Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- What is Secondary Research? | Definition, Types, & Examples

What is Secondary Research? | Definition, Types, & Examples

Published on 20 January 2023 by Tegan George .

Secondary research is a research method that uses data that was collected by someone else. In other words, whenever you conduct research using data that already exists, you are conducting secondary research. On the other hand, any type of research that you undertake yourself is called primary research .

Secondary research can be qualitative or quantitative in nature. It often uses data gathered from published peer-reviewed papers, meta-analyses, or government or private sector databases and datasets.

Table of contents

When to use secondary research, types of secondary research, examples of secondary research, advantages and disadvantages of secondary research, frequently asked questions.

Secondary research is a very common research method, used in lieu of collecting your own primary data. It is often used in research designs or as a way to start your research process if you plan to conduct primary research later on.

Since it is often inexpensive or free to access, secondary research is a low-stakes way to determine if further primary research is needed, as gaps in secondary research are a strong indication that primary research is necessary. For this reason, while secondary research can theoretically be exploratory or explanatory in nature, it is usually explanatory: aiming to explain the causes and consequences of a well-defined problem.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Secondary research can take many forms, but the most common types are:

Statistical analysis

Literature reviews, case studies, content analysis.

There is ample data available online from a variety of sources, often in the form of datasets. These datasets are often open-source or downloadable at a low cost, and are ideal for conducting statistical analyses such as hypothesis testing or regression analysis .

Credible sources for existing data include:

- The government

- Government agencies

- Non-governmental organizations

- Educational institutions

- Businesses or consultancies

- Libraries or archives

- Newspapers, academic journals, or magazines

A literature review is a survey of preexisting scholarly sources on your topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant themes, debates, and gaps in the research you analyse. You can later apply these to your own work, or use them as a jumping-off point to conduct primary research of your own.

Structured much like a regular academic paper (with a clear introduction, body, and conclusion), a literature review is a great way to evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject. It is usually qualitative in nature and can focus on a person, group, place, event, organisation, or phenomenon. A case study is a great way to utilise existing research to gain concrete, contextual, and in-depth knowledge about your real-world subject.

You can choose to focus on just one complex case, exploring a single subject in great detail, or examine multiple cases if you’d prefer to compare different aspects of your topic. Preexisting interviews , observational studies , or other sources of primary data make for great case studies.

Content analysis is a research method that studies patterns in recorded communication by utilizing existing texts. It can be either quantitative or qualitative in nature, depending on whether you choose to analyse countable or measurable patterns, or more interpretive ones. Content analysis is popular in communication studies, but it is also widely used in historical analysis, anthropology, and psychology to make more semantic qualitative inferences.

Secondary research is a broad research approach that can be pursued any way you’d like. Here are a few examples of different ways you can use secondary research to explore your research topic .

Secondary research is a very common research approach, but has distinct advantages and disadvantages.

Advantages of secondary research

Advantages include:

- Secondary data is very easy to source and readily available .

- It is also often free or accessible through your educational institution’s library or network, making it much cheaper to conduct than primary research .

- As you are relying on research that already exists, conducting secondary research is much less time consuming than primary research. Since your timeline is so much shorter, your research can be ready to publish sooner.

- Using data from others allows you to show reproducibility and replicability , bolstering prior research and situating your own work within your field.

Disadvantages of secondary research

Disadvantages include:

- Ease of access does not signify credibility . It’s important to be aware that secondary research is not always reliable , and can often be out of date. It’s critical to analyse any data you’re thinking of using prior to getting started, using a method like the CRAAP test .

- Secondary research often relies on primary research already conducted. If this original research is biased in any way, those research biases could creep into the secondary results.

Many researchers using the same secondary research to form similar conclusions can also take away from the uniqueness and reliability of your research. Many datasets become ‘kitchen-sink’ models, where too many variables are added in an attempt to draw increasingly niche conclusions from overused data . Data cleansing may be necessary to test the quality of the research.

A systematic review is secondary research because it uses existing research. You don’t collect new data yourself.

The research methods you use depend on the type of data you need to answer your research question .

- If you want to measure something or test a hypothesis , use quantitative methods . If you want to explore ideas, thoughts, and meanings, use qualitative methods .

- If you want to analyse a large amount of readily available data, use secondary data. If you want data specific to your purposes with control over how they are generated, collect primary data.

- If you want to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables , use experimental methods. If you want to understand the characteristics of a research subject, use descriptive methods.

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to test a hypothesis by systematically collecting and analysing data, while qualitative methods allow you to explore ideas and experiences in depth.

Sources for this article

We strongly encourage students to use sources in their work. You can cite our article (APA Style) or take a deep dive into the articles below.

George, T. (2023, January 20). What is Secondary Research? | Definition, Types, & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 22 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/secondary-research-explained/

Largan, C., & Morris, T. M. (2019). Qualitative Secondary Research: A Step-By-Step Guide (1st ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd.

Peloquin, D., DiMaio, M., Bierer, B., & Barnes, M. (2020). Disruptive and avoidable: GDPR challenges to secondary research uses of data. European Journal of Human Genetics , 28 (6), 697–705. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-020-0596-x

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, primary research | definition, types, & examples, what is a literature review | guide, template, & examples, case study | definition, examples & methods.

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Supplements

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 8, Issue 10

- Multiple modes of data sharing can facilitate secondary use of sensitive health data for research

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Tsaone Tamuhla 1 ,

- Eddie T Lulamba 1 ,

- Themba Mutemaringa 2 , 3 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5083-2735 Nicki Tiffin 1

- 1 South African National Bioinformatics Institute, University of the Western Cape , Bellville , South Africa

- 2 Provincial Health Data Centre, Health Intelligence Directorate , Western Cape Department of Health and Wellness , Cape Town , Western Cape , South Africa

- 3 Computational Biology Division, Department of Integrative Biomedical Sciences , University of Cape Town , Rondebosch , Western Cape , South Africa

- Correspondence to Professor Nicki Tiffin; ntiffin{at}sanbi.ac.za

Evidence-based healthcare relies on health data from diverse sources to inform decision-making across different domains, including disease prevention, aetiology, diagnostics, therapeutics and prognosis. Increasing volumes of highly granular data provide opportunities to leverage the evidence base, with growing recognition that health data are highly sensitive and onward research use may create privacy issues for individuals providing data. Concerns are heightened for data without explicit informed consent for secondary research use. Additionally, researchers—especially from under-resourced environments and the global South—may wish to participate in onward analysis of resources they collected or retain oversight of onward use to ensure ethical constraints are respected. Different data-sharing approaches may be adopted according to data sensitivity and secondary use restrictions, moving beyond the traditional Open Access model of unidirectional data transfer from generator to secondary user. We describe collaborative data sharing, facilitating research by combining datasets and undertaking meta-analysis involving collaborating partners; federated data analysis, where partners undertake synchronous, harmonised analyses on their independent datasets and then combine their results in a coauthored report, and trusted research environments where data are analysed in a controlled environment and only aggregate results are exported. We review how deidentification and anonymisation methods, including data perturbation, can reduce risks specifically associated with health data secondary use. In addition, we present an innovative modularised approach for building data sharing agreements incorporating a more nuanced approach to data sharing to protect privacy, and provide a framework for building the agreements for each of these data-sharing scenarios.

- Public Health

- Health policies and all other topics

Data availability statement

Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study.

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2023-013092

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Summary box

Data sharing can ensure maximal ethical use of data resources to inform evidence-based health care.

Different models of data sharing that move beyond direct open access sharing can be used to address challenges arising from ethical and equity constraints on data re-use.

Data anonymisation and perturbation can increase protection of privacy and data security for sensitive data.

A framework using modularised data sharing elements can facilitate creating fit-for-purpose data sharing agreements.

Introduction

Data about health is the fundamental base on which evidence-based healthcare is constructed and underpins progress and innovation in health sciences and healthcare towards improved patient outcomes. 1–3 Traditionally, however, competitive research practices have discouraged data sharing, 4 and researchers may withhold research datasets they have generated in order to protect their career interests and retain the capacity to publish innovative and high impact research. In addition, concerns about intellectual property (IP) and commercial applications have also created barriers to secondary use of health data beyond the primary purpose for which they were collected. 5

There has been a growing recognition of the need to use and re-use health data for as many diverse and future analyses as possible, within the scope of permissions for use provided by research participants through their informed consent. This need reflects an ethical imperative to maximise the benefits for evidence-based healthcare from the use of health data as an offset against the risks or discomfits faced by participants contributing those data, 6 7 and has led to increasing pressure on researchers to make data and research outputs Open 8 9 meaning that access to scientific resources should be unrestricted and free of charge wherever this is possible. The prioritisation of Open Access has resulted in requirements to adhere to Open data access principles in order to receive research funding and to publish research findings in academic journals. 10 The Open Access principles are also reflected in FAIR principles, which provide guidelines for ensuring data and resources are Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable. 11

While there is widespread support for the Open principles, more recently it has become evident that not all data—and especially sensitive personal data such as health or genomic data—are appropriate for Open Access and unrestricted re-use. Furthermore, depending on the national privacy legislation and Health Act in place, reusing certain kinds of sensitive data without participant consent or moving these data across borders may be illegal. Not all data can be made Open in line with Open Access principles, for example some large datasets and real-world data are generated without informed consent from individuals and yet are granular enough to potentially be used to reidentify individuals if combined with other identified data resources. 12 A prominent example is the use of anonymised health datasets generated from routine health data or electronic medical records, which carry the potential risk of reidentification of health clients who have not consented to participate in research, have not been informed of the risk of reidentification, and have not had an opportunity to choose whether their sensitive health data are used for research. 13 The epidemiological and health systems value of mining these data is undisputed, but the risks posed to unwitting participants should be absolutely minimised given the circumstances under which the data are generated and used.

Another scenario in which Open secondary use cannot always be implemented occurs with legacy datasets which were collected in the past at a time when legislation and general research practices were much more permissive about data collection without detailed informed consent, during which time uniquely identifying data such as genomic data may have been generated without the knowledge or agreement of those individuals or without their explicit consent for secondary data use. These data cannot ethically be handed on to additional researchers without participant informed consent for secondary use, as this would expose participants through the use of their data to associated risks—to which they have not agreed.

With the rapid growth of genomic data generated from global populations there is increasing recognition of the potential for additional family and community harms that might arise from the analysis of these data. 14 Although individual informed consent might be in place, consideration must equally be given to the risks of onward data use for relatives, associated communities and identifiable population groups. If an individual’s genomic data are Open and identifiable, what might be the implications for their offspring or relatives who did not consent to the use of those data? How are communities affected when their population-level genetic or epidemiological data become open information, for example stigma that might arise when high risk genetic variants or particular diseases are associated with a specific population group? The community-level impact of genomic studies with San participants in Southern Africa clearly illustrates these risks. 15 16 Responsible data governance, sharing, analysis and reporting are particularly important to support the inclusion of underrepresented populations in health research, in order to ensure that innovations and new therapeutic approaches are equitable and effective for all populations groups; and equitable and appropriate sharing of data from under-represented groups can contribute to addressing the existing bias in health research. 17–19

Fortunately, together with the growing availability of granular and identifying datasets and a concomitant growing recognition of the need to protect the interests of individuals, communities and researchers, there has been rapid growth in the development of data governance and ethical data use to address these challenges. Traditionally, Open data sharing has been viewed as a unidirectional process whereby researchers who collect and generate data pass them onward for secondary use, either directly or via centralised repositories. In the process they must usually cede any control over how the data are used further. Recently, more nuanced approaches are being developed to ensure maximal ethical secondary use of data resources while minimising risks and respecting the level of informed consent provided by participants.

Here, we provide an overview of four different approaches to data sharing that can be adopted according to data sensitivity and/or restrictions on secondary use. We discuss direct data sharing in a traditional model; collaborative data sharing which facilitates research by combining datasets and undertaking meta-analysis involving all collaborating partners; federated data analysis, in which partners undertake synchronous and harmonised analyses on their independent datasets and then combine the results of their analyses in a final coauthored report; and the use of trusted research environments (TREs) in which data may be analysed in a controlled environment from which only aggregate research results may be exported. We also review how deidentification and anonymisation methods can reduce the risks associated with secondary use of health data. In addition, we present a modularised approach for building data-sharing agreements (DSAs), with a framework that can be used to build such an agreement for each of these scenarios. This provides a new approach to building such agreements that is accessible and manageable for researchers without prior experience in drafting such memoranda.

We have focused here primarily on sharing of data which have been generated directly from individuals and/or biospecimens collected from individual participants. Many of the principles we outline here can similarly be applied to secondary use of biospecimen collections, and while the re-use of biospecimens is not covered exhaustively we have noted some areas where these data-sharing principles may also relate to the sharing of biospecimens.

Modes of data sharing

Here we discuss four modes of secondary data sharing that may accommodate some of the challenges associated with sharing data and conducting meta-analyses, as outlined in table 1 .

- View inline

Key advantages and challenges for different modes of secondary data sharing

Direct sharing

Direct data sharing is the traditional model of data sharing which has been most commonly in use and is routinely required by funders and peer-reviewed journals. In this model, the researcher who has generated data, the data producer, provides a full set of the data to other users, data consumers, for all types of secondary use ( figure 1 ). This may be done via a specific centralised repository—for example, the H3Africa programme ( www.h3africa.org ) funders require submission of genomic data from the programme to the European Genome-Phenome Archive ( https://ega-archive.org/ ) and submission of biospecimens to centralised H3Africa biorepositories. 20 Controlled access for secondary use occurs under the oversight of a Data and Biospecimen Access Committee, 21 and an embargo period formalises a time period for which the data generators have protected access to the data for analysis and publication to ensure they are not scooped by secondary users. Another example is the Research Resource for Complex Physiologic Signals (PhysioNet, https://physionet.org/about/ 22 ), which offers free access to large collections of physiological and clinical data, while facilitating a level of control over the data by resource generators and promoting collaboration and data sharing.

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Direct sharing. Unidirectional transfer of resources from generator to consumer. The consumer performs data analysis and generates the research output.

A central challenge for direct sharing of health data is how to ensure that the privacy of participants is maintained. 23 While it remains impossible to anonymise genomic data, which is by its intrinsic nature identifying, 24–26 participant safe-guarding for the use of highly granular clinical and epidemiological data can be achieved through data deidentification, anonymisation and also data perturbation. As large datasets become increasingly granular and health metrics become increasingly precise, the opportunity to reidentify individuals through cross-reference with other records does become higher—for example, given the dates and locations of sequential health facility visits together with participant age and comorbidity profile it becomes feasible to reidentify a study participant through cross reference to identified routine health facility records. Legislation that protects privacy increasingly recognises the sensitivity of health data and may offer specific protections in addition to national Health Acts that enshrine healthcare client confidentiality. An example of this is the Protection of Personal Information Act in South Africa which categorises health data as ‘special’ data, requiring additional considerations and protections. 27

Collaborative meta-analysis

Whereas direct data sharing results in a unidirectional transfer of data without collaborative opportunities, growing use of data standards has provided greater opportunities to harmonise datasets and combine them for collaborative meta-analysis. 28 In this model, data generators work together to combine their anonymised datasets and then conduct analyses that provide more statistical power and generalisable findings than when analysing the individual datasets ( figure 2 ). Sometimes in these studies it is also possible to have discovery and validation dataset analysis to measure the generalisability of findings from particular analyses. A significant advantage of collaborative meta-analyses is that the data generators have oversight of the onward use of the data they have generated and can ensure that ethical and informed consent constraints are respected. In addition, they are able to receive recognition for the ongoing analysis of the data they have generated, which can contribute to ensuring sustainability of their research and avoid their work being ‘scooped’ before they have brought it to publication. 29 This attribution is particularly important in under-resourced research environments where securing research grants is both difficult and also essential for sustainability.

Collaborative meta-analysis. Generators combine their resources and do a joint meta-analysis on the combined dataset. The generators do a joint analysis and generate a collaborative research output.

One of the major challenges for performing meta-analyses is the combination of large datasets which may have different data structures and captured variables, even when they are addressing similar primary research questions. The process of data harmonisation and associated data quality checking can be extremely time and resource-consuming, and requires the development of common data models. For example, The International Epidemiology Databases to Evaluate AIDS consortium developed these tools, and used the OMOP common data model ( https://ohdsi.github.io/CommonDataModel/index.html ) in order to combine international datasets from studies of populations living with HIV/AIDS across multiple countries for meta-analysis and comparative studies. 30 Large consortia such as the Global Genomic Medicine Collaboration 31 ( https://g2mc.org/ ), Global Alliance for Genomics and Health 32 ( https://www.ga4gh.org/ ) and International HundredK+Cohorts Consortium 33 ( https://ihccglobal.org/ ) now contribute significant resources into developing data standards for wider use, to enable such meta-analyses using health, epidemiological and genomic data without requiring retrofitting and retrospective harmonisation of data for meta-analysis.

Federated analysis

In some cases, data use permissions, ethical constraints or informed consent limitations mean that data may not be shared with other parties in direct transfer or collaborative meta-analysis agreements. In addition, for very large datasets their size may also prohibit routine transfer of datasets for secondary use. In these cases, federated analysis is another approach that may be used to optimise secondary knowledge generation from datasets that cannot be shared. For the federated data analysis model, datasets are held separately by collaborating parties but are analysed locally in the same way, and then aggregate data and/or findings are combined and reported jointly ( figure 3 ). The complete, granular datasets are never shared and never combined, and the analyses are run by the data generators only on their local dataset. This approach is used increasingly because it can circumnavigate some of the more difficult logistical, procedural and practical challenges that can hinder meta-analyses 34 35 —as described in oncology research using routine health data, 36 and pharmaco-epidemiology networks, 37 by way of example.

Federated analysis. Researchers independently conduct the same analysis on their own datasets and then combine their analysis outputs. Only the independently generated analysis results are combined in a joint research output.

Similar to collaborative meta-analysis, datasets for federated analysis still need to be comparable so that aggregate results and analysis outputs may be compared and/or combined, but the requirement for an exact replication of data structure and coding is less rigorous, even though federated analysis still requires common data elements and care needs to be taken to ensure that analysis outputs are comparable. 38 Standardised univariate data exploration of the data from each collaborator can help to flag existing biases in any of the contributory datasets. An additional application of this approach for multicentre collaborative studies is for a single data infrastructure to be created, but with partitioning that allows each centre control of and access to only their own data in the database. 39 An implementation example for federated database access is the assignment of Data Access Groups in REDCap databases, 40 ensuring user groups are only able to see certain records in the database that are entered by members of their own user group although the common data structure is used by all. Increasingly, researchers are also practicing federated learning whereby only algorithm weightings are shared and can be integrated by all collaborators in order to build a final model. 41

A Trusted Research ecosystem

As data-sharing models evolve, it has become evident that many researchers wishing to undertake secondary analysis on shared datasets will do so in a responsible and considered way, and that trusted and validated users may be able to run their own analyses directly on large datasets under controlled conditions.

A Trusted Research Environment

Generating and managing datasets for sharing can be a time-consuming, labour-intensive task that is often not recognised in assignment of budgets and personnel time. As datasets become ever larger, the number of data consumers wishing to use those data are also rapidly increasing, and many of these are repeatedly requesting related datasets. Organisations holding such large datasets have begun creating platforms where trusted users are able to directly query the complete dataset without visualising the personalised data or extracting any sections of the dataset for download. 42 In this online environment, the data consumer can run their required data analyses and export only the output and aggregated results ( figure 4 ). This provides the data provider with full control over the access and use of the shared data, while enabling secure access to data for appropriate research purposes. Ongoing query logging tracks the user activities on the platform to ensure accountability. Some examples of TREs include the UK’s Secure Data Environment server ( https://digital.nhs.uk/services/secure-data-environment-service ) for research access to anonymised health service patient data; the UK Biobank Research Analysis Platform, 43 the Terra platform developed by the Broad Institute ( https://terra.bio/about/mission/ ) and the Seven Bridges Platform ( https://www.sevenbridges.com/platform/ ).

Trusted Research Environment. Researchers register for an account that allows them access to a dataset on a secure platform where they can run analyses and generate outputs, but can only download and take away the outputs of the analyses without copying, downloading or retaining the raw data. Researchers generate independent analyses and research outputs from a common data source.

Trusted third party for data linkage, anonymisation and perturbation

Linking datasets from disparate data sources but for the same group of individuals can provide important epidemiological and health insights. In some legislative circumstances, this kind of analysis can only be done using anonymised data which creates the paradox in which identifying data fields are required to perform the linkage, but should not be revealed to the researchers using the linked dataset. In these circumstances, data linkage and subsequent anonymisation and perturbation of the linked dataset may be undertaken by a trusted third party who provides the linkage facility but has no further investment or involvement in the provided and output datasets. This third party will sign a non-disclosure agreement or memorandum of understanding regarding confidentiality, data protection and non-use of the data, as well as committing to deleting all data related to the linkage process within a specified time frame.

Additional considerations for data sharing

Considerations for commercial use of data.

Use of data for commercial use is a specific use case that comes with many additional and specific complexities. These include IP and potential licensable and/or patentable output. Because of the complexity and the difficulty in generalising these kinds of DSAs, in this study we have focused on sharing for academic research, recognising that the legal and ethical complications of data sharing for commercial purposes require an in-depth review that is beyond the scope of the current analysis.

Data deidentification and anonymisation

Data deidentification and data anonymisation refer to the processes of preparing, managing and distributing datasets removed of personally identifiable information. This is important in multicentre health research studies, for example, to provide a scalable and secure way for sharing medical information from health service records while safeguarding the privacy of patients. 44 These approaches can also alleviate concerns that consent requirements for the use of identified data negatively impact research cost, recruitment rates, research duration and outcomes and may also exacerbate recruitment bias (reviewed in 45–47 ).

Data deidentification is a process used to remove or replace the patient identifiers, such as name and identity number, from private records to prevent the relinking of the personally identifiable data to the data subject. 44 At the earliest opportunity, personal identifiers of the medical data are encrypted and the deidentified dataset is stored in a separate database. An internal anonymous key is used to link the deidentified data with the attribute data, and the dataset is always differentially perturbated for each dataset release to prevent linkage of independent datasets released leading to reidentification. Necessary access to databases with personally identifiable information, for example by database developers or analysts undertaking data linkage or curation, is tightly managed and restricted to absolute instances and subjected to both specific approvals and governance undertakings. Such data deidentification still allows for the future reassociation between the personally identifiable data and the individual, and similarly pseudonymisation replaces personally identifiable information with pseudonyms with a separate lookup table that can map pseudonyms to personally identifiable information. True data anonymisation, however, removes this association while preserving the utility of the information as much as possible.

Data perturbation is the addition of alterations or noise to the data to prevent the reidentification of the study participants and can be applied on different types of datasets to protect both privacy and confidentiality, including analysis extracts, research extracts without informed consent, and data in databases that are used for maintenance and development work within data storage environments. 48 Some examples of simple types of data perturbation include using only year of birth rather than date of birth; adding an undisclosed integer to all event dates so that times between key dates remain unchanged but reidentification through date-defined events is minimised, and using age in years at an event rather than providing birth year or event dates. More advanced statistical approaches may also be used to ensure privacy, providing a framework for ensuring that it is very difficult to infer information about individuals from a dataset while ensuring results of analyses remain true to the underlying dataset. 49 50 Anonymisation techniques are vulnerable to reidentification attacks using auxiliary datasets to compromise the privacy of data subjects, and it is advisable to apply perturbation to as many fields as possible for all requests, with perturbation techniques varying per request depending on the intended research questions and ethical concerns. Techniques and metrics such as k-anonymisation and metrics such as l-diversity can be used to reduce these risks. 44 51

Data-sharing agreements

A DSA is a formal document which allows for the regulation of data exchange between data generators and consumers in a controlled manner. This is done by defining a priori specific guidelines and procedures agreed on by both parties on what is required, permissible or denied with respect to data covered by the agreement. 52 While there are multiple clauses in a DSA ( table 2 ), in this paper we have focused on informed consent, benefit sharing, IP, intended outputs and authorship, attributions and acknowledgements as they are central to ensuring ethical and equitable data sharing among researchers, and can often be focal points for contention if they are not established up front. Online supplemental table S1 provides descriptions of some of the most commonly included DSA elements.

Supplemental material

Data sharing agreement modules for four types of data sharing

Informed consent

Consent protocols and documents must be robust, and those conducting the primary study need to ensure that relevant consent that allows for secondary use of the data is in place, and that the consent documents are aligned with the intended onward use of the data and/or biospecimens. 53 This is essential for direct sharing where control over secondary use is completely relinquished and the primary data generators lose oversight of the onward use of the data. In addition, if any commercial onward use is intended, participants need to have specifically consented for the use of their data for commercial purposes, and any share in profits or benefits from such onward use, or lack thereof, needs to be clearly identified in the consent information for the participants.

Benefit sharing

Generating primary data in under-resourced settings is often a challenging and expensive undertaking for researchers, and participation in research may itself be challenging in under-resourced environments. There is, therefore, an ethical imperative to ensure maximal return of benefits from onward sharing of these data. Such benefit sharing is often overlooked, especially for secondary use of data. While collaborative and federated sharing and the use of TREs ensure that the primary data generators are still involved in the secondary use of data, in the case of direct sharing consideration should be given to ensuring both the data generators and research participants might benefit from the secondary use of their data. While benefit sharing is not yet commonly inculcated in research planning, there is increasing recognition of the need to plan for benefit sharing, and available frameworks provide guidance for implementation. 54 For non-human genetic resources, such benefit sharing is governed by the access and benefit-sharing provisions of the United Nations’ Convention on Biological Diversity and its supplementary Nagoya Protocol. These agreements recognise that countries have the sovereign right to regulate access to their genetic resources. It is uncertain whether digital sequence information (DSI) associated with those genetic resources are included in these agreements, but since December 2022, processes are underway to incorporate DSI in the benefit-sharing accords. 55 It is also important to recognise that benefit-sharing protocols may need to be tailored according to the specific requirements of under-represented population groups. 15 56

Intellectual property

For all modes of data sharing, ownership of the current and future IP rights associated with the shared data must be clearly assigned, and this should be done a priori to avoid problems arising in the future. In addition, as this has legal implications this element of DSAs should be compiled with the input of legal and/or technology transfer departments at the institutions of the parties entering into the DSA.

Intended output

A detailed description of the intended or anticipated outputs from the shared data, such as manuscripts, training materials, tools and products, needs to be described in detail a priori to ensure that they align with the consent provided by participants, especially in the case of direct sharing where control of the data is relinquished by the data producers and they lose oversight of onward data use. Having clearly defined outputs can also strengthen collaborative and federated analysis, by ensuring that the parties involved are working towards explicit common goals, and that they also do not accidentally infringe on each other’s independent research agendas.

Authorship, attribution and acknowledgements

Agreement on the authorship and attribution plan for outputs generated from the data and/or biospecimens should be reached and recorded in DSAs. For academic output, documenting first, senior and corresponding authorship in future publications arising from the agreed data sharing can focus collaborators’ roles and prevent disputes down the line. For direct sharing, the data generators should also be adequately acknowledged in research outputs emanating from the secondary use of the data that they have made available. In collaborative and federated DSAs, this can ensure that such agreements do not disadvantage any of the partners, and ensuring this kind of equity is especially important where partnerships occur between more established and early career researchers, between highly resourced and poorly resourced research groups, and between researchers in the global North and global South. 57 To foster equity in research, there is increasing recognition of the need to encourage primary data generators from under-resourced environments and the global South to take active roles in subsequent research using the datasets they generated, and to take on senior author roles in subsequent publications.

The value to be derived from secondary use of data and biospecimens is undisputed. It is more complex, however, to ensure that such secondary use of resources is done in a way that is ethically sound and respects the preferences and privacy of the participants who donated those resources for research. In addition, there is increasing awareness of the need for equitable research agreements that do not reinforce the inequitable research dynamics that have been common to date.

Here, we have described four different modes of data sharing that may provide ways for ethical secondary use of data, including ways of sharing that might be used where data cannot be directly shared onwards to third parties. This need arises most frequently in situations where data are particularly sensitive, where informed consent for secondary analysis has not been provided by research participants, and for legacy datasets for which terms of consent were insufficient or not documented. While direct, unidirectional sharing has been the most common mode of sharing to date, with increasingly granular health and personal data the risks to individual participants of reidentification and breach of privacy are also increasing. We have outlined here some of the approaches used for data deidentification, anonymisation and perturbation, which all increase the security of participants when their data are shared onward for secondary analyses. As the global repositories of granular personal data rapidly expand, the availability of data to triangulate for reidentification of individuals also increases along with the risk of data breach, with the consequence that these approaches to prevent reidentification by anonymisation and perturbation are more important than ever before.

We anticipate that the development of more nuanced data-sharing models such as those described here may facilitate DSAs which might not have previously been possible. For example, a common concern of data generators is that they do not wish to lose oversight of how the data they have collected from participants are being used by other researchers; and another is that data generators, especially those with fewer resources for data analysis, might be scooped by better resourced research groups as soon as they make their data resources available. The options for collaborative meta-analysis and federated analysis both provide models in which these concerns are fully addressed without hindering the possibility of onward use of data resources. Concerns about data privacy, the potential for misuse of sensitive data and risks to participant privacy may also be taken into consideration through federated analysis or the use of a TRE. These data-sharing solutions do not require centralisation of data and provide opportunities to negotiate collaborative secondary research and benefit-sharing, and we have also provided an overview of the types of clauses which should be included in DSAs using these approaches.

We have, in this way, approached the challenges for secondary sharing of sensitive health data with a solutions-based lens, proposing different models of data sharing that can overcome common barriers to secondary analysis. While the approaches we have described are not exhaustive, we hope to encourage creative thinking that moves beyond direct, unidirectional sharing for secondary use, and to facilitate collaborative and equitable data sharing that can effectively advance and support a growing evidence base for the provision of optimal healthcare.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication.

Not applicable.

- Bittencourt MS

- Churchill D

- Bloomrosen M ,

- ↵ Afraid of Scooping – Case Study on Researcher Strategies against Fear of Scooping in the Context of Open Science , Available : https://datascience.codata.org/articles/10.5334/dsj-2017-029/ [Accessed 27 Apr 2018 ].

- Centre for Open Science

- ↵ Budapest Open Access Initiative , Available : http://www.budapestopenaccessinitiative.org/ [Accessed 28 Jan 2018 ].

- Zahuranec AJ ,

- Verhulst SG

- McKiernan EC ,

- Bourne PE ,

- Brown CT , et al

- The FAIR Data Principles

- Panagiotakos D

- Hendrickx JM ,

- de Montjoye Y-A

- Diallo AA ,

- Dearden PK , et al

- Schroeder D ,

- Hirsch F , et al

- Osuafor CN ,

- Golubic R ,

- Cellini J ,

- Charpignon M-L , et al

- Martínez-García M ,

- Villegas Camacho JM ,

- Hernández-Lemus E

- Croxton T ,

- Abimiku A , et al

- Beiswanger CM ,

- Abimiku A ,

- Carstens N , et al

- Goldberger AL ,

- Amaral LAN ,

- Glass L , et al

- Culnane C ,

- Rubinstein BIP ,

- Pe’er I , et al

- McGuire AL ,

- Golan D , et al

- Narayanan A

- Information Regulator South Africa

- Schmidt B-M ,

- Colvin CJ ,

- Hohlfeld A , et al

- Gomes DGE ,

- Pottier P ,

- Crystal-Ornelas R , et al

- Stephens J ,

- Musick B , et al

- Ginsburg GS

- Knoppers BM

- Manolio TA ,

- Goodhand P ,

- Jochems A ,

- van Soest J , et al

- Holmes JH ,

- Shah K , et al

- Bardenheuer K ,

- Passey A , et al

- Brown JS , et al

- Dawoud D , et al

- Ganzinger M ,

- Blumenstock M ,

- Fürstberger A , et al

- Van Bulck L ,

- Wampers M ,

- Li W , et al

- UK Health Data Research Alliance

- Kushida CA ,

- Nichols DA ,

- Jadrnicek R , et al

- El Emam K ,

- Dankar FK ,

- Issa R , et al

- Kosseim P ,

- Tiffin N , et al

- Bangash AH ,

- Alraoui O , et al

- Tamuhla T ,

- Bedeker A ,

- Nichols M ,

- Allie T , et al

- Scholz AH ,

- Freitag J ,

- Lyal CHC , et al

- Liggins L ,

- Burgess RA , et al

Supplementary materials

Supplementary data.

This web only file has been produced by the BMJ Publishing Group from an electronic file supplied by the author(s) and has not been edited for content.

- Data supplement 1

Handling editor Seye Abimbola

Contributors NT designed the study. TT compiled datasharing agreement section, ETL and TM compiled data anonymisation section. All authors contributed to writing, editing and reviewing the manuscript.

Funding This work is supported by the African Data and Biospecimen Exchange Project, funded by a Calestous Juma Fellowship (PI: Nicki Tiffin, INV-037558) from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. NT, ETL and TT are supported by funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (The African Data and Biospecimen Exchange, INV-037558), NT, TT and TM are funded by the UKRI/MRC (award number MC_PC_22007).

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

- Policy and Social Care Move Fast: How…

Policy and Social Care Move Fast: How Rapid Qualitative Methods Can Help Researchers Match Their Pace

Date posted:.

The field of social care integration, which refers to the study and implementation of clinically based programs to address the social needs of patients and families, is advancing at an increasingly rapid pace. This acceleration, driven by heightened need post-pandemic as well as mandates at the state and federal levels for health systems to implement screening and referral programs, has increased the urgency for high-quality evidence to support policy decisions about the delivery of social care—in other words, how health systems identify and address social needs, like access to healthy food and safe housing.

Qualitative research is particularly useful in guiding social care integration as it can shed light on the patient or caregiver experience of participating in social care interventions, barriers to getting help that should be addressed, and appropriate next steps from the perspective of those directly impacted.

However, traditional qualitative data analysis can be time consuming, and evidence-based solutions for addressing families’ social needs from the clinical setting are needed in the short term. In this post, I’ll share how we adapted and applied rapid qualitative methods to a social care-focused study as an example of how this approach can be used to inform social care integration in real time.

Integrating a Rapid Research Approach

The Socially Equitable Care by Understanding Resource Engagement ( SECURE ) study is a mixed method pragmatic trial aimed at understanding how best to increase family-level engagement with social resources from the pediatric health care setting. Caregivers in the study were randomized to complete one of three different social assessments (surveys asking about their social circumstances and/or desire for social resources) before receiving a resource map on their personal smartphone where, if interested, they could search for community resources in their neighborhood. Caregivers also had the option of talking to our study-specific resource navigator to receive additional support finding resources.

The overall goal of the qualitative component of the study is to capture caregivers’ preferences and experiences receiving social care through SECURE. Our traditional qualitative protocol involved transcribing caregiver interviews verbatim, coding transcripts and conducting thematic analysis. Recognizing the need for implementation-oriented results on a fast timeline, our team explored rapid qualitative methodologies to supplement the traditional approach. The rapid methods we chose were derived from existing literature on rapid qualitative approaches, which were then adapted to suit our study’s protocol and the social care field in general.

In our rapid approach, interviewers took notes using a structured template during or immediately after each caregiver interview. The template was designed to capture the data most salient to social care integration efforts such as caregiver’s likes, dislikes and preferences about receiving social care at their child’s doctor’s office. Then, content from the templates was transposed onto an analytic matrix, where we compared data across participants to identify themes. While we explored the full range of themes that emerged from our caregiver interviews in traditional qualitative analysis, we wanted to be sure that rapid analysis focused on findings that would be most applicable to social care integration efforts so the results could inform social care policy at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) and elsewhere in real time. For example, what parts of participating in SECURE were helpful for caregivers? Did anything make them uncomfortable?

To ensure that our rapid approach produced results in line with those generated through traditional methods, we analyzed ten of our interviews using both traditional and rapid methods and compared the results. This analysis yielded a 92.8% theme match—meaning the two qualitative methods yielded largely the same themes. This builds upon previous literature, indicating that rapid analysis can be an effective tool in capturing implementation-oriented themes from qualitative data.

How the SECURE Study Can Inform Future Research Efforts

Our rapid qualitative methods allowed us to effectively adapt and respond to the quickly evolving landscape of social care integration, even before we had the full study results. I personally saw this first-hand while working with the SECURE team in 2023 conducting caregiver interviews. For example, we were able to inform hospital efforts in response to a recent insurance requirement of health systems to share caregivers' responses to social screening questions. We successfully gathered patients’ feedback on this new requirement and shared this information and suggestions for what CHOP could do to make caregivers feel more comfortable answering social assessment questions.

While not intended to replace traditional qualitative analysis, being able to produce actionable qualitative findings in a timely manner through rapid methods has allowed SECURE findings to help shape social care interventions at CHOP and beyond in real time.

Our hope is that other researchers in social care who face time pressures may find similar rapid qualitative methods as a useful and effective approach to adapt to the dynamic nature of the field and generate family-centered solutions faster than would otherwise be possible.

Latest Blog Posts

The Heat Is Turned Up: Focus on Climate Solutions for Kids

2023 was the hottest year on record and 2024 is predicted to rank among the top five warmest years. Extreme heat at this scale can be a danger to not…

A Sense of Purpose Can Support Teen Mental Health

Adolescence–the years between about 10 to about 25–is an essential time to help young people proactively build positive mental health and well-being…

Q&A: Engaging Communities to Alleviate Period Poverty with Lynette Medley

There are 16.9 million women, girls and all other people who experience a menstrual cycle in the United States living in poverty, many of whom are…

Check out our new Publications View Publications

Adolescent Health & Well-Being

Behavioral health, population health sciences, health equity, family & community health.

Qualitative Research – a practical guide for health and social care researchers and practitioners

(0 reviews)

Darshini Ayton, Monash University

Tess Tsindos, Monash University

Danielle Berkovic, Monash University

Copyright Year: 2023

Last Update: 2024

ISBN 13: 9780645755404

Publisher: Monash University

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Table of Contents

- Acknowledgement of Country

- About the authors

- Accessibility statement

- Introduction to research

- Research design

- Data collection

- Data analysis

- Writing qualitative research

- Peer review statement

- Licensing and attribution information

- Version history

Ancillary Material

About the book.

This guide is designed to support health and social care researchers and practitioners to integrate qualitative research into the evidence base of health and social care research. Qualitative research designs are diverse and each design has a different focus that will inform the approach undertaken and the results that are generated. The aim is to move beyond the “what” of qualitative research to the “how”, by (1) outlining key qualitative research designs for health and social care research – descriptive, phenomenology, action research, case study, ethnography, and grounded theory; (2) a decision tool of how to select the appropriate design based on a guiding prompting question, the research question and available resources, time and expertise; (3) an overview of mixed methods research and qualitative research in evaluation studies; (4) a practical guide to data collection and analysis; (5) providing examples of qualitative research to illustrate the scope and opportunities; and (6) tips on communicating qualitative research.

About the Contributors

Associate Professor Darshini Ayton is the Deputy Head of the Health and Social Care Unit at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia. She is a transdisciplinary implementation researcher with a focus on improving health and social care for older Australians and operates at the nexus of implementation science, health and social care policies, public health and consumer engagement. She has led qualitative research studies in hospitals, aged care, not-for-profit organisations and for government and utilises a range of data collection methods. Associate Professor Ayton established and is the director of the highly successful Qualitative Research Methods for Public Health short course which has been running since 2014.

Dr Tess Tsindos is a Research Fellow with the Health and Social Care Unit at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia. She is a public health researcher and lecturer with strong qualitative and mixed methods research experience conducting research studies in hospital and community health settings, not-for-profit organisations and for government. Prior to working in academia, Dr Tsindos worked in community care for government and not-for-profit organisations for more than 25 years. Dr Tsindos has a strong evaluation background having conducted numerous evaluations for a range of health and social care organisations. Based on this experience she coordinated the Bachelor of Health Science/Public Health Evaluation unit and the Master of Public Health Evaluation unit and developed the Evaluating Public Health Programs short course in 2022. Dr Tsindos is the Unit Coordinator of the Master of Public Health Qualitative Research Methods Unit which was established in 2022.

Dr Danielle Berkovic is a Research Fellow in the School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia. She is a public health and consumer-led researcher with strong qualitative and mixed-methods research experience focused on improving health services and clinical guidelines for people with arthritis and other musculoskeletal conditions. She has conducted qualitative research studies in hospitals and community health settings. Dr Berkovic currently provides qualitative input into Australia’s first Living Guideline for the pharmacological management of inflammatory arthritis. Dr Berkovic is passionate about incorporating qualitative research methods into traditionally clinical and quantitative spaces and enjoys teaching clinicians and up-and-coming researchers about the benefits of qualitative research.

Contribute to this Page

Secondary Research Methods

- Secondary research methods involve using data that has already been collected by others.

- This type of research is useful for gaining a broader understanding of a topic.

- It can validate primary research findings and provide context for new research.

Existing Statistical Data

- Existing statistical data refers to numerical data that has already been collected.

- This data often comes from government databases , research studies, or organisational records.

- Pros: large amounts of data available, often from reliable sources.

- Cons: may not be tailored to your specific research question, and the quality or relevance of data may vary.

Literature Reviews

- Literature reviews involve a detailed exploration of existing academic literature related to a topic.

- This can include academic journal articles , books, and conference papers.

- Pros: can identify gaps in existing research and provide context for your study.

- Cons: can be time-consuming to find and analyse relevant literature.

Media and Document Analysis

- Media and document analysis involves critiquing media sources such as newspapers, films, and online content, or organisational documents like policies, minutes of meetings etc.

- It can provide insight into public opinion, societal trends, or internal company perspectives.

- Pros: easy to access and may provide a cultural or societal perspective.

- Cons: may contain bias and may not be directly applicable to your research question.

Internet Research

- Internet research involves accessing online information related to your topic.

- This can include websites , online publications, blogs, social media sites, forums, and digital archives.

- Pros: can access a vast amount of information quickly, and often free.

- Cons: quality and credibility of information varies greatly, and outdated content is common.

When using secondary research, it is crucial to evaluate the source’s credibility , check for potential bias , and understand the context in which the data was collected. Keeping ethical considerations in mind such as intellectual property rights and data privacy is also essential.

Cookies on the NHS England website

We’ve put some small files called cookies on your device to make our site work.

We’d also like to use analytics cookies. These send information about how our site is used to a service called Google Analytics. We use this information to improve our site.

Let us know if this is OK. We’ll use a cookie to save your choice. You can read more about our cookies before you choose.

Change my preferences I'm OK with analytics cookies

Embedding research in the NHS

Research is vital in providing the evidence we need to transform services and improve outcomes, such as in developing new models of care, redesigning urgent and emergency care, strengthening primary care and transforming mental health and cancer services. Research is the attempt to derive generalisable or transferable new knowledge .

The NHS benefits greatly from delivering research directly, not only in terms of breakthroughs enabling earlier diagnosis, more effective treatments and improved system design, all of which improve patient care and health outcomes, but also increased workforce satisfaction and retention and patient and carer experience. Mortality is lower in research active hospitals. The NHS also benefits financially from delivering research.

The purpose of the Embedding Research team in NHS England is to enable the NHS to increase the scale, pace and diversity of those taking part in research and to provide system guidance and assurance.

Guidance is available to help integrated care systems to maximise the benefits of research for their diverse populations. This guidance sets out what good research practice looks like and supports integrated care boards in fulfilling their research duties. Guidance is also available to help NHS organisations manage research finance in the NHS . This guide provides practical information on costing research and the use of income generated by research to support building research capacity and capability.

NHS England a key research delivery partner

NHS England is a proud partner of The Future of UK Clinical Research Delivery – a collective vision to realise the full potential of clinical research to make the UK one of the best places in the world to conduct clinical research.

Through a cross-sector, collaborative approach, NHS England works closely with the rest of the UK’s clinical research system on a coordinated and coherent programme of work that has been developed to ensure the resilience and growth of the UK’s clinical research sector.

Using The Future of UK Clinical Research Delivery as the collective vision, this continuous improvement programme aims to deliver faster, more efficient and more innovative clinical research through 5 overarching themes that underpin the programme of work.

- A sustainable and supported research workforce to ensure that healthcare staff of all backgrounds and roles are given the right support to deliver clinical research as an essential part of care.

- Clinical research embedded in the NHS so that research is increasingly seen as an essential part of healthcare to generate evidence about effective diagnosis, treatment and prevention.

- People-centred research to make it easier for patients, service users and members of the public across the UK to access research and be involved in the design of research, and to have the opportunity to participate.

- Streamlined, efficient and innovative research so that the UK is seen as one of the best places in the world to conduct cutting-edge clinical research, driving innovation in healthcare.

- Research enabled by data and digital tools to ensure the best use of resources, leveraging the strength of UK health data assets to allow for more high-quality research to be delivered.

Key activity undertaken in support of this vision includes guidance for health professionals. Many health professionals combine research and providing care in the NHS. The following publications have been published by NHS England to support this:

- The guidance Making research matter sets out a policy framework for developing and investing in nursing related research activity across the NHS.

- The Allied health professions’ research and innovation strategy for England contains a definitive collective national reference statement that encompasses and supports the existing research and innovation strategies of all the allied health professional associations.

- NHS England has published the self-assessment of organisational readiness tool: a guide to improve nursing research capacity in health and care . The tool helps organisations to assess their preparedness for supporting the Chief Nursing Officer for England’s strategic plan for research.

- Guidance has been published to support the involvement of NHS workforce in health and social care research. The Multi-professional practice-based research capabilities framework highlights and promotes active involvement in research as an integral component of practice for practice-based health and care professionals.

- In addition, a UK survey of pharmacy professionals’ involvement in research has resulted in this report with recommendations to inform a clinical academic career pathway for pharmacy, which supports embedding research at all stages of a pharmacy professional’s career.

NHS England works closely with the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR), which provides funding for research studies as well as academic training, facilities, career development and research capability development. In addition, through Be Part of Research NIHR supports participation on research in a wide range of long-term conditions, diseases and disabilities. See the NIHR website for more information on NIHR’s support offer.

Developing treatments for all: Increasing diversity in research participation

Health research plays an integral part in how the NHS develops services and continues to provide high quality healthcare for our population. However, NIHR data has revealed that UK geographies that experience high rates of disease also have the lowest number of patients taking part in research. The areas where there are the lowest levels of research participation also align closely to areas where incomes are lowest, and indices of deprivation are highest. This means that research is often conducted with individuals who are healthier and wealthier, and lacks representation from our diverse society.

It is important that people from different communities have the opportunity to participate in research to ensure that treatments, technologies and services reflect the needs of our diverse population. NHS England has committed to increasing participation in the research taking place in the NHS.

The Research Engagement Network Development Programme aims to increase diversity in research participation through the development of research engagement networks with communities who are often underserved by research, and by ensuring diversity in research is considered by integrated care systems (ICSs).

Launched in 2022, NHS England and the Department of Health and Social Care have funded all 42 ICSs in England to grow their local research engagement networks by working with local voluntary, community and social enterprises to engage underserved communities. In addition, a further 9 teams have been funded to plan how to address specific existing barriers to inclusion in research such as language, cultural barriers and/or age limitations and/or restrictions across a range of conditions and clinical or care settings.

NHS England has published Increasing diversity in research participation: a good practice guide for engaging with underrepresented groups , which provides practical insights for researchers on how to engage more diverse participants in health research. More diverse participation will help ensure that the health service continues to serve and be available to all.

Professional/Short course Health and Social Care Research: Methods and Methodology

15 or 20 credit level 7 module (online learning option available).

Due to the places required from our partnership organisations outweighing the actual places available on this module, it will not be opened up to general applications until six weeks before the start date. Please contact your employer to see if you are eligible to apply, they will supply you with the relevant links to undertake this process.

Page last updated 30 November 2023

Introduction

The Health and Social Care Research: Methods and Methodology level 7 (Masters level) module is available at both 15 (UZWSPX-15-M) or 20 (UZWRGQ-20-M) credits. There is also a 15 (UZWSRV-15-M) or 20 (UZWYGP-20-M) credit online learning module option available.

These 15 or 20 credit level 7 module, Health and Social Care Research: Methods and Methodology, will give you an overview of:

- the current state of research in health and social care, including, for example issues of funding, the formulation of research questions, the relationship between evidence and practice and the implementation of research findings in different settings

- the access, use and the development of information systems: databases; libraries; bibliographic searching; the Internet

- evaluating intervention research (experimental and quasi-experimental research; randomised controlled trials; action research; descriptive and inferential statistics including both parametric and non-parametric approaches)

- evaluating survey research

- evaluating qualitative research (open interviews, discourse and content analysis, observational research)

- evaluation criteria: reliability, validity; issues of corroboration; triangulation

- the main research methodologies and strategies

- Health Service evaluation

- ethical issues in research

- innovations in research and the development of new methodologies.

There is also a 15 credit (UZWSRV-15-M) or 20 credit (UZWYGP-20-M) online learning module option available.

Careers / Further study

This course can contribute towards the following Programmes subject to relevant credit to be undertaken:

- MSc Specialist Practice (District Nursing)

- MSc Advanced Practice

- Professional Development Awards

The module syllabus typically includes:

Knowledge and understanding

- Critically analyse the rationale for particular qualitative and quantitative research methodologies and methods.

- Interpret the stages of the research process and the meaning and significance of data generation and analysis in qualitative and quantitative research.

- Apply the critical knowledge of the relationships between sampling and theory generation.

- Demonstrate a critical awareness of the need for and the process of research governance.

Intellectual skills

- Make evaluative judgements on the relevance of qualitative and quantitative approaches to the investigation of research issues/questions.

- Justify the appropriate uses of primary and secondary sources of data.

Subject/professional/practical skills

- Critically appraise published research relating to their discipline area and its implications for policy and practice.

- Critically appraise a selection of appropriate tools for data collections and analysis.

- Demonstrate an ability to deal effectively with the ethical issues arising in the conduct of research.

Transferable skills

- Demonstrate a reflective approach to research.

- Demonstrate a critical insight into ethical issues, intellectual property rights and other legal considerations arising in the conduct of research.

Learning and Teaching

A variety of learning approaches will be used in conjunction with weekly face-to-face seminars and self-directed study.

You will require easy access to a computer and the internet for the duration of the module.

- For the 15 credit level 7 (Masters level) module: a 3,000 word assignment.

- For the 20 credit level 7 (Masters level) module: a 4,000 word assignment.

Study facilities

The College of Health, Science and Society has an excellent reputation for the quality of its teaching and the facilities it provides.

Get a feel for the Health Professions facilities we have on offer here from wherever you are.

Prices and dates

There is currently no published fee data for this course.

Supplementary fee information

Please visit full fee information to see the price brackets for our modules.

Please click on the 'Apply Now' button to view dates.

How to apply

Please click on the Apply Now button on this page to apply online for this course, which you can take as a stand-alone course or as part of a postgraduate (Masters level) programme.

Extra information

If the course you are applying for is fully online or blended learning, please note that you are expected to provide your own headsets/microphones.

For further information

- Email: [email protected]

You can also follow us on Twitter @UWEhasCPD .

- Open access

- Published: 27 April 2024

Exploring health care providers’ engagement in prevention and management of multidrug resistant Tuberculosis and its factors in Hadiya Zone health care facilities: qualitative study

- Bereket Aberham Lajore 1 na1 nAff5 ,

- Yitagesu Habtu Aweke 2 na1 nAff6 ,

- Samuel Yohannes Ayanto 3 na1 nAff7 &

- Menen Ayele 4 nAff5

BMC Health Services Research volume 24 , Article number: 542 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

Engagement of healthcare providers is one of the World Health Organization strategies devised for prevention and provision of patient centered care for multidrug resistant tuberculosis. The need for current research question rose because of the gaps in evidence on health professional’s engagement and its factors in multidrug resistant tuberculosis service delivery as per the protocol in the prevention and management of multidrug resistant tuberculosis.

The purpose of this study was to explore the level of health care providers’ engagement in multidrug resistant tuberculosis prevention and management and influencing factors in Hadiya Zone health facilities, Southern Ethiopia.

Descriptive phenomenological qualitative study design was employed between 02 May and 09 May, 2019. We conducted a key informant interview and focus group discussions using purposely selected healthcare experts working as directly observed treatment short course providers in multidrug resistant tuberculosis treatment initiation centers, program managers, and focal persons. Verbatim transcripts were translated to English and exported to open code 4.02 for line-by-line coding and categorization of meanings into same emergent themes. Thematic analysis was conducted based on predefined themes for multidrug resistant tuberculosis prevention and management and core findings under each theme were supported by domain summaries in our final interpretation of the results. To maintain the rigors, Lincoln and Guba’s parallel quality criteria of trustworthiness was used particularly, credibility, dependability, transferability, confirmability and reflexivity.

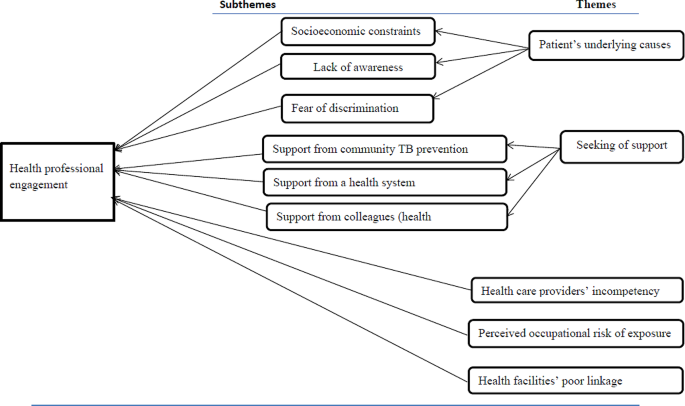

Total of 26 service providers, program managers, and focal persons were participated through four focus group discussion and five key informant interviews. The study explored factors for engagement of health care providers in the prevention and management of multidrug resistant tuberculosis in five emergent themes such as patients’ causes, perceived susceptibility, seeking support, professional incompetence and poor linkage of the health care facilities. Our findings also suggest that service providers require additional training, particularly in programmatic management of drug-resistant tuberculosis.