An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Eur J Psychol

- v.17(2); 2021 May

Shame and Self-Esteem: A Meta-Analysis

Yohanes budiarto.

a Faculty of Psychology, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

b Faculty of Psychology, Universitas Tarumanagara, Jakarta, Indonesia

Avin Fadilla Helmi

Scholars agree that shame has many effects related to psychological functioning declines, and one among others is the fluctuation of self-esteem. However, the association between shame and self-esteem requires further studies. Heterogeneity studies due to different measurements, various sample characteristics, and potential missing research findings may result in uncertain conclusions. This study aimed to explore the relationship between shame and self-esteem by meta-analysis to come up with evidence of heterogeneity and publication bias of the study. Eighteen studies from the initial 235 articles involving the term shame and self-esteem were studied using the random-effects model. A total of 578 samples were included in the study. The overall effect size estimate between shame and self-esteem (r = −.64) indicates that shame correlates negatively with self-esteem and is large effect size. The result showed that heterogeneity study was found (I² = 95.093%). The Meta-regression showed that age moderated the relationship between shame and self-esteem (p = .002), while clinical sample characteristics (p = .232) and study quality (p = .184) did not affect the overall effect size.

Self-esteem is a psychological trait that is very well known and very well studied and explained by Branden (1994) as a person's belief in their worthiness to be rejoicing and able to cope with and handle everyday life issues. Self-esteem can be determined by positive or negative self-assessment by comparing one with others ( Reilly, Rochlen, & Awad, 2014 ). According to Branden (1994) , self-esteem is a basic human need that is important for the continuation of positive, productive functions of life, such as interpersonal relationships, workplaces, and education. High self-esteem correlates with various positive effects such as altruism, compassion, the ability to deal with change and resilience ( Branden, 1994 ). On the opposite, low self-esteem correlated with depression ( Steiger, Allemand, Robins, & Fend, 2014 ), addiction, and low levels of resilience and competence to overcome life difficulties ( Branden, 1994 ).

Rosenberg, 1965, describes self-esteem as a self-related concept that refers to self-worth, feasibility, and adequacy (as cited in Gilbert & Procter, 2006 ). Gilbert and Procter (2006) find that low self-esteem increases an individual's vulnerability to negative mood conditions such as shame. Likewise, Wells, Glickauf-Hughes, and Jones (1999) postulate that high levels of shame are correlated with low self-esteem due to flaws and defects arising from experiences of shame that reflect low self-esteem. This correlation is very important because low self-esteem has been associated with negative mental conditions, such as depression ( Johnson & O'Brien, 2013 ). Within a life-span, self-esteem increases during young and middle adulthood, reaching the highest point at about age 60 to 65, and declining in old age ( Orth, Trzesniewski, & Robins, 2010 ).

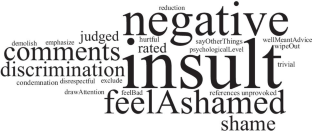

Shame is generally defined as strong negative emotions characterized by perceptions of the global devaluation of oneself. Tangney and Dearing (2002) define shame as strong negative emotions in which the feeling of global self-evisceration is experienced. Shame is often generated by social events in which a personal status or feeling of rejection is sensed. Shame can refer to various aspects of the self, such as behavior or characteristics of the body, and broader identities ( Hejdenberg & Andrews, 2011 ). In particular, the multidimensional conceptualization of shame has been posited ( Andrews, Qian, & Valentine, 2002 ) to distinguish: 1) characteristic experiences of shyness (i.e., regarding personal habits, various styles with others, and personal skills); 2) experience shameful behavior (doing something wrong, saying something stupid, and failing in competition); and 3) bodily shame (i.e., called shame about one's physical appearance). Shame can cause severance of body image, low self-esteem, and feelings of guilt ( Franzoni et al., 2013 ).

Shame is a self-evaluative emotion that involves concern and attention about oneself. When shame is perceived as an emotionally painful emotion, it may have the power for self-break ( Fortes & Ferreira, 2015 ). When individuals experience shame, the devaluation of self is perceived, and it may lower self-esteem. The frequent feeling of shame can eventually form into a trait of shame. Trait shame, in turn, involves negative feelings that are very painful and often crippling, which involve feelings of inferiority, despair, helplessness, and the eagerness to hide personal flaws ( Andrews et al., 2002 ). Thus, it can be assumed that shame experience is closely related to fluctuations in self-esteem ( Elison, Garofalo, & Velotti, 2014 ). Furthermore, low self-esteem can increase an individual's vulnerability to experience negative emotional states, including shame. Thus, although the direction of their association is unclear, several studies have reported a substantial relationship between low self-esteem and negative emotions, such as guilt and shame ( Garofalo, Holden, Zeigler-Hill, & Vellotti, 2016 ).

Demographic Dynamics in the Relationship Between Shame and Self-Esteem

As the self-concept develops, children begin to sense of self-appears at age two until they get a more stable self-concept ( Lewis, 2000 ). During this development, at about age 3, children start to develop the capacity of self-evaluation related to differences between them and other children and understand morality and social norm ( Muris & Meesters, 2014 ). Children and adolescents seem to have the same differences as adults in determinant factors of guilt and shame. Children, when asked about their understanding of situational determinants of guilt and shame, they state that feelings of guilt are related to violations of moral norms such as property damage or personal reproach ( Ferguson, Stegge, & Damhuis, 1991 ). The emotion decreases with age ( Williams & Bybee, 1994 ).

Children are believed to start experience shame only when they have reached the cognitive capacity to understand themselves as objects for reflection and have social maturity to understand and apply social scripts and rules of behavior ( Emde, Johnson, & Easterbrooks, 1987 ; Lewis, Sullivan, Stanger, & Weiss, 1989 ). A cohort-sequential longitudinal study by Orth, Robins, and Soto (2010) found that shame declined from adolescence into middle adulthood, arriving at the lowest point around age 50 years, and then grew old. This variation brings impact to the self-esteem dynamics as shame requires self-evaluation, which in turn, the evaluation impacts self-esteem.

The dynamic relationship between shame and self-esteem may also be moderated by population trait: clinical and nonclinical populations. Dyer et al. (2017) conducted research comparing clinical samples (Dissociative identity disorder [DID], Complex Trauma and General Mental Health) with a healthy volunteer control group and found that the clinical groups exhibited significantly greater shame than those of nonclinical samples. These clinical traits populations are used as a moderating factor in the relationship between shame and self-esteem.

Another assumed moderating effect might derive from the various quality of the studies in meta-analysis. Quality of studies provides researchers a valid estimate of the truth of the studies ( Moher et al., 1993 ). A standardized tool to assess the quality study classifies the study based on the characteristics of published articles. Such features are intended to estimate the precision of the findings and data in the study, where the precision is a function of systematic error and random error. It functions to classify possible causes of bias in meta-analysis outcomes as well as to describe the strengths and shortcomings of analysis in the topic of the study.

From the description above, the research questions are as follows: 1) "Does shame correlate with self-esteem?," 2) “Do age differences moderate the relationship between shame and self-esteem?" 3) “Do clinical characteristics moderate the relationship between shame and self-esteem?" and 4) "Do quality studies affect the effect size of the study?"

Statistical Analysis

Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (Version 3.0) software (CMA; Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins, & Rothstein, 2013 ) is used to perform statistical analyses of publication bias, study heterogeneity, and meta-regression. The random-effects model is used to estimate the variance distribution of observed effects sizes given in participants, regions, and methods throughout the study studied ( Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins, & Rothstein, 2010 ). When researchers decide to include a group of studies in a meta-analysis, researchers assume that research has sufficient common sense to synthesize information, but generally, there is no reason that they are “identical” in the sense that the actual effect size is the same in all studies ( Konstantopoulos, 2006 ).

The results of each study included in this meta-analysis were quantified in the same metric, by calculating the effect size index, and then estimating effects were statistically analyzed to 1) obtain estimates of the average magnitude of the effect, 2) assess heterogeneity in-between effect estimates, and 3) looking for characteristics of research that can explain heterogeneity ( Cooper, 2010 ). To measure heterogeneity in all studies, indicators of heterogeneity, such as Q and I -squared statistics, were calculated in this study. The Funnel plot and fail-safe N statistics were adopted to estimate publication bias ( Egger et al., 1997 ). Meta-regression was used to detect the moderating effects of age, population dichotomy: clinical and nonclinical, and the quality of every study as possible sources of heterogeneity throughout this study.

Study Search

After the research questions were formulated, the next step is to define the eligibility criteria of the study, namely the characteristics that had to be met to be included in the meta-analysis. This study follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines ( Liberati et al., 2009 ).

Inclusion Criteria and Exclusion Criteria

We applied the following standards to screen the data found in databases:

- English language papers: We limit studies in English, so that understanding of the content of studies is adequate.

- Samples involving clinical or nonclinical characteristics, as well as the means of age, were retained so that it could be used as a moderator variable when heterogeneity of studies was found.

- Measurement of shame: Shame was measured with a standard scale. Studies of shame psychometric were also coded. We ensured that the variable shame did not overlap with the concepts of shyness, embarrassment, vicarious shame, body shame, humiliation, and guilt. When found, those terms were excluded from the study.

- Measurement of self-esteem: Self-esteem was measured using a standardized questionnaire. Any concepts related to self-esteem, such as self-concept, self-efficacy, and self-worth, were excluded from the study.

- Study design: Selected studies are limited to quantitative studies; however, the design of the studies could vary as prospective studies, cross-sectional experiments and correlations, and psychometrics. We excluded publications that reported only qualitative data, reviews, or theoretical works.

- Statistical information: only studies showing correlation coefficients between shame and self-esteem, whether found in pilot studies or primary studies, were selected in the analysis. Other information, such as betta weights in the regression study, was converted to the correlation coefficient.

Literature searches were conducted on the PsycINFO database, Sage Journals, Scopus, and Proquest. The keywords used in the research were: "shame," "self-esteem," "self-worth," "shame scale." The first step was to screen all 578 potential articles, as displayed in PsycInfo. Three hundred forty-three articles were excluded because quantitative data were not stated. We continued to explore the remaining 235 full articles that explicitly mentioned quantitative information in abstracts and found 217 studies that mention correlation coefficients in the results. We continued to screen for the full article and strictly selected the construct of shame and self-esteem. We excluded 193 studies that did not measure shame referred to in our study. From the selection results, we found 24 study articles that measured both shame and self-esteem and also found the effect size needed. After digging up information that could be the causes of heterogeneity in studies such as population characteristics and means of age, six studies were found that lacked both demographic information. Finally, we had 18 studies from 2002 to 2018, analyzed in the meta-analysis. (see Figure 1 for the flowchart of study selection).

Shame and esteem-related keywords such as body-shame, body esteem, collective esteem, and social esteem were excluded in the analysis. For descriptive purposes, the researcher noted the years of study, researchers, the source of the article, sample size, characteristics of the sample divided into clinical and nonclinical, and the mean age of the sample. The mean age of participants in the form of continuous data and the distribution of sample characteristics as clinical and nonclinical were used as moderators in the meta-regression analysis.

Quality Assessments

Quality assessment of the studies in this study was adapted from the Quality Assessment and Validity Tool for Correlational Studies ( Cicolini, Simonetti, & Comparcini, 2014 ). We employed four criteria, which are described in 13 questions to assess the design, sampling techniques, measurements, and statistical analysis of each study we study. The availability of information in the study following the question was given a score of 1 (Yes/reported), and a score of 0 (No/not measured) was given when the information needed in the study was not found. From these 13 questions, the range was 0–14 because there was one question that had a score of 2 (Yes), namely questions related to the reliability of the instruments in the study. Studies were then categorized into three groups based on total scores: low (0–4), medium (5–9), and high (10–14). Table 1 below shows the template of the quality assessment of each study.

Note . 0–4 = LO; 5–9 = MED; 10–14 = HI.

A summary of quality assessments of 18 studies that had been screened showed that 14 studies have high quality and four studies of medium quality. Four studies of medium quality were two studies of Gao, Qin, Qian, and Liu (2013) , Wood, Byrne, Burke, Enache, and Morrison (2017) , and Yelsma, Brown, and Ellison (2002) . The quality of the study medium is due to not fulfilling random sampling criteria, participant anonymity, non-prospective study designs, and sampling from various sites. Fourteen studies reviewed were of high quality ( Feiring, Taska, & Chen, 2002 ; Goss, 2013 ; Greene & Britton, 2013 ; Legate, Weinstein, Ryan, DeHaan, & Ryan, 2019 ; Passanisi, Gervasi, Madonia, Guzzo, & Greco, 2015 ; Pilarska, 2018 ; Reilly et al., 2014 ; Simonds et al., 2016 ; Velotti, Garofalo, Bottazzi, & Caretti, 2017 ; Ward, 2014 ; Woodward, McIlwain, & Mond, 2019 ; Zhou, Wang, & Yi, 2018 ). Of all studies, only a study by Feiring et al. (2002) conducted a retrospective study even though the selection of samples was not random. The majority of studies in this meta-analysis did not conduct random sampling and outlier handling in the analysis. A moderation analysis of the study quality classification was carried out to see its effect on the overall effect size. The moderation analysis was carried out together with age, characteristics of the samples, and quality study by meta-regression. Table 2 summarizes the quality assessment of 18 studies included.

In this study, the effects size index used is the correlation coefficient. When the correlation coefficient is used as a measurable effect, both Hedges and Olkin and Rosenthal and Rubin recommend the transformation of this effect size to a standard normal metric (using the r -to-Fisher Z transformation). The following Table 3 shows the distribution of research data studied, supplemented by information on the correlation coefficients that have been transformed into Fisher's Z along with their standard errors, variances, Z values, and p -values.

a Female participants. b Male participants.

Heterogeneity Study

Heterogeneity testing of all studies is summarized in Table 4 . I 2 statistics for heterogeneity was 95.09 (95.09%), p < .001, which resulted in the acceptance of alternative hypotheses and showed significant heterogeneity in the studies taken. I 2 shows the amount of variability that cannot be explained by chance. In other words, I 2 index explains the percentage of variability estimate (95.09%) in results across studies that is due to real differences and not due to chance. Also, Q values higher than df indicates heterogeneity.

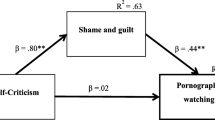

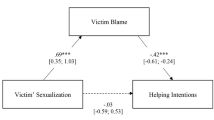

Figure 2 below summarizes the results of the meta-analysis with 95% Confidence Interval (CI). The analysis carried out in this study was based on the random-effects model due to the non-homogeneous characteristics of the population. In Feiring's study, the horizontal line/CI almost touched the value of 0 so that the p -value (.047) was close to .05. The forest plot shows that study 2 by Gao et al. (2013) and Simonds et al. (2016) have wide plot lines. The plotline indicates a wider CI, which means that the study has low precision. The overall summary information at the 95% confidence interval shows that in the correlation study between shame and self-esteem, the random effect size is − .643 (moderate effect), with Z -value = − 8.981 and p < .001. Based on the effect size value with p < .001, the alternative hypothesis cannot be rejected so that there is a negative correlational relationship between shame and self-esteem.

Funnel Plots

One other mechanism for displaying the relationship between study size and effect size is Funnel Plots. In this study, the use of standard errors (rather than sample size or variance) on the Y-axis has the advantage of spreading points at the bottom of the scale, where smaller studies are plotted. This can make it easier to identify patterns of asymmetry ( Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins, & Rothstein, 2009 ). Funnel Plots is a spread of effect size on a measure of study accuracy. This description provides information support in the meta-analysis, mainly related to the heterogeneity of studies ( Stuck et al., 1998 ).

Based on Funnel Plots in Figure 3 , it appears that the distribution of effects on the standard error forms a "funnel," giving the impression that there are no biases in the analyzed studies, no asymmetrical plot.

The majority of studies with large effects appear towards the top of the graph and tend to cluster near the mean effect size. More small-effect research appears to the bottom of the graph, and because there are more sampling variations in the estimation of effect sizes in studies with small effects, this study will be spread over a range of values.

With no publication bias in these studies, the lower part of the plot does not show a higher concentration of studies on one side of the mean than the other. This graph reflects the fact that studies that have smaller effects (which appear downward) are more likely to be published if they have a greater effect than the mean effect, which makes them more likely to meet the criteria for significant statistics ( Hunter et al., 2014 ).

Fail-Safe N

The fail-safe N related to publication bias in this study uses Orwin, 1983, approach (as cited in Borenstein et al., 2009 ) as summarized in Table 5 . The Orwin approach allows researchers to determine how many studies are missing, which will bring the overall effect to a specified level other than zero. Therefore, researchers can choose a value that will represent the smallest influence that is considered important and substantive, and ask how many missing studies are needed to bring the summary effect below this point.

The mean Fisher's Z in the new study (which is missing) can be a value other than zero, which in this study, was set at 0.00001. Also, the value of the criteria used is the effect size Z instead of the p -value. This means that the Orwin fail-safe N is the number of missing studies, which when added to the analysis, will bring the combined Z value above the specified threshold (currently the upper limit is set at, 0.600). The fail-safe N Orwin numbers obtained is 1. This result means that we need to find 1 study with the mean Fisher's Z value of 0.648 to bring the combined Z value above the value 0.650.

Bagg and Mazumdar's Rank Correlation

The rank correlation test uses the Begg and Mazumdar tests ( Begg & Mazumdar, 1994 ), which involve correlations between effect sizes rank and variances rank, respectively. The result of the analysis shows a value of p = .879, indicating the acceptance of the null hypothesis and showing no publication bias. In this case, Kendall's value b is − 0.026, with p -value 1-tailed (recommended) of .439 or p two-tailed value of .444 based on normal estimated continuity correction, as shown in Table 6 . The estimated value of Kendall's tau rank correlation coefficient shows that the observed outcomes and the corresponding sampling variances are not highly correlated. This finding means that a very low correlation would indicate that the funnel plot is symmetric, which may not show a result of publication bias.

Egger's Regression Intercept

Egger shows that the bias assessment is based on precision (the opposite of the standard error) to predict standardized effects (effect size divided by standard error). In this equation, the measure of the effect is captured by the slope of the regression line ( B 1 ), while it can be captured by the intercept ( B 0 ). In this study, the intercept ( B 0 ) was −0.946, 95% CI[−8.581, 6.688], with t = 0.263, df = 16. The p 1-tailed value (recommended) was .398, and the p 2-tailed value is .796 indicating no evidence of publication bias.

Duval and Tweedie's Trim and Fill

Based on Funnel Plots analysis, the observed and imputed plots were detected that more studies were on the right side than those on the left side. Therefore, the assumption that arises is that missing studies have occurred on the left side of axis X. In Figure 3 , observed studies are described as open (colorless) circles, while six imputed studies are represented by black circles.

If the meta-analysis has captured all relevant studies, it is expected that the funnel plots will be symmetrical. That is, we would expect research to be spread evenly on both sides of the overall effect.

Duval and Tweedie went more advanced by a method that allowed us to link these missing studies. That is, the researcher determines where the missing study tends to "disappear," then adds it to the analysis, and then recalculates the combined effect. This method is known as Trim and Fill ( Duval & Tweedie, 2000 ).

If we refer to Figure 3 , an asymmetrical study of the right side is trimmed to find an unbiased effect (in an iterative procedure) and then fill the plot by re-entering the study trimmed on the left side of the mean effect. This program looks for missing studies based on the random-effects model and looking for studies that are lost only to the left side of the mean effect. This method shows that there are seven missing studies. Based on the random effect model, the estimated points at the 95% confidence interval for the combined study are − 0.643 ( − 0.784, − 0.502). Using Trim and Fill, the estimated imputed points are − 0.812 ( − 0.962, − 0.663). See Table 7 for Duval and Tweedie's Trim and Fill output.

Age, Characteristics of Samples, and Quality of Studies as Moderators

After heterogeneity of the studies is detected, the next step is to identify the variables and characteristics which cause heterogeneity. Meta-regression analysis is used to estimate the parameter effects with minimum variance. In this study, the age, population characteristics, and study quality are considered as covariates between shame and self-esteem.

The age, clinical/nonclinical characteristics, and high and low study qualities moderating effect tests are based on the random-effects model with the restricted maximum likelihood model (REML) estimation method. Based on the analysis using a meta-regression test, it can be explained that the regression coefficient for age is equal to − 0.03, which means that every one degree of age equals a decrease in the effect size of 0.03. The p = .02 shows the variable age functions as a moderator in the relationship between shame and self-esteem. Thus, it can be concluded that age moderates the relationship between shame and self-esteem because age is significantly related to effect size. Differences in sample characteristics based on clinical and nonclinical groups do not have a moderating effect on the relationship between shame and self-esteem ( p = .232). The quality of studies that are categorized into high and moderate-quality does not moderate the relationship between shame and self-esteem ( p = .184). Study quality, age, and sample characteristics simultaneously affect the effect size ( p = .03). The summary of the meta-regression is shown in Table 8 .

Note . Simultaneous test: Q = 9.32, df = 3, p = .03.

Apart from the above calculations, a scatter plot can also explain the pattern of the relationship between age as a moderator and the observed effect size. The scatter diagram below illustrates that there is a clear relationship between age as a moderator and the observed effect size. It can be concluded that as age increases, the effect size moves away from 0. This means that the relationship between shame and self-esteem (when other covariates are controlled) gets stronger as we age. Figure 4 shows the regression plot of age as a moderator.

The meta-analysis results displayed a negative correlation between shame and self-esteem with effect size is different from zero ( r = − .643, p < .001). The random-effects model analysis shows the mean of the distribution of the true effects is 0.643. According to Cohen's classification, it is classified as a large effect size. This finding supports the research hypothesis that there is a relationship between shame and self-esteem.

Shame, as self-conscious emotion, deals with negative, global, and stable evaluations of the self ( Tangney & Dearing, 2002 ), and it brings impact to the fluctuation of self-esteem. When a person perceives himself as "a bad person," their self-esteem decreases. Usually, feelings of shame happen due to a condition where the personal self is devalued, such as a bad performance socially assessed. Poor performance leads to greater reactions of psychological states indicating a danger to the social self, namely a decline in social self-esteem and an increase in shame ( Gruenewald, Kemeny, Aziz, & Fahey, 2004 ).

Many shameful experiences can eventually crystallize into a trait-like proneness of shame. Trait shame, in turn, includes an especially painful and often disabling, adverse sensation involving a sense of inferiority, hopelessness, and helplessness, as well as a willingness to conceal private failure ( Andrews et al., 2002 ). Also, shame experiences have been suggested to be closely linked to fluctuations in self-esteem, and many shame experiences might be conceptually linked to chronically low self-esteem rates ( Elison et al., 2014 ).

This study shows that based on publication bias testing with information from funnel plots , fail-safe N , Bagg and Mazumdar rank correlations , Egger's Regression Intercept, and Duval and Tweedie's Trim and Fill no publication bias was found.

To explain what factors causing heterogeneity of the study, the thing that researchers can do is simply enter the mean age of the samples to be analyzed as moderators in the relationship between shame and self-esteem. Analysis with meta-regression showed that the age of various participants moderated the effect size of the relationship of shame and self-esteem. This result shows that the selection of random effect models as the basis of the meta-analysis in this study is appropriate. However, the study qualities and clinical characteristics of the sample did not moderate the effect size.

In a prospective study, De Rubeis and Hollenstein (2009) found that, during early adolescence, shame slightly decreased over a period of 1 year. Similarly, self-esteem follows a quadratic life-span trajectory, increasing during young and middle adulthood, peaking at about 60 to 65 years of age, and declining in old age ( Orth, Trzesniewski, et al., 2010 ). This age dynamics influence the quality of shame and self-esteem relationship.

In the context of the study sample with clinical and nonclinical characteristics, no moderating effect was found. This finding indicates that the dynamics of shame and self-esteem in both characteristics of the research sample are similar. The clinical samples in this study were various, involving those with an eating disorder ( Goss, 2013 ), schizoaffective disorder ( Wood et al., 2017 ), sexual abuse ( Feiring et al., 2002 ), and lesbian, gay, or bisexual (LGB; Legate et al., 2019 ). These different clinical characteristics may interfere with the moderation effect when comparing to nonclinical samples.

In the process of selecting a study, the initial screening has been done so that the variables of shame that are analyzed only involve shame based on self-evaluation in an embarrassing event. Thus, the various measures of shame that are not included in this study include body-shame and trait shame. However, this study still finds heterogeneity in the studies studied. When sensitivity analysis is carried out by looking at relative weight images, there are no different relative weights from the studies analyzed, so that study ejection is not carried out from the analysis. From this, it can be concluded that the occurrence of heterogeneity is not caused by sampling error.

Acknowledgments

We thank Megawati Oktorina for being helpful in screening and selecting studies and their details.

Biographies

Yohanes Budiarto is a third-year psychology Ph.D. student at the Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia. He is currently a lecturer at Faculty of Psychology, Universitas Tarumanagara, Jakarta, Indonesia. He is specialized in Social Psychology, Experimental Psychology as well as in the Indigenous and Cultural Psychology areas. His research areas are within the social-emotion of shame/embarrassment, psychometrics, psychology of religions as well as family studies.

Dr. Avin Fadilla Helmi is a senior lecturer and researcher at Faculty of Psychology, Universitas Gadjah Mada (UGM), Yogyakarta, Indonesia. She is interested in researching cyberpsychology, human relations, leadership, entrepreneurship, innovation, and interpersonal issues.

The authors have no funding to report.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

- Andrews, B., Qian, M., & Valentine, J. D. (2002). Predicting depressive symptoms with a new measure of shame: The experience of shame scale . British Journal of Clinical Psychology , 41 , 29–42. 10.1348/014466502163778 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Begg, C. B., & Mazumdar, M. (1994). Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias . Biometrics , 50 ( 4 ), 1088–1101. 10.2307/2533446 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Borenstein, M., Hedges, L., Higgins, J., & Rothstein, H. (2013). Comprehensive meta-analysis Version 3 . Englewood, NJ, USA: Biostat. [ Google Scholar ]

- Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V, Higgins, J. P. T., & Rothstein, H. R. (2009). Publication bias . Introduction to Meta-Analysis , 53 ( 4 ), 495. 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92099-F [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. T., & Rothstein, H. R. (2010). A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis . Research Synthesis Methods , 1 ( 2 ), 97–111. 10.1002/jrsm.12 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Branden, N. (1994). The six pillars of self-esteem . New York, NY, USA: Bantam. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cicolini, G., Comparcini, D., & Simonetti, V. (2014). Workplace empowerment and nurses' job satisfaction: A systematic literature review . Journal of Nursing Management , 22 ( 7 ), 855–871. 10.1111/jonm.12028 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cooper, H. (2010). Applied social research methods series: Vol. 2. Research synthesis and meta-analysis: A step-by-step approach (4th ed.). Los Angeles, CA, USA: Sage Publications. [ Google Scholar ]

- De Rubeis, S., & Hollenstein, T. (2009). Individual differences in shame and depressive symptoms during early adolescence . Personality and Individual Differences , 46 ( 4 ), 477–482. 10.1016/j.paid.2008.11.019 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Duval, S., & Tweedie, R. (2000). A nonparametric "trim and fill" method of accounting for publication bias in meta-analysis . Journal of the American Statistical Association , 95 ( 449 ), 89–98. 10.1080/01621459.2000.10473905 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dyer, K. F. W., Dorahy, M. J., Corry, M., Black, R., Matheson, L., Coles, H., … Middleton, W. (2017). Comparing shame in clinical and nonclinical populations: Preliminary findings . Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy , 9 ( 2 ), 173–180. 10.1037/tra0000158 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Egger, M., Zellweger-Zahner, T., Schneider, M., Junker, C., Lengeler, C. & Antes, G. (1997). Language bias in randomized controlled trials published in English and German . Lancet , 350 ( 9074 ), 326–329. 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)02419-7 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Elison, J., Garofalo, C., & Velotti, P. (2014). Shame and aggression: Theoretical considerations . Aggression and Violent Behavior , 19 ( 4 ), 447–453. 10.1016/j.avb.2014.05.002 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Emde, R. N., Johnson, W. F., & Easterbrooks, M. A. (1987). The do's and don'ts of early moral development: Psychoanalytic tradition and current research. In J. Kagan & S. Lamb (Eds.), The emergence of morality in young children (pp. 245–276). Chicago, IL, USA: University of Chicago Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Feiring, C., Taska, L., & Chen, K. (2002). Trying to understand why horrible things happen: Attribution, shame, and symptom development following sexual abuse . Child Maltreatment , 7 ( 1 ), 25–39. 10.1177/1077559502007001003 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ferguson, T. J., Stegge, H., & Damhuis, I. (1991). Children's understanding of guilt and shame . Child Development , 62 ( 4 ), 827–839. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01572.x [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fortes, A. C. C., & Ferreira, V. R. T. (2015). The influence of shame in social behavior . Revista de Psicologia Da IMED , 6 ( 1 ), 25–27. 10.18256/2175-5027/psico-imed.v6n1p25-27 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Franzoni, E., Gualandi, S., Caretti, V., Schimmenti, A., Di Pietro, E., Pellegrini, G., … Pellicciari, A. (2013). The relationship between alexithymia, shame, trauma, and body image disorders: Investigation over a large clinical sample . Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment , 9 ( 1 ), 185–193. 10.2147/ndt.s34822 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gao, J., Qin, M., Qian, M., & Liu, X. (2013). Validation of the TOSCA-3 among Chinese young adults . Social Behavior and Personality , 41 ( 7 ), 1209–1218. 10.2224/sbp.2013.41.7.1209 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Garofalo, C., Holden, C. J., Zeigler-Hill, V., & Velotti, P. (2016). Understanding the connection between self-esteem and aggression: The mediating role of emotion dysregulation . Aggressive Behavior , 42 ( 1 ), 3–15. 10.1002/ab.21601 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gilbert, P., & Procter, S. (2006). Compassionate mind training for people with high shame and self‐criticism: Overview and pilot study of a group therapy approach . Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy , 13 ( 6 ), 353–379. 10.1002/cpp.507 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Goss, K. (2013). The relationship between shame, social rank, self-directed hostility, self-esteem and eating disorders beliefs, behaviours, and diagnosis (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global. (Publication No. U230568) [ Google Scholar ]

- Greene, D. C., & Britton, P. J. (2013). The influence of forgiveness on lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning individuals' shame and self-esteem . Journal of Counseling and Development , 91 ( 2 ), 195–205. 10.1002/j.1556-6676.2013.00086.x [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gruenewald, T. L., Kemeny, M. E., Aziz, N., & Fahey, J. L. (2004). Acute threat to the social self: Shame, social self-esteem, and cortisol activity . Psychosomatic Medicine , 66 ( 6 ), 915–924. 10.1097/01.psy.0000143639.61693.ef [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hejdenberg, J., & Andrews, B. (2011). The relationship between shame and different types of anger: A theory-based investigation . Personality and Individual Differences , 50 ( 8 ), 1278–1282. 10.1016/j.paid.2011.02.024 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hunter, J. P., Saratzis, A., Sutton, A. J., Boucher, R. H., Sayers, R. D., & Bown, M. J. (2014). In meta-analyses of proportion studies, funnel plots were found to be an inaccurate method of assessing publication bias . Journal of Clinical Epidemiology , 67 ( 8 ), 897–903. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.003 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Johnson, E. A., & O'Brien, K. A. (2013). Self-compassion soothes the savage EGO-threat system: Effects on negative affect, shame, rumination, and depressive symptoms . Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology , 32 ( 9 ), 939–963. 10.1521/jscp.2013.32.9.939 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Konstantopoulos, S. (2006). Fixed and mixed effects models in meta-analysis (IZA Discussion Paper No. 2198). Retrieved from https://ssrn.com/abstract=919993

- Legate, N., Weinstein, N., Ryan, W. S., DeHaan, C. R., & Ryan, R. M. (2019). Parental autonomy support predicts lower internalized homophobia and better psychological health indirectly through lower shame in lesbian, gay and bisexual adults . Stigma and Health , 4 ( 4 ), 367–376. 10.1037/sah0000150 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lewis, M. (2000). Self-conscious emotions: Embarrassment, pride, shame, and guilt. In M. Lewis & J. M. Haviland-Jones (Eds.), Handbook of emotions . (2nd ed., pp. 623–636). New York, NY, USA: Guilford Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lewis, M., Sullivan, M. W., Stanger, C., & Weiss, M. (1989). Self development and self-conscious emotions . Child Development , 60 ( 1 ), 146–156. 10.2307/1131080 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P. A., … Moher, D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration . PLOS Medicine , 6 ( 7 ), e1000100. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Moher, D., Cook, D., Jadad, A., Tugwell, P., Moher, M., Jones, A., … Klassen, T. P. (1993). Assessing the quality of reports of randomised trials: Implications for the conduct of meta-analyses . Health Technology Assessment , 3 ( 12 ), 1–98. 10.3310/hta3120 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Muris, P., & Meesters, C. (2014). Small or big in the eyes of the other: On the developmental psychopathology of self-conscious emotions as shame, guilt, and pride . Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review , 17 ( 1 ), 19–40. 10.1007/s10567-013-0137-z [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Orth, U., Robins, R. W., & Soto, C. J. (2010). Tracking the trajectory of shame, guilt, and pride across the life span . Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 99 ( 6 ), 1061–1071. 10.1037/a0021342 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Orth, U., Trzesniewski, K. H., & Robins, R. W. (2010). Self-esteem development from young adulthood to old age: A cohort-sequential longitudinal study . Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 98 ( 4 ), 645–658. 10.1037/a0018769 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Passanisi, A., Gervasi, A. M., Madonia, C., Guzzo, G., & Greco, D. (2015). Attachment, self-esteem and shame in emerging adulthood . Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences , 191 , 342–346. 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.04.552 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pilarska, A. (2018). Big-five personality and aspects of the self-concept: Variable- and person-centered approaches . Personality and Individual Differences , 127 , 107–113. 10.1016/j.paid.2018.01.049 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Reilly, E. D., Rochlen, A. B., & Awad, G. H. (2014). Men's self-compassion and self-esteem: The moderating roles of shame and masculine norm adherence . Psychology of Men & Masculinity , 15 ( 1 ), 22–28. 10.1037/a0031028 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Simonds, L. M., John, M., Fife-Schaw, C., Willis, S., Taylor, H., Hand, H., … Winton, H. (2016). Development and validation of the Adolescent Shame-Proneness Scale . Psychological Assessment , 28 ( 5 ), 549–562. 10.1037/pas0000206 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Steiger, A. E., Allemand, M., Robins, R. W., & Fend, H. A. (2014). Low and decreasing self-esteem during adolescence predict adult depression two decades later . Journal of Personality And Social Psychology , 106 ( 2 ), 325–338. 10.1037/a0035133 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stuck, A. E., Rubenstein, L. Z., Wieland, D., Vandenbroucke, J. P., Irwig, L., Macaskill, P., … Gilbody, S. (1998). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical . BMJ , 316 ( 7129 ), 469–469. 10.1136/bmj.316.7129.469 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tangney, J. P., & Dearing, R. L. (2002). Shame and guilt . New York, NY, USA: Guilford Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Velotti, P., Garofalo, C., Bottazzi, F., & Caretti, V. (2017). Faces of shame: Implications for self-esteem, emotion regulation, aggression, and well-being . Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied , 151 ( 2 ), 171–184. 10.1080/00223980.2016.1248809 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ward, L. (2014). Shame and guilt : Their relationship with self-esteem and social connectedness in Irish adults (Unpublished thesis). DBS School of Arts, Dublin, Ireland. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wells, M., Glickauf-Hughes, C., & Jones, R. (1999). Codependency: A grass roots construct's relationship to shame proneness, low self-esteem, and childhood parentification . American Journal of Family Therapy , 27 ( 1 ), 63–71. 10.1080/019261899262104 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Williams, C., & Bybee, J. (1994). What do children feel guilty about? Developmental and gender differences . Developmental Psychology , 30 ( 5 ), 617–623. 10.1037/0012-1649.30.5.617 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wood, L., Byrne, R., Burke, E., Enache, G., & Morrison, A. P. (2017). The impact of stigma on emotional distress and recovery from psychosis: The mediatory role of internalised shame and self-esteem . Psychiatry Research , 255 , 94–100. 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.05.016 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Woodward, K., McIlwain, D., & Mond, J. (2019). Feelings about the self and body in eating disturbances: The role of internalized shame, self-esteem, externalized self-perceptions, and body shame . Self and Identity , 18 ( 2 , 159–182. 10.1080/15298868.2017.1403373 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yelsma, P., Brown, N., & Ellison, J., (2002). Shame-focused coping styles and their associations with self-esteem . Psychological Reports , 90 ( 3_suppl ), 1179–1189. 10.2466/pr0.2002.90.3c.1179 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhou, T., Wang, Y., & Yi, C. (2018). Affiliate stigma and depression in caregivers of children with Autism Spectrum Disorders in China: Effects of self-esteem, shame and family functioning . Psychiatry Research , 264 , 260–265. 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.03.071 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

The Impact of Body Shaming and How to Overcome It

Ariane Resnick, CNC is a mental health writer, certified nutritionist, and wellness author who advocates for accessibility and inclusivity.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/pinkhair-809ed47ad1e844c5b9d25667f1095e62.jpg)

Ivy Kwong, LMFT, is a psychotherapist specializing in relationships, love and intimacy, trauma and codependency, and AAPI mental health.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Ivy_Kwong_headshot_1000x1000-8cf49972711046e88b9036a56ca494b5.jpg)

Wavebreakmedia / Getty Images

Body Shaming in Our Culture

Who are the targets of body shaming, why do we need to stop body shaming, how to be more inclusive.

Body shaming is the act of saying something negative about a person's body. It can be about your own body or someone else's. The commentary can be about a person's size, age, hair, clothes, food, hair, or level of perceived attractiveness.

Body shaming can lead to mental health issues including eating disorders , depression, anxiety, low self-esteem , and body dysmorphia, as well as the general feeling of hating one's body .

In our current society, many people think that thin bodies are inherently better and healthier than larger bodies. Historically, however, that hasn't always been the case. If you think of paintings and portraits from before the 1800s era, you can see that plumpness was revered.

Being fat was a sign that a person was wealthy and had access to food, while thinness represented poverty. In her book "Fat Shame: Stigma and the Fat Body in American Culture," author Amy Erdman Farrell traces the shift from revering heavy bodies to the preference of smaller shapes to mid-nineteenth century England when the first diets books were published.

She noted that the focus on diets, and bodies at large, was centered around women. Author Sabrina Strings says that fatphobia resulted from colonialism and race in her book "Fearing the Black Body: The Racial Origins of Fat Phobia."

According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, the first known use of the term "body shaming" was by journalist Philip Ellis.

Body shaming is most often about body size, but negative comments about any facet of a person's body count as body shaming.

Below are the various reasons why people might be body shamed.

One of the most common reasons people are body shamed is because of their weight. Someone might be body shamed for being "too big" or "too thin."

Saying anything negative about a person being "fat" is body shaming. This is also known as "fat-shaming." Fat-shaming comments are ones like "They'd be pretty if they lost weight," or "I bet they had to buy an extra plane ticket to fit." Men are often body-shamed when people refer to them as having a "dad bod."

People in thinner bodies can also be shamed for their weight. Often called skinny-shaming, it may sound like, "They look like they never eat" or "They look like they have an eating disorder."

Hair grows on the arms, legs, private areas, and underarms of all people, except for those with certain health conditions. However, many people have the idea that women should remove all of their body hair, or they won't be "ladylike."

Examples of body hair shaming are calling a woman with underarm hair "beastly," or telling a woman she needs to shave.

Attractiveness

Known as "pretty-shaming," the bullying or discrimination of people for being attractive, is something that happens regularly. And even more than that, people are bullied for being considered unattractive, which is also known as "lookism." Lookism describes prejudice or discrimination against people who are considered physically unattractive or whose physical appearance is believed to fall short of societal ideas of beauty.

An example of pretty-shaming is how attractive women are less likely to be hired for jobs in which they'd have positions of authority. And an example of lookism would be how unattractive people may receive fewer opportunities.

Food-shaming is generally done in relation to body size. For example, when someone makes a remark about what a person is or isn't eating, that can count as food-shaming. Someone saying, "They look like they don't need to be eating that," is an example of food-shaming.

You can also food-shame yourself. For example, you might say, "I'm so fat, I shouldn't eat this piece of cheesecake."

The 1980s saw the rise of spandex clothing, and there was a popular saying, "Spandex is a privilege, not a right." This meant that people should only wear spandex clothes if they had the "correct" body shape for them. This is a prime example of clothing-shaming.

More recently, the founder of the clothing brand Lululemon was criticized for making fat-shaming comments when he said that some women's bodies "don't work" for the clothes.

Also known as ageism, age-shaming is discrimination or bullying towards people because of their age. This usually focuses on the elderly or the older population.

In relation to body-shaming, an ageist remark may sound like, "They're too old to wear that much makeup." Additionally, news articles that show photos of how "bad" or "old" celebrities look when not wearing makeup are shaming. Making negative comments about someone's wrinkles or loose skin is another form of body-shaming.

Western society has long focused on sleek, shiny, straight hair as the ideal. Thus, hair with curls, kinks, or other textures has been viewed as less attractive. This is known as texture-shaming.

An example of texture shaming is, "They're so brave to wear their hair natural." While that sounds like a compliment, it's actually an insult. That's because it implies that a person's hair is outside what is considered normal and that they are courageous for wearing their hair in its natural state.

Additionally, bald-shaming happens to people of all genders who have receding hairlines or thinning/balding scalps.

Body shaming has myriad negative consequences on mental health. Here are some important ones:

- Adolescents who are body shamed have a significantly elevated risk of depression .

- It may lead to eating disorders.

- Body shaming worsens outcomes for obese women attempting to overcome binge eating.

- Body shaming can cause dissatisfaction with one's body, which then can cause low self-esteem .

Additional mental health concerns associated with body-shaming include:

- Body dysmorphic disorder

- Higher risk of self-harm or suicide

- Poorer quality of life (due to body dissatisfaction)

- Psychological distress

If you are having suicidal thoughts, contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988 for support and assistance from a trained counselor. If you or a loved one are in immediate danger, call 911.

For more mental health resources, see our National Helpline Database .

Body shaming may be rampant, but that doesn't mean you should take part in it. Making a point of not being a body shamer is the kinder option for all people, yourself included. Being intentional about not engaging in various types of shaming may lead to better mental wellness.

In addition to not body shaming, it can be helpful to be more body-inclusive. This means encouraging the acceptance and celebration of shape and diversity in appearance, focusing on health instead of size or weight, and appreciating the human body for all that it is and does.

Below are some ways you can stop contributing to body shaming culture.

Stop Talking About Other People's Bodies

It may be socially acceptable for people to mock and body-shame others, but you do not have to accept, participate in, or tolerate such words or actions. You wouldn't want that to be done to you, and now you know that it can cause real problems for those it happens to.

So, when you are tempted to point out a person's body hair or their hair texture, their size, stop yourself. Instead, why not think of something nice to say to the person?

Clearly, they caught your eye, so you could use this as an opportunity to find a positive attribute. "I like your smile" is one idea of a way to compliment another person without speaking negatively about their body.

Try the following steps:

- Notice your thoughts and acknowledge your own conditioning, bias, and/or judgments.

- Make an intentional effort to notice what you like, appreciate, or admire about this person (this may be physical or non-physical traits).

- Practice this with others and yourself to develop and deepen respect, care, and compassion for yourself and others.

Learn About Body Neutrality

Body neutrality is a practice that has many proven mental health benefits . It's the notion of accepting bodies as they are, without casting judgment on them. This can apply to your own body, and to the bodies of others.

Body neutrality encourages a focus on the positive functions that bodies can perform. Learning about it can make you feel better in your own body, improve your relationship with food, and boost your self-esteem.

Change How You Talk About Your Own Body

In a culture where so much emphasis is placed on what is wrong with us and needs improvement, it can feel like a huge challenge to speak positively about our own bodies. Doing so, however, is a healthy thing to do, and it also saves other people from harm.

By practicing speaking positively about ourselves and our bodies, and noticing qualities about ourselves and others that we like and appreciate, we can deepen our care, compassion, and connection with others and with ourselves.

When you make a comment like "I feel so fat today," you're making a judgment about fat people and implying their bodies are less valuable than the bodies of thin people. This can be hurtful for anyone around you, especially those who are larger.

It isn't realistic to only think positive thoughts about yourself, but you can express your feelings in ways that are less harmful to others. For the above example, you could instead confide in a friend and say, "My pants aren't fitting as they usually do, and it's making me feel self-conscious."

Rather than body-shaming, you'll have opened up to a loved one, creating more closeness and trust between the both of you.

If you've gone through the steps to stop body-shaming yourself and other people, that's wonderful! However, there is still more work to do.

As with all instances in life when you see other people causing harm, it's important to speak up—provided it is emotionally and physically safe for you to do so.

If you see someone making a comment to another person about their body, whether about their clothing or age or size, you can gently let them know that it's unkind to talk about other people's bodies. And if it happens regularly with friends or loved ones, you can bring it up in a bigger way, letting them know that their ways of communicating about bodies don't always feel good for you and others.

Body shaming may be prevalent, but you can do the work to stop perpetuating it and to help heal its harmful effects by practicing body positivity with yourself and others.

Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Body-Shaming .

Braun S, Peus C, Frey, D. Is beauty beastly? Gender-specific effects of leader attractiveness and leadership style on followers’ trust and loyalty . Zeitschrift für Psychologie. 2012; 220(2), 98–108. https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000101

Tietje L, Cresap S. Is Lookism Unjust?: The Ethics of Aesthetics and Public Policy Implications . The Journal of Libertarian Studies . 2010.

Throughline. Lululemon founder to women: Your thighs are too fat .

Brewis AA, Bruening M. Weight shame, social connection, and depressive symptoms in late adolescence . Int J Environ Res Public Health . 2018;15(5):891.

Vogel L. Fat shaming is making people sicker and heavier . CMAJ . 2019;191(23):E649. doi:10.1503/cmaj.109-5758

Palmeira L, Pinto-Gouveia J, Cunha M. The role of weight self-stigma on the quality of life of women with overweight and obesity: A multi-group comparison between binge eaters and non-binge eaters . Appetite . 2016;105:782-789.

van den Berg PA, Mond J, Eisenberg M, Ackard D, Neumark-Sztainer D. The link between body dissatisfaction and self-esteem in adolescents: Similarities across gender, age, weight status, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status . J Adolesc Health . 2010;47(3):290-296.

Gilbert P, Miles J. Body Shame: Conceptualisation, Research, and Treatment. New York, NY:Brunner-Routledge.

By Ariane Resnick, CNC Ariane Resnick, CNC is a mental health writer, certified nutritionist, and wellness author who advocates for accessibility and inclusivity.

Medical School

- MD Students

- Residents & Fellows

- Faculty & Staff

- Duluth Campus Leadership

- Department Heads

- Dean's Distinguished Research Lectureship

- Dean's Tribute to Excellence in Research

- Dean’s Tribute to Excellence in Education

- Twin Cities Campus

- Office of the Regional Dean

- Office of Research Support, Duluth Campus

- CentraCare Regional Campus St. Cloud

- Office of Diversity, Equity & Inclusion

- Office of Faculty Affairs

- Grant Support

- Medical Student Research Opportunities

- The Whiteside Institute for Clinical Research

- Office of Research, Medical School

- Graduate Medical Education Office

- Office of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies

- Departments

- Centers & Institutes

- Dr. James E. Rubin Medical Memorial Award

- Fisch Art of Medicine Student Awards

- Graduating Medical Student Research Award

- Veneziale-Steer Award

- Dr. Marvin and Hadassah Bacaner Research Awards

- Excellence in Geriatric Scholarship

- Distinguished Mentoring Award

- Distinguished Teaching Awards

- Cecil J. Watson Award

- Exceptional Affiliate Faculty Teaching Award

- Exceptional Primary Care Community Faculty Teaching Award

- Herz Faculty Teaching Development Awards

- The Leonard Tow Humanism in Medicine Awards

- Year 1+2 Educational Innovative Award

- Alumni Philanthropy and Service Award

- Distinguished Alumni Award

- Early Distinguished Career Alumni Award

- Harold S. Diehl Award

- Nomination Requirements

- Duluth Scholarships & Awards

- Account Management

- Fundraising Assistance

- Research & Equipment Grants

- Medical School Scholarships

- Student Research Grants

- Board members

- Alumni Celebration

- Alumni Relations - Meet the Team

- Diversity & Inclusion

- The Bob Allison Ataxia Research Center

- Children's Health

- Orthopaedics

- Regenerative Medicine

- Scholarships

- Transplantation

- MD Student Virtual Tour

- Why Minnesota?

- Facts & Figures

- Annika Tureson

- Caryn Wolter

- Crystal Chang

- Emily Stock

- Himal Purani

- Jamie Stang

- Jordan Ammons

- Julia Klein

- Julia Meyer

- Kirsten Snook

- Madison Sundlof

- Rashika K Shetty

- Rishi Sharma

- Savannah Maynard

- Prerequisite Courses

- Student National Medical Association Mentor Program

- Minority Association of Pre-Med Students

- Twin Cities Entering Class

- Next Steps: Accepted Students

- Degrees Offered

- Preceptor Resources (MD)

- Doctor of Physical Therapy (DPT)

- Message from the Director

- Clinical Training

- Curriculum & Timeline

- Integrated Physician Scientist Training

- MSTP Student Mentoring and Career Development

- External Fellowships

- Student Directory

- Student Advisory Committee

- Staff Directory

- Steering Committee

- Alumni Directory

- MSTP Student First Author Papers

- Thesis Defense

- MSTP Graduate Residency Match Information

- MSTP Code of Ethics

- Research Experience

- International Applicants

- Prerequisites

- Applicant Evaluation

- The Interview Process

- Application Process

- Financial Support

- Pre-MSTP Summer Research Program

- MSTP Virtual Tour

- Physician Scientist Training Programs

- Students with Disabilities

- Clinical Continuity & Mentoring Program

- Mental Health and Well-Being

- Leadership in Diversity Fellowship

- M1 and M2 Research Meeting

- Monthly Student Meetings

- MSTP Annual Retreat

- Preparation

- Women in Science & Medicine

- Graduate Programs/Institute Activities & Seminars

- CTSI Translational Research Development Program (TRDP)

- Grant Opportunities

- Graduate Programs

- Residencies & Fellowships

- Individualized Pathways

- Continuing Professional Development

- CQI Initiative

- Improvement Summary

- Quality Improvement Communication

- Student Involvement

- Student Voice

- Contact the Medical School Research Office

- Research Support

- Training Grants

- Veteran's Affairs (VA)

- ALPS COVID For Patients

- 3D/Virtual Reality Procedural Training

- Addressing Social Determinants of Health in the Age of COVID-19

- Augmented Reality Remote Procedural Training and Proctoring

- COVID19: Outbreaks and the Media

- Foundations in Health Equity

- Global Medicine in a Changing Educational World

- INMD 7013: COVID-19 Crisis Innovation Lab A course examining the COVID-19 crisis

- Intentional Observational Exercises - Virtual Critical Care Curriculum

- Live Suture Sessions for EMMD7500

- M Simulation to Provide PPE training for UMN students returning to clinical environments

- Medical Student Elective course: COVID-19 Contact Tracing with MDH

- Medical Students in the M Health Fairview System Operations Center

- Telehealth Management in Pandemics

- Telemedicine Acting Internship in Pediatrics

- The Wisdom of Literature in a Time of Plague

- Virtual Simulations for EMMD7500 Students

- COVID-19 Publications

- Blood & Marrow Transplant

- Genome Engineering

- Immunology & Infectious Disease

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- News & Events

- Support the Institute

- Lung Health

- Medical Discovery Team on Addiction Faculty

- Impact on Education

- Meet Our Staff

- Donation Criteria

- Health Care Directive Information

- Inquiry Form

- Other Donation Organizations

- Death Certificate Information

- Social Security Administration Notification and Death Benefit Information

- Grief Support

- Deceased Do Not Contact Registration and Preventing Identity Theft

- Service of Gratitude

- For Educators and Researchers

- Research Ethics

- Clinical Repository

- Patient Care

- Blue Ridge Research Rankings

- Where Discovery Creates Hope

Changing the Conversation: Body Shaming

Body shaming is a growing epidemic, rising to a fevered pitch in recent years alongside social media. Photos and advertisements of perfectly shaped and airbrushed bodies plaster the cities we live in, setting an unrealistic stigma for perfection. Even social media can play a role as people choose to share the best shots online, utilizing filters and editing apps to touch up their “reality.”

Within our current culture, there is an overwhelmingly negative attitude when it comes to individuals who live in larger bodies. Weight stigma and discrimination is a serious problem in a wide variety of contexts including work, school and care settings.

Katie Loth, Ph.D., M.P.H. , an assistant professor in the Department of Family Medicine and Community Health at the University of Minnesota Medical School, sees one major factor leading to the weight bias in our society.

“We live in a culture placing enormous value on thinness and physical beauty. Pop culture perpetuates this perceived importance by limiting the images we see to only those including individuals who match society’s high, often unattainable, expectations for physical appearance,” said Loth. “We need to demand the images we view are respectful and honest portrayals of real people, representing the full range of diversity within our culture.”

Research continually shows children and adults who experience body shaming are vulnerable to many long-lasting psychological and physical health consequences, including:

- Higher rates of depression and anxiety,

- Low self-esteem and low body satisfaction,

- Increased risk for suicidal thoughts and behaviors,

- Higher risk for disordered eating behaviors,

- More likely to avoid healthy behaviors such as physical activity.

According to Loth, it is important for parents, coaches and health professionals to stray away from having weight-focused conversations. Instead, she encourages conversations about setting behavioral goals, including encouraging healthy eating and regular physical activity. These conversations are more likely to result in positive long-term behavior change.

“We need to take a stand for our bodies,” concludes Loth. “We need to shift the public conversation away from the number on the scale and focus more on a much broader view of overall health.”

Home — Essay Samples — Social Issues — Body Shaming — Modern Concerns of Body Shaming

Modern Concerns of Body Shaming

- Categories: Body Shaming Bullying

About this sample

Words: 1048 |

Published: Aug 31, 2023

Words: 1048 | Pages: 2 | 6 min read

Table of contents

Introduction, historical context of body shaming, psychological impacts, perpetrators and media influence.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof. Kifaru

Verified writer

- Expert in: Social Issues

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

5 pages / 2332 words

3 pages / 1222 words

6 pages / 2615 words

3 pages / 1370 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Body Shaming

The digital age, with its myriad platforms, offers immense potential for positive change. However, it also presents challenges, with body shaming being a prime concern. As digital citizens, the onus is on us to foster positive [...]

Body shaming is a universal issue, manifesting differently across cultures. While the specifics may vary, the underlying theme remains the same: the pressure to conform to an often unattainable standard. Recognizing that this [...]

Someone the great firmly pointed out that; beauty has no size. Though the days of superstition has gone. But the shadow of prejudice is as dark as ever, with this unfaithful act of prejudice and discrimination people with higher [...]

Body shaming, though pervasive, is not insurmountable. With concerted efforts across educational, media, and personal domains, a future where every individual feels valued and accepted regardless of their body type is [...]

The European Convention on Human Rights(ECHR) is an international treaty which was drafted in 1950 in order to protect human rights and fundamental freedoms within Europe. Many countries signed up to this convention including [...]

The Central African Republic (CAR) continues to work towards the capacity of the government in regards to human trafficking. Various aspects such as violent conflict, extreme poverty, strong demand for labor in the informal [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Philippine E-Journals

Home ⇛ psychology and education: a multidisciplinary journal ⇛ vol. 7 no. 9 (2023), demystifying the encounters of teenagers on body shaming.

Richelle Jie Paña | Nisil Ofianga | Dan Mark Oracoy | Alexa Samantha Andulana | Jenifer Alcomendras | Jean Claude Avanceña | Kier Garcia | Jonathan Peñaflor | Fritz Gerard Mondragon

Discipline: Education

This study revolves around the encounters of teenagers regarding body shaming. Specifically, the study determines the teenagers' coping mechanisms and their insights on body shaming. The purpose of this study is to highlight the detrimental role of body shaming among teenagers, which is consistent with the fact that it frequently causes low self-esteem, low body dissatisfaction, and depressive symptoms among teenagers in the Municipality of Midsayap. Purposive sampling was used, including six teenagers selected per sex category, living in the Municipality of Midsayap, aged 13-19. This study utilized a qualitative research design through one- on-one interviews, specifically phenomenological. Data were analyzed through the thematic analysis of Braun and Clarke (2006) . Study showed that insecurities about body weight, unhealthy eating habits, insulting comments, low self-esteem, mental health issues, and distracted academic responsibilities were the challenges encountered by teenagers. Moreover, it was also revealed that teenagers cope with challenges by embracing themselves, seeking help to lose weight, unwinding, avoiding social media, and unhealthy eating habits and sleep schedules. In addition, results showed that ceasing body shaming, being sensitive, minding one's own body, and building one's self-confidence were the insights of teenagers on body shaming as a victim of it. The study's findings led the researchers to conclude that body shaming can damage and leave lifelong trauma to the teenager's mental, physical, and social well-being. With the presented information, programs relating to body weight diversity and body shaming awareness should be implemented to lessen body shaming in society.

Share Article:

ISSN 2822-4353 (Online)

- Citation Generator

- ">Indexing metadata

- Print version

Copyright © 2024 KITE E-Learning Solutions | Exclusively distributed by CE-Logic | Terms and Conditions

Body Positivity as an Answer to Body Shaming Essay

Introduction, adverse trends in social media and their impact, body positivity as an optimal solution, works cited.

Living in a present-day society means following its trends, which are frequently completely irrational and, what is more important, harmful to young people. One of them is the establishment of beauty standards and their fast development, which is conditional upon the involvement of social media platforms, such as Instagram or Twitter. This phenomenon leads to body shaming as a response to one’s unwillingness or inability to adjust to these imaginary rules. As a result, individuals begin to suffer from low self-esteem, which adversely affects their functioning as citizens, whereas highlighting their uniqueness might have the opposite outcome. Therefore, the best solution for eliminating the unrealistic expectations for one’s looks is the emphasis on body positivity, which can contribute to a shift from the need to conform to self-appreciation regardless of external factors.

The mentioned adverse trends in social media are connected to the erroneous perceptions of individuality by people. They are especially critical for adolescents who pay particular attention to their appearance in their pursuit of being unique compared to their families or friends. However, the failure to follow the instilled standards leads to their dissatisfaction with their bodies, which complicates the already challenging process of pubertal adjustment (Gam et al. 1325). In this case, the problem is in the fact that common views on beauty do not correlate with individuality, as it might seem to youngsters. Consequently, their distorted understanding of this aspect and the desire to express themselves are in conflict. In addition, all teenagers are susceptible to body shaming stemming from non-compliance with ideals, and children from prosperous families struggle as much as their less fortunate peers. Therefore, a change is required for ensuring their mental health and well-being in the future.

Another circumstance contributing to the negative impact of beauty standards in social media on people’s lives is the increased possibility of personal conflicts, which emerge on these grounds. It can be dangerous for the socialization of young citizens and disrupt the process of their personality formation, which, in turn, will result in their inability to find their place in life (Martínez-González et al. 6630). Even though the creation of the desired image is a necessary task for everyone, it should not be based on any rules other than the freedom of self-expression and the emphasis on individuality. In this situation, body positivity seems an excellent solution since it corresponds to the above provisions. Thus, the described problems, which are the inability to distinguish between irrational standards and individuality and the issues with one’s image, are the basis of why body-shaming is a negative phenomenon in society.

The significance of body positivity for addressing the challenges describes above can be explained by its capability to resist the influence of irrational beauty standards. The latter is well-developed and widely supported by social media, which means that they can be overcome only through a movement, which is efficient and publicly known. At present, there are no other alternatives except for the introduction of body positivity for this purpose, and this conclusion is supported by scholars. Thus, for example, they claim that listening to body-positive music adds to women’s self-esteem, whereas the preference for appearance-related songs has the opposite effect (Coyne et al. 5). These findings indicate the effectiveness of the selected approach in changing the stereotypes, which are proved to be harmful to young people. Therefore, the emphasis on cultural products reflecting individuality rather than the need to conform to beauty standards might eliminate the risks of body shaming.

Moreover, the attitudes of individuals towards appearance and the appropriateness of specific trends are frequently transmitted through popular types of physical activity, which should also be addressed with regard to the principles of body positivity. According to Pickett and Cunningham, the introduction of body-positive yoga is one of the methods, which can be suitable for this objective (336). It contributes to the creation of inclusive physical activity spaces based on people’s individuality rather than shared standards and body shaming for non-compliance with them (Pickett and Cunningham 336). In this way, this aspect of human life can be viewed as one of the most influential areas, which should be highlighted by facilities providing similar services to the population. Their focus on the promotion of acceptance and individuality of visitors is beneficial for the formation of a positive body image. It also adds to the fact that the shift in attitudes can resolve the issues emerging due to the spread of unrealistic standards.