Your web browser is outdated and may be insecure

The RCN recommends using an updated browser such as Microsoft Edge or Google Chrome

Critical Appraisal

Use this guide to find information resources about critical appraisal including checklists, books and journal articles.

Key Resources

- This online resource explains the sections commonly used in research articles. Understanding how research articles are organised can make reading and evaluating them easier View page

- Critical appraisal checklists

- Worksheets for appraising systematic reviews, diagnostics, prognostics and RCTs. View page

- A free online resource for both healthcare staff and patients; four modules of 30–45 minutes provide an introduction to evidence based medicine, clinical trials and Cochrane Evidence. View page

- This tool will guide you through a series of questions to help you to review and interpret a published health research paper. View page

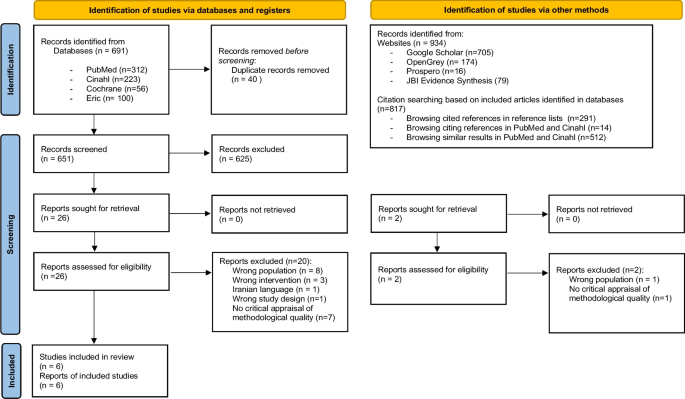

- The PRISMA flow diagram depicts the flow of information through the different phases of a literature review. It maps out the number of records identified, included and excluded, and the reasons for exclusions. View page

- A useful resource for methods and evidence in applied social science. View page

- A comprehensive database of reporting guidelines. Covers all the main study types. View page

- A tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. View page

- Borrow from RCN Library services

- Chapter 5 covers critical appraisal of the literature. View this eBook

- Chapter 6 covers assessing the evidence base. Borrow from RCN Library services

- Section 1 covers an introduction to critical appraisal. Section 3 covers appraising difference types of papers including qualitative papers and observational studies. View this eBook

- Chapter 6 covers critically appraising the literature. Borrow from RCN Library services

- View this eBook

- Chapter 8 covers critical appraisal of the evidence. View this eBook

- Chapter 18 covers critical appraisal of nursing studies. View this eBook

- Borrow from RCN Library Services

Book subject search

- Critical appraisal

Journal articles

- View article

Shea BJ and others (2017) AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions or both, British Medical Journal, 358.

- An outline of AMSTAR 2 and its use for as a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews. View article (open access)

- View articles

Editor of this guide

RCN Library and Archive Service

Upcoming events relating to this subject guide

Know How to Search CINAHL

Learn about using the CINAHL database for literature searches at this event for RCN members.

Library Search ... in 30 minutes

Learn how RCN members can quickly and easily search for articles, books and more using our fantastic and easy to use Library Search tool.

Know How to Reference Accurately and Avoid Plagiarism

Learn how to use the Harvard refencing style and why referencing is important at this event for RCN members.

Easy referencing ... in 30 minutes

Learn how to generate quick references and citations using free, easy to use, online tools.

Page last updated - 08/02/2024

Your Spaces

- RCNi Profile

- RCN Starting Out

- Steward Portal

- Careers at the RCN

- RCN Foundation

- RCN Library

Work & Venue

- RCNi Nursing Jobs

- Work for the RCN

- RCN Working with us

Further Info

- Manage Cookie Preferences

- Modern slavery statement

- Accessibility

- Press office

Connect with us:

© 2024 Royal College of Nursing

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

- MEDICAL ASSISSTANT

- Abdominal Key

- Anesthesia Key

- Basicmedical Key

- Otolaryngology & Ophthalmology

- Musculoskeletal Key

- Obstetric, Gynecology and Pediatric

- Oncology & Hematology

- Plastic Surgery & Dermatology

- Clinical Dentistry

- Radiology Key

- Thoracic Key

- Veterinary Medicine

- Gold Membership

Critical Appraisal of Quantitative and Qualitative Research for Nursing Practice

Chapter 12 Critical Appraisal of Quantitative and Qualitative Research for Nursing Practice Chapter Overview When Are Critical Appraisals of Studies Implemented in Nursing? Students’ Critical Appraisal of Studies Critical Appraisal of Studies by Practicing Nurses, Nurse Educators, and Researchers Critical Appraisal of Research Following Presentation and Publication Critical Appraisal of Research for Presentation and Publication Critical Appraisal of Research Proposals What Are the Key Principles for Conducting Intellectual Critical Appraisals of Quantitative and Qualitative Studies? Understanding the Quantitative Research Critical Appraisal Process Step 1: Identifying the Steps of the Research Process in Studies Step 2: Determining the Strengths and Weaknesses in Studies Step 3: Evaluating the Credibility and Meaning of Study Findings Example of a Critical Appraisal of a Quantitative Study Understanding the Qualitative Research Critical Appraisal Process Step 1: Identifying the Components of the Qualitative Research Process in Studies Step 2: Determining the Strengths and Weaknesses in Studies Step 3: Evaluating the Trustworthiness and Meaning of Study Finding Example of a Critical Appraisal of a Qualitative Study Key Concepts References Learning Outcomes After completing this chapter, you should be able to: 1. Describe when intellectual critical appraisals of studies are conducted in nursing. 2. Implement key principles in critically appraising quantitative and qualitative studies. 3. Describe the three steps for critically appraising a study: (1) identifying the steps of the research process in the study; (2) determining study strengths and weaknesses; and (3) evaluating the credibility and meaning of the study findings. 4. Conduct a critical appraisal of a quantitative research report. 5. Conduct a critical appraisal of a qualitative research report. Key Terms Confirmability, p. 392 Credibility, p. 392 Critical appraisal, p. 362 Critical appraisal of qualitative studies, p. 389 Critical appraisal of quantitative studies, p. 362 Dependability, p. 392 Determining strengths and weaknesses in the studies, p. 370 Evaluating the credibility and meaning of study findings, p. 374 Identifying the steps of the research process in studies, p. 366 Intellectual critical appraisal of a study, p. 365 Qualitative research critical appraisal process, p. 389 Quantitative research critical appraisal process, p. 366 Referred journals, p. 364 Transferable, p. 392 Trustworthiness, p. 392 The nursing profession continually strives for evidence-based practice (EBP), which includes critically appraising studies, synthesizing the findings, applying the scientific evidence in practice, and determining the practice outcomes ( Brown, 2014 ; Doran, 2011 ; Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2011 ). Critically appraising studies is an essential step toward basing your practice on current research findings. The term critical appraisal or critique is an examination of the quality of a study to determine the credibility and meaning of the findings for nursing. Critique is often associated with criticize, a word that is frequently viewed as negative. In the arts and sciences, however, critique is associated with critical thinking and evaluation—tasks requiring carefully developed intellectual skills. This type of critique is referred to as an intellectual critical appraisal. An intellectual critical appraisal is directed at the element that is created, such as a study, rather than at the creator, and involves the evaluation of the quality of that element. For example, it is possible to conduct an intellectual critical appraisal of a work of art, an essay, and a study. The idea of the intellectual critical appraisal of research was introduced earlier in this text and has been woven throughout the chapters. As each step of the research process was introduced, guidelines were provided to direct the critical appraisal of that aspect of a research report. This chapter summarizes and builds on previous critical appraisal content and provides direction for conducting critical appraisals of quantitative and qualitative studies. The background provided by this chapter serves as a foundation for the critical appraisal of research syntheses (systematic reviews, meta-analyses, meta-syntheses, and mixed-methods systematic reviews) presented in Chapter 13. This chapter discusses the implementation of critical appraisals in nursing by students, practicing nurses, nurse educators, and researchers. The key principles for implementing intellectual critical appraisals of quantitative and qualitative studies are described to provide an overview of the critical appraisal process. The steps for critical appraisal of quantitative studies , focused on rigor, design validity, quality, and meaning of findings, are detailed, and an example of a critical appraisal of a published quantitative study is provided. The chapter concludes with the critical appraisal process for qualitative studies and an example of a critical appraisal of a qualitative study. When are Critical Appraisals of Studies Implemented in Nursing? In general, studies are critically appraised to broaden understanding, summarize knowledge for practice, and provide a knowledge base for future research. Studies are critically appraised for class projects and to determine the research evidence ready for use in practice. In addition, critical appraisals are often conducted after verbal presentations of studies, after a published research report, for selection of abstracts when studies are presented at conferences, for article selection for publication, and for evaluation of research proposals for implementation or funding. Therefore nursing students, practicing nurses, nurse educators, and nurse researchers are all involved in the critical appraisal of studies. Students’ Critical Appraisal of Studies One aspect of learning the research process is being able to read and comprehend published research reports. However, conducting a critical appraisal of a study is not a basic skill, and the content presented in previous chapters is essential for implementing this process. Students usually acquire basic knowledge of the research process and critical appraisal process in their baccalaureate program. More advanced analysis skills are often taught at the master’s and doctoral levels. Performing a critical appraisal of a study involves the following three steps, which are detailed in this chapter: (1) identifying the steps or elements of the study; (2) determining the study strengths and limitations; and (3) evaluating the credibility and meaning of the study findings. By critically appraising studies, you will expand your analysis skills, strengthen your knowledge base, and increase your use of research evidence in practice. Striving for EBP is one of the competencies identified for associate degree and baccalaureate degree (prelicensure) students by the Quality and Safety Education for Nurses ( QSEN, 2013 ) project, and EBP requires critical appraisal and synthesis of study findings for practice ( Sherwood & Barnsteiner, 2012 ). Therefore critical appraisal of studies is an important part of your education and your practice as a nurse. Critical Appraisal of Studies by Practicing Nurses, Nurse Educators, and Researchers Practicing nurses need to appraise studies critically so that their practice is based on current research evidence and not on tradition or trial and error ( Brown, 2014 ; Craig & Smyth, 2012 ). Nursing actions need to be updated in response to current evidence that is generated through research and theory development. It is important for practicing nurses to design methods for remaining current in their practice areas. Reading research journals and posting or e-mailing current studies at work can increase nurses’ awareness of study findings but are not sufficient for critical appraisal to occur. Nurses need to question the quality of the studies, credibility of the findings, and meaning of the findings for practice. For example, nurses might form a research journal club in which studies are presented and critically appraised by members of the group ( Gloeckner & Robinson, 2010 ). Skills in critical appraisal of research enable practicing nurses to synthesize the most credible, significant, and appropriate evidence for use in their practice. EBP is essential in agencies that are seeking or maintaining Magnet status. The Magnet Recognition Program was developed by the American Nurses Credentialing Center ( ANCC, 2013 ) to “recognize healthcare organizations for quality patient care, nursing excellence, and innovations in professional nursing,” which requires implementing the most current research evidence in practice (see http://www.nursecredentialing.org/Magnet/ProgramOverview.aspx ). Your faculty members critically appraise research to expand their clinical knowledge base and to develop and refine the nursing educational process. The careful analysis of current nursing studies provides a basis for updating curriculum content for use in clinical and classroom settings. Faculty serve as role models for their students by examining new studies, evaluating the information obtained from research, and indicating which research evidence to use in practice. For example, nursing instructors might critically appraise and present the most current evidence about caring for people with hypertension in class and role-model the management of patients with hypertension in practice. Nurse researchers critically appraise previous research to plan and implement their next study. Many researchers have a program of research in a selected area, and they update their knowledge base by critically appraising new studies in this area. For example, selected nurse researchers have a program of research to identify effective interventions for assisting patients in managing their hypertension and reducing their cardiovascular risk factors. Critical Appraisal of Research Following Presentation and Publication When nurses attend research conferences, they note that critical appraisals and questions often follow presentations of studies. These critical appraisals assist researchers in identifying the strengths and weaknesses of their studies and generating ideas for further research. Participants listening to study critiques might gain insight into the conduct of research. In addition, experiencing the critical appraisal process can increase the conference participants’ ability to evaluate studies and judge the usefulness of the research evidence for practice. Critical appraisals have been published following some studies in research journals. For example, the research journals Scholarly Inquiry for Nursing Practice: An International Journal and Western Journal of Nursing Research include commentaries after the research articles. In these commentaries, other researchers critically appraise the authors’ studies, and the authors have a chance to respond to these comments. Published research critical appraisals often increase the reader’s understanding of the study and the quality of the study findings ( American Psychological Association [APA], 2010 ). A more informal critical appraisal of a published study might appear in a letter to the editor. Readers have the opportunity to comment on the strengths and weaknesses of published studies by writing to the journal editor. Critical Appraisal of Research for Presentation and Publication Planners of professional conferences often invite researchers to submit an abstract of a study they are conducting or have completed for potential presentation at the conference. The amount of information available is usually limited, because many abstracts are restricted to 100 to 250 words. Nevertheless, reviewers must select the best-designed studies with the most significant outcomes for presentation at nursing conferences. This process requires an experienced researcher who needs few cues to determine the quality of a study. Critical appraisal of an abstract usually addresses the following criteria: (1) appropriateness of the study for the conference program; (2) completeness of the research project; (3) overall quality of the study problem, purpose, methodology, and results; (4) contribution of the study to nursing’s knowledge base; (5) contribution of the study to nursing theory; (6) originality of the work (not previously published); (7) implication of the study findings for practice; and (8) clarity, conciseness, and completeness of the abstract ( APA, 2010 ; Grove, Burns, & Gray, 2013 ). Some nurse researchers serve as peer reviewers for professional journals to evaluate the quality of research papers submitted for publication. The role of these scientists is to ensure that the studies accepted for publication are well designed and contribute to the body of knowledge. Journals that have their articles critically appraised by expert peer reviews are called peer-reviewed journals or referred journals ( Pyrczak, 2008 ). The reviewers’ comments or summaries of their comments are sent to the researchers to direct their revision of the manuscripts for publication. Referred journals usually have studies and articles of higher quality and provide excellent studies for your review for practice. Critical Appraisal of Research Proposals Critical appraisals of research proposals are conducted to approve student research projects, permit data collection in an institution, and select the best studies for funding by local, state, national, and international organizations and agencies. You might be involved in a proposal review if you are participating in collecting data as part of a class project or studies done in your clinical agency. More details on proposal development and approval can be found in Grove et al. (2013, Chapter 28) . Research proposals are reviewed for funding from selected government agencies and corporations. Private corporations develop their own format for reviewing and funding research projects ( Grove et al., 2013 ). The peer review process in federal funding agencies involves an extremely complex critical appraisal. Nurses are involved in this level of research review through national funding agencies, such as the National Institute of Nursing Research ( NINR, 2013 ) and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality ( AHRQ, 2013 ). What are the Key Principles for Conducting Intellectual Critical Appraisals of Quantitative and Qualitative Studies? An intellectual critical appraisal of a study involves a careful and complete examination of a study to judge its strengths, weaknesses, credibility, meaning, and significance for practice. A high-quality study focuses on a significant problem, demonstrates sound methodology, produces credible findings, indicates implications for practice, and provides a basis for additional studies ( Grove et al., 2013 ; Hoare & Hoe, 2013 ; Hoe & Hoare, 2012 ). Ultimately, the findings from several quality studies can be synthesized to provide empirical evidence for use in practice ( O’Mathuna, Fineout-Overholt, & Johnston, 2011 ). The major focus of this chapter is conducting critical appraisals of quantitative and qualitative studies. These critical appraisals involve implementing some key principles or guidelines, outlined in Box 12-1 . These guidelines stress the importance of examining the expertise of the authors, reviewing the entire study, addressing the study’s strengths and weaknesses, and evaluating the credibility of the study findings ( Fawcett & Garity, 2009 ; Hoare & Hoe, 2013 ; Hoe & Hoare, 2012 ; Munhall, 2012 ). All studies have weaknesses or flaws; if every flawed study were discarded, no scientific evidence would be available for use in practice. In fact, science itself is flawed. Science does not completely or perfectly describe, explain, predict, or control reality. However, improved understanding and increased ability to predict and control phenomena depend on recognizing the flaws in studies and science. Additional studies can then be planned to minimize the weaknesses of earlier studies. You also need to recognize a study’s strengths to determine the quality of a study and credibility of its findings. When identifying a study’s strengths and weaknesses, you need to provide examples and rationale for your judgments that are documented with current literature. Box 12-1 Key Principles for Critically Appraising Quantitative and Qualitative Studies 1. Read and critically appraise the entire study. A research critical appraisal involves examining the quality of all aspects of the research report. 2. Examine the organization and presentation of the research report. A well-prepared report is complete, concise, clearly presented, and logically organized. It does not include excessive jargon that is difficult for you to read. The references need to be current, complete, and presented in a consistent format. 3. Examine the significance of the problem studied for nursing practice. The focus of nursing studies needs to be on significant practice problems if a sound knowledge base is to be developed for evidence-based nursing practice. 4. Indicate the type of study conducted and identify the steps or elements of the study. This might be done as an initial critical appraisal of a study; it indicates your knowledge of the different types of quantitative and qualitative studies and the steps or elements included in these studies. 5. Identify the strengths and weaknesses of a study. All studies have strengths and weaknesses, so attention must be given to all aspects of the study. 6. Be objective and realistic in identifying the study’s strengths and weaknesses. Be balanced in your critical appraisal of a study. Try not to be overly critical in identifying a study’s weaknesses or overly flattering in identifying the strengths. 7. Provide specific examples of the strengths and weaknesses of a study. Examples provide evidence for your critical appraisal of the strengths and weaknesses of a study. 8. Provide a rationale for your critical appraisal comments. Include justifications for your critical appraisal, and document your ideas with sources from the current literature. This strengthens the quality of your critical appraisal and documents the use of critical thinking skills. 9. Evaluate the quality of the study. Describe the credibility of the findings, consistency of the findings with those from other studies, and quality of the study conclusions. 10. Discuss the usefulness of the findings for practice. The findings from the study need to be linked to the findings of previous studies and examined for use in clinical practice. Critical appraisal of quantitative and qualitative studies involves a final evaluation to determine the credibility of the study findings and any implications for practice and further research (see Box 12-1 ). Adding together the strong points from multiple studies slowly builds a solid base of evidence for practice. These guidelines provide a basis for the critical appraisal process for quantitative research discussed in the next section and the critical appraisal process for qualitative research (see later). Understanding the Quantitative Research Critical Appraisal Process The quantitative research critical appraisal process includes three steps: (1) identifying the steps of the research process in studies; (2) determining study strengths and weaknesses; and (3) evaluating the credibility and meaning of study findings. These steps occur in sequence, vary in depth, and presume accomplishment of the preceding steps. However, an individual with critical appraisal experience frequently performs two or three steps of this process simultaneously. This section includes the three steps of the quantitative research critical appraisal process and provides relevant questions for each step. These questions have been selected as a means for stimulating the logical reasoning and analysis necessary for conducting a critical appraisal of a study. Those experienced in the critical appraisal process often formulate additional questions as part of their reasoning processes. We will identify the steps of the research process separately because those new to critical appraisal start with this step. The questions for determining the study strengths and weaknesses are covered together because this process occurs simultaneously in the mind of the person conducting the critical appraisal. Evaluation is covered separately because of the increased expertise needed to perform this step. Step 1: Identifying the Steps of the Research Process in Studies Initial attempts to comprehend research articles are often frustrating because the terminology and stylized manner of the report are unfamiliar. Identifying the steps of the research process in a quantitative study is the first step in critical appraisal. It involves understanding the terms and concepts in the report, as well as identifying study elements and grasping the nature, significance, and meaning of these elements. The following guidelines will direct you in identifying a study’s elements or steps. Guidelines for Identifying the Steps of the Research Process in Studies The first step involves reviewing the abstract and reading the study from beginning to end. As you read, think about the following questions regarding the presentation of the study: • Was the study title clear? • Was the abstract clearly presented? • Was the writing style of the report clear and concise? • Were relevant terms defined? You might underline the terms you do not understand and determine their meaning from the glossary at the end of this text. • Were the following parts of the research report plainly identified ( APA, 2010 )? • Introduction section, with the problem, purpose, literature review, framework, study variables, and objectives, questions, or hypotheses • Methods section, with the design, sample, intervention (if applicable), measurement methods, and data collection or procedures • Results section, with the specific results presented in tables, figures, and narrative • Discussion section, with the findings, conclusions, limitations, generalizations, implications for practice, and suggestions for future research ( Fawcett & Garity, 2009 ; Grove et al., 2013 ) We recommend reading the research article a second time and highlighting or underlining the steps of the quantitative research process that were identified previously. An overview of these steps is presented in Chapter 2 . After reading and comprehending the content of the study, you are ready to write your initial critical appraisal of the study. To write a critical appraisal identifying the study steps, you need to identify each step of the research process concisely and respond briefly to the following guidelines and questions. 1. Introduction a. Describe the qualifications of the authors to conduct the study (e.g., research expertise conducting previous studies, clinical experience indicated by job, national certification, and years in practice, and educational preparation that includes conducting research [PhD]). b. Discuss the clarity of the article title. Is the title clearly focused and does it include key study variables and population? Does the title indicate the type of study conducted—descriptive, correlational, quasi-experimental, or experimental—and the variables ( Fawcett & Garity, 2009 ; Hoe & Hoare, 2012 ; Shadish, Cook, & Campbell, 2002 )? c. Discuss the quality of the abstract (includes purpose, highlights design, sample, and intervention [if applicable], and presents key results; APA, 2010 ). 2. State the problem. a. Significance of the problem b. Background of the problem c. Problem statement 3. State the purpose. 4. Examine the literature review. a. Are relevant previous studies and theories described? b. Are the references current (number and percentage of sources in the last 5 and 10 years)? c. Are the studies described, critically appraised, and synthesized ( Brown, 2014 ; Fawcett & Garity, 2009 )? Are the studies from referred journals? d. Is a summary provided of the current knowledge (what is known and not known) about the research problem? 5. Examine the study framework or theoretical perspective. a. Is the framework explicitly expressed, or must you extract the framework from statements in the introduction or literature review of the study? b. Is the framework based on tentative, substantive, or scientific theory? Provide a rationale for your answer. c. Does the framework identify, define, and describe the relationships among the concepts of interest? Provide examples of this. d. Is a map of the framework provided for clarity? If a map is not presented, develop a map that represents the study’s framework and describe the map. e. Link the study variables to the relevant concepts in the map. f. How is the framework related to nursing’s body of knowledge ( Alligood, 2010 ; Fawcett & Garity, 2009 ; Smith & Liehr, 2008 )? 6. List any research objectives, questions, or hypotheses. 7. Identify and define (conceptually and operationally) the study variables or concepts that were identified in the objectives, questions, or hypotheses. If objectives, questions, or hypotheses are not stated, identify and define the variables in the study purpose and results section of the study. If conceptual definitions are not found, identify possible definitions for each major study variable. Indicate which of the following types of variables were included in the study. A study usually includes independent and dependent variables or research variables, but not all three types of variables. a. Independent variables: Identify and define conceptually and operationally. b. Dependent variables: Identify and define conceptually and operationally. c. Research variables or concepts: Identify and define conceptually and operationally. 8. Identify attribute or demographic variables and other relevant terms. 9. Identify the research design. a. Identify the specific design of the study (see Chapter 8 ). b. Does the study include a treatment or intervention? If so, is the treatment clearly described with a protocol and consistently implemented? c. If the study has more than one group, how were subjects assigned to groups? d. Are extraneous variables identified and controlled? Extraneous variables are usually discussed as a part of quasi-experimental and experimental studies. e. Were pilot study findings used to design this study? If yes, briefly discuss the pilot and the changes made in this study based on the pilot ( Grove et al., 2013 ; Shadish et al., 2002 ). 10. Describe the sample and setting. a. Identify inclusion and exclusion sample or eligibility criteria. b. Identify the specific type of probability or nonprobability sampling method that was used to obtain the sample. Did the researchers identify the sampling frame for the study? c. Identify the sample size. Discuss the refusal number and percentage, and include the rationale for refusal if presented in the article. Discuss the power analysis if this process was used to determine sample size ( Aberson, 2010 ). d. Identify the sample attrition (number and percentage) for the study. e. Identify the characteristics of the sample. f. Discuss the institutional review board (IRB) approval. Describe the informed consent process used in the study. g. Identify the study setting and indicate whether it is appropriate for the study purpose. 11. Identify and describe each measurement strategy used in the study. The following table includes the critical information about two measurement methods, the Beck Likert scale and a physiological instrument to measure blood pressure. Completing this table will allow you to cover essential measurement content for a study ( Waltz, Strickland, & Lenz, 2010 ). a. Identify each study variable that was measured. b. Identify the name and author of each measurement strategy. c. Identify the type of each measurement strategy (e.g., Likert scale, visual analog scale, physiological measure, or existing database). d. Identify the level of measurement (nominal, ordinal, interval, or ratio) achieved by each measurement method used in the study ( Grove, 2007 ). e. Describe the reliability of each scale for previous studies and this study. Identify the precision of each physiological measure ( Bialocerkowski, Klupp, & Bragge, 2010 ; DeVon et al., 2007 ). f. Identify the validity of each scale and the accuracy of physiological measures ( DeVon et al., 2007 ; Ryan-Wenger, 2010 ). Variable Measured Name of Measurement Method (Author) Type of Measurement Method Level of Measurement Reliability or Precision Validity or Accuracy Depression Beck Depression Inventory (Beck) Likert scale Interval Cronbach alphas of 0.82-0.92 from previous studies and 0.84 for this study; reading level at 6th grade. Construct validity—content validity from concept analysis, literature review, and reviews of experts; convergent validity of 0.04 with Zung Depression Scale; predictive validity of patients’ future depression episodes; successive use validity with the conduct of previous studies and this study. Blood pressure Omron blood pressure (BP) equipment (equipment manufacturer) Physiological measurement method Ratio Test-retest values of BPs in previous studies; BP equipment new and recalibrated every 50 BP readings in this study; average three BP readings to determine BP. Documented accuracy of systolic and diastolic BPs to 1 mm Hg by company developing Omron BP cuff; designated protocol for taking BP average three BP readings to determine BP. 12. Describe the procedures for data collection. 13. Describe the statistical analyses used. a. List the statistical procedures used to describe the sample ( Grove, 2007 ). b. Was the level of significance or alpha identified? If so, indicate what it was (0.05, 0.01, or 0.001). c. Complete the following table with the analysis techniques conducted in the study: (1) identify the focus (description, relationships, or differences) for each analysis technique; (2) list the statistical analysis technique performed; (3) list the statistic; (4) provide the specific results; and (5) identify the probability ( p ) of the statistical significance achieved by the result ( Grove, 2007 ; Grove et al., 2013 ; Hoare & Hoe, 2013 ; Plichta & Kelvin, 2013 ). Purpose of Analysis Analysis Technique Statistic Results Probability (p) Description of subjects’ pulse rate Mean Standard deviation Range M SD range 71.52 5.62 58-97 Difference between adult males and females on blood pressure t -Test t 3.75 p = 0.001 Differences of diet group, exercise group, and comparison group for pounds lost in adolescents Analysis of variance F 4.27 p = 0.04 Relationship of depression and anxiety in older adults Pearson correlation r 0.46 p = 0.03 14. Describe the researcher’s interpretation of findings. a. Are the findings related back to the study framework? If so, do the findings support the study framework? b. Which findings are consistent with those expected? c. Which findings were not expected? d. Are the findings consistent with previous research findings? ( Fawcett & Garity, 2009 ; Grove et al., 2013 ; Hoare & Hoe, 2013 ) 15. What study limitations did the researcher identify? 16. What conclusions did the researchers identify based on their interpretation of the study findings? 17. How did the researcher generalize the findings? 18. What were the implications of the findings for nursing practice? 19. What suggestions for further study were identified? 20. Is the description of the study sufficiently clear for replication? Step 2: Determining the Strengths and Weaknesses in Studies The second step in critically appraising studies requires determining strengths and weaknesses in the studies . To do this, you must have knowledge of what each step of the research process should be like from expert sources such as this text and other research sources ( Aberson, 2010 ; Bialocerkowski et al., 2010 ; Brown, 2014 ; Creswell, 2014 ; DeVon et al., 2007 ; Doran, 2011 ; Fawcett & Garity, 2009 ; Grove, 2007 ; Grove et al., 2013 ; Hoare & Hoe, 2013 ; Hoe & Hoare, 2012 ; Morrison, Hoppe, Gillmore, Kluver, Higa, & Wells, 2009 ; O’Mathuna et al., 2011 ; Ryan-Wenger, 2010 ; Santacroce, Maccarelli, & Grey, 2004 ; Shadish et al., 2002 ; Waltz et al., 2010 ). The ideal ways to conduct the steps of the research process are then compared with the actual study steps. During this comparison, you examine the extent to which the researcher followed the rules for an ideal study, and the study elements are examined for strengths and weaknesses. You also need to examine the logical links or flow of the steps in the study being appraised. For example, the problem needs to provide background and direction for the statement of the purpose. The variables identified in the study purpose need to be consistent with the variables identified in the research objectives, questions, or hypotheses. The variables identified in the research objectives, questions, or hypotheses need to be conceptually defined in light of the study framework. The conceptual definitions should provide the basis for the development of operational definitions. The study design and analyses need to be appropriate for the investigation of the study purpose, as well as for the specific objectives, questions, or hypotheses. Examining the quality and logical links among the study steps will enable you to determine which steps are strengths and which steps are weaknesses. Guidelines for Determining the Strengths and Weaknesses in Studies The following questions were developed to help you examine the different steps of a study and determine its strengths and weaknesses. The intent is not for you to answer each of these questions but to read the questions and then make judgments about the steps in the study. You need to provide a rationale for your decisions and document from relevant research sources, such as those listed previously in this section and in the references at the end of this chapter. For example, you might decide that the study purpose is a strength because it addresses the study problem, clarifies the focus of the study, and is feasible to investigate ( Brown, 2014 ; Fawcett & Garity, 2009 ; Hoe & Hoare, 2012 ). 1. Research problem and purpose a. Is the problem significant to nursing and clinical practice ( Brown, 2014 )? b. Does the purpose narrow and clarify the focus of the study ( Creswell, 2014 ; Fawcett & Garity, 2009 )? c. Was this study feasible to conduct in terms of money commitment, the researchers’ expertise; availability of subjects, facilities, and equipment; and ethical considerations? 2. Review of literature a. Is the literature review organized to demonstrate the progressive development of evidence from previous research ( Brown, 2014 ; Creswell, 2014 ; Hoe & Hoare, 2012 )? b. Is a clear and concise summary presented of the current empirical and theoretical knowledge in the area of the study ( O’Mathuna et al., 2011 )? c. Does the literature review summary identify what is known and not known about the research problem and provide direction for the formation of the research purpose? 3. Study framework a. Is the framework presented with clarity? If a model or conceptual map of the framework is present, is it adequate to explain the phenomenon of concern ( Grove et al., 2013 )? b. Is the framework related to the body of knowledge in nursing and clinical practice? c. If a proposition from a theory is to be tested, is the proposition clearly identified and linked to the study hypotheses ( Alligood, 2010 ; Fawcett & Garity, 2009 ; Smith & Liehr, 2008 )? 4. Research objectives, questions, or hypotheses a. Are the objectives, questions, or hypotheses expressed clearly? b. Are the objectives, questions, or hypotheses logically linked to the research purpose? c. Are hypotheses stated to direct the conduct of quasi-experimental and experimental research ( Creswell, 2014 ; Shadish et al., 2002 )? d. Are the objectives, questions, or hypotheses logically linked to the concepts and relationships (propositions) in the framework ( Chinn & Kramer, 2011 ; Fawcett & Garity, 2009 ; Smith & Liehr, 2008 )? 5. Variables a. Are the variables reflective of the concepts identified in the framework? b. Are the variables clearly defined (conceptually and operationally) and based on previous research or theories ( Chinn & Kramer, 2011 ; Grove et al., 2013 ; Smith & Liehr, 2008 )? c. Is the conceptual definition of a variable consistent with the operational definition? 6. Design a. Is the design used in the study the most appropriate design to obtain the needed data ( Creswell, 2014 ; Grove et al., 2013 ; Hoe & Hoare, 2012 )? b. Does the design provide a means to examine all the objectives, questions, or hypotheses? c. Is the treatment clearly described ( Brown, 2002 )? Is the treatment appropriate for examining the study purpose and hypotheses? Does the study framework explain the links between the treatment (independent variable) and the proposed outcomes (dependent variables)? Was a protocol developed to promote consistent implementation of the treatment to ensure intervention fidelity ( Morrison et al., 2009 )? Did the researcher monitor implementation of the treatment to ensure consistency ( Santacroce et al., 2004 )? If the treatment was not consistently implemented, what might be the impact on the findings? d. Did the researcher identify the threats to design validity (statistical conclusion validity, internal validity, construct validity, and external validity [see Chapter 8 ]) and minimize them as much as possible ( Grove et al., 2013 ; Shadish et al., 2002 )? e. If more than one group was used, did the groups appear equivalent? f. If a treatment was implemented, were the subjects randomly assigned to the treatment group or were the treatment and comparison groups matched? Were the treatment and comparison group assignments appropriate for the purpose of the study? 7. Sample, population, and setting a. Is the sampling method adequate to produce a representative sample? Are any subjects excluded from the study because of age, socioeconomic status, or ethnicity, without a sound rationale? b. Did the sample include an understudied population, such as young people, older adults, or minority group? c. Were the sampling criteria (inclusion and exclusion) appropriate for the type of study conducted ( O’Mathuna et al., 2011 )? d. Was a power analysis conducted to determine sample size? If a power analysis was conducted, were the results of the analysis clearly described and used to determine the final sample size? Was the attrition rate projected in determining the final sample size ( Aberson, 2010 )? e. Are the rights of human subjects protected ( Creswell, 2014 ; Grove et al., 2013 )? f. Is the setting used in the study typical of clinical settings? g. Was the rate of potential subjects’ refusal to participate in the study a problem? If so, how might this weakness influence the findings? h. Was sample attrition a problem? If so, how might this weakness influence the final sample and the study results and findings ( Aberson, 2010 ; Fawcett & Garity, 2009 ; Hoe & Hoare, 2012 )? 8. Measurements a. Do the measurement methods selected for the study adequately measure the study variables? Should additional measurement methods have been used to improve the quality of the study outcomes ( Waltz et al., 2010 )? b. Do the measurement methods used in the study have adequate validity and reliability? What additional reliability or validity testing is needed to improve the quality of the measurement methods ( Bialocerkowski et al., 2010 ; DeVon et al., 2007 ; Roberts & Stone, 2003 )? c. Respond to the following questions, which are relevant to the measurement approaches used in the study: 1) Scales and questionnaires (a) Are the instruments clearly described? (b) Are techniques to complete and score the instruments provided? (c) Are the validity and reliability of the instruments described ( DeVon et al., 2007 )? (d) Did the researcher reexamine the validity and reliability of the instruments for the present sample? (e) If the instrument was developed for the study, is the instrument development process described ( Grove et al., 2013 ; Waltz et al., 2010 )? 2) Observation (a) Is what is to be observed clearly identified and defined? (b) Is interrater reliability described? (c) Are the techniques for recording observations described ( Waltz et al., 2010 )? 3) Interviews (a) Do the interview questions address concerns expressed in the research problem? (b) Are the interview questions relevant for the research purpose and objectives, questions, or hypotheses ( Grove et al., 2013 ; Waltz et al., 2010 )? 4) Physiological measures (a) Are the physiological measures or instruments clearly described ( Ryan-Wenger, 2010 )? If appropriate, are the brand names of the instruments identified, such as Space Labs or Hewlett-Packard? (b) Are the accuracy, precision, and error of the physiological instruments discussed ( Ryan-Wenger, 2010 )? (c) Are the physiological measures appropriate for the research purpose and objectives, questions, or hypotheses? (d) Are the methods for recording data from the physiological measures clearly described? Is the recording of data consistent? 9. Data collection a. Is the data collection process clearly described ( Fawcett & Garity, 2009 ; Grove et al., 2013 )? b. Are the forms used to collect data organized to facilitate computerizing the data? c. Is the training of data collectors clearly described and adequate? d. Is the data collection process conducted in a consistent manner? e. Are the data collection methods ethical? f. Do the data collected address the research objectives, questions, or hypotheses? g. Did any adverse events occur during data collection, and were these appropriately managed? 10. Data analysis a. Are data analysis procedures appropriate for the type of data collected ( Grove, 2007 ; Hoare & Hoe, 2013 ; Plichta & Kelvin, 2013 )? b. Are data analysis procedures clearly described? Did the researcher address any problem with missing data, and explain how this problem was managed? c. Do the data analysis techniques address the study purpose and the research objectives, questions, or hypotheses ( Fawcett & Garity, 2009 ; Grove et al., 2013 ; Hoare & Hoe, 2013 )? d. Are the results presented in an understandable way by narrative, tables, or figures or a combination of methods ( APA, 2010 )? e. Is the sample size sufficient to detect significant differences, if they are present? f. Was a power analysis conducted for nonsignificant results (Aberson, 2010) ? g. Are the results interpreted appropriately?

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Related posts:

- Outcomes Research

- Understanding Statistics in Research

- Research Problems, Purposes, and Hypotheses

- Clarifying Quantitative Research Designs

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Comments are closed for this page.

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Postgraduate Nursing: Critical appraisal and Evaluation of research

- EndNote & Referencing

- Academic Writing

- Research & Research Methods

- Introduction to Evidence-Informed Practice

- Asking a Clinical Question

- Types of Research & Levels of Evidence

- Searching for the Evidence

- Critical appraisal and Evaluation of research

- Searching and appraising evidence demonstration

- Journals & Journal Articles

- Grey Literature & Statistics

- Search Tips

- CINAHL Plus with Full Text

- Medline & PsycINFO

- Cochrane Library

- Clinical Governance

- Anatomy & Physiology Resources

- Drug Resources

- Clinical Education

- Contact and feedback

Introduction to critical appraisal and evaluation

The information you use in your research and study must all be credible, reliable and relevant. Part of the Evidence-Based Practice process is to critically appraise scientific papers, but in general, all the resources you refer to should be evaluated carefully to ensure their credibility.

How can you tell whether the resources you've found are credible and suitable for you to reference? To evaluate Information you have found on websites, see the video below and the box on using Internet sites. Journal articles and academic texts should at least have gone through a process of peer review (see the video about peer review on the Journals page of this guide).

Critical appraisal of scientific papers takes the evaluation to another level. Once you have asked the clinical question and searched for evidence, it's often not enough that you've checked for peer review if you want to find the very best evidence - it will ensure that studies with scientific flaws are disregarded, and the ones you include are relevant to your question.

In the Evidence-Based Practice process, and especially in the process of evaluating primary research (which hasn't be pre-appraised or filtered by others), we need to go beyond the usual general information evaluation and make sure the evidence we are using is scientifically rigorous. The main questions to address are:

- Is the study relevant to your clinical question?

- How well (scientifically) was the study done, especially taking care to eliminate bias?

- What do the results mean and are they statistically valid (and not just due to chance)?

For a more detailed look at Critical Appraisal, head to the Systematic Review Guide - Critical Appraisal and the Evidence-Based Practic Guide - Appraise.

Critical appraisal tools

Fortunately, there have been some great checklist tools developed for different types of studies. Here are some examples:

- The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) provides access to critical appraisal tools, a collection of checklists that you can use to help you appraise or evaluate research.

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) is part of Better Value Healthcare based in Oxford, UK. It includes a series of checklists , suitable for different types of studies and designed to be used when reading research.

- The Equator Network is devoted to Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research. Among other functions, they include a Toolkit for Peer Reviewing Health Research which is very useful as a guide for critically appraising studies.

- Critical Appraisal Tools (CEBM) - This site from the Centre of Evidence Based Medicine includes tools and worksheets for the critical appraisal of different types of medical evidence.

- Critical Appraisal Tools (iCAHE) - This site from the International Centre of Allied Health Evidence (at the University of South Australia) has a range of tools for various types of studies.

- Understanding Health Research - is from the Medical Research Council in the UK. It's a very handy all-purpose tool which takes you through a series of questions about a particular article, highlighting the good points and possible problem areas. You can print off a summary at the end of your checklist

Critical appraisal tools from the NHS in Scotland links interactively to all sorts of resources on how to identify the study type and build your critical appraisal skills, as well as to tools themselves.

Critical reading and understanding research

A useful series of articles for nurses about critiquing and understanding types of research has been published in the Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing by Rebecca Ingham-Broomfield, from the University of New South Wales:

Ingham-Broomfield, R. (2014). A nurses' guide to the critical reading of research . Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing , 32 (1), 37-44. [Updated from 2008.]

Ingham-Broomfield, R. (2014). A nurses' guide to quantitative research . Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, 32 (2), 32-38.

Ingham-Broomfield, R. (2015). A nurses' guide to qualitative research . Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, 32 (3), 34-40.

Ingham-Broomfield, R. (2016). A nurses' guide to mixed methods research . Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, 33 (4), 46-52.

Ingham-Broomfield, R. (2016). A nurses' guide to the hierarchy of research designs and evidence . The Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, 33 (3), 38-43.

Evaluate internet resources

The website domain gives you an idea of the reliability of a website:

Critical appraisal resources

Introduction to Critical Appraisal - This short video from the library at the University of Sheffield in the UK looks at the background to critical appraisal, what it is, and why we do it. A very useful introduction to the topic.

Evaluating information

- << Previous: Searching for the Evidence

- Next: Searching and appraising evidence demonstration >>

- Last Updated: Mar 7, 2024 11:12 AM

- URL: https://libguides.csu.edu.au/MN

Charles Sturt University is an Australian University, TEQSA Provider Identification: PRV12018. CRICOS Provider: 00005F.

Critical Appraisal Resources for Evidence-Based Nursing Practice

What is critical appraisal, critical appraisal tools, video: learn more about the joanna briggs institute.

- Levels of Evidence

- Systematic Reviews

- Randomized Controlled Trials

- Quasi-Experimental Studies

- Case-Control Studies

- Cohort Studies

- Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies

- Qualitative Research

Recommended Books on Critical Appraisal

Critical appraisal is an essential and important step in the evidence-based practice (EBP) process. It involves analyzing and critiquing the methodology and data of published research studies (both quantitative and qualitative designs) to determine the value, reliability, trustworthiness, and relevance of those studies in answering a clinical question.

Looking for critical appraisal tools? Click here to access.

RECOMMENDED READING:

Buccheri, R. K., & Sharifi, C. (2017). Critical appraisal tools and reporting guidelines for evidence-based practice . Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing , 14 (6), 463–472. https://doi.org/10.1111/wvn.12258

Definitions of critical appraisal are provided below:

“Judging the quality of information in terms of its validity and degree of bias (quantitative research) and credibility and dependability (qualitative research). This is a critical step in the evidence-based practice process” (Hopp & Rittenmeyer, 2021, p. 360).

“During appraisal, the study design, how the research was conducted, and the data analysis are all scrutinized to ensure that the study was sound” (Schmidt & Brown, 2019, p. 405).

“Critical appraisal is an assessment of the benefits and strengths of research against its flaws and weaknesses” (Holly, Salmond, & Saimbert, 2012, p. 147).

Holly, C., Salmond, S.W., & Saimbert, M. (2012). Comprehensive systematic review for advanced nursing practice. New York: Springer.

Hopp, L., & Rittenmeyer, L. (2021). Introduction to evidence-based practice: A practical guide for nursing. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis.

Schmidt, N.A., & Brown, J.M. (2019). Evidence-based practice for nurses: Appraisal and application of research. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett.

A variety of critical appraisal tools are available from different organizations to help guide you through the appraisal process.

The following links will connect you to these tools.

- Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) - Critical Appraisal Tools

- Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM) - Critical Appraisal Tools

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) - Critical Appraisal Tools

- Critical Appraisal Tools Collection of links to various checklists by study type

- AMSTAR Checklist Tool for appraising systematic reviews

- AGREE Tools Tools for appraising practice guidelines

The Joanna Briggs Institute is a non-profit, international research and development organization for the promotion and implementation of evidence-based practice in healthcare. The JBI Critical Appraisal Checklists are utilized the world over by healthcare practitioners and researchers who conduct EBP. Learn more about JBI by visiting their website or watch the following video:

- Next: Levels of Evidence >>

- Last Updated: Feb 22, 2024 11:26 AM

- URL: https://libguides.utoledo.edu/nursingappraisal

- NCSBN Member Login Submit

Access provided by

Login to your account

If you don't remember your password, you can reset it by entering your email address and clicking the Reset Password button. You will then receive an email that contains a secure link for resetting your password

If the address matches a valid account an email will be sent to __email__ with instructions for resetting your password

Download started.

- Academic & Personal: 24 hour online access

- Corporate R&D Professionals: 24 hour online access

- Add To Online Library Powered By Mendeley

- Add To My Reading List

- Export Citation

- Create Citation Alert

Nursing Research: Methods and Critical Appraisal for Evidence-Based Practice

- Geri LoBiondo-Wood Geri LoBiondo-Wood Search for articles by this author

- Judith Haber Judith Haber Search for articles by this author

Purchase one-time access:

- For academic or personal research use, select 'Academic and Personal'

- For corporate R&D use, select 'Corporate R&D Professionals'

Article info

© 2014 Elsevier Mosby. ISBN: 978-0-323-10086-1

Identification

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2155-8256(15)30102-2

ScienceDirect

Related articles.

- Download Hi-res image

- Download .PPT

- Access for Developing Countries

- Articles & Issues

- Current Issue

- List of Issues

- Supplements

- For Authors

- Guide for Authors

- Author Services

- Permissions

- Researcher Academy

- Submit a Manuscript

- Journal Info

- About the Journal

- Contact Information

- Editorial Board

- New Content Alerts

- Call for Papers

- January & April 2022 Issues

The content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Accessibility

- Help & Contact

- Cancer Nursing Practice

- Emergency Nurse

- Evidence-Based Nursing

- Learning Disability Practice

- Mental Health Practice

- Nurse Researcher

- Nursing Children and Young People

- Nursing Management

- Nursing Older People

- Nursing Standard

- Primary Health Care

- RCN Nursing Awards

- Nursing Live

- Nursing Careers and Job Fairs

- CPD webinars on-demand

- --> Advanced -->

- Clinical articles

- CPD articles

- CPD Quizzes

- Expert advice

- Clinical placements

- Study skills

- Clinical skills

- University life

- Person-centred care

- Career advice

- Revalidation

Research Previous Next

Guidelines on conducting a critical research evaluation, gill hek , senior lecturer, university of the west of england, bristol.

This article outlines the reasons why nurses need to be able to read and evaluate research reports critically, and provides a step-by-step approach to conducting a critical appraisal of a research article

The ability to evaluate or appraise research in a critical manner is a skill that all nurses must develop. By acquiring and using these skills nurses will be able to understand and appreciate research. For those nurses who have qualified in the last four or five years, critical appraisal or critical evaluation skills may have been learnt during their pre-registration course. However, the vast majority of qualified nurses who undertook their training prior to Project 2000, are unlikely to have had the opportunity to develop such skills. Furthermore, many nurses undertake post-registration courses, and most of these courses will require them to gain competency in critical evaluation skills, often assessed through assignments and project work.

Nursing Standard . 11, 6, 40-43. doi: 10.7748/ns.11.6.40.s48

■ Nursing research - ■ Nursing literature - ■ Quality of nursing practice

User not found

Want to read more?

Already have access log in, 3-month trial offer for £5.25/month.

- Unlimited access to all 10 RCNi Journals

- RCNi Learning featuring over 175 modules to easily earn CPD time

- NMC-compliant RCNi Revalidation Portfolio to stay on track with your progress

- Personalised newsletters tailored to your interests

- A customisable dashboard with over 200 topics

Alternatively, you can purchase access to this article for the next seven days. Buy now

Are you a student? Our student subscription has content especially for you. Find out more

30 October 1996 / Vol 11 issue 6

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DIGITAL EDITION

- LATEST ISSUE

- SIGN UP FOR E-ALERT

- WRITE FOR US

- PERMISSIONS

Share article: Guidelines on conducting a critical research evaluation

We use cookies on this site to enhance your user experience.

By clicking any link on this page you are giving your consent for us to set cookies.

Evidence Based Practice Guide for Nursing Students: Appraisal

- Getting Started

- Levels of Evidence

- APA Style Guides

What is Critical Appraisal?

Critical appraisal.

Critical appraisal is an essential part of the Evidence Based Practice process. Critical appraisal identifies possible flaws or problems with the study methodology, the transparency of the study design as written in the article, the quality of the research, and level of evidence.

Appraisal Concepts - Validity & Reliability

What is validity.

Internal validity is the extent to which the experiment demonstrated a cause-effect relationship between the independent and dependent variables.

External validity is the extent to which one may safely generalize from the sample studied to the defined target population and to other populations.

What is reliability?

Reliability is the extent to which the results of the experiment are replicable. The research methodology should be described in detail so that the experiment could be repeated with similar results.

More Useful Scientific Terminology

Critically Appraised Topics (CATS)

CATs are critical summaries of a research article. They are concise, standardized, and provide an appraisal of the research.

If a CAT already exists for an article, it can be read quickly and the clinical bottom line can be put to use as the clinician sees fit. If a CAT does not exist, the CAT format provides a template to appraise the article of interest.

- CEBM's CATMaker tool helps you create your own CATs

Evaluating a Study

Start by asking simple questions about the article:

- Have the study aims been clearly stated?

- Does the sample accurately reflect the population?

- Has the sampling method and size been described and justified?

- Have exclusions been stated?

- Is the control group easily identified?

- Is the loss to follow-up detailed?

- Are enough details included so that the results could be replicated?

- Are there confounding factors?

- Are the conclusions logical?

- Do the findings match the study aims?

- Can the results be extrapolated to other populations?

Attribution Statement: University of Illinois Chicago. Library of the Health Sciences. Evidence Based Medicine. https://researchguides.uic.edu/ebm . Used under a CC BY-NC license.

Critical Appraisal Tools

- CASP UK Critical Appraisal Skills Programme

- Centre for Evidence Based Medicine

- Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Checklists

- GRADE Working Group

Videos from NCCMT

- Number Needed to Treat (10:42 min.)

- Relative Risk (10:40 min.)

- Types of Reviews: What Type of Review Do You Need? (9:22 min.)

- Importance of Clinical Significance (3:41 min.)

- How to Calculate an Odds Ratio (5:51)

- Understanding a Confidence Interval (5:29 min.)

NCCMT, National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools, is a Canadian agency that provides leadership, education and expertise to promote informed decision-making in public health.

- << Previous: Search

- Next: APA Style Guides >>

- Last Updated: Feb 19, 2024 12:10 PM

- URL: https://uwyo.libguides.com/EBP-BSN

How to critically appraise a qualitative health research study

Affiliations.

- 1 RN, MScN, PhD, School of Nursing, Dept. of Medicine and Surgery, University of Milano - Bicocca, Milan, Italy. Email: [email protected].

- 2 RN MScN PhD student, School of Nursing, McMaster University,Hamilton, Ontario, Canada.

- 3 RN, PhD student, School of Nursing, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada.

- 4 RN, MScN PhD, School of Nursing, Dept. of Medicine and Surgery, University of Milano - Bicocca, Milan, Italy.

- 5 RN, PhD, School of Nursing, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada.

- PMID: 32243743

Abstract in English, Italian

Evidence-based nursing is a process that requires nurses to have the knowledge, skills, and confidence to critically reflect on their practice, articulate structured questions, and then reliably search for research evidence to address the questions posed. Many types of research evidence are used to inform decisions in health care and findings from qualita- tive health research studies are useful to provide new insights about individuals' experi- ences, values, beliefs, needs, or perceptions. Before qualitative evidence can be utilized in a decision, it must be critically appraised to determine if the findings are trustworthy and if they have relevance to the identified issue or decision. In this article, we provide practical guidance on how to select a checklist or tool to guide the critical appraisal of qualitative studies and then provide an example demonstrating how to apply the critical appraisal process to a clinical scenario.

L’Evidence-Based Nursing Ë un processo che richiede agli infermieri di avere le conoscenze, le competenze e la fiducia necessarie per riflettere criticamente sulla loro pratica, articolare domande strutturate e poi cercare in modo affidabile la letteratura per rispondere alle domande poste. Ci sono molti tipi di evidence che vengono utilizzate per informare le decisioni nell'as- sistenza sanitaria e i risultati di studi di ricerca qualitativa sanitaria sono utili per fornire nuove intuizioni sulle esperienze, i valori, le convinzioni, i bisogni o le percezioni degli individui. Prima che l'evidence qualitativa possa essere utilizzata in una decisione, deve essere valutata criticamente per determinare se i risultati sono affidabili e se hanno rilevanza per la questione o la decisione identificata. In questo articolo forniamo una guida pratica su come selezionare una checklist o uno strumento per guidare la valutazione critica degli studi qualitativi e, poi, forniamo un esempio che dimostra come applicare il processo di valutazione critica a uno scenario clinico.

- Clinical Competence

- Delivery of Health Care / organization & administration

- Delivery of Health Care / standards

- Evidence-Based Nursing / organization & administration*

- Health Knowledge, Attitudes, Practice

- Health Services Research / organization & administration

- Health Services Research / standards

- Nurses / organization & administration*

- Nurses / standards

- Qualitative Research*

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Write for Us

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 21, Issue 4

- How to appraise quantitative research

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

This article has a correction. Please see:

- Correction: How to appraise quantitative research - April 01, 2019

- Xabi Cathala 1 ,

- Calvin Moorley 2

- 1 Institute of Vocational Learning , School of Health and Social Care, London South Bank University , London , UK

- 2 Nursing Research and Diversity in Care , School of Health and Social Care, London South Bank University , London , UK

- Correspondence to Mr Xabi Cathala, Institute of Vocational Learning, School of Health and Social Care, London South Bank University London UK ; cathalax{at}lsbu.ac.uk and Dr Calvin Moorley, Nursing Research and Diversity in Care, School of Health and Social Care, London South Bank University, London SE1 0AA, UK; Moorleyc{at}lsbu.ac.uk

https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2018-102996

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Introduction

Some nurses feel that they lack the necessary skills to read a research paper and to then decide if they should implement the findings into their practice. This is particularly the case when considering the results of quantitative research, which often contains the results of statistical testing. However, nurses have a professional responsibility to critique research to improve their practice, care and patient safety. 1 This article provides a step by step guide on how to critically appraise a quantitative paper.

Title, keywords and the authors

The authors’ names may not mean much, but knowing the following will be helpful:

Their position, for example, academic, researcher or healthcare practitioner.

Their qualification, both professional, for example, a nurse or physiotherapist and academic (eg, degree, masters, doctorate).

This can indicate how the research has been conducted and the authors’ competence on the subject. Basically, do you want to read a paper on quantum physics written by a plumber?

The abstract is a resume of the article and should contain:

Introduction.

Research question/hypothesis.

Methods including sample design, tests used and the statistical analysis (of course! Remember we love numbers).

Main findings.

Conclusion.

The subheadings in the abstract will vary depending on the journal. An abstract should not usually be more than 300 words but this varies depending on specific journal requirements. If the above information is contained in the abstract, it can give you an idea about whether the study is relevant to your area of practice. However, before deciding if the results of a research paper are relevant to your practice, it is important to review the overall quality of the article. This can only be done by reading and critically appraising the entire article.

The introduction

Example: the effect of paracetamol on levels of pain.

My hypothesis is that A has an effect on B, for example, paracetamol has an effect on levels of pain.

My null hypothesis is that A has no effect on B, for example, paracetamol has no effect on pain.

My study will test the null hypothesis and if the null hypothesis is validated then the hypothesis is false (A has no effect on B). This means paracetamol has no effect on the level of pain. If the null hypothesis is rejected then the hypothesis is true (A has an effect on B). This means that paracetamol has an effect on the level of pain.

Background/literature review

The literature review should include reference to recent and relevant research in the area. It should summarise what is already known about the topic and why the research study is needed and state what the study will contribute to new knowledge. 5 The literature review should be up to date, usually 5–8 years, but it will depend on the topic and sometimes it is acceptable to include older (seminal) studies.

Methodology

In quantitative studies, the data analysis varies between studies depending on the type of design used. For example, descriptive, correlative or experimental studies all vary. A descriptive study will describe the pattern of a topic related to one or more variable. 6 A correlational study examines the link (correlation) between two variables 7 and focuses on how a variable will react to a change of another variable. In experimental studies, the researchers manipulate variables looking at outcomes 8 and the sample is commonly assigned into different groups (known as randomisation) to determine the effect (causal) of a condition (independent variable) on a certain outcome. This is a common method used in clinical trials.

There should be sufficient detail provided in the methods section for you to replicate the study (should you want to). To enable you to do this, the following sections are normally included:

Overview and rationale for the methodology.

Participants or sample.

Data collection tools.

Methods of data analysis.

Ethical issues.

Data collection should be clearly explained and the article should discuss how this process was undertaken. Data collection should be systematic, objective, precise, repeatable, valid and reliable. Any tool (eg, a questionnaire) used for data collection should have been piloted (or pretested and/or adjusted) to ensure the quality, validity and reliability of the tool. 9 The participants (the sample) and any randomisation technique used should be identified. The sample size is central in quantitative research, as the findings should be able to be generalised for the wider population. 10 The data analysis can be done manually or more complex analyses performed using computer software sometimes with advice of a statistician. From this analysis, results like mode, mean, median, p value, CI and so on are always presented in a numerical format.

The author(s) should present the results clearly. These may be presented in graphs, charts or tables alongside some text. You should perform your own critique of the data analysis process; just because a paper has been published, it does not mean it is perfect. Your findings may be different from the author’s. Through critical analysis the reader may find an error in the study process that authors have not seen or highlighted. These errors can change the study result or change a study you thought was strong to weak. To help you critique a quantitative research paper, some guidance on understanding statistical terminology is provided in table 1 .

- View inline

Some basic guidance for understanding statistics

Quantitative studies examine the relationship between variables, and the p value illustrates this objectively. 11 If the p value is less than 0.05, the null hypothesis is rejected and the hypothesis is accepted and the study will say there is a significant difference. If the p value is more than 0.05, the null hypothesis is accepted then the hypothesis is rejected. The study will say there is no significant difference. As a general rule, a p value of less than 0.05 means, the hypothesis is accepted and if it is more than 0.05 the hypothesis is rejected.

The CI is a number between 0 and 1 or is written as a per cent, demonstrating the level of confidence the reader can have in the result. 12 The CI is calculated by subtracting the p value to 1 (1–p). If there is a p value of 0.05, the CI will be 1–0.05=0.95=95%. A CI over 95% means, we can be confident the result is statistically significant. A CI below 95% means, the result is not statistically significant. The p values and CI highlight the confidence and robustness of a result.

Discussion, recommendations and conclusion

The final section of the paper is where the authors discuss their results and link them to other literature in the area (some of which may have been included in the literature review at the start of the paper). This reminds the reader of what is already known, what the study has found and what new information it adds. The discussion should demonstrate how the authors interpreted their results and how they contribute to new knowledge in the area. Implications for practice and future research should also be highlighted in this section of the paper.

A few other areas you may find helpful are:

Limitations of the study.

Conflicts of interest.

Table 2 provides a useful tool to help you apply the learning in this paper to the critiquing of quantitative research papers.

Quantitative paper appraisal checklist

- 1. ↵ Nursing and Midwifery Council , 2015 . The code: standard of conduct, performance and ethics for nurses and midwives https://www.nmc.org.uk/globalassets/sitedocuments/nmc-publications/nmc-code.pdf ( accessed 21.8.18 ).

- Gerrish K ,

- Moorley C ,

- Tunariu A , et al

- Shorten A ,

Competing interests None declared.

Patient consent Not required.

Provenance and peer review Commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Correction notice This article has been updated since its original publication to update p values from 0.5 to 0.05 throughout.

Linked Articles

- Miscellaneous Correction: How to appraise quantitative research BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and RCN Publishing Company Ltd Evidence-Based Nursing 2019; 22 62-62 Published Online First: 31 Jan 2019. doi: 10.1136/eb-2018-102996corr1

Read the full text or download the PDF:

- Open access

- Published: 19 March 2024

Interventions, methods and outcome measures used in teaching evidence-based practice to healthcare students: an overview of systematic reviews

- Lea D. Nielsen 1 ,

- Mette M. Løwe 2 ,

- Francisco Mansilla 3 ,

- Rene B. Jørgensen 4 ,

- Asviny Ramachandran 5 ,

- Bodil B. Noe 6 &

- Heidi K. Egebæk 7

BMC Medical Education volume 24 , Article number: 306 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

304 Accesses

Metrics details