- Fact sheets

Facts in pictures

- Publications

- Questions and answers

- Tools and toolkits

- Endometriosis

- Excessive heat

- Mental disorders

- Polycystic ovary syndrome

- All countries

- Eastern Mediterranean

- South-East Asia

- Western Pacific

- Data by country

- Country presence

- Country strengthening

- Country cooperation strategies

- News releases

- Feature stories

- Press conferences

- Commentaries

- Photo library

- Afghanistan

- Cholera

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Greater Horn of Africa

- Israel and occupied Palestinian territory

- Disease Outbreak News

- Situation reports

- Weekly Epidemiological Record

- Surveillance

- Health emergency appeal

- International Health Regulations

- Independent Oversight and Advisory Committee

- Classifications

- Data collections

- Global Health Observatory

- Global Health Estimates

- Mortality Database

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Health Inequality Monitor

- Global Progress

- World Health Statistics

- Partnerships

- Committees and advisory groups

- Collaborating centres

- Technical teams

- Organizational structure

- Initiatives

- General Programme of Work

- WHO Academy

- Investment in WHO

- WHO Foundation

- External audit

- Financial statements

- Internal audit and investigations

- Programme Budget

- Results reports

- Governing bodies

- World Health Assembly

- Executive Board

- Member States Portal

- Fact sheets /

HIV and AIDS

- HIV remains a major global public health issue, having claimed an estimated 42.3 million lives to date. Transmission is ongoing in all countries globally.

- There were an estimated 39.9 million people living with HIV at the end of 2023, 65% of whom are in the WHO African Region.

- In 2023, an estimated 630 000 people died from HIV-related causes and an estimated 1.3 million people acquired HIV.

- There is no cure for HIV infection. However, with access to effective HIV prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care, including for opportunistic infections, HIV infection has become a manageable chronic health condition, enabling people living with HIV to lead long and healthy lives.

- WHO, the Global Fund and UNAIDS all have global HIV strategies that are aligned with the SDG target 3.3 of ending the HIV epidemic by 2030.

- By 2025, 95% of all people living with HIV should have a diagnosis, 95% of whom should be taking lifesaving antiretroviral treatment, and 95% of people living with HIV on treatment should achieve a suppressed viral load for the benefit of the person’s health and for reducing onward HIV transmission. In 2023, these percentages were 86%, 89%, and 93% respectively.

- In 2023, of all people living with HIV, 86% knew their status, 77% were receiving antiretroviral therapy and 72% had suppressed viral loads.

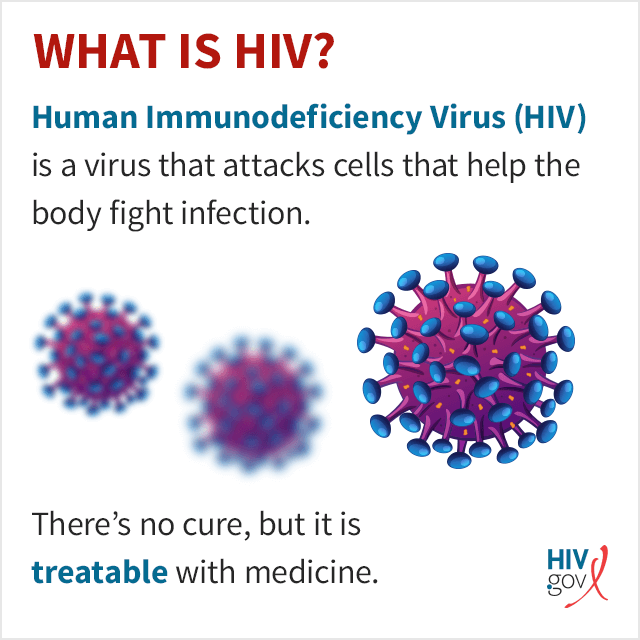

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a virus that attacks the body’s immune system. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) occurs at the most advanced stage of infection.

HIV targets the body’s white blood cells, weakening the immune system. This makes it easier to get sick with diseases like tuberculosis, infections and some cancers.

HIV is spread from the body fluids of an infected person, including blood, breast milk, semen and vaginal fluids. It is not spread by kisses, hugs or sharing food. It can also spread from a mother to her baby.

HIV can be prevented and treated with antiretroviral therapy (ART). Untreated HIV can progress to AIDS, often after many years.

WHO now defines Advanced HIV Disease (AHD) as CD4 cell count less than 200 cells/mm3 or WHO stage 3 or 4 in adults and adolescents. All children younger than 5 years of age living with HIV are considered to have advanced HIV disease.

Signs and symptoms

The symptoms of HIV vary depending on the stage of infection.

HIV spreads more easily in the first few months after a person is infected, but many are unaware of their status until the later stages. In the first few weeks after being infected people may not experience symptoms. Others may have an influenza-like illness including:

- sore throat.

The infection progressively weakens the immune system. This can cause other signs and symptoms:

- swollen lymph nodes

- weight loss

Without treatment, people living with HIV infection can also develop severe illnesses:

- tuberculosis (TB)

- cryptococcal meningitis

- severe bacterial infections

- cancers such as lymphomas and Kaposi's sarcoma.

HIV causes other infections to get worse, such as hepatitis C, hepatitis B and mpox.

Transmission

HIV can be transmitted via the exchange of body fluids from people living with HIV, including blood, breast milk, semen, and vaginal secretions. HIV can also be transmitted to a child during pregnancy and delivery. People cannot become infected with HIV through ordinary day-to-day contact such as kissing, hugging, shaking hands, or sharing personal objects, food or water.

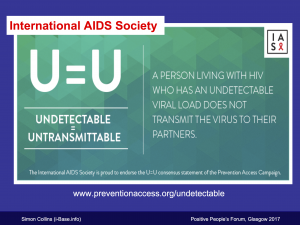

People living with HIV who are taking ART and have an undetectable viral load will not transmit HIV to their sexual partners. Early access to ART and support to remain on treatment is therefore critical not only to improve the health of people living with HIV but also to prevent HIV transmission.

Risk factors

Behaviours and conditions that put people at greater risk of contracting HIV include:

- having anal or vaginal sex without a condom;

- having another sexually transmitted infection (STI) such as syphilis, herpes, chlamydia, gonorrhoea and bacterial vaginosis;

- harmful use of alcohol or drugs in the context of sexual behaviour;

- sharing contaminated needles, syringes and other injecting equipment, or drug solutions when injecting drugs;

- receiving unsafe injections, blood transfusions, or tissue transplantation; and

- medical procedures that involve unsterile cutting or piercing; or accidental needle stick injuries, including among health workers.

HIV can be diagnosed through rapid diagnostic tests that provide same-day results. This greatly facilitates early diagnosis and linkage with treatment and prevention. People can also use HIV self-tests to test themselves. However, no single test can provide a full HIV positive diagnosis; confirmatory testing is required, conducted by a qualified and trained health worker or community worker. HIV infection can be detected with great accuracy using WHO prequalified tests within a nationally approved testing strategy and algorithm.

Most widely used HIV diagnostic tests detect antibodies produced by a person as part of their immune response to fight HIV. In most cases, people develop antibodies to HIV within 28 days of infection. During this time, people are in the so-called “window period” when they have low levels of antibodies which cannot be detected by many rapid tests, but they may still transmit HIV to others. People who have had a recent high-risk exposure and test negative can have a further test after 28 days.

Following a positive diagnosis, people should be retested before they are enrolled in treatment and care to rule out any potential testing or reporting error. While testing for adolescents and adults has been made simple and efficient, this is not the case for babies born to HIV-positive mothers. For children less than 18 months of age, rapid antibody testing is not sufficient to identify HIV infection – virological testing must be provided as early as birth or at 6 weeks of age. New technologies are now available to perform this test at the point of care and enable same-day results, which will accelerate appropriate linkage with treatment and care.

HIV is a preventable disease. Reduce the risk of HIV infection by:

- using a male or female condom during sex

- being tested for HIV and sexually transmitted infections

- having a voluntary medical male circumcision

- using harm reduction services for people who inject and use drugs.

Doctors may suggest medicines and medical devices to help prevent HIV infection, including:

- antiretroviral drugs (ARVs), including oral Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) and long acting products

- dapivirine vaginal rings

- injectable long acting cabotegravir.

ARVs can also be used to prevent mothers from passing HIV to their children.

People taking antiretroviral therapy (ART) and who have no evidence of virus in the blood will not pass HIV to their sexual partners. Access to testing and ART is an important part of preventing HIV.

Antiretroviral drugs given to people without HIV can prevent infection

When given before possible exposures to HIV it is called pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and when given after an exposure it is called post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP). People can use PrEP or PEP when the risk of contracting HIV is high; people should seek advice from a clinician when thinking about using PrEP or PEP.

There is no cure for HIV infection. It is treated with antiretroviral drugs, which stop the virus from replicating in the body.

Current antiretroviral therapy (ART) does not cure HIV infection but allows a person’s immune system to get stronger. This helps them to fight other infections.

Currently, ART must be taken every day for the rest of a person’s life.

ART lowers the amount of the virus in a person’s body. This stops symptoms and allows people to live full and healthy lives. People living with HIV who are taking ART and who have no evidence of virus in the blood will not spread the virus to their sexual partners.

Pregnant women with HIV should have access to, and take, ART as soon as possible. This protects the health of the mother and will help prevent HIV transmission to the fetus before birth, or through breast milk.

Advanced HIV disease remains a persistent problem in the HIV response. WHO is supporting countries to implement the advanced HIV disease package of care to reduce illness and death. Newer HIV medicines and short course treatments for opportunistic infections like cryptococcal meningitis are being developed that may change the way people take ART and prevention medicines, including access to injectable formulations, in the future.

More information on HIV treatments

WHO response

Global health sector strategies on HIV, viral hepatitis, and sexually transmitted infections for the period 2022–2030 ( GHSSs ) guide strategic responses to achieve the goals of ending AIDS, viral hepatitis B and C, and sexually transmitted infections by 2030.

WHO’s Global HIV, Hepatitis and STIs Programmes recommend shared and disease-specific country actions supported by WHO and partners. They consider the epidemiological, technological, and contextual shifts of previous years, foster learning, and create opportunities to leverage innovation and new knowledge.

WHO’s programmes call to reach the people most affected and most at risk for each disease, and to address inequities. Under a framework of universal health coverage and primary health care, WHO’s programmes contribute to achieving the goals of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

- Global HIV, Hepatitis and STIs Programmes

- Global Health Sector Strategies on, respectively, HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections for the period 2022–2030 (GHSS)

- GHSS report on progress and gaps 2024

- HIV country profiles

- HIV statistics, globally and by WHO region, 2024

What Are HIV and AIDS?

- How Is HIV Transmitted?

- Who Is at Risk for HIV?

- Symptoms of HIV

- U.S. Statistics

- Impact on Racial and Ethnic Minorities

- Global Statistics

- HIV and AIDS Timeline

- In Memoriam

- Supporting Someone Living with HIV

- Standing Up to Stigma

- Getting Involved

- HIV Treatment as Prevention

- Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP)

- Post-exposure Prophylaxis (PEP)

- Preventing Sexual Transmission of HIV

- Alcohol and HIV Risk

- Substance Use and HIV Risk

- Preventing Perinatal Transmission of HIV

- HIV Vaccines

- Long-acting HIV Prevention Tools

- Microbicides

- Who Should Get Tested?

- HIV Testing Locations

- HIV Testing Overview

- Understanding Your HIV Test Results

- Living with HIV

- Talking About Your HIV Status

- Locate an HIV Care Provider

- Types of Providers

- Take Charge of Your Care

- What to Expect at Your First HIV Care Visit

- Making Care Work for You

- Seeing Your Health Care Provider

- HIV Lab Tests and Results

- Returning to Care

- HIV Treatment Overview

- Viral Suppression and Undetectable Viral Load

- Taking Your HIV Medicine as Prescribed

- Tips on Taking Your HIV Medicine as Prescribed

- Paying for HIV Care and Treatment

- Other Health Issues of Special Concern for People Living with HIV

- Alcohol and Drug Use

- Coronavirus (COVID-19) and People with HIV

- Hepatitis B & C

- Vaccines and People with HIV

- Flu and People with HIV

- Mental Health

- Mpox and People with HIV

- Opportunistic Infections

- Sexually Transmitted Infections

- Syphilis and People with HIV

- HIV and Women's Health Issues

- Aging with HIV

- Emergencies and Disasters and HIV

- Employment and Health

- Exercise and Physical Activity

- Nutrition and People with HIV

- Housing and Health

- Traveling Outside the U.S.

- Civil Rights

- Workplace Rights

- Limits on Confidentiality

- National HIV/AIDS Strategy (2022-2025)

- Implementing the National HIV/AIDS Strategy

- Prior National HIV/AIDS Strategies (2010-2021)

- Key Strategies

- Priority Jurisdictions

- HHS Agencies Involved

- Learn More About EHE

- Ready, Set, PrEP

- Ready, Set, PrEP Pharmacies

- AHEAD: America’s HIV Epidemic Analysis Dashboard

- HIV Prevention Activities

- HIV Testing Activities

- HIV Care and Treatment Activities

- HIV Research Activities

- Activities Combating HIV Stigma and Discrimination

- The Affordable Care Act and HIV/AIDS

- HIV Care Continuum

- Syringe Services Programs

- Finding Federal Funding for HIV Programs

- Fund Activities

- The Fund in Action

- About PACHA

- Members & Staff

- Subcommittees

- Prior PACHA Meetings and Recommendations

- I Am a Work of Art Campaign

- Awareness Campaigns

- Global HIV/AIDS Overview

- U.S. Government Global HIV/AIDS Activities

- U.S. Government Global-Domestic Bidirectional HIV Work

- Global HIV/AIDS Organizations

- National Black HIV/AIDS Awareness Day February 7

- HIV Is Not A Crime Awareness Day February 28

- National Women and Girls HIV/AIDS Awareness Day March 10

- National Native HIV/AIDS Awareness Day March 20

- National Youth HIV & AIDS Awareness Day April 10

- HIV Vaccine Awareness Day May 18

- National Asian & Pacific Islander HIV/AIDS Awareness Day May 19

- HIV Long-Term Survivors Awareness Day June 5

- National HIV Testing Day June 27

- Zero HIV Stigma July 21

- Southern HIV/AIDS Awareness Day August 20

- National Faith HIV/AIDS Awareness Day August 25

- National African Immigrants and Refugee HIV/AIDS and Hepatitis Awareness Day September 9

- National HIV/AIDS and Aging Awareness Day September 18

- National Gay Men's HIV/AIDS Awareness Day September 27

- National Latinx AIDS Awareness Day October 15

- World AIDS Day December 1

- Event Planning Guide

- U.S. Conference on HIV/AIDS (USCHA)

- National Ryan White Conference on HIV Care & Treatment

- AIDS 2020 (23rd International AIDS Conference Virtual)

Want to stay abreast of changes in prevention, care, treatment or research or other public health arenas that affect our collective response to the HIV epidemic? Or are you new to this field?

HIV.gov curates learning opportunities for you, and the people you serve and collaborate with.

Stay up to date with the webinars, Twitter chats, conferences and more in this section.

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share on Email

What Is HIV?

HIV ( human immunodeficiency virus ) is a virus that attacks cells that help the body fight infection, making a person more vulnerable to other infections and diseases. It is spread by contact with certain bodily fluids of a person with HIV, most commonly during unprotected sex (sex without a condom or HIV medicine to prevent or treat HIV), or through sharing injection drug equipment.

If left untreated, HIV can lead to the disease AIDS ( acquired immunodeficiency syndrome ).

The human body can’t get rid of HIV and no effective HIV cure exists. So, once you have HIV, you have it for life. Luckily, however, effective treatment with HIV medicine (called antiretroviral therapy or ART) is available. If taken as prescribed, HIV medicine can reduce the amount of HIV in the blood (also called the viral load) to a very low level. This is called viral suppression. If a person’s viral load is so low that a standard lab can’t detect it, this is called having an undetectable viral load. People with HIV who take HIV medicine as prescribed and get and keep an undetectable viral load can live long and healthy lives and will not transmit HIV to their HIV-negative partners through sex .

In addition, there are effective methods to prevent getting HIV through sex or drug use, including pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) , medicine people at risk for HIV take to prevent getting HIV from sex or injection drug use, and post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) , HIV medicine taken within 72 hours after a possible exposure to prevent the virus from taking hold. Learn about other ways to prevent getting or transmitting HIV .

What Is AIDS?

AIDS is the late stage of HIV infection that occurs when the body’s immune system is badly damaged because of the virus.

In the U.S., most people with HIV do not develop AIDS because taking HIV medicine as prescribed stops the progression of the disease.

A person with HIV is considered to have progressed to AIDS when:

- the number of their CD4 cells falls below 200 cells per cubic millimeter of blood (200 cells/mm3). (In someone with a healthy immune system, CD4 counts are between 500 and 1,600 cells/mm3.) OR

- they develop one or more opportunistic infections regardless of their CD4 count.

Without HIV medicine, people with AIDS typically survive about 3 years. Once someone has a dangerous opportunistic illness, life expectancy without treatment falls to about 1 year. HIV medicine can still help people at this stage of HIV infection, and it can even be lifesaving. But people who start HIV medicine soon after they get HIV experience more benefits—that’s why HIV testing is so important.

How Do I Know If I Have HIV?

The only way to know for sure if you have HIV is to get tested . Testing is relatively simple. You can ask your health care provider for an HIV test. Many medical clinics, substance abuse programs, community health centers, and hospitals offer them too. If you test positive, you can be connected to HIV care to start treatment as soon as possible. If you test negative, you have the information you need to take steps to prevent getting HIV in the future.

To find an HIV testing location near you, use the HIV Services Locator .

HIV self-testing is also an option. Self-testing allows people to take an HIV test and find out their result in their own home or other private location. With an HIV self-test, you can get your test results within 20 minutes. You can buy an HIV self-test kit at a pharmacy or online. Some health departments or community-based organizations also provide HIV self-test kits for a reduced cost or for free. You can call your local health department or use the HIV Testing and Care Services Locator to find organizations that offer HIV self-test kits near you. (Contact the organization for eligibility requirements.)

Note: State laws regarding self-testing vary and may limit availability. Check with a health care provider or health department Exit Disclaimer for additional testing options.

Learn more about HIV self-testing and which test might be right for you .

Related HIV.gov Blogs

On national hiv testing day, level up your self-love by checking your status, june 27 is national hiv testing day, leaders’ reflections: the ongoing importance of national hiv testing day.

- HIV Testing Day National HIV Testing Day

- World AIDS Day

- HIVinfo.NIH.gov – HIV and AIDS: The Basics

- CDC – HIV Basics

- NIH – HIV/AIDS

- OWH – HIV and AIDS Basics

- VA – HIV/AIDS Basics

- Español (Spanish)

Access presentations from different HIV-related organizations.

| Webpage (HTML) | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention | |

| Webpage (HTML) | UNAIDS | |

| Webpage (HTML) | AIDS Education and Training Center Program National Coordinating Resource Center | |

| Webpage (HTML) | Health Resources and Services Administration Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program | |

| Webpage (HTML) | Florida Health |

Got any suggestions?

We want to hear from you! Send us a message and help improve Slidesgo

Top searches

Trending searches

fall pumpkin

56 templates

fall background

24 templates

rosh hashanah

19 templates

cute halloween

17 templates

122 templates

indigenous canada

48 templates

HIV Disease

It seems that you like this template, hiv disease presentation, free google slides theme, powerpoint template, and canva presentation template.

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) affects more than 35 million people in the world. Since the first cases were known in the 1980s, great advances have been made, which continue to develop today. If you need to create a presentation about HIV, download this template with a light background and bright colours with which you can provide all the information about this disease: description, how it is diagnosed, recommendations and prevention measures, what is its treatment and conclusions about new findings.

Features of this template

- 100% editable and easy to modify

- 26 different slides to impress your audience

- Contains easy-to-edit graphics such as graphs, maps, tables, timelines and mockups

- Includes 500+ icons and Flaticon’s extension for customizing your slides

- Designed to be used in Google Slides, Canva, and Microsoft PowerPoint

- 16:9 widescreen format suitable for all types of screens

- Includes information about fonts, colors, and credits of the free resources used

How can I use the template?

Am I free to use the templates?

How to attribute?

Combines with:

This template can be combined with this other one to create the perfect presentation:

Attribution required If you are a free user, you must attribute Slidesgo by keeping the slide where the credits appear. How to attribute?

Register for free and start downloading now

Related posts on our blog.

How to Add, Duplicate, Move, Delete or Hide Slides in Google Slides

How to Change Layouts in PowerPoint

How to Change the Slide Size in Google Slides

Related presentations.

Premium template

Unlock this template and gain unlimited access

- Patient Care & Health Information

- Diseases & Conditions

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), is an ongoing, also called chronic, condition. It's caused by the human immunodeficiency virus, also called HIV. HIV damages the immune system so that the body is less able to fight infection and disease. If HIV isn't treated, it can take years before it weakens the immune system enough to become AIDS . Thanks to treatment, most people in the U.S. don't get AIDS .

HIV is spread through contact with genitals, such as during sex without a condom. This type of infection is called a sexually transmitted infection, also called an STI. HIV also is spread through contact with blood, such as when people share needles or syringes. It is also possible for a person with untreated HIV to spread the virus to a child during pregnancy, childbirth or breastfeeding.

There's no cure for HIV / AIDS . But medicines can control the infection and keep the disease from getting worse. Antiviral treatments for HIV have reduced AIDS deaths around the world. There's an ongoing effort to make ways to prevent and treat HIV / AIDS more available in resource-poor countries.

Products & Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book

- Assortment of Pill Aids from Mayo Clinic Store

The symptoms of HIV and AIDS vary depending on the person and the phase of infection.

Primary infection, also called acute HIV

Some people infected by HIV get a flu-like illness within 2 to 4 weeks after the virus enters the body. This stage may last a few days to several weeks. Some people have no symptoms during this stage.

Possible symptoms include:

- Muscle aches and joint pain.

- Sore throat and painful mouth sores.

- Swollen lymph glands, also called nodes, mainly on the neck.

- Weight loss.

- Night sweats.

These symptoms can be so mild that you might not notice them. However, the amount of virus in your bloodstream, called viral load, is high at this time. As a result, the infection spreads to others more easily during primary infection than during the next stage.

Clinical latent infection, also called chronic HIV

In this stage of infection, HIV is still in the body and cells of the immune system, called white blood cells. But during this time, many people don't have symptoms or the infections that HIV can cause.

This stage can last for many years for people who aren't getting antiretroviral therapy, also called ART. Some people get more-severe disease much sooner.

Symptomatic HIV infection

As the virus continues to multiply and destroy immune cells, you may get mild infections or long-term symptoms such as:

- Swollen lymph glands, which are often one of the first symptoms of HIV infection.

- Oral yeast infection, also called thrush.

- Shingles, also called herpes zoster.

Progression to AIDS

Better antiviral treatments have greatly decreased deaths from AIDS worldwide. Thanks to these lifesaving treatments, most people with HIV in the U.S. today don't get AIDS . Untreated, HIV most often turns into AIDS in about 8 to 10 years.

Having AIDS means your immune system is very damaged. People with AIDS are more likely to develop diseases they wouldn't get if they had healthy immune systems. These are called opportunistic infections or opportunistic cancers. Some people get opportunistic infections during the acute stage of the disease.

The symptoms of some of these infections may include:

- Fever that keeps coming back.

- Ongoing diarrhea.

- Swollen lymph glands.

- Constant white spots or lesions on the tongue or in the mouth.

- Constant fatigue.

- Rapid weight loss.

- Skin rashes or bumps.

When to see a doctor

If you think you may have been infected with HIV or are at risk of contracting the virus, see a healthcare professional as soon as you can.

More Information

- Early HIV symptoms: What are they?

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

HIV is caused by a virus. It can spread through sexual contact, shooting of illicit drugs or use of shared needles, and contact with infected blood. It also can spread from parent to child during pregnancy, childbirth or breastfeeding.

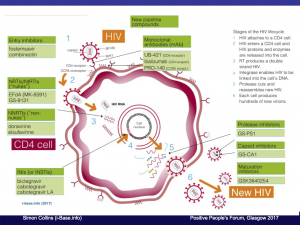

HIV destroys white blood cells called CD4 T cells. These cells play a large role in helping the body fight disease. The fewer CD4 T cells you have, the weaker your immune system becomes.

How does HIV become AIDS?

You can have an HIV infection with few or no symptoms for years before it turns into AIDS . AIDS is diagnosed when the CD4 T cell count falls below 200 or you have a complication you get only if you have AIDS , such as a serious infection or cancer.

How HIV spreads

You can get infected with HIV if infected blood, semen or fluids from a vagina enter your body. This can happen when you:

- Have sex. You may become infected if you have vaginal or anal sex with an infected partner. Oral sex carries less risk. The virus can enter your body through mouth sores or small tears that can happen in the rectum or vagina during sex.

- Share needles to inject illicit drugs. Sharing needles and syringes that have been infected puts you at high risk of HIV and other infectious diseases, such as hepatitis.

- Have a blood transfusion. Sometimes the virus may be transmitted through blood from a donor. Hospitals and blood banks screen the blood supply for HIV . So this risk is small in places where these precautions are taken. The risk may be higher in resource-poor countries that are not able to screen all donated blood.

- Have a pregnancy, give birth or breastfeed. Pregnant people who have HIV can pass the virus to their babies. People who are HIV positive and get treatment for the infection during pregnancy can greatly lower the risk to their babies.

How HIV doesn't spread

You can't become infected with HIV through casual contact. That means you can't catch HIV or get AIDS by hugging, kissing, dancing or shaking hands with someone who has the infection.

HIV isn't spread through air, water or insect bites. You can't get HIV by donating blood.

Risk factors

Anyone of any age, race, sex or sexual orientation can have HIV / AIDS . However, you're at greatest risk of HIV / AIDS if you:

- Have unprotected sex. Use a new latex or polyurethane condom every time you have sex. Anal sex is riskier than is vaginal sex. Your risk of HIV increases if you have more than one sexual partner.

- Have an STI . Many STIs cause open sores on the genitals. These sores allow HIV to enter the body.

- Inject illicit drugs. If you share needles and syringes, you can be exposed to infected blood.

Complications

HIV infection weakens your immune system. The infection makes you much more likely to get many infections and certain types of cancers.

Infections common to HIV/AIDS

- Pneumocystis pneumonia, also called PCP. This fungal infection can cause severe illness. It doesn't happen as often in the U.S. because of treatments for HIV / AIDS . But PCP is still the most common cause of pneumonia in people infected with HIV .

- Candidiasis, also called thrush. Candidiasis is a common HIV -related infection. It causes a thick, white coating on the mouth, tongue, esophagus or vagina.

- Tuberculosis, also called TB. TB is a common opportunistic infection linked to HIV . Worldwide, TB is a leading cause of death among people with AIDS . It's less common in the U.S. thanks to the wide use of HIV medicines.

- Cytomegalovirus. This common herpes virus is passed in body fluids such as saliva, blood, urine, semen and breast milk. A healthy immune system makes the virus inactive, but it stays in the body. If the immune system weakens, the virus becomes active, causing damage to the eyes, digestive system, lungs or other organs.

- Cryptococcal meningitis. Meningitis is swelling and irritation, called inflammation, of the membranes and fluid around the brain and spinal cord, called meninges. Cryptococcal meningitis is a common central nervous system infection linked to HIV . A fungus found in soil causes it.

Toxoplasmosis. This infection is caused by Toxoplasma gondii, a parasite spread primarily by cats. Infected cats pass the parasites in their stools. The parasites then can spread to other animals and humans.

Toxoplasmosis can cause heart disease. Seizures happen when it spreads to the brain. And it can be fatal.

Cancers common to HIV/AIDS

- Lymphoma. This cancer starts in the white blood cells. The most common early sign is painless swelling of the lymph nodes most often in the neck, armpit or groin.

- Kaposi sarcoma. This is a tumor of the blood vessel walls. Kaposi sarcoma most often appears as pink, red or purple sores called lesions on the skin and in the mouth in people with white skin. In people with Black or brown skin, the lesions may look dark brown or black. Kaposi sarcoma also can affect the internal organs, including the lungs and organs in the digestive system.

- Human papillomavirus (HPV)-related cancers. These are cancers caused by HPV infection. They include anal, oral and cervical cancers.

Other complications

- Wasting syndrome. Untreated HIV / AIDS can cause a great deal of weight loss. Diarrhea, weakness and fever often happen with the weight loss.

- Brain and nervous system, called neurological, complications. HIV can cause neurological symptoms such as confusion, forgetfulness, depression, anxiety and difficulty walking. HIV -associated neurological conditions can range from mild symptoms of behavior changes and reduced mental functioning to severe dementia causing weakness and not being able to function.

- Kidney disease. HIV -associated nephropathy (HIVAN) is swelling and irritation, called inflammation, of the tiny filters in the kidneys. These filters remove excess fluid and waste from the blood and pass them to the urine. Kidney disease most often affects Black and Hispanic people.

- Liver disease. Liver disease also is a major complication, mainly in people who also have hepatitis B or hepatitis C.

There's no vaccine to prevent HIV infection and no cure for HIV / AIDS . But you can protect yourself and others from infection.

To help prevent the spread of HIV :

Consider preexposure prophylaxis, also called PrEP. There are two PrEP medicines taken by mouth, also called oral, and one PrEP medicine given in the form of a shot, called injectable. The oral medicines are emtricitabine-tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (Truvada) and emtricitabine-tenofovir alafenamide fumarate (Descovy). The injectable medicine is called cabotegravir (Apretude). PrEP can reduce the risk of sexually transmitted HIV infection in people at very high risk.

PrEP can reduce the risk of getting HIV from sex by about 99% and from injecting drugs by at least 74%, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Descovy hasn't been studied in people who have sex by having a penis put into their vaginas, called receptive vaginal sex.

Cabotegravir (Apretude) is the first U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved PrEP that can be given as a shot to reduce the risk of sexually transmitted HIV infection in people at very high risk. A healthcare professional gives the shot. After two once-monthly shots, Apretude is given every two months. The shot is an option in place of a daily PrEP pill.

Your healthcare professional prescribes these medicines to prevent HIV only to people who don't already have HIV infection. You need an HIV test before you start taking any PrEP . You need to take the test every three months for the pills or before each shot for as long as you take PrEP .

You need to take the pills every day or closely follow the shot schedule. You still need to practice safe sex to protect against other STIs . If you have hepatitis B, you should see an infectious disease or liver specialist before beginning PrEP therapy.

Use treatment as prevention, also called TasP. If you have HIV , taking HIV medicines can keep your partner from getting infected with the virus. If your blood tests show no virus, that means your viral load can't be detected. Then you won't transmit the virus to anyone else through sex.

If you use TasP , you must take your medicines exactly as prescribed and get regular checkups.

- Use post-exposure prophylaxis, also called PEP, if you've been exposed to HIV . If you think you've been exposed through sex, through needles or in the workplace, contact your healthcare professional or go to an emergency room. Taking PEP as soon as you can within the first 72 hours can greatly reduce your risk of getting HIV . You need to take the medicine for 28 days.

Use a new condom every time you have anal or vaginal sex. Both male and female condoms are available. If you use a lubricant, make sure it's water based. Oil-based lubricants can weaken condoms and cause them to break.

During oral sex, use a cut-open condom or a piece of medical-grade latex called a dental dam without a lubricant.

- Tell your sexual partners you have HIV . It's important to tell all your current and past sexual partners that you're HIV positive. They need to be tested.

- Use clean needles. If you use needles to inject illicit drugs, make sure the needles are sterile. Don't share them. Use needle-exchange programs in your community. Seek help for your drug use.

- If you're pregnant, get medical care right away. You can pass HIV to your baby. But if you get treatment during pregnancy, you can lessen your baby's risk greatly.

- Consider male circumcision. Studies show that removing the foreskin from the penis, called circumcision, can help reduce the risk of getting HIV infection.

- About HIV and AIDS . HIV.gov. https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/overview/about-hiv-and-aids/what-are-hiv-and-aids. Accessed Oct. 18, 2023.

- Sax PE. Acute and early HIV infection: Clinical manifestations and diagnosis. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed Oct. 18, 2023.

- Ferri FF. Human immunodeficiency virus. In: Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2024. Elsevier; 2024. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed Oct. 18, 2023.

- Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in adults and adolescents with HIV . HIV.gov. https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-adult-and-adolescent-opportunistic-infections/immunizations. Accessed Oct. 18, 2023.

- AskMayoExpert. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Mayo Clinic; 2023.

- Elsevier Point of Care. Clinical Overview: HIV infection and AIDS in adults. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed Oct. 18, 2023.

- Male circumcision for HIV prevention fact sheet. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/fact-sheets/hiv/male-circumcision-HIV-prevention-factsheet.html. Accessed Oct. 19, 2023.

- Acetyl-L-carnitine. Natural Medicines. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com. Accessed. Oct. 19, 2023.

- Whey protein. Natural Medicines. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com. Accessed. Oct. 19, 2023.

- Saccharomyces boulardii. Natural Medicines. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com. Accessed Oct. 19, 2023.

- Vitamin A. Natural Medicines. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com. Accessed Oct. 19, 2023.

- Red yeast rice. Natural Medicines. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com. Accessed Oct. 19, 2023.

Associated Procedures

- Liver function tests

News from Mayo Clinic

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Know your status -- the importance of HIV testing June 25, 2024, 04:00 p.m. CDT

- Unlocking the mechanisms of HIV in preclinical research Jan. 10, 2024, 03:30 p.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic expert on future of HIV on World AIDS Day Dec. 01, 2023, 05:15 p.m. CDT

- Symptoms & causes

- Diagnosis & treatment

- Doctors & departments

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

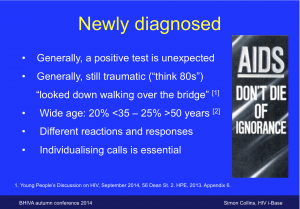

Slide sets from talks and workshops

9 July 2024. Related: Advocates , Resources .

The following selected slide sets from over 60 community workshops and other talks were produced by i-Base advocates.

These are free to use for any non-commercial application.

When third-party slides are used these remain the copyright of the original author.

Most talks are by Simon Collins, unless specified otherwise.

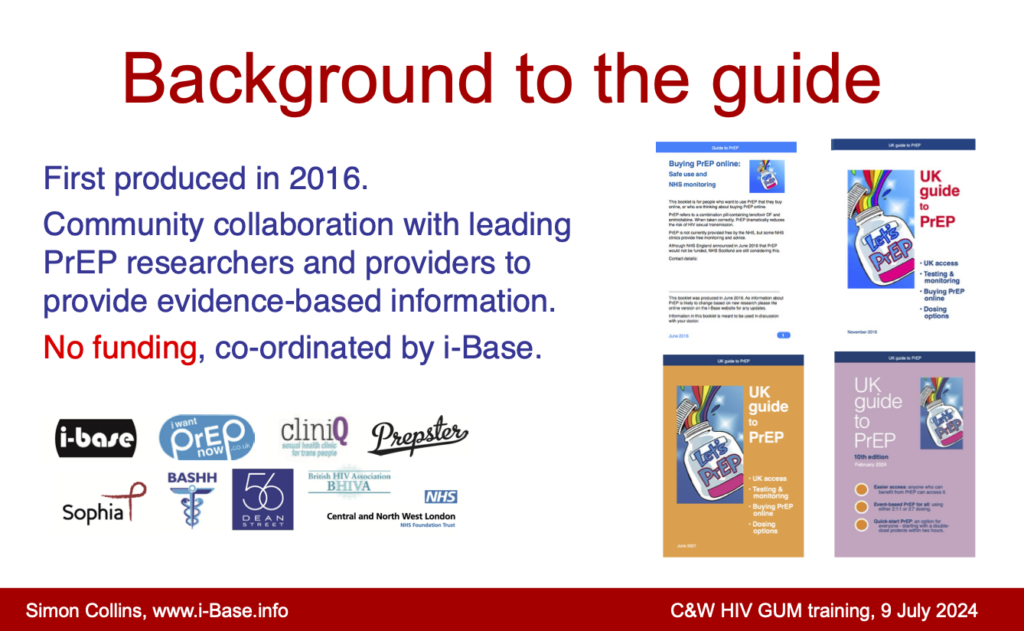

2024 changes in the UK Guide to PrEP: a community perspective

It is a community perspective on the upcoming changes in the upcoming joint BHIVA/BASHH PrEP Guidelines expected later in 2024.]

A technical presentation of the key studies and data supporting these changes was given by Dan Clutterbuck at the BHIVA annual conference this year and also by Sheena McCormack to the HIV GUM training course several week earlier.

The non-techincal talk also explains the background to both the UK Community Guide and the timeline for the UK Guidelines. The slideset includes the data slides relating to oral PrEP from Dan Clutterbuck’s talk at BHIVA.

C&W PrEP – PDF (4.4 MB)

C&W PrEP – PowerPoint file (9.5 MB)

500 sexual partners: Including community in HIV research

The session was about approaches to statistical modelling.

This talk was abiout the importance of including community to make sure the best and most relevant data is available for these models. It includes examples of where community input changed the design of research studies.

It also highlighted examples where the lack of data becomes a block to effective services, for example over transgender health, support services for chemsex and PrEP for trans men.

The title was based on the example of partner numbers asked for in recent survey, where the upper limit was just >10. This ignored an important percentage of people where numbers could easily be much higher. The importance of risk ir perhaps more important than partner number.

BASHH modelling 2024 FINAL (PDF)

Treatment and prevention update 2024

They were run by Simon Collins and Angelina Namiba at the 6th UK Conference for people living with HIV.

The workshops included first-hand experience from someone using injectable ART (CAB/RPV-LA), important new options on for taking PrEP, and the importance of solidarity and support for trans and non-binary people during 2024.

HIV+ UK 2024 FINAL 010624 (15 MB)

4MNet: Women, treatment and our wellbeing

It included co-morbidities that affect us and about living well with HIV.

This was for women living in Kenya, Uganda and the UK.

The talk is also posted to Vimeo online . https://vimeo.com/907478359/ceb50db723

IAS 2023 – UK-CAB Feedback

Community feedback talk from the IAS 2023 conference held in Brisbane, Australia in July 2023.

The slides were based on virtual reporting from the meetings.

Highlights included new cure-related studies, including the Geneva patient. Also lots about HIV complications including the REPRIEVE study that used a statin to reduce cardiovascular risk.

IAS 2023 feedback – PDF talk IAS 2023 feedback – PowerPoint slides

cliniQ conference: PrEP for trans people

These few slides were used as an introduction to aa panel discussion at the 9th CliniQ Conference held on 20 April 2023.

The discussion wanted to cover important issues including the lack of data on trans people in the UK who use PrEP, but also to emphasise that PrEP is just as safe and effective as for cisgender people.

Also that there are no drug interactions between PrEP and gender affirming hormones.

CliniQ PrEP apr 23 – PowerPoint slides CliniQ PrEP apr 23 – PDF slides.

Aidsfonds Stakeholder meeting on cure-related research

This was research workshop held on 10 January 2023 brought together different stakeholders involved in cure-related research.

The couple of slides here highlighted three headline points that were used in some of the group discussions.

AIDSFONDS slides – jan 23 – PowerPoint AIDSFONDS slides – jan 23 – PDF

HIV activism and future HIV drug research

This talk was given as part of the Turkish Civil Society #HIV2022 Conference held from 4 to 6 November 2022 in Istanbul.

Although the main conference was aa face-to-face meeting, this talk was given virtually.

It looks at the role of activism in developing effective HIV drugs and includes information of drugs currently in the pipeline.

Turkey #HIV2022 – PowerPoint Turkey #HIV2022 – PDF

HIV late diagnosis: Article and interview

These links are to an article in a special supplement the medical journal HIV Medicine about late HIV diagnosis from a community perspective.

The authors are all members of the UK-CAB.

The interview is for Medscape about this and other papers from the supplement.

Late diagnosis of HIV in 2022: Why so little change? Collins S, Namiba A, Sparrowhawk A, Strachan S, Thompson M, Nakamura H. HIV Medicine. 2022; 23(11): 1118–1126. doi:10.1111/hiv.13444. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/hiv.13444

Medscape. Late HIV tied to misclassifications in European surveillance efforts (21 December 2022). https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/985966

BMJ podcast on mpox

This links to an interview and discussion about the mpox outbreak.

EATG/STEPS cure workshop

This short talk was given on 23 October 2022 as part of a workshop on cure research organised by the EATG at the Glasgow Congress.

It recommends the IAS review of cure-related research, and talks about community issues in that document. This includes the importance of have greater diversity of participants in these studies – including by sex, gender, race, ethnicity and geographic region.

Includes new data from TAG on sex and ethnicity in cure research and the personal impact of joining a cure study.

Download slides – PDF file

HIV science for the community

This slide set covers two European workshops in September 2022 organised by Africa AIDS Foundation (AAF).

They give an introduction to HIV treatment for health workers who have clients who are living with HIV,

Download PowerPoint slides (5 MB) Download PDF (2 MB)

Research priorities for an HIV cure: the science in context: a community perspective

This talk was given in July 2022 as part of the IAS cure research workshop held in Montreal just before the AIDS 2022 conference.

It included talking about how community advocates are involved in this research, but that this needs to be expanded, Community representation needs to include a wider group of people globally just as cure-related research also needs to be international.

Download PDF file (12 MB) Link to all talks at the workshop .

HIV treatment and innovations in care

Talk given jointly in June 2022 with Angelina Namiba from the 4MM network. This was for a workshop as part of the 5th UK Conference of people living with HIV.

This covered latest HIV drugs and those expected in the near future.

This included long-acting drugs and the potential for different formulations.

It also talked about standards of care in the UK and the issues linked to HIV and ageing.

Download PowerPoint slides PowerPoint slides (5 MB) Download PDF file (1.8 MB)

The RIO study

This is a very short talk given to participants on the UK RIO study.

This study uses two bNAbs to see whether viral load can remain undetectable after infusions of bNAbs and a treatment interruption.

Download PDF (300 KB)

Community involvement in the IAS cure strategy

Talk given in May 2022 as part of an IAS webinar.

This focussed on the IAS strategy for cure research, especially the latest 5-year review on recent and future research.

This included input of community advocates in this process.

Download PowerPoint slides (3.4 MB) Download PDF file (3 MB)

Feedback from CROI 2022

This is a talk to the UK-CAB in April 2022 about the main new from the recent CROI 2022 conference.

This included new drugs like lenacapavir, bNAbs, long-acting injectable ART, cure-related research, the ANCHOR study and more.

Download PDF (6 MB)

Women and ageing

This talk in March 2022 looked at issues that are important for women getting older with HIV.

This includes being actively involved in care and treatment decisions, medical issues that need monitoring and screening, side effects of ART and the importance of good mental health.

Download PDF (3 MB)

Women, treatment and well-being

Talk on 23 March 2022 for workshops organised by the 4MM project.

This is a general overview about being engaged and active in your own treatment decisions.

It was an introduction to HIV including CD4 counts and viral load, adherence and starting and changing HIV meds.

Download PowerPoint slides (5 MB) Download PDF file (1 MB)

Caution on CAB-LA PrEP and population drug resistance

This was a short talk for the AfroCAB about long-acting cabotegravir injections (CAB-LA) and PrEP.

It is essential that CAB-LA becomes rapidly available as an option to protect against HIV all people globally. Modelling studies show that access can safely provided with only a small risk of drug resistance.

This talk highlights some of these areas with a caution that models should include the possibility that larger percentages of people discontinue CAB-LA, as they have done with oral PrEP.

Download PowerPoint slides (2 MB) Download PDF (2 MB)

Healthy Living with HIV: what do COVID vaccines mean for people living with HIV

Talk given to a medical workshop on the 2 October 2021 about what vaccines mean for people living with HIV.

PowerPoint slides

Use of generic HIV medicines in the UK

Slides from a short talk on 1 July 2021 at a regional meeting in on Access, Quality and Pricing of HIV Drugs in SEE Countries (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia).

i-Base was included to give a perspective from the UK, including that generic HIV drugs are not only widely used, but are an essential strategy to retaining free health care on the NHS.

Generics in the UK – (PowerPoint slides) Generics in the UK (PDF)

HIV 40 Years On: perspective of being an active patient

Webinar on 23 June 2021, jointly organised by the Fast Track Cities London and the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries.

This was both to recognise the medical advances for the 40th anniversary of the first publication of HIV cases in the US and to look forward to the goals of “Getting to Zero” by 2030.

Download slides (PDF) Webcast and info on Fast Track Cities website Webcast on You Tube

Community panel webinar on COVID-19

Roundtable discussion organised by Jim Pickett from AIDS Foundation Chicago and IAS-USA with six community advocates on difference aspects of COVID-19. No slides but maybe of interest to hear about different international perspectives.

Watch on YouTube .

Introduction to U=U for Trans and MSM HIV support group in Nepal

These slides were for a virtual workshop on 22 May 2021 about U=U for a Trans and MSM HIV support group in Nepal.

Many of the slides are similar to other U=U presentations, but this started with general questions and discussions.

The science showing U=U is a fact came after everyone had a good understanding of what U=U meant in practice.

U=U peer support Nepal – Slides with notes (PDF 3 MB) U=U peer support Nepal – 22 May 2021 (PDF 8MB)

History of U=U: getting wider awareness

This talk was part of a peer support virtual workshop on 1 May 2021 on U=U.

It was held with 50 community advocates in countries in South East Asia.

Download PDF file . (7 MB)

Treatment interruption in cure research during COVID-19

This talk on 4 March 2021 was part of the always excellent Community Cure Workshops organised by TAG, DARE and other US activist groups before CROI every year.

The talk looked at whether HIV cure research should continue to use analytic treatment interruptions (ATIs) during COVID-19. This is because of concerns that it might increase risks for study participants.

The talk looks at two discussion papers (on mainly from the US and the other mainly from the UK). It includes way to reduces risks (new entry criteria, fewer hospital visits, use of vaccines) and of course the importance of informed consent.

Powerpoint slides (6 MB) – Please contact i-Base PDF file (6 MB) – Please contact i-Base Webcast (with discussion)

Q&A on COVID-19: vaccines and variants

Slides for a zoom talk on 15 February 2021 to Positive Action Foundation Philippines (PAPFI).

This included a short introduction to COVID-19 and potential treatments, but was mainly an update on the safety and efficacy of the new vaccines.

Plus a range of frequent questions over safety of COVID-19 vaccines for HIV positive people.

Powerpoint slides (.PPT 3MB) PDF slides (PDF 3MB)

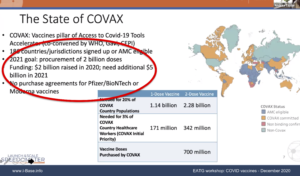

Non-technical review of vaccines for COVID-19

This includes that more than 300 candidate vaccines are in studies, 40 in humans, 10 in phase 3, and two approved or almost approved (Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna/NIH).

It briefly describes the main approaches with summary results on the Pfizer, Moderna and Oxford/Astra-Zeneca vaccines – and the importance of future studies using an active rather than placebo control.

Also, the plans for fair and equitable access globally. And the challenges given that high income countries have already bought or optioned nearly all the first vaccines to be manufactured next year.

Finally, examples of many questions HIV positive people have about the chance of using these vaccines ourselves.

Powerpoint slides .pptx and PDF slides (both about 8 MB)

Link to webcast – STILL TO COME

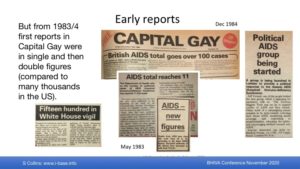

Lest we forget – Early community involvement in UK HIV response

The community talk included examples of the first reports in the community newspaper Capital Gay and the response from Lesbian and Gay pubs and clubs to collect money for HIV projects. It covers the diversity of community organisations to provide support to different communities of people living with HIV.

This included THT, Body Positive, Birchgrove, Positively Women, Blackliners, Mainliners and many more – and many publications that provided important information and also generated a stronger community network.

PowerPoint slides – (9 MB) Webcast link to both talks . The community talk starts at 16.50.

COVID-19 and upcoming HIV drugs

Workshop on 21 October to the long-standing and dynamic community organisation Positive EAST.

This included this 30-minute talk with Greg Leonard who runs many of the support groups at this project in East London and who recently launched a programme of virtual workshops linked to their FaceBook page.

The talk was given as the second wave of COVID-19 had just become establish in London.

Download PDF slides – (3 MB) – PDF file Download Powerpoint slides – (6 MB) – PowerPoint file Watch talk on FaceBook

Introduction to science and HIV research

Workshop as part of EATG STEP course – an introduction to HIV research.

The talk was on 25 September 2020.

It includes research examples that will surprise most people – and therefore show how science can change out mind,

It also includes references to other online resources on treatment literacy.

Download PDF slides . (4.7 MB) Download PowerPoint slides. (4.8 MB)

History of Treatment as Prevention (TasP) and U=U

Workshop as part of EATG STEP course on use of ART as HIV prevention.

The talk highlights key research over the last 22 years that steadily accumulated enough evidence to establish that effective HIV treatment prevents HIV transmission.

Download PDF slides. (5MB) Download PowerPoint slides. (5MB)

Introduction to science (via COVID-19)

This virtual zoom workshop for the EATG general assembly (GA) on 19 September 2020 was about understanding, monitoring, and discussing scientific data for advocacy.

It was a refresher course on different types of research studies using examples from the last nine months of COVID-19 – compressing the equivalent of 40 years of HIV research. This includes data sites (epidemiology), how COVID-19 develops (pathogenesis) and a review of effective treatments and those that should not be used.

In the search for effective treatment, and among thousands of studies, it shows why randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are still needed. Actually, that they are the only way to really know whether or not a promising drug is effective.

Webcast link .

Download PDF of slides . (4.5 MB)

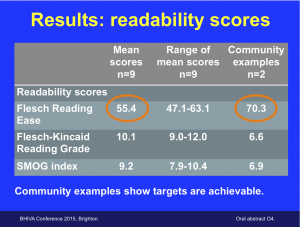

Readability: importance of information that is easy to read for most people

This talk is avoid the importance of good readability scores when producing patient information material – especially in documents for clinical studies.

The talk was given on 3 September 2020 to a working group at Gilead Sciences in the UK and US.

It was based on a talk given at the BHIVA conference in April 2015 (see below).

Download slides (PDF) – 9 MB Readabilty study Gilead Sep 2020 – (PowerPoint – 9.3 MB)

AIDS 2020 feedback (and COVID-19 update no.3)

Feedback to UK-CAB on 28 July 2020 on treatment news from the AIDS 2020 virtual conference and another update on COVID-19.

These studies included positive news on dolutegravir and neural tube defects, longer follow-up on continued weight gain in the ADVANCE study, results using cabotegravir long-acting injections for PrEP and a case reporting HIV remission.

It also included problems navigating the AIDS 2020 website.

The COVID-19 updated summarised important studies reported in the HIV and COVID-19 bulletins from i-Base.

Watch talk on YouTube .

COVID-19 and HIV coinfection: Update 2

A second talk to UK-CAB on 5 June 2020 about advances in research on COVID-19 over the last month.

It also includes statisticians from Public Health England to talk a new report highlighting risk factors for COVID-19, including race, ethnicity and employment.

The main talk includes six new studies on HIV/COVID-19 coinfection, US approval and UK access to remdesivir, reviews of UK research and of promising results with anakinra, anticoagulants, ACE inhibitors, interferon and convalescent plasma. Also controversial results with hydroxychloroquine. Plus updates from BHIVA and EACS statements.

Watch zoom talk on YouTube (via UK-CAB)

UK-CAB COVID19 june 2020 – (PDF – 12MB) UK-CAB COVID-19 june 2020 – (PowerPoint) – please email as large file

COVID-19: summary of current research

Workshop with the European AIDS Treatment Group (EATG) on 15 May 2020.

This was a 30 minute talk about rapidly changing knowledge about COVID-19.

It was also, for EATG members to be able to talk about COVID-19 responses in our different countries and how this has been affecting people living with HIV.

The slides in this talk are similar to the UK-CAB meeting below.

Watch zoom talk on YouTube (via EATG) Powerpoint slides (.PPT 2.6 MB) PDF slides (PDF, 2.2 MB)

COVID-19 and HIV coinfection: key research

Talk to virtual UK-CAB Zoom meeting on 1 May 2020. Mainly links to recent research from recent HTB coverage about HIV and COVID-19.

UK-CAB COVID-19 apr 2020 – (PDF – 2MB) UK-CAB COVID-19 apr 2020 – (PowerPoint – 2.2 MB)

CROI 2020 feedback – virtual meeting

Talk as part of virtual UK-CAB Zoom meeting on 30 April 2020.

The talk mainly focused on studies involving new HIV drugs for treatment or prevention (PrEP).

UK-CAB feedback from CROI 2020 (April 2020) – PDF (17 MB)

Please email for Powerpoint slides as these are too large to post online

Future PrEP: next generation drugs

It reviews a range of new drugs that are being developed both as HIV treatment and PrEP. This might include:

- Long-acting injections (every two months).

- A removable implant that would provide PrEP for over a year, and

- A small oral pill that you might only need to take once a month.

Watch to video on YouTube (15 minute talk) HIV PrEP pipeline feb 2020 – PDF (8MB) HIV PrEP pipeline feb 2020 – PowerPoint (8MB)

U=U: approaches by community and professional organisations in the UK

This talk in January 2020 was given at a U=U conference in Tokyo organised by the Japanese HIV Society.

This talk focused on the ways that BHIVA has shown leadership to publicise U=U. It also includes many examples of how individuals and organisations in the UK have also widened awareness of how HIV treatment prevents sexual transmission.

UK approach to putting U=U in practice This notes file shows slides in colour with written talk below on each page – PDF (5 MB)

The PowerPoint file is too large to post here but we can send an individual weblink to download if anyone would like this. Please email: [email protected] ).

Community cure meeting: bNAbs and the RIO study

Talk from November 2019 included in the programme of the European AIDS Conference (EACS 2019) held in Basel.

The workshop looked at advances and issues related to HIV cure-related research.

It included information about a study called RIO that will be using two long-acting bNAbs with a treatment interruption. The RIO study is due to start in early 2020.

This workshop was organised by the European Community Advisory Board (ECAB) which is part of the European AIDS Treatment Group (EATG).

RIO Study – EATG cure meeting EACS – Powerpoint slides (3 MB)

RIO Study – EATG cure meeting EACS – PDF (2.5 MB)

Community perspectives of new research

Talk from June 2019 as part of HMRG European HIV Seminar held in Dublin.

The talk looked at advances in treatment over three decades and yet new drugs are still approved with limited data in women, during pregnancy and with TB drugs. Also the delay in access for children.

HMRG 2019 – PDF slides (7 MB)

CROI 2019 feedback

Set of approximately 60 slides compiled from key studies presented at the recent CROI 2019 medical conference in Seattle.

This presentation was to the UK-Community Advisory Board (UK-CAB) meeting on 6 April 2019.

CROI 2019 feedback UK-CAB – PDF slides (5.6 MB)

Is rapid ART right for all?

Talk given on the last day of the 25th BHIVA conference held in Bournemouth (BHIVA 2019).

The talk includes reports from two clinics where people are offered ART when they have their first appointment after diagnosis – often on the same day. All other services and tests and services are reorganised to enable this.

Webcast link – (At approx 1hr2mins if doesn’t load automatically)

Rapid ART for all? – PDF slides. (3 MB)

Rapid ART for all? – notes – PDF with notes. (3 MB)

Ethical issues and informed consent in HIV cure research studies: EATG workshop, Glasgow 2018

A talk looking at a common disconnect between researchers and participants in HIV cure-related studies.

More researchers expect no or little clinical benefit. Many participants still think they had a slight or more significant hope that they might be cured.

ECAB cure – Glasgow 2018 – PDF (100 Mb)

20th National HIV Nurses Association (NHIVNA) conference, July, Brighton

Evidence for U=U: the PARTNER study and Prevention Access Campaign

Talk as part of the pre-conference workshop about the evidence over twenty years for the U=U campaign.

This included the London version: A=A: Ain’t no viral load, ain’t no risk of HIV.

NHIVNA U=U talk 27 June 2018 (PDF – (7.2 MB)

NHIVNA U=U talk with NOTES (PDF – 3.4 MB)

4th National Conference of People Living with HIV (October 2017)

Treatment update for London HIV positive conference.

Topics cover evidence for U=U and treatment updates for new drugs.

This talk was largely based on the talks given at the HIV Scotland conference below.

UK HIV+ conference 2017 Treatment update (PDF – 8.5 MB)

Paediatric HIV pipeline drugs (October 2017)

Talk on pipeline HIV drugs for children given by Polly Clayden to a closed meeting of the IMPAACT trial network.

This is a focus on the paediatric pipeline, that usually takes several years (at least) after a drug is approved for adults.

This also usually occurs in age bands – first adolescents, then children and finally infants and babies. Many HIV drugs, however, are never approved for the youngest children.

Paediatric ART pipeline IMPAACT – (PDF – 950 Kb)

Positive Peoples Forum – HIV Scotland (July 2017)

Two talks for the annual HIV positive conference held in Glasgow this year.

Undetectable = untransmittable (U=U) – PDF (3.3 MB)

A talk about HIV treatment as prevention (TasP) that reviews the evidence for why so many doctors, scientist and community groups say that an undetectable viral load means you cannot transmit HIV to partners.

This was included as an idea in US guidelines in 1998 and has been supported by accumulating evidence from different studies over the last 20 years.

Short update about new HIV meds in development, drug pricing in the UK, cure research and PrEP.

This includes the HIV lifecycle to show how current HIV drugs work at different sites and the new targets for the most promising upcoming drugs.

A couple of slides are included on drug pricing in the UK and how generics affect this.

CROI 2017: feedback to UK-CAB (April 2017)

Short talk to feedback key studies for the UK-CAB.

Mainly to cover cure research, new drugs and treatment strategies.

CROI 2017 feedback UK-CAB – PDF (5 MB)

Review of i-Base treatment information services (April 2016)

Talk given by Robin Jakob to BHIVA conference about the phoneline and Q&A services.

http://www.bhiva.org/160420RobinJakob.aspx

Reference: HIV treatment information and advocacy 2014/15: continued demand for community support services . R Jakob, R Trevelion, J Dunworth, M Sachikonye and S Collins. 22nd Annual BHIVA Conference, 19-22 April 2016, Manchester. Oral abstract O5. HIV Medicine, 17 (Suppl. 1), 3–13. HIV Medicine 17, 4, 2016. Treatment advocacy – 2014-15 – Robin Jakob – PDF slides. http://www.bhiva.org/documents/Conferences/2016Manchester/AbstractBook2016.pdf

HIV testing: who, how and why? (September 2015)

Martin was one of the key doctors whose skills, energy and determination over the last 20 years were responsible for ensuring that HIV positive people in the UK received such high standards of care.

He was also a scientist and researcher, activist and friend. Martin was an incredibly kind, passionate, popular and modest man and his partner Adrian together with his family, friends and colleagues have launched this foundation to celebrate and continue his work.

HIV Testing Martin Fisher foundation talk – PowerPoint (2 Mb) HIV testing MFF – PDF (2 Mb)

Watch webcast on Vimeo .

2015 treatment update: good time for a change (September 2015)

- Impact of START study on BHIVA and WHO guidelines.

- Absolute and relative benefits from earlier treatment.

- TasP and PrEP.

- Immune inflammation.

- ART in acute infection and cure research.

UK HIV conference 2015 – PDF (900 Kb) UK PWA conference 2015 – PowerPoint (1.1 Mb)

START study results and new BHIVA guidelines – UK-CAB (July 2015)

- The question of when to start HIV treatment.

- The differences between observational studies and randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

- Design of the START study.

- Top-line results and implications.

- Draft UK BHIVA treatment guidelines: key changes and how to comment.

PowerPoint slides UK-CAB july 2015 (250 Kb) PDF file UK-CAB july 2015 (160 Kb)

Treatment Q&A at Bloomsbury Clinic (May 2015)

The talk included a doctor, a study researcher and an advocate.

PowerPoint – (4.5 MB) PDF – (4.8 Mb)

Are patient information leaflets for research studies too difficult to read? (April 2015)

It was a small study lead by advocates at i-Base and was selected by the conference for an oral presentation (Abstract O_4).

The study calculated readability scores from nine ongoing studies and compared them to two community-produced examples.

The presentation was also awarded one of two prizes from BHIVA and Mediscript for the best oral or poster research on social science or community-based work.

PowerPoint slides (1.6 Mb) PDF version – (1.1 Mb)

Community feedback from CROI 2015 – UK-CAB (April 2015)

- The PROUD and IPERGAY studies

- Other PrEP studies including PARTNERS PrEP and FACTS 001.

- TAF – new version of TDF

- Attachment inhibitors and maturation inhibitors.

PowerPoint file – (5.3 Mb) PDF slides file – PDF (3MB) 6-up handout – PDF (1.2 Mb)

Seminar on PrEP and chemsex – Copenhagen (March 2015)

Talk about recent and current experiences in the UK about PrEP.

This included community involvement in the PROUD study, the IDMC recommendation in October 2014 to offer PrEP to all participants, and community responses since.

Plus a short update on PrEP studies at CROI 2015.

The meeting was organised by the Danish HIV organisation AIDSFONDNET and included HIV positive and HIV negative community activists and health professionals.

PrEP talk copenhagen – PDF (5.9 Mb)

Imperial College BSc Global Health course (Jan 2015)

PDF file (1.5 MB)

Please email for higher resolution or PowerPoint files.

Imperial College medical students (Dec 2014)

Talk to 300 first-year medical students at Imperial College about role of patient/doctor partnership and communication. Also how treatment literacy can support people to take an active role in their healthcare.

Includes references to early US activism, including the Denver Principles (1983) and personal perspectives as a patient activist in the UK.

PowerPoint with notes (6.1 MB) PDF file (6.1 MB) – please email for higher resolution files .

PrEP: a community perspective (November 2014)

Talk about PrEP (Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis) from the HIV Conference in Glasgow. The talk looks at the history of PrEP and a few myths.

Although optimal use will be in situations where HIV risk is high, PrEP – just like TasP (Treatment as Prevention) – may help reduce stigma against HIV.

It may also help improve quality of life by reducing fear and anxiety about HIV.

Powerpoint with notes (7.5 MB) PDF file (2.4 MB) PrEP talk slide notes Word.doc (50 Kb)

This talk is available as a webcast. https://vimeo.com/244353226

Collins S. Journal of the International AIDS Society 2014, 17(Suppl 3) :19522 Conference abstract .

Option to use ART in early HIV infection (Oct 2014)

Talk about the importance for people who are diagnosed within 6 months of infection to be given the choice of using ART, irrespective of CD4 count. This short window may be very different to starting at any time after 6 months and yet many people do not have this discussion. Talk for BHIVA autumn conference 2014.

BHIVA 2014 early ART talk – PDF (200 Kb) BHIVA 2014 early ART talk – PowerPoint (400 Kb)

UK-CAB advocates training (Sep 2014)

- Introduction to science and importance of evidence-based medicine. Powerpoint slides (1 MB) and PDF (1.1 MB)

- Tips for writing patient-friendly information – Powerpoint slides (200 Kb) and PDF file (280 Kb)

Two talks for this 4-day UK-CAB advocacy training .

Health service constraints on HIV care – the research agenda: a UK perspective (March 2014)

Short presentation to European CHAIN research network to mark the completion of this five-year research programme. PDF and PowerPoint (500 Mb)

Community views on long-acting ARVs (March 2014)

Short presentation to US NIH mixed stakeholder meeting (researchers, regulators, industry and community) on the development of long-acting HIV meds, especially injections. PowerPoint (600 Mb) and PDF (400 Mb),

Talk to medical students (Nov 2013)

Talk to 300 first-year medical students at Imperial College about how HIV activism has affected patent involvement in care. Powerpoint (with notes) (6 MB) and PDF (slides only) (6 MB)

Hot topics in HIV treatment (Oct 2013)

Talk to UK HIV positive conference on six important topics that could change HIV care in the next year: Access to ARVs and generics in the new NHS/When to start and why guidelines differ… /Treatment as Prevention/New HIV drugs: Stribild, dolutegravir, TAF, GSK-744/Hepatitis C and sexual transmission/Hepatitis C: new HCV drugs (DAAs) – PDF (98 Kb)

UK-CAB advocates training (Oct 2013)

- Introduction to science and importance of evidence-based medicine. Powerpoint slides (1 MB) and PDF (1.1 MB)

- Tips for writing patient-friendly information – Powerpoint slides (200 Kb) and PDF file (280 Kb)

HIV and cancer (April 2013)

This talk highlights that it is mainly because HIV treatment is so effective that we are living long enough for cancer to be a complication. For nearly all cancers, older age is one of the key risk factors.

HIV makes the risk of some cancers slightly higher than the general population. These risks are still relatively unlikely events. To reduce these risks, the same lifestyle changes as the general population are just as important for HIV positive people – perhaps more so.

From a personal perspective, managing a cancer diagnosis is serious and meant you have to make your health a main priority to give yourself the best chance. This gives many people a new chance to make the most of their time, irrespective of the outcome.

PowerPoint (135 Kb) PDF (70 Kb)

HIV cure research: pieces in the puzzle (January 2013)

This non technical talk explains the science behind four key approaches to cure research. This is a puzzle and all four are likely to be needed on the way to finding a cure.

The context includes the context for the research, background on why a cure is difficult and ethical issues related to this research.

PowerPoint (2.5 Mb) PDF (3.4 Mb)

Budget issues affecting treatment choice: the London tender process (November 2012)

PowerPoint slides November 2012 – (180 Kb) PDF file (140 Kb) Text notes (Word.docx)

This talk is available as a webcast on the conference website: MAC webcast – PC webcast .

IAS July 2012 – Washington

Feedback from the International AIDS conference held in Washington in July 2012: PDF (400 Kb) PowerPoint (975 Kb)

Slides for a talk at a feedback meeting organised by the UK Consortium .

CROI February 2010 – San Francisco

A talk on community perspectives from the Retroviruses Conference (CROI) given to the feedback meetings organised by BHIVA.

- BHIVA CROI community slides reduced PDF (4MB)

Treatment Action Campaign

- Factsheet: measures used for CD4 and viral load (millilitre, microlitre, mL, mm3, μL) PDF Jan 2010

Showing the different measures for CD4 counts and viral load including millilitre, microlitre, mL, mm3, μL). Also, showing why you still have many millions of CD4 cells in your body even at very low CD4 counts.

- Pharmacology: how drugs are absorbed in your body PDF – Jan 2010

Set of graphs showing how drugs are absorbed and then leave your body and how missing a dose leads to low levels and the risk of resistance. Explains the pharmocology terms including Cmax, Tmax, half-life (T½), MEC (minimum effective concentration) etc.

- Key studies and new issues from 2009 research PDF – 2009

Set of 12 slides listing important studies and issues from 2010.

- Introduction to drug resistanceTAC PDF – 2008

Trials and Research

- Community involvement in Data & Safety Monitoring Boards (DSMB)

What is a DSMB, why should community members be involved, what is required. Training for the European Community Advisory Board.

UK-CAB presentations

- Presentations from more than 75 UK-CAB meetings

Slides from all UK-CAB meetings are posted online as an open access training resource.

Conference slides (archive)

- Retrovirus conference (CROI) 2008: ARVs – PDF

- IAS conference 2007 feedback (Sydney) – PDF ,

- IAS conference 2006 feedback (Toronto) – PowerPoint

- Drug development timelines (2006) TAC – PDF , PowerPoint

- Importance of treatment literacy (2006) Moscow – PowerPoint

- Community outreach in national and international trials (2006) MRC – PowerPoint