Balangaw: Lived Experiences of LGBT Students in the Midst of Pandemic

Pinaga, R. B. (2023). Balangaw: Lived experiences of LGBT students in the midst of Pandemic. Zenodo (CERN European Organization for Nuclear Research). https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8146137

13 Pages Posted: 18 Jul 2023

Rosmar Pinaga

Central philippines state university-candoni campus.

Date Written: July 11, 2023

Gloc-9's song "Sirena" has proved immensely popular and contentious in the Philippines, especially among the LGBT community, which is the song's primary subject matter. This song depicts the experiences of LGBT members starting from childhood up to adulthood by portraying an image of how LGBT people deal with their sexual preferences and how society establishes its perception of LGBT people. Thus, in a conservative and traditional Filipino culture, religious beliefs, cultural standards, norms, and family expectations are the dominant components that impact LGBT individuals' coping with their sexuality. Furthermore, this research employed Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) by Ferrer et al. (2021) to describe the participants' lived experiences, challenges, and coping mechanisms for the darkest experiences of LGBT students amidst this COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, the study's implications were discussed, and recommendations were suggested.

Keywords: LGBT, discrimination, bullying

Suggested Citation: Suggested Citation

Rosmar Pinaga (Contact Author)

Do you have a job opening that you would like to promote on ssrn, paper statistics, related ejournals, social & personality psychology ejournal.

Subscribe to this fee journal for more curated articles on this topic

Other Topics Women's & Gender Studies eJournal

Health psychology ejournal, sociology of gender ejournal, medical & mental health sociology ejournal, pride lgbtqia ejournal.

Subscribe to this journal for more curated articles on this topic

Decoder: How ‘Bakla’ Explains the Struggle for Queer Identity in the Philippines

Create an FP account to save articles to read later.

ALREADY AN FP SUBSCRIBER? LOGIN

World Brief

- Editors’ Picks

- Africa Brief

China Brief

- Latin America Brief

South Asia Brief

Situation report.

- Flash Points

- War in Ukraine

- Israel and Hamas

- U.S.-China competition

- U.S. election 2024

- Biden's foreign policy

- Trade and economics

- Artificial intelligence

- Asia & the Pacific

- Middle East & Africa

How to Defend Europe

How platon photographs power, ones and tooze, foreign policy live.

Spring 2024 Issue

Print Archive

FP Analytics

- In-depth Special Reports

- Issue Briefs

- Power Maps and Interactive Microsites

- FP Simulations & PeaceGames

- Graphics Database

FP at NATO’s 75th Summit

Nato in a new era, fp security forum, fp @ unga79.

By submitting your email, you agree to the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use and to receive email correspondence from us. You may opt out at any time.

Your guide to the most important world stories of the day

Essential analysis of the stories shaping geopolitics on the continent

The latest news, analysis, and data from the country each week

Weekly update on what’s driving U.S. national security policy

Evening roundup with our editors’ favorite stories of the day

One-stop digest of politics, economics, and culture

Weekly update on developments in India and its neighbors

A curated selection of our very best long reads

How ‘Bakla’ Explains the Struggle for Queer Identity in the Philippines

The tagalog word eludes western concepts of gender and sexuality—and offers a window into lgbtq+ filipinos’ quest for acceptance..

- Human Rights

- Southeast Asia

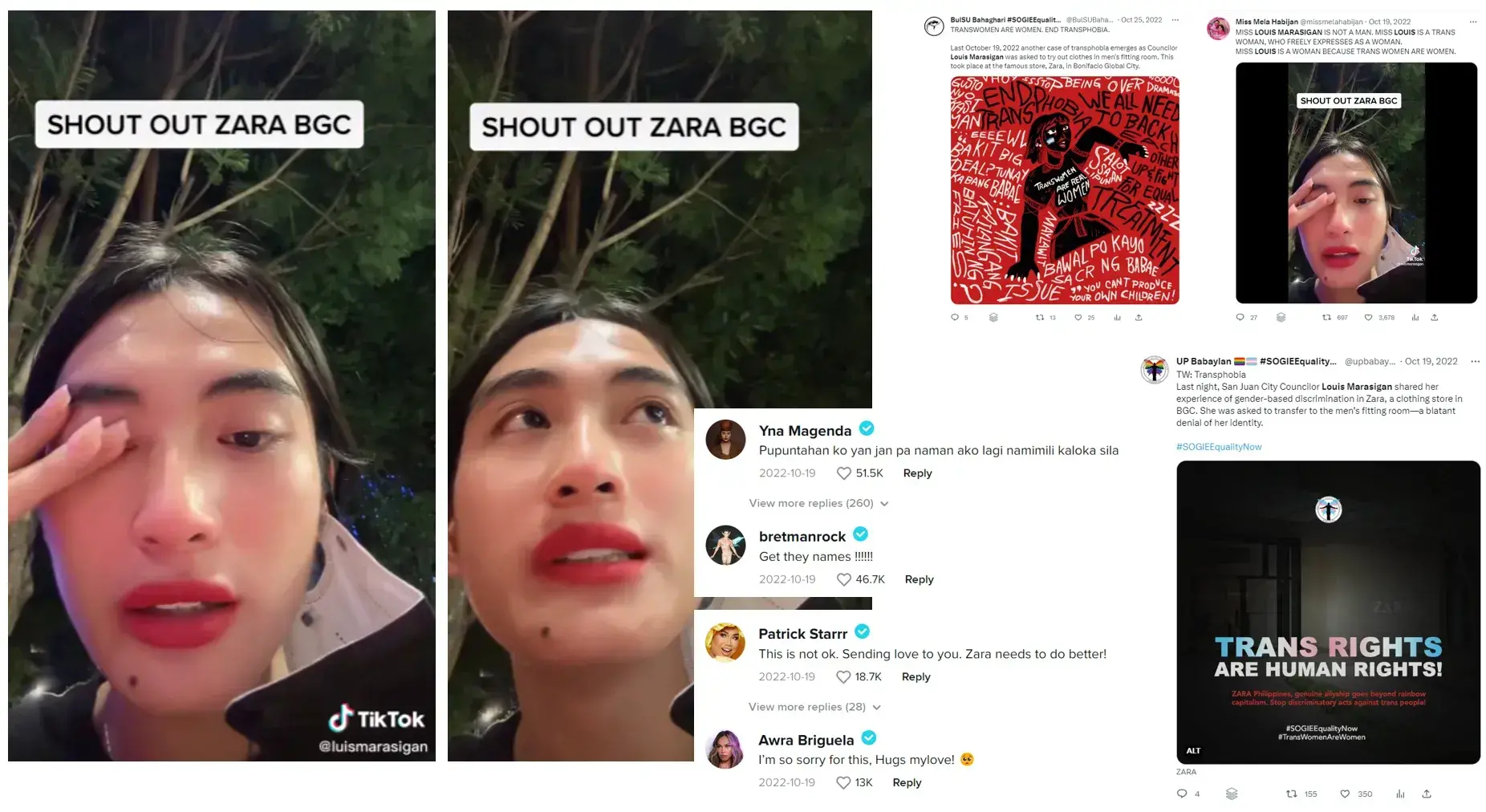

Pride Month in the Philippines this year was decidedly spirited: Emerging from one of the longest COVID-19 lockdowns in the world, tens of thousands of people flocked to events organized by advocacy groups throughout the country to protest abuses against members of the LGBTQ+ and other marginalized communities, stand up for human rights, exchange ideas, watch speeches and performances, provide mutual support, and revel in one another’s company. “Happy Pride, mga bakla !” (“Happy Pride, queers!”) was a common refrain, charged with a celebratory energy that has not always been present for queer Filipinos.

But despite being home to the first Pride March in Asia and some of the largest pride celebrations in the region since, the Philippines has a long way to go in terms of ensuring the safety and dignity of LGBTQ+ Filipinos, who have few legal protections and are often targets of aggression, even brutality . An anti-discrimination bill has languished in the legislature for around two decades. Police periodically conduct raids , without warrants, of venues frequented by queer people, who are then subjected to verbal abuse, extortion, and unlawful detention.

The Tagalog word bakla might be seen as an index of the struggles that LGBTQ+ Filipinos still deal with. Although it serves as a marker of identity and as a potential means of forging community, the term is also burdened by an oppressive past that shapes its unsettled present.

There have been efforts to reclaim bakla from its pejorative past—resembling, to some degree, efforts to transform “queer” from a slur into a badge of affirmation.

Variously translated as “drag queen,” “gay,” “hermaphrodite,” “homosexual,” “queer,” “third sex,” and “transgender,” bakla shows how in the Philippines, as in many places around the world, gender and sexuality are imagined and lived out in connection with concepts and categories that Western lenses can’t fully account for. Even as LGBTQ+ discourse has taken root in the Philippines, providing queer Filipinos and their peers around the world with a shared language to build solidarity with, it is inevitably inflected by local understandings of personhood. In his landmark study of Philippine gay culture, literary critic J. Neil Garcia notes that the defining characteristic of the bakla has been—and, to a large extent, continues to be—effeminacy rather than the object of the bakla’s sexual desire. Thus, bakla refers more to gender than to sexuality. However, in popular usage, it is liable to encapsulate both.

Among Filipinos, bakla likely first conjures up the image of a man who wears clothes and makeup meant for women and is predisposed to flamboyant speech and mannerisms. This figure of the effeminate man has long been present in the Philippines. Documents dating back to the 16th century during Spanish colonization allude to people known as, among other things, “ asog ”: men who assumed the appearance and behavior of women to such a degree that an observer would have difficulty distinguishing between an asog and a woman.

Asog and their ilk throughout the archipelago engaged in what might be most accurately described as gender-crossing. For all practical purposes, they were treated as women, and they married and had sexual relations with men. Like women, asog were well respected in early colonial—and, presumably, pre-colonial—Philippine society. Only women and asog could take on the prestigious role of “ babaylan ,” mediating between the human and the spirit worlds, treating the sick and wounded, and acting as religious and political leaders.

In spite of Filipinos’ subversion, resistance, and hostility, agents of Spanish subjugation endeavored to overhaul Indigenous people’s ways of life. Notably, members of the Catholic clergy branded sexual acts outside of marriage between a man and a woman as sinful and unnatural. Over some 300 years, babaylan lost their spiritual authority to the Catholic Church, women were relegated to the confines of the home or convent, and asog found themselves demeaned by society and ridiculed as bakla.

Some of the definitions for “ bacla ,” an earlier spelling, in an 1860 Tagalog-Castilian dictionary are telling: to beguile or deceive with luster or beauty, to heal with feigned words, and to be frightened of a new thing. In Tagalog writings from the 19th century up to before World War II, bakla signified a passing phase of confusion, cowardice, fear, indecision, or weakness. Although the word is no longer used in these ways, bakla still bristles with a host of negative connotations, especially following its conflation with the (male) homosexual. Following Garcia’s account, this conflation can be traced back to around the turn of the 20th century, when the United States acquired the Philippines from Spain and imposed new modes of thought about gender and sexuality—such as the concept of homosexuality and its pathologization as a disorder.

A Filipino protester holds up a painted sign at dusk that reads “ Fight 4 Intersectional LGBTQ+ ” during a Pride parade and protest in Manila, Philippines, on June 28. Jes Aznar/Getty Images

Thus, it is not surprising that bakla today is still used as an insult. Former Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, notorious for his penchant for violence, has denounced several of his critics as bakla, from a rival candidate for president to the chairperson of the Commission on Human Rights to the U.S. ambassador to the Philippines . Duterte has also remarked on a number of occasions that he used to be bakla but “ nagamot ko ang sarili ko ” (“I cured myself”)—giving voice to the conventional belief in the country that being bakla is similar to having a disease.

This stigma manifests in other forms. Consider how the relationship between two celebrities, comedian Vice Ganda and model Ion Perez, has played out in the public eye. Ganda has referred to herself as bakla and nonbinary, with no pronoun preferences. Perez has described himself as a straight man and responded with anger when tagged as bakla. In 2021, to mark their third anniversary as a couple, the two underwent a commitment ceremony in Las Vegas. Regardless of their open expressions of love, Vice and Perez have had to weather persistent rumors that Perez is just bilking his wealthier and more famous partner. It is a common stereotype that the bakla must purchase the affections of a man and will be abandoned once the bakla has been drained of funds or the man has fallen in love with a woman.

There has been a variety of responses to bakla and its adverse history from the people it purports to designate, such as other members of the LGBTQ+ community and their allies, from adaptation to rehabilitation to rejection. These responses are nuanced by factors like socioeconomic status, geographical location, and access to information on developments in such fields as human rights, law, mass media, medicine, psychology, and public health—and how these bear on gender and sexuality.

Bakla is used matter-of-factly as a self-descriptor and between bakla and their friends as a greeting or a term of endearment. Diminutives, such as “ baks ” and “ accla ,” proliferate, as do alternatives like “ badaf ” and “ bading ,” which are seen as less demeaning. The English words “gay” and “queer” are also in use; these must be understood in connection with long-standing inequalities in Philippine society, in that bakla tends to indicate a person of lower class and status, usually caricatured as a swishy beauty parlor worker. (Many bakla pursue careers in the beauty, fashion, or entertainment industries.)

The Connection Between LGBTQ Rights and Democracy

Inside the worldwide fight for equality.

Maria Ressa Wants to Save Journalism

The Filipino American journalist and Nobel laureate explains what it’s like to be a government target—and how to safeguard a free press.

Transgender women, meanwhile, have sought to endow their existence with greater precision than bakla affords, with a group of advocates coining the term “transpinay”—a portmanteau of “transgender” and “Pinay,” the latter an informal word for “Filipino woman”—in 2008.

Moreover, there have been efforts to reclaim bakla from its pejorative past—resembling, to some degree, efforts to transform “queer” from a slur into a badge of affirmation. In the 1980s, gay and lesbian activists set up a group named BANANA, which stood for Baklang Nagkakaisa Tungo sa Nasyonalismo (“Bakla United Toward Nationalism”), and participated in protests against the government. In the 1990s, an LGBTQ+ student organization based in the state-run University of the Philippines, called UP Babaylan—a homage to the pre-colonial shaman—produced T-shirts for its members that said “ Bakla ako ” (“I’m bakla”) on the front and “ May angal ka ?” (“Any objections?”) on the back.

A watershed moment in the 2000s was the founding of Ang Ladlad, an LGBTQ+ party that sought to influence national politics by fielding candidates to run under the Philippines’ party-list system, designed to facilitate representation of marginalized sectors in Congress. It faced several challenges —including a ban, later overturned, on its participation in the 2010 elections owing to its alleged promotion of immorality—and was ultimately unsuccessful at its bids to win legislative seats, but it helped draw attention to LGBTQ+ issues and suggest the prospect of the “pink vote”: that is, LGBTQ+ people as a key voting bloc, though its power is yet to be demonstrated. One of the more interesting vote-gathering tactics of Ang Ladlad was to visit neighborhood beauty parlors and engage with the bakla employed there.

Various LGBTQ+ groups continue to play on bakla in their slogans and taglines as they stand up for their rights. The coalition Bahaghari often uses “ Makibeki, wag mashokot !” as a rallying cry. “ Makibeki ” combines “ makibaka ” (“contend with us”) and “ beki ” (another diminutive of bakla) while “‘ wag mashokot ” means “have no fear” in gay lingo. The organizers of the Metro Manila Pride Parade also used makibeki as part of this year’s march theme: “ Atin Ang Kulayaan! Makibeki Ngayon, Atin Ang Panahon .” A rough translation would be, “The colors of freedom are ours! Fellow queers, let us fight together. It is our time.”

These, it must be emphasized, are not merely linguistic maneuvers. Rather, they represent individual and collective efforts from people who have long been disdained for being different, for defying the norm, to make themselves felt and heard, specify their experiences, and inaugurate modes of living and loving together. Even as the use of bakla remains contentious, LGBTQ+ Filipinos sustain their attempts to negotiate with its difficult history and pave the way toward a prismatic future where they will be embraced with full acceptance by their families and communities.

Jaime Oscar M. Salazar is a writer who lives in Pasig, Philippines.

Join the Conversation

Commenting on this and other recent articles is just one benefit of a Foreign Policy subscription.

Already a subscriber? Log In .

Subscribe Subscribe

View Comments

Join the conversation on this and other recent Foreign Policy articles when you subscribe now.

Not your account? Log out

Please follow our comment guidelines , stay on topic, and be civil, courteous, and respectful of others’ beliefs.

Change your username:

I agree to abide by FP’s comment guidelines . (Required)

Confirm your username to get started.

The default username below has been generated using the first name and last initial on your FP subscriber account. Usernames may be updated at any time and must not contain inappropriate or offensive language.

Sign up for Editors' Picks

A curated selection of fp’s must-read stories..

You’re on the list! More ways to stay updated on global news:

Iranians Go to the Polls to Elect a New President

Is it too late to replace a presidential candidate, how the world is reacting to the u.s. presidential debate, what in the world, what will elections in france, iran, and the u.k. mean for u.s. foreign policy, editors’ picks.

- 1 The Deep Roots of Kenya’s Unrest

- 2 Key Foreign-Policy Moments From the Trump-Biden Debate

- 3 Yes, Biden Flopped. But Let’s Not Overreact.

- 4 How the World Is Reacting to the U.S. Presidential Debate

Iran Presidential Election: Voters Choose the Late Raisi's Replacement

Trump-biden debate: is it too late to replace a presidential candidate, world reacts to the u.s. presidential debate, the eu plays hardball and kenyan protests: foreign policy's weekly international news quiz, will elections in france, iran, u.k. impact u.s. foreign policy, more from foreign policy, nato’s new leader was planning this the whole time.

Mark Rutte, a workaholic obsessed with routine, is about to take over the West’s military alliance.

What the United States Can Learn From China

Amid China’s rise, Americans should ask what Beijing is doing right—and what they’re doing wrong.

What a War Between Israel and Hezbollah Might Look Like

The Lebanese armed group is trained and equipped much better than Hamas.

The Hidden Critique of U.S. Foreign Policy in ‘Red Dawn’

Forty years ago, Hollywood released a hit movie with a surprisingly subversive message.

The Deep Roots of Kenya’s Unrest

Yes, biden flopped. but let’s not overreact. , key foreign-policy moments from the trump-biden debate, why are french jews supporting the far right, how kenya’s president broke the social contract, the biden-trump presidential debate.

Sign up for World Brief

FP’s flagship evening newsletter guiding you through the most important world stories of the day, written by Alexandra Sharp . Delivered weekdays.

- Subscribe Newsletter

- Track Paper

- Conferences

International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science (IJRISS)

- ISSN No. 2454-6186

- Strengthening Social Sciences for the Future

- June Issue 2024

- Research Area

- Initial Submission

- Revised Manuscript Submission

- Final Submission

- Review Process

- Paper Format

- Author (s) Declaration

- Registration

- Virtual Library

- Apply as Reviewer

- Join as a Board Member

- Eligibility Details & Benefits

- Board Members

Understanding the Challenges Faced by Filipino LGBTQ+ Individuals with Strong Religious Ties

- Timothy John DC. Libiran

- Rowie Lawrence C. Cepeda

- Camille Krisandrea M. Ramos

- John Carlo O. Alano

- Michael Jo S. Guballa

- Feb 23, 2024

Timothy John DC. Libiran 1 , Rowie Lawrence C. Cepeda 2 , Camille Krisandrea M. Ramos 3 , John Carlo O. Alano 4 , Michael Jo S. Guballa 5

School of Education, Arts, and Sciences, Department of Psychology, National University Philippines- Bulacan

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.47772/IJRISS.2024.801186

Received: 07 January 2024; Revised: 19 January 2024; Accepted: 23 January 2024; Published: 23 February 2024

The Philippines is renowned for its deep religiosity, providing hope and support to its citizens. However, this religiosity presents a paradox, as some church teachings openly oppress and stigmatize LGBTQ+ individuals, branding homosexuality as morally wrong. This study explored the complex conflicts experienced by LGBTQ+ Filipinos with strong religious ties and how their faith either supports or exacerbates their challenges. Prior research consistently shows that LGBTQ+ encounter discrimination and degradation within their religious communities, driven by unjust treatment. Employing a phenomenological qualitative approach with in-depth interviews, this study examines Filipino LGBTQ+ individuals aged 18 and above. The findings unveil the multifaceted conflicts participants face, notably inequitable and oppressive treatment within their religious communities. Ecclesiastical dilemmas emerge, primarily due to discrimination, humiliation, and exclusion from the church and its members, stemming from flawed teachings categorizing LGBTQ+ individuals as morally wrong. Perceptions of support from their religion reveal a dual nature. Participants find positive support within their faith, receiving solace from select individuals who encourage focusing on the positive aspects of their religious experience. Conversely, they report negative effects from the church’s problematic teachings, leading to isolation and a lack of support that significantly impacts their well-being. This study contributes to understanding the challenges faced by LGBTQ+ individuals, especially within religious contexts, emphasizing the need for increased awareness and correction of misguided beliefs and teachings. The research strives to create a more inclusive and safer environment for all individuals, irrespective of gender or identity, fostering a more accepting and understanding society.

Keywords— LGBTQ+, Oppression, Discrimination, Humiliation, Degradation.

INTRODUCTION

Since Spanish colonialism, the Philippines has been considered one of the most religious countries in the world, which explains why there are a range of beliefs and conventions mentioned in the bible that are still in use today. The majority of Filipinos have strong religious beliefs and affiliations. In the early stages of discovering and embracing their same-sex desire, homosexuals experienced unpleasant feelings such as perplexity, rage, denial, and self-loathing. They faced church discrimination and prejudice, which led to feelings of isolation; they questioned church teachings and Bible interpretation, viewing it as oppressive and untrustworthy: the emotional journey and challenges faced by Christian homosexual individuals in accepting their sexual orientation [39].

Accordingly, by recognizing the importance of authenticity and self-acceptance, individuals came to the realization that their sexual orientation is a personal matter that concerns their relationship with a higher power. In addition, LGBTQ+ members did not perceive their sexuality as deviant or morally wrong as opposed to what the church believed to be, so they did not have an obligation to compromise the conflicting notions of homosexuality and Christianity [39]. Moreover, the decision to discontinue their faith negatively affected the individuals’ connection with their spiritual beliefs, as they experienced a sense of emptiness that resulted in a greater distance from their perception of the divine [10].

Being an LGBTQ+ member and having a strong belief in god comes with substantial consequences living in an extremely religious country, such as discrimination, exclusion, and prejudice as being a sinner among traditional people. In addition, these LGBTQ+ individual are still able to maintain their strong ties with their religion despite the adversities they experienced from it. Moreover, even up to this moment, many religious groups have avoided or condemned homosexuality, labeling it as morally wrong or sinful. Regrettably, this stance has left numerous LGBTQ+ individuals feeling excluded, rejected, and marginalized within their faith communities [13]. Accordingly, Filipino LGBTQ+ individuals with strong religious ties represent a unique and often marginalized segment of society whose experiences and challenges remain inadequately explored and understood. This research endeavors to shed light on the multifaceted issues and concerns that this population confronts at the intersection of their sexual and gender identities and their deep religious affiliations. It is imperative to recognize that while the Philippines is a predominantly Catholic country, the LGBTQ+ community within this context grapples with the complexities arising from deeply rooted religious traditions, doctrines, and societal expectations. This study seeks to unravel the intricate dynamics that affect the lives of LGBTQ+ individuals who grapple with the tension between their authentic selves and their religious convictions. By delving into these experiences, the researcher aims to provide valuable insights into the challenges faced by this community, foster empathy, and promote more inclusive and affirming environments within religious communities and society. In line with this,

This qualitative study explores how spirituality serves as a source of resilience and support in terms of well-being for LGBTQ+ individuals, delving into their experiences dealing with discrimination within their religious communities while staying connected to their faith. It aims to understand the struggles of LGBTQ+ people with strong religious ties, shedding light on religious conflicts and LGBTQ+ experiences in the Philippines.

Lastly, this study seeks to contribute to our understanding of the challenges faced by LGBTQ+ individuals with strong religious ties, shedding light on their unique experiences and providing insights for future research. Also included is a comprehensive manual on how diverse religious organizations should reevaluate and change their doctrines and societal standards in response to LGBTQ+ people who, despite prejudice, remain steadfast in their faith. To reorient traditional religious believers about the lack of a link between sexual identity and religion. It attempts to combat biases, educate religious leaders, and provide LGBTQ+ mental health solutions. This study may foster a more inclusive culture where religious beliefs and LGBTQ+ identities can coexist by illuminating these issues.

In the Philippines, LGBTQ+ individuals, including those who identify as Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, and others with diverse sexual orientations and gender identities, face unique healthcare needs. These needs are shaped by cultural and religious beliefs prevalent in the country. The predominantly Catholic environment influenced societal norms, impacting how LGBTQ+ individuals are accepted and supported. This diverse group encompassed various identities, each facing specific healthcare disparities. [15] conducted a detailed examination of LGBTQ+ healthcare research priorities, highlighting crucial areas such as health services delivery, prevention, and challenges related to intersectionality. Health services delivery aims to ensure inclusive, high-quality, and accessible healthcare. Prevention strategies focus on enhancing overall health and preventing illnesses. The concept of Challenges and Intersectionality acknowledges the intricate interconnections between gender identity, sexual orientation, and other societal factors affecting LGBTQ+ lives.

In the Philippines, the intersection of LGBTQ+ identities with religious beliefs poses significant challenges. Religious teachings often clash with LGBTQ+ acceptance, impacting self-acceptance and mental well-being. Balancing gender identity or sexual orientation with religious beliefs became a complex struggle. Filipino LGBTQ+ individuals navigated cultural norms, family dynamics, and religious communities, shaping their experiences and acceptance within this intricate web. [15] research emphasized the urgency of addressing healthcare disparities in LGBTQ+ communities, especially within religious settings. Prioritizing issues such as intersectionality, prevention, and health services delivery are essential when creating evidence-based interventions in favor of LGBTQ+ individuals in religious contexts. To create comprehensive and culturally sensitive support systems, it is vital to understand the diverse identities and challenges faced by the LGBTQ+ population in the Philippines. Combining insights from [15] research with the struggles experienced by LGBTQ+ Filipinos in religious environments, this review provides a deep understanding of LGBTQ+ identities and healthcare inequalities. Religious groups in the Philippines must promote acceptance and inclusivity for LGBTQ+ individuals through culturally sensitive relationships, counseling services, and educational programs.

Filipino LGBTQ+

Tang and Poudel (2018) illustrated the challenges LGBT people face in the Philippines, stressing the significance of family acceptance in Filipino culture. In a culture where family ties are highly valued, family acceptance has an essential function in determining the mental health and general well-being of young LGBT people. The study focused on cases of interpersonal rejection, which presented significant challenges to the individuals’ spiritual and religious identities in addition to causing emotions of isolation and poor self-worth. When these difficulties are combined with the study conducted by [12], a deeper understanding of the emotional contexts that LGBT people in the Philippines navigate while exploring their religious experiences is presented. Filipino LGBTQ+ people’s feelings of generosity, hope, and guilt concerning God were investigated by [12]. The study demonstrated the complexity of religious experiences by showing that, although feelings of gratitude and optimism were common, guilt also had a major influence on how LGBTQ+ people identified as religious. The intersection of religious teachings and LGBT identities becomes a source of interaction and struggle in the context of Filipino views, where religion often serves as the foundation of cultural identity.

A fine balance between religion and self-acceptance is required because of the conflict between strong religious views and various sexual orientations and gender identities. According to [49], family acceptance became crucial for both one’s well-being and one’s ability to balance one’s religious views with one’s LGBT identity. Recognizing these difficulties in Filipino values is important, emphasizing the necessity of inclusive discussions within religious groups. It highlighted how important it is to promote tolerance, acceptance, and understanding so that people may enjoy their LGBT identities without worrying about being judged or rejected. To address these issues, religious leaders and communities must have discussions that encourage love and acceptance for every member, irrespective of that member’s gender identity or sexual orientation. Society can make great progress in fostering an atmosphere that is more accepting and encouraging for the LGBT community in the Philippines by recognizing and appreciating the diversity of identities within the structure of Filipino values.

Strong Religious Ties

Strong religious beliefs can have diverse foundations influenced by a person’s religious position, culture, and personal values. Studies suggest that subjective well-being (SWB) can experience a positive impact in societies with high religiosity, although research on the relationship between spirituality, religion, and SWB presents conflicting results. Notably, significant signs of religious commitment, such as the value of religion in people’s lives, belief in God, frequency of prayer, and attendance at worship services, can shape social and political attitudes within religious traditions. Concurrently, religious beliefs may exert both positive and negative effects on health, with negative religious coping involving spiritual struggles [53]. Understanding religious commitment involves considering factors like the importance of religion, belief in God, regularity of prayer, and attendance at worship services, which collectively shape social and political views within religious traditions. Additionally, religious affiliation significantly impacts life satisfaction, with religiously affiliated individuals reporting higher levels of contentment [39]. These dynamics take on unique nuances in the Philippines, where a rich cultural background intersects with strong religious affiliations. To comprehend the Filipino viewpoint on religion and its relationship to well-being, it is crucial to grasp the cultural details influencing these ideas. Transitioning to a broader psychological perspective, a psychologist with over 20 years of experience studying human motivation proposes that individuals are drawn to religion because it satisfies sixteen fundamental human needs. This psychological perspective sheds light on the observed dynamics, particularly within the context of Filipino beliefs, which acquire unique nuances when viewed through their cultural lens. In summary, the foundation of strong religious belief connections is a complex interplay of culture, personal values, and the fulfillment of basic human desires. This complexity is further emphasized when examining the specific context of Filipino beliefs, where a rich cultural background intersects with strong religious affiliations. Understanding the relationship of cultural details that shape these ideas is essential to comprehending the Filipino viewpoint on religion and its relationship to well-being.

Conflicting Belief System

The studies by [4], [47]-[5] provide crucial insights into the complex relationship between religious affiliation, LGBTQ+ identity, and mental health outcomes. According to [4] research, it suggests that lower religious affiliation among LGB individuals may act as a protective factor against discrimination’s negative consequences, potentially due to reduced exposure to condemning religious teachings. Conversely, [47] study sheds light on the profound harm inflicted by certain religious communities on LGBTQ+ individuals, emphasizing the emotional and psychological damage experienced across age groups. These disparities highlight the need to recognize the resilience of some LGBTQ+ individuals due to lower religious affiliation while acknowledging the ongoing harm within certain religious traditions.

Also, [51] study further adds to this discourse by identifying a significant issue with negative attitudes towards LGBTQ+ individuals among healthcare and social work professionals with religious affiliations in the UK, especially among Christian and Muslim practitioners. These attitudes raise concerns about the impact on LGBTQ+ individuals’ access to healthcare and social services and the potential for discrimination and stigma. In contrast, [38] study found that increased Catholic homogeneity at the county level was associated with less resistance to LGBTQ+ individuals, indicating that the influence of religious attitudes on LGBTQ+ acceptance may vary depending on specific religious and moral communities. These findings highlight the intricate relationship between religion, LGBTQ+ identity, and societal attitudes.

Spiritual Struggles

According to [18] and [52], research on LGBTQ+ individuals within religious contexts presents a compelling argument about the reconciliation of sexuality and faith. Dupree’s study highlights a strong desire for reconciliation among LGBTQ+ Christians who actively seek ways to harmonize their faith with their sexuality. They emphasize the importance of nuanced biblical study and historical context to challenge discriminatory beliefs, promoting inclusivity. This demonstrates the potential for change within religious communities.

In contrast, [52] reveals the initial rejection of sexuality by devoutly religious LGBTQ+ individuals, leading to negative consequences like depressive symptoms and substance abuse. This prompts the rejection of organized religious affiliation in favor of self-identity and sexual orientation acceptance. This divergence in approaches underscores the complexity of the religion-LGBTQ+ intersection. It calls for more inclusive religious communities and highlights the importance of prioritizing mental well-being when facing religious discrimination. Ultimately, these findings contribute to the ongoing dialogue about faith and sexuality reconciliation.

Social Relationship

The differing findings from [20] and [34] studies regarding the interplay of religion, LGBTQ+ acceptance within families, and the impact on LGBTQ+ well-being fuel a complex argument. [20] research highlights the use of religious tools by family members of gay men to mediate post-coming-out conflicts, revealing the potential for religious beliefs to aid conflict resolution within families. The study also shows that acceptance of LGBTQ+ individuals within religious contexts can vary in difficulty among parents.

In contrast, family acceptance significantly benefits LGBTQ+ youth’s mental well-being, irrespective of religious background. Their findings challenge the assumption that religious beliefs inherently lead to lower acceptance and suggest that families can provide support within religious settings, even if these are not explicitly affirming [34]. This underscores the nuanced relationship between religion, family acceptance, and LGBTQ+ well-being, calling for a more comprehensive understanding of how these factors intersect. Some families may use religious tools for reconciliation, while others can offer support within religious contexts. This argument highlights the need for a more inclusive and open dialogue about faith and LGBTQ+ acceptance within families, recognizing the potential for positive change and support within various religious contexts.

Mental Health Implications

The diverse findings from studies examining the interplay between religion, LGBTQ+ identity, and mental health present an intricate argument concerning the complex relationship between religious experiences and the mental well-being of LGBTQ+ individuals. On one hand, the systematic review by [25] underscores the negative impact of religious trauma on the mental health of LGBTQ+ individuals. Experiences such as spiritual abuse were consistently associated with higher levels of depression, anxiety, and psychological distress. This highlights the significant harm that certain religious environments can inflict on the mental well-being of LGBTQ+ individuals. The critical role of supportive family, social, and religious networks in mitigating these negative effects emphasizes the importance of a strong support system. [24] research further emphasizes the prevalence of adverse religious experiences (AREs) among LGBTQ+ individuals raised in authoritarian religious environments. The majority of participants reported experiencing AREs, which were strongly correlated with negative or disaffirming LGBTQ+ beliefs within religious contexts. Qualitative insights provided a nuanced understanding of the psychological and social impacts of these experiences, including feelings of anxiety, fear, guilt, and isolation.

In addition, the fight for LGBTQ+ rights have made significant progress, but challenges persist, particularly in the realms of healthcare access, employment and housing discrimination, violence, becoming parents, and social exclusion. LGBTQ+ individuals often face elevated rates of mental health issues due to oppressive structures. Healthcare access remains a concern, with disparities in mental health and substance abuse treatment, as well as difficulties in finding affirming care. Employment and housing discrimination persist, with legal protections inadequately enforced. Violence against LGBTQ+ individuals, including hate crimes and intimate partner violence, is prevalent, compounded by distrust of the justice system. LGBTQ+ individuals pursuing parenthood encounter discrimination and financial obstacles. Social exclusion, including familial rejection, conversion therapy, and community ostracization, contributes to mental health challenges and elevated suicide rates. Mental health professionals are crucial in addressing these issues and providing affirming care [28].

However, it is essential to consider the contrasting perspective presented by [53], which suggests that religiosity can have a protective effect on mental health, including a lower likelihood of developing depression over time. This viewpoint emphasizes that, in the general population, religious engagement is associated with better mental health outcomes, potentially conflicting with the above-mentioned findings concerning LGBTQ+ individuals.

This dichotomy in findings prompts a thought-provoking argument about the complex and nuanced nature of the relationship between religion, LGBTQ+ identity, and mental health. While some LGBTQ+ individuals may find support and solace in religious engagement, others may experience adverse religious experiences that lead to significant mental health challenges. The varying impacts of religion on mental health underscore the need for a more comprehensive understanding of the intersection between faith and LGBTQ+ well-being.

Ultimately, the argument calls for an inclusive and respectful dialogue that acknowledges the diverse experiences of LGBTQ+ individuals within religious contexts. It highlights the importance of both supporting LGBTQ+ individuals who may face religious trauma and recognizing that, for some, religion can serve as a protective factor for their mental health. It is crucial to strike a balance that respects individual beliefs and experiences while working towards greater inclusivity and understanding within religious communities. The interplay among religion, LGBTQ+ identity, and mental health is far from straightforward. Research demonstrates that while religious trauma can negatively affect the mental well-being of LGBTQ+ individuals, religion may act as a protective factor for mental health in other contexts. This complexity necessitates a nuanced and inclusive approach that acknowledges the diversity of experiences within religious communities. It is essential to provide support to individuals impacted by religious trauma while also recognizing the potential positive role of religion in promoting mental well-being. Such an approach can increase inclusivity and understanding within religious communities, benefiting all individuals involved.

Synthesis

All the aforementioned studies provide essential concepts concerning the challenges faced by LGBTQ+ individuals with strong religious ties. Accordingly, lower religious affiliation while having strong spiritual beliefs leads to lesser feelings of guilt and mental health problems ([4]-[54]). On the other hand, religious institutions and their members still apply the doctrines that being LGBTQ+ is morally wrong and a sin towards God which negatively affects them externally, such as exclusion and rejection, and mentally and internally, such as feelings of shame and guilt ([47], [5], [51], [55], [18], [52], [25]-[24]. Moreover, LGBTQ+ members reconcile their sexual identity and strong religious affiliations via praying, therapy, and seeking support from other religious institutions that accept their sexuality ([47]-[55]). Inversely, according to [52], and [18], individuals tried to suppress and reject their real sexuality as they perceived that it was wrong and not accepted by the church and the people around them, as well as to maintain their strong religious affiliations without any conflict of discrimination and rejections. However, they have feelings of guilt and anxiety. Furthermore, family acceptance of highly religious parents greatly impacts positive and negative results in terms of improving mental well-being and connection of their religion since they are deemed to be the source of resilience and support of LGBTQ+ members in a world full of discrimination and rejection towards them ([20], [34]).

The above results have made valuable contributions to understanding LGBTQ+ individuals within religious contexts, but several crucial gaps still exist. Firstly, there is a gap related to the geographic focus of previous studies, which have predominantly concentrated on Westernized settings. To address this gap, the researchers intend to investigate the variables within the context of the Philippines. This geographical focus is essential because it recognizes the importance of understanding the unique challenges and dynamics faced by LGBTQ+ individuals in a religious context within the Philippines, a highly religious country.

The core research gap in this study pertains to the varying experiences of LGBTQ+ individuals within religious contexts. While some studies suggest that lower religious affiliations may protect against discrimination, others emphasize the harm inflicted by specific religious communities. This discrepancy underscores the need for more comprehensive investigations into the factors contributing to resilience or harm within religious settings.

Furthermore, there’s a data gap that necessitates further research into the long-term effects of religious beliefs on the mental health of LGBTQ+ individuals and the underlying mechanisms at play. This gap extends to understanding the specific sources of conflicts experienced by these individuals within the context of the highly religious country, the Philippines. Addressing these gaps will provide a more thorough understanding of the complex interplay between religion, LGBTQ+ identity, and mental health within this specific cultural context, offering valuable insights for both researchers and practitioners.

Statement of the Problem

This study addresses the challenges experienced by LGBTQ+ individuals with strong religious relationships. Despite the country’s predominantly Catholic background, LGBTQ+ individuals often grapple with the conflict between their sexual and gender identities and deeply rooted religious traditions. The study aims to shed light on these multifaceted issues by delving into the emotional journeys and experiences of Christian homosexuals as they navigate self-discovery and acceptance. It also seeks to promote empathy and inclusivity within religious communities and society. The research also provides insights for future interventions, including revaluating religious doctrines and standards to accommodate LGBTQ+ individuals. Ultimately, this qualitative study explores how spirituality can serve as a source of resilience for LGBTQ+ individuals and the challenges experienced by coexisting their identities with their strong religious bond, contributing to a more oriented and inclusive culture. With that, the following questions are aimed to be answered by this research study.

What are the multifaceted challenges experienced by Filipino LGBTQ+ individuals who maintain strong religious affiliations towards their sexual orientation and gender identity?

Specific Questions:

- What are the main sources of tension or conflict experienced by Filipino LGBTQ+ individuals in reconciling their sexual orientation and religious beliefs?

- How do Filipino LGBTQ+ individuals with strong religious ties perceive their religion as a source of support and resilience regarding their well-being?

Research Design

This research utilized a phenomenological qualitative design to explore a phenomenon without preconceived notions. It focuses on understanding the nature of occurrences in individuals’ lives by examining daily experiences while valuing the richness and depth of data over quantity. Unlike quantitative research, this study prioritized descriptive rather than numerical data [23]. In addition, it utilized in-depth interviews since they are deemed a valuable research method for obtaining comprehensive insights into an individual’s beliefs and actions and delving deeply into novel topics. Interviews were then frequently employed to contextualize additional data, such as outcome data, thus enhancing the comprehensiveness of the topic’s understanding and rationale [8].

Participants

Participants were recruited through purposive sampling, ensuring diverse religious backgrounds, gender identities, and sexual orientations. It enables the researcher to obtain in-depth data on specific subjects or problems that interest them. It will also be possible to apply it in investigations on a smaller scale and with a smaller sample size [41]. A total of 7 participants, coming from a variety of religious LGBTQ+ community members, were chosen for this study. According to [14], it is recommended to have between 3 and 10 participants for a phenomenological investigation. In addition, based on the mathematical model established by Jakob Nielsen and Tom Lindauer, 5 participants will be enough to conduct a qualitative study since it will represent 85% of the issue being studied as well as 5 participants is substantial enough to start the study since no specific number of participants can answer all specific questions, especially in a qualitative study where in the quality of data will be more preferred than the quantity and will provide the perfect saturation to represent the study. Hence, five (5) will be best to represent the study, then add more after determining the limitations and include it in the recommendations [9].

However, according to [11], the number of participants necessary in a qualitative interview might vary based on the subject of the investigation, the amount of thematic saturation (when fresh information or themes cease emerging), and the unique study methodology. No set number of participants is needed for qualitative interviews because the emphasis is on data depth and richness rather than statistical representativeness.

Accordingly, the Inclusion of participants will be LGBTQ+ members who are active part of any religious groups or institutions. These participants attend mass regularly (e.g., every week), mainly communicate with God through prayer daily, and have a position in their religious institutions. This will allow richer information required by the questions in this research study since individuals 18 years old and above might have stronger religious ties and experience regarding their religion and gender. Moreover, the exclusion of participants is those who are active LGBTQ+ members in their religion who are under the age of 18 years old. LGBTQ+ individuals with strong religious ties below 18 years old might still be vulnerable and sensitive about the questions and topic, especially when their gender and religion are involved as well, and they may not have adequate experience with the variables being studied.

Table. I This Section Discusses the Demographic Profile of LGBTQ+ Individuals with Strong Religious Ties who Participated in this Study.

| 18-20 | 2 | 28.57 | 7 | |

| 21-22 | 5 | 71.43 | ||

| Male | 4 | 57.14 | ||

| Female | 3 | 42.86 | ||

| Iglesia ni Cristo | 1 | 14.29 | ||

| Christian | 2 | 28.57 | ||

| Roman Catholic | 4 | 57.14 |

Table I shows a total of N=7 participants included in this study. The participants come from three religions, which are Iglesia ni Cristo (n=1), Christian (n=2), and Roman Catholic (n=4). In addition, participants’ ages range from 18-20 years old (n=2) and 21-22 years old (n=5). It comprised male (n=4) and female participants (n=3).

Instruments

In this qualitative study, the researchers employed semi-structured open-ended questions. This method of questioning allowed the participants to share their subjective experiences and perceptions towards the questions being asked in their own words, which can provide more in-depth information about the topic since the question cannot be answered by a simple yes or no [14]. The researchers prepared the semi-structured open-ended questions interview guide, which was then validated by three (3) research professionals mastering the field of qualitative research to ensure that the set of questions is well structured to the aim of the study and to obtain the proper and rich data for the present study. Moreover, the researchers used audio and video recording and note-taking to transcribe the conversation and vital information delivered by the participants to be used in thematic analysis. Lastly, the duration of the interview lasts for about 20-30 minutes per participant to ensure that all the necessary questions will be asked to the participants and to have an ample amount of time for any clarification, addition, and revision of the answers given by the participants of the study.

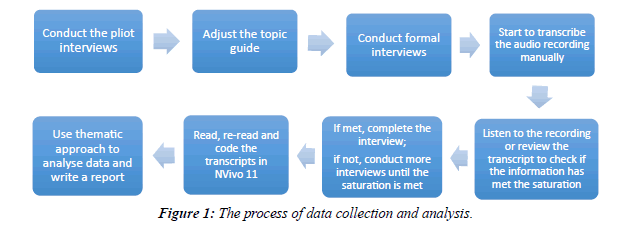

Data Gathering Procedure

The primary objective of this study is to investigate the lived experiences of LGBTQ+ individuals within religious settings, with a specific emphasis on the intersectionality of their sexual orientation and strong religious affiliations. Gaining a comprehensive understanding of these experiences through qualitative methods is crucial in fostering inclusivity and providing support within religious communities. The subsequent protocol delineates the sequential actions involved in data acquisition while ensuring adherence to ethical principles and obtaining informed consent from participants throughout the research.

Participants must have a well-defined and thoroughly informed consent agreement before data-collecting activities commence. This document comprehensively elucidates the study’s objectives, the methodology employed in conducting interviews, the potential risks and benefits associated with participation, and the guarantee of maintaining anonymity. The participants had sufficient opportunity to examine the permission form thoroughly, seek clarification if needed, and express their voluntary agreement in written form to partake in the study. The process of obtaining consent was continuous, with reaffirmation occurring at the commencement of each interview.

In addition, validation of Interview Questions: To establish the credibility and consistency of the interview questions, a panel of three (3) experts with expertise in qualitative research carefully evaluated the set of interview guide questions selected by the researchers. The set of questions that had been finalized was then continuously employed throughout the study.

Furthermore, pertinent religious organizations and institutions sought a request for Interview Authorization to conduct interviews within their premises if needed. Furthermore, if the participants have existing affiliations with particular religious organizations, appropriate consent or endorsement was obtained from those institutions to facilitate the smooth execution of the interviews. However, the primary setting of the interview was in the participant’s house or a cafe. The primary objective of these requests is to uphold transparency and demonstrate reverence for the religious situations at hand.

Ethical considerations were rigorously observed in this research, following established criteria. The confidentiality of participants was upheld during the study, ensuring that all data collected would be anonymized. All personal identifiers will be removed or modified to ensure the confidentiality of the participants’ identities. Participants were allowed to discontinue their involvement in the study at any given time without facing any adverse repercussions. To guarantee that the research conforms to established ethical norms, it is necessary to acquire ethical approval from an institutional review board. They were also debriefed right after the session to ensure the researchers could provide clarification and additional support to all the study participants if needed.

Interview Protocol: Participants were asked to discuss their experiences candidly throughout the interviews. The interviewer establishes a conducive and impartial atmosphere to encourage open and honest responses. The duration of each interview per participant will approximately take 20-30 minutes to ensure that all the necessary information will be obtained and any clarification of the researchers and participants can be accommodated. Every interview was recorded using audio technology, with the explicit permission of the participants, and then converted into written form for analysis. The interviews adopted a semi-structured format, allowing participants to provide detailed accounts of their experiences, beliefs, and emotions of their LGBTQ+ identification and strong religious ties.

This study endeavors to offer useful insights into the experiences of LGBTQ+ individuals within religious contexts by adhering to a complete research data-gathering approach that upholds ethical standards and respects the rights and privacy of participants.

Data Analysis

The data collected from interviews were transcribed, coded, and analyzed using thematic analysis since this approach aims to find, characterize, examine, and report themes in the data. The strategy was selected due to its versatility in analyzing data gathered through various qualitative methodologies and its ease of learning for novice qualitative researchers [45]. Themes and patterns will be identified to gain insights into the specific challenges faced by LGBTQ+ individuals with strong religious ties. The findings were presented comprehensively, highlighting the common experiences, unique perspectives, and potential sources of resilience identified within the data. It involves the reduction and analysis of qualitative data. This strategy includes segmenting, categorizing, summarizing, and reconstructing the data to effectively capture the significant concepts present within the dataset [44].

Ethical Consideration

Before conducting the research study, the following ethical considerations were strictly observed and implemented to obtain the utmost safety and integrity of the participants and the study.

In the realm of ethical considerations, the researchers ensured a foundation of voluntary participation in their study. Participants were granted the autonomy to decide whether to engage, with the assurance that non-participation would bear no consequences on existing services or professional standings. Moreover, a unique facet of voluntariness was that participants could retroactively request the removal of shared information post-participation, emphasizing the commitment to respecting individual choices.

The procedures outlined for the research encompassed a meticulous approach to data collection, focusing on sensitive topics of religion and sexual orientation. Participants were invited to partake voluntarily, with a transparent overview of their involvement’s anticipated duration and format. The researchers, Libiran, Timothy John, Alano, John Carlo, Cepeda, Rowie, and Ramos, Camille Krisandrea, were introduced, ensuring transparency regarding the individuals involved in the study. With a paramount focus on confidentiality, the researchers pledged to maintain participants’ privacy. The interview process, though recorded, ensured anonymity by using pseudonyms and securely storing tapes. A noteworthy commitment was made to destroy these recordings within 60 days, exemplifying a dedication to safeguarding participants’ information.

Addressing potential risks, the researchers acknowledged the topics’ sensitivity and assured participants they had the right to abstain from answering any questions causing discomfort. This cautious approach demonstrated ethical considerations for the emotional well-being of participants. Furthermore, the benefits section emphasized the societal impact of the research, ranging from informed policies to the empowerment of marginalized individuals. The study’s potential to contribute to various disciplines and promote social justice underscored its global significance.

To mitigate any financial burden on participants, the researchers offered reimbursements for transportation and provided tokens as a gesture of gratitude, reinforcing the ethical principle of fairness. On the other hand, the confidentiality clause reiterated the meticulous measures to protect participants’ privacy, emphasizing restricted access to data and the transformation of personal identifiers into numerical codes.

The transparency continued in sharing results, assuring participants that their identities would remain confidential and findings would be disseminated responsibly through summary reports and institutional meetings before public disclosure.

Lastly, the right to refuse or withdraw was unequivocally stated, reinforcing the voluntary nature of participation. Participants were granted post-interview review rights, ensuring accuracy in the representation of their remarks- a testament to the researchers’ commitment to respecting participants’ autonomy and maintaining ethical standards throughout the research process.

Trustworthiness

In qualitative research, “trustworthiness” refers to the quality, truthfulness, and correctness of results. Readers’ trust in results matters [9]. Researchers should establish protocols and methods for each work to be considered by readers [2]. Thus, [26] credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability criteria will be employed to verify this study’s reliability.

Credibility. The credibility of study findings determines acceptability. The research methods, participants, and setting determine the researcher’s credibility with the findings and their legitimacy in terms of its findings [26. Accordingly, the researchers also asked follow-up or probing questions (prolonged engagement) to detect additional factors affecting their information and ensure that researchers and participants understand each other. In addition, triangulation was then also applied by using related studies, observed data, and recorded data. In data analysis, researchers compared their versions of codes for a more accurate result (member checks). The researchers also orient the participants about the study’s scope, benefits, and risks (peer briefing).

Transferability. It involves usability and applicability in different contexts. Researchers must provide a “thick description” of participants and study procedures so readers can determine if the results apply to their situation [26]. The researchers will offer detailed participant descriptions and research methodology to aid future evaluation of result generalization (thick description of this study). The researchers also utilized purposive sampling to ensure homogeneous participants sharing the same phenomenon studied.

Dependability. The study’s result shows consistency and can be repeated in other contexts [26]. Through an audit trail, the researchers carefully and attentively recorded every process of this study, from validation of questionnaire comments, consent forms of participants, certificate of validation of the questionnaire, and the analytic memoing during and after the interview process. Accordingly, this study will address the approach and detail the methodologies the researchers will utilize so that later investigators can assess the quality of research methods and strategies.

Confirmability. The concept of neutrality refers to the degree to which the outcomes of a study are influenced by the participants rather than by the researcher’s biases, motivations, or interests [26]. Further investigators must be able to replicate the results to prove that they were obtained through independent research methods rather than intentional or unconscious bias [17]. In this research, the researchers are committed to ensuring the reliability of their study. They maintained a detailed record of their methods and documents used, such as the questionnaire and the research paper itself, to prevent bias and guarantee fairness. The researchers also had their research advisor review the study itself. Additionally, they used analytic memoing to record important information throughout the research process, ensuring that the generated codes and themes were rooted in the participants’ information (reflexivity). Lastly, triangulation was applied by supporting the results by three (3) related theories.

This chapter contains the tables that present the findings and interpretations of the data collected via in-depth interviews. The interview data were coded and themed using thematic analysis to identify emerging themes.

Table. II Conflict Experienced By LGBTQ+ Individuals with Strong Religious Ties

| Inequitable and Oppressive Treatment | (1) Narrowly entrenched in fixed beliefs; (2) Harsh and unequivocal disapproval; (3) Unjust differentiation based on individual attributes; (4) Deliberate societal omissions; (5) Mistreatment; (6) Blackmailing; (7) Helplessness; and (8) Humiliation. | |

| Ecclesiastical Dilemmas | (1) Forceful and unfair rules of the church; (2) Faulty teachings of the church; and (3) Loss of belief in one’s religion. |

Table. II highlights the two emerging themes under the conflict experienced by LGBTQ+ individuals with strong religious ties, namely unjust treatment and ecclesiastical dilemmas. Under unjust treatment, eight sub-themes emerged, which are close-minded, condemnation, discrimination, exclusion, mistreatment, blackmailing, helplessness, and humiliation. Furthermore, under ecclesiastical dilemmas, three sub-themes emerged: forceful and unfair church rules, faulty church teachings, and loss of belief in one’s religion.

Inequitable and Oppressive Treatment

Narrowly Entrenched in Fixed Beliefs:

The participants described how the church and its members are resistant to changing their views on LGBTQ+ individuals, firmly believing in a binary understanding of gender. This resistance leads to unsolicited opinions and insults directed at LGBTQ+ individuals.

Participant 1 said, “Sometimes, we cannot force them or ask them to understand their point of view since they have a strong belief that cannot be altered. It is difficult for them to accept other opinions and facts.” Moreover,

Participant 5 said, “There are still individuals who are close-minded to the point that they keep making jokes about my sexuality, and sometimes, I perceive it as rude, and I notice that they intentionally outed my sexuality in public places and situations. Although I am comfortable with my sexuality, still, I am the one who should tell people about it and not them.” Also,

Participant 7 said, “The conflicts I experienced was when people around me were talking about same-sex marriage since they always pointed out that everyone should strictly follow what is written in the bible, which is man and woman are the only ones allowed to marry each other.”

Harsh and Unequivocal Disapproval:

According to the participants, they mainly highlight the negative judgment and rejection faced by LGBTQ+ members. It signifies the alienation and harsh treatment they endure due to their sexual orientation, often rooted in religious beliefs and doctrines. This condemnation often leads to feelings of exclusion, isolation, and emotional distress among LGBTQ+ members.

Participant 2 said, ” Sometimes some people will make a euphemism; they are trying to tell me something very differently. They will not directly tell you, but you will eventually understand their main point that it is not right to be homosexual. That you need to be like this and that (straight). And that being sexually attracted to the same sex is a big sin towards god.” Additionally,

Participant 3 said, ” Within my parents, they always argue that I should choose and love a man instead of a girl like me since it is a sin towards God to love a same-sex individual.” Consequently,

Participant 5 said, “Every time I go to our church, everyone is looking at me and making me feel like I sinned, and I hate that feeling.”

Unjust Differentiation Based on Individual Attributes:

The participants underscore the unjust treatment and prejudice experienced by LGBTQ+ individuals within their religious communities. This theme emphasizes the disparities in opportunities, acceptance, and rights faced by LGBTQ+ members due to their sexual orientation as a result of discrimination perpetuated by religious beliefs and practices as their friends, family members, and church members made them feel that they were different and not accepted.

Participant 3 said, “There are times that even my own family vocally and explicitly make me feel like they are disgusted towards me because of my sexuality.” Moreover,

Participant 1: ” There is also a part in my relationship with my mom, because of course, she is religious with us, but what, mom loves us, me, but it’s really what they believe, and who I am, she doesn’t accept.” In addition,

Participant 5 said,” One time I saw my church friend at school, and I said hi/hello because we looked at each other. Then , I was surprised because he just walked past me. I thought that maybe he didn’t see me, but the next day I saw him at the canteen, and I waved as a hello/hi sign and then I was disappointed again. I thought, “Is this because of my gender?”

Deliberate Societal Omissions:

The participants reveal the deliberate isolation and marginalization experienced by LGBTQ+ individuals within their religious communities. This theme highlights how LGBTQ+ members are often pushed to the fringes, denied participation, and made to feel unwelcome due to their sexual orientation.

Participant 5 said, “ The same goes at church every day. I have seen my friends before at my church, and they seemed uncomfortable with me, given that I’m publicly known as part of the LGBTQ+. It hurts me because just because of gender and religion, it seems like I’m becoming an outcast that I am” furthermore,

Participant 1 said, “ I feel that I am not accepted in my religion ever since they found out about my sexual identity and my relationship with my partner.” Additionally,

Participant 5 said, ” I feel that my church friends are not paying much attention to me anymore, and they have distanced themselves from me, and I felt that.” On top of that,

Participant 5 said, “ Certainly, they made me feel unwelcome, even more so.”

Mistreatment :

The mistreatment of religion and its members towards LGBTQ+ members underscores the unjust and harmful actions, words, and attitudes directed at LGBTQ+ individuals within religious communities. This theme reveals the pain, discrimination, and prejudice that LGBTQ+ members often endure due to their sexual orientation, as their actions towards their LGBTQ+ members are mainly negative and unwelcoming.

Participant 5 said, “ They say they respect LGBTQ+ members, but their actions say otherwise.” Also,

Participant 5 said, “ Yes, because sometimes when I used to greet or say hello to my friends before, they no longer acknowledge me because my gender and identity are already well-known in school and our church.”

Blackmailing :

As stated by participants, they experienced coercive and manipulative practices within religious communities. This highlights how these LGBTQ+ individuals are subjected to threats, pressure, or emotional manipulation as a means to suppress their identity, silence their voices, and force them to change and comply with what their religion considers to be morally right.

Participant 1 said, “ Their actions, they visit our house, I promise. Like when they found out about my partner (an LGBTQ+ couple) when they learned about it, it’s as if when I came out to them, they waited for my partner, saying they would have them imprisoned.” Similarly,

Participant 1: said, “ it’s like, they didn’t tell me that; it was just mentioned to me by my housemates that they’re waiting for that. It’s like, of course, it feels like my privacy is being invaded.”

Helplessness :

The feeling of helplessness experienced by LGBTQ+ individuals due to misguided teachings by the church is a profound theme that centers on the emotional turmoil and identity crisis they endure. Such teachings and beliefs lead to a sense of self-wrongness and contribute to their struggles in accepting their LGBTQ+ identity within the context of their faith. Participant 2 said, “ Maybe the part where, like, my struggles, I had one time, I had an identity crisis because, you know, I was born a Christian, and since I was a child, I was very religious. So, it was instilled in our minds that these things are wrong and sinful. That’s why I reached a point where, you know, because you realize within yourself that it’s not a choice, right? It’s not my choice to be like this. You just really feel it.” Additionally,

Participant 2 said, ”So I reached a point where I struggled, praying and even crying, hoping that I wouldn’t be LGBTQ+, that I wouldn’t be like this, wishing I could change, hoping I could become straight. Those were my struggles that continue until now.”

Humiliation:

As experienced by the participants, humiliation reflects the demeaning and degrading treatment that they often experience within their religious communities. This theme highlights the instances of shame, ridicule, and degradation directed at LGBTQ+ members, which can lead to profound emotional and psychological distress, questions of one’s identity, and loss of self-confidence.

Participant 1 said, “ What happened to me was I lost the desire to worship, but my belief in the Iglesia ni Cristo (INC) didn’t disappear. It’s just that I still hold on to the INC beliefs, but the main thing that diminishes my love for it is when there’s a lack of respect. Something happened before, like once, just earlier this year. I had just returned, went back to INC, and attended worship again because I wanted to try it, but then, I was humiliated in front of other people.” Furthermore,

Participant 5 said, “ Sometimes, I think that maybe this is not me. That there’s something wrong with me? To the point that I even doubted myself and questioned myself.” Accordingly, Participant 5: “It took away much of my confidence, self-respect, and self-love. I remember, one day, I found myself feeling low, extremely sad, and kept asking myself why I became like this and such.”

Ecclesiastical Dilemmas

Forceful and Unfair Rules of Church:

The imposition of “Forceful and Unfair Rules by the Church Towards LGBTQ+ Members” for participants signifies the unjust and coercive regulations and expectations placed upon them within their religious communities. They cannot be themselves when serving God, leaving no option for them as an individual to be themselves, and continuously condemn them for not following the sacred rules of the church.

Participant 2: said, “ There have been instances in our church where I found myself contemplating their teachings, particularly when they talk about LGBTQ+ issues, like in the case of same-sex marriage. We know that same-sex marriage is considered sacred to them. Even civil unions, I get it if they’re against same-sex marriage, but even civil unions, they still seem to be against it because they still instill the idea that it’s wrong for two people of the same sex to be together.” Consequently,

Participant 6 said, “Uhm, what I experienced before the pandemic was that my hair was long because cutting it was not allowed back then because of health restrictions (pandemic). The lectors and commentators are the ones who read the Gospels and Good News. So, this particular person asked me if I wanted to do that. As someone involved in the church, I wanted to, but the conflict arose because of my sexual orientation and my long hair. According to liturgical laws or regulations, you cannot read the Gospel if you have long hair. You need to be presentable; for example, if you’re a man, you should look presentable as a man. For instance, you can’t have long hair; it should be short, well-groomed, and masculine.” To add,

Participant 6 said, “Because up until now, there hasn’t been a transgender person or a girl dresser who has been a lector or commentator in our church. It’s either a girl or a boy, or a gay person wearing male attire or, um, a bisexual person dressed accordingly. It’s either feminine or masculine attire.”

Faulty Teachings of the church:

The participants also pointed out the inaccurate or harmful beliefs and doctrines promoted by the church, which can contribute to misunderstandings, discrimination, and stigmatization of LGBTQ+ individuals. Since the church and its members use what is written in the bible as a weapon to discriminate, exclude, and insult them.

Participant 2 said, “It seems like I entered another phase where I started thinking that not everything taught in the church is correct. It’s like some of them are just persecuting others.” Additionally,

Participant 2 said, ”Especially for me, every time I attend church and listen to the teachings, I find myself affected, making me question if it’s still right. It’s like everything about LGBTQ+ is being criticized using Bible verses as if everything is based on the Bible.” Also,

Participant 2 said, “ It’s like they’re pulling out verses and throwing them at aspects of the LGBTQ+ community. For example, they say that God only created Eve and Adam, and there shouldn’t be anything else. There’s another one, Corinthians, I think, if I’m not mistaken, stating that engaging in same-sex relations is a sin. “

Loss of Belief in One’s Religion:

Due to Faulty Treatment and Teaching by the Church and Its Members, for the participants, it signifies the profound impact of discrimination, mistreatment, and misguided teachings within religious communities, leading many LGBTQ+ individuals to question, and in some cases, abandon their religion but not their faith. Because of the insult given by the church itself, the participants found themselves questioning themselves and the religion itself if they should still stay with it since persecution, discrimination, and disrespect overpower it.

Participant 2 said, ” In the long run, you start questioning all these things, wondering if it’s right, where you stand because they say it’s your choice, but it doesn’t feel like a choice.” Similarly,

Participant 4 said, ” Actually, I find myself drifting further away from my religion because of cases like that. Still, as long as I know who I believe in, I think I’m okay with that and know where my faith lies.” On top of that,

Participant 5 said, “ Yes, from the moment I acknowledged my identity, that I am part of this community (LGBTQ+), I mentioned that I might not be able to return to the church despite my strong faith in God. There are stereotypes and discrimination against us because the Bible is against us, so those who follow the Bible might do the same. That’s why I started avoiding my religion, and it affects me a lot since I used to be an active churchgoer before. “

Table. III Perception Towards the Role of Religion Towards Support in Well-Being

| Domains | Themes | Subthemes |

| “How do Filipino LGBTQ+ individuals with strong religious ties perceive their religion as a source of support and resilience” | (1) Support System; | |

| (2) Open-Minded; | ||

| Positive Effect | (3) Autonomy. | |

| (1) Blamed; | ||

| Negative Effect | (2) Negative Criticisms; | |

| (3) Unwelcome. |

Table III highlights the two emerging themes based on how they perceived their religion as a source of support and resilience: positive and negative effects. Three sub-themes emerged under the theme of positive effect: support system, open-mindedness, and Autonomy. On the other hand, under the theme of negative effect, three sub-themes emerged, namely, blamed, negative criticisms, and unwelcome.

Positive Effect

Support System: