RACE Writing: A Comprehensive Guide + Examples

Welcome to the ultimate guide on mastering the RACE writing method.

Whether you’re a student aiming to ace your essays, a teacher looking to boost your students’ writing skills, or simply someone who wants to write more clearly and effectively, this guide is for you. Let’s transform your writing together,

What Is RACE Writing?

Table of Contents

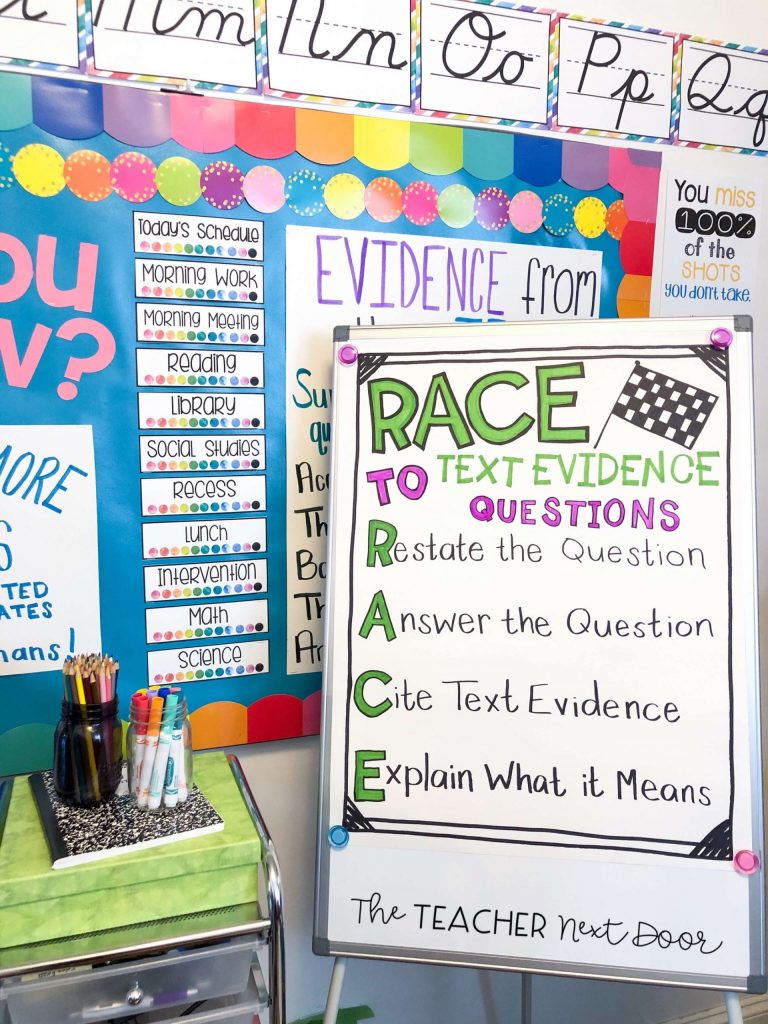

RACE is an acronym that stands for Restate, Answer, Cite, and Explain .

This structured approach ensures that responses are clear, complete, and well-supported by evidence.

Here’s a quick overview of what each component entails:

- Restate : Begin by restating the question or prompt to establish the context of your response.

- Answer : Directly answer the question or address the prompt.

- Cite : Provide evidence or examples to support your answer.

- Explain : Elaborate on the evidence and its relevance to your answer.

Now, let’s dive deeper into each component of the RACE strategy and see how to apply it effectively.

Restate: Setting the Context

Restating the question or prompt is the first step in the RACE strategy. This ensures that the reader knows exactly what question you are addressing. It also helps you stay focused on the topic.

Tips for Restating

- Paraphrase the Question : Don’t just repeat the question verbatim. Rephrase it in your own words.

- Keep it Brief : Your restatement should be concise and to the point.

- Include Key Terms : Make sure to use key terms from the question to maintain clarity.

Question : How does the protagonist in “To Kill a Mockingbird” demonstrate courage? Restatement : The protagonist in “To Kill a Mockingbird” demonstrates courage through various actions and decisions.

Answer: Direct and Clear Responses

Once you’ve restated the question, the next step is to answer it directly. This is your main response to the question or prompt.

Tips for Answering

- Be Direct : Clearly state your answer without beating around the bush.

- S tay Focused: Make sure your answer directly tackles the question at hand.

- Keep it Simple : Use straightforward language to convey your point.

Answer : The protagonist, Scout Finch, demonstrates courage by standing up for what she believes is right, despite the risks involved.

Cite: Supporting with Evidence

Citing evidence is crucial for backing up your answer. This involves providing quotes, data, or examples that support your response.

Tips for Citing

- Use Reliable Sources : Ensure your evidence comes from credible and relevant sources.

- Integrate Smoothly : Blend your citations into your writing seamlessly.

- Be Specific : Provide detailed and specific evidence.

Citation : For instance, in the novel, Scout stands up to a mob intent on lynching Tom Robinson, demonstrating her bravery (Lee, 1960, p. 153).

Explain: Making the Connection

The final step is to explain how your evidence supports your answer. This is where you connect the dots and show the significance of your evidence.

Tips for Explaining

- Be Thorough : Provide a detailed explanation of how the evidence supports your answer.

- Clarify Relevance : Clearly show the link between your evidence and your response.

- Avoid Assumptions : Don’t assume the reader will understand the connection without your explanation.

Explanation : This act of defiance highlights Scout’s moral courage, as she is willing to face danger to uphold justice and protect the innocent.

Watch this playlist of videos on RACE Writing:

Using RACE Writing for Yourself

Implementing the RACE strategy in your writing can significantly enhance the quality and coherence of your work.

Here are some practical steps to integrate RACE into your writing process:

1. Understand the Prompt

Before you start writing, make sure you fully understand the question or prompt.

This will help you accurately restate it in your response.

Spend time analyzing the prompt to grasp its nuances and underlying questions. This thorough understanding allows you to pinpoint exactly what is being asked, ensuring that your response remains relevant and focused.

Misinterpreting the prompt can lead to an off-topic answer, wasting both your time and effort.

Additionally, breaking down the prompt into smaller, manageable parts can be beneficial.

Identify the key terms and phrases, and consider their implications.

By doing this, you can create a mental map of your response, making it easier to restate the prompt effectively in your own words.

This step sets a strong foundation for the rest of the RACE process.

2. Outline Your Response

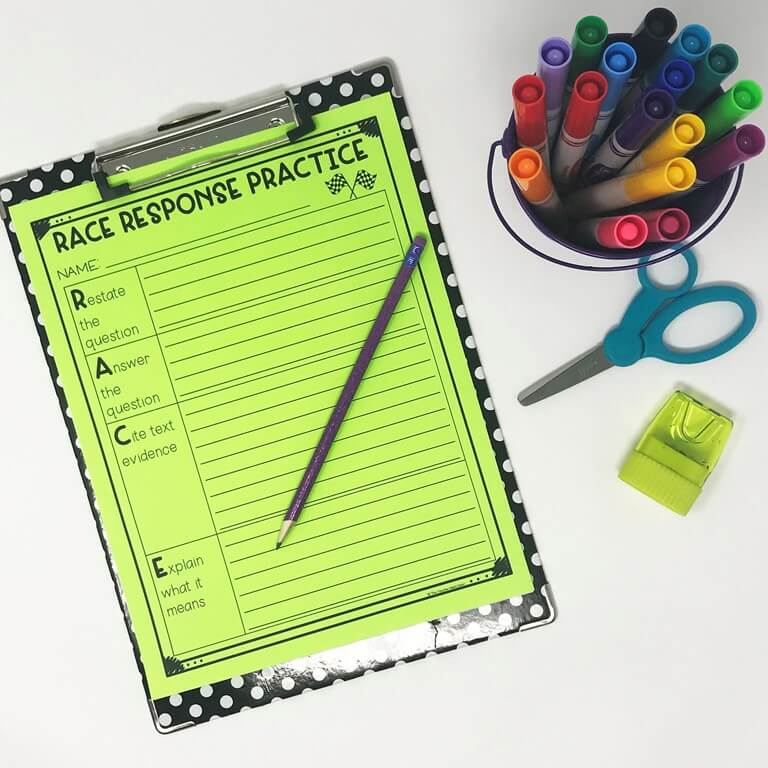

Create a brief outline using the RACE components.

This will help you organize your thoughts and ensure that you address each part of the strategy.

Start with your restatement, then outline your direct answer, list the evidence you will cite, and plan your explanations.

An outline serves as a roadmap, guiding you through your writing process and helping you stay on track.

An organized outline not only saves time but also enhances the coherence of your response.

It allows you to see the overall structure and flow of your argument, making it easier to identify any gaps or weaknesses.

This proactive approach helps you craft a well-rounded and compelling response, ensuring that each RACE component is effectively addressed.

3. Draft and Revise

Write a draft of your response, focusing on incorporating each element of RACE.

Afterward, revise your work to refine your restatement, answer, citations, and explanations.

Drafting allows you to put your ideas into words without worrying too much about perfection.

It’s an opportunity to explore your thoughts and see how well they translate onto the page.

Revising, on the other hand, is where the real magic happens.

Take a critical look at your draft, checking for clarity, coherence, and consistency.

Ensure that your restatement is accurate, your answer is direct, your citations are relevant, and your explanations are thorough.

This iterative process of drafting and revising helps you produce a polished and effective piece of writing.

4. Practice Regularly

Like any skill, mastering RACE takes practice.

Regularly applying the strategy in various writing contexts will help you become more proficient.

The more you practice, the more intuitive the process will become, allowing you to apply the RACE strategy effortlessly.

Experiment with different types of writing prompts and questions.

This diversity in practice will help you adapt the RACE strategy to different contexts and topics, making you a more versatile writer.

Regular practice also builds confidence, enabling you to tackle any writing task with ease and assurance.

Teaching RACE Writing to Students

As an educator, teaching the RACE writing strategy to students can significantly improve their writing abilities.

Here are some tips for effectively teaching RACE:

1. Introduce the Strategy

Start by explaining the RACE acronym and its components.

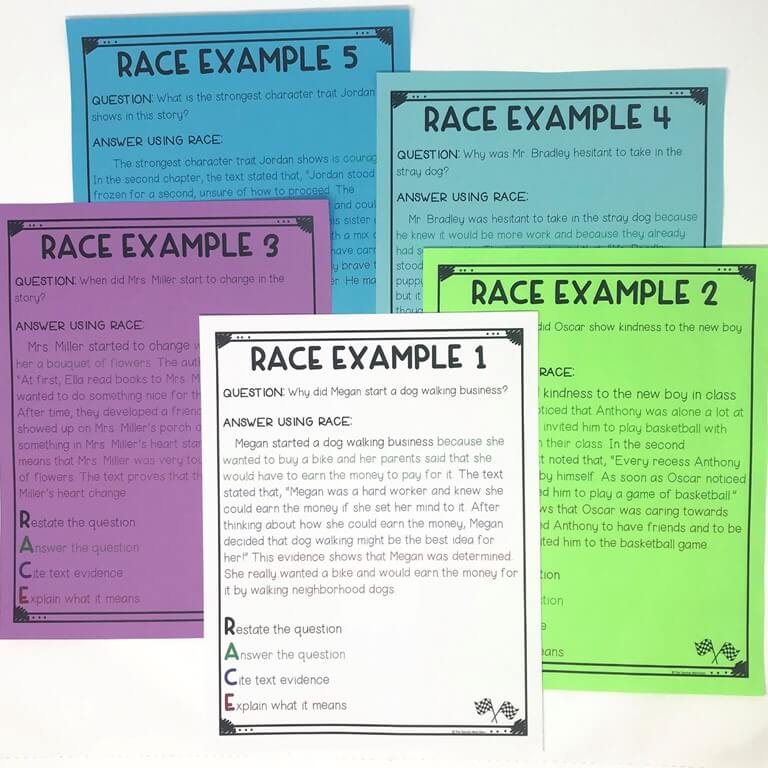

Use examples to illustrate each part of the strategy. Providing a clear and thorough introduction helps students understand the purpose and benefits of the RACE strategy.

Use engaging examples that are relevant to their interests to capture their attention and make the concept more relatable.

In addition, consider using visual aids such as charts or diagrams to break down the RACE components.

Visual representations can make it easier for students to grasp the structure and flow of the strategy.

Reinforce your explanation with real-life examples from texts they are familiar with, demonstrating how RACE can be applied in various contexts.

2. Model the Process

Demonstrate how to apply the RACE strategy by working through an example together with your students.

Show them how to restate, answer, cite, and explain cohesively.

Modeling the process provides students with a concrete example of how to effectively use RACE in their writing.

It also allows them to see the strategy in action, making it more accessible and understandable.

During the modeling process, think aloud to explain your reasoning and decision-making.

This helps students understand the thought process behind each step of the RACE strategy.

Encourage questions and provide immediate feedback to clarify any doubts. By actively engaging students in the modeling process, you foster a deeper understanding and appreciation of the strategy.

3. Practice with Guidance

Provide students with practice prompts and guide them through the RACE process.

Offer feedback to help them improve their responses.

Guided practice allows students to apply the RACE strategy in a supportive environment, where they can receive constructive feedback and make necessary adjustments.

Start with simpler prompts and gradually increase the complexity as students become more comfortable with the strategy.

Pair students up for peer practice sessions, where they can collaborate and learn from each other.

As they practice, circulate around the classroom to provide individualized feedback and address any challenges they may face.

This hands-on approach helps reinforce the RACE strategy and builds students’ confidence in their writing abilities.

4. Encourage Peer Review

Have students review each other’s work using the RACE strategy.

This peer review process can provide valuable insights and help reinforce their understanding.

Peer review fosters a collaborative learning environment, where students can share their perspectives and learn from each other.

Provide clear guidelines and criteria for peer review to ensure that the feedback is constructive and focused.

Encourage students to use the RACE framework to evaluate their peers’ responses, highlighting strengths and suggesting areas for improvement.

This process not only helps students refine their writing but also enhances their critical thinking and analytical skills.

By engaging in peer review, students gain a deeper understanding of the RACE strategy and learn to appreciate different writing styles and approaches.

5. Assess Progress

Regularly assess students’ writing to ensure they are effectively applying the RACE strategy.

Provide constructive feedback to help them continue improving.

Regular assessments allow you to track students’ progress and pinpoint areas where they might need extra help or guidance.

Use a variety of assessment methods, such as quizzes, writing assignments, and in-class exercises, to evaluate students’ understanding and application of the RACE strategy.

Provide detailed feedback that highlights both strengths and areas for improvement.

Offer specific suggestions for how they can enhance their responses.

Celebrate their successes and acknowledge their efforts to motivate and encourage continuous improvement.

By consistently assessing progress, you can ensure that students are mastering the RACE strategy and developing strong writing skills.

Examples of RACE Writing in Action

To illustrate how the RACE strategy can be effectively applied, here are three comprehensive examples.

These examples cover different contexts, showcasing the versatility of the RACE strategy in enhancing writing clarity and coherence.

Example 1: Literature Analysis

Prompt : How does the theme of friendship manifest in “Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone”?

Restate : The theme of friendship is a central element in “Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone.”

Answer : Friendship is portrayed through the strong bond between Harry, Ron, and Hermione, which helps them overcome numerous challenges.

Cite : For instance, when Ron sacrifices himself in the life-sized chess game to allow Harry and Hermione to move forward (Rowling, 1997, p. 283).

Explain : This act of selflessness exemplifies the deep trust and loyalty among the trio, highlighting how their friendship empowers them to face dangers together. Ron’s willingness to risk his life underscores the strength of their bond, illustrating the theme of friendship as a vital force in their journey.

Example 2: Scientific Report

Prompt : Explain how photosynthesis contributes to the oxygen supply on Earth.

Restate : Photosynthesis plays a crucial role in maintaining the oxygen supply on Earth.

Answer : During photosynthesis, plants convert carbon dioxide and water into glucose and oxygen, releasing oxygen as a byproduct.

Cite : According to Smith (2020), “Plants release approximately 260 billion tons of oxygen into the atmosphere each year through the process of photosynthesis” (p. 45).

Explain : This process is fundamental to sustaining life on Earth, as it replenishes the oxygen that animals and humans breathe. Without photosynthesis, the oxygen levels in the atmosphere would diminish, leading to a decline in aerobic organisms. Therefore, photosynthesis is essential for maintaining the balance of gases in our atmosphere and supporting life.

Example 3: Historical Analysis

Prompt : Discuss the impact of the Industrial Revolution on urbanization in the 19th century.

Restate : The Industrial Revolution significantly influenced urbanization in the 19th century.

Answer : The rapid industrialization led to a massive migration of people from rural areas to cities in search of employment opportunities.

Cite : Historical records indicate that the urban population in England increased from 20% to 50% between 1800 and 1850 due to industrialization (Johnson, 2015, p. 102).

Explain : This shift transformed the social and economic fabric of society, as cities grew rapidly to accommodate the influx of workers. The development of factories and the need for labor created new urban centers, leading to improved infrastructure and changes in living conditions. However, this rapid urbanization also brought challenges, such as overcrowding and poor sanitation, highlighting the complex impact of the Industrial Revolution on society.

Final Thoughts: RACE Writing

Mastering the RACE writing strategy enhances clarity, coherence, and persuasiveness in writing.

By Restating, Answering, Citing, and Explaining, you can effectively address any prompt.

Embrace RACE to elevate your writing skills and produce compelling responses.

Related Posts

- Oreo Opinion Writing [Tips, Guide, & Examples]

- Writing Rubrics [Examples, Best Practices, & Free Templates]

- How to Write a Paragraph [Ultimate Guide + Examples]

- Narrative Writing Graphic Organizer [Guide + Free Templates]

- How to Write a Haiku [40 Tips & Examples]

Race & Ethnicity—Definition and Differences [+48 Race Essay Topics]

Race and ethnicity are among the features that make people different. Unlike character traits, attitudes, and habits, race and ethnicity can’t be changed or chosen. It fully depends on the ancestry.

But why do we separate these two concepts and what are their core differences? How do people classify different races and types of ethnicity?

To find answers to these questions, keep reading the article.

Also, if you have a writing assignment on the same topic due soon and looking for inspiration, you’ll find plenty of race, racism, and ethnic group essay examples. At IvyPanda , we’ve gathered over 45 samples to help you with your writing, so you don’t have to torture yourself looking for awesome essay ideas.

Race and Ethnicity Definitions

It’s important to learn what race and ethnicity really are before trying to compare them and explore their classification.

Race is a group of people that belong to the same distinct category based on their physical and social qualities.

At the very beginning of the term usage, it only referred to people speaking a common language. Later, the term started to denote certain national affiliations. A reference to physical traits was added to the term race in the 17th century.

In a modern world, race is considered to be a social construct. In other words, it’s a distinguishable identity with a cultural meaning behind. Race is not usually seen as exclusively biological or physical quality, even though it’s partially based on common physical features among group members.

Ethnicity (also known as ethnic group) is a category of people who have similarities like common language, ancestry, history, culture, society, and nation.

Basically, people inherit ethnicity depending on the society they live in. Other factors that define a person’s ethnicity include symbolic systems like religion, cuisine, art, dressing style, and even physical appearance.

Sometimes, the term ethnicity is used as a synonym to people or nation. It’s also fair to mention that it’s sometimes possible for an individual to leave one ethnic group and shift to another. It’s usually done through acculturation, language shift, or religious conversion.

Though, most of the times, representatives of a certain ethnic group continue to speak their common language and share some other typical traits even if derived from their founder population.

Differences Between Race and Ethnicity

Now that we know what race and ethnicity are all about, let’s highlight some of the major differences between these two terms.

- It divides people into groups or populations based mainly on physical appearance

- The main accent is on genetic or biological traits

- Because of geographical isolation, racial categories were a result of a shared genealogy. In modern world, this isolation is practically nonexistent, which lead to mixing of races

- The distinguishing factors can include type of face or skin color. Other genetic differences are considered to be weak

- Members of an ethnic group identify themselves based on nationality, culture, and traditions

- The emphasis is on group history, culture, and sometimes on religion and language

- Definition of ethnicity is based on shared genealogy. It can be either actual or presumed

- Distinguishing factors of ethnic groups keep changing depending on time period. Sometimes, they get defined by stereotypes that dominant groups have

It’s also worth mentioning that the border between two terms is quite vague . As a result, the choice of using either of them can be very subjective.

In the majority of cases, race is considered to be unitary, which means that one person belongs to one race. However, ethnically, this same person can identify themselves as a member of multiple ethnic groups. And it won’t be wrong if a person have lived enough time within those groups.

Race and Ethnicity Classification

It’s time to look at possible ways to classify racial and ethnical groups.

One of the most common classifications for race into four categories: Caucasoid, Mongoloid, Negroid, and Australoid. Three of them have subcategories.

Let’s look at them more closely.

– Caucasoid. White race with light skin color. Hair ranges from brown to black. They have medium to high structure. The subcategories are as follows:

- Alpine. Live in Central Asia

- Nordic . Baltic, British, and Scandinavian inhabitants

- Mediterranean. Hail from France, Italy, Portugal, and Spain

– Mongoloid. The race’s majority is found in Asia. Characterized by black hair, yellow skin tone, and medium height.

- Asian mongol. Found in japan, China, and East-India

- Micronesian. Inhabitants of Malenesia

– Negroid. A race found in Africa. They have black skin, wooly hair, and medium to high structure.

- Negro. African inhabitants

- Far Eastern Pygmy. Found in the south Pacific islands

- Bushman and Hottentot. Live in Kala-Hari desert of Africa

– Australoid. Found in Australia. They have wavy hair, light skin, and medium to tall height.

It’s fair to mention yet again that it’s practically impossible to find pure race representatives because of how mixed they all got.

Speaking of ethnicity classification, one of the most common ways to do that is by continent. And each of continent’s ethnic groups will have their own subcategory.

So, we can roughly divide ethnic groups into following categories:

- North American

- South American

Race Essay Ideas

If all the information above was not enough and you’re looking for race essay topics, or even straight up essay examples for your writing assignment—today’s your lucky day. Because experts at IvyPanda have gathered plenty of those.

Check out the list of race and ethnic group essay samples below. Use them for inspiration, or try to develop one of the suggested topics even further.

Whatever option you’ll choose, we’re sure that you’ll end up with great results!

- The Anatomy of Scientific Racism: Racialist Responses to Black Athletic Achievement

- Race, Ethnicity and Crime

- Representation of Race in Disney Films

- What is the relationship between Race, Poverty and Prison?

- Race in a Southern Community

- African American Women and the Struggle for Racial Equality

- American Ethnic Studies

- Institutionalized Racism from John Brown Raid to Jim Crow Laws

- The Veil and Muslim

- Race and the Body: How Culture Both Shapes and Mirrors Broader Societal Attitudes Towards Race and the Body

- Latinos and African Americans: Friends or Foes?

- Historical US Relationships with Native American

- The experiences of the Aborigines

- Contemporary Racism in Australia: the Experience of Aborigines

- No Reparations for Blacks for the Injustice of Slavery

- Racism (another variant)

- Hispanic Americans

- Racism in the Penitentiary

- How the development of my racial/ethnic identity has been impacted

- My father’s black pride

- African American Ethnic Group

- Ethnic Group Conflicts

- How the Movie Crash Presents the African Americans

- Ethnic Groups and discrimination

- Race and Ethnicity

- Racial and ethnic inequality

- Ethnic Groups and Conflicts

- Ethnics Studies

- Ethnic studies and emigration

- Ethnicity Influence

- Immigration and Ethnic Relations

- A comparison Between Asian Americans and Latinos

- Analysis of the Chinese Experience in “A Different Mirror: A History of Multicultural America” by Ronald Takaki

- Wedding in the UAE

- Social and Cultural Diversity

- The White Dilemma in South Africa

- Ethnocentrism and its Effects on Individuals, Societies, and Multinationals

- Reduction of ethnocentrism and promotion of cultural relativism

- Racial and Ethnic Groups

- Gender and Race

- Child Marriages in Modern India

- Race and Ethnicity (another variant)

- Racial Relations and Color Blindness

- Multiculturalism and “White Anxiety”

- Cultural and racial inequality in Health Care

- The impact of colonialism on cultural transformations in North and South America

- African American Studies

- Share via Facebook

- Share via X

- Share via LinkedIn

- Share via email

By clicking "Post Comment" you agree to IvyPanda’s Privacy Policy and Terms and Conditions . Your posts, along with your name, can be seen by all users.

IvyPanda uses cookies and similar technologies to enhance your experience, enabling functionalities such as:

- Basic site functions

- Ensuring secure, safe transactions

- Secure account login

- Remembering account, browser, and regional preferences

- Remembering privacy and security settings

- Analyzing site traffic and usage

- Personalized search, content, and recommendations

- Displaying relevant, targeted ads on and off IvyPanda

Please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy for detailed information.

Certain technologies we use are essential for critical functions such as security and site integrity, account authentication, security and privacy preferences, internal site usage and maintenance data, and ensuring the site operates correctly for browsing and transactions.

Cookies and similar technologies are used to enhance your experience by:

- Remembering general and regional preferences

- Personalizing content, search, recommendations, and offers

Some functions, such as personalized recommendations, account preferences, or localization, may not work correctly without these technologies. For more details, please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy .

To enable personalized advertising (such as interest-based ads), we may share your data with our marketing and advertising partners using cookies and other technologies. These partners may have their own information collected about you. Turning off the personalized advertising setting won't stop you from seeing IvyPanda ads, but it may make the ads you see less relevant or more repetitive.

Personalized advertising may be considered a "sale" or "sharing" of the information under California and other state privacy laws, and you may have the right to opt out. Turning off personalized advertising allows you to exercise your right to opt out. Learn more in IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy .

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

10.2 The Meaning of Race and Ethnicity

Learning objectives.

- Critique the biological concept of race.

- Discuss why race is a social construction.

- Discuss the advantages and disadvantages of a sense of ethnic identity.

To understand this problem further, we need to take a critical look at the very meaning of race and ethnicity in today’s society. These concepts may seem easy to define initially but are much more complex than their definitions suggest.

Let’s start first with race , which refers to a category of people who share certain inherited physical characteristics, such as skin color, facial features, and stature. A key question about race is whether it is more of a biological category or a social category. Most people think of race in biological terms, and for more than 300 years, or ever since white Europeans began colonizing populations of color elsewhere in the world, race has indeed served as the “premier source of human identity” (Smedley, 1998, p. 690).

It is certainly easy to see that people in the United States and around the world differ physically in some obvious ways. The most noticeable difference is skin tone: some groups of people have very dark skin, while others have very light skin. Other differences also exist. Some people have very curly hair, while others have very straight hair. Some have thin lips, while others have thick lips. Some groups of people tend to be relatively tall, while others tend to be relatively short. Using such physical differences as their criteria, scientists at one point identified as many as nine races: African, American Indian or Native American, Asian, Australian Aborigine, European (more commonly called “white”), Indian, Melanesian, Micronesian, and Polynesian (Smedley, 1998).

Although people certainly do differ in the many physical features that led to the development of such racial categories, anthropologists, sociologists, and many biologists question the value of these categories and thus the value of the biological concept of race (Smedley, 2007). For one thing, we often see more physical differences within a race than between races. For example, some people we call “white” (or European), such as those with Scandinavian backgrounds, have very light skins, while others, such as those from some Eastern European backgrounds, have much darker skins. In fact, some “whites” have darker skin than some “blacks,” or African Americans. Some whites have very straight hair, while others have very curly hair; some have blonde hair and blue eyes, while others have dark hair and brown eyes. Because of interracial reproduction going back to the days of slavery, African Americans also differ in the darkness of their skin and in other physical characteristics. In fact it is estimated that about 80% of African Americans have some white (i.e., European) ancestry; 50% of Mexican Americans have European or Native American ancestry; and 20% of whites have African or Native American ancestry. If clear racial differences ever existed hundreds or thousands of years ago (and many scientists doubt such differences ever existed), in today’s world these differences have become increasingly blurred.

Another reason to question the biological concept of race is that an individual or a group of individuals is often assigned to a race on arbitrary or even illogical grounds. A century ago, for example, Irish, Italians, and Eastern European Jews who left their homelands for a better life in the United States were not regarded as white once they reached the United States but rather as a different, inferior (if unnamed) race (Painter, 2010). The belief in their inferiority helped justify the harsh treatment they suffered in their new country. Today, of course, we call people from all three backgrounds white or European.

In this context, consider someone in the United States who has a white parent and a black parent. What race is this person? American society usually calls this person black or African American, and the person may adopt the same identity (as does Barack Obama, who had a white mother and African father). But where is the logic for doing so? This person, as well as President Obama, is as much white as black in terms of parental ancestry. Or consider someone with one white parent and another parent who is the child of one black parent and one white parent. This person thus has three white grandparents and one black grandparent. Even though this person’s ancestry is thus 75% white and 25% black, she or he is likely to be considered black in the United States and may well adopt this racial identity. This practice reflects the traditional “one-drop rule” in the United States that defines someone as black if she or he has at least one drop of “black blood,” and that was used in the antebellum South to keep the slave population as large as possible (Wright, 1993). Yet in many Latin American nations, this person would be considered white. In Brazil, the term black is reserved for someone with no European (white) ancestry at all. If we followed this practice in the United States, about 80% of the people we call “black” would now be called “white.” With such arbitrary designations, race is more of a social category than a biological one.

President Barack Obama had an African father and a white mother. Although his ancestry is equally black and white, Obama considers himself an African American, as do most Americans. In several Latin American nations, however, Obama would be considered white because of his white ancestry.

Steve Jurvetson – Barack Obama on the Primary – CC BY 2.0.

A third reason to question the biological concept of race comes from the field of biology itself and more specifically from the studies of genetics and human evolution. Starting with genetics, people from different races are more than 99.9% the same in their DNA (Begley, 2008). To turn that around, less than 0.1% of all the DNA in our bodies accounts for the physical differences among people that we associate with racial differences. In terms of DNA, then, people with different racial backgrounds are much, much more similar than dissimilar.

Even if we acknowledge that people differ in the physical characteristics we associate with race, modern evolutionary evidence reminds us that we are all, really, of one human race. According to evolutionary theory, the human race began thousands and thousands of years ago in sub-Saharan Africa. As people migrated around the world over the millennia, natural selection took over. It favored dark skin for people living in hot, sunny climates (i.e., near the equator), because the heavy amounts of melanin that produce dark skin protect against severe sunburn, cancer, and other problems. By the same token, natural selection favored light skin for people who migrated farther from the equator to cooler, less sunny climates, because dark skins there would have interfered with the production of vitamin D (Stone & Lurquin, 2007). Evolutionary evidence thus reinforces the common humanity of people who differ in the rather superficial ways associated with their appearances: we are one human species composed of people who happen to look different.

Race as a Social Construction

The reasons for doubting the biological basis for racial categories suggest that race is more of a social category than a biological one. Another way to say this is that race is a social construction , a concept that has no objective reality but rather is what people decide it is (Berger & Luckmann, 1963). In this view race has no real existence other than what and how people think of it.

This understanding of race is reflected in the problems, outlined earlier, in placing people with multiracial backgrounds into any one racial category. We have already mentioned the example of President Obama. As another example, the famous (and now notorious) golfer Tiger Woods was typically called an African American by the news media when he burst onto the golfing scene in the late 1990s, but in fact his ancestry is one-half Asian (divided evenly between Chinese and Thai), one-quarter white, one-eighth Native American, and only one-eighth African American (Leland & Beals, 1997).

Historical examples of attempts to place people in racial categories further underscore the social constructionism of race. In the South during the time of slavery, the skin tone of slaves lightened over the years as babies were born from the union, often in the form of rape, of slave owners and other whites with slaves. As it became difficult to tell who was “black” and who was not, many court battles over people’s racial identity occurred. People who were accused of having black ancestry would go to court to prove they were white in order to avoid enslavement or other problems (Staples, 1998). Litigation over race continued long past the days of slavery. In a relatively recent example, Susie Guillory Phipps sued the Louisiana Bureau of Vital Records in the early 1980s to change her official race to white. Phipps was descended from a slave owner and a slave and thereafter had only white ancestors. Despite this fact, she was called “black” on her birth certificate because of a state law, echoing the “one-drop rule,” that designated people as black if their ancestry was at least 1/32 black (meaning one of their great-great-great grandparents was black). Phipps had always thought of herself as white and was surprised after seeing a copy of her birth certificate to discover she was officially black because she had one black ancestor about 150 years earlier. She lost her case, and the U.S. Supreme Court later refused to review it (Omi & Winant, 1994).

Although race is a social construction, it is also true, as noted in an earlier chapter, that things perceived as real are real in their consequences. Because people do perceive race as something real, it has real consequences. Even though so little of DNA accounts for the physical differences we associate with racial differences, that low amount leads us not only to classify people into different races but to treat them differently—and, more to the point, unequally—based on their classification. Yet modern evidence shows there is little, if any, scientific basis for the racial classification that is the source of so much inequality.

Because of the problems in the meaning of race , many social scientists prefer the term ethnicity in speaking of people of color and others with distinctive cultural heritages. In this context, ethnicity refers to the shared social, cultural, and historical experiences, stemming from common national or regional backgrounds, that make subgroups of a population different from one another. Similarly, an ethnic group is a subgroup of a population with a set of shared social, cultural, and historical experiences; with relatively distinctive beliefs, values, and behaviors; and with some sense of identity of belonging to the subgroup. So conceived, the terms ethnicity and ethnic group avoid the biological connotations of the terms race and racial group and the biological differences these terms imply. At the same time, the importance we attach to ethnicity illustrates that it, too, is in many ways a social construction, and our ethnic membership thus has important consequences for how we are treated.

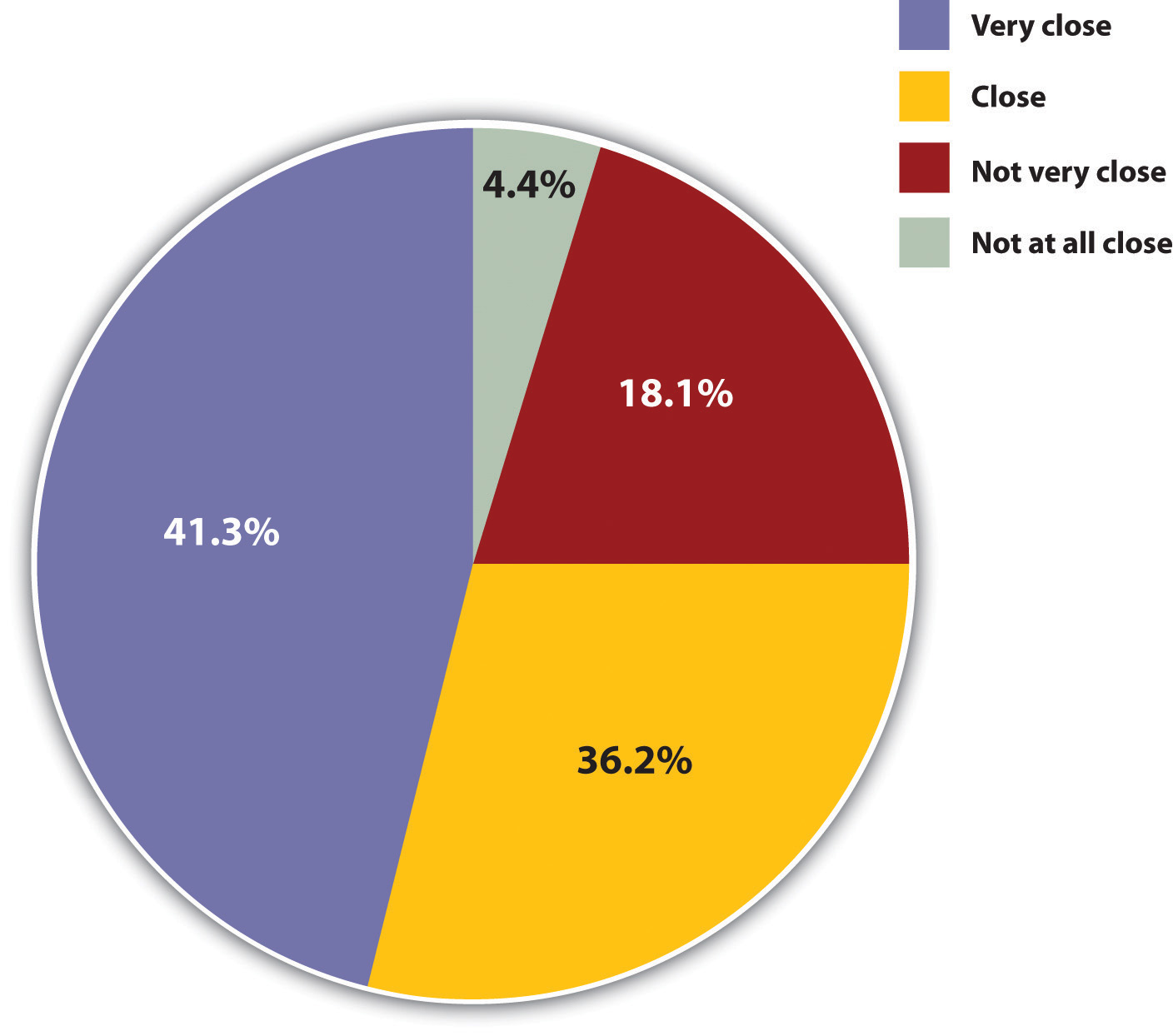

The sense of identity many people gain from belonging to an ethnic group is important for reasons both good and bad. Because, as we learned in Chapter 6 “Groups and Organizations” , one of the most important functions of groups is the identity they give us, ethnic identities can give individuals a sense of belonging and a recognition of the importance of their cultural backgrounds. This sense of belonging is illustrated in Figure 10.1 “Responses to “How Close Do You Feel to Your Ethnic or Racial Group?”” , which depicts the answers of General Social Survey respondents to the question, “How close do you feel to your ethnic or racial group?” More than three-fourths said they feel close or very close. The term ethnic pride captures the sense of self-worth that many people derive from their ethnic backgrounds. More generally, if group membership is important for many ways in which members of the group are socialized, ethnicity certainly plays an important role in the socialization of millions of people in the United States and elsewhere in the world today.

Figure 10.1 Responses to “How Close Do You Feel to Your Ethnic or Racial Group?”

Source: Data from General Social Survey, 2004.

A downside of ethnicity and ethnic group membership is the conflict they create among people of different ethnic groups. History and current practice indicate that it is easy to become prejudiced against people with different ethnicities from our own. Much of the rest of this chapter looks at the prejudice and discrimination operating today in the United States against people whose ethnicity is not white and European. Around the world today, ethnic conflict continues to rear its ugly head. The 1990s and 2000s were filled with “ethnic cleansing” and pitched battles among ethnic groups in Eastern Europe, Africa, and elsewhere. Our ethnic heritages shape us in many ways and fill many of us with pride, but they also are the source of much conflict, prejudice, and even hatred, as the hate crime story that began this chapter so sadly reminds us.

Key Takeaways

- Sociologists think race is best considered a social construction rather than a biological category.

- “Ethnicity” and “ethnic” avoid the biological connotations of “race” and “racial.”

For Your Review

- List everyone you might know whose ancestry is biracial or multiracial. What do these individuals consider themselves to be?

- List two or three examples that indicate race is a social construction rather than a biological category.

Begley, S. (2008, February 29). Race and DNA. Newsweek . Retrieved from http://www.newsweek.com/blogs/lab-notes/2008/02/29/race-and-dna.html .

Berger, P., & Luckmann, T. (1963). The social construction of reality . New York, NY: Doubleday.

Leland, J., & Beals, G. (1997, May 5). In living colors: Tiger Woods is the exception that rules. Newsweek 58–60.

Omi, M., & Winant, H. (1994). Racial formation in the United States: From the 1960s to the 1990s (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Painter, N. I. (2010). The history of white people . New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

Smedley, A. (1998). “Race” and the construction of human identity. American Anthropologist, 100 , 690–702.

Staples, B. (1998, November 13). The shifting meanings of “black” and “white,” The New York Times , p. WK14.

Stone, L., & Lurquin, P. F. (2007). Genes, culture, and human evolution: A synthesis . Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Wright, L. (1993, July 12). One drop of blood. The New Yorker, pp. 46–54.

Sociology Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Getting Real About Race Hoodies, Mascots, Model Minorities, and Other Conversations

- Stephanie M. McClure - Georgia College & State University, USA

- Cherise A. Harris - Connecticut College, USA

| Format | Published Date | ISBN | Price |

|---|

Wanted a realistic view of the academic concepts.

Stephanie M. McClure

Cherise a. harris.

Home — Essay Samples — Sociology — Ethnicity — A Report on What Race is

A Report on What Race is

- Categories: Ethnicity

About this sample

Words: 494 |

Published: Dec 12, 2018

Words: 494 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Works Cited

- Conley, D. (2017). You May Ask Yourself: An Introduction to Thinking Like a Sociologist (6th ed.). W.W. Norton & Company.

- Freund, D. (2013). Race, Ethnicity, and Power in the United States. In R. Delgado & J. Stefancic (Eds.), Critical Race Theory : An Introduction (2nd ed., pp. 97-117). NYU Press.

- Nash, M. (1964). The Golden Road: Notes on the Anthropology of Repression in California. Social Problems, 12(3), 319-330.

- Feagin, J. R., & Cobas, J. A. (2008). Latinos, Asian Americans, and the Black-White Binary. In R. Delgado & J. Stefancic (Eds.), Critical Race Theory: An Introduction (2nd ed., pp. 117-133). NYU Press.

- Bonilla-Silva, E. (2017). Racism Without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in America (5th ed.). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Omi, M., & Winant, H. (2014). Racial Formation in the United States (3rd ed.). Routledge.

- Goldberg, D. T. (2009). The Threat of Race: Reflections on Racial Neoliberalism. Wiley-Blackwell.

- DiAngelo, R. (2018). White Fragility: Why It's So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism. Beacon Press.

- Dovidio, J. F., & Gaertner, S. L. (2004). Aversive Racism. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 36, pp. 1-52). Academic Press.

- Bonilla-Silva, E. (2001). White Supremacy and Racism in the Post-Civil Rights Era. Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Karlyna PhD

Verified writer

- Expert in: Sociology

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 937 words

1 pages / 1597 words

1 pages / 863 words

1 pages / 827 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Ethnicity

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. contends "race" is not itself a natural entity, rather a synthetic construct used to degrade certain peoples. He implores society to move forward free from the shackles of categorization, liberating itself [...]

The truth of the relationship between youths, ethnicity and media representation is that there is a huge difference in the way youths and ethnicity are represented by the media in various kinds of national contexts. At [...]

In today's multicultural society, individuals often embrace various aspects of their ethnic heritage, not only as a marker of their identity but also as a way to feel connected to a larger community. This phenomenon, known as [...]

Sherman Alexie’s The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven portrays the hardships faced by Native Americans at the hands of the overpowering force of mainstream American culture. Alexie uses multiple perspectives in his [...]

Charles Dickens’ essay The Noble Savage and and H. Rider Haggard’s King Solomon’s Mines both communicate an agenda set forth by the author. In his essay, Dickens conveys his distaste for the sympathy he sees bestowed upon the [...]

Ethnocentrism can be seen most clearly in the policies of the late 1800’s. Specifically, we can see it in the boarding school system where Native Americans were forbidden to speak their own languages or wear their hair in [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Doing Race: 21 Essays for the 21st Century

A collection of new essays by an interdisciplinary team of authors that gives a comprehensive introduction to race and ethnicity. Doing Race focuses on race and ethnicity in everyday life: what they are, how they work, and why they matter. Going to school and work, renting an apartment or buying a house, watching television, voting, listening to music, reading books and newspapers, attending religious services, and going to the doctor are all everyday activities that are influenced by assumptions about who counts, whom to trust, whom to care about, whom to include, and why. Race and ethnicity are powerful precisely because they organize modern society and play a large role in fueling violence around the globe. Doing Race is targeted to undergraduates; it begins with an introductory essay and includes original essays by well-known scholars. Drawing on the latest science and scholarship, the collected essays emphasize that race and ethnicity are not things that people or groups have or are , but rather sets of actions that people do . Doing Race provides compelling evidence that we are not yet in a “post-race” world and that race and ethnicity matter for everyone. Since race and ethnicity are the products of human actions, we can do them differently. Like studying the human genome or the laws of economics, understanding race and ethnicity is a necessary part of a twenty first century education.

University of Notre Dame

Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews

- Home ›

- Reviews ›

What is Race? Four Philosophical Views

Joshua Glasgow, Sally Haslanger, Chike Jeffers, and Quayshawn Spencer, What is Race? Four Philosophical Views , Oxford University Press, 2019, 283pp., $35.00 (pbk), ISBN 9780190610180.

Reviewed by Michael O. Hardimon, University of California San Diego

In his provocative 2006 essay, “‘Race’: Normative, Not Metaphysical or Semantic,” Ron Mallon argues that much of the apparent metaphysical debate over race is an illusion. 1 There is widespread agreement that racialist race (race conceived of in essentialist and hierarchical terms) is unreal. The remaining metaphysical debate (over whether race understood in a non-racialist way is real) is mostly illusory, since the parties to the dispute operate with different understandings of the word ‘race’ and different theories of meaning. The real substantive philosophical dispute is normative; it concerns what we want our racial concepts, terms, and practices to do.

The welcome appearance of this book suggests that Mallon may have overlooked the possibility that the proper understanding of the terms is one of the points at issue in the metaphysical debate over race and that this metaphysical debate itself contains a normative dimension. The book makes clear that, in addition to being real, the metaphysical debate over race (understood as a complex dispute that includes a semantic and normative dimension) is alive and well. It brings together, in one convenient volume, the metaphysical accounts of race of four prominent philosophers of race at the cutting edge of the field.

The book divides into two parts. In part one, the authors lay out their own views. In part two, they address one another’s positions. Part one begins with Sally Haslanger’s account of race as a sociopolitical phenomenon, followed by Chike Jeffers’ cultural account. Quayshawn Spencer then presents his conception of race as a biological phenomenon. Finally, Joshua Glasgow articulates his understanding of races as visible-trait groups not legitimized by biology but which may count as real in a non-biological, non-social “basic” sense. These four positions represent four of the most important options in the metaphysics of race today. Haslanger and Jeffers offer two forms of social constructionism. Spencer represents biological realism about race. Glasgow offers an ultra-minimalist account. The discussion in the second part of the book is lively and engaging. The degree to which the four authors actually take up one another’s views is remarkable. The book is a model of philosophical discussion. Owing to limitations of space, I will concentrate on the authors’ exposition of their own views.

Haslanger approaches the question concerning what race is as a critical theorist and anti-realist about biological race. Her central purpose is to undermine the hierarchy of White Supremacy. Race for Haslanger just is sociopolitical race. Races are racialized groups, social groups that are represented as races. They are, more specifically, groups whose members are observed or imagined to exhibit bodily features thought to be evidence of ancestral links to a certain geographic region (or regions) and who occupy either subordinate or privileged social positions, depending on the bodily features they are observed or imagined to exhibit. A background ideology represents these individuals as suited to the stratified social positions they occupy, thus motivating and justifying the social hierarchy of race (pp. 25-26). This powerful account identifies one semantically permissible and politically valuable albeit non-standard use of the term ‘race’. A comprehensive specification of what-race-is must include the idea of race as a social construction. Nonetheless, Haslanger’s account needs to be supplemented in two ways.

First, Haslanger seems to think it possible fully to account for sociopolitical race without a biological concept of race. She makes use of the non-biological race-like concept of “color.” Groups whose members are observed or imagined to exhibit bodily features thought to be evidence of ancestral links to a certain geographic region (or regions) are “colors.” But the concept color is not the concept race . The background ideology to which she refers must itself deploy a biological concept of race with which to represent the sociopolitical groups it racializes as races. Racialization does not operate through the application of the benign technical concept color . It operates instead through the application of a pernicious and vacuous biological concept of race that represents social groups as biological races, endowed with “essences” or “natures” that explain why individuals are suited to the subordinate or privileged social positions they occupy. The racialist concept of race has been empirically refuted. 2 But critical theory must have this refuted concept at its disposal so that it can refer to the concept’s ideological deployment.

Second, there is reason to think that a viable practice of racialization requires the existence of groups that do in fact exhibit bodily features that are evidence of ancestral links to a certain geographic region. One of the strengths of Haslanger’s account is that it allows for the possibility of particular racialized groups that are merely imagined to have such bodily features. But if no groups exhibited bodily features of the relevant sort, could the project of racialization get off the ground? It would seem that racialization requires the existence of a number of groups that exhibit the right sort of bodily features. If everyone looked like the Dali Lama (to borrow Glasgow’s example), constructing sociopolitical races would be impossible. But groups that exhibit bodily features of the relevant sort satisfy the notion I have elsewhere dubbed the minimalist concept of race. 3 Minimalist races are defined as groups that exhibit patterns of visible physical features that correspond to geographical ancestry. What this means is that, in order for there to be sociopolitical races, minimalist races must exist. A full metaphysical account of sociopolitical race must therefore acknowledge the existence this sort of biological race. Social constructionism needs minimalist biological realism about race.

Haslanger’s account has one striking normative deficiency. As Glasgow notes, it cannot countenance the equality of races (p. 139). On her view, sociopolitical races are the only kind of race there are. Social hierarchy is a necessary feature of sociopolitical race; the end of the social hierarchy of race would mean the end of races as such. But isn’t a minimal condition of adequacy on a critical theory of race that it be able to represent racial equality as a coherent social ideal? Critical theory cannot do that unless it possesses a non-hierarchical race concept. The minimalist concept of race is such a concept; nothing in its content precludes racial equality. Indeed, there is reason to think that equality among minimalist races is what the original idea of racial equality comes to. Critical theory needs a concept like the minimalist concept of race to satisfy its own normative aspirations.

Jeffers writes as a social constructionist committed to the preservation of races. His cultural conception of race is political; it represents races as having a political origin. Races “are appearance-based groups that initially resulted from the history of Europe’s imperial encounter” (p. 65). They are characterized (a) by patterns of visible physical features that correspond to geographical ancestry (pp. 39, 40) but do not become races until (b) they are subordinated by other groups (that presumably exhibit different visible physical features) and © develop distinctive cultures in response (50). These cultures are intrinsically valuable; races should, therefore, be preserved.

Jeffers presents his account as a characterization of the metaphysics of race. This commits him to the claim that the features it ascribes to races are necessary — features a group must have in order to be a race. So, on Jeffers’ view, a group must have distinctive cultures to be a race. But is this correct? Why isn’t possession of patterns of visible physical features that correspond to geographical ancestry sufficient for racehood? Surely it is more parsimonious to define races without bringing in the notion of culture. Is it not plausible to say that a group that retained its pattern of visible physical features from t 1 to t 2 but ceased at t 2 to retain the culture it possessed at t 1 would remain the same race at t 2 ? Were Blacks to become fully assimilated to “White culture” while retaining their distinctive pattern of visible physical characteristics, they would remain Black. However abhorrent this eventuality may be, its unattractiveness does not constitute a philosophical reason for rejecting the metaphysical point.

Jeffers could abandon his metaphysical claim that groups must exhibit distinctive cultures to be races and defend the notion that the distinctive culture that races possess should be preserved as a purely normative thesis. But this presupposes, dubiously, that each race — including in particular each continental-level race — has a single distinctive culture. As Haslanger points out, “it is not clear how to define a ‘way of life’ that is shared by all Asians, or all Blacks, or all Whites, or all Native Americans” (p. 167). Without the idea that each race has a single distinctive culture, however, the idea that each race should be preserved for the sake of its distinctive culture has no punch.

It is to culture that Jeffers primarily appeals in advancing the ideal of preserving race (p. 58). But, given his specification of what-a-race-is, the preservation of race requires more than the preservation of cultures. It also requires the preservation of patterns of visible physical features. 4 But is the long-term preservation of these patterns an attractive goal? I’m not so sure. I do not think we should aim at their elimination. The notion that the only way to eliminate racism is through the literal elimination of race is deeply mistaken. And it is vitally important that members of minimalist races be able to celebrate and affirm their pattern of visible physical features. But Jeffers does not convincingly establish the claim that the long-term preservation of these patterns is something at which we should necessarily aim. It has taken philosophers a very long time to separate the idea of race from the idea of culture. We should be wary of attempts to think them together again.

Spencer approaches the metaphysics of race as a philosopher of science. His basic goal is to show that race, properly understood, is biologically real. More specifically, he wants to show that race, as understood in one specific form of ordinary US “race talk,” namely, “ OMB race talk,” has this status. OMB race talk is the racial discourse used by the US Office of Management and Budget. The meaning of ‘race’ in OMB race talk, Spencer contends, is just the set of OMB races: the set of groups to which the race terms used in OMB race talk refer {Blacks, Asians, Whites, American Indians, and Pacific Islanders} (p. 93). The set of OMB races, however, is identical to the set of “human continental populations”, i.e., {Africans, East Asians, Eurasians, Native Americans, and Oceanians} (p. 100). This latter set is a “biologically real entity” (p. 95). It counts as such because it is an epistemically useful and justified entity in a well-ordered research program in biology, namely, population genetics (p. 99), and thus is on a par with other entities that are used in empirically successful biology such as the monophyletic group, the TYRP1 gene, and the hypothalamus (p. 77). Because the set of OMB races is identical to set of human continental populations, it is a biologically real entity. This is the sense in which ‘race’ is real.

The basic idea that the races picked out by OMB race talk are biologically real is well-taken. A full account of “race” must include an account of race as a biological phenomenon. The specific claim that Pacific Islanders are a race can be doubted, since this group includes two subgroups (Melanesians and Polynesians) that exhibit different patterns of visible physical features. But this is a quibble. 5 More serious is the worry that Spencer’ account falls prey to a radical form of revisionism.

Spencer makes two main revisionary claims. The first is that is that ‘race’ as used by the OMB does not purport to refer to a kind or category (p. 93). If one thing is clear about the term ‘race’, as it is ordinarily used, it is that it purports to refer to a kind. The concept of race has generality; it reaches beyond particulars. Blacks, Asians, Whites, and so forth are putative instances of the kind. Race is the kind of which Blacks, Asians, Whites and so forth are putative instances. The set {Blacks, Asians, Whites, American Indians, and Pacific Islanders} may — as a matter of empirical fact — exhaustively specify all the races. But then again it may not. Take Hispanics. The OMB contends they are an ethnicity rather than a race. Arguments can be given for and against this claim. But if the meaning of ‘race’ just is the set {Blacks, Asians, Whites, American Indians, and Pacific Islanders}, the answer to this empirical question is settled by the term’s meaning. The fact that it isn’t, is a reason for thinking that this set cannot be the meaning of ‘race’. Another reason for thinking race is a kind is that doing so makes it possible to countenance the possibility that races other than the ones that exist now may have existed in the distant past.

Spencer’s second revisionary claim is that the sense of ‘race’ with which the OMB operates is one on which it is possible that no race is visibly distinguishable from any other (p. 93). This is revisionary because the way ‘race’ is used in American English requires that races be visibly distinguishable. It is essential not to misunderstand the visible distinguishability claim. It does not say that every race is visibly distinguishable from every other race. It allows that Blacks and Melanesians, say, might turn out to be visibly indistinguishable races. (The pattern of visible features they exhibit are very similar. Whether this similarity actually amounts to identity, however, is another matter.) The force of the visible distinguishability claim is that if R 1 is a race, there is at least one other race R 2 from which R1 is visibly distinguished.

There is no good objection to Spencer’s idea that races are ancestry groups. The problem is with his revisionary contention that they are ancestry-groups-that-may-be visibly-indistinguishable. Spencer is fully aware that his position is counterintuitive (p. 207). But the feature that makes his position counterintuitive is not its biological realism. It is its radically revisionary understanding of ‘race’. Also questionable is the decision to focus so narrowly on the OMB’s use of ‘race’ in the first place.

Glasgow’s account seeks to articulate the ordinary concept of race. The ordinary meaning of ‘race’, on his view, is something like: “Races, by definition, are relatively large groups of people who are distinguished from other groups of people by having certain visible biological traits (such as skin color) to a disproportionate extent” (p. 117). This characterization contains a very important truth but may be importantly incomplete. It leaves out the idea that races are ancestry groups that have distinctive geographical origins. This omission is no mistake. Glasgow elsewhere explicitly rejects the idea that the ordinary concept of race includes these two further conditions. 6 Can the ideas of ancestry and geographical origin be jettisoned from the ordinary concept of race?

Maybe not. The matter turns on how the “certain visible biological traits” that races are said to have to a disproportionate extent are to be specified. Some specification is needed lest men and women be counted as races. They are, after all, distinguished by certain familiar visible biological traits to a disproportionate extent. Why don’t they count as races? Glasgow uses the example of skin color to indicate the sort of visible physical traits he wants to capture. But what explains why skin color goes on the list and Adam’s apples do not? Don’t say skin color is racial and Adam’s apples are not. The question is why the one is racial and the other is not. The answer may be that the “relevant kind” of visible physical features are visible physical features that vary with geographical ancestry. What makes a visible physical feature “racial” is the fact that it is part of a pattern of visible physical features that varies in this way. The visible physical traits that Glasgow takes to fix the content of the ordinary concept of race cannot be given a full metaphysical specification without reference to the concepts of ancestry and geography. And, if this is true, these concepts cannot be jettisoned from the ordinary concept of race. Ancestry and geography are built into race ab inito.

Glasgow contends that race, as he understands it, is neither biologically nor socially real. He initially concluded that races don’t exist in any sense and opted for racial anti-realism. But then a student of his, Jonathan Woodward, asked the question, “Granted that race is not a biological or social thing, why does that mean that it couldn’t exist?” (p. 139) Reflection led to the idea they call basic racial realism: “rather than being biologically real, socially real, or illusory . . . race is real in a way that is more ‘basic’ than what science aspires to” (p. 139).

This idea faces two difficulties. One is that it provides no indication of the kind of reality that entities that exhibit basic reality are supposed to enjoy. If you maintain that something is real, it is incumbent on you to specify where it falls on the “ontological map.” To be sure, there are real things that are neither biological or social. Physical things for one. Chemical things for another. But presumably race isn’t a physical or chemical thing. So what kind of “thing” is it? The predicate ‘basicness’ does not fix a kind of thing or domain of reality. But unless we know what kind of thing race is supposed to be or to what domain of reality it is supposed to belong, we are not in a position to assess the claim that it enjoys basic reality. Basicness is presumably not a matter of metaphysical fundamentality. It would be odd to claim that race has that standing. It is just not clear what the predication of basicness to reality comes to. Nor is it clear what sort of reality “basic reality” is supposed to be.

The second difficulty is prompted by an example Glasgow gives to illustrate what it is for something to be basically real. The example is sundog. Sundogs, he contends, enjoy basic reality (p. 139). Sundogs are defined as things that are either suns or dog. Science doesn’t care about sundogs; the category plays no role in its theories. So, sundog doesn’t enjoy scientific reality. But that doesn’t mean that it enjoys no reality. There are things that are either suns or dogs. Fido is a sundog because Fido is a dog. It is therefore plausible, Glasgow claims, to say that sundogs are real. But is this inference plausible? Are we really willing to count sundog as a real entity or kind? One doesn’t have to be an “elitist” to find a metaphysics that allows the generation of a real thing by disjunctively pairing any two existing things problematic. 7 Glasgow’s “basic realism” looks like nominalism disguised as realism, the distinction being that nominalism knows that it is not realism. Glasgow’s idea of assigning a minimalist form of reality to race is welcome, but it is by no means clear that the idea of race as a “basic reality” advances the discussion.

These criticisms notwithstanding, the book provides a wonderful snapshot of the current state the metaphysics of race. It will be of interest to philosophers unfamiliar with that debate who would like to know what is going on in the field. It will also be of interest to philosophers familiar with the work of Glasgow, Haslanger, Jeffers, and Spencer who would like to see the latest presentations of their views. This volume could serve as the centerpiece of graduate seminars on race or as a text in upper-level undergraduate philosophy classes. It is a book well worth having.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks to Lucy Allais and Mary Devereaux for helpful comments.

1 Ron Mallon, 2006, ‘Race’: Normative, Not Metaphysical or Semantic," Ethics , 116 n.3, pp. 525-551.

2 Michael O. Hardimon, 2017, Rethinking Race: The Case for Deflationary Realism , Harvard University Press, pp. 12-26

3 Ibid., pp. 27-64.

4 Note, however, that Jeffers says at one point that he believes that “a future in which race is merely cultural is possible” and speaks of the “eventual achievement of a world in which races exist only as cultural groups” (p. 58).

This idea is in tension with the metaphysical status he appears to assign to patterns of visible physical features.

5 I owe this point about Polynesians to Spencer, 2015, “Philosophy of Race Meets Population Genetics,” Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences , 52, p. 50.

6 Joshua Glasgow, 2009, A Theory of Race, Routledge.

7 Joshua Glasgow, 2015, “Basic Racial Realism,” Journal of the American Philosophical Association. 1 n.3, 452.

National Museum of African American History & Culture

- Plan Your Visit

- Group Visits

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Accessibility Options

- Sweet Home Café

- Museum Store

- Museum Maps

- Our Mobile App

- Search the Collection

- Initiatives

- Museum Centers

- Publications

- Digital Resource Guide

- The Searchable Museum

- Exhibitions

- Freedmen's Bureau Search Portal

- Early Childhood

- Being Antiracist

- Community Building

- Historical Foundations of Race

Race and Racial Identity

- Social Identities and Systems of Oppression

- Why Us? Why Now?

- Digital Learning

- Strategic Partnerships

- Ways to Give

- Internships & Fellowships

- Today at the Museum

- Upcoming Events

- Ongoing Tours & Activities

- Past Events

- Host an Event at NMAAHC

- About the Museum

- The Building

- Meet Our Curators

- Founding Donors

- Corporate Leadership Councils

- NMAAHC Annual Reports

The dictionary's definition of race

Each of the major groupings into which humankind is considered (in various theories or contexts) to be divided on the basis of physical characteristics or shared ancestry.

The notion of race is a social construct designed to divide people into groups ranked as superior and inferior. The scientific consensus is that race, in this sense, has no biological basis – we are all one race, the human race. Racial identity , however, is very real. And, in a racialized society like the United States, everyone is assigned a racial identity whether they are aware of it or not.

Race as Social Construction

The dictionary’s definition of race is incomplete and misses the complexity of impact on lived experiences. It is important to acknowledge race is a social fabrication, created to classify people on the arbitrary basis of skin color and other physical features. Although race has no genetic or scientific basis, the concept of race is important and consequential. Societies use race to establish and justify systems of power, privilege, disenfranchisement, and oppression.

American Anthropological Association states that "the 'racial' worldview was invented to assign some groups to perpetual low status, while others were permitted access to privilege, power, and wealth. The tragedy in the United States has been that the policies and practices stemming from this worldview succeeded all too well in constructing unequal populations among Europeans, Native Americans, and peoples of African descent." To understand more about race as a social construct in the United States, read the AAPA statement on race and racism .

Learn more about race as it relates to human genetics In the Teaching Tolerance report, “Race Does Not Equal DNA”

What is Racial identity?

- Racial identity is externally imposed: “ How do others perceive me? ”

- Racial identity is also internally constructed: “ How do I identify myself? ”

Understanding how our identities and experiences have been shaped by race is vital. We are all awarded certain privileges and or disadvantages because of our race whether or not we are conscious of it.

Race matters. Race matters … because of persistent racial inequality in society - inequality that cannot be ignored. Justice Sonya Sotomayor United States Supreme Court

Developmental models of racial identity

Many sociologists and psychologists have identified that there are similar patterns every individual goes through when recognizing their racial identity. While these patterns help us understand the link between race and identity, creating one’s racial identity is a fluid and nonlinear process that varies for every person and group.

Think of these categories of Racial Identity Development [PDF] as stations along a journey of the continual evolution of your racial identity. Your personal experiences, family, community, workplaces, the aging process, and political and social events – all play a role in understanding our own racial identity. During this process, people move between a desire to "fit in" to dominant norms, to a questioning of one's own identity and that of others. It includes feelings of confusion and often introspection, as well as moments of celebration of self and others. You may begin at any point on this chart and move in any direction – sometimes on the same day! Recognizing the station you are in helps you understand who you are.

What is ideology?

Ideology is a system of ideas, ideals, and manner of thinking that form the basis for decision making, often regarding economic or political theory and policy

No One is Colorblind to Race

The concept of race is intimately connected to our lives and has serious implications. It operates in real and definitive ways that confer benefits and privileges to some and withholds them from others. Ignoring race means ignoring the establishment of racial hierarchies in society and the injustices these hierarchies have created and continue to reinforce.

- READ: “ Children Are Not Colorblind: How Young Children Learn Race ,” by Erin N. Winkler, Ph.D.

Understand More About the Dangers of Ignoring Race

Read this article, “ When you say you 'don't see race,' you’re ignoring racism, not helping to solve it. ”

Reflection:

• What are some experiences or identities that are central to who you are? How do you feel when they are ignored or “not seen”?

• The author in this article points out how people often use nonvisual cues to determine race. What does this reveal to us about the validity of pretending not to see race?

Either America will destroy ignorance, or ignorance will destroy the United States W.E.B. DuBois

RACISM = Racial Prejudice (Unfounded Beliefs + Irrational Fear) + Institutional Power

Racism, like smog, swirls around us and permeates American society. It can be intentional, clear and direct or it can be expressed in more subtle ways that the perpetrator might not even be aware of.

Racism is a system of advantage based on race that involves systems and institutions, not just individual mindsets and actions. The critical variable in racism is the impact (outcomes) not the intent and operates at multiple levels including individual racism, interpersonal racism, institutional racism, and structural racism.

- Interpersonal racism occurs between individuals and includes public expressions of racism, often involving slurs, biases, hateful words or actions, or exclusion.

Source: Adapted from Terry Keleher, Applied Research Center, and Racial Equity Tools by OneTILT

Breaking the Silence Silence on issues of race hurts everyone. Reluctance to directly address the impact of race can result in a lack of connection between people, a loss of our society’s potential and progress, and an escalation of fear and violence. Silence around other issues of identity can also have the same negative impact on society. Silence on race keeps us all from understanding and learning. We can break the silence by being proactive - by learning, reflecting and having courageous conversations with ourselves and others.

VIDEO: Watch below as Franchesca Ramsey discusses racism on MTV’s Decoded (warning: adult language):

Take a moment to reflect

Let's Think

- How are you thinking about your own racialized identity after learning more about race?

- Ask a friend who has a different racial identity than yours to discuss how cultivating a positive sense of racial identity about yourself and others can interrupt racism at every level (personally, socially, and institutionally)?

For concerned citizens:

- Try this exercise to recognize the everyday opportunities you may have that can promote racial equity: Exercise on Choice Points .

- Activity: Try this group activity for talking about race effectively

For Families and Educators: Here are some ways to address race and racism in your classroom:

- Teaching young children about race: a guide for families and teachers

- Tipsfor talking to children about race

Why Us, Why Now?

Subtitle here for the credits modal.

The New York Times

Advertisement

The Opinion Pages

Race and racial identity are social constructs.

Angela Onwuachi-Willig , a professor of law at the University of Iowa College of Law, is the author of "According to Our Hearts : Rhinelander v. Rhinelander and the Law of the Multiracial Family."

Updated September 6, 2016, 5:28 PM

Race is not biological. It is a social construct. There is no gene or cluster of genes common to all blacks or all whites. Were race “real” in the genetic sense, racial classifications for individuals would remain constant across boundaries. Yet, a person who could be categorized as black in the United States might be considered white in Brazil or colored in South Africa.

Unlike race and racial identity, the social, political and economic meanings of race, or rather belonging to particular racial groups, have not been fluid.

Like race, racial identity can be fluid. How one perceives her racial identity can shift with experience and time, and not simply for those who are multiracial. These shifts in racial identity can end in categories that our society, which insists on the rigidity of race, has not even yet defined.