- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Japanese Internment Camps

By: History.com Editors

Updated: April 17, 2024 | Original: October 29, 2009

Japanese internment camps were established during World War II by President Franklin D. Roosevelt through his Executive Order 9066 . From 1942 to 1945, it was the policy of the U.S. government that people of Japanese descent, including U.S. citizens, would be incarcerated in isolated camps. Enacted in reaction to the Pearl Harbor attacks and the ensuing war, the incarceration of Japanese Americans is considered one of the most atrocious violations of American civil rights in the 20th century.

Executive Order 9066

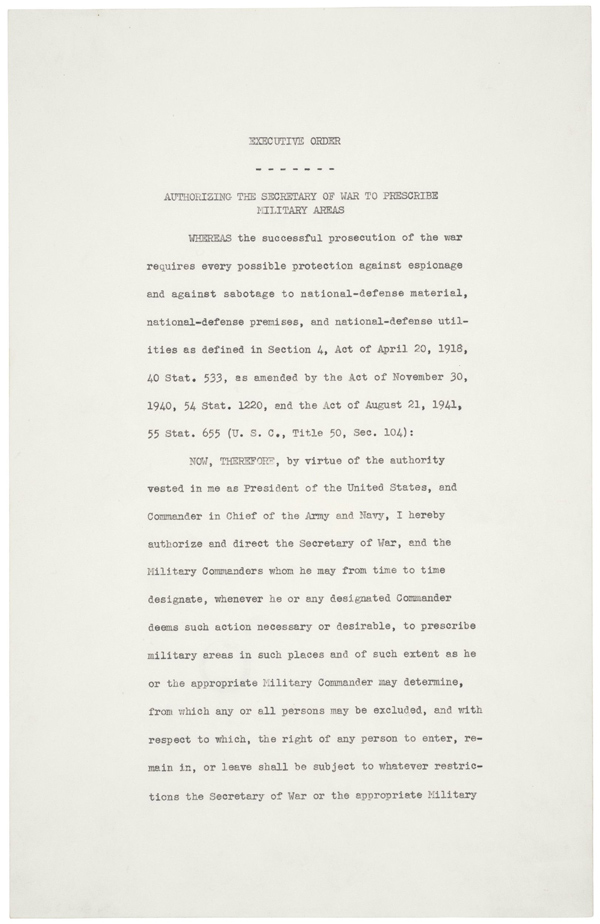

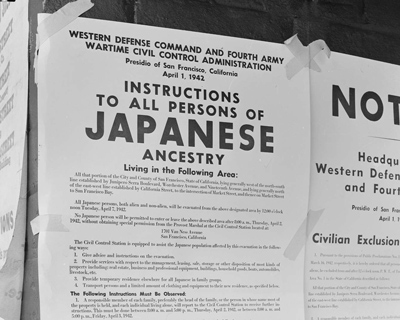

On February 19, 1942, shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor by Japanese forces, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 with the stated intention of preventing espionage on American shores.

Military zones were created in California, Washington and Oregon—states with a large population of Japanese Americans. Then Roosevelt’s executive order forcibly removed Americans of Japanese ancestry from their homes. Executive Order 9066 affected the lives about 120,000 people—the majority of whom were American citizens.

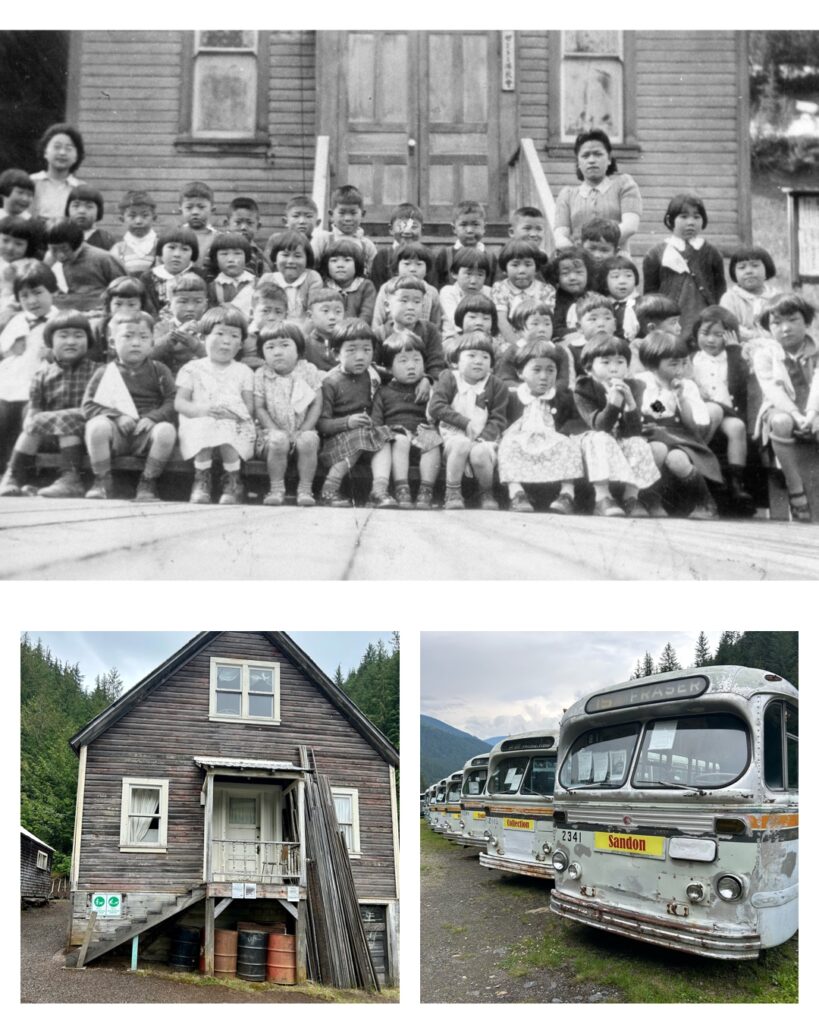

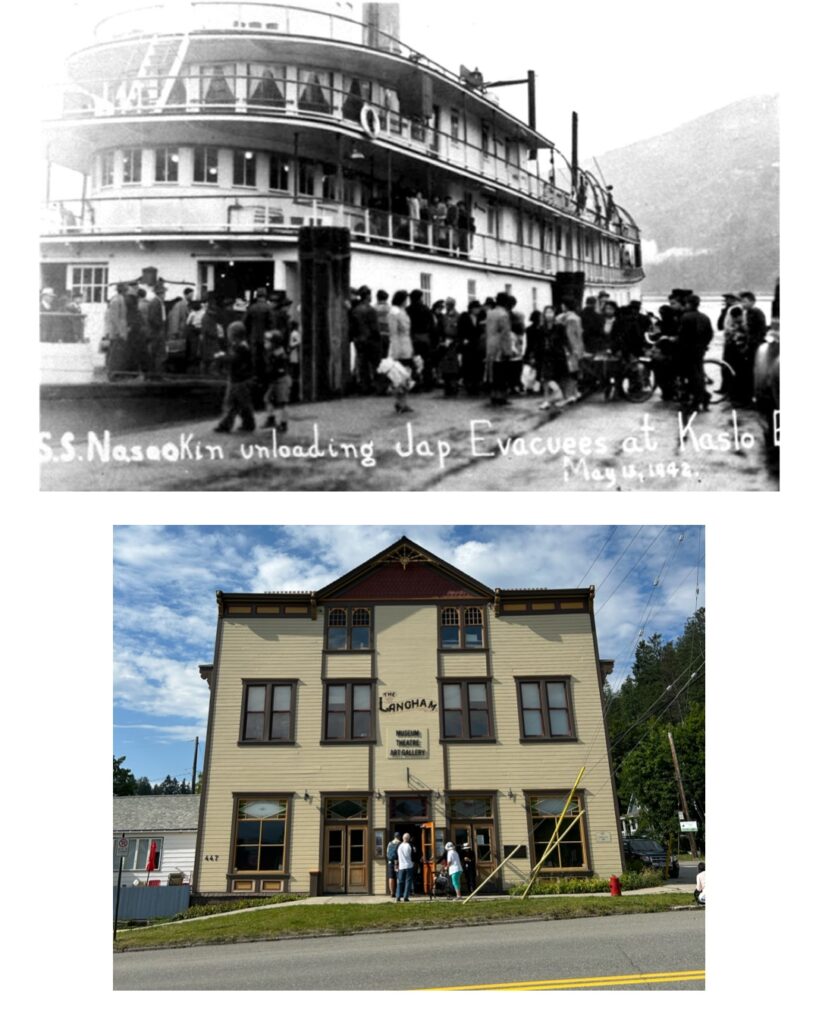

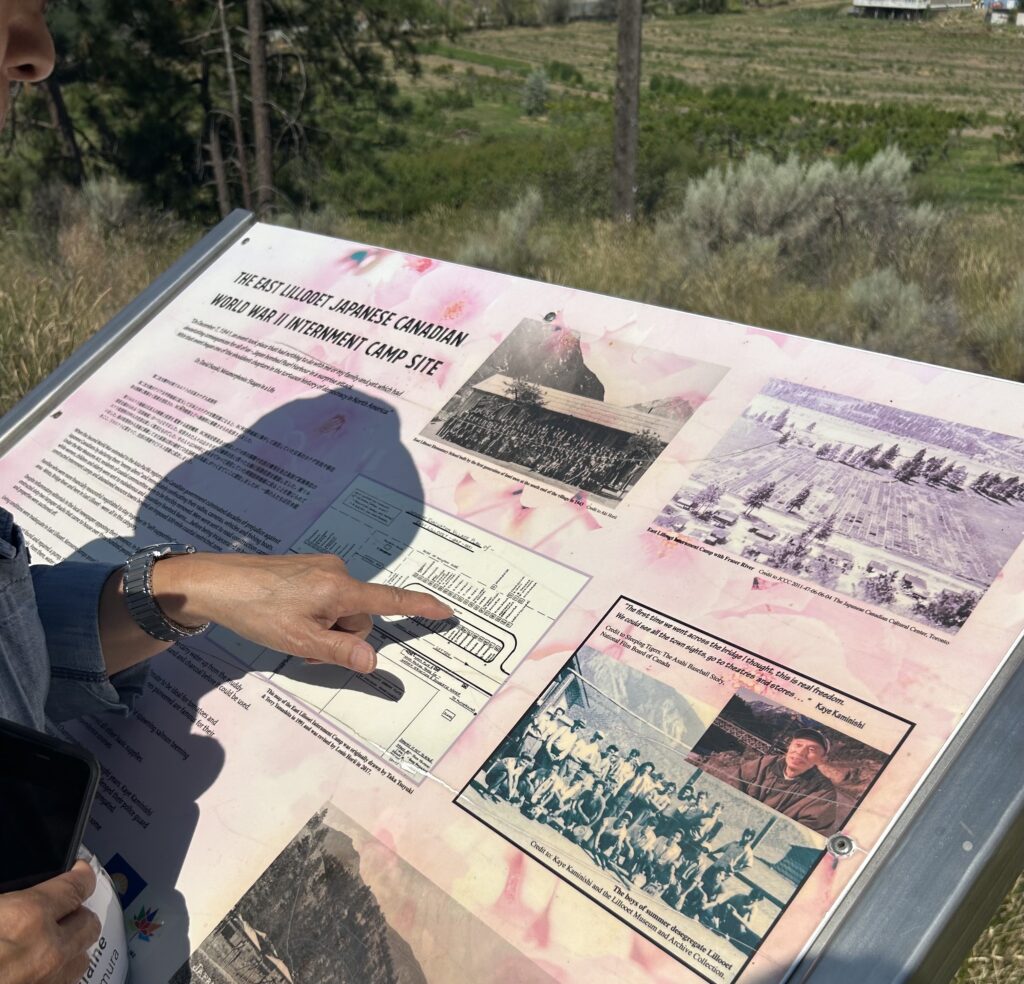

Canada soon followed suit, forcibly removing 21,000 of its residents of Japanese descent from its west coast. Mexico enacted its own version, and eventually 2,264 more people of Japanese descent were forcibly removed from Peru, Brazil, Chile and Argentina to the United States.

Anti-Japanese American Activity

Weeks before the order, the Navy removed citizens of Japanese descent from Terminal Island near the Port of Los Angeles.

On December 7, 1941, just hours after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the FBI rounded-up 1,291 Japanese American community and religious leaders, arresting them without evidence and freezing their assets.

In January, the arrestees were transferred to prison camps in Montana, New Mexico and North Dakota, many unable to inform their families and most remaining for the duration of the war.

Concurrently, the FBI searched the private homes of thousands of Japanese American residents on the West Coast, seizing items considered contraband.

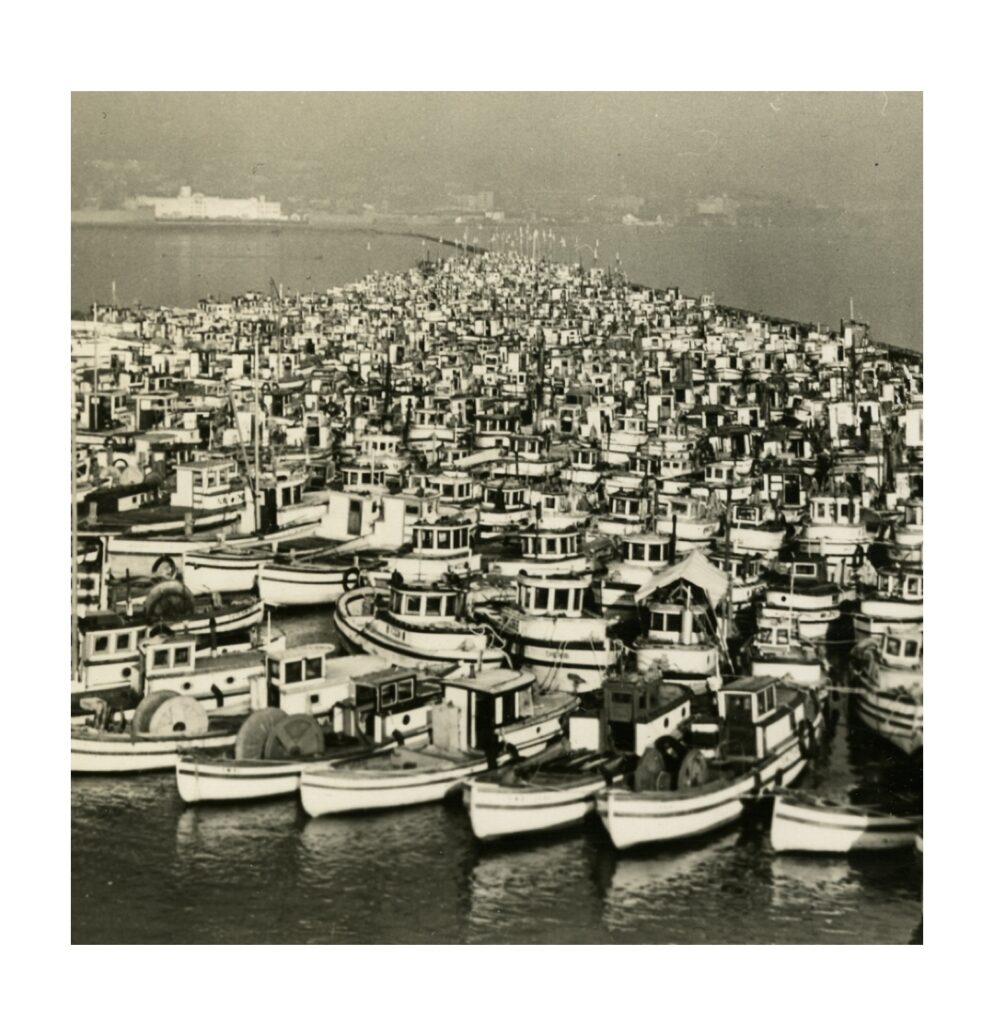

One-third of Hawaii’s population was of Japanese descent. In a panic, some politicians called for their mass incarceration. Japanese-owned fishing boats were impounded.

Some Japanese American residents were arrested and 1,500 people—one percent of the Japanese population in Hawaii—were sent to prison camps on the U.S. mainland.

Photos of Japanese American Relocation and Incarceration

John DeWitt

Lt. General John L. DeWitt, leader of the Western Defense Command, believed that the civilian population needed to be taken control of to prevent a repeat of Pearl Harbor.

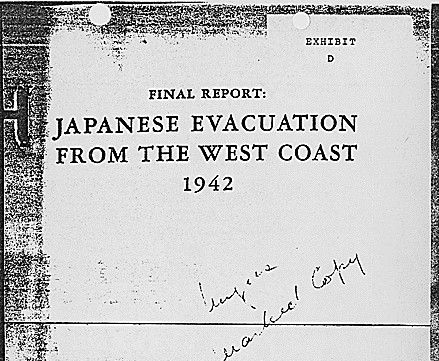

To argue his case, DeWitt prepared a report filled with known falsehoods, such as examples of sabotage that were later revealed to be the result of cattle damaging power lines.

DeWitt suggested the creation of the military zones and Japanese detainment to Secretary of War Henry Stimson and Attorney General Francis Biddle. His original plan included Italians and Germans, though the idea of rounding-up Americans of European descent was not as popular.

At Congressional hearings in February 1942, a majority of the testimonies, including those from California Governor Culbert L. Olson and State Attorney General Earl Warren , declared that all Japanese should be removed.

Biddle pleaded with the president that mass incarceration of citizens was not required, preferring smaller, more targeted security measures. Regardless, Roosevelt signed the order.

War Relocation Authority

After much organizational chaos, about 15,000 Japanese Americans willingly moved out of prohibited areas. Inland state citizens were not keen for new Japanese American residents, and they were met with racist resistance.

Ten state governors voiced opposition, fearing the Japanese Americans might never leave, and demanded they be locked up if the states were forced to accept them.

A civilian organization called the War Relocation Authority was set up in March 1942 to administer the plan, with Milton S. Eisenhower from the Department of Agriculture to lead it. Eisenhower only lasted until June 1942, resigning in protest over what he characterized as incarcerating innocent citizens.

Relocation to 'Assembly Centers'

Army-directed removals began on March 24. People had six days notice to dispose of their belongings other than what they could carry.

Anyone who was at least 1/16th Japanese was evacuated, including 17,000 children under age 10, as well as several thousand elderly and disabled residents.

Japanese Americans reported to "Assembly Centers" near their homes. From there they were transported to a "Relocation Center" where they might live for months before transfer to a permanent "Wartime Residence."

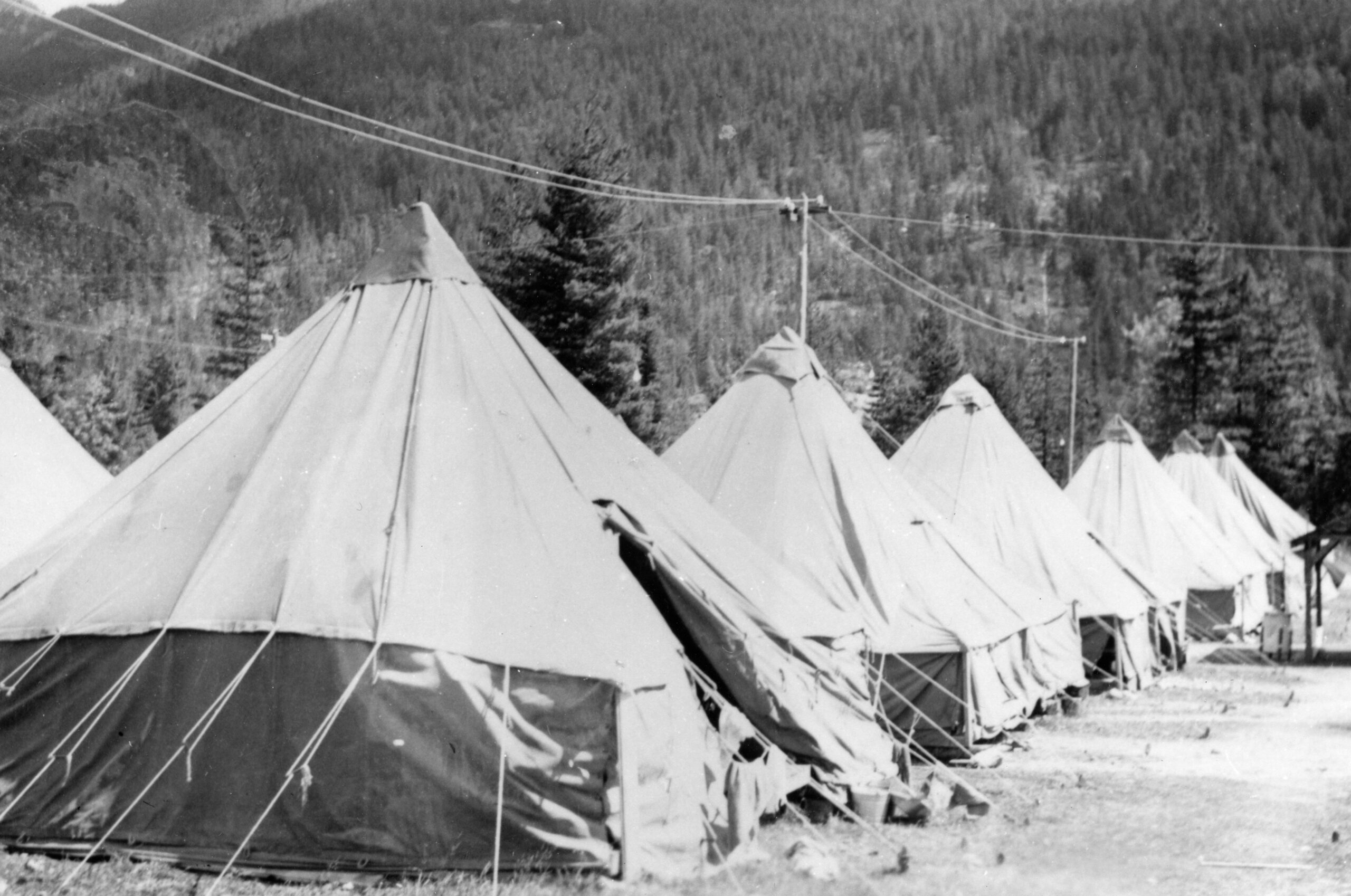

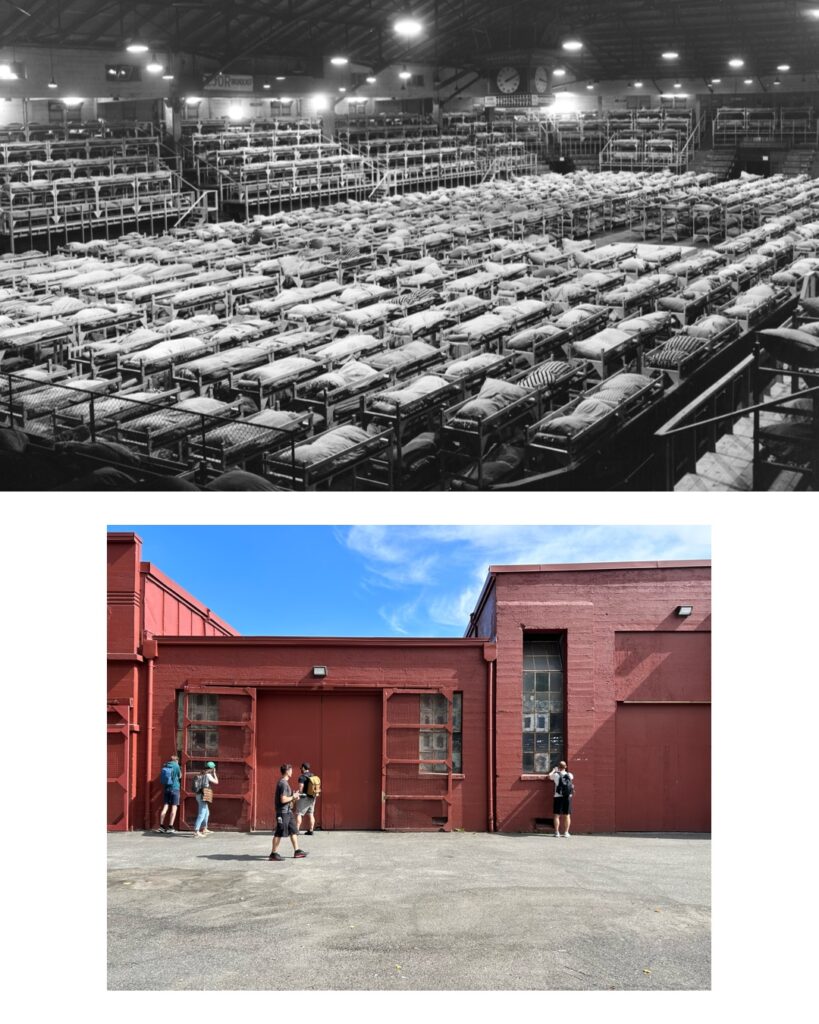

Assembly Centers were located in remote areas, often reconfigured fairgrounds and racetracks featuring buildings not meant for human habitation, like horse stalls or cow sheds, that had been converted for that purpose. In Portland, Oregon , 3,000 people stayed in the livestock pavilion of the Pacific International Livestock Exposition Facilities.

The Santa Anita Assembly Center, just several miles northeast of Los Angeles, was a de-facto city with 18,000 incarcerated, 8,500 of whom lived in stables. Food shortages and substandard sanitation were prevalent in these facilities.

Life in 'Assembly Centers'

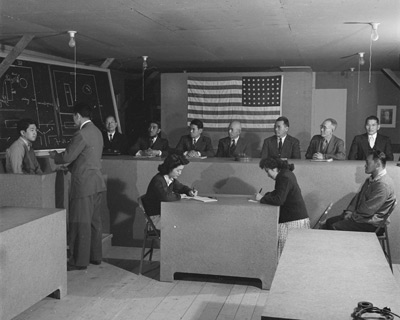

Assembly Centers offered work to prisoners with the policy that they should not be paid more than an Army private. Jobs ranged from doctors to teachers to laborers and mechanics. A couple were the sites of camouflage net factories, which provided work.

Over 1,000 incarcerated Japanese Americans were sent to other states to do seasonal farm work. Over 4,000 of the incarcerated population were allowed to leave to attend college.

Conditions in 'Relocation Centers'

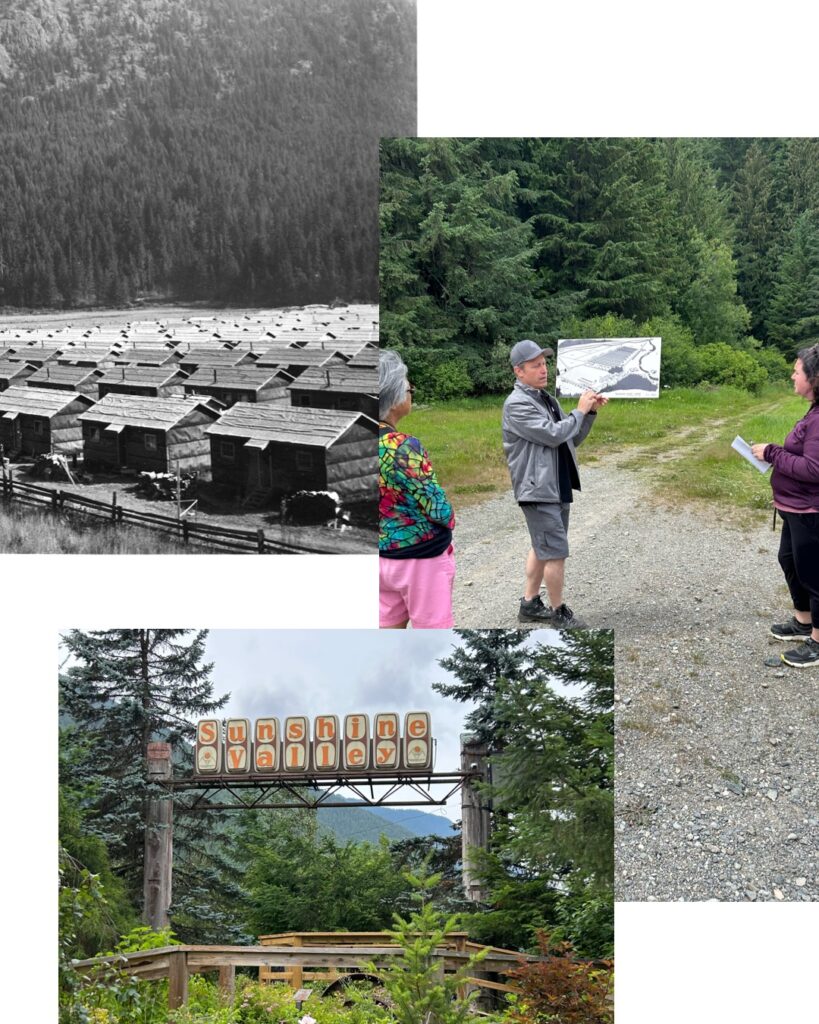

There were a total of 10 prison camps, called "Relocation Centers." Typically the camps included some form of barracks with communal eating areas. Several families were housed together. Residents who were labeled as dissidents were forced to a special prison camp in Tule Lake, California.

Two prison camps in Arizona were located on Native American reservations, despite the protests of tribal councils, who were overruled by the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Each Relocation Center was its own "town," and included schools, post offices and work facilities, as well as farmland for growing food and keeping livestock. Each prison camp "town" was completely surrounded by barbed wire and guard towers.

Net factories offered work at several Relocation Centers. One housed a naval ship model factory. There were also factories in different Relocation Centers that manufactured items for use in other prison camps, including garments, mattresses and cabinets. Several housed agricultural processing plants.

Violence in Prison Camps

Violence occasionally occurred in the prison camps. In Lordsburg, New Mexico , prisoners were delivered by trains and forced to march two miles at night to the camp. On July 27, 1942, during a night march, two Japanese Americans, Toshio Kobata and Hirota Isomura, were shot and killed by a sentry who claimed they were attempting to escape. Japanese Americans testified later that the two elderly men were disabled and had been struggling during the march to Lordsburg. The sentry was found not guilty by the army court martial board.

On August 4, 1942, a riot broke out in the Santa Anita Assembly Center, the result of anger about insufficient rations and overcrowding. At California's Manzanar War Relocation Center , tensions resulted in the beating of Fred Tayama, a Japanese American Citizen’s League (JACL) leader, by six men. JACL members were believed to be supporters of the prison camp's administration.

Fearing a riot, police tear-gassed crowds that had gathered at the police station to demand the release of Harry Ueno. Ueno had been arrested for allegedly assaulting Tayama. James Ito was killed instantly and several others were wounded. Among those injured was Jim Kanegawa, 21, who died of complications five days later.

At the Topaz Relocation Center , 63-year-old prisoner James Hatsuki Wakasa was shot and killed by military police after walking near the perimeter fence. Two months later, a couple was shot at for strolling near the fence.

In October 1943, the Army deployed tanks and soldiers to Tule Lake Segregation Center in northern California to crack down on protests. Japanese American prisoners at Tule Lake had been striking over food shortages and unsafe conditions that had led to an accidental death in October 1943. At the same camp, on May 24, 1943, James Okamoto, a 30-year-old prisoner who drove a construction truck, was shot and killed by a guard.

Fred Korematsu

In 1942, 23-year-old Japanese-American Fred Korematsu was arrested for refusing to relocate to a Japanese prison camp. His case made it all the way to the Supreme Court, where his attorneys argued in Korematsu v. United States that Executive Order 9066 violated the Fifth Amendment .

Korematsu lost the case, but he went on to become a civil rights activist and was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1998. With the creation of California’s Fred Korematsu Day, the United States saw its first U.S. holiday named for an Asian American. But it took another Supreme Court decision to halt the incarceration of Japanese Americans.

Mitsuye Endo

The prison camps ended in 1945 following the Supreme Court decision, Ex parte Mitsuye Endo . In this case, justices ruled unanimously that the War Relocation Authority “has no authority to subject citizens who are concededly loyal to its leave procedure.”

The case was brought on behalf of Mitsuye Endo, the daughter of Japanese immigrants from Sacramento, California. After filing a habeas corpus petition, the government offered to free her, but Endo refused, wanting her case to address the entire issue of Japanese incarceration.

One year later, the Supreme Court made the decision, but gave President Truman the chance to begin camp closures before the announcement. One day after Truman made his announcement, the Supreme Court revealed its decision.

Reparations

The last Japanese internment camp closed in March 1946. President Gerald Ford officially repealed Executive Order 9066 in 1976, and in 1988, Congress issued a formal apology and passed the Civil Liberties Act awarding $20,000 each to over 80,000 Japanese Americans as reparations for their treatment.

Japanese Relocation During World War II . National Archives . Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites. J. Burton, M. Farrell, F. Lord and R. Lord . Lordsburg Internment POW Camp. Historical Society of New Mexico . Smithsonian Institute .

Watch the documentary event, FDR . Available to stream now.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

History Cooperative

Japanese Internment Camps: WWII, Reasons, Life, Conditions, and Deaths

The story of Japanese internment camps in the United States represents a complex chapter marked by fear, prejudice, and a struggle for justice. Amid the global conflict, the U.S. government made the controversial decision to relocate and imprison thousands of Japanese Americans, casting a long shadow over the principles of liberty and justice.

This key moment, driven by wartime hysteria and racial discrimination, led to the uprooting of families, the loss of homes and businesses, and the creation of a stark reality behind barbed wire.

Table of Contents

Events Leading Up to the Foundation of Japanese Internment Camps

The road to the establishment of Japanese internment camps was paved with a blend of international tensions and domestic fears. The bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, by the Empire of Japan marked a turning point, thrusting the United States into World War II amidst a wave of panic and suspicion.

READ MORE: Pearl Harbor: A Day in Infamy

Overnight, Japanese Americans, many of whom were U.S. citizens or legal residents who had lived in the country for decades, were viewed with distrust and hostility. This fear was not born in a vacuum but was the culmination of years of anti-Japanese sentiment , exacerbated by economic competition and racial prejudices that had simmered on the American West Coast.

The swift move toward internment was further influenced by government and military leaders who argued that Japanese Americans could pose a security threat. Among them, General John L. DeWitt, head of the Western Defense Command, played a key role in advocating for the exclusion and detention of Japanese Americans, claiming military necessity .

This atmosphere of fear and suspicion was codified with President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s signing of Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942. This order authorized the Secretary of War and military commanders to designate military areas from which any or all persons could be excluded, laying the groundwork for the relocation of Japanese Americans to internment camps.

This decision, fueled by wartime paranoia and racial bias, led to one of the most contentious civil liberties issues of the 20th century, challenging the American ideals of justice and equality.

Executive Order 9066

Executive Order 9066, signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, 1942, marked a decisive moment in American history, granting military commanders the authority to exclude any persons from designated military areas.

READ MORE: US History Timeline: The Dates of America’s Journey

Though the order did not specify Japanese Americans, it was implemented to target and relocate them from the West Coast, under the guise of national security. The swift enactment of this order reflected the heightened fear and prejudice against Japanese Americans following the Pearl Harbor attack, culminating in a policy that would affect the lives of thousands.

The implications of Executive Order 9066 were profound and immediate. It led to the creation of military zones and the forced removal of Japanese Americans to internment camps scattered across the interior of the U.S. Families were given mere days to dispose of their properties, businesses, and belongings, often at significant losses.

The order stripped them of their freedoms, rights, and dignity , casting a shadow over the principles of liberty and justice the nation purported to uphold. This chapter in American history serves as a stark reminder of the dangers of wartime hysteria and racial prejudice, highlighting the need for vigilance in protecting the rights and freedoms of all citizens, especially in times of crisis.

Anti-Japanese American Activity

In the years leading up to World War II, anti-Japanese sentiment had been brewing, particularly on the West Coast of the United States, where the majority of Japanese immigrants and their descendants lived. This animosity was deeply rooted in a mixture of racial prejudice, economic envy, and cultural misunderstanding.

READ MORE: WW2 Timeline and Dates

Japanese Americans, despite contributing to the agricultural and economic development of the region, faced discriminatory laws and societal exclusion. The tensions escalated with Japan’s growing military aggression in Asia, further fueling suspicion and xenophobia among the American public.

The attack on Pearl Harbor acted as a catalyst, transforming pre-existing biases into outright hostility. Politicians, media outlets, and influential community leaders began to advocate for the removal of Japanese Americans from the Pacific Coast, falsely accusing them of espionage and sabotage without evidence. This climate of fear and suspicion was not only endorsed but amplified by the federal government’s actions, including Executive Order 9066.

The ensuing anti-Japanese American activity was not merely a grassroots movement but a state-sanctioned policy that legitimized racism and set the stage for the mass incarceration of an entire ethnic group based solely on their ancestry. This period underscores the impact of wartime hysteria combined with racial prejudice, leading to one of the most significant violations of civil liberties in American history.

John DeWitt and His Role in the Internment of Japanese-Americans

Major General John L. DeWitt played a key role in the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. As the commanding officer of the Western Defense Command, DeWitt was tasked with the defense of the Pacific Coast following the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Citing concerns over espionage and sabotage, he became one of the most vocal proponents for the removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast. DeWitt’s influence was instrumental in shaping the narrative that Japanese Americans posed a national security threat , despite the lack of evidence to support such claims.

DeWitt’s reports and recommendations to the War Department emphasized the perceived impossibility of distinguishing loyal from disloyal Japanese Americans, arguing that, because of their race, they could not be trusted.

His stance was fortified by racial prejudices and a belief in the necessity of drastic measures to ensure national security. His advocacy was a critical factor leading to the issuance of Executive Order 9066 by President Roosevelt.

DeWitt subsequently oversaw the implementation of the order, orchestrating the forced removal and internment of over 110,000 Japanese Americans . His actions, driven by a mixture of wartime hysteria and racial bias, have been widely criticized by historians as unjust and unnecessary, reflecting a dark chapter in the history of civil liberties in the United States.

War Relocation Authority

The War Relocation Authority (WRA) was established on March 18, 1942, through Executive Order 9102 , signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Tasked with managing the forced relocation and internment of Japanese Americans, the WRA represented the bureaucratic machinery behind the internment process .

It was responsible for the logistics, administration, and oversight of the camps, ensuring the implementation of government policy. Under the direction of Milton S. Eisenhower, initially, and later Dillon S. Myer, the WRA navigated the complex logistics of uprooting over 120,000 individuals, two-thirds of whom were American citizens , from their homes and moving them to isolated internment camps across the interior of the United States.

The establishment of the WRA marked a critical phase in the internment process, transitioning from the chaotic initial roundup to a more structured, though still harsh, system of incarceration . The Authority attempted to mitigate the harsh conditions through education and employment opportunities within the camps, but these efforts did little to mask the reality of imprisonment.

The WRA’s role in overseeing the daily lives of internees, from providing basic necessities to enforcing camp rules, highlighted the extent of government involvement in this dark chapter of American history.

Despite its attempts to portray the camps in a positive light, the legacy of the WRA remains intertwined with the violation of civil liberties and the suffering of Japanese Americans during World War II.

Relocation to ‘Assembly Centers’

Before their final transfer to internment camps, Japanese Americans were initially relocated to temporary “ assembly centers .” These were often hastily converted facilities such as racetracks, fairgrounds, and other public buildings, ill-equipped to house the thousands of people who were uprooted from their communities.

Families were given only days to settle their affairs before being evacuated, forcing them to sell their possessions at significant losses or leave them behind entirely. Upon arrival at these centers, they were met with overcrowded conditions, inadequate privacy, and insufficient sanitation facilities, a stark departure from their previous lives and an ominous introduction to their forthcoming internment experience.

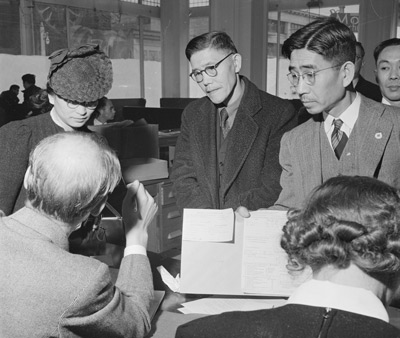

The assembly centers served as a transitional phase in the internment process, where individuals were registered and assigned to one of the more permanent internment camps managed by the War Relocation Authority.

Life in these temporary quarters was marked by uncertainty and anxiety, as internees awaited their fate in the unknown conditions of the permanent camps. The use of assembly centers highlighted the logistical challenges and bureaucratic indifference faced by Japanese Americans during their relocation.

This phase of the internment process underscores the disruption of normal life and the rapid deprivation of rights and freedoms experienced by Japanese American families, setting the stage for their prolonged internment under challenging and unjust conditions.

Life in ‘Japanese Concentration Camps’

Life within the Japanese concentration camps was a stark departure from the freedoms of American society, defined by the physical and psychological barriers of barbed wire and guard towers .

READ MORE: Twisted Legacy: Uncovering Who Invented Barbed Wire and Why was Barbed Wire invented?

Despite being labeled as “relocation centers,” these facilities functioned as prisons, where internees faced a daily existence marked by a loss of privacy, autonomy, and dignity. Families, often accustomed to their own homes, were crammed into small, sparsely furnished barracks with little insulation against harsh weather conditions.

The communal facilities for eating, bathing, and using the restroom further eroded personal privacy and comfort.

Yet, within these confines, the Japanese American community strove to maintain a sense of normalcy and resilience. Schools were established for children, and adults engaged in various jobs within the camps to support the community and earn a small income.

READ MORE: Who Invented School? The Story Behind Monday Mornings

Internees organized cultural and recreational activities, such as art classes, sports competitions, and traditional Japanese festivals , to preserve their heritage and bolster spirits. However, these efforts could not fully mitigate the underlying strain and injustice of their situation.

The internment experience left lasting scars on the community, impacting generations with memories of discrimination, loss, and resilience in the face of adversity.

U.S. Propaganda Film Shows ‘Normal’ Life in WWII Japanese Internment Camps

During World War II, the U.S. government engaged in a propaganda campaign to shape public perception of the internment camps housing Japanese Americans. One notable effort was the production of films that depicted a sanitized and misleading portrayal of life inside these camps.

These films aimed to pacify criticism and concern among the American public and international community by showing internees not as prisoners but as beneficiaries of government benevolence .

Through carefully crafted scenes, the films showcased internees engaging in educational activities, farming, and leisure—painting a picture of a harmonious and productive life far removed from the reality of internment.

This strategic use of propaganda served multiple purposes: it sought to justify the government’s internment policy, alleviate growing unease about the treatment of Japanese Americans, and counter any negative impressions that could affect the United States’ international standing during the war.

However, these films starkly contrasted with the testimonies of internees and reports from civil rights advocates, who highlighted the overcrowded living conditions, inadequate facilities, and the psychological toll of imprisonment.

The propaganda films obscured the harsh realities of internment, the stripping away of rights , and the deep wounds inflicted upon thousands of Japanese American families.

Conditions in ‘Relocation Centers’

The conditions in the so-called “ relocation centers ” or internment camps where Japanese Americans were confined during World War II were far from the idyllic scenes portrayed by U.S. government propaganda.

The reality of life in these camps was characterized by hardship, uncertainty, and a stark departure from the principles of freedom and justice. Internees faced a variety of challenging living conditions, from extreme weather to insufficient food and medical care.

The barracks that served as living quarters were poorly constructed and offered little protection against the searing summers and freezing winters common in the remote areas where many camps were located.

Moreover, the camps were designed with a minimum level of infrastructure, leading to overcrowded living spaces, shared latrines with no privacy, and inadequate medical facilities. Despite the efforts of internees to improve their living conditions through community organization and personal initiative, the scarcity of resources and the constant surveillance by military guards underscored the oppressive nature of their confinement.

The psychological impact of internment, including stress, anxiety, and loss of identity, compounded the physical hardships. Stories of resilience, community support, and cultural preservation emerged from within the camps, but these could not negate the injustice of the internment experience.

Violence in Prison Camps

Within the confines of the internment camps, instances of violence were relatively rare but notably significant, marking the tension and desperation that sometimes boiled over among the internees.

The stress of imprisonment, the erosion of community and family structures, and the frustration with unjust incarceration occasionally led to conflicts both among the internees and between internees and camp guards.

One of the most notable incidents of violence occurred at the Manzanar internment camp in December 1942 , known as the Manzanar Riot or Uprising, where tensions between the camp administration and the internees escalated into violence, resulting in the death of two Japanese Americans and injuries to several others.

These instances of violence were symptomatic of the broader issues within the camps: the struggle for leadership and representation among the internees , the inadequacy of the administration to address the internees’ concerns, and the underlying injustice of their situation. The presence of armed guards and the enforcement of strict regulations heightened the atmosphere of repression and control.

While the camps were not violent places on a day-to-day basis, these incidents of unrest underscored the inherent conflict of detaining loyal American citizens and residents without due process.

The violence that did erupt within the camps serves as a reminder of the profound impact of internment on the psyche and social dynamics of the Japanese American community , illustrating the complex interplay of resilience, despair, and resistance under the shadow of unjust incarceration.

The internment of Japanese Americans during World War II , while not characterized by the mass violence seen in other wartime atrocities, still led to loss of life under the harsh conditions and psychological strain of unjust incarceration.

Deaths in the internment camps occurred due to a variety of reasons, including inadequate medical care , the stress and despair of long-term confinement, and, in rare instances, violence. Elderly internees, children, and those with pre-existing health conditions were particularly vulnerable to the camps’ inadequate living conditions and limited access to healthcare.

The exact number of deaths across all the internment camps is difficult to ascertain, as records were not always meticulously kept or have been lost over time . However, each death within these camps represents a personal tragedy and a stark reminder of the human cost of policies born out of fear and prejudice.

Memorials and monuments have been erected in several former camp sites and cemeteries, serving as somber reminders of those who died as a result of their internment. These sites encourage reflection on the fragility of civil liberties in times of crisis and the importance of remembering the individuals and families affected by this chapter of American history.

10 Japanese Internment Camps

The internment of Japanese Americans during World War II led to the establishment of ten major camps across the United States, primarily located in remote areas far from the Pacific coast.

These camps were designed to house over 120,000 Japanese Americans forcibly removed from their homes in the wake of Executive Order 9066.

The locations of these camps were chosen based on their isolation and the government’s ability to control the internees, often placing them in harsh and unforgiving environments. Here is a brief overview of the ten major internment camps:

Manzanar War Relocation Center in California became one of the most well-known camps, symbolizing the hardships and resilience of the interned population.

Tule Lake Segregation Center in California, designated for those considered “disloyal,” was the largest of the camps and witnessed significant unrest and protest.

Minidoka War Relocation Center in Idaho, where internees worked in agriculture to support the war effort despite their confinement.

Topaz War Relocation Center in Utah, known for its harsh climate and the vibrant arts community that emerged among the internees.

Heart Mountain War Relocation Center in Wyoming, notable for its high school, which became the largest in the state due to the interned population.

Granada War Relocation Center (Amache) in Colorado, where internees faced some of the harshest living conditions.

Rohwer War Relocation Center in Arkansas, one of the two camps located in the humid and mosquito-infested swamps of the Mississippi Delta.

Jerome War Relocation Center in Arkansas, the other camp in the Delta, marked by its brief operation period and challenging conditions.

Gila River War Relocation Center in Arizona, distinguished by its leadership in agriculture and relatively better relations with the surrounding community.

Poston War Relocation Center in Arizona, the largest camp by area, located on an Indian reservation and suffering from extreme summer heat.

Each of these camps has its own history, marked by the resilience of the Japanese American community in the face of adversity. Today, they serve as poignant reminders of the need for vigilance against the erosion of civil liberties and the importance of remembering the lessons of the past.

Memorials and educational centers at some of these sites continue to educate the public about this dark chapter in American history, ensuring that the stories of those who were interned are not forgotten.

How to Cite this Article

There are three different ways you can cite this article.

1. To cite this article in an academic-style article or paper , use:

<a href=" https://historycooperative.org/japanese-internment-camps-in-america/ ">Japanese Internment Camps: WWII, Reasons, Life, Conditions, and Deaths</a>

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

American Incarceration

A Smithsonian magazine special report

The Injustice of Japanese-American Internment Camps Resonates Strongly to This Day

During WWII, 120,000 Japanese-Americans were forced into camps, a government action that still haunts victims and their descendants

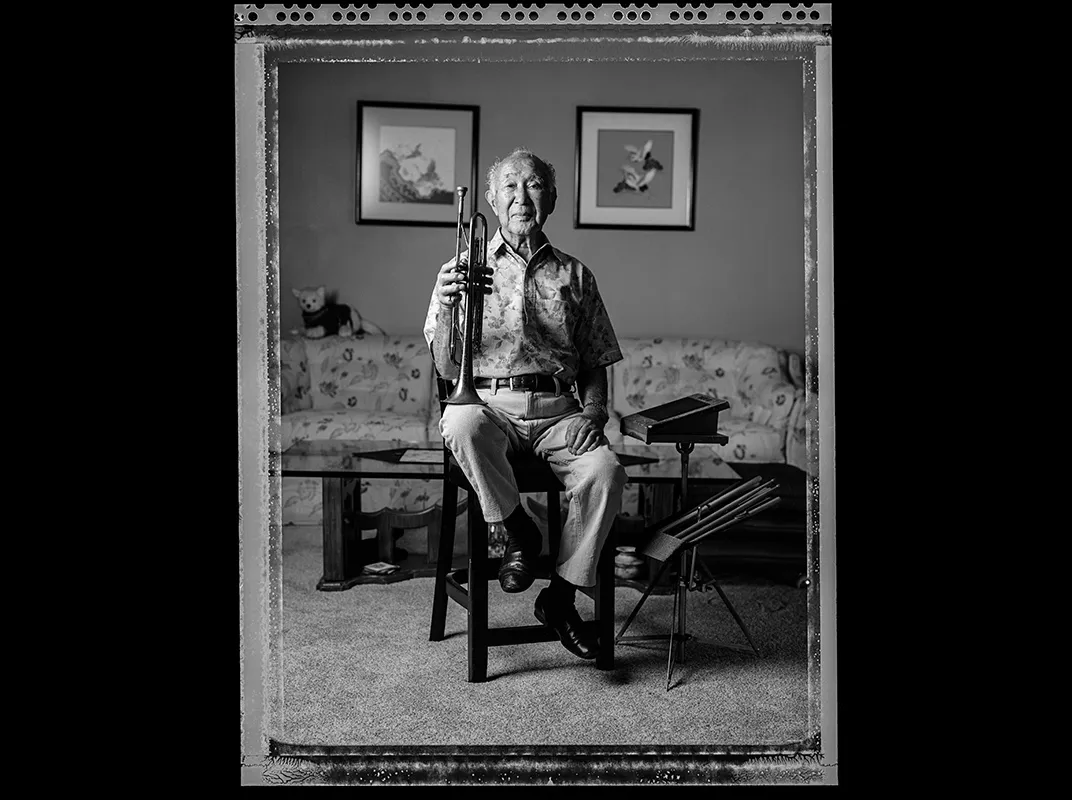

T.A. Frail; Photographs by Paul Kitagaki Jr.; Historical Photographs by Dorothea Lange

Jane Yanagi Diamond taught American History at a California high school, “but I couldn’t talk about the internment,” she says. “My voice would get all strange.” Born in Hayward, California, in 1939, she spent most of World War II interned with her family at a camp in Utah.

Seventy-five years after the fact, the federal government’s incarceration of some 120,000 Americans of Japanese descent during that war is seen as a shameful aberration in the U.S. victory over militarism and totalitarian regimes. Though President Ford issued a formal apology to the internees in 1976, saying their incarceration was a “setback to fundamental American principles,” and Congress authorized the payment of reparations in 1988, the episode remains, for many, a living memory. Now, with immigration-reform proposals targeting entire groups as suspect, it resonates as a painful historical lesson.

The roundups began quietly within 48 hours after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, on December 7, 1941. The announced purpose was to protect the West Coast. Significantly, the incarceration program got underway despite a warning; in January 1942, a naval intelligence officer in Los Angeles reported that Japanese-Americans were being perceived as a threat almost entirely “because of the physical characteristics of the people.” Fewer than 3 percent of them might be inclined toward sabotage or spying, he wrote, and the Navy and the FBI already knew who most of those individuals were. Still, the government took the position summed up by John DeWitt, the Army general in command of the coast: “A Jap’s a Jap. They are a dangerous element, whether loyal or not.”

That February, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, empowering DeWitt to issue orders emptying parts of California, Oregon, Washington and Arizona of issei—immigrants from Japan, who were precluded from U.S. citizenship by law—and nisei, their children, who were U.S. citizens by birth. Photographers for the War Relocation Authority were on hand as they were forced to leave their houses, shops, farms, fishing boats. For months they stayed at “assembly centers,” living in racetrack barns or on fairgrounds. Then they were shipped to ten “relocation centers,” primitive camps built in the remote landscapes of the interior West and Arkansas. The regime was penal: armed guards, barbed wire, roll call. Years later, internees would recollect the cold, the heat, the wind, the dust—and the isolation.

There was no wholesale incarceration of U.S. residents who traced their ancestry to Germany or Italy, America’s other enemies.

The exclusion orders were rescinded in December 1944, after the tides of battle had turned in the Allies’ favor and just as the Supreme Court ruled that such orders were permissible in wartime (with three justices dissenting, bitterly). By then the Army was enlisting nisei soldiers to fight in Africa and Europe. After the war, President Harry Truman told the much-decorated, all-nisei 442nd Regimental Combat Team: “You fought not only the enemy, but you fought prejudice—and you have won.”

If only: Japanese-Americans met waves of hostility as they tried to resume their former lives. Many found that their properties had been seized for nonpayment of taxes or otherwise appropriated. As they started over, they covered their sense of loss and betrayal with the Japanese phrase Shikata ga nai —It can’t be helped. It was decades before nisei parents could talk to their postwar children about the camps.

Paul Kitagaki Jr., a photojournalist who is the son and grandson of internees, has been working through that reticence since 2005. At the National Archives in Washington, D.C., he has pored over more than 900 pictures taken by War Relocation Authority photographers and others—including one of his father’s family at a relocation center in Oakland, California, by one of his professional heroes, Dorothea Lange. From fragmentary captions he has identified more than 50 of the subjects and persuaded them and their descendants to sit for his camera in settings related to their internment. His pictures here, published for the first time, read as portraits of resilience.

Jane Yanagi Diamond, now 77 and retired in Carmel, California, is living proof. “I think I’m able to talk better about it now,” she told Kitagaki. “I learned this as a kid—you just can’t keep yourself in gloom and doom and feel sorry for yourself. You’ve just got to get up and move along. I think that’s what the war taught me.”

Subject interviews conducted by Paul Kitagaki Jr.

Related Reads

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tom-frail-head-shot.jpeg)

T.A. Frail | READ MORE

Tom Frail is a senior editor for Smithsonian magazine. He previously worked as a senior editor for the Washington Post and for Philadelphia Newspapers Inc.

Paul Kitagaki Jr. | READ MORE

Paul Kitagaki Jr. is a senior photographer at The Sacramento Bee . His work has won numerous awards, including a shared Pulitzer Prize in 1990.

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Course: US history > Unit 7

- Beginning of World War II

- 1940 - Axis gains momentum in World War II

- 1941 Axis momentum accelerates in WW2

- Pearl Harbor

- FDR and World War II

Japanese internment

- American women and World War II

- 1942 Tide turning in World War II in Europe

- World War II in the Pacific in 1942

- 1943 Axis losing in Europe

- American progress in the Pacific in 1944

- 1944 - Allies advance further in Europe

- 1945 - End of World War II

- The Manhattan Project and the atomic bomb

- The United Nations

- The Second World War

- Shaping American national identity from 1890 to 1945

- President Franklin Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 resulted in the relocation of 112,000 Japanese Americans living on the West Coast into internment camps during the Second World War.

- Japanese Americans sold their businesses and houses for a fraction of their value before being sent to the camps. In the process, they lost their livelihoods and much of their lifesavings.

- In Korematsu v. United States (1944) the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of internment. In 1988, the United States issued an official apology for internment and compensated survivors.

Executive Order 9066

Korematsu v. united states (1944), aftermath and redress, what do you think.

- On internment, see Ira Katznelson, Fear Itself: The New Deal and The Origins of Our Time (New York: Liveright Publishing, 2013), 339; Roger Daniels, Sandra C. Taylor, Harry H.L. Kitano, eds., Japanese Americans, from Relocation to Redress (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1991); Wendy L. Ng, Japanese American Internment during World War II: A History and Reference Guide (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2002).

- See David M. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 754.

- Kennedy, Freedom from Fear , 756.

- Kennedy, Freedom from Fear , 757.

- “Abyss of racism . . .” quoted in Peter Irons, Justice at War: The Story of the Japanese-American Internment Cases (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 335. “I dissent . . .” quoted in Otis Stephens and John Scheb, American Constitutional Law , v. 1 (Belmont, CA: Thomson/Wadsworth, 2008), 224.

- Kennedy, Freedom from Fear , 759.

- Kennedy, Freedom from Fear , 760.

- William Yoshino and John Tateishi, " The Japanese American Incarceration: The Journey to Redress ," excerpted from Human Rights , American Bar Association, Spring 2000.

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

U.S. History

Teaching Japanese-American Internment Using Primary Resources

Rarely seen photos of japanese internment.

View Slide Show ›

By Marjorie Backman and Michael Gonchar

- Dec. 7, 2017

The day after the early-morning surprise assault on Pearl Harbor, on Dec. 7, 1941, the United States formally declared war on Japan and entered World War II. Over the next few months, almost 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry, over 60 percent of whom were American citizens, were removed from their homes, businesses and farms on the West Coast and forced to live in internment camps. Why? The United States government feared that these individuals, simply because of their ethnicity, posed a national security threat.

More than 40 years later, Congress passed legislation mandating apologies and reparations for violations of the civil liberties and the constitutional rights of those incarcerated during the war. “It’s not for us today to pass judgment upon those who may have made mistakes while engaged in that great struggle,” said President Ronald Reagan, on signing the 1988 legislation. “Yet we must recognize that the internment of Japanese-Americans was just that, a mistake.”

In this lesson, students use original Times reporting and other resources to investigate the forced internment of Japanese-Americans — and track how the government has gradually apologized for some of its actions over the decades. Students will also have the opportunity to look for echoes in today’s world of this difficult chapter in American history.

Arrests, Roundups and Internment

Primary sources: newspaper articles and editorials

Background: Over time, almost 120,000 Japanese-Americans, regardless of whether they were immigrants or had been born in the United States, were evacuated from their homes and brought to temporary assembly centers before being confined to one of several remote internment camps.

Students will square these events with the sobering findings of this 1983 government report : “All this was done despite the fact that not a single documented act of espionage, sabotage or fifth column activity was committed by an American citizen of Japanese ancestry or by a resident Japanese alien on the West Coast.”

Activity: Working in small groups, students should read one or more of these New York Times articles from the time period. Their goal? To figure out what they can find in 1940s news coverage that explains why the American government forced people from their homes into internment camps simply because of their ethnicity, and why the rest of the country let it happen.

Students should look for the following:

• explicit or implied reasons given within the articles to justify the roundups • clues within the writing itself (such as the words used to describe Japanese-Americans, language that reveals bias or an outdated perspective, or sensationalism) that provide insight about contemporary attitudes • the type of sources for the article (for example, does the article rely exclusively on government sources? Does it include any Japanese-American voices?)

Here’s one example to share with the class:

Headline: “ West Coast Widens Martial Law Call ” (PDF) Date: Feb. 12, 1942 Newspaper: The New York Times Explicit reason provided in the article: Raids on Japanese communities yielded large quantities of contraband that “fifth columnists” might find useful. Clues within the writing: The subheadline is startling: “FBI Raids Net 38 Japanese, Guns, Radios, Ammunition and Signal Devices.” It suggests that the Japanese-Americans involved might indeed be guilty of planning an act of treachery. But information at the end of the article explains that the contraband items were seized from a sporting goods store “operated by an alien Japanese.” In this way, even ordinary activities and businesses can appear threatening if they are said to involve Japanese-Americans. Sourcing: Only government sources (including the Los Angeles mayor, the California attorney general and an Army lieutenant general) were provided.

Other Times articles:

Dec. 8, 1941: “ Japanese Seizure Ordered by Biddle ” Dec. 8, 1941: “ West Coast Acts for War Defense ” Jan. 4, 1942: “ Only 2,971 Enemy Aliens Are Held ; Rest of the 1,100,000 Being Watched Here Are Unmolested ” Jan. 29, 1942: “ West Coast Moves to Oust Japanese / Los Angeles ‘Permits’ Nipponese on City Payroll to Take Leaves of Absence ” Feb. 5, 1942: “ California Aliens Face Changed Way / Great Areas of the State to Be Affected by Restrictions or Forced Removals ” Feb. 3, 1942: “ Japanese Seized in Raid on Coast / Federal Agents Arrest 200 or More Aliens in Swoop on Island at Los Angeles ” Feb. 17, 1942: “ Air Bombs Seized in 25 Coast Raids / Japanese Uniforms and Secret Papers Also Taken, 12 Arrests in Sacramento Area ” Dec. 5, 1943: “ Four Japanese Held by FBI in Chicago / Three Had Been Decorated by Tokyo for Activities Here ”

Students can also compare reporting in The Times with accounts and editorials in newspapers on the West Coast, where most Japanese-Americans lived and anti-Japanese hysteria was particularly acute. Is there a noticeable difference in tone? Explain.

West Coast newspapers:

Articles in The San Francisco News (scroll down to find dozens of articles from the spring of 1942) Excerpts from Los Angeles Times editorials (contained within a recent editorial)

Primary Sources: Photographs

Japanese-americans imprisoned, but unbowed, during world war ii.

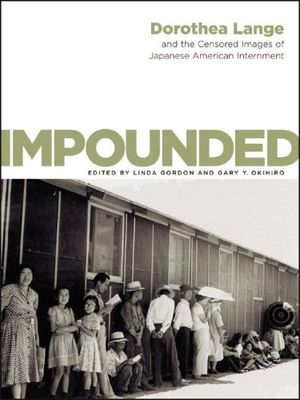

Background: Dorothea Lange, a photographer best known from her photographs of migrant farmers during the Great Depression, also documented the internment of Japanese-Americans.

Maurice Berger wrote in Lens :

At first glance, Dorothea Lange’s photographs of Japanese-Americans, taken in the early 1940s, appear to show ordinary activities. People wait patiently in lines. Children play. A woman makes artificial flowers. Storefront signs proudly proclaim, “I am an American.” But these quiet images document something sinister: the racially motivated relocation and internment during World War II of more than 110,000 people of Japanese ancestry who lived on the West Coast, more than 60 percent of whom were American citizens.

Activity: Look at images taken by Ms. Lange in this slide show (at the top of this page) as well as these photos . What do they reveal about the forced evacuation and internment of Japanese-Americans and about life in the camps?

Then imagine you are a museum curator with room for only five images to tell the story of internment. Which five images would you choose from the slide show? For each image, explain why.

Primary Sources: First-Person Video Interviews

A return to the internment camp, in an interview from may, bob fuchigami remembers the amache internment camp in colorado, where he was sent when he was 12 years old..

Background: Bob Fuchigami was sent to the Amache internment camp in Colorado with 10 family members when he was 12 years old. In this video , he returns to the camp at 85 to tell the story of his imprisonment.

And, in another video , Hiroshi Kashiwagi shares his memories of life at the Tule Lake internment camp.

Activity: While students watch one or both of these videos, invite them to consider the following: What can you learn about what internment was like for these people and their families? How did it affect their lives? What is the legacy of internment for them, and the nation, today?

Op-Eds That Connect the Past to the Present

Background: The actor George Takei, who was 5 years old when he and his family began their internment at Rohwer Japanese American Relocation Center in Arkansas, cautions America in his Op-Ed “ Internment, America’s Great Mistake ” to protect American values from “cynically manufactured fear and the deliberate targeting of a vulnerable minority.” He writes:

It has been the lifelong mission of many to ensure we remember the internment. Our oft-repeated plea is simple: We must understand and honor the past in order to learn from and not repeat it. But in the 75 years since President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 authorizing the internment of Japanese-Americans, never have we been more anxious that this mission might fail. It is imperative, in today’s toxic political environment, to acknowledge a hard truth: The horror of the internment lay in the racial animus the government itself propagated. It whipped up hatred and fear toward an entire group of people based solely on our ancestry.

And Karen Korematsu, whose father’s struggle against internment ended up being litigated before the Supreme Court , writes in her February 2017 Op-Ed, “ When Lies Overruled Rights ,” that Americans should “come together to reject discrimination based on religion, race or national origin, and to oppose the mass deportation of people who look or pray differently from the majority of Americans.”

Activity: Read these Opinion pieces and consider the arguments being made. Then, write your own Op-Ed using the history of Japanese internment to argue a position on an important issue today. Do you see any echoes of history in today’s current events?

Ideas for Further Research

Research life at the camps using 1940s reporting

Background: Newspaper reporting from the 1940s can provide a window into what life was like at internment camps. Anne O’Hare McCormick, a Times reporter, visited the Gila River War Relocation Center in Arizona. She wrote in a January 1944 article (PDF):

Most of all the settlement looks like an oasis in an endless desert of sand, sage, mesquite and giant cacti. Around the double cluster of barracks that serve as houses, schools, workshops, mess halls, cooperative stores, offices and hospitals are nearly 17,000 acres of vegetable gardens, wheat, alfalfa and rice fields and pasture lands startlingly neat and green in a framework of shallow irrigation ditches.

And a March 1943 Times article reported on white women performing “spartan” duty (PDF), working as teachers, nurses and secretaries at Tule Lake. But The Times did not publish many articles detailing what life was like in the camps.

Providing valuable perspective, by including voices often left out of the history books, are the newspapers published by Japanese-Americans imprisoned in the camps, such as The Heart Mountain Sentinel , The Tulean Dispatch from Tule Lake, The Denson Tribune of the Jerome camp in Arkansas, The Minidoka Irrigator from the Minidoka camp in Idaho and The Manzanar Free Press produced at Manzanar. (After opening each link, scroll down to view the headlines.)

Activity: Compare the reporting in The Times and other mainstream newspapers from 1942 to 1945 with the articles in papers published by Japanese internees. Think about how these on-the-scene reports add to an understanding about life in the internment camps. Consider these questions:

1. What can we learn from reading about life at the camps in newspaper articles published from 1942 to 1945? 2. What are the ways the news stories in the camp newspapers, published by Japanese internees, differ from reporting in The Times and other mainstream newspapers? 3. How can we evaluate the reliability of these various accounts?

Japanese-American soldiers

Background: While thousands were sent to internment camps, American-born Japanese were eventually deemed eligible to serve in World War II and thus prove their loyalty to the United States as well as provide needed troops for its war effort. The 442d Regimental Combat Team, a segregated unit comprised only of Japanese-Americans troops, became one of the most highly decorated regiments in U.S. military history, as the Times reported:

The 442d suffered huge casualties; Capt. Daniel K. Inouye, now a United States senator from Hawaii, lost his right arm in battle. The team became famous for its rescue of the Texan “Lost Battalion,” saving more than 200 men who had been surrounded by German troops.

Yet after serving in the Army, many Japanese-American soldiers who returned to America faced discrimination . Senator Daniel Inouye, who died in 2012, recounted for a PBS documentary how after returning from battle in Europe and seeking a haircut while in uniform, he was told, “We don’t cut Jap hair.”

In 2000 President Bill Clinton awarded the Medal of Honor to 22 Asian-Americans; 20 were Japanese-Americans . When George T. Sakato died in 2015, he was the last to die of seven Japan-Americans who had lived to receive this honor. In 2011 Congress granted several Japanese-American veterans Congressional Gold Medals .

Activity: Consider whether serving in the military would have been easy or hard to do when the rest of your family was kept in an internment camp. Then write a frank one-page letter home to your family as a Japanese-American soldier.

Legal challenges to the camps

Background: After Fred T. Korematsu in 1942 defied his military evacuation order, the American Civil Liberties Union branch in Northern California took up his case . But he lost his appeal and the Supreme Court ruled against him in 1944. Gordon Hirabayashi and Minoru Yasui also separately defied their curfew orders and refused to report for internment, resulting in legal challenges that the Supreme Court rejected.

The 1942 legal challenge by Mitsuye Endo (PDF) that also landed in the Supreme Court is credited by some as leading to President Roosevelt’s 1944 suspension of Executive Order 9066 , as a law professor detailed a 2016 Sacramento Bee opinion piece.

In 1981, after the historian Peter Irons requested legal documents from Fred Korematsu’s 1940s Supreme Court case, he found a memo indicating that “a government lawyer had accused the solicitor general of lying to the Supreme Court about the danger posed by Japanese-Americans.” Mr. Irons convinced Mr. Korematsu to challenge the ruling. Karen Korematsu, Mr. Korematsu’s daughter, later wrote in The Times :

Evidence was discovered proving that the wartime government suppressed, altered and destroyed material evidence while arguing my father’s, Yasui’s and Hirabayashi’s cases before the Supreme Court. The government’s claims that people of Japanese descent had engaged in espionage and that mass incarceration was necessary to protect the country were not only false, but had even been refuted by the government’s own agencies, including the Office of Naval Intelligence, the F.B.I. and the Federal Communications Commission.

In 1983 a judge overturned Mr. Korematsu’s conviction , “based on newly obtained information revealing that the government had knowingly exaggerated the threat of sabotage and espionage posed by ethnic Japanese on the West Coast.” And in 1998, President Clinton gave Mr. Korematsu the Medal of Freedom .

Activity: Choose any of these court cases related to Japanese internment to research further. What is the background of the case? What were the legal issues involved? What did the court decide? What is the significance of that decision?

Investigating the camps and reparations

Background: In the 1980s Congress initiated an investigation of the internment camps. The hearings of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, some 40 years after the war, produced a report in 1983, concluding that the relocation and internment of Japanese-American citizens and resident aliens in World War II amounted to a “grave injustice.” Five years later, President Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 , which granted reparations to Japanese-Americans who had been interned by the United States government during the war.

To locate potential recipients of the reparations, the Justice Department created the Office of Redress Administration; but the process of tracking down eligible people was laborious and time-consuming , and former internees were dying . In September 1989 the Senate tried to speed up the process , yet more wrangling resulted, with the checks not to be sent until funds were made available in late in 1990 . By 1992, only 50,000 people had been paid.

Activity: Students should read about the conclusions of the 1983 report and discuss the following: What are the most striking points? Did Congress and the president make the right decision in issuing apologies and paying reparations?

Now imagine having President Roosevelt’s ear at a reception in 1942 for 10 minutes. What should he be told about the role that Japanese internment camps have played in American history?

Remembering the camps

Seeking Answers at Tule Lake Internment Camp

Background: In 2006 Congress sent President George W. Bush legislation (which he signed ) to preserve the internment camps . Two camps are now National Park Service sites: the Manzanar National Historic Site and the Minidoka Internment National Monument (created by President Clinton’s 2001 order ).

Activity: Students can do this exercise on their own: Consider whether an internment camp would be the type of place you’d like to visit and list your reasons. Whatever your response, do research online about a camp and in your own words create a one-page summary of a tour that could be given there. Or create a museum gallery for the historic site.

Alternately, write an Op-Ed about whether more or less should be done to preserve these sites for the future.

Invoking the internment example

Background: It’s possible to find echoes of the Japanese internment controversy in national security debates at other moments of United States history since World War II. Even though the official government attitude toward Japanese internment gradually changed, not all Americans are in agreement. Explore the following recent incidents when political leaders and activists raised the Japanese internment experience as a chapter to repeat or to avoid:

1. The aftermath of 9/11: After the Sept. 11 attacks, Japanese-Americans voiced concern about bigotry against American Muslims and Sikhs. In 2004, an advisory panel criticized the Census Bureau’s move to give the Department of Homeland Security data that identified populations of Arab-Americans; critics compared the bureau’s 21st-century actions to its World War II activities locating Japanese-American communities. (A 2000 Times article highlighted research concluding that the Census Bureau, despite its denials, had indeed been highly involved in the roundup and internment of Japanese-Americans.)

In 2007 Holly Yasui filed a legal brief to aid Muslim immigrants who sought to overturn a Brooklyn judge’s ruling allowing for the detention of noncitizens; Ms. Yasui’s father, Minoru Yasui, had once challenged a Supreme Court ruling on World War II restrictions.

2. Refugees from Syria’s civil war: In November 2015, a Roanoke, Va., mayor caused a firestorm, explaining his opposition to welcoming Syrian refugees to the U.S., saying the internment of Japanese-Americans had been justified . Then he recanted. For some former Japanese internees, the debate over Syria’s refugees has evoked painful memories .

3. Restrictions on immigration by Muslims: On Dec. 9, 2015, The Times reported on an MSNBC interview of Donald J. Trump, then a presidential candidate:

Mr. Trump cited Roosevelt’s classification of thousands of Japanese, Germans and Italians living in the United States during the war as “enemy aliens.” He said he was not endorsing something as drastic as the camps where American citizens of Japanese descent were interned. Instead, he referred to three proclamations by which Roosevelt authorized government detention of immigrants, and which led to the internment of thousands of noncitizen Japanese, Germans and Italians.

A few days later Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt’s granddaughter roundly rejected Mr. Trump’s ideas, as did Representative Doris Matsui , who had been interned in a camp. A 16-year-old student wrote a contest-winning essay for The Learning Network connecting the internment of ethnic Japanese with excluding Muslims from immigrating to America.

Shortly after his election in November 2016, Mr. Trump reaffirmed his intention to restrict immigration by Muslims. A Trump supporter, Carl Higbie , evoked the “precedent” of the Japanese internment camps in citing the need to prevent homeland terrorism in a Fox News appearance.

Promptly following his inauguration, President Trump issued a series of executive orders to limit immigration or travel to the United States by people from seven countries with largely Muslim populations. Legal challenges followed, but in September Mr. Trump responded by imposing a more sweeping ban ; a judge halted it in October. Earlier this week the Supreme Court permitted the travel ban to go forward even while legal challenges continue.

Activity: Students can select one of the above examples from the past two decades when political leaders or activists have invoked the legacy of the Japanese internment and determine the following: What are the relevant lessons from the Japanese internment experience that should inform this situation? Explain.

Additional Resources

Digital Public Library of America | Teaching Guide: Exploring Japanese American Internment During World War II and Japanese American Internment During World War II Primary Source Set

Densho | Teaching WWII Japanese American Incarceration With Primary Sources

Digital History | Explorations: Japanese-American Internment FDR Presidential Library and Museum | Japanese American Internment

News alert: UC Berkeley has announced its next university librarian

Secondary menu

- Log in to your Library account

- Hours and Maps

- Connect from Off Campus

- UC Berkeley Home

Search form

Japanese american internment - research guide, getting started, finding background information, off-campus access to library resources.

- Books/Media

- Articles - Secondary Sources

- Primary Sources

- Bancroft Library

- Research Help

1. Use reference sources (see below) to learn basic facts about your topic, including dates, places, names of individuals and organizations, titles of specific publications, etc.

2. Find and read secondary sources (see Books/Media tab for sample searches to use in UC Library Search and the Articles tab for examples of searches to use in the America: History and Life database).

Make sure you look through the bibliographies of secondary sources, which can lead you to other secondary sources and to primary sources.

3. Search for primary sources (see Primary Sources tab).

More about the writing of papers:

- The Craft of Research (e-book)

This classic book on writing a college research paper is easily skimmed or deep enough for the truly obsessed researcher, explains the whole research process from initial questioning, through making an argument, all the way to effectively writing your paper.

Reading, Writing, and Researching for History: A Guide for College Students Professor Patrick Rael [a Berkeley PhD] has written a comprehensive but easy to skim web guide to writing history papers. Recommended by History Dept faculty.

There are two ways to connect to library resources from off-campus using the new library proxy:

- Links to online resources on library websites, such as UC Library Search, will allow you to login with CalNet directly.

- To access library resources found via non-UCB sites, such as Google or Google Scholar, you can add the EZproxy bookmarklet to your browser. Then, whenever you land on a licensed library resource, select your EZproxy bookmarklet to enable CalNet login.

More information is on the EZproxy guide .

The campus VPN provides an alternate method for off-campus access.

- Next: Books/Media >>

- Last Updated: Apr 8, 2024 2:44 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/internment

Educator Resources

Japanese-American Incarceration During World War II

In his speech to Congress, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt declared that the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, was "a date which will live in infamy." The attack launched the United States fully into the two theaters of World War II – Europe and the Pacific. Prior to Pearl Harbor, the United States had been involved in a non-combat role, through the Lend-Lease Program that supplied England, China, Russia, and other anti-fascist countries of Europe with munitions.

The attack on Pearl Harbor also launched a rash of fear about national security, especially on the West Coast. In February 1942, just two months later, President Roosevelt, as commander-in-chief, issued Executive Order 9066 that resulted in the internment of Japanese Americans. The order authorized the Secretary of War and military commanders to evacuate all persons deemed a threat from the West Coast to internment camps, that the government called "relocation centers," further inland. Read more...

Primary Sources

Links go to DocsTeach , the online tool for teaching with documents from the National Archives.

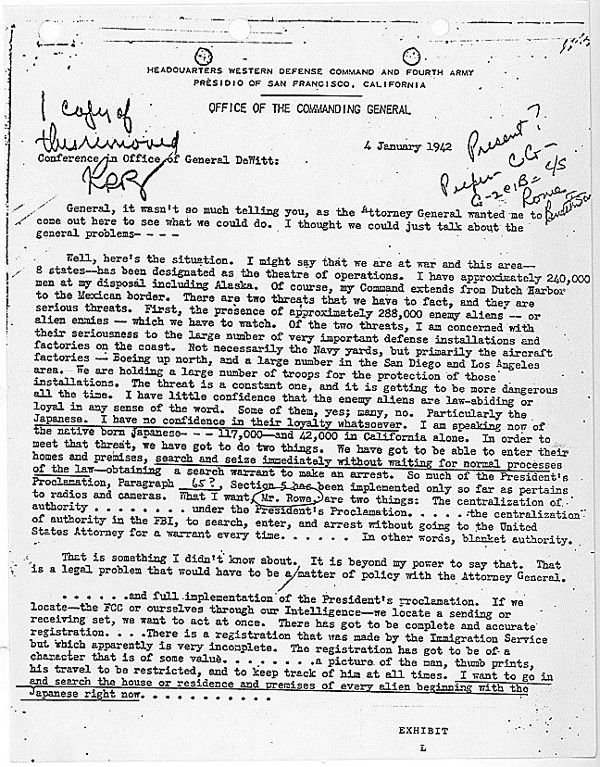

Meeting Between Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt and Representatives of the Department of Justice and the Army at the Office of Commanding General, Headquarters, Western Defense Command and Fourth Army, in San Francisco, 1/4/1942

Executive Order 9066 Issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, 2/19/1942

Posting of Exclusion Order in San Francisco, Directing Removal of Persons of Japanese Ancestry from the First Section in San Francisco to be Affected by the Evacuation, 4/11/1942

Thank You Note at the Iseri Drugstore in "Little Tokyo" in Los Angeles, California, 4/11/1942

Merchandise Sale in San Francisco, California, Where Customers Buy Goods Prior to Evacuation and Internment, 4/4/1942

Children Pledge Allegiance to the Flag in San Francisco, California, at Raphael Weill Public School, 4/20/1942

The Shibuya Family at Their Home in Mountain View, California, Before Being Sent to Heart Mountain Relocation Center in Wyoming Days Later, 4/18/1942

Ranch Superintendent Henry Futamachi (Left) Discusses Agriculture with Ranch Owner John MacKinley Before Evacuation and Internment, 4/10/1942

Dave Tatsuno Reading to His Son and Packing His Possessions Prior to Evacuation and Internment, 4/13/1942

Residents of Japanese Ancestry File Forms in San Francisco, Two Days Before Evacuation and Internment, 4/4/1942

Residents of Japanese Ancestry, With Baggage Stacked, Waiting for a Bus to be Evacuated at the Wartime Civil Control Administration in San Francisco, 4/6/1942

Japanese Family Heads and Persons Living Alone Line up for "Processing" in Response to Civilian Exclusion Order Number 20, 4/25/1942

Baggage Being Sorted and Trucked to Owners in Their Barracks at the Minidoka Internment Camp in Eden, Idaho, 8/17/1942

Registering and Assigning Barracks to the Newly Arrived at Minidoka Internment Camp in Eden, Idaho, 8/17/1942

The Hirano Family Posing with a Photograph of a United States Serviceman at the Colorado River Internment Camp in Poston, Arizona

High School Campus at Heart Mountain Internment Camp in Wyoming — Classes are Held in Tarpaper-covered, Barrack-style Buildings, 6/1943

The Poster Crew at Heart Mountain Internment Camp in Wyoming, Making Fire and Safety Posters, Announcements for Public Gatherings and Dances, and General Instructions, 9/14/1942

Court Session at Heart Mountain Internment Camp in Wyoming, Presiding Over Infractions of Camp Regulations and Civil Court Cases, 6/4/1943

Coal Crew at Heart Mountain Internment Camp in Wyoming, Providing Heat for Residents During Cold Winter Months, 9/15/1942

Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942 – Written by General DeWitt, who Oversaw the Internment of Japanese-Americans, Providing a Favorable Overview of the "Evacuation Program"

This 10-minute film clip called "Japanese-Americans" (1945) comes from Army-Navy Screen Magazine , a biweekly film series for servicemen during World War II. It highlights the 100th Infantry Battalion, composed largely of Japanese-Americans.

This video clip shows President Ronald Reagan Giving Remarks and Signing the Japanese-American Internment Compensation Bill, 8/10/1988

Teaching Activity

In Japanese American Incarceration During World War II on DocsTeach students analyze a variety of documents and photographs to learn how the government justified the forced relocation and incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II, and how civil liberties were denied.

Additional Background Information

Prior to the outbreak of World War II, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) had identified German, Italian, and Japanese aliens who were suspected of being potential enemy agents; and they were kept under surveillance. Following the attack at Pearl Harbor, government suspicion arose not only around aliens who came from enemy nations, but around all persons of Japanese descent, whether foreign born ( issei ) or American citizens ( nisei ). During congressional committee hearings, representatives of the Department of Justice raised logistical, constitutional, and ethical objections. Regardless, the task was turned over to the U.S. Army as a security matter.

The entire West Coast was deemed a military area and was divided into military zones. Executive Order 9066 authorized military commanders to exclude civilians from military areas. Although the language of the order did not specify any ethnic group, Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt of the Western Defense Command proceeded to announce curfews that included only Japanese Americans. Next, he encouraged voluntary evacuation by Japanese Americans from a limited number of areas; about seven percent of the total Japanese American population in these areas complied.

On March 29, 1942, under the authority of the executive order, DeWitt issued Public Proclamation No. 4, which began the forced evacuation and detention of Japanese-American West Coast residents on a 48-hour notice. Only a few days prior to the proclamation, on March 21, Congress had passed Public Law 503, which made violation of Executive Order 9066 a misdemeanor punishable by up to one year in prison and a $5,000 fine.

Because of the perception of "public danger," all Japanese Americans within varied distances from the Pacific coast were targeted. Unless they were able to dispose of or make arrangements for care of their property within a few days, their homes, farms, businesses, and most of their private belongings were lost forever.

From the end of March to August, approximately 112,000 persons were sent to "assembly centers" – often racetracks or fairgrounds – where they waited and were tagged to indicate the location of a long-term "relocation center" that would be their home for the rest of the war. Nearly 70,000 of the evacuees were American citizens. There were no charges of disloyalty against any of these citizens, nor was there any vehicle by which they could appeal their loss of property and personal liberty.

"Relocation centers" were situated many miles inland, often in remote and desolate locales. Sites included Tule Lake and Manzanar in California; Gila River and Poston in Arizona; Jerome and Rohwer in Arkansas, Minidoka in Idaho; Topaz in Utah; Heart Mountain in Wyoming; and Granada in Colorado. (Incarceration rates were significantly lower in the territory of Hawaii, where Japanese Americans made up over one-third of the population and their labor was needed to sustain the economy. However, martial law had been declared in Hawaii immediately following the Pearl Harbor attack, and the Army issued hundreds of military orders, some applicable only to persons of Japanese ancestry.)

In the "relocation centers" (also called "internment camps"), four or five families, with their sparse collections of clothing and possessions, shared tar-papered army-style barracks. Most lived in these conditions for nearly three years or more until the end of the war. Gradually some insulation was added to the barracks and lightweight partitions were added to make them a little more comfortable and somewhat private. Life took on some familiar routines of socializing and school. However, eating in common facilities, using shared restrooms, and having limited opportunities for work interrupted other social and cultural patterns. Persons who resisted were sent to a special camp at Tule Lake, CA, where dissidents were housed.

In 1943 and 1944, the government assembled a combat unit of Japanese Americans for the European theater. It became the 442d Regimental Combat Team and gained fame as the most highly decorated of World War II. Their military record bespoke their patriotism.

As the war drew to a close, "internment camps" were slowly evacuated. While some persons of Japanese ancestry returned to their hometowns, others sought new surroundings. For example, the Japanese-American community of Tacoma, WA, had been sent to three different centers; only 30 percent returned to Tacoma after the war. Japanese Americans from Fresno had gone to Manzanar; 80 percent returned to their hometown.

The internment of Japanese Americans during World War II sparked constitutional and political debate. During this period, three Japanese-American citizens challenged the constitutionality of the forced relocation and curfew orders through legal actions: Gordon Hirabayashi, Fred Korematsu, and Mitsuye Endo. Hirabayashi and Korematsu received negative judgments; but Mitsuye Endo, after a lengthy battle through lesser courts, was determined to be "loyal" and allowed to leave the Topaz, Utah, facility.

Justice Murphy of the Supreme Court expressed the following opinion in Ex parte Mitsuye Endo :

I join in the opinion of the Court, but I am of the view that detention in Relocation Centers of persons of Japanese ancestry regardless of loyalty is not only unauthorized by Congress or the Executive but is another example of the unconstitutional resort to racism inherent in the entire evacuation program. As stated more fully in my dissenting opinion in Fred Toyosaburo Korematsu v. United States , 323 U.S. 214 , 65 S.Ct. 193, racial discrimination of this nature bears no reasonable relation to military necessity and is utterly foreign to the ideals and traditions of the American people.

In 1988, Congress passed, and President Reagan signed, Public Law 100-383 – the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 – that acknowledged the injustice of "internment," apologized for it, and provided a $20,000 cash payment to each person who was incarcerated.

One of the most stunning ironies in this episode of denied civil liberties was articulated by an internee who, when told that Japanese Americans were put in those camps for their own protection, countered "If we were put there for our protection, why were the guns at the guard towers pointed inward, instead of outward?"

A note on terminology: The historical primary source documents included on this page reflect the terminology that the government used at the time, such as alien , evacuation , relocation , relocation centers , internment , and Japanese (as opposed to Japanese American ).

Home — Essay Samples — History — American History — Japanese Internment Camps: Tragedy and Injustice

Japanese Internment Camps: Tragedy and Injustice

- Categories: American History

About this sample

Words: 749 |

Published: Sep 1, 2023

Words: 749 | Pages: 2 | 4 min read

Table of contents

Historical context: fear and paranoia, experiences in internment camps: resilience amid adversity, enduring impact on communities: seeking justice, lessons for the present and future, conclusion: remembering the past, shaping a just future.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Karlyna PhD

Verified writer

- Expert in: History

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 1123 words

3 pages / 1356 words

1 pages / 609 words

6 pages / 2599 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on American History

The pivotal and transformative event that was the Battle of Yorktown occupies an eminent position in American history, bringing an end to a war that had exhausted both the American and British forces. The battle, which unfolded [...]

The term "hyphenated American" has been used for over a century to describe individuals in the United States who identify with both their ancestral or ethnic heritage and their American nationality. It's a label that has [...]

The American Revolution, a pivotal event in world history, marked the birth of the United States as an independent nation. It was a time of great turmoil, with colonists rebelling against British rule and fighting for their [...]

The Stamp Act of 1765 is a landmark event in American history that played a crucial role in shaping the nation's path toward independence. This essay explores the historical context, significance, and consequences of the Stamp [...]

Shortly after the horrific events of Pearl Harbor on December 7th, 1941, the lives of hundreds of thousands of ethnic Japenese people, both aliens and Citizens of the United States, would be changed in some major ways. Executive [...]