

Moderna’s path to vaccine innovation: A talk with CEO Stéphane Bancel

Welcoming Future Research Leaders to NIH

Posted on June 30th, 2021 by Dr. Francis Collins

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Posted In: Director's Album - Photos

Tags: 2021 Future Research Leaders Conference , diversity , IRP , Marie Bernard , NIH Intramural Research Program , Scientific Workforce Diversity , SWD

One Comment

Congratulations to my American emerging leaders in competitive timeline-driven biomedical research at NIH, USA!

Looking forward to future in-person visits………..

Propeling medical research is the primary scientific goal of meaningfully diminishing the disproportionate share of morbidity/mortality associated with life-threatening diseases in the current Covid-19 global pandemic era.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

@nihdirector on twitter, nih on facebook.

Kendall Morgan, Ph.D.

Comments and Questions

If you have comments or questions not related to the current discussions, please direct them to Ask NIH .

You are encouraged to share your thoughts and ideas. Please review the NIH Comments Policy

- Visitor Information

- Privacy Notice

- Accessibility

- No Fear Act

- HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

- USA.gov – Government Made Easy

Discover more from NIH Director's Blog

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

The Future of Leadership Development

- Mihnea Moldoveanu

- Das Narayandas

Companies spend heavily on executive education but often get a meager return on their investment. That’s because business schools and other traditional educators aren’t adept at teaching the soft skills vital for success today, people don’t always stay with the organizations that have paid for their training, and learners often can’t apply classroom lessons to their jobs. The way forward, say business professors Mihnea Moldoveanu and Das Narayandas, lies in the “personal learning cloud”—the fast-growing array of online courses, interactive platforms, and digital tools from both legacy providers and upstarts. The PLC is transforming leadership development by making it easy and affordable to get personalized, socialized, contextualized, and trackable learning experiences.

Gaps in traditional executive education are creating room for approaches that are more tailored and democratic.

Idea in Brief

The problem.

Traditional approaches to leadership development no longer meet the needs of organizations or individuals.

The Reasons

There are three: (1) Organizations, which pay for leadership development, don’t always benefit as much as individual learners do. (2) Providers aren’t developing the soft skills organizations need. (3) It’s often difficult to apply lessons learned in class to the real world.

The Solution

A growing assortment of online courses, social platforms, and learning tools from both traditional providers and upstarts is helping to close the gaps.

The need for leadership development has never been more urgent. Companies of all sorts realize that to survive in today’s volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous environment, they need leadership skills and organizational capabilities different from those that helped them succeed in the past. There is also a growing recognition that leadership development should not be restricted to the few who are in or close to the C-suite. With the proliferation of collaborative problem-solving platforms and digital “adhocracies” that emphasize individual initiative, employees across the board are increasingly expected to make consequential decisions that align with corporate strategy and culture. It’s important, therefore, that they be equipped with the relevant technical, relational, and communication skills.

Whom do you know, and what can they teach you?

- MM Mihnea Moldoveanu is the Marcel Desautels Professor of Integrative Thinking, a professor of economic analysis, and director of the Desautels Centre for Integrative Thinking and of Rotman Digital at the Rotman School of Management at the University of Toronto.

- DN Das Narayandas is the Edsel Bryant Ford Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School.

Partner Center

- Data, AI, & Machine Learning

- Managing Technology

- Social Responsibility

- Workplace, Teams, & Culture

- AI & Machine Learning

Diversity & Inclusion

- Big ideas Research Projects

- Artificial Intelligence and Business Strategy

- Responsible AI

- Future of the Workforce

- Future of Leadership

- All Research Projects

- AI in Action

- Most Popular

- The Truth Behind the Nursing Crisis

- Work/23: The Big Shift

- Coaching for the Future-Forward Leader

- Measuring Culture

The spring 2024 issue’s special report looks at how to take advantage of market opportunities in the digital space, and provides advice on building culture and friendships at work; maximizing the benefits of LLMs, corporate venture capital initiatives, and innovation contests; and scaling automation and digital health platform.

- Past Issues

- Upcoming Events

- Video Archive

- Me, Myself, and AI

- Three Big Points

Big Idea Future of Leadership in the Digital Economy

In Collaboration With

GUEST EDITOR

Michael schrage.

Research fellow, MIT Sloan Initiative on the Digital Economy

Since 2019, MIT Sloan Management Review and Cognizant have explored the implications digitalization has on leadership. In the recently released 2021 study, “Leadership’s Digital Transformation: Leading Purposefully in an Era of Context Collapse,” the authors expose a component of digital transformation that’s critical but often overlooked by leaders: themselves. The report offers actionable recommendations for leaders to more effectively lead their people and organizations in a time of blurred boundaries, rapidly shifting power dynamics, and general uncertainty.

The Future of Leadership 2021 Report

Leadership’s Digital Transformation

New research suggests that digital workforces expect digital transformation to better reflect and respect their concerns and values, not just boost business capabilities and opportunities. In the current environment, leaders must pay close attention to how their leadership is experienced, and consider whether digital tools, techniques, and technologies are making their companies’ key stakeholders — including employees, consumers, and investors — feel more valued.

Michael Schrage et al.

How Digital Transformation Disrupts Legacy Leaders

Michael Schrage and Benjamin Pring, coauthors of the 2021 research report, “Leaderhip’s Digital Transformation,” are joined by MIT SMR editor Allison Ryder to discuss key takeaways from the study.

The Future of Leadership 2020 Report

The New Leadership Playbook for the Digital Age

The 2020 Future of Leadership Global Executive Study and Research Report finds that leaders may be holding on to behaviors that might have worked once but now stymie the talents of their employees. Organizations must empower leaders to change their ways of working to succeed in a new digital economy.

Douglas A. Ready et al.

Interactive

A page from the new leadership playbook.

Leaders must modify their attitudes and beliefs about what leadership looks and feels like if they want to produce behavior change that lasts over time.

Reimagining What It Takes to Lead

The authors of the 2020 Future of Leadership report “The New Leadership Playbook for the Digital Age” discuss some of the findings from the research.

Insights on the Future of Leadership

Leadership skills, leadership mindsets for the new economy, douglas a. ready, the power of a clear leadership narrative, dodging digital blind spots, collaboration, why great leaders focus on mastering relationships, leading change, leading into the future, the enabling power of trust, leadership lessons from your inner child, closing the gender gap is good for business, douglas a. ready and carol cohen, in praise of the incurably curious leader.

Find your course

- Supporting our Researchers

Aston Future Research Leaders Programme

Aston University is delighted to announce the call for the second cohort of the Future Research Leaders Programme. In defining Research Leadership, we are making the distinction between the research responsibilities that all T&R and R-only colleagues should be routinely engaged with in relation to their own research and those who aspire to:

- set research and impact agendas within and beyond their core discipline,

- lead significant funding applications to develop strategically important research activity

- build collaborations with key academic and non-academic partners

- develop their own leadership and management skills,

- make significant contributions to the research culture at Aston and, more broadly, in the sector,

- lead and mentor others.

The programme consists of two elements; 1-2-1 coaching and group work in the form of Action Learning Sets.

- The coaching will consist of five confidential, one-to-one sessions (90 minutes each) with an experienced leadership coach. Coaching is designed to help participants identify, explore, and attend to the challenges they might encounter as a research leader at Aston. Coaches are there to facilitate thinking but not to give answers. They will create a space where participants can reflect on their roles, ambitions, leadership styles and relationships with other people.

- Action Learning is an approach to solving real problems that involves taking action and reflecting upon the results, therefore, helping to improve the problem-solving process. It requires a group of people (a set) who are supportive of one another to meet periodically to listen, ask questions, take action and provide feedback with the objective of individual and shared personal and professional growth. There will be five sessions, each lasting an hour.

The coaching will be delivered by an external provider with an excellent track record of working with many other UK universities for over a decade. Colleagues from Organisational Development will facilitate the Action Learning Sets.

September 2023: Welcome Lunch and Launch Event (2.5hrs)

Semester One and Two: Coaching Sessions x5 (90 mins)

Semester Three: Action Learning Sets x5 (1hr) The programme involves a significant commitment for participants; it is, therefore, advisable to discuss your application with your line manager before submission.

We are inviting applications from colleagues employed on a T&R or R-only contract who can demonstrate their desire to participate in this programme and how they think they would benefit from this investment in individual coaching. Applications will be accepted from colleagues at Senior Lecturer, Reader or Professorial level (Band 1 and promoted within the last two years only), and independent researchers .

We seek to be transparent, consistent, accountable and inclusive in how we run this selection process and encourage applications from all parts of our community. We recognise that career trajectories and individual profiles will also vary depending on the discipline and the extent to which research is basic/applied. It would not be surprising if an application from a newly promoted Professor in English looks different to that of a Senior Lecturer in Psychology, or an Engineer who is new to academia having moved from a senior role in industry or an applicant who currently holds a prestigious research fellowship. There is not a ‘perfect’ type of application that we are looking for.

We are committed to running an Equality Impact Assessment following the selection of candidates (which is why we will ask you for your staff ID when you apply) in addition, we ask about your ECR status as this is a self-identification and not routinely captured by HR.

I found it extremely helpful to take the time to reflect on my career progression, goals and to find the time to prioritise activities that will allow me to achieve my medium and long term targets. The discussions with the coach were a catalyst to identify strengths and areas of improvement.

2022/23 Participant

It has completely influenced my working in a very positive way. It has made me think about how I prioritise work, about what I want from my work and about the ways that I work (both positive and negative). It has been incredibly valuable for me.

I have really enjoyed the whole programme and we had some great sessions with my coach who walked me through a number of situations and problems and we devised a quantity of tools to deal with various elements of the academic work and related with it expectations and stress.

Key contacts: If you are interested in applying and have any questions, please contact either: Rebecca Stokes, Director of Research Strategy, Funding and Impact Your Associate Dean Research:

- Professor Nicholas O’Regan (BSS)

- Professor Patricia Thornley (EPS)

- Professor Roslyn Bill (HLS)

Your College Impact Lead:

- Dr Ed Turner (BSS)

- Professor Kate Sugden (EPS)

- Professor Afzal - Ur - Rahman Mohammed (HLS)

The deadline for applications is 16:00 (BST) September 1st 2023.

Application Form

Click here to apply to the Research Leadership Programme 2023/24

If you wish to complete an MS Word version of the form, please contact [email protected]

NIH Research Festival

September 13 – 15, 2017

- Future Research Leaders

FAES Terrace

The NIH Future Research Leaders Conference (FRLC), sponsored by the Chief Officer for Scientific Workforce Diversity (COSWD), is an event held in conjunction with the NIH Research Festival to promote knowledge and awareness about scientific career opportunities in the NIH Intramural Research Program (IRP).

The FRLC will provide early-stage investigators from the extramural and intramural community and from diverse backgrounds with an opportunity to:

- Learn about the various scientific opportunities and benefits of establishing a research career within the NIH IRP;

- Meet and interact with NIH investigators and scientific leadership through individualized meetings and scientific presentations;

- Create a network and establish mentoring relationships between FRLC participants and current intramural researchers.

The two and a half day program will include the following activities:

- Information sessions on scientific career opportunities at NIH IRP

- Scientific presentations by FRLC participants (oral & poster presentations)

- One-on-one meetings with NIH scientific leaders and investigators

- Networking sessions

- Opportunities to participate in the NIH Research Festival

- Career development session (e.g., NIH grants process)

- Facilities tours

Please contact [email protected] for any questions about the conference or visit their website .

This page was last updated on Monday, March 15, 2021

- General Schedule of Events

- Plenary Sessions

- Concurrent Symposia Sessions

- Poster Sessions

- FARE Award Ceremony

- Special Exhibits on Resources for Intramural Research

- Technical Sales Association (TSA) Research Festival Exhibit Tent Show

- Research Festival Committees

2017 program

Download the 2017 Research Festival Schedule Overview (6 pages)

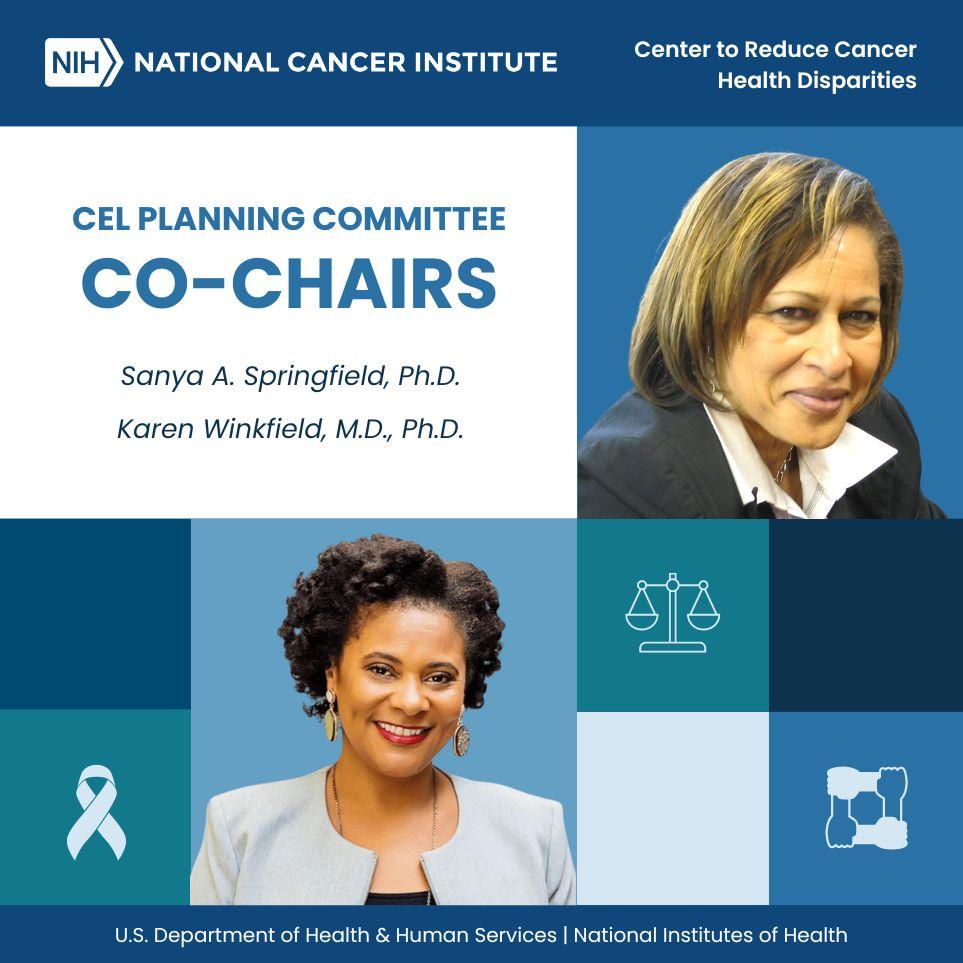

CRCHD Announces the Establishment of Cancer Equity Leaders to Contribute to Health Equity Efforts, Host 2025 Event

April 8, 2024 , by CRCHD Staff

The NCI Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities is thrilled to announce the Cancer Equity Leaders (CEL), a diverse team of premier cancer research leaders who will reimagine and transform the future of cancer health equity. To achieve this aim, the group will work toward three objectives:

- Assess the landscape to elucidate critical strengths and gaps in cancer equity infrastructure.

- Prioritize the critical needs for expanding institutional capacity and achieving cancer health equity.

- Develop a strategic agenda to enhance the National Cancer Plan.

Through this work, the CEL will contribute to our understanding of cancer health equity and help CRCHD determine NCI’s diversity training, biomedical workforce development, and community outreach and engagement initiatives.

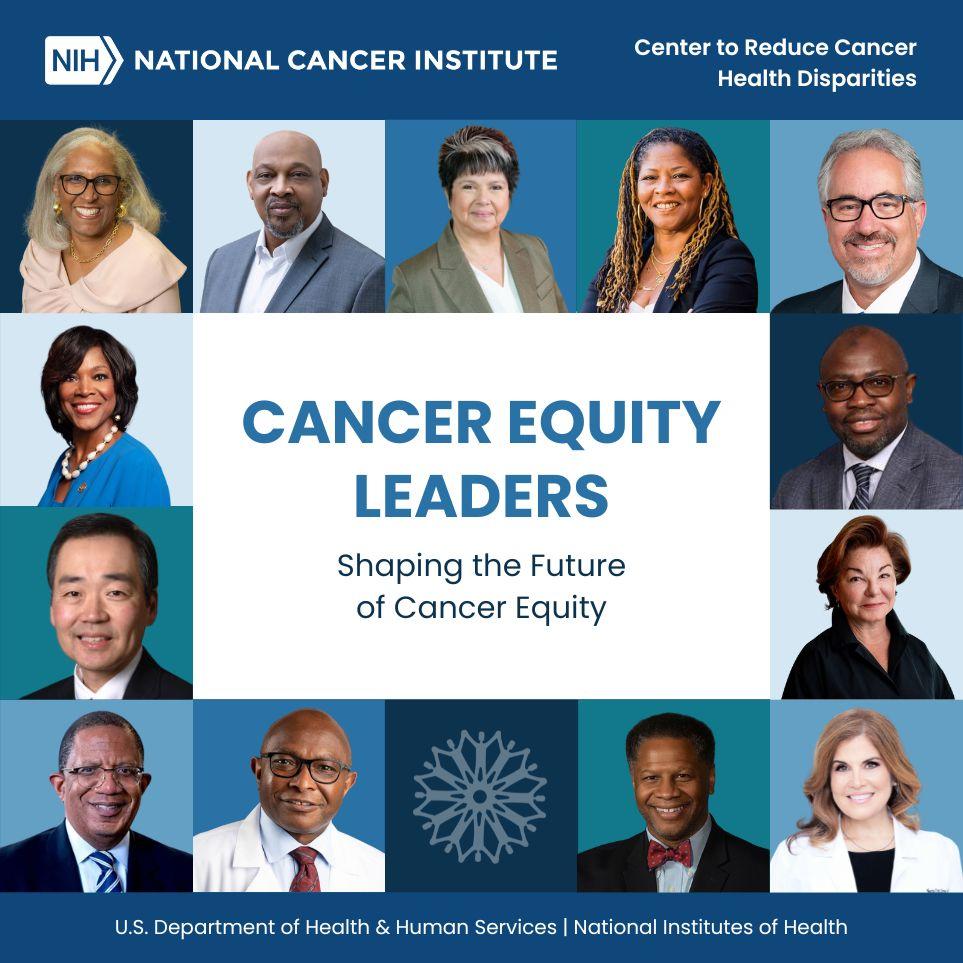

The CEL comprises 13 well-renowned and deeply respected cancer center and medical school leaders, with extensive expertise in the aforementioned areas and exceptional knowledge and understanding of all stages of the cancer continuum. See the full roster of this esteemed group below.

In 2025, the CEL team will host an event to hear and learn diverse perspectives across the cancer community to further advance NCI’s health equity efforts.

This initiative will be co-chaired by NCI CRCHD Director Sanya A. Springfield, Ph.D., and Karen Winkfield, M.D., Ph.D., Executive Director of the Meharry-Vanderbilt Alliance and Associate Director for Community Outreach & Engagement at the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center.

CEL Planning Committee Co-Chairs

Sanya A. Springfield, Ph.D. Director, Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities National Cancer Institute

Karen Winkfield, M.D., Ph.D. Executive Director Meharry-Vanderbilt Alliance Associate Director for Community Outreach & Engagement Ingram Professor of Cancer Research Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center Professor of Radiation Oncology Vanderbilt University School of Medicine Professor of Global Health Meharry Medical College

CEL Members

John Carpten, Ph.D. Director, City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center Director, Beckman Research Institute of City of Hope Chief Scientific Officer Irell & Manella Cancer Center Director’s Distinguished Chair Morgan & Helen Chu Director’s Chair of the Beckman Research Institute City of Hope

Marcia Cruz-Correa, M.D., Ph.D. Professor of Medicine & Biochemistry, University of Puerto Rico Medical Sciences Campus Investigator, UPR Comprehensive Cancer Center

Chanita Hughes-Halbert, Ph.D. Vice Chair for Research and Professor, Department of Population and Public Health Sciences Dr. Arthur and Priscilla Ulene Chair in Women’s Cancer, Keck School of Medicine Associate Director for Cancer Equity, Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center University of Southern California

Juanita Merchant, M.D., Ph.D. Chief of Gastroenterology and Hepatology Regents Professor of Medicine Associate Director for Basic Science, UACC Interim Director, UA Comprehensive Cancer Center University of Arizona, Tucson

Ruben Mesa, M.D. President, Atrium Health Levine Cancer Executive Director, Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist Comprehensive Cancer Center Enterprise Senior Vice President, Atrium Health Vice Dean for Cancer Programs, Wake Forest University School of Medicine The Charles L. Spurr MD Professor of Medicine, Wake Forest University School of Medicine

Valerie Montgomery Rice, M.D. President and Chief Executive Officer Morehouse School of Medicine

Kunle Odunsi, M.D., Ph.D. Director, University of Chicago Medicine Comprehensive Cancer Center Dean for Oncology, Biological Sciences Division The AbbVie Foundation Distinguished Service Professor Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology University of Chicago

Taofeek Owonikoko, M.D., Ph.D. Director, University of Maryland Greenebaum Comprehensive Cancer Center Marlene and Stewart Greenebaum Professor in Oncology, Department of Medicine Executive Director, UMSOM Program in Oncology Senior Associate Dean for Cancer Programs, University of Maryland School of Medicine Associate Vice President for Cancer Programs, University of Maryland, Baltimore

Ben Ho Park, M.D., Ph.D. Director, Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center Benjamin F. Byrd, Jr. Chair in Oncology Professor of Medicine Division of Hematology/Oncology Vanderbilt University Medical Center

Yolanda Sanchez, Ph.D. The Maurice and Marguerite Liberman Distinguished Chair in Cancer Research Professor, Department of Internal Medicine Director & CEO, University of New Mexico Comprehensive Cancer Center

Selwyn Vickers, M.D. President and CEO, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center

Cheryl Willman, M.D. The Stephen and Barbara Slaggie Enterprise Executive Director, Mayo Clinic Cancer Programs Director, Mayo Clinic Comprehensive Cancer Center The David A. Ahlquist, M.D. Professorship in Cancer Research Professor and Consultant Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology Mayo Clinic College of Medicine & Science

Robert Winn, M.D. Director and Lipman Chair in Oncology, VCU Massey Comprehensive Cancer Center Senior Associate Dean for Cancer Innovation and Professor of Pulmonary Disease and Critical Care Medicine VCU School of Medicine

Featured Posts

April 8, 2024, by CRCHD Staff

February 15, 2024, by CRCHD Staff

February 6, 2024, by CRCHD Staff

Unethical Leadership: Review, Synthesis and Directions for Future Research

- Original Paper

- Open access

- Published: 18 March 2022

- Volume 183 , pages 511–550, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Sharfa Hassan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2828-4212 1 ,

- Puneet Kaur 2 , 3 ,

- Michael Muchiri ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6816-8350 4 ,

- Chidiebere Ogbonnaya 5 &

- Amandeep Dhir 3 , 6 , 7

41k Accesses

24 Citations

70 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

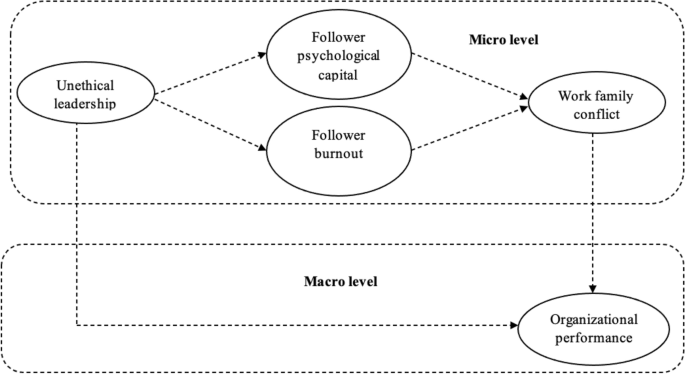

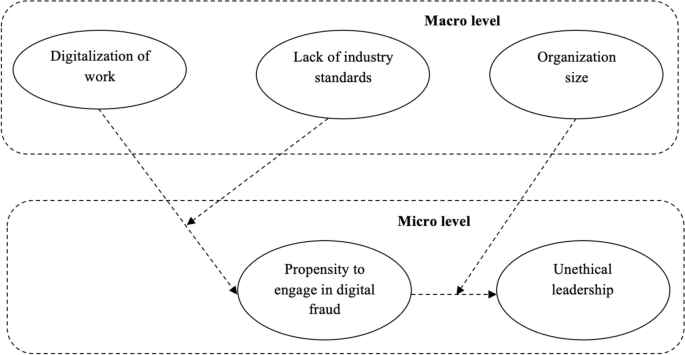

The academic literature on unethical leadership is witnessing an upward trend, perhaps given the magnitude of unethical conduct in organisations, which is manifested in increasing corporate fraud and scandals in the contemporary business landscape. Despite a recent increase, scholarly interest in this area has, by and large, remained scant due to the proliferation of concepts that are often and mistakenly considered interchangeable. Nevertheless, scholarly investigation in this field of inquiry has picked up the pace, which warrants a critical appraisal of the extant research on unethical leadership. To this end, the current study systematically reviews the existing body of work on unethical leadership and offers a robust and multi-level understanding of the academic developments in this field. We organised the studies according to various themes focused on antecedents, outcomes and boundary conditions. In addition, we advance a multi-level conceptualisation of unethical leadership, which incorporates macro, meso and micro perspectives and, thus, provide a nuanced understanding of this phenomenon. The study also explicates critical knowledge gaps in the literature that could broaden the horizon of unethical leadership research. On the basis of these knowledge gaps, we develop potential research models that are well grounded in theory and capture the genesis of unethical leadership under our multi-level framework. Scholars and practitioners will find this study useful in understanding the occurrence, consequences and potential strategies to circumvent the negative effects of unethical leadership.

Similar content being viewed by others

Why Does Unethical Behavior in Organizations Occur?

Developing a framework for ethical leadership.

Alan Lawton & Iliana Páez

The Value of Autoethnography in Leadership Studies, and its Pitfalls

Jan Deckers

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The contemporary business landscape is witnessing staggering levels of unethical conduct that has strikingly surfaced at the bottom-line figures with estimated total losses worth US$42 billion reported by PwC's Global Economic Crime and Fraud Survey ( 2020 ). Interestingly, the contributions of top management in various unethical practices account for over 26% which includes some of the costliest instances of fraud producing not only financial impacts for organisations but also emotional and psychological impacts for their stakeholders (PwC, 2020 ). While sufficient evidence also indicates that top management exhibits serious concerns for business integrity in terms of complying with rules and regulations, behaving responsibly towards various stakeholder groups and maintaining high moral standards (Earnest &Young, 2020 ), the trajectory of corporate scandals continues to increase at a more rapid rate than ever before (Mishra et al., 2021 ), and reciprocal dynamism is witnessed among ‘bad apples’ and ‘bad barrels’(Cialdini et al., 2021 ). Accordingly, corporate leaders, along with the cultures they foster within organisations, work in a vicious cycle wherein one reinforces the other to establish a breeding ground for profound and severe unethical practices. Unsurprisingly, therefore, more than 50% of companies globally experience a minimum of six fraud incidents per year, with another 50% not reporting or investigating the worst incidents (PwC, 2020 ). Hence, unethical leadership is at the intersection of immoral, illegal leadership practices and the unethical climate that further strengthens such leadership. Whether bad apples promote bad barrels or bad barrels host bad apples, the contemporary line of discourse in leadership is increasingly realising the consequential nature of unethical leadership.

Unethical leadership is conceptualised as leader behaviours and decisions that are not only anti-moral but most often illegal and exhibit an outrageous intent to instigate unethical behaviours among followers (Brown & Mitchell, 2010 ). Unethical leadership has long been documented to cause a deleterious impact on organisations. For example, the famous emissions scandal of Volkswagen, known as ‘Dieselgate’, cost the company an estimated US$63 billion (Jung & Sharon, 2019 ). The consequences of this scandal resulted from an interplay of unethical leaders and an unethical organisational culture (Javaid et al., 2020 ). Similar evidence has been reported in another famous case involving Enron, where an unethical climate fostered conscious rule breaking within the organisation, which resulted in both reputational and financial consequences (Sims & Brinkmann, 2003 ). This scenario has been accentuated by the growing reporting of corporate misconduct in the mainstream media (Chen, 2010a ), which has heightened the interest of scholars in this direction.

Research into unethical leadership has largely focused on the aftermath that accompanies organisation leaders’ morally inappropriate and legally unacceptable behaviours that are directed towards the organisation and followers (Javaid et al., 2020 ). Scholars have gauged the impact of unethical leadership in the domains of employee attitudes, e.g. intentions to stay (Ruiz-Palomino et al., 2021 ) and intentions to engage in fraudulent acts (Johnson et al., 2017 ), and employee behaviours, e.g. counterproductive work behaviours (Knoll et al., 2017 ), crimes of obedience (Carsten & Uhl-Bien, 2013 ) and knowledge hiding (Qin et al., 2021 ), among others. Recently, scholars have begun to investigate the team- or group-level ( b ; Cialdini et al., 2021 ; Peng, Schaubroeck, et al., 2019 ) and organisational-level consequences (Mujkic & Klingner, 2019 ; Sherif et al., 2016 ; Vasconcelos, 2015 ) of this phenomenon; however, such investigations remain scant.

An important trend in recent years is the interchangeable use of various measures, conceptualisations and terminologies, which has, by and large, confused the research space on unethical leadership. In fact, concepts such as destructive leadership and its offshoot abusive supervision have dominated this area (Mackey et al., 2021 ), and research pertaining solely to unethical leadership has received extremely limited attention. Given the rampant proliferation of measures and concepts, both the empirical and conceptual distinctiveness of unethical leadership has been blurred (Ünal et al., 2012 ). Furthermore, a dispute over the distinction between unethical and ethical leadership has distorted the conceptual underpinnings of both concepts. Some scholars treat unethical leadership as the flipside of ethical leadership and equate the absence of exemplary leader behaviours with the presence of unethical leadership. However, others have challenged this notion, asserting a quantitative distinction between unethical and ethical leadership styles, which requires separate lines of academic inquiry (Gan et al., 2019 ). Ünal et al. ( 2012 ) captured this view, demonstrating that a single occurrence of dysfunctional leader behaviour does not amount to unethical leadership.

Despite the consequential and distinctive nature of unethical leadership, scholars have made few attempts to systematically organise the literary work in this field and thereby facilitate a comprehensive understanding of unethical leadership from an academic perspective. One of the earliest scholarly investigations in this regard is that of Brown and Mitchell ( 2010 ), who synthesised the academic literature on unethical leadership under the framework of ethical leadership. Their article had an overt focus on ethical leadership within organisations, which they supplemented with unethical perspectives on leadership to broaden the study’s scope. Our review is not only exclusively geared towards unethical leadership but also distinguishes unethical leadership from the absence of ethical behaviours. Furthermore, the early work on unethical leadership does not provide a comprehensive account of the developments in the area, perhaps because this line of literature, as a separate research area, has developed only in the recent past. Thus, we believe that the significant body of research conducted on unethical leadership since Brown and Mitchell’s ( 2010 ) review study needs to be synthesised. Furthermore, Lašáková and Remišová ( 2015 ) enhanced theoretical understanding of unethical leadership by delineating problems in its existing conceptualisations. While their study broadened the concept’s definitional space, it did not account for the extant empirical work in the area. Our study not only distinguishes unethical leadership from related concepts but also provides a detailed view of the empirical work in the area and offers new practical insights into the field.

Apart from the above-discussed rationale, we contend that unethical leadership remains the least researched concept among its academic offshoots. In fact, scholars have thoroughly investigated concepts such as abusive supervision and destructive leadership via both empirical studies and a good number of systematic literature reviews (SLRs) and meta-analyses (Mackey et al., 2017 , 2021 ; Schyns & Schilling, 2013 ; Zhang & Bednall, 2016 ). This points towards the need to examine the extant unethical leadership studies in their own right without confusing them with studies that focus on any of these related concepts. Furthermore, existing SLRs are either too specific or too general and, thus, provide few insights into the area of unethical leadership. For example, studies pertaining exclusively to abusive supervision highlight the verbal and non-verbal abuse leaders direct towards their followers, but these studies offer only a limited understanding of other unethical behaviours, e.g. violations of rules or norms. In the same manner, studies pertaining to destructive leadership examine myriad behaviours that further add to the problematic proliferation of concepts in this research domain (Mackey et al., 2021 ).This underscores an urgent need to re-examine the concept of unethical leadership and the associated literature and thereby facilitate a robust understanding of unethical leadership as a distinct concept.

The current study’s overarching aim is, thus, to conduct an SLR of the extant literature and thereby not only help to synthesise this literature but also identify new issues and broaden the horizon of research in that area by highlighting important knowledge gaps in the existing body of work. Consistent with the above discussion, the present study seeks to address the following research questions (RQs): RQ1 What is the research profile of the relevant extant literature published on unethical leadership? RQ2 What are the dominant focus areas and themes on which most of the academic inquiry has concentrated? RQ3 What are the important knowledge gaps in the existing body of research and potential future research areas that must be investigated to enrich the field?

To address the above research queries, we first extracted the most relevant data with the aid of a robust SLR protocol that has already been validated in a number of studies (Kaur et al., 2021 ; Khan et al., 2021 ; Seth et al., 2020 ; Talwar et al., 2020 ). For RQ1 , we generated the descriptive statistics for the existing research by establishing precise inclusion and exclusion criteria and listing the keywords to search in the most reliable databases. To address RQ2 , we organised all of the shortlisted studies around themes derived from the results of our content analysis. For RQ3 , we identified research gaps and corresponding research questions specific to each emergent theme. To further complement the identified gaps, we developed a multi-level framework of unethical leadership—titled the ‘M3 framework’. Furthermore, we proposed seven potential research models for scholars and practitioners interested in studying unethical leadership. The proposed framework and potential models will be useful for delineating the specific variable relationships scholars can examine in greater detail and from various theoretical lenses to facilitate both conceptual and empirical work in this area. Therefore, these models aim to capture some of the lacunae in the literature.

This SLR is organised into the following sections. In Sect. 2, we examine the conceptual understanding of unethical leadership and make some important distinctions between unethical leadership and other concepts. Section 3, which is devoted to the methodology, explicates the exact protocol we followed to identify the relevant corpus of studies. In this section, we discuss both the data extraction process and the research profile of the sampled studies. In Sect. 4, we discuss the themes that emerged in the coding process as well as the knowledge gaps and potential research questions pertaining to each theme. In Sect. 5, we propose and discuss the conceptual framework and seven potential research models based on gaps identified in Sect. 4. Section 6 provides the practical and theoretical implications of the current study, while Sect. 7 concludes the study by acknowledging its limitations.

Conceptualising Unethical Leadership

Defining unethical leadership.

Contemporary discourse on unethical leadership remains relatively sparse, with only a few studies extensively focused on crystallising the conceptual underpinnings of this leadership type. Brown and Mitchell ( 2010 ) laid the early foundations by offering definitional and conceptual reflections on the phenomenon. They defined unethical leadership ‘ as behaviours conducted and decisions made by organisational leaders that are illegal and/or violate moral standards and those that impose processes and structures that promote unethical conduct by followers ’ (Brown & Mitchell, 2010 , p. 588). The essential tenet of this definition pertains to the leader behaviours that instil unethical conduct in followers. Under this definition, therefore, unethical leadership amounts not only to leaders themselves engaging in unethical behaviours but also enabling and harnessing unethical follower behaviours. Leaders perform these efforts either by overtly demonstrating unethical conduct or passively promoting an unethical climate by ignoring unethical conduct and, thus, allowing unethical behaviours to flourish within organisations (Brown et al., 2005 ).The potential drawback of this definition, however, is its failure to explicitly identify the exact behaviours that could be labelled as unethical. Because morality is a diverse and culturally ingrained phenomenon, the manifestations of unethical behaviours are likewise diverse, which renders unethical leadership a rather relative concept (Resick et al., 2011 ).

To address some of these pitfalls, Ünal et al., ( 2012 ) conducted a seminal study to develop a more robust and comprehensive understanding of unethical leadership. They discussed unethical leadership from normative perspectives and advanced a deeper understanding of the concept by differentiating it from similar leadership styles as well as from the lack of exemplary ethical leader behaviours. Specifically, they defined unethical leadership/supervision as ‘ supervisory behaviours that violate normative standards ’(Ünal et al., 2012 , p.6). Their distinction between unethical leadership and other related concepts, along with the description of precise unethical leadership practices, offers nuanced insights into this research area. In particular, they utilised virtue ethics, deontology, teleology and utilitarian perspectives to develop normative foundations of unethical leadership practices. They identified the violation of employee rights, unfair justice mechanisms, violation of legitimate organisational interests and weak leader character as potential manifestations of unethical leadership. Subsequent research has captured these manifestations of unethical leader behaviour in various cultural contexts. For example, Eisenbeiß and Brodbeck ( 2014 ) examined cross-cultural and cross-sectoral similarities in unethical leadership perceptions. Their comparative research highlighted the interplay of compliance-oriented and value-oriented perspectives within the domain of unethical leadership, and they identified dishonesty, unfair treatment, irresponsible behaviour, non-adherence to rules, laws and regulations, engagement in corruption and other criminal behaviours, an egocentric orientation, manipulative tendencies and a lack of empathy towards followers as the common manifestations of unethical behaviour in various countries.

The above discussion highlights the efforts made, thus, far to clarify what unethical leadership is and what it is not and to define it as a distinct concept rather than merely the opposite of ethical leadership (Ünal et al., 2012 ). With research on unethical leadership taking a new direction and scholars investigating distinct yet related concepts more frequently than unethical leadership itself, however, it becomes crucial to highlight unethical leadership as a separate line of inquiry that requires equal attention. In the sections that follow, we discuss some of these concepts and reveal the differences between them and the concept of unethical leadership.

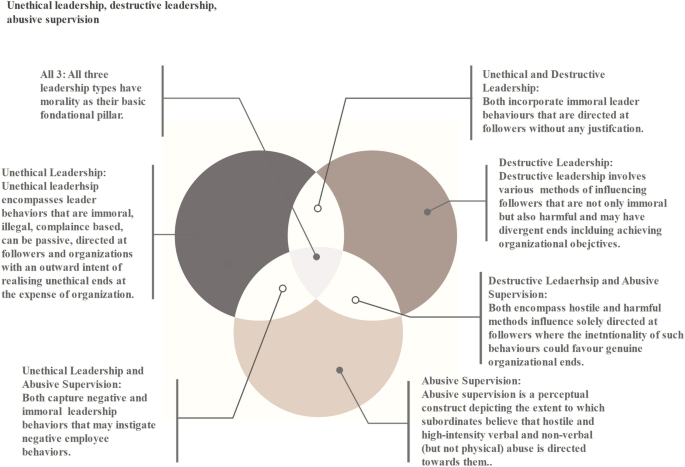

Unethical Leadership and Related Concepts

The domain of unethical leadership has witnessed an increasing proliferation of concepts, which has seriously obstructed the meaningful application of findings to unethical leadership research and practice (Tepper & Henle, 2011 ; Ünal et al., 2012 ). For example, scholars have employed concepts including petty tyranny (Ashforth, 1997 ), supervisor undermining (Duffy et al., 2002 ), workplace aggression (Neuman & Baron, 1998 ), despotic leadership (De Hoogh & Den Hartog, 2008 ), abusive supervision (Tepper, 2000 ), destructive leadership (Einarsen et al., 2007 ) and some newer forms, e.g. Machiavellian leadership (Belschak et al., 2018 ), interchangeably. In fact, concepts such as abusive supervision and destructive leadership have received the most scholarly attention and have developed into separate lines of academic inquiry. It is important to mention here that destructive leadership and abusive supervision have been highly influential in the academic literature (Mackey et al., 2021 ), and the remainder of the concepts mentioned above fall under the domain of these two leadership types. Hence, we discuss these two concepts and attempt to differentiate them from unethical leadership. Furthermore, we advance the conceptual distinction between unethical leadership and the absence of ethical leadership/the lack of exemplary ethical behaviours. Figure 1 presents a conceptual overview of the differences between unethical leadership and other forms of leadership styles. Before discussing these, we provide a brief conceptual understanding of unethical leadership and the lack of ethical behaviours.

Overview of conceptual differences between unethical leadership and other forms of leadership styles

Unethical Leadership vs Lack of Ethical Leadership

The dominant discussions on ethical and unethical leadership have recently shifted towards viewing ethical and unethical leadership as distinct concepts that require their own investigation (Gan et al., 2019 ). These concepts are increasingly recognised as quantitatively distinct, with scholars acknowledging that the absence of ethical behaviour does not necessarily amount to unethical leadership (Ünal et al., 2012 ). While ethical leadership is ‘ the demonstration of normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions and interpersonal relationships’ (Brown et al., 2005 , p. 120), unethical leadership, as discussed above, incorporates behaviours and decisions that could be illegal or morally unsound (Brown & Mitchell, 2010 ). This suggests that the mechanism that explains the formation of unethical leadership and its consequences is distinct from that of ethical leadership (Gan et al., 2019 ). Therefore, a single instance of dysfunctional leader behaviour does not always equate to unethical leadership (Ünal et al., 2012 ). This understanding has implications for the concept’s operationalisation because simply reverse coding the scale items would fail to accurately reflect an unethical leader’s behaviour. Hence, the present study incorporates research that has explicitly studied unethical leadership. In mining the literature, we specifically sought studies that were focused on unethical leadership and not those where the major theme was the absence of exemplary leader behaviours or ethical failures.

Unethical Leadership vs Destructive Leadership

Destructive leadership is defined as ‘ a process in which over a longer period of time the activities, experiences and/or relationships of an individual or the members of a group are repeatedly influenced by their supervisor in a way that is perceived as hostile and/or obstructive ’ (Schyns & Schilling, 2013 , p. 141) While an overlap appears to exist between unethical and destructive leadership, a fine line separates these concepts. Destructive leadership essentially captures harmful methods of influence directed at followers (Mackey et al., 2021 ), and it includes myriad leader behaviours, such as punishment, leader incivility, leader undermining, leader atrocities, toxic behaviours etc. We argue that although both concepts share the dimension of immorality, unethical leadership also includes behaviours that can be compliance based (Eisenbeiß & Brodbeck, 2014 ). In other words, unethical leadership can also entail behaviours that are illegal and amount to regulatory violations (Javaid et al., 2020 ). Furthermore, we argue that some types of destructive leader behaviours—e.g. tyrannical and insular leadership—can be pro-organisational. While such leadership types override follower interests, leaders pursue them under the guise of organisational interests (Einarsen et al., 2007 ).

In fact, pseudo-transformational leadership, yet another form of destructive leadership, has the potential to yield positive organisational outcomes (Almeida et al., 2021 ). In contrast, unethical leadership includes behaviours that are undeniably illegal and, at the same time, violate moral standards, thus, granting no benefit of the doubt to the intentionality of the leader’s behaviour. It can, thus, be inferred that destructive leadership and its various types employ ‘harmful methods of follower influence’, where the intentionality of such behaviour is subject to interpretation. While unethical leadership may not employ harmful methods of punishment, oppression or committing atrocities, it may reflect in corporate scandals and financial misreporting, among others. Finally, destructive leadership, which essentially includes behaviours that are hostile and obstructive, can originate from other types of leadership that need not be unethical. Even positive leadership types, e.g. ethical leadership, can instigate hostile behaviours with the presence of a curvilinear relationship between ethical leadership and positive employee outcomes (Stouten et al., 2013 ).

Unethical Leadership vs Abusive Supervision

Another leading concept in this direction is abusive supervision, which scholars have, at times, categorised under destructive leadership. Abusive supervision is defined as ‘subordinates' perceptions of the extent to which supervisors engage in the sustained display of hostile verbal and nonverbal behaviours, excluding physical contact ’ (Tepper, 2000 , p. 178). Under this definition, abusive supervision, like destructive leadership, encompasses longitudinal hostile behaviours, but these are limited solely to verbal and non-verbal abuse (i.e. these behaviours exclude physical abuse; Zhang & Bednall, 2016 ). Once again, however, scholars have not explicated the direction of outcomes in the context of abusive supervision, making it a typical category of destructive leadership (Guo et al., 2020 ).

The target of the intended behaviour is another critical point of distinction not only for delineating the scope but also the research framework of the present study. Under abusive supervision, leaders’ demeaning language and derogatory remarks are directed solely at their followers (Tepper, 2000 ). Under unethical leadership, however, different forms of unethical leader behaviours can target both followers and organisations. This confirms the view that abusive supervision is highly psychological in nature, encompassing high-intensity hostile behaviours that are directed at people (Almeida et al., 2021 ). The preceding discussion, however, suggests that unethical leadership need not be highly intense or hostile. Rather, it can entail passive and more subtle as well as legally unacceptable behaviours. This means that unethical leadership, unlike abusive supervision, can be task-oriented. Therefore, corporate scandals and financial misreporting fall under the concept of unethical leadership, and abusive supervision is, thus, conceptually distinct from unethical leadership. Furthermore, abusive supervision entails micro-level interactions between a leader and his or her immediate followers. In contrast, unethical leadership can operate at many levels and is much broader than these interactions between the leader and his or her followers.

The remaining concepts enumerated above, including petty tyranny, supervisor undermining, workplace aggression, despotic leadership, corrupt leadership, evil leadership and derailed leadership, likewise fall under the framework of destructive leadership with minor differences based on intentionality, types of behaviour, perceived versus actual behaviour, the inclusion of outcomes and the persistence of behaviours (Schyns & Schilling, 2013 ; Ünal et al., 2012 ). For example, workplace aggression is a type of destructive leadership wherein leaders direct hostile physical behaviours—e.g. pushing, hitting etc.—towards their followers (Neuman & Baron, 1998 ). Similarly, individuals who exercise Machiavellian leadership do not exhibit persistent hostile behaviours but rather intermittent and situational hostile behaviours towards followers (Belschak et al., 2018 ). It is important to mention here that although these conceptual differences have been delineated, the operational measurement of these concepts is not mutually exclusive, which often renders them interchangeable (Ünal et al., 2012 ). However, the current study treats them as separate concepts and includes only those studies that have examined unethical leadership in its own right without reference to any of these overlapping concepts.

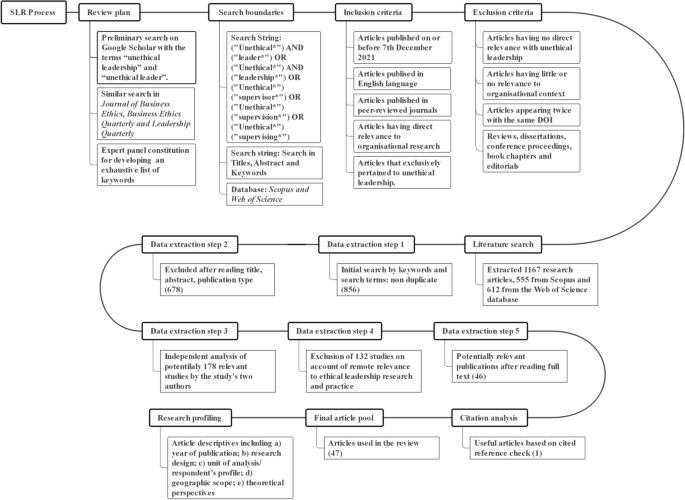

The aim of the present study is to systematically review the extant literature on unethical leadership. Systematic reviews are considered scientific and enable the researcher to identify and critically analyse relevant research in a particular domain. This method of synthesising academic literature has gained acceptance across various disciplines primarily because it enhances research rigour (Dorn et al., 2016 ). In fact, the SLR method has gained wider acceptance in the management literature (Talwar et al., 2020 ) because it provides evidence-informed and reproducible research (Tranfield et al., 2003 ). As we discuss in the following paragraphs, SLRs ensure an audit trail of the decisions taken, which produces transparent, unbiased and objective results with minimum bias (Seth et al., 2020 ).

To ensure objectivity throughout the entire process, researchers follow various steps in systematically synthesising the existing body of research in a particular domain; the resulting objectivity in the process, in turn, expands opportunities for replicating as well as extending the work of the SLR (Seth et al., 2020 ; Talwar et al., 2020 ). Consistent with the procedures previous scholars have followed, we employed a four-step sequential process to systematically review research in the area of unethical leadership. We began by planning the review and ended with a descriptive analysis of the sampled studies. We now discuss these steps in detail (see Fig. 2 ).

An overview of the SLR process

Planning the Review

In this step, which aims to obtain the most relevant and greatest number of results, we ran a preliminary search on Google Scholar with the terms ‘unethical leadership’ and ‘unethical leader’. We analysed the first 100 results from this initial search to update the list of keywords that would eventually be used in developing the final corpus of studies. Then, consistent with best practices, we ran a similar search in the leading journals on ethics, including the Journal of Business Ethics , Business Ethics Quarterly and Leadership Quarterly , to ensure that we did not miss any important studies. Recent work in the domain of business ethics has supported the inclusion of these journals (Newman et al., 2020 ). The results from Google Scholar and reputed journals in business and ethics revealed that, by and large, the literature has employed uniform terminology for unethical leadership with a difference of one or two concepts, e.g. unethical supervision and bad leadership. Therefore, to ensure that we used only the most relevant search terms, we constructed a review panel, which consisted of two senior professors and two senior scholars. The panel was assembled with the intent to provide us with critical feedback and appraisal before we finalised each step in the process. After thorough discussions with the panel members, we added ‘unethical supervision’, ‘unethical supervising’ and ‘unethical supervisor’ to the initial list of keywords. Finally, we searched these terms in Scopus and Web of Science databases because these databases have been frequently used in SLRs due to the exhaustive list of journals they host, particularly in social sciences research (Mongeon & Paul-Hus, 2016 ).

Screening Criteria

We established the following inclusion criteria before constructing the dataset for the present study. First, we only included studies that were peer-reviewed and published in the English language on or before 7 December 2021. Second, we included studies that contained the term unethical leadership in any part of the study, including the title, abstract, keywords or text. Third, we only included studies that had direct relevance to organisational research. Fourth, we only included studies that pertained to unethical leadership. In other words, we discarded studies that used synonyms for unethical leadership that are conceptually different from unethical leadership unless otherwise specified. The exclusion criteria caused us to omit those studies that(a) had no direct relevance to unethical leadership; (b) had little or no relevance to the organisational context—e.g. teacher samples, military samples, sports administration; (c) appeared twice with the same DOI and (d) pertained to reviews, dissertations, conference proceedings, book chapters and editorials.

Data Extraction

We used asterisk (*), 'OR' and 'AND' connectors to develop search strings for use in the databases. We retrieved a total of 1167 research articles, 555 from Scopus and 612 from the Web of Science databases. We removed duplicate items, which reduced the initial corpus to 856. These remaining studies were filtered through the inclusion and exclusion criteria, which resulted in the exclusion of 678 studies. It is important to mention here that studies pertaining to abusive supervision, destructive leadership and authentic supervision were excluded for the reasons mentioned in Sect. 2. The two authors then thoroughly and independently analysed the remaining 178 studies. After a comprehensive evaluation of these studies, we decided that another 132 studies should be removed because they were only remotely relevant to ethical leadership research and practice. For example, initially, we had shortlisted pseudo-transformational leadership (Barling et al., 2008 ) as a type of unethical leadership, but after carefully screening the text, we decided that this type of leadership does not directly pertain to the research domain of unethical leadership. This left us with 46studiesin the main dataset of the present study. Finally, we added one paper manually after conducting forward and backward chaining of the references of the 46 shortlisted papers (see Fig. 2 ). Because two authors were independently involved in this process, we assessed interrater reliability (IRR) using the kappa statistic (Landis & Koch, 1977 ), which significantly exceeded the threshold for agreement between the independent coders.

Research Profiling

A comprehensive overview of the extant literature on unethical leadership is presented in Table 1 .This includes (a) year of publication; (b) research design; (c) unit of analysis/respondent profile; (d) geographic scope and (e) theoretical perspectives. The table reveals that research on unethical leadership has progressed, particularly over the past three years. However, much of the research remains concentrated in developed nations, particularly the USA, which poses serious limitations to the generalizability of the results to emerging nations. Most scholars have employed quantitative techniques, including field surveys, laboratory experiments and field experiments, and various quantitative techniques, including structural equation modelling, logistic regression, hierarchical regression and polynomial regression, to enhance the existing understanding and the generalizability of the results. Interestingly, a good number of scholars have utilised multiple surveys in the same study to comprehensively gauge the proposed effects. For example, scholars have often used experiments and questionnaire-based surveys with different respondents in a single study to enhance the reliability and generalizability of their findings.

No consensus exists regarding the best type of scale for capturing unethical leader behaviours. We observed the use of various scales, with some of the studies simply reverse coding the ethical leadership scale items. For example, Cialdini et al. ( 2021 ) reverse coded the scale item, ‘ Sets an example of how to do things the right way in terms of ethics ’, so that a higher score represented unethical behaviour. The remainder of the studies employed toxic leadership dimensions (Ruiz-Palomino et al., 2021 ) or organisational and interpersonal deviance (Qin et al., 2021 ), or they adapted general unethical organisational behaviours to the leadership context (Fehr et al., 2020 ; Javaid et al., 2020 ).

Moral theory, institutional theory, social cognitive theory and social information processing theory have been the most widely used approaches to understand the phenomenon of unethical leadership in organisational contexts. However, we also observed that scholars have relied less on validation from other theoretical perspectives, e.g. institutional pillars, organisational structure, goal setting and stakeholder theory, among myriad others.

Finally, most of the studies have used organisations, managers, CEOs and employees as the main respondents from whom to collect data—mostly through questionnaires administered via various offline and online modes. While these categories of respondents are common in leadership research, few studies have examined leader–follower dyads.

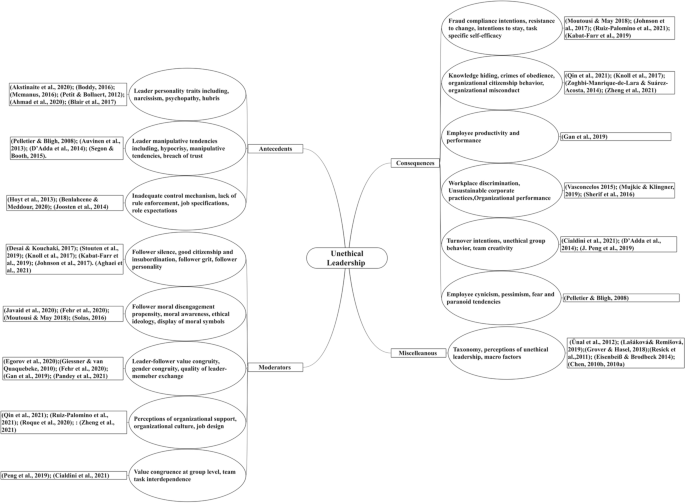

Review of Extant Research on Unethical Leadership

We thoroughly analysed the final sample of included studies with the goal of understanding the antecedents, boundary conditions and consequences of unethical leadership. We employed the content analysis method, a qualitative data analysis technique, to analyse and synthesise the selected studies and thereby develop themes, identify critical knowledge gaps in the existing literature and suggest future research directions. We adopted a three-step protocol employed in recently published studies (Kaur et al., 2021 ; Khan et al., 2021 ; Seth et al., 2020 ), which minimises bias and produces an audit trail of crucial decisions in conducting SLRs. Following Glaser and Strauss ( 1967 ), we developed first-order codes and second-order codes and, finally, segregated the studies into aggregate theoretical dimensions (see Fig. 3 ). In the first step, we utilised open coding to categorise all of the reviewed studies into provisional categories. We then examined the studies to determine their research model and the results of the relationships hypothesised. When this was not possible, we relied on the major findings of the study to curate themes. In the next step—i.e. the axial coding process, we examined the relationships among these categories following deductive and inductive logic to arrive at broader categories. In the final step, we used the selective coding process to identify the final core/aggregate thematic dimensions, which we will discuss in the subsequent sections. In this step, we also invited two academicians with experience in ethics-related topics to review the aggregate themes developed in the prior step. Upon receiving their feedback, we made some minor changes to the themes.

Concept map of extant research on unethical leadership

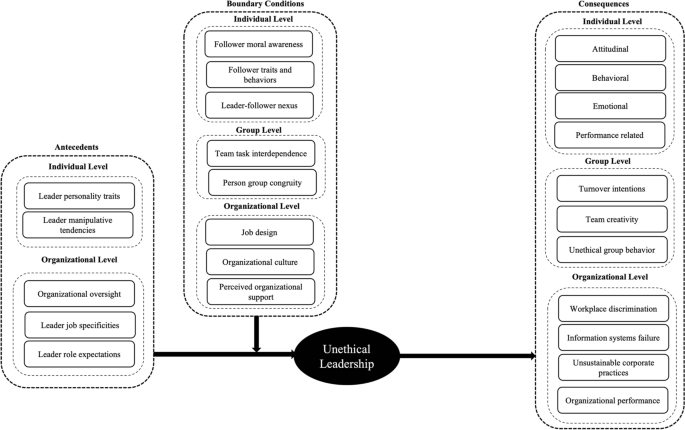

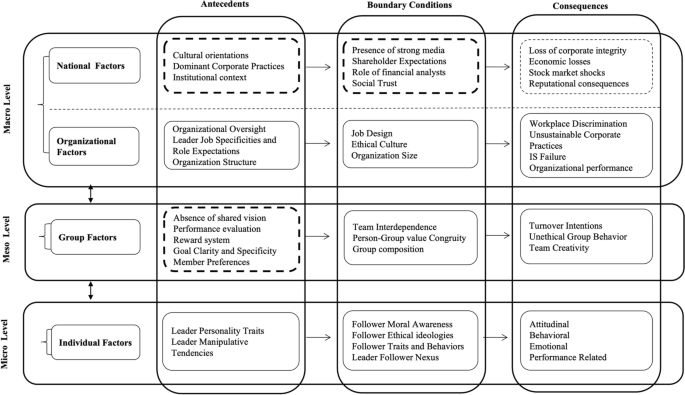

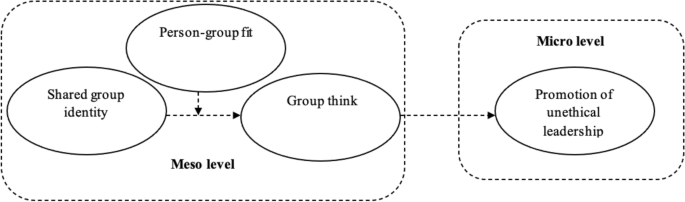

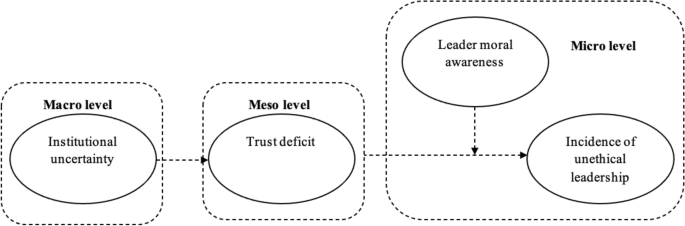

The process resulted in four broad themes: antecedents, consequences, boundary conditions and miscellaneous. The first three themes are discussed at three levels: the individual, group and organisational levels. Figure 4 presents an overview of the three key thematic areas of research examined in the prior extended literature. The major scholarly work has expanded to gauge the impact of unethical leadership, with employee-related outcomes receiving the greatest attention. We also noted that group-level examinations of unethical leadership are quite scant with outright exclusion of group-level antecedents. In the following sections, we discuss these levels and the associated factors in detail and propose important research directions in the area.

An overview of associations among three key thematic areas of research on unethical leadership

Antecedents of Unethical Leadership

We discuss factors that lead to the formation of unethical leadership and identify possible knowledge gaps in this direction.

Individual-Level Antecedents

Leaders’ personality traits.

In seeking to identify individual-level factors that promote unethical leader behaviours, the prior literature has devoted significant attention to leaders’ personality traits. In particular, the literature has cited narcissism, hubris and psychopathological traits as the determinants of unethical leader behaviour. Scholars suggest that a narcissistic leader is likely to possess inflated views about his or her own achievements and capabilities, which create dysfunctional agentic relationships among leaders and followers because leaders promote their own self-interests at the expense of their followers (Campbell et al., 2011 ). Narcissistic leaders indulge in self-aggrandising and derogatory behaviours, which often causes their subordinates to perceive them as unethical in the context of organisations (Hoffman et al., 2013 ). In addition, leaders who are high in narcissism can exhibit moral entitlement, where follower pro-organisational behaviour could lead to the emergence of unethical leadership (Ahmad et al., 2020 ).

Hubris is a similar personality trait that refers to a leader’s exaggerated confidence and prestige in work-related situations. Hubris is often described as a cognitive state in which leaders develop an amplified sense of self-esteem and pride in their abilities; their inflated self-esteem and pride, in turn, makes them think that prevailing norms do not apply to them, which could result in unethical manifestations of this personality trait (Petit & Bollaert, 2012 ). Research has provided similar evidence regarding hubris among CEOs. CEO hubris has a significant influence on the unethical practice of earnings manipulation in organisations (McManus, 2016 ). In fact, hubris is positioned to stimulate leaders towards manipulative language use, which could foster an unethical climate within organisations (Akstinaite et al., 2020 ).

Finally, unethical leadership practices are also associated with psychopaths who are deficient in emotions and conscience and, thus, engage in cold, ruthless and self-seeking behaviours (Marshall et al., 2014 ). Boddy’s ( 2016 ) study supported this, finding that leader psychopathy is associated with unethical practices, including corporate scandals.

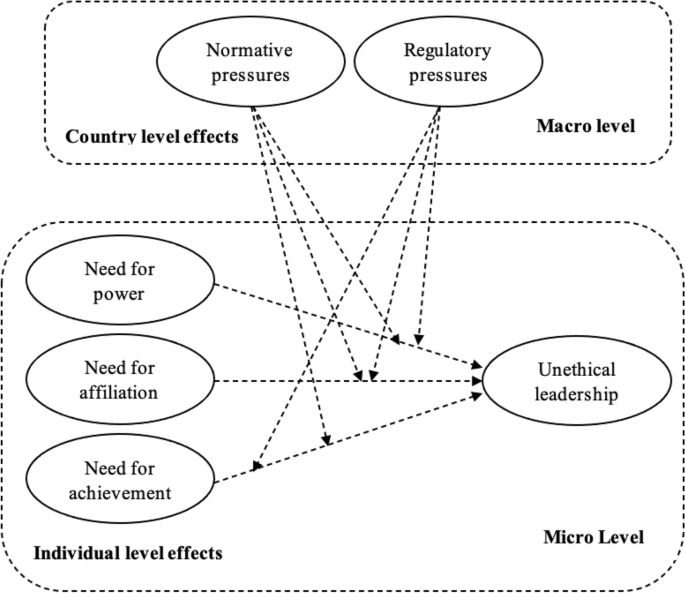

The above discussion signals that the literature, thus, far has examined only dark personality traits, which opens room for other personality frameworks in this direction. The two key research gaps in this regard are as follows. First, many individual factors, needs and behaviours remain unexamined in the literature, thus, far. Second, different personality frameworks have not been validated in the context of unethical leadership. We propose three research questions to address these research gaps. RQ1 How do leaders’ various needs (e.g. achievement, power, affiliation) produce unethical behaviours? RQ2 Do leaders’ personality traits adjust in the work context to stimulate unethical practices? RQ3 Can the cybernetic Big Five model be used to explain unethical leadership?

Leaders ‘Manipulative Tendencies

Leader immorality has long been considered the foundational pillar of unethical leadership practices within organisations (Hartman, 2000 ; Pelletier & Bligh, 2008 ). Unethical leaders are often associated with a lack of integrity and exhibit manipulative behaviours, including hypocrisy and breach of trust (Pelletier & Bligh, 2008 ). Here manipulation refers to the deliberate unethical use of leader competencies and use of manipulative communication directed towards followers in a disguised way (Auvinen et al., 2013 ). Scholars have identified leaders’ prominent statements and communication styles as fostering unethical behaviour within organisations (Akstinaite et al., 2020 ; D’Adda et al., 2014 ). Such manipulative storytelling directed towards followers is considered one possible way to fortify unethical leadership practices within organisations (Auvinen et al., 2013 ). In fact, such manipulation is also manifested in leaders’ use of their emotional competencies to serve their self-interests (Segon & Booth, 2015 ).

While immoral behaviour is the cornerstone of most negative leadership types, including unethical leadership, scholars have investigated most manipulative tendencies in isolation without any regard to leader–follower interactions or person–situation perspectives. To address this gap, we propose the following RQs. RQ1 How can a leader's expression of humour and/or anger interact with his or her moral awareness to produce unethical behaviours? RQ2 What is the relationship of leaders’ implicit personality traits (incremental and entity) and leader–situation fit on the formation of unethical leadership?

Organisational-Level Antecedents

Despite the centrality of organisational factors in the formation of unethical leadership, scholarly attention in this direction is quite scarce. One of the important organisational-level factors with the potential to facilitate unethical behaviour is the lack of organisational oversight mechanisms. When organisations have inadequate control mechanisms, lackadaisical rules enforcement and a lack of transparency, unethical leader behaviours tend to surface (Benlahcene & Meddour, 2020 ). The job specificities and role expectations that are entrusted to a leader can accentuate this effect. For example, under the framework of social role theory, the overarching importance of group goals and the expectations thereof can cause leaders to engage in unethical means to achieve the group’s ends (Hoyt et al., 2013 ). Joosten et al.'s ( 2014 ) study elucidates this effect, suggesting that the depletion of cognitive resources as a result of an excessive workload can cause the emergence of unethical leader behaviours.

Our review of the literature suggests that scholars have yet to explore the full range of organisational factors in the unethical leadership context. To that end, future research can investigate the impact of organisation structure on unethical leader behaviour. In particular, scholars could analyse the impact of new and emerging forms of organisation structures to understand their facilitating and inhibiting impact on unethical leadership. In fact, scholars can employ various theoretical frameworks, including dual-factor theory, to identify the factors that inhibit and facilitate unethical leader behaviours; such endeavours have, thus far, been entirely overlooked. Furthermore, research can explore the potential impact of technology, particularly digital technology, on unethical leadership practices. We propose the following research questions for future scholars. RQ1 Do organic and mechanistic organisational structures differ in their influence on unethical leadership? If so, under what conditions? RQ2 What are the mechanisms that underlie unethical leader behaviours in contemporary organisational structures, e.g. virtual organisations? RQ3 Can the dual-factor theory be used to investigate different sets of facilitators and inhibitors of unethical leadership at the organisational level? RQ4 How might firm digitalisation influence unethical leadership practices at the organisational level?

Consequences of Unethical Leadership

We discuss the impact of unethical leadership at various levels and identify relevant research gaps.

Individual-Level Consequences

Employee work attitudes.

Workplace attitudes are considered the fundamental mechanisms through which employees respond to the prevailing ethical or unethical culture as well as the dominant leadership style in an organisation (Zhao & Li, 2019 ). Such employee perspectives regarding their organisation’s dominant ethical or unethical tone condition their own work-related attitudes, e.g. intentions to leave (Charoensap et al., 2018 ). In addition, these favourable or unfavourable evaluations about the dominant ethical or unethical tone in the organisation, which emanate from social exchange and social learning phenomena, condition followers to exhibit positive and negative work attitudes, respectively (Ruiz-Palomino et al., 2021 ).

In this vein, scholars have not only investigated the impact of unethical leader behaviours on the development of negative work attitudes but also the deleterious impact of such behaviours on positive work attitudes. In fact, scholars are also increasingly interested in whether unethical leadership can foster positive attitudes under certain boundary conditions. For example, Moutousi and May ( 2018 ) suggested that unethical leadership that manifests in organisational change-related initiatives can result in follower attitudinal resistance to such changes, which could benefit the organisation. This study demonstrated follower resistance as a functional organisational outcome that may result whenever unethical means or unethical ends are suspected in change manifestos heralded in the organisation. The work demonstrated that change-related unethical leadership can result in followers’ resistance to change. They found evidence of the impact of unethical leader practices, including the ethicality of change-related goals and the means to achieve them, on followers’ attitudinal resistance to such change initiatives. Furthermore, the study viewed follower resistance as a positive and functional work attitude triggered by prevailing unethical change manifestos heralded in the organisation.

In sharp contrast, unethical leadership also stimulates malfeasance and the development of negative work attitudes. Johnson et al.'s ( 2017 ) study corroborated this, finding that unethical leaders encourage financial statement fraud intentions among employees. Furthermore, unethical leadership has also been found to negatively influence important work attitudes, e.g. lower job satisfaction. Thus, unethical leadership is considered detrimental to employees’ personal growth satisfaction and intentions to stay (Ruiz-Palomino et al., 2021 ). Furthermore, employees’ perceptions of the desirability of remaining with an organisation depend on the extent to which their leaders work to meet the employees’ developmental needs (Ruiz-Palomino et al., 2021 ). Because unethical leadership weakens such employee perceptions, it is logical to assume that it increases their volition to leave.

Similar evidence has been found for the influence of unethical leadership on followers’ task-specific self-efficacy (Kabat-Farr et al., 2019 ). A cognitive phenomenon, self-efficacy refers to the ‘ beliefs in one's capabilities to mobilise the motivation, cognitive resources and courses of action needed to meet given situational demands ’(Wood & Bandura, 1989 ). In the present context, task-specific self-efficacy describes an employee's subjective appraisal of his or her work-related abilities (McGonagle et al., 2015 ). By acting as workplace stressors, unethical leader behaviours negatively influence employees’ beliefs in their own ability to successfully perform their jobs (Kabat-Farr et al., 2019 ).

The prior literature suffers from inconclusive findings regarding the influence of unethical leadership on employee outcomes and the exclusion of important work attitudes. In light of the varying and inconclusive nature of the extant results, future research might consider studying other organisational factors in the context of unethical leadership. We propose two key research questions here. RQ1 How is unethical leadership related to organisational commitment? Does it influence normative, affective and continuance commitment differently? If so, how? RQ2 Does unethical leader behaviour influence work engagement and employee loyalty?

Employee Work Behaviours