An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Iran J Med Sci

- v.45(4); 2020 Jul

A Narrative Review of COVID-19: The New Pandemic Disease

Kiana shirani, md.

1 Infectious Diseases and Tropical Medicine Research Center, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran

Erfan Sheikhbahaei, MD

2 Student Research Committee, School of Medicine, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran

Zahra Torkpour, MD

Mazyar ghadiri nejad, phd.

3 Industrial Engineering Department, Girne American University, Kyrenia, TRNC, Turkey

Bahareh Kamyab Moghadas, PhD

4 Department of Chemical Engineering, Shiraz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Shiraz, Iran

Matina Ghasemi, PhD

5 Faculty of Business and Economics, Business Department, Girne American University, Kyrenia, TRNC, Turkey

Hossein Akbari Aghdam, MD

6 Department of Orthopedic Surgery, School of Medicine, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran

Athena Ehsani, PhD

7 Department of Biomedical Engineering, Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran

Saeed Saber-Samandari, PhD

8 New Technologies Research Center, Amirkabir University of Technology, Tehran, Iran

Amirsalar Khandan, PhD

9 Department of Electrical Engineering, Isfahan (Khorasgan) Branch, Islamic Azad University, Isfahan, Iran

10 0Technology Incubator Center, Isfahan (Khorasgan) Branch, Islamic Azad University, Isfahan, Iran

Nearly every 100 years, humans collectively face a pandemic crisis. After the Spanish flu, now the world is in the grip of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). First detected in 2019 in the Chinese city of Wuhan, COVID-19 causes severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. Despite the initial evidence indicating a zoonotic origin, the contagion is now known to primarily spread from person to person through respiratory droplets. The precautionary measures recommended by the scientific community to halt the fast transmission of the disease failed to prevent this contagious disease from becoming a pandemic for a whole host of reasons. After an incubation period of about two days to two weeks, a spectrum of clinical manifestations can be seen in individuals afflicted by COVID-19: from an asymptomatic condition that can spread the virus in the environment, to a mild/moderate disease with cold/flu-like symptoms, to deteriorated conditions that need hospitalization and intensive care unit management, and then a fatal respiratory distress syndrome that becomes refractory to oxygenation. Several diagnostic modalities have been advocated and evaluated; however, in some cases, diagnosis is made on the clinical picture in order not to lose time. A consensus on what constitutes special treatment for COVID-19 has yet to emerge. Alongside conservative and supportive care, some potential drugs have been recommended and a considerable number of investigations are ongoing in this regard

What’s Known

- Substantial numbers of articles on COVID-19 have been published, yet there is controversy among clinicians and confusion among the general population in this regard. Furthermore, it is unreasonable to expect physicians to read all the available literature on this subject.

What’s New

- This article reviews high-quality articles on COVID-19 and effectively summarizes them for healthcare providers and the general population.

Introduction

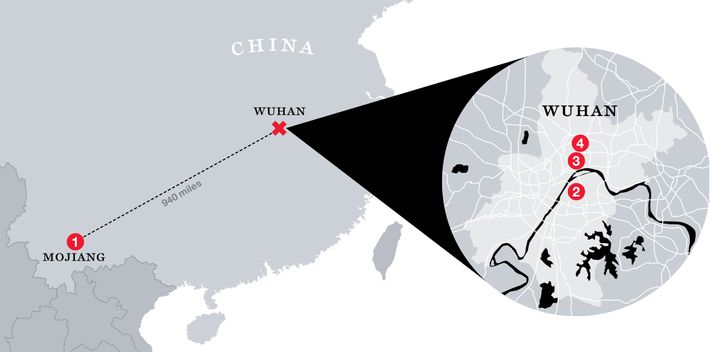

A pathogen from a human-animal virus family, the coronavirus (CoV), which was identified as the main cause of respiratory tract infections, evolved to a novel and wild kind in Wuhan, a city in Hubei Province of China, and spread throughout the world, such that it created a pandemic crisis according to the World Health Organization (WHO). CoV is a large family of viruses that were first discovered in 1960. These viruses cause such diseases as common colds in humans and animals. Sometimes they attack the respiratory system, and sometimes their signs appear in the gastrointestinal tract. There have been different types of human CoV including CoV-229E, CoV-OC43, CoV-NL63, and CoV-HKU1, with the latter two having been discovered in 2004 and 2005, respectively. These types of CoV regularly cause respiratory infections in children and adults. 1 There are also other types of these viruses that are associated with more severe symptoms. The new CoV, scientifically known as “SARS-CoV-2”, causes severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). 2 A newer type of the virus was discovered in September 2012 in a 60-year-old man in Saudi Arabia who died of the disease; the man had traveled to Dubai a few days earlier. The second case was a 49-year-old man in Qatar who also passed away. The discovery was first confirmed at the Health Protection Agency’s Laboratory in Colindale, London. The outbreak of this CoV is known as the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), commonly referred to as “MERS-CoV”. The virus has infected 2260 people and has killed 912, most of them in the Middle East. 3 - 5 Finally, in December 2019, for the first time in Wuhan, in Hubei Province of China, a new type of CoV was identified that caused pneumonia in humans. 6 SARS-CoV-2 has affected 5404512 people and killed more than 343514 around the world according to the WHO situation report-127 (May 26, 2020). 3 , 7 - 10 The WHO has officially termed the disease “COVID-19”, which refers to corona, the virus, the disease, the year 2019, and its etiology (SARS-CoV-2). This type of CoV had never been seen in humans before. The initial estimates showed a mortality rate ranging from between 1% and 3% in most countries to 5% in the worst-hit areas ( Figure 1 ). 9 Some Chinese researchers succeeded in determining how SARS-CoV-2 affects human cells, which could help to develop techniques of viral detection and had antiviral therapy potential. Via a process termed “cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM)”, these scientists discovered that CoV enters human cells utilizing a kind of cell membrane glycoprotein: angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2). Then, the S protein is split into two sub-units: S1 and S2. S1 keeps a receptor-binding domain (RBD); accordingly, SARS-CoV-2 can bind to the peptidase domain of ACE2 directly. It appears that S2 subsequently plays a role in cellular fusion. Chinese researchers used the cryo-EM technique to provide ACE2 when it is linked to an amino acid transporter called “B0AT1”. They also discovered how to connect SARS-CoV-2 to ACE2-B0AT1, which is another complex structure. Given that none of these molecular structures was previously known, the researchers hoped that these studies would lead to the development of an antiviral or vaccine that would help to prevent CoV. Along the way, scientists found that ACE2 has to undergo a molecular process in which it binds to another molecule to be activated. The resulting molecule can bind two SARS-CoV-2 protein molecules simultaneously. The scientists also studied different SARS-CoV-2 RBD binding methods compared with other SARS-CoV-RBDs, which showed how subtle changes in the molecular binding sequence make the coronal structure of the virus stronger.

Most cases with SARS-CoV-2 are asymptomatic or have mild clinical pictures such as influenza and colds. This group of patients should be detected and isolated in their homes to break the transmission chain of the disease and adhere to the precautionary recommendations in order not to infect other people. The screening process will help this group and suppress the outbreak in the community. Patients with the confirmed disease who are admitted to hospitals can contaminate this environment, which should be borne in mind by healthcare providers and policymakers.

Transmission

While the first mode of the transmission of COVID-19 to humans is still unknown, a seafood market where live animals were sold was identified as a potential source at the beginning of the outbreak in the epidemiologic investigations that found some infected patients who had visited or worked in that place. The other viruses in this family, namely MERS and SARS, were both confirmed to be zoonotic viruses. Afterward, the person-to-person spread was established as the main mode of transmission and the reason for the progression of the outbreak. 11 Similar to the influenza virus, SARS-CoV-2 spreads through the population via respiratory droplets. When an infected person coughs, sneezes, or talks, the respiratory secretions, which contain the virus, enter the environment as droplets. These droplets can reach the mucous membranes of individuals directly or indirectly when they touch an infected surface or any other source; the virus, thereafter, finds its ways to the eyes, nose, or mouth as the first incubation places. 11 - 15 It has been reported that droplets cannot travel more than two meters in the air, nor can they remain in the air owing to their high density. Nonetheless, given the other hitherto unknown modes of transmission, routine airborne transmission precautions should be considered in high-risk countries and during high-risk procedures such as manual ventilation with bags and masks, endotracheal intubation, open endotracheal suctioning, bronchoscopy, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, sputum induction, lung surgery, nebulizer therapy, noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (eg, bilevel positive airway pressure and continuous positive airway pressure ), and lung autopsy. In the early stages of the disease, the chances of the spread of the virus to other persons are high because the viral load in the body may be high despite the absence of any symptoms ( Figure 2 ). 11 - 13 The person-to-person transmission rates can be different depending on the location and the infection control intervention; still, according to the latest reports, the secondary COVID-19 infection rate ranges from 1% to 5%. 13 - 23 Although the RNA of the virus has been detected in blood and stool, fecal-oral and blood-borne transmissions are not regarded as significant modes of transmission yet. 19 - 26 There have been no reports of mother-to-fetus transmission in pregnant women. 27

SARS-CoV-2 mode of transmission and clinical manifestations are illustrated in this figure. The potential source of this outbreak was identified to be from animals, similar to MERS and SARS, in epidemiologic studies; nonetheless, person-to-person transmission through droplets is currently the important mode. After reaching mucous membranes by direct or indirect close contact, the virus replicates in the cells and the immune system attacks the body due to its nature. Afterward, the clinical pictures appear, which are much more similar to influenza. However, different patients will have a spectrum of signs and symptoms.

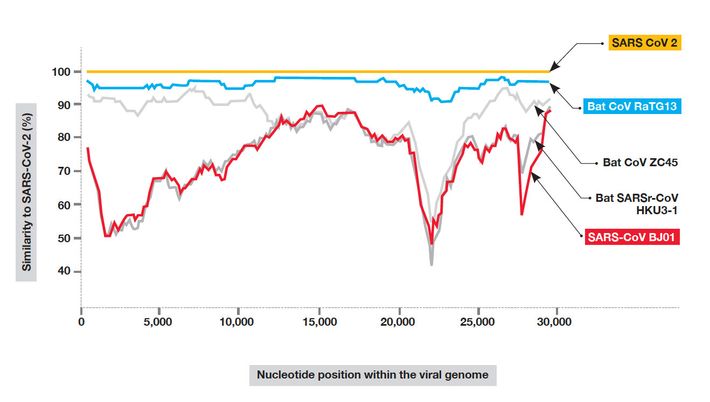

Source Investigation

Recently, the appearance of SARS-CoV-2 in society shocked the healthcare system. 28 - 32 Veterinary corona virologists reported that COVID-19 was isolated from wildlife. Several studies have shown that bats are receptors of the CoV new version in 2019 with variants and changes in the environment featuring various biological characteristics. 33 - 36 The aforementioned mammals are a major source of CoV, which causes mild-to-severe respiratory illness and can even be deadly. In recent years, the virus has killed several thousands of people of all ages. 37 - 39 The mutated alternative of the virus can be transmitted to humans and cause acute respiratory distress. 40 , 41 One of the main causes of the spread of the virus is the exotic and unusual Chinese food in Wuhan: CoV is a direct result of the Chinese food cycle. The virus is found in the body of animals such as bats, 42 and snake or bat soup is a favorite Chinese food. Therefore, this sequence is replicated continuously. Almost everyone who was infected for the first time was directly in the local Wuhan market or had indirectly tried snake or bat soup in a Chinese restaurant. An investigation stated that the Malayan pangolin (Manis javanica) was a possible host for SARS-CoV-2 and recommended that it be removed from the wet market to prevent zoonotic transmissions in the future. 43 , 44

Pathogenesis

The important mechanisms of the severe pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 are not fully understood. Extensive lung injury in SARS-CoV-2 has been related to increased virus titers; monocyte, macrophage, and neutrophil infiltrations into the lungs; and elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Thus, the clinical exacerbation of SARS-CoV-2 infection may be in consequence of a combination of direct virus-induced cytopathic and immunopathological effects due to excessive cytokinesis. Changes in the cytokine/chemokine profile during SARS infection showed increased levels of circulating cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), C–X–C motif chemokine 10 (CXCL10), interleukin (IL)-6, and IL-8 levels, in conjunction with elevated levels of serum pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1, IL-6, IL-12, interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β). Nevertheless, constant stimulation by the virus creates a cytokine storm that has been related to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and multiple organ dysfunction syndromes (MODS) in patients with COVID-19, which may ultimately lead to diminished immunity by lowering the number of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and natural killer cells (crucial in antiviral immunity) and decreasing cytokine production and functional ability (exhaustion). It has been shown that IL-10, an inhibitory cytokine, is a major player and a potential target for therapeutic aims. 45 - 51 Severe cases of COVID-19 have respiratory distress and failure, which has been linked to the altered metabolism of heme by SARS-CoV-2. Some virus proteins can dissociate iron from porphyrins by attacking the 1-β chain of hemoglobin, which decreases the oxygen-transferring ability of hemoglobin. Research has also indicated that chloroquine and favipiravir might inhibit this process. 52

Clinical Manifestations

SARS-CoV-2, which attacks the respiratory system, has a spectrum of manifestations; nonetheless, it has three main primary symptoms after an incubation period of about two days to two weeks: fever and its associated symptoms such as malaise/fatigue/weakness; cough, which is nonproductive in most of the cases but can be productive indeed; and shortness of breath (dyspnea) due to low blood oxygenation. Although these symptoms appear in the body of the affected person over two to 14 days, patients may refer to the clinic with gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea/vomiting-diarrhea) or decreased sense of smell and/or taste. More devastatingly, however, patients may refer to the emergency room with such coagulopathies as pulmonary thromboembolism, cerebral venous thrombosis, and other related manifestations. The WHO has stated that dry throat and dry cough are other symptoms detected in the early stages of the infection. 53 , 54 The estimations of the severity of the disease are as follows: mild (no or mild pneumonia) in 81%, severe (eg, with dyspnea, hypoxia, or >50% lung involvement on imaging within 24 to 48 hours) in 14%, and critical (eg, with respiratory failure, shock, or multiorgan dysfunction) in 5%. In the early stages, the overall mortality rate was 2.3% and no deaths were observed in non-severe patients. Patients with advanced age or underlying medical comorbidities have more mortality and morbidity. 55 Although adults of middle age and older are most commonly affected by SARS-CoV-2, individuals at any age can be infected. A few studies have reported symptomatic infection in children; still, when it occurs, it has mild symptoms. The vast majority of cases have the infection with no signs and symptoms or mild clinical pictures; they are called “the asymptomatic group”. These patients do not seek medical care and if they come into close contact with others, they can spread the virus. Therefore, quarantine in their home is the best option for the population to break the transmission of the virus. It should be considered that some of these asymptomatic patients have clinical signs such as chest computed tomography scan (CT-Scan) infiltrations. Similar to bacterial pneumonia, lower respiratory signs and symptoms are the most frequent manifestations in serious cases of COVID-19, characterized by fever, cough, dyspnea, and bilateral infiltrates on chest imaging. In a study describing pneumonia in Wuhan, the most common clinical signs and symptoms at the onset of the illness were fever in 99% (although fever might not be a universal finding), fatigue in 70%, dry cough in 59%, anorexia in 40%, myalgia in 35%, dyspnea in 31%, and sputum production in 27%. Headache, sore throat, and rhinorrhea are less common, and gastrointestinal symptoms (eg, nausea and diarrhea) are relatively rare. 7 , 42 , 43 , 45 - 48 , 56 , 57 According to our clinical experience in Iran, anosmia, atypical chest pain, diarrhea, nausea/vomiting, and hemoptysis are other presenting symptoms in the clinic. It should be noted that COVID-19 has some unexplained potential complications such as secondary bacterial infections, myocarditis, central nervous system injury, cerebral edema, MODS, acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis (ADEM), kidney injury, liver injury, new-onset seizure, coagulopathy, and arrhythmias.

Laboratory data : Complete blood counts, which constitute a routine laboratory test, have shown different results in terms of the white blood cell count: from leukopenia and lymphopenia to leukocytosis, although lymphopenia appears to be the most common. Fatal cases have exhibited severe lymphopenia accompanied by an increased level of D-dimer. Liver function enzymes can be increased; however, it is not sufficient to diagnose a disease. The serum procalcitonin level is a marker of infection, especially in bacterial diseases. Patients with COVID-19 who require intensive care unit (ICU) management may have elevated procalcitonin. Increased urea and creatinine, creatinine-phosphokinase, lactate dehydrogenase, and C-reactive protein are other findings in some cases. 7 , 56 , 57

Imaging studies : Routine chest X-ray (CXR) is widely deemed the first-step management to evaluate any respiratory involvement. Although negative findings in CXR do not rule out the viral disease, patients without common findings do not have severe disease and can, consequently, be managed in the outpatient setting. 58 , 59 Another modality is chest CT-Scan. It can be ordered in suspected cases with typical symptoms at the first step, or it can be performed after the detection of any abnormalities in CXR. The most common demonstrations in CT-Scan images are ground-glass opacification, round opacities, and crazy paving with or without bilateral consolidative abnormalities (multilobar involvement) in contrast to most cases of bacterial pneumonia, which have locally limited involvement. Pleural thickening, pleural effusion, and lymphadenopathy are less common. 58 - 61 Tree-in-bud, peribronchial distribution, nodules, and cavity are not in favor of common COVID-19 findings. Although reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) is used to confirm the diagnosis, it is a time-consuming procedure and has high false-negative/false-positive findings; hence, in the emergency clinical setting, CT-Scan findings can be a good approach to make the diagnosis. It is deserving of note, however, that false-positive/false-negative cases were reported by one study to be high and other differential diagnoses should be in mind in order not to miss any other cases such as acute pulmonary edema in patients with heart disease.

Suspected cases should be diagnosed as soon as possible to isolate and control the infection immediately. COVID-19 should be considered in any patient with fever and/or lower respiratory tract symptoms with any of the following risk factors in the previous 2 weeks: close contact with confirmed or suspected cases in any environment, especially at work in healthcare places without sufficient protective equipment or long-time standing in those places, and living in or traveling from well-known places where the disease is an epidemic. 61 - 66 Patients with severe lower respiratory tract disease without alternative etiologies and a clear history of exposure should be considered having COVID-19 unless confirmed otherwise. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), sending tests to check SARS-CoV-2 in suspected cases is based on physicians’ clinical judgment. Although there are some positive cases without clinical manifestations (ie, fever and/or symptoms of acute respiratory illness such as cough and dyspnea), infectious disease and control centers should take action in society to limit the exposure of such patients to other healthy individuals. The CDC prioritizes the use of the specific test for hospitalized patients, symptomatic patients who are at risk of fatal conditions (eg, age ≥65 y, chronic medical conditions, and immunocompromising conditions) and those who have exposure risks (recent travel, contact with patients with COVID-19, and healthcare workers). 61 - 66 Although treatment should be started after the confirmation of the disease, RT-PCR for highly suspected cases is a time-consuming test; accordingly, a considerable number of clinicians favor the use of a combination of clinical manifestations with imaging modalities (eg, CT-Scan findings) and their clinical judgment regarding the probability of the disease in order not to lose more time. 61 - 66

Treatment of COVID-19

There is no confirmed recommended treatment or vaccine for SARS-CoV-2; prevention is, therefore, better than treatment. Nevertheless, the high contagiousness of COVID-19, combined with the fact that some individuals fail to adhere to precautionary measures or they have significant risk factors, means that this infectious disease is inevitable in some people. Beside supportive treatments, many types of medications have been introduced. These medications come from previous experimental studies on SARS, MERS, influenza, or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV); hence, their efficacy needs further experimental and clinical approval. Patients with mild symptoms who do not have significant risk factors should be managed in their home like a self-made quarantine (in an isolated room); still, prompt hospital admission is required if patients exhibit signs of disease deterioration. 25 , 67 , 68 Isolation from other family members is an important prevention tip. Patients should wear face masks, eat healthy and warm foods similar to when struggling with influenza or colds, do the handwashing process, dispose of the contaminated materials cautiously, and disinfect suspicious surfaces with standard disinfectants. 69 Patients with severe symptoms or admission criteria should be hospitalized with other patients who have the same disease in an isolated department. When the disease is progressed, ICU care is mandatory. 25 , 67 , 68 SARS-CoV-2 attacks the respiratory system, diminishing the oxygenation process and forcing patients with low blood oxygen saturation to take extra oxygen from different modalities. Nasal cannulae, face masks with or without a reservoir, intubation in severe cases, and then extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in refractory hypoxia have been used; however, the safety and efficacy of these measures should be evaluated. As was mentioned above, impaired coagulation is one of the major complications of the disease; consequently, alongside all recommended supportive care and drugs, anticoagulants such as heparin should be administered prophylactically ( Table 1 ). Although it is said that all the clinical signs and symptoms of COVID-19 are induced by the immune system, as other research on influenza and MERS has revealed, glucocorticoids are not recommended in COVID-19 pneumonia unless other indications are present (eg, exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and refractory septic shock) due to the high risk of mortality and delayed viral clearance. Earlier in the national and international guidelines, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as naproxen were recommended on the strength of their antipyretic and anti-inflammatory components; however, the guideline has been revised recently and acetaminophen with or without codeine is currently the favored drug in patients with COVID-19. 25 , 67 , 68 According to the pathogenesis of the disease, whereby cytokine storm and immune-cell exhaustion can be seen in severe cases, selective antibodies against harmful interleukins such as IL-6 and IL-10 or other possible agents can be therapeutic for fatal complications. Tocilizumab, an IL-6 inhibitor, albeit with limited clinical efficacy, has been introduced in China’s National Health Commission treatment guideline for severe infection with profound pulmonary involvement (ie, white lung). 70 , 87

Summary of possible anti-COVID-19 drugs

mg, Milligrams; BD, Every 12 hours; RdRP, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase; TDS, Every 8 hours; IV, Intravenous; IL, Interleukin; μg, Micrograms

RNA synthesis inhibitors (eg, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and 2’-deoxy-3’-thiacytidine [3TC]), neuraminidase inhibitors (NAIs), nucleoside analogs, lopinavir/ritonavir, atazanavir, remdesivir, favipiravir, INF-β, and Chinese traditional medicine (eg, Shufeng Jiedu and Lianhuaqingwen capsules) are the major candidates for COVID-19. 26 , 70 , 85 , 88 - 96 Antiviral drugs have been investigated for various diseases, but their efficacy in the treatment of COVID-19 is under investigation and several randomized clinical trials are ongoing to release a consensus result on the treatment of this infectious disease. Moderate-to-severe SARS-CoV-2 disease needs drug therapy. Favipiravir, a previously validated drug for influenza, is a drug that has shown promising results for COVID-19 in experimental and clinical studies, but it is under further evaluation. 70 , 79 , 80 Remdesivir, which was developed for Ebola, is an antiviral drug that is under evaluation for moderate-to-severe COVID-19 owing to its promising results in in vitro investigations. 70 , 73 - 75 , 81 Remdesivir was shown to have reduced the virus titer in infected mice with MERS-CoV and improved lung tissue damage with more efficiency compared with a group treated with lopinavir/ritonavir/INF-β. 67 , 70 Another investigation studied the potential efficacy of INF-β-1 in the early stages of COVID-19 as a potential antiviral drug. 86 Although there is some hope, an evidence-based consensus requires further clinical trials. 70 , 77 A combined protease inhibitor, lopinavir/ritonavir, is used for HIV infection and has shown interesting results for SARS and MERS in in vitro studies. 73 - 75 The clinical effectiveness of lopinavir/ritonavir for SARS-CoV-2 was also reported in a case report. 70 , 71 , 74 , 76 Atazanavir, another protease inhibitor, with or without ritonavir is another possible anti-COVID-19 treatment. 77 , 78 NAIs, including oseltamivir, zanamivir, and peramivir, are recommended as antiviral treatment in influenza. 68 Oral oseltamivir was tried for COVID-19 in China and was first recommended in the Iranian guideline for COVID-19 treatment; nevertheless, because of the absence of strong evidence indicating its efficacy for SARS-CoV-2, it was eliminated from the subsequent updates of the guideline. 85 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase inhibitors with anti-hepatitis C effects such as ribavirin have shown satisfactory results against SARS-CoV-2 RNA polymerase; however, they have limited clinical approval. 82 - 84 The well-known drugs for rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and an antimalarial drug, chloroquine 71 and hydroxychloroquine 21 are other potential drugs for moderate-to-severe COVID-19 but with limited or no clinical appraisal. Hydroxychloroquine has exhibited better safety and fewer side effects than chloroquine, which makes it the preferred choice. 70 Furthermore, the immunomodulatory effects of hydroxychloroquine can be used to control the cytokine precipitation in the late phases of SARS-CoV-2 infections. There are numerous mechanisms for the antiviral activity of hydroxychloroquine. A weak base drug, hydroxychloroquine concentrates on such intracellular sections as endosomes and lysosomes, thereby halting viral replication in the phase of fusion and uncoating. Additionally, this immunosuppressive and antiparasitic drug is capable of altering the glycosylation of ACE2 and inhibiting both S-protein binding and phagocytosis. 72 A recent multicenter study showed that regarding the risks of cardiovascular adverse effects and mortality rates, hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine with or without a macrolide (eg, azithromycin) was not beneficial for hospitalized patients, although further research is needed to end such controversies. 97

Disease Duration

It is not easy to quarantine the patients who have fully recovered because there is evidence that they are highly infectious. 81 The recovery time for confirmed cases based on the National Health Commission reports of China’s government was estimated to range between 18 and 22 days. 73 As indicated by the WHO, the healing time seems to be around two weeks for moderate infections and 3 to 6 weeks for the severe/ serious disease. 75 Pan Feng and others studied 21 confirmed cases with COVID-19 pneumonia with about 82 CT-Scan images with a mean interval of four days. Lung abnormalities on chest CT showed the highest severity approximately 10 days after the initial onset of symptoms. All patients became clear after 11 to 26 days of hospitalization. From day zero to day 26, four stages of lung CT were defined as follows: Stage 1 (first 4 days): ground-glass opacities; Stage 2 (second 4 days): crazy-paving patterns; Stage 3 (days 9–13): maximum total CT scores in the consolidations; and Stage 4 (≥14 d): steady improvements in the consolidations with a reduction in the total CT score without any crazy-paving pattern. 74 Nevertheless, there are also rare cases reported from some studies that show the recurrence of COVID-19 after negative preliminary RT-PCR results. For example, Lan and othersstudied one hospitalized and three home-quarantined patients with COVID-19 and evaluated them with RT-PCR tests of the nucleic acid. All the patients with positive RT-PCR test results had CT imaging with ground-glass opacification or mixed ground-glass opacification and consolidation with mild-to-moderate disease. After antiviral treatments, all four patients had two consecutive negative RT-PCR test results within 12 to 32 days. Five to 13 days after hospital discharge or the discontinuation of the quarantine, RT-PCR tests were repeated, and all were positive. An additional RT-PCR test was performed using a kit from a different manufacturer, and the results were also positive. Their findings propose that a minimum percentage of recovered patients may still be infection carriers. 76

Supplements for COVID-19

Since the appearance of SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan, China, there have been reports of the unreliable and unpredictable use of mysterious therapies. Some recommendations such as the use of certain herbs and extracts including oregano oil, mulberry leaf, garlic, and black sesame may be safe as long as people do not utilize their hands for instance. 98 According to data released by the CDC, vitamin C (VitC) supplements can decrease the risk of colds in people besides preventing CoV from spreading. The aforementioned organization states that frequent consumption of VitC supplements can also decrease the duration of the cold; however, if used only after the cold has risen, its consumption does not influence the disease course. VitC also plays an important role in the body. One of the main reasons for taking VitC is to strengthen the immune system because this vitamin plays a significant part in the immune system. Firstly, VitC can increase the production of white blood cells (lymphocytes and phagocytes) in the bone marrow, which can support and protect the body against infections. Secondly, VitC helps immune cells to function better while preserving white blood cells from damaging molecules such as free oxidative radicals and ions. Thirdly, VitC is an essential part of the skin’s immune system. This vitamin is actively transported to the skin surface, where it serves as an antioxidant and helps to strengthen the skin barrier by optimizing the collagen synthesis process. Patients with pneumonia have lower levels of VitC and have been revealed to have a longer recovery time. 69 , 99 In a randomized investigation, 200 mg/d of VitC was applied to older patients and resulted in improvements in the respiratory symptoms. Another investigation reported 80% fewer mortalities in a controlled group of VitC takers. 73 However, for effective immune system improvement, VitC should be consumed alongside adequate doses of several other supplements. Although VitC plays an important role in the body, often a balanced diet and the consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables can quickly fill the blanks. While taking high amounts of VitC is less risky because it is water-soluble and its waste is eliminated in the urine, it can induce diarrhea, nausea, and abdominal spasms at higher concentrations. Too much VitC may cause calcium-oxalate kidney stones. People with genetic hemochromatosis, an iron deficiency disorder, should consult a physician before taking any VitC supplements as high levels of VitC can lead to tissue damage. Some studies have evaluated the different doses of oral or intravenous VitC for patients admitted to the hospital for COVID-19. Although they used different regimens, all of them demonstrated satisfactory results regarding the resolution of the compilations of the disease, decreased mortality, and shortened lengths of stay in the ICU and/or the hospital. 100 , 101 Immunologists have also recommended 6 000 units of vitamin A (VitA) per day for two weeks, more than twice the recommended limit for VitA, which can create a poisoning environment over time. According to the guidance of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), middle-aged men and women should take 1 and 2 mg of VitA every day, respectively. The safe upper limit of this vitamin is 6000 mg or 5000 units, and overdose can have serious outcomes such as dizziness, nausea, headache, coma, and even death. Extreme consumption of VitA throughout pregnancy can lead to birth anomalies.

Similar to VitC, vitamin D (VitD) has antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and immune-modulatory effects in our body such as reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines and inhibiting viral replication according to experimental studies. 83 The VitD state of our body is checked through 25 (OH) VitD in the serum. VitD deficiency is pandemic around the world due to multifactorial reasons. It has been shown that VitD deficient patients are prone to SARS-CoV-2 and, accordingly, treating VitD deficiency is not without benefits. Grant and others recommended 10 000 units per day for two weeks and then 5 000 units per day as the maintenance dose to keep the level between 40 and 100 ng/mL. 102 VitD toxicity causes gastrointestinal discomfort (dyspepsia), congestion, hypercalcemia, confusion, positional disorders, dysrhythmia, and kidney dysfunction.

James Robb, 103 a researcher who detected CoV for the first time as a consultant pathologist with the National Cancer Institute of America, suggested the influence of zinc consumption. Oral zinc supplements can be dissolved in the nback of the throat. Short-term therapy with oral zinc can decrease the duration of viral colds in adults. Zinc intake is also associated with the faster resolution of nasal congestion, nasal drainage, sore throats, and coughs. Researchers 104 , 105 have warned that the consumption of more than 1 mg of zinc a day can lead to zinc poisoning and have side effects such as lowered immune function. Children and old people with zinc insufficiency in developing nations are extremely vulnerable to pneumonia and other viral infections. It has also been determined that zinc has a major role in the production and activation of T-cell lymphocytes. 106 , 107

And finally, for high-risk people or those who work in high-risk places such as healthcare providers, hydroxychloroquine has been mentioned to be effective as a prophylactic regimen ( Table 2 ). Although different doses have been investigated so far, Pourdowlat and others recommended 200 mg daily before exposure, and for the post-exposure scenario, a loading dose of 600-800 mg followed by a maintenance dose of 200 mg daily. 74

Possible prophylactic regimens against SARS-CoV-2 infection

IU, International unit; mg, Milligrams; kg, Kilograms; ICU, Intensive care unit; g, Grams; IV, Intravenous; Vit, Vitamin; ng, Nanograms; mL, Milliliter

COVID-19 Kits and Deep Learning

COVID-19 has threatened public health, and its fast global spread has caught the scientific community by surprise. 108 Hence, developing a technique capable of swiftly and reliably detecting the virus in patients is vital to prevent the spreading of the virus. 109 , 110 One of the ways to diagnose this new virus is through RT-PCR, a test that has previously demonstrated its efficacy in detecting such CoV infections as MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV. Consequently, increasing the availability of RT-PCR kits is a worldwide concern. The timing of the RT-PCR test and the type of strain collected are of vital importance in the diagnosis of COVID-19. One of the characteristics of this new virus is that the serum is negative in the early stage, while respiratory specimens are positive. The level of the virus at the early stage of the illness is also high, even though the infected individual experiences mild symptoms. 111 For the management of the emerging situation of COVID-19 in Wuhan, various effective diagnostic kits were urgently made available to markets. While a few different diagnostics kits are used merely for research endeavors, only a single kit developed by the Beijing Genome Institute (BGI) called “Real-Time Fluorescent PCR” has been authenticated for clinical diagnostics. Fluorescent RT-PCR is reliable and able to offer fast results probably within a few hours (usually within two hours). Besides RT-PCR, China has successfully developed a metagenomic-sequencing kit based on combinatorial probe-anchor synthesis that can identify virus-related bacteria, allowing observation and evaluation during the transmission of the virus. Furthermore, the metagenomic-sequencing kit based on combinatorial probe-anchor synthesis is far faster than the abovementioned fluorescent RT-PCR kit. Apart from China, a Singapore-based laboratory, Veredus, developed a virus detection kit (Vere-CoV) in late January. It is a portable Lab-On-Chip used to detect MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2, in a single examination. This kit works based on the VereChip™ technology, the lines of code (LOC) program incorporating two different influential molecular biological functions (microarray and PCR) precisely. Several studies have focused on SARS-CoV diagnostic testing. These papers have presented investigative approaches to the identification of the virus using molecular testing (ie, RT-PCR). Researchers probed into the use of a nested PCR technique that contains a pre-amplification step or integrating the N gene as an extra subtle molecular marker to improve on the sensitivity. 112 - 115 CT-Scan is very useful for diagnosing, evaluating, and screening infections caused by COVID-19. One recommendation for scanning the disease is to take a scan every three to five days. According to researchers, most CT-Scan images from patients with COVID-19 are bilateral or peripheral ground-glass opacification, with or without stabilization. Nowadays, because of a paucity of computerized quantification tools, only qualitative reports and sometimes inaccurate analyses of contaminated areas are drawn upon in radiology reports. A categorization system based on the deep learning approach was proposed by a study to automatically measure infected parts and their volumetric ratios in the lung. The functionality of this system was evaluated by making some comparisons between the infected portions and the manually-delineated ones on the CT-Scan images of 300 patients with COVID-19. To increase the manual drawing of training samples and the non-interference in the automated results, researchers adopted a human-based approach in collaboration with radiologists so as to segment the infected region. This approach shortens the time to about four minutes after 3-time updating. The mean Dice similarity coefficient illustrated that the automatically detected infected parts were 91.6% similar to the manually detected ones, and the average of the percentage estimated error was 0.3% for the whole lung. 116 , 117

Prevention Considerations

In the healthcare setting, any individual with the manifestations of COVID-19 (eg, fever, cough, and dyspnea) should wear a face mask, have a separate waiting area, and keep the distance of at least two meters. Symptomatic patients should be asked about recent travel or close contact with a patient in the preceding two weeks to find other possible infected patients. The CDC and WHO have announced special precautions for healthcare providers in the hospital and during different procedures. Wearing tight-fitting face masks with special filters and impermeable face shields is necessary for all of them. 11 , 18 , 65 , 66 , 76 , 118 - 124 Other people should pay attention to the CDC and WHO preventive strategies, which recommend that individuals not touch their eyes, mouth, and nose before washing or disinfecting their hands; wash their hands regularly according to the standard protocol; use effective disinfection solutions (ie, containing at least 60% ethylic alcohol) for contaminated surfaces; cover their mouth when coughing and sneezing; avoid waiting or walking in crowded areas, and observe isolation protocols in their home. Postponing elective work and decreasing non-urgent visits and traveling to areas in the grip of COVID-19 may be useful to lessen the risk of exposure. If suspected individuals with mild symptoms are managed in outpatient settings, an isolated room with minimal exposure to others should be designed. Patients and their caregivers should wear tight-fitting face masks. 11 , 18 , 65 , 66 , 76 , 118 - 124 Substantial numbers of individuals with COVID-19 are asymptomatic with potential exposure; accordingly, a screening tool should be employed to evaluate these cases. In addition to passport checks, corona checks have been incorporated into the protocols in airports and other crowded places. The use of a remote thermometer to measure body temperature leads to an increase in the number of false-negative cases. It is, thus, essential that everyone pay sufficient heed to the WHO and CDC recommendations in their daily life. Traveling is not prohibited, but it should be restricted and passengers from any country should be monitored. 11 , 18 , 65 , 66 , 76 , 118 - 124

SARS-CoV-2 is the new highly contagious CoV, which was first reported in China. While it had a zoonotic origin in the beginning, it subsequently spread throughout the world by human contact. COVID-19 has a spectrum of manifestations, which is not lethal most of the time. To diagnose this condition, physicians can avail themselves of laboratory and imaging findings besides signs and symptoms. RT-PCR is the gold standard, but it lacks sufficient sensitivity and specificity. Although there are some potential drugs for COVID-19 and some vitamins or minerals for prophylaxis, the best preventive strategies are quarantine (staying at home) and the use of personal protective equipment and disinfectants.

Acknowledgement

The authors express their gratitude toward the Supporting Organizations for Foreign Iranian Students, Islamic Azad University Isfahan (Khorasgan) Branch, and Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Read these 12 moving essays about life during coronavirus

Artists, novelists, critics, and essayists are writing the first draft of history.

by Alissa Wilkinson

The world is grappling with an invisible, deadly enemy, trying to understand how to live with the threat posed by a virus . For some writers, the only way forward is to put pen to paper, trying to conceptualize and document what it feels like to continue living as countries are under lockdown and regular life seems to have ground to a halt.

So as the coronavirus pandemic has stretched around the world, it’s sparked a crop of diary entries and essays that describe how life has changed. Novelists, critics, artists, and journalists have put words to the feelings many are experiencing. The result is a first draft of how we’ll someday remember this time, filled with uncertainty and pain and fear as well as small moments of hope and humanity.

- The Vox guide to navigating the coronavirus crisis

At the New York Review of Books, Ali Bhutto writes that in Karachi, Pakistan, the government-imposed curfew due to the virus is “eerily reminiscent of past military clampdowns”:

Beneath the quiet calm lies a sense that society has been unhinged and that the usual rules no longer apply. Small groups of pedestrians look on from the shadows, like an audience watching a spectacle slowly unfolding. People pause on street corners and in the shade of trees, under the watchful gaze of the paramilitary forces and the police.

His essay concludes with the sobering note that “in the minds of many, Covid-19 is just another life-threatening hazard in a city that stumbles from one crisis to another.”

Writing from Chattanooga, novelist Jamie Quatro documents the mixed ways her neighbors have been responding to the threat, and the frustration of conflicting direction, or no direction at all, from local, state, and federal leaders:

Whiplash, trying to keep up with who’s ordering what. We’re already experiencing enough chaos without this back-and-forth. Why didn’t the federal government issue a nationwide shelter-in-place at the get-go, the way other countries did? What happens when one state’s shelter-in-place ends, while others continue? Do states still under quarantine close their borders? We are still one nation, not fifty individual countries. Right?

- A syllabus for the end of the world

Award-winning photojournalist Alessio Mamo, quarantined with his partner Marta in Sicily after she tested positive for the virus, accompanies his photographs in the Guardian of their confinement with a reflection on being confined :

The doctors asked me to take a second test, but again I tested negative. Perhaps I’m immune? The days dragged on in my apartment, in black and white, like my photos. Sometimes we tried to smile, imagining that I was asymptomatic, because I was the virus. Our smiles seemed to bring good news. My mother left hospital, but I won’t be able to see her for weeks. Marta started breathing well again, and so did I. I would have liked to photograph my country in the midst of this emergency, the battles that the doctors wage on the frontline, the hospitals pushed to their limits, Italy on its knees fighting an invisible enemy. That enemy, a day in March, knocked on my door instead.

In the New York Times Magazine, deputy editor Jessica Lustig writes with devastating clarity about her family’s life in Brooklyn while her husband battled the virus, weeks before most people began taking the threat seriously:

At the door of the clinic, we stand looking out at two older women chatting outside the doorway, oblivious. Do I wave them away? Call out that they should get far away, go home, wash their hands, stay inside? Instead we just stand there, awkwardly, until they move on. Only then do we step outside to begin the long three-block walk home. I point out the early magnolia, the forsythia. T says he is cold. The untrimmed hairs on his neck, under his beard, are white. The few people walking past us on the sidewalk don’t know that we are visitors from the future. A vision, a premonition, a walking visitation. This will be them: Either T, in the mask, or — if they’re lucky — me, tending to him.

Essayist Leslie Jamison writes in the New York Review of Books about being shut away alone in her New York City apartment with her 2-year-old daughter since she became sick:

The virus. Its sinewy, intimate name. What does it feel like in my body today? Shivering under blankets. A hot itch behind the eyes. Three sweatshirts in the middle of the day. My daughter trying to pull another blanket over my body with her tiny arms. An ache in the muscles that somehow makes it hard to lie still. This loss of taste has become a kind of sensory quarantine. It’s as if the quarantine keeps inching closer and closer to my insides. First I lost the touch of other bodies; then I lost the air; now I’ve lost the taste of bananas. Nothing about any of these losses is particularly unique. I’ve made a schedule so I won’t go insane with the toddler. Five days ago, I wrote Walk/Adventure! on it, next to a cut-out illustration of a tiger—as if we’d see tigers on our walks. It was good to keep possibility alive.

At Literary Hub, novelist Heidi Pitlor writes about the elastic nature of time during her family’s quarantine in Massachusetts:

During a shutdown, the things that mark our days—commuting to work, sending our kids to school, having a drink with friends—vanish and time takes on a flat, seamless quality. Without some self-imposed structure, it’s easy to feel a little untethered. A friend recently posted on Facebook: “For those who have lost track, today is Blursday the fortyteenth of Maprilay.” ... Giving shape to time is especially important now, when the future is so shapeless. We do not know whether the virus will continue to rage for weeks or months or, lord help us, on and off for years. We do not know when we will feel safe again. And so many of us, minus those who are gifted at compartmentalization or denial, remain largely captive to fear. We may stay this way if we do not create at least the illusion of movement in our lives, our long days spent with ourselves or partners or families.

- What day is it today?

Novelist Lauren Groff writes at the New York Review of Books about trying to escape the prison of her fears while sequestered at home in Gainesville, Florida:

Some people have imaginations sparked only by what they can see; I blame this blinkered empiricism for the parks overwhelmed with people, the bars, until a few nights ago, thickly thronged. My imagination is the opposite. I fear everything invisible to me. From the enclosure of my house, I am afraid of the suffering that isn’t present before me, the people running out of money and food or drowning in the fluid in their lungs, the deaths of health-care workers now growing ill while performing their duties. I fear the federal government, which the right wing has so—intentionally—weakened that not only is it insufficient to help its people, it is actively standing in help’s way. I fear we won’t sufficiently punish the right. I fear leaving the house and spreading the disease. I fear what this time of fear is doing to my children, their imaginations, and their souls.

At ArtForum , Berlin-based critic and writer Kristian Vistrup Madsen reflects on martinis, melancholia, and Finnish artist Jaakko Pallasvuo’s 2018 graphic novel Retreat , in which three young people exile themselves in the woods:

In melancholia, the shape of what is ending, and its temporality, is sprawling and incomprehensible. The ambivalence makes it hard to bear. The world of Retreat is rendered in lush pink and purple watercolors, which dissolve into wild and messy abstractions. In apocalypse, the divisions established in genesis bleed back out. My own Corona-retreat is similarly soft, color-field like, each day a blurred succession of quarantinis, YouTube–yoga, and televized press conferences. As restrictions mount, so does abstraction. For now, I’m still rooting for love to save the world.

At the Paris Review , Matt Levin writes about reading Virginia Woolf’s novel The Waves during quarantine:

A retreat, a quarantine, a sickness—they simultaneously distort and clarify, curtail and expand. It is an ideal state in which to read literature with a reputation for difficulty and inaccessibility, those hermetic books shorn of the handholds of conventional plot or characterization or description. A novel like Virginia Woolf’s The Waves is perfect for the state of interiority induced by quarantine—a story of three men and three women, meeting after the death of a mutual friend, told entirely in the overlapping internal monologues of the six, interspersed only with sections of pure, achingly beautiful descriptions of the natural world, a day’s procession and recession of light and waves. The novel is, in my mind’s eye, a perfectly spherical object. It is translucent and shimmering and infinitely fragile, prone to shatter at the slightest disturbance. It is not a book that can be read in snatches on the subway—it demands total absorption. Though it revels in a stark emotional nakedness, the book remains aloof, remote in its own deep self-absorption.

- Vox is starting a book club. Come read with us!

In an essay for the Financial Times, novelist Arundhati Roy writes with anger about Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s anemic response to the threat, but also offers a glimmer of hope for the future:

Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.

From Boston, Nora Caplan-Bricker writes in The Point about the strange contraction of space under quarantine, in which a friend in Beirut is as close as the one around the corner in the same city:

It’s a nice illusion—nice to feel like we’re in it together, even if my real world has shrunk to one person, my husband, who sits with his laptop in the other room. It’s nice in the same way as reading those essays that reframe social distancing as solidarity. “We must begin to see the negative space as clearly as the positive, to know what we don’t do is also brilliant and full of love,” the poet Anne Boyer wrote on March 10th, the day that Massachusetts declared a state of emergency. If you squint, you could almost make sense of this quarantine as an effort to flatten, along with the curve, the distinctions we make between our bonds with others. Right now, I care for my neighbor in the same way I demonstrate love for my mother: in all instances, I stay away. And in moments this month, I have loved strangers with an intensity that is new to me. On March 14th, the Saturday night after the end of life as we knew it, I went out with my dog and found the street silent: no lines for restaurants, no children on bicycles, no couples strolling with little cups of ice cream. It had taken the combined will of thousands of people to deliver such a sudden and complete emptiness. I felt so grateful, and so bereft.

And on his own website, musician and artist David Byrne writes about rediscovering the value of working for collective good , saying that “what is happening now is an opportunity to learn how to change our behavior”:

In emergencies, citizens can suddenly cooperate and collaborate. Change can happen. We’re going to need to work together as the effects of climate change ramp up. In order for capitalism to survive in any form, we will have to be a little more socialist. Here is an opportunity for us to see things differently — to see that we really are all connected — and adjust our behavior accordingly. Are we willing to do this? Is this moment an opportunity to see how truly interdependent we all are? To live in a world that is different and better than the one we live in now? We might be too far down the road to test every asymptomatic person, but a change in our mindsets, in how we view our neighbors, could lay the groundwork for the collective action we’ll need to deal with other global crises. The time to see how connected we all are is now.

The portrait these writers paint of a world under quarantine is multifaceted. Our worlds have contracted to the confines of our homes, and yet in some ways we’re more connected than ever to one another. We feel fear and boredom, anger and gratitude, frustration and strange peace. Uncertainty drives us to find metaphors and images that will let us wrap our minds around what is happening.

Yet there’s no single “what” that is happening. Everyone is contending with the pandemic and its effects from different places and in different ways. Reading others’ experiences — even the most frightening ones — can help alleviate the loneliness and dread, a little, and remind us that what we’re going through is both unique and shared by all.

Most Popular

The hottest place on earth is cracking from the stress of extreme heat, the backlash against children’s youtuber ms rachel, explained, take a mental break with the newest vox crossword, an artist snuck an anti-semitic message into marvel’s newest x-men comic book, openai insiders are demanding a “right to warn” the public, today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

More in Culture

Kate Middleton’s cancer diagnosis, explained

Why are we so obsessed with morning routines?

Here are all 50+ sexual misconduct allegations against Kevin Spacey

Is TikTok breaking young voters’ brains?

Backgrid paparazzi photos are everywhere. Is that such a big deal?

Modi won the Indian election. So why does it seem like he lost?

Baby Reindeer’s “Martha” is, inevitably, suing Netflix

Where AI predictions go wrong

The failure of the college president

Trump’s felony conviction has hurt him in the polls

How to Write About Coronavirus in a College Essay

Students can share how they navigated life during the coronavirus pandemic in a full-length essay or an optional supplement.

Writing About COVID-19 in College Essays

Getty Images

Experts say students should be honest and not limit themselves to merely their experiences with the pandemic.

The global impact of COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, means colleges and prospective students alike are in for an admissions cycle like no other. Both face unprecedented challenges and questions as they grapple with their respective futures amid the ongoing fallout of the pandemic.

Colleges must examine applicants without the aid of standardized test scores for many – a factor that prompted many schools to go test-optional for now . Even grades, a significant component of a college application, may be hard to interpret with some high schools adopting pass-fail classes last spring due to the pandemic. Major college admissions factors are suddenly skewed.

"I can't help but think other (admissions) factors are going to matter more," says Ethan Sawyer, founder of the College Essay Guy, a website that offers free and paid essay-writing resources.

College essays and letters of recommendation , Sawyer says, are likely to carry more weight than ever in this admissions cycle. And many essays will likely focus on how the pandemic shaped students' lives throughout an often tumultuous 2020.

But before writing a college essay focused on the coronavirus, students should explore whether it's the best topic for them.

Writing About COVID-19 for a College Application

Much of daily life has been colored by the coronavirus. Virtual learning is the norm at many colleges and high schools, many extracurriculars have vanished and social lives have stalled for students complying with measures to stop the spread of COVID-19.

"For some young people, the pandemic took away what they envisioned as their senior year," says Robert Alexander, dean of admissions, financial aid and enrollment management at the University of Rochester in New York. "Maybe that's a spot on a varsity athletic team or the lead role in the fall play. And it's OK for them to mourn what should have been and what they feel like they lost, but more important is how are they making the most of the opportunities they do have?"

That question, Alexander says, is what colleges want answered if students choose to address COVID-19 in their college essay.

But the question of whether a student should write about the coronavirus is tricky. The answer depends largely on the student.

"In general, I don't think students should write about COVID-19 in their main personal statement for their application," Robin Miller, master college admissions counselor at IvyWise, a college counseling company, wrote in an email.

"Certainly, there may be exceptions to this based on a student's individual experience, but since the personal essay is the main place in the application where the student can really allow their voice to be heard and share insight into who they are as an individual, there are likely many other topics they can choose to write about that are more distinctive and unique than COVID-19," Miller says.

Opinions among admissions experts vary on whether to write about the likely popular topic of the pandemic.

"If your essay communicates something positive, unique, and compelling about you in an interesting and eloquent way, go for it," Carolyn Pippen, principal college admissions counselor at IvyWise, wrote in an email. She adds that students shouldn't be dissuaded from writing about a topic merely because it's common, noting that "topics are bound to repeat, no matter how hard we try to avoid it."

Above all, she urges honesty.

"If your experience within the context of the pandemic has been truly unique, then write about that experience, and the standing out will take care of itself," Pippen says. "If your experience has been generally the same as most other students in your context, then trying to find a unique angle can easily cross the line into exploiting a tragedy, or at least appearing as though you have."

But focusing entirely on the pandemic can limit a student to a single story and narrow who they are in an application, Sawyer says. "There are so many wonderful possibilities for what you can say about yourself outside of your experience within the pandemic."

He notes that passions, strengths, career interests and personal identity are among the multitude of essay topic options available to applicants and encourages them to probe their values to help determine the topic that matters most to them – and write about it.

That doesn't mean the pandemic experience has to be ignored if applicants feel the need to write about it.

Writing About Coronavirus in Main and Supplemental Essays

Students can choose to write a full-length college essay on the coronavirus or summarize their experience in a shorter form.

To help students explain how the pandemic affected them, The Common App has added an optional section to address this topic. Applicants have 250 words to describe their pandemic experience and the personal and academic impact of COVID-19.

"That's not a trick question, and there's no right or wrong answer," Alexander says. Colleges want to know, he adds, how students navigated the pandemic, how they prioritized their time, what responsibilities they took on and what they learned along the way.

If students can distill all of the above information into 250 words, there's likely no need to write about it in a full-length college essay, experts say. And applicants whose lives were not heavily altered by the pandemic may even choose to skip the optional COVID-19 question.

"This space is best used to discuss hardship and/or significant challenges that the student and/or the student's family experienced as a result of COVID-19 and how they have responded to those difficulties," Miller notes. Using the section to acknowledge a lack of impact, she adds, "could be perceived as trite and lacking insight, despite the good intentions of the applicant."

To guard against this lack of awareness, Sawyer encourages students to tap someone they trust to review their writing , whether it's the 250-word Common App response or the full-length essay.

Experts tend to agree that the short-form approach to this as an essay topic works better, but there are exceptions. And if a student does have a coronavirus story that he or she feels must be told, Alexander encourages the writer to be authentic in the essay.

"My advice for an essay about COVID-19 is the same as my advice about an essay for any topic – and that is, don't write what you think we want to read or hear," Alexander says. "Write what really changed you and that story that now is yours and yours alone to tell."

Sawyer urges students to ask themselves, "What's the sentence that only I can write?" He also encourages students to remember that the pandemic is only a chapter of their lives and not the whole book.

Miller, who cautions against writing a full-length essay on the coronavirus, says that if students choose to do so they should have a conversation with their high school counselor about whether that's the right move. And if students choose to proceed with COVID-19 as a topic, she says they need to be clear, detailed and insightful about what they learned and how they adapted along the way.

"Approaching the essay in this manner will provide important balance while demonstrating personal growth and vulnerability," Miller says.

Pippen encourages students to remember that they are in an unprecedented time for college admissions.

"It is important to keep in mind with all of these (admission) factors that no colleges have ever had to consider them this way in the selection process, if at all," Pippen says. "They have had very little time to calibrate their evaluations of different application components within their offices, let alone across institutions. This means that colleges will all be handling the admissions process a little bit differently, and their approaches may even evolve over the course of the admissions cycle."

Searching for a college? Get our complete rankings of Best Colleges.

10 Ways to Discover College Essay Ideas

Tags: students , colleges , college admissions , college applications , college search , Coronavirus

2024 Best Colleges

Search for your perfect fit with the U.S. News rankings of colleges and universities.

College Admissions: Get a Step Ahead!

Sign up to receive the latest updates from U.S. News & World Report and our trusted partners and sponsors. By clicking submit, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions & Privacy Policy .

Ask an Alum: Making the Most Out of College

You May Also Like

Mental health on college campuses.

Sarah Wood June 6, 2024

Advice From Famous Commencement Speakers

Sarah Wood June 4, 2024

The Degree for Investment Bankers

Andrew Bauld May 31, 2024

States' Responses to FAFSA Delays

Sarah Wood May 30, 2024

Nonacademic Factors in College Searches

Sarah Wood May 28, 2024

Takeaways From the NCAA’s Settlement

Laura Mannweiler May 24, 2024

New Best Engineering Rankings June 18

Robert Morse and Eric Brooks May 24, 2024

Premedical Programs: What to Know

Sarah Wood May 21, 2024

How Geography Affects College Admissions

Cole Claybourn May 21, 2024

Q&A: College Alumni Engagement

LaMont Jones, Jr. May 20, 2024

- Current Issue

- Journal Archive

- Current Call

Search form

Coronavirus: My Experience During the Pandemic

Anastasiya Kandratsenka George Washington High School, Class of 2021

At this point in time there shouldn't be a single person who doesn't know about the coronavirus, or as they call it, COVID-19. The coronavirus is a virus that originated in China, reached the U.S. and eventually spread all over the world by January of 2020. The common symptoms of the virus include shortness of breath, chills, sore throat, headache, loss of taste and smell, runny nose, vomiting and nausea. As it has been established, it might take up to 14 days for the symptoms to show. On top of that, the virus is also highly contagious putting all age groups at risk. The elderly and individuals with chronic diseases such as pneumonia or heart disease are in the top risk as the virus attacks the immune system.

The virus first appeared on the news and media platforms in the month of January of this year. The United States and many other countries all over the globe saw no reason to panic as it seemed that the virus presented no possible threat. Throughout the next upcoming months, the virus began to spread very quickly, alerting health officials not only in the U.S., but all over the world. As people started digging into the origin of the virus, it became clear that it originated in China. Based on everything scientists have looked at, the virus came from a bat that later infected other animals, making it way to humans. As it goes for the United States, the numbers started rising quickly, resulting in the cancellation of sports events, concerts, large gatherings and then later on schools.

As it goes personally for me, my school was shut down on March 13th. The original plan was to put us on a two weeks leave, returning on March 30th but, as the virus spread rapidly and things began escalating out of control very quickly, President Trump announced a state of emergency and the whole country was put on quarantine until April 30th. At that point, schools were officially shut down for the rest of the school year. Distanced learning was introduced, online classes were established, a new norm was put in place. As for the School District of Philadelphia distanced learning and online classes began on May 4th. From that point on I would have classes four times a week, from 8AM till 3PM. Virtual learning was something that I never had to experience and encounter before. It was all new and different for me, just as it was for millions of students all over the United States. We were forced to transfer from physically attending school, interacting with our peers and teachers, participating in fun school events and just being in a classroom setting, to just looking at each other through a computer screen in a number of days. That is something that we all could have never seen coming, it was all so sudden and new.

My experience with distanced learning was not very great. I get distracted very easily and find it hard to concentrate, especially when it comes to school. In a classroom I was able to give my full attention to what was being taught, I was all there. However, when we had the online classes, I could not focus and listen to what my teachers were trying to get across. I got distracted very easily, missing out on important information that was being presented. My entire family which consists of five members, were all home during the quarantine. I have two little siblings who are very loud and demanding, so I’m sure it can be imagined how hard it was for me to concentrate on school and do what was asked of me when I had these two running around the house. On top of school, I also had to find a job and work 35 hours a week to support my family during the pandemic. My mother lost her job for the time being and my father was only able to work from home. As we have a big family, the income of my father was not enough. I made it my duty to help out and support our family as much as I could: I got a job at a local supermarket and worked there as a cashier for over two months.

While I worked at the supermarket, I was exposed to dozens of people every day and with all the protection that was implemented to protect the customers and the workers, I was lucky enough to not get the virus. As I say that, my grandparents who do not even live in the U.S. were not so lucky. They got the virus and spent over a month isolated, in a hospital bed, with no one by their side. Our only way of communicating was through the phone and if lucky, we got to talk once a week. Speaking for my family, that was the worst and scariest part of the whole situation. Luckily for us, they were both able to recover completely.

As the pandemic is somewhat under control, the spread of the virus has slowed down. We’re now living in the new norm. We no longer view things the same, the way we did before. Large gatherings and activities that require large groups to come together are now unimaginable! Distanced learning is what we know, not to mention the importance of social distancing and having to wear masks anywhere and everywhere we go. This is the new norm now and who knows when and if ever we’ll be able go back to what we knew before. This whole experience has made me realize that we, as humans, tend to take things for granted and don’t value what we have until it is taken away from us.

Articles in this Volume

[tid]: dedication, [tid]: new tools for a new house: transformations for justice and peace in and beyond covid-19, [tid]: black lives matter, intersectionality, and lgbtq rights now, [tid]: the voice of asian american youth: what goes untold, [tid]: beyond words: reimagining education through art and activism, [tid]: voice(s) of a black man, [tid]: embodied learning and community resilience, [tid]: re-imagining professional learning in a time of social isolation: storytelling as a tool for healing and professional growth, [tid]: reckoning: what does it mean to look forward and back together as critical educators, [tid]: leader to leaders: an indigenous school leader’s advice through storytelling about grief and covid-19, [tid]: finding hope, healing and liberation beyond covid-19 within a context of captivity and carcerality, [tid]: flux leadership: leading for justice and peace in & beyond covid-19, [tid]: flux leadership: insights from the (virtual) field, [tid]: hard pivot: compulsory crisis leadership emerges from a space of doubt, [tid]: and how are the children, [tid]: real talk: teaching and leading while bipoc, [tid]: systems of emotional support for educators in crisis, [tid]: listening leadership: the student voices project, [tid]: global engagement, perspective-sharing, & future-seeing in & beyond a global crisis, [tid]: teaching and leadership during covid-19: lessons from lived experiences, [tid]: crisis leadership in independent schools - styles & literacies, [tid]: rituals, routines and relationships: high school athletes and coaches in flux, [tid]: superintendent back-to-school welcome 2020, [tid]: mitigating summer learning loss in philadelphia during covid-19: humble attempts from the field, [tid]: untitled, [tid]: the revolution will not be on linkedin: student activism and neoliberalism, [tid]: why radical self-care cannot wait: strategies for black women leaders now, [tid]: from emergency response to critical transformation: online learning in a time of flux, [tid]: illness methodology for and beyond the covid era, [tid]: surviving black girl magic, the work, and the dissertation, [tid]: cancelled: the old student experience, [tid]: lessons from liberia: integrating theatre for development and youth development in uncertain times, [tid]: designing a more accessible future: learning from covid-19, [tid]: the construct of standards-based education, [tid]: teachers leading teachers to prepare for back to school during covid, [tid]: using empathy to cross the sea of humanity, [tid]: (un)doing college, community, and relationships in the time of coronavirus, [tid]: have we learned nothing, [tid]: choosing growth amidst chaos, [tid]: living freire in pandemic….participatory action research and democratizing knowledge at knowledgedemocracy.org, [tid]: philly students speak: voices of learning in pandemics, [tid]: the power of will: a letter to my descendant, [tid]: photo essays with students, [tid]: unity during a global pandemic: how the fight for racial justice made us unite against two diseases, [tid]: educational changes caused by the pandemic and other related social issues, [tid]: online learning during difficult times, [tid]: fighting crisis: a student perspective, [tid]: the destruction of soil rooted with culture, [tid]: a demand for change, [tid]: education through experience in and beyond the pandemics, [tid]: the pandemic diaries, [tid]: all for one and 4 for $4, [tid]: tiktok activism, [tid]: why digital learning may be the best option for next year, [tid]: my 2020 teen experience, [tid]: living between two pandemics, [tid]: journaling during isolation: the gold standard of coronavirus, [tid]: sailing through uncertainty, [tid]: what i wish my teachers knew, [tid]: youthing in pandemic while black, [tid]: the pain inflicted by indifference, [tid]: education during the pandemic, [tid]: the good, the bad, and the year 2020, [tid]: racism fueled pandemic, [tid]: coronavirus: my experience during the pandemic, [tid]: the desensitization of a doomed generation, [tid]: a philadelphia war-zone, [tid]: the attack of the covid monster, [tid]: back-to-school: covid-19 edition, [tid]: the unexpected war, [tid]: learning outside of the classroom, [tid]: why we should learn about college financial aid in school: a student perspective, [tid]: flying the plane as we go: building the future through a haze, [tid]: my covid experience in the age of technology, [tid]: we, i, and they, [tid]: learning your a, b, cs during a pandemic, [tid]: quarantine: a musical, [tid]: what it’s like being a high school student in 2020, [tid]: everything happens for a reason, [tid]: blacks live matter – a sobering and empowering reality among my peers, [tid]: the mental health of a junior during covid-19 outbreaks, [tid]: a year of change, [tid]: covid-19 and school, [tid]: the virtues and vices of virtual learning, [tid]: college decisions and the year 2020: a virtual rollercoaster, [tid]: quarantine thoughts, [tid]: quarantine through generation z, [tid]: attending online school during a pandemic.

Report accessibility issues and request help

Copyright 2024 The University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education's Online Urban Education Journal

- < Previous