Freedom Essay for Students and Children

500+ words essay on freedom.

Freedom is something that everybody has heard of but if you ask for its meaning then everyone will give you different meaning. This is so because everyone has a different opinion about freedom. For some freedom means the freedom of going anywhere they like, for some it means to speak up form themselves, and for some, it is liberty of doing anything they like.

Meaning of Freedom

The real meaning of freedom according to books is. Freedom refers to a state of independence where you can do what you like without any restriction by anyone. Moreover, freedom can be called a state of mind where you have the right and freedom of doing what you can think off. Also, you can feel freedom from within.

The Indian Freedom

Indian is a country which was earlier ruled by Britisher and to get rid of these rulers India fight back and earn their freedom. But during this long fight, many people lost their lives and because of the sacrifice of those people and every citizen of the country, India is a free country and the world largest democracy in the world.

Moreover, after independence India become one of those countries who give his citizen some freedom right without and restrictions.

The Indian Freedom Right

India drafted a constitution during the days of struggle with the Britishers and after independence it became applicable. In this constitution, the Indian citizen was given several fundaments right which is applicable to all citizen equally. More importantly, these right are the freedom that the constitution has given to every citizen.

These right are right to equality, right to freedom, right against exploitation, right to freedom of religion¸ culture and educational right, right to constitutional remedies, right to education. All these right give every freedom that they can’t get in any other country.

Value of Freedom

The real value of anything can only be understood by those who have earned it or who have sacrificed their lives for it. Freedom also means liberalization from oppression. It also means the freedom from racism, from harm, from the opposition, from discrimination and many more things.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Freedom does not mean that you violate others right, it does not mean that you disregard other rights. Moreover, freedom means enchanting the beauty of nature and the environment around us.

The Freedom of Speech

Freedom of speech is the most common and prominent right that every citizen enjoy. Also, it is important because it is essential for the all-over development of the country.

Moreover, it gives way to open debates that helps in the discussion of thought and ideas that are essential for the growth of society.

Besides, this is the only right that links with all the other rights closely. More importantly, it is essential to express one’s view of his/her view about society and other things.

To conclude, we can say that Freedom is not what we think it is. It is a psychological concept everyone has different views on. Similarly, it has a different value for different people. But freedom links with happiness in a broadway.

FAQs on Freedom

Q.1 What is the true meaning of freedom? A.1 Freedom truly means giving equal opportunity to everyone for liberty and pursuit of happiness.

Q.2 What is freedom of expression means? A.2 Freedom of expression means the freedom to express one’s own ideas and opinions through the medium of writing, speech, and other forms of communication without causing any harm to someone’s reputation.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

‘Freedom’ Means Something Different to Liberals and Conservatives. Here’s How the Definition Split—And Why That Still Matters

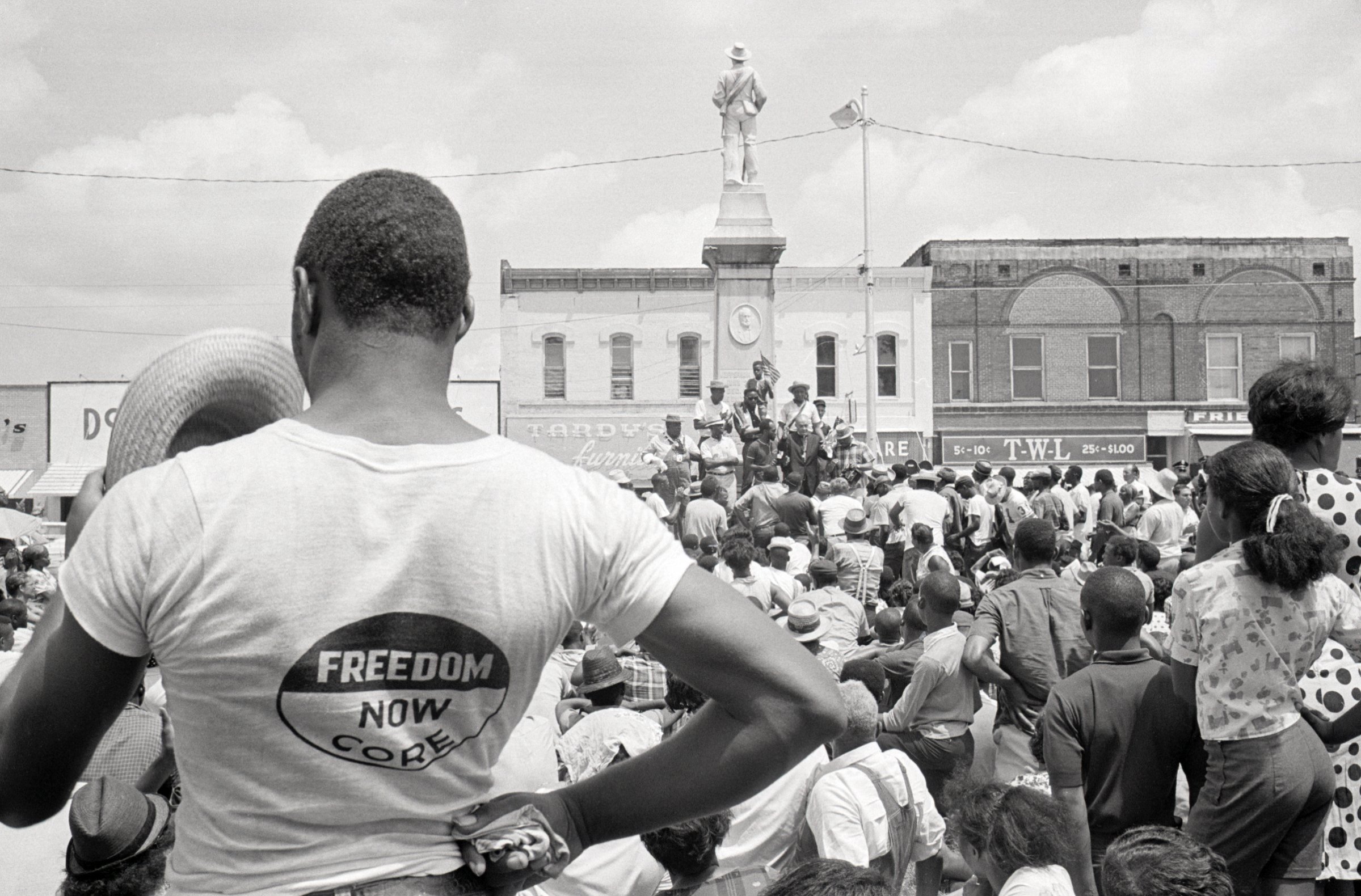

W e tend to think of freedom as an emancipatory ideal—and with good reason. Throughout history, the desire to be free inspired countless marginalized groups to challenge the rule of political and economic elites. Liberty was the watchword of the Atlantic revolutionaries who, at the end of the 18th century, toppled autocratic kings, arrogant elites and ( in Haiti ) slaveholders, thus putting an end to the Old Regime. In the 19th and 20th centuries, Black civil rights activists and feminists fought for the expansion of democracy in the name of freedom, while populists and progressives struggled to put an end to the economic domination of workers.

While these groups had different objectives and ambitions, sometimes putting them at odds with one another, they all agreed that their main goal—freedom—required enhancing the people’s voice in government. When the late Rep. John Lewis called on Americans to “let freedom ring” , he was drawing on this tradition.

But there is another side to the story of freedom as well. Over the past 250 years, the cry for liberty has also been used by conservatives to defend elite interests. In their view, true freedom is not about collective control over government; it consists in the private enjoyment of one’s life and goods. From this perspective, preserving freedom has little to do with making government accountable to the people. Democratically elected majorities, conservatives point out, pose just as much, or even more of a threat to personal security and individual right—especially the right to property—as rapacious kings or greedy elites. This means that freedom can best be preserved by institutions that curb the power of those majorities, or simply by shrinking the sphere of government as much as possible.

This particular way of thinking about freedom was pioneered in the late 18th century by the defenders of the Old Regime. From the 1770s onward, as revolutionaries on both sides of the Atlantic rebelled in the name of liberty, a flood of pamphlets, treatises and newspaper articles appeared with titles such as Some Observations On Liberty , Civil Liberty Asserted or On the Liberty of the Citizen . Their authors vehemently denied that the Atlantic Revolutions would bring greater freedom. As, for instance, the Scottish philosopher Adam Ferguson—a staunch opponent of the American Revolution—explained, liberty consisted in the “security of our rights.” And from that perspective, the American colonists already were free, even though they lacked control over the way in which they were governed. As British subjects, they enjoyed “more security than was ever before enjoyed by any people.” This meant that the colonists’ liberty was best preserved by maintaining the status quo; their attempts to govern themselves could only end in anarchy and mob rule.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

In the course of the 19th century this view became widespread among European elites, who continued to vehemently oppose the advent of democracy. Benjamin Constant, one of Europe’s most celebrated political thinkers, rejected the example of the French revolutionaries, arguing that they had confused liberty with “participation in collective power.” Instead, freedom-lovers should look to the British constitution, where hierarchies were firmly entrenched. Here, Constant claimed, freedom, understood as “peaceful enjoyment and private independence,” was perfectly secure—even though less than five percent of British adults could vote. The Hungarian politician Józseph Eötvös, among many others, agreed. Writing in the wake of the brutally suppressed revolutions that rose against several European monarchies in 1848, he complained that the insurgents, battling for manhood suffrage, had confused liberty with “the principle of the people’s supremacy.” But such confusion could only lead to democratic despotism. True liberty—defined by Eötvös as respect for “well-earned rights”—could best be achieved by limiting state power as much as possible, not by democratization.

In the U.S., conservatives were likewise eager to claim that they, and they alone, were the true defenders of freedom. In the 1790s, some of the more extreme Federalists tried to counter the democratic gains of the preceding decade in the name of liberty. In the view of the staunch Federalist Noah Webster, for instance, it was a mistake to think that “to obtain liberty, and establish a free government, nothing was necessary but to get rid of kings, nobles, and priests.” To preserve true freedom—which Webster defined as the peaceful enjoyment of one’s life and property—popular power instead needed to be curbed, preferably by reserving the Senate for the wealthy. Yet such views were slower to gain traction in the United States than in Europe. To Webster’s dismay, overall, his contemporaries believed that freedom could best be preserved by extending democracy rather than by restricting popular control over government.

But by the end of the 19th century, conservative attempts to reclaim the concept of freedom did catch on. The abolition of slavery, rapid industrialization and mass migration from Europe expanded the agricultural and industrial working classes exponentially, as well as giving them greater political agency. This fueled increasing anxiety about popular government among American elites, who now began to claim that “mass democracy” posed a major threat to liberty, notably the right to property. Francis Parkman, scion of a powerful Boston family, was just one of a growing number of statesmen who raised doubts about the wisdom of universal suffrage, as “the masses of the nation … want equality more than they want liberty.”

William Graham Sumner, an influential Yale professor, likewise spoke for many when he warned of the advent of a new, democratic kind of despotism—a danger that could best be avoided by restricting the sphere of government as much as possible. “ Laissez faire ,” or, in blunt English, “mind your own business,” Sumner concluded, was “the doctrine of liberty.”

Being alert to this history can help us to understand why, today, people can use the same word—“freedom”—to mean two very different things. When conservative politicians like Rand Paul and advocacy groups FreedomWorks or the Federalist Society talk about their love of liberty, they usually mean something very different from civil rights activists like John Lewis—and from the revolutionaries, abolitionists and feminists in whose footsteps Lewis walked. Instead, they are channeling 19th century conservatives like Francis Parkman and William Graham Sumner, who believed that freedom is about protecting property rights—if need be, by obstructing democracy. Hundreds of years later, those two competing views of freedom remain largely unreconcilable.

Annelien de Dijn is the author of Freedom: An Unruly History , available now from Harvard University Press.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Melinda French Gates Is Going It Alone

- Lai Ching-te Is Standing His Ground

- Do Less. It’s Good for You

- There's Something Different About Will Smith

- What Animal Studies Are Revealing About Their Minds—and Ours

- What a Hospice Nurse Wants You to Know About Death

- 15 LGBTQ+ Books to Read for Pride

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

Essays About Freedom: 5 Helpful Examples and 7 Prompts

Freedom seems simple at first; however, it is quite a nuanced topic at a closer glance. If you are writing essays about freedom , read our guide of essay examples and writing prompts.

In a world where we constantly hear about violence, oppression, and war, few things are more important than freedom . It is the ability to act, speak, or think what we want without being controlled or subjected. It can be considered the gateway to achieving our goals , as we can take the necessary steps.

However, freedom is not always “doing whatever we want.” True freedom means to do what is righteous and reasonable, even if there is the option to do otherwise. Moreover, freedom must come with responsibility ; this is why laws are in place to keep society orderly but not too micro-managed, to an extent.

| IMAGE | PRODUCT | |

|---|---|---|

| Grammarly | ||

| ProWritingAid |

5 Examples of Essays About Freedom

1. essay on “freedom” by pragati ghosh, 2. acceptance is freedom by edmund perry, 3. reflecting on the meaning of freedom by marquita herald.

- 4. Authentic Freedom by Wilfred Carlson

5. What are freedom and liberty? by Yasmin Youssef

1. what is freedom, 2. freedom in the contemporary world, 3. is freedom “not free”, 4. moral and ethical issues concerning freedom, 5. freedom vs. security, 6. free speech and hate speech, 7. an experience of freedom.

“Freedom is non denial of our basic rights as humans. Some freedom is specific to the age group that we fall into. A child is free to be loved and cared by parents and other members of family and play around. So this nurturing may be the idea of freedom to a child. Living in a crime free society in safe surroundings may mean freedom to a bit grown up child.”

In her essay, Ghosh briefly describes what freedom means to her. It is the ability to live your life doing what you want. However, she writes that we must keep in mind the dignity and freedom of others. One cannot simply kill and steal from people in the name of freedom ; it is not absolute. She also notes that different cultures and age groups have different notions of freedom . Freedom is a beautiful thing, but it must be exercised in moderation.

“They demonstrate that true freedom is about being accepted, through the scenarios that Ambrose Flack has written for them to endure. In The Strangers That Came to Town, the Duvitches become truly free at the finale of the story. In our own lives, we must ask: what can we do to help others become truly free?”

Perry’s essay discusses freedom in the context of Ambrose Flack’s short story The Strangers That Came to Town : acceptance is the key to being free. When the immigrant Duvitch family moved into a new town, they were not accepted by the community and were deprived of the freedom to live without shame and ridicule. However, when some townspeople reach out, the Duvitches feel empowered and relieved and are no longer afraid to go out and be themselves.

“Freedom is many things, but those issues that are often in the forefront of conversations these days include the freedom to choose, to be who you truly are, to express yourself and to live your life as you desire so long as you do not hurt or restrict the personal freedom of others. I’ve compiled a collection of powerful quotations on the meaning of freedom to share with you, and if there is a single unifying theme it is that we must remember at all times that, regardless of where you live, freedom is not carved in stone, nor does it come without a price.”

In her short essay, Herald contemplates on freedom and what it truly means. She embraces her freedom and uses it to live her life to the fullest and to teach those around her. She values freedom and closes her essay with a list of quotations on the meaning of freedom , all with something in common: freedom has a price. With our freedom , we must be responsible . You might also be interested in these essays about consumerism .

4. Authentic Freedom by Wilfred Carlson

“Freedom demands of one, or rather obligates one to concern ourselves with the affairs of the world around us. If you look at the world around a human being, countries where freedom is lacking, the overall population is less concerned with their fellow man, then in a freer society . The same can be said of individuals, the more freedom a human being has, and the more responsible one acts to other, on the whole.”

Carlson writes about freedom from a more religious perspective, saying that it is a right given to us by God. However, authentic freedom is doing what is right and what will help others rather than simply doing what one wants. If freedom were exercised with “doing what we want” in mind, the world would be disorderly. True freedom requires us to care for others and work together to better society .

“In my opinion, the concepts of freedom and liberty are what makes us moral human beings. They include individual capacities to think, reason, choose and value different situations. It also means taking individual responsibility for ourselves, our decisions and actions. It includes self-governance and self-determination in combination with critical thinking, respect, transparency and tolerance. We should let no stone unturned in the attempt to reach a state of full freedom and liberty, even if it seems unrealistic and utopic.”

Youssef’s essay describes the concepts of freedom and liberty and how they allow us to do what we want without harming others. She notes that respect for others does not always mean agreeing with them. We can disagree, but we should not use our freedom to infringe on that of the people around us. To her, freedom allows us to choose what is good, think critically, and innovate.

7 Prompts for Essays About Freedom

Freedom is quite a broad topic and can mean different things to different people. For your essay, define freedom and explain what it means to you. For example, freedom could mean having the right to vote, the right to work, or the right to choose your path in life. Then, discuss how you exercise your freedom based on these definitions and views.

The world as we know it is constantly changing, and so is the entire concept of freedom . Research the state of freedom in the world today and center your essay on the topic of modern freedom . For example, discuss freedom while still needing to work to pay bills and ask, “Can we truly be free when we cannot choose with the constraints of social norms?” You may compare your situation to the state of freedom in other countries and in the past if you wish.

A common saying goes like this: “Freedom is not free.” Reflect on this quote and write your essay about what it means to you: how do you understand it? In addition, explain whether you believe it to be true or not, depending on your interpretation.

Many contemporary issues exemplify both the pros and cons of freedom ; for example, slavery shows the worst when freedom is taken away, while gun violence exposes the disadvantages of too much freedom . First, discuss one issue regarding freedom and briefly touch on its causes and effects. Then, be sure to explain how it relates to freedom .

Some believe that more laws curtail the right to freedom and liberty. In contrast, others believe that freedom and regulation can coexist, saying that freedom must come with the responsibility to ensure a safe and orderly society . Take a stand on this issue and argue for your position, supporting your response with adequate details and credible sources.

Many people, especially online, have used their freedom of speech to attack others based on race and gender, among other things. Many argue that hate speech is still free and should be protected, while others want it regulated. Is it infringing on freedom ? You decide and be sure to support your answer adequately. Include a rebuttal of the opposing viewpoint for a more credible argumentative essay.

For your essay, you can also reflect on a time you felt free. It could be your first time going out alone, moving into a new house, or even going to another country. How did it make you feel? Reflect on your feelings, particularly your sense of freedom , and explain them in detail.

Check out our guide packed full of transition words for essays .If you are interested in learning more, check out our essay writing tips !

How Do We Define Freedom?

Reilience skills of communication and finding purpose and meaning are necessary..

Posted January 13, 2021

The New Oxford American Dictionary definition of freedom is the “power or right to act, speak or think as one wants without hindrance or restraint.” What is your definition? What does the word "freedom" mean to you? How should freedom be exercised? And do you think that one of the purposes of the government of the United States is to ensure that people in this country have the freedom to act, speak or think as they want?

Realistically, there have always been limits to our freedom. One of the purposes of government is to make laws and to ensure that they are enforced. Relative to freedom, this means that we do not have the freedom to terrorize or endanger others. For example, we have laws against drunk driving. We have laws that require drivers and their passengers to wear a seat belt. In some states, there are laws that require a motorcycle rider to wear a helmet.

Freedom has traditionally been linked with the idea of responsibility. George Bernard Shaw expressed this succinctly, “Liberty means responsibility. That is why most men dread it.” It is an existential concept. To be free means that one has the burden of making choices and decisions. And in making those decisions and choices, we are responsible for both our own and others’ freedom.

The right to act freely and speak freely should end when it endangers others’ rights to do the same. This country is in crisis. Interestingly enough, it is a crisis over how we define freedom in this country. Each one of us needs to ask ourselves our definition of freedom and what limits, if any, should be imposed on our freedom.

This has been demonstrated clearly to us in the last few weeks, specifically in regard to the pandemic. Do Americans have the right to decide if they should wear a mask in public or if they should social distance? Many would say no. If the behavior endangers others, then they do not have the right to engage in it.

Restrictions on an individual's behavior as it relates to the health of other people is not new. If we recognize a public health danger to ourselves and others, we should act to eliminate it. This is why smoking in public places has been banned in most areas in this country. We do not have the freedom to endanger others.

Creating meaning and purpose in our lives and in our institutions is a critical part of being resilient, and God knows we need resilience at this point in time.

Ron Breazeale, Ph.D. , is the author of Duct Tape Isn’t Enough: Survival Skills for the 21st Century as well as the novel Reaching Home .

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Question of the Month

What is freedom, each answer below receives a book. apologies to the entrants not included..

Freedom is the power of a sentient being to exercise its will. Desiring a particular outcome, people bend their thoughts and their efforts toward realizing it – toward a goal. Their capacity to work towards their goal is their freedom. The perfect expression of freedom would be found in someone who, having an unerring idea of what is good, and a similarly unerring idea of how to realize it, then experienced no impediment to pursuing it. This perfect level of freedom might be experienced by a supreme God, or by a Buddha. Personal, internal impairments to freedom manifest mainly as ignorance of what is good, or of the means to attaining it, while external impairments include physical and cultural obstacles to its realization. The bigger and more numerous these impairments are, the lower the level of freedom.

The internal impairments are the most significant. To someone who has a clear understanding of what is good and how to achieve it, the external constraints are comparatively minor. This is illustrated in the novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) by Harriet Beecher Stowe. Uncle Tom, an old slave who has no political (that is, external) liberty, endures injustice and hardship, while his owners enjoy lives of comparative ease. But, though he does sometimes feel sadness and discouragement at the injustices inflicted on himself and others, as a Christian he remains convinced that the real bondage in life consists in sin. So he would not trade places with his masters if it required renouncing his faith and living as they do. To take another angle, the central teaching of the Buddha is liberation from suffering – a freedom which surely all sentient beings desire. The reason we don’t have it yet, he says, is our ignorance . From the Buddhist point of view, even Uncle Tom is ignorant in this sense, although he is still far ahead of his supposed owners.

To become free, then, we must first seek knowledge of the way things really are, and then put ourselves into the correct relationship with that knowledge.

Paul Vitols, North Vancouver, B.C.

Let’s look at this question through three lenses: ethical, metaphysical, and political.

Ethically, according to Epicurus, freedom is not ‘fulfilling all desires’, but instead, being free from vain, unnecessary, or addictive desires. The addict is enslaved even when he obtains his drug; but the virtuous person is free because she doesn’t even desire the drug. Freedom is when the anger, anxiety, greed, hatred, and unnecessary desires drop away in the presence of what’s beloved or sacred. This means that the greatest freedom is ‘freedom from’ something, not ‘freedom to’ do something. (These two types of freedoms correspond to Isaiah Berlin’s famous distinction between ‘negative’ and ‘positive’ types of freedom.)

Metaphysically – as concerning free will – the key may be understanding how human choice can be caused but not determined . In the case of free will, freedom emerges from, but is not reducible to, the activity of the brain. In ways we do not yet understand, humans sometimes have the ability to look over and choose between competing paths. When it comes to consciousness and free will, I trust my introspection that both exist more than I trust the supposedly ‘scientific’ worldviews which have no room for either.

As for politics, the most important freedom is freedom of speech. We need this for truth, good thinking, tolerance, open-mindedness, humility, self-confidence, love, and humor. We discover truth only when we are free to explore alternative ideas. We think well only when people are free to give us feedback. We develop the virtues of tolerance and open-mindedness only when we are free to hear disagreeable ideas. We develop humility when our ideas are tested in a free public arena, while self-confidence arises from those ideas that survive these tests. We love only in freedom as we learn to love others in spite of their ideas, not because of them. And we can laugh deeply only where there is freedom to potentially offend. “Give me freedom or give me death!” is not actually a choice, for we are all dead without freedom.

Paul Stearns, Blinn College, Georgia

There are many kinds of freedom – positive, negative, political, social, etc – but I think that most people would say that generally speaking, freedom is the ability to do what one wants. However, what if what one wants is constrained by external factors, such as alcohol, drugs, or torture? We might also add internal impediments, such as extraordinary emotion, and maybe genetic factors. In these cases, we say that one’s will is not completely free. This view is philosophically called ‘soft determinism’, but it is compatible with having a limited free will.

One interpretation of physical science pushes the idea of constrained will to the ultimate, to complete impotence. This view is often called ‘hard determinism’, and is incompatible with free will. In this view, everyone’s choosing is constrained absolutely by causal physical laws. No one is ever free to choose, this position says, because no one could have willed anything other than what she does will. Hard determinism requires that higher levels of organization above atoms do not add new laws of causation to the strictly physical, but that idea is just a conjecture.

A third view, called ‘indeterminism’, depends on the idea that not all events have a cause. Any uncaused event would seem to just happen. But that won’t do it for freedom. If I make a choice, I want to say that is my choice, not that it happened at random: I made it; I caused it. But how could that be possible?

I would answer that if what I will is the product of my reasoning , then I am the cause, and moreover, that my reasoning is distinct from the causal physical laws of nature. At this point, I have left indeterminism and returned to soft determinism, but with a new perspective. Reasoning raises us above hard determinism because hard determinism means events obeying one set of laws – the physical ones – while reasoning means obeying another set: the laws of logic. This process is subject to human error, and the inputs to it may sometimes be garbage; but amazingly, we often get it right! Our freedom is limited in various further ways; but our ability to choose through reasoning is enough to raise us above being the ludicrous, pathetic, epiphenomenal puppets of hard determinism.

John Talley, Rutherfordton, North Carolina

Freedom can be considered metaphysically and morally. To be free metaphysically means to have some control over one’s thoughts and decisions. One is not reduced to reacting to outside causes. To be free morally means to have the ability to live according to moral standards – to produce some good, and to attain some virtue. Moral freedom means that we can aspire to what is morally good, or resist what is good. As such, the moral life needs an objective standard by which to measure which actions are good and which are bad.

If hard determinism is true then we have no control over our thought and decisions. Rather, everything is explicable in terms of matter, energy, time, and natural laws, and we are but a small part of the cosmic system, which does not have us in mind, and which cannot give freedom. Some determinists, such as Sam Harris, admit as much. Others try to ignore this idea and its amoral implications, since they are so counterintuitive. They call themselves ‘compatibilists’. But if determinism is true, moral freedom disappears for at least two reasons. Firstly, morality requires the metaphysical freedom that determinism rules out. If a child throws a rock through a window, we scold the child, not the rock, because the former had a choice while the latter did not. Ascribing real moral guilt in criminal cases also requires metaphysical freedom, for the same reason. Secondly, if determinism, or even naturalism, is true, there is no objective good that we should pursue. Naturalism is the idea that there is nothing beyond the natural world – no realm of objective values, virtues, and duties, for instance. But if this is true, then there’s no objective good to freely choose. All is reduced to natural properties, which have no moral value. Morality dissolves away into chemistry and conditioning.

Since metaphysical freedom exists (we know this because we experience choosing) and moral freedom is possible (since some moral goals are objectively good), we need a worldview which allows both kinds of freedom. It must accept that human beings are able to transcend the causal confines of the material cosmos. It must also grant humans the ability to act with respect to objective moral values. Judeo-Christian theism is one worldview which fulfils these needs, given its claim that humans are free moral agents who answer to (God’s) objective moral standards.

Douglas Groothuis, Professor of Philosophy, Denver Seminary

According to Hannah Arendt, thinking about freedom is a hopeless enterprise, since one cannot conceive of freedom without immediately being caught in a contradiction. This is that we are free and hence responsible, but inner freedom (free will) cannot fully develop from the natural principles of causality. In the physical world, everything happens according to necessity governed by causality. So, assuming that we are entirely material beings governed by the laws of physics, it is impossible to even consider the idea of human freedom. To say that we are free beings, by contrast, automatically assumes that we are a free cause – that is, we’re able to cause something with our will that is itself without cause in the physical world! This idea of ‘transcendental will’, first introduced by Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), says that free will must be non-physical in order to operate – in other words, not part of the causal system of the physical world. Yet even this doesn’t fully address the issue of freedom. In order for freedom to have any meaning, one has to also act through something in the external world, thereby interrupting a necessary, physical, chain of causes. However, to act is to use a fundamentally different faculty than the one we use to think with. Thought cannot extend itself to the realm of action. This gap between action and thought – a gap through which freedom cannot pass – reveals that it is impossible to have a theoretical grasp of freedom! So all in all, the traditional understanding of free will is an incoherent conception.

Actually, politics and law both assume freedom to be a self-evident truth, especially in a modern liberal democracy. Indeed, the very evidence of human freedom, the tangible transformation that happens in the material world due to our ideas, flows best from our collective action in this public realm.

Shinyoung Choi, Centreville, Virginia

“I will slay the children I have borne!” are the words of Medea in Euripides’ play of that name. Medea takes vengeance on her husband Jason for betraying her for another woman, by murdering her own children and Jason’s new wife. The tragedy of this drama relates well to the question of human freedom. Medea showed by her actions that she was free to do things which by their nature would normally be assumed to be outside the realm of possibility. Having the ability to choose one thing over another on the basis of desire is what Immanuel Kant dismissively called ‘the Idea of Freedom’. Kant, though, asserts a different definition of freedom. He formulated a positive conception of freedom as the free capacity for choice that characterizes the essence of being human. However, the radical nature of this freedom implies that we are free even to choose the option of being free or unfree.

Kant argued of freedom that “insofar as it is not restrained under certain rules, it is the most terrible thing there could be.” Instead, to realize its true potential value, freedom must be ‘consistent with itself’. That is to say, my use of freedom must be consistent with everyone else’s use of their freedom. This law of consistency is established by reason, since reason requires consistency in its ideas. Indeed, Kant argues that an action is truly free only if it is motivated by reason alone. This ability to be motivated by reason alone Kant called ‘the autonomy of the will’. If, on the other hand, we choose to subjugate our reason to our desires and passions, we become slaves to our animalistic instincts and are not acting freely. So, by this argument, freedom is the ability to be governed by reason to act in accordance with and for the sake of the law of freedom . Thus, freedom is not what we want to do, but what we ought to do. Should we ignore the laws of nature, we would cease to exist as natural beings; but should we ignore our reason and disobey the law of freedom, we would cease to be human beings.

Medea, just like all human beings, had freedom of choice. She chose to make her reason the slave of her passion for revenge, and thus lost her true freedom. I believe that the real tragedy is not in that we as human beings have the freedom of choice, but that we freely choose to be unfree. Without true freedom, we lose our humanity and bring suffering on ourselves – as illustrated in this and all the other tragedies of drama and of history.

Nella Leontieva, Sydney

In an article I read just after Christmas, but which was first published in 1974, the science fiction author Ursula Le Guin says “To be free, after all, is not to be undisciplined.” Two weeks later, by chance I came across a quotation, apparently from Aristotle: “Through discipline comes freedom.” Both statements struck me as intuitively obvious, to the extent that to the question ‘What is Freedom?’ I would answer ‘Freedom is discipline’. However, I cannot ground this approach further except in the existentialist sense, in which sense I would say it is fundamental.

How can this inversion of freedom be justified? Broadly, freedom is the ability to choose. But no-one, or nothing, can choose in isolation – there are always constraints. How much freedom somebody actually has boils down to the nature of these constraints and how the individual deals with them. Constraints impose to varying degrees the requirement for an individual to discipline their choices. For example, a person might be constrained by a political system, and discipline themselves to act circumspectly within the confines of that system. They might consider that they physically have the freedom to act otherwise, such as to take part in a demonstration, but are constrained by other priorities. For example, they need to keep their job in order to feed their children, so that they choose not to use that freedom. Such an individual may still regard themselves as having freedom in other contexts, and ultimately may always regard their mind as free. Nothing external can constrain what one thinks: freedom concerns what we do with those thoughts.

Lindsay Dannatt, Amesbury, Wiltshire

Freedom is being able to attempt to do what we desire to do, with reasonable knowledge, which no-one can or will obstruct us from achieving through an arbitrary exercise of their will .

To clarify this, let me distinguish between usual and unusual desires. The usual ones are desires that anyone can reasonably expect to be satisfied as part of everyday life, while the unusual are desires no-one can expect to be satisfied. Examples of a usual desire include wanting to buy groceries from a shop, or wanting to earn enough money to pay your bills, while an example of an unusual desire is wanting to headline the Glastonbury Festival. Although it’s certainly the case that people might prevent me from achieving that goal through an arbitrary exercise of their will, it is not at all guaranteed that a lack of this impediment will result in my achieving the goal. We cannot claim a lack of freedom on the basis that our unusual desires go unsatisfied. Meanwhile, it is almost certainly guaranteed that I can shop for groceries if no-one else attempts to stop me through arbitrary actions.

An arbitrary act is an act carried out according to no concrete or explicit set of rules applicable to all. A person might invent their own rules and act according to them, but this is still arbitrary because their act is not mediated by a set of rules applicable to all. On these same lines, a person in a dictatorship is not free, because although there may be a set of rules ostensibly applicable to all, the application of these rules is at the discretion of the political leader or government. Contrariwise, a person can experience a just law as unfair and feel that their freedom is decreased when in fact the full freedom of all depends on that law. For example, a law against vandalism may be experienced by some political activists as unfair, or even unjust, but it applies equally to everyone. If this latter condition is not met, people are not free.

Let me add that we cannot define freedom as ‘the absence of constraint or interference’, since we cannot know that interference isn’t taking place. We can conceive of hard-to-see manipulative systems which evade even our most careful investigation. And their non-existence is equally imperceptible to us.

Alastair Gray, Brighton

Freedom is an amalgam of dreams, strivings, and controlled premeditated actions which yield repeatable demonstrable successes in the world . There is collective freedom and individual freedom . I’ll only consider individual freedom here, but with minimal tweaking this concept could apply to collective freedom, too.

Every baby is born with at least one freedom – the ability to find, suckle at, and leave the breast. Other actions are doable, but are ragged and out of control. Over time more freedom is achieved. How does that happen? First, through crying, cooing, smiling, the newborn learns to communicate. First word, first step, first bike ride – all are major freedom breakthroughs. All are building blocks to future successes.

Let a dot on a page represent a specific individual and a closed line immediately about the dot represent a fence, limiting freedom. Freedom is a push upon this fence. A newly gained freedom forces the fence to back even further away from the dot, expanding the area enclosed about the individual. This area depicts the accumulated freedoms gained in life. The shape is random, not circular, since it is governed by the diversity and complexity of the individual’s successes. If Spanish is not learned, freedom to use Spanish was not gained. But if freedom with the violin is gained, that freedom would force the fence to retreat, adding a ‘violin-shaped’ bulge of freedom. The broader the skill, the wider the bulge. The greater the complexity, the deeper the bulge.

The fence limiting each individual’s freedom is unique. Its struts consist of the individual’s DNA, location, historical time frame, the community morays, the laws of the land, and any barrier which inhibits the individual’s goals. At an individual’s maximum sustained effort to be free from their constraints, the fence becomes razor wire. Continued sustained effort at the edge, without breaking through or expanding one’s territory, leaves the individual shattered, bleeding, and possibly broken.

Years fly, in time the hair greys or is lost, along with the greying of memory and other mental and physical abilities. Freedom weakens. Strength to hold back the fence’s elasticity weakens as well. So begins freedom’s loss in a step-by-step retreat.

Bob Preston, Winnipeg, Manitoba

Freedom is an illusion. “Man is condemned to be free; because once thrown into the world, he is responsible for everything he does,” wrote Jean-Paul Sartre. But man is not so much condemned to be free as condemned to bear the consequences of his choices and to take responsibility for his actions. This is not freedom . Freedom differs from free will. We do have choice , no matter what; but it is very questionable whether choosing between several unattractive options corresponds with actual freedom . Freedom would be the situation in which our choices, made through our free will, have no substantial consequences, which, say, limit our choices. This is impossible.

Man has a free will, but that does not make him ultimately free. On the contrary, our choices are mainly driven by survival in a competitive environment. Moreover, as long as people live with others, their freedom is limited by morals, laws, obligations and responsibilities – and that’s in countries where human rights are being respected. So all the freedoms we experience or aspire to are relative: freedom of opinion, freedom of action, freedom to choose a career, residence, or partner. Every choice necessarily leads to a commitment, and thus to obligations and responsibilities. These in turn lead to limitations; but also to meaning. The relative freedom to make a positive contribution to the world gives life meaning, and that is what man ultimately seeks.

Caroline Deforche, Lichtervelde, Belgium

Freedom? Bah, humbug! When humanity goes extinct, there will be no such thing as freedom. In the meantime, it is never more than a minimized concession from a grudging status quo. When it comes to dealing with each other, we are wrenching, scraping, clutching, covetous creatures, hard as a flint from which no generous fire glows. The problem with discerning this general truth is, not everyone is paid enough to be as true to human nature as merchant bankers, and society bludgeons the rest of us with rules that determine who does the squeezing in any given social structure – be it a family, a club, a company, or the state.

If this perspective seems to be a pessimistic denial of the ‘human spirit’, consider slavery and serfdom: both are means of squeezing others that their given society’s status quo condones. And, moreover, both states still exist, on the fringes – proving how little stands between humanity and savagery. The moral alternatives demand faith in the dubious artifice of absolute references: God(s), Ancestors, Equality, the Greater Good… However, if your preferred moral reference is at odds with the status quo’s, then you will feel you’re being denied your ‘freedom’.

So, freedom depends on the status quo, which, in turn, depends on whichever monoliths justify it. Absolute monarchies have often derived their power from the supposed will of God. Here there can be no freedom – just loyalty . Communism bases its moral claim on monolithic Equality, where the equal individuals cannot themselves be trusted with something as lethal as freedom, so it is held back by the Party. Capitalism says the squeezing should be done by those who succeed at accumulating economic spoils, and their attendant cast of amoral deal-brokers. Which is all fine. No system is perfect; and freedom is whatever exception you can wrench back from an unfavourable status quo. To win freedom, you must either negotiate or revolt. In turn, a successful status quo adapts to the ever-changing dynamics of who holds the power, and the will, to squeeze others. So freedom is a spectral illusion. If you’re lucky, you might catch a glimpse of it; but then it’s gone, wrenched back out of your feeble grasp.

Andrew Wrigley, York

As sky, so too water As air, so swims the silver cloud As body, so too the human mind is free To act to love to live to dream to be As circumstance reflects serendipity ‘I am the architect of my own destiny’ So say Sartre, Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty. This strange friend and foe: freedom Is mine, is me A mind to mirror to will to learn to choose For as living erodes all roads and thee ‘You are the architect of your own history’ So say the existentialists in a Paris café, For freedom, like sky, cloud, rain, and air Is what it means to be. Yes, thinkers, dreamers, disbelievers This is freedom: At any moment we can change our course Outrun contingency, outwit facticity Petition our thrownness to let us be For we are the architects of our own lives. This is the meaning of being free.

Bianca Laleh, Totnes, Devon

Next Question of the Month

The next question is: What’s the Most Fundamental Value? Please give and justify your answer in less than 400 words. The prize is a semi-random book from our book mountain. Subject lines should be marked ‘Question of the Month’, and must be received by 22nd June 2021. If you want a chance of getting a book, please include your physical address.

This site uses cookies to recognize users and allow us to analyse site usage. By continuing to browse the site with cookies enabled in your browser, you consent to the use of cookies in accordance with our privacy policy . X

Home — Essay Samples — Literature — The Glass Castle — What Freedom Means To Me

What Freedom Means to Me

- Categories: The Glass Castle

About this sample

Words: 634 |

Published: Mar 14, 2024

Words: 634 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Literature

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

4 pages / 1725 words

3.5 pages / 1498 words

7 pages / 3276 words

6 pages / 2729 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on The Glass Castle

The Glass Castle, a memoir written by Jeannette Walls, is a compelling narrative that explores the author's tumultuous and often traumatic childhood. Throughout the memoir, Walls uses various symbols to convey deeper meanings [...]

In Jeannette Walls' memoir, The Glass Castle, symbolism is used to enhance the reader's understanding of the complex relationships, hardships, and resilience portrayed in the story. The use of various symbols such as the [...]

The character of Rex Walls in Jeanette Walls' memoir "The Glass Castle" is a complex and intriguing figure. Throughout the book, Rex's actions and motivations reveal a man who is both admirable and deeply flawed. This essay aims [...]

Jeannette Walls' memoir, The Glass Castle, provides a poignant and raw portrayal of poverty and its devastating impact on a family. The memoir chronicles Walls' childhood, growing up in extreme poverty with dysfunctional parents [...]

Despite being faced with adverse conditions while growing up, humankind possesses resilience and the capacity to accept and forgive those responsible. In The Glass Castle (2005) by Jeannette Walls, Walls demonstrates a [...]

Alcoholism is one of the most commonly seen problems in familial environments. It not only affects the health of the person consuming the alcohol, but also has an impact on the wellbeing of those surrounding him or her. [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Positive and Negative Liberty

Negative liberty is the absence of obstacles, barriers or constraints. One has negative liberty to the extent that actions are available to one in this negative sense. Positive liberty is the possibility of acting — or the fact of acting — in such a way as to take control of one’s life and realize one’s fundamental purposes. While negative liberty is usually attributed to individual agents, positive liberty is sometimes attributed to collectivities, or to individuals considered primarily as members of given collectivities.

The idea of distinguishing between a negative and a positive sense of the term ‘liberty’ goes back at least to Kant, and was examined and defended in depth by Isaiah Berlin in the 1950s and ’60s. Discussions about positive and negative liberty normally take place within the context of political and social philosophy. They are distinct from, though sometimes related to, philosophical discussions about free will . Work on the nature of positive liberty often overlaps, however, with work on the nature of autonomy .

As Berlin showed, negative and positive liberty are not merely two distinct kinds of liberty; they can be seen as rival, incompatible interpretations of a single political ideal. Since few people claim to be against liberty, the way this term is interpreted and defined can have important political implications. Political liberalism tends to presuppose a negative definition of liberty: liberals generally claim that if one favors individual liberty one should place strong limitations on the activities of the state. Critics of liberalism often contest this implication by contesting the negative definition of liberty: they argue that the pursuit of liberty understood as self-realization or as self-determination (whether of the individual or of the collectivity) can require state intervention of a kind not normally allowed by liberals.

Many authors prefer to talk of positive and negative freedom . This is only a difference of style, and the terms ‘liberty’ and ‘freedom’ are normally used interchangeably by political and social philosophers. Although some attempts have been made to distinguish between liberty and freedom (Pitkin 1988; Williams 2001; Dworkin 2011), generally speaking these have not caught on. Neither can they be translated into other European languages, which contain only the one term, of either Latin or Germanic origin (e.g. liberté, Freiheit), where English contains both.

1. Two Concepts of Liberty

2. the paradox of positive liberty, 3.1 positive liberty as content-neutral, 3.2 republican liberty, 4. one concept of liberty: freedom as a triadic relation, 5. the analysis of constraints: their types and their sources, 6. the concept of overall freedom, 7. is the distinction still useful, introductory works, other works, other internet resources, related entries.

Imagine you are driving a car through town, and you come to a fork in the road. You turn left, but no one was forcing you to go one way or the other. Next you come to a crossroads. You turn right, but no one was preventing you from going left or straight on. There is no traffic to speak of and there are no diversions or police roadblocks. So you seem, as a driver, to be completely free. But this picture of your situation might change quite dramatically if we consider that the reason you went left and then right is that you’re addicted to cigarettes and you’re desperate to get to the tobacconists before it closes. Rather than driving , you feel you are being driven , as your urge to smoke leads you uncontrollably to turn the wheel first to the left and then to the right. Moreover, you’re perfectly aware that your turning right at the crossroads means you’ll probably miss a train that was to take you to an appointment you care about very much. You long to be free of this irrational desire that is not only threatening your longevity but is also stopping you right now from doing what you think you ought to be doing.

This story gives us two contrasting ways of thinking of liberty. On the one hand, one can think of liberty as the absence of obstacles external to the agent. You are free if no one is stopping you from doing whatever you might want to do. In the above story you appear, in this sense, to be free. On the other hand, one can think of liberty as the presence of control on the part of the agent. To be free, you must be self-determined, which is to say that you must be able to control your own destiny in your own interests. In the above story you appear, in this sense, to be unfree: you are not in control of your own destiny, as you are failing to control a passion that you yourself would rather be rid of and which is preventing you from realizing what you recognize to be your true interests. One might say that while on the first view liberty is simply about how many doors are open to the agent, on the second view it is more about going through the right doors for the right reasons.

In a famous essay first published in 1958, Isaiah Berlin called these two concepts of liberty negative and positive respectively (Berlin 1969). [ 1 ] The reason for using these labels is that in the first case liberty seems to be a mere absence of something (i.e. of obstacles, barriers, constraints or interference from others), whereas in the second case it seems to require the presence of something (i.e. of control, self-mastery, self-determination or self-realization). In Berlin’s words, we use the negative concept of liberty in attempting to answer the question “What is the area within which the subject — a person or group of persons — is or should be left to do or be what he is able to do or be, without interference by other persons?”, whereas we use the positive concept in attempting to answer the question “What, or who, is the source of control or interference that can determine someone to do, or be, this rather than that?” (1969, pp. 121–22).

It is useful to think of the difference between the two concepts in terms of the difference between factors that are external and factors that are internal to the agent. While theorists of negative freedom are primarily interested in the degree to which individuals or groups suffer interference from external bodies, theorists of positive freedom are more attentive to the internal factors affecting the degree to which individuals or groups act autonomously. Given this difference, one might be tempted to think that a political philosopher should concentrate exclusively on negative freedom, a concern with positive freedom being more relevant to psychology or individual morality than to political and social institutions. This, however, would be premature, for among the most hotly debated issues in political philosophy are the following: Is the positive concept of freedom a political concept? Can individuals or groups achieve positive freedom through political action? Is it possible for the state to promote the positive freedom of citizens on their behalf? And if so, is it desirable for the state to do so? The classic texts in the history of western political thought are divided over how these questions should be answered: theorists in the classical liberal tradition, like Benjamin Constant, Wilhelm von Humboldt, Herbert Spencer, and J.S. Mill, are typically classed as answering ‘no’ and therefore as defending a negative concept of political freedom; theorists that are critical of this tradition, like Jean-Jacques Rousseau, G.W.F. Hegel, Karl Marx and T.H. Green, are typically classed as answering ‘yes’ and as defending a positive concept of political freedom.

In its political form, positive freedom has often been thought of as necessarily achieved through a collectivity. Perhaps the clearest case is that of Rousseau’s theory of freedom, according to which individual freedom is achieved through participation in the process whereby one’s community exercises collective control over its own affairs in accordance with the ‘general will’. Put in the simplest terms, one might say that a democratic society is a free society because it is a self-determined society, and that a member of that society is free to the extent that he or she participates in its democratic process. But there are also individualist applications of the concept of positive freedom. For example, it is sometimes said that a government should aim actively to create the conditions necessary for individuals to be self-sufficient or to achieve self-realization. The welfare state has sometimes been defended on this basis, as has the idea of a universal basic income. The negative concept of freedom, on the other hand, is most commonly assumed in liberal defences of the constitutional liberties typical of liberal-democratic societies, such as freedom of movement, freedom of religion, and freedom of speech, and in arguments against paternalist or moralist state intervention. It is also often invoked in defences of the right to private property. This said, some philosophers have contested the claim that private property necessarily enhances negative liberty (Cohen 1995, 2006), and still others have tried to show that negative liberty can ground a form of egalitarianism (Steiner 1994).

After Berlin, the most widely cited and best developed analyses of the negative concept of liberty include Hayek (1960), Day (1971), Oppenheim (1981), Miller (1983) and Steiner (1994). Among the most prominent contemporary analyses of the positive concept of liberty are Milne (1968), Gibbs (1976), C. Taylor (1979) and Christman (1991, 2005).

Many liberals, including Berlin, have suggested that the positive concept of liberty carries with it a danger of authoritarianism. Consider the fate of a permanent and oppressed minority. Because the members of this minority participate in a democratic process characterized by majority rule, they might be said to be free on the grounds that they are members of a society exercising self-control over its own affairs. But they are oppressed, and so are surely unfree. Moreover, it is not necessary to see a society as democratic in order to see it as self-controlled; one might instead adopt an organic conception of society, according to which the collectivity is to be thought of as a living organism, and one might believe that this organism will only act rationally, will only be in control of itself, when its various parts are brought into line with some rational plan devised by its wise governors (who, to extend the metaphor, might be thought of as the organism’s brain). In this case, even the majority might be oppressed in the name of liberty.

Such justifications of oppression in the name of liberty are no mere products of the liberal imagination, for there are notorious historical examples of their endorsement by authoritarian political leaders. Berlin, himself a liberal and writing during the cold war, was clearly moved by the way in which the apparently noble ideal of freedom as self-mastery or self-realization had been twisted and distorted by the totalitarian dictators of the twentieth century — most notably those of the Soviet Union — so as to claim that they, rather than the liberal West, were the true champions of freedom. The slippery slope towards this paradoxical conclusion begins, according to Berlin, with the idea of a divided self. To illustrate: the smoker in our story provides a clear example of a divided self, for she is both a self that desires to get to an appointment and a self that desires to get to the tobacconists, and these two desires are in conflict. We can now enrich this story in a plausible way by adding that one of these selves — the keeper of appointments — is superior to the other: the self that is a keeper of appointments is thus a ‘higher’ self, and the self that is a smoker is a ‘lower’ self. The higher self is the rational, reflecting self, the self that is capable of moral action and of taking responsibility for what she does. This is the true self, for rational reflection and moral responsibility are the features of humans that mark them off from other animals. The lower self, on the other hand, is the self of the passions, of unreflecting desires and irrational impulses. One is free, then, when one’s higher, rational self is in control and one is not a slave to one’s passions or to one’s merely empirical self. The next step down the slippery slope consists in pointing out that some individuals are more rational than others, and can therefore know best what is in their and others’ rational interests. This allows them to say that by forcing people less rational than themselves to do the rational thing and thus to realize their true selves, they are in fact liberating them from their merely empirical desires. Occasionally, Berlin says, the defender of positive freedom will take an additional step that consists in conceiving of the self as wider than the individual and as represented by an organic social whole — “a tribe, a race, a church, a state, the great society of the living and the dead and the yet unborn”. The true interests of the individual are to be identified with the interests of this whole, and individuals can and should be coerced into fulfilling these interests, for they would not resist coercion if they were as rational and wise as their coercers. “Once I take this view”, Berlin says, “I am in a position to ignore the actual wishes of men or societies, to bully, oppress, torture in the name, and on behalf, of their ‘real’ selves, in the secure knowledge that whatever is the true goal of man ... must be identical with his freedom” (Berlin 1969, pp. 132–33).

Those in the negative camp try to cut off this line of reasoning at the first step, by denying that there is any necessary relation between one’s freedom and one’s desires. Since one is free to the extent that one is externally unprevented from doing things, they say, one can be free to do what one does not desire to do. If being free meant being unprevented from realizing one’s desires, then one could, again paradoxically, reduce one’s unfreedom by coming to desire fewer of the things one is unfree to do. One could become free simply by contenting oneself with one’s situation. A perfectly contented slave is perfectly free to realize all of her desires. Nevertheless, we tend to think of slavery as the opposite of freedom. More generally, freedom is not to be confused with happiness, for in logical terms there is nothing to stop a free person from being unhappy or an unfree person from being happy. The happy person might feel free, but whether they are free is another matter (Day, 1970). Negative theorists of freedom therefore tend to say not that having freedom means being unprevented from doing as one desires, but that it means being unprevented from doing whatever one might desire to do (Steiner 1994. Cf. Van Parijs 1995; Sugden 2006).

Some theorists of positive freedom bite the bullet and say that the contented slave is indeed free — that in order to be free the individual must learn, not so much to dominate certain merely empirical desires, but to rid herself of them. She must, in other words, remove as many of her desires as possible. As Berlin puts it, if I have a wounded leg ‘there are two methods of freeing myself from pain. One is to heal the wound. But if the cure is too difficult or uncertain, there is another method. I can get rid of the wound by cutting off my leg’ (1969, pp. 135–36). This is the strategy of liberation adopted by ascetics, stoics and Buddhist sages. It involves a ‘retreat into an inner citadel’ — a soul or a purely noumenal self — in which the individual is immune to any outside forces. But this state, even if it can be achieved, is not one that liberals would want to call one of freedom, for it again risks masking important forms of oppression. It is, after all, often in coming to terms with excessive external limitations in society that individuals retreat into themselves, pretending to themselves that they do not really desire the worldly goods or pleasures they have been denied. Moreover, the removal of desires may also be an effect of outside forces, such as brainwashing, which we should hardly want to call a realization of freedom.

Because the concept of negative freedom concentrates on the external sphere in which individuals interact, it seems to provide a better guarantee against the dangers of paternalism and authoritarianism perceived by Berlin. To promote negative freedom is to promote the existence of a sphere of action within which the individual is sovereign, and within which she can pursue her own projects subject only to the constraint that she respect the spheres of others. Humboldt and Mill, both advocates of negative freedom, compared the development of an individual to that of a plant: individuals, like plants, must be allowed to grow, in the sense of developing their own faculties to the full and according to their own inner logic. Personal growth is something that cannot be imposed from without, but must come from within the individual.

3. Two Attempts to Create a Third Way

Critics, however, have objected that the ideal described by Humboldt and Mill looks much more like a positive concept of liberty than a negative one. Positive liberty consists, they say, in exactly this growth of the individual: the free individual is one that develops, determines and changes her own desires and interests autonomously and from within. This is not liberty as the mere absence of obstacles, but liberty as autonomy or self-realization. Why should the mere absence of state interference be thought to guarantee such growth? Is there not some third way between the extremes of totalitarianism and the minimal state of the classical liberals — some non-paternalist, non-authoritarian means by which positive liberty in the above sense can be actively promoted?

Much of the more recent work on positive liberty has been motivated by a dissatisfaction with the ideal of negative liberty combined with an awareness of the possible abuses of the positive concept so forcefully exposed by Berlin. John Christman (1991, 2005, 2009, 2013), for example, has argued that positive liberty concerns the ways in which desires are formed — whether as a result of rational reflection on all the options available, or as a result of pressure, manipulation or ignorance. What it does not regard, he says, is the content of an individual’s desires. The promotion of positive freedom need not therefore involve the claim that there is only one right answer to the question of how a person should live, nor need it allow, or even be compatible with, a society forcing its members into given patterns of behavior. Take the example of a Muslim woman who claims to espouse the fundamentalist doctrines generally followed by her family and the community in which she lives. On Christman’s account, this person is positively unfree if her desire to conform was somehow oppressively imposed upon her through indoctrination, manipulation or deceit. She is positively free, on the other hand, if she arrived at her desire to conform while aware of other reasonable options and she weighed and assessed these other options rationally. Even if this woman seems to have a preference for subservient behavior, there is nothing necessarily freedom-enhancing or freedom-restricting about her having the desires she has, since freedom regards not the content of these desires but their mode of formation. On this view, forcing her to do certain things rather than others can never make her more free, and Berlin’s paradox of positive freedom would seem to have been avoided.

This more ‘procedural’ account of positive liberty allows us to point to kinds of internal constraint that seem too fall off the radar if we adopt only negative concept. For example, some radical political theorists believe it can help us to make sense of forms of oppression and structural injustice that cannot be traced to overt acts of prevention or coercion. On the one hand, in agreement with Berlin, we should recognize the dangers of that come with promoting the values or interests of a person’s ‘true self’ in opposition to what they manifestly desire. Thus, the procedural account avoids all reference to a ‘true self’. On the other, we should recognize that people’s actual selves are inevitably formed in a social context and that their values and senses of identity (for example, in terms of gender or race or nationality) are shaped by cultural influences. In this sense, the self is ‘socially constructed’, and this social construction can itself occur in oppressive ways. The challenge, then, is to show how a person’s values can be thus shaped but without the kind of oppressive imposition or manipulation that comes not only from political coercion but also, more subtly, from practices or institutions that stigmatize or marginalize certain identities or that attach costs to the endorsement of values deviating from acceptable norms, for these kinds of imposition or manipulation can be just another way of promoting a substantive ideal of the self. And this was exactly the danger against which Berlin was warning, except that the danger is less visible and can be created unintentionally (Christman 2013, 2015, 2021; Hirschmann 2003, 2013; Coole 2013).

While this theory of positive freedom undoubtedly provides a tool for criticizing the limiting effects of certain practices and institutions in contemporary liberal societies, it remains to be seen what kinds of political action can be pursued in order to promote content-neutral positive liberty without encroaching on any individual’s rightful sphere of negative liberty. Thus, the potential conflict between the two ideals of negative and positive freedom might survive Christman’s alternative analysis, albeit in a milder form. Even if we rule out coercing individuals into specific patterns of behavior, a state interested in promoting content-neutral positive liberty might still have considerable space for intervention aimed at ‘public enlightenment’, perhaps subsidizing some kinds of activities (in order to encourage a plurality of genuine options) and financing such intervention through taxation. Liberals might criticize this kind of intervention on anti-paternalist grounds, objecting that such measures will require the state to use resources in ways that the supposedly heteronomous individuals, if left to themselves, might have chosen to spend in other ways. In other words, even in its content-neutral form, the ideal of positive freedom might still conflict with the liberal idea of respect for persons, one interpretation of which involves viewing individuals from the outside and taking their choices at face value. From a liberal point of view, the blindness to internal constraints can be intentional (Carter 2011a). Some liberals will make an exception to this restriction on state intervention in the case of the education of children, in such a way as to provide for the active cultivation of open minds and rational reflection. Even here, however, other liberals will object that the right to negative liberty includes the right to decide how one’s children should be educated.

Is it necessary to refer to internal constraints in order to make sense of the phenomena of oppression and structural injustice? Some might contest this view, or say that it is true only up to a point, for there are at least two reasons for thinking that the oppressed are lacking in negative liberty. First, while Berlin himself equated economic and social disadvantages with natural disabilities, claiming that neither represented constraints on negative liberty but only on personal abilities, many theorists of negative liberty disagree: if I lack the money to buy a jacket from a clothes shop, then any attempt on my part to carry away the jacket is likely to meet with preventive actions or punishment on the part of the shop keeper or the agents of the state. This is a case of interpersonal interference, not merely of personal inability. In the normal circumstances of a market economy, purchasing power is indeed a very reliable indicator of how far other people will stop you from doing certain things if you try. It is therefore strongly correlated with degrees of negative freedom (Cohen 1995, 2011; Waldron 1993; Carter 2007; Grant 2013). Thus, while the promotion of content-neutral positive liberty might imply the transfer of certain kinds of resources to members of disadvantaged groups, the same might be true of the promotion of negative liberty. Second, the negative concept of freedom can be applied directly to disadvantaged groups as well as to their individual members. Some social structures may be such as to tolerate the liberation of only a limited number of members of a given group. G.A. Cohen famously focused on the case proletarians who can escape their condition by successfully setting up a business of their own though a mixture of hard work and luck. In such cases, while each individual member of the disadvantaged group might be negatively free in the sense of being unprevented from choosing the path of liberation, the freedom of the individual is conditional on the unfreedom of the majority of the rest of the group, since not all can escape in this way. Each individual member of the class therefore partakes in a form of collective negative unfreedom (Cohen 1988, 2006; for discussion see Mason 1996; Hindricks 2008; Grant 2013; Schmidt 2020).