Essay on Smoking

500 words essay on smoking.

One of the most common problems we are facing in today’s world which is killing people is smoking. A lot of people pick up this habit because of stress , personal issues and more. In fact, some even begin showing it off. When someone smokes a cigarette, they not only hurt themselves but everyone around them. It has many ill-effects on the human body which we will go through in the essay on smoking.

Ill-Effects of Smoking

Tobacco can have a disastrous impact on our health. Nonetheless, people consume it daily for a long period of time till it’s too late. Nearly one billion people in the whole world smoke. It is a shocking figure as that 1 billion puts millions of people at risk along with themselves.

Cigarettes have a major impact on the lungs. Around a third of all cancer cases happen due to smoking. For instance, it can affect breathing and causes shortness of breath and coughing. Further, it also increases the risk of respiratory tract infection which ultimately reduces the quality of life.

In addition to these serious health consequences, smoking impacts the well-being of a person as well. It alters the sense of smell and taste. Further, it also reduces the ability to perform physical exercises.

It also hampers your physical appearances like giving yellow teeth and aged skin. You also get a greater risk of depression or anxiety . Smoking also affects our relationship with our family, friends and colleagues.

Most importantly, it is also an expensive habit. In other words, it entails heavy financial costs. Even though some people don’t have money to get by, they waste it on cigarettes because of their addiction.

How to Quit Smoking?

There are many ways through which one can quit smoking. The first one is preparing for the day when you will quit. It is not easy to quit a habit abruptly, so set a date to give yourself time to prepare mentally.

Further, you can also use NRTs for your nicotine dependence. They can reduce your craving and withdrawal symptoms. NRTs like skin patches, chewing gums, lozenges, nasal spray and inhalers can help greatly.

Moreover, you can also consider non-nicotine medications. They require a prescription so it is essential to talk to your doctor to get access to it. Most importantly, seek behavioural support. To tackle your dependence on nicotine, it is essential to get counselling services, self-materials or more to get through this phase.

One can also try alternative therapies if they want to try them. There is no harm in trying as long as you are determined to quit smoking. For instance, filters, smoking deterrents, e-cigarettes, acupuncture, cold laser therapy, yoga and more can work for some people.

Always remember that you cannot quit smoking instantly as it will be bad for you as well. Try cutting down on it and then slowly and steadily give it up altogether.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Conclusion of the Essay on Smoking

Thus, if anyone is a slave to cigarettes, it is essential for them to understand that it is never too late to stop smoking. With the help and a good action plan, anyone can quit it for good. Moreover, the benefits will be evident within a few days of quitting.

FAQ of Essay on Smoking

Question 1: What are the effects of smoking?

Answer 1: Smoking has major effects like cancer, heart disease, stroke, lung diseases, diabetes, and more. It also increases the risk for tuberculosis, certain eye diseases, and problems with the immune system .

Question 2: Why should we avoid smoking?

Answer 2: We must avoid smoking as it can lengthen your life expectancy. Moreover, by not smoking, you decrease your risk of disease which includes lung cancer, throat cancer, heart disease, high blood pressure, and more.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

Essay on No Smoking

Students are often asked to write an essay on No Smoking in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on No Smoking

What is no smoking.

No Smoking means not using cigarettes or other tobacco products. It’s a choice to stay away from smoke that harms our bodies. When we say No Smoking, we protect our health and the air around us.

Why is Smoking Bad?

Smoking is bad because it can make you very sick. It hurts our lungs and heart. People who smoke can get diseases like cancer. It’s also expensive and makes your clothes and breath smell bad.

Benefits of Not Smoking

Not smoking keeps you healthy and full of energy. Your body feels better, and you can breathe easier. It saves money and keeps your teeth white. Plus, you set a good example for others.

Helping Others Quit

If someone you know smokes, you can help them quit. Tell them about the good things that come from not smoking. Be supportive and kind. They might need a friend to help them stop.

250 Words Essay on No Smoking

Smoking is bad for health. It can cause diseases like cancer, heart problems, and breathing issues. The smoke from cigarettes has chemicals that are dangerous. When people breathe in this smoke, it can make them sick, even if they are not the ones smoking.

Not smoking has many good points. People who do not smoke have better health. They can breathe easier, have more energy, and are less likely to get sick. Also, they save money because cigarettes are expensive.

Helping Smokers Quit

Quitting smoking is not easy, but it’s important. There are many ways to help smokers stop. They can use patches, gum, or medicine. Support from family and friends can also make a big difference.

No Smoking is important for everyone’s health. It keeps our air clean and our bodies healthy. By saying no to smoking, we can all live better and longer lives. Let’s encourage everyone to stop smoking and help those who are trying to quit. This way, we make our world a safer place for all.

500 Words Essay on No Smoking

No Smoking means not using cigarettes, pipes, or any other tool that burns tobacco and lets people inhale its smoke. This idea is important for keeping our bodies healthy and protecting the air everyone breathes. The smoke from cigarettes is not only bad for the person smoking but also for those around them, known as secondhand smoke.

Why People Start Smoking

Health risks of smoking.

Smoking is harmful and can cause a lot of health problems. It can damage the heart, lungs, and other parts of the body. Smokers can get sick with diseases like cancer, especially in the lungs, throat, and mouth. It also makes it hard to breathe and can ruin teeth, making them yellow and causing bad breath. For kids, it’s crucial to understand that starting to smoke can lead to a lifetime of health issues.

Choosing not to smoke has many good points. People who don’t smoke have better health, live longer, and have more energy for fun activities. They also save a lot of money because cigarettes are expensive. Not smoking means clothes and hair won’t smell bad, and it keeps teeth whiter. Plus, it sets a good example for friends and family.

How to Say No to Smoking

If someone knows a person who smokes, they can help them quit. They can tell them about the health risks and how much better life can be without cigarettes. It’s important to be supportive and patient because quitting is a big challenge. There are also many programs and products designed to help smokers give up the habit.

No Smoking is a choice that leads to a healthier life, not just for the person who decides not to smoke, but also for those around them. By understanding why people start, the risks involved, and the benefits of living smoke-free, it’s easier to say no to smoking. Encouraging others to quit and supporting them through the process can make a big difference in their lives and the health of the community. Remember, it’s never too late to stop smoking or to choose not to start at all.

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Importance of Quitting Smoking Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Smoking is a practice which involves the burning of a substance, for instance tobacco or cannabis, and later the smoke that emanates from it is inhaled. When referring to smoking, many people refer to tobacco smoking or cigarette smoking. The most widely used substance for smoking is tobacco, which is manufactured as cigarettes or hand-rolled tobacco. Smoking is an addictive habit and most smokers would attest that they wish they were able to stop the habit.

As much as it may seem to be a comfortable habit, smoking is in its actual sense not pleasurable and in any case it does not bring any relief. It is therefore the desire of many smokers to quit smoking. The knowledge that smoking can lead to serious health problems is one that is conscious in every smoker. This may make the smoker stay worried yet overcoming the addiction is a problem.

As such, quitting smoking is important since it helps relief the worry and the fear associated with possibility of developing cancer among other smoking-related illnesses. The smell that comes with smoking is very embarrassing and most people hate it.

Quitting smoking is therefore an important way of regaining self confidence by doing away with the embarrassing smell of cigarette smoke. Quitting smoking is an important way of shedding off the worry of the constant coughs and short breath brought about by smoking (Quit Smoking Review para 2-3).

Quitting smoking comes with a myriad of benefits which place more weight on the importance of quitting this addictive habit. If one quits smoking, it is no doubt that someone else is also saved from the problem of chain smoking. It is important that smokers reconsider their actions and identify that they spread the negative effects of smoking to persons who would not like to smoke.

It is therefore important to quit smoking if the problems associated with chain smoking are to be solved. The unborn are also beneficiaries of quitting smoking, especially among pregnant mothers. The elimination of very dangerous chemicals from the body motivates many people to avoid the practice. Most smokers thus find the health benefits as an encouraging gesture to quit smoking.

Quitting smoking is important since it leads to saving of monies that would have been used to buy cigarettes. These daily savings resulting from quitting smoking can be put into wiser and productive ways such as helping the family to settle bills as well as saving the money for investing. The fact that every individual’s lifestyle seems to influence another person’s life is an important reason why it is advisable to quit smoking. For instance, parents can act as good role models to their children by choosing to quit smoking.

In such a case, children are able to appreciate that smoking is a harmful habit and they will view the parent as a proactive parent as far as achieving good health is concerned. Additionally, quitting smoking gives the individual whiter and good looking teeth coupled with a fresh breath (Quit Smoking Review para 4-5). Most smokers are prone to gum diseases among other mouth diseases in comparison to non-smokers.

The individual’s health is also greatly improved as the breathing system that was once clogged with tobacco particles becomes clear and the lung capacity improves generally by about 10% (Gilman & Xun 45). Young smokers may not experience the negative effects of smoking until their later years but lung capacity generally weakens and diminishes with age.

Further, quitting smoking increases the individual’s life span, as Gilman and Xun (51) notes that half of all long-term smokers die from smoking related diseases such as heart attacks, lung cancer and others such as chronic bronchitis.

Those who quit smoking at age 30 are at an advantage as they add almost 10 years of their life span. As earlier mentioned stress levels are lower after one quits smoking since one has overcome the annoying habit. Most smokers suffer from withdrawal effects especially from nicotine, and the pleasant feeling of satisfying a craving is very temporary. Thus, non-smokers can concentrate better than smokers.

The body senses are also improved to a great extent as the system gets rid of many toxic chemicals found in the body as a result of cigarette smoke. Additionally, the individual experiences more energy as two weeks after quitting smoking, the circulation improves making many physical activities much easier. Additionally, the immune system is improved as mild diseases such as flu, colds and headaches can be easily fought.

In general, quitting smoking is an important step towards realizing an overall improvement in quality of life. Quitting smoking is also an important measure of ensuring cleanliness in one’s environment (American Academy of Family Physicians para 6).

Once one has quit smoking, the cigarette butts and ashes that are common in houses or cars of the smoker are no longer seen. This leads to greater happiness to the individual as well as those who live with the smoker. In addition, there is no need to worry much over the possible fire outbreaks brought about by careless disposal of burning cigarette butts.

Works Cited

American Academy of Family Physicians. Do I want to quit smoking ? 2000. Web.

Gilman, Sander and Xun, Zhou. Smoke: A global history of smoking . London, UK: Reaktion Books. 2004. Print.

Quit Smoking Review. The importance of quitting smoking . Web.

- The Social Contract Aspects

- Respect and Its Significance

- The Moral Dilemma: Nephrologist's Choices

- Quitting Smoking and Related Health Benefits

- Psychosocial Smoking Rehabilitation

- Women in the Contemporary Society

- Sexuality and Masculinity in Adolescents

- The Challenges and Advantages of Facebook

- Stay-At-Home Dads

- Social Article About Websites' Problem by Jenna Wortham

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2020, April 27). Importance of Quitting Smoking. https://ivypanda.com/essays/importance-of-quitting-smoking/

"Importance of Quitting Smoking." IvyPanda , 27 Apr. 2020, ivypanda.com/essays/importance-of-quitting-smoking/.

IvyPanda . (2020) 'Importance of Quitting Smoking'. 27 April.

IvyPanda . 2020. "Importance of Quitting Smoking." April 27, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/importance-of-quitting-smoking/.

1. IvyPanda . "Importance of Quitting Smoking." April 27, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/importance-of-quitting-smoking/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Importance of Quitting Smoking." April 27, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/importance-of-quitting-smoking/.

IvyPanda uses cookies and similar technologies to enhance your experience, enabling functionalities such as:

- Basic site functions

- Ensuring secure, safe transactions

- Secure account login

- Remembering account, browser, and regional preferences

- Remembering privacy and security settings

- Analyzing site traffic and usage

- Personalized search, content, and recommendations

- Displaying relevant, targeted ads on and off IvyPanda

Please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy for detailed information.

Certain technologies we use are essential for critical functions such as security and site integrity, account authentication, security and privacy preferences, internal site usage and maintenance data, and ensuring the site operates correctly for browsing and transactions.

Cookies and similar technologies are used to enhance your experience by:

- Remembering general and regional preferences

- Personalizing content, search, recommendations, and offers

Some functions, such as personalized recommendations, account preferences, or localization, may not work correctly without these technologies. For more details, please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy .

To enable personalized advertising (such as interest-based ads), we may share your data with our marketing and advertising partners using cookies and other technologies. These partners may have their own information collected about you. Turning off the personalized advertising setting won't stop you from seeing IvyPanda ads, but it may make the ads you see less relevant or more repetitive.

Personalized advertising may be considered a "sale" or "sharing" of the information under California and other state privacy laws, and you may have the right to opt out. Turning off personalized advertising allows you to exercise your right to opt out. Learn more in IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy .

Harms of Cigarette Smoking and Health Benefits of Quitting

What harmful chemicals does tobacco smoke contain.

Tobacco smoke contains many chemicals that are harmful to both smokers and nonsmokers. Breathing even a little tobacco smoke can be harmful ( 1 - 4 ).

Of the more than 7,000 chemicals in tobacco smoke, at least 250 are known to be harmful, including hydrogen cyanide , carbon monoxide , and ammonia ( 1 , 2 , 5 ).

Among the 250 known harmful chemicals in tobacco smoke, at least 69 can cause cancer. These cancer-causing chemicals include the following ( 1 , 2 , 5 ):

- Acetaldehyde

- Aromatic amines

- Beryllium (a toxic metal)

- 1,3–Butadiene (a hazardous gas)

- Cadmium (a toxic metal)

- Chromium (a metallic element)

- Ethylene oxide

- Formaldehyde

- Nickel (a metallic element)

- Polonium-210 (a radioactive chemical element)

- Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs)

- Tobacco-specific nitrosamines

- Vinyl chloride

What are some of the health problems caused by cigarette smoking?

Smoking is the leading cause of premature, preventable death in this country. Cigarette smoking and exposure to tobacco smoke cause about 480,000 premature deaths each year in the United States ( 1 ). Of those premature deaths, about 36% are from cancer, 39% are from heart disease and stroke , and 24% are from lung disease ( 1 ). Mortality rates among smokers are about three times higher than among people who have never smoked ( 6 , 7 ).

Smoking harms nearly every bodily organ and organ system in the body and diminishes a person’s overall health. Smoking causes cancers of the lung, esophagus, larynx, mouth, throat, kidney, bladder, liver, pancreas, stomach, cervix, colon, and rectum, as well as acute myeloid leukemia ( 1 – 3 ).

Smoking also causes heart disease, stroke, aortic aneurysm (a balloon-like bulge in an artery in the chest), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) ( chronic bronchitis and emphysema ), diabetes , osteoporosis , rheumatoid arthritis, age-related macular degeneration , and cataracts , and worsens asthma symptoms in adults. Smokers are at higher risk of developing pneumonia , tuberculosis , and other airway infections ( 1 – 3 ). In addition, smoking causes inflammation and impairs immune function ( 1 ).

Since the 1960s, a smoker’s risk of developing lung cancer or COPD has actually increased compared with nonsmokers, even though the number of cigarettes consumed per smoker has decreased ( 1 ). There have also been changes over time in the type of lung cancer smokers develop – a decline in squamous cell carcinomas but a dramatic increase in adenocarcinomas . Both of these shifts may be due to changes in cigarette design and composition, in how tobacco leaves are cured, and in how deeply smokers inhale cigarette smoke and the toxicants it contains ( 1 , 8 ).

Smoking makes it harder for a woman to get pregnant. A pregnant smoker is at higher risk of miscarriage, having an ectopic pregnancy , having her baby born too early and with an abnormally low birth weight, and having her baby born with a cleft lip and/or cleft palate ( 1 ). A woman who smokes during or after pregnancy increases her infant’s risk of death from Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) ( 2 , 3 ). Men who smoke are at greater risk of erectile dysfunction ( 1 , 9 ).

The longer a smoker’s duration of smoking, the greater their likelihood of experiencing harm from smoking, including earlier death ( 7 ). But regardless of their age, smokers can substantially reduce their risk of disease, including cancer, by quitting.

What are the risks of tobacco smoke to nonsmokers?

Secondhand smoke (also called environmental tobacco smoke, involuntary smoking, and passive smoking) is the combination of “sidestream” smoke (the smoke given off by a burning tobacco product) and “mainstream” smoke (the smoke exhaled by a smoker) ( 4 , 5 , 10 , 11 ).

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the U.S. National Toxicology Program, the U.S. Surgeon General, and the International Agency for Research on Cancer have classified secondhand smoke as a known human carcinogen (cancer-causing agent) ( 5 , 11 , 12 ). Inhaling secondhand smoke causes lung cancer in nonsmoking adults ( 1 , 2 , 4 ). Approximately 7,300 lung cancer deaths occur each year among adult nonsmokers in the United States as a result of exposure to secondhand smoke ( 1 ). The U.S. Surgeon General estimates that living with a smoker increases a nonsmoker’s chances of developing lung cancer by 20 to 30% ( 4 ).

Secondhand smoke causes disease and premature death in nonsmoking adults and children ( 2 , 4 ). Exposure to secondhand smoke irritates the airways and has immediate harmful effects on a person’s heart and blood vessels. It increases the risk of heart disease by an estimated 25 to 30% ( 4 ). In the United States, exposure to secondhand smoke is estimated to cause about 34,000 deaths from heart disease each year ( 1 ). Exposure to secondhand smoke also increases the risk of stroke by 20 to 30% ( 1 ). Pregnant women exposed to secondhand smoke are at increased risk of having a baby with a small reduction in birth weight ( 1 ).

Children exposed to secondhand smoke are at an increased risk of SIDS, ear infections, colds, pneumonia, and bronchitis. Secondhand smoke exposure can also increase the frequency and severity of asthma symptoms among children who have asthma. Being exposed to secondhand smoke slows the growth of children’s lungs and can cause them to cough, wheeze, and feel breathless ( 2 , 4 ).

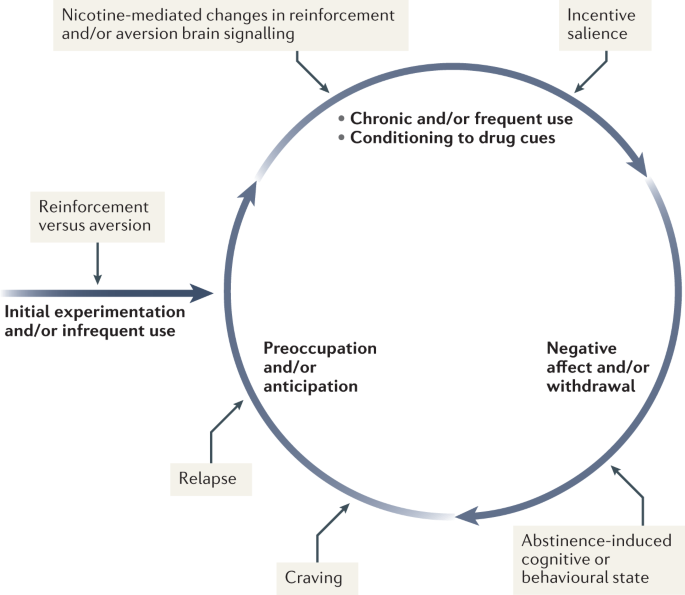

Is smoking addictive?

Smoking is highly addictive. Nicotine is the drug primarily responsible for a person’s addiction to tobacco products, including cigarettes. The addiction to cigarettes and other tobacco products that nicotine causes is similar to the addiction produced by using drugs such as heroin and cocaine ( 13 ). Nicotine is present naturally in the tobacco plant. But tobacco companies intentionally design cigarettes to have enough nicotine to create and sustain addiction.

The amount of nicotine that gets into the body is determined by the way a person smokes a tobacco product and by the nicotine content and design of the product. Nicotine is absorbed into the bloodstream through the lining of the mouth and the lungs and travels to the brain in a matter of seconds. Taking more frequent and deeper puffs of tobacco smoke increases the amount of nicotine absorbed by the body.

Are other tobacco products, such as smokeless tobacco or pipe tobacco, harmful and addictive?

Yes. All forms of tobacco are harmful and addictive ( 4 , 11 ). There is no safe tobacco product.

In addition to cigarettes, other forms of tobacco include smokeless tobacco , cigars , pipes , hookahs (waterpipes), bidis , and kreteks .

- Smokeless tobacco : Smokeless tobacco is a type of tobacco that is not burned. It includes chewing tobacco , oral tobacco, spit or spitting tobacco, dip, chew, snus, dissolvable tobacco, and snuff. Smokeless tobacco causes oral (mouth, tongue, cheek and gum), esophageal, and pancreatic cancers and may also cause gum and heart disease ( 11 , 14 ).

- Cigars : These include premium cigars, little filtered cigars (LFCs), and cigarillos. LFCs resemble cigarettes, but both LFCs and cigarillos may have added flavors to increase appeal to youth and young adults ( 15 , 16 ). Most cigars are composed primarily of a single type of tobacco (air-cured and fermented), and have a tobacco leaf wrapper. Studies have found that cigar smoke contains higher levels of toxic chemicals than cigarette smoke, although unlike cigarette smoke, cigar smoke is often not inhaled ( 11 ). Cigar smoking causes cancer of the oral cavity, larynx, esophagus, and lung. It may also cause cancer of the pancreas. Moreover, daily cigar smokers, particularly those who inhale, are at increased risk for developing heart disease and other types of lung disease.

- Pipes : In pipe smoking, the tobacco is placed in a bowl that is connected to a stem with a mouthpiece at the other end. The smoke is usually not inhaled. Pipe smoking causes lung cancer and increases the risk of cancers of the mouth, throat, larynx, and esophagus ( 11 , 17 , 18 ).

- Hookah or waterpipe (other names include argileh, ghelyoon, hubble bubble, shisha, boory, goza, and narghile): A hookah is a device used to smoke tobacco (often heavily flavored) by passing the smoke through a partially filled water bowl before being inhaled by the smoker. Although some people think hookah smoking is less harmful and addictive than cigarette smoking ( 19 ), research shows that hookah smoke is at least as toxic as cigarette smoke ( 20 – 22 ).

- Bidis : A bidi is a flavored cigarette made by rolling tobacco in a dried leaf from the tendu tree, which is native to India. Bidi use is associated with heart attacks and cancers of the mouth, throat, larynx, esophagus, and lung ( 11 , 23 ).

- Kreteks : A kretek is a cigarette made with a mixture of tobacco and cloves. Smoking kreteks is associated with lung cancer and other lung diseases ( 11 , 23 ).

Is it harmful to smoke just a few cigarettes a day?

There is no safe level of smoking. Smoking even just one cigarette per day over a lifetime can cause smoking-related cancers (lung, bladder, and pancreas) and premature death ( 24 , 25 ).

What are the immediate health benefits of quitting smoking?

The immediate health benefits of quitting smoking are substantial:

- Heart rate and blood pressure , which are abnormally high while smoking, begin to return to normal.

- Within a few hours, the level of carbon monoxide in the blood begins to decline. (Carbon monoxide reduces the blood’s ability to carry oxygen.)

- Within a few weeks, people who quit smoking have improved circulation, produce less phlegm , and don’t cough or wheeze as often.

- Within several months of quitting, people can expect substantial improvements in lung function ( 26 ).

- Within a few years of quitting, people will have lower risks of cancer, heart disease, and other chronic diseases than if they had continued to smoke.

What are the long-term health benefits of quitting smoking?

Quitting smoking reduces the risk of cancer and many other diseases, such as heart disease and COPD , caused by smoking.

Data from the U.S. National Health Interview Survey show that people who quit smoking, regardless of their age, are less likely to die from smoking-related illness than those who continue to smoke. Smokers who quit before age 40 reduce their chance of dying prematurely from smoking-related diseases by about 90%, and those who quit by age 45-54 reduce their chance of dying prematurely by about two-thirds ( 6 ).

Regardless of their age, people who quit smoking have substantial gains in life expectancy, compared with those who continue to smoke. Data from the U.S. National Health Interview Survey also show that those who quit between the ages of 25 and 34 years live about 10 years longer; those who quit between ages 35 and 44 live about 9 years longer; those who quit between ages 45 and 54 live about 6 years longer; and those who quit between ages 55 and 64 live about 4 years longer ( 6 ).

Also, a study that followed a large group of people age 70 and older ( 7 ) found that even smokers who quit smoking in their 60s had a lower risk of mortality during follow-up than smokers who continued smoking.

Does quitting smoking lower the risk of getting and dying from cancer?

Yes. Quitting smoking reduces the risk of developing and dying from cancer and other diseases caused by smoking. Although it is never too late to benefit from quitting, the benefit is greatest among those who quit at a younger age ( 3 ).

The risk of premature death and the chances of developing and dying from a smoking-related cancer depend on many factors, including the number of years a person has smoked, the number of cigarettes smoked per day, and the age at which the person began smoking.

Is it important for someone diagnosed with cancer to quit smoking?

Quitting smoking improves the prognosis of cancer patients. For patients with some cancers, quitting smoking at the time of diagnosis may reduce the risk of dying by 30% to 40% ( 1 ). For those having surgery, chemotherapy, or other treatments, quitting smoking helps improve the body’s ability to heal and respond to therapy ( 1 , 3 , 27 ). It also lowers the risk of pneumonia and respiratory failure ( 1 , 3 , 28 ). In addition, quitting smoking may lower the risk that the cancer will recur, that a second cancer will develop, or that the person will die from the cancer or other causes ( 27 , 29 – 32 ).

Where can I get help to quit smoking?

NCI and other agencies and organizations can help smokers quit:

- Visit Smokefree.gov for access to free information and resources, including Create My Quit Plan , smartphone apps , and text message programs

- Call the NCI Smoking Quitline at 1–877–44U–QUIT ( 1–877–448–7848 ) for individualized counseling, printed information, and referrals to other sources.

- See the NCI fact sheet Where To Get Help When You Decide To Quit Smoking .

- Fact sheets

- Facts in pictures

- Publications

- Questions and answers

- Tools and toolkits

- Endometriosis

- Excessive heat

- Mental disorders

- Polycystic ovary syndrome

- All countries

- Eastern Mediterranean

- South-East Asia

- Western Pacific

- Data by country

- Country presence

- Country strengthening

- Country cooperation strategies

- News releases

- Feature stories

- Press conferences

- Commentaries

- Photo library

- Afghanistan

- Cholera

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Greater Horn of Africa

- Israel and occupied Palestinian territory

- Disease Outbreak News

- Situation reports

- Weekly Epidemiological Record

- Surveillance

- Health emergency appeal

- International Health Regulations

- Independent Oversight and Advisory Committee

- Classifications

- Data collections

- Global Health Observatory

- Global Health Estimates

- Mortality Database

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Health Inequality Monitor

- Global Progress

- World Health Statistics

- Partnerships

- Committees and advisory groups

- Collaborating centres

- Technical teams

- Organizational structure

- Initiatives

- General Programme of Work

- WHO Academy

- Investment in WHO

- WHO Foundation

- External audit

- Financial statements

- Internal audit and investigations

- Programme Budget

- Results reports

- Governing bodies

- World Health Assembly

- Executive Board

- Member States Portal

- Commentaries /

Quit tobacco to be a winner

World no tobacco day 2021 campaign - commit to quit.

The saying goes that “quitters never win,” but in the case of tobacco, quitters are the real winners.

When the news came out that smokers were more likely to develop severe disease with COVID-19 compared to non-smokers, it triggered millions of smokers to want to quit tobacco. But without adequate support, quitting can be incredibly challenging.

The nicotine found in tobacco is highly addictive and creates dependence. The behavioural and emotional ties to tobacco use – like having a cigarette with your coffee, craving tobacco, feelings of sadness or stress – make it hard to kick the habit.

With professional support and cessation services, tobacco users double their chances of quitting successfully.

Currently, over 70% of the 1.3 billion tobacco users worldwide lack access to the tools they need to quit successfully. This gap in access to cessation services is only further exacerbated in the last year as the health workforce has been mobilized to handle the pandemic.

That’s why WHO launched a year-long campaign for World No Tobacco Day’s – “Commit to Quit” theme. The campaign aims to empower 100 million tobacco users to make a quit attempt by creating networks of support and increasing access to services proven to help tobacco users quit successfully.

This will be achieved by scaling-up existing services such as brief advice from health professionals and national toll free quit lines, as well as launching innovative services like Florence, WHO’s first digital health worker, and chatbot support programmes on WhatsApp and Viber.

To truly help tobacco users quit, they need to be supported with tried and tested policies and interventions to drive down the demand for tobacco.

The WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC) provides a strong, concerted response to the global tobacco epidemic and its enormous health, social, environmental and economic costs. To help countries implement the WHO FCTC, WHO introduced the MPOWER technical package to support implementation of key strategies, such as raising tobacco taxes, creating smoke-free environments and offering help to quit.

E-cigarettes are not proven cessation aids

The tobacco industry has continuously attempted to subvert these life-saving public health measures. Over the last decade, the tobacco industry has promoted e-cigarettes as cessation aids under the guises of contributing to global tobacco control. Meanwhile, they have employed strategic marketing tactics to hook children on this same portfolio of products, making them available in over 15,000 attractive flavours.

The scientific evidence on e-cigarettes as cessation aids is inconclusive and there is a lack of clarity as to whether these products have any role to play in smoking cessation. Switching from conventional tobacco products to e-cigarettes is not quitting.

"We must be guided by science and evidence, not the marketing campaigns of the tobacco industry – the same industry that has engaged in decades of lies and deceit to sell products that have killed hundreds of millions of people”, said WHO Director-General Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus. “E-cigarettes generate toxic chemicals, which have been linked to harmful health effects such as cardiovascular disease & lung disorders."

Why does the UN prohibit partnerships with the tobacco industry and their front groups?

The tobacco industry is the single greatest barrier to reducing deaths caused by tobacco use. Their interests are irreconcilably opposed to promoting public health, and point to a critical need to keep them out of global tobacco control efforts.

WHO FCTC Article 5.3 aims to do just that. WHO established a firewall in 2007 to protect policies from commercial and other vested interests of the tobacco industry. The United Nations Global Compact followed suit, banning the tobacco industry from participation in 2017, flagging the problematic and irreconcilable conflicts between the goals of the UN and an industry that is responsible for more than 8 million deaths per year. In line with Article 5.3, industry has been entirely excluded from the UN system and its agencies have been urged to devise strategies to prevent industry interference.

The United Nations Inter-Agency Task Force on the Prevention and Control of NCDs , which has both the WHO and the Secretariat of the WHO FCTC as leading participants, has crafted a Model policy for agencies of the United Nations system on preventing tobacco industry interference , a strong policy to prevent industry tactics operating in the UN and then ensured its implementation at the intergovernmental level.

In 2008, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a Resolution for Smoke-free United Nations Premises, and in 2012, the United Nations Economic and Social Council called for “system-wide coherence on tobacco control”. The creation of smoke-free campuses puts into practice the United Nations smoke-free workplace policy, which aims to protect approximately 100,000 UN staff members from second-hand tobacco smoke.

WHO and the Secretariat of the WHO FCTC have stated that no partnerships should be forged with tobacco industry front groups such as the Foundation for a Smoke Free World. PMI has committed to spending one billion USD over 12 years funding a new captive organization, the Foundation for a Smoke Free World (FSFW) – Philip Morris International (PMI) is its sole funder – to reproduce and launder its harm-reduction messages.

The importance of tobacco duties and taxes and smoke-free workplaces

Despite these challenges brought on by the tobacco industry, the world has seen significant progress in tobacco control.

Since the MPOWER technical package was introduced more than a decade ago, 5 billion people have now been covered by at least one of these best-practice tobacco control measures, has more than quadrupled since 2007.Over the last two decades, global tobacco use has fallen by 60 million people. But the decrease varies by region and we are now seeing the tobacco industry vigorously target low-and middle-income countries with traditional cigarettes, while pushing its new and emerging products in higher income countries.

WHO urges governments to help tobacco users quit by providing the support, services, policies and tobacco taxes that enable people to quit.

Smoke-free policies have the potential to protect non-smokers, including over 65,000 children and adolescents who die every year from exposure to second-hand smoke.

Tobacco costs economies over US$ 1.4 trillion in health expenditures and lost productivity, which is equivalent to 1.8% of annual global GDP. Increasing tobacco taxes helps make these lethal products less affordable and helps cover health-care costs for the diseases they create.

There has never been a better time to quit tobacco, and commitment to helping tobacco users quit is critical to improving health and saving lives.

Dr Ruediger Krech

Director Health Promotion World Health Organization

World No Tobacco Day 2021

WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control

Alonzo Mourning, Prostate Cancer Survivor

Online Help

Our 24/7 cancer helpline provides information and answers for people dealing with cancer. We can connect you with trained cancer information specialists who will answer questions about a cancer diagnosis and provide guidance and a compassionate ear.

Chat live online

Select the Live Chat button at the bottom of the page

Call us at 1-800-227-2345

Available any time of day or night

Our highly trained specialists are available 24/7 via phone and on weekdays can assist through online chat. We connect patients, caregivers, and family members with essential services and resources at every step of their cancer journey. Ask us how you can get involved and support the fight against cancer. Some of the topics we can assist with include:

- Referrals to patient-related programs or resources

- Donations, website, or event-related assistance

- Tobacco-related topics

- Volunteer opportunities

- Cancer Information

For medical questions, we encourage you to review our information with your doctor.

Cancer Risk and Prevention

- Common Questions About Causes of Cancer

- Is Cancer Contagious?

- Lifetime Risk of Developing or Dying From Cancer

- How to Interpret News About Cancer Causes

- Determining if Something Is a Carcinogen

- Known and Probable Human Carcinogens

- Cancer Clusters

- Cancer Warning Labels Based on California's Proposition 65

- Cancer Facts for Men

- Cancer Facts for Gay and Bisexual Men

- Cancer Facts for Women

- Cancer Facts for Lesbian and Bisexual Women

- How to Interpret News About Ways to Prevent Cancer

Reasons to Quit Smoking

- Health Benefits of Quitting Smoking Over Time

- Making a Plan to Quit and Planning Your Quit Day

- Quitting Smoking or Smokeless Tobacco

- Quitting E-cigarettes

- Nicotine Replacement Therapy to Help You Quit Tobacco

- Dealing with the Mental Part of Tobacco Addiction

- Prescription Medicines to Help You Quit Tobacco

- Ways to Quit Tobacco Without Using Medicines

- Staying Tobacco-free After You Quit

- Help for Cravings and Tough Situations While You're Quitting Tobacco

- How to Help Someone Quit Smoking

- Why People Start Smoking and Why It’s Hard to Stop

- Health Risks of Smoking Tobacco

- Health Risks of Smokeless Tobacco

- Health Risks of Secondhand Smoke

- Health Risks of E-cigarettes

- Harmful Chemicals in Tobacco Products

- Is Any Type of Tobacco Product Safe?

- ACS Position Statement on Electronic Cigarettes

- What Do We Know About E-cigarettes?

- Keeping Your Kids Tobacco-free

- History of the Great American Smokeout

- Great American Smokeout Event Tools and Resources

Empowered to Quit

- American Cancer Society Guideline for Diet and Physical Activity

- Effects of Diet and Physical Activity on Risks for Certain Cancers

- Common Questions About Diet, Activity, and Cancer Risk

- Infographic: Diet and Activity Guidelines to Reduce Cancer Risk

- Diet and Physical Activity: What’s the Cancer Connection?

- Stock Your Kitchen with Healthy Ingredients

- Tips for Eating Healthier

- Find Healthy Recipes

- Quick Entrees: Healthy in a Hurry

- Snacks and Dashboard Dining

- Tips for Eating Out

- Calorie Counter

- Controlling Portion Sizes

- Cut Calories and Fat, Not Flavor

- Low-Fat Foods

- Understanding Food Terms

- Fitting in Fitness

- Kids on the Move

- Community Actions for a Healthful Life

- Exercise Activity Calculator

- Target Heart Rate Calculator

- Find Your Body Mass Index (BMI)

- Alcohol Use and Cancer

- Nutrition and Activity Quiz

- Healthy Eating, Active Living Videos

- What Is HPV (Human Papillomavirus)?

- Types of HPV

- Cancers Linked with HPV

- HPV Signs and Symptoms

- How to Protect Against HPV

- HPV Testing

- HPV Vaccines

- HPV Vaccine in Texas

- Understanding Family Cancer Syndromes

- Ataxia-telangiectasia (A-T)

- Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome (BHD)

- Carney Complex (CNC)

- Cowden Syndrome

- Familial GIST Syndrome

- Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Syndrome (HBOC)

- Li-Fraumeni Syndrome (LFS)

- Lynch Syndrome

- Understanding Genetic Testing for Cancer Risk

- What Should I Know Before Getting Genetic Testing?

- What Happens During Genetic Testing for Cancer Risk?

- What Are X-rays and Gamma Rays?

- How Are People Exposed to X-rays and Gamma Rays?

- Do X-rays and Gamma Rays Cause Cancer?

- Do X-rays and Gamma Rays Cause Health Problems Other than Cancer?

- Can I Avoid or Limit My Exposure to X-rays and Gamma Rays?

- Radiofrequency (RF) Radiation

- Power Lines, Electrical Devices, and Extremely Low Frequency Radiation

- Cellular (Cell) Phones

- Cell Phone Towers

- Smart Meters

- Agent Orange

- Antiperspirants

- Diesel Exhaust

- Firefighting

- Formaldehyde

- Military Burn Pits

- Recombinant Bovine Growth Hormone (rBGH)

- PFOA, PFOS, and Related PFAS Chemicals

- Talcum Powder

- Water Fluoridation

- Can Infections Cause Cancer?

- Viruses that Can Lead to Cancer

- Bacteria that Can Lead to Cancer

- Parasites that Can Lead to Cancer

- What Are HIV and AIDS?

- HIV and Cancer

- Abortion and Breast Cancer Risk

- DES Exposure: Questions and Answers

- Menopausal Hormone Therapy and Cancer Risk

- UV (Ultraviolet) Radiation and Cancer Risk

- Sun Safety and Vitamin D

- What Factors Affect UV Risk?

- Is It Safe to Get a Fake (Sunless) Tan?

- How to Protect Your Skin from UV Rays

- How to Use Sunscreen

- How to Do a Skin Self-Exam

- Sun Safety Quiz

- Sun Safety Videos

Lots of studies have been done about the benefits of quitting smoking. Decades of research have found several good reasons to quit, including health and financial benefits that can save lives and money. While it’s best to quit as early in life as possible, quitting at any age can lead to a better health and lifestyle.

Quitting can make you look, feel, and be healthier

- Quitting can help you save money

Quitting can improve self-confidence and lead to a better lifestyle

- Using tobacco leads to disease and disability and harms nearly every organ of the body.

- Smoking is the leading cause of preventable death.

- Secondhand smoke is dangerous and can harm the health of your friends and family.

Quitting can help you save money

- Cigarettes and other tobacco products are expensive.

- The risk for getting colds and other respiratory problems is lower, meaning fewer doctor visits, less money spent on medicines, and fewer sick days off work.

- Cleaning and home repairs could cost less since clothes, furniture, curtains, and the car won’t smell like tobacco.

- Not using tobacco products helps keep your family safe.

- Your may have more energy, helping you have more quality family and leisure time.

- Quitting can set a good example for others who might need help quitting.

- Others will be proud of your progress and willpower to quit and stay quit.

The American Cancer Society medical and editorial content team

Our team is made up of doctors and oncology certified nurses with deep knowledge of cancer care as well as editors and translators with extensive experience in medical writing.

This content has been developed by the American Cancer Society in collaboration with the Smoking Cessation Leadership Center to help people who want to learn about quitting tobacco.

Smokefree.gov Reasons to quit. Available at https://smokefree.gov/quit-smoking/why-you-should-quit/reasons-to-quit. Accessed October 10, 2020.

US Department of Health and Human Services. What you need to know about quitting smoking: Advice from the Surgeon General. Available at https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/2020-cessation-sgr-consumer-guide.pdf. Accessed October 10, 2020.

Last Revised: October 10, 2020

American Cancer Society medical information is copyrighted material. For reprint requests, please see our Content Usage Policy .

American Cancer Society Emails

Sign up to stay up-to-date with news, valuable information, and ways to get involved with the American Cancer Society.

Related Resources

A free, email-based smoking cessation program from the American Cancer Society.

Help us end cancer as we know it, for everyone.

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Tobacco, Nicotine, and E-Cigarettes Research Report How can we prevent tobacco use?

The medical consequences of tobacco use—including secondhand exposure—make tobacco control and smoking prevention crucial parts of any public health strategy. Since the first Surgeon General’s Report on Smoking and Health in 1964, states and communities have made efforts to reduce initiation of smoking, decrease exposure to smoke, and increase cessation. Researchers estimate that these tobacco control efforts are associated with averting an estimated 8 million premature deaths and extending the average life expectancy of men by 2.3 years and of women by 1.6 years. 18 But there is a long way yet to go: roughly 5.6 million adolescents under age 18 are expected to die prematurely as a result of an illness related to smoking. 13

Prevention can take the form of policy-level measures, such as increased taxation of tobacco products; stricter laws (and enforcement of laws) regulating who can purchase tobacco products; how and where they can be purchased; where and when they can be used (i.e., smoke-free policies in restaurants, bars, and other public places); and restrictions on advertising and mandatory health warnings on packages. Over 100 studies have shown that higher taxes on cigarettes, for example, produce significant reductions in smoking, especially among youth and lower-income individuals. 217 Smoke-free workplace laws and restrictions on advertising have also shown benefits. 218

Prevention can also take place at the school or community level. Merely educating potential smokers about the health risks has not proven effective. 218 Successful evidence-based interventions aim to reduce or delay initiation of smoking, alcohol use, and illicit drug use, and otherwise improve outcomes for children and teens by reducing or mitigating modifiable risk factors and bolstering protective factors. Risk factors for smoking include having family members or peers who smoke, being in a lower socioeconomic status, living in a neighborhood with high density of tobacco outlets, not participating in team sports, being exposed to smoking in movies, and being sensation-seeking. 219 Although older teens are more likely to smoke than younger teens, the earlier a person starts smoking or using any addictive substance, the more likely they are to develop an addiction. Males are also more likely to take up smoking in adolescence than females.

Some evidence-based interventions show lasting effects on reducing smoking initiation. For instance, communities utilizing the intervention-delivery system, Communities that Care (CTC) for students aged 10 to14 show sustained reduction in male cigarette initiation up to 9 years after the end of the intervention. 220

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- About Health Effects of Cigarette Smoking

- Secondhand Smoke

- E-cigarettes (Vapes)

- Menthol Tobacco Products

- Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports (MMWR)

- About Surveys

- Other Tobacco Products

- Smoking and Tobacco Use Features

- Patient Care Settings and Smoking Cessation

- Patient Care

- Funding Opportunity Announcements

- State and Community Work

- National and State Tobacco Control Program

- Multimedia and Tools

Related Topics:

- View All Home

- Tobacco - Health Equity

- Tobacco - Surgeon General's Reports

- State Tobacco Activities Tracking and Evaluation (STATE) System

- Global Tobacco Control

World No Tobacco Day: Protect Our Youth

At a glance.

Learn what individuals and communities can do to help keep young people tobacco-free, or help them quit for good, on this World No Tobacco Day.

Why observe World No Tobacco Day?

Using any kind of tobacco product is unsafe, especially for kids, teens, and young adults. But worldwide, at least 14 million young people aged 13 to 15 currently use tobacco products, according to CDC's 2006–2017 Global Youth Tobacco Survey .

Tobacco companies, meanwhile, spend billions of dollars every year on marketing tobacco products, including cigarettes, cigars, and e-cigarettes.

Since 1988, the World Health Organization (WHO) has used World No Tobacco Day to highlight the harmful effects of cigarettes and other tobacco products on a person's overall health. This year, WHO is focusing on preventing youth tobacco product use and the tobacco industry's attempts to attract youth.

This World No Tobacco Day, learn what individuals and communities can do to help keep young people tobacco-free, or help them quit for good.

U.S. youth and tobacco: the numbers

In 2019, about 40% of U.S. middle and high school students reported ever using any kind of tobacco product—including e-cigarettes —and 23% said they had used a tobacco product in the past 30 days.

Studies show that most adults in the United States who regularly use tobacco products started before the age of 18. Using any tobacco product, including e-cigarettes, is unsafe for young people .

Tobacco products—including cigarettes, smokeless tobacco, and most e-cigarettes—contain nicotine, which is an addictive drug. Being exposed to nicotine can also harm brain development. A young person's brain is still developing up to age 25. Exposure to nicotine during these important years can harm the parts of the brain that control attention, learning, mood, and impulse control.

Secondhand smoke: a danger at home and abroad

At least 500 million people younger than 15 in 21 countries are exposed to secondhand smoke .

It's a problem in the United States:

- 1 in 4 Americans, or about 58 million people, are exposed to secondhand smoke.

- Children aged 3 to 11 have the highest exposure to secondhand smoke compared to any other age group.

- African American children are more likely to be exposed to secondhand smoke than children of other racial or ethnic groups.

Quitting smoking and adopting smokefree policies help protect the health of people who do not smoke.

Targeting young people

The younger a person is when they start using tobacco products, the more likely they are to become dependent on nicotine. The tobacco industry uses this information to attract youth and young people to their products through ads and sponsorships in stores, online, in media, and at cultural events.

Studies in the United States and other countries have shown that the more ads for tobacco products a young person sees, the more likely they are to use tobacco products. The U.S. Surgeon General has also said that seeing people smoke in movies makes youth more likely to smoke. Although the number of movies rated PG-13 or lower that feature smoking has gone down in the past 15 years, the films that do show smoking show it more often.

Tobacco flavors

The flavors in tobacco products, including e-cigarettes, make these products appealing to kids and teens. Since 2009, tobacco companies have not been allowed to sell cigarettes in flavors other than menthol in the United States. Still, youth are more likely than adults to smoke menthol cigarettes .

Flavoring is also a major driver of e-cigarette use among young people. More than 2 out of 3 youth who currently use e-cigarettes use flavored e-cigarettes, and flavors are a major reason they report starting to use e-cigarettes.

The danger of e-cigarettes for youth

Since 2014, most U.S. youth who said they had ever used tobacco products reported using e-cigarettes. This percentage has grown over time. E-cigarettes typically contain nicotine. Newer e-cigarettes use a new form of nicotine called nicotine salts, which make it easier to inhale higher levels of nicotine.

Because of the recent rise in e-cigarette use by U.S. middle and high school students, CDC offers resources for parents , teachers , and health care providers to help them talk to kids about e-cigarettes.

What you can do

Everyone—from individuals who influence youth directly to whole communities—can help prevent kids, teens, and young adults from trying and using tobacco products.

Parents and other caregivers can:

- Set a good example by being tobacco-free. They can call 1-800-QUIT-NOW or visit smokefree.gov for help with quitting.

- Talk to kids about the harms of tobacco products, including e-cigarettes.

- Know what kids watch on screen and talk to them about tobacco use.

- Tell kids you expect them not to use tobacco products or tell them to stop using them.

- Refuse to give tobacco products to kids, teens, or young adults.

The Office of the Surgeon General has more tips for parents and caregivers to help keep young people tobacco-free.

Health care providers can:

- Talk to their patients about the dangers of tobacco use. In a 2015 survey, only 1 out of 3 U.S. high schoolers said their doctor brought up smoking during a visit.

- Ask patients if they use tobacco products and advise them to quit.

CDC offers resources and tools to help providers start the conversation about tobacco and quitting.

States and communities can:

- Fund state tobacco control programs at the level CDC recommends.

- Work to limit tobacco product advertising.

- Use science-based strategies to prevent and reduce tobacco use. For example, states and communities can increase tobacco prices, conduct hard-hitting media campaigns, adopt comprehensive smoke-free laws, require licenses for tobacco sellers, and limit where tobacco products can be sold.

- Provide barrier-free access to treatments proven to help people quit.

If everyone works together to keep youth safe from the harms of tobacco use, we can move further toward a healthier, smokefree world.

Quitting resources for youth

In 2019, more than half of U.S. young people who reported currently using tobacco products said they were seriously thinking about quitting. Quitting as soon as possible is the healthiest choice for mind and body.

State quitlines can connect people to resources like text support, counseling, and web-based chat. People who want to quit can call 1-800-QUIT-NOW to find out what their state offers. Quitlines are also available in Spanish, Chinese (Cantonese and Mandarin), Korean, and Vietnamese.

- 1-855-DÉJELO-YA (Spanish)

- 1-800-838-8917 (Cantonese & Mandarin)

- 1-800-556-5564 (Korean)

- 1-800-778-8440 (Vietnamese)

SmokefreeTXT for Teens is a free mobile text messaging program for youth aged 13 to 19.

The quitSTART phone app offers custom tips, inspiration, and challenges.

Quitting resources for adults

At any age, it's never too late to quit. U.S. adults who want to quit can call 1-800-QUIT-NOW or

- 1-800-838-8917 (Cantonese and Mandarin)

They can also visit CDC.gov/Quit or Smokefree.gov to sign up for texting programs and download mobile apps.

Smoking and Tobacco Use

Commercial tobacco use is the leading cause of preventable disease, disability, and death in the United States.

For Everyone

Health care providers, public health.

Warning: The NCBI web site requires JavaScript to function. more...

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US); 2012.

Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General.

1 introduction, summary, and conclusions.

- Introduction

Tobacco use is a global epidemic among young people. As with adults, it poses a serious health threat to youth and young adults in the United States and has significant implications for this nation’s public and economic health in the future ( Perry et al. 1994 ; Kessler 1995 ). The impact of cigarette smoking and other tobacco use on chronic disease, which accounts for 75% of American spending on health care ( Anderson 2010 ), is well-documented and undeniable. Although progress has been made since the first Surgeon General’s report on smoking and health in 1964 ( U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare [USDHEW] 1964 ), nearly one in four high school seniors is a current smoker. Most young smokers become adult smokers. One-half of adult smokers die prematurely from tobacco-related diseases ( Fagerström 2002 ; Doll et al. 2004 ). Despite thousands of programs to reduce youth smoking and hundreds of thousands of media stories on the dangers of tobacco use, generation after generation continues to use these deadly products, and family after family continues to suffer the devastating consequences. Yet a robust science base exists on social, biological, and environmental factors that influence young people to use tobacco, the physiology of progression from experimentation to addiction, other health effects of tobacco use, the epidemiology of youth and young adult tobacco use, and evidence-based interventions that have proven effective at reducing both initiation and prevalence of tobacco use among young people. Those are precisely the issues examined in this report, which aims to support the application of this robust science base.

Nearly all tobacco use begins in childhood and adolescence ( U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS] 1994 ). In all, 88% of adult smokers who smoke daily report that they started smoking by the age of 18 years (see Chapter 3 , “The Epidemiology of Tobacco Use Among Young People in the United States and Worldwide”). This is a time in life of great vulnerability to social influences ( Steinberg 2004 ), such as those offered through the marketing of tobacco products and the modeling of smoking by attractive role models, as in movies ( Dalton et al. 2009 ), which have especially strong effects on the young. This is also a time in life of heightened sensitivity to normative influences: as tobacco use is less tolerated in public areas and there are fewer social or regular users of tobacco, use decreases among youth ( Alesci et al. 2003 ). And so, as we adults quit, we help protect our children.

Cigarettes are the only legal consumer products in the world that cause one-half of their long-term users to die prematurely ( Fagerström 2002 ; Doll et al. 2004 ). As this epidemic continues to take its toll in the United States, it is also increasing in low- and middle-income countries that are least able to afford the resulting health and economic consequences ( Peto and Lopez 2001 ; Reddy et al. 2006 ). It is past time to end this epidemic. To do so, primary prevention is required, for which our focus must be on youth and young adults. As noted in this report, we now have a set of proven tools and policies that can drastically lower youth initiation and use of tobacco products. Fully committing to using these tools and executing these policies consistently and aggressively is the most straight forward and effective to making future generations tobacco-free.

The 1994 Surgeon General’s Report

This Surgeon General’s report on tobacco is the second to focus solely on young people since these reports began in 1964. Its main purpose is to update the science of smoking among youth since the first comprehensive Surgeon General’s report on tobacco use by youth, Preventing Tobacco Use Among Young People , was published in 1994 ( USDHHS 1994 ). That report concluded that if young people can remain free of tobacco until 18 years of age, most will never start to smoke. The report documented the addiction process for young people and how the symptoms of addiction in youth are similar to those in adults. Tobacco was also presented as a gateway drug among young people, because its use generally precedes and increases the risk of using illicit drugs. Cigarette advertising and promotional activities were seen as a potent way to increase the risk of cigarette smoking among young people, while community-wide efforts were shown to have been successful in reducing tobacco use among youth. All of these conclusions remain important, relevant, and accurate, as documented in the current report, but there has been considerable research since 1994 that greatly expands our knowledge about tobacco use among youth, its prevention, and the dynamics of cessation among young people. Thus, there is a compelling need for the current report.

Tobacco Control Developments

Since 1994, multiple legal and scientific developments have altered the tobacco control environment and thus have affected smoking among youth. The states and the U.S. Department of Justice brought lawsuits against cigarette companies, with the result that many internal documents of the tobacco industry have been made public and have been analyzed and introduced into the science of tobacco control. Also, the 1998 Master Settlement Agreement with the tobacco companies resulted in the elimination of billboard and transit advertising as well as print advertising that directly targeted underage youth and limitations on the use of brand sponsorships ( National Association of Attorneys General [NAAG] 1998 ). This settlement also created the American Legacy Foundation, which implemented a nationwide antismoking campaign targeting youth. In 2009, the U.S. Congress passed a law that gave the U.S. Food and Drug Administration authority to regulate tobacco products in order to promote the public’s health ( Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act 2009 ). Certain tobacco companies are now subject to regulations limiting their ability to market to young people. In addition, they have had to reimburse state governments (through agreements made with some states and the Master Settlement Agreement) for some health care costs. Due in part to these changes, there was a decrease in tobacco use among adults and among youth following the Master Settlement Agreement, which is documented in this current report.

Recent Surgeon General Reports Addressing Youth Issues

Other reports of the Surgeon General since 1994 have also included major conclusions that relate to tobacco use among youth ( Office of the Surgeon General 2010 ). In 1998, the report focused on tobacco use among U.S. racial/ethnic minority groups ( USDHHS 1998 ) and noted that cigarette smoking among Black and Hispanic youth increased in the 1990s following declines among all racial/ethnic groups in the 1980s; this was particularly notable among Black youth, and culturally appropriate interventions were suggested. In 2000, the report focused on reducing tobacco use ( USDHHS 2000b ). A major conclusion of that report was that school-based interventions, when implemented with community- and media-based activities, could reduce or postpone the onset of smoking among adolescents by 20–40%. That report also noted that effective regulation of tobacco advertising and promotional activities directed at young people would very likely reduce the prevalence and onset of smoking. In 2001, the Surgeon General’s report focused on women and smoking ( USDHHS 2001 ). Besides reinforcing much of what was discussed in earlier reports, this report documented that girls were more affected than boys by the desire to smoke for the purpose of weight control. Given the ongoing obesity epidemic ( Bonnie et al. 2007 ), the current report includes a more extensive review of research in this area.

The 2004 Surgeon General’s report on the health consequences of smoking ( USDHHS 2004 ) concluded that there is sufficient evidence to infer that a causal relationship exists between active smoking and (a) impaired lung growth during childhood and adolescence; (b) early onset of decline in lung function during late adolescence and early adulthood; (c) respiratory signs and symptoms in children and adolescents, including coughing, phlegm, wheezing, and dyspnea; and (d) asthma-related symptoms (e.g., wheezing) in childhood and adolescence. The 2004 Surgeon General’s report further provided evidence that cigarette smoking in young people is associated with the development of atherosclerosis.

The 2010 Surgeon General’s report on the biology of tobacco focused on the understanding of biological and behavioral mechanisms that might underlie the pathogenicity of tobacco smoke ( USDHHS 2010 ). Although there are no specific conclusions in that report regarding adolescent addiction, it does describe evidence indicating that adolescents can become dependent at even low levels of consumption. Two studies ( Adriani et al. 2003 ; Schochet et al. 2005 ) referenced in that report suggest that because the adolescent brain is still developing, it may be more susceptible and receptive to nicotine than the adult brain.

Scientific Reviews

Since 1994, several scientific reviews related to one or more aspects of tobacco use among youth have been undertaken that also serve as a foundation for the current report. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) ( Lynch and Bonnie 1994 ) released Growing Up Tobacco Free: Preventing Nicotine Addiction in Children and Youths, a report that provided policy recommendations based on research to that date. In 1998, IOM provided a white paper, Taking Action to Reduce Tobacco Use, on strategies to reduce the increasing prevalence (at that time) of smoking among young people and adults. More recently, IOM ( Bonnie et al. 2007 ) released a comprehensive report entitled Ending the Tobacco Problem: A Blueprint for the Nation . Although that report covered multiple potential approaches to tobacco control, not just those focused on youth, it characterized the overarching goal of reducing smoking as involving three distinct steps: “reducing the rate of initiation of smoking among youth (IOM [ Lynch and Bonnie] 1994 ), reducing involuntary tobacco smoke exposure ( National Research Council 1986 ), and helping people quit smoking” (p. 3). Thus, reducing onset was seen as one of the primary goals of tobacco control.

As part of USDHHS continuing efforts to assess the health of the nation, prevent disease, and promote health, the department released, in 2000, Healthy People 2010 and, in 2010, Healthy People 2020 ( USDHHS 2000a , 2011 ). Healthy People provides science-based, 10-year national objectives for improving the health of all Americans. For 3 decades, Healthy People has established benchmarks and monitored progress over time in order to encourage collaborations across sectors, guide individuals toward making informed health decisions, and measure the impact of prevention activities. Each iteration of Healthy People serves as the nation’s disease prevention and health promotion roadmap for the decade. Both Healthy People 2010 and Healthy People 2020 highlight “Tobacco Use” as one of the nation’s “Leading Health Indicators,” feature “Tobacco Use” as one of its topic areas, and identify specific measurable tobacco-related objectives and targets for the nation to strive for. Healthy People 2010 and Healthy People 2020 provide tobacco objectives based on the most current science and detailed population-based data to drive action, assess tobacco use among young people, and identify racial and ethnic disparities. Additionally, many of the Healthy People 2010 and 2020 tobacco objectives address reductions of tobacco use among youth and target decreases in tobacco advertising in venues most often influencing young people. A complete list of the healthy people 2020 objectives can be found on their Web site ( USDHHS 2011 ).

In addition, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) of the National Institutes of Health has published monographs pertinent to the topic of tobacco use among youth. In 2001, NCI published Monograph 14, Changing Adolescent Smoking Prevalence , which reviewed data on smoking among youth in the 1990s, highlighted important statewide intervention programs, presented data on the influence of marketing by the tobacco industry and the pricing of cigarettes, and examined differences in smoking by racial/ethnic subgroup ( NCI 2001 ). In 2008, NCI published Monograph 19, The Role of the Media in Promoting and Reducing Tobacco Use ( NCI 2008 ). Although young people were not the sole focus of this Monograph, the causal relationship between tobacco advertising and promotion and increased tobacco use, the impact on youth of depictions of smoking in movies, and the success of media campaigns in reducing youth tobacco use were highlighted as major conclusions of the report.

The Community Preventive Services Task Force (2011) provides evidence-based recommendations about community preventive services, programs, and policies on a range of topics including tobacco use prevention and cessation ( Task Force on Community Preventive Services 2001 , 2005 ). Evidence reviews addressing interventions to reduce tobacco use initiation and restricting minors’ access to tobacco products were cited and used to inform the reviews in the current report. The Cochrane Collaboration (2010) has also substantially contributed to the review literature on youth and tobacco use by producing relevant systematic assessments of health-related programs and interventions. Relevant to this Surgeon General’s report are Cochrane reviews on interventions using mass media ( Sowden 1998 ), community interventions to prevent smoking ( Sowden and Stead 2003 ), the effects of advertising and promotional activities on smoking among youth ( Lovato et al. 2003 , 2011 ), preventing tobacco sales to minors ( Stead and Lancaster 2005 ), school-based programs ( Thomas and Perara 2006 ), programs for young people to quit using tobacco ( Grimshaw and Stanton 2006 ), and family programs for preventing smoking by youth ( Thomas et al. 2007 ). These reviews have been cited throughout the current report when appropriate.

In summary, substantial new research has added to our knowledge and understanding of tobacco use and control as it relates to youth since the 1994 Surgeon General’s report, including updates and new data in subsequent Surgeon General’s reports, in IOM reports, in NCI Monographs, and in Cochrane Collaboration reviews, in addition to hundreds of peer-reviewed publications, book chapters, policy reports, and systematic reviews. Although this report is a follow-up to the 1994 report, other important reviews have been undertaken in the past 18 years and have served to fill the gap during an especially active and important time in research on tobacco control among youth.

- Focus of the Report

Young People

This report focuses on “young people.” In general, work was reviewed on the health consequences, epidemiology, etiology, reduction, and prevention of tobacco use for those in the young adolescent (11–14 years of age), adolescent (15–17 years of age), and young adult (18–25 years of age) age groups. When possible, an effort was made to be specific about the age group to which a particular analysis, study, or conclusion applies. Because hundreds of articles, books, and reports were reviewed, however, there are, unavoidably, inconsistencies in the terminology used. “Adolescents,” “children,” and “youth” are used mostly interchangeably throughout this report. In general, this group encompasses those 11–17 years of age, although “children” is a more general term that will include those younger than 11 years of age. Generally, those who are 18–25 years old are considered young adults (even though, developmentally, the period between 18–20 years of age is often labeled late adolescence), and those 26 years of age or older are considered adults.

In addition, it is important to note that the report is concerned with active smoking or use of smokeless tobacco on the part of the young person. The report does not consider young people’s exposure to secondhand smoke, also referred to as involuntary or passive smoking, which was discussed in the 2006 report of the Surgeon General ( USDHHS 2006 ). Additionally, the report does not discuss research on children younger than 11 years old; there is very little evidence of tobacco use in the United States by children younger than 11 years of age, and although there may be some predictors of later tobacco use in those younger years, the research on active tobacco use among youth has been focused on those 11 years of age and older.

Tobacco Use

Although cigarette smoking is the most common form of tobacco use in the United States, this report focuses on other forms as well, such as using smokeless tobacco (including chew and snuff) and smoking a product other than a cigarette, such as a pipe, cigar, or bidi (tobacco wrapped in tendu leaves). Because for young people the use of one form of tobacco has been associated with use of other tobacco products, it is particularly important to monitor all forms of tobacco use in this age group. The term “tobacco use” in this report indicates use of any tobacco product. When the word “smoking” is used alone, it refers to cigarette smoking.

- Organization of the Report