Graduate Writing Center

Introductions, thesis statements, and roadmaps - graduate writing center.

- Citations / Avoiding Plagiarism

- Critical Thinking

- Discipline-Specific Resources

- Generative AI

- iThenticate FAQ

- Types of Papers

- Standard Paper Structure

Introductions, Thesis Statements, and Roadmaps

- Body Paragraphs and Topic Sentences

- Literature Reviews

- Conclusions

- Executive Summaries and Abstracts

- Punctuation

- Style: Clarity and Concision

- Writing Process

- Writing a Thesis

- Quick Clips & Tips

- Presentations and Graphics

The first paragraph or two of any paper should be constructed with care, creating a path for both the writer and reader to follow. However, it is very common to adjust the introduction more than once over the course of drafting and revising your document. In fact, it is normal (and often very useful, or even essential!) to heavily revise your introduction after you've finished composing the paper, since that is most likely when you have the best grasp on what you've been aiming to say.

The introduction is your opportunity to efficiently establish for your reader the topic and significance of your discussion, the focused argument or claim you’ll make contained in your thesis statement, and a sense of how your presentation of information will proceed.

There are a few things to avoid in crafting good introductions. Steer clear of unnecessary length: you should be able to effectively introduce the critical elements of any project a page or less. Another pitfall to watch out for is providing excessive history or context before clearly stating your own purpose. Finally, don’t lose time stalling because you can't think of a good first line. A funny or dramatic opener for your paper (also known as “a hook”) can be a nice touch, but it is by no means a required element in a good academic paper.

Introductions, Thesis Statements, and Roadmaps Links

- Short video (5:47): " Writing an Introduction to a Paper ," GWC

- Handout (printable): " Introductions ," University of North Carolina Chapel Hill Writing Center

- Handout (printable): " Thesis Statements ," University of North Carolina Chapel Hill Writing Center

- NPS-specific one-page (printable) S ample Thesis Chapter Introduction with Roadmap , from "Venezuela: A Revolution on Standby," Luis Calvo

- Short video (3:39): " Writing Ninjas: How to Write a Strong Thesis Statement "

- Video (5:06): " Thesis Statements ," Purdue OWL

Writing Topics A–Z

This index makes findings topics easy and links to the most relevant page for each item. Please email us at [email protected] if we're missing something!

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

Thesis Statements

What this handout is about.

This handout describes what a thesis statement is, how thesis statements work in your writing, and how you can craft or refine one for your draft.

Introduction

Writing in college often takes the form of persuasion—convincing others that you have an interesting, logical point of view on the subject you are studying. Persuasion is a skill you practice regularly in your daily life. You persuade your roommate to clean up, your parents to let you borrow the car, your friend to vote for your favorite candidate or policy. In college, course assignments often ask you to make a persuasive case in writing. You are asked to convince your reader of your point of view. This form of persuasion, often called academic argument, follows a predictable pattern in writing. After a brief introduction of your topic, you state your point of view on the topic directly and often in one sentence. This sentence is the thesis statement, and it serves as a summary of the argument you’ll make in the rest of your paper.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement:

- tells the reader how you will interpret the significance of the subject matter under discussion.

- is a road map for the paper; in other words, it tells the reader what to expect from the rest of the paper.

- directly answers the question asked of you. A thesis is an interpretation of a question or subject, not the subject itself. The subject, or topic, of an essay might be World War II or Moby Dick; a thesis must then offer a way to understand the war or the novel.

- makes a claim that others might dispute.

- is usually a single sentence near the beginning of your paper (most often, at the end of the first paragraph) that presents your argument to the reader. The rest of the paper, the body of the essay, gathers and organizes evidence that will persuade the reader of the logic of your interpretation.

If your assignment asks you to take a position or develop a claim about a subject, you may need to convey that position or claim in a thesis statement near the beginning of your draft. The assignment may not explicitly state that you need a thesis statement because your instructor may assume you will include one. When in doubt, ask your instructor if the assignment requires a thesis statement. When an assignment asks you to analyze, to interpret, to compare and contrast, to demonstrate cause and effect, or to take a stand on an issue, it is likely that you are being asked to develop a thesis and to support it persuasively. (Check out our handout on understanding assignments for more information.)

How do I create a thesis?

A thesis is the result of a lengthy thinking process. Formulating a thesis is not the first thing you do after reading an essay assignment. Before you develop an argument on any topic, you have to collect and organize evidence, look for possible relationships between known facts (such as surprising contrasts or similarities), and think about the significance of these relationships. Once you do this thinking, you will probably have a “working thesis” that presents a basic or main idea and an argument that you think you can support with evidence. Both the argument and your thesis are likely to need adjustment along the way.

Writers use all kinds of techniques to stimulate their thinking and to help them clarify relationships or comprehend the broader significance of a topic and arrive at a thesis statement. For more ideas on how to get started, see our handout on brainstorming .

How do I know if my thesis is strong?

If there’s time, run it by your instructor or make an appointment at the Writing Center to get some feedback. Even if you do not have time to get advice elsewhere, you can do some thesis evaluation of your own. When reviewing your first draft and its working thesis, ask yourself the following :

- Do I answer the question? Re-reading the question prompt after constructing a working thesis can help you fix an argument that misses the focus of the question. If the prompt isn’t phrased as a question, try to rephrase it. For example, “Discuss the effect of X on Y” can be rephrased as “What is the effect of X on Y?”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? If your thesis simply states facts that no one would, or even could, disagree with, it’s possible that you are simply providing a summary, rather than making an argument.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? Thesis statements that are too vague often do not have a strong argument. If your thesis contains words like “good” or “successful,” see if you could be more specific: why is something “good”; what specifically makes something “successful”?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? If a reader’s first response is likely to be “So what?” then you need to clarify, to forge a relationship, or to connect to a larger issue.

- Does my essay support my thesis specifically and without wandering? If your thesis and the body of your essay do not seem to go together, one of them has to change. It’s okay to change your working thesis to reflect things you have figured out in the course of writing your paper. Remember, always reassess and revise your writing as necessary.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? If a reader’s first response is “how?” or “why?” your thesis may be too open-ended and lack guidance for the reader. See what you can add to give the reader a better take on your position right from the beginning.

Suppose you are taking a course on contemporary communication, and the instructor hands out the following essay assignment: “Discuss the impact of social media on public awareness.” Looking back at your notes, you might start with this working thesis:

Social media impacts public awareness in both positive and negative ways.

You can use the questions above to help you revise this general statement into a stronger thesis.

- Do I answer the question? You can analyze this if you rephrase “discuss the impact” as “what is the impact?” This way, you can see that you’ve answered the question only very generally with the vague “positive and negative ways.”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not likely. Only people who maintain that social media has a solely positive or solely negative impact could disagree.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? No. What are the positive effects? What are the negative effects?

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? No. Why are they positive? How are they positive? What are their causes? Why are they negative? How are they negative? What are their causes?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? No. Why should anyone care about the positive and/or negative impact of social media?

After thinking about your answers to these questions, you decide to focus on the one impact you feel strongly about and have strong evidence for:

Because not every voice on social media is reliable, people have become much more critical consumers of information, and thus, more informed voters.

This version is a much stronger thesis! It answers the question, takes a specific position that others can challenge, and it gives a sense of why it matters.

Let’s try another. Suppose your literature professor hands out the following assignment in a class on the American novel: Write an analysis of some aspect of Mark Twain’s novel Huckleberry Finn. “This will be easy,” you think. “I loved Huckleberry Finn!” You grab a pad of paper and write:

Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn is a great American novel.

You begin to analyze your thesis:

- Do I answer the question? No. The prompt asks you to analyze some aspect of the novel. Your working thesis is a statement of general appreciation for the entire novel.

Think about aspects of the novel that are important to its structure or meaning—for example, the role of storytelling, the contrasting scenes between the shore and the river, or the relationships between adults and children. Now you write:

In Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain develops a contrast between life on the river and life on the shore.

- Do I answer the question? Yes!

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not really. This contrast is well-known and accepted.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? It’s getting there–you have highlighted an important aspect of the novel for investigation. However, it’s still not clear what your analysis will reveal.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? Not yet. Compare scenes from the book and see what you discover. Free write, make lists, jot down Huck’s actions and reactions and anything else that seems interesting.

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? What’s the point of this contrast? What does it signify?”

After examining the evidence and considering your own insights, you write:

Through its contrasting river and shore scenes, Twain’s Huckleberry Finn suggests that to find the true expression of American democratic ideals, one must leave “civilized” society and go back to nature.

This final thesis statement presents an interpretation of a literary work based on an analysis of its content. Of course, for the essay itself to be successful, you must now present evidence from the novel that will convince the reader of your interpretation.

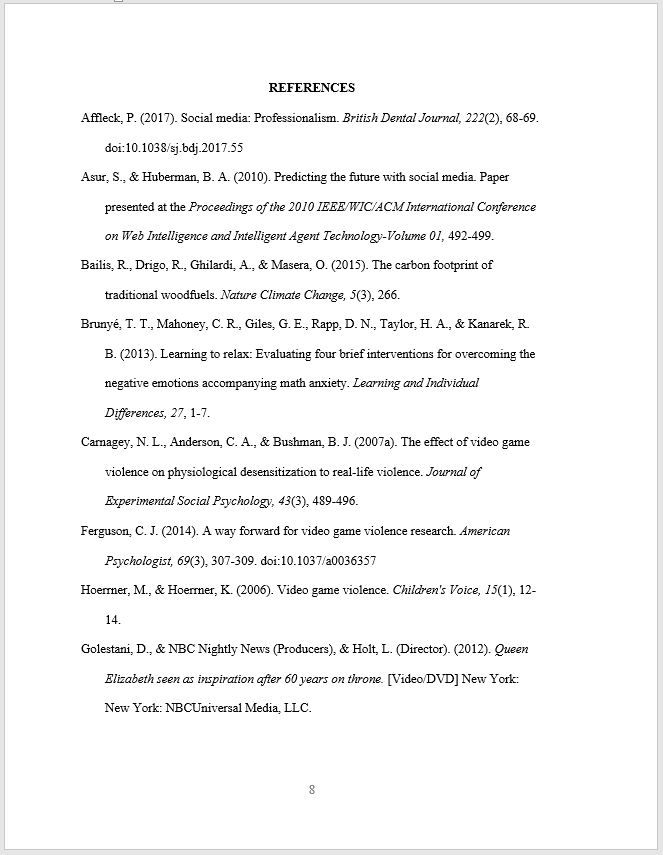

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Lunsford, Andrea A. 2015. The St. Martin’s Handbook , 8th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Ramage, John D., John C. Bean, and June Johnson. 2018. The Allyn & Bacon Guide to Writing , 8th ed. New York: Pearson.

Ruszkiewicz, John J., Christy Friend, Daniel Seward, and Maxine Hairston. 2010. The Scott, Foresman Handbook for Writers , 9th ed. Boston: Pearson Education.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Chapter 4: From Thesis to Essay

The Three-Storey Thesis as a Roadmap

Congratulations! Now you are ready to begin structuring your essay. Good news: you already have a logical blueprint in hand in the form of your three-storey thesis.

The next step in the pre-writing phase is creating a roadmap or outline for your essay. Taking the time to review your thesis statement and imagine paragraph-by-paragraph how your essay will flow before you start writing it will help in your revision process in that it will prevent you from writing parts of your essay and then having to delete them because they do not fit logically. You will also find that having a roadmap ahead of time will make the actual writing of your essay faster as you will know what is in each paragraph ahead of time.

A paragraph is a full and complete unit of thought within your essay. When you begin a new paragraph, you are signalling that you’ve completed that idea or point and are moving on to a new idea or point . The simplest way to create an essay outline is to look at your thesis statement, break it into its components, and then give each component its own paragraph by walking through each of the three storeys in sequence. Keep in mind that some components of an argument are more complex than others and may need two (or three or five) paragraphs to complete. But for now we’ll keep it simple and break our thesis into its basic parts. Let’s begin with our previous thesis statement, and then go storey by storey.

Write Here, Right Now: An Interactive Introduction to Academic Writing and Research Copyright © 2018 by Ryerson University is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

What is a thesis | A Complete Guide with Examples

Table of Contents

A thesis is a comprehensive academic paper based on your original research that presents new findings, arguments, and ideas of your study. It’s typically submitted at the end of your master’s degree or as a capstone of your bachelor’s degree.

However, writing a thesis can be laborious, especially for beginners. From the initial challenge of pinpointing a compelling research topic to organizing and presenting findings, the process is filled with potential pitfalls.

Therefore, to help you, this guide talks about what is a thesis. Additionally, it offers revelations and methodologies to transform it from an overwhelming task to a manageable and rewarding academic milestone.

What is a thesis?

A thesis is an in-depth research study that identifies a particular topic of inquiry and presents a clear argument or perspective about that topic using evidence and logic.

Writing a thesis showcases your ability of critical thinking, gathering evidence, and making a compelling argument. Integral to these competencies is thorough research, which not only fortifies your propositions but also confers credibility to your entire study.

Furthermore, there's another phenomenon you might often confuse with the thesis: the ' working thesis .' However, they aren't similar and shouldn't be used interchangeably.

A working thesis, often referred to as a preliminary or tentative thesis, is an initial version of your thesis statement. It serves as a draft or a starting point that guides your research in its early stages.

As you research more and gather more evidence, your initial thesis (aka working thesis) might change. It's like a starting point that can be adjusted as you learn more. It's normal for your main topic to change a few times before you finalize it.

While a thesis identifies and provides an overarching argument, the key to clearly communicating the central point of that argument lies in writing a strong thesis statement.

What is a thesis statement?

A strong thesis statement (aka thesis sentence) is a concise summary of the main argument or claim of the paper. It serves as a critical anchor in any academic work, succinctly encapsulating the primary argument or main idea of the entire paper.

Typically found within the introductory section, a strong thesis statement acts as a roadmap of your thesis, directing readers through your arguments and findings. By delineating the core focus of your investigation, it offers readers an immediate understanding of the context and the gravity of your study.

Furthermore, an effectively crafted thesis statement can set forth the boundaries of your research, helping readers anticipate the specific areas of inquiry you are addressing.

Different types of thesis statements

A good thesis statement is clear, specific, and arguable. Therefore, it is necessary for you to choose the right type of thesis statement for your academic papers.

Thesis statements can be classified based on their purpose and structure. Here are the primary types of thesis statements:

Argumentative (or Persuasive) thesis statement

Purpose : To convince the reader of a particular stance or point of view by presenting evidence and formulating a compelling argument.

Example : Reducing plastic use in daily life is essential for environmental health.

Analytical thesis statement

Purpose : To break down an idea or issue into its components and evaluate it.

Example : By examining the long-term effects, social implications, and economic impact of climate change, it becomes evident that immediate global action is necessary.

Expository (or Descriptive) thesis statement

Purpose : To explain a topic or subject to the reader.

Example : The Great Depression, spanning the 1930s, was a severe worldwide economic downturn triggered by a stock market crash, bank failures, and reduced consumer spending.

Cause and effect thesis statement

Purpose : To demonstrate a cause and its resulting effect.

Example : Overuse of smartphones can lead to impaired sleep patterns, reduced face-to-face social interactions, and increased levels of anxiety.

Compare and contrast thesis statement

Purpose : To highlight similarities and differences between two subjects.

Example : "While both novels '1984' and 'Brave New World' delve into dystopian futures, they differ in their portrayal of individual freedom, societal control, and the role of technology."

When you write a thesis statement , it's important to ensure clarity and precision, so the reader immediately understands the central focus of your work.

What is the difference between a thesis and a thesis statement?

While both terms are frequently used interchangeably, they have distinct meanings.

A thesis refers to the entire research document, encompassing all its chapters and sections. In contrast, a thesis statement is a brief assertion that encapsulates the central argument of the research.

Here’s an in-depth differentiation table of a thesis and a thesis statement.

Now, to craft a compelling thesis, it's crucial to adhere to a specific structure. Let’s break down these essential components that make up a thesis structure

15 components of a thesis structure

Navigating a thesis can be daunting. However, understanding its structure can make the process more manageable.

Here are the key components or different sections of a thesis structure:

Your thesis begins with the title page. It's not just a formality but the gateway to your research.

Here, you'll prominently display the necessary information about you (the author) and your institutional details.

- Title of your thesis

- Your full name

- Your department

- Your institution and degree program

- Your submission date

- Your Supervisor's name (in some cases)

- Your Department or faculty (in some cases)

- Your University's logo (in some cases)

- Your Student ID (in some cases)

In a concise manner, you'll have to summarize the critical aspects of your research in typically no more than 200-300 words.

This includes the problem statement, methodology, key findings, and conclusions. For many, the abstract will determine if they delve deeper into your work, so ensure it's clear and compelling.

Acknowledgments

Research is rarely a solitary endeavor. In the acknowledgments section, you have the chance to express gratitude to those who've supported your journey.

This might include advisors, peers, institutions, or even personal sources of inspiration and support. It's a personal touch, reflecting the humanity behind the academic rigor.

Table of contents

A roadmap for your readers, the table of contents lists the chapters, sections, and subsections of your thesis.

By providing page numbers, you allow readers to navigate your work easily, jumping to sections that pique their interest.

List of figures and tables

Research often involves data, and presenting this data visually can enhance understanding. This section provides an organized listing of all figures and tables in your thesis.

It's a visual index, ensuring that readers can quickly locate and reference your graphical data.

Introduction

Here's where you introduce your research topic, articulate the research question or objective, and outline the significance of your study.

- Present the research topic : Clearly articulate the central theme or subject of your research.

- Background information : Ground your research topic, providing any necessary context or background information your readers might need to understand the significance of your study.

- Define the scope : Clearly delineate the boundaries of your research, indicating what will and won't be covered.

- Literature review : Introduce any relevant existing research on your topic, situating your work within the broader academic conversation and highlighting where your research fits in.

- State the research Question(s) or objective(s) : Clearly articulate the primary questions or objectives your research aims to address.

- Outline the study's structure : Give a brief overview of how the subsequent sections of your work will unfold, guiding your readers through the journey ahead.

The introduction should captivate your readers, making them eager to delve deeper into your research journey.

Literature review section

Your study correlates with existing research. Therefore, in the literature review section, you'll engage in a dialogue with existing knowledge, highlighting relevant studies, theories, and findings.

It's here that you identify gaps in the current knowledge, positioning your research as a bridge to new insights.

To streamline this process, consider leveraging AI tools. For example, the SciSpace literature review tool enables you to efficiently explore and delve into research papers, simplifying your literature review journey.

Methodology

In the research methodology section, you’ll detail the tools, techniques, and processes you employed to gather and analyze data. This section will inform the readers about how you approached your research questions and ensures the reproducibility of your study.

Here's a breakdown of what it should encompass:

- Research Design : Describe the overall structure and approach of your research. Are you conducting a qualitative study with in-depth interviews? Or is it a quantitative study using statistical analysis? Perhaps it's a mixed-methods approach?

- Data Collection : Detail the methods you used to gather data. This could include surveys, experiments, observations, interviews, archival research, etc. Mention where you sourced your data, the duration of data collection, and any tools or instruments used.

- Sampling : If applicable, explain how you selected participants or data sources for your study. Discuss the size of your sample and the rationale behind choosing it.

- Data Analysis : Describe the techniques and tools you used to process and analyze the data. This could range from statistical tests in quantitative research to thematic analysis in qualitative research.

- Validity and Reliability : Address the steps you took to ensure the validity and reliability of your findings to ensure that your results are both accurate and consistent.

- Ethical Considerations : Highlight any ethical issues related to your research and the measures you took to address them, including — informed consent, confidentiality, and data storage and protection measures.

Moreover, different research questions necessitate different types of methodologies. For instance:

- Experimental methodology : Often used in sciences, this involves a controlled experiment to discern causality.

- Qualitative methodology : Employed when exploring patterns or phenomena without numerical data. Methods can include interviews, focus groups, or content analysis.

- Quantitative methodology : Concerned with measurable data and often involves statistical analysis. Surveys and structured observations are common tools here.

- Mixed methods : As the name implies, this combines both qualitative and quantitative methodologies.

The Methodology section isn’t just about detailing the methods but also justifying why they were chosen. The appropriateness of the methods in addressing your research question can significantly impact the credibility of your findings.

Results (or Findings)

This section presents the outcomes of your research. It's crucial to note that the nature of your results may vary; they could be quantitative, qualitative, or a mix of both.

Quantitative results often present statistical data, showcasing measurable outcomes, and they benefit from tables, graphs, and figures to depict these data points.

Qualitative results , on the other hand, might delve into patterns, themes, or narratives derived from non-numerical data, such as interviews or observations.

Regardless of the nature of your results, clarity is essential. This section is purely about presenting the data without offering interpretations — that comes later in the discussion.

In the discussion section, the raw data transforms into valuable insights.

Start by revisiting your research question and contrast it with the findings. How do your results expand, constrict, or challenge current academic conversations?

Dive into the intricacies of the data, guiding the reader through its implications. Detail potential limitations transparently, signaling your awareness of the research's boundaries. This is where your academic voice should be resonant and confident.

Practical implications (Recommendation) section

Based on the insights derived from your research, this section provides actionable suggestions or proposed solutions.

Whether aimed at industry professionals or the general public, recommendations translate your academic findings into potential real-world actions. They help readers understand the practical implications of your work and how it can be applied to effect change or improvement in a given field.

When crafting recommendations, it's essential to ensure they're feasible and rooted in the evidence provided by your research. They shouldn't merely be aspirational but should offer a clear path forward, grounded in your findings.

The conclusion provides closure to your research narrative.

It's not merely a recap but a synthesis of your main findings and their broader implications. Reconnect with the research questions or hypotheses posited at the beginning, offering clear answers based on your findings.

Reflect on the broader contributions of your study, considering its impact on the academic community and potential real-world applications.

Lastly, the conclusion should leave your readers with a clear understanding of the value and impact of your study.

References (or Bibliography)

Every theory you've expounded upon, every data point you've cited, and every methodological precedent you've followed finds its acknowledgment here.

In references, it's crucial to ensure meticulous consistency in formatting, mirroring the specific guidelines of the chosen citation style .

Proper referencing helps to avoid plagiarism , gives credit to original ideas, and allows readers to explore topics of interest. Moreover, it situates your work within the continuum of academic knowledge.

To properly cite the sources used in the study, you can rely on online citation generator tools to generate accurate citations!

Here’s more on how you can cite your sources.

Often, the depth of research produces a wealth of material that, while crucial, can make the core content of the thesis cumbersome. The appendix is where you mention extra information that supports your research but isn't central to the main text.

Whether it's raw datasets, detailed procedural methodologies, extended case studies, or any other ancillary material, the appendices ensure that these elements are archived for reference without breaking the main narrative's flow.

For thorough researchers and readers keen on meticulous details, the appendices provide a treasure trove of insights.

Glossary (optional)

In academics, specialized terminologies, and jargon are inevitable. However, not every reader is versed in every term.

The glossary, while optional, is a critical tool for accessibility. It's a bridge ensuring that even readers from outside the discipline can access, understand, and appreciate your work.

By defining complex terms and providing context, you're inviting a wider audience to engage with your research, enhancing its reach and impact.

Remember, while these components provide a structured framework, the essence of your thesis lies in the originality of your ideas, the rigor of your research, and the clarity of your presentation.

As you craft each section, keep your readers in mind, ensuring that your passion and dedication shine through every page.

Thesis examples

To further elucidate the concept of a thesis, here are illustrative examples from various fields:

Example 1 (History): Abolition, Africans, and Abstraction: the Influence of the ‘Noble Savage’ on British and French Antislavery Thought, 1787-1807 by Suchait Kahlon.

Example 2 (Climate Dynamics): Influence of external forcings on abrupt millennial-scale climate changes: a statistical modelling study by Takahito Mitsui · Michel Crucifix

Checklist for your thesis evaluation

Evaluating your thesis ensures that your research meets the standards of academia. Here's an elaborate checklist to guide you through this critical process.

Content and structure

- Is the thesis statement clear, concise, and debatable?

- Does the introduction provide sufficient background and context?

- Is the literature review comprehensive, relevant, and well-organized?

- Does the methodology section clearly describe and justify the research methods?

- Are the results/findings presented clearly and logically?

- Does the discussion interpret the results in light of the research question and existing literature?

- Is the conclusion summarizing the research and suggesting future directions or implications?

Clarity and coherence

- Is the writing clear and free of jargon?

- Are ideas and sections logically connected and flowing?

- Is there a clear narrative or argument throughout the thesis?

Research quality

- Is the research question significant and relevant?

- Are the research methods appropriate for the question?

- Is the sample size (if applicable) adequate?

- Are the data analysis techniques appropriate and correctly applied?

- Are potential biases or limitations addressed?

Originality and significance

- Does the thesis contribute new knowledge or insights to the field?

- Is the research grounded in existing literature while offering fresh perspectives?

Formatting and presentation

- Is the thesis formatted according to institutional guidelines?

- Are figures, tables, and charts clear, labeled, and referenced in the text?

- Is the bibliography or reference list complete and consistently formatted?

- Are appendices relevant and appropriately referenced in the main text?

Grammar and language

- Is the thesis free of grammatical and spelling errors?

- Is the language professional, consistent, and appropriate for an academic audience?

- Are quotations and paraphrased material correctly cited?

Feedback and revision

- Have you sought feedback from peers, advisors, or experts in the field?

- Have you addressed the feedback and made the necessary revisions?

Overall assessment

- Does the thesis as a whole feel cohesive and comprehensive?

- Would the thesis be understandable and valuable to someone in your field?

Ensure to use this checklist to leave no ground for doubt or missed information in your thesis.

After writing your thesis, the next step is to discuss and defend your findings verbally in front of a knowledgeable panel. You’ve to be well prepared as your professors may grade your presentation abilities.

Preparing your thesis defense

A thesis defense, also known as "defending the thesis," is the culmination of a scholar's research journey. It's the final frontier, where you’ll present their findings and face scrutiny from a panel of experts.

Typically, the defense involves a public presentation where you’ll have to outline your study, followed by a question-and-answer session with a committee of experts. This committee assesses the validity, originality, and significance of the research.

The defense serves as a rite of passage for scholars. It's an opportunity to showcase expertise, address criticisms, and refine arguments. A successful defense not only validates the research but also establishes your authority as a researcher in your field.

Here’s how you can effectively prepare for your thesis defense .

Now, having touched upon the process of defending a thesis, it's worth noting that scholarly work can take various forms, depending on academic and regional practices.

One such form, often paralleled with the thesis, is the 'dissertation.' But what differentiates the two?

Dissertation vs. Thesis

Often used interchangeably in casual discourse, they refer to distinct research projects undertaken at different levels of higher education.

To the uninitiated, understanding their meaning might be elusive. So, let's demystify these terms and delve into their core differences.

Here's a table differentiating between the two.

Wrapping up

From understanding the foundational concept of a thesis to navigating its various components, differentiating it from a dissertation, and recognizing the importance of proper citation — this guide covers it all.

As scholars and readers, understanding these nuances not only aids in academic pursuits but also fosters a deeper appreciation for the relentless quest for knowledge that drives academia.

It’s important to remember that every thesis is a testament to curiosity, dedication, and the indomitable spirit of discovery.

Good luck with your thesis writing!

Frequently Asked Questions

A thesis typically ranges between 40-80 pages, but its length can vary based on the research topic, institution guidelines, and level of study.

A PhD thesis usually spans 200-300 pages, though this can vary based on the discipline, complexity of the research, and institutional requirements.

To identify a thesis topic, consider current trends in your field, gaps in existing literature, personal interests, and discussions with advisors or mentors. Additionally, reviewing related journals and conference proceedings can provide insights into potential areas of exploration.

The conceptual framework is often situated in the literature review or theoretical framework section of a thesis. It helps set the stage by providing the context, defining key concepts, and explaining the relationships between variables.

A thesis statement should be concise, clear, and specific. It should state the main argument or point of your research. Start by pinpointing the central question or issue your research addresses, then condense that into a single statement, ensuring it reflects the essence of your paper.

You might also like

AI for Meta Analysis — A Comprehensive Guide

Cybersecurity in Higher Education: Safeguarding Students and Faculty Data

How To Write An Argumentative Essay

Roadmapping research

What is a scientific roadmap.

If you’re studying a STEM discipline, you could use your thesis to create a scientific or technological roadmap. Creating a roadmap can help identify novel strategies for achieving a goal and prioritise between them, by setting out constraints on the way to a goal and potential workarounds for them.

One approach to creating a scientific roadmap, described in the paper Architecting Discovery , involves:

- identifying a goal that science and technology has not yet achieved.

- mapping ‘currently practised and conceived approaches’ to trying to achieve the goal.

- identifying the fundamental limitations imposed by the laws of physics on how effective these approaches can be.

- identifying why it seems these fundamental limits haven’t been reached – i.e. what are the current technological bottlenecks preventing this?

Some potential methods of finding workarounds are:

- finding a hidden gem that already implements the workaround, by searching through existing knowledge in other scientific domains (or consulting experts in these domains) and transplanting this knowledge to the new domain, or by screening libraries of elements from nature and finding an example of a workaround occurring naturally.

The paper Physical Principles for Scalable Neural Recording is an example of a similar approach to roadmapping. This paper aims to identify promising strategies for ‘simultaneously measuring the activities of all neurons in a mammalian brain at millisecond resolution’ without damaging the brain.

Here are the steps of scientific roadmapping in more detail, based on the paper above:

- Establish the goal, e.g. ‘simultaneously measuring the activities of all neurons in a mammalian brain at millisecond resolution without damaging the brain.’

- Map out the landscape of modalities (current and conceived) aimed at achieving the goal (in this case, this includes approaches such as magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound).

- Identify how to assess how close each modality is to achieving the goal. (For example in the case of MRI, this is primarily determined by the spatial and temporal resolution that can currently be achieved).

- What fundamental limits is the use of each modality subject to? (For example, the speed that sound travels in the brain, or the degree of volume displacement that can occur in the brain without causing significant damage.)

- What is the potential of each of these modalities? Do some look more promising than others, in terms of how close they are to being viable?

What makes a good roadmap of a technical area?

Some things to bear in are:

- In the goal you’re focused on achieving well-defined and quantifiable?

- Is the goal interesting and relevant to some important outcome?

- Do you have (or can you acquire) enough understanding of how the system works? This is important so you can draw non-obvious, definitive conclusions from backchaining from the goal.

- Is the goal decomposable into necessary or sufficient conditions?

- Have logical, quantitative, or probabilistic limits been put on different paths to the goal?

Further reading

If you want to learn more about roadmapping research, you could listen to this episode of the Ideas Machine podcast with Adam Marblestone , one of the authors of the paper above. You could also look at his presentation on ‘Roadmapping Biology .’ The paper Architecting Discovery also provides an overview of this type of research in more detail.

Some examples of roadmapping in research papers are:

- Imaging, Sensing, and Communication Through Highly Scattering Complex Media

- JASON Defense Advisory Panel Reports

- Near-term climate risks and sunlight reflection modification: a roadmap approach for physical sciences research

- Productive Nanosystems – A Technology Roadmap

Effective Thesis

Privacy policy

Stay in touch

Are you interested in applying for coaching or to our other services in future? Stay in touch and get our quarterly updates by signing up to our newsletter!

Writing Center

Strategic enrollment management and student success, creating a research roadmap, ... so your paper doesn't crash.

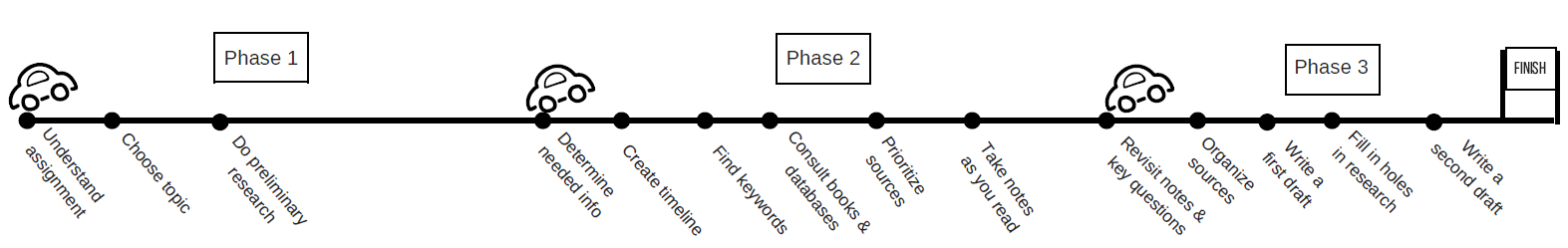

It’s easy to get daunted by the idea of starting a research project. Although “finding information” sounds pretty simple, many of us get overwhelmed when we starting thinking of all the things that go into finding what we need for a research project: figuring out where to look, understanding and determining what is important, deciding how to organize — not to mention incorporating all of this into the actual writing of your paper. Whew!

However, even though research can seem like an overwhelming task, if you are able to break “research” down into manageable chunks, you’ll find that it doesn’t have to be so bad. Research isn’t only finding information or facts; you will also find others’ viewpoints and interpretations of that information. And finally, you will add your interpretation to the mix so that your paper is not a report but a critical look at a topic.

Doing all of this, of course, takes some time and planning, so it can be helpful to think of doing research much like going on a road trip. You just don’t hop in the car and go; you also pack snacks, get directions, check your tire pressure, and find places to stop along the way. Research is the same way. Making a checklist and timeline of all the things you have to do will help you effectively reach your destination. Keep reading to find out how you can create a personal research roadmap that will help you reach your destination safely and without panic.

1) Creating a plan: Where you need to go

The first thing you need to do is make sure you understand the assignment . You don’t want to waste time doing work that won’t fit your project. If you’re not sure what you are supposed to be doing, consult classmates, your professor, or the Writing Center.

If you have the option to choose your topic for research, do this next. Keep in mind the parameters of the assignment, including date due, page length, and project objectives, so you don’t pick a topic that is too broad or narrow for the assignment.

Do some preliminary research on your topic. Consult general sources, such as class notes, textbooks, reference books, and the Internet. You won’t use this material in your final paper but it will give you general information to help you focus your topic choice.

Based on your preliminary research, figure out what types of material you will need to find for your paper. Remember that information consists of both facts and other peoples’ interpretations of those facts. Knowing what you need will make your research more focused, which will save you time.

Create a timeline for completing research. You should do Phase 1 very soon after receiving your assignment. Phase 2 and 3 will take the longest, so don't put them off to the last minute.

2) Doing the research: How to get there

Find keywords that get you into the topic. This may take some experimenting and the task can be frustrating, so use your preliminary research to help you figure out what terms are most relevant for your search.

You’ll probably be using mostly scholarly sources for your paper, so consult library books and electronic databases through the library’s website. (Google searches are not a good use of your time. Promise.) You can consult the help desk in the library or the Writing Center for help on searching.

Once you’ve done research, prioritize your sources . Start with more introductory material to learn the basic facts and then go for more evaluation and interpretation. Don’t feel you have to read every single word of every single source—scan for relevant material and then read more carefully in more important sections.

Take notes as you read your sources. Write down important ideas, quotations, and your own analysis. Writing as you read (instead of waiting ‘til the end) will save you lots of time and energy. Look for the central ideas of sources and think about how they could be organized. Allow ideas to emerge through your research.

3) Incorporating research: What to do while there

Revisit your notes and key quotations from your sources. Identify key concepts, ideas, and points of debate within your subject.

Think about how you can organize your sources around major points of interpretation instead of general topics. Revisit your assignment sheet to make sure you’re still on the right track.

Write a first draft so you can get your ideas out on paper. Divide your paper into smaller chunks so you can work on one chunk at a time. You don’t need to worry about getting everything perfect, but you do want to push your thinking to be analytical and critical. Skip writing the introduction for now. You’ll have a better idea of what to say after you write a draft.

Read your draft and determine if you need to fill holes in your research . Sometimes you won’t realize you need certain things until you start writing, so it helps to set aside some time to go back and do a bit more focused research.

Write a second draft . The value of a second draft can’t be emphasized enough. A second draft is a lot more than just a proofread first draft — it is a refining of your ideas. As you write, you’ll discover your ideas in the first draft; in the second, you’ll make them understandable to outside readers. (Psst—it’s easier to focus your ideas if you start with a blank document instead of trying to directly change your first draft.)

Use the timeline below to divide your research into 3 phases. The length of each phase will be determined by your deadline.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to Write a Thesis Statement | 4 Steps & Examples

How to Write a Thesis Statement | 4 Steps & Examples

Published on January 11, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on August 15, 2023 by Eoghan Ryan.

A thesis statement is a sentence that sums up the central point of your paper or essay . It usually comes near the end of your introduction .

Your thesis will look a bit different depending on the type of essay you’re writing. But the thesis statement should always clearly state the main idea you want to get across. Everything else in your essay should relate back to this idea.

You can write your thesis statement by following four simple steps:

- Start with a question

- Write your initial answer

- Develop your answer

- Refine your thesis statement

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is a thesis statement, placement of the thesis statement, step 1: start with a question, step 2: write your initial answer, step 3: develop your answer, step 4: refine your thesis statement, types of thesis statements, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about thesis statements.

A thesis statement summarizes the central points of your essay. It is a signpost telling the reader what the essay will argue and why.

The best thesis statements are:

- Concise: A good thesis statement is short and sweet—don’t use more words than necessary. State your point clearly and directly in one or two sentences.

- Contentious: Your thesis shouldn’t be a simple statement of fact that everyone already knows. A good thesis statement is a claim that requires further evidence or analysis to back it up.

- Coherent: Everything mentioned in your thesis statement must be supported and explained in the rest of your paper.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

The thesis statement generally appears at the end of your essay introduction or research paper introduction .

The spread of the internet has had a world-changing effect, not least on the world of education. The use of the internet in academic contexts and among young people more generally is hotly debated. For many who did not grow up with this technology, its effects seem alarming and potentially harmful. This concern, while understandable, is misguided. The negatives of internet use are outweighed by its many benefits for education: the internet facilitates easier access to information, exposure to different perspectives, and a flexible learning environment for both students and teachers.

You should come up with an initial thesis, sometimes called a working thesis , early in the writing process . As soon as you’ve decided on your essay topic , you need to work out what you want to say about it—a clear thesis will give your essay direction and structure.

You might already have a question in your assignment, but if not, try to come up with your own. What would you like to find out or decide about your topic?

For example, you might ask:

After some initial research, you can formulate a tentative answer to this question. At this stage it can be simple, and it should guide the research process and writing process .

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Now you need to consider why this is your answer and how you will convince your reader to agree with you. As you read more about your topic and begin writing, your answer should get more detailed.

In your essay about the internet and education, the thesis states your position and sketches out the key arguments you’ll use to support it.

The negatives of internet use are outweighed by its many benefits for education because it facilitates easier access to information.

In your essay about braille, the thesis statement summarizes the key historical development that you’ll explain.

The invention of braille in the 19th century transformed the lives of blind people, allowing them to participate more actively in public life.

A strong thesis statement should tell the reader:

- Why you hold this position

- What they’ll learn from your essay

- The key points of your argument or narrative

The final thesis statement doesn’t just state your position, but summarizes your overall argument or the entire topic you’re going to explain. To strengthen a weak thesis statement, it can help to consider the broader context of your topic.

These examples are more specific and show that you’ll explore your topic in depth.

Your thesis statement should match the goals of your essay, which vary depending on the type of essay you’re writing:

- In an argumentative essay , your thesis statement should take a strong position. Your aim in the essay is to convince your reader of this thesis based on evidence and logical reasoning.

- In an expository essay , you’ll aim to explain the facts of a topic or process. Your thesis statement doesn’t have to include a strong opinion in this case, but it should clearly state the central point you want to make, and mention the key elements you’ll explain.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

A thesis statement is a sentence that sums up the central point of your paper or essay . Everything else you write should relate to this key idea.

The thesis statement is essential in any academic essay or research paper for two main reasons:

- It gives your writing direction and focus.

- It gives the reader a concise summary of your main point.

Without a clear thesis statement, an essay can end up rambling and unfocused, leaving your reader unsure of exactly what you want to say.

Follow these four steps to come up with a thesis statement :

- Ask a question about your topic .

- Write your initial answer.

- Develop your answer by including reasons.

- Refine your answer, adding more detail and nuance.

The thesis statement should be placed at the end of your essay introduction .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, August 15). How to Write a Thesis Statement | 4 Steps & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 5, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/thesis-statement/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write an essay introduction | 4 steps & examples, how to write topic sentences | 4 steps, examples & purpose, academic paragraph structure | step-by-step guide & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

- IP – S24

- Innovations – S24

- About Professor Nathenson

- Legal scholarship

- Other writings

- Scholarship on SSRN

- Scholarship on Bepress

- IP@STU: IP Certificate

- About Civil Procedure

- Assignments

- Study resources

- Nathenson.org MBE resources

- YouTube MBE playlists

- Subject matter jurisdiction

- Due Process, notice, service

- Personal jurisdiction

- Erie Doctrine

- Motions, trial, judgments

- Claim & Issue Preclusion

- Innovations & Patent Management

- Intellectual Property

- Trademark & Branding Law

- IP certificate

- - About Professor Nathenson

- - C.V.

- - Contact me

- - Legal scholarship

- - Other writings

- - Scholarship on SSRN

- - Scholarship on Bepress

- - IP@STU: IP Certificate

- - About Civil Procedure

- - Syllabus

- - Assignments

- - Study resources

- - About Professor Nathenson

- - Nathenson.org MBE resources

- - YouTube MBE playlists

- - By topic

- - Subject matter jurisdiction

- - Due Process, notice, service

- - Personal jurisdiction

- - MBE: Venue

- - Pleadings

- - Joinder

- - Erie Doctrine

- - Discovery

- - Motions, trial, judgments

- - Claim & Issue Preclusion

- - Appeals

- - Innovations & Patent Management

- - Intellectual Property

- - Trademark & Branding Law

The introduction and roadmap

Here are some suggestions on writing the introduction to your paper.

It’s a contract between the author and reader. Make sure that the introduction corresponds to what the paper actually says, and vice-versa. If you say in the intro that you’ll cover something, then be sure to cover it.

Write a rough version of it early. Free-write your introduction early on. You’ll revise it significantly, but I’ve always found that forcing myself to write the introduction early on gets me thinking more holistically about how the parts of the paper fit together.

Come back to the introduction as you revise. Don’t spend to much time on your introduction, but it helps from time to time to do a “reality check” by looking back at your introduction. Are you forgetting things that should be in the paper? Has your thinking changed? Do you need to reorganize what you say, and where?

Revise it carefully at the end. As noted, the final version of your introduction should match what you actually say in the body of the paper.

Length. For a 30-page student paper, I’d recommend that your introduction be no more than 2-4 pages. If you believe it needs to be longer, chances are you are trying to put background information in the introduction that should instead go elsewhere.

Components of an introduction. See Fajans and Falk pp. 87-88. A good introduction should include matters discussed there (and credit to Professor Eugene Volokh for his discussion in Academic Legal Writing regarding utility/novelty/nonobviousness):

Your topic. What is the problem or question your paper addresses?

Your thesis. What is your answer to the question, or your solution?

Utility. Don’t actually use the term “utility,” but be sure to explain why your topic and thesis are important to the reader.

Novelty & nonobviousness. Don’t use those terms, but be sure to explain why your paper contains something new, and why your original contribution is more than an obvious addition to what came before.

Roadmap. The introduction traditionally closes with a roadmap that lists — by part — what each part of the paper will do. For example, here’s a roadmap from my article Civil Procedures for a World of Shared and User-Generated Content , 48 U. Louisville L. Rev. 911 (2010) (part I is not listed below because it was the introduction).

“Part II notes how the interplay between copyright substance and procedure can lead to a substance-procedure-substance feedback loop. It also lays out a descriptive framework for copyright procedure derived from the actors, sources, and functions of those procedures. Part III examines three major types of private enforcement procedures, namely direct, indirect, and automated copyright enforcement, and considers how they foster feedback loops. It also makes a number of suggestions aimed at improving the balance between owners and users. Part IV considers the values attendant to procedural justice in copyright enforcement, and sets forth a normative framework that looks to principles of participation, transparency, and “balanced accuracy” that might lead to private enforcement procedures that better accommodate the reasonable cost and efficiency needs of copyright owners without trampling on UGC.”

Last revised Oct. 7, 2014

The Roadmap to Writing your Thesis

Most students are quite overwhelmed at the idea that they are tasked to write a hundred or more pages for the thesis or dissertation component for their course. And many do not know where to start. What should the chapter outlines be? What kind of content should be on those chapters?

This article is intended to provide you with a simple, yet practical roadmap to getting your thesis document started. The bullet points below should serve as a strong guideline and give you a solid start but bear in mind that there is a lot more to it than that.

It is imperative that right from the beginning you understand your institution’s technical requirements for the actual thesis document: title page layout, margins, font, line spacing, tables and figures descriptions, format of front page, format of table of contents and any other technical aspects that you need to know.

Spend the time you need to get your thesis document set up in your word processor in the correct format and back it up. You now have your working document and you can start populating it with your own work.

With minor differences, your thesis will follow this basic format.

THE BEGINNING

- Declaration

- Acknowledgements

The abstract is a very tight summary and it will be the first substantive description of your work read by an external examiner. Therefore, it must represent all the elements of your work in a highly condensed manner. It is not an introduction.

- List of tables

- List of figures

- List of acronyms and abbreviations

THE FIVE CHAPTERS (THE MIDDLE)

- INTRODUCTION

- Describes the background for your chosen topic.

- Highlights your research topic and question and describes your aims and objective.

- Describes the purpose and benefits of the study.

- LITERATURE REVIEW

- Confirm your keywords/constructs – this determines your search criteria.

- Know your supervisor’s expectations in terms of your LR.

- Know when to stop reading and start writing.

- Keep an efficient article storage system for easy access later on.

- As you read, begin the writing process, add snippets from your readings with the correct references and populate your literature review.

- Use simple tools to put connections and comparisons out where you can see them. I highly recommend you read They say, I say book to learn how to achieve this.

- [insert pot of gold video]

- Organize your sources in a way that makes it drop-dead easy to write a strong review, and to do this I recommend that you make use of software which is readily available such as Mendeley or Refworks.

READ: 8 Technical tools to help you kick thesis writing butt

- RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

- Describe the background and design.

- Discuss the explicit data collection and data analysis process you used.

- Decide on data analysis software, if any.

- Explain your ethical procedures.

- Confirm your methodological fit with your supervisor.

- RESULTS / INTERPRETATION OF DATA

- Summary of your study.

- Conclusions you found.

- Contributions and limitations.

- Recommendations for further research.

- Connect all the dots.

- Reference List

- Appendices as referred to in text

If you see the writing of your thesis as a learning curve and not something you need to excel at on the first try, you’ll find that you are more receptive to advice. Not only that, you’ll see criticism as valuable feedback to help you make changes to get it right. Don’t forget to ask for help. Read more about mindset here.

Get excited about submitting your thesis– it should be an intellectual challenge and not a horror story.

What is a roadmap?

- Resources /

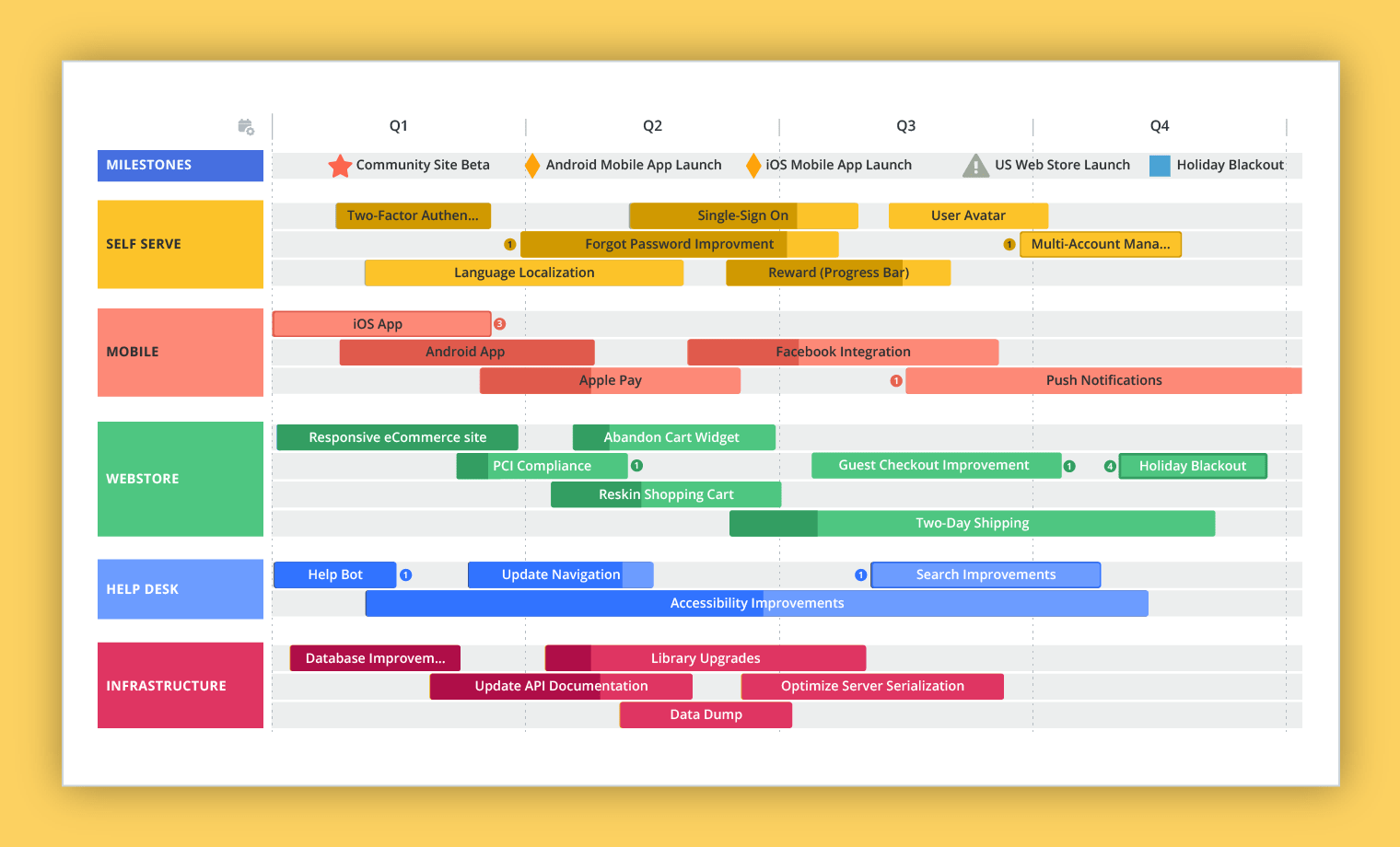

Roadmaps can smooth alignment, improve strategic organization and centralize team collaboration—regardless of what kind of business you have.

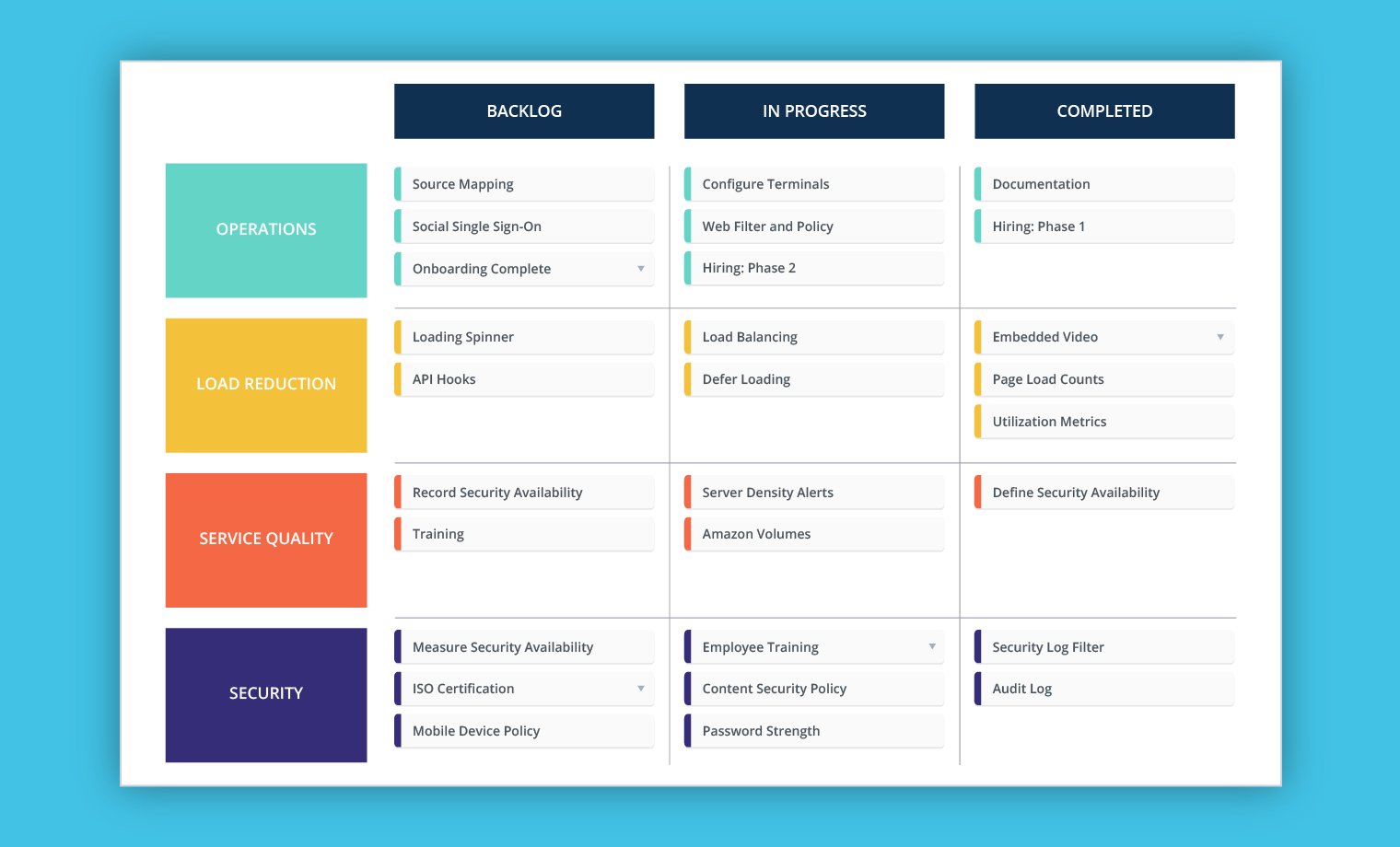

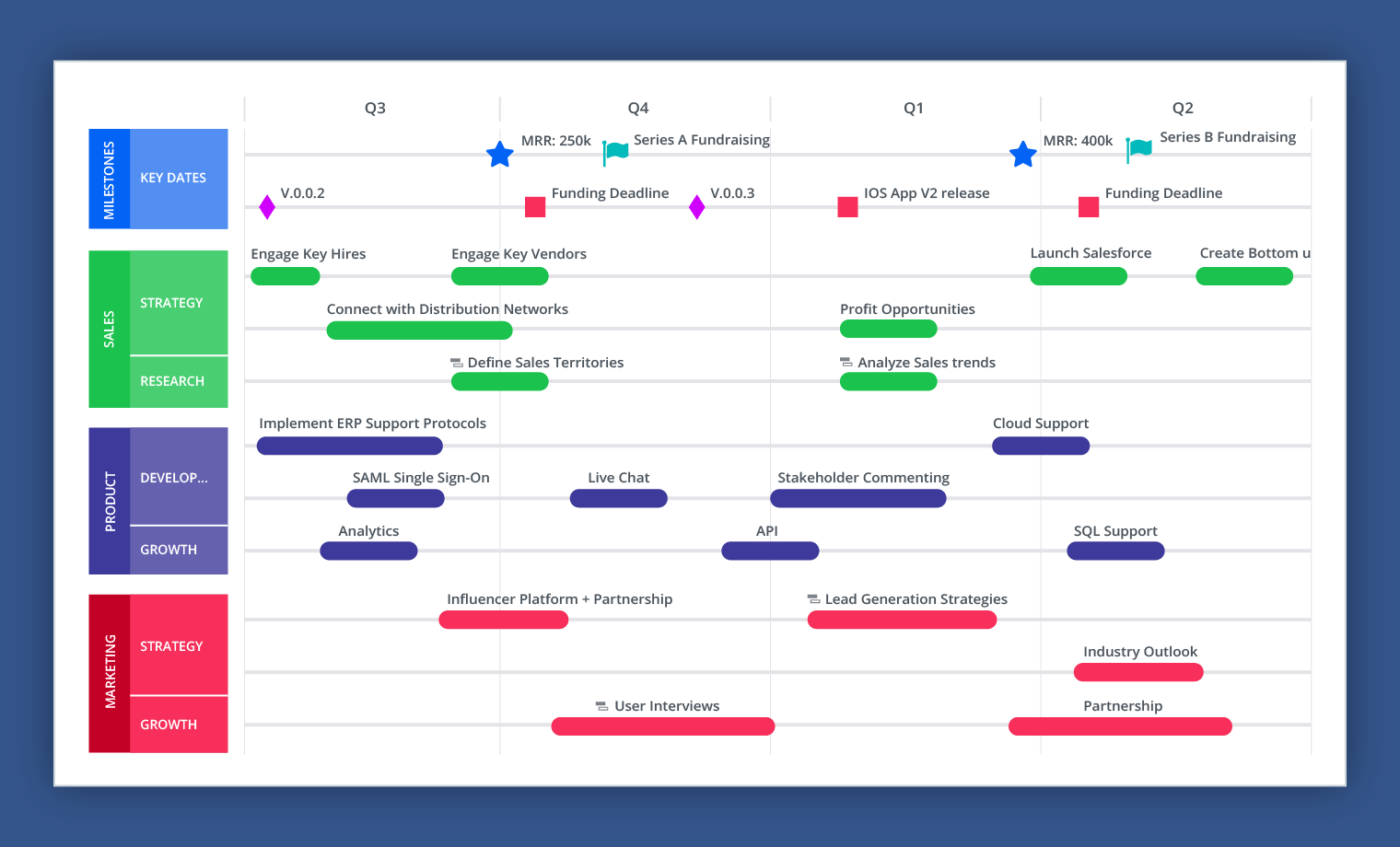

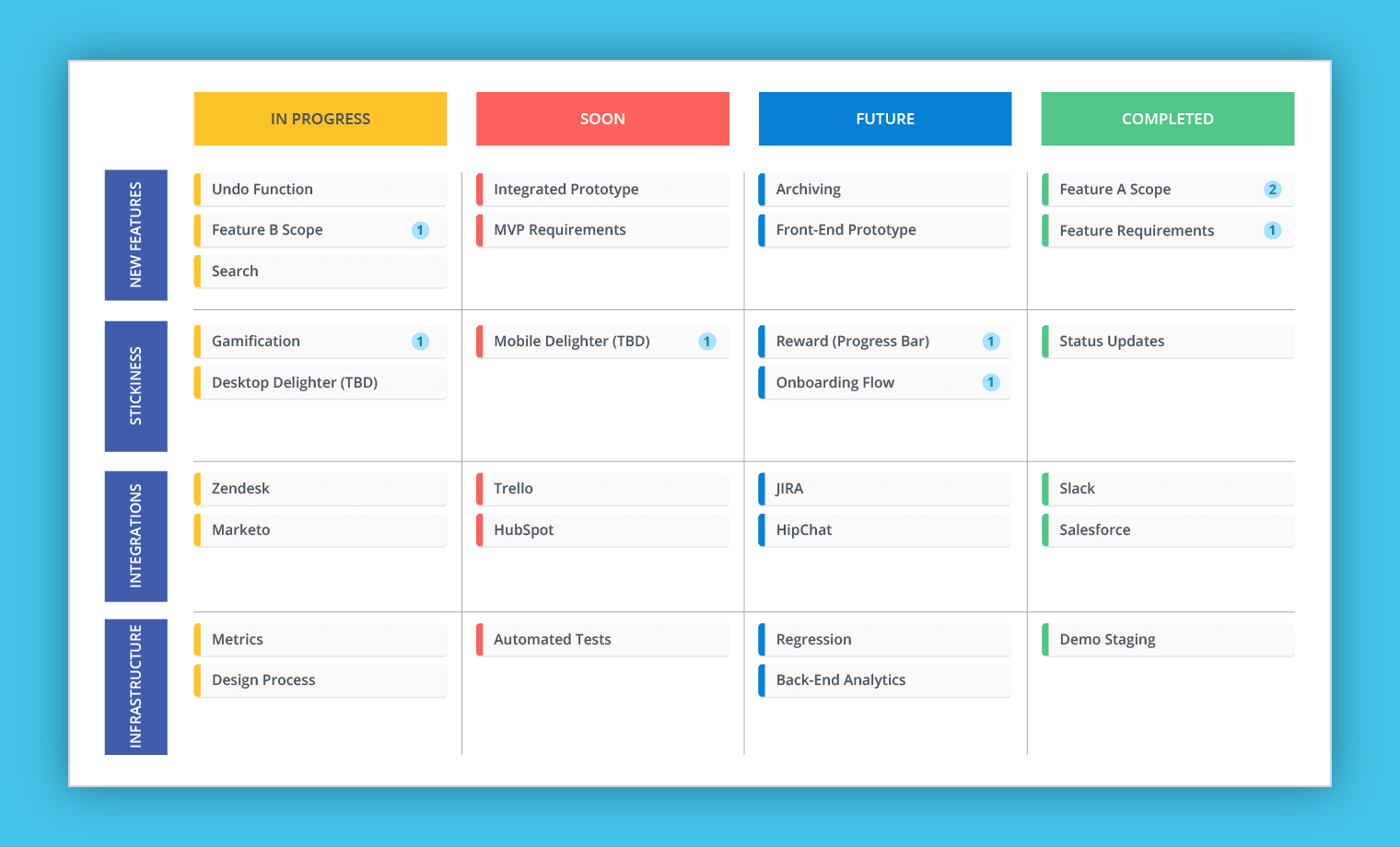

An organization-wide roadmapping process can help you bring business goals front and center for everyone to understand and act on. This high-level document is a visual representation of a strategy : it answers the questions of what will be done, who will be involved in the work, the details of scope and resource allocation, as well as how and why certain initiatives were prioritized over others.

When teams work together and rally around a visual plan for how to grow, maintain and expand the business, they have what they need to go a lot further, a lot faster.

That's why your strategy can’t live in a silo . You need a way to communicate it visually to your decision-makers and stakeholders, so they know you’re on top of it. And you need to do it in a way that makes you look good and confident!

From visual product roadmaps to marketing, HR and project roadmaps , this guide will give you the roadmapping basics you need to kick-start a roadmapping process at your organization.

Visualize your strategy as a beautiful, easy-to-share roadmap. Get started in minutes with one of the roadmaps in our library .

A visual roadmap is a communication tool. They're created and presented to get all stakeholders and your entire team aligned on one strategy.

The basic definition of a roadmap is simple: it’s a visual way to quickly communicate a plan or strategy .

Every team has a plan and strategy built around doing what pushes the business goals forward. When you’re busy executing the strategy, you can get lost in day-to-day task management. A roadmap is one of the most effective tools for rising above the granular details and chaos. Roadmaps give you a bird's-eye view of everything that’s happening at your team or company.

And with the right tool, you can roll up all those different strategies into one master view that allows you to see how all these pieces are connected and aligned with the high-level plan of the company.

Start aligning all your strategies across all departments and stakeholders using Roadmunk’s Master Roadmapping features. Give it a try here .

Ideally, a good roadmap should effectively communicate the following strategic pieces:

- Strategic alignment : Why (and how) the initiatives align with the higher-level business goals or product/business strategy

- Resources : How a team will achieve those goals (OKRs, for example) and what resources are required to achieve them

- Time estimates : When any important deliverables are due (and with the right roadmapping tool, you have the flexibility to define dates according to your delivery needs.

- Dependencies with other teams : The teams and team members that need to be involved and why

One of the most popular types of roadmaps is the product roadmap, and they’re instrumental to product management (it’s why we have an entire library of resources for product managers ). Product roadmaps provide a crystal clear way for product teams to visualize how their product will evolve over time. Because a product roadmap is a visual plan, it plays really well in a presentation — making it a great tool for PMs to align all stakeholders on their one high-level product strategy.

Non-product teams have started to catch on to how they can use roadmaps to improve strategic communication and win executive buy-in for those plans. More and more marketing, IT and project-based teams are visualizing their strategies with roadmaps.

What can roadmaps help you achieve?

- Consensus and alignment . Roadmaps can create the transparent consensus needed to move forward with decision-making around strategy (from the high level business goals to the granular day-to-day tasks and projects)

- Better communication . Roadmapping promotes and improves communication across teams and departments by creating an ongoing dialogue around strategy and goals.

- A more visual way of seeing a plan . The visual aspect of roadmaps makes it easy to communicate outputs, timelines, projects and initiatives across an organization.

- Breaking team silos . Roadmaps can be the key in creating alignment between resource allocation and a company’s goals, and between the technical side of the company (product, development, engineering) and the business.

In this guide, you’ll find the roadmapping basics you need — best practices that are applicable to all types of roadmapping teams — like how to create your first visual roadmap, what it should include and examples of beautiful roadmaps to inspire you.

What should a roadmap include?

How to create a roadmap and what to include in it really depends on the type of roadmap you’re creating. But generally speaking, there’s a set of essential elements and qualities that apply to all roadmaps.

It has to be flexible . Strategy-setting can get complex, ambiguous and uncertain—so you need the most flexible roadmapping tool that can adapt to that reality.

It has to be collaborative . What’s the best way to gain buy-in and alignment on a plan? Involve your stakeholders early in the roadmap planning process, listen to their objections and concerns and be curious about their reasoning for why some things should be prioritized over others. Learn how to say no, but also take the time to listen and understand where your teammates are coming from when it comes to prioritizing their work.

It has to be visually beautiful . Good design elements = crystal clear communication. You want to be able to demonstrate to your stakeholders that you’re on top of your strategy.

Your roadmap should also have these visual elements:

- Use color to your advantage . A good roadmap should use color to tell a story and establish relationships between the items on your roadmap. You should use color palettes to establish a visual relationship between the different categories on the roadmap.

How to create a roadmap

Here’s a high-level view of how you can get started with a roadmapping process at your organization:

1. Do an assessment of where your company stands today

How are your current efforts bringing you closer to achieving the company’s vision and business goals? Roadmaps are about setting a direction that’s focused on a number of outcomes that have been prioritized based on what needs to be done. In this case, “what needs to be done” could be centered around:

- Increasing revenue

- Expanding market reach

- Retaining current customers and making product improvements

Hopefully, the work that your teams do every day is aligned around creating an impact on those goals the company has defined at the start of the quarter, month, or year. If you find in your pre-roadmapping assessment that the work your teams are doing isn’t aligned with those goals, then those strategies need to be reworked to ensure that’s the case.

2. Determine what you want to achieve

Business goal-setting frameworks like Porter's Five Forces , SWOT analysis , or Ash Maurya's lean canvas can help you audit your goals at that high level. These frameworks are good for taking stock of your current situation, so you can identify the areas you want to focus on for any given term.

Ask yourself questions like:

- Where are your teams’ efforts best allocated? How can you prioritize resources (teams, finances, tooling) towards achieving those goals? A prioritization framework can help you gain that clarity and focus.

- Do you have a way to measure success? Are you keeping a pulse check on whether or not you’re getting close to achieving those goals (KPIs, OKRs, business metrics)?

- How are you tracking progress? Hopefully, you’re using a flexible roadmapping tool like Roadmunk that allows you to keep it updated so it demonstrates the progress of each initiative.

3. Establish how you'll achieve those goals

What are the initiatives and projects that each team is working on towards reaching the business goals? These are the elements you’ll define on your roadmap—the work you’re intending to commit to that you’ll present to your stakeholders.

What are some of the most popular roadmap formats?

The no-dates roadmap : The no-dates roadmap offers more flexibility than roadmaps built on timelines. They’re helpful for companies whose priorities are constantly shifting. This is usually the case when your business is still in its earliest stages—when you’re processing new information on a week-to-week or even day-to-day basis.

The hybrid roadmap : This type of product roadmap includes dates—but not hard dates. For example, a company might create a roadmap that is organized by month or quarter. This style of roadmap allows you to plan into the future while maintaining flexibility. Items here are plotted by month, and designated as either Current, Near-Term, or Future. By time-boxing projects according to months, you create a loose projection that’s helpful but not constraining.

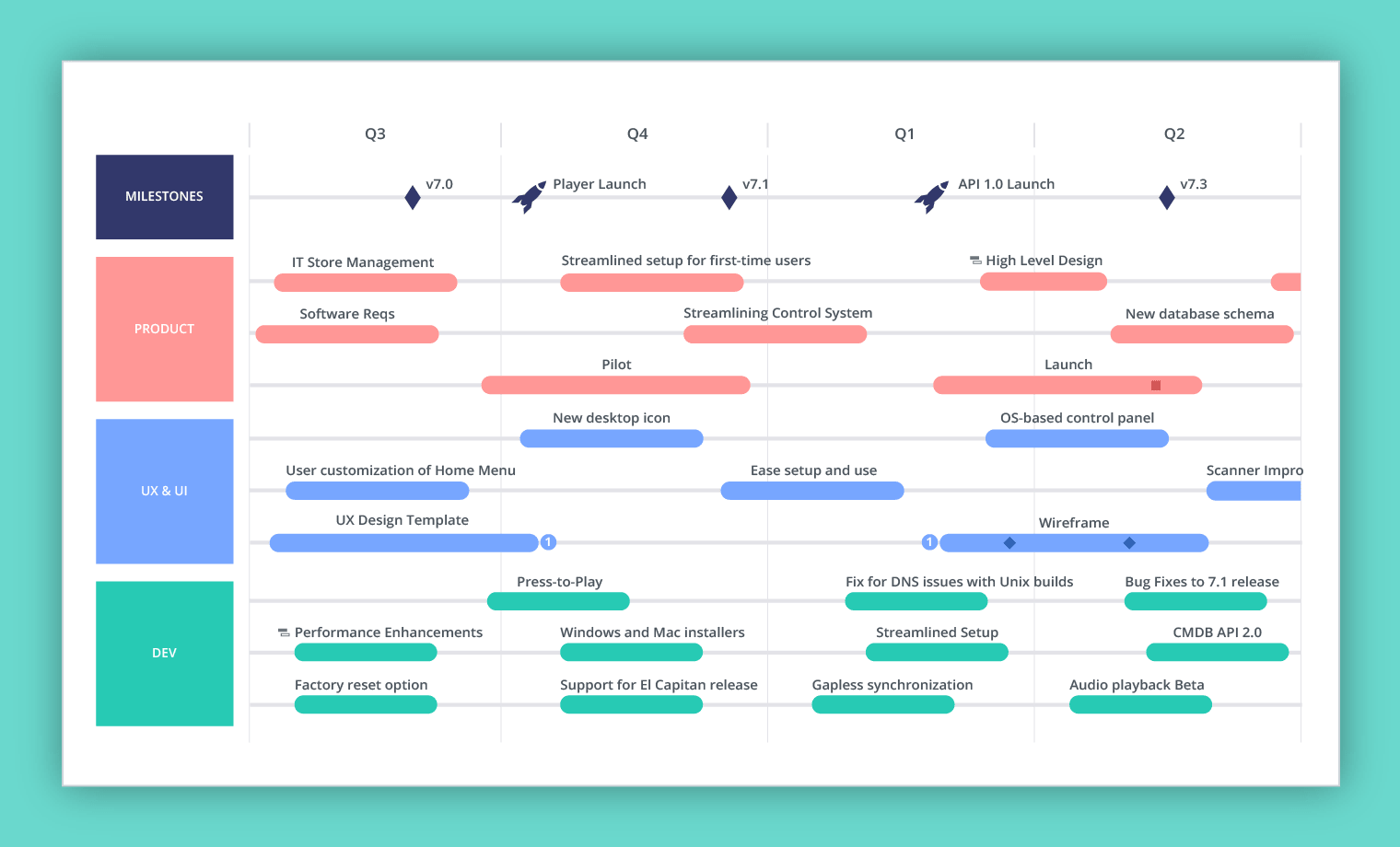

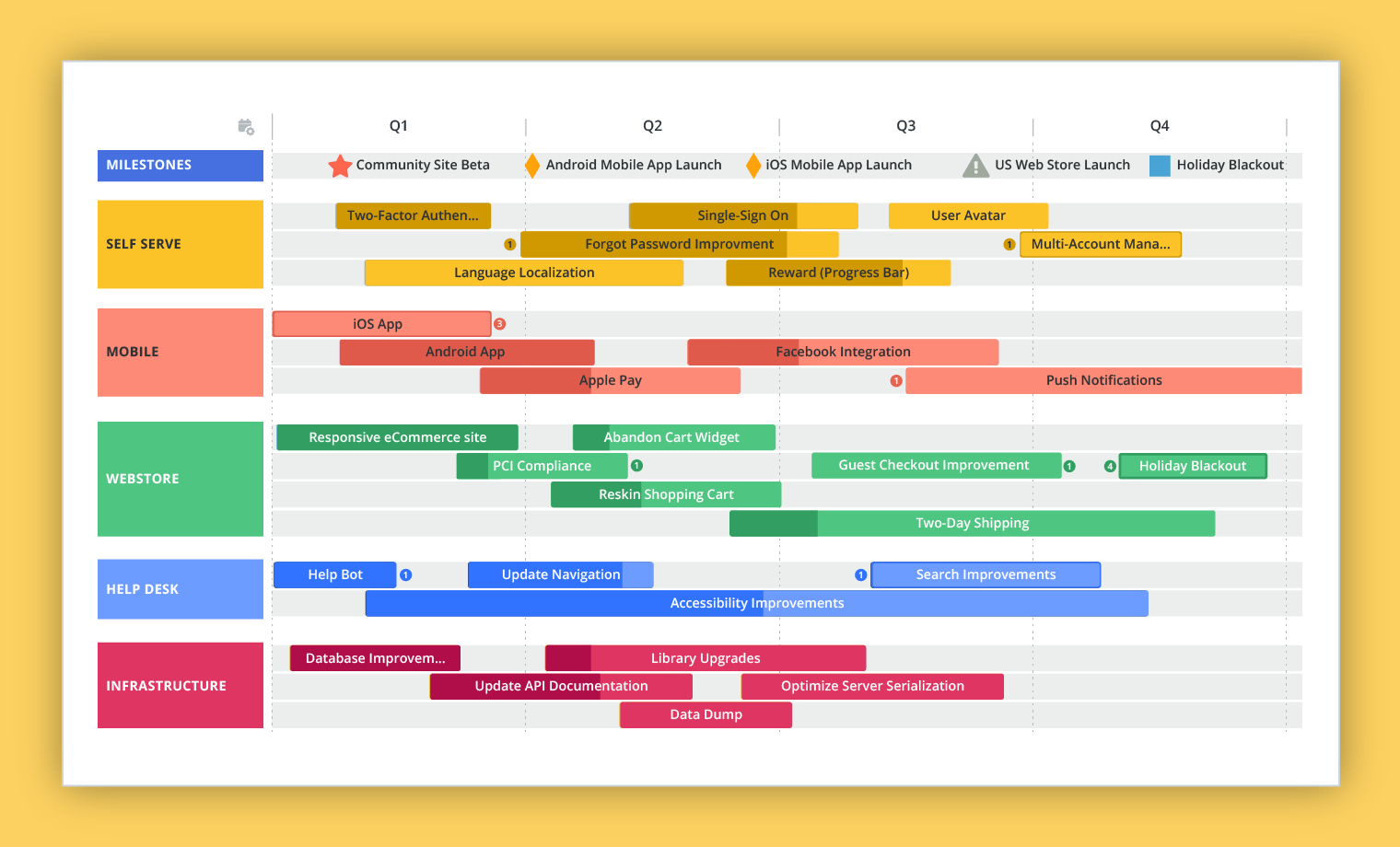

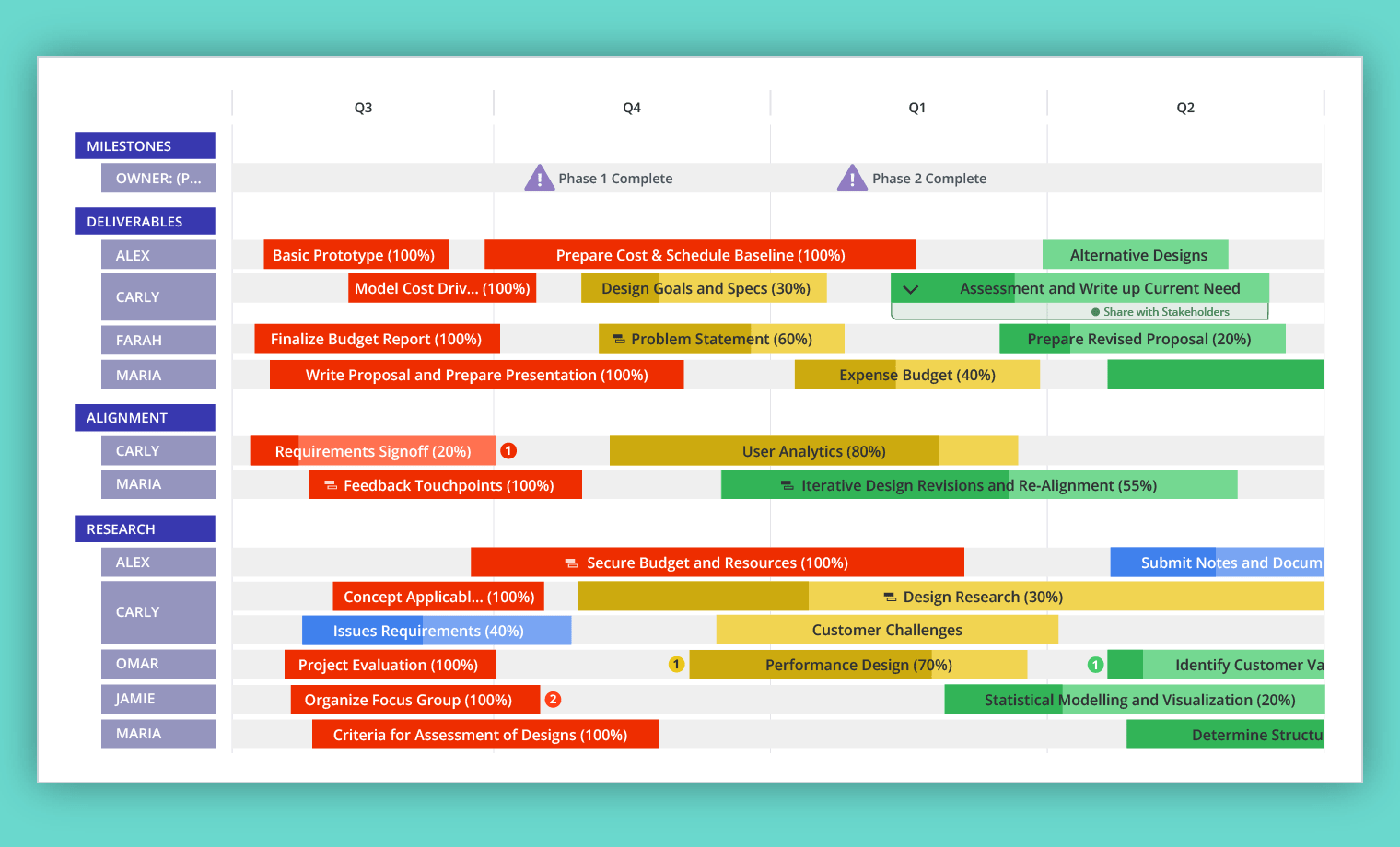

The timeline roadmap : A complex timeline roadmap really isn’t helpful or necessary until you’re juggling multiple departments, dependencies and deadlines. A timeline roadmap gives a visual structure to the many, many, many moving parts that have to work together to ensure the success of your business. They also show the product’s long-term vision—since some departments must plan a year or more in advance.

Here's a video where we go over how to create a roadmap. It's specifically about product roadmaps, but you can apply the advice to all kinds of teams and project needs:

Start using beautiful, clear roadmaps to bring your strategies to life. Sign up for a free 14-day trial of Roadmunk.

Roadmap examples.

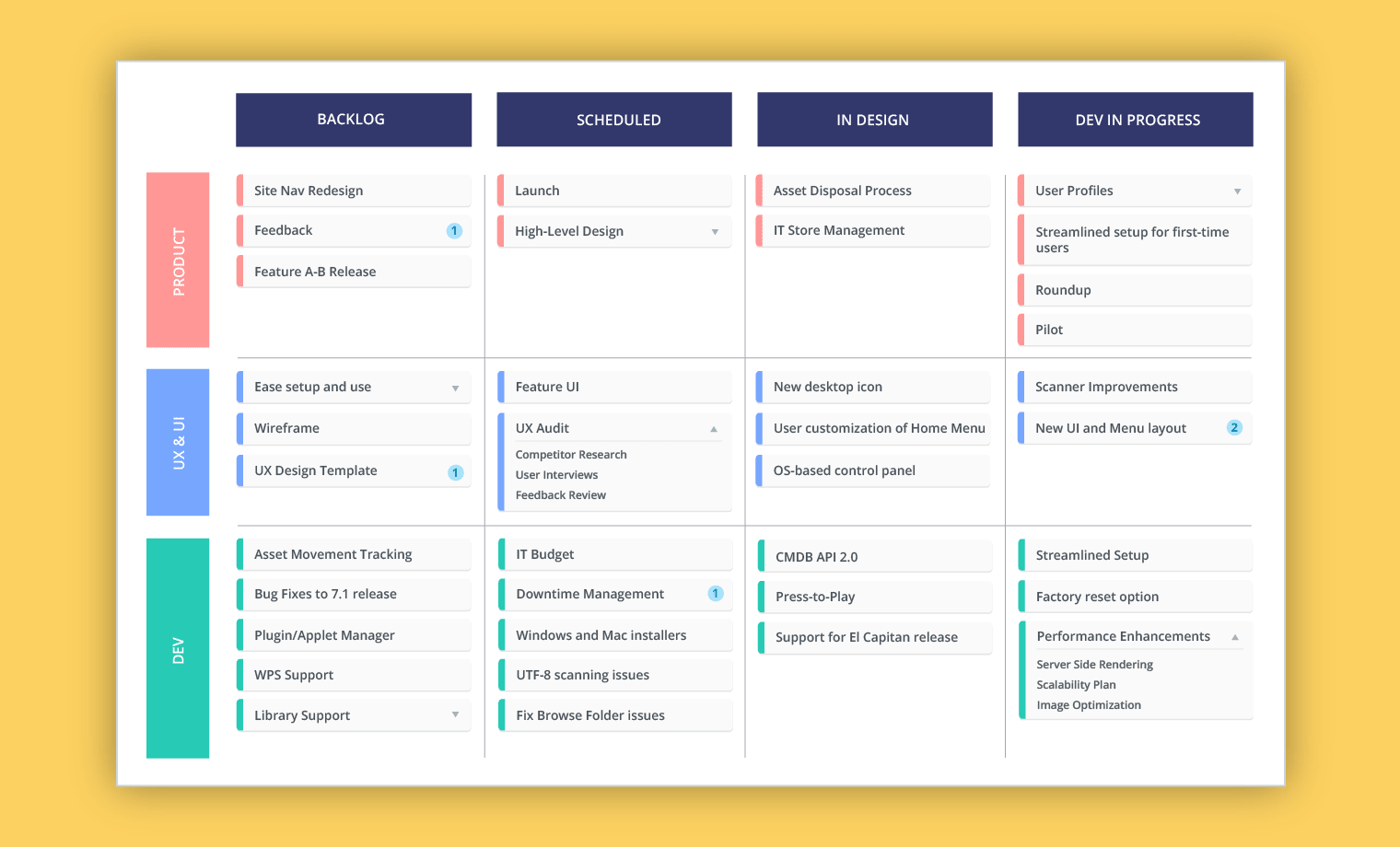

So, by now you know that a company-wide roadmapping process can help you boost visibility into each team’s goals and how they're working towards executing a high-level business strategy. Each department within your company has different needs and priorities that will translate differently onto a roadmap (we understand this, which is why we have such an extensive library of roadmap templates that span across product, technology and business use cases).

Product roadmap example

A product roadmap focuses on communicating the intent behind a product strategy. The product roadmap is the strategic communication tool in a product manager’s arsenal. Product managers work with internal teams and stakeholders to build a crystal-clear roadmap that clearly communicates deliverables and the expectations for where the product is going and why.

Ready to visualize your product strategy and shine in front of your stakeholders? Give this roadmap template a try here .

Technology roadmap example.

A technology roadmap is a powerful tool for communicating the strategy behind complex technological initiatives. It also helps create organizational alignment on what’s happening with these projects. Think of ‘technology roadmap’ as an umbrella term with various types of roadmaps falling under it, such as an IT systems roadmap, a development roadmap or a cloud strategy roadmap—just to name a few.

Uncomplicate your technological plans using a visual roadmap. Visit our template library and start using this roadmap today .

Project roadmap example.

A project roadmap offers a project manager—and their relevant stakeholders—with a high-level overview of the project’s goals, initiatives and deliverables. This can be project leads for sales, marketing, HR, or otherwise; this roadmap applies to all your business departments. Roadmaps provide a bird’s eye view of a project, so that a project manager can get all their stakeholders on the same page regarding the major components of the project like milestones and overall objectives.

Get all your project stakeholders on the same page using this roadmap template. Check out the project roadmap template .

Strategic roadmap example.

Simply put, a strategy roadmap communicates your organization’s vision. Usually championed by senior-level stakeholders, strategy roadmaps focus on mission-critical business objectives, and usually emphasize long-term timelines and deadlines. Unlike product roadmaps, which often show which features and initiatives will be executed in the short-term, strategic roadmaps illustrate the long game.

Show your stakeholders that you're on top of your strategy using this roadmap template. Start using the strategic roadmap template .

Agile roadmap example.

An agile roadmap illustrates how your product or technology will evolve—with a lot of flexibility. Unlike time-based roadmaps, which focus on dates and deadlines, agile roadmaps focus on themes and progress. We like to think of any roadmap as a “statement of intent,” because it implies that plans can and will change. Agile roadmaps emerged from this philosophy: they’re a statement of where you’re going, not a hard-and-fast plan of action and to-dos.

Keep your plans agile and flexible using the agile roadmap template .

Why roadmaps are important

A visual roadmap is a great way to communicate strategic intent. A roadmap needs to be a flexible, living document that facilitates the communication of the plan for how you’ll achieve a strategy; the deliverables, the milestones, the objectives and key results should be front and center. The best kinds of roadmaps foster team collaboration and improve the quality of your presentations.

It’s not easy to do any of those things using Microsoft Office spreadsheets and slideshow presentations. Building roadmaps using Excel and PowerPoint poses a few problems:

- Excel roadmaps can be time-consuming . Spreadsheets and presentations require a lot of manual formatting. It’s not the most intuitive or efficient way of turning a strategy into a visual: you have to manually design, populate and update each cell in a spreadsheet using raw data.

- Microsoft Office roadmaps are visually limited . Unless you’re a PowerPoint or Excel expert who can whip out beautiful visuals in no time, these tools require that you build everything from scratch: the visual design, the color palettes, the elements that depict milestones, key dates and dependencies, etc.