Wellesley College Commencement Address

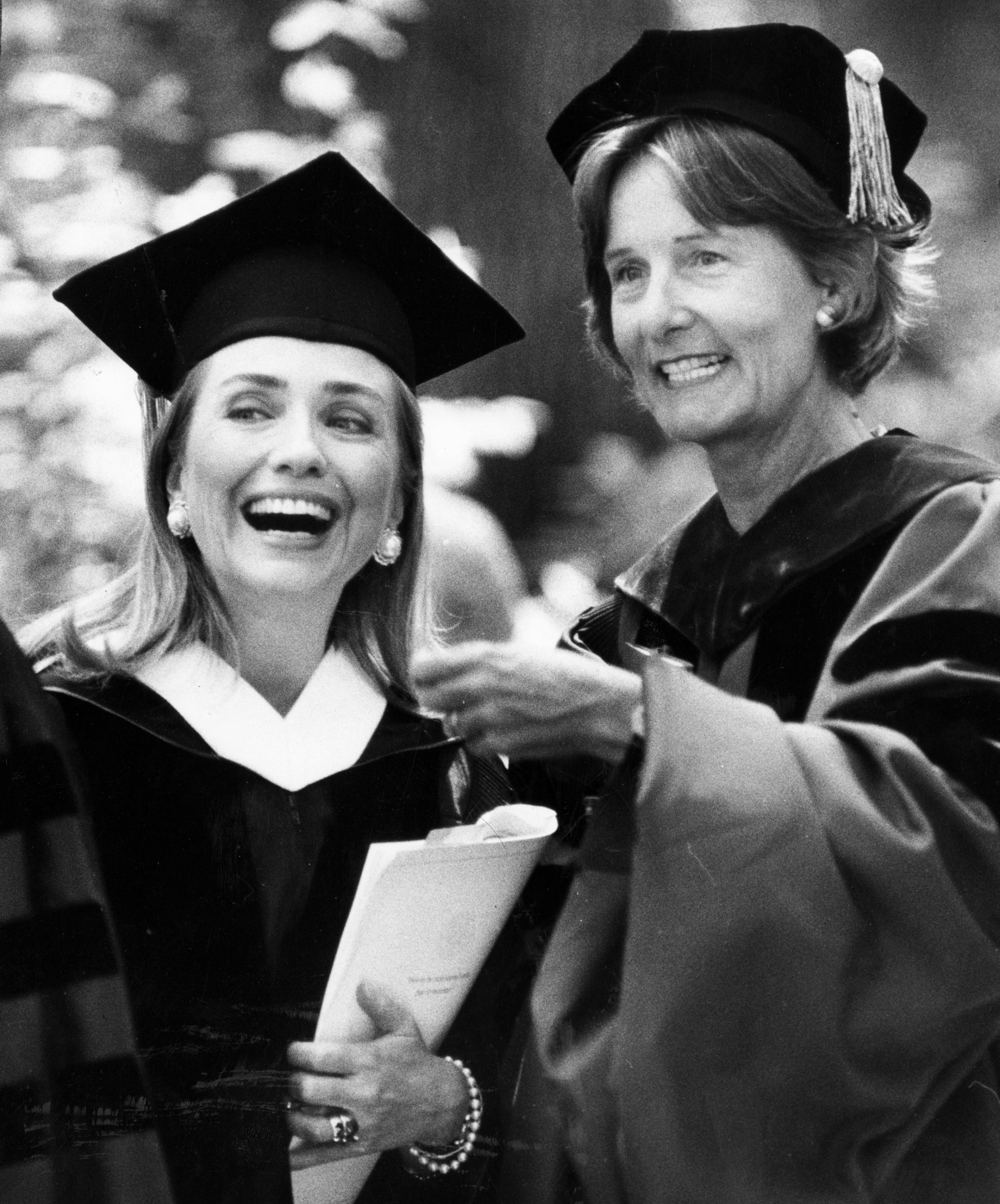

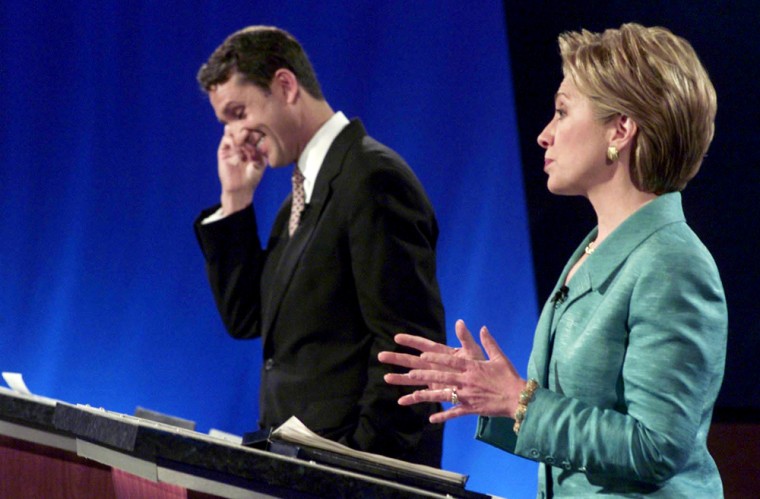

Hillary Clinton , attorney, spouse of Democratic presidential candidate Bill Clinton and member of the Wellesley College class of 1969, deliv… read more

Hillary Clinton , attorney, spouse of Democratic presidential candidate Bill Clinton and member of the Wellesley College class of 1969, delivered the commencement address for the graduating class of 1992. In her remarks, Ms. Clinton discussed the challenges facing the 1992 graduating class as well as current international affairs following the Cold War and the recent flap over family values started by Vice President Quayle ’s condemnation of the television sitcom Murphy Brown. Ms. Clinton had spoken at her commencement from Wellesley College in 1969, and referred to her education at Wellesley frequently during her remarks. close

Javascript must be enabled in order to access C-SPAN videos.

- Text type Text People Graphical Timeline

- Filter by Speaker All Speakers Hillary Rodham Clinton

- Search this text

*This text was compiled from uncorrected Closed Captioning.

People in this video

Hosting Organization

- Wellesley College Wellesley College

- Commencement Speeches

Airing Details

- May 29, 1992 | 5:22pm EDT | C-SPAN 1

- May 30, 1992 | 10:26am EDT | C-SPAN 1

- May 31, 1992 | 2:20am EDT | C-SPAN 2

- May 31, 1992 | 6:33pm EDT | C-SPAN 2

Related Video

Commencement Address

First Lady Hillary Clinton talked about the importance of the family unit and the challenges facing the next generation …

Brooklyn College Commencement Address

First Lady Hillary Clinton delivered the Brooklyn College Commencement Address.

Wellesley College Commencement

Ms. Goldberg addressed the 2002 graduating class of Wellesley College.

Toni Morrison addressed the 2004 graduating class of Wellesley College. She cautioned them against the degradation of ci…

User Created Clips from This Video

Hillary Clinton on 1969 Wellesley College Speech

- 2,266 views

Hillary Clinton SOT for Murphy Brown podcast

User Clip: Wellesley College Commencement Address

User Clip: The American Dream is

Read the Full Transcript of Hillary Clinton’s Wellesley College Commencement Speech

In it, she shares how she got through last year's election loss.

In 1969, Hillary Rodham delivered the first-ever Wellesley college student commencement speech. Now 48 years later, the former Secretary of State returned to her alma mater to give the commencement address.

Read a full transcript of her speech below:

Thank you so much for that warm welcome. I am happy to be back here at Wellesley, especially for President Johnson's first commencement and to thank her, the trustees, families and friends, faculty, staff, and guests for understanding and perpetuating the importance of this college. What it stands for, what it has meant and what it will do in the years ahead. And most importantly, it's wonderful to be here with another green class to say congratulations to the class of 2017.

Now, I have some of my dear friends here from my class. A green class of 1969. And I assume or at least you can tell me later unlike us, you actually have a class cheer. 1969 Wellesley. Yet another year with no class cheer. But it is such an honor to join with the college and all who have come to celebrate this day with you and to recognize the amazing futures that await you. You know, four years ago maybe a little more or less for some of you.

Just a minute. I've got to get a lozenge. Thank you. I told the trustees I was sitting with after hearing Paula's speech I didn't think I could get through it. So we'll blame allergy instead of emotion.

But you know, you arrived at this campus, you arrived from all over. You joined students from 49 states and 58 countries. Now, maybe you felt like you belonged right away. I doubt it. But maybe some of you did and you've never wavered. But maybe you changed your major three times and your hair style twice as many as that. Or maybe after your first month of classes you made a frantic collect call—ask your parents what that was—back to Illinois to tell your mother and father you weren't smart enough to be here.

My father said okay, come home. My mother said you have to stick it out. That's what happened to me. But whatever your path, you dream big. You probably in true Wellesley fashion planned your academic and extracurricular schedule right down to the minute. So this day that you're been waiting for and maybe dreading a little is finally here. As President Johnson said, I spoke at my commencement 48 years ago. I came back 25 years ago to speak at another commencement. I couldn't think of any place I'd rather be this year than right here.

You may have heard that things didn't exactly go the way I planned. But you know what? I'm doing okay. I've gotten to spend time with my family, especially my amazing grandchildren. I was going to give the entire commencement speech about them but was talked out of it.

Long walks in the woods. Organizing my closets, right? I won't lie. Chardonnay helped a little too. Here's what helped most of all. Remembering who I am, where I come from, and what I believe. And that is what Wellesley means to me. This college gave me so much. It launched me on a life of service and provided friends that I still treasure. So wherever your life takes you, I hope that Wellesley serves as that kind of touchstone for you.

Now, if any of you are nervous about what you'll be walking into when you leave the campus, I know that feeling. I do remember my commencement. I've been asked by my classmates to speak. I stayed up all night with my friends, the third floor of Davis. Writing and editing the speech. By the time we gathered in the academic quad, I was exhausted. My hair was a wreck. The mortar board made it even worse. But I was pretty oblivious to all of that, because what my friend his asked me to do was to talk about our worries and about our ability and responsibility to do something about them. We didn't trust government, authority figures, or really anyone over 30.

In large part, thanks to years of heavy casualties and statements about Vietnam and deep differences over civil rights and poverty here at home. We were asking urgent questions about whether women, people of color, religious minorities, immigrants would ever be treated with dignity and respect. And by the way, we were furious about the past presidential election of a man whose presidency would eventually end in disgrace with his impeachment for obstruction of justice. After firing the person running the investigation into him at the department of justice.

But here's what I want you to know. We got through that tumultuous time and once again we began to thrive as our society changed laws and opened the circle of opportunity and rights wider and wider for more Americans. We revved up the engines of imagination. We turned back a tide of intolerance and embraced inclusion. The we who did those things were more than those in power who wanted to change course. It was millions of ordinary citizens, especially young people who voted, marched and organized. Now, of course today has some important differences.

The advance of technology, the impact of the Internet, our fragmented media landscape, make it easier than ever to splinter ourselves into echo chambers. We can shut out contrary voices, avoid ever questioning our basic assumptions. Extreme views are given powerful microphones. Leaders willing to exploit fear and skepticism have tools at their disposal that were unimaginable when I graduated.

And here’s what that means to you, the class of 2017. You are graduating at a time when there is a full-fledged assault on truth and reason. Just log on to social media for ten seconds. It will hit you right in the face. People denying science, concocting elaborate, hurtful conspiracies theories about child abuse rings operating out of pizza parlors. Drumming up rampant fear about undocumented immigrants, Muslims, minorities, the poor. Turning neighbor against neighbor and sowing division at a time when we desperately need unity. Some are even denying things we see with our own eyes. Like the size of crowds.

And then defending themselves by talking about “alternative facts.” But this is serious business. Look at the budget that was just proposed in Washington. It is an attack of unimaginable cruelty on the most vulnerable among us, the youngest, the oldest, the poorest, and hardworking people who need a little help to gain or hang on to a decent middle-class life. It grossly underfunds public education, mental health, and efforts even to combat the opioid epidemic. And in reversing our commitment to fight climate change, it puts the future of our nation and our world at risk.

And to top it off, it is shrouded in a trillion-dollar mathematical lie. Let's call it what it is. It's a con. They don't even try to hide it. Why does all this matter? It matters because if our leaders lie about the problems we face, we'll never solve them. It matters because it undermines confidence in government as a whole which in turn breeds more cynicism and anger. But it also matters because our country, like this college, was founded on the principles of the enlightenment. In particular, the belief that people, you and I, possess the capacity for reason and critical thinking. And that free and open debate is the life blood of a democracy.

Not only Wellesley, but the entire American university system, the envy of the world, was founded on those fundamental ideals. We should not abandon them. We should revere them. We should aspire to them every single day in everything we do.

And there's something else. As the history majors among you here today know all too well, when people in power invent their own facts and attack those who question them, it can mark the beginning of the end of a free society.

That is not hyperbole. It is what authoritarian regimes throughout history have done. They attempt to control reality. Not just our laws and our rights and our budgets, but our thoughts and beliefs. Right now some of you might wonder well, why am I telling you all this? You don't own a cable news network. You don't control the Facebook algorithm. You aren't a member of congress. Yet.

Because I believe with all my heart that the future of America, indeed the future of the world, depends on brave, thoughtful people like you insisting on truth and integrity right now every day. You didn't create these circumstances but you have the power to change them.

Vaclav Havel, the playwright, the first president of the Czech Republic, wrote an essay called "The Power of the Powerless." And in it he said, the moment someone breaks through in one place, when one person cries out, the emperor is naked. When a single person breaks the rules of the game thus exposing it as a game, everything suddenly appears in another light.

What he's telling us is if you feel powerless, don't. Don't let anyone tell you your voice doesn't matter. In the years to come, there will be trolls galore online and in person. Eager to tell you that you don't have anything worthwhile to say or anything meaningful to contribute. They may even call you a nasty woman. Some may take a slightly more sophisticated approach and say your elite education means you are out of teach with real people. In other words, sit down and shut up. Now, in my experience, that's the last thing you should ever tell a Wellesley graduate.

And here's the good news. What you've learned these four years is precisely what you need to face the challenges of this moment. First, you learned critical thinking. I can still remember the professors who challenged me to make decisions with good information, rigorous reasoning, real deliberation. I know we didn't have much of that in this past election, but we have to get back to it.

After all, in the words of my predecessor in the Senate, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, everyone is entitled to his own opinion but not his own facts. And your education gives you more than knowledge. It gives you the power to keep learning and apply what you know to improve your life and the lives of others. Because you are beginning your careers with one of the best educations in the world, I think you do have a special responsibility to give others the chance to learn and think for themselves and to learn from them so that we can have the kind of open fact-based debate necessary for our democracy to survive and flourish. And along the way, you may be convinced to change your mind from time to time. You know what? That's okay. Take it from me, the former president of the Wellesley College Young Republicans.

Second, you learn the value of an open mind and an open society. At their best, our colleges and universities are free marketplaces of ideas. Embracing a diversity of perspectives and backgrounds. That's our country at our best, too. An open, inclusive, diverse society is the opposite of an anecdote to a closed society where there is only one right way to think, believe, and act.

Here at Wellesley you've worked hard to turn this ideal into a reality. You've spoken out against racism and sexism and discrimination of all kinds and you've shared your own stories and at times that's taken courage. But the only way our society will ever become a place where everyone truly belongs is if all of us speak openly and honestly about who we are, what we're going through. So keep doing that. And let me add that your learning, listening and serving should include people who don't agree with you politically. A lot of our fellow Americans have lost faith in the existing economic, social, political, and cultural conditions of our country. Many feel left behind, left out, looked down on.

Their anger and alienation has proved a fertile ground for false promises and information. It must be addressed or they will continue to sign up to be foot soldiers in the ongoing conflict between us and them. The opportunity is here. Millions of people will be hurt by the policies, including this budget that is being considered. And many of those same people don't want dreamers deported or health care taken away. Many don't want to retreat on civil rights, women's rights and LGBT rights. So if your outreach is rebuffed, keep trying. Do the right thing anyway. We're going to share this future. Better do so with open hearts and outstretched hands than closed minds and clenched fists.

Here at Wellesley you learned the power of service. Because while free and fierce conversations in classrooms, dorm rooms, dining halls are vital. They only get us so far. You have to turn those ideas and those values into action. This college has always understood that. The motto which you've heard twice already not to be ministered unto but to minister is as true today as it ever was. You think about it, it's kind of an old-fashioned rendering of President Kennedy's great statement. Ask not what your country can do for you. Ask what you can do for your country.

Not long ago I got a note from a group of Wellesley alums and students who had supported me in the campaign. They worked their hearts out and like a lot of people they're wondering what do we do now? Well, I think there's only one answer. Keep going. Don't be afraid of your ambition, of your dreams, or even your anger. Those are powerful forces. But harness them to make a difference in the world. Stand up for truth and reason. Do it in private, in conversations with your family, your friends, your workplace, your neighborhoods, and do it in public. In media posts, on social media, or grab a sign and head to a protest. Make defending truth and a free society a core value of your life every single day.

So wherever you wind up next, the minute you get there, register to vote. And while you're at it, encourage others to do so. And then vote in every election. Not just the presidential ones. Bring others to vote. Fight every effort to restrict the right of law abiding citizens to be able to vote as well.

Get involved in a cause that matters to you. Pick one. Start somewhere. You don't have to do everything. But don't sit on the sidelines. And you know what? Get to know your elected officials. If you disagree with them, ask questions. Challenge them. Better yet, run for office yourself someday.

Now, that's not for everybody. I know. And it's certainly not for the faint of heart, but it's worth it. As they say in one of my favorite movies, A League of Their Own, it's supposed to be hard. The hard is what makes it great.

As Paula said, the day after the election, I did want to speak, particularly to women and girls everywhere, especially young women. Because you are valuable. And powerful. And deserving of every chance and opportunity in the world. Not just your future, but our future depends on you believing that. We need your smarts, of course. But we also need your compassion. Your curiosity. Your stubbornness. And remember, you are even more powerful because you have so many people supporting you, cheering you on, standing with you through good times and bad.

You know, our culture often celebrates people who appear to go it alone. But the truth is that's not how life works. Anything worth doing takes a village. And you build that village by investing love and time into your relationships. And in those moments, for whatever reason, when it might feel bleak, think back to this place where women have the freedom to take risks, make mistakes, even fail in front of each other. Channel the strength of your Wellesley classmates and experiences. I guarantee you it will help you stand up a little straighter, feel a little braver, knowing that the things you joked about and even took for granted can be your secret weapons for your future. One of the things that gave me the most hope and joy after the election, when I really needed it, was meeting so many young people who told me that my defeat had not defeated them.

And I'm going to devote a lot of my future to helping you make your mark in the world. I created a new organization called onward together to help recruit and train future leaders, organize for real and lasting change. The work never ends. When I graduated and made that speech, I did say, and some of you might have pictures from that day with this on it, the challenge now is to practice politics as the art of making what appears to be impossible possible. That was true then. It's truer today.

I never could have imagined where I would have been 48 years later. Certainly never that I would have run for the presidency of the United States or seen progress for women in all walks of life over the course of my lifetime. And yes, put millions of more cracks in that highest and hardest glass ceiling. Because just in those years, doors that once seemed sealed to women are now open. They're ready for you to walk through or charge through. To advance the struggle for equality, justice, and freedom. So whatever your dreams today, dream even bigger. Wherever you have set your sights, raise them even higher. And above all, keep going. Don't do it because I asked you to. Do it for yourselves. Do it for truth and reason. Do it because the history of Wellesley and this country tells us it's often during the darkest times when you can do the most good.

Double down on your passions. Be bold. Try. Fail. Try again and lean on each other. Hold on to your values. Never give up on those dreams. I'm have been optimistic about the future. Because I think after we've tried a lot of other things, we get back to the business of America. I believe in you with all my heart. I want you to believe in yourselves. So go forth. Be great. But first graduate. Congratulations!

As the digital director for Town & Country, Caroline Hallemann covers culture, entertainment, and a range of other subjects

@media(min-width: 40.625rem){.css-1jdielu:before{margin:0.625rem 0.625rem 0;width:3.5rem;-webkit-filter:invert(17%) sepia(72%) saturate(710%) hue-rotate(181deg) brightness(97%) contrast(97%);filter:invert(17%) sepia(72%) saturate(710%) hue-rotate(181deg) brightness(97%) contrast(97%);height:1.5rem;content:'';display:inline-block;-webkit-transform:scale(-1, 1);-moz-transform:scale(-1, 1);-ms-transform:scale(-1, 1);transform:scale(-1, 1);background-repeat:no-repeat;}.loaded .css-1jdielu:before{background-image:url(/_assets/design-tokens/townandcountrymag/static/images/diamond-header-design-element.80fb60e.svg);}}@media(min-width: 64rem){.css-1jdielu:before{margin:0 0.625rem 0.25rem;}} Politics in 2024 @media(min-width: 40.625rem){.css-128xfoy:before{margin:0.625rem 0.625rem 0;width:3.5rem;-webkit-filter:invert(17%) sepia(72%) saturate(710%) hue-rotate(181deg) brightness(97%) contrast(97%);filter:invert(17%) sepia(72%) saturate(710%) hue-rotate(181deg) brightness(97%) contrast(97%);height:1.5rem;content:'';display:inline-block;background-repeat:no-repeat;}.loaded .css-128xfoy:before{background-image:url(/_assets/design-tokens/townandcountrymag/static/images/diamond-header-design-element.80fb60e.svg);}}@media(min-width: 64rem){.css-128xfoy:before{margin:0 0.625rem 0.25rem;}}

Who Is President Biden's Daughter Ashley Biden?

Dr. Jill Biden's First Lady Fashion

Why Tonight's Presidential Debate Is Unprecedented

Meet Joe Biden's Granddaughter Maisy Biden

Meet Finnegan Biden

Meet Joe Biden's Granddaughter Naomi Biden

Jimmy Carter Is Nearing the End of His Life

Can Donald Trump Vote in the 2024 Election?

Donald Trump Was Found Guilty. What’s Next?

Jimmy Carter's Grandson Offers Health Update

JFK's Grandson Mocks RFK Jr. on Instagram

Wellesley College Commencement Address - May 29, 1992

President Keohane, trustees, faculty, students, parents, friends, and, most of all, honored graduates of the Class of 1992.

This is my second chance to speak from this podium. The first was 23 years ago, when I was a graduating senior. My classmates selected me to address them as the first Wellesley student ever to speak at a commencement.

I can't claim that 1969 speech as my own; it reflected the hopes, values, and aspirations of the women in my graduating class. It was full of the uncompromising language you only write when you are 21. But it's uncanny the degree to which those same hopes, values, and aspirations have shaped my adulthood.

We passionately rejected the notion of limitations on our abilities to make the world a better place. We saw a gap between our expectations and realities, and we were inspired, in large part by our Wellesley education, to bridge that gap. On behalf of the class of 1969, I said, "The challenge now is to practice politics as the art of making what appears to be impossible, possible." That is still the challenge of politics, especially in today's far more cynical climate.

The aspiration I referred to then was "the struggle for an integrated life... in an atmosphere of... trust and respect." What I meant by that was a life that combines personal fulfillment in love and work with fulfilling responsibility to the larger community. A life that balances family, work, and service throughout life. It's not a static concept, but a constant journey.

When the ceremonies and hoopla of my graduation were over, I commenced my adult life by heading straight for Lake Waban. Now, as you know, swimming in the lake, other than at the beach, is not allowed. But it was one of my favorite rules to break. I stripped down to my swimsuit, took off my Coke-bottle glasses, laid them carefully on top of my clothes and waded in off Tupelo Point.

While I was happily paddling around, feeling relieved I had survived the day, a security guard came by on his rounds, picked up my clothes from the shore and carried them off. He also took my glasses. Blind as a bat, I had to feel my way back to my room at Davis.

I'm just glad that picture hasn't also come back to haunt me. You can imagine the captions: "Girl offers vision to classmates and then loses her own." Or, the tabloids might have run something like: "Girl swimming, blinded by aliens after seeing Elvis."

While medical technology has allowed me to replace those glasses with contact lenses, I hope my vision today is clearer for another reason: the clarifying perspective of experience. The opportunity to share that experience with you today is a privilege and a kind of homecoming.

Wellesley nurtured, challenged, and guided me; it instilled in me, not just knowledge, but a reserve of sustaining values. I also made friends who are still among my closest friends today.

When I arrived as a freshman in 1965 from my "Ozzie and Harriet" suburb of Chicago, both the College and the country were going through a period of rapid, sometimes tumultuous changes. My classmates and I felt challenged and, in turn, challenged the College from the moment we arrived. Nothing was taken for granted. Our Vil Juniors despaired of us green-beanied '69ers because we couldn't even agree on an appropriate, politically correct cheer. To this day when we attend reunions, you can hear us cry: "1-9-6-9 Wellesley Rah, one more year, still no cheer."

There often seemed little to cheer about. We grew up in a decade dominated by dreams and disillusionments. Dreams of the civil rights movement, of the Peace Corps, of the space program. Disillusionments starting with President Kennedy's assassination, accelerated by the divisive war in Vietnam, and the deadly mixture of poverty, racism, and despair that burst into flames in the hearts of some cities and which is still burning today. A decade when speeches like "I Have a Dream" were followed by songs like "The Day the Music Died."

I was here on campus when Martin Luther King was murdered. My friends and I put on black armbands and went into Boston to march in anger and pain—feeling as many of you did after the acquittals in the Rodney King case.

Much has changed—and much of it for the better—but much has also stayed the same, or at least not changed as fast or as irrevocably as we had hoped.

Each new generation takes us into new territory. But while change is certain, progress is not. Change is a law of nature; progress is the challenge for both a life and society. Describing an integrated life is easier than achieving one.

Yet, what better place to speak on integrating the strands of women's lives than Wellesley, a college that not only vindicates the proposition that there is still an essential place for an all-women's college, but which defines its mission as seeking "to educate women who will make a difference in the world."

And what better time to speak than in the spring of 1992, when women's concerns are so much in the news, as real women—and even fictional television characters—seek to strike the balances in their lives that are right for them.

I've traveled all over America, talking and listening to women who are: struggling to raise their children and somehow make ends meet; battling against the persistent discrimination that still limits their opportunities for pay and promotion; bumping up against the glass ceiling; watching their insurance premiums increase; coping with inadequate or nonexistent child support payments; existing on shrinking welfare payments with no available jobs in sight; anguishing over the prospect that abortions will be criminalized again.

We also talk about our shared values as women and mothers, about our common desire to educate our children, to be sure they receive the health care they need, to protect them from the escalating violence in our streets. We worry about our children—something mothers do particularly well.

Women who pack lunch for their kids, or take the early bus to work, or stay out late at the PTA, or spend every spare minute taking care of aging parents don't need lectures from Washington about values. We don't need to hear about an idealized world that never was as righteous or carefree as some would like to think. We need understanding and a helping hand to solve our own problems. We're doing the best we can to find the right balance in our lives.

For me, the elements of that balance are family, work, and service.

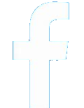

First, your personal relationships. When all is said and done, it is the people in your life, the friendships you form and the commitments you maintain, that give shape to your life. Your friends and your neighbors, the people at work or church, all those who touch your daily lives. And if you choose, a marriage filled with love and respect. When I stood here before, I could never have predicted—much less believed—that I would fall in love with Bill Clinton and follow my heart to Arkansas. But I'm very glad I had the courage to make that choice.

Second, your work. For some of you, that may overlap with your contribution to the community. For some of you, the future might not include work outside the home (and I don't mean involuntary unemployment); but most of you will at some point in your life work for pay, maybe in jobs that used to be off-limits for women. You may choose to be a corporate executive or a rocket scientist, you may choose to run for public office, you may choose to stay home and raise your children—you can now make any or all of these choices for the work of your life.

Third, your service. As students, we debated passionately what responsibility each individual has for the larger society and just what the College's Latin motto—"Not to be ministered unto, but to minister"—actually meant. The most eloquent explanation I have found of what I believe now and what I argued then is from Vaclav Havel, the playwright and first freely-elected president of Czechoslovakia. In a letter from prison to his wife, Olga, he wrote:

Everything meaningful in life is distinguished by a certain transcendence of individual human existence—beyond the limits of mere "self-care"—toward other people, toward society, toward the world.... Only by looking outward, by caring for things that, in terms of pure survival, you needn't bother with at all... and by throwing yourself over and over again into the tumult of the world, with the intention of making your voice count—only thus will you really become a person.

I first recognized what I cared most about while I was in law school where I worked with children at the Yale New Haven Hospital and Child Study Center and represented children through legal services. And where during my first summer I worked for the Children's Defense Fund. My experiences gave voice to deep feelings about what children deserved from their families and government. I discovered that I wanted my voice to count for children.

Some of you may have already had such a life-shaping experience; for many, it lies ahead. Recognize it and nurture it when it occurs.

Because my concern is making children count, I hope you will indulge me as I tell you why. The American Dream is an intergenerational compact. Or, as someone once said, one generation is supposed to leave the key under the mat for the next. We repay our parents for their love in the love we give our children—and we repay our society for the opportunities we are given by expanding the opportunities granted others. That's the way it's supposed to work. You know too well that it is not. Too many of our children are being impoverished financially, socially, and spiritually. The shrinking of their futures ultimately diminishes us all. Whether you end up having children of your own or not, I hope each of you will recognize the need for a sensible national family policy that reverses the neglect of our children.

If you have children, you will owe the highest duty to them and will confront your biggest challenges as parents. If, like me at your age, you now know little (and maybe care less) about the mysteries of good parenting, I can promise you there is nothing like on-the-job-training.

I remember one very long night when my daughter, Chelsea, was about four weeks old and crying inconsolably. Nothing from the courses in my political science major seemed to help. Finally, I said, "Chelsea, you've never been a baby before and I've never been a mother before, we're going to have to help each other get through this together." So far, we have. For Bill and me, she has been the great joy of our life. Watching her grow and flourish has given greater urgency to the task of helping all children.

There are many ways of helping children. You can do it through your own personal lives by being dedicated, loving parents. You can do it in medicine or music, social work or education, business or government service, by making policy or making cookies.

It is a false choice to tell women—or men for that matter—that we must choose between caring for ourselves and our own families or caring for the larger family of humanity. In their recent Pastoral Letter, "Putting Children and Families First," the National Conference of Catholic Bishops captured this essential interplay of private and public roles: "No government can love a child and no policy can substitute for a family's care," the Bishops wrote, but "government can either support or undermine families.... There has been an unfortunate, unnecessary, and unreal polarization in discussions of how best to help families.... The undeniable fact is that our children's future is shaped both by the values of their parents and the policies of our nation."

As my husband says, "Family values alone won't feed a hungry child. And material security cannot provide a moral compass. We need both."

Forty-five years ago, the biggest threat to our country came from the other side of the Iron Curtain; from the nuclear weapons that could wipe out the entire planet. While you were here at Wellesley, that threat ended.

Today, our greatest national threat comes not from some external Evil Empire, but from our own internal Indifferent Empire that tolerates splintered families, unparented children, embattled schools, and pervasive poverty, racism, and violence.

Not for one more year can our country think of children as some asterisk on our national agenda. How we treat our children should be front and center of our national agenda, or it won't matter what else is on that agenda.

My plea is that you not only nurture the values that will determine the choices you make in your personal lives, but also insist on policies with those values to nurture our nation's children.

"But, really, Hillary," some of you may be saying to yourselves, "I've got to pay off my student loans. I can't even find a good job, let alone someone to love. How am I going to worry about the world? Our generation has fewer dreams, fewer illusions than yours."

And I hear you. As women today, you face tough choices. You know the rules are basically as follows:

If you don't get married, you're abnormal.

If you get married but don't have children, you're a selfish yuppie.

If you get married and have children, but work outside the home, you're a bad mother.

If you get married and have children, but stay home, you've wasted your education.

And if you don't get married, but have children and work outside the home as a fictional newscaster, then you're in trouble with Dan Quayle.

So you see, if you listen to all the people who make these rules, you might just conclude that the safest course of action is just to take your diploma and crawl under your bed. But let me propose an alternative.

Hold onto your dreams. Take up the challenge of forging an identity that transcends yourself. Transcend yourself and you will find yourself. Care about something you needn't bother with at all. Throw yourself into the world and make your voice count.

Whether you make your voice count for children or for another cause, enjoy your life's journey. There is no dress rehearsal for life, and you will have to ad lib your way through each scene. The only way to prepare is to do what you have done: Get the best possible education; continue to learn from literature, scripture and history, to understand the human experience as best you can so that you have guideposts charting the terrain toward whatever decisions are right for you.

I want you to remember this day and remember how much more you have in common with each other than with the people who are trying to divide you. And I want you to stand together then as you stand together now; beautiful, brave, invincible.

Congratulations. Look forward to the challenges ahead.

Speech from http://www.wellesley.edu/events/commencement/archives/1992commencement/commencementaddress#F08oSJgFqljyuJHw.99 .

Neither the Catt Center nor Iowa State University is affiliated with any individual in the Archives or any political party. Inclusion in the Archives is not an endorsement by the center or the university.

Read Hillary Clinton’s 1969 Wellesley Commencement Speech

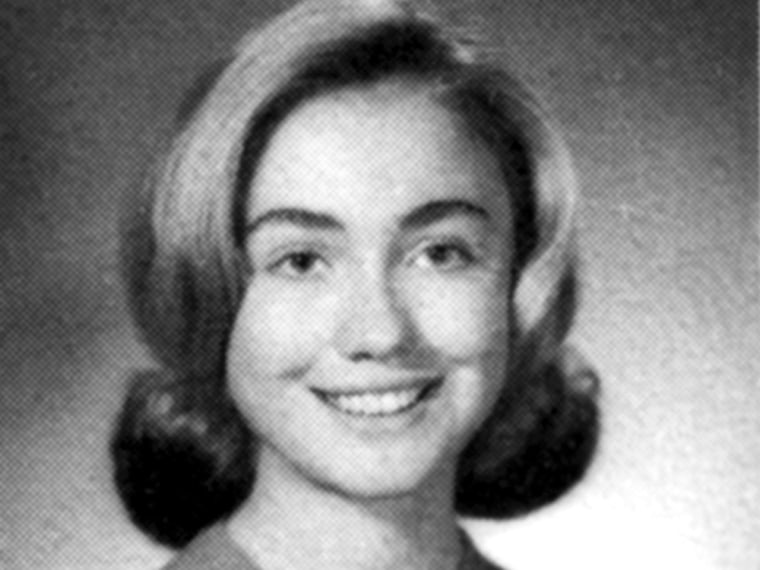

P resumptive Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton’s alma mater, Wellesley College, released audio excerpts on Monday from the 1969 commencement speech delivered by the 21-year-old then known as Hillary Rodham.

Ruth Adams, then-president of Wellesley, introduced Clinton, calling her “cheerful, good humored, good company, and a good friend to all of us.”

“Fear is always with us but we just don’t have time for it. Not now,” Clinton said during the 1969 speech, a sentiment she echoed last week , when she compared the choice between Republican Donald Trump and herself to a choice between a “fearful America” and a “strong, confident America,” respectively.

Read the complete remarks from Clinton’s graduation ceremony on May 31, 1969:

ADAMS: In addition to inviting Senator Brooke to speak to them this morning, the Class of ’69 has expressed a desire [for a student] to speak to them and for them at this morning’s commencement. There was no debate so far as I could ascertain as to who their spokesman was to be: Miss Hillary Rodham. Member of this graduating class, she is a major in political science and a candidate for the degree with honors. In four years she has combined academic ability with active service to the College, her junior year having served as a Vil Junior, and then as a member of Senate and during the past year as president of College Government and presiding officer of College Senate. She is also cheerful, good humored, good company, and a good friend to all of us and it is a great pleasure to present to this audience Miss Hillary Rodham. CLINTON: I am very glad that Miss Adams made it clear that what I am speaking for today is all of us—the 400 of us—and I find myself in a familiar position, that of reacting, something that our generation has been doing for quite a while now. We’re not in the positions yet of leadership and power, but we do have that indispensable element of criticizing and constructive protest and I find myself reacting just briefly to some of the things that Senator Brooke said. This has to be quick because I do have a little speech to give. Part of the problem with just empathy with professed goals is that empathy doesn’t do us anything. We’ve had lots of empathy; we’ve had lots of sympathy, but we feel that for too long our leaders have viewed politics as the art of the possible. And the challenge now is to practice politics as the art of making what appears to be impossible possible. What does it mean to hear that 13.3 percent of the people in this country are below the poverty line? That’s a percentage. We’re not interested in social reconstruction; it’s human reconstruction. How can we talk about percentages and trends? The complexities are not lost in our analyses, but perhaps they’re just put into what we consider a more human and eventually a more progressive perspective. The question about possible and impossible was one that we brought with us to Wellesley four years ago. We arrived not yet knowing what was not possible. Consequently, we expected a lot. Our attitudes are easily understood having grown up, having come to consciousness in the first five years of this decade—years dominated by men with dreams, men in the civil rights movement, the Peace Corps, the space program—so we arrived at Wellesley and we found, as all of us have found, that there was a gap between expectation and realities. But it wasn’t a discouraging gap and it didn’t turn us into cynical, bitter old women at the age of 18. It just inspired us to do something about that gap. What we did is often difficult for some people to understand. They ask us quite often: “Why, if you’re dissatisfied, do you stay in a place?” Well, if you didn’t care a lot about it you wouldn’t stay. It’s almost as though my mother used to say, “You know I’ll always love you but there are times when I certainly won’t like you.” Our love for this place, this particular place, Wellesley College, coupled with our freedom from the burden of an inauthentic reality allowed us to question basic assumptions underlying our education. Before the days of the media orchestrated demonstrations, we had our own gathering over in Founder’s parking lot. We protested against the rigid academic distribution requirement. We worked for a pass-fail system. We worked for a say in some of the process of academic decision making. And luckily we were at a place where, when we questioned the meaning of a liberal arts education there were people with enough imagination to respond to that questioning. So we have made progress. We have achieved some of the things that we initially saw as lacking in that gap between expectation and reality. Our concerns were not, of course, solely academic as all of us know. We worried about inside Wellesley questions of admissions, the kind of people that were coming to Wellesley, the kind of people that should be coming to Wellesley, the process for getting them here. We questioned about what responsibility we should have both for our lives as individuals and for our lives as members of a collective group. Coupled with our concerns for the Wellesley inside here in the community were our concerns for what happened beyond Hathaway House. We wanted to know what relationship Wellesley was going to have to the outer world. We were lucky in that Miss Adams, one of the first things she did was set up a cross-registration with MIT because everyone knows that education just can’t have any parochial bounds anymore. One of the other things that we did was the Upward Bound program. There are so many other things that we could talk about; so many attempts to kind of – at least the way we saw it – pull ourselves into the world outside. And I think we’ve succeeded. There will be an Upward Bound program, just for one example, on the campus this summer. Many of the issues that I’ve mentioned—those of sharing power and responsibility, those of assuming power and responsibility—have been general concerns on campuses throughout the world. But underlying those concerns there is a theme, a theme which is so trite and so old because the words are so familiar. It talks about integrity and trust and respect. Words have a funny way of trapping our minds on the way to our tongues but there are necessary means even in this multimedia age for attempting to come to grasps with some of the inarticulate maybe even inarticulable things that we’re feeling. We are, all of us, exploring a world that none of us even understands and attempting to create within that uncertainty. But there are some things we feel, feelings that our prevailing, acquisitive, and competitive corporate life, including tragically the universities, is not the way of life for us. We’re searching for more immediate, ecstatic, and penetrating modes of living. And so our questions, our questions about our institutions, about our colleges, about our churches, about our government continue. The questions about those institutions are familiar to all of us. We have seen them heralded across the newspapers. Senator Brooke has suggested some of them this morning. But along with using these words—integrity, trust, and respect—in regard to institutions and leaders, we’re perhaps harshest with them in regard to ourselves. Every protest, every dissent, whether it’s an individual academic paper or Founder’s parking lot demonstration, is unabashedly an attempt to forge an identity in this particular age. That attempt at forging for many of us over the past four years has meant coming to terms with our humanness. Within the context of a society that we perceive—now we can talk about reality, and I would like to talk about reality sometime, authentic reality, inauthentic reality, and what we have to accept of what we see—but our perception of it is that it hovers often between the possibility of disaster and the potentiality for imaginatively responding to men’s needs. There’s a very strange conservative strain that goes through a lot of New Left, collegiate protests that I find very intriguing because it harkens back to a lot of the old virtues, to the fulfillment of original ideas. And it’s also a very unique American experience. It’s such a great adventure. If the experiment in human living doesn’t work in this country, in this age, it’s not going to work anywhere. But we also know that to be educated, the goal of it must be human liberation. A liberation enabling each of us to fulfill our capacity so as to be free to create within and around ourselves. To be educated to freedom must be evidenced in action, and here again is where we ask ourselves, as we have asked our parents and our teachers, questions about integrity, trust, and respect. Those three words mean different things to all of us. Some of the things they can mean, for instance: Integrity, the courage to be whole, to try to mold an entire person in this particular context, living in relation to one another in the full poetry of existence. If the only tool we have ultimately to use is our lives, so we use it in the way we can by choosing a way to live that will demonstrate the way we feel and the way we know. Integrity—a man like Paul Santmire. Trust. This is one word that when I asked the class at our rehearsal what it was they wanted me to say for them, everyone came up to me and said “Talk about trust, talk about the lack of trust both for us and the way we feel about others. Talk about the trust bust.” What can you say about it? What can you say about a feeling that permeates a generation and that perhaps is not even understood by those who are distrusted? All we can do is keep trying again and again and again. There’s that wonderful line in “East Coker” by Eliot about there’s only the trying, again and again and again; to win again what we’ve lost before. And then respect. There’s that mutuality of respect between people where you don’t see people as percentage points. Where you don’t manipulate people. Where you’re not interested in social engineering for people. The struggle for an integrated life existing in an atmosphere of communal trust and respect is one with desperately important political and social consequences. And the word consequences of course catapults us into the future. One of the most tragic things that happened yesterday, a beautiful day, was that I was talking to a woman who said that she wouldn’t want to be me for anything in the world. She wouldn’t want to live today and look ahead to what it is she sees because she’s afraid. Fear is always with us but we just don’t have time for it. Not now. There are two people that I would like to thank before concluding. That’s Ellie Acheson, who is the spearhead for this, and also Nancy Scheibner who wrote this poem which is the last thing that I would like to read: My entrance into the world of so-called “social problems” Must be with quiet laughter, or not at all. The hollow men of anger and bitterness The bountiful ladies of righteous degradation All must be left to a bygone age. And the purpose of history is to provide a receptacle For all those myths and oddments Which oddly we have acquired And from which we would become unburdened To create a newer world To translate the future into the past. We have no need of false revolutions In a world where categories tend to tyrannize our minds And hang our wills up on narrow pegs. It is well at every given moment to seek the limits in our lives. And once those limits are understood To understand that limitations no longer exist. Earth could be fair. And you and I must be free Not to save the world in a glorious crusade Not to kill ourselves with a nameless gnawing pain But to practice with all the skill of our being The art of making possible. Thanks.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Melinda French Gates Is Going It Alone

- What to Do if You Can’t Afford Your Medications

- How to Buy Groceries Without Breaking the Bank

- Sienna Miller Is the Reason to Watch Horizon

- Why So Many Bitcoin Mining Companies Are Pivoting to AI

- The 15 Best Movies to Watch on a Plane

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Katie Reilly at [email protected]

Hillary Clinton's 1992 Wellesley Commencement Speech Tackles Issues Relevant Decades Later

Over two decades ago, Hillary Clinton lay out the "rules" for women struggling to balance family and work, many of which still resonate today.

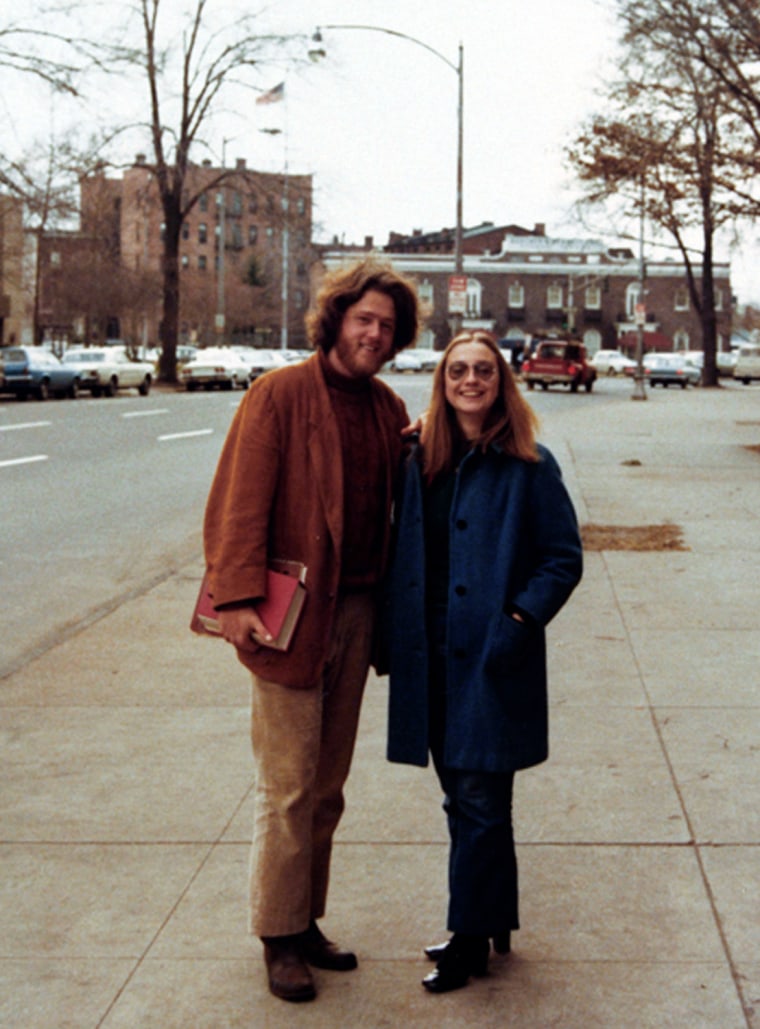

In the midst of her husband's presidential campaign in 1992, Clinton delivered the commencement address to Wellesley College's graduating class.

The New York Times reported at the time that some students were upset by the choice to have a candidate's wife speak. According to one student, Clinton was reportedly chosen last minute after dozens of other speakers were difficult to schedule.

Clinton addressed topics ranging from the Cold War to losing her clothes swimming, and then addressed the challenges of advocating for policies that "nurture our nation's children" amid the many responsibilities facing women at the time.

She stated:

As women today, you do face tough choices. You know the rules are basically as follows: If you don't get married, you're abnormal. If you get married, but don't have children, you're a selfish yuppie. If you get married and have children, but then go outside the home to work, you're a bad mother. If you get married and have children, but stay home, you've wasted your education. And if you don't get married, but have children and work outside the home as a fictional newscaster, you get in trouble with the vice president .

It has been two decades, but the issues remain fresh, as demonstrated by Anne-Marie Slaughter's controversial "Why Women Still Can’t Have It All" Atlantic article last year.

Clinton's advice to women at the time? "Hold on to your dreams, whatever they are."

Click here to watch the full speech in the C-Span video library.

Popular in the Community

From our partner, more in politics.

Listen: the 47-year-old Hillary Clinton college graduation speech that explains Hillary Clinton

by Alex Abad-Santos

Whether Hillary Clinton wins the election tonight or not, the historic nature of her candidacy means that young Americans, and particularly young girls, will grow up knowing that gender isn't a roadblock to attaining the highest political office in the United States. That idea is one of the core tenets of Clinton's campaign. It's also long been one of Clinton's own core beliefs.

You can see it in her college commencement speech .

In 1969, Hillary Rodham's classmates chose her to speak at commencement, the first time in Wellesley history that a student speaker (in addition to a guest and the college president) gave an address to the graduating class. (Wellesley had made audio recordings of parts of that speech available .)

Her speech followed an address by Republican Sen. Edward Brooke of Massachusetts, who argued against student protests that were taking place across college campuses . (Many of these protests were in response to the Vietnam War and military recruitment and alleged racial discrimination.) He said the protests "mistake the vigor of protest for the value of accomplishment."

According to Clinton , her fellow students and teachers at the college, she ad-libbed a graceful but pointed response to Brooke.

"We're not in the positions yet of leadership and power, but we do have that indispensable element of criticizing and constructive protest," she told her classmates. "We've had lots of empathy, we've had lots of sympathy, but we feel that for too long our leaders have viewed politics as the art of the possible. And the challenge now is to practice politics as the art of making what appears to be impossible possible."

Clinton’s ad-lib got her into a bit of trouble — the Washington Post reported that her college president sent an apology letter to Brooke . But that isn’t the most striking part of the speech, the rest of which was imbued with idealism and a thoughtfulness that’s perhaps a bit surprising coming from a college senior.

The speech’s most riveting segment comes when Clinton tries to address the apparent clash between idealism and reality. That even though she talks about a lofty design of making the impossible possible, she isn’t afraid to say that the reality of the time was scary and imperfect. She said:

Our attitudes are easily understood having grown up, having come to consciousness in the first five years of this decade — years dominated by men with dreams, men in the civil rights movement, the Peace Corps, the space program — so we arrived at Wellesley and we found, as all of us have found, that there was a gap between expectation and realities. But it wasn't a discouraging gap and it didn't turn us into cynical, bitter old women at the age of 18. It just inspired us to do something about that gap. What we did is often difficult for some people to understand. They ask us quite often: "Why, if you're dissatisfied, do you stay in a place?" Well, if you didn't care a lot about it you wouldn't stay.

That last part, the part where she talks about being unhappy with the status quo but caring so much she can’t leave, could very well describe her pursuit of the presidency. A pursuit that’s continued after being denied the chance in 2008. A pursuit that means enduring what’s been possibly the ugliest and most brutal presidential race in recent memory. A pursuit that could end tonight with how a college-age Hillary Clinton saw politics: as the art of making what seemed impossible possible.

Below is a full transcript of Clinton’s speech, courtesy of Wellesley College :

I am very glad that Miss Adams made it clear that what I am speaking for today is all of us — the 400 of us — and I find myself in a familiar position, that of reacting, something that our generation has been doing for quite a while now. We're not in the positions yet of leadership and power, but we do have that indispensable element of criticizing and constructive protest and I find myself reacting just briefly to some of the things that Senator Brooke said. This has to be quick because I do have a little speech to give.

Part of the problem with just empathy with professed goals is that empathy doesn't do us anything. We've had lots of empathy; we've had lots of sympathy, but we feel that for too long our leaders have viewed politics as the art of the possible. And the challenge now is to practice politics as the art of making what appears to be impossible possible. What does it mean to hear that 13.3 percent of the people in this country are below the poverty line? That's a percentage. We're not interested in social reconstruction; it's human reconstruction. How can we talk about percentages and trends? The complexities are not lost in our analyses, but perhaps they're just put into what we consider a more human and eventually a more progressive perspective.

The question about possible and impossible was one that we brought with us to Wellesley four years ago. We arrived not yet knowing what was not possible. Consequently, we expected a lot. Our attitudes are easily understood having grown up, having come to consciousness in the first five years of this decade — years dominated by men with dreams, men in the civil rights movement, the Peace Corps, the space program — so we arrived at Wellesley and we found, as all of us have found, that there was a gap between expectation and realities. But it wasn't a discouraging gap and it didn't turn us into cynical, bitter old women at the age of 18. It just inspired us to do something about that gap.

What we did is often difficult for some people to understand. They ask us quite often: "Why, if you're dissatisfied, do you stay in a place?" Well, if you didn't care a lot about it you wouldn't stay. It's almost as though my mother used to say, "You know I'll always love you but there are times when I certainly won't like you." Our love for this place, this particular place, Wellesley College, coupled with our freedom from the burden of an inauthentic reality allowed us to question basic assumptions underlying our education.

Before the days of the media orchestrated demonstrations, we had our own gathering over in Founder's parking lot. We protested against the rigid academic distribution requirement. We worked for a pass-fail system. We worked for a say in some of the process of academic decision making. And luckily we were at a place where, when we questioned the meaning of a liberal arts education there were people with enough imagination to respond to that questioning.

So we have made progress. We have achieved some of the things that we initially saw as lacking in that gap between expectation and reality. Our concerns were not, of course, solely academic as all of us know. We worried about inside Wellesley questions of admissions, the kind of people that were coming to Wellesley, the kind of people that should be coming to Wellesley, the process for getting them here. We questioned about what responsibility we should have both for our lives as individuals and for our lives as members of a collective group.

Coupled with our concerns for the Wellesley inside here in the community were our concerns for what happened beyond Hathaway House. We wanted to know what relationship Wellesley was going to have to the outer world. We were lucky in that Miss Adams, one of the first things she did was set up a cross-registration with MIT because everyone knows that education just can't have any parochial bounds anymore. One of the other things that we did was the Upward Bound program.

There are so many other things that we could talk about; so many attempts to kind of — at least the way we saw it — pull ourselves into the world outside. And I think we've succeeded. There will be an Upward Bound program, just for one example, on the campus this summer.

Many of the issues that I've mentioned — those of sharing power and responsibility, those of assuming power and responsibility — have been general concerns on campuses throughout the world. But underlying those concerns there is a theme, a theme which is so trite and so old because the words are so familiar. It talks about integrity and trust and respect. Words have a funny way of trapping our minds on the way to our tongues but there are necessary means even in this multimedia age for attempting to come to grasps with some of the inarticulate maybe even inarticulable things that we're feeling.

We are, all of us, exploring a world that none of us even understands and attempting to create within that uncertainty. But there are some things we feel, feelings that our prevailing, acquisitive, and competitive corporate life, including tragically the universities, is not the way of life for us. We're searching for more immediate, ecstatic, and penetrating modes of living.

And so our questions, our questions about our institutions, about our colleges, about our churches, about our government continue. The questions about those institutions are familiar to all of us. We have seen them heralded across the newspapers. Senator Brooke has suggested some of them this morning. But along with using these words — integrity, trust, and respect — in regard to institutions and leaders, we're perhaps harshest with them in regard to ourselves.

Every protest, every dissent, whether it's an individual academic paper or Founder's parking lot demonstration, is unabashedly an attempt to forge an identity in this particular age. That attempt at forging for many of us over the past four years has meant coming to terms with our humanness. Within the context of a society that we perceive — now we can talk about reality, and I would like to talk about reality sometime, authentic reality, inauthentic reality, and what we have to accept of what we see — but our perception of it is that it hovers often between the possibility of disaster and the potentiality for imaginatively responding to men's needs.

There's a very strange conservative strain that goes through a lot of New Left, collegiate protests that I find very intriguing because it harkens back to a lot of the old virtues, to the fulfillment of original ideas. And it's also a very unique American experience. It's such a great adventure. If the experiment in human living doesn't work in this country, in this age, it's not going to work anywhere.

But we also know that to be educated, the goal of it must be human liberation. A liberation enabling each of us to fulfill our capacity so as to be free to create within and around ourselves. To be educated to freedom must be evidenced in action, and here again is where we ask ourselves, as we have asked our parents and our teachers, questions about integrity, trust, and respect.

Those three words mean different things to all of us. Some of the things they can mean, for instance: Integrity, the courage to be whole, to try to mold an entire person in this particular context, living in relation to one another in the full poetry of existence. If the only tool we have ultimately to use is our lives, so we use it in the way we can by choosing a way to live that will demonstrate the way we feel and the way we know. Integrity — a man like Paul Santmire. Trust. This is one word that when I asked the class at our rehearsal what it was they wanted me to say for them, everyone came up to me and said "Talk about trust, talk about the lack of trust both for us and the way we feel about others. Talk about the trust bust."

What can you say about it? What can you say about a feeling that permeates a generation and that perhaps is not even understood by those who are distrusted? All we can do is keep trying again and again and again. There's that wonderful line in "East Coker" by Eliot about there's only the trying, again and again and again; to win again what we've lost before.

And then respect. There's that mutuality of respect between people where you don't see people as percentage points. Where you don't manipulate people. Where you're not interested in social engineering for people. The struggle for an integrated life existing in an atmosphere of communal trust and respect is one with desperately important political and social consequences.

And the word consequences of course catapults us into the future. One of the most tragic things that happened yesterday, a beautiful day, was that I was talking to a woman who said that she wouldn't want to be me for anything in the world. She wouldn't want to live today and look ahead to what it is she sees because she's afraid. Fear is always with us but we just don't have time for it. Not now.

There are two people that I would like to thank before concluding. That's Ellie Acheson, who is the spearhead for this, and also Nancy Scheibner who wrote this poem which is the last thing that I would like to read:

My entrance into the world of so-called "social problems"

Must be with quiet laughter, or not at all.

The hollow men of anger and bitterness

The bountiful ladies of righteous degradation

All must be left to a bygone age.

And the purpose of history is to provide a receptacle

For all those myths and oddments

Which oddly we have acquired

And from which we would become unburdened

To create a newer world

To translate the future into the past.

We have no need of false revolutions

In a world where categories tend to tyrannize our minds

And hang our wills up on narrow pegs.

It is well at every given moment to seek the limits in our lives.

And once those limits are understood

To understand that limitations no longer exist.

Earth could be fair. And you and I must be free

Not to save the world in a glorious crusade

Not to kill ourselves with a nameless gnawing pain

But to practice with all the skill of our being

The art of making possible.

More in this stream

Donald Trump now commands nearly complete loyalty from congressional Republicans

Donald Trump is the only US president ever with no political or military experience

Trump will be the 4th president to win the Electoral College after getting fewer votes than his opponent

Most popular, the supreme court’s disastrous trump immunity decision, explained, the supreme court also handed down a hugely important first amendment case today, hawk tuah girl, explained by straight dudes, web3 is the future, or a scam, or both, delete your dating apps and find romance offline, today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

More in Culture

Tiktok is full of bad health “tricks”

How the UFC explains the USA

Kevin Costner’s ego and the strange road to Horizon

Looking for your next great read? We’re here to help.

A new book tackles the splendor and squalor of reality TV

The Caribbean has a defense system against deadly hurricanes — but it’s vanishing

The Supreme Court handed down a hugely important First Amendment case today

How Hurricane Beryl became exactly what scientists expected

Take a mental break with the newest Vox crossword

America’s international public health plan is too focused on Americans

Making the Impossible Possible: 21-Year-Old Hillary Rodham’s Remarkable 1969 Wellesley College Commencement Speech

By maria popova.

“America,” Walt Whitman wrote in his remarkable essay on democracy and why a strong society is a feminist society , “if eligible at all to downfall and ruin, is eligible within herself, not without… Always inform yourself; always do the best you can; always vote.”

A century after Whitman, 21-year-old Hillary Clinton, then Hillary Rodham, took the stage at Wellesley College on May 31, 1969, and addressed the graduating class — her own class — in a remarkable commencement speech, later included in In Our Own Words: Extraordinary Speeches of the American Century ( public library ). It endures as a triumphant testament to idealism unblunted by half a century of fighting on the front lines of the common good, and calls to mind Albert Camus’s insistence that “real generosity toward the future lies in giving all to the present.”

“We are, all of us, exploring a world that none of us even understands and attempting to create within that uncertainty,” Clinton tells her classmates as they set out to enter and shape the world in an era of at least as much sociocultural tumult and recalibration as our own. “For too long,” she urges, “our leaders have viewed politics as the art of the possible. And the challenge now is to practice politics as the art of making what appears to be impossible possible.” Facing the gap between her generation’s expectations and their reality, young Clinton celebrates it as a source of “divine discontent,” the supreme creative fuel, rather than a source of cynicism, the ultimate form of resignation : “It wasn’t a discouraging gap and it didn’t turn us into cynical, bitter old women at the age of 18. It just inspired us to do something about that gap.”

Perhaps the greatest gift of her speech is contained in one sentence which perfectly illuminates the central ethos that has been animating Clinton’s life for the half century since: “If the only tool we have ultimately to use is our lives, so we use it in the way we can by choosing a way to live that will demonstrate the way we feel and the way we know.”

In a sentiment that calls to mind Ursula K. Le Guin’s abiding wisdom on the magic of real human communication , Clinton leans on the poetic to make her political and humane point: “Words have a funny way of trapping our minds on the way to our tongues but there are necessary means even in this multimedia age for attempting to come to grasps with some of the inarticulate maybe even inarticulable things that we’re feeling.”

She speaks of what it means to have “integrity, the courage to be whole, to try to mold an entire person in this particular context, living in relation to one another in the full poetry of existence.” And she ends with an exquisite poem by the unduly forgotten poet Nancy Scheibner — a poem ablaze with astonishing prescience, with lines like “My entrance into the world of so-called ‘social problems’ / Must be with quiet laughter, or not at all. / The hollow men of anger and bitterness / The bountiful ladies of righteous degradation / All must be left to a bygone age.”

May this recording, courtesy of Wellesley College and Clinton’s official With Her podcast hosted by Max Linsky, remind us of the bygone age and the hollow men we must most urgently leave behind as we make the impossible possible.