Scriptwriting

Ai generator.

Behind every movie that you have seen and every theater play that you have attended, there is a pad of paper that refers to the detailed outline of the story being portrayed. This group of sheets is what we call “script.” Though watching your favorite comedy show entertains you, most of them have scriptwriting that is no joke. In this article, we are going to discuss the basic principles and nature of writing a script. Read through and be the scriptwriter of the next phenomenal movie.

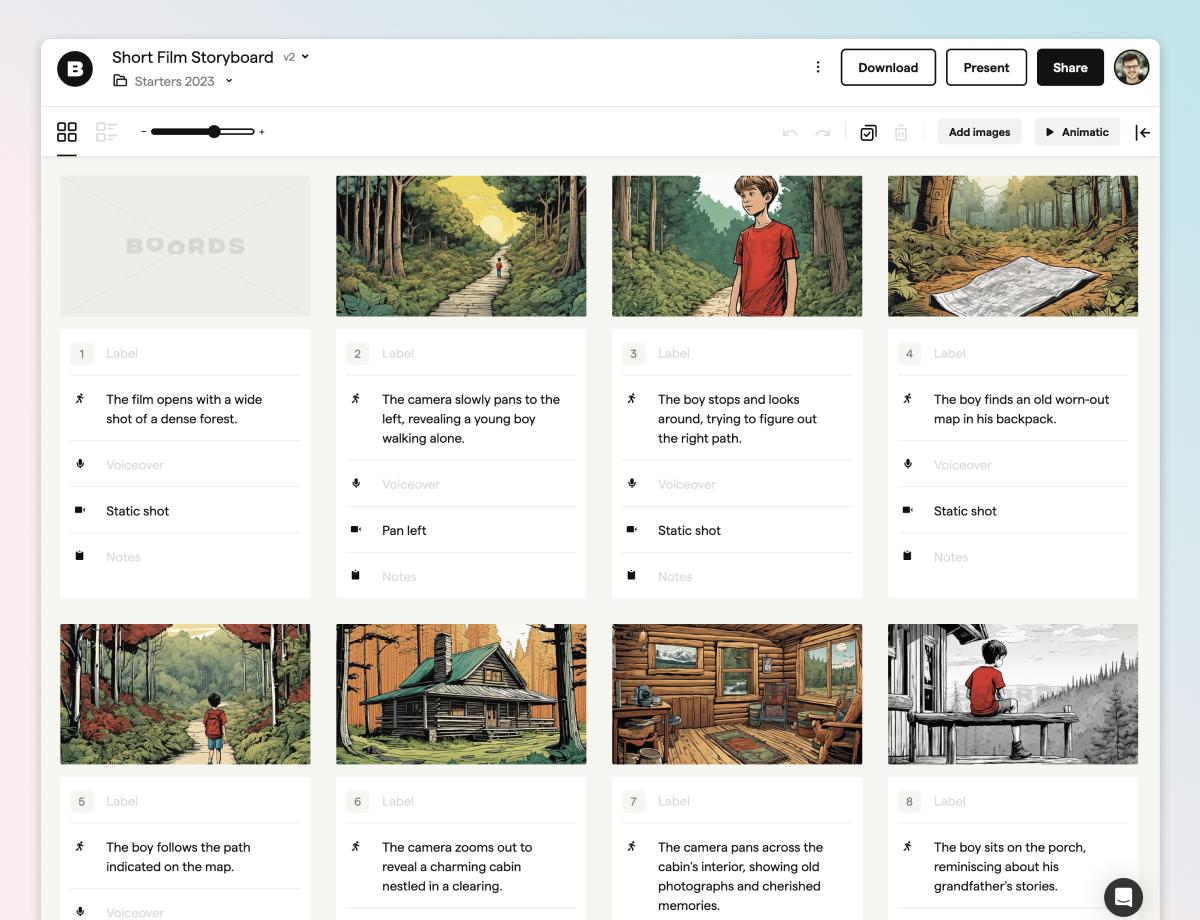

A script (also known as a screenplay ) creates a outline of the whole story to be acted out by actors for a film, a stage play, a television program example , etc. Aside from the dialogue, also narrates the actions, expressions, and movements of the characters (i.e. actors). If you haven’t seen a script before, this is now your chance. Here are some examples to let you have a glimpse of what they look like.

What is Scriptwriting? Scriptwriting, also known as screenwriting, is the process of writing the text or dialogue for a screenplay, which is a blueprint for a film, television show, play, or other visual storytelling medium. It is a specialized form of writing that focuses on creating a narrative structure, dialogue, and descriptions that guide actors, directors, and other crew members in bringing a story to life on screen or stage.

Scriptwriters, often called screenwriters, play a crucial role in the storytelling process for visual media. They are responsible for crafting the plot, developing characters, writing dialogue, and describing the settings and actions within a screenplay. A well-written script serves as the foundation for the entire production and helps translate the writer’s creative vision into a format that can be easily understood and executed by the cast and crew.

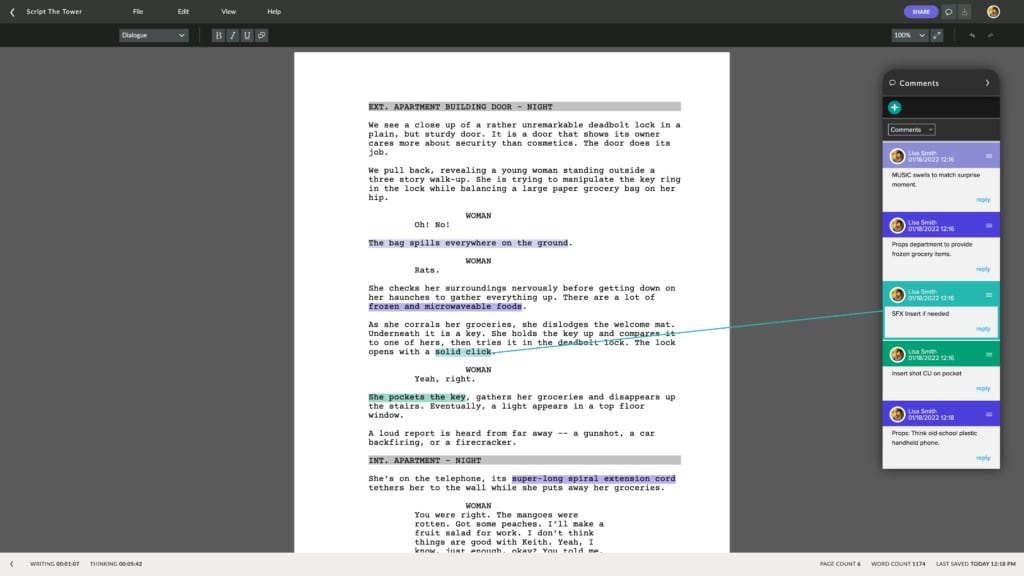

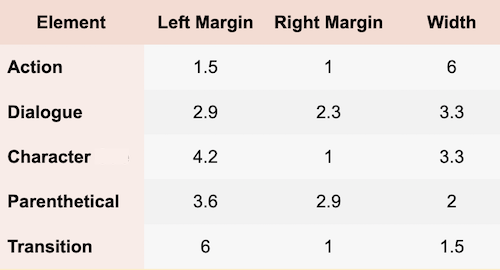

In screenwriting, there are specific formatting guidelines and industry standards that writers must follow to ensure clarity and consistency. Screenplays are typically divided into scenes, with each scene described in detail to convey the visual and auditory elements required for the production. Proper formatting and organization are essential for a script to be professional and practical for production.

Scriptwriting is a collaborative process, and screenwriters often work closely with directors, producers, and other creative professionals to refine and develop their scripts. The goal of scriptwriting is to create a compelling and engaging story that can be brought to life on screen, stage, or in other visual media.

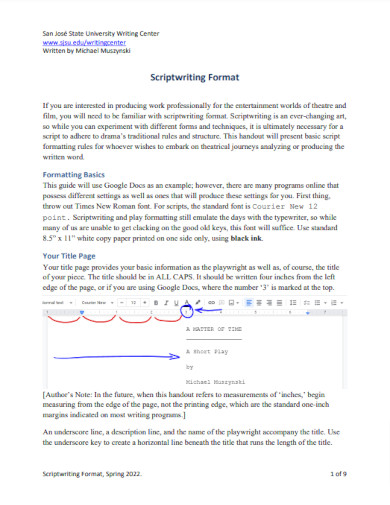

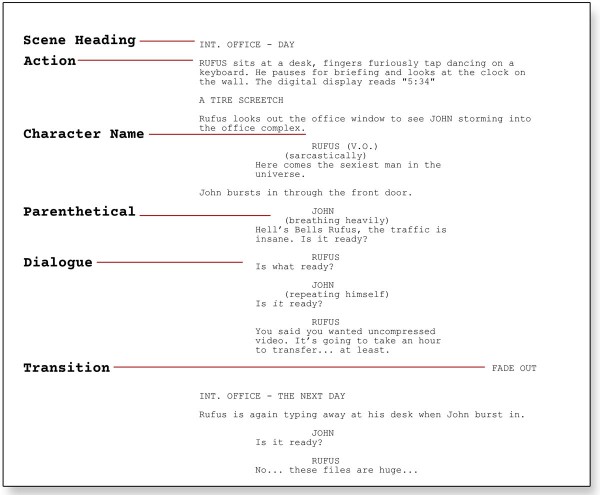

Script Writing Format

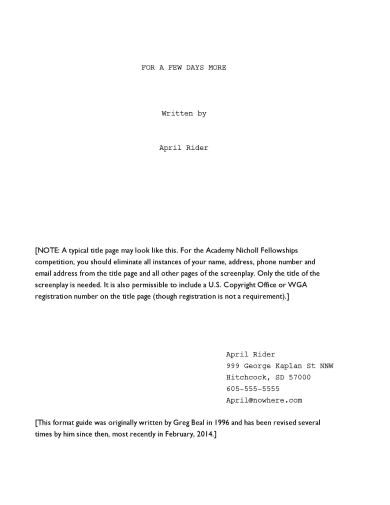

1. title page.

Title of the script : Centered and in capital letters. Written by : Beneath the title, also centered. Writer’s contact information : At the bottom left corner (optional).

2. Scene Heading (Slugline)

INT. or EXT. indicating whether the scene is interior or exterior. Location : A brief description of the setting. Time of Day : Usually DAY or NIGHT.

3. Action (Description)

Describes the setting, characters, and what is happening in the scene. Written in the present tense and only includes what can be seen or heard.

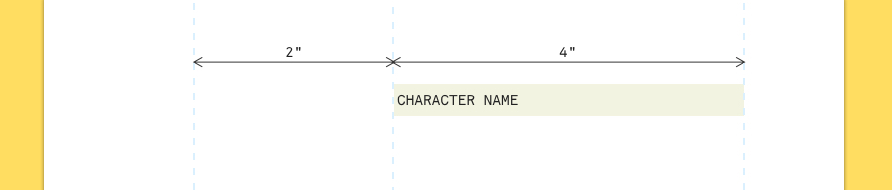

4. Character Name

When a character is introduced for the first time, their name should be in all caps. Above their dialogue, centered on the page.

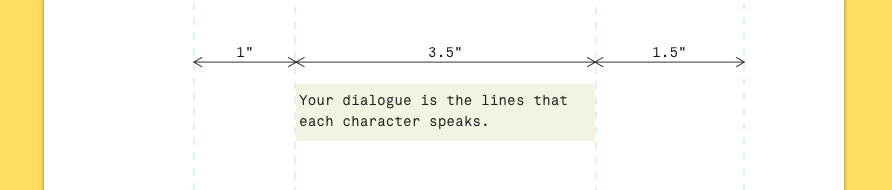

5. Dialogue

Underneath the character’s name, the dialogue is centered and enclosed in quotation marks. Keep dialogue lines concise for readability.

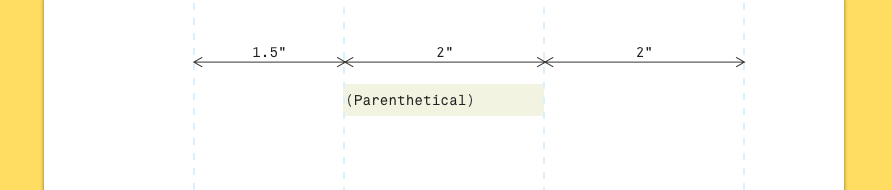

6. Parenthetical

Directions for actors (how they should say their lines) are placed in parentheses, just below the character’s name and before the dialogue. Use sparingly.

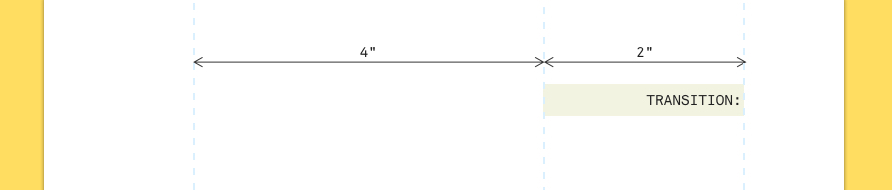

7. Transitions

Terms like CUT TO:, FADE IN:, FADE OUT., etc., are used to indicate changes between scenes. Typically aligned to the right of the page.

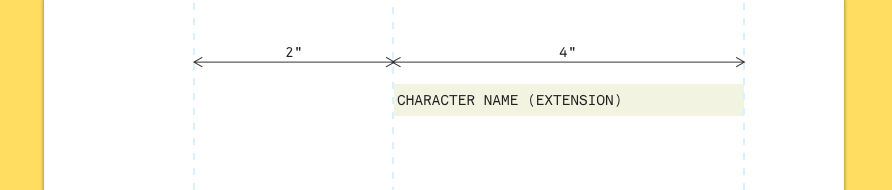

8. Extensions

Used next to character names to indicate off-screen (O.S.) or voice-over (V.O.) dialogue.

Formatting Specifications:

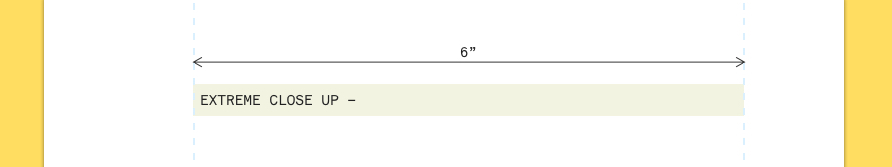

Font : 12-pt, Courier font is standard. Margins : Left margin 1.5 inches, right margin 1 inch (approx.), top and bottom margins 1 inch. Spacing : Dialogue is typically single-spaced, while action and scene descriptions are double-spaced.

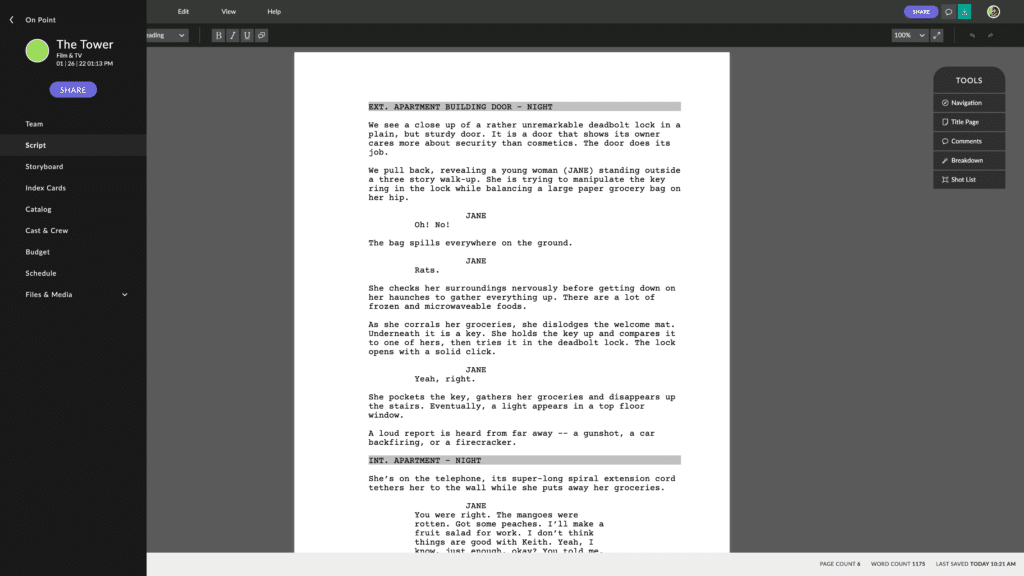

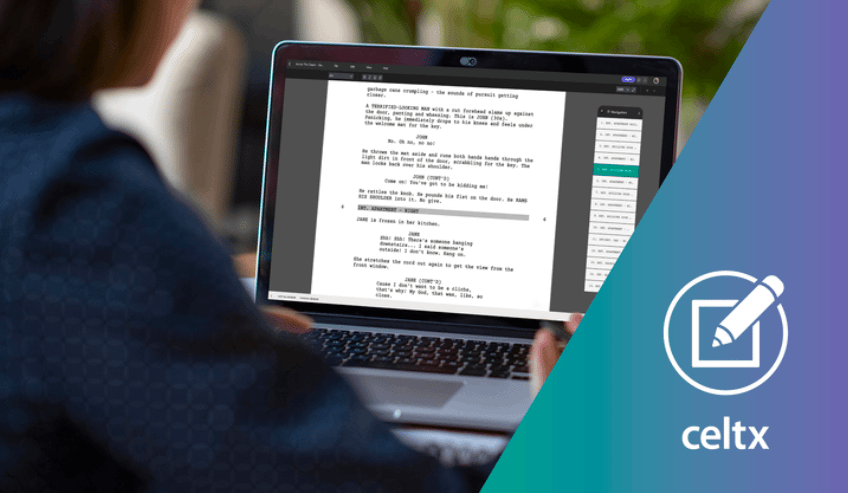

Many screenwriters use specialized software like Final Draft, Celtx, or WriterDuet, which automatically formats the script according to industry standards.

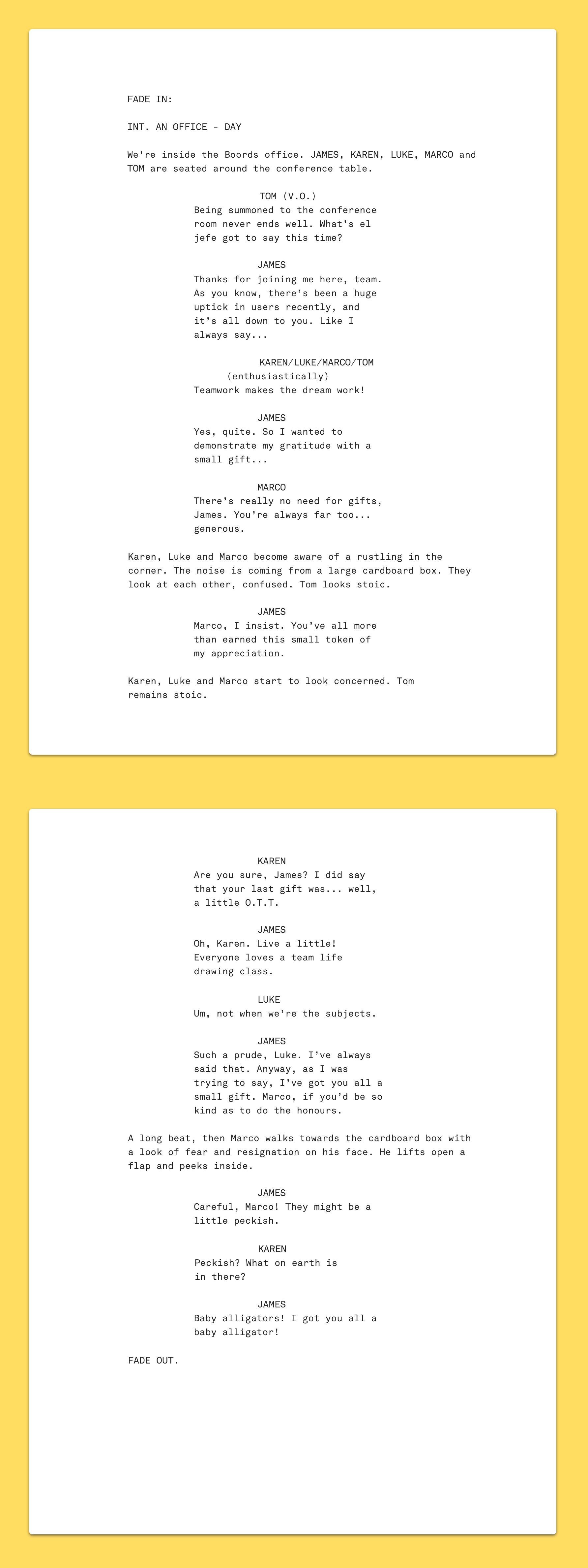

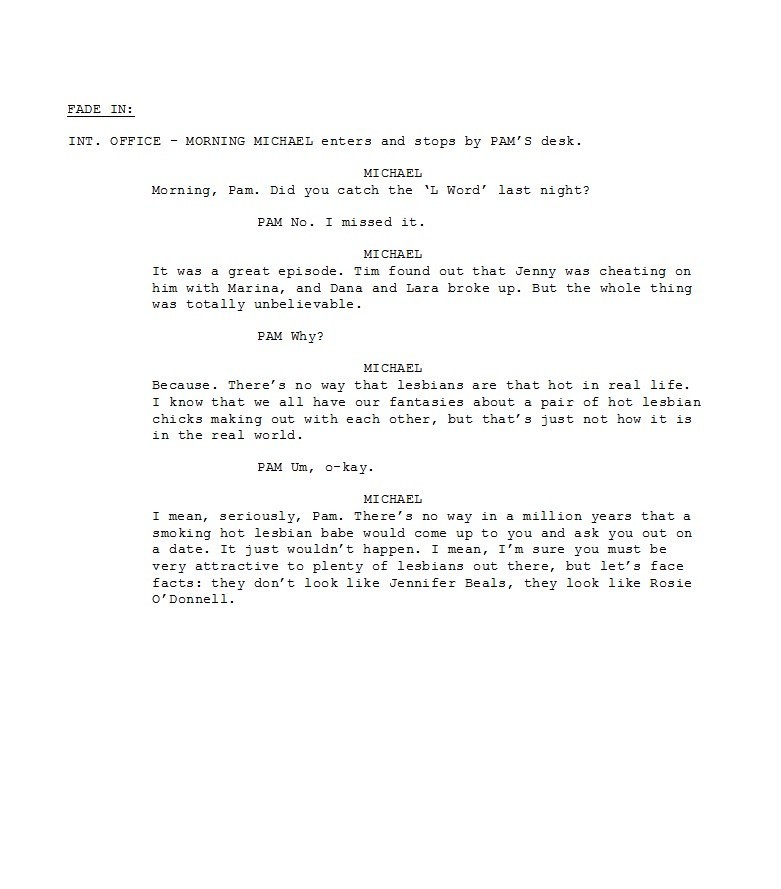

Example of Script Writing

Certainly! One of the best examples of scriptwriting is the opening scene from the classic film “Casablanca.” This scene is not only iconic but also showcases excellent scriptwriting in capturing the mood, character dynamics, and setting. Here’s a brief description of the scene:

Title : “Casablanca” – Opening Scene Scene : INT. RICK’S CAFÉ AMÉRICAIN – NIGHT The setting is Rick’s Café Américain, a bustling nightclub in the city of Casablanca during World War II. The atmosphere is smoky and filled with an eclectic mix of people, including refugees, expatriates, and shady characters. The hum of conversation and music creates a lively backdrop. Characters : RICK BLAINE, the enigmatic and sophisticated owner of the café, impeccably dressed. CARL, the affable and observant bartender. VICTOR LASZLO, a heroic resistance leader, and his companion ILSA LUND, an elegant woman with an air of mystery. Action : The camera pans across the café, highlighting the diverse patrons and their interactions. A jazz band plays in the background. Rick stands behind the bar, calmly observing the crowd, a half-smoked cigarette in his hand. Suddenly, Victor and Ilsa enter the café, drawing everyone’s attention. Victor is stoic, while Ilsa is both beautiful and anxious. Rick watches them closely, his demeanor unchanging. The band strikes up “La Marseillaise,” and the patrons join in, singing the French national anthem in a show of unity and resistance against the German occupiers. Rick’s eyes remain fixed on Victor and Ilsa, revealing a depth of emotion beneath his cool exterior.

Scriptwriting Examples & Samples

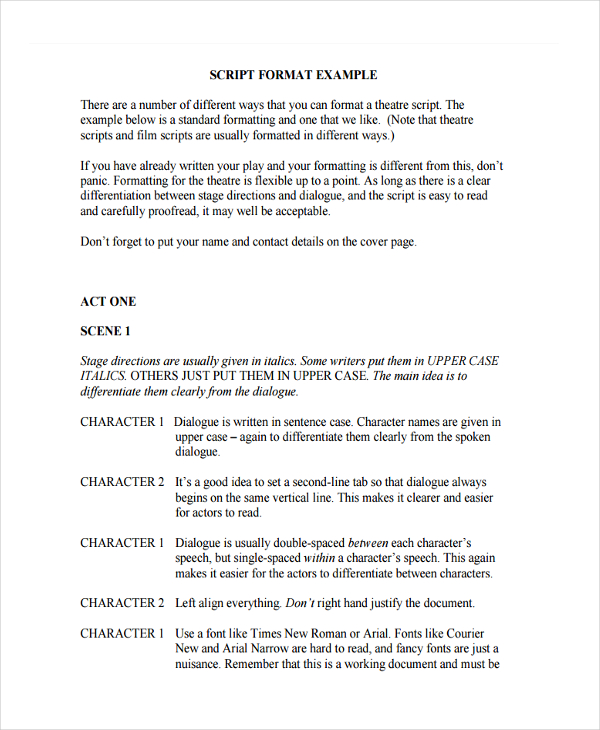

1. script writing format examples.

2. Script Writing Examples for Students

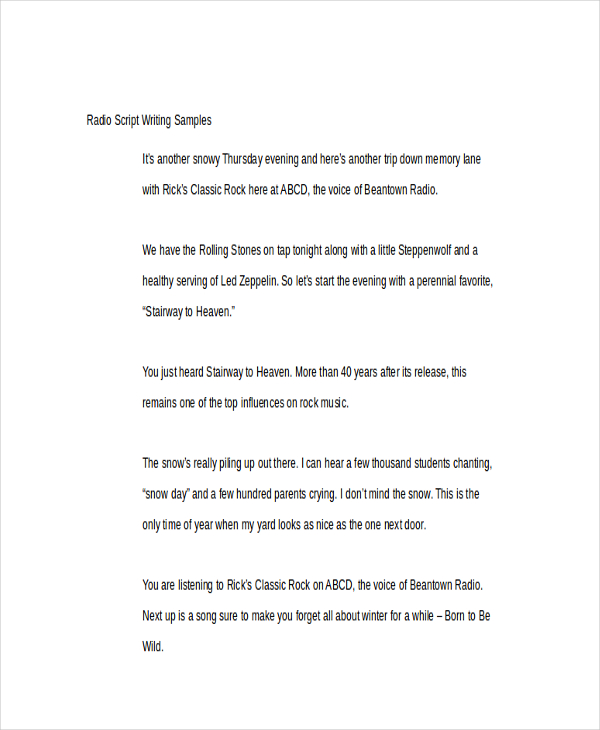

3. Radio Scriptwriting Examples

blog.musicradiocreative.com

4. Short Scriptwriting Examples

australianplays.org

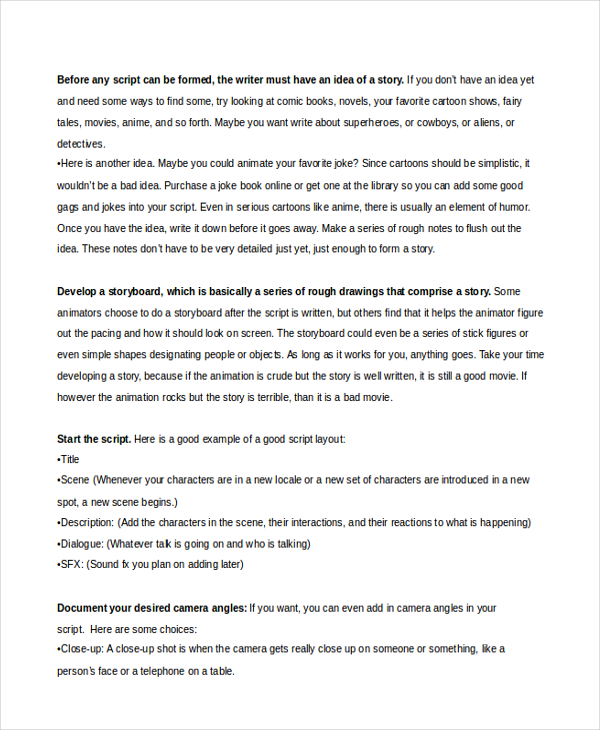

5. Cartoon Script Writing Examples

wikihow.com

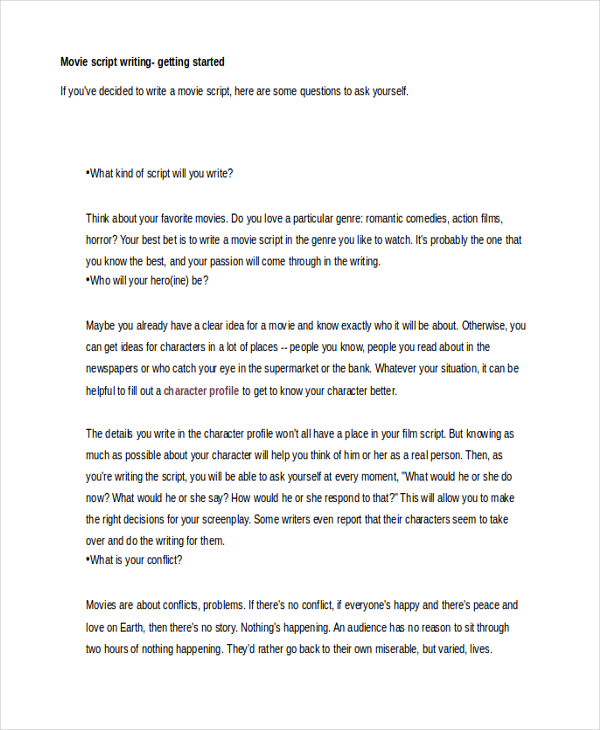

6. Movie Script Writing Examples

creative-writing-now.com

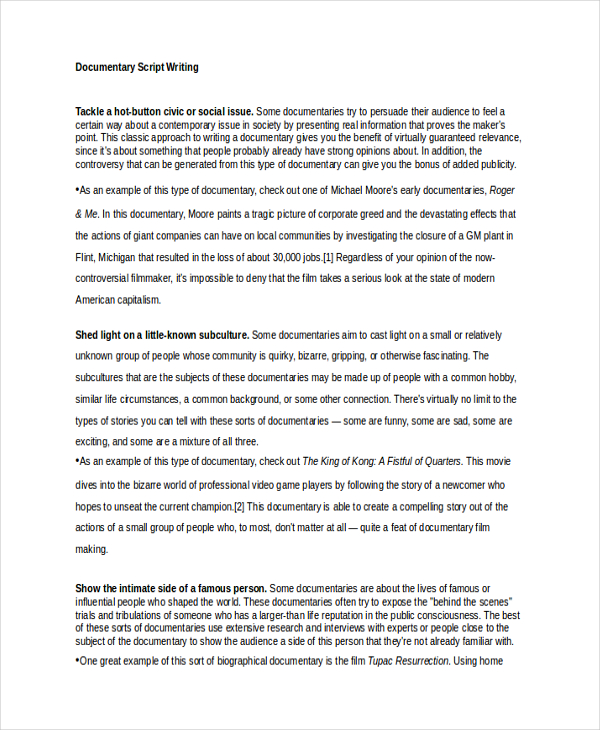

7. Documentary Script Writing Example

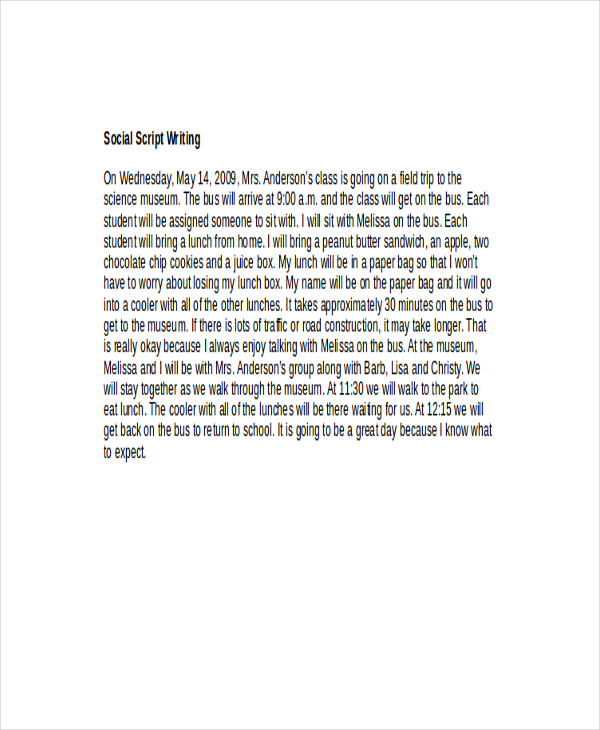

8. Social Script Writing Example

education.com

9. Story Script Writing Example

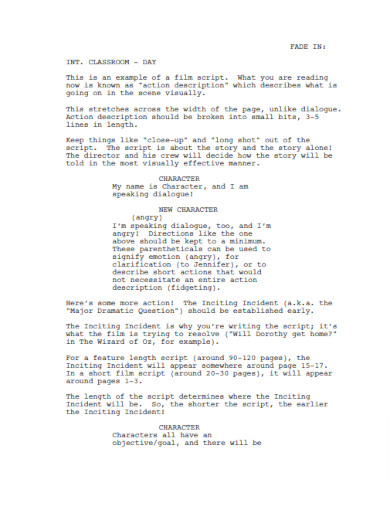

10. Screenplay Script Writing Example

wichita.edu

11. English Script Writing Example

okbjgm.weebly.com

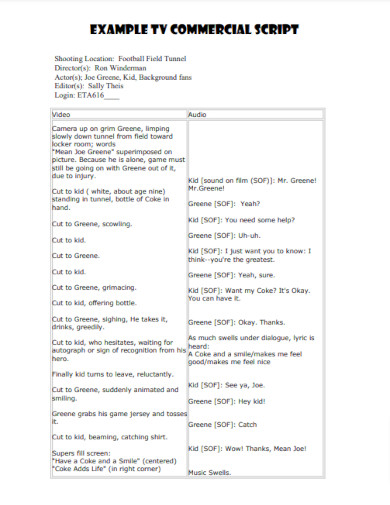

12. Commercial Script Writing Example

davidreiss.com

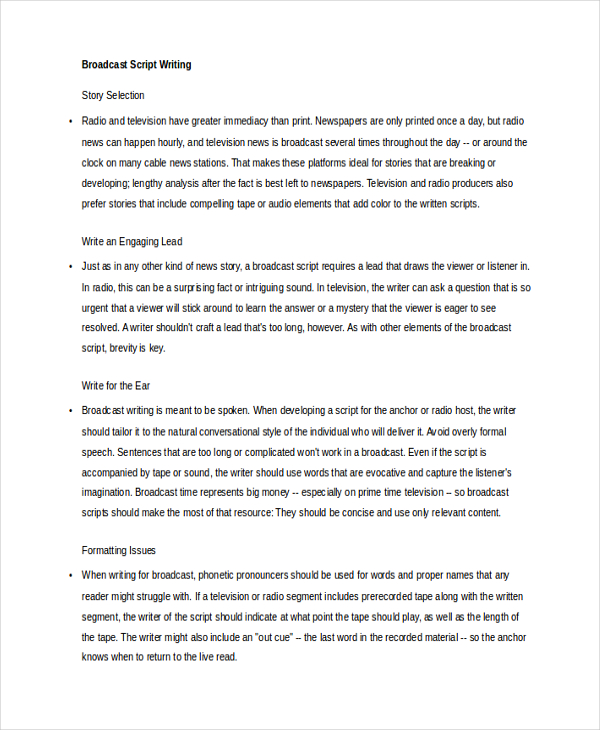

13. Broadcast Script Writing Example

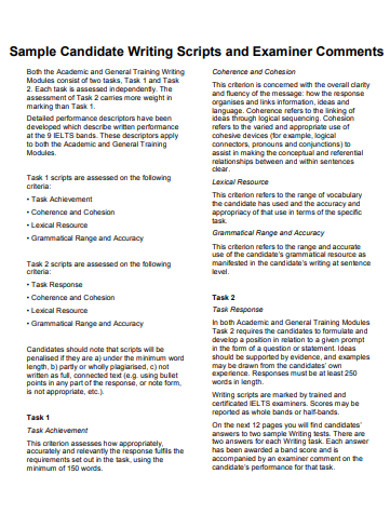

14. Sample Candidate Script Writing

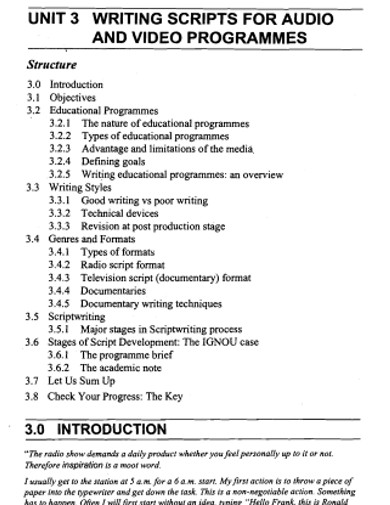

15. Beginner Program Script Writing Example

egyankosh.ac.in

16. Research Script Writing Example

eprints.usq.edu.au

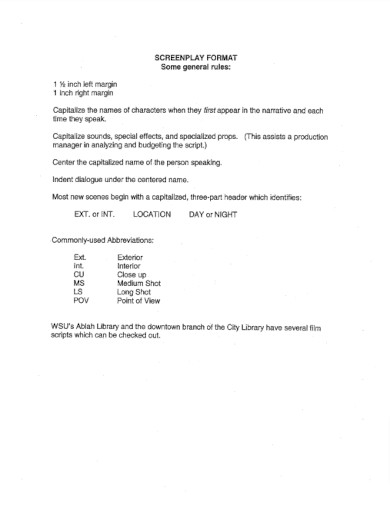

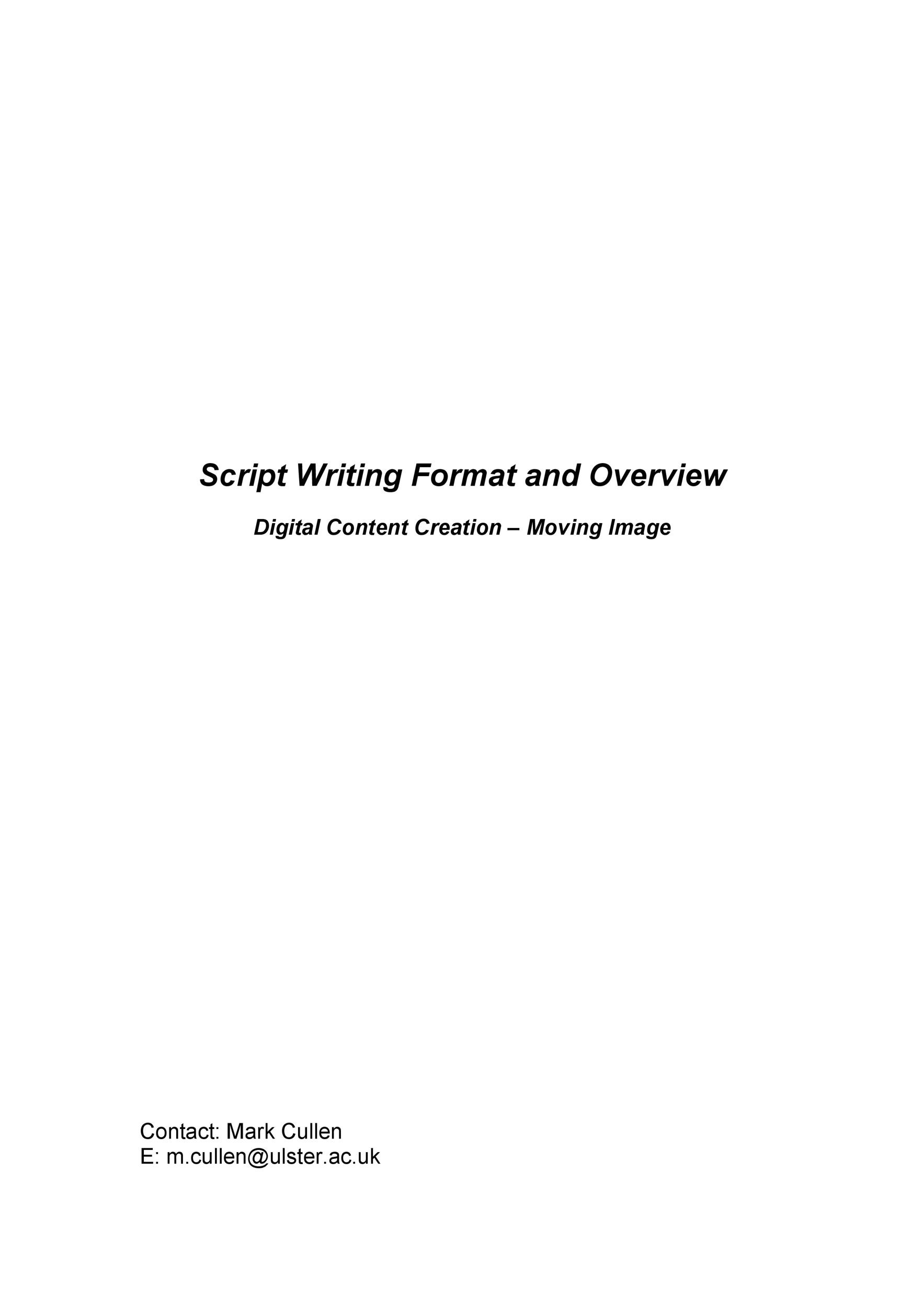

17. Script Writing Format Example

markycullen.com

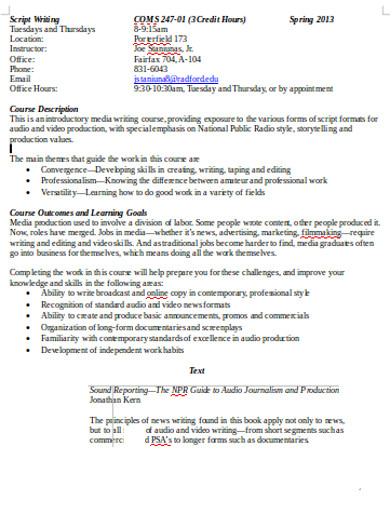

18. Script Writing in PDF

radford.edu

19. Professional Scriptwriting Example

20. Creative Scriptwriting Example

21. Scriptwriting Workshop Example

22. Screenplay Writing Format Example

downloads.bbc.co.uk

23. Short Films Scriptwriting Guide

filmg.co.uk

Importance of Script Writing

A script is a key tool used to ensure the success of the portrayal of a specific story. It also serves as a plan of the scenes to be portrayed by the actors, and script writing creates such a plan. Scriptwriting also showcases the talent of different scriptwriters in the field of mass media. Following a script minimizes the time intended to direct the actors on how to portray a certain character. Having the scenes planned beforehand lets the actors and directors focus more on the portrayal of the story, saving time and resources in the process.

Thus, script writing is considered as a fundamental process for the completion of a particular film or play.

How to Start Writing a Script

Let’s assume that you already have some marvelous scenes in your mind and you want to write them on papers. For sure, you would like to make a script that is as superb as the scenes itself, right? In writing your own screenplay, the beginning should be as competitive as your ending since it gives the judgment whether the audience stays or not. To give you a great start with your script composition, read this section before writing one.

1. Know what scripts are.

Just like any composition, the first thing you need to consider is to make sure that you really know what you are writing. In other words, it is indeed necessary to have an in-depth understanding of what scripts are and the technicalities behind it. You must also be aware that screenplays are not the work of a single man. In fact, there will be several people who would keep hold of your composition and edit or revise it accordingly. With this, writing will be not just easier but also clearer.

2. Get some inspiration.

3. sketch out your concept..

If you already have ideas and scenarios in your mind, drawing a sketch of all the details of your idea is the next thing you need to do. In any clean sheet of paper or board, make a comprehensible map pertaining to the necessary elements of your story such as the plot details, the personality traits of your characters and their relationship towards each other. Consider what techniques would you use in your screenplay, too. Moreover, take notes of the critical points of your story.

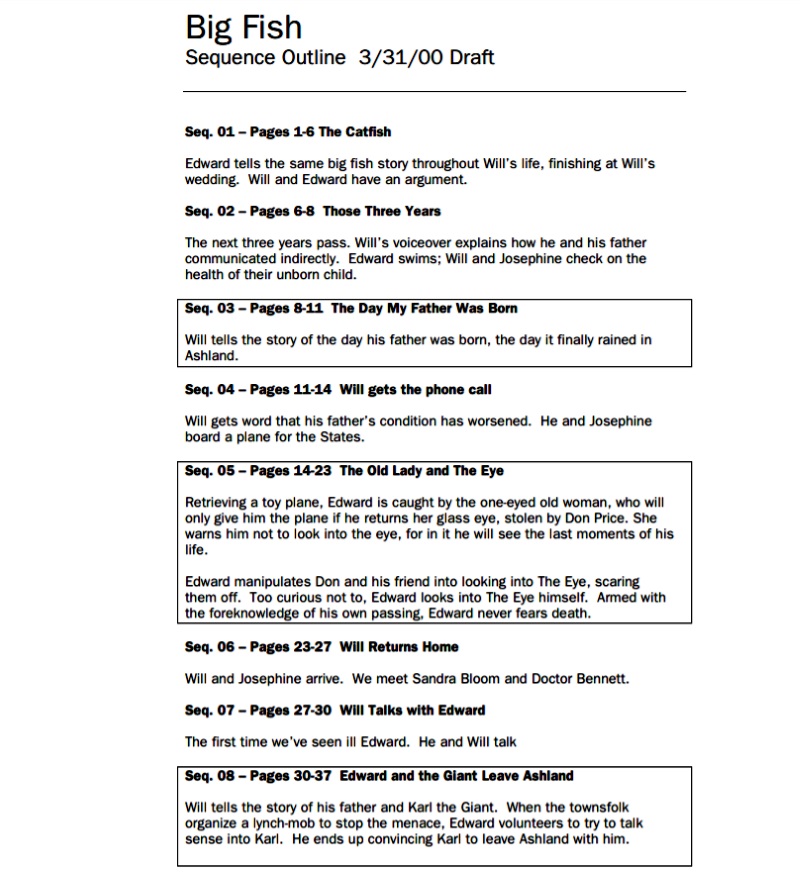

4. Create a story outline.

After crafting a sketch of your story, it is now time to turn it into an outline. In doing this, start with the basic run of your narrative and keep an eye on your story’s conflicts. Remember, conflicts are the lifeblood of stories. Also, start with details that are small but plays a big role in the story. Furthermore, in making the outline, consider the estimated length of your work. If you can make your story much concise, do it since long screenplays have less probability of being successful. In a standard script format, a page indicates a minute of screen time. Usually, dramas are 2-hours long while comedies are briefer which are about one and a half hours.

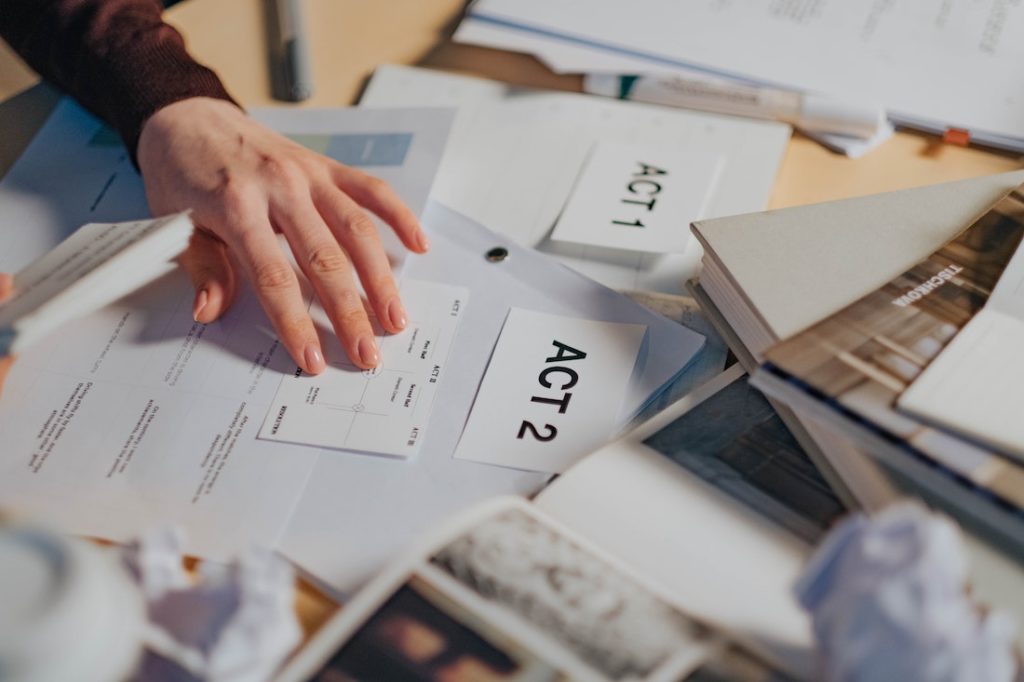

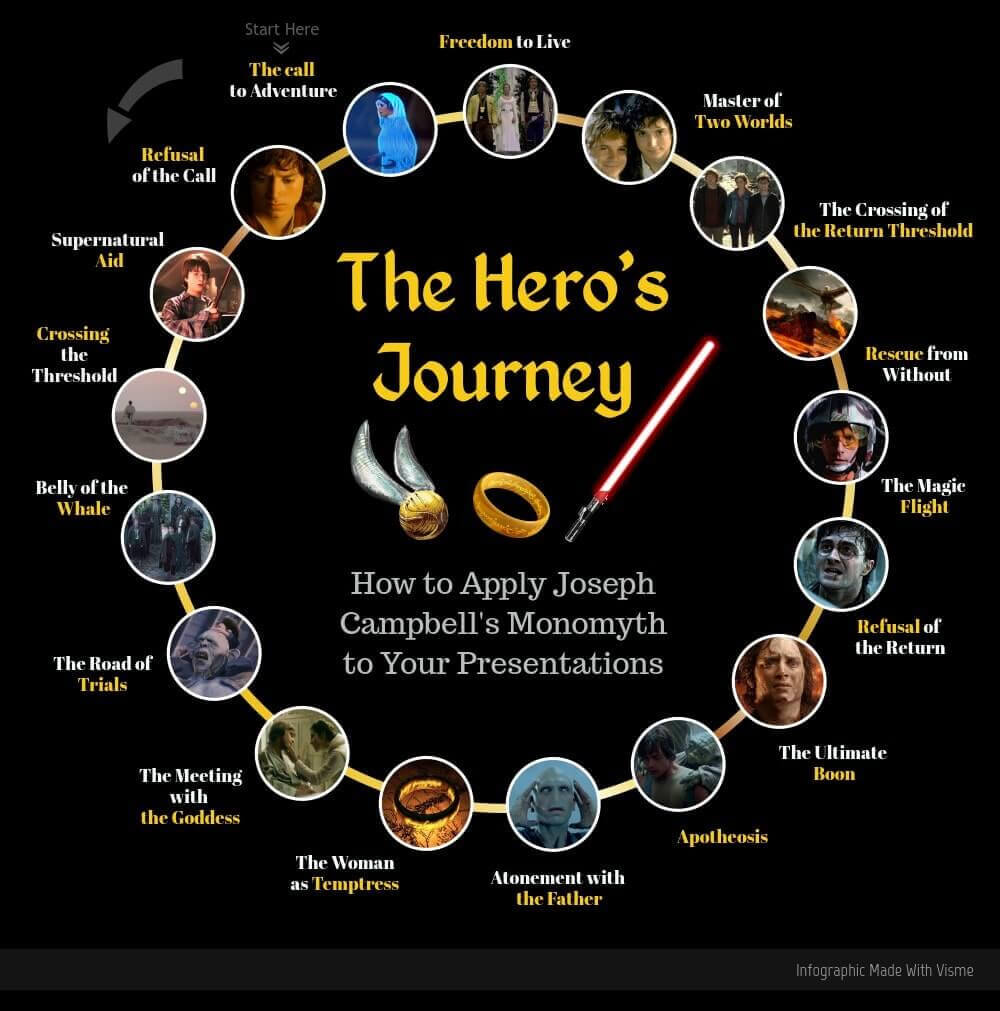

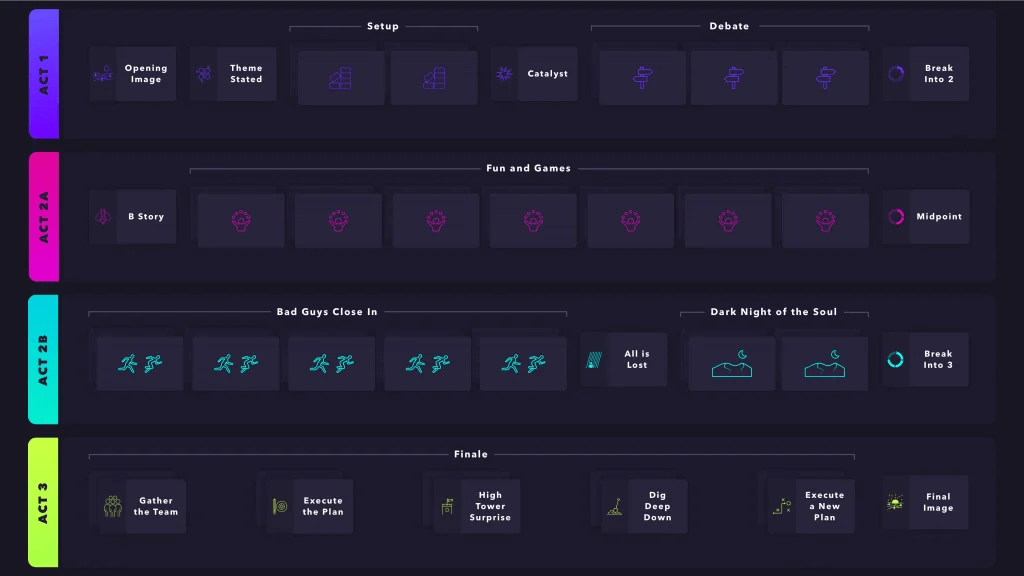

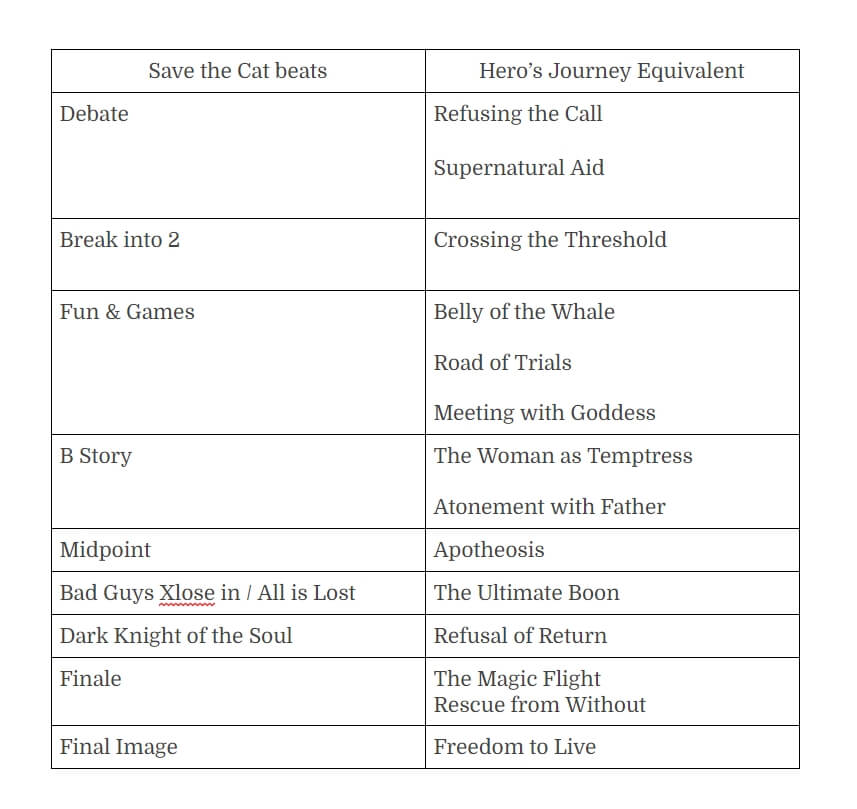

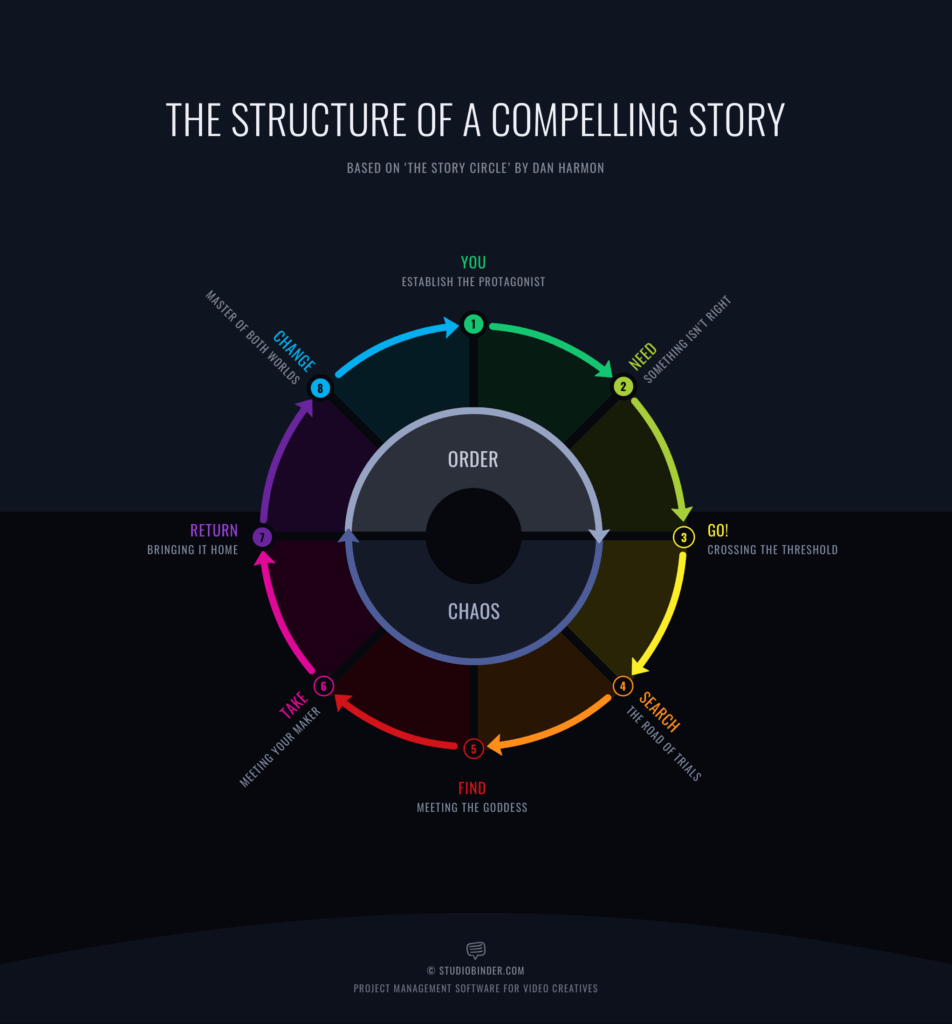

5. Divide your story into three acts.

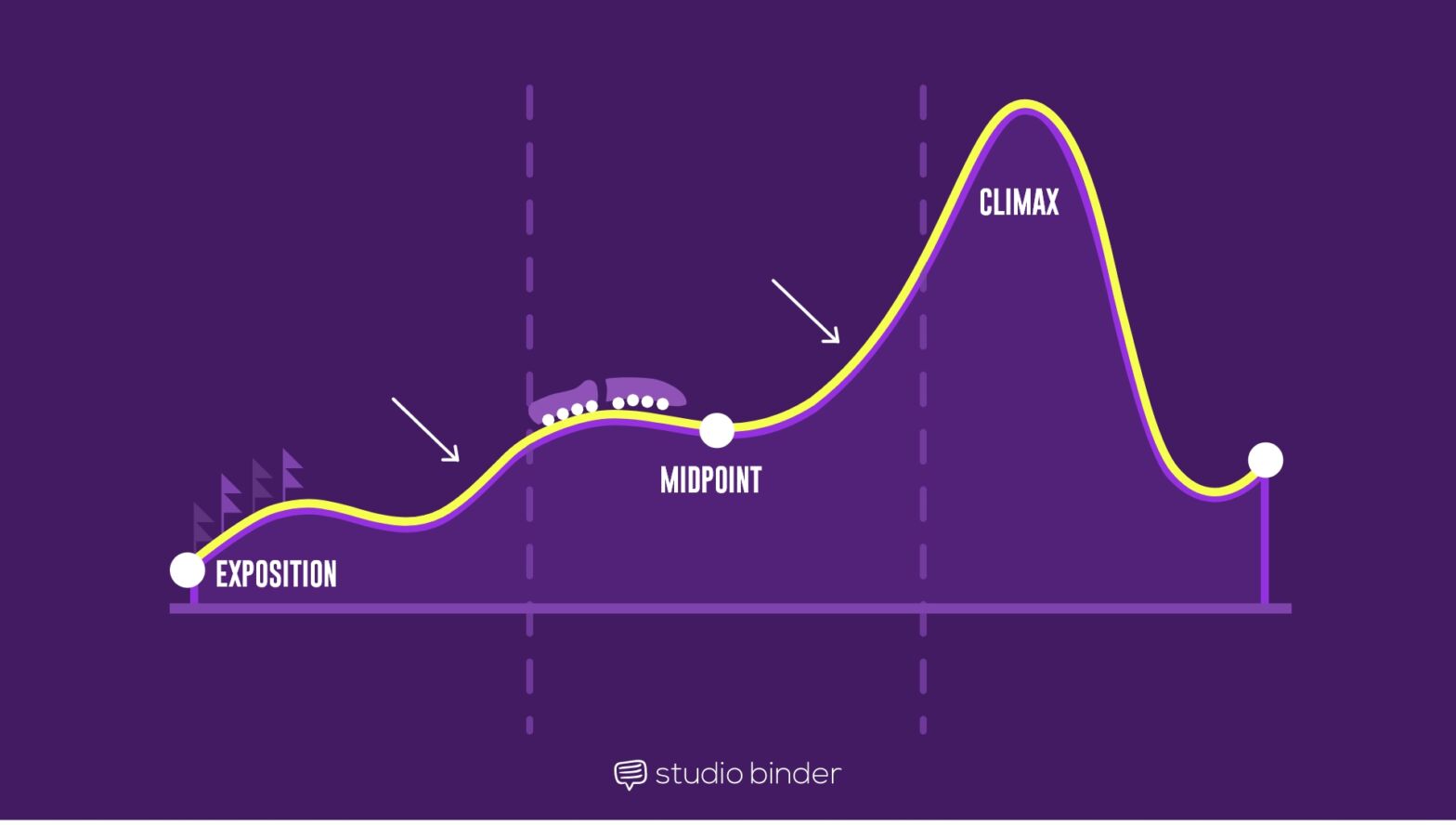

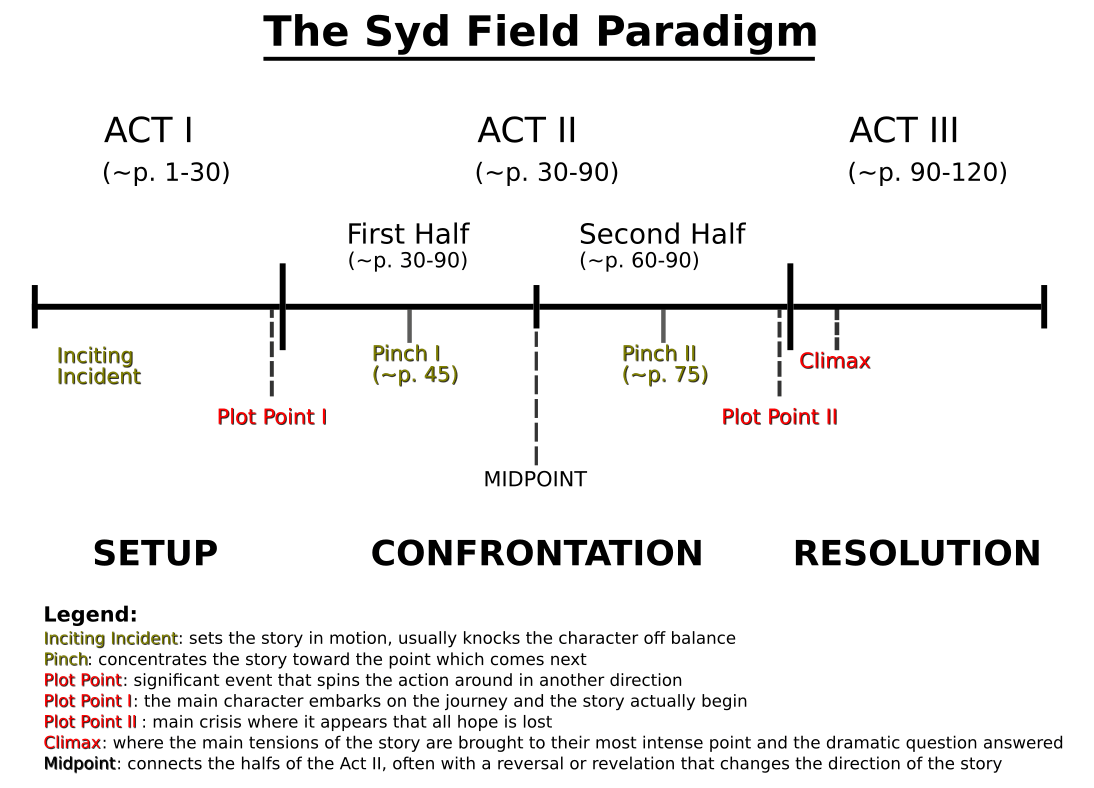

In a script, acts are defined as a set of scenes that creates an essential piece of the story. It is depicted by elements such as rising action, resolution, and climax. Usually, a story is comprised of five acts; however, several modern stories utilized the pillars of a screenplay, the Three Acts namely, the introduction, middle, and conclusion. Though each act can stand independently, it should also be considered that it should create the complete arc of the story when joined together.

After doing these five initial steps, you may now proceed to more technical procedures such as adding of sequence, dialogues, more specific scenes, etc.

How to Write a Good Screenplay

A good script describes the story in full detail, engages both the actors and directors and captivates the audience. Though it may be challenging at first, practicing to read more samples and educational articles pertaining to screenplay writing is extremely helpful. Allow yourself to compose the script of the next blockbuster movie by following these steps:

1. Learn the basics.

First of all, a scriptwriter can’t make a screenplay with creativity alone. Since the script is the manual of the film and is what the whole production follows, the writer should at least know the basic standards, terms, and technicalities in composing a script. In scriptwriting, knowledge is the gateway for the experience.

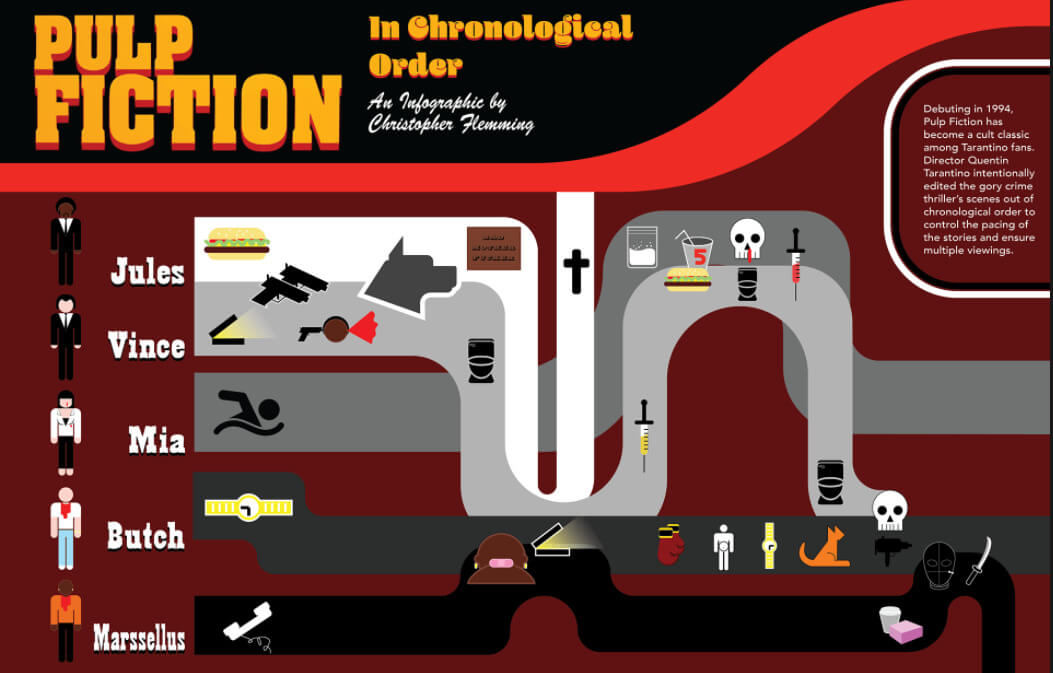

2. Read other movie scripts.

Scriptwriting has no standard contents but even just a reader, you can already identify which scripts could make it to the big screen. By scanning through the different scripts from various movies, you will be aware of what makes a script good or not. Furthermore, this will also give you a general idea on how the dialogue is developed, how the characters are portrayed, and how the story transitions from one scene to another.

3. Compose a draft.

Create a draft on the sequence of events and how the story progresses from the beginning. Write all the necessary plot details and create an outline of your story. In this step, it is alright for you to commit some erasures and alterations since it is still a draft. However, do your best to construct the initial picture of your entire movie concept already.

4. Split your story outline.

Divide the outline of your story into three acts. Act one is where you introduce the characters and their backstory. Act two is where the characters develop. Act three is where the characters experience the plot twists and conflicts, and where such conflicts are resolved.

5. Write the scenes and dialogues

There are two of the most important elements of the script. Scenes are the events of your story. Dialogues give your characters their voice. In this part, you can make an initial writing process of scenes by including all the interesting and relevant ideas you have. Nevertheless, in making your final script, see to it that all scenes are making important sense in the whole movie. If not then remove them.

6. Peer review

Though you can review or proofread your own work, it would still be a better choice to consult a friend that is knowledgeable in these matters. A friend may give you a few ideas on how to improve your story, peer review would be a more preferable option because basically, most of us cannot distinguish our own mistake. Moreover, be open to constructive criticisms, nobody is perfect, remember?

7. Polish your script

After a great discussion with your friend, you might spot any errors including the minimal ones. This is where you correct them. Also, you omit the unnecessary scenes that only confuse your audience and add a few details to your story as necessary. Revise your story as needed before producing the final screenplay.

In writing your screenplay, always remind yourself of the running time of your script. On average, a bankable movie runs from one hour and thirty minutes while short films take less than forty minutes in their screen time, including the credits.

Where to Read Scripts

Considering the rapid advancement of modern technology, the internet has been the extensive library of the scripts from different movies, plays, short films, etc. Nonetheless, the internet is a big place to search in; thus, it could still be a challenge for you to look for great references. Aside from this website, here is a list of sites from New York Film Academy for downloading and reading scripts from various media.

- IMSDB – Internet Movie Screenplay Database

- Go Into the Story

- Drew’s Script-o-Rama

- Simply Scripts

- Awesome Film

- Screenplays For You

- The Daily Script

- The Screenplay Database

- The Script Lab

- Movie Scripts and Screenplays

What are the six basic steps in writing a script?

1. concept and idea generation.

Start by brainstorming ideas and concepts for your script. What story do you want to tell, and what message or theme do you want to convey? Consider the genre, tone, and style of your script. It’s essential to have a clear vision of your story before moving forward.

2. Outline and Structure

Develop an outline that outlines the major plot points and structure of your script. Determine the acts, sequences, and scenes that will make up your story. Create a clear beginning, middle, and end to guide the narrative flow.

3. Character Development

Create well-rounded and relatable characters. Define their backgrounds, motivations, strengths, weaknesses, and arcs. Characters are at the heart of any script, and their actions and interactions drive the story.

4. Writing the Script

Start writing the script itself, following the appropriate industry formatting standards. Screenplays typically use specific formatting rules, including elements like scene headings, character names, dialogue, and action descriptions. Ensure your script is clear and easy to read.

5. Revisions and Polishing

Scriptwriting is often an iterative process. Review and revise your script multiple times. Pay attention to dialogue, pacing, character consistency, and plot logic. Seek feedback from others, including peers and experienced scriptwriters, to make improvements.

How do you write a script for beginners?

1. start with an idea:.

Begin by brainstorming ideas for your script. Think about the story you want to tell, the themes you want to explore, and the characters you want to create. Your idea can come from personal experiences, books, news stories, or simply your imagination.

2. Study the Craft:

Familiarize yourself with the basics of scriptwriting. Read scripts of movies or TV shows in your chosen genre to get a sense of formatting, structure, and style. There are also many books, online courses, and resources available to learn more about scriptwriting.

3. Choose Your Format:

Determine the format for your script. The most common formats are screenplays for movies and TV, stage plays for theater, and teleplays for television. Each has specific formatting guidelines, so make sure to choose the appropriate one for your project.

4. Create an Outline:

Develop an outline that sketches out the main plot points, characters, and the overall structure of your script. Consider the three-act structure often used in storytelling, and identify key turning points in your plot.

5. Develop Your Characters:

Create well-rounded and relatable characters. Define their backgrounds, motivations, and character arcs. Understand their strengths, weaknesses, and how they evolve throughout the story.

6. Write the Script:

Start writing your script, following the industry-standard formatting for your chosen medium. Common script elements include scene headings, character names, dialogue, and action descriptions. Be concise and clear in your writing.

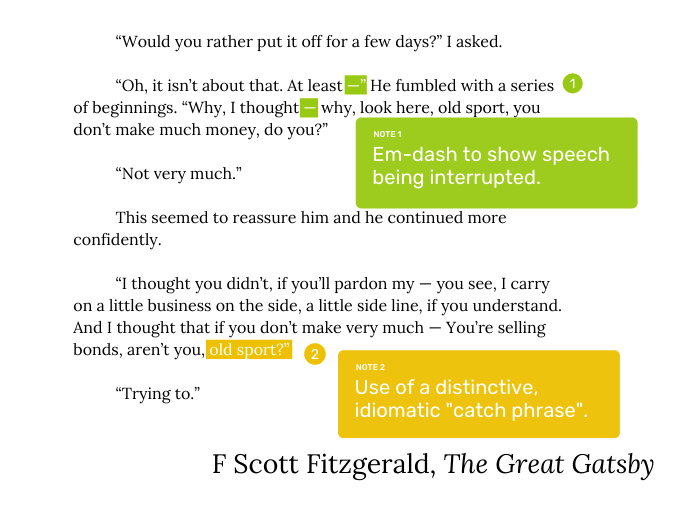

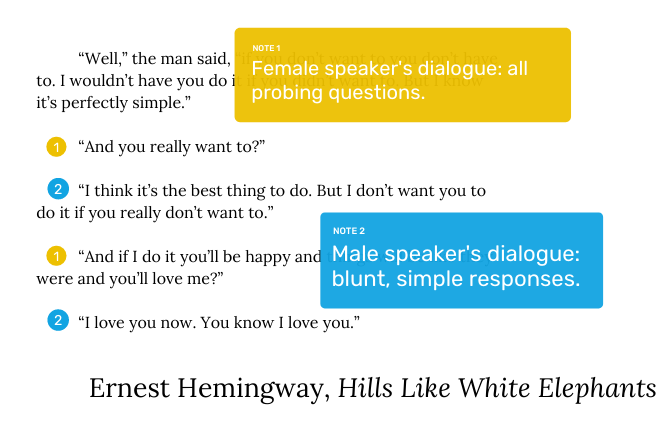

7. Focus on Dialogue:

Pay special attention to writing natural and engaging dialogue. It should reveal character traits, move the plot forward, and reflect the characters’ unique voices. Read the dialogue out loud to ensure it sounds realistic.

Types of Script Writing

- Screenwriting for Film : This involves writing scripts for movies. Screenplays include detailed descriptions of scenes, character dialogues, and directions for actors and cameras. The narrative can range from short films to feature-length movies.

- Television Writing : Scripts for TV shows can vary greatly depending on the format, including serialized dramas, sitcoms, reality shows, and news programs. Writers often work in teams to produce episodes for a series, following specific guidelines to maintain consistency.

- Playwriting for Theatre : Writing for the stage, playwriting involves crafting scripts for live performances. Plays require dialogue and stage directions to guide actors and directors, emphasizing strong character development and plot to engage the audience in a real-time setting.

- Radio Scriptwriting : Radio scripts are written for a broadcasts, focusing on dialogue, sound effects, and music to tell a story or convey information without visual elements. This form includes radio dramas, talk shows, and commercials.

- Video Game Writing : This involves creating the narrative for video games, including character dialogue, story arcs, and world-building elements. Video game writing is interactive, requiring multiple scenarios and outcomes based on player choices.

- Documentary Scriptwriting : Writing for documentaries involves crafting a narrative that combines factual information with storytelling. Scripts may include voice-over narration, interviews, and visual descriptions to guide the documentary’s flow and structure.

- Commercial and Advertising Scriptwriting : This type involves creating scripts for commercials and advertisements, focusing on persuasive language and compelling narratives to promote products or services within a very short timeframe.

- Web Series Writing : Scripts for web series are created specifically for online platforms, catering to a diverse and often niche audience. Web series can vary in genre and format, allowing for creative freedom and experimentation.

- Animation Writing : Writing for animation involves scripts for animated films or series, requiring imaginative storytelling that complements visual art and animation techniques. It includes character dialogues, actions, and sometimes musical sequences.

What is difference between script and screenplay?

| Aspect | Script | Screenplay |

|---|---|---|

| More general and can refer to any written document intended for performance, including scripts for theater, radio, and more. | Specifically refers to a written document for a film or television production. | |

| May be intended for actors, directors, or theater production teams, depending on the context. | Primarily intended for filmmakers, including directors, producers, actors, and crew members involved in film or TV production. | |

| Formatting and style may vary depending on the medium (theater, radio, etc.). | Follows industry-standard formatting guidelines specific to the film or TV industry. | |

| Generally used for a broader range of performances and may include more narrative description and stage directions. | Focuses more on visual and a elements relevant to film or television, such as camera directions and scene transitions. | |

| May contain more detailed descriptions of the characters and their actions to guide actors and directors. | Typically contains less character and action description, as this is often left to the director’s interpretation. | |

| Less common in the context of film and TV, as “screenplay” is the preferred term for these mediums. | The standard term used for writing for film and television. | |

| A stage play script, a radio script, or a script for a live theater performance. | A script for a feature film, a TV series episode, or a teleplay for a TV show. |

General FAQ’s

What makes a good script.

A good script is compelling, with well-defined characters, engaging dialogue, a strong structure, and a clear theme, offering a meaningful story that resonates with its audience.

How do you write a script with no dialogue?

To write a script with no dialogue, focus on visual storytelling. Develop a clear concept, outline, and rely on actions, expressions, and imagery to convey the narrative effectively.

How long does it take to write a script?

The time to write a script varies widely, depending on the type, complexity, and writer’s experience. A feature film script may take several months, while a short script might be completed in a few weeks. It’s influenced by factors like research, planning, revisions, and individual writing speed.

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

10 Examples of Public speaking

20 Examples of Gas lighting

How to Write a Script: From Idea to Screenplay

What is a script? How long does it need to be, and most importantly, how to write a basic screenplay are some commonly asked questions amongst new, up and coming script and screenwriters.

Well, when we really break it down, a script is simply written work (all in size-12 courier font) of roughly 90 -120 pages which translates your creative word smithing into how the visuals and audio on screen will unfold.

On the surface, trying to write a script or screenplay is deceptively simple, partially because everybody intrinsically understands the language of cinematic storytelling.

It is an inevitable (and crucial) byproduct of growing up watching movies – everybody knows the feeling of being able to anticipate a character’s next move, or character dialogue, or scene locations or when the plot will shift directions, or when the monster is about to crash through the window. If you know movies, you know enough to write the screenplay, right?

Another part of the deception is the textual nature of script themselves: the formatting on the page creates a lot of empty space. Anyone who’s spent time in a script editor knows the giddy sensation of typing along and finding themselves suddenly ten, or twenty, or even thirty pages into a script.

Start writing your script today with the Celtx Script Writing Editor – Sign up Here (It’s Free!)

The problem is that screenplays are as much technical documents as they are works of art. You could craft a beautifully heartfelt and original script that will be rendered completely unfilmable by virtue of the way that you wrote it.

You could have a one hundred and fifty page script that would only justify forty minutes of screen time. The margin for error in writing a script is enormous, because a screenplay isn’t a story to be read on its own: rather, it is a blueprint for creating something larger and much more complex.

Consider the Frankenstein metaphor: stitching the creature together is one thing, bringing it to life is something else entirely.

So how do you stitch together a good creature? Wait, I mean, so how does one write a good screenplay? For those new to the craft, here are some simple, helpful directives to get you on the right track.

How to Write a Script – A Basic 5-Step Guide

- Create a Logline & Develop Your Characters

- Write an Outline

- Write a Treatment

- Write Your Script

- Write Your Script Again

Step 1 – Create a Logline & Develop Your Characters

A great way to start the process of writing a script is by coming up with a logline: one or two sentences that will encapsulate your story in an intriguing manner. Once you’re done with that, develop your characters. Write their backstories. Refine their personalities.

Think about what makes them tick. Always make sure that your characters have goals that they need to achieve, and ensure that those goals carry high stakes should your characters fail to meet them. This does not mean that their goals need to be lofty, they just need to be authentic. The stakes can be as high as the end of the world or as personal as the end of a friendship.

The point is that characters having purpose is what makes them interesting. Flat characters destroy scripts. No matter how great your action sequences are or how original your concept is, one dimensional and uninteresting characters will drag your story to a halt.

You’ll find that writing with your characters’ personalities and goals in mind will take your story in unexpected places, and usually for the better.

Step 2 – Write an Outline

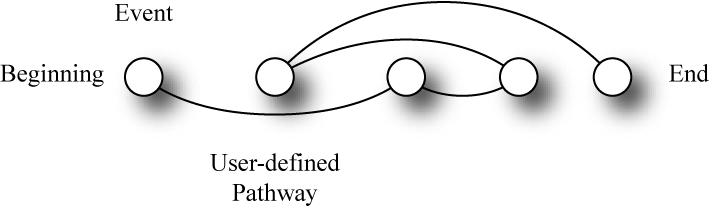

An outline (sometimes called a ‘beat sheet’) is a brief synopsis of your entire story. Try to fit it on one to two pages, and be concise. Broad strokes are key here. Think of the outline as the ‘definition’ of your script that breaks down the movement of the story, plot point by plot point. This is where you should begin to think about structure.

Essentially, conventional cinematic storytelling is bound to a classical format of three acts: It’s just how people expect stories to be told. There are many books written on the subject of screenplay structure, but the fundamentals are pretty simple. An average screenplay will be about ninety to one hundred pages.

Divide those pages by three. There’s your acts:

The 1st one should introduce your characters and setting and feature an inciting incident that gets the story underway.

The 2nd act is where your characters encounter obstacles as the story escalates into a crisis.

The 3rd act is where the crisis becomes climax (think victory or defeat), after which the story slows down and resolves itself. Don’t think of it as a paint by numbers approach – there’s plenty of room for experimentation and subversion.

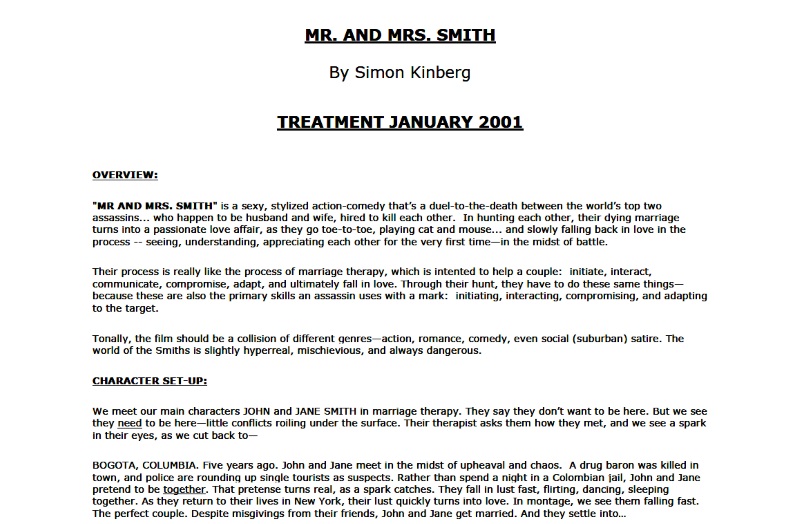

Step 3 – Write a Treatment

Now you get to start flexing your prose muscles and develop your style.

Treatments are effectively a more in-depth version of your outline. Expound upon it and write your whole story scene by scene in a conventional manuscript style. Experiment with dialog, or at least make note of what you want your characters to say. Develop your settings and have fun with descriptions.

The treatment is where you really start building the world that your story takes place in. The length of a treatment is dependant on both the kind of story you’re telling and the length of the intended finished product.

For reference, a typical feature treatment will clock in at around thirty pages.

Step 4 – Write Your Script

Time to get to work.

Go to it, and godspeed. It’s always a good idea to write in a script editor like Celtx to help streamline the process . Celtx Studio features one that is tried, true, and hugely popular – and it’s free.

You’ve developed your characters, structured your plot, and have an inspired treatment. Understand the formatting. Write in the present tense. Brevity is your friend. Remember to show, not tell: you’re writing for the eyes and the ears.

Bonus Screenwritng Tip #1: If you’re feeling a little uninspired on the creative direction of your script, then a great trick is to take notes on the go of the interesting conversations, news articles, and people you encounter. This can be as simple as taking notes on your phone or a notepad.

Step 5 – Write Your Script Again (and again, and again)

Completing the first draft is an accomplishment to be celebrated, but it’s just the beginning. If you think your first draft is perfect, it’s not (sorry).

Go back, read it through, take stuff out, and add stuff in.

Get other people to read it and commit yourself to being open to constructive criticism. Don’t just look for feedback from professionals and editors – lovers of science fiction film, or plain old movie fans can offer advice just as sound as any seasoned screenwriter.

Throw your script out there and surround yourself with the ideas that come back. Always be refining and revising, and just when you think you can’t possibly revise any further, do it again.

It all comes down to practice. Most professional screenwriters complete multiple features before they write a script that sells. A select few hit it out of the park on the first draft. All will agree that you need to be dedicated, and that most of all, you need to love your story. If you don’t, it’ll never be complete.

Script writing software for storytellers – Celtx. Try it Today for Free

7 Screenwriting Tips and Tricks for Beginners

Now that you have your framework lined up, it’s time to dive deeper into what it takes to write the final draft of a script. Below are 7 script writing tips that will help you when writing your first draft.

How to Write a Script – Top 7 Tips

- Do Some Homework and Play to Your Strengths

- Read Scripts

- Watch Your Favorite Films

- Learn How to Write a Script From a Single Sentence

- Learn How To Develop a Beat Sheet and Treatment

- Familiarize Yourself With Scriptwriting Language

- Consider Using a Quality Scriptwriting Software

1. Do Some Homework and Play to Your Strengths

Write to your strengths. Like any new craft, scriptwriting will come with some fresh creative lessons.

Through the process of your first draft, you will learn how to build a script from an infant idea to a finished product, all while becoming familiar with the formatting and terminology along the way. Therefore, for your first draft, writing to your strengths is a great place to start.

What are you already good at? What do you already have a natural strength or interest in? Is there an area of work or the world that you know well? These questions are not designed to find any expert-level knowledge, they’re designed to probe what your strengths are .

You may be the comic of your group of friends, so try starting with a comedy. Perhaps you are the family historian, so a historic film or one with investigative themes may come more easily to your skillset.

Another way to approach writing to your strengths is to set the film in a place you are very familiar with, such as your hometown or country. Also, if you are not sure of your strengths, why not ask the people around you for some help?

Through conversations with others, you may realize areas of your life that you are passionate to discuss, whether it’s about your childhood, sport, social injustices, work, or family life.

2. Read Scripts

Many of our most beloved films have their original scripts available online and are easily accessible for us to read and analyze. Try to find even two or three film scripts online for stories you are already familiar with and give them a read.

This is an enjoyable exercise, and chances are you will be amazed to read how such memorable scenes and movies were once first sketched out in words. You may even be surprised to see how stripped back the visual notes and script cues are that created these entire visual worlds on screen.

Your script should emulate this neat, efficient writing style when you are translating ideas for visuals into words.

Bonus Script Writing Tip #2: Writing a script can take as long as you want it to but, assuming this is a part-time project to be done while balancing other commitments, allocating 12 weeks of work should be enough time to complete a solid first draft.

3. Watch Your Favorite Films

Okay, so let’s say you want to write a movie script , then start by reflecting on why you love some movies and why you hate others. This is one of the best (and most fun) ways to learn how to write a movie script.

Take note of details you appreciated and try injecting similar elements into your own work. We can all easily sit back and enjoy our favorite films, but consciously analyzing the films we enjoy and taking notes of what elements work is helpful for getting our own scriptwriting and creative hats on.

If you’re not sure how to start picking apart your favorite films, take down notes for each of these categories: sound, dialogue, setting, character, editing, and lighting. These are some of the key script elements which create the mood and atmosphere on screen, so picking apart what you found effective will certainly inform your own script.

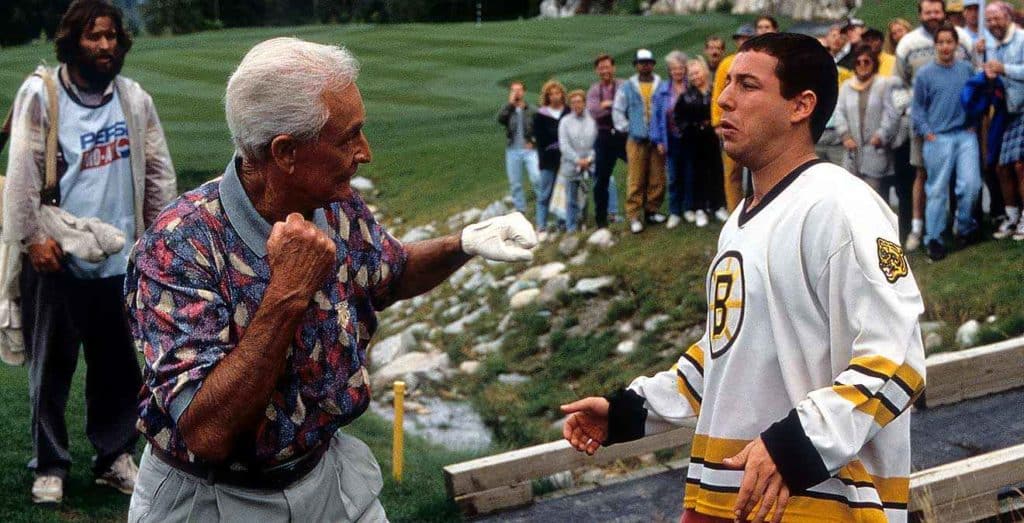

Also, while it is helpful to watch your favorite film (Happy Gilmore for me) to see how well all these things are executed, it can be just as helpful to watch, well . . . bad films too. Seriously! This may sound like an unusual piece of advice, but when you watch a bad movie, it can also quickly show you what elements are not working well.

Unlike great movies where all the elements flow and work together seamlessly, bad movies make their separate elements easy to spot and analyze. For example, The Room (2003) is a cult-hit “bad movie” which will help you see how key film elements, such as editing and dialogue, are disjointed.

If watching a great movie is eating an amazing meal at a restaurant, then watching a bad movie is more like stepping behind the scenes and into the chaotic kitchen.

Also, if you already have an idea for a film, do a little research into this genre. You may find more creative inspiration and wisdom in what the existing genre is doing and, perhaps, how your film could be a fresh take on an angle currently missing in the genre.

For example, if you want to write a horror film set inside a farmhouse, try watching some horror films and keep an extra eye out for horror films which are set predominantly inside.

While doing some research into films which thematically are similar to what you want to achieve will help you come away with a list of things you were inspired to do (and what not to do!), the possible sources of inspiration for your script are really endless. For another example, you could base your story from your own life, a book you read, a play you saw or a wild dream you just had.

Remember folks, at this stage, before getting into writing your script, you have complete creative license and agency, the creative origin point of this entire project. Of course, later down the line, scripts will be revised, partly rewritten, and tweaked to accommodate the needs of directors, producers, and the studio’s needs. But, right now, you’re in the creative driver’s seat!

4. Learn How to Write a Script From a Single Sentence

You have an awesome idea, and you know what you want to do with your characters, but are you still wondering how your script will actually get written? This is a great place to be. Before cannonballing into the deep end, take these steps to thoughtfully build up your script like a screenwriting pro.

The first essential step is to write your script’s logline , also sometimes known as a “slugline.” This logline should be no longer than two sentences or about 50 words in length. Your logline should capture your script’s main obstacles or action into a single-sentence nutshell.

Of course your entire script cannot be boiled down into one line, but loglines are not designed to be comprehensive and fit your entire story in; they should describe the thrust of action facing your characters and hook the reader’s attention into reading the rest of your script.

The logline tends to focus on the central character’s mission and contextualizes them in the place they are starting. The logline for documentary Won’t You Be My Neighbour (2019) , about the life of TV personality Mister Fred Rodgers reads, “A portrait of a man whom we all think we know, this emotional and moving film takes us beyond the zip-up cardigans and the land of make-believe, and into the heart of a creative genius who inspired generations of children with compassion and limitless imagination.”

You will notice an effective logline gives us a flavor of the story, a hint at the narrative but continues to leave readers seeking more information and depth. Your logline will be an excellent summary to keep on hand while writing your final script because it anchors your narrative and reminds you of your initial storytelling goals. Think of it as your storytelling mission statement.

5. Learn How To Develop a Beat Sheet and Treatment

The next key step in learning how to write a script is to make a beat sheet and treatment for your script. You can make your beat sheet and treatment documents in either order, depending on your own preference.

Your beat sheet is essentially a bullet-pointed skeletal version of your script. From beginning, middle to end, all the key moments are jotted down in chronological order. Each “beat” is a sentence or two long and simply states the action taking place.

Related Article by Celtx: How to End a Screenplay [3 Effective Script Endings]

For example, “Hannah arrives at work and realizes her car is missing”. Again, it is useful in this stage to avoid overly floral and descriptive language so that the action is really laid bare. It’s very common during this stage to identify gaps in your narrative, which is exactly why this exercise is so important.

Suddenly you may find yourself with some creative gap-filling and work to do, and that’s great. This is the ideal time for you to spot untethered parts of your story and fix them into place. There are two common and constructive methods for crafting a beat sheet: using a Word document to bullet point these action beats or using index cards with a sentence on each and ordering and reordering them as needed.

If running through your script in chronological order is proving too difficult for now, try starting at the end or the middle and working backwards. Most scripts are structured in a tripartite way, meaning you will have one third dedicated to the beginning, a middle third with a focus on the action, and the last third for the dramatic final act.

This storytelling structure follows a “set-up, confrontation, and resolution” approach. Splitting-up your bullet points over three pages, with approximately 30 points on each, will be roughly enough beats for a 90-minute movie. Whether you have a bullet pointed list or ordered index cards on a board, your finalized beat sheet should make it clear how your script’s action unfolds from beginning to end.

Bonus Script Writing Tip #3: A useful measure of your script’s length is the same way most writers and producers calculate your script length – one page of your script equating to one minute of the film on screen. Simple, right?

Next, with your logline and beat sheet completed, it is time to write your script’s treatment. This is a 3 to 5 page document which uses descriptive language and brings your lean beat sheet into a short story format which more vividly brings your story and characters to life.

This is the perfect opportunity to highlight your character profiles in detail by describing their characteristics and motivations. A script treatment is often used as a kind of marketing tool which would accompany your script when being sent to potential buyers or producers, therefore it is important to have a strong treatment which actively portrays the themes, visuals, and overall tone of your script.

Writing your treatment is like writing a descriptive and polished blurb for your film.

Now, it is time to open your scriptwriting software , jump to the first page, set yourself a realistic deadline for completing this script and get writing. Start by writing your script’s title page – this includes the film’s title, your name and contact email on the title page, and then get into the script!

Get Started with Your Script Today (FREE to Sign-Up)

6. Familiarize Yourself With Scriptwriting Language

It’s essential to familiarize yourself with scriptwriting language before writing your script.

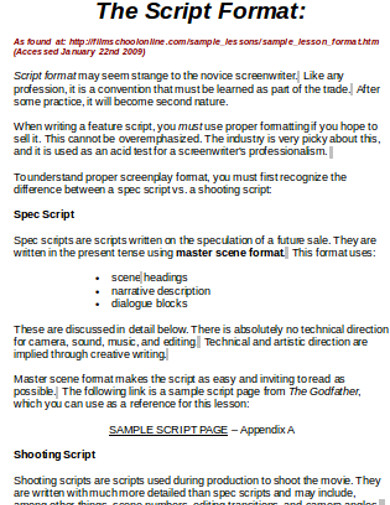

Most scripts are considered to be a “spec script”, as a short way of saying “speculative script.” Later in the creative process your script would need to be iterated by directors and producers into a “shooting script” to get the script camera ready.

A shooting script contains more detail for editing purposes and camera angles for the purposes of filming, which directors will infuse based on their own visions. Remember, while you are writing your ‘spec script’, you do not need to include details on camera angles or how scenes will transition at this stage. Stick to the story.

Don’t worry, you won’t have to learn a whole new scriptwriting language to write. However, there are a handful of terms which you should learn because you’ll employ them constantly while writing. By writing your screenplay with a baseline familiarity or, better yet, a firm grasp of these terms, then your work will just continue to flow more easily.

These terms are the fundamental building blocks of scriptwriting language and will come up in every script you read or write!

Scene heading : This heading signifies the beginning of every scene and is placed at the very top of each in ALL CAPS. It will either say: “EXT.” or “INT.” These abbreviations are simply short for “exterior” and “interior” to describe the location of the action in your scene. This is followed by the name of the location itself, as well as the approximate time of day in which the scene takes place. For example, “INT. KITCHEN – NIGHT” or “EXT. GARDEN – DAY”

Action Descriptions : This is one of the easiest terms to pick up and start using. Action lines are describing the action of your characters in any scene. It may be tempting to write long descriptions, but keep these sentences as neat as you can. Remember: you’re not writing a novel or poetry; you’re describing the literal action as it appears on-screen.

Characters . When introducing characters for the first time within an action description, capitalize their name and include 10 or so words that describe their main attributes. When they speak, their character name is centered on the page with their dialogue immediately following.

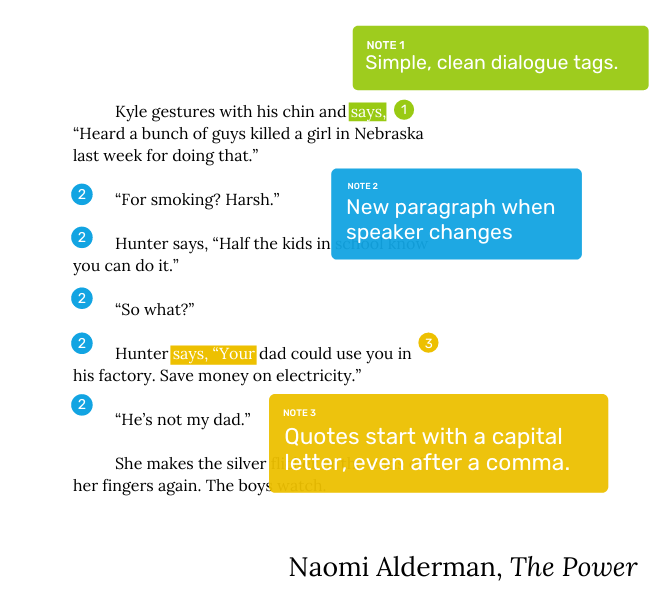

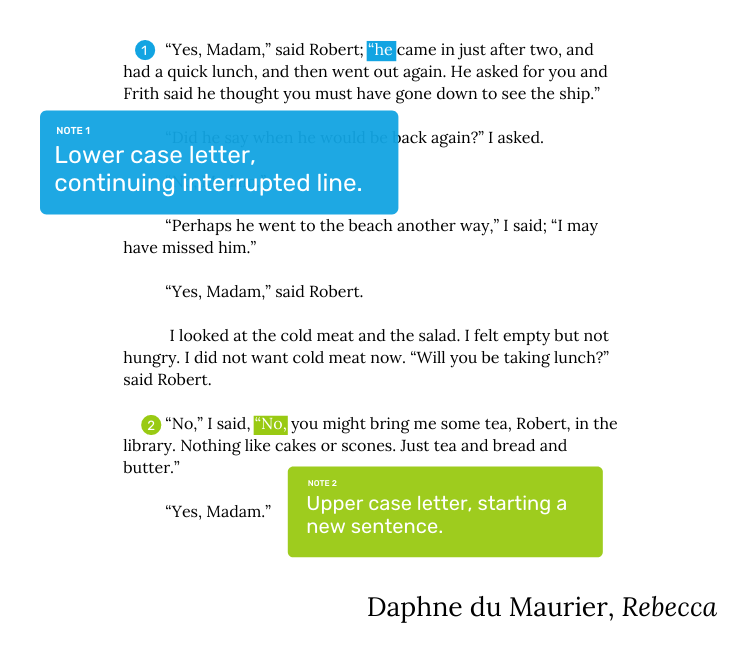

Dialogue . This goes in the center of the page beneath the name of the character speaking. To make your dialogue as authentic as possible, focus on understanding your characters as if they were real people. Subconsciously writers often project their own voices or world view; make sure to avoid this common trap!

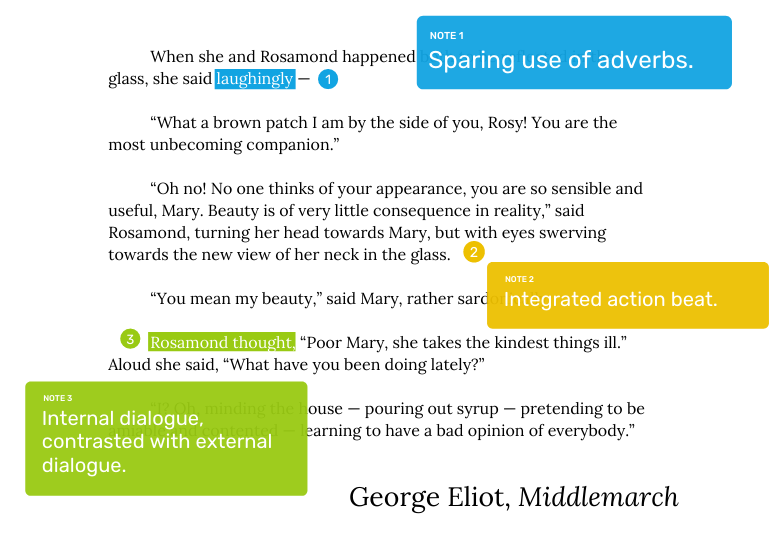

Parenthetical : A parenthetical is one of the ways scriptwriters can add performance or action details related to lines of dialogue. These provide helpful texture but make sure to use these sparingly. For example, (begrudgingly), (emphatically), or (excitedly) would go before a character’s line of dialogue, as could (scrunches nose), (scoffs), or (points)

With all these scriptwriting phrases and abbreviations under your belt, you’ll find it easier to write and make sense of the scriptwriting software you decide to use. Almost all scriptwriting software today intuitively formats your script out for you – meaning it will add details like parentheticals and formatting conventions like capitalized scene headings wherever appropriate, which makes your life easier and script better.

7. Consider Using a Quality Scriptwriting Software for Your First Spec Script

There are a bevy of professional, quality, and affordable scriptwriting softwares available online. Not only will investing in scriptwriting software make it easier to format your work, but it will also teach you a great deal about the correct, standardized script format used throughout the entire entertainment industry.

Scripts have a rigid and strictly adhered-to format, and the sooner you become fluent in this scriptwriting language, the better.

Having a reliable and intuitive screenwriting software used to assist you through the screenwriting process will make your life much easier, and instead of being bogged down with formatting, you can focus your energy and attention into the storytelling.

If you haven’t yet, you should try using a script writing software like Celtx. This will automatically format your script in Hollywood style format, which is often considered as “industry standard“.

Like any new challenge or project, there will be ebbs and flows of inspiration and willingness to see your screenplay through to the end.

It’s useful to anticipate difficult moments where you feel at a loss as to how to continue and finish this massive endeavor. That’s ok! And what every writer on the planet experiences regularly.

Don’t worry about finding a blockbuster-worthy moment straight away; often the best insights and creativity are found in day-to-day encounters. Keep an eye out, take note, and switch on your creative antenna in the process.

If you prepare for moments of “ writers’ block ”, then you’re better preparing yourself for successfully overcoming that hurdle.

Also, if you hit a writers’ block then you’re in good company as countless notable scriptwriters experience this too. Recently Taika Waititi reassured an audience that opening your laptop, staring at a blank document, feeling sad, and then closing your laptop is “still classified as writing”.

Writing an amazing script will require constant dedication – be patient with yourself and stick at it!

Andrew Stamm is based in London with his wife and dog. He spends his working time as Partner and Creative Director at Estes Media, a budding digital marketing agency, and performs freelance scriptwriting services on the side. Off the clock he loves to bake, hike, and watch as many niche films as possible.

You may also like

Overcoming writer’s block: strategies for unstuck creativity, what is a slugline definition & examples, character arc essentials: transforming characters from good to..., how to format dialogue in screenplays: rules you..., how to write a tv show (a true..., spec scripts uncovered: what they are and why....

- Screenwriting \e607

- Directing \e606

- Cinematography & Cameras \e605

- Editing & Post-Production \e602

- Documentary \e603

- Movies & TV \e60a

- Producing \e608

- Distribution & Marketing \e604

- Festivals & Events \e611

- Fundraising & Crowdfunding \e60f

- Sound & Music \e601

- Games & Transmedia \e60e

- Grants, Contests, & Awards \e60d

- Film School \e610

- Marketplace & Deals \e60b

- Off Topic \e609

- This Site \e600

Screenwriting Basics: A Beginner's Guide

If you're starting out, here's the basics to help you succeed..

'The Worst Person in the World'

Welcome to the captivating world of screenwriting! This post is deWhether you're a budding filmmaker or an enthusiast dreaming of seeing your stories come alive on the big screen, understanding the basics of screenwriting is crucial. This guide is designed to walk you through the fundamentals, offering both insight and practical tips to kickstart your screenwriting journey.

Understanding the Essence of a Screenplay

A screenplay is more than just a story. It's a blueprint for a film. It combines narrative, dialogue, and visual instructions to guide directors, actors, and the entire film crew.

Unlike a novel, a screenplay focuses on showing, not telling, and is written in a present-tense, concise style.

The Structure: Building Your Story's Skeleton

One of the first lessons in screenwriting is mastering the three-act structure:

- Act One – The Setup: This act introduces the main characters, setting, and the story's primary conflict. It often culminates in a 'turning point' that propels the story into the second act.

- Act Two –The Confrontation: The longest section of your script, this act deepens the conflict and develops your characters. It's filled with obstacles and often ends with a climax or a major setback for the protagonist.

- Act Three– The Resolution: This final act resolves the story's conflicts and questions, leading to a satisfying conclusion. Whether it's a happy ending or a tragic one, it should feel earned and true to the story.

Character Development: The Heart of Your Screenplay

Great films are driven by compelling characters. Your characters should have distinct personalities, desires, and flaws. A well-developed character arc , where a character evolves in response to the story's events, adds depth to your screenplay.

Dialogue: Giving Voice to Your Characters

Dialogue in screenplays serves multiple purposes. It reveals character, advances the plot, and delivers exposition. Strive for natural, engaging dialogue that reflects each character's unique voice.

Remember, less is often more. Avoid unnecessary exposition.

Show, Don't Tell

Screenwriting is visual storytelling. Instead of describing what's happening, illustrate it through actions and dialogue.

For instance, instead of writing "John is sad," show John looking at an old photo and wiping away a tear. This "show, don't tell" principle is key to engaging the audience.

The Importance of Format

Professional screenwriting demands adherence to a specific format. This includes using a 12-point Courier font, correct margins, and proper scene headings.

Software like Final Draft raft or Ce ltx can help you maintain the standard format.

Writing Your First Draft

Begin with an outline or a treatment, which is a narrative description of your story. Then, start writing your first draft.

Don't worry about perfection. The first draft is about getting your story down. Editing and polishing come later.

The Art of Rewriting

Screenwriting is as much about rewriting as it is about writing. Once your first draft is complete, take a break, then come back with fresh eyes. Look for plot holes, character inconsistencies, and opportunities to sharpen your dialogue. Feedback from trusted peers can be invaluable during this process.

Breaking Into the Industry

As a beginner, your focus should be on honing your craft. However, it's never too early to learn about the industry. Participating in screenwriting contests, workshops, and networking events can provide exposure and learning opportunities. Online platforms like The Black List or Inktip can be avenues to showcase your work.

Continuous Learning and Adaptation

'The Devil Wears Prada'

Credit: 20th Century Fox

The world of screenwriting is dynamic. Keep learning by reading screenplays, watching films, and staying updated with industry trends. Adaptability and a willingness to learn are key.

Embarking on a screenwriting journey is both exciting and challenging. Remember, every great filmmaker and writer started somewhere. Your unique voice and stories are what the film industry needs. Embrace the process, keep writing, and who knows–your screenplay might just be the next big hit on the big screen!

This beginner's guide is just the starting point. Screenwriting is a craft that takes time and practice to master. Stay curious, stay dedicated, and most importantly, keep writing.

Your journey in the world of screenwriting starts now!

Now go get writing.

- Learn Script Formatting (& Why Screenplay Format Matters) ›

- Writing 101: A Simple Breakdown of How to Structure Your Screenplay ›

- Need to Improve Your Screenwriting? Check Out Screenwriting Fundamentals Course (for Free) ›

- How to Write a Screenplay / The Basics — nycmidnight ›

- How to Write a Screenplay: Script Writing Example & Screenwriting ... ›

- Screenwriting Basics — Slugline ›

A Week in the Life of Emmy-Nominated 'Frasier' DP Gary Baum

Hear a first-hand breakdown of prepping a live multi-cam network shoot from seasoned vet gary baum..

Written by Gary Baum

Since I Love Lucy debuted on CBS in 1951, the Multi-Camera format has defined the comedy genre on television. Desi Arnaz and Lucille Ball created the format along with Karl Freund, ASC.

Their original intention was to film the comedy series with 3 cameras shooting simultaneously in front of an audience. The successful format has endured for almost 75 years, with of course updated modern technology .

Now we shoot with digital 4k format in 1:78 to achieve a 16x9 view, which is compatible for network and streaming delivery. With most studio audience shoots, such as Frasier , we use four Sony VENICE cameras with Panavision primo zoom lenses, maintained by my DIT. I shoot in S-log utilizing an on set LUT created by my Video Control operator.

Since the comedy is shot proscenium style to incorporate the full effect of watching the entire scene without breaks, it affords the audience the experience of a theatrical performance and the actors with a live feedback that isn't available on other formats.

Four cameras are blocked to capture all required angles; wide, medium, overs, two shots, singles etc.

The cameras are constantly moving to predetermined queues which require different focal lengths and angles. A typical four minute scene can incorporate 40 to 50 shots. It’s a ballet of sorts, and quite the visual experience onto itself.

Lighting for the multi-camera experience is a world onto it’s own. We must light from above without any lights on the stage floor to impede the camera’s movement. Every scene is lighted for four cameras, as we don’t have the luxury of lighting for multiple setups within a scene as with a feature or single camera TV.

For a typical five day work week, the first production day starts with a production meeting followed by a table read, and usually a light rehearsal. Hopefully the sets are up and we can start our lighting. We start the “heavy lifting” of using our larger units placing them for cross back keys and to entrance points. We use fresnel incandescent units for their throw ability as these lights can be 20 plus feet away from the intended target. I carry custom engineered LED “Obie” lights on each camera.

The second day is another rehearsal with a producer run through. At this stage, we can see the actors’ movements which then we can address with our smaller lights and some fill ratios. The third day, is rehearsal again, dealing with some script re-writes and actors movements with a final studio run through. At this point we can hopefully finish our broad lighting palate.

The fourth day is the first of two camera days. All four cameras on dollies and or pedestals arrive for the director’s blocking with line queues facilitated by a camera coordinator.

On this day we try to finish our actors’ lighting and polish our architectural lighting ie; practicals, sconces, etc. Many of these days we'll pre shoot a scene or two because of guest actor availability, to release a set that is not in view of the audience, for single camera style coverage, or for children and animal performances.

All through the process we have to maintain as many as seven sets at once. We have monitors and a quad split with switching availability between each camera to view each shot simultaneously.

On the fifth day our audience day starts with a final rehearsal for actors and cameras dealing with re-writes and maybe some re-blocking before a break for touch ups and a crew meal.

Typically the audience files in to stadium style seating while being entertained by a warmup person with a DJ.

It is a theatrical experience for everyone. Show starts at 6 PM with cast intros.

At this point our lighting is done. Occasionally there are things to attend to, such as a re-block or a lamp burn out, but generally things go smoothly, and we all experience a fun evening. Typically a show will be three to four hours in length.

The next day, the process starts anew on our next episode.

After editing, the episode is cut down to 22 to 35 minutes and then I will go to post color and work with my colorist for final delivery.

Since I like to laugh, this is a fantastic medium to work in!

Blackmagic Camera App Set to Finally Come to Android

Turn your smartphone into an ai-powered micro-four-thirds camera, what are the best experimental films of all time, a list of screenwriting rules and how to break them, the ending of 'challengers' explained, expand your evf mounting options for the sony burano, 'dìdi (弟弟)’ filmmakers on the challenges of quick turnarounds with younger talent, reviewing eddy — your secret ai-powered assistant video editor, what is the extreme close-up shot, how to edit tiktok videos.

How to Write a Script (Step-by-Step Guide)

So you want to write a film script (or, as some people call it, a screenplay – they're two words that mean basically the same thing). We're here to help with this simple step-by-step script writing guide.

Or better yet, use our AI script writing generator -- it's designed to take your idea and flesh out a film script with voiceovers and camera directions for your storyboard. Bring your vision to life.

Lay the groundwork

1. know what a script is.

If this is your first time creating movie magic, you might be wondering what a script actually is. Well, it can be an original story, straight from your brain. Or it can be based on a true story, or something that someone else wrote – like a novel, theatre production, or newspaper article.

A movie script details all the parts – audio, visual, behaviour, dialogue – that you need to tell a visual story, in a movie or on TV. It's usually a team effort, going through oodles of revisions and rewrites, not to mention being nipped ‘n' tucked by directors, actors , and those in production jobs. But it'll generally start with the hard work and brainpower of one person – in this case, you.

Because films and TV shows are audiovisual mediums, budding scriptwriters need to include all the audio (heard) and visual (seen) parts of a story. Your job is to translate pictures and sounds into words. Importantly, you need to show the audience what's happening, not tell them. If you nail that, you'll be well on your way to taking your feature film to Hollywood.

2. Read some scripts

The first step to stellar screenwriting is to read some great scripts – as many as you can stomach. It’s an especially good idea to read some in the genre that your script is going to be in, so you can get the lay of the land. If you’re writing a comedy, try searching for ‘50 best comedy scripts’ and starting from there. Lots of scripts are available for free online.

3. Read some scriptwriting books

It's also helpful to read books that go into the craft of writing a script. There are tonnes out there, but we've listed a few corkers below to get you started.

4. Watch some great films

A quick way to get in the scriptwriting zone is to rewatch your favourite films and figure out why you like them so much. Make notes about why you love certain scenes and bits of dialogue. Examine why you're drawn to certain characters. If you're stuck for ideas of films to watch, check out some ‘best movies of all time' lists and work through those instead.

Flesh out the story

5. write a logline (a.k.a. brief summary).

You're likely to be pretty jazzed about writing your script after watching all those cinematic classics. But before you dive into writing the script, we've got a little more work to do.

First up, you need to write a ‘ logline '. It's got nothing to do with trees. Instead, it's a tiny summary of your story – usually one sentence – that describes your protagonist (hero) and their goal, as well as your antagonist (villain) and their conflict. Your logline should set out the basic idea of your story and its general theme. It's a chance to tell people what the story's about, what style it's in, and the feeling it creates for the viewer.

6. Write a treatment (a.k.a. longer summary)

Once your logline's in the bag, it's time to write your treatment . It's a slightly beefier summary that includes your script's title, the logline, a list of your main characters, and a mini synopsis. A treatment is a useful thing to show to producers – they might read it to decide whether they want to invest time in reading your entire script. Most importantly, your treatment needs to include your name and contact details.

Your synopsis should give a good picture of your story, including the important ‘beats' (events) and plot twists. It should also introduce your characters and the general vibe of the story. Anyone who reads it (hopefully a hotshot producer ) should learn enough that they start to feel a connection with your characters, and want to see what happens to them.

This stage of the writing process is a chance to look at your entire story and get a feel for how it reads when it's written down. You'll probably see some parts that work, and some parts that need a little tweaking before you start writing the finer details of each scene.

7. Develop your characters

What's the central question of your story? What's it all about? Character development means taking your characters on a transformational journey so that they can answer this question. You might find it helpful to complete a character profile worksheet when you're starting to flesh out your characters (you can find these for free online). Whoever your characters are, the most important thing is that your audience wants to get to know them, and can empathise with them. Even the villain!

8. Write your plot

By this point, you should have a pretty clear idea of what your story's about. The next step is breaking the story down into all the small pieces and inciting incidents that make up the plot – which some people call a 'beat sheet'. There are lots of different ways to do this. Some people use flashcards. Some use a notebook. Others might use a digital tool, like Trello , Google Docs , Notion , etc.

It doesn't really matter which tool you use. The most important thing is to divide the plot into scenes, then bulk out each scene with extra details – things like story beats (events that happen) and information about specific characters or plot points.

While it's tempting to dive right into writing the script, it's a good idea to spend a good portion of time sketching out the plot first. The more detail you can add here, the less time you'll waste later. While you're writing, remember that story is driven by tension – building it, then releasing it. This tension means your hero has to change in order to triumph against conflict.

Write the Script

9. know the basics.

Before you start cooking up the first draft of your script, it's good to know how to do the basics. Put simply, your script should be a printed document that's:

Font fans might balk at using Courier over their beloved Futura or Comic Sans. However, it's a non-negotiable when you write a script. The film industry's love of Courier isn't purely stylistic – it's functional, too. One script page in 12-point Courier is roughly one minute of screen time.

That's why the page count for an average screenplay should be between 90 and 120 pages, although it's worth noting that this differs a bit by genre. Comedies are usually shorter (90 pages / 1.5 hours), while dramas can be a little longer (120 pages / 2 hours). A short film will be shorter still. Obviously.

10. Write the first page

Using script formatting programmes means you no longer need to know the industry standard when it comes to margins and indents. That said, it’s good to know how to set up your script in the right way.

11. Format your script

Here’s a big ol’ list of items that you’ll need in your script, and how to indent them properly. Your script-writing software will handle this for you, but learning’s fun, right?

Scene heading

The scene heading is where you include a one-line description of the location and time of day of a scene. This is also called a ‘slugline’. It should always be in caps.

Example: ‘EXT. BAKERY - NIGHT’ tells you that the action happens outside the bakery during the nighttime.

When you don’t need a new scene heading, but you need to make a distinction in the action, you can throw in a subheader. Go easy on them, though – Hollywood buffs frown on a script that’s packed with subheaders. One reason you might use them is to make a number of quick cuts between two locations. Here, you would write ‘INTERCUT’ and the scene locations.

This is the narrative description of what’s happening in the scene, and it’s always written in the present tense. You can also call this direction, visual exposition, blackstuff, description, or scene direction. Remember to only include things that your audience can see or hear.

When you introduce a character, you should capitalise their name in the action. For example: ‘The car speeds up and out steps GEORGIA, a muscular woman in her mid-fifties with nerves of steel.’

You should always write each character’s name in caps, and put it about their dialogue. You can include minor characters without names, like ‘BUTCHER’ or ‘LAWYER.’

Your dialogue is the lines that each character speaks. Use dialogue formatting whenever your audience can hear a character speaking, including off-screen speech or voiceovers.

Parenthetical

A long word with a simple meaning, a parenthetical is where you give a character direction that relates to their attitude or action – how they do something, or what they do. However, parentheticals have their roots in old school playwriting, and you should only use them when you absolutely need to.

Why? Because if you need a parenthetical to explain what’s going on, your script might just need a rewrite. Also, it’s the director’s job to tell an actor how to give a line – and they might not appreciate your abundance of parentheticals.

This is a shortened technical note that you put after a character’s name to show how their voice will be heard onscreen. For example: if your character is speaking as a voiceover, it would appear as ‘DAVID (V.O.)’.

Transitions are film editing instructions that usually only appear in a shooting script. Things like:

If you’re writing a spec script, you should steer clear of using a transition unless there’s no other way to describe what’s happening in the story. For example, you might use ‘DISSOLVE TO:’ to show that a large portion of time has passed.

A shot tells the reader that the focal point in a scene has changed. Again, it’s not something you should use very often as a spec screenwriter. It’s the director’s job! Some examples:

12. Spec scripts vs. shooting scripts

A ‘spec script' is another way of saying ‘speculative screenplay.' It's a script that you're writing in hopes of selling it to someone. The film world is a wildly competitive marketplace, which is why you need to stick to the scriptwriting rules that we talk about in this post. You don't want to annoy Spielberg and co.

Once someone buys your script, it's now a ‘shooting script' or a ‘production script.' This version of your script is written specifically to produce a film. Because of that, it'll include lots more technical instructions: editing notes, shots, cuts, and more. These instructions help the production assistants and director to work out which scenes to shoot in which order, making the best use of resources like the stage, cast, and location.

Don't include any elements from a shooting script in your spec script, like camera angles or editing transitions . It's tempting to do this – naturally, you have opinions about how the story should look – but it's a strict no-no. If you want to have your way with that stuff, then try the independent filmmaker route. If you want to sell your script, stick to the rules.

13. Choose your weapon

While writing a big-screen smash is hard work, it's a heck of a lot easier nowadays thanks to a smorgasbord of affordable screenwriting software . These programmes handle the script format (margins, spacing, etc.) so that you can get down to telling a great story. Here are a few programmes to check out:

There are also a tonne of outlining and development programmes. These make it easier to collect your thoughts and storytelling ideas together before you put pen to paper. Take a peek at these:

14. Make a plan

When you're approaching a chunky project, it's always good to set a deadline so you've got a clear goal to reach. You probably want to allow 8-12 weeks to write a script – this is the amount of time that the industry would usually give a writer to work on a script. Be sure to put the deadline somewhere you'll see it: on your calendar, or your phone, or tattooed on your hand.

For your first draft, concentrate on getting words on the page. Don't be too critical – just write whatever comes into your head, and follow your outline. If you can crank out 1-2 pages per day, you'll have your first draft within two or three months. Easy!

Some people find it helpful to write at the same time each day. Some people write first thing. Some people write late at night. Some people have no routine whatsoever. Find a routine (or lack thereof) that works for you, and stick to it. You got this.

15. Read it out loud

One surefire way to see if your dialogue sounds natural is to read it out loud. While you're writing dialogue, speak it through at the same time. If it doesn't flow, or it feels a little stilted, you'll need to make some tweaks. Highlight the phrases that need work then come back to them later when you're editing.

16. Take a break

When your draft's finished, you might think it's the greatest thing ever written – or you might think it's pure dross. The reality is probably somewhere in the middle. When you're deep inside a creative project, it's hard to see the forest for the trees.

That's why it's important to take a decent break between writing and editing. Look at something else for a few weeks. Read a book. Watch TV. Then, when you come back to edit your script, you'll be able to see it with fresh eyes.

17. Make notes

After you've taken a good break, read your whole script and take notes on the bits that don't make sense or sound a little weird. Are there sections where the story's confusing? Are the characters doing things that don't push the story along? Find those bits and make liberal use of a red pen. Like we mentioned before, this is a good time to read the script out loud – adding accents and performing lines in a way that's true to your vision for the story.

18. Share with a friend

As you work towards a final version of your script, you might want to share it with some people to get their feedback. The Commenting & Feedback feature in Boords allows users to directly comment on individual frames and include necessary reference links, simplifying the process of responding to client feedback.

Friends and family members are a good first port of call, or other writers if you know any. Ask them to give feedback on any parts you're concerned about, and see if there's anything that didn't make sense to them.

The Shortcut to Effective Storyboards.

Boords is an easy-to-use storyboarding tool to plan creative projects.

Wrap things up

19. write final draft.

After you've made notes and gathered feedback, it's time to climb back into the weeds and work towards your final draft. Keep making edits until you're happy. If you need to make changes to the story or characters, do those first as they might help fix larger problems in the script.

Create each new draft in a new document so you can transfer parts you like from old scripts into the new one. Drill into the details, but don't get so bogged down in small things that you can't finish a draft. And, before you start sharing it with the world, be sure to do a serious spelling and grammar check using a tool like Grammarly .

20. Presentation and binding

There are rules for everything when writing a script. Even how you bind the thing. Buckle up!

This is a list of stuff you’ll need to prepare your script before sending it out and taking over the world:

And this is how to bind your script:

Related links

More from the blog..., how to write a logline.

Before you start work on your Hollywood-busting screenplay, you'll need a logline. It's a one-sentence summary of your movie that entices someone to read the entire script.

How to Write a TV Commercial Script

Writing commercial scripts for TV ads is entirely different from screenwriting a screenplay. Learn the format and download a handy template.

How to Tell a Story

It takes a lot of work to tell a great story. Just ask all the struggling filmmakers and authors, hustling away at their craft in an attempt to get a break.

21 Principles of Script Writing: A Comprehensive Guide to the Art of Script Writing

Scriptwriting is an art that holds the power to bring stories to life on the big screen or the small screen. From captivating movies to engaging television shows, every compelling visual narrative starts with a well-crafted script.

Table of Contents

Introduction

In the fascinating world of script writing, creativity intertwines with storytelling, and words have the power to transport audiences into vivid, captivating worlds. Script writing is an art that requires a delicate balance of imagination , structure , and skill .

Understanding the Art of Script Writing

Script writing is more than just putting words on paper. It is the art of storytelling through the lens of the written word.

Just like a master painter meticulously selects colors and brush strokes, a skilled scriptwriter weaves together characters, plotlines, and dialogue to create a tapestry of emotions and experiences.

Understanding the core principles of script writing is essential to crafting scripts that captivate and resonate with audiences across different mediums.

The Importance of Storytelling

In the world of script writing, storytelling is the lifeblood that pumps vitality into each scene, dialogue, and character. It has the power to stir emotions , provoke thoughts , and l eave a lasting impact on viewers long after the credits roll.

A well-crafted story takes the audience on a journey, introducing them to relatable characters, unveiling conflicts and challenges, and ultimately resolving the narrative in a satisfying manner.

The principles of script writing emphasize the importance of crafting a coherent and engaging story that holds the audience’s attention from the opening scene to the closing credits.

Elements of a Good Script

A good script is like a finely orchestrated symphony, where various elements harmoniously blend to create a powerful and unforgettable experience for the audience. Mastering the key elements of script writing is crucial to achieving this harmony and resonance.

Character Development

Memorable characters are the heart and soul of any script. They breathe life into the narrative, allowing audiences to connect emotionally and invest in their journeys.

To create well-rounded characters, scriptwriters must understand their backgrounds, values, and how they respond to different situations. By doing so, characters come alive on the page and evoke genuine emotions from the audience.

Plot Structure

A well-structured plot is the backbone of a successful script. It guides the audience through the story’s twists and turns, building tension and anticipation along the way.

The setup introduces the characters, their world, and the central conflict. The confrontation presents challenges and obstacles that the characters must overcome, intensifying the stakes and emotional investment. Finally, the resolution offers a satisfying conclusion that resolves the conflict and provides closure for the audience.

A strong plot structure keeps the audience engaged, ensuring that every scene and sequence serves a purpose in advancing the story.

Effective dialogue should also serve multiple functions, including advancing the plot, conveying emotions, and revealing subtext. Subtext refers to the underlying meanings and intentions behind the words spoken, allowing for deeper layers of storytelling.

Setting and Atmosphere

The setting and atmosphere of a script create the world in which the story unfolds.

Additionally, the atmosphere plays a crucial role in setting the emotional ambiance of the script. It influences how the audience feels while experiencing the story, whether it’s through suspense, humor, melancholy, or excitement.

Theme and Message