Written Thesis Proposal

Introduction

The goal of this article is to help you to streamline your writing process and help convey your ideas in a concise, coherent, and clear way. The purpose of your proposal is to introduce, motivate, and justify the need for your research contributions. You want to communicate to your audience what your research will do ( vision ), why it is needed ( motivation ), how you will do it ( feasibility ).

Return to ToC

Before you start writing your proposal

A thesis proposal is different than most documents you have written. In a journal article, your narrative can be post-constructed based on your final data, whereas in a thesis proposal, you are envisioning a scientific story and anticipating your impact and results. Because of this, it requires a different approach to unravel your narration. Before you begin your actual writing process, it is a good idea to have (a) a perspective of the background and significance of your research, (b) a set of aims that you want to explore, and (c) a plan to approach your aims. However, the formation of your thesis proposal is often a nonlinear process. Going back and forth to revise your ideas and plans is not uncommon. In fact, this is a segue to approaching your very own thesis proposal, although a lot of time it feels quite the opposite.

Refer to “Where do I begin” article when in doubt. If you have a vague or little idea of the purpose and motivation of your work, one way is to remind yourself the aspects of the project that got you excited initially. You could refer to the “Where do I begin?” article to explore other ways of identifying the significance of your project.

Begin with an outline. It might be daunting to think about finishing a complete and coherent thesis proposal. Alternatively, if you choose to start with an outline first, you are going to have a stronger strategic perspective of the structure and content of your thesis proposal. An outline can serve as the skeleton of your proposal, where you can express the vision of your work, goals that you set for yourself to accomplish your thesis, your current status, and your future plan to explore the rest. If you don’t like the idea of an outline, you could remind yourself what strategy worked best for you in the past and adapt it to fit your needs.

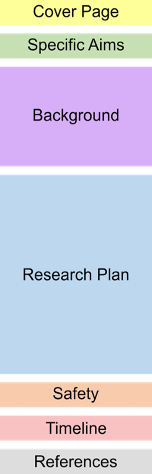

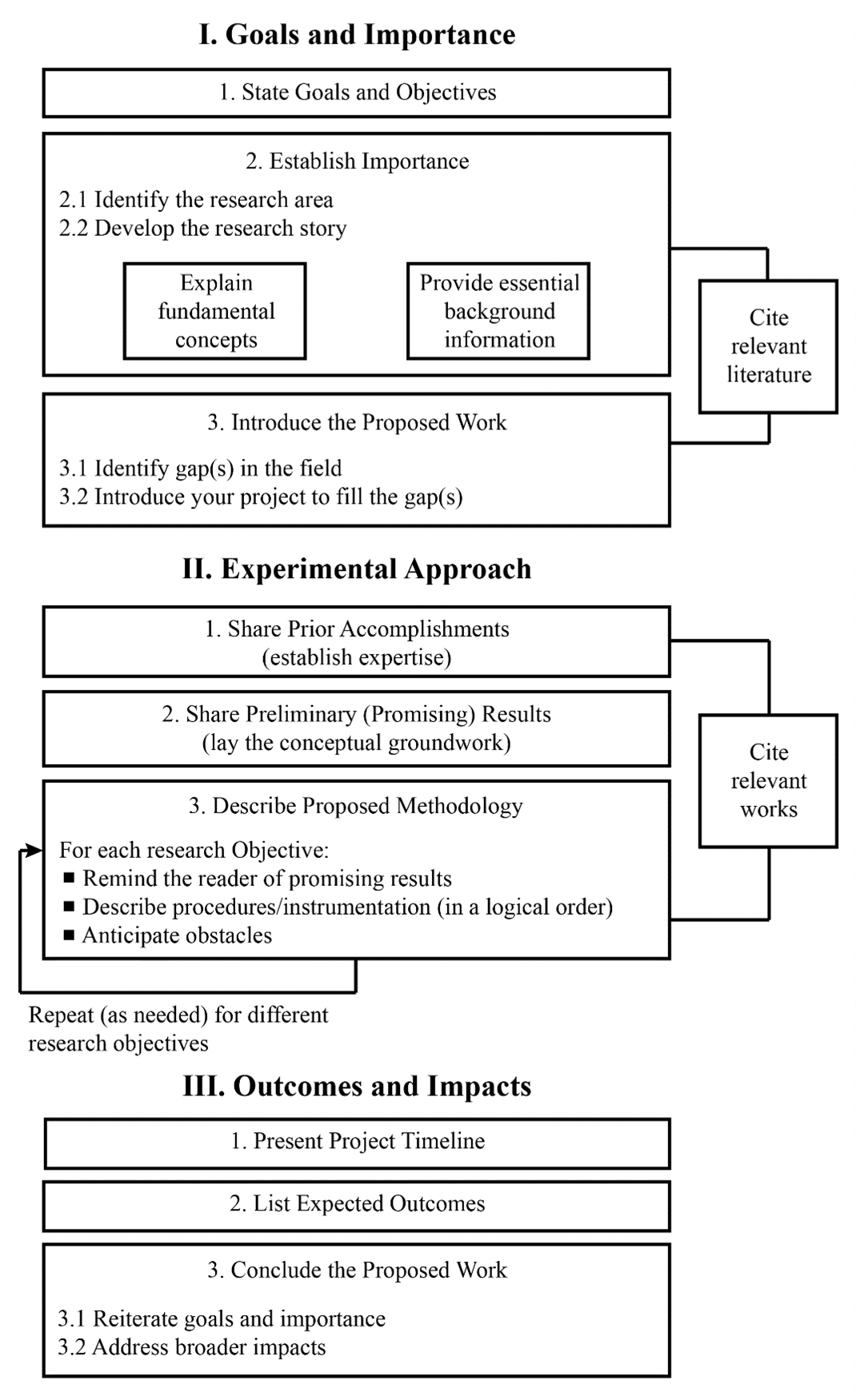

Structure Diagram

Structure your thesis proposal

While some variation is acceptable, don’t stray too far from the following structure (supported by the Graduate Student Handbook). See also the Structure Diagram above.

- Cover Page. The cover page contains any relevant contact information for the committee and your project title. Try to make it look clean and professional.

- Specific Aims . The specific aims are the overview of the problem(s) that you plan to solve. Consider this as your one-minute elevator pitch on your vision for your research. It should succinctly (< 1 page) state your vision (the What), emphasize the purpose of your work (the Why), and provide a high-level summary of your research plans (the How).

- You don’t need to review everything! The point of the background is not to educate your audience, but rather to provide them with the tools needed to understand your proposal. A common pitfall is to explain all the research that you did to understand your topic and to demonstrate that you really know your information. Instead, provide enough evidence to show that you have done your reading. Cut out extraneous information. Be succinct.

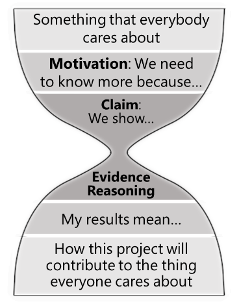

- Start by motivating your project. Your background begins by addressing the motivation for your project. If you are having a hard time brainstorming the beginning of your background, try to organize your thoughts by writing down a list of bullet points about your research visions and the gap between current literature and your vision. They do not need to be in any order as they only serve to your needs. If you are unsure of how to motivate your audience, you can refer to the introductions of the key literatures where your proposal is based on, and see how your proposal fits in or extends their envisioned pictures. Another exercise to consider is to imagine: “What might happen if your work is successful?” This will motivate your audience to understand your intent. Specifically, detailed contributions to help advance your field more manageable to undertake than vague high-level outcomes. For example, “Development of the proposed model will enable high-fidelity simulation of shear-induced crystallization” is a more specific and convincing motivation, compared to, “The field of crystallization modeling must be revolutionized in order to move forward.”

- Break down aims into tractable goals. The goal of your research plan is to explain your plans to approach the problem that you have identified. Here, you are extending your specific aims into a set of actionable plans. You can break down your aims into smaller, more tractable goals whose union can answer the lager scientific question you proposed. These smaller aims, or sub-aims, can appear in the form of individual sub-sections under each of your research aims.

- Reiterate your motivations. While you have already explained the purpose of your work in previous sections, it is still a good practice to reiterate them in the context of each sub-aim that you are proposing. This will inform your audience the motivation of each sub-aim and help them stay engaged.

- Describe a timely, actionable plan. Sometimes you might be tempted to write down every area that needs improvement. It is great to identify them; at the same time, you also need to decide on what set of tasks can you complete timely to make a measurable impact during your PhD. A timely plan now can save a lot of work a few years down the road. Plan some specific reflection points when you’ll revisit the scope of your project and evaluate if changes are needed. Some pre-determined “off-ramps” and “retooling” ideas will be very helpful as well, e.g., “Development of the model will rely on the experimental data of Reynold’s, however, modifications of existing correlations based on the validated data of von Karman can be useful as well.”

- Point your data to your plans. The preliminary data you have, data that others in your lab have collected, or even literature data can serve as initial steps you have taken. Your committee should not judge you based on how much or how perfect your data is. More important is to relate how your data have informed you to decide on your plans. Decide upon what data to include and point them towards your future plans.

- Name your backup plans. Make sure to consider back-up plans if everything doesn’t go as planned, because often it won’t. Try to consider which part of your plans are likely to fail and its consequence on the project trajectory. In addition, think about what alternative plans you can consider to “retune” your project. It is unlikely to predict exactly what hurdles you will encounter; however, thinking about alternatives early on will help you feel much better when you do.

- Safety. Provide a description of any relevant safety concerns with your project and how you will address them. This can include general and project-specific lab safety, PPE, and even workspace ergonomics and staying physical healthy if you are spending long days sitting at a desk or bending your back for a long time at your experimental workbench.

- Create the details of your timeline. The timeline can be broken down in the units of semester. Think about your plans to distribute your time in each sub-aims, and balance your research with classes, TA, and practice school. A common way to construct a timeline is called the Gantt Chart. There are templates that are available online where you can tailor them to fit your needs.

- References. This is a standard section listing references in the appropriate format, such as ACS format. The reference tool management software (e.g., Zotero, Endnote, Mendeley) that you are using should have prebuilt templates to convert any document you are citing to styles like ACS. If you do not already have a software tool, now is a good time to start.

Authentic, annotated, examples (AAEs)

These thesis proposals enabled the authors to successfully pass the qualifying exam during the 2017-2018 academic year.

Resources and Annotated Examples

Thesis proposal example 1, thesis proposal example 2.

Chemistry Department

Research proposal guidelines.

You are using a unsupported browser. It may not display all features of this and other websites.

Please upgrade your browser .

- How we work

Chemistry Research Proposal: A Way to Your Desired Academic Heights

Open the easy way to your PhD in Chemistry with the help of our experts.

Break New Ground on Your PhD Journey With Chemistry Research Proposal

The highest degree in organic chemistry opens up horizons of opportunities for those who have reached the top of a career in science. To climb to a PhD in chemistry degree is almost like the northern slopes of Everest since it requires a certain preparation and the ability to concentrate on achieving an important goal without losing sight of other aspects. However, this work is your entry fee and a decisive part of your PhD application.

Writing a research proposal in chemistry is mandatory on the way to the top of the PhD, which is of paramount importance, being an entry point. In addition, such a proposal in organic chemistry and in any other science-related field is a request document, the basis for the possibility of receiving a grant for any scientific study. This work is a grant application, funding for a project that you consider important and can change the current understanding of science.

Research Proposal in Chemistry: In-Depth Exploration Preparedness

It is essential to be aware that developing a proposal requires specific training in chemistry and to recognize that this work has its own requirements. Its purpose is to showcase your readiness and abilities to conduct profound investigation at an advanced level and your capacity to think in a structured and coherent manner. Your journey to research proposal writing services pages in search of answers on how to approach composing academic work, an essential background for your future PhD degree, is not a coincidence.

To become acquainted with how to write a chemistry research paper, use the template we provided below. However, it’s essential to understand that the goal of academic writing in chemistry isn’t to find a single correct answer, as in an equation. The pivotal aspect here is your ability to precisely define the problematic areas and your skill in identifying effective avenues to their resolution. Your proficiency in clearly and eloquently describing these paths and methods is crucial in successfully preparing a proposal for your PhD.

Structure and Key Stages of Research Proposal for PhD in Chemistry

The structure of a research proposal may differ depending on your institution and specific program requirements. However, every research proposal organic chemistry for a PhD comprises some essential sections that stay the same as they aid in organizing your paper and substantiating its significance.

- Introduction, where you need to define the research areas in chemistry you intend to work with and state a specific study issue to describe in your chemistry proposal. It also includes the main goals of your research and what you plan to achieve.

- The literature review includes a review of existing investigations and literature related to your chemistry topic to demonstrate your comprehension of the subject area and key trends, identify gaps in existing knowledge, and justify the importance of your PhD research.

- Objectives and research questions express the aims of your PhD work clearly and distinctly. Here, you must formulate and describe specific study questions you will address within the scope of the study.

- Methodology to explain the PhD chemistry project methods you plan to use to address the set investigation questions and substantiate your choice of the topic.

- Expected results and research significance is the part where you talk about the results you expect to achieve and how these results can affect organic chemistry science.

- Resources and budget with a clear indication of the necessary resources required for the successful execution of your project. It may involve laboratory equipment, materials, and other tools. Also, here, you need to give a rough estimate of the costs.

- The bibliography lists all the sources you reference in your research proposal in organic chemistry. Keep the list accurate and current.

The essence of this work is to highlight the essentials of your project and reveal its value. As you progress through the project and your questions evolve, the answers will gradually take shape. As a result of your work, you will create a research structure that revolves around the goal, confirming your ability to organize and develop this process competently. In addition, comparable methods and structures find application in biology research proposal writing since the same basic principles underlie scientific investigation covering different areas.

PhD in Organic Chemistry: a Plan, Strategy, Tactics, and Achievements

Approaching the pursuit of a PhD in organic chemistry with a well-crafted strategy and accepted proposal will lead to a clear roadmap in your scientific journey in organic chemistry. This plan will encompass the research itself and the subsequent structure of your dissertation on the given subject. The video we posted here provides practical advice on all the nuances you need to consider when preparing and conducting a scientific study. We recommend watching it.

In order to provide a robust research proposal in chemistry, you need to create it in stages, gradually climbing to each new level, adding part after part. Pay attention to issues such as the method of your future investigations. Make sure to study the existing literature and research methods already conducted on your topic.

Key Aspects of Research Proposal Chemistry Writing

It’s worth noting that any research proposal follows specific stylistic guidelines and features commonly associated with academic institutions and research centers. We can break down the main elements of the writing style within this context into the following key aspects:

- The writing style should maintain a formal and scholarly tone. Employ precise terminology and technical language aligning with the field of organic chemistry.

- State the essence clearly and clearly, avoiding unnecessary words and phrases. In the research proposal chemistry, focusing on conveying the key information is crucial.

- Refrain from utilizing first-person (I) or second-person (you) pronouns. Adopting a third-person perspective (researcher, author, etc.) fosters objectivity and professionalism in your writing. This is to underline the research’s value and avoid personal viewpoints at the same time.

- Adhere to an academic structure with well-defined sections: introduction, literature review, objectives and inquiries, methodology, expected outcomes, and bibliography.

We’re not addressing grammar here, as it should be an inherent feature. Considering the aforementioned stylistic nuances, you’ll be capable of formulating a chemistry research proposal that conforms to the requisites of the scientific community and the educational curriculum. A specified writing style will facilitate clear and precise communication of your academic assignment concepts and their significance.

Best Online PhD Chemistry Help to Keep Your Work-Life Balance

Choosing the right strategy for your PhD journey is the most important decision you can make for yourself. And turning to our online PhD chemistry assistance can be effective in keeping the right course during your study period.

PhDresearchproposal.org is not only just a writing service but a place where you can get qualified support from the best experts in their fields. Due to our advanced assignment process, you have access to top subject-matter writers with proven qualifications and years of experience in making research proposals, leading to achieving the desired results. Contact us now and get the opportunity to maintain a work-life balance, leaving yourself time for your current life and, at the same time, continue your scientific career in organic chemistry.

Upload Files

Thank you for your request!

We will get in touch with you shortly!

Please, try one more time.

Princeton Correspondents on Undergraduate Research

How to Write a Research Proposal as an Undergrad

As I just passed the deadline for my junior independent work (JIW), I wanted to explore strategies that could be helpful in composing a research proposal. In the chemistry department, JIW usually involves lab work and collecting raw data. However, this year, because of the pandemic, there is limited benchwork involved and most of the emphasis has shifted to designing a research proposal that would segue into one’s senior thesis. So far, I have only had one prior experience composing a research proposal, and it was from a virtual summer research program in my department. For this program, I was able to write a proposal on modifying a certain chemical inhibitor that could be used in reducing cancer cell proliferation. Using that experience as a guide, I will outline the steps I followed when I wrote my proposal. (Most of these steps are oriented towards research in the natural sciences, but there are many aspects common to research in other fields).

The first step is usually choosing a topic . This can be assigned to you by the principal investigator for the lab or a research mentor if you have one. For me, it was my research mentor, a graduate student in our lab, who helped me in selecting a field of query for my proposal. When I chose the lab I wanted to be part of for my summer project (with my JIW and senior thesis in mind) , I knew the general area of research I wanted to be involved in. But, usually within a lab, there are many projects that graduate students and post-docs work on within that specific area. Hence, it is important to identify a mentor with specific projects you want to be involved in for your own research. Once you choose a mentor, you can talk to them about formulating a research proposal based on the direction they plan to take their research in and how you can be involved in a similar project. Usually, mentors assign you one to three papers related to your research topic – a review paper that summarizes many research articles and one to two research articles with similar findings and methodology. In my case, the papers involved a review article on the role of the chemical inhibitor I was investigating along with articles on inhibitor design and mechanism of action.

The next step is to perform a literature review to broadly assess previous work in your research topic, using the articles assigned by your mentor. At this stage, for my proposal, I was trying to know as much about my research area from these papers as well as the articles cited in them. Here, it is helpful to use a reference management software such as Zotero and Mendeley to organize your notes along with all the articles you look into for a bibliography.

After going through your literature review, you can start thinking about identifying questions that remain to be answered in that field. For my JIW, I found some good ideas in the discussion section of the papers I had read where authors discussed what could be done in future research projects. One discussion section, for example, suggested ways to complement in-vitro experiments (outside of a living organism) with in-vivo ones (inside a living organism) . Reviewing the discussion section is a relatively straightforward way to formulate your own hypothesis. Alternatively, you could look at the papers’ raw data and find that the authors’ conclusions need to be revisited (this might require a critical review of the paper and the supplementary materials) or you could work on improving the paper’s methodology and optimizing its experiments. Furthermore, you might think about combining ideas from different papers or trying to reconcile differing conclusions reached by them.

The next step is developing a general outline ; deciding on what you want to cover in your proposal and how it is going to be structured. Here, you should try hard to limit the scope of your proposal to what you can realistically do for your senior thesis. As a junior or a senior, you will only be working with your mentor for a limited amount of time. Hence, it is not possible to plan long term experiments that would be appropriate for graduate students or post-docs in the lab. (For my summer project, there was not a follow up experiment involved, so I was able to think about possible experiments without the time or equipment constraints that would need to be considered for a JIW). Thus, your proposal should mostly focus on what you think is feasible given your timeline.

Below are two final considerations. It is important that your research proposal outlines how you plan to collect your own data , analyze it and compare it with other papers in your field. For a research project based on a proposal, you need only establish if your premises/hypotheses are true or false. To do that, you need to formulate questions you can answer by collecting your own data, and this is where experiments come in. My summer project had three specific aims and each one was in the form of a question.

It is important to keep in mind in your proposal the experiments you can perform efficiently on your own – the experimental skills you want to master as an undergraduate. In my view, it is better to learn one to two skills very well than having surface-level knowledge of many. This is because the nature of research has been very specialized in each field that there is limited room for broad investigations. This does not mean your proposal should be solely based on things you can test by yourself (although it might be preferable to put more emphasis there). If your proposal involves experiments beyond what you can learn to do in a year or two, you can think of asking for help from an expert in your lab.

A research proposal at the undergraduate level is an engaging exercise on coming up with your own questions on your chosen field. There is much leeway as an undergraduate to experiment within your field and think out of the box. In many ways, you will learn how to learn and how to formulate questions for any task you encounter in the future. Whether or not you want to be involved in research, it is an experience common to all Princeton students that you take with you after graduation.

In this post, I have described the basic elements of a natural science research proposal and my approach to writing one. Although the steps above are not comprehensive, I am hopeful they offer guidance you can adapt when you write your own proposal in the future.

— Yodahe Gebreegziabher, Natural Sciences Correspondent

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

Your browser is not supported

Sorry but it looks as if your browser is out of date. To get the best experience using our site we recommend that you upgrade or switch browsers.

Find a solution

- Skip to main content

- Skip to navigation

- hot-topics Extras

- Newsletters

- Reading room

Tell us what you think. Take part in our reader survey

Celebrating twenty years

- Back to parent navigation item

- Collections

- Chemistry of the brain

- Water and the environment

- Chemical bonding

- Antimicrobial resistance

- Energy storage and batteries

- AI and automation

- Sustainability

- Research culture

- Nobel prize

- Food science and cookery

- Plastics and polymers

- Periodic table

- Coronavirus

- More navigation items

How to put together a research proposal

By Kit Chapman 2017-04-11T08:04:00+01:00

- No comments

The five points researchers should remember when pitching for funds

You know what you want to investigate. You know how you’re going to do it. Now, all you need is the funds. That means putting together a research proposal – and that can be a daunting prospect. Creating a research proposal is a common part of any young researcher’s career, but there are very few guides on how to construct them, what to include and what to leave out.

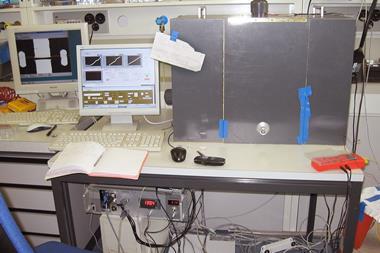

Source: (c) Blend Images / Alamy Stock Photo

While the exact shape of the proposal will depend on your area, at last year’s Joliot Curie Conference at the University of York, young researchers created a series of draft proposals to discuss with their peers. With their permission, three researchers allowed us to give their proposals to two experts: Paul Cullis, professor of organic and biological chemistry at the University of Leicester, UK, and Peter Knowles, professor of theoretical chemistry at Cardiff University, UK.

After each of the three researchers received detailed and personalised feedback, we collected the judges’ comments and condensed them into five pieces of advice any prospective researcher should know before sending in that all-important proposal.

Panels won’t necessarily know your area

It’s easy to assume that the panel will understand the area you’re discussing – but that isn’t always the case, says Cullis. ‘Review panels will have a range of experts in a number of different fields, but the entire panel will need to read and understand the importance of funding the proposal. It has to be convincing for the expert in terms of detail but also have enough background for the non-expert to see the contribution.’

Knowles agrees. ‘Proposals for technical work are likely to be considered by assessors some of whom will not be totally familiar with the area. It’s a good idea to preface the whole thing with a few sentences explaining why, in particular, certain parts of the project are needed. This would also be an opportunity to argue the importance of the project, including its potential use by others.’

Provide a rationale

‘A strong and detailed rationale for the research project is a useful first paragraph, linked nicely to the applicant’s experience and previous work in the second,’ Knowles advises. ‘This would also be an opportunity to argue the importance of the project, including its potential use by others.’

Cullis agrees. ‘Funding agents want to hear: why is this important; what are the major challenges; what is the programme of research; why might this programme move the field forward and what will the impact be? Remember there is a competitive element to gaining funding, so try to avoid underselling yourself.’

Explain your methods

‘It’s always good to give a brief explanation of methods to be used, to demonstrate the proposal has been planned and thought through,’ says Cullis, ‘It is particularly important to demonstrate that you have thought through whether the techniques are sensitive enough, and whether you anticipate any problems such as interference from other things in the sample.

One good way to achieve this, Cullis advises, is to break your proposal down into work packages. ‘Defining a series of work packages is very good practise since it provides a clear structure to the programme of research. The work packages help to define the milestones and outputs and provide evidence that you have thought through and planned the project carefully.’

However, Knowles warns, if you do include work packages make sure they are detailed – generically expressed packages aren’t as convincing to a panel as specific actions.

Show your connections

If you have an important intellectual property (patent), include it, adds Cullis. ‘It might also be good to comment on who might be interested in exploiting the outputs of your research programme… the involvement of industrial partners is another major strength that could be mentioned, since this signals that the project is of potential commercial importance and input from collaborators familiar with the current state of the art enhances the application.’

If your work is multidisciplinary, don’t forget to explain exactly who you’ll be working with any why. ‘A multidisciplinary project would look more convincing if you name the collaborators and spell out the precise nature of the collaboration, in other words what expertise they bring,’ says Cullis. ‘Funding agencies would expect collaborations to be in place prior to agreeing funding.’

Sell yourself

‘Don’t be afraid to sell your research expertise,’ Cullis advises. ‘Obtaining funds is a competitive process. Research panels will want to feel confident that, if awarded the grant, you are the person who can deliver results.’

Knowles agrees that including a section on your track record is important to impressing a panel. ‘It shows distinctive detail, as well as solid evidence of experience and esteem.’

Finally, remember that research proposal is just as important as a CV: so make sure that you take time to make it as presentable as possible. ‘It’s not a good idea to present a document that shows any sign whatsoever of incomplete editing or lack of care,’ warns Knowles. ‘There’s no need for it to be all in bold font, or missing appropriate capitalisation, punctuation or spelling errors.’

- Careers advice

- Research institutions

- Universities

- young chemists

- young scientists

Related articles

Slow progress reforming academia creates its own generation gap

2024-07-02T11:15:00Z

By Emma Pewsey

Closing the generation gap

2024-07-02T08:39:00Z

By Golfam Hoda

From baby boomers to gen Z, how do different generations approach chemistry?

2024-07-02T08:30:00Z

By Rachel Brazil

Leaked exams lead to cancellations that leave Indian students and researchers frustrated

2024-07-01T08:30:00Z

By Sanjay Kumar

Chemistry’s authority on nomenclature Iupac seeks new home

2024-06-28T08:30:00Z

By Kit Chapman

Lab digitalisation and industry 4.0

2024-06-26T08:30:00Z

By Thomas McGlone

No comments yet

Only registered users can comment on this article., more careers.

How to organise your data

2024-06-20T08:34:00Z

By Victoria Atkinson

How to choose a university chemistry course

2024-06-03T08:25:00Z

By Julia Robinson

How Rainbow Lo is accelerating innovation

2024-05-23T09:23:00Z

Diversifying the PhD

2024-05-17T13:35:00Z

A summer placement doesn’t have to be brilliant to be worthwhile

2024-05-10T13:30:00Z

How to find and make the most of a summer placement

2024-05-09T13:23:00Z

- Contributors

- Terms of use

- Accessibility

- Permissions

- This website collects cookies to deliver a better user experience. See how this site uses cookies .

- This website collects cookies to deliver a better user experience. Do not sell my personal data .

- Este site coleta cookies para oferecer uma melhor experiência ao usuário. Veja como este site usa cookies .

Site powered by Webvision Cloud

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

35911 Overview of the Research Proposal

- Published: August 2008

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

In this module, we focus on writing a research proposal, a document written to request financial support for an ongoing or newly conceived research project. Like the journal article (module 1), the proposal is one of the most important and most utilized writing genres in chemistry. Chemists employed in a wide range of disciplines including teaching (high school through university), research and technology, the health professions, and industry all face the challenge of writing proposals to support and sustain their scholarly activities. Before we begin, we remind you that there are many different ways to write a successful proposal”far too many to include in this textbook. Our goal is not to illustrate all the various approaches, but rather to focus on a few basic writing skills that are common to many successful proposals. These basics will get you started, and with practice, you can adapt them to suit your individual needs. After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following: ◾ Describe different types of funding and funding agencies ◾ Explain the purpose of a Request for Proposals (RFP) ◾ Understand the importance of addressing need, intellectual merit, and broader impacts in a research proposal ◾ Identify the major sections of a research proposal ◾ Identify the main sections of the Project Description Toward the end of the chapter, as part of the Writing on Your Own task, you will identify a topic for the research proposal that you will write as you work through this module. Consistent with the read-analyze-write approach to writing used throughout this textbook, this chapter begins with an excerpt from a research proposal for you to read and analyze. Excerpt 11A is taken from a proposal that competed successfully for a graduate fellowship offered by the Division of Analytical Chemistry of the American Chemical Society (ACS). As is true for nearly all successful proposals, the principal investigator (PI) wrote this proposal in response to a set of instructions. We have included the instructions with the excerpt so that you can see for yourself how closely she followed the proposal guidelines.

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| October 2022 | 34 |

| November 2022 | 3 |

| December 2022 | 8 |

| January 2023 | 9 |

| February 2023 | 1 |

| March 2023 | 4 |

| April 2023 | 10 |

| May 2023 | 2 |

| July 2023 | 4 |

| August 2023 | 8 |

| September 2023 | 47 |

| October 2023 | 36 |

| November 2023 | 5 |

| December 2023 | 2 |

| January 2024 | 7 |

| February 2024 | 9 |

| March 2024 | 5 |

| April 2024 | 5 |

| June 2024 | 16 |

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Future Students

- Parents/Families

- Alumni/Friends

- Current Students

- Faculty/Staff

- MyOHIO Student Center

- Visit Athens Campus

- Regional Campuses

- OHIO Online

- Faculty/Staff Directory

College of Arts and Sciences

- Awards & Accomplishments

- Communications

- Mission and Vision

- News and Events

- Teaching, Learning, and Assessment

- A&S Support Team

- Faculty Affairs

- Human Resources

- Promotion & Tenure

- Centers & Institutes

- Faculty Labs

- Undergraduate Research

- Environmental Majors

- Pre-Law Majors

- Pre-Med, Pre-Health Majors

- Find an Internship. Get a Job.

- Honors Programs & Pathways

- Undergraduate Research Opportunities

- Undergraduate Advising & Student Affairs

- Online Degrees & Certificates

- Ph.D. Programs

- Master's Degrees

- Certificates

- Graduate Forms

- Thesis & Dissertation

- Departments

- Alumni Awards

- Giving Opportunities

- Dean's Office

- Department Chairs & Contacts

- Faculty Directory

- Staff Directory

- Undergraduate Advising & Student Affairs Directory

Helpful Links

Navigate OHIO

Connect With Us

Research Proposal Requirements in Chemistry & Biochemistry

Students should discuss with their adviser and committee members the expected scope of the proposal significantly in advance of submitting it for review.

Proposal Summary

- The proposal summary contains a description of the proposed activity suitable for publication. It should NOT be an abstract of the proposal, but rather a self-contained description of the activity that would result from the research.

- The summary should be written in the third person and include a statement of objectives (specific aims and sub-aims) and methods to be employed.

- It should be informative to other persons working in the same or related fields and insofar as possible, understandable to a scientifically or technically literate lay reader.

History and Background

- (minimum 3 pages)

- How did this research area develop?

- What is already known?

Significance

- Why is this research area important?

- What important questions in this research area remain to be answered?

Research Design and Methods (minimum 5-6 pages)

- Describe how your research plan will accomplish the specific aims of the project.

- Describe and critically discuss the experimental techniques that you plan to use in your project.

- Discuss any possible difficulties that may occur and possible solutions.

- Provide a timeline for completion of each specific aim (and sub-aims).

Preliminary Results

(as appropriate)

- Discuss the anticipated outcomes/results and their significance

- Discuss how the proposed project will add to the knowledge base of the discipline.

- References must be sequentially numbered in the text and cited according to standard ACS format with complete titles.

- The bibliography must include at least 30 citations.

Research Proposal | Chemistry and Biochemistry | SIU

SIU Quick Links

- People Finder

- 618-453-5721

- [email protected]

College of Agriculture, Life and Physical Sciences

Requirements, research proposal, research proposal and preliminary oral examination.

The preparation and defense of an original research proposal serves as the second portion of the preliminary examination. For this portion, there exists a Proposal Evaluation Committee (PEC) to consist of the student's entire graduate committee except for the member from outside the school. The school chair, if serving on the graduate committee as an ex-officio member, will be a non-voting member of this PEC. Initial work on the proposal should be initiated when the student begins taking cumulative examinations, as the first draft of the written proposal (see below) must be submitted to the PEC before the end of the student's fifth semester. Failure to submit the draft by the end of the fifth semester will result in discontinuation of assistantship support until the requirement is fulfilled. The student chooses the topic for an original research proposal. The topic must be approved by the Proposal Evaluation Committee (PEC) at a meeting in which the student outlines the proposal idea. The topic may use the techniques of the student's research project, but must not be an extension of the project. The proposal must be original with the student. After obtaining approval of the topic, the student will prepare a written proposal in accord with the prescribed format. (See Appendix IV.) During preparation, the student may obtain advice and suggestions from any faculty member but the proposal itself must be original with the student. The student must complete preparation of the proposal and submit it to the PEC before January of his or her third calendar year. The committee is allowed one week for evaluation of the proposal. The evaluation will include at least one meeting of the PEC. The evaluation shall be by a numerical score from 1.0 (lowest) to 4.0 (highest). An average score of 3.0 shall be required to pass. The scores will be accompanied by a written review by each voting PEC member. If the score is less than 3.0, the proposal must be revised and resubmitted within 30 days. The re-evaluation will follow the same procedure as described above. Only one re-submission is allowed. A second failure will be reported in writing by the PEC to the School Chair and to the Director of Graduate Studies. The latter will request that the Graduate School terminate the student from our doctoral program. In most cases, the students will be eligible for a Master’s degree. When the score is less than 3.0, copies of the final approved proposal must be provided to all members of the student's graduate committee at least one week before the date of the preliminary oral examination. Within 30 days of receiving notification of a passing grade, the student shall schedule a preliminary oral examination (defense of the proposal). This oral defense shall consist of a formal open seminar at which the student will present the proposal for credit as Chemistry 595. After questions from the general audience, the student's graduate committee will conduct an oral examination of the student. The grade for Chemistry 595 is based on the oral presentation and is independent of the oral examination. Only one attempt is allowed to pass the preliminary oral examination (defense of the research proposal). However, if the committee cannot decide whether to pass or fail the student at the end of the scheduled examination time, they may vote to continue the examination at a later date. Only one such continuation is allowed. The decision of the committee to pass the student or to continue the examination must be made with a majority vote of the committee. The student, the School Chair, and the director of graduate studies will be notified by the Chair of the graduate committee in writing on the next working day after the examination whether the result was Pass, Fail, or Continue. If a continuation is required, it must be scheduled no earlier than 30 days and no later than 90 days after the original oral examination date. Students in the Ph. D. program must complete the proposal defense by the end of third year in residence. Failure to complete the proposal defense by the end of third year will result in discontinuation of assistantship support until the requirement is fulfilled. If the student has not completed the defense by the end of the third year, the student will have one semester in which to complete the proposal defense (without assistantship support). Failure to complete the proposal by the deadline will result in termination from the graduate program. 4/5 Effective 12/13/07

A research project is required of all graduate students. A student in the doctoral program must earn at least 32 credit hours in research and dissertation (Chemistry 598 and 600). A minimum of 24 hours must be dissertation credit (Chemistry 600). The results of the research must be presented in the form of a dissertation acceptable both to the student's committee and to the Graduate School.

Original Research Proposal – Inorganic

As part of the written requirement for the Ph.D. degree, students will propose, write, and defend an original research proposal in their third year of graduate studies.

Scope of the Proposal

The proposal should describe a research idea that directly addresses a gap in knowledge. The topic area of your proposal should be outside the scope of your Ph.D. and undergraduate research areas. Proposals that explore a field or topic far from your current research are encouraged. If you have any questions about the scope of your proposal, please contact your advisor or a divisional representative.

Proposal Timeline:

December: Proposal abstracts due, with the goal of returning faculty feedback before the December holiday break. Faculty will red, green, or yellow light abstracts with written comments to aid in improving or guiding the trajectory of topic for development into a full proposal. In cases of a red light, a new topic may be requested.

January: Full proposal due to the inorganic faculty

February: Scheduled oral presentation and defense.

Possible Outcomes:

- Pass: no additional work required

- Partial Pass: deficiencies noted in the written or oral presentation and additional written or oral material may be required

- Unsatisfactory: students are required to repeat the proposal process during their 4th year with a new topic

Guidelines for Proposal Abstract

Students will submit a two-page abstract that the faculty will evaluate for feasibility as a topic for a full proposal. The abstract should succinctly describe the gap in knowledge, outline the proposed research to fill the gap, and describe the impact of the proposed work. Graphical content is encouraged. Refrain from including technical details, these will be developed as part of the full proposal.

A number of questions often come up with regards to the goal and structure of the proposal abstract. Here are a few comments designed to help you find the right balance…

- 1 page is often too short/3 pages is too long. Aim for 2 pages with a few embedded figures and/or schemes to help convey the key concepts you intend to explore. Make it visually appealing and easy to read so that your reader is more apt to actually read it.

- This is not a review article. Give enough background to convince your reader that this isn’t a nothing-burger, but make focus the text on your idea, your hypothesis, and your really cool way of tackling the problem.

- Pick a topic that excites you, one that you want to spend time exploring. Don’t worry if it doesn’t sound “inorganic enough”, as long as we can cover the topic adequately it’s all good. You’ll know if the topic is too close to what you are currently doing.

- Most strong proposals, even interdisciplinary ones, have a core “chemistry question” that can be highlighted. It can be helpful to start thinking about what variables can be tuned and what those variations will teach you.

Guidelines for a Full Proposal

1. project summary.

1 page limit. This is a self-contained, third-person description of objectives, methods, significance. Reviewers will use the abstract as a tool to construct their review, so it needs to be carefully written with that in mind. You want them to know what the key elements of your project are and their significance in the context of current knowledge.

2. Project Description

The project description has a 10 page limit, single spaced, including figures.

2.1 Goals and Importance

2.1.1 State Goals and Objectives

What are the main scientific challenges? Emphasize what the new ideas are. Briefly describe the project’s major goals and their impact on the state of the art.

- Clearly state the question you will address.

2.1.2 Establish Importance

- Why is this research area important? What makes something important varies with the field. For some fields, the intellectual challenge should be emphasized, for others the practical applications should be emphasized.

- Why is it an interesting/difficult/challenging question? It must be neither trivial nor impossible.

- What long-term technical goals will this work serve?

- What are the main barriers to progress? What has led to success so far and what limitations remain? What is the missing knowledge?

- What aspects of the current state-of-the-art lead to this proposal? Why are these the right issues to be addressing now?

- What lessons from past and current research motivate your work? What value will your research provide? What is it that your results will make possible?

2.1.3 Introduce the Proposed Work

- Identify the gap(s) in the field

- Introduce your project to fill the gap(s)

- Clearly explain the relation to the present state of knowledge, to current work here & elsewhere. Cite those whose work you’re building on (and whom you would like to have review your proposal). Don’t insult anyone. For example, don’t say their work is “inadequate;” rather, identify the issues they didn’t address.

Surprisingly, this section can kill a proposal. You need to be able to put your work in context. Often, a proposal will appear naive because the relevant literature is not cited. If it looks like you are planning to reinvent the wheel (and have no idea that wheels already exist), then no matter how good the research proposal itself is, your proposal won’t get funded. If you trash everyone else in your research field, saying their work is no good, you also will not get funded.

You can build your credentials in this section by summarizing other people’s work clearly and concisely and by stating how your work uses their ideas and how it differs from theirs.

2.2 Experimental Approach

- Provide a broad technical description of research plan: activities, methods, data, and theory.

Write to convince the best person in your field that your idea deserves funding. Simultaneously, you must convince someone who is very smart but has no background in your sub-area. The goal of your proposal is to persuade the reviewers that your ideas are so important that they will take money out of the taxpayers’ pockets and hand it to you.

This is the part that counts. WHAT will you do? Why is your strategy an appropriate one to pursue? What is the key idea that makes it possible for you to answer this question? HOW will you achieve your goals? What will you learn through this proposed work? Concisely and coherently, this section should complete the arguments developed earlier and present your initial pass on how to solve the problems posed. Avoid repetitions and digressions.

The question is: What will we know when you’re done that we don’t know now? The question is not: What will we have that we don’t have now? That is, rather than saying that you will develop a system that will do X, Y and Z, instead say why it is important to be able to do X, Y and Z; why X, Y and Z can’t be done now; how you are going to go about making X, Y and Z possible; and, what new knowledge or insights you will gain along the way.

2.3 Outcomes and Impact 2.3.1 Plan of work

- Present a plan for how you will go about attacking/solving the questions you have raised.

- Discuss expected results and a plan for evaluating the results. How will you measure progress?

Include a summary of milestones and expected dates of completion. You are not committed to following this plan – but you must present a FEASIBLE plan to convince the reviewers that you know how to go about getting research results.

2.3.2 List Expected Outcomes

2.3.3 Conclude the Proposed Work

- Reiterate the goals and importance

- Address any broader impacts

3. References

- Pertinent literature referenced within the project description.