The Nuclear Family Is Still Indispensable

Rumors of its demise have been greatly exaggerated—and it remains the stablest environment in which to raise children.

The nuclear family is disintegrating—or so Americans might conclude from what they watch and read. The quintessential nuclear family consists of a married couple raising their children. But from Oscar-winning Marriage Story ’s gut-wrenching portrayal of divorce or the Harvard sociologist Christina Cross’s New York Times op-ed in December, “The Myth of the Two-Parent Home,” discounting the importance of marriage for kids , one might draw the conclusion that marriage is more endangered than ever—and that this might not be such a bad thing.

Meanwhile, the writer David Brooks recently described the post–World War II American concept of family as a historical aberration—a departure from a much older tradition in which parents, grandparents, siblings, and cousins all look out for the well-being of children. In an article in The Atlantic bearing the headline “The Nuclear Family Was a Mistake,” Brooks argued that the “nuclear family has been crumbling in slow motion for decades.” He sees extended families and what he calls “forged families”—single parents, single adults, and others coming together to support one another and children—as filling the vacuum created by the breakdown of the nuclear family.

David Brooks: The nuclear family was a mistake

Yet the search for alternate forms of family has two major flaws. First, there’s evidence indicating that the nuclear family is, in fact, recovering. Second, a nuclear family headed by two loving married parents remains the most stable and safest environment for raising children.

There are, of course, still reasons for legitimate concern about the state of the American family. Marriage today is less likely to anchor family life in many poor and working-class communities. While a majority of college-educated men and women between 18 and 55 are married, that’s no longer true for the poor (only 26 percent are married) and the working class (39 percent). What’s more, children from these families are markedly less likely to live under the same roof as their biological parents than their peers from better-off backgrounds are.

But there is also ample good news—especially for kids.

Today, the divorce rate is down , having fallen by more than 30 percent since peaking around 1980, in the wake of the divorce revolution. And, since the Great Recession, out-of-wedlock births are now dipping as well . Less divorce and less nonmarital childbearing means that more children are being raised in stable, married families. Since 2014, the share of kids in intact families has begun to climb , reversing a decades-long trend in the opposite direction. And as Brooks noted—citing research that one of us conducted at the University of Virginia —the nuclear family headed by married parents remains a personal ideal even among men and women who harbor no moral objections to alternative family structures.

None of this suggests that scholars and social commentators are wrong to extol the role extended families can play in improving children’s lives. In her New York Times article raising questions about the importance of the two-parent home, Cross hypothesized that living closer to extended family may actually be helping protect black children “against some of the negative effects associated with parental absence from the home.” And, in Brooks’s evocative telling, the alternatives to the nuclear family hold enormous promise: “Americans are hungering to live in extended and forged families,” arrangements that “allow more adults and children to live and grow under the loving gaze of a dozen pairs of eyes, and be caught, when they fall, by a dozen pairs of arms.”

Grandparents, for example, are sharing homes with children and grandchildren; single adults and single parents are forging novel alliances on websites like CoAbode, where, according to Brooks, “single mothers can find other single mothers interested in sharing a home.” These emerging arrangements not only afford people more freedom to choose their own ties that bind, but they also promise to fill the void left in the absence of a strong nuclear family.

Read: The age of grandparents is made of many tragedies

There’s no question that “a dozen pairs of arms” can make lighter work of family life. Society should applaud those who step up to try to rescue adults and children left adrift in a nation where, despite promising trends, many children still grow up outside an intact two-parent family.

But Americans should not presume that society can successfully replace families headed by married parents with models oriented more around kith and kin. Caution is especially warranted as extended families and communities struggle to foster upward mobility or to raise the next generation successfully in circumstances where the family once anchored by marriage has broken down in their midst.

It turns out that the relationship between nuclear families and larger communities is more symbiotic than substitutionary, more interdependent than interchangeable. Whatever the merits of extended or other nonnuclear forms of family life, research has yet to show that they are entirely equipped to shoulder the unique role of a child’s two parents.

Today, most multigenerational households—which include grandparents, parents, and children—contain only one parent. This often occurs because a mother has moved in with her own parent (or the reverse) following a divorce or breakup. According to the sociologist Wendy Wang, 65 percent of multigenerational families include a single parent. But research reveals mixed outcomes for such households.

Sara McLanahan of Princeton University and Gary Sandefur of the University of Wisconsin have found that the average child raised by a “mother and grandmother is doing about the same as the average child raised by a single mother” on outcomes such as dropping out of high school or having a teen birth. And in the absence of both parents, children raised by their extended kin, such as an aunt or uncle, are significantly more likely to have, in the words of one study , “higher levels of internalizing problems”—including loneliness and sadness—compared to their peers raised by married parents. As for other emerging forms of family, such as forged families, there are well-founded reasons for skepticism about the role unrelated adults might play in raising a child. Over the years, study after study has detailed the many possible downsides to introducing unrelated adults, especially men, into children’s lives without the presence of those children’s married parents.

This is because, sadly, adults who are unrelated to children are much more likely to abuse or neglect them than their own parents are. One federal report found that children living in a household with an unrelated adult were about nine times more likely to be physically, sexually, or emotionally abused than children raised in an intact nuclear family. All this is to say that, for kids, it matters if all the pairs of arms raising them include—first and foremost—those of their own parents.

The positive effects of stable marriage and stable nuclear families also spill over. Neighborhoods, towns, and cities are more likely to flourish when they are sustained by lots of married households. The work of the Harvard sociologist Robert Sampson tells us that neighborhoods with many two-parent families are much safer. In his own words : “Family structure is one of the strongest, if not the strongest, predictor[s] of variations in urban violence across cities in the United States.”

Read: What you lose when you gain a spouse

His Harvard colleagues, the economists Raj Chetty and Nathaniel Hendren, have drawn similar conclusions about the relationship between the health of the American dream and the presence of two-parent families in a community. Working with a team of scholars, they found that black boys are more likely to achieve upward economic mobility if there are more black fathers in a neighborhood—and more married couples , as well. And for poor children of all races, Chetty and his team have found that the fraction of children with single parents in a given community is the strongest and most robust predictor of economic mobility—or its absence. Children raised in communities with high percentages of single mothers are less likely to move up. In other words, it takes a village—but of married people—to raise the odds that a poor child will have a shot at the American dream.

To be sure, the isolated nuclear family detached from all social support is simply not workable for most people. Married couples raising children—as well as other family forms—are more likely to thrive when they are embedded in strong networks of friends, family, community, and religious congregations .

Likewise, communities are stronger and safer when they include lots of committed married couples. It’s good news, then, that the share of children being raised by their own married parents is on the rise. Extended kin can (and sometimes must) play a greater role in meeting children’s needs. But as any parent knows, when it comes to an inconsolable child, even a “dozen pairs of arms” from the village don’t quite compare to the warm and safe embrace of Mom or Dad.

The Beam nuclear and social research network

The nuclear family – a reflection on core concepts

Blog 4th June 2020

Author: Petra Tjitske Kalshoven , Dalton Research Fellow, School of Social Sciences, The University of Manchester

What has been fascinating for me as an anthropologist to observe in these days of Covid-19 is how core concepts about social life are reinvented or reinforced, or invoked differently, and how these are played out in action and on-line.

In particular, I have been musing about ‘the nuclear family’, in two senses of the term: one concerns the conventional social unit of a couple and their children, widely regarded as a core building block of society; the other the togetherness that the nuclear industry, and in particular Sellafield Limited, has been promoting on-line, embracing notions of kindness, facilitating volunteering in West Cumbria, and reinforcing its devotion to mental health. The relationality implied in ‘the nuclear family’ has ideological undertones that shape current experiences of lockdown.

Sellafield Ltd moving on-line – and into the community

After worrisome news in mid-March concerning an outbreak of corona cases at Sellafield Ltd , the nuclear industry in West Cumbria (so very used to rules and regulations) responded by instructing a large part of its workforce to stay home and connect on-line, with detailed communications about this extraordinary situation conveyed in long explanations and soothing video messages. Almost every day, an update from the Sellafield Ltd / Nuclear Decommissioning Authority website is sent to subscribers containing reassurances about continuation of essential work to keep the Sellafield site safe and secure by key workers, whilst many other employees work from home, or are given the green light to spend their time volunteering.

On 4 April, Sellafield Ltd CEO Martin Chown appeared in a video expressing his thanks to stakeholders and ‘the community’ for their continuing support. The next day, the company confirmed that any employee who is not a key worker could fill out a form to ‘volunteer to support their local community during work time’ , subject to (as was clarified later) a maximum terms of 12 weeks.

Suspended activities at Sellafield Ltd have thus enhanced extension of its presence into ‘the community’. The close connections between the nuclear industry and West Cumbria that I have noticed during my fieldwork in the region, often expressed in terms of kinship relations, are reinforced and highlighted: the nuclear family becomes an extended one expanding outwards into its surrounding geography, bringing solace, support, and supplies to vulnerable people, a category that has gained special significance in these times of corona.

The company’s capability (as the management lingo goes) has been called upon to benefit West Cumbria in kind, in a move that resonates in interesting ways with calls for a new redistributive politics (but that’s a topic for another blog; see James Ferguson. 2015. Give a Man a Fish: Reflections on the New Politics of Distribution. Durham and London: Duke University Press). Suddenly, the economy (oikos + nomos, the law of the house) has taken on a different hue.

The household as a core concept

This Sellafield Ltd encouraged volunteering all happens whilst maintaining a respectful distance, of course: physical distancing underlies any engagement outside of one’s own ‘household’. Key in the UK lockdown (as in most other countries) has been the move to isolate households from one another so as to prevent the virus from propagating. Whilst the nuclear family in West Cumbria seems to have spilled out of specific physical work sites to embrace the surrounding context of its ‘community’ (a core concept in Sellafield Ltd discourse and practice), other social reconfigurations have occurred simultaneously.

When it comes to closer, in-person contact, a geographical shrinking and consolidating can be observed as a result of the household having been declared to be the primary unit, located inside the home, neatly separated from its physical surroundings. Social distancing has become the new norm. Couples and nuclear families are expected to practice physical detachment from friends and extended family. Young (and in some cases older) adults have flocked back to their parents and to a cosy (and probably more spacious) nest, recreating formerly dispersed nuclear families. In UK government statements and advice on the lockdown, most attention has gone out to vulnerable people, sometimes alone, self-isolating, and to families bogged down by the constant presence of demanding young children. Juggling home-schooling, child care, and working from home has become the standard topic of commiseration.

Less attention has been paid to singles now barred from meeting up with friends or lovers. ‘What do the government mean by ‘a household’?’ a friend fretted in the early days of lockdown, worried about a lack of companionship and intimacy, before hastily moving in with his girlfriend after years of conveniently living apart together. The mantra of social distancing privileges couples and the nuclear family, living under one roof. This has gone without saying as it seems to make sense to keep people from entering other people’s houses.

What about single households? A plea from overseas

And yet a different line of reasoning has made itself heard overseas. On 6 May, Dutch newspaper Het Parool published an op-ed piece by Linda Duits (a writer specialising in gender and sexuality), entitled ‘A plea for more flexible rules for singles: “sex is a human right”’ (my translation from this article ). Duits argues that physical contact with other people is a life necessity rather than icing on the cake. With reference to the WHO, she calls it ‘a human right’. Not having any physical contact, she writes, and being subjected to ‘enforced celibacy’ is unhealthy.

Shortly after (albeit already well into the period of confinement, as measures in the Netherlands were slowly being relaxed), the Dutch National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) showed itself receptive to this advice, stating that singles were welcome to find themselves a cuddle or a sex buddy. Reporting on this official stance in the Netherlands, The Guardian referred to a ‘typically open-minded intervention’ , whilst The Sun spoke of ‘randy Dutch’ .

RIVM’s explicit open-mindedness was short-lived, however . In a toned-down version of the advice that now eschews the term ‘sex buddy’, the institute writes: ‘Obviously, as a single you also long to have physical contact. When engaging in intimacy and sex, however, it is all the more necessary that you minimise the contamination risk. You should discuss together how this is best achieved’ (my translation from this article ). What remains of interest, is the attention paid to human needs and desires that go beyond the conventional unit of the nuclear family – resonating with what The Guardian and The Sun recognised as Dutch values, each in rather different terms.

Covid, kindness, and kin

For now, in Britain, we have to content ourselves with the new core concept of ‘kindness’. As I cycled into Whitehaven, where many Sellafield Ltd workers live, on a sunny Tuesday afternoon in late May, I was surprised at the numbers of anglers neatly spaced out on the North Pier. Men and boys, fathers and sons – more than I had ever seen out there in almost three years on the town. Perhaps they were taking a break from home, or from volunteering – or perhaps they spotted a last chance to go out on a weekday before being called back into work. On the boulevard, couples were strolling, young parents pushing buggies. Conversations were struck up, always with that odd maintaining of distance, bridged by voices louder than usual.

Slowly, the nuclear family is moving back into its Sellafield Ltd workplaces. Slowly, more of a social life will become possible again, including friends, perhaps even lovers, somehow, for better or worse. Households will spill out and mingle again. Slowly, nuclear families will rediscover some breathing room, whilst society’s relational building blocks resettle and familiar patterns click back into shape. Somewhere along the line, it was said that a human right got suspended for the greater good. Somewhere along the line, the household was taken for granted, the economy seemed poised for change, and kindness was preached, a concept rooted in ‘kin’.

In Dutch, the English equivalent of ‘kind’ would be vriendelijk (like a friend) or lief – which also means ‘beloved’ or ‘lover’. Not that anything should be read into this rashly. There will be time and space to ponder how core concepts were rooted, raised, and uprooted in the now all too ‘familiar’ world of Covid-19.

About Petra Tjitske Kalshoven Petra is a Dalton Research Fellow based in the School of Social Sciences at The University of Manchester where she was previously a Lecturer in Social Anthropology. With The Beam, she pursues her interest in human expertise and the skilled and persuasive ways in which people seek to engage specific materials and landscapes. Read more .

Petra Tjitske Kalshoven Sellafield

JEAN-MARC AUDRIN says

6th June 2020 at 10:20 am

Article intéressant et clin d’œil amusant avec ce qui se passe aux Pays-Bas ! Bravo !

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Related posts

The Power of the Special

Repetition and Sustainability

A new research project in the making: ‘Mimesis in Action’

- Dalton Nuclear Institute

- Latest posts

- Research at The University of Manchester

- Latest Posts

Reimagining the Nuclear Family

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

15.1 The Family in Cross-Cultural and Historical Perspectives

Learning objectives.

- Describe the different family arrangements that have existed throughout history.

- Understand how the family has changed in the United States since the colonial period.

- Describe why the typical family in the United States during the 1950s was historically atypical.

A family is a group of two or more people who are related by blood, marriage, adoption, or a mutual commitment and who care for one another. Defined in this way, the family is universal or nearly universal: some form of the family has existed in every society, or nearly every society, that we know about (Starbuck, 2010). Yet it is also true that many types of families have existed, and the cross-cultural and historical record indicates that these different forms of the family can all “work”: they provide practical and emotional support for their members and they socialize their children.

Types of Families and Family Arrangements

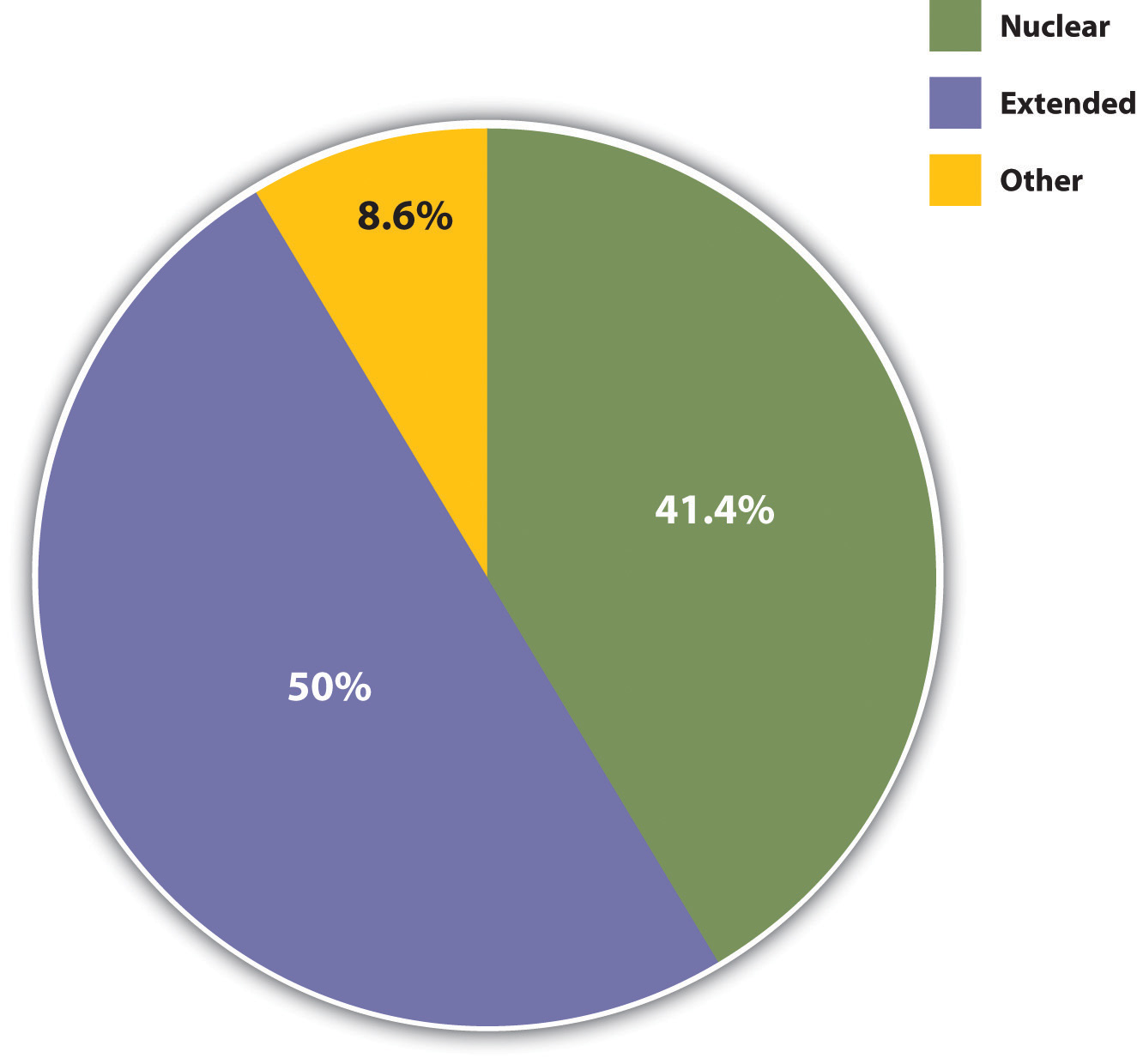

It is important to keep this last statement in mind, because Americans until recently thought of only one type of family when they thought of the family at all, and that is the nuclear family : a married heterosexual couple and their young children living by themselves under one roof. The nuclear family has existed in most societies with which scholars are familiar, and several of the other family types we will discuss stem from a nuclear family. Extended families , for example, which consist of parents, their children, and other relatives, have a nuclear family at their core and were quite common in the preindustrial societies studied by George Murdock (Murdock & White, 1969) that make up the Standard Cross-Cultural Sample (see Figure 15.1 “Types of Families in Preindustrial Societies” ).

Figure 15.1 Types of Families in Preindustrial Societies

The nuclear family that was so popular on television shows during the 1950s remains common today but is certainly less common than during that decade.

Source: Data from Standard Cross-Cultural Sample.

Similarly, many one-parent families begin as (two-parent) nuclear families that dissolve upon divorce/separation or, more rarely, the death of one of the parents. In recent decades, one-parent families have become more common in the United States because of divorce and births out of wedlock, but they were actually very common throughout most of human history because many spouses died early in life and because many babies were born out of wedlock. We return to this theme shortly.

When Americans think of the family, they also think of a monogamous family. Monogamy refers to a marriage in which one man and one woman are married only to each other. That is certainly the most common type of marriage in the United States and other Western societies, but in some societies polygamy —the marriage of one person to two or more people at a time—is more common. In the societies where polygamy has prevailed, it has been much more common for one man to have many wives ( polygyny ) than for one woman to have many husbands ( polyandry ).

The selection of spouses also differs across societies but also to some degree within societies. The United States and many other societies primarily practice endogamy , in which marriage occurs within one’s own social category or social group: people marry others of the same race, same religion, same social class, and so forth. Endogamy helps reinforce the social status of the two people marrying and to pass it on to any children they may have. Consciously or not, people tend to select spouses and mates (boyfriends or girlfriends) who resemble them not only in race, social class, and other aspects of their social backgrounds but also in appearance. As Chapter 1 “Sociology and the Sociological Perspective” pointed out, attractive people marry attractive people, ordinary-looking people marry ordinary-looking people, and those of us in between marry other in-betweeners. This tendency to choose and marry mates who resemble us in all of these ways is called homogamy .

Some societies and individuals within societies practice exogamy , in which marriage occurs across social categories or social groups. Historically exogamy has helped strengthen alliances among villages or even whole nations, when we think of the royalty of Europe, but it can also lead to difficulties. Sometimes these difficulties are humorous, and some of filmdom’s best romantic comedies involve romances between people of very different backgrounds. As Shakespeare’s great tragedy Romeo and Juliet reminds us, however, sometimes exogamous romances and marriages can provoke hostility among friends and relatives of the couple and even among complete strangers. Racial intermarriages, for example, are exogamous marriages, and in the United States they often continue to evoke strong feelings and were even illegal in some states until a 1967 Supreme Court decision ( Loving v. Virginia , 388 U.S. 1) overturned laws prohibiting them.

Families also differ in how they trace their descent and in how children inherit wealth from their parents. Bilateral descent prevails in the United States and many other Western societies: we consider ourselves related to people on both parents’ sides of the family, and our parents pass along their wealth, meager or ample, to their children. In some societies, though, descent and inheritance are patrilineal (children are thought to be related only to their father’s relatives, and wealth is passed down only to sons), while in others they are matrilineal (children are thought to be related only to their mother’s relatives, and wealth is passed down only to daughters).

Another way in which families differ is in their patterns of authority. In patriarchal families , fathers are the major authority figure in the family (just as in patriarchal societies men have power over women; see Chapter 11 “Gender and Gender Inequality” ). Patriarchal families and societies have been very common. In matriarchal families , mothers are the family’s major authority figure. Although this type of family exists on an individual basis, no known society has had matriarchal families as its primary family type. In egalitarian families , fathers and mothers share authority equally. Although this type of family has become more common in the United States and other Western societies, patriarchal families are still more common.

The Family Before Industrialization

Now that we are familiar with the basic types of family structures and patterns, let’s take a quick look at the cross-cultural and historical development of the family. We will start with the family in preindustrial times, drawing on research by anthropologists and other scholars, and then move on to the development of the family in Western societies.

People in hunting-and-gathering societies probably lived in small groups composed of two or three nuclear families. These groupings helped ensure that enough food would be found for everyone to eat. While men tended to hunt and women tended to gather food and take care of the children, both sexes’ activities were considered fairly equally important for a family’s survival. In horticultural and pastoral societies, food was more abundant, and families’ wealth depended on the size of their herds. Because men were more involved than women in herding, they acquired more authority in the family, and the family became more patriarchal than previously (Quale, 1992). Still, as Chapter 13 “Work and the Economy” indicated, the family continued to be the primary economic unit of society until industrialization.

Societies Without Nuclear Families

Although many preindustrial societies featured nuclear families, a few societies studied by anthropologists have not had them. One of these was the Nayar in southwestern India, who lacked marriage and the nuclear family. A woman would have several sexual partners during her lifetime, but any man with whom she had children had no responsibilities toward them. Despite the absence of a father, this type of family arrangement seems to have worked well for the Nayar (Fuller, 1976). Nuclear families are also mostly absent among many people in the West Indies. When a woman and man have a child, the mother takes care of the child almost entirely; the father provides for the household but usually lives elsewhere. As with the Nayar, this fatherless arrangement seems to have worked well in the parts of the West Indies where it is practiced (Smith, 1996).

A more contemporary setting in which the nuclear family is largely absent is the Israeli kibbutz , a cooperative agricultural community where all property is collectively owned. In the early years of the kibbutzim (plural of kibbutz), married couples worked for the whole kibbutz and not just for themselves. Kibbutz members would eat together and not as separate families. Children lived in dormitories from infancy on and were raised by nurses and teachers, although they were able to spend a fair amount of time with their birth parents. The children in a particular kibbutz grew up thinking of each other as siblings and thus tended to fall in love with people from outside the kibbutz (Garber-Talmon, 1972). Although the traditional family has assumed more importance in kibbutz life in recent years, extended families continue to be very important, with different generations of a particular family having daily contact (Lavee, Katz, & Ben-Dror, 2004).

These examples do not invalidate the fact that nuclear families are almost universal and important for several reasons we explore shortly. But they do indicate that the functions of the nuclear family can be achieved through other family arrangements. If that is true, perhaps the oft-cited concern over the “breakdown” of the 1950s-style nuclear family in modern America is at least somewhat undeserved. As indicated by the examples just given, children can and do thrive without two parents. To say this is meant neither to extol divorce, births out of wedlock, and fatherless families nor to minimize the problems they may involve. Rather, it is meant simply to indicate that the nuclear family is not the only viable form of family organization (Eshleman & Bulcroft, 2010).

In fact, although nuclear families remain the norm in most societies, in practice they are something of a historical rarity: many spouses used to die by their mid-40s, and many babies were born out of wedlock. In medieval Europe, for example, people died early from disease, malnutrition, and other problems. One consequence of early mortality was that many children could expect to outlive at least one of their parents and thus essentially were raised in one-parent families or in stepfamilies (Gottlieb, 1993).

The Family in the American Colonial Period

Moving quite a bit forward in history, different family types abounded in the colonial period in what later became the United States, and the nuclear family was by no means the only type. Nomadic Native American groups had relatively small nuclear families, while nonnomadic groups had larger extended families; in either type of society, though, “a much larger network of marital alliances and kin obligations [meant that]…no single family was forced to go it alone” (Coontz, 1995, p. 11). Nuclear families among African Americans slaves were very difficult to achieve, and slaves adapted by developing extended families, adopting orphans, and taking in other people not related by blood or marriage. Many European parents of colonial children died because average life expectancy was only 45 years. The one-third to one-half of children who outlived at least one of their parents lived in stepfamilies or with just their surviving parent. Mothers were so busy working the land and doing other tasks that they devoted relatively little time to child care, which instead was entrusted to older children or servants.

American Families During and After Industrialization

During industrialization, people began to move into cities to be near factories. A new division of labor emerged in many families: men worked in factories and elsewhere outside the home, while many women stayed at home to take care of children and do housework, including the production of clothing, bread, and other necessities, for which they were paid nothing (Gottlieb, 1993). For this reason, men’s incomes increased their patriarchal hold over their families. In some families, however, women continued to work outside the home. Economic necessity dictated this: because families now had to buy much of their food and other products instead of producing them themselves, the standard of living actually declined for many families.

But even when women did work outside the home, men out-earned them because of discriminatory pay scales and brought more money into the family, again reinforcing their patriarchal hold. Over time, moreover, work outside the home came to be seen primarily as men’s work, and keeping house and raising children came to be seen primarily as women’s work. As Coontz (1997, pp. 55–56) summarizes this development,

The resulting identification of masculinity with economic activities and femininity with nurturing care, now often seen as the “natural” way of organizing the nuclear family, was in fact a historical product of this 19th-century transition from an agricultural household economy to an industrial wage economy.

This marital division of labor began to change during the early 20th century. Many women entered the workforce in the 1920s because of a growing number of office jobs, and the Great Depression of the 1930s led even more women to work outside the home. During the 1940s, a shortage of men in shipyards, factories, and other workplaces because of World War II led to a national call for women to join the labor force to support the war effort and the national economy. They did so in large numbers, and many continued to work after the war ended. But as men came home from Europe and Japan, books, magazines, and newspapers exhorted women to have babies, and babies they did have: people got married at younger ages and the birth rate soared, resulting in the now famous baby boom generation . Meanwhile, divorce rates dropped. The national economy thrived as auto and other factory jobs multiplied, and many families for the first time could dream of owning their own homes. Suburbs sprang up, and many families moved to them. Many families during the 1950s did indeed fit the Leave It to Beaver model of the breadwinner-homemaker suburban nuclear family. Following the Depression of the 1930s and the war of the 1940s, the 1950s seemed an almost idyllic decade.

The Women in Military Service for America Memorial at the Arlington National Cemetery honors the service of women in the U.S. military. During World War II, many women served in the military, and many other women joined the labor force to support the war effort and the national economy.

Wally Gobetz – Virginia – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Even so, less than 60% of American children during the 1950s lived in breadwinner-homemaker nuclear families. Moreover, many lived in poverty, as the poverty rate then was almost twice as high as it is today. Teenage pregnancy rates were about twice as high as today, even if most pregnant teens were already married or decided to get married because of the pregnancy. Although not publicized back then, alcoholism and violence in families were common. Historians have found that many women in this era were unhappy with their homemaker roles, Mrs. Cleaver (Beaver’s mother) to the contrary, suffering from what Betty Friedan (1963) famously called the “feminine mystique.”

In the 1970s, the economy finally worsened. Home prices and college tuition soared much faster than family incomes, and women began to enter the labor force as much out of economic necessity as out of simple desire for fulfillment. As Chapter 13 “Work and the Economy” noted, more than 60% of married women with children under 6 years of age are now in the labor force, compared to less than 19% in 1960. Working mothers are no longer a rarity.

In sum, the cross-cultural and historical record shows that many types of families and family arrangements have existed. Two themes relevant to contemporary life emerge from our review of this record. First, although nuclear families and extended families with a nuclear core have dominated social life, many children throughout history have not lived in nuclear families because of the death of a parent, divorce, or birth out of wedlock. The few societies that have not featured nuclear families seem to have succeeded in socializing their children and in accomplishing the other functions that nuclear families serve. In the United States, the nuclear family has historically been the norm, but, again, many children have been raised in stepfamilies or by one parent.

Second, the nuclear family model popularized in the 1950s, in which the male was the breadwinner and the female the homemaker, must be considered a blip in U.S. history rather than a long-term model. At least up to the beginning of industrialization and, for many families, after industrialization, women as well as men worked to sustain the family. Breadwinner-homemaker families did increase during the 1950s and have decreased since, but their appearance during that decade was more of a historical aberration than a historical norm. As Coontz (1995, p. 11) summarized the U.S. historical record, “American families always have been diverse, and the male breadwinner-female homemaker, nuclear ideal that most people associate with ‘the’ traditional family has predominated for only a small portion of our history.” Commenting specifically on the 1950s, sociologist Arlene Skolnick (1991, pp. 51–52) similarly observed, “Far from being the last era of family normality from which current trends are a deviation, it is the family patterns of the 1950s that are deviant.”

Key Takeaways

- Although the nuclear family has been very common, several types of family arrangements have existed throughout time and from culture to culture.

- Industrialization changed the family in several ways. In particular, it increased the power that men held within their families because of the earnings they brought home from their jobs.

- The male breadwinner–female homemaker family model popularized in the 1950s must be considered a temporary blip in U.S. history rather than a long-term model.

For Your Review

- Write a brief essay in which you describe the advantages and disadvantages of the 1950s-type nuclear family in which the father works outside the home and the mother stays at home.

- The text discusses changes in the family that accompanied economic development over the centuries. How do these changes reinforce the idea that the family is a social institution?

Coontz, S. (1997). The way we really are: Coming to terms with America’s changing families . New York, NY: Basic Books.

Coontz, S. (1995, Summer). The way we weren’t: The myth and reality of the “traditional” family. National Forum: The Phi Kappa Phi Journal , 11–14.

Eshleman, J. R., & Bulcroft, R. A. (2010). The family (12th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Friedan, B. (1963). The feminine mystique . New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

Fuller, C. J. (1976). The Nayars today . Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Garber-Talmon, Y. (1972). Family and community in the kibbutz . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Gottlieb, B. (1993). The family in the Western world from the Black Death to the industrial age . New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Lavee, Y., Katz, R., & Ben-Dror, T. (2004). Parent-child relationships in childhood and adulthood and their effect on marital quality: A comparison of children who remained in close proximity to their parents and those who moved away. Marriage & Family Review, 36 (3/4), 95–113.

Murdock, G. P., & White, D. R. (1969). Standard cross-cultural sample. Ethnology, 8 , 329–369.

Quale, G. R. (1992). Families in context: A world history of population . New York, NY: Greenwood Press.

Skolnick, A. (1991). Embattled paradise: The American family in an age of uncertainty . New York, NY: Basic Books.

Smith, R. T. (1996). The matrifocal family: Power, pluralism and politics . New York, NY: Routledge.

Starbuck, G. H. (2010). Families in context (2nd ed.). Boulder, CO: Paradigm.

Sociology Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

clock This article was published more than 4 years ago

Opinion An unlikely cause of our bitterness: The nuclear family

When the history of our era is written, scholars will search for larger causes to explain its bitterness and contradictions, despite so much wealth. Was it globalization? Populism? Economic inequality? Polarization? Greed? To this list you can now add an unlikely candidate: the nuclear family.

In a powerful essay for the Atlantic — “ The Nuclear Family Was a Mistake ” — New York Times columnist David Brooks argues that the family structure we’ve held up as the cultural ideal for the past half century has been a catastrophe for many.

By “nuclear family,” he means a married mother and father and some kids. The alternative arrangement was “the extended family,” which included not only Mom, Dad and the children but also close relatives — cousins, aunts, uncles and grandparents — as well as family friends.

The great defect of the nuclear family, Brooks asserts, is that if there’s a crisis — a death, divorce, job loss, poor school grades — there’s no backup team. Children are most vulnerable to these disruptions and often are left to fend for themselves. There’s a downward spiral. “In many sectors of society,” Brooks writes, “nuclear families fragmented into single-parent families, [and] single-parent families into chaotic families or no families.”

People could increasingly go their own way. The advent of the birth-control pill encouraged people to have sex outside of marriage. Women’s entrance into the labor market made it easier for them to support themselves. Modern appliances (washing machines, dryers) made housework simpler.

As Brooks sees it, almost everyone loses under this system. The affluent can best cope with it, because they can usually afford what’s needed (day care, tutors) to support their children. Otherwise, the picture is bleak.

Children have it worst. Brooks cites an avalanche of statistics. In 1960, about 5 percent of children were born to unmarried women. Now that’s about 40 percent. In 1960, about 11 percent of children lived apart from their fathers; in 2010, the figure was 27 percent.

But adult men and women also have their share of troubles. There’s a vicious circle at work, notes Brooks: “People who grow up in disrupted families have more trouble getting the education they need to have prosperous careers. People who don’t have prosperous careers have trouble building stable families. . . . The children in those families become more isolated and more traumatized.”

Brooks says he wrote the article to stimulate experiments that aim to stabilize family life using the extended family — not the nuclear family — as the model. Granted, the problem may not be as big as Brooks imagines. Estimates by the Census Bureau and others indicate that about 60 percent of Americans live in the state where they were born. Presumably, many of these people stayed put because they valued nearby family ties.

Still, whatever the figures, there’s little doubt that reversing the breakdown of families, and its consequences, is one of the urgent tasks of social policy in the 21st century. We have been struggling unsuccessfully with it since the “ Moynihan Report ” in 1965. (Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who later became a U.S. senator, warned that the breakdown of black marriage rates would have a devastating effect on African Americans’ well-being.) The report proved highly controversial, and some branded Moynihan a racist.

But even if we could magically eliminate all considerations of class and race, it’s not clear that a workable model would emerge. The conditions needed to broach a debate over family policies strike at the heart of Americans’ political and cultural conflicts. Brooks put it this way:

“We value privacy and individual freedom too much. Our culture is oddly stuck. We want stability and rootedness, but also mobility, dynamic capitalism, and the liberty to adopt the lifestyle we choose.”

Brooks finds both liberals and conservatives unequal to the task of dealing candidly with family breakdown. “Social conservatives insist that we can bring the nuclear family back. But the conditions that made for stable nuclear families in the 1950s are never returning. Conservatives have nothing to say to the kid whose dad has split, whose mom has had three other kids with different dads; ‘go live in a nuclear family’ is really not relevant advice. . . . the majority [of households] are something else: single parents, never-married parents, blended families, grandparent-headed families.” He’s just as tough on progressives. They “still talk like self-expressive individualists of the 1970s: People should have the freedom to pick whatever family form works for them . . . . But many of the new family forms do not work well for most people.”

The larger issue is how we judge our times. We are constantly deluged with economic studies and statistics, implying that economic outcomes are the only ones that matter. The reality is that any national scorecard of well-being must take a much broader view. How well families do in preparing children for adulthood and how well they transmit important values is a much higher standard for success.

Read more from Robert Samuelson’s archive .

David Von Drehle: Politics has become the raw embodiment of joylessness

David Byler: Conservatives already won the culture war. They just don’t know it.

Catherine Rampell: Ivanka Trump claims her father’s administration is ‘pro-family.’ That’s rich.

Email: [email protected] | +233 (0) 302 851005 | +233 (0) 244 098881

- Our Secondary Sch.

Startrite Montessori School

‘nuclear family is better than the extended family' - by ama kwaa armah for a school debate.

Mr. Chairman, Well-meaning Panel of Judges, Impartial Timekeeper, Teachers, Fellow Debaters ,Students ,Ladies and Gentlemen, I deem it an honour and great pleasure done me to stand on this platform before you all to declare my posture on the subject: Nuclear family is better than the extended family.

Family, Mr. Chairman, is a group of people who are related by blood, marriage or adoption. Families can be classified into two main forms and both forms are practised in Ghana .

Mr. Chairman, in my opinion, the extended family is better than the nuclear family. Though the extended family sometimes gives rise to conflicts, interference in other people’s affairs as my opponents argued, it is the best family system that you can ever have and I am sure by the time I am done, you will all be left with no other option than to rally behind me.

Mr. Chairman, the extended family helps people to pull their resources together. That is the extended family members allow the well-to-do in the family to pull their resources in the form of money or material things to assist the poor in the family. They use their resources to undertake economic and social activities such as outdooring ceremonies, educating the brilliant but needy members, and rehabilitating the family house. What is more lovely than love and care?

Mr. Chairman, the extended family system leads to continual existence of the family. It is practically impossible and never will be possible that an extended family will die out completely. This is because the family consists of many nuclear members who give birth to replenish and sustain the family. But the nuclear family becomes threatened with collapse or extinction if family members die in a motor accident or through other causes.

Mr. Chairman there is effective socialization among members and the community. The extended family serves as an effective means of inculcating norms , values , and beliefs in the family members. The older generation pass on information and skills to the new generation and the information is passed on to the next generation. In this case everybody, is a winner! .

Mr. Chairman, Esteemed Panel of Judges , Accurate Timekeeper, Teachers ,Fellow Debaters, Students , Ladies and Gentlemen , I rest my case!

Ama Kwaa Arma ( 2014 Batch)

25,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today

Meet top uk universities from the comfort of your home, here’s your new year gift, one app for all your, study abroad needs, start your journey, track your progress, grow with the community and so much more.

Verification Code

An OTP has been sent to your registered mobile no. Please verify

Thanks for your comment !

Our team will review it before it's shown to our readers.

- School Education /

Essay on Importance of Family in 500 Words

- Updated on

- Mar 8, 2024

Essay on Importance of Family: Family always comes first; everything else is secondary. The importance of family can be seen in the fact that a family always provides us with emotional, moral, and financial support. Family members take care of each other and provide security from external and internal threats. What we learn from family forms the foundation of our personality.

The importance of family can be seen from the fact that they are our first hope. To make the entire world a better place, the Indian Prime Minister emphasized the importance of family by highlighting the Sanskrit term ‘Vasudevakutumbakam’ . It means the ‘World is one family. ’ It states that your family is not limited to those with whom you share blood; every human is connected to others in some way.

Table of Contents

- 1 Importance of Family Support

- 2 Joint and Nuclear Families

- 3.1 Conclusion

- 4 10 Lines on the Importance of Family

‘A Place Where Someone Still Thinks Of You Is A Place You Can Call Home.’ – Unknown

Importance of Family Support

Family support is crucial at every stage in life. Right from the moment we are born, family support empowers us to understand the world around us. Every moment of life requires strong family support; from joy to challenges.

Our family lays the foundation of our personality. The kind of person we become is completely determined by the family support and care we have received. A family is responsible for a child’s first educational environment. Family teaches us important values and principles. We learn about our identity and the world around us from our family. Our emotional, social, and cognitive activities are shaped by the developments taking place in our family.

Master the art of essay writing with our blog on How to Write an Essay in English .

Joint and Nuclear Families

Families are of two types; joint families and nuclear families. Joint families are large or extended nuclear families where grandparents, parents, and children live together. Sometimes nuclear families also include uncle and aunt.

Nuclear families, on the other hand, are small families, which consist of parents and children. In today’s busy world, nuclear families have become more prevalent as children step out of their houses for study and occupation purposes.

In a joint family, relationships go beyond the nuclear family unit, fostering a broader support system that withstands the test of time. Nuclear and joint families have their advantages and challenges. Whether you are living in a nuclear or joint family, both are your blood. You need to take care of your family and keep them happy.

Also Read: Essay on Family in 100, 200 & 300 Words

Family and Happiness

Spending time with family brings happiness and satisfaction. Our family’s love, support, and encouragement help enhance self-esteem and confidence to face challenges and lead a positive life. Strong family connections are important for a happier life.

Our family’s unconditional love lays the foundation for happiness. Feeling accepted and valued for who you are, regardless of successes or failures, enhances overall well-being. This love serves as a constant, supporting individuals through life’s challenges.

The importance of family can vary from person to person. Some families are sensitive towards their children while others want their children to learn from the developments around them. In both cases, families are taking care of their children. Our family is our first hope. Therefore, accepting and valuing family support is important for a successful and happy life.

Also Read: Essay on Women in Sports

10 Lines on the Importance of Family

Here are 10 lines on the importance of family. Students can add them in their essays on the importance of family or similar topics.

- Our family is our world.

- Family always comes first.

- Our family lays the foundation of our growth.

- Our family is our first hope.

- Our family provides us with emotional, moral, and financial support.

- Family support is crucial to deal with challenging situations.

- The kind of person we become is completely determined by the family support and care we have received.

- The world can become a better place if we accept the entire world as a family.

- Spending time with family brings happiness and satisfaction.

- Our family’s unconditional love lays the foundation for happiness.

Ans: The importance of family can vary from person to person. Some families are sensitive towards their children while others want their children to learn from the developments around them. In both cases, families are taking care of their children. Our family is our first hope. Therefore, accepting and valuing family support is important for a successful and happy life.

Ans: Our family is our world. Family always comes first. Our family lays the foundation of our growth. Our family is our first hope. Our family provides us with emotional, moral, and financial support. Family support is crucial to deal with challenging situations.

Ans: Our family is our first hope. They provide us with emotional, moral, and financial support in every possible situation. Taking care of our loved ones must be our priority, as it shows how much we care for them.

Related Articles

Shiva Tyagi

With an experience of over a year, I've developed a passion for writing blogs on wide range of topics. I am mostly inspired from topics related to social and environmental fields, where you come up with a positive outcome.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Contact no. *

Connect With Us

25,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today.

Resend OTP in

Need help with?

Study abroad.

UK, Canada, US & More

IELTS, GRE, GMAT & More

Scholarship, Loans & Forex

Country Preference

New Zealand

Which English test are you planning to take?

Which academic test are you planning to take.

Not Sure yet

When are you planning to take the exam?

Already booked my exam slot

Within 2 Months

Want to learn about the test

Which Degree do you wish to pursue?

When do you want to start studying abroad.

January 2024

September 2024

What is your budget to study abroad?

How would you describe this article ?

Please rate this article

We would like to hear more.

Have something on your mind?

Make your study abroad dream a reality in January 2022 with

India's Biggest Virtual University Fair

Essex Direct Admission Day

Why attend .

Don't Miss Out

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The nuclear family is disintegrating—or so Americans might conclude from what they watch and read. The quintessential nuclear family consists of a married couple raising their children. But from ...

nuclear family, in sociology and anthropology, a group of people who are united by ties of partnership and parenthood and consisting of a pair of adults and their socially recognized children.Typically, but not always, the adults in a nuclear family are married. Although such couples are most often a man and a woman, the definition of the nuclear family has expanded with the advent of same-sex ...

The Atlantic. February 21, 2020. The nuclear family is disintegrating — or so Americans might conclude from what they watch and read. The quintessential nuclear family consists of a married ...

Some advantages of a nuclear family are financial stability, strong support systems for children, and providing consistency in raising children. One disadvantage is the high cost of childcare if ...

The importance of social support for parental and child health and wellbeing is not yet sufficiently widely recognized. The widespread myth in Western contexts that the male breadwinner-female homemaker nuclear family is the 'traditional' family structure leads to a focus on mothers alone as the individuals with responsibility for child wellbeing.

Whilst the nuclear family in West Cumbria seems to have spilled out of specific physical work sites to embrace the surrounding context of its 'community' (a core concept in Sellafield Ltd discourse and practice), other social reconfigurations have occurred simultaneously. When it comes to closer, in-person contact, a geographical shrinking ...

The nuclear family has long characterized the European family. In Asia, by contrast, the extended family has been the norm. A poten-tially important difference between these family forms is the allocation of headship: vested in a child's father in the nuclear family, but in the ... The papers most closely related to ours are Foster (1993 ...

A family is bonded by love, rather than blood. In this talk, you will hear about challenges to the subiective idea of 'normality' and the traditional "nuclear family." It will demonstrate the importance of accepting blended families, and the promotion of more individualistic parenting and familiy structures.

1. The Widespread Focus on Nuclear Families 2. The Realities of Family Life: Extended Families and Gender 3. Race and Family Organizations 4. The Power of Social Class: Structure, Culture, and Families as Strategies for Survival 5. Mariage and Families 6. Social Policies and Families

The Importance Of The Nuclear Family. The nuclear family is the basic unit of a primitive society. In such families, the adult tends to be autonomous, and issues concerning a single family are often solved within that particular family (Potegal & Novaco, 2010). However, when issues involving the entire nuclear family have to be solved, some ...

The nuclear family has existed in most societies with which scholars are familiar, and several of the other family types we will discuss stem from a nuclear family. ... Although the traditional family has assumed more importance in kibbutz life in recent years, extended families continue to be very important, with different generations of a ...

An American nuclear family composed of the mother, father, and their children, c. 1955 A nuclear family (also known as an elementary family, atomic family, cereal packet family or conjugal family) is a family group consisting of parents and their children (one or more), typically living in one home residence.The alternative name, 'cereal packet family' is used in relation to the stereotypical ...

In a thought-provoking article covering an array of societal challenges, David Brooks declares that " The Nuclear Family was a Mistake .". I share many of the concerns he articulates about ...

Critical Debate On Nuclear Family Sociology Essay. There is a great deal of work within many disciplines, such as history, psychology and anthropology, on family studies, available to researchers. This undoubtedly serves to inform our awareness of the interdisciplinary, varied, and at times controversial, nature and lack of stability around the ...

It is here that the treatment of the family in The Simpsons links up with its. treatment of politics. Although the show focuses on the nuclear family, it. relates the family to larger institutions in American life, like the church, the school, and even political institutions themselves, like city government. In all.

In a powerful essay for the Atlantic — " The Nuclear Family Was a Mistake " — New York Times columnist David Brooks argues that the family structure we've held up as the cultural ideal ...

As , (Ember,1990,) said, a nuclear family is promote a family relationship. It is a family of social and economic unit that consisting minimal of one or more parents and children. Generally, a nuclear family is a family structure that it provides a stable environment for children to be raised. It leads to stable surroundings for the child to be ...

Functionalists focus too much on the significance that the family has for society and disregard the sense family life has for individual. Radical psychiatric argue against functionalism for ignoring the negative aspect of the family like domestic violence. Functionalists also ignore different types of families by focussing mainly on nuclear family.

Murdock believed that the family is the most important institution to do this. Parsons' nuclear family theory has a very positive look on the life of the family. The warm bath theory that Parsons came up with is the idea of a family man coming home from work and being greeted by a loving family where the woman takes care of the needs of the ...

A.1 A family's strength is made up of many factors. It is made of love that teaches us to love others unconditionally. Loyalty strengthens a family which makes the members be loyal to other people as well. Most importantly, acceptance and understanding strengthen a family.

But the nuclear family becomes threatened with collapse or extinction if family members die in a motor accident or through other causes. Mr. Chairman there is effective socialization among members and the community. The extended family serves as an effective means of inculcating norms , values , and beliefs in the family members.

Essay on Importance of Family in 500 Words. Essay on Importance of Family: Family always comes first; everything else is secondary. The importance of family can be seen in the fact that a family always provides us with emotional, moral, and financial support. Family members take care of each other and provide security from external and internal ...