Desmond Tutu, Ubuntu and the Possibility of Hope

Truth, Reconciliation, and Ubuntu

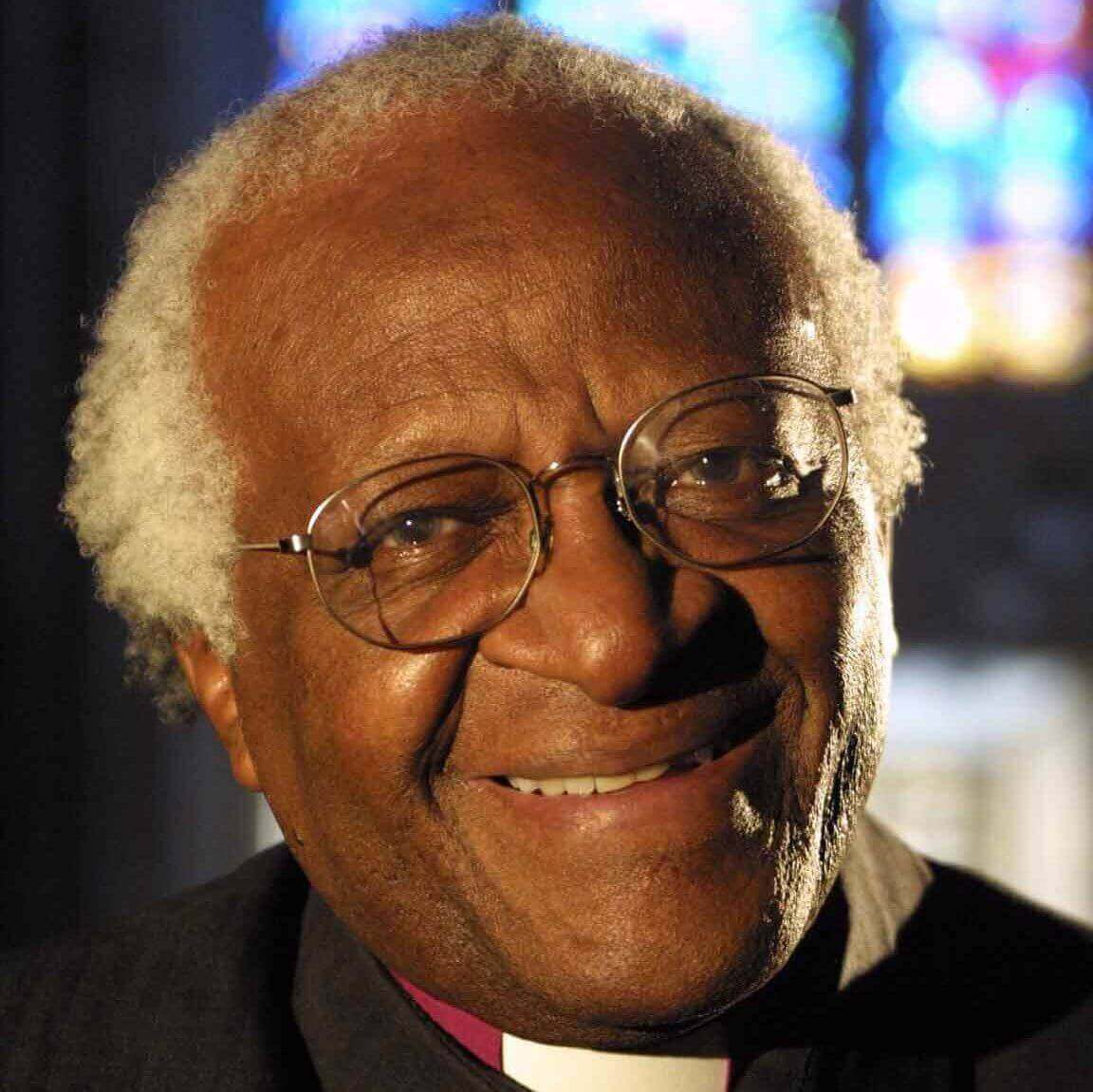

The day after Christmas day last year marked the death of Desmond Mpilo Tutu (1931 - 2021), the Nobel Prizewinner, anti-apartheid activist and former archbishop of Cape Town.

Tutu’s life was extraordinary, as is his legacy. Born in 1931 to Tswana and Xhosa parents, he studied theology in London before returning to his native South Africa, where he became a powerful voice in the fight against apartheid.

When I was growing up in the 1980s, Tutu was a familiar figure on the evening news: unstoppable, ebullient, fierce and uncompromising. In 1986, he was appointed Archbishop of Cape Town, and after the fall of apartheid, Nelson Mandela appointed him to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. In his book No Future Without Forgiveness , Tutu wrote of how the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was an attempt to balance, “justice, accountability, stability, peace, and reconciliation” while attempting to set out a public account of the horrors of the apartheid regime. [1]

Since Tutu’s death, I’ve been thinking again about his work, and also about its philosophical underpinnings. Because Tutu was responsible for helping to disseminate and popularise a philosophical concept that has since become widespread (and has also lent its name to a popular distribution of the Linux operating system): and that concept, of course, is the concept of ubuntu .

I’ve been wanting to write more about African philosophical traditions for a while here on Looking for Wisdom. So, this seems to be a good time to launch into this idea of ubuntu , to ask what it means, and why it matters.

What is Ubuntu?

The term ubuntu (and its variants) is found in languages from the Bantu language family. It is made up of two parts: the root ntu , and the prefix ubu . The root means something like “entity” or “object”, while the prefix ubu (or mu ) simply means “human.” So the term as a whole suggests the entity that is a human being. As such, it is both descriptive, in that it suggests what human beings are, and it is prescriptive, in that it suggests what human beings should be. Or, to put it in fancier philosophical language, it is both ontological (it talks about the nature of human being), and it is ethical (it talks about what it is for this particular being, human being, to be good).

Scholarly references to the term ubuntu and its equivalents go back to the middle of the twentieth century. And perhaps one of the most famously concise glosses of the term is that from the philosopher John Mbiti. For Mbiti, ubuntu can be captured by the idea “I am because we are, and since we are, therefore, I am.” Mbiti explained the concept like this:

Only in terms of other people does the individual become conscious of his own being, his own duties, his privileges and responsibilities towards himself and towards other people. When he suffers, he does not suffer alone but with the corporate group; when he rejoices, he rejoices not alone but with his kinsmen, his neighbors and his relatives whether dead or living. [2]

Tutu’s Ubuntu

It is this reading of Ubuntu that became a central peg of Tutu’s own philosophy and theology. And while the idea of Ubuntu had deep roots in Bantu language-speaking communities, it was Tutu more than anyone who popularised the term, and gave it a contemporary religious, ethical, philosophical and political urgency. In his short essay, ‘Ubuntu: On the Nature of Human Community’, Tutu wrote as follows:

IN OUR AFRICAN weltanschauung , our worldview, we have something called ubuntu . In Xhosa, we say, “Umntu ngumtu ngabantu.” This expression is very difficult to render in English, but we could translate it by saying, “A person is a person through other persons.” We need other human beings for us to learn how to be human, for none of us comes fully formed into the world. We would not know how to talk, to walk, to think, to eat as human beings unless we learned how to do these things from other human beings. For us, the solitary human being is a contradiction in terms. Ubuntu is the essence of being human. It speaks of how my humanity is caught up and bound up inextricably with yours. It says, not as Descartes did, “I think, therefore I am” but rather, “I am because I belong.” I need other human beings in order to be human. The completely self-sufficient human being is subhuman. I can be me only if you are fully you. I am because we are, for we are made for togetherness, for family. We are made for complementarity. We are created for a delicate network of relationships, of interdependence with our fellow human beings, with the rest of creation. I have gifts that you don’t have, and you have gifts that I don’t have. We are different in order to know our need of each other. To be human is to be dependent. [3]

Recently, there has been a huge amount of philosophical work on the concept of ubuntu : far more than can be summarised in a short article. But for present purposes, it is worth looking at two aspects of ubuntu : the ontological aspect that asks what it means to be a person, and the ethical aspect that asks how we ought to live in the light of this.

Ubuntu and personhood

The first aspect of ubuntu , then, is a claim about the nature of personhood. For those brought up in cultures that are relatively individualistic, it is easy to imagine that we are born as individuals, unique and distinct, and that we gather together into societies to help meet our individual needs: for company, for connection, for security, for material well-being. In this kind of view, individuals come first. They are logically prior to the societies that they form and the social contracts that they make.

But the notion of ubuntu turns this on its head, reversing this order of priority. First, there is society. And our uniqueness, individuality, and personhood are all born out of this social connectedness. Taking the perspective of ubuntu , it makes no sense to ask about how individuals come together to form societies. We are, all of us, irreducibly bound up in social connections, webs and networks of material dependence, language, myth, story, and imagination. Even if we retire to the mountains to live as hermits, we are still, at root, irreducibly social beings. And being a hermit is not a refusal of society, but instead simply another way of living in relation to society.

This is the ontological claim of ubuntu philosophy. Society is not just an add-on, or an afterthought, or a set of necessary and regrettable compromises. Instead, it is the cradle of our personhood. And this ontological claim seems to me to be plausible–far more plausible, in fact, than the idea that individual personhood comes first. Our being in the world, as the German philosopher Martin Heidegger once put it, is a being-with-others ( Mitsein ).

Ubuntu and ethics

But ubuntu philosophy doesn’t just involve ontological claims. It also involves claims about how we ought to be, given that this is who we are. Here’s Tutu again,

In traditional African society, ubuntu was coveted more than anything else—more than wealth as measured in cattle and the extent of one’s land. Without this quality a prosperous man, even though he might have been a chief, was regarded as someone deserving of pity and even contempt. It was seen as what ultimately distinguished people from animals—the quality of being human and so also humane. Those who had ubuntu were compassionate and gentle, they used their strength on behalf of the weak, and they did not take advantage of others—in short, they cared, treating others as what they were: human beings. If you lacked ubuntu, in a sense you lacked an indispensable ingredient of being human. [4]

For Tutu, if we are indeed interdependent to the very root of our being, this means that we have irreducible obligations to others. But in meeting these irreducible obligations, it is not a question of the trade-off between self-interest and other-interest.

If we conceptualise society as a group of individuals entering a social contract, then to be in society always involves trading in some of our self-interest for the benefits that society may bring. In this view, society always involves a balance of competing interests.

But the idea of ubuntu holds a more radical possibility: the possibility of finding a way of living in society that augments the interests of everyone. This is an idea that goes beyond an ethics of consensus or accommodation, to an idea of mutual flourishing and uplift. And in this way, it offers a challenge to find new and creative forms of political organisation that might serve this mutual flourishing.

Tutu’s own work is a testimony to this. Later, writing about restorative justice and about the horrors of the testimonies gathered by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, he claimed that, “Ubuntu (and so restorative justice) gives up on no one. No one is a totally hopeless and irredeemable case.” Because ultimately, to give up on anyone is to give up on interdependence, and it is to give up on the possibility of community.

And if is something perhaps utopian in this, Tutu’s own example reminds us that it is not an easy or naive utopianism. It is, instead, a robust and tough-minded kind of hope. a determination to find better ways of flourishing as the determinedly, irreducibly social beings that we are.

- Desmond Mpilo Tutu, No Future Without Forgiveness (Doubleday 1999). E-book.

- Quoted in Aloo Osotsi Mojola, ‘Ubuntu in the Christian Theology and Praxis of Archbishop Desmond Tutu, and its Implications for Global Justice and Human Rights,’ in James Ogude, Ubuntu and the Reconstitution of Community (Indiana University Press 2019), chapter 2. E-book

- Desmond Mpilo Tutu, ‘Ubuntu: On the Nature of Human Community’, in God is Not A Christian (Rider 2011). E-book.

Further Reading

A recent and accessible philosophical account of Ubuntu, try the edited collection by James Ogude, Ubuntu and the Reconstitution of Community (Indiana University Press 2019).

For an extraordinary, searing account of the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, read Antjie Krog’s Country of My Skull: Guilt, Sorrow and the Limits of Forgiveness in The new South Africa , published by Three Rivers Press in 2000).

Sign up to my newsletter

You may also like.

Kautilya on the Crooked Business of Politics

The ancient Indian treatise on rulership, and the pragmatics of maintaining power

The Swoop and Surge of Life: Lucretius on Ethics in Motion

Ethics, power and a life in motion.

Lucretius on Chance, Necessity and Free Will

Lucretius, the Roman poet and philosopher, on free will, creativity and the mysterious swerve of an atom.

I am, because of you: Further reading on Ubuntu

Boyd Varty speaks about Ubuntu, and how it can be seen in nature, at TEDWomen 2013. Photo: Kristoffer Heacox

“While it’s true that Africa is a harsh place, I also know it to be a place whose people, animals and ecosystems teach us about a more interconnected world,” says Varty in this emotional talk . “[Nelson] Mandela said often that the gift of prison was the ability to go within and to think, to create within himself the things he most wanted for South Africa: peace, reconciliation, harmony. Through this act of intense open-heartedness, he was to become the embodiment of what in South Africa we call Ubuntu . ‘I am; because of you.’”

Ubuntu is a beautiful — and old — concept. According to Wikipedia, at its most basic, Ubuntu can be translated as “human kindness,” but its meaning is much bigger in scope than that — it embodies the ideas of connection, community, and mutual caring for all. Liberian peace activist Leymah Gbowee ( watch her TED Talk ) once defined using slightly different words than Varty: “I am what I am because of who we all are.”

Interested in hearing more? Check out these sources.

- A (very) brief history of the term . For a great overview of the origins of Ubuntu, check out this article from Media Club South Africa . According to the piece, the first use of the term in print came in 1846 in the book I-Testamente Entsha by HH Hare. However, the word didn’t become popularized until the 1950s, when Jordan Kush Ngubane wrote about it in The African Drum magazine and in his novels. In 1960, the term made another leap as it was used at the South African Institute for Race Relations conference. According to Wikipedia , the concept of Ubuntu transformed into a political ideology in Zimbabwe, as the nation was granted independence from the United Kingdom. From there, in the 1990s, it became a unifying idea in South Africa, as the nation transitioned from apartheid. In fact, the word Ubuntu even appears in South Africa’s Interim Constitution, created in 1993: “There is a need for understanding but not for vengeance, a need for reparation but not for retaliation, a need for ubuntu but not for victimization.” .

- Desmond Tutu’s take . Ubuntu became known in the West largely through the writings of Desmond Tutu, the archbishop of Cape Town who was a leader of the anti-apartheid movement and who won the Nobel Peace Prize for his work. As he approached retirement, Tutu was asked by Mandela to chair South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which sought to come to terms with the human rights offenses of the past in order to move into the future. In his memoir of that time period, No Future Without Forgiveness , Tutu writes, “Ubuntu is very difficult to render into a Western language. It speaks of the very essence of being human. When we want to give high praise to someone we say, ‘Yu, u nobunto’; ‘Hey so-and-so has ubuntu .’ Then you are generous, you are hospitable, you are friendly and caring and compassionate. You share what you have. It is to say, ‘My humanity is inextricably bound up in yours.’ We belong in a bundle of life.” For more analysis of how Ubuntu inspired Tutu, check out the book Reconciliation: The Ubuntu Theology of Desmond Tutu , written by Michael Battle, who studied under the archbishop. .

- Nelson Mandela’s take . In 2006, South African journalist Tim Modise interviewed Mandela and asked him specifically how he defines the concept of Ubuntu . Mandela replies, “In the old days when we were young, a traveller through a country would stop at a village, and he didn’t have to ask for food or water; once he stops, the people give him food, entertain him. That is one aspect of Ubuntu, but it will have various aspects. Ubuntu does not mean that people should not address themselves. The question therefore is, are you going to do so in order to enable the community around you, and enable it to improve? These are important things in life. And if you can do that, you have done something very important.” Watch Modise reflect on Mandela’s death on CBS This Morning . .

- Bill Clinton’s take. Former US President and 2007 TED Prize winner Bill Clinton ( watch his talk ) has embraced the philosophy of Ubuntu in his philanthropic work at the Clinton Foundation. “So Ubuntu — for us it means that the world is too small, our wisdom too limited, our time here too short, to waste any more of it in winning fleeting victories at other people’s expense. We have to now find a way to triumph together,” he said at the Clinton Global Initiative’s annual meeting in 2006. He’s applied these theories to politics as well. At a Labour Party conference in the UK in 2006 , he told the Labour delegates that society and collaboration is important because of Ubuntu. “If we were the most beautiful, the most intelligent, the most wealthy, the most powerful person — and then found all of a sudden that we were alone on the planet, it wouldn’t amount to a hill of beans,” he said. .

- Ubuntu, the operating system . Ubuntu is also the name of “the world’s most popular free OS.” It was named this by South African entrepreneur Mark Shuttleworth, who launched Ubuntu in 2005 to compete with Microsoft. Unbuntu is all about open source development — people are encouraged to improve upon the software so that it continually gets better. According to thi s article in The New York Times from 2009 , “Created just over four years ago, Ubuntu (pronounced oo-BOON-too) has emerged as the fastest-growing and most celebrated version of the Linux operating system, which competes with Windows primarily through its low, low price: $0.” Read up on Ubuntu’s latest release , or check out this list of great Ubuntu apps. .

- Ubuntu in basketball . According to ESPN.com , Ubuntu has had an effect on the NBA. The concept trickled into American professional basketball through Kita Thierry Matungulu, a founder of the South African organization Hoops 4 Hope. In 2002, Matungulu ended up at the same table at a fundraising event with Doc Rivers of the Boston Celtics and introduced him to the concept of Ubuntu. Five years later, Rivers invited Matungulu to speak to his team, and Ubuntu became their rallying call — it was even inscribed in their championship rings in 2008. Most recently, Rivers brought the concept to the Los Angeles Clippers. “Ubuntu works in life. It works for everybody. It doesn’t have to be basketball,” says Rivers. “It’s about being resilient and sharing the joy with your teammate when he’s doing well and feeling the pain when your teammate is feeling bad.” .

- Ubuntu to turn back climate change? Can Ubuntu’s ideas about collectivity be applied to climate change? South African activist Alex Lenferna argues yes. In an essay published today in Think Africa Press, “ What Climate Change Activists Can Learn From Mandela’s Great Legacy ,” Lenferna shares how thinking about our collective humanity could help form a united front of environmentalism. Of Ubuntu, Lenferna writes, “If we accept such a philosophy, then given our knowledge of anthropogenic climate change, our drive to enrich ourselves through the use of greenhouse gas intensive modes of development at the expense of our climate, our planet and the well-being of current and future generations should not be seen as true development but something that violates Ubuntu, diminishes our humanity, and makes us as individuals, nations, and as a global community, less than we could otherwise be.” This idea of Ubuntu inspiring an overhaul of our resource use is gaining traction — it came up at the Climate Change Conference in Durban, South Africa in January of 2012. Could this way of thinking extend across the globe?

- Subscribe to TED Blog by email

Comments (92)

Pingback: The singles of TAM - Page 1582

Pingback: UBUNTU WEAKENED BY MANDELA DAY | YFM

Pingback: Ubuntu - Travels and Tripulations

Pingback: UBUNTU | think authentic

Pingback: Märkamistest.

Pingback: Lions, Tigers And Ubuntu, Oh My! Boyd Varty On The Interconnected World Of … | Matias Vangsnes

Pingback: » Lions, Tigers And Ubuntu, Oh My! Boyd Varty On The Interconnected World Of South Africa

Pingback: Lions, Tigers And Ubuntu, Oh My! Boyd Varty On The Interconnected World Of South Africa - Nice World News

Pingback: Lions, Tigers And Ubuntu, Oh My! Boyd Varty On The Interconnected World Of South Africa | Travel Vacation Dream! Plan your next Vacation

Pingback: Lions, Tigers And Ubuntu, Oh My! Boyd Varty On The Interconnected World Of South Africa – JUANMONEGRO.COM

Pingback: Lions, Tigers And Ubuntu, Oh My! Boyd Varty On The Interconnected World Of South Africa | Political Ration

Pingback: Lions, Tigers And Ubuntu, Oh My! Boyd Varty On The Interconnected World Of South Africa | Noticias de Paraguay

Pingback: Lions, Tigers And Ubuntu, Oh My! Boyd Varty On The Interconnected World Of South Africa | Go to News!

Pingback: Claire Ann Peetz Blog Lions, Tigers And Ubuntu, Oh My! Boyd Varty On The Interconnected World Of South Africa - Claire Ann Peetz Blog

Pingback: Lions, Tigers And Ubuntu, Oh My! Boyd Varty On The Interconnected World Of South Africa | InfoCnxn.com

Pingback: Lions, Tigers And Ubuntu, Oh My! Boyd Varty On The Interconnected World Of South Africa | NewsCenterd

Pingback: Boyd Varty: What I learned from Nelson Mandela | Disorganized Trimmings

Pingback: Remembering A Giant, Today: Nelson Mandela | Racism Is Not A Game

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

And while the idea of Ubuntu had deep roots in Bantu language-speaking communities, it was Tutu more than anyone who popularised the term, and gave it a contemporary religious, ethical, philosophical and political urgency. In his short essay, ‘Ubuntu: On the Nature of Human Community’, Tutu wrote as follows:

Essay About Ubuntu. 1347 Words6 Pages. Ubuntu is commonly described as a way of life, of being, of existing, the plain and simple idea that I am because you are. A Zulu proverb “umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu” clearly describes the world, “a person is a person through people.”. Recently South Africa has been clouded with an atmosphere of ...