Chinese Culture

China is one of the Four Ancient Civilizations (alongside Babylon, India and Egypt), according to Chinese scholar Liang Qichao (1900). It boasts a vast and varied geographic expanse, 3,600 years of written history, as well as a rich and profound culture. Chinese culture is diverse and unique, yet harmoniously blended — an invaluable asset to the world.

Our China culture guide contains information divided into Traditions, Heritage, Arts, Festivals, Language, and Symbols. Topics include Chinese food, World Heritage sites, China's Spring Festival, Kungfu, and Beijing opera.

China's Traditions

China's heritage.

China's national heritage is both tangible and intangible, with natural wonders and historic sites, as well as ethnic songs and festivals included.

As of 2018, 53 noteworthy Chinese sites were inscribed on UNESCO's World Heritage List: 36 Cultural Heritage, 13 Natural Heritage, and 4 Cultural and Natural Heritage .

China's Performing Arts

- Chinese Kungfu

- Chinese Folk Dance

- Chinese Traditional Music

- Chinese Acrobatics

- Beijing Opera

- Chinese Shadow Plays

- Chinese Puppet Plays

- Chinese Musical Instruments

Arts and Crafts

- Chinese Silk

- Chinese Jade Articles

- Ancient Chinese Furniture

- Chinese Knots

- Chinese Embroidery

- Chinese Lanterns

- Chinese Kites

- Chinese Paper Cutting

- Chinese Paper Umbrellas

- Ancient Porcelain

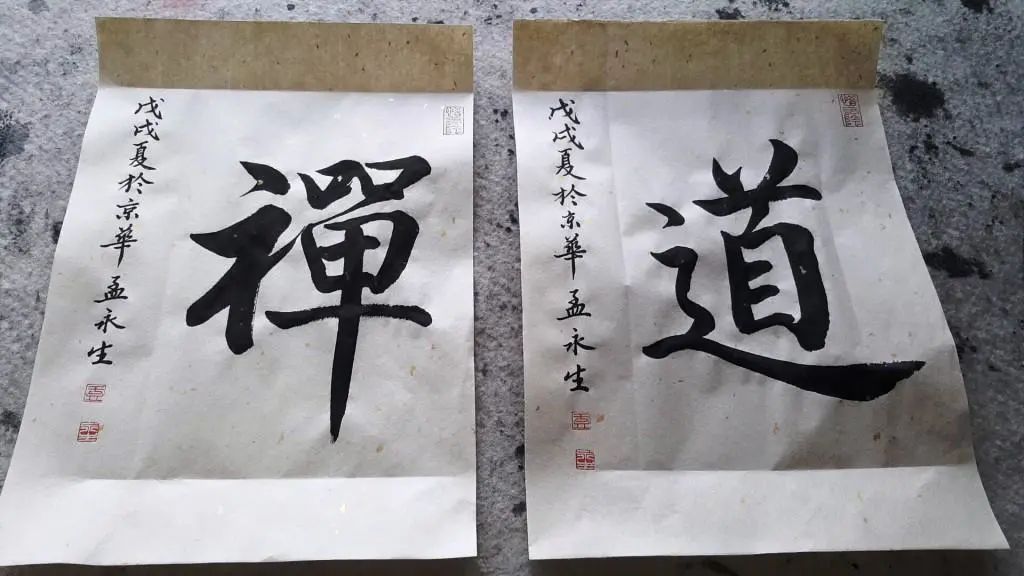

- Chinese Calligraphy

- Chinese Painting

- Chinese Cloisonné

- Four Treasures of the Study

- Chinese Seals

China's Festivals

China has several traditional festivals that are celebrated all over the country (in different ways). The most important is Chinese New Year, then Mid-Autumn Festival. China, with its "55 Ethnic Minorities", also has many ethnic festivals. From Tibet to Manchuria to China's tropical south, different tribes celebrate their new year, harvest, and other things, in various ways.

Learning Chinese

Chinese is reckoned to be the most difficult language in the world to learn, but that also must make it the most interesting. It's the world's only remaining pictographic language in common use, with thousands of characters making up the written language. Its pronunciation is generally one syllable per character, in one of five tones. China's rich literary culture includes many pithy sayings and beautiful poems.

Symbols of China

Every nation has its symbols, but what should you think of when it comes to China? You might conjure up images of long coiling dragons, the red flag, pandas, the Great Wall… table tennis, the list goes on…

Top Recommended Chinese Culture Tours

- China's classic sights

- A silent night on the Great Wall

- Relaxing in China's countryside

- China's past, present, and future

- The Terracotta Amy coming alive

- Experience a high-speed train ride

- Feed a lovely giant panda

- Explore China's classic sights

- Relax on a Yangtze River cruise

- Walk on the the Great Wall.

- Make a mini warrior with a local family.

- Pay your respects at the pilgrim's holy palace.

Get Inspired with Some Popular Itineraries

More Travel Ideas and Inspiration

Sign up to our newsletter.

Be the first to receive exciting updates, exclusive promotions, and valuable travel tips from our team of experts.

Why China Highlights

Where Can We Take You Today?

- Southeast Asia

- Japan, South Korea

- India, Nepal, Bhutan, and Sri lanka

- Central Asia

- Middle East

- African Safari

- Travel Agents

- Loyalty & Referral Program

- Privacy Policy

Address: Building 6, Chuangyi Business Park, 70 Qilidian Road, Guilin, Guangxi, 541004, China

Chinese Culture: Customs & Traditions of China

China is an extremely large country — first in population and fifth in area, according to the CIA — and the customs and traditions of its people vary by geography and ethnicity.

About 1.4 billion people live in China, according to the World Bank, representing 56 ethnic minority groups. The largest group is the Han Chinese, with about 900 million people. Other groups include the Tibetans, the Mongols , the Manchus, the Naxi, and the Hezhen, which is smallest group, with fewer than 2,000 people.

"Significantly, individuals within communities create their own culture," said Cristina De Rossi, an anthropologist at Barnet and Southgate College in London. Culture includes religion, food, style, language, marriage, music, morals and many other things that make up how a group acts and interacts. Here is a brief overview of some elements of the Chinese culture.

The Chinese Communist Party that rules the nation is officially atheist, though it is gradually becoming more tolerant of religions, according to the Council on Foreign Relations . Currently, there are only five official religions. Any religion other than Buddhism, Taoism, Islam, Catholicism and Protestantism are illegal, even though the Chinese constitution states that people are allowed freedom of religion. The gradual tolerance of religion has only started to progress in the past few decades.

About a quarter of the people practice Taoism and Confucianism and other traditional religions. There are also small numbers of Buddhists, Muslims and Christians. Although numerous Protestant and Catholic ministries have been active in the country since the early 19th century, they have made little progress in converting Chinese to these religions.

The cremated remains of someone who may have been the Buddha were discovered in Jingchuan County, China, with more than 260 Buddhist statues in late 2017. Buddha was a spiritual teacher who lived between mid-6th and mid-4th centuries B.C. His lessons founded Buddhism. [ Cremated Remains of the 'Buddha' Discovered in Chinese Village ]

There are seven major groups of dialects of the Chinese language, which each have their own variations, according to Mount Holyoke College . Mandarin dialects are spoken by 71.5 percent of the population, followed by Wu (8.5 percent), Yue (also called Cantonese; 5 percent), Xiang (4.8 percent), Min (4.1 percent), Hakka (3.7 percent) and Gan (2.4 percent).

Chinese dialects are very different, according to Jerry Norman, a former professor of linguistics at the University of Washington and author of " Chinese (Cambridge Language Surveys) " (Cambridge University Press, 1988). "Chinese is rather more like a language family than a single language made up of a number of regional forms," he wrote. "The Chinese dialectal complex is in many ways analogous to the Romance language family in Europe. To take an extreme example, there is probably as much difference between the dialects of Peking [Beijing] and Chaozhou as there is between Italian and French."

The official national language of China is Pŭtōnghuà, a type of Mandarin spoken in the capital Beijing, according to the Order of the President of the People's Republic of China . Many Chinese are also fluent in English.

Like other aspects of Chinese life, cuisine is heavily influenced by geography and ethnic diversity. Among the main styles of Chinese cooking are Cantonese, which features stir-fried dishes, and Szechuan, which relies heavily on use of peanuts, sesame paste and ginger and is known for its spiciness.

Rice is not only a major food source in China; it is also a major element that helped grow their society, according to " Pathways to Asian Civilizations: Tracing the Origins and Spread of Rice and Rice Cultures ," an 2011 article in the journal Rice by Dorian Q. Fuller. The Chinese word for rice is fan , which also means "meal," and it is a staple of their diet, as are bean sprouts, cabbage and scallions. Because they do not consume a lot of meat — occasionally pork or chicken — tofu is a main source of protein for the Chinese.

Chinese art is greatly influenced by the country's rich spiritual and mystical history. Many sculptures and paintings depict spiritual figures of Buddhism, according to the Metropolitan Museum of Art .

Many musical instruments are integral to Chinese culture, including the flute-like xun and the guqin, which is in the zither family.

Eastern-style martial arts were also developed in China, and it is the birthplace of kung fu. This fighting technique is based on animal movements and was created in the mid-1600s, according to Black Belt Magazine .

Ancient Chinese were avid writers and philosophers — especially during the Ming and Qing dynasties — and that is reflected in the country's rich liturgical history.

Recently, archaeologists discovered detailed paintings in a 1,400-year-old tomb in China. "The murals of this tomb had diversified motifs and rich connotations, many of which cannot be found in other tombs of the same period," a team of archaeologists wrote in an article recently published in a 2017 issue of the journal Chinese Archaeology. [ Ancient Tomb with 'Blue Monster' Mural Discovered in China ]

Science & technology

China has invested large amounts of money in science advancements and currently challenges the United States in scientific research . China spent 75 percent of what the United States spent in 2015, according to the journal JCI Insight .

One recent 2017 development in Chinese science is teleportation. Chinese researchers sent a packet of information from Tibet to a satellite in orbit, up to 870 miles (1,400 kilometers) above the Earth's surface, which is a new record for quantum teleportation distance. [ Chinese Scientists Just Set the Record for the Farthest Quantum Teleportation ]

Another 2017 advancement is the development of new bullet trains. Dubbed "Fuxing," which means "rejuvenation," these trains are high-speed transportation systems that run between Beijing and Shanghai. The trains can travel at speeds of up to 350 km/h (217 mph), making them the world's fastest trains. [ China's 'Rejuvenation' Bullet Trains Are the World's Fastest ]

Customs and celebrations

The largest festival — also called the Spring Festival — marks the beginning of the Lunar New Year. It falls between mid-January and mid-February and is a time to honor ancestors. During the 15-day celebration, the Chinese do something every day to welcome the new year, such as eat rice congee and mustard greens to cleanse the body, according to the University of Victoria . The holiday is marked with fireworks and parades featuring dancers dressed as dragons.

Many people make pilgrimages to Confucius' birthplace in Shandong Province on his birthday, Sept. 28. The birthday of Guanyin, the goddess of mercy, is observed by visiting Taoist temples. It falls between late March and late April. Similar celebrations mark the birthday of Mazu, the goddess of the sea (also known as Tianhou), in May or June. The Moon Festival is celebrated in September or October with fireworks, paper lanterns and moon gazing.

Additional resources

- Princeton University: The Spirits of Chinese Religion

- University of Mississippi: Ming and Qing Dynasties

- University of Minnesota: What is Culture?

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Kim Ann Zimmermann is a contributor to Live Science and sister site Space.com, writing mainly evergreen reference articles that provide background on myriad scientific topics, from astronauts to climate, and from culture to medicine. Her work can also be found in Business News Daily and KM World. She holds a bachelor’s degree in communications from Glassboro State College (now known as Rowan University) in New Jersey.

14 best science books for kids and young adults

'I'm as happy as I've ever been in my life': Why some people feel happiness near death

Massive sinkholes in China hold 'heavenly' forests with plants adapted for harsh life underground

Most Popular

- 2 No, NASA hasn't warned of an impending asteroid strike in 2038. Here's what really happened.

- 3 Milky Way's black hole 'exhaust vent' discovered in eerie X-ray observations

- 4 NASA offers SpaceX $843 million to destroy the International Space Station

- 5 Which continent has the most animal species?

- 2 This robot could leap higher than the Statue of Liberty — if we ever build it properly

- 3 Zany polar bears and a '3-headed' giraffe star in Nikon Comedy Wildlife Awards

- 4 Which continent has the most animal species?

- 5 Newly discovered asteroid larger than the Great Pyramid of Giza will zoom between Earth and the moon on Saturday

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Quick Facts

- The Northeast Plain

- The Changbai Mountains

- The North China Plain

- The Loess Plateau

- The Shandong Hills

- The Qin Mountains

- The Sichuan Basin

- The southeastern mountains

- Plains of the middle and lower Yangtze

- The Nan Mountains

- The Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau

- The Plateau of Tibet

- The Tarim Basin

- The Junggar Basin

- The Tien Shan

- The air masses

- Temperature

- Precipitation

- Animal life

- Ethnic groups

- Sino-Tibetan

- Other languages

- Rural areas

- Urban areas

- Population growth

- Population distribution

- Internal migration

- The role of the government

- Economic policies

- Farming and livestock

- Forestry and fishing

- Hydroelectric potential

- Energy production

- Manufacturing

- Labor and taxation

- Road networks

- Port facilities and shipping

- Posts and telecommunications

- Parallel structure

- Constitutional framework

- Role of the CCP

- Administration

- Health and welfare

- Cultural milieu

- Visual arts

- Performing arts

- Cultural institutions

- Daily life, sports, and recreation

- Media and publishing

- Archaeology in China

- Early humans

- Climate and environment

- Food production

- Incipient Neolithic

- 6th millennium bce

- 5th millennium bce

- 4th and 3rd millennia bce

- Regional cultures of the Late Neolithic

- Religious beliefs and social organization

- The advent of bronze casting

- Royal burials

- The chariot

- Late Shang divination and religion

- State and society

- Zhou and Shang

- The Zhou feudal system

- The decline of feudalism

- Urbanization and assimilation

- The rise of monarchy

- Economic development

- Cultural change

- The Qin state

- Struggle for power

- Prelude to the Han

- The imperial succession

- From Wudi to Yuandi

- From Chengdi to Wang Mang

- Dong (Eastern) Han

- The civil service

- Provincial government

- The armed forces

- The practice of government

- Relations with other peoples

- Cultural developments

- Sanguo (Three Kingdoms; 220–280 ce )

- The Xi (Western) Jin (265–316/317 ce )

- The Dong (Eastern) Jin (317–420) and later dynasties in the south (420–589)

- The Shiliuguo (Sixteen Kingdoms) in the north (303–439)

- Confucianism and philosophical Daoism

- Wendi’s institutional reforms

- Integration of the south

- Foreign affairs under Yangdi

- Administration of the state

- Fiscal and legal system

- The “era of good government”

- Rise of the empress Wuhou

- Prosperity and progress

- Military reorganization

- Provincial separatism

- The struggle for central authority

- The influence of Buddhism

- Trends in the arts

- Decline of the aristocracy

- Population movements

- Growth of the economy

- The Wudai (Five Dynasties)

- The Shiguo (Ten Kingdoms)

- Unification

- Consolidation

- Decline and fall

- Survival and consolidation

- Relations with the Juchen

- The court’s relations with the bureaucracy

- The chief councillors

- The bureaucratic style

- The clerical staff

- The rise of neo-Confucianism

- Internal solidarity during the decline of the Nan Song

- Song culture

- Invasion of the Jin state

- Invasion of the Song state

- Early Mongol rule

- Changes under Kublai Khan and his successors

- Foreign religions

- Confucianism

- Yuan China and the West

- The end of Mongol rule

- The dynasty’s founder

- The dynastic succession

- Local government

- Central government

- Later innovations

- Foreign relations

- Agriculture

- Philosophy and religion

- Literature and scholarship

- The rise of the Manchu

- Political institutions

- Social organization

- Trends in the early Qing

- The first Opium War and its aftermath

- The anti-foreign movement and the second Opium War (Arrow War)

- The Taiping Rebellion

- The Nian Rebellion

- Muslim rebellions

- Effects of the rebellions

- Foreign relations in the 1860s

- Industrialization for “self-strengthening”

- East Turkistan

- Tibet and Nepal

- Myanmar (Burma)

- Japan and the Ryukyu Islands

- Korea and the Sino-Japanese War

- The Hundred Days of Reform of 1898

- The Boxer Rebellion

- Sun Yat-sen and the United League

- Constitutional movements after 1905

- The Chinese Revolution (1911–12)

- Early power struggles

- Japanese gains

- Yuan’s attempts to become emperor

- Conflict over entry into the war

- Formation of a rival southern government

- Wartime changes

- An intellectual revolution

- Riots and protests

- The Nationalist Party

- The Chinese Communist Party

- Communist-Nationalist cooperation

- Militarism in China

- The foreign presence

- Reorganization of the KMT

- Clashes with foreigners

- KMT opposition to radicals

- The Northern Expedition

- Expulsion of communists from the KMT

- Japanese aggression

- War between Nationalists and communists

- The United Front against Japan

- Phase two: stalemate and stagnation

- Renewed communist-Nationalist conflict

- U.S. aid to China

- Conflicts within the international alliance

- Phase three: approaching crisis (1944–45)

- Nationalist deterioration

- Communist growth

- Efforts to prevent civil war

- Attempts to end the war

- Resumption of fighting

- A land revolution

- The decisive year, 1948

- Communist victory

- Reconstruction and consolidation, 1949–52

- Rural collectivization

- Urban socialist changes

- Political developments

- Foreign policy

- New directions in national policy, 1958–61

- Readjustment and reaction, 1961–65

- Attacks on cultural figures

- Attacks on party members

- Seizure of power

- The end of the radical period

- Social changes

- Struggle for the premiership

- Consequences of the Cultural Revolution

- Readjustment and recovery

- Economic policy changes

- Educational and cultural policy changes

- COVID-19 outbreak

- Allegations of human rights abuses

- International relations

- Relations with Taiwan

- Leaders of the People’s Republic of China since 1949

What are the major ethnic groups in China?

- Who was Mao Zedong?

- What is Maoism?

- How has China changed since Mao Zedong’s death?

- What is Mao Zedong's legacy?

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- National Geographic Kids - 30 cool facts about China!

- Central Intelligence Agency - The World Factbook - China

- China - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- China - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

How big is China?

China, the largest of all Asian countries, occupies nearly the entire East Asian landmass and covers approximately one-fourteenth of the land area of Earth, making it almost as large as the whole of Europe.

China, which has the largest population of any country in the world, is composed of diverse ethnic and linguistic groups. The Han are the largest group in China, while the Zhuang is the largest minority group. In some areas of China, especially in the southwest, many different ethnic groups are geographically intermixed, including Buyi, Miao, Dong, Tibetans, Mongolians, and others.

Does China have an official language?

The official language of China is Mandarin, or putonghua , meaning “ordinary language” or “common language.” There are three variants of Mandarin—Beijing, Chengdu, and Nanjing. Of these, the Beijing dialect is the most widespread Chinese tongue and has officially been adopted as the basis for the national language.

How long has China existed as a discrete politico-cultural unit?

With more than 4,000 years of recorded history, China is one of the few existing countries that also flourished economically and culturally in the earliest stages of world civilization. China is unique among nations in its longevity and resilience as a discrete politico-cultural unit.

What crops are grown in China?

China is the world’s largest producer of rice and is among the principal sources of wheat, corn (maize), tobacco, soybeans, peanuts (groundnuts), and cotton.

China , country of East Asia . It is the largest of all Asian countries. Occupying nearly the entire East Asian landmass, it covers approximately one-fourteenth of the land area of Earth , and it is almost as large as the whole of Europe . China is also one of the most populous countries in the world, rivaled only by India , which, according to United Nations estimates, surpassed it in population in 2023.

China has 33 administrative units directly under the central government; these consist of 22 provinces , 5 autonomous regions, 4 municipalities ( Chongqing , Beijing , Shanghai , and Tianjin ), and 2 special administrative regions ( Hong Kong and Macau ). The island province of Taiwan , which has been under separate administration since 1949, is discussed in the article Taiwan . Beijing (Peking), the capital of the People’s Republic, is also the cultural, economic, and communications center of the country. Shanghai is the main industrial city; Hong Kong is the leading commercial center and port.

Recent News

Within China’s boundaries exists a highly diverse and complex country. Its topography encompasses the highest and one of the lowest places on Earth, and its relief varies from nearly impenetrable mountainous terrain to vast coastal lowlands . Its climate ranges from extremely dry, desertlike conditions in the northwest to tropical monsoon in the southeast, and China has the greatest contrast in temperature between its northern and southern borders of any country in the world.

The diversity of both China’s relief and its climate has resulted in one of the world’s widest arrays of ecological niches , and these niches have been filled by a vast number of plant and animal species. Indeed, practically all types of Northern Hemisphere plants, except those of the polar tundra, are found in China, and, despite the continuous inroads of humans over the millennia, China still is home to some of the world’s most exotic animals.

Probably the single most identifiable characteristic of China to the people of the rest of the world is the size of its population. Some one-fifth of humanity is of Chinese nationality. The great majority of the population is Chinese (Han), and thus China is often characterized as an ethnically homogeneous country, but few countries have as many diverse Indigenous peoples as does China. Even among the Han there are cultural and linguistic differences between regions; for example, the only point of linguistic commonality between two individuals from different parts of China may be the written Chinese language. Because China’s population is so enormous, the population density of the country is also often thought to be uniformly high, but vast areas of China are either uninhabited or sparsely populated.

With more than 4,000 years of recorded history , China is one of the few existing countries that also flourished economically and culturally in the earliest stages of world civilization. Indeed, despite the political and social upheavals that frequently have ravaged the country, China is unique among nations in its longevity and resilience as a discrete politico-cultural unit. Much of China’s cultural development has been accomplished with relatively little outside influence, the introduction of Buddhism from India constituting a major exception. Even when the country was penetrated by such foreign powers as the Manchu , these groups soon became largely absorbed into the fabric of Han Chinese culture .

This relative isolation from the outside world made possible over the centuries the flowering and refinement of the Chinese culture, but it also left China ill prepared to cope with that world when, from the mid-19th century, it was confronted by technologically superior foreign nations. There followed a century of decline and decrepitude, as China found itself relatively helpless in the face of a foreign onslaught. The trauma of this external challenge became the catalyst for a revolution that began in the early 20th century against the old regime and culminated in the establishment of a communist government in 1949. This event reshaped global political geography, and China has since come to rank among the most influential countries in the world.

Central to China’s long-enduring identity as a unitary country is the province, or sheng (“secretariat”). The provinces are traceable in their current form to the Tang dynasty (618–907 ce ). Over the centuries, provinces gained in importance as centers of political and economic authority and increasingly became the focus of regional identification and loyalty. Provincial power reached its peak in the first two decades of the 20th century, but, since the establishment of the People’s Republic, that power has been curtailed by a strong central leadership in Beijing. Nonetheless, while the Chinese state has remained unitary in form, the vast size and population of China’s provinces—which are comparable to large and midsize nations—dictate their continuing importance as a level of subnational administration.

China stretches for about 3,250 miles (5,250 km) from east to west and 3,400 miles (5,500 km) from north to south. Its land frontier is about 12,400 miles (20,000 km) in length, and its coastline extends for some 8,700 miles (14,000 km). The country is bounded by Mongolia to the north; Russia and North Korea to the northeast; the Yellow Sea and the East China Sea to the east; the South China Sea to the southeast; Vietnam , Laos , Myanmar (Burma), India , Bhutan , and Nepal to the south; Pakistan to the southwest; and Afghanistan , Tajikistan , Kyrgyzstan , and Kazakhstan to the west. In addition to the 14 countries that border directly on it, China also faces South Korea and Japan , across the Yellow Sea, and the Philippines , which lie beyond the South China Sea.

- AsianStudies.org

- Annual Conference

- EAA Articles

- 2025 Annual Conference March 13-16, 2025

- AAS Community Forum Log In and Participate

Education About Asia: Online Archives

Bringing traditional chinese culture to life.

This issue of Education About Asia addresses the question, “What should we know about Asia?” Based on my experiences teaching courses on China and East Asia, traditional Chinese culture is one of the most important topics in understanding both past and present Asia. China has one of the world’s oldest civilizations. This poses many challenges to teachers who desire to make this rich and complex tradition accessible to their students. On both a temporal and spatial level, traditional China may seem far removed to Western students of the modern world. To bridge these gaps in time and space, and to make it more relevant to my students, I often connect its significance to contemporary society by highlighting the current appeal of learning about traditional Chinese culture in modern China. To demonstrate this process, this article examines examples from three cultural fields: Chinese philosophy, focusing on Confucius and his thought; Chinese history, with an illustration from the Shiji ; and Chinese literature, with a case study on plum blossom poems. Moreover, this article discusses how to develop course questions that are relevant to the students’ needs, as well as how to update teaching styles by incorporating multimedia sources, such as current news and films, in the classroom in order to appeal to students of the digital age. Furthermore, the examples and approaches outlined in this article are applicable to a wide variety of courses, including, but not limited to, Chinese literature, history, philosophy, or world history. It is hoped that this article may therefore encourage teachers across many disciplines to incorporate these techniques, as well as their own innovations, in their classrooms.

Confucius and His Thought

Confucian thought played an important role in shaping Chinese culture and identity. In order to make this complex philosophy more engaging, I utilize the “What Did Confucius Say?” articles from the Asia for Educators website, which is hosted by Columbia University.1 This reading material is concise and contains seven major sections grouped according to various topics, including primary sources and discussion questions. The first two sections cover the life and major ideas of Confucius, and provide the background and main features of the Analects of Confucius . For instance, the reading informs users that the Analects of Confucius is not a single work composed by Confucius (551–479 BCE) during his lifetime, but rather multiple writings compiled by Confucius’s disciples after his death. The Analects are also a useful starting point for students to encounter traditional Chinese culture due to the format of the text itself. Students frequently perceive that in many of these stories, Confucius engages in either a monologue or a conversation with his disciples or a ruler to articulate his ideas. Moreover, Confucius’s words are terse and concise, leaving room for various interpretations, thereby promoting a lively class discussion.

When designing class activities, I include some of the discussion questions from the reading material on the website into my own questions in order to unpack both the meaning of his sayings in their own cultural context, as well as their current appeal in contemporary society. These questions are well-designed for high school and undergraduate instructors. The first few questions come from the website and are always based on a primary source in order to ensure the students understand the text. I then follow up these general comprehension questions with my own questions in order to place Confucius’s sayings into a larger intellectual and social context by asking students to apply Confucian thought to modern and contemporary issues. To prepare for class discussion, I may ask students to read some passages together or invite individual students to take turns reading them aloud, followed by their interpretations of the text’s meaning and broader significance. For example, one primary source comes from “On Confucius as Teacher and Person,” which includes Confucius’s sayings on education. I assign students the following discussion questions:

- Why is Confucius often called a great teacher? Please note several qualities of Confucius’s teaching philosophy as demonstrated by his sayings.

- If Confucius were your teacher today, how would you evaluate his teaching approaches and methods? Would you want to attend his class? Why or why not? Students are then able to discuss these questions based on a close reading of the document itself. For instance, the students learn that Confucius broke away from the traditional education system of his time, which had been limited to teaching the sons of noble families. In contrast, he allegedly would teach anyone who was willing to learn. In addition, he taught students with different approaches according to their own situations and characters. As a teacher, he showed his eagerness to learn from other people and improve his knowledge and skills, stating that “Walking along with three people, my teacher is sure to be among them.”2

Another important Confucian thought is the concept of ren (humanity). In this section, I demonstrate that some of Confucius’s sayings possess universal value, and thus, everyone can relate Confucius’s primary beliefs regardless of their own personal knowledge and backgrounds. The discussion questions below are used to facilitate students’ understanding of this concept and allow them to compare it to other traditions:

- Based on the reading section, what qualities does humanity include? Could you use some examples to illustrate Confucius’s ideas on humanity?

- Humanity is a universal value in many philosophies and religions. Please discuss the similarities and differences between Confucians’ humanity and other traditions that you are familiar with, such as Christianity or Buddhism. Although Confucius’s beliefs, such as humanity, have many similarities with other philosophical and religious traditions, some of Confucius’s values, such as filial piety, are different from Western cultural traditions. Filial piety is the core of Confucian moral philosophy, but it may be difficult for students outside of the Chinese tradition to understand, thus instructors must explain it and similar concepts in detail. To this end, I provide the following discussion questions:

- What are the major ideas of Confucius’s filial piety?

- Why do Chinese rulers promote and advocate this concept?

- If you were to apply filial piety to your family, what would happen? Do you think that filial piety applies to modern Western society? Why or why not?

To make these abstract concepts more concrete, I also ask students to offer specific examples to explain filial piety and its reciprocity. For instance, Confucius teaches that younger family members should respect their family elders, and in return, the elders have an obligation to take care of their younger family members. When explaining this, instructors should emphasize that this kind of relationship is hierarchical and that it was later advocated by rulers in different dynasties to legitimize their power by equating the ruler to the head of the family. When discussing filial piety, the instructor must also highlight its societal significance and philosophical ramifications. For instance, Confucian scholars maintained that if family members showed filial piety, then they would become peaceful and harmonious. Moreover, because society consists of many small families that make up the state, following this logic, a society that practices filial piety will naturally become well organized. Therefore, these scholars argued, a ruler should not rely on severe laws and regulations to govern his state; instead, a ruler should lead by exemplary deeds and moral values. Thus, students will learn that Confucian values such as filial piety affected all aspects of traditional Chinese culture, from the individual household to the governing state itself.

After students have grappled with the original texts and their historical significance, I then assign them Jeremy Page’s 2015 Wall Street Journal article “Why China Is Turning Back to Confucius”3 in order to further demonstrate the current appeal of Confucian thought on modern Chinese society. Page begins by describing a lecture on Chinese philosophy that many senior Chinese officials attended in order to further understand Confucian values and how to apply them in their daily lives. He then discusses the causes behind this revival of traditional Chinese culture (i.e., Confucianism), such as coping with domestic social problems, legitimating the Communist Party’s rule by arguing that it has inherited the Confucian tradition, and opposing Western influence. In addition, the article briefly traces the reception of Confucianism from the 1840s to the present and discusses many ways that contemporary Chinese society commemorates Confucius, such as establishing monuments, opening Confucian academies and training centers, and holding museum exhibitions and lectures.

In class, I first briefly discuss Confucius’s fluctuating status from the late Qing dynasty (1644–1911) to the end of the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), when his thought was largely criticized and condemned. This provides a historical context behind the return that contemporary Chinese society is making toward the study and appreciation of Confucian ideology. It also enables students to understand how the traditional Confucian value of obeying a ruler’s orders is being utilized to keep the present government in power . As students discuss this article, many observe that the top Chinese leaders attend Confucian classics courses and workshops, and even tune in to national television broadcasts and lectures on Confucian thought during primetime. In addition, they discover that school textbooks include more materials that encompass traditional values, and parents send their children to learn Confucian rituals as part of their extracurricular activities. After discussing these newly developing trends in Chinese society today, students often conclude that the Chinese government wants to revive traditional Chinese culture rooted in Confucianism in order to promote the “China Dream” and build a harmonious society. Moreover, Chinese leaders want to gain wisdom from indigenous Chinese culture to help solve contemporary problems, such as government corruption and the decline of moral integrity, while simultaneously opposing strong Western political and cultural influence. However, I make sure that students also know that Confucianism is but one historical tradition that influences China’s political leaders. For example, legalism, which dates back to even before the establishment of China’s first empire, the Qin in 221 BCE, is equally influential on the policies of Chinese leaders in many ways. Historically and in contemporary times, it can sometimes have ominous results for elements of the Chinese population. Instructors interested in making sure their students have an understanding of legalism are advised to access the Columbia University Asia for Educators website.4

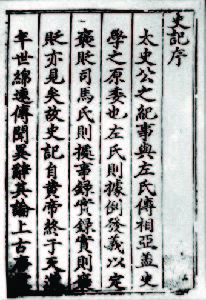

Record of the Grand Historian

Another important aspect of Chinese culture is Chinese history. The Shiji ( Record of the Grand Historian ), written from the late second century BCE to 86 BCE, is the foundational text of Chinese history and covers a broad historical spectrum from the mythical Yellow Emperor to Emperor Wu (156–87 BCE) of the Western Han dynasty (202 BCE–8). The class is introduced to the Shiji through a survey of its content, time span, the motivations behind its compilation, and major subdivisions within the work. For instance, students learn that the government did not sponsor the Shiji , and so did not dictate its contents. Rather, it was Sima Tan (ca. 165–110 BCE) who initially conducted the Shiji project, but his son, Sima Qian (ca. 145–86 BCE), actually compiled this monumental masterpiece in order to fulfill his father’s posthumous will. Moreover, Sima Qian fell out of favor with Emperor Wu because he defended Li Ling (134–74 BCE), a Han dynasty general, who defected to the Xiongnu nomadic tribes to the north of China. Sima Qian was ultimately punished for this by undergoing the humiliation of castration. In addition to these family and personal reasons for compiling the Shiji , Sima Qian also sought to establish a lineage of great historical figures who would otherwise have been forgotten in history. These factors strongly influenced what type of historical figures Sima Qian selected for the Shiji , the ways in which he narrated their accounts, and the conclusions he reached about them, as well as the lessons they represented for society as a whole. In general, Sima Qian emphasized the moral value and social impact of historical figures rather than their social or political status.

In my class, I select some biographies to discuss, among which is “The Biographies of the Assassin-Retainers.”5 Here I use the biography of Jing Ke (d. 227 BCE) as an example of how I lead class discussion, integrate the Shiji through film, and highlight its appeal in a contemporary context for students.6 The Jing Ke story took place toward the end of the Warring States Period (475–221 BCE), when the state of Qin had already annexed several rival states and had set its target on the state of Yan in the north. Prince Dan of Yan (d. 226 BCE) consulted his officials about this important issue, and a senior official named Tian Guang (d. 227 BCE) suggested that the prince should hire Jing Ke to assassinate the King of Qin (259–210 BCE). In order to gain an audience with the King of Qin, Jing Ke requested three items: the map of Dukang (part of Yan’s territory), a poisonous dagger, and the head of General Fan (d. 227 BCE), a traitor to the state of Qin. After obtaining these items, Jing Ke was granted an audience with the king in the Qin court. Jing Ke concealed the dagger inside the map scroll and unrolled it to its end. Suddenly, he grabbed the dagger from the scroll and attempted to kidnap the king as a hostage, but was unsuccessful. Eventually, the king and his courtiers killed Jing Ke. After reading this story, students must first summarize the text’s plot, as well as the major characters and their personalities. To engage critically in understanding the historical narrative, students discuss the following questions:

- Why is Jing Ke willing to accept Prince Dan of Yan’s order and carry out this assassination?

- How do you understand Jing Ke’s complex personality and psychological state? • Jing Ke was a failed assassin, yet he is glorified in Sima Qian’s record. Please consider Sima Qian’s own situation to explain why Jing Ke is immortalized and praised.

- In your opinion, is Jing Ke a hero? Why or why not? Students brainstorm different points and piece them together on the whiteboard to understand the history of the Warring States, the knight-errant culture, and the reception of the Jing Ke story. In addition, I explain the possible connection between Sima Qian’s choice of Jing Ke and his own life experiences.

To relate the Jing Ke story with contemporary Chinese society, I then show students parts of two film adaptations of the tale: Chen Kaige’s The Emperor and the Assassin and Zhang Yimou’s Hero , which are available through YouTube for a nominal fee. The former follows the standard historical narration fairly closely, while the latter changes the content substantially; however, students are still able to link the story with the film. In order to make this discussion more lively, students are required to complete a homework assignment on the following questions: How have the two films adapted the Jing Ke lore? What are their major changes? How do you evaluate these changes; are they successful or not? Through this exercise, students learn that the major plot of The Emperor and the Assassin is based on historical narration, with the exception of a new character— Lady Zhao—who is not found in any historical narrative. Students are to explain why this new role might have been created. Several factors shed light on this addition: since this is a three-hour-long, big-budget movie, the director may have been considering the box office results. More importantly, the purpose behind creating this role could have been to create a more complex and romantic plot. Even the director acknowledged in an interview that “Designing such a character like Lady Zhao cannot be said to have been done out of a lack of consideration for the plot. If I produced and shot a purely twoman story, it may not have had such a good effect.”7

Lady Zhao ultimately provides a link between the King of Qin and Jing Ke. When she is young, she admires Yingzheng’s (the King of Qin) courage and political ambition. However, when she later realizes that Yingzheng occupies the state of Zhao by slaughtering many innocent people, she turns to Jing Ke for help to stop such brutality. This additional character provides new possible interpretations of the motivations behind Jing Ke’s assassination attempt, which stems not only from his loyalty to Prince Dan, but also from his righteousness in desiring to remove a brutal ruler. This modern adaptation increases the significance of Jing Ke’s mission. In Zhang’s film Hero , students identify the major change of the assassin abandoning his mission to kill the king, where the assassin instead engages in a direct dialogue with the king in the Qin court. Through their conversation, the assassin comes to understand that the king wants to defeat all other kingdoms and unify China in order to bring peace to all people under heaven. Students then discuss their implications of this change. Often, students are critical towards this adaptation because it glorifies the King of Qin and conveys a problematic and debatable message to the audience that a ruler can adopt any method or make any sacrifice to achieve one’s goal, as long as one’s intention is good or meaningful.

These films demonstrate how contemporary approaches to narrating the story of Jing Ke continue to provide different interpretations of the story and its significance. The discussion about the Jing Ke lore has switched from focusing on the details of his assassination attempt to adapting his story to fit the contemporary needs of strengthening nationalism and Chinese identity. The promotion of a strong “nation-state” ideology by Chinese leaders has played an important role in shaping this reception. Contemporary society portrays him as a national hero, a strong man attempting to remove an evil and despotic ruler, and a knight-errant who embodies the traditional moral values of China in the face of Western influence during China’s rapid economic development, through which intellectuals can further probe China’s recent past and thus bring history to life.

Poems on Things and Objects

Along with Chinese philosophy and history, literature also plays an important role in Chinese culture, particularly poetry, which was the dominant literary subgenre throughout premodern Chinese history. This section provides a creative approach not only on how to teach classical Chinese poems, but also on integrating them within a type of traditional art—blow painting. By exploring this topic, students develop a solid understanding of Chinese poetry, learn the cultural meaning of the plum blossom, and express their own appreciation for Chinese poetry. 8

The plum blossom is famous, along with the orchid, bamboo, and chrysanthemum, as one of “The Four Gentlemen” in China. Furthermore, it is considered one of “The Three Friends in Winter,” together with pine trees and bamboo. However, plum trees are not common in the US, nor do they carry a significant cultural value, so the topic naturally stimulates student interest. Before we approach the topic of the plum blossom, my students have already studied other Chinese poems, so I briefly review some basic features of Chinese poetry, particularly the Chinese quatrain, which is often made up of four lines with five or seven characters in each line, and regulated verse, which is often made up of eight lines, and each line includes either five or seven characters. These two types of poetry were popular in the Tang dynasty (608–907), known as the golden age of Chinese poetry.9 Next, students gather information on the cultural meaning of the plum blossom and answer the following questions: How and when do Chinese people discuss plum blossoms? What does the plum blossom mean in Chinese society? What interesting facts do you know about the plum blossom? What can you learn from the symbolic meanings of plum blossoms? Students find appropriate information online and in the library about plum blossom culture and outline their primary ideas on the topic. Through class discussion, students also discover that the plum blossom has profound cultural connotations in China. The plum blossom symbolizes courage and strength because the fragrance of plum blossoms comes out of bitterness and coldness. The plum blossom also represents endurance and perseverance because plum blossoms flower in winter while most other plants do not survive. Furthermore, the plum blossom also embodies purity and lofty ideals, possibly because they bloom in winter, often covered with snow. To explore this motif, I incorporate several poems on plum blossoms in the lesson. Here are two examples from Shao Yong (1011–1077) and Wang Anshi (1021–1086):

A Leisure Walk by Shao Yong Once upon a time, we walk leisurely for two or three miles On the way, we see four or five misty villages Six or seven temples and Eight, nine or ten branches of plum blossom10

This poem is easy to understand but demonstrates the major characteristics of Song (960–1279) poetry, which focuses on the details of daily life. The poet’s focus gradually shifts from distant scenery to a closer look at his surroundings. At the beginning, the poet is far away, so he cannot see things clearly. When he moves closer, he sees the pavilions and houses. Looking even closer, he notices plum blossoms. The language in this poem is simple and clear without any descriptive words, but students still identify the poet’s cheerful mood and recognize that this is a pleasant experience. This is typical in Shao’s poems; as modern scholar Xiaoshan Yang states, “Shao Yong was always keen on distinguishing himself as a man of true joy and leisure from those who could only ‘steal leisure’ for a fleeting moment.”11 After discussing the content of the poem, I highlight the word “misty” in the first couplet, which, rather than denoting smoke caused by fire, instead is used to depict the remote villages. Because one cannot see the villages clearly in the distance, it seems like they are surrounded by mist. Another possibility is that many families had been cooking, hence smoke from their chimneys could be obscuring the poet’s vision and creating this phenomenon.

The second poem that I use on this topic is a five-character quatrain:

Plum Blossoms by Wang Anshi In the nook of a wall a few plum sprays, In solitude blossom on the bleak winter days, From the distance, I see they cannot be snow, For a stealthy breath of perfume hither flows.12

In this quatrain, the poet encourages his readers to make use of their senses such as sight and smell. This poem does not focus on the appearance of the plum blossoms, but rather on their character and spirit. Students often note that these plum blossoms appear in the corner of a wall during winter, which is unlikely to draw the attention of many people, revealing the unique character of the poet. In addition, without much nutrients, they still manage to blossom, demonstrating their hardiness. Furthermore, the last couplet forms a reverse causality: the third line tells the reader the result of noticing that the things in the distance are not snow; the fourth line informs the readers why the poet believes this is so: they are fragrant and cannot be snow. Thus, without describing the color of the plum blossoms themselves, the reader knows that they are either a white variety or are covered by snow, so they seem like snow when one looks at them far away. In terms of language, this poem does not employ overly ornate syntax. Yet through this simple and tranquil language, the poet conveys the spirit of plum blossoms: strong endurance and vibrant life. They are not afraid of cold weather, an analogy for people who do not fear power or authority. This allows the class to understand that the subtext of Chinese poetry often has political implications. Based on students’ discussions, I further explain a possible hidden reading: this poem may also allude to the poet’s own frustrated situation, when his political reform efforts faced resistance and gradually lost the Emperor Shenzong’s (1048–1085) support. However, through such adversity, like the plum blossom in winter, he was determined not to yield.

To make this topic even more lively, I integrate blow painting into the section on plum blossom poetry. The instructor should finish a complete blow painting before class so that students can see what the final product looks like. A simple blow painting requires some basic items, such as paper plates, calligraphy brushes, ink, red paint, and water. Ideally, one should use xuan paper made of different fibers, such as blue sandalwood, rice straw, and mulberry, which is specially designed for painting and calligraphy. However, it is difficult to obtain in the US, so I use paper plates instead. The procedure is simple: first, one puts drops of ink in the middle of the paper plate, blowing the drops slowly and patiently in different directions as the first several blows shape the main stem of the tree. Then, blow a little harder, so the stem becomes thicker. Once the main stem is shaped, one can blow the ink quickly in various directions, which become different branches. One may use a straw to do the blowing to expedite the whole process. After the basic painting is completed, one may use a brush to dip into the red ink and put the petals or flowers around the branches and twigs. This combination of poetry appreciation and blow painting demonstration enables students to understand Chinese culture more vividly and concretely.

Many colleges and universities have some type of traditional Chinese culture courses, whether they be premodern Chinese literature, history, philosophy, or other China-related courses. This article offers personal insight and unique methods of diversifying approaches to teaching Chinese culture effectively. It investigates avenues for bringing traditional Chinese culture to life by demonstrating how to integrate multimedia (such as recent news and films), as well as fine arts (such as blow painting of plum blossoms) into a culture class. These examples and approaches, including discussion questions, are used to explore the current appeal of traditional Chinese culture, which continues to shape Chinese identity and character. In addition, these practices include useful materials for designing extracurricular activities in Chinese clubs, film presentations, or guest lectures. A combination of Chinese culture, multimedia, and hands-on experience in the classroom has proven to increase students’ interest and motivation, as well as broaden their horizons with regards to Chinese civilization and society.

Acknowledgements :

This article is made possible by Valparaiso University’s Research Expense Grant and the East Asian Studies Library Travel Grant of the University of Chicago. I also appreciate useful comments from two anonymous reviewers, EAA Editor Dr. Lucien Ellington, Dr. David Chai, Amanda S. Robb, and James Churchill.

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

NOTES 1.”What Did Confucius Say?,” Asia for Educators , accessed February 20, 2018, https://tinyurl.com/ycyosqn9.

3. Jeremy Page, “Why China Is Turning Back to Confucius,” Wall Street Journal , September 20, 2015 https://tinyurl.com/ya6fhy37.

4. See “Introduction to Legalism” on the Asia for Educators website at https://tinyurl.com/ya6becmm.

5. For the English translation of this chapter, see Burton Watson, Record of the Grand Historian: Han Dynasty II (rev. ed.) (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993) and William H. Nienhauser Jr., The Grand Scribe’s Records: The Memoirs of Pre-Han China (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994).

6. For a detailed discussion on the reception of the Jing Ke story, see Yuri Pine, “A Hero Terrorist: Adoration of Jing Ke Revisited,” Asia Major 21, no. 2 (2008): 1–34.

7. Chen Kaige, Fenghuang Wang, “Chen Kaige jiu ‘Jing Ke ci Qinwang’ da jizhe wen,” accessed May 24, 2016, https://tinyurl.com/y726n7ew.

8. A few good scholarly books on this topic are Maggie Bickford, Ink Plum: The Making of a Chinese Scholar-Painting Genre (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996) and Hans H. Frankel, Flowering Plum and the Palace Lady: Interpretations of Chinese Poetry (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1978).

9. For more information on the Chinese quatrain and regulated verse, see Zong-Qi Cai, ed., How to Read Chinese Poetry: A Guided Anthology (New York: Columbia University Press, 2008), 161–225.

10. The English translation of this poem is adapted from Learning Mandarin Chinese , https://tinyurl.com/ya9jud46l, accessed February 18, 2018. The flowers appearing at the end of this poem may not necessarily refer to plum blossoms, but for the purpose of teaching this topic, instructors may choose to interpret it as plum blossoms.

11. Xiaoshan Yang, Metamorphosis of the Private Sphere: Gardens and Objects in Tang-Song Poetry (Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center, 2003), 216. 12. The English translation of this poem follows: Cultural China , accessed February 18, 2018, https://tinyurl.com/ya282e6h.

- Latest News

- Join or Renew

- Education About Asia

- Education About Asia Articles

- Asia Shorts Book Series

- Asia Past & Present

- Key Issues in Asian Studies

- Journal of Asian Studies

- The Bibliography of Asian Studies

- AAS-Gale Fellowship

- Council Grants

- Book Prizes

- Graduate Student Paper Prizes

- Distinguished Contributions to Asian Studies Award

- First Book Subvention Program

- External Grants & Fellowships

- AAS Career Center

- Asian Studies Programs & Centers

- Study Abroad Programs

- Language Database

- Conferences & Events

- #AsiaNow Blog

- Immersion Program

- Learn Chinese Online

- Study Abroad in China

- Custom Travel Programs

- Teach in China

- What is CLI?

- Testimonials

- The CLI Center

- Photo Gallery

- 简体中文

- 한국어

- Español

Journey into the World of Chinese Tea

Learn Chinese in China or on Zoom and gain fluency in Chinese!

Join CLI and learn Chinese with your personal team of Mandarin teachers online or in person at the CLI Center in Guilin , China.

China is synonymous with tea, and tea with China. In fact, the history of tea in China is almost as long as the history of China itself.

Despite the recent rise of coffee, Chinese tea culture continues to enjoy great popularity. Read on to learn about the past, present and future of tea in China .

Table of Contents

Shennong: The Mythical Father of Chinese Medicine

Early archeological and historical evidence, the classic of tea by lu yu, tea during the ming and qing dynasties, the east india company and robert fortune, we really mean tea, camellia sinensis tea, types of chinese teas, honorable mentions, we must not forget herbal "teas", last but not least, nǎichá, top 5 recommended chinese teas, chinese tea ceremonies gain in popularity, how to conduct a chinese tea ceremony, everything tea, how much coffee do people drink in china, the chinese tea industry marches on, chinese vocabulary related to chinese tea culture.

Learn Chinese with CLI

The History of Tea in China

The history of Chinese tea (茶 chá ) begins with Shennong (神农 S hénnóng ), a mythical personage said to be the father of Chinese agriculture and Traditional Chinese Medicine .

Legend has it that Shennong accidentally discovered tea as he was boiling water to drink while sitting under a Camellia sinensis tree. Some leaves from the tree fell into the water, infusing it with a refreshing aroma. Shennong took a sip, found it enjoyable, and thus, tea was born.

Shennong is considered the father of Chinese agriculture.

Chinese mythology aside, archeological evidence has been found indicating that tea was used as a medicine by the elite as early as the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE).

Tea didn’t achieve widespread popularity as an everyday beverage in China until the Tang dynasty (618-907 CE), however. Chinese Buddhist monks were some of the first to develop the habit of drinking tea. Its caffeine content helped them concentrate during long hours of prayer and meditation.

Much of the information we have about early Chinese tea culture comes from The Classic of Tea (茶经 C hájīng ), written around 760 CE by Lu Yu (陆羽 L ù Yǔ ), an orphan who grew up cultivating and drinking tea in a Buddhist monastery.

The Classic of Tea describes early Tang dynasty tea culture and explains how to grow and prepare tea.

In Lu Yu’s day, tea leaves were compressed into tea bricks , which were sometimes used as currency . When it was time to drink the tea, it was ground into a powder and mixed with water using a whisk to create a frothy beverage.

Although this type of powdered tea is no longer common in China, it was brought from China to Japan during the Tang dynasty and lives on today in Japanese matcha .

During the Ming dynasty (1368–1644 CE), tea bricks were replaced with loose leaf tea by imperial decree. This change was meant to make life easier for farmers since the traditional method of creating tea bricks was quite labor intensive.

Loose leaf tea is still the most common form of tea found in China today.

Tea was introduced in Britain in the mid-1600’s and British demand for tea soon created a trade imbalance with China. To correct it, Britain began exporting opium to China.

After China tried to ban opium, Britain launched the mid-19th century Opium Wars to force the trade to continue.

Although the wars achieved their stated goal, British merchants began to worry about the viability of continuing to rely on tea from the Chinese market. Soon, the East India Company sent Robert Fortune , a Scottish botanist and adventurer, to steal the secrets of tea-making from China.

Fortune’s stolen information, plants and seeds were then used to start large-scale tea production in India.

Indian tea production quickly outstripped that of China, and China lost its long-standing monopoly on the international tea trade.

The Chinese tea industry went into decline, and China has only recently regained its status as the world’s leading tea exporter.

Scottish botanist Robert Fortune in China, where he covertly collected tea plants and seeds for the East India Company, revolutionizing the global tea industry.

Popular Types of Tea in China

Today, most Chinese tea is loose leaf tea that’s steeped in boiling water, either in a teapot (茶壶 cháhú ) or directly in a thermos or glass, depending on the type of tea being consumed.

Drinking tea made from tea bags is uncommon in China.

“Tea” is used as a catch-all term for many different herbal brews in the West. In the strictest sense, however, the word “tea” only applies to beverages made from the leaves of the Camellia sinensis plant.

Contrary to popular belief, the differences in taste and color seen in different types of Chinese tea are not due to the use of different kinds of tea leaves. Rather, they are due to differences in the production and manufacturing process.

The type of tea produced is determined by the level of oxidation the tea leaves are allowed to undergo before the process is stopped by heating the leaves. In China, tea merchants usually refer to this oxidation process as fermentation (发酵 fājiào ).

Chinese teas are classified according to their level of fermentation. The more fermented the tea, the stronger its taste. White teas (白茶 báichá) are essentially unfermented (不发酵 bù fājiào).

They are followed by lightly fermented (微发酵 wēi fājiào) green teas (绿茶 lǜchá), half fermented (半发酵 bàn fājiào) oolong teas (乌龙茶 wūlóng chá), and fully fermented (全发酵 quán fājiào) black teas (红茶 hóngchá).

Pu’er (also called pu-erh) teas (普洱茶 pǔ'ěrchá), which are generally quite dark and strong, are said to be post-fermented (后发酵 hòu fājiào).

Certain regions of China are known for producing and consuming special types of tea. For example, Wuyi Mountain, in Fujian Province, is particularly famous for production and consumption of fine oolong teas such as dahongpao (大红袍 dàhóngpáo ).

Green teas such as biluochun (碧螺春 bìluóchūn ), grown in Jiangsu Province, are popular in the region around Shanghai.

Biluochun tea

Other beverages referred to as “tea” also exist in China, although some of them don’t actually contain any Camellia sinensis leaves.

One popular tea is jasmine tea (茉莉花茶 mòlìhuāchá ), made from a mixture of green tea and jasmine flowers.

Barley tea (大麦茶 dàmàichá ), made from roasted barley grains, doesn’t actually contain any tea leaves at all.

Jasmine tea

Other types of “tea” that enjoy immense popularity among the younger generations are milk tea (奶茶 nǎichá ) and bubble tea (珍珠奶茶 zhēnzhū nǎichá ).

These sugary drinks, which don’t contain much (if any) actual tea, come in a variety of different flavors.

CLI is in the business of China, and in China business means drinking tea. After over 12 years working day in and day out on behalf of our students and community (which means staying well caffeinated!), we've come know tea well.

Here are our top 5 recommended Chinese teas:

Buy from Amazon

Modern Chinese Tea Culture

Tea culture in China is most intact in the south, where the bulk of China’s tea is produced.

Tea can be consumed at home or in teahouses (茶馆 cháguǎn ), many of which offer private rooms for drinking tea with friends or business partners. Although tea is consumed by people from every sector of society, most tea connoisseurs tend to be middle-aged business people, intellectuals or artists.

Much of modern Chinese tea culture revolves around the gongfu tea ceremony (功夫茶 or gōngfūchá ). Thought to have originated in Fujian or Guangdong Province, it usually features black, oolong or pu’er tea.

At its most basic, the ceremony makes use of tiny tea cups (茶杯 chábēi ), a tea-brewing vessel such as a gaiwan (盖碗 gàiwǎn ) or an Yixing purple clay teapot (紫砂壶 zǐshāhú ), a tea strainer, a tea pitcher and a tea table or tray. Other utensils such as tea tongs are optional.

The more complicated the ceremony, the more utensils are likely to be involved. Tea tables are often quite large and can be decorated with whimsical tea pets (茶宠 cháchǒng ).

Normally, tea ceremonies are run by a host who begins by steeping loose leaf tea in water in a gaiwan or teapot, and then pouring it through a tea strainer into a tea pitcher to filter out bits of tea leaf.

Next, the host pours tea from the pitcher onto teacups. Instead of serving this first batch of tea to guests, the host generally pours it out onto the tea table, allowing it to drain into a bucket underneath.

This is done to wash the tea cups and also because tea from the first pour is thought to be too strong to drink. This process is then repeated, except that the tea is served to those present instead of being discarded.

After being served, guests should either thank the host verbally or express thanks by tapping their bent index and middle fingers on the tea table. This custom is most common in southern China and is said to have originated during the Qing dynasty (1636–1912 CE), when the Qianlong Emperor , who was traveling in disguise, poured tea for a servant.

The servant wanted to show his gratitude by kneeling, but couldn’t do so for fear of revealing the emperor’s identity. Therefore, he tapped the table with two bent fingers instead.

For a full transcript of the above video that includes Chinese characters , pinyin , and English translations, click here .

It is possible to spend a great deal of money collecting expensive tea leaves and fine tea accessories, especially Yixing teapots .

In some affluent circles, engagement with tea culture is used as a way to “ flaunt wealth and invest savings ,” a bit like wine culture in the United States. Certain wealthy individuals use their knowledge of tea culture to impress friends and gain prestige.

It’s also not uncommon for expensive teas to be given as gifts on important occasions.

That said, not everyone you encounter in China is going to be a tea connoisseur. Many won’t even be familiar with the gongfu tea ceremony.

Some families don’t have the habit of drinking tea, and some people simply drink it without fanfare in a thermos that they carry with them throughout the day.

The Rise of Coffee

China has been a nation of tea drinkers for a long time, and coffee (咖啡 kā fēi ) was rare in China until recently. Over the past 20 years, coffee’s popularity has steadily increased, especially among urban millennials.

Although per capita Chinese coffee consumption is still only 5 cups per year compared to 400 cups in the United States, the demand for coffee in China has grown exponentially since the first Starbucks opened in Beijing in 1999.

Coffee shops (咖啡馆 kāfēiguǎn ) are now ubiquitous in China’s first, second, and even third-tier cities.

Coffee is especially popular with students and young white-collar workers, who associate it with the aspirational Western lifestyle that comes with newfound economic mobility.

The prices at Starbucks in China are quite high compared to those in the U.S., but this only helps to add to its allure and cements Starbucks coffee as a status symbol for the new middle class.

The Future of Tea

For now, tea drinking is firmly entrenched in Chinese culture. Coffee’s increasing popularity poses a challenge to the Chinese tea industry, however.

Today, traditional teahouses are nowhere near as popular with members of the younger generation as coffee shops are. This is perhaps related to the fact that traditional Chinese tea suffers from a branding problem.

While large coffee chains like Starbucks have sophisticated brand images that attract young consumers, no traditional Chinese tea brands with such widespread appeal have emerged.

Recently, some traditional tea companies have responded to changes in the market by opening trendy cafes or offering new products designed to appeal to more modern tastes such as fruit-flavored teas, tea bags, and instant tea. Such changes may be necessary if China’s tea industry wants to compete with coffee in the long-run.

Considering its strong historical record of successfully adapting to the changes brought about by wars, intellectual property theft and imperial decrees, the Chinese tea industry seems likely to overcome its current challenges and continue to exist for many years to come.

| Hànzì | Pīnyīn | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| 茶 | chá | tea |

| 喝茶 | hē chá | drink tea |

| 神农 | Shénnóng | "The Divine Farmer," a mythical ruler and deity credited with inventing agriculture |

| 茶经 | Chájīng | The Classic of Tea by Lu Yu, the first ever monograph on tea |

| 发酵 | fājiào | ferment (used to refer to oxidation process in tea production) |

| 白茶 | báichá | white tea |

| 绿茶 | lǜchá | green tea |

| 普洱茶 | pǔ'ěrchá | pu'er or pu-erh tea |

| 茉莉花茶 | mòlìhuāchá | jasmine tea |

| 大麦茶 | dàmàichá | barley tea |

| 奶茶 | nǎichá | milk tea |

| 珍珠奶茶 | zhēnzhū nǎichá | bubble tea |

| 茶馆 | cháguǎn | tea house |

| 功夫茶 | gōngfūchá | gongfu tea ceremony |

| 盖碗 | gàiwǎn | lidded, handle-less bowl used to brew tea |

| 紫砂壶 | zǐshāhú | purple clay teapot |

| 茶壶 | cháhú | teapot |

| 茶宠 | cháchǒng | tea pet |

| 咖啡 | kāfēi | coffee |

| 咖啡馆 | kāfēiguǎn | coffee house |

Anne Meredith holds an MA in International Politics and Chinese Studies from the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS). As part of the graduation requirements for the program, Anne wrote and defended a 70-page Master's thesis entirely in 汉字 (hànzì; Chinese characters). Anne lives in Shanghai, China and is fluent in Chinese.

Free 30-minute Trial Lesson

Continue exploring.

- Chinese Culture

Copyright 2024 | Terms & Conditions | FAQ | Learn Chinese in China

Chinese Traditional Festivals and Culture Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

The Chinese culture is one of the most celebrated cultures over the world. Owing to this culture, there are many festivals associated with it. Through these festivals, the Chinese culture has become overwhelmingly popular in many parts of the world.

The festivals fall in different times of the year and are celebrated in differing styles. All these festivals may be classified under four categories (Gibney, p. 109). This paper will focus on the three Chinese traditional festivals.

These are the Spring Festival, the Mid-Autumn Festival and the Dragon Boat festival. This paper will briefly describe the three festivals and their importance to the Chinese people.

The paper will also explain what the festivals tell the audience about Chinese traditional culture, values and the similarities among these festivals’ values. Chinese have various festivals and Cultures which have different values and similarities. The festivals tell more about the Chinese cultures and values.

The Spring Festival

Of all the Chinese festivals, the Spring Festival has the greatest value to the Chinese people with its value equated to the value of the Westerners attachment to Christmas. It is a time of the year designated for merrymaking when family members come together to celebrate the occasion.

This period is characterized by congestion and overcrowding in all the transport networks. Millions of Chinese fill the airports, bus stations and rail stations in a rush to return home (Kalman, p. 20).

The Spring Festival is celebrated for a period of three days every year though its entire duration is a bit longer. The festival falls on the first day of the first lunar month but starts unceremoniously in the early days of the twelfth lunar month and extends to the mid of the first lunar month of the following year.

During this entire period, the eve of the Spring festival and the following three days have the greatest importance to the Chinese people (Kalman, p. 20).

The history of this festival dates back to the 12th century. The custom has survived through the centuries though the meaning has slightly changed. Today, the festival does not necessarily involve offering sacrifices to gods or ancestors, but simply marks the end of a year and the beginning of another.

The government attaches a lot of importance to the festival and even stipulates that people take the first seven days of the New Year to celebrate. A series of events carried out by the Chinese people mark the Spring Festival (Kalman, p. 21).

The occasion starts on the eighth day of the last lunar month. On this day, families make laba porridge which is made of beans, rice, lotus seeds, millet, jujube berries, longan and gingko. Following this, preparing delicious meals is held on the twenty third day of the same month.

Initially, the meaning of this day was to offer sacrifice to the Chinese kitchen god; however, today, people prepare the meals to enjoy themselves. The day is called the ’Preliminary Eve’ after which people commence the actual preparations for welcoming the New Year. During this period, people go into a shopping spree buying all they will require during the New Year celebrations (Kalman, p. 21).

To mark a new beginning associated with the up coming New Year, all the people carry out a thorough cleaning of their clothes, utensils, houses and compounds. This is followed by colorful decorations to create an atmosphere of joy and festive mood.

At this time, the Chinese mastery in calligraphy is brought to the fore. All houses are decorated with various patterns depending on the tastes of the owners; however, the most common colors are red and black. The most popular decorations involve pasting of the door panels with couplets which have red and black collage patterns.

The Chinese associate different colors and patterns with personal wishes, such as good luck and success in the New Year. Those who still harbor strong traditional attachments decorate their houses with images of the gods of wealth whom they believe will bring them abundant wealth in the New Year (Kalman, p. 22).

The most remarkable symbol that is almost consciously mandatory in the New Year celebrations is the character fu which stands for the happiness and blessings. Other characters and patterns with various meaning associated with the festivities are also commonplace around this period. For example, red lanterns erected on opposite sides of the doors and other brightly decorated images have special meanings of the new beginning or renewed hope to the Chinese populace (Kalman, p. 22).

Another popular custom is the setting of fire crackers and fireworks. The special meaning of this practice is biding farewell to the previous year and welcoming the New Year. The custom of using the fireworks exists in China for a long and is an integral part in many other occasions, such as sports events and wedding ceremonies.