This is the Difference Between a Hypothesis and a Theory

What to Know A hypothesis is an assumption made before any research has been done. It is formed so that it can be tested to see if it might be true. A theory is a principle formed to explain the things already shown in data. Because of the rigors of experiment and control, it is much more likely that a theory will be true than a hypothesis.

As anyone who has worked in a laboratory or out in the field can tell you, science is about process: that of observing, making inferences about those observations, and then performing tests to see if the truth value of those inferences holds up. The scientific method is designed to be a rigorous procedure for acquiring knowledge about the world around us.

In scientific reasoning, a hypothesis is constructed before any applicable research has been done. A theory, on the other hand, is supported by evidence: it's a principle formed as an attempt to explain things that have already been substantiated by data.

Toward that end, science employs a particular vocabulary for describing how ideas are proposed, tested, and supported or disproven. And that's where we see the difference between a hypothesis and a theory .

A hypothesis is an assumption, something proposed for the sake of argument so that it can be tested to see if it might be true.

In the scientific method, the hypothesis is constructed before any applicable research has been done, apart from a basic background review. You ask a question, read up on what has been studied before, and then form a hypothesis.

What is a Hypothesis?

A hypothesis is usually tentative, an assumption or suggestion made strictly for the objective of being tested.

When a character which has been lost in a breed, reappears after a great number of generations, the most probable hypothesis is, not that the offspring suddenly takes after an ancestor some hundred generations distant, but that in each successive generation there has been a tendency to reproduce the character in question, which at last, under unknown favourable conditions, gains an ascendancy. Charles Darwin, On the Origin of Species , 1859 According to one widely reported hypothesis , cell-phone transmissions were disrupting the bees' navigational abilities. (Few experts took the cell-phone conjecture seriously; as one scientist said to me, "If that were the case, Dave Hackenberg's hives would have been dead a long time ago.") Elizabeth Kolbert, The New Yorker , 6 Aug. 2007

What is a Theory?

A theory , in contrast, is a principle that has been formed as an attempt to explain things that have already been substantiated by data. It is used in the names of a number of principles accepted in the scientific community, such as the Big Bang Theory . Because of the rigors of experimentation and control, its likelihood as truth is much higher than that of a hypothesis.

It is evident, on our theory , that coasts merely fringed by reefs cannot have subsided to any perceptible amount; and therefore they must, since the growth of their corals, either have remained stationary or have been upheaved. Now, it is remarkable how generally it can be shown, by the presence of upraised organic remains, that the fringed islands have been elevated: and so far, this is indirect evidence in favour of our theory . Charles Darwin, The Voyage of the Beagle , 1839 An example of a fundamental principle in physics, first proposed by Galileo in 1632 and extended by Einstein in 1905, is the following: All observers traveling at constant velocity relative to one another, should witness identical laws of nature. From this principle, Einstein derived his theory of special relativity. Alan Lightman, Harper's , December 2011

Non-Scientific Use

In non-scientific use, however, hypothesis and theory are often used interchangeably to mean simply an idea, speculation, or hunch (though theory is more common in this regard):

The theory of the teacher with all these immigrant kids was that if you spoke English loudly enough they would eventually understand. E. L. Doctorow, Loon Lake , 1979 Chicago is famous for asking questions for which there can be no boilerplate answers. Example: given the probability that the federal tax code, nondairy creamer, Dennis Rodman and the art of mime all came from outer space, name something else that has extraterrestrial origins and defend your hypothesis . John McCormick, Newsweek , 5 Apr. 1999 In his mind's eye, Miller saw his case suddenly taking form: Richard Bailey had Helen Brach killed because she was threatening to sue him over the horses she had purchased. It was, he realized, only a theory , but it was one he felt certain he could, in time, prove. Full of urgency, a man with a mission now that he had a hypothesis to guide him, he issued new orders to his troops: Find out everything you can about Richard Bailey and his crowd. Howard Blum, Vanity Fair , January 1995

And sometimes one term is used as a genus, or a means for defining the other:

Laplace's popular version of his astronomy, the Système du monde , was famous for introducing what came to be known as the nebular hypothesis , the theory that the solar system was formed by the condensation, through gradual cooling, of the gaseous atmosphere (the nebulae) surrounding the sun. Louis Menand, The Metaphysical Club , 2001 Researchers use this information to support the gateway drug theory — the hypothesis that using one intoxicating substance leads to future use of another. Jordy Byrd, The Pacific Northwest Inlander , 6 May 2015 Fox, the business and economics columnist for Time magazine, tells the story of the professors who enabled those abuses under the banner of the financial theory known as the efficient market hypothesis . Paul Krugman, The New York Times Book Review , 9 Aug. 2009

Incorrect Interpretations of "Theory"

Since this casual use does away with the distinctions upheld by the scientific community, hypothesis and theory are prone to being wrongly interpreted even when they are encountered in scientific contexts—or at least, contexts that allude to scientific study without making the critical distinction that scientists employ when weighing hypotheses and theories.

The most common occurrence is when theory is interpreted—and sometimes even gleefully seized upon—to mean something having less truth value than other scientific principles. (The word law applies to principles so firmly established that they are almost never questioned, such as the law of gravity.)

This mistake is one of projection: since we use theory in general use to mean something lightly speculated, then it's implied that scientists must be talking about the same level of uncertainty when they use theory to refer to their well-tested and reasoned principles.

The distinction has come to the forefront particularly on occasions when the content of science curricula in schools has been challenged—notably, when a school board in Georgia put stickers on textbooks stating that evolution was "a theory, not a fact, regarding the origin of living things." As Kenneth R. Miller, a cell biologist at Brown University, has said , a theory "doesn’t mean a hunch or a guess. A theory is a system of explanations that ties together a whole bunch of facts. It not only explains those facts, but predicts what you ought to find from other observations and experiments.”

While theories are never completely infallible, they form the basis of scientific reasoning because, as Miller said "to the best of our ability, we’ve tested them, and they’ve held up."

More Differences Explained

- Epidemic vs. Pandemic

- Diagnosis vs. Prognosis

- Treatment vs. Cure

Word of the Day

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Games & Quizzes

Commonly Confused

'canceled' or 'cancelled', is it 'home in' or 'hone in', the difference between 'race' and 'ethnicity', homophones, homographs, and homonyms, on 'biweekly' and 'bimonthly', grammar & usage, how to use accents and diacritical marks, 31 useful rhetorical devices, how to use em dashes (—), en dashes (–) , and hyphens (-), every letter is silent, sometimes: a-z list of examples, plural and possessive names: a guide, 7 shakespearean insults to make life more interesting, pilfer: how to play and win, 8 words for lesser-known musical instruments, weird words for autumn time, 10 words from taylor swift songs (merriam's version).

What Is a Hypothesis? (Science)

If...,Then...

Angela Lumsden/Getty Images

- Scientific Method

- Chemical Laws

- Periodic Table

- Projects & Experiments

- Biochemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Medical Chemistry

- Chemistry In Everyday Life

- Famous Chemists

- Activities for Kids

- Abbreviations & Acronyms

- Weather & Climate

- Ph.D., Biomedical Sciences, University of Tennessee at Knoxville

- B.A., Physics and Mathematics, Hastings College

A hypothesis (plural hypotheses) is a proposed explanation for an observation. The definition depends on the subject.

In science, a hypothesis is part of the scientific method. It is a prediction or explanation that is tested by an experiment. Observations and experiments may disprove a scientific hypothesis, but can never entirely prove one.

In the study of logic, a hypothesis is an if-then proposition, typically written in the form, "If X , then Y ."

In common usage, a hypothesis is simply a proposed explanation or prediction, which may or may not be tested.

Writing a Hypothesis

Most scientific hypotheses are proposed in the if-then format because it's easy to design an experiment to see whether or not a cause and effect relationship exists between the independent variable and the dependent variable . The hypothesis is written as a prediction of the outcome of the experiment.

Null Hypothesis and Alternative Hypothesis

Statistically, it's easier to show there is no relationship between two variables than to support their connection. So, scientists often propose the null hypothesis . The null hypothesis assumes changing the independent variable will have no effect on the dependent variable.

In contrast, the alternative hypothesis suggests changing the independent variable will have an effect on the dependent variable. Designing an experiment to test this hypothesis can be trickier because there are many ways to state an alternative hypothesis.

For example, consider a possible relationship between getting a good night's sleep and getting good grades. The null hypothesis might be stated: "The number of hours of sleep students get is unrelated to their grades" or "There is no correlation between hours of sleep and grades."

An experiment to test this hypothesis might involve collecting data, recording average hours of sleep for each student and grades. If a student who gets eight hours of sleep generally does better than students who get four hours of sleep or 10 hours of sleep, the hypothesis might be rejected.

But the alternative hypothesis is harder to propose and test. The most general statement would be: "The amount of sleep students get affects their grades." The hypothesis might also be stated as "If you get more sleep, your grades will improve" or "Students who get nine hours of sleep have better grades than those who get more or less sleep."

In an experiment, you can collect the same data, but the statistical analysis is less likely to give you a high confidence limit.

Usually, a scientist starts out with the null hypothesis. From there, it may be possible to propose and test an alternative hypothesis, to narrow down the relationship between the variables.

Example of a Hypothesis

Examples of a hypothesis include:

- If you drop a rock and a feather, (then) they will fall at the same rate.

- Plants need sunlight in order to live. (if sunlight, then life)

- Eating sugar gives you energy. (if sugar, then energy)

- White, Jay D. Research in Public Administration . Conn., 1998.

- Schick, Theodore, and Lewis Vaughn. How to Think about Weird Things: Critical Thinking for a New Age . McGraw-Hill Higher Education, 2002.

- Scientific Method Flow Chart

- Six Steps of the Scientific Method

- What Are the Elements of a Good Hypothesis?

- What Are Examples of a Hypothesis?

- What Is a Testable Hypothesis?

- Null Hypothesis Examples

- Scientific Hypothesis Examples

- Scientific Variable

- Scientific Method Vocabulary Terms

- Understanding Simple vs Controlled Experiments

- What Is an Experimental Constant?

- What Is a Controlled Experiment?

- What Is the Difference Between a Control Variable and Control Group?

- DRY MIX Experiment Variables Acronym

- Random Error vs. Systematic Error

- The Role of a Controlled Variable in an Experiment

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- When did science begin?

- Where was science invented?

scientific hypothesis

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- National Center for Biotechnology Information - PubMed Central - On the scope of scientific hypotheses

- LiveScience - What is a scientific hypothesis?

- The Royal Society - Open Science - On the scope of scientific hypotheses

scientific hypothesis , an idea that proposes a tentative explanation about a phenomenon or a narrow set of phenomena observed in the natural world. The two primary features of a scientific hypothesis are falsifiability and testability, which are reflected in an “If…then” statement summarizing the idea and in the ability to be supported or refuted through observation and experimentation. The notion of the scientific hypothesis as both falsifiable and testable was advanced in the mid-20th century by Austrian-born British philosopher Karl Popper .

The formulation and testing of a hypothesis is part of the scientific method , the approach scientists use when attempting to understand and test ideas about natural phenomena. The generation of a hypothesis frequently is described as a creative process and is based on existing scientific knowledge, intuition , or experience. Therefore, although scientific hypotheses commonly are described as educated guesses, they actually are more informed than a guess. In addition, scientists generally strive to develop simple hypotheses, since these are easier to test relative to hypotheses that involve many different variables and potential outcomes. Such complex hypotheses may be developed as scientific models ( see scientific modeling ).

Depending on the results of scientific evaluation, a hypothesis typically is either rejected as false or accepted as true. However, because a hypothesis inherently is falsifiable, even hypotheses supported by scientific evidence and accepted as true are susceptible to rejection later, when new evidence has become available. In some instances, rather than rejecting a hypothesis because it has been falsified by new evidence, scientists simply adapt the existing idea to accommodate the new information. In this sense a hypothesis is never incorrect but only incomplete.

The investigation of scientific hypotheses is an important component in the development of scientific theory . Hence, hypotheses differ fundamentally from theories; whereas the former is a specific tentative explanation and serves as the main tool by which scientists gather data, the latter is a broad general explanation that incorporates data from many different scientific investigations undertaken to explore hypotheses.

Countless hypotheses have been developed and tested throughout the history of science . Several examples include the idea that living organisms develop from nonliving matter, which formed the basis of spontaneous generation , a hypothesis that ultimately was disproved (first in 1668, with the experiments of Italian physician Francesco Redi , and later in 1859, with the experiments of French chemist and microbiologist Louis Pasteur ); the concept proposed in the late 19th century that microorganisms cause certain diseases (now known as germ theory ); and the notion that oceanic crust forms along submarine mountain zones and spreads laterally away from them ( seafloor spreading hypothesis ).

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Write a Great Hypothesis

Hypothesis Definition, Format, Examples, and Tips

Verywell / Alex Dos Diaz

- The Scientific Method

Hypothesis Format

Falsifiability of a hypothesis.

- Operationalization

Hypothesis Types

Hypotheses examples.

- Collecting Data

A hypothesis is a tentative statement about the relationship between two or more variables. It is a specific, testable prediction about what you expect to happen in a study. It is a preliminary answer to your question that helps guide the research process.

Consider a study designed to examine the relationship between sleep deprivation and test performance. The hypothesis might be: "This study is designed to assess the hypothesis that sleep-deprived people will perform worse on a test than individuals who are not sleep-deprived."

At a Glance

A hypothesis is crucial to scientific research because it offers a clear direction for what the researchers are looking to find. This allows them to design experiments to test their predictions and add to our scientific knowledge about the world. This article explores how a hypothesis is used in psychology research, how to write a good hypothesis, and the different types of hypotheses you might use.

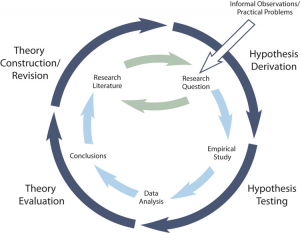

The Hypothesis in the Scientific Method

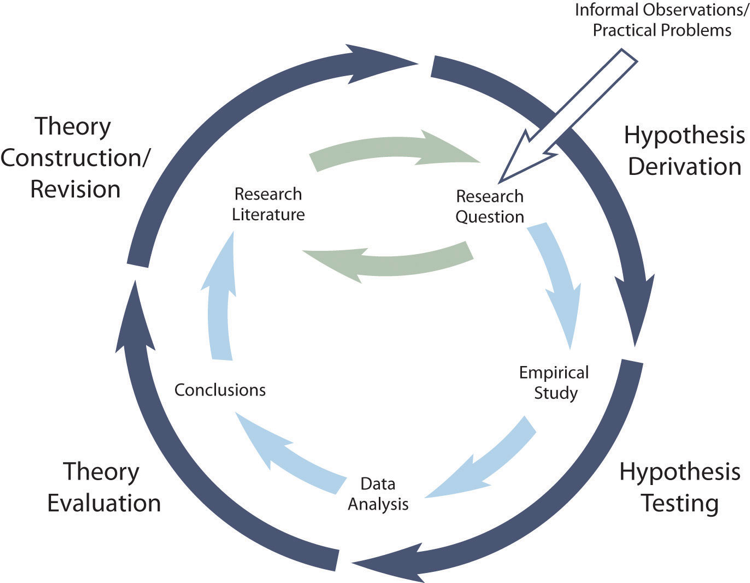

In the scientific method , whether it involves research in psychology, biology, or some other area, a hypothesis represents what the researchers think will happen in an experiment. The scientific method involves the following steps:

- Forming a question

- Performing background research

- Creating a hypothesis

- Designing an experiment

- Collecting data

- Analyzing the results

- Drawing conclusions

- Communicating the results

The hypothesis is a prediction, but it involves more than a guess. Most of the time, the hypothesis begins with a question which is then explored through background research. At this point, researchers then begin to develop a testable hypothesis.

Unless you are creating an exploratory study, your hypothesis should always explain what you expect to happen.

In a study exploring the effects of a particular drug, the hypothesis might be that researchers expect the drug to have some type of effect on the symptoms of a specific illness. In psychology, the hypothesis might focus on how a certain aspect of the environment might influence a particular behavior.

Remember, a hypothesis does not have to be correct. While the hypothesis predicts what the researchers expect to see, the goal of the research is to determine whether this guess is right or wrong. When conducting an experiment, researchers might explore numerous factors to determine which ones might contribute to the ultimate outcome.

In many cases, researchers may find that the results of an experiment do not support the original hypothesis. When writing up these results, the researchers might suggest other options that should be explored in future studies.

In many cases, researchers might draw a hypothesis from a specific theory or build on previous research. For example, prior research has shown that stress can impact the immune system. So a researcher might hypothesize: "People with high-stress levels will be more likely to contract a common cold after being exposed to the virus than people who have low-stress levels."

In other instances, researchers might look at commonly held beliefs or folk wisdom. "Birds of a feather flock together" is one example of folk adage that a psychologist might try to investigate. The researcher might pose a specific hypothesis that "People tend to select romantic partners who are similar to them in interests and educational level."

Elements of a Good Hypothesis

So how do you write a good hypothesis? When trying to come up with a hypothesis for your research or experiments, ask yourself the following questions:

- Is your hypothesis based on your research on a topic?

- Can your hypothesis be tested?

- Does your hypothesis include independent and dependent variables?

Before you come up with a specific hypothesis, spend some time doing background research. Once you have completed a literature review, start thinking about potential questions you still have. Pay attention to the discussion section in the journal articles you read . Many authors will suggest questions that still need to be explored.

How to Formulate a Good Hypothesis

To form a hypothesis, you should take these steps:

- Collect as many observations about a topic or problem as you can.

- Evaluate these observations and look for possible causes of the problem.

- Create a list of possible explanations that you might want to explore.

- After you have developed some possible hypotheses, think of ways that you could confirm or disprove each hypothesis through experimentation. This is known as falsifiability.

In the scientific method , falsifiability is an important part of any valid hypothesis. In order to test a claim scientifically, it must be possible that the claim could be proven false.

Students sometimes confuse the idea of falsifiability with the idea that it means that something is false, which is not the case. What falsifiability means is that if something was false, then it is possible to demonstrate that it is false.

One of the hallmarks of pseudoscience is that it makes claims that cannot be refuted or proven false.

The Importance of Operational Definitions

A variable is a factor or element that can be changed and manipulated in ways that are observable and measurable. However, the researcher must also define how the variable will be manipulated and measured in the study.

Operational definitions are specific definitions for all relevant factors in a study. This process helps make vague or ambiguous concepts detailed and measurable.

For example, a researcher might operationally define the variable " test anxiety " as the results of a self-report measure of anxiety experienced during an exam. A "study habits" variable might be defined by the amount of studying that actually occurs as measured by time.

These precise descriptions are important because many things can be measured in various ways. Clearly defining these variables and how they are measured helps ensure that other researchers can replicate your results.

Replicability

One of the basic principles of any type of scientific research is that the results must be replicable.

Replication means repeating an experiment in the same way to produce the same results. By clearly detailing the specifics of how the variables were measured and manipulated, other researchers can better understand the results and repeat the study if needed.

Some variables are more difficult than others to define. For example, how would you operationally define a variable such as aggression ? For obvious ethical reasons, researchers cannot create a situation in which a person behaves aggressively toward others.

To measure this variable, the researcher must devise a measurement that assesses aggressive behavior without harming others. The researcher might utilize a simulated task to measure aggressiveness in this situation.

Hypothesis Checklist

- Does your hypothesis focus on something that you can actually test?

- Does your hypothesis include both an independent and dependent variable?

- Can you manipulate the variables?

- Can your hypothesis be tested without violating ethical standards?

The hypothesis you use will depend on what you are investigating and hoping to find. Some of the main types of hypotheses that you might use include:

- Simple hypothesis : This type of hypothesis suggests there is a relationship between one independent variable and one dependent variable.

- Complex hypothesis : This type suggests a relationship between three or more variables, such as two independent and dependent variables.

- Null hypothesis : This hypothesis suggests no relationship exists between two or more variables.

- Alternative hypothesis : This hypothesis states the opposite of the null hypothesis.

- Statistical hypothesis : This hypothesis uses statistical analysis to evaluate a representative population sample and then generalizes the findings to the larger group.

- Logical hypothesis : This hypothesis assumes a relationship between variables without collecting data or evidence.

A hypothesis often follows a basic format of "If {this happens} then {this will happen}." One way to structure your hypothesis is to describe what will happen to the dependent variable if you change the independent variable .

The basic format might be: "If {these changes are made to a certain independent variable}, then we will observe {a change in a specific dependent variable}."

A few examples of simple hypotheses:

- "Students who eat breakfast will perform better on a math exam than students who do not eat breakfast."

- "Students who experience test anxiety before an English exam will get lower scores than students who do not experience test anxiety."

- "Motorists who talk on the phone while driving will be more likely to make errors on a driving course than those who do not talk on the phone."

- "Children who receive a new reading intervention will have higher reading scores than students who do not receive the intervention."

Examples of a complex hypothesis include:

- "People with high-sugar diets and sedentary activity levels are more likely to develop depression."

- "Younger people who are regularly exposed to green, outdoor areas have better subjective well-being than older adults who have limited exposure to green spaces."

Examples of a null hypothesis include:

- "There is no difference in anxiety levels between people who take St. John's wort supplements and those who do not."

- "There is no difference in scores on a memory recall task between children and adults."

- "There is no difference in aggression levels between children who play first-person shooter games and those who do not."

Examples of an alternative hypothesis:

- "People who take St. John's wort supplements will have less anxiety than those who do not."

- "Adults will perform better on a memory task than children."

- "Children who play first-person shooter games will show higher levels of aggression than children who do not."

Collecting Data on Your Hypothesis

Once a researcher has formed a testable hypothesis, the next step is to select a research design and start collecting data. The research method depends largely on exactly what they are studying. There are two basic types of research methods: descriptive research and experimental research.

Descriptive Research Methods

Descriptive research such as case studies , naturalistic observations , and surveys are often used when conducting an experiment is difficult or impossible. These methods are best used to describe different aspects of a behavior or psychological phenomenon.

Once a researcher has collected data using descriptive methods, a correlational study can examine how the variables are related. This research method might be used to investigate a hypothesis that is difficult to test experimentally.

Experimental Research Methods

Experimental methods are used to demonstrate causal relationships between variables. In an experiment, the researcher systematically manipulates a variable of interest (known as the independent variable) and measures the effect on another variable (known as the dependent variable).

Unlike correlational studies, which can only be used to determine if there is a relationship between two variables, experimental methods can be used to determine the actual nature of the relationship—whether changes in one variable actually cause another to change.

The hypothesis is a critical part of any scientific exploration. It represents what researchers expect to find in a study or experiment. In situations where the hypothesis is unsupported by the research, the research still has value. Such research helps us better understand how different aspects of the natural world relate to one another. It also helps us develop new hypotheses that can then be tested in the future.

Thompson WH, Skau S. On the scope of scientific hypotheses . R Soc Open Sci . 2023;10(8):230607. doi:10.1098/rsos.230607

Taran S, Adhikari NKJ, Fan E. Falsifiability in medicine: what clinicians can learn from Karl Popper [published correction appears in Intensive Care Med. 2021 Jun 17;:]. Intensive Care Med . 2021;47(9):1054-1056. doi:10.1007/s00134-021-06432-z

Eyler AA. Research Methods for Public Health . 1st ed. Springer Publishing Company; 2020. doi:10.1891/9780826182067.0004

Nosek BA, Errington TM. What is replication ? PLoS Biol . 2020;18(3):e3000691. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3000691

Aggarwal R, Ranganathan P. Study designs: Part 2 - Descriptive studies . Perspect Clin Res . 2019;10(1):34-36. doi:10.4103/picr.PICR_154_18

Nevid J. Psychology: Concepts and Applications. Wadworth, 2013.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Incorporate STEM journalism in your classroom

- Exercise type: Discussion

- Topic: Earth

- Category: Research & Design

How a scientific theory is born

What is a scientific hypothesis?

It's the initial building block in the scientific method.

Hypothesis basics

What makes a hypothesis testable.

- Types of hypotheses

- Hypothesis versus theory

Additional resources

Bibliography.

A scientific hypothesis is a tentative, testable explanation for a phenomenon in the natural world. It's the initial building block in the scientific method . Many describe it as an "educated guess" based on prior knowledge and observation. While this is true, a hypothesis is more informed than a guess. While an "educated guess" suggests a random prediction based on a person's expertise, developing a hypothesis requires active observation and background research.

The basic idea of a hypothesis is that there is no predetermined outcome. For a solution to be termed a scientific hypothesis, it has to be an idea that can be supported or refuted through carefully crafted experimentation or observation. This concept, called falsifiability and testability, was advanced in the mid-20th century by Austrian-British philosopher Karl Popper in his famous book "The Logic of Scientific Discovery" (Routledge, 1959).

A key function of a hypothesis is to derive predictions about the results of future experiments and then perform those experiments to see whether they support the predictions.

A hypothesis is usually written in the form of an if-then statement, which gives a possibility (if) and explains what may happen because of the possibility (then). The statement could also include "may," according to California State University, Bakersfield .

Here are some examples of hypothesis statements:

- If garlic repels fleas, then a dog that is given garlic every day will not get fleas.

- If sugar causes cavities, then people who eat a lot of candy may be more prone to cavities.

- If ultraviolet light can damage the eyes, then maybe this light can cause blindness.

A useful hypothesis should be testable and falsifiable. That means that it should be possible to prove it wrong. A theory that can't be proved wrong is nonscientific, according to Karl Popper's 1963 book " Conjectures and Refutations ."

An example of an untestable statement is, "Dogs are better than cats." That's because the definition of "better" is vague and subjective. However, an untestable statement can be reworded to make it testable. For example, the previous statement could be changed to this: "Owning a dog is associated with higher levels of physical fitness than owning a cat." With this statement, the researcher can take measures of physical fitness from dog and cat owners and compare the two.

Types of scientific hypotheses

In an experiment, researchers generally state their hypotheses in two ways. The null hypothesis predicts that there will be no relationship between the variables tested, or no difference between the experimental groups. The alternative hypothesis predicts the opposite: that there will be a difference between the experimental groups. This is usually the hypothesis scientists are most interested in, according to the University of Miami .

For example, a null hypothesis might state, "There will be no difference in the rate of muscle growth between people who take a protein supplement and people who don't." The alternative hypothesis would state, "There will be a difference in the rate of muscle growth between people who take a protein supplement and people who don't."

If the results of the experiment show a relationship between the variables, then the null hypothesis has been rejected in favor of the alternative hypothesis, according to the book " Research Methods in Psychology " (BCcampus, 2015).

There are other ways to describe an alternative hypothesis. The alternative hypothesis above does not specify a direction of the effect, only that there will be a difference between the two groups. That type of prediction is called a two-tailed hypothesis. If a hypothesis specifies a certain direction — for example, that people who take a protein supplement will gain more muscle than people who don't — it is called a one-tailed hypothesis, according to William M. K. Trochim , a professor of Policy Analysis and Management at Cornell University.

Sometimes, errors take place during an experiment. These errors can happen in one of two ways. A type I error is when the null hypothesis is rejected when it is true. This is also known as a false positive. A type II error occurs when the null hypothesis is not rejected when it is false. This is also known as a false negative, according to the University of California, Berkeley .

A hypothesis can be rejected or modified, but it can never be proved correct 100% of the time. For example, a scientist can form a hypothesis stating that if a certain type of tomato has a gene for red pigment, that type of tomato will be red. During research, the scientist then finds that each tomato of this type is red. Though the findings confirm the hypothesis, there may be a tomato of that type somewhere in the world that isn't red. Thus, the hypothesis is true, but it may not be true 100% of the time.

Scientific theory vs. scientific hypothesis

The best hypotheses are simple. They deal with a relatively narrow set of phenomena. But theories are broader; they generally combine multiple hypotheses into a general explanation for a wide range of phenomena, according to the University of California, Berkeley . For example, a hypothesis might state, "If animals adapt to suit their environments, then birds that live on islands with lots of seeds to eat will have differently shaped beaks than birds that live on islands with lots of insects to eat." After testing many hypotheses like these, Charles Darwin formulated an overarching theory: the theory of evolution by natural selection.

"Theories are the ways that we make sense of what we observe in the natural world," Tanner said. "Theories are structures of ideas that explain and interpret facts."

- Read more about writing a hypothesis, from the American Medical Writers Association.

- Find out why a hypothesis isn't always necessary in science, from The American Biology Teacher.

- Learn about null and alternative hypotheses, from Prof. Essa on YouTube .

Encyclopedia Britannica. Scientific Hypothesis. Jan. 13, 2022. https://www.britannica.com/science/scientific-hypothesis

Karl Popper, "The Logic of Scientific Discovery," Routledge, 1959.

California State University, Bakersfield, "Formatting a testable hypothesis." https://www.csub.edu/~ddodenhoff/Bio100/Bio100sp04/formattingahypothesis.htm

Karl Popper, "Conjectures and Refutations," Routledge, 1963.

Price, P., Jhangiani, R., & Chiang, I., "Research Methods of Psychology — 2nd Canadian Edition," BCcampus, 2015.

University of Miami, "The Scientific Method" http://www.bio.miami.edu/dana/161/evolution/161app1_scimethod.pdf

William M.K. Trochim, "Research Methods Knowledge Base," https://conjointly.com/kb/hypotheses-explained/

University of California, Berkeley, "Multiple Hypothesis Testing and False Discovery Rate" https://www.stat.berkeley.edu/~hhuang/STAT141/Lecture-FDR.pdf

University of California, Berkeley, "Science at multiple levels" https://undsci.berkeley.edu/article/0_0_0/howscienceworks_19

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Experts predicted way more hurricanes this year — here's the weird reason we're 'missing' storms

Deep below the Arctic Ocean, some plants have adapted to photosynthesize in almost near darkness

Watch extremely rare footage of a bigfin squid 'walking' on long, spindly arms deep in the South Pacific

Most Popular

- 2 'The secret to living to 110 was, don't register your death': Ig Nobel winner Saul Justin Newman on the flawed data on extreme aging

- 3 New self-swab HPV test is an alternative to Pap smears. Here's how it works.

- 4 Nuking an asteroid could save Earth from destruction, researchers show in 1st-of-its-kind X-ray experiment

- 5 Experts predicted way more hurricanes this year — here's the weird reason we're 'missing' storms

The Scientific Hypothesis

The Key to Understanding How Science Works

Hypotheses, Theories, Laws (and Models)… What’s the difference?

Untold hours have been spent trying to sort out the differences between these ideas. should we bother.

Ask what the differences between these concepts are and you’re likely to encounter a raft of distinctions; typically with charts and ladders of generality leading from hypotheses to theories and, ultimately, to laws. Countless students have been exposed to and forced to learn how the schemes are set up. Theories are said to be well-tested hypotheses, or maybe whole collections of linked hypotheses, and laws, well, laws are at the top of the heap, the apex of science having enormous reach, quantitative predictive power, and validity. It all seems so clear.

Yet there are many problems with the general scheme. For one thing, it is never quite explained how a hypothesis turns into a theory or law and, consequently, the boundaries are blurry, and definitions tend vary with the speaker. And there is no consistency in usage across fields, I’ll give some examples in a minute. There are branches of science that have few if any theories and no laws – neuroscience comes to mind – though no one doubts that neuroscience is a bona fide science that has discovered great quantities of reliable and useful information and wide-ranging generalizations. At the other extreme, there are sciences that spin out theories at a dizzying pace – psychology, for instance – although the permanence and indeed the veracity of psychological theories are rarely on par with those of physics or chemistry.

Some people will tell you that theories and laws are “more quantitative” than hypotheses, but the most famous theory in biology, the Theory of Evolution, which is based on concepts such as heritability, genetic variability, natural selection, etc. is not as neatly expressible in quantitative terms as is Newton’s Theory of Gravity, for example. And what do we make of the fact that Newton’s “Law of Gravity” was superceded by Einstein’s “General Theory (not Law) of Relativity?”

What about the idea that a hypothesis is a low-level explanation that somehow transmogrifies into a theory when conditions are right? Even this simple rule is not adhered to. Take geology (or “geoscience” nowadays): We have the Alvarez Hypothesis about how an asteroid slamming into the earth caused the extinction of dinosaurs and other life-forms ~66 million years ago. The Alvarez Hypothesis explains, often in quantitative detail, many important phenomena and makes far-reaching predictions, most remarkably of a crater, which was eventually found in the Yucatan peninsula, that has the right age and size to be the site of an extinction-causing asteroid impact. The Alvarez Hypothesis has been rigorously tested many times since it was proposed, without having been promoted to a theory.

But perhaps the Alvarez Hypothesis is still thought to be a tentative explanation, not yet worthy of a more exalted status? It seems that the same can’t be said about the idea that the earth’s crust consists of 12 or so rigid “plates” of solid material that drift around very slowly and create geological phenomena, such as mountain ranges and earth-quakes, when they crash into each other. This is called either the “Plate Tectonics Hypothesis” or “Plate Tectonics Theory” by different authors. Same data, same interpretations, same significance, different names.

And for anyone trying to make sense of the hypothesis-theory-law progression, it must be highly confusing to learn that the crowning achievement of modern physics – itself the “queen of the sciences” – is a complex, extraordinarily precise, quantitative structure is known as the Standard Model of Particle Physics, not the Standard Theory, or the Standard Law! The Standard Model incorporates three of the four major forces of nature, describes many subatomic particles, and has successfully predicted numerous subtle properties of subatomic particles. Does this mean that “model” now implies a large, well-worked out and self-consistent body of scientific knowledge? Not at all; in fact, “model” and “hypothesis” are used interchangeably at the simplest levels of experimental investigation in biology, neuroscience, etc., so definition-wise, we’re back to the beginning.

The reason that the Standard Model is a model and not a theory seems basically to be the same as the reason that the Alvarez Hypothesis is a hypothesis and not a theory or that Evolution is a theory and not a law: essentially it is a matter of convention, tradition, or convenience. The designations, we can infer, are primarily names that lack exact substantive, generally agreed-on definitions.

So, rather than worrying about any profound distinctions between hypotheses, theories, laws (and models) it might be more helpful to look at the properties that they have in common:

1. They are all “conjectural” which, for the moment, means that they are inventions of the human mind.

2. They make specific predictions that are empirically testable, in principle.

3. They are falsifiable – if their predictions are false, they are false – though not provable, by experiment or observation.

4. As a consequence of point 3., hypotheses, theories, and laws are all provisional; they may be replaced as further information becomes available.

“Hypothesis,” it seems to me, is the fundamental unit, the building block, of scientific thinking. It is the term that is most consistently used by all sciences; it is more basic than any theory; it carries the least baggage, is the least susceptible to multiple interpretations and, accordingly, is the most likely to communicate effectively. These advantages are relative of course; as I’ll get into elsewhere, even “hypothesis” is the subject of misinterpretation. In any case, its simplicity and clarity are why this website is devoted to the Scientific Hypothesis and not the others.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Hypothesis vs. Theory

A hypothesis is either a suggested explanation for an observable phenomenon, or a reasoned prediction of a possible causal correlation among multiple phenomena. In science , a theory is a tested, well-substantiated, unifying explanation for a set of verified, proven factors. A theory is always backed by evidence; a hypothesis is only a suggested possible outcome, and is testable and falsifiable.

Comparison chart

| Hypothesis | Theory | |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | A suggested explanation for an observable phenomenon or prediction of a possible causal correlation among multiple phenomena. | In , a theory is a well-substantiated, unifying explanation for a set of verified, proven hypotheses. |

| Based on | Suggestion, possibility, projection or prediction, but the result is uncertain. | Evidence, verification, repeated testing, wide scientific consensus |

| Testable | Yes | Yes |

| Falsifiable | Yes | Yes |

| Is well-substantiated? | No | Yes |

| Is well-tested? | No | Yes |

| Data | Usually based on very limited data | Based on a very wide set of data tested under various circumstances. |

| Instance | Specific: Hypothesis is usually based on a very specific observation and is limited to that instance. | General: A theory is the establishment of a general principle through multiple tests and experiments, and this principle may apply to various specific instances. |

| Purpose | To present an uncertain possibility that can be explored further through experiments and observations. | To explain why a large set of observations are consistently made. |

Examples of Theory and Hypothesis

Theory: Einstein's theory of relativity is a theory because it has been tested and verified innumerable times, with results consistently verifying Einstein's conclusion. However, simply because Einstein's conclusion has become a theory does not mean testing of this theory has stopped; all science is ongoing. See also the Big Bang theory , germ theory , and climate change .

Hypothesis: One might think that a prisoner who learns a work skill while in prison will be less likely to commit a crime when released. This is a hypothesis, an "educated guess." The scientific method can be used to test this hypothesis, to either prove it is false or prove that it warrants further study. (Note: Simply because a hypothesis is not found to be false does not mean it is true all or even most of the time. If it is consistently true after considerable time and research, it may be on its way to becoming a theory.)

This video further explains the difference between a theory and a hypothesis:

Common Misconception

People often tend to say "theory" when what they're actually talking about is a hypothesis. For instance, "Migraines are caused by drinking coffee after 2 p.m. — well, it's just a theory, not a rule."

This is actually a logically reasoned proposal based on an observation — say 2 instances of drinking coffee after 2 p.m. caused a migraine — but even if this were true, the migraine could have actually been caused by some other factors.

Because this observation is merely a reasoned possibility, it is testable and can be falsified — which makes it a hypothesis, not a theory.

- What is a Scientific Hypothesis? - LiveScience

- Wikipedia:Scientific theory

Related Comparisons

Share this comparison via:

If you read this far, you should follow us:

"Hypothesis vs Theory." Diffen.com. Diffen LLC, n.d. Web. 23 Sep 2024. < >

Comments: Hypothesis vs Theory

Anonymous comments (2).

October 11, 2013, 1:11pm "In science, a theory is a well-substantiated, unifying explanation for a set of verified, proven hypotheses." But there's no such thing as "proven hypotheses". Hypotheses can be tested/falsified, they can't be "proven". That's just not how science works. Logical deductions based on axioms can be proven, but not scientific hypotheses. On top of that I find it somewhat strange to claim that a theory doesn't have to be testable, if it's built up from hypotheses, which DO have to be testable... — 80.✗.✗.139

May 6, 2014, 11:45pm "Evolution is a theory, not a fact, regarding the origin of living things." this statement is poorly formed because it implies that a thing is a theory until it gets proven and then it is somehow promoted to fact. this is just a misunderstanding of what the words mean, and of how science progresses generally. to say that a theory is inherently dubious because "it isn't a fact" is pretty much a meaningless statement. no expression which qualified as a mere fact could do a very good job of explaining the complicated process by which species have arisen on Earth over the last billion years. in fact, if you claimed that you could come up with such a single fact, now THAT would be dubious! everything we observe in nature supports the theory of evolution, and nothing we observe contradicts it. when you can say this about a theory, it's a pretty fair bet that the theory is correct. — 71.✗.✗.151

- Accuracy vs Precision

- Deductive vs Inductive

- Subjective vs Objective

- Subconscious vs Unconscious mind

- Qualitative vs Quantitative

- Creationism vs Evolution

Edit or create new comparisons in your area of expertise.

Stay connected

© All rights reserved.

Theories, Hypotheses, and Laws: Definitions, examples, and their roles in science

by Anthony Carpi, Ph.D., Anne E. Egger, Ph.D.

Listen to this reading

Did you know that the idea of evolution had been part of Western thought for more than 2,000 years before Charles Darwin was born? Like many theories, the theory of evolution was the result of the work of many different scientists working in different disciplines over a period of time.

A scientific theory is an explanation inferred from multiple lines of evidence for some broad aspect of the natural world and is logical, testable, and predictive.

As new evidence comes to light, or new interpretations of existing data are proposed, theories may be revised and even change; however, they are not tenuous or speculative.

A scientific hypothesis is an inferred explanation of an observation or research finding; while more exploratory in nature than a theory, it is based on existing scientific knowledge.

A scientific law is an expression of a mathematical or descriptive relationship observed in nature.

Imagine yourself shopping in a grocery store with a good friend who happens to be a chemist. Struggling to choose between the many different types of tomatoes in front of you, you pick one up, turn to your friend, and ask her if she thinks the tomato is organic . Your friend simply chuckles and replies, "Of course it's organic!" without even looking at how the fruit was grown. Why the amused reaction? Your friend is highlighting a simple difference in vocabulary. To a chemist, the term organic refers to any compound in which hydrogen is bonded to carbon. Tomatoes (like all plants) are abundant in organic compounds – thus your friend's laughter. In modern agriculture, however, organic has come to mean food items grown or raised without the use of chemical fertilizers, pesticides, or other additives.

So who is correct? You both are. Both uses of the word are correct, though they mean different things in different contexts. There are, of course, lots of words that have more than one meaning (like bat , for example), but multiple meanings can be especially confusing when two meanings convey very different ideas and are specific to one field of study.

- Scientific theories

The term theory also has two meanings, and this double meaning often leads to confusion. In common language, the term theory generally refers to speculation or a hunch or guess. You might have a theory about why your favorite sports team isn't playing well, or who ate the last cookie from the cookie jar. But these theories do not fit the scientific use of the term. In science, a theory is a well-substantiated and comprehensive set of ideas that explains a phenomenon in nature. A scientific theory is based on large amounts of data and observations that have been collected over time. Scientific theories can be tested and refined by additional research , and they allow scientists to make predictions. Though you may be correct in your hunch, your cookie jar conjecture doesn't fit this more rigorous definition.

All scientific disciplines have well-established, fundamental theories . For example, atomic theory describes the nature of matter and is supported by multiple lines of evidence from the way substances behave and react in the world around us (see our series on Atomic Theory ). Plate tectonic theory describes the large scale movement of the outer layer of the Earth and is supported by evidence from studies about earthquakes , magnetic properties of the rocks that make up the seafloor , and the distribution of volcanoes on Earth (see our series on Plate Tectonic Theory ). The theory of evolution by natural selection , which describes the mechanism by which inherited traits that affect survivability or reproductive success can cause changes in living organisms over generations , is supported by extensive studies of DNA , fossils , and other types of scientific evidence (see our Charles Darwin series for more information). Each of these major theories guides and informs modern research in those fields, integrating a broad, comprehensive set of ideas.

So how are these fundamental theories developed, and why are they considered so well supported? Let's take a closer look at some of the data and research supporting the theory of natural selection to better see how a theory develops.

Comprehension Checkpoint

- The development of a scientific theory: Evolution and natural selection

The theory of evolution by natural selection is sometimes maligned as Charles Darwin 's speculation on the origin of modern life forms. However, evolutionary theory is not speculation. While Darwin is rightly credited with first articulating the theory of natural selection, his ideas built on more than a century of scientific research that came before him, and are supported by over a century and a half of research since.

- The Fixity Notion: Linnaeus

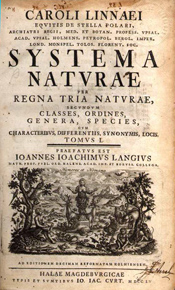

Figure 1: Cover of the 1760 edition of Systema Naturae .

Research about the origins and diversity of life proliferated in the 18th and 19th centuries. Carolus Linnaeus , a Swedish botanist and the father of modern taxonomy (see our module Taxonomy I for more information), was a devout Christian who believed in the concept of Fixity of Species , an idea based on the biblical story of creation. The Fixity of Species concept said that each species is based on an ideal form that has not changed over time. In the early stages of his career, Linnaeus traveled extensively and collected data on the structural similarities and differences between different species of plants. Noting that some very different plants had similar structures, he began to piece together his landmark work, Systema Naturae, in 1735 (Figure 1). In Systema , Linnaeus classified organisms into related groups based on similarities in their physical features. He developed a hierarchical classification system , even drawing relationships between seemingly disparate species (for example, humans, orangutans, and chimpanzees) based on the physical similarities that he observed between these organisms. Linnaeus did not explicitly discuss change in organisms or propose a reason for his hierarchy, but by grouping organisms based on physical characteristics, he suggested that species are related, unintentionally challenging the Fixity notion that each species is created in a unique, ideal form.

- The age of Earth: Leclerc and Hutton

Also in the early 1700s, Georges-Louis Leclerc, a French naturalist, and James Hutton , a Scottish geologist, began to develop new ideas about the age of the Earth. At the time, many people thought of the Earth as 6,000 years old, based on a strict interpretation of the events detailed in the Christian Old Testament by the influential Scottish Archbishop Ussher. By observing other planets and comets in the solar system , Leclerc hypothesized that Earth began as a hot, fiery ball of molten rock, mostly consisting of iron. Using the cooling rate of iron, Leclerc calculated that Earth must therefore be at least 70,000 years old in order to have reached its present temperature.

Hutton approached the same topic from a different perspective, gathering observations of the relationships between different rock formations and the rates of modern geological processes near his home in Scotland. He recognized that the relatively slow processes of erosion and sedimentation could not create all of the exposed rock layers in only a few thousand years (see our module The Rock Cycle ). Based on his extensive collection of data (just one of his many publications ran to 2,138 pages), Hutton suggested that the Earth was far older than human history – hundreds of millions of years old.

While we now know that both Leclerc and Hutton significantly underestimated the age of the Earth (by about 4 billion years), their work shattered long-held beliefs and opened a window into research on how life can change over these very long timescales.

- Fossil studies lead to the development of a theory of evolution: Cuvier

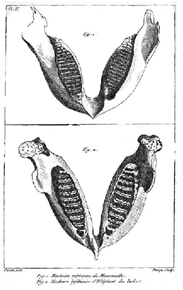

Figure 2: Illustration of an Indian elephant jaw and a mammoth jaw from Cuvier's 1796 paper.

With the age of Earth now extended by Leclerc and Hutton, more researchers began to turn their attention to studying past life. Fossils are the main way to study past life forms, and several key studies on fossils helped in the development of a theory of evolution . In 1795, Georges Cuvier began to work at the National Museum in Paris as a naturalist and anatomist. Through his work, Cuvier became interested in fossils found near Paris, which some claimed were the remains of the elephants that Hannibal rode over the Alps when he invaded Rome in 218 BCE . In studying both the fossils and living species , Cuvier documented different patterns in the dental structure and number of teeth between the fossils and modern elephants (Figure 2) (Horner, 1843). Based on these data , Cuvier hypothesized that the fossil remains were not left by Hannibal, but were from a distinct species of animal that once roamed through Europe and had gone extinct thousands of years earlier: the mammoth. The concept of species extinction had been discussed by a few individuals before Cuvier, but it was in direct opposition to the Fixity of Species concept – if every organism were based on a perfectly adapted, ideal form, how could any cease to exist? That would suggest it was no longer ideal.

While his work provided critical evidence of extinction , a key component of evolution , Cuvier was highly critical of the idea that species could change over time. As a result of his extensive studies of animal anatomy, Cuvier had developed a holistic view of organisms , stating that the

number, direction, and shape of the bones that compose each part of an animal's body are always in a necessary relation to all the other parts, in such a way that ... one can infer the whole from any one of them ...

In other words, Cuvier viewed each part of an organism as a unique, essential component of the whole organism. If one part were to change, he believed, the organism could not survive. His skepticism about the ability of organisms to change led him to criticize the whole idea of evolution , and his prominence in France as a scientist played a large role in discouraging the acceptance of the idea in the scientific community.

- Studies of invertebrates support a theory of change in species: Lamarck

Jean Baptiste Lamarck, a contemporary of Cuvier's at the National Museum in Paris, studied invertebrates like insects and worms. As Lamarck worked through the museum's large collection of invertebrates, he was impressed by the number and variety of organisms . He became convinced that organisms could, in fact, change through time, stating that

... time and favorable conditions are the two principal means which nature has employed in giving existence to all her productions. We know that for her time has no limit, and that consequently she always has it at her disposal.

This was a radical departure from both the fixity concept and Cuvier's ideas, and it built on the long timescale that geologists had recently established. Lamarck proposed that changes that occurred during an organism 's lifetime could be passed on to their offspring, suggesting, for example, that a body builder's muscles would be inherited by their children.

As it turned out, the mechanism by which Lamarck proposed that organisms change over time was wrong, and he is now often referred to disparagingly for his "inheritance of acquired characteristics" idea. Yet despite the fact that some of his ideas were discredited, Lamarck established a support for evolutionary theory that others would build on and improve.

- Rock layers as evidence for evolution: Smith

In the early 1800s, a British geologist and canal surveyor named William Smith added another component to the accumulating evidence for evolution . Smith observed that rock layers exposed in different parts of England bore similarities to one another: These layers (or strata) were arranged in a predictable order, and each layer contained distinct groups of fossils . From this series of observations , he developed a hypothesis that specific groups of animals followed one another in a definite sequence through Earth's history, and this sequence could be seen in the rock layers. Smith's hypothesis was based on his knowledge of geological principles , including the Law of Superposition.

The Law of Superposition states that sediments are deposited in a time sequence, with the oldest sediments deposited first, or at the bottom, and newer layers deposited on top. The concept was first expressed by the Persian scientist Avicenna in the 11th century, but was popularized by the Danish scientist Nicolas Steno in the 17th century. Note that the law does not state how sediments are deposited; it simply describes the relationship between the ages of deposited sediments.

Figure 3: Engraving from William Smith's 1815 monograph on identifying strata by fossils.

Smith backed up his hypothesis with extensive drawings of fossils uncovered during his research (Figure 3), thus allowing other scientists to confirm or dispute his findings. His hypothesis has, in fact, been confirmed by many other scientists and has come to be referred to as the Law of Faunal Succession. His work was critical to the formation of evolutionary theory as it not only confirmed Cuvier's work that organisms have gone extinct , but it also showed that the appearance of life does not date to the birth of the planet. Instead, the fossil record preserves a timeline of the appearance and disappearance of different organisms in the past, and in doing so offers evidence for change in organisms over time.

- The theory of evolution by natural selection: Darwin and Wallace

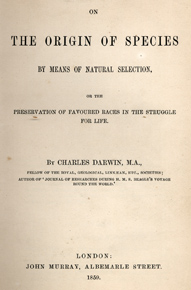

It was into this world that Charles Darwin entered: Linnaeus had developed a taxonomy of organisms based on their physical relationships, Leclerc and Hutton demonstrated that there was sufficient time in Earth's history for organisms to change, Cuvier showed that species of organisms have gone extinct , Lamarck proposed that organisms change over time, and Smith established a timeline of the appearance and disappearance of different organisms in the geological record .

Figure 4: Title page of the 1859 Murray edition of the Origin of Species by Charles Darwin.

Charles Darwin collected data during his work as a naturalist on the HMS Beagle starting in 1831. He took extensive notes on the geology of the places he visited; he made a major find of fossils of extinct animals in Patagonia and identified an extinct giant ground sloth named Megatherium . He experienced an earthquake in Chile that stranded beds of living mussels above water, where they would be preserved for years to come.

Perhaps most famously, he conducted extensive studies of animals on the Galápagos Islands, noting subtle differences in species of mockingbird, tortoise, and finch that were isolated on different islands with different environmental conditions. These subtle differences made the animals highly adapted to their environments .

This broad spectrum of data led Darwin to propose an idea about how organisms change "by means of natural selection" (Figure 4). But this idea was not based only on his work, it was also based on the accumulation of evidence and ideas of many others before him. Because his proposal encompassed and explained many different lines of evidence and previous work, they formed the basis of a new and robust scientific theory regarding change in organisms – the theory of evolution by natural selection .

Darwin's ideas were grounded in evidence and data so compelling that if he had not conceived them, someone else would have. In fact, someone else did. Between 1858 and 1859, Alfred Russel Wallace , a British naturalist, wrote a series of letters to Darwin that independently proposed natural selection as the means for evolutionary change. The letters were presented to the Linnean Society of London, a prominent scientific society at the time (see our module on Scientific Institutions and Societies ). This long chain of research highlights that theories are not just the work of one individual. At the same time, however, it often takes the insight and creativity of individuals to put together all of the pieces and propose a new theory . Both Darwin and Wallace were experienced naturalists who were familiar with the work of others. While all of the work leading up to 1830 contributed to the theory of evolution , Darwin's and Wallace's theory changed the way that future research was focused by presenting a comprehensive, well-substantiated set of ideas, thus becoming a fundamental theory of biological research.

- Expanding, testing, and refining scientific theories

- Genetics and evolution: Mendel and Dobzhansky

Since Darwin and Wallace first published their ideas, extensive research has tested and expanded the theory of evolution by natural selection . Darwin had no concept of genes or DNA or the mechanism by which characteristics were inherited within a species . A contemporary of Darwin's, the Austrian monk Gregor Mendel , first presented his own landmark study, Experiments in Plant Hybridization, in 1865 in which he provided the basic patterns of genetic inheritance , describing which characteristics (and evolutionary changes) can be passed on in organisms (see our Genetics I module for more information). Still, it wasn't until much later that a "gene" was defined as the heritable unit.

In 1937, the Ukrainian born geneticist Theodosius Dobzhansky published Genetics and the Origin of Species , a seminal work in which he described genes themselves and demonstrated that it is through mutations in genes that change occurs. The work defined evolution as "a change in the frequency of an allele within a gene pool" ( Dobzhansky, 1982 ). These studies and others in the field of genetics have added to Darwin's work, expanding the scope of the theory .

- Evolution under a microscope: Lenski

More recently, Dr. Richard Lenski, a scientist at Michigan State University, isolated a single Escherichia coli bacterium in 1989 as the first step of the longest running experimental test of evolutionary theory to date – a true test meant to replicate evolution and natural selection in the lab.

After the single microbe had multiplied, Lenski isolated the offspring into 12 different strains , each in their own glucose-supplied culture, predicting that the genetic make-up of each strain would change over time to become more adapted to their specific culture as predicted by evolutionary theory . These 12 lines have been nurtured for over 40,000 bacterial generations (luckily bacterial generations are much shorter than human generations) and exposed to different selective pressures such as heat , cold, antibiotics, and infection with other microorganisms. Lenski and colleagues have studied dozens of aspects of evolutionary theory with these genetically isolated populations . In 1999, they published a paper that demonstrated that random genetic mutations were common within the populations and highly diverse across different individual bacteria . However, "pivotal" mutations that are associated with beneficial changes in the group are shared by all descendants in a population and are much rarer than random mutations, as predicted by the theory of evolution by natural selection (Papadopoulos et al., 1999).

- Punctuated equilibrium: Gould and Eldredge

While established scientific theories like evolution have a wealth of research and evidence supporting them, this does not mean that they cannot be refined as new information or new perspectives on existing data become available. For example, in 1972, biologist Stephen Jay Gould and paleontologist Niles Eldredge took a fresh look at the existing data regarding the timing by which evolutionary change takes place. Gould and Eldredge did not set out to challenge the theory of evolution; rather they used it as a guiding principle and asked more specific questions to add detail and nuance to the theory. This is true of all theories in science: they provide a framework for additional research. At the time, many biologists viewed evolution as occurring gradually, causing small incremental changes in organisms at a relatively steady rate. The idea is referred to as phyletic gradualism , and is rooted in the geological concept of uniformitarianism . After reexamining the available data, Gould and Eldredge came to a different explanation, suggesting that evolution consists of long periods of stability that are punctuated by occasional instances of dramatic change – a process they called punctuated equilibrium .

Like Darwin before them, their proposal is rooted in evidence and research on evolutionary change, and has been supported by multiple lines of evidence. In fact, punctuated equilibrium is now considered its own theory in evolutionary biology. Punctuated equilibrium is not as broad of a theory as natural selection . In science, some theories are broad and overarching of many concepts, such as the theory of evolution by natural selection; others focus on concepts at a smaller, or more targeted, scale such as punctuated equilibrium. And punctuated equilibrium does not challenge or weaken the concept of natural selection; rather, it represents a change in our understanding of the timing by which change occurs in organisms , and a theory within a theory. The theory of evolution by natural selection now includes both gradualism and punctuated equilibrium to describe the rate at which change proceeds.

- Hypotheses and laws: Other scientific concepts

One of the challenges in understanding scientific terms like theory is that there is not a precise definition even within the scientific community. Some scientists debate over whether certain proposals merit designation as a hypothesis or theory , and others mistakenly use the terms interchangeably. But there are differences in these terms. A hypothesis is a proposed explanation for an observable phenomenon. Hypotheses , just like theories , are based on observations from research . For example, LeClerc did not hypothesize that Earth had cooled from a molten ball of iron as a random guess; rather, he developed this hypothesis based on his observations of information from meteorites.

A scientist often proposes a hypothesis before research confirms it as a way of predicting the outcome of study to help better define the parameters of the research. LeClerc's hypothesis allowed him to use known parameters (the cooling rate of iron) to do additional work. A key component of a formal scientific hypothesis is that it is testable and falsifiable. For example, when Richard Lenski first isolated his 12 strains of bacteria , he likely hypothesized that random mutations would cause differences to appear within a period of time in the different strains of bacteria. But when a hypothesis is generated in science, a scientist will also make an alternative hypothesis , an explanation that explains a study if the data do not support the original hypothesis. If the different strains of bacteria in Lenski's work did not diverge over the indicated period of time, perhaps the rate of mutation was slower than first thought.

So you might ask, if theories are so well supported, do they eventually become laws? The answer is no – not because they aren't well-supported, but because theories and laws are two very different things. Laws describe phenomena, often mathematically. Theories, however, explain phenomena. For example, in 1687 Isaac Newton proposed a Theory of Gravitation, describing gravity as a force of attraction between two objects. As part of this theory, Newton developed a Law of Universal Gravitation that explains how this force operates. This law states that the force of gravity between two objects is inversely proportional to the square of the distance between those objects. Newton 's Law does not explain why this is true, but it describes how gravity functions (see our Gravity: Newtonian Relationships module for more detail). In 1916, Albert Einstein developed his theory of general relativity to explain the mechanism by which gravity has its effect. Einstein's work challenges Newton's theory, and has been found after extensive testing and research to more accurately describe the phenomenon of gravity. While Einstein's work has replaced Newton's as the dominant explanation of gravity in modern science, Newton's Law of Universal Gravitation is still used as it reasonably (and more simply) describes the force of gravity under many conditions. Similarly, the Law of Faunal Succession developed by William Smith does not explain why organisms follow each other in distinct, predictable ways in the rock layers, but it accurately describes the phenomenon.

Theories, hypotheses , and laws drive scientific progress

Theories, hypotheses , and laws are not simply important components of science, they drive scientific progress. For example, evolutionary biology now stands as a distinct field of science that focuses on the origins and descent of species . Geologists now rely on plate tectonics as a conceptual model and guiding theory when they are studying processes at work in Earth's crust . And physicists refer to atomic theory when they are predicting the existence of subatomic particles yet to be discovered. This does not mean that science is "finished," or that all of the important theories have been discovered already. Like evolution , progress in science happens both gradually and in short, dramatic bursts. Both types of progress are critical for creating a robust knowledge base with data as the foundation and scientific theories giving structure to that knowledge.

Table of Contents

- Theories, hypotheses, and laws drive scientific progress

Activate glossary term highlighting to easily identify key terms within the module. Once highlighted, you can click on these terms to view their definitions.

Activate NGSS annotations to easily identify NGSS standards within the module. Once highlighted, you can click on them to view these standards.

- Privacy Policy

Home » What is a Hypothesis – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

What is a Hypothesis – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Definition:

Hypothesis is an educated guess or proposed explanation for a phenomenon, based on some initial observations or data. It is a tentative statement that can be tested and potentially proven or disproven through further investigation and experimentation.

Hypothesis is often used in scientific research to guide the design of experiments and the collection and analysis of data. It is an essential element of the scientific method, as it allows researchers to make predictions about the outcome of their experiments and to test those predictions to determine their accuracy.

Types of Hypothesis

Types of Hypothesis are as follows:

Research Hypothesis

A research hypothesis is a statement that predicts a relationship between variables. It is usually formulated as a specific statement that can be tested through research, and it is often used in scientific research to guide the design of experiments.

Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis is a statement that assumes there is no significant difference or relationship between variables. It is often used as a starting point for testing the research hypothesis, and if the results of the study reject the null hypothesis, it suggests that there is a significant difference or relationship between variables.

Alternative Hypothesis