- < Previous

Home > ACADEMIC_COMMUNITIES > Dissertations & Theses > 701

Antioch University Full-Text Dissertations & Theses

The inclusion of autism spectrum disorder in mainstream classrooms: teachers’ perspectives.

Alyssa Maiuri , Antioch New England Graduate School Follow

Alyssa Maiuri, Psy.D., is a 2021 graduate of the Psy.D. Program in Clinical Psychology at Antioch University, New England

Dissertation Committee:

- Kathi A. Borden, PhD, Committee Chair

- Deidre Brogan, PhD, Committee Member

- JMina Panayoutou-Burbridge, PsyD, Committee Member

autism spectrum disorder, inclusion, general education teachers, IPA

Document Type

Dissertation

Publication Date

This dissertation explored the unique experiences of general education teachers teaching in an inclusive classroom (which will also be referred to as a “mainstream classroom”) with a combination of students with and without autism (which will also be referred to as “autism spectrum disorder” and “ASD”). This was a qualitative research study that applied the Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) research method, as presented by Smith, Flowers, and Larkin (2009). The participants in this study were seven general education teachers, each of whom taught kindergarten or fourth grade. Purposive sampling was used to gain a better understanding of the teachers’ experiences across the elementary school careers of students with autism. Four teachers taught in Massachusetts, two in New Jersey, and one in New York City. Out of the seven participants, three were kindergarten teachers and the remaining four were fourth-grade teachers. Through semi-structured interviews, participants’ experiences were shared. The data analysis involved generating emergent and superordinate themes of teacher perceptions to aid in the understanding of the teachers’ experiences. This study explored whether these experiences differed across grade levels and geographic locations, and how they compared across the full data set. Finally, the findings were discussed in the context of previous literature, what the limitations were to this study, what future directions there were for research on this topic, and my personal reflection.

Alyssa Maiuri

ORCID Scholar ID# 0000-0003-4620-735X

Recommended Citation

Maiuri, A. (2021). The Inclusion of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Mainstream Classrooms: Teachers’ Perspectives. https://aura.antioch.edu/etds/701

Since April 19, 2021

Included in

Clinical Psychology Commons

Antioch University Repository & Archive

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS

- Collections

- Disciplines

AURA provided by Antioch University Libraries

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

Advertisement

Improving Student Attitudes Toward Autistic Individuals: A Systematic Review

- Original Paper

- Published: 24 August 2023

Cite this article

- Elise Settanni ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5331-3006 1 ,

- Lee Kern ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4071-7826 1 &

- Alyssa M. Blasko ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9799-3656 1

544 Accesses

12 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

There is an increasing number of autistic students being educated alongside their neurotypical peers. However, placing a student in the general education setting is not sufficient for meaningful inclusion. Historically, autistic students have had fewer friendships, been less accepted, and experienced stigmatization. Interventions to increase peer attitudes toward autism have emerged as a method for creating more inclusive environments. The purpose of this literature review was to describe the interventions to improve peer attitudes toward autism, review the quality of the research, and determine the effectiveness of interventions. Specifically, this review aimed to answer the following questions: (1) what are participant characteristics and components of interventions designed to improve attitudes toward autistic individuals? (2) What is the methodological quality of interventions designed to improve attitudes toward autistic individuals, as measured by Council for Exceptional Children standards for evidence-based practices in special education (2014) criteria? (3) What is the effectiveness of interventions to improve attitudes toward autistic individuals? A total of 13 studies were located through a systematic search. Included studies were coded for study characteristics, participant characteristics, intervention, and outcomes. Across the studies, there were a total of 2097 participants. All studies included contact (either direct, indirect, or peer-mediation) and most included an education component ( k = 10). Findings indicated that interventions are effective at improving attitudes toward autism, but further research is required to determine their overall impact.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Evidence-Based Practices for Children, Youth, and Young Adults with Autism: Third Generation Review

Kara Hume, Jessica R. Steinbrenner, … Melissa N. Savage

The Role of School in Adolescents’ Identity Development. A Literature Review

Monique Verhoeven, Astrid M. G. Poorthuis & Monique Volman

Concerns About ABA-Based Intervention: An Evaluation and Recommendations

Justin B. Leaf, Joseph H. Cihon, … Dara Khosrowshahi

Consistent with recommendations from the autistic community, the authors are using identity first language when referring to autistic people (Botha et al., 2023 ).

*Indicates studies included in review

Alcorn, A. M., Fletcher-Watson, S., McGeown, S., Murray, F., Aitken, D., Peacock, L. J. J., & Mandy, W. (2022). Learning About Neurodiversity at School: A resource pack for primary school teachers and pupils . University of Edinburgh.

Google Scholar

Alquraini, T., & Gut, D. (2012). Critical components of successful inclusion of students with severe disabilities: Literature review. International Journal of Special Education, 27 (1), 19.

Armstrong, M., Morris, C., Abraham, C., & Tarrant, M. (2017). Interventions utilising contact with people with disabilities to improve children’s attitudes towards disability: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Disability and Health Journal, 10 (1), 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2016.10.003

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Artiles, A. J., & Kozleski, E. B. (2016). Inclusive education’s promises and trajectories: Critical notes about future research on a venerable idea. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 24 , 43. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.24.1919

Article Google Scholar

Aubé, B., Follenfant, A., Goudeau, S., & Derguy, C. (2020). Public stigma of autism spectrum disorder at school: Implicit attitudes matter. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04635-9

Botha, M., Hanlon, J., & WIlliams, G. L. (2023). Does language matter? Identity-first versus person-first language use in autism research: A response to Vivanti. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 53 (2), 870–878. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04858-w

Campbell, J. M. (2006). Changing children’s attitudes toward autism: A process of persuasive communication. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 18 (3), 251–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-006-9015-7

Campbell, J. M. (2007). Middle school students’ response to the self-introduction of a student with autism: Effects and perceived similarity, prior awareness, and educational message. Remedial and Special Education, 28 (3), 163–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/07419325070280030501

*Campbell, J. M., Caldwell, E. A., Railey, K. S., Lochner, O., Jacob, R., & Kerwin, S. (2019). Educating students about autism spectrum disorder using the Kit for Kids curriculum: Effects on knowledge and attitudes. School Psychology Review, 48 (2), 145–156. https://doi.org/10.17105/SPR-2017-0091.V48-2

Campbell, J. M., Ferguson, J. E., Herzinger, C. V., Jackson, J. N., & Marino, C. A. (2004). Combined descriptive and explanatory information improves peers’ perceptions of autism. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 25 (4), 321–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2004.01.005

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). Data & statistics on autism spectrum disorder . https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data.html

Cook, B. G., Buysse, V., Klingner, J., Landrum, T. J., McWilliam, R. A., Tankersley, M., & Test, D. W. (2015). CEC’s standards for classifying the evidence base of practices in special education. Remedial and Special Education, 36 (4), 220–234. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932514557271

Council for Exceptional Children. (2014). Council for exceptional children standards for evidence-based practices in special education . Council for Exceptional Children.

Education for All Handicapped Children Act, P.L. 94-142, 94th Congress. (1975). https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-89/pdf/STATUTE-89-Pg773.pdf

de Boer, A., Pijl, S. J., Post, W., & Minnaert, A. (2013). Peer acceptance and friendships of students with disabilities in general education: The role of child, peer, and classroom variables. Social Development, 22 (4), 831–844. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2012.00670.x

*Fachantidis, N., Syriopoulou-Delli, C. K., Vezyrtzis, I., & Zygopoulou, M. (2019). Beneficial effects of robot-mediated class activities on a child with ASD and his typical classmates. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 66 (3), 245–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/20473869.2019.1565725

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Freer, J. R. R. (2021). Students’ attitudes toward disability: A systematic literature review (2012–2019). International Journal of Inclusive Education . https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2020.1866688

Gonzalez, A. M., Dunlop, W. L., & Baron, A. S. (2017). Malleability of implicit associations across development. Developmental Science, 20 (6), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12481

Griffin, W. B. (2019). Peer perceptions of students with autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 34 (3), 183–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357618800035

Koster, M., Nakken, H., Pijl, S. J., van Houten, E., & van Houten-van den Bosch, E. J. (2009). Being part of the peer group: A literature study focusing on the social dimension of inclusion in education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 13 (2), 117–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110701284680

Koster, M., Pijl, S. J., Nakken, H., & Van Houten, E. (2010). Social participation of students with special needs in regular primary education in the netherlands. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 57 (1), 59–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/10349120903537905

Lochner, O. K. (2019). Exploring the impact of autism awareness interventions for general education students: A meta-analysis [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Kentucky.

Maenner, M. J., Warren, Z., Williams, A. R., Amoakohene, E., Bakian, A. V., Bilder, D. A., Durkin, M. S., Fitzgerald, R. T., Furnier, S. M., Hughes, M. M., Ladd-Acosta, C. M., McArthur, D., Pas, E. T., Salina, A., Vehorn, A., Williams, S., Esler, A., Grzybowski, A., Hall-Lande, J., & Shaw, K. A. (2023). Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—Autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Surveillance Summaries 2023, 72 (2), 1–20.

Maïano, C., Normand, C. L., Salvas, M.-C., Moullec, G., & Aimé, A. (2016). Prevalence of school bullying among youth with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Autism Research, 9 , 601–615. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1568

Majeika, C. E., Van Camp, A. M., Wehby, J. H., Kern, L., Commisso, C. E., & Gaier, K. (2020). An evaluation of adaptations made to check-in check-out. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 22 (1), 25–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300719860131

*Mavropoulou, S., & Sideridis, G. D. (2014). Knowledge of autism and attitudes of children towards their partially integrated peers with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44 (8), 1867–1885. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2059-0

*McHale, S. M., & Simeonsson, R. J. (1980). Effects of interaction on nonhandicapped children’s attitudes toward autistic children. American Journal of Mental Deficiency, 85 (1), 18–24.

PubMed Google Scholar

Mitchell, P., Sheppard, E., & Cassidy, S. (2021). Autism and the double empathy problem: Implications for development and mental health. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 39 (1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjdp.12350

*Morris, S., O’Reilly, G., & Byrne, M. K. (2020). Understanding our peers with Pablo: Exploring the merit of an autism spectrum disorder de-stigmatisation programme targeting peers in irish early education mainstream settings. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50 (12), 4385–4400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04464-w

Organization for Autism Research (OAR). (2023). Kit for Kids . Organization for Autism Research. https://researchautism.org/educators/kit-for-kids

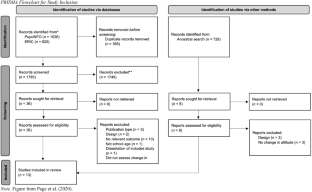

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Bourtron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., & Moher, D. (2020). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 10 , 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4

Pierce, N. P., O’Reiller, M. F., Sorrells, A. M., Fragale, C. L., White, P. J., Aguilar, J. M., & Cole, H. A. (2014). Ethnicity reporting practices for empirical research in three autism-related journals. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44 (7), 1507–1519. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2041-x

*Ranson, N. J., & Byrne, M. K. (2014). Promoting peer acceptance of females with higher-functioning autism in a mainstream education setting: A replication and extension of the effects of an autism anti-stigma program. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44 (11), 2778–2796. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2139-1

*Rodríguez-Medina, J., Martín-Antón, L. J., Carbonero, M. A., & Ovejero, A. (2016). Peer-mediated intervention for the development of social interaction skills in high-functioning autism spectrum disorder: A pilot study. Frontiers in Psychology . https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01986

Rotheram-Fuller, E., Kasari, C., Chamberlain, B., & Locke, J. (2010). Social involvement of children with autism spectrum disorders in elementary school classrooms: ASD social involvement. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51 (11), 1227–1234. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02289.x

*Ryan, T. (2020). A children’s book read aloud and discussion intervention: Teaching typically developing children about autism spectrum disorder [Indiana University]. ProQuest.

*Sansi, A., Nalbant, S., & Ozer, D. (2021). Effects of an inclusive physical activity program on the motor skills, social skills and attitudes of students with and without autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51 (7), 2254–2270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04693-z

*Sasso, G. M., Simpson, R. L., & Novak, C. G. (1985). Procedures for facilitating integration of autistic children in public school settings. Analysis and Intervention in Developmental Disabilities, 5 (3), 233–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/0270-4684(85)90013-8

Sasson, N. J., Faso, D. J., Nugent, J., Lovell, S., Kennedy, D. P., & Grossman, R. B. (2017). Neurotypical Peers are Less Willing to interact with those with autism based on thin slice judgments. Scientific Reports, 7 (1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep40700

*Silton, N. R., & Fogel, J. (2012). Enhancing positive behavioral intentions of typical children towards children with autism. Journal of Cognitive and Behavioral Psychotherapies, 12 (2), 139–158. https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v3i4.399

*Simpson, L. A. (2013). Effect of a classwide peer-mediated intervention on the social interactions of students with low-functioning autism and the perceptions of typical peers . The University of San Francisco.

Simpson, L. A., & Bui, Y. (2016). Effects of a peer-mediated intervention on social interactions of students with low-functioning autism and perceptions of typical peers. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 51 (2), 162–178.

Steinbrenner, J. R., McIntyre, N., Rentschler, L. F., Pearson, J. N., Luelmo, P., Jaramillo, M. E., Boyd, B. A., Wong, C., Nowell, S. W., Odom, S. L., & Humer, K. A. (2022). Patterns in reporting and participant inclusion related to race and ethnicity in autism intervention literature: Data from a large-scale systematic review of evidence-based practice. Autism, 26 (8), 2026–2040. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613211072593

*Staniland, J. J., & Byrne, M. K. (2013). The effects of a multi-component higher-functioning autism anti-stigma program on adolescent boys. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43 (12), 2816–2829. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803.013.1829-4

Swaim, K. F., & Morgan, S. B. (2001). Children’s attitudes and behavioral intentions toward a peer with autistic behaviors: Does a brief educational intervention have an effect? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31 (2), 195–205. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010703316365

Tonnsen, B. L., & Hahn, E. R. (2016). Middle school students’ attitudes toward a peer with autism spectrum disorder: Effects of social acceptance and physical inclusion. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 31 (4), 262–274. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357614559213

West, E. A., Travers, J. C., Kemper, T. D., Liberty, L. M., Cote, D. L., McCollow, M. M., & Stansberry Brusnahan, L. L. (2016). Racial and ethnic diversity of participants in research supporting evidence-based practices for learners with autism spectrum disorder. The Journal of Special Education, 50 (3), 151–163. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022466916632495

White, S. W., Scahill, L., Klin, A., Koenig, K., & Volkmar, F. R. (2007). Educational placements and service use patterns of individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37 (8), 1403–1412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-006-0281-0

Wood, R., & Happé, F. (2023). What are the views and experiences of autistic teachers? Findings from an online survey in the UK. Disability and Society, 38 (1), 47–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2021.1916888

Zeidan, J., Fombonne, E., Scorah, J., Ibrahim, A., Durkin, M. S., Saxena, S., Yusuf, A., Shih, A., & Elsabbagh, M. (2022). Global prevalence of autism: A systematic review update. Autism Research, 15 (5), 778–790. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2696

Download references

No funding was received to conduct this study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

College of Education, Lehigh University, 111 Research Drive, A117, Bethlehem, PA, 18015, USA

Elise Settanni, Lee Kern & Alyssa M. Blasko

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors contributed to the preparation of the manuscript. ES and LK contributed to the conceptualization and design of the paper. ES conducted the literature search. ES and AMB conducted the literature screening and data analysis. ES and LK drafted and critically revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Elise Settanni .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

We have no known conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Settanni, E., Kern, L. & Blasko, A.M. Improving Student Attitudes Toward Autistic Individuals: A Systematic Review. J Autism Dev Disord (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-023-06082-8

Download citation

Accepted : 26 July 2023

Published : 24 August 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-023-06082-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Autism spectrum disorder

- Anti-stigma

- Systematic review

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Behav Anal Pract

- v.12(3); 2019 Sep

Utilizing Peers to Support Academic Learning for Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder

Texas A&M University, 4225 TAMU, College Station, TX 77843-4226 USA

Kimberly Vannest

Sandy d. smith.

The inclusion of students with autism spectrum disorder in academic settings is becoming more common. However, most practices focus on increasing social skills even though students also struggle in academic areas. There is a need for strategies that address both social and academic skill deficits, are evidence based, and are easy to implement in the classroom. Peer-mediated interventions have evidence supporting their use in promoting social and academic behavior change and are socially valid and cost-effective. The purpose of this paper is to present examples of how to implement 2 common peer-tutoring strategies: Classwide Peer Tutoring and Peer-Assisted Learning Strategies. Examples for implementing both strategies are provided using a hypothetical student in a general education setting, followed by a brief summary of evidence supporting the peer-mediated academic instruction.

Jacob is a freshman in high school. Diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in early elementary school, he has relied on one-to-one adult support in all academic coursework. When the paraprofessional providing support was absent during middle school, Jacob would struggle to engage in class and socialized less with his peers. His current special education teacher and his behavior analyst have observed that Jacob is more socially connected to adults than to peers. Jacob chooses to spend most of his time with adults (e.g., teachers, janitors, administration, and paraprofessionals), whereas same-age peers talk around lockers or sit in groups at lunch while on their cell phones. His math teacher, Mr. Matthews, is completing a master’s degree in special education with an emphasis in applied behavior analysis and utilizing evidence-based practices. Researching with the university library online databases; What Works Clearinghouse, an organization aimed at providing educators information about research and evidence-based practices suited for their needs; and Google Scholar, Mr. Matthews found repeated references to practices to increase skills in students with ASD, including peer tutoring, peer-mediated instruction (PMI), peer supports, and Classwide Peer Tutoring (CWPT). Mr. Matthews spoke with Jacob’s special education teacher and the behavior analyst about implementing PMI in his classroom, specifically CWPT.

Peer-Mediated Instruction

PMI is recognized as one of the most effective educational strategies available (Higgins et al., 2016 ; Zeneli & Tymms, 2015 ). Using peers to provide instruction to one another is not a new concept (Asselin & Vasa, 1981 ; Delquadri, Greenwood, Whorton, Carta, & Hall, 1986 ; Scruggs, Mastropieri, & Richter, 1985 ), and research conducted across grades and ages indicates PMI is a valid strategy. Prominent methods include CWPT (Delquadri et al., 1986 ) and Peer-Assisted Learning Strategies (PALS; Fuchs, Fuchs, Mathes, & Simmons, 1997 ).

Furthermore, CWPT and PALS demonstrate positive social and academic results for students with disabilities (Bowman-Perrott et al., 2013 ; Lane, 2004 ; Ryan, Reid, & Epstein, 2004 ; Vannest, Harrison, Temple-Harvey, Ramsey, & Parker, 2011 ), including ASD, and are endorsed by the What Works Clearinghouse in specific subject areas (U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, What Works Clearinghouse, 2007 , 2012 ).

However, the effects of PMI in math and specific content areas in specific grades cannot be assumed (see Table Table1). 1 ). Additionally, Table Table1 1 describes skills previously taught across subjects and grades for students with ASD.

Targeted skills across grade and subject using peer-mediated instruction

Note: — indicates data not available

Classwide Peer Tutoring

CWPT was designed by the University of Kansas as a program to improve instruction for students who are minority, disadvantaged, or disabled. CWPT is made up of instructional principles, such as opportunities to respond, a functionality of key academic skill areas, and behavioral principles. Opportunities to respond are the chances students are provided to reply to antecedents or prompts; ideally, it is best to have ample opportunities to respond when learning new material. The functionality of key academic skills is identifying targets used to measure what students are expected to learn. Behavior principles include the use of reinforcement, contingencies, and corrective feedback.

CWPT is useful in various settings and can be implemented in 30-min intervals. CWPT begins by training students with teaching, modeling, and role-playing the expectations, followed by providing corrective feedback. The teacher explains the rules, how teams function, and how points are earned. Teachers demonstrate the tutoring process by having students act as the tutees and the teacher as the tutor. Points are delivered and corrective feedback is given. The procedure is demonstrated again with two students acting as tutor and tutee while the teacher provides feedback, reinforcement, and correction. These demonstrations are repeated until the teacher is confident all the students understand. Students then practice the skills as the teacher monitors and provides feedback, reinforcement, and correction of errors. Sessions may take longer when training younger students.

During CWPT, a timer is set for 10 min. As the tutee engages in the material to earn points for his or her team, the tutor observes the tutee and awards points or corrects errors. Two points are awarded if the tutee reads the passage without errors, one point is awarded if the tutor corrects an error, and no points are awarded for word omissions, substitutions, or hesitations. When the tutor corrects the error, he or she correctly pronounces the word and has the tutee reread the sentence. Points are awarded based on the written or oral response for spelling, math, and writing sessions. Two points are awarded for no errors and one point is awarded if the tutee responds correctly after receiving feedback from the tutor. The teacher actively supervises by providing assistance when needed and awarding points to tutors who use correct tutoring behaviors. Bonus points are given for quick responses and cooperation with peers. At the conclusion of the 10 min, roles are switched and the procedure is repeated. Points are added together and graphed at the end of each session, and the winning team is selected after a predetermined time (e.g., day, week, or month). The winning team receives applause and praise and the losing team is praised for making a respectable effort (Delquadri et al., 1986 ). Figure Figure1 1 provides a scoring sheet students can use when engaged in peer tutoring.

Scoring sheet for CWPT and PALS

Jacob’s math teacher decided to utilize CWPT in his algebra class due to his concern for Jacob’s progress and social skills. The school’s behavior analyst, familiar with CWPT, provided Mr. Matthews with training and support on how to properly carry out CWPT in the class. Mr. Matthews then provided training to the students and began the procedure after his initial direct instruction.

Using Jacob as an illustration, the following steps are used for implementing CWPT:

- Teach the procedure using explanation, modeling, role-play, and corrective feedback, similar to behavioral skills training: Mr. Matthews explains to the class that, following the lecture, they will work with each other to practice math skills. The teacher models the steps involved with a student volunteer. Mr. Matthews acts as the tutor and asks the student to complete each step of the math problem. He provides praise when a step is completed correctly. The student is asked to make a mistake on the next problem; Mr. Matthews models how to tell the student to correct the error. He and the student switch roles and Mr. Matthews provides feedback to the student about delivering reinforcement and feedback.

- Explain rules for teams and how to earn points and reinforcement (e.g., praise): During role-playing and modeling, Mr. Matthews explains that groups receive two points when the student gets a problem correct without assistance. Groups receive one point if a correction is made and no points if an error is made and not corrected.

- Have students role-play while providing feedback: Mr. Matthews pairs Jacob with Samuel, a student who has shown proficiency in class and has taken an interest in supporting Jacob. Mr. Matthews provides math problems for the class to complete. He walks around praising students implementing the tutoring process correctly and gives feedback to those who make an error. Samuel is helping Jacob with a math problem when Mr. Matthews walks by; he sees Samuel is correcting an error and praises him. Later, he notices Samuel not correcting an error; he stops and points out the error and models to Samuel what he should do, then praises both for working cooperatively. The roles are reversed, and Mr. Matthews gives feedback to Jacob when he is tutoring Samuel.

- During implementation, pair students of high and low proficiently and set a 10-min timer: Mr. Matthews is confident the students understand what to do after a few days of practice. The groups that practiced together remain the same, but Mr. Matthews checks to ensure lower performing students are paired with higher performing students. Once he finishes his daily lecture, Mr. Matthews starts the 10-min timer as the student pairs begin working on the assigned math problems.

- Have the tutee engage in the subject materials and reinforce with points for going over materials correctly: Samuel begins by having Jacob independently work on the problem. Jacob works through the problem correctly and explains how each step is completed. Jacob receives praise and two points for each correct answer.

- Correct errors by modeling and having the tutee review the material: Samuel provides feedback if Jacob misses a step or explains a step incorrectly. Jacob repeats what is taught by Samuel, fixes his error, and receives praise and one point.

- Have peers switch roles after 10 min: The timer goes off after 10 min, and the students switch roles. Jacob monitors Samuel as he works through the problems selected by Mr. Matthews and implements the same point system.

- Actively monitor sessions and reinforce correct implementation: Mr. Matthews walks around and awards points to teams working well together and provides clarification as needed.

Mr. Matthews discussed the success he has seen with CWPT with Jacob’s reading teacher, Mrs. Li. Interested in helping Jacob academically, as well as decreasing his reliance on the one-to-one support, she used Google Scholar to search for a CWPT model designed for reading and found PALS.

Peer-Assisted Learning Strategies

The PALS program was initially developed to teach reading to kindergarten through sixth-grade students but has expanded to secondary settings (Fuchs et al., 2001 ; Fuchs, Fuchs, & Kazdan, 1999 ). Student pairs are based on ability level, typically with one student proficient in an area whereas the other student is not. In contrast to CWPT, pairs are rotated so students have the chance both to serve as tutor and tutee and to work with multiple partners; lessons typically last 35 min and are implemented at least three times per week. Activities include partner reading, paragraph “shrinking,” and prediction relay. Partner reading entails the tutor reading the passage first. Reading the passage provides the opportunity for the tutee to hear the passage and study words that are more difficult before he or she reads aloud and receives corrective feedback for mispronunciations. Each student reads for 5 min before switching roles. Students engaged in paragraph “shrinking” provide a summary of the passage, giving sequential details of essential events, and state the main idea. A prediction relay consists of the students guessing what will happen, reading the next page, and summarizing what was read. The tutor decides if the tutee made a correct prediction. As with partner reading, students switch roles every 5 min.

The kindergarten and first-grade PALS curriculum consist of 70 precreated lesson sheets. Teachers select reading material based on student needs. First-grade lessons begin by reviewing sounds and words for 15 min to emphasize hearing and identifying sounds, sounding out words, identifying sight words, and practicing reading the passages. Next, the students work on story sharing by predicting what will happen in the story, reading aloud, and recounting stories. Lessons for students in second through sixth grade are geared to improving the accuracy of reading, fluency, and comprehension.

Additionally, PALS can be used to teach high school students how to read for information and take notes. Students are motivated and reinforced by earning points for their respective teams if no errors occur while reading sentences, they demonstrate effort, and they correctly identify the subject and main idea of the passage. Points assigned by teachers and tutors are recorded on scorecards. The PALS process is taught through workshops via modeling and role-play, and manuals are given outlining the curriculum (Fuchs et al., 1997 ).

Mrs. Li began using the PALS program in her reading class after attending a workshop. She taught her students how to work as teams and utilize paragraph shrinking, partner reading, and prediction relays. Mrs. Li recorded improved academic performance and better engagement with peers as a result.

Using Jacob as an illustration, the following steps are used for implementing PALS:

- Teach students with an explanation, modeling, role-play, and corrective feedback: Mrs. Li explains that the students will begin working with each other in reading class. She models the steps with a student volunteer. Mrs. Li starts in the role of tutor and begins partner reading: reading the passage aloud for 5 min. She explains this allows the tutee to hear the passage correctly. The student then reads for 5 min as Mrs. Li (as the tutor) provides feedback for mispronunciations and omissions. During paragraph shrinking, the student reads the paragraph as Mrs. Li silently follows along; she then asks the student to summarize the reading and provides feedback as necessary. To demonstrate prediction relays, Mrs. Li models the role of the tutor by reading a page to the student and asking him to guess what will happen next. The student provides his answer. Mrs. Li reads the next page and reinforces correct predictions. She responds to incorrect guesses by pointing out areas in the passage that may have suggested the correct prediction.

- Identify rules for teams and how to earn points and reinforcement (e.g., praise): During the role-play and modeling stage, Mrs. Li explains that the group receives two points when the reader implements the strategies correctly. If a correction is made during the activity, the group receives one point. The group does not receive points if an error is made and not corrected.

- Have students role-play while providing feedback: Mrs. Li decides she will change pairs each time a new book is started. She pairs Jacob with Sylvia for the first book because Sylvia has volunteered to read books to younger students in the past. Mrs. Li gives the class new reading materials. She circulates around the room and gives praise to students tutoring correctly and feedback to those who make an error. Sylvia is helping Jacob with word pronunciation when Mrs. Li walks by; she sees Sylvia is correcting the error and praises her. Later, she notices Sylvia did not correct during paragraph shrinking; she stops and points out the error and models to Sylvia what she should do, then praises both for working together appropriately. The roles are reversed, and Mrs. Li gives feedback to Jacob as he tutors Sylvia.

- Pair students of high and low proficiently and set a 5-min timer: Mrs. Li is confident the students understand what to do after a few days of practice. She pairs her students based on ability and need, keeping Jacob and Sylvia together. She instructs the students to begin reading the assigned book with their partners. A timer is set for 5 min, and students begin.

- Have the tutor engage with subject materials: Sylvia reads to Jacob for 5 min.

- Have peers switch roles after 5 min: The students switch when the timer indicates the end of the 5 min. Jacob then reads the same passage, and Sylvia provides feedback if words are mispronounced or omitted. If Jacob reads the passage without errors, he is given praise and two points.

- Have tutors correct errors by modeling and having the tutee review the material: If Sylvia makes corrections for any of the activities, the group receives one point. Jacob then repeats what is read or corrected by Sylvia, fixes his error, and receives an additional point and praise.

- Circulate during sessions and award points and reinforcement for correct implementation: During PALS, Mrs. Li moves around the room and assigns points for teams working well together and helping with problems needing clarification. The steps are repeated when engaging in paragraph shrinking and prediction relays.

- Assess impact: Mrs. Li graphs Jacob’s homework and test scores and sees an increasing trend after implementing PALS. Mrs. Li reports that Jacob seems more eager to participate in class and is socializing more with his peers while reading.

As a result of policies such as Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act ( 2004 ) and the Every Student Succeeds Act (2015) (Klein, 2016 ), the majority of students with ASD spend 40% or more of their time in general education settings (Snyder, de Brey, & Dillow, 2016 ; Zablotsky, Black, Maenner, Schieve, & Blumberg, 2015 ). Additionally, students with ASD included in general education settings perform better on academic achievement measures (Kurth & Mastergeorge, 2010 ).

Because the prevalence of ASD has risen to 1 in 59 people (Centers for Disease Control [CDC], 2018 ), it is essential that effective and efficient intervention strategies are employed in order to increase social and academic success. Teachers face challenges: difficulty in modifying instruction, in accommodation of differences, in managing challenging behaviors, and in providing opportunities for students with ASD to interact and foster relationships with their peers (Lindsay, Proulx, Thomson, & Scott, 2013 ). A lack of knowledge about strategies and implementation can lead to poor academic and social outcomes for students with ASD (Carnevale, Smith, & Strohl, 2013 ; Newman et al., 2011 ).

Academic achievement for students with ASD is often treated as secondary to communication and social skills (Petrina, Carter, & Stephenson, 2017 ). As a result, research regarding academic achievement in the population is less prevalent than research about communication and social skills (Keen, Webster, & Ridley, 2016 ; Wong et al., 2013 ). Although students do face barriers to successful inclusion, such as anxiety, poor social skills, adaptability problems, and stereotypical behaviors (Carter et al., 2014 ; Lindsay et al., 2013 ), many students with ASD demonstrate shortcomings in core subject areas (Keen et al., 2016 ; Kurth & Mastergeorge, 2010 ; Wei, Christiano, Yu, Wagner, & Spiker, 2015 ). Deficits in reading and math are detected as early as preschool (Miller et al., 2017 ), and parents report frustration or displeasure with the academic progress for children with ASD (Mackintosh, Goin-Kochel, & Myers, 2012 ; McDonald & Lopes, 2014 ; Starr & Foy, 2012 ).

The use of peers has demonstrated improved academic and social outcomes for students with ASD. PMI is a promising strategy because it demonstrates benefits for tutors and tutees (Dineen, Clark, & Risley, 1977 ; Franca, Kerr, Reitz, & Lambert, 1990 ; Schaefer, Cannella-Malone, & Carter, 2016 ), is less socially stigmatizing than traditional specialized instruction (Broer, Doyle, & Giangreco, 2005 ; Carter, Sisco, Melekoglu, & Kurkowski, 2007 ), and is cost-effective (Hoff & Robinson, 2002 ). Peers are instrumental in keeping students on task throughout independent work (Hoff & Robinson, 2002 ; McCurdy & Cole, 2014 ), aid in generalization, and are an easily accessible resource (McCurdy & Cole, 2014 ). PMI also generates time for teachers to focus on instruction and provide individualized support when needed (Hoff & Robinson, 2002 ).

PMI is easy to implement and beneficial for both tutors and tutees (Asselin & Vasa, 1981 ; Delquadri et al., 1986 ; Scruggs et al., 1985 ). Both students improve social and academic skills, gain confidence in their skills, and create or strengthen friendships (Asselin & Vasa, 1981 ; Bedrosian, Lasker, Speidel, & Politsch, 2003 ; Carter et al., 2015 ; Franca et al., 1990 ; Huber, 2016 ; Huber, Carter, Lopano, & Stankiewicz, 2018 ; Scruggs et al., 1985 ). Positive outcomes for students and teachers make PMI a promising, easily implemented, cost-efficient strategy that can be used across grade levels and subject areas. PMI not only improves social deficits in students with ASD but also can improve academic skills in some areas, bridging the gap between behavioral and academic achievement.

Both CWPT and PALS are strategies recognized as effective by the What Works Clearinghouse. Although more research needs to be conducted to expand the conditions under which PMI can best benefit students with ASD across content areas, PMI has already demonstrated success in supporting students with ASD in general education settings with the acquisition of academic, social, and communication skills.

The contents of this manuscript were developed under the Preparation of Leaders in Autism Across the Lifespan grant awarded by the U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education Programs (Grant No. H325D110046). The views herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Department of Education.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

April Haas declares that she has no conflict of interest. Kimberly Vannest declares that she has no conflict of interest. Sandy D. Smith declares that she has no conflict of interest.

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- Asselin, S. B., & Vasa, S. F. (1981). Let the kids help one another: A model training and evaluation system for the utilization of peer tutors with special needs students in Vocational Education . Atlanta, GA: Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the American Vocational Association.

- Bedrosian J, Lasker J, Speidel K, Politsch A. Enhancing the written narrative skills of an AAC student with autism: Evidence-based research issues. Topics in Language Disorders. 2003; 23 :305–324. doi: 10.1097/00011363-200310000-00006. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bowman-Perrott L, Davis H, Vannest KJ, Williams L, Greenwood C, Parker R. Academic benefits of peer tutoring: A meta-analytic review of single-case research. School Psychology Review. 2013; 42 :39–55. [ Google Scholar ]

- Broer SM, Doyle MB, Giangreco MF. Perspectives of students with intellectual disabilities about their experiences with paraprofessional support. Exceptional Children. 2005; 71 :415–430. [ Google Scholar ]

- Carnevale, A. P., Smith, N., & Strohl, J. (2013). Recovery: Job growth and education requirements through 2020. Washington, DC:Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce.

- Carter, E. W., Asmus, J., Moss, C. K., Biggs, E. E., Bolt, D. M., Born, T. L., . . . Fesperman, E. (2015). Randomized evaluation of peer support arrangements to support the inclusion of high school students with severe disabilities . Exceptional Children, 82, 209–233. 10.1177/0014402915598780

- Carter EW, Cushing LS, Clark NM, Kennedy CH. Effects of peer support interventions on students’ access to the general curriculum and social interactions. Research and Practice for Persons With Severe Disabilities. 2005; 30 :15–25. doi: 10.2511/rpsd.30.1.15. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carter EW, Sisco LG, Melekoglu MA, Kurkowski C. Peer supports as an alternative to individually assigned paraprofessionals in inclusive high school classrooms. Research and Practice for Persons With Severe Disabilities. 2007; 32 :213–227. doi: 10.2511/rpsd.32.4.213. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carter, M., Stephenson, J., Clark, T., Costley, D., Martin, J., Williams, K., . . . Bruck, S. (2014). Perspectives on regular and support class placement and factors that contribute to success of inclusion for children with ASD. Journal of International Special Needs Education, 17, 60–69. 10.9782/2159-4341-17.2.60

- Centers for Disease Control. (2018, April 26). Autism prevalence slightly higher in CDC’s ADDM network . Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2018/p0426-autism-prevalence.html

- Delquadri J, Greenwood CR, Whorton D, Carta JJ, Hall RV. Classwide peer tutoring. Exceptional Children. 1986; 52 :535–542. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dineen JP, Clark HB, Risley TR. Peer tutoring among elementary students: Educational benefits to the tutor. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1977; 10 :231–238. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1977.10-231. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dugan E, Kamps D, Leonard B, Watkins N, Rheinberger A, Stackhaus J. Effects of cooperative learning groups during social studies for students with autism and fourth-grade peers. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1995; 28 :175–188. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1995.28-175. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- ESSA (2015). Every Student Succeeds Act of 2015

- Franca VM, Kerr MM, Reitz AL, Lambert D. Peer tutoring among behaviorally disordered students: Academic and social benefits to tutor and tutee. Education and Treatment of Children. 1990; 13 :109–128. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fuchs D, Fuchs LS, Mathes PG, Simmons DC. Peer-assisted learning strategies: Making classrooms more responsive to diversity. American Educational Research Journal. 1997; 34 :174–206. doi: 10.3102/00028312034001174. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fuchs, D., Fuchs, L. S., Thompson, A., Yen, L., Al Otaiba, S., Nyman, K., . . . Saentz, L. (2001). Peer-assisted learning strategies in reading: Extensions for kindergarten, first grade, and high school. Remedial and Special Education, 22, 15–21. 10.1177/074193250102200103

- Fuchs LS, Fuchs D, Kazdan S. Effects of peer-assisted learning strategies on high-school students with serious reading problems. Remedial and Special Education. 1999; 20 :309–318. doi: 10.1177/074193259902000507. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Higgins, S., Katsipataki, M., Villanueva-Aguilera, A. B., Coleman, R., Henderson, P., Major, L. E., . . . Mason, D. (2016). The Sutton Trust-Education Endowment Foundation Teaching and Learning Toolkit. London: Education Endowment Foundation.

- Hoff KE, Robinson SL. Best practices in peer-mediated interventions. Best Practices in School Psychology IV. 2002; 2 :1555–1567. [ Google Scholar ]

- Huber, H. B. (2016). Structural analysis to inform peer support arrangements for high school students with autism (Unpublished dissertation). Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN. [ PubMed ]

- Huber HB, Carter EW, Lopano SE, Stankiewicz KC. Using structural analysis to inform peer support arrangements for high school students with severe disabilities. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2018; 123 :119–139. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-123.2.119. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act Regulations (2004). Retrieved from https://sites.ed.gov/idea/statuteregulations/ . Accessed 31 May 2018.

- Kamps D, Locke P, Delquadri J, Hall RV. Increasing academic skills of students with autism using fifth grade peers as tutors. Education and Treatment of Children. 1989; 12 :38–51. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kamps DM, Barbetta PM, Leonard BR, Delquadri J. Classwide peer tutoring: An integration strategy to improve reading skills and promote peer interactions among students with autism and general education peers. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994; 27 :49–61. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-49. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kamps DM, Leonard B, Potucek J, Garrison-Harrell L. Cooperative learning groups in reading: An integration strategy for students with autism and general classroom peers. Behavioral Disorders. 1995; 21 :89–109. doi: 10.1177/019874299502100103. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Keen D, Webster A, Ridley G. How well are children with autism spectrum disorder doing academically at school? An overview of the literature. Autism. 2016; 20 :276–294. doi: 10.1177/1362361315580962. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Klein, A. (2016). The every student succeeds act: An ESSA overview. Education Week , 31.

- Kurth JA, Mastergeorge AM. Academic and cognitive profiles of students with autism: Implications for classroom practice and placement. International Journal of Special Education. 2010; 25 (2):8–14. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lane, K. L. (2004). Academic instruction and tutoring interventions for students with emotional/behavioral disorders: 1990 to present. Handbook of Research in Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 462–486. New York: Guilford Press.

- Lindsay S, Proulx M, Thomson N, Scott H. Educators’ challenges of including children with autism spectrum disorder in mainstream classrooms. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education. 2013; 60 :347–362. doi: 10.1080/1034912X.2013.846470. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mackintosh VH, Goin-Kochel RP, Myers BJ. “What do you like/dislike about the treatments you’re currently using?” A qualitative study of parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2012; 27 :51–60. doi: 10.1177/1088357611423542. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Marshak L, Mastropieri MA, Scruggs TE. Curriculum enhancements in inclusive secondary social studies classrooms. Exceptionality. 2011; 19 :61–74. doi: 10.1080/09362835.2011.562092. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McCurdy EE, Cole CL. Use of a peer support intervention for promoting academic engagement of students with autism in general education settings. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2014; 44 :883–893. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1941-5. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McDonald J, Lopes E. How parents home educate their children with an autism spectrum disorder with the support of the schools of isolated and distance education. International Journal of Inclusive Education. 2014; 18 :1–17. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2012.751634. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Miller LE, Burke JD, Troyb E, Knoch K, Herlihy LE, Fein DA. Preschool predictors of school-age academic achievement in autism spectrum disorder. The Clinical Neuropsychologist. 2017; 31 :382–403. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2016.1225665. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Newman, L., Wagner, M., Knokey, A. M., Marder, C., Nagle, K., Shaver, D., & Wei, X. (2011). The post-high school outcomes of young adults with disabilities up to 8 years after high school: A report from the national longitudinal transition study-2 (NLTS2). NCSER 2011-3005. National Center for Special Education Research. Retrieved from ERIC website: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED524044.pdf . Accessed 3 Oct 2018.

- Petrina N, Carter M, Stephenson J. Teacher perception of the importance of friendship and other outcome priorities in children with autism spectrum disorder. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities. 2017; 52 :107–119. [ Google Scholar ]

- Regelski, R. E., Jr. (2016). The effectiveness of peer-assisted learning strategies on reading comprehension for students with autism spectrum disorder (Doctoral dissertation). Pittsburgh, PA:University of Pittsburgh.

- Ryan JB, Reid R, Epstein MH. Peer-mediated intervention studies on academic achievement for students with EBD: A review. Remedial and Special Education. 2004; 25 :330–341. doi: 10.1177/07419325040250060101. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schaefer JM, Cannella-Malone HI, Carter EW. The place of peers in peer mediated interventions for students with intellectual disability. Remedial and Special Education. 2016; 37 :345–356. doi: 10.1177/0741932516629220. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Scott, K. L. (2013). Exploring personal connections to texts and peers using cooperative peers tutoring groups in English language arts instruction with students with autism (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest. (3574633)

- Scruggs TE, Mastropieri MA, Richter L. Peer tutoring with behaviorally disordered students: Social and academic benefits. Behavioral Disorders. 1985; 10 :283–294. doi: 10.1177/019874298501000408. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Snyder, T. D., de Brey, C., & Dillow, S. A. (2016). Digest of Education Statistics 2015, NCES 2016-014 . National Center for Education Statistics . Washington, DC: Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

- Starr EM, Foy JB. In parents’ voices: The education of children with autism spectrum disorders. Remedial and Special Education. 2012; 33 :207–216. doi: 10.1177/0741932510383161. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, What Works Clearinghouse. (2007, July). ClassWide Peer Tutoring. Retrieved from http://whatworks.ed.gov

- U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, What Works Clearinghouse. (2012, January). Adolescent literacy intervention report: Peer-Assisted Learning Strategies. Retrieved from http://whatworks.ed.gov

- Vannest KJ, Harrison JR, Temple-Harvey K, Ramsey L, Parker RI. Improvement rate differences of academic interventions for students with emotional and behavioral disorders. Remedial and Special Education. 2011; 32 :521–534. doi: 10.1177/0741932510362509. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wei X, Christiano ER, Yu JW, Wagner M, Spiker D. Reading and math achievement profiles and longitudinal growth trajectories of children with an autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2015; 19 :200–210. doi: 10.1177/1362361313516549. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wong, C., Odom, S. L., Hume, K., Cox, A. W., Fettig, A., Kucharczyk, S., . . . Schultz, T. R. (2013). Evidence-based practices for children, youth, and young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina, Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, Autism Evidence-Based Practice Review Group.

- Zablotsky, B., Black, L. I., Maenner, M. J., Schieve, L. A., & Blumberg, S. J. (2015). Estimated prevalence of autism and other developmental disabilities following questionnaire changes in the 2014 national health interview survey. National Health Statistics Reports, 87 , 1–20. [ PubMed ]

- Zeneli M, Tymms P. A review of peer tutoring interventions and social interdependence characteristics. International Journal for Cross-Disciplinary Subjects in Education. 2015; 5 :2504–2510. doi: 10.20533/ijcdse.2042.6364.2015.0341. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

50% OFF FOR 3 MONTHS - SUBSCRIBE NOW Learn more →

An Absurd Umbrella: Neurodiversity and the Autism Spectrum

Autism has become a catchall term to explain and dismiss the problem child. But it can also be viewed as a superpower.

Few debates in the mental health community have been as contentious as that over neurodiversity.

Neurodiversity is an approach that views certain mental conditions not as disabilities, but as differences, within the normal variability of human brain function. The neurodiversity framework has been applied to various conditions, but it is most commonly associated with autism, and has been prominently promoted by organizations such as the Autistic Self-Advocacy Network .

There is a core of truth to the arguments undergirding neurodiversity. Human minds cannot be whittled down to a unitary norm, and people with unusual or eccentric approaches can make great contributions to society. To “cure” autism might be said to be akin to “curing” creativity or introversion.

Yet the arguments against regarding autism as merely a benign form of neurodiversity are compelling, too. One prominent critic is Jill Escher, president of the National Council on Severe Autism. Escher has two autistic children, both of whom are profoundly impaired in their ability to perform basic life functions. As she has pointed out , the diagnosis of autism has taken on “an absurd umbrella aspect that can cover quirky people like Elon Musk , sensitive artists like the singer Sia , and even elite athletes like Tony Snell ,” some of whom “are so high-functioning I would consider my kids completely cured if they had similar abilities.”

The problem is inherent in the absurdity of an “autism spectrum” that groups together highly disparate individuals and conditions. On one end of the spectrum are people who may be different from the norm, but who are perfectly capable of living full and dignified lives. For them, the notion of a cure is sinister, even dystopian. On the other end are people who are severely disabled by the condition, for whom a cure might be an immeasurable gift.

Up until 2013, it was easier to differentiate between these two groups, since individuals who suffered some of the symptoms of autism, without the accompanying linguistic or intellectual impairments, were often diagnosed with Asperger’s Syndrome. But Asperger’s was defined out of existence in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), and folded into high-functioning autism, to create a single, all-encompassing autism category, with only incremental distinctions between levels of function.

Bringing back the diagnosis of Asperger’s Syndrome, however, would provide at best only a partial solution: the autism spectrum would remain a nebulous concept with poorly defined boundaries.

Rates of autism have skyrocketed in recent decades, from well below 1 in 1,000 children in the 1960s to 1 in 36 today. This is almost certainly partially attributable to a broadening of the diagnostic parameters. People who might have been considered merely somewhat abnormal in 1960 are liable to be classified as high-functioning autistic in 2024—a shift that has led to considerable confusion.

The DSM-5 criteria for diagnosing autism leave much open to subjective interpretation. The disorder is defined primarily by deficits of social communication and interaction, and restricted, repetitive patterns of behaviour. But relating to our fellow human beings is one of life’s central challenges, over which no one has ever achieved perfect mastery. Every human conflict—from the marital to the geopolitical—involves some breakdown in communication or interaction. As for repetitive patterns of behaviour: far from being pathological, these are often signs of self-discipline, as many people with productive morning routines can attest.

British autism researcher Simon Baron-Cohen has theorised that autism is a form of “extreme male brain.” In his model, male brains tend more towards systematising, and female brains tend more towards empathising; an autistic brain is just tilted unusually far towards systematising. But—assuming this is true—how much systematising is too much?

It could be said that the autism spectrum begins when one’s deficits are so extreme that they hinder one’s ability to function in everyday life. Yet many people on the autism spectrum can function perfectly well; they just prefer not to act in conventional ways. The process of hiding one’s autistic traits and behaviours in order to seem neurotypical is referred to as “autistic masking.” Some describe this as acting human ; the abovementioned singer Sia calls it “put(ting) my human suit on.” This seems less a manifestation of a disorder than a facet of the ordinary tension between individuality and conformity. If you know how to row a boat, but dislike doing it, then you do not have a deficit in rowing, only a preference.

Autism, like most mental illnesses, is said to be a neurological condition , yet it is diagnosed based on psychological factors. The determination is made not by a brain scan or lab test, but by an assessment of a child’s behaviour by a mental health professional. Once a diagnosis has been applied, there is no way to disprove it, since even behaviours that go against the diagnosis can be dismissed as masking.

All of this is treading far into the realm of unfalsifiability. Once you begin actively looking for a pattern of behaviour in someone, you are likely to find it and, once found, it is impossible to unsee. That is inherent in human nature: we Homo sapiens are both skilled pattern recognizers and immensely complex, multifaceted, often contradictory creatures. It is possible to examine someone’s behaviour and connect the dots in myriad ways, to reach many different conclusions.

We can see this dynamic with astrology: the twelve Zodiac signs are described in such a way as to give the illusion of specificity, with just enough vagueness and self-contradiction that it is impossible to conclusively prove the pseudoscience wrong. Likewise, lay diagnoses of autism have become commonplace in recent years; they are as easy to dispense, and as difficult to debunk, as calling someone a typical Scorpio or Aquarius once you know their star sign.

Those who diagnose others with autism are themselves systematising, rather than empathising. Any genuine attempt to alleviate psychological suffering necessitates that the sufferer be treated first and foremost as an individual. The human soul is not easily encapsulated, and there are innumerable reasons why a person may display a certain set of behaviours. To reduce someone’s humanity, in all its complexity, to a nuance-devoid heuristic like autism is the most impersonal, unsympathetic form of systematising imaginable.

The autism diagnosis also has the potential to be abused as a tool of authoritarian social control. Its criteria, as listed in the DSM, include such items as “abnormal social approach and failure of normal back-and-forth conversation,” “difficulties adjusting behaviour to suit various social contexts,” and “fixated interests that are abnormal in intensity or focus.” Autism is defined here in relation to societal norms, and within the confines of autism treatment, conformity is viewed as an aspirational value, while nonconformity is addressed as a shortcoming.

There is precedent for mental diagnoses being weaponised as tools of oppression. One example is the concept of sluggish schizophrenia , which was deployed in order to silence dissidents in the Soviet Union. After all, who but a lunatic would deny the self-evident glory of the USSR? Another notorious example is drapetomania , a disease proposed in 1851 by American physician Samuel Cartwright as the cause of slaves running away. Here, again, was an attempt to impose a moral paradigm via diagnosis: slavery, in Cartwright’s view, was rational, and so only an insane slave would flee captivity.

The construction of “sluggish schizophrenia” was clever because it was based on a legitimate disorder, and there are genuine grey areas surrounding schizophrenia. As many as 15 percent of the US population may have had auditory hallucinations. More broadly, most of us have an internal dialogue and many people—perhaps most—hold some beliefs that could be called delusional. These penumbrae are not entirely dissimilar to the ones surrounding autism. If psychiatrists were inclined to create a “schizophrenia spectrum” to encompass these cases, they might be somewhat justified in doing so.

Yet, unlike sluggish schizophrenia, high-functioning autism has been enthusiastically embraced by some—and not just by talented celebrities, either. The term has become oversaturated, used so frequently that it is now a repository of multiple meanings. “Autism” and related terms like “autist” have taken on a broad range of uses in layman-speak: they can be deployed insultingly, affectionately, or self-deprecatingly. Some of these usages are reminiscent of the way in which a racial slur might be reclaimed by minority group as a badge of pride.

What ADHD was to a previous generation, autism has become to this one: a catchall term to explain and dismiss the problem child (and particularly the problem boy). But what makes autism unusual is that it can also be viewed as a superpower. There have even been attempts to retroactively diagnose figures like Albert Einstein and Isaac Newton with autism.

Given the paradoxical cachet of being diagnosed with autism for some, all this smacks of social contagion.

An anecdote from Carl Jung’s Memories, Dreams, Reflections suggests one possible benefit of claiming to be autistic. When Jung was 12 years old, he relates, he was shoved by another boy and hit his head on a stone. “At the moment I felt the blow,” Jung writes, “the thought flashed through my mind: ‘Now you won’t have to go to school anymore.’” For the next six months, Jung was afflicted with fainting fits whenever he tried to do any schoolwork. He was allowed to stay home and pursue his own private interests, which he thoroughly enjoyed, although he could not shake a nagging sense of guilt.

One day, Jung heard his father lamenting, “What will become of the boy if he cannot earn his own living?” Frightened back to reality, Jung immediately got out a textbook and began to study. He suffered three fainting fits in the first hour, but he forced himself to keep going. After that, the fits went away and never came back. Jung had not been faking, but the power of the subconscious mind and the tendency to malinger run deep.

How much of high-functioning autism may be just such a coping mechanism, to avoid facing things which one would rather not face? How much could be powered through with sufficient determination? I suspect the answer is greater than zero.

One hundred years ago, someone of ordinary intelligence who could not complete school or hold down a job would not have been called mentally disabled. He would have been called lazy. His failure to provide for himself would have been taken as a shortcoming of character, not of neurology, and he would have been encouraged to power stoically through the discomfort, and gain greater self-mastery in the process, as Carl Jung did as a child. Taken to an extreme, such expectations can be callous, yet perhaps in our modern society, we have drifted too far in the other direction.

In his book The Myth of Mental Illness , Thomas Szasz cites a passage from Shakespeare’s Macbeth in support of his central thesis. Lady Macbeth, stricken with guilt over having helped her husband commit murder, is descending into madness. Macbeth calls for the doctor, demanding a cure for his wife, but the doctor says, “More needs she the divine than the physician.” In other words, her affliction is moral, not medical.

Unlike Szasz, I would not dismiss all mental illness as a myth. Yet it is true that modern psychiatry has expanded the domain of medicine into realms that were previously considered the province of religion and philosophy. This is doubly dangerous: it can rob those who have been medicalised in this way of dignity and personhood, while simultaneously affording them undue moral licence.

Here, perhaps, autism intersects with what Warren Farrell and others have called the “ boy crisis ”: the increasing tendency of men in their 20s and 30s to fail to complete school, hold down a job, or move out of their parents’ homes. Their struggles are not with learning to speak or use the bathroom, as with the severely autistic, but with building independent and meaningful lives. For some of these young men, an autism diagnosis may simply provide them with permission to avoid the painful task of self-improvement. More need they the divine, perhaps, than the physician.

It is difficult to say where the boundaries of autism should be drawn, but they almost certainly ought to be much narrower than they currently are. Definition creep has cheapened the diagnosis, making it harder to identify those who genuinely need help. Until we can differentiate between the moral and the medical, all the arguments over neurodiversity will lead nowhere.

The Lonely Death of an Ojibway Boy

Charlie Wenjack has come to symbolise the deadly horrors of Canada’s Residential Schools. Unfortunately, many details of his tragic story have been misrepresented in the process.

Stifling Free Speech Online: Australia’s Misinformation Bill

Every censorship regime in history has claimed to be protecting the public. But no regime can have prior knowledge of what is true or good. It can only know what the approved narratives are.

Erdogan’s Hypocrisy

While routinely declaring that Israel’s behaviour toward Hamas is genocidal, Erdogan has consistently denied the real genocides carried out by Turkey.

Investigating the Academy

In a recent speech to University of Toronto scholars, a Quillette editor explained why many of his fellow journalists are reluctant to report on administrative scandals at Canadian universities.

Nostalgia for Confinement

Why are some in Russia and Eastern Europe pining for the communist system that once oppressed them?

From the Blog

More people, more prosperity: the simon abundance index, michal cotler-wunsh: “jew hatred never died, it just mutated”, young women need to stop oversharing online: quillette cetera episode 32, on confected radicalism: quillette cetera episode 31.

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.

On Instagram @quillette

- Administration

Ms Elizabeth Maduhu

Mr nidrosy mlawa ngossa, mr. geofrey itebuka, undergraduate programmes, postgraduate programmes, educational foundations, management and lifelong learning (efmll), educational psychology and curriculum studies (epcs), physical education and sport sciences (pess), university primary school, computer lab, wood workshop, school library, nursery school, subject laboratories, prof. william a.l.anangisye, prof. joyce l.ndalichako, prof. kitila a.k.mkumbo, professor agnes fellicia njabili, papers in education and development vol 37, papers in education and development vol 36, papers in education and development vol 35 (2017), paper in eduction and develpment special issue, paper in education and development vol 37, no 2 (2019), professor abel g.m. ishumi, professor justinian c.j. galabawa.

- Photo Gallery

Announcements

Phd viva-25th april-2024-noela ephraim ndunguru.

Qualifications Attained:

Ms. Noela Ephraim Ndunguru is a PhD candidate (by Thesis) in the Department of Educational Psychology and Curriculum Studies, School of Education, at the University of Dar es Salaam. In 2008, She completed her Bachelor of Education in Educational Psychology. In 2009 She started her Master of Arts in Applied Social Psychology in which was completed in 2011, from the University of Dar es Salaam. Currently, Ms. Noela is an Assistant Lecturer at the Department of Educational Psychology and Curriculum Studies, School of Education at the University of Dar es Salaam. She teaches various courses, including Introduction to Educational Psychology, Theoretical and Practical Perspectives to Counselling, Counselling and Special Needs Education, Psychology of Exceptionalities and Inclusive Education. As a researcher, her interest relies on special needs education, parental engagement in children with special needs, supportive facilities and infrastructure as well as resources for children with special needs.

This qualitative study explored the experiences of parents and teachers in supporting children with autism in Tanzania’s primary schools. Specifically, the study explored the parents’ and teachers’ conceptualisation of autism; determined the challenges parents and teachers encounter in supporting children with autism; and establish the coping strategies parents and teachers employ in managing challenges to supporting children with autism. Using an interpretative phenomenological design, the study was conducted on two special education units to generate the required information. Through criterion purposive sampling, the study drew 27 participants comprising 20 parents and seven teachers of children with autism. Then using semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions, the study collected qualitative data, which was then subjected to thematic analysis. The study found that the conceptualisation on autism from participants covered neurological disorder, abnormality in development and Gods’ wishes. In addition, parents and teachers experienced challenges such as unfavourable treatment from community members, limited skills to manage behaviours of children with autism, caring burden, and inadequate professionals for children with autism. Furthermore, the study found that both parents and teachers searched for new knowledge on autism to have a firm grasp of the condition, created community awareness and sought support in actuating problem-focused coping strategies. Meanwhile, the parents and teachers employed acceptance and involvement in religious activities as emotional-focused coping strategies. Based on these findings, the study underscores a need for effective mechanism to raise community awareness on autism and ensure accessibility and affordability of human and material resources needed to support children with autism. Moreover, there is a need for ongoing training for parents and teachers of children with autism to equip them with updated knowledge and requisite skills to support children with autism in realising their full potential.

Other Announcements

Watch CBS News

Philadelphia Family Court employees trained to improve services for people with autism

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Abstract. This dissertation explored the unique experiences of general education teachers teaching in an. inclusive classroom (which will also be referred to as a "mainstream classroom") with a. combination of students with and without autism (which will also be referred to as "autism. spectrum disorder" and "ASD").

school related stress can access education. The aim was to address a gap in the current literature to identify cases where autistic children have successfully re-engaged and maintained their attendance in education and ascertain what the supportive factors and challenges to their success were. The thesis is organised into three papers.

Introduction. Based on the Salamanca Statement (), children with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) should have access to inclusive education in general schools that are adapted to meet a diverse range of educational needs.Furthermore, The United Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, Article 24 (Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities ...

I dedicate my dissertation to students with autism and cognitive learning disabilities, their families, education researchers, and education program designers. I want to thank my students for teaching me how to be more perceptive and aware of the unique gifts and talents that every student has to offer.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a lifelong condition characterised by social communication difficulties and repetitive behaviours (American Psychiatric Association Citation 2013).The standardised prevalence is around 1.76% of children within schools in England (Roman-Urrestarazu et al. Citation 2021); and there is a high incidence of mental health difficulties (Murphy et al. Citation 2016).

The context and rationale for this research study is discussed, the main aims. and objectives are presented and, finally it briefly outlines the format of the entire study. Chapter Two reviews the literature pertaining to the education and inclusion of children with. autism and other special educational needs.