Chapter 12. Focus Groups

Introduction.

Focus groups are a particular and special form of interviewing in which the interview asks focused questions of a group of persons, optimally between five and eight. This group can be close friends, family members, or complete strangers. They can have a lot in common or nothing in common. Unlike one-on-one interviews, which can probe deeply, focus group questions are narrowly tailored (“focused”) to a particular topic and issue and, with notable exceptions, operate at the shallow end of inquiry. For example, market researchers use focus groups to find out why groups of people choose one brand of product over another. Because focus groups are often used for commercial purposes, they sometimes have a bit of a stigma among researchers. This is unfortunate, as the focus group is a helpful addition to the qualitative researcher’s toolkit. Focus groups explicitly use group interaction to assist in the data collection. They are particularly useful as supplements to one-on-one interviews or in data triangulation. They are sometimes used to initiate areas of inquiry for later data collection methods. This chapter describes the main forms of focus groups, lays out some key differences among those forms, and provides guidance on how to manage focus group interviews.

Focus Groups: What Are They and When to Use Them

As interviews, focus groups can be helpfully distinguished from one-on-one interviews. The purpose of conducting a focus group is not to expand the number of people one interviews: the focus group is a different entity entirely. The focus is on the group and its interactions and evaluations rather than on the individuals in that group. If you want to know how individuals understand their lives and their individual experiences, it is best to ask them individually. If you want to find out how a group forms a collective opinion about something (whether a product or an event or an experience), then conducting a focus group is preferable. The power of focus groups resides in their being both focused and oriented to the group . They are best used when you are interested in the shared meanings of a group or how people discuss a topic publicly or when you want to observe the social formation of evaluations. The interaction of the group members is an asset in this method of data collection. If your questions would not benefit from group interaction, this is a good indicator that you should probably use individual interviews (chapter 11). Avoid using focus groups when you are interested in personal information or strive to uncover deeply buried beliefs or personal narratives. In general, you want to avoid using focus groups when the subject matter is polarizing, as people are less likely to be honest in a group setting. There are a few exceptions, such as when you are conducting focus groups with people who are not strangers and/or you are attempting to probe deeply into group beliefs and evaluations. But caution is warranted in these cases. [1]

As with interviewing in general, there are many forms of focus groups. Focus groups are widely used by nonresearchers, so it is important to distinguish these uses from the research focus group. Businesses routinely employ marketing focus groups to test out products or campaigns. Jury consultants employ “mock” jury focus groups, testing out legal case strategies in advance of actual trials. Organizations of various kinds use focus group interviews for program evaluation (e.g., to gauge the effectiveness of a diversity training workshop). The research focus group has many similarities with all these uses but is specifically tailored to a research (rather than applied) interest. The line between application and research use can be blurry, however. To take the case of evaluating the effectiveness of a diversity training workshop, the same interviewer may be conducting focus group interviews both to provide specific actionable feedback for the workshop leaders (this is the application aspect) and to learn more about how people respond to diversity training (an interesting research question with theoretically generalizable results).

When forming a focus group, there are two different strategies for inclusion. Diversity focus groups include people with diverse perspectives and experiences. This helps the researcher identify commonalities across this diversity and/or note interactions across differences. What kind of diversity to capture depends on the research question, but care should be taken to ensure that those participating are not set up for attack from other participants. This is why many warn against diversity focus groups, especially around politically sensitive topics. The other strategy is to build a convergence focus group , which includes people with similar perspectives and experiences. These are particularly helpful for identifying shared patterns and group consensus. The important thing is to closely consider who will be invited to participate and what the composition of the group will be in advance. Some review of sampling techniques (see chapter 5) may be helpful here.

Moderating a focus group can be a challenge (more on this below). For this reason, confining your group to no more than eight participants is recommended. You probably want at least four persons to capture group interaction. Fewer than four participants can also make it more difficult for participants to remain (relatively) anonymous—there is less of a group in which to hide. There are exceptions to these recommendations. You might want to conduct a focus group with a naturally occurring group, as in the case of a family of three, a social club of ten, or a program of fifteen. When the persons know one another, the problems of too few for anonymity don’t apply, and although ten to fifteen can be unwieldy to manage, there are strategies to make this possible. If you really are interested in this group’s dynamic (not just a set of random strangers’ dynamic), then you will want to include all its members or as many as are willing and able to participate.

There are many benefits to conducting focus groups, the first of which is their interactivity. Participants can make comparisons, can elaborate on what has been voiced by another, and can even check one another, leading to real-time reevaluations. This last benefit is one reason they are sometimes employed specifically for consciousness raising or building group cohesion. This form of data collection has an activist application when done carefully and appropriately. It can be fun, especially for the participants. Additionally, what does not come up in a focus group, especially when expected by the researcher, can be very illuminating.

Many of these benefits do incur costs, however. The multiplicity of voices in a good focus group interview can be overwhelming both to moderate and later to transcribe. Because of the focused nature, deep probing is not possible (or desirable). You might only get superficial thinking or what people are willing to put out there publicly. If that is what you are interested in, good. If you want deeper insight, you probably will not get that here. Relatedly, extreme views are often suppressed, and marginal viewpoints are unspoken or, if spoken, derided. You will get the majority group consensus and very little of minority viewpoints. Because people will be engaged with one another, there is the possibility of cut-off sentences, making it even more likely to hear broad brush themes and not detailed specifics. There really is very little opportunity for specific follow-up questions to individuals. Reading over a transcript, you may be frustrated by avenues of inquiry that were foreclosed early.

Some people expect that conducting focus groups is an efficient form of data collection. After all, you get to hear from eight people instead of just one in the same amount of time! But this is a serious misunderstanding. What you hear in a focus group is one single group interview or discussion. It is not the same thing at all as conducting eight single one-hour interviews. Each focus group counts as “one.” Most likely, you will need to conduct several focus groups, and you can design these as comparisons to one another. For example, the American Sociological Association (ASA) Task Force on First-Generation and Working-Class Persons in Sociology began its study of the impact of class in sociology by conducting five separate focus groups with different groups of sociologists: graduate students, faculty (in general), community college faculty, faculty of color, and a racially diverse group of students and faculty. Even though the total number of participants was close to forty, the “number” of cases was five. It is highly recommended that when employing focus groups, you plan on composing more than one and at least three. This allows you to take note of and potentially discount findings from a group with idiosyncratic dynamics, such as where a particularly dominant personality silences all other voices. In other words, putting all your eggs into a single focus group basket is not a good idea.

How to Conduct a Focus Group Interview/Discussion

Advance preparations.

Once you have selected your focus groups and set a date and time, there are a few things you will want to plan out before meeting.

As with interviews, you begin by creating an interview (or discussion) guide. Where a good one-on-one interview guide should include ten to twelve main topics with possible prompts and follow-ups (see the example provided in chapter 11), the focus group guide should be more narrowly tailored to a single focus or topic area. For example, a focus might be “How students coped with online learning during the pandemic,” and a series of possible questions would be drafted that would help prod participants to think about and discuss this topic. These questions or discussion prompts can be creative and may include stimulus materials (watching a video or hearing a story) or posing hypotheticals. For example, Cech ( 2021 ) has a great hypothetical, asking what a fictional character should do: keep his boring job in computers or follow his passion and open a restaurant. You can ask a focus group this question and see what results—how the group comes to define a “good job,” what questions they ask about the hypothetical (How boring is his job really? Does he hate getting up in the morning, or is it more of an everyday tedium? What kind of financial support will he have if he quits? Does he even know how to run a restaurant?), and how they reach a consensus or create clear patterns of disagreement are all interesting findings that can be generated through this technique.

As with the above example (“What should Joe do?”), it is best to keep the questions you ask simple and easily understood by everyone. Thinking about the sequence of the questions/prompts is important, just as it is in conducting any interviews.

Avoid embarrassing questions. Always leave an out for the “I have a friend who X” response rather than pushing people to divulge personal information. Asking “How do you think students coped?” is better than “How did you cope?” Chances are, some participants will begin talking about themselves without you directly asking them to do so, but allowing impersonal responses here is good. The group itself will determine how deep and how personal it wants to go. This is not the time or place to push anyone out of their comfort zone!

Of course, people have different levels of comfort talking publicly about certain topics. You will have provided detailed information to your focus group participants beforehand and secured consent. But even so, the conversation may take a turn that makes someone uncomfortable. Be on the lookout for this, and remind everyone of their ability to opt out—to stay silent or to leave if necessary. Rather than call attention to anyone in this way, you also want to let everyone know they are free to walk around—to get up and get coffee (more on this below) or use the restroom or just step out of the room to take a call. Of course, you don’t really want anyone to do any of these things, and chances are everyone will stay seated during the hour, but you should leave this “out” for those who need it.

Have copies of consent forms and any supplemental questionnaire (e.g., demographic information) you are using prepared in advance. Ask a friend or colleague to assist you on the day of the focus group. They can be responsible for making sure the recording equipment is functioning and may even take some notes on body language while you are moderating the discussion. Order food (coffee or snacks) for the group. This is important! Having refreshments will be appreciated by your participants and really damps down the anxiety level. Bring name tags and pens. Find a quiet welcoming space to convene. Often this is a classroom where you move chairs into a circle, but public libraries often have meeting rooms that are ideal places for community members to meet. Be sure that the space allows for food.

Researcher Note

When I was designing my research plan for studying activist groups, I consulted one of the best qualitative researchers I knew, my late friend Raphael Ezekiel, author of The Racist Mind . He looked at my plan to hand people demographic surveys at the end of the meetings I planned to observe and said, “This methodology is missing one crucial thing.” “What?” I asked breathlessly, anticipating some technical insider tip. “Chocolate!” he answered. “They’ll be tired, ready to leave when you ask them to fill something out. Offer an incentive, and they will stick around.” It worked! As the meetings began to wind down, I would whip some bags of chocolate candies out of my bag. Everyone would stare, and I’d say they were my thank-you gift to anyone who filled out my survey. Once I learned to include some sugar-free candies for diabetics, my typical response rate was 100 percent. (And it gave me an additional class-culture data point by noticing who chose which brand; sure enough, Lindt balls went faster at majority professional-middle-class groups, and Hershey’s minibars went faster at majority working-class groups.)

—Betsy Leondar-Wright, author of Missing Class , coauthor of The Color of Wealth , associate professor of sociology at Lasell University, and coordinator of staffing at the Mission Project for Class Action

During the Focus Group

As people arrive, greet them warmly, and make sure you get a signed consent form (if not in advance). If you are using name tags, ask them to fill one out and wear it. Let them get food and find a seat and do a little chatting, as they might wish. Once seated, many focus group moderators begin with a relevant icebreaker. This could be simple introductions that have some meaning or connection to the focus. In the case of the ASA task force focus groups discussed above, we asked people to introduce themselves and where they were working/studying (“Hi, I’m Allison, and I am a professor at Oregon State University”). You will also want to introduce yourself and the study in simple terms. They’ve already read the consent form, but you would be surprised at how many people ignore the details there or don’t remember them. Briefly talking about the study and then letting people ask any follow-up questions lays a good foundation for a successful discussion, as it reminds everyone what the point of the event is.

Focus groups should convene for between forty-five and ninety minutes. Of course, you must tell the participants the time you have chosen in advance, and you must promptly end at the time allotted. Do not make anyone nervous by extending the time. Let them know at the outset that you will adhere to this timeline. This should reduce the nervous checking of phones and watches and wall clocks as the end time draws near.

Set ground rules and expectations for the group discussion. My preference is to begin with a general question and let whoever wants to answer it do so, but other moderators expect each person to answer most questions. Explain how much cross-talk you will permit (or encourage). Again, my preference is to allow the group to pick up the ball and run with it, so I will sometimes keep my head purposefully down so that they engage with one another rather than me, but I have seen other moderators take a much more engaged position. Just be clear at the outset about what your expectations are. You may or may not want to explain how the group should deal with those who would dominate the conversation. Sometimes, simply stating at the outset that all voices should be heard is enough to create a more egalitarian discourse. Other times, you will have to actively step in to manage (moderate) the exchange to allow more voices to be heard. Finally, let people know they are free to get up to get more coffee or leave the room as they need (if you are OK with this). You may ask people to refrain from using their phones during the duration of the discussion. That is up to you too.

Either before or after the introductions (your call), begin recording the discussion with their collective permission and knowledge . If you have brought a friend or colleague to assist you (as you should), have them attend to the recording. Explain the role of your colleague to the group (e.g., they will monitor the recording and will take short notes throughout to help you when you read the transcript later; they will be a silent observer).

Once the focus group gets going, it may be difficult to keep up. You will need to make a lot of quick decisions during the discussion about whether to intervene or let it go unguided. Only you really care about the research question or topic, so only you will really know when the discussion is truly off topic. However you handle this, keep your “participation” to a minimum. According to Lune and Berg ( 2018:95 ), the moderator’s voice should show up in the transcript no more than 10 percent of the time. By the way, you should also ask your research assistant to take special note of the “intensity” of the conversation, as this may be lost in a transcript. If there are people looking overly excited or tapping their feet with impatience or nodding their heads in unison, you want some record of this for future analysis.

I’m not sure why this stuck with me, but I thought it would be interesting to share. When I was reviewing my plan for conducting focus groups with one of my committee members, he suggested that I give the participants their gift cards first. The incentive for participating in the study was a gift card of their choice, and typical processes dictate that participants must complete the study in order to receive their gift card. However, my committee member (who is Native himself) suggested I give it at the beginning. As a qualitative researcher, you build trust with the people you engage with. You are asking them to share their stories with you, their intimate moments, their vulnerabilities, their time. Not to mention that Native people are familiar with being academia’s subjects of interest with little to no benefit to be returned to them. To show my appreciation, one of the things I could do was to give their gifts at the beginning, regardless of whether or not they completed participating.

—Susanna Y. Park, PhD, mixed-methods researcher in public health and author of “How Native Women Seek Support as Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence: A Mixed-Methods Study”

After the Focus Group

Your “data” will be either fieldnotes taken during the focus group or, more desirably, transcripts of the recorded exchange. If you do not have permission to record the focus group discussion, make sure you take very clear notes during the exchange and then spend a few hours afterward filling them in as much as possible, creating a rich memo to yourself about what you saw and heard and experienced, including any notes about body language and interactions. Ideally, however, you will have recorded the discussion. It is still a good idea to spend some time immediately after the conclusion of the discussion to write a memo to yourself with all the things that may not make it into the written record (e.g., body language and interactions). This is also a good time to journal about or create a memo with your initial researcher reactions to what you saw, noting anything of particular interest that you want to come back to later on (e.g., “It was interesting that no one thought Joe should quit his job, but in the other focus group, half of the group did. I wonder if this has something to do with the fact that all the participants were first-generation college students. I should pay attention to class background here.”).

Please thank each of your participants in a follow-up email or text. Let them know you appreciated their time and invite follow-up questions or comments.

One of the difficult things about focus group transcripts is keeping speakers distinct. Eventually, you are going to be using pseudonyms for any publication, but for now, you probably want to know who said what. You can assign speaker numbers (“Speaker 1,” “Speaker 2”) and connect those identifications with particular demographic information in a separate document. Remember to clearly separate actual identifications (as with consent forms) to prevent breaches of anonymity. If you cannot identify a speaker when transcribing, you can write, “Unidentified Speaker.” Once you have your transcript(s) and memos and fieldnotes, you can begin analyzing the data (chapters 18 and 19).

Advanced: Focus Groups on Sensitive Topics

Throughout this chapter, I have recommended against raising sensitive topics in focus group discussions. As an introvert myself, I find the idea of discussing personal topics in a group disturbing, and I tend to avoid conducting these kinds of focus groups. And yet I have actually participated in focus groups that do discuss personal information and consequently have been of great value to me as a participant (and researcher) because of this. There are even some researchers who believe this is the best use of focus groups ( de Oliveira 2011 ). For example, Jordan et al. ( 2007 ) argue that focus groups should be considered most useful for illuminating locally sanctioned ways of talking about sensitive issues. So although I do not recommend the beginning qualitative researcher dive into deep waters before they can swim, this section will provide some guidelines for conducting focus groups on sensitive topics. To my mind, these are a minimum set of guidelines to follow when dealing with sensitive topics.

First, be transparent about the place of sensitive topics in your focus group. If the whole point of your focus group is to discuss something sensitive, such as how women gain support after traumatic sexual assault events, make this abundantly clear in your consent form and recruiting materials. It is never appropriate to blindside participants with sensitive or threatening topics .

Second, create a confidentiality form (figure 12.2) for each participant to sign. These forms carry no legal weight, but they do create an expectation of confidentiality for group members.

In order to respect the privacy of all participants in [insert name of study here], all parties are asked to read and sign the statement below. If you have any reason not to sign, please discuss this with [insert your name], the researcher of this study, I, ________________________, agree to maintain the confidentiality of the information discussed by all participants and researchers during the focus group discussion.

Signature: _____________________________ Date: _____________________

Researcher’s Signature:___________________ Date:______________________

Figure 12.2 Confidentiality Agreement of Focus Group Participants

Third, provide abundant space for opting out of the discussion. Participants are, of course, always permitted to refrain from answering a question or to ask for the recording to be stopped. It is important that focus group members know they have these rights during the group discussion as well. And if you see a person who is looking uncomfortable or like they want to hide, you need to step in affirmatively and remind everyone of these rights.

Finally, if things go “off the rails,” permit yourself the ability to end the focus group. Debrief with each member as necessary.

Further Readings

Barbour, Rosaline. 2018. Doing Focus Groups . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. Written by a medical sociologist based in the UK, this is a good how-to guide for conducting focus groups.

Gibson, Faith. 2007. “Conducting Focus Groups with Children and Young People: Strategies for Success.” Journal of Research in Nursing 12(5):473–483. As the title suggests, this article discusses both methodological and practical concerns when conducting focus groups with children and young people and offers some tips and strategies for doing so effectively.

Hopkins, Peter E. 2007. “Thinking Critically and Creatively about Focus Groups.” Area 39(4):528–535. Written from the perspective of critical/human geography, Hopkins draws on examples from his own work conducting focus groups with Muslim men. Useful for thinking about positionality.

Jordan, Joanne, Una Lynch, Marianne Moutray, Marie-Therese O’Hagan, Jean Orr, Sandra Peake, and John Power. 2007. “Using Focus Groups to Research Sensitive Issues: Insights from Group Interviews on Nursing in the Northern Ireland ‘Troubles.’” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 6(4), 1–19. A great example of using focus groups productively around emotional or sensitive topics. The authors suggest that focus groups should be considered most useful for illuminating locally sanctioned ways of talking about sensitive issues.

Merton, Robert K., Marjorie Fiske, and Patricia L. Kendall. 1956. The Focused Interview: A Manual of Problems and Procedures . New York: Free Press. This is one of the first classic texts on conducting interviews, including an entire chapter devoted to the “group interview” (chapter 6).

Morgan, David L. 1986. “Focus Groups.” Annual Review of Sociology 22:129–152. An excellent sociological review of the use of focus groups, comparing and contrasting to both surveys and interviews, with some suggestions for improving their use and developing greater rigor when utilizing them.

de Oliveira, Dorca Lucia. 2011. “The Use of Focus Groups to Investigate Sensitive Topics: An Example Taken from Research on Adolescent Girls’ Perceptions about Sexual Risks.” Cien Saude Colet 16(7):3093–3102. Another example of discussing sensitive topics in focus groups. Here, the author explores using focus groups with teenage girls to discuss AIDS, risk, and sexuality as a matter of public health interest.

Peek, Lori, and Alice Fothergill. 2009. “Using Focus Groups: Lessons from Studying Daycare Centers, 9/11, and Hurricane Katrina.” Qualitative Research 9(1):31–59. An examination of the efficacy and value of focus groups by comparing three separate projects: a study of teachers, parents, and children at two urban daycare centers; a study of the responses of second-generation Muslim Americans to the events of September 11; and a collaborative project on the experiences of children and youth following Hurricane Katrina. Throughout, the authors stress the strength of focus groups with marginalized, stigmatized, or vulnerable individuals.

Wilson, Valerie. 1997. “Focus Groups: A Useful Qualitative Method for Educational Research?” British Educational Research Journal 23(2):209–224. A basic description of how focus groups work using an example from a study intended to inform initiatives in health education and promotion in Scotland.

- Note that I have included a few examples of conducting focus groups with sensitive issues in the “ Further Readings ” section and have included an “ Advanced: Focus Groups on Sensitive Topics ” section on this area. ↵

A focus group interview is an interview with a small group of people on a specific topic. “The power of focus groups resides in their being focused” (Patton 2002:388). These are sometimes framed as “discussions” rather than interviews, with a discussion “moderator.” Alternatively, the focus group is “a form of data collection whereby the researcher convenes a small group of people having similar attributes, experiences, or ‘focus’ and leads the group in a nondirective manner. The objective is to surface the perspectives of the people in the group with as minimal influence by the researcher as possible” (Yin 2016:336). See also diversity focus group and convergence focus group.

A form of focus group construction in which people with diverse perspectives and experiences are chosen for inclusion. This helps the researcher identify commonalities across this diversity and/or note interactions across differences. Contrast with a convergence focus group

A form of focus group construction in which people with similar perspectives and experiences are included. These are particularly helpful for identifying shared patterns and group consensus. Contrast with a diversity focus group .

Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods Copyright © 2023 by Allison Hurst is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Focus Group? | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

What is a Focus Group | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

Published on December 10, 2021 by Tegan George . Revised on June 22, 2023.

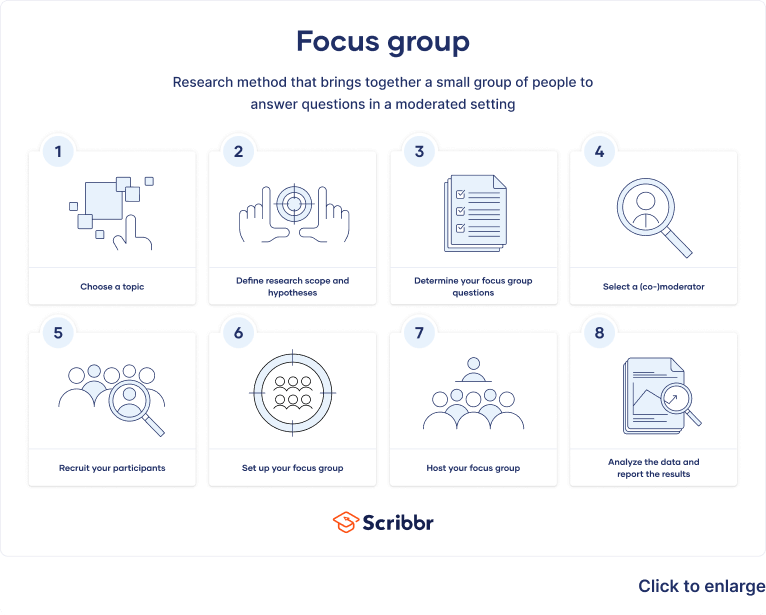

A focus group is a research method that brings together a small group of people to answer questions in a moderated setting. The group is chosen due to predefined demographic traits, and the questions are designed to shed light on a topic of interest.

Table of contents

What is a focus group, step 1: choose your topic of interest, step 2: define your research scope and hypotheses, step 3: determine your focus group questions, step 4: select a moderator or co-moderator, step 5: recruit your participants, step 6: set up your focus group, step 7: host your focus group, step 8: analyze your data and report your results, advantages and disadvantages of focus groups, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about focus groups.

Focus groups are a type of qualitative research . Observations of the group’s dynamic, their answers to focus group questions, and even their body language can guide future research on consumer decisions, products and services, or controversial topics.

Focus groups are often used in marketing, library science, social science, and user research disciplines. They can provide more nuanced and natural feedback than individual interviews and are easier to organize than experiments or large-scale surveys .

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Focus groups are primarily considered a confirmatory research technique . In other words, their discussion-heavy setting is most useful for confirming or refuting preexisting beliefs. For this reason, they are great for conducting explanatory research , where you explore why something occurs when limited information is available.

A focus group may be a good choice for you if:

- You’re interested in real-time, unfiltered responses on a given topic or in the dynamics of a discussion between participants

- Your questions are rooted in feelings or perceptions , and cannot easily be answered with “yes” or “no”

- You’re confident that a relatively small number of responses will answer your question

- You’re seeking directional information that will help you uncover new questions or future research ideas

- Structured interviews : The questions are predetermined in both topic and order.

- Semi-structured interviews : A few questions are predetermined, but other questions aren’t planned.

- Unstructured interviews : None of the questions are predetermined.

Differences between types of interviews

Make sure to choose the type of interview that suits your research best. This table shows the most important differences between the four types.

Topics favorable to focus groups

As a rule of thumb, research topics related to thoughts, beliefs, and feelings work well in focus groups. If you are seeking direction, explanation, or in-depth dialogue, a focus group could be a good fit.

However, if your questions are dichotomous or if you need to reach a large audience quickly, a survey may be a better option. If your question hinges upon behavior but you are worried about influencing responses, consider an observational study .

- If you want to determine whether the student body would regularly consume vegan food, a survey would be a great way to gauge student preferences.

However, food is much more than just consumption and nourishment and can have emotional, cultural, and other implications on individuals.

- If you’re interested in something less concrete, such as students’ perceptions of vegan food or the interplay between their choices at the dining hall and their feelings of homesickness or loneliness, perhaps a focus group would be best.

Once you have determined that a focus group is the right choice for your topic, you can start thinking about what you expect the group discussion to yield.

Perhaps literature already exists on your subject or a sufficiently similar topic that you can use as a starting point. If the topic isn’t well studied, use your instincts to determine what you think is most worthy of study.

Setting your scope will help you formulate intriguing hypotheses , set clear questions, and recruit the right participants.

- Are you interested in a particular sector of the population, such as vegans or non-vegans?

- Are you interested in including vegetarians in your analysis?

- Perhaps not all students eat at the dining hall. Will your study exclude those who don’t?

- Are you only interested in students who have strong opinions on the subject?

A benefit of focus groups is that your hypotheses can be open-ended. You can be open to a wide variety of opinions, which can lead to unexpected conclusions.

The questions that you ask your focus group are crucially important to your analysis. Take your time formulating them, paying special attention to phrasing. Be careful to avoid leading questions , which can affect your responses.

Overall, your focus group questions should be:

- Open-ended and flexible

- Impossible to answer with “yes” or “no” (questions that start with “why” or “how” are often best)

- Unambiguous, getting straight to the point while still stimulating discussion

- Unbiased and neutral

If you are discussing a controversial topic, be careful that your questions do not cause social desirability bias . Here, your respondents may lie about their true beliefs to mask any socially unacceptable or unpopular opinions. This and other demand characteristics can hurt your analysis and lead to several types of reseach bias in your results, particularly if your participants react in a different way once knowing they’re being observed. These include self-selection bias , the Hawthorne effect , the Pygmalion effect , and recall bias .

- Engagement questions make your participants feel comfortable and at ease: “What is your favorite food at the dining hall?”

- Exploration questions drill down to the focus of your analysis: “What pros and cons of offering vegan options do you see?”

- Exit questions pick up on anything you may have previously missed in your discussion: “Is there anything you’d like to mention about vegan options in the dining hall that we haven’t discussed?”

It is important to have more than one moderator in the room. If you would like to take the lead asking questions, select a co-moderator who can coordinate the technology, take notes, and observe the behavior of the participants.

If your hypotheses have behavioral aspects, consider asking someone else to be lead moderator so that you are free to take a more observational role.

Depending on your topic, there are a few types of moderator roles that you can choose from.

- The most common is the dual-moderator , introduced above.

- Another common option is the dueling-moderator style . Here, you and your co-moderator take opposing sides on an issue to allow participants to see different perspectives and respond accordingly.

Depending on your research topic, there are a few sampling methods you can choose from to help you recruit and select participants.

- Voluntary response sampling , such as posting a flyer on campus and finding participants based on responses

- Convenience sampling of those who are most readily accessible to you, such as fellow students at your university

- Stratified sampling of a particular age, race, ethnicity, gender identity, or other characteristic of interest to you

- Judgment sampling of a specific set of participants that you already know you want to include

Beware of sampling bias and selection bias , which can occur when some members of the population are more likely to be included than others.

Number of participants

In most cases, one focus group will not be sufficient to answer your research question. It is likely that you will need to schedule three to four groups. A good rule of thumb is to stop when you’ve reached a saturation point (i.e., when you aren’t receiving new responses to your questions).

Most focus groups have 6–10 participants. It’s a good idea to over-recruit just in case someone doesn’t show up. As a rule of thumb, you shouldn’t have fewer than 6 or more than 12 participants, in order to get the most reliable results.

Lastly, it’s preferable for your participants not to know you or each other, as this can bias your results.

A focus group is not just a group of people coming together to discuss their opinions. While well-run focus groups have an enjoyable and relaxed atmosphere, they are backed up by rigorous methods to provide robust observations.

Confirm a time and date

Be sure to confirm a time and date with your participants well in advance. Focus groups usually meet for 45–90 minutes, but some can last longer. However, beware of the possibility of wandering attention spans. If you really think your session needs to last longer than 90 minutes, schedule a few breaks.

Confirm whether it will take place in person or online

You will also need to decide whether the group will meet in person or online. If you are hosting it in person, be sure to pick an appropriate location.

- An uncomfortable or awkward location may affect the mood or level of participation of your group members.

- Online sessions are convenient, as participants can join from home, but they can also lessen the connection between participants.

As a general rule, make sure you are in a noise-free environment that minimizes distractions and interruptions to your participants.

Consent and ethical considerations

It’s important to take into account ethical considerations and informed consent when conducting your research. Informed consent means that participants possess all the information they need to decide whether they want to participate in the research before it starts. This includes information about benefits, risks, funding, and institutional approval.

Participants should also sign a release form that states that they are comfortable with being audio- or video-recorded. While verbal consent may be sufficient, it is best to ask participants to sign a form.

A disadvantage of focus groups is that they are too small to provide true anonymity to participants. Make sure that your participants know this prior to participating.

There are a few things you can do to commit to keeping information private. You can secure confidentiality by removing all identifying information from your report or offer to pseudonymize the data later. Data pseudonymization entails replacing any identifying information about participants with pseudonymous or false identifiers.

Preparation prior to participation

If there is something you would like participants to read, study, or prepare beforehand, be sure to let them know well in advance. It’s also a good idea to call them the day before to ensure they will still be participating.

Consider conducting a tech check prior to the arrival of your participants, and note any environmental or external factors that could affect the mood of the group that day. Be sure that you are organized and ready, as a stressful atmosphere can be distracting and counterproductive.

Starting the focus group

Welcome individuals to the focus group by introducing the topic, yourself, and your co-moderator, and go over any ground rules or suggestions for a successful discussion. It’s important to make your participants feel at ease and forthcoming with their responses.

Consider starting out with an icebreaker, which will allow participants to relax and settle into the space a bit. Your icebreaker can be related to your study topic or not; it’s just an exercise to get participants talking.

Leading the discussion

Once you start asking your questions, try to keep response times equal between participants. Take note of the most and least talkative members of the group, as well as any participants with particularly strong or dominant personalities.

You can ask less talkative members questions directly to encourage them to participate or ask participants questions by name to even the playing field. Feel free to ask participants to elaborate on their answers or to give an example.

As a moderator, strive to remain neutral . Refrain from reacting to responses, and be aware of your body language (e.g., nodding, raising eyebrows) and the possibility for observer bias . Active listening skills, such as parroting back answers or asking for clarification, are good methods to encourage participation and signal that you’re listening.

Many focus groups offer a monetary incentive for participants. Depending on your research budget, this is a nice way to show appreciation for their time and commitment. To keep everyone feeling fresh, consider offering snacks or drinks as well.

After concluding your focus group, you and your co-moderator should debrief, recording initial impressions of the discussion as well as any highlights, issues, or immediate conclusions you’ve drawn.

The next step is to transcribe and clean your data . Assign each participant a number or pseudonym for organizational purposes. Transcribe the recordings and conduct content analysis to look for themes or categories of responses. The categories you choose can then form the basis for reporting your results.

Just like other research methods, focus groups come with advantages and disadvantages.

- They are fairly straightforward to organize and results have strong face validity .

- They are usually inexpensive, even if you compensate participant.

- A focus group is much less time-consuming than a survey or experiment , and you get immediate results.

- Focus group results are often more comprehensible and intuitive than raw data.

Disadvantages

- It can be difficult to assemble a truly representative sample. Focus groups are generally not considered externally valid due to their small sample sizes.

- Due to the small sample size, you cannot ensure the anonymity of respondents, which may influence their desire to speak freely.

- Depth of analysis can be a concern, as it can be challenging to get honest opinions on controversial topics.

- There is a lot of room for error in the data analysis and high potential for observer dependency in drawing conclusions. You have to be careful not to cherry-pick responses to fit a prior conclusion.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Student’s t -distribution

- Normal distribution

- Null and Alternative Hypotheses

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Data cleansing

- Reproducibility vs Replicability

- Peer review

- Prospective cohort study

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Placebo effect

- Hawthorne effect

- Hindsight bias

- Affect heuristic

- Social desirability bias

A focus group is a research method that brings together a small group of people to answer questions in a moderated setting. The group is chosen due to predefined demographic traits, and the questions are designed to shed light on a topic of interest. It is one of 4 types of interviews .

As a rule of thumb, questions related to thoughts, beliefs, and feelings work well in focus groups. Take your time formulating strong questions, paying special attention to phrasing. Be careful to avoid leading questions , which can bias your responses.

There are various approaches to qualitative data analysis , but they all share five steps in common:

- Prepare and organize your data.

- Review and explore your data.

- Develop a data coding system.

- Assign codes to the data.

- Identify recurring themes.

The specifics of each step depend on the focus of the analysis. Some common approaches include textual analysis , thematic analysis , and discourse analysis .

Every dataset requires different techniques to clean dirty data , but you need to address these issues in a systematic way. You focus on finding and resolving data points that don’t agree or fit with the rest of your dataset.

These data might be missing values, outliers, duplicate values, incorrectly formatted, or irrelevant. You’ll start with screening and diagnosing your data. Then, you’ll often standardize and accept or remove data to make your dataset consistent and valid.

The four most common types of interviews are:

- Structured interviews : The questions are predetermined in both topic and order.

- Focus group interviews : The questions are presented to a group instead of one individual.

It’s impossible to completely avoid observer bias in studies where data collection is done or recorded manually, but you can take steps to reduce this type of bias in your research .

Scope of research is determined at the beginning of your research process , prior to the data collection stage. Sometimes called “scope of study,” your scope delineates what will and will not be covered in your project. It helps you focus your work and your time, ensuring that you’ll be able to achieve your goals and outcomes.

Defining a scope can be very useful in any research project, from a research proposal to a thesis or dissertation . A scope is needed for all types of research: quantitative , qualitative , and mixed methods .

To define your scope of research, consider the following:

- Budget constraints or any specifics of grant funding

- Your proposed timeline and duration

- Specifics about your population of study, your proposed sample size , and the research methodology you’ll pursue

- Any inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Any anticipated control , extraneous , or confounding variables that could bias your research if not accounted for properly.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. (2023, June 22). What is a Focus Group | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 11, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/focus-group/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, what is qualitative research | methods & examples, explanatory research | definition, guide, & examples, data collection | definition, methods & examples, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Qualitative Research:...

Qualitative Research: Introducing focus groups

- Related content

- Peer review

- Jenny Kitzinger , research fellow a

- a Glasgow University Media Group, Department of Sociology, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8LF

This paper introduces focus group methodology, gives advice on group composition, running the groups, and analysing the results. Focus groups have advantages for researchers in the field of health and medicine: they do not discriminate against people who cannot read or write and they can encourage participation from people reluctant to be interviewed on their own or who feel they have nothing to say.

This is the fifth in a series of seven articles describing non-quantitative techniques and showing their value in health research

**FIGURE OMITTED**

Rationale and uses of focus groups

Focus groups are a form of group interview that capitalises on communication between research participants in order to generate data. Although group interviews are often used simply as a quick and convenient way to collect data from several people simultaneously, focus groups explicitly use group interaction as part of the method. This means that instead of the researcher asking each person to respond to a question in turn, people are encouraged to talk to one another: asking questions, exchanging anecdotes and commenting on each other's experiences and points of view. 1 The method is particularly useful for exploring people's knowledge and experiences and can be used to examine not only what people think but how they think and why they think that way.

Focus groups were originally used within communication studies to explore the effects of films and television programmes, 2 and are a popular method for assessing health education messages and examining public understandings of illness and of health behaviours. 3 4 5 6 7 They are widely used to examine people's experiences of disease and of health services. 8 9 and are an effective technique for exploring the attitudes and needs of staff. 10 11

The idea behind the focus group method is that group processes can help people to explore and clarify their views in ways that would be less easily accessible in a one to one interview. Group discussion is particularly appropriate when the interviewer has a series of open ended questions and wishes to encourage research participants to explore the issues of importance to them, in their own vocabulary, generating their own questions and pursuing their own priorities. When group dynamics work well the participants work alongside the researcher, taking the research in new and often unexpected directions.

Group work also helps researchers tap into the many different forms of communication that people use in day to day interaction, including jokes, anecdotes, teasing, and arguing. Gaining access to such variety of communication is useful because people's knowledge and attitudes are not entirely encapsulated in reasoned responses to direct questions. Everyday forms of communication may tell us as much, if not more, about what people know or experience. In this sense focus groups reach the parts that other methods cannot reach, revealing dimensions of understanding that often remain untapped by more conventional data collection techniques.

Some potential sampling advantages with focus groups

Do not discriminate against people who cannot read or write

Can encourage participation from those who are reluctant to be interviewed on their own (such as those intimidated by the formality and isolation of a one to one interview)

Can encourage contributions from people who feel they have nothing to say or who are deemed “unresponsive patients” (but engage in the discussion generated by other group members)

Tapping into such interpersonal communication is also important because this can highlight (sub)cultural values or group norms. Through analysing the operation of humour, consensus, and dissent and examining different types of narrative used within the group, the researcher can identify shared and common knowledge. 12 This makes focus groups a data collection technique particularly sensitive to cultural variables—which is why it is so often used in cross cultural research and work with ethnic minorities. It also makes them useful in studies examining why different sections of the population make differential use of health services. 13 14 For similar reasons focus groups are useful for studying dominant cultural values (for example, exposing dominant narratives about sexuality 15 ) and for examining work place cultures—the ways in which, for example, staff cope with working with terminally ill patients or deal with the stresses of an accident and emergency department.

The downside of such group dynamics is that the articulation of group norms may silence individual voices of dissent. The presence of other research participants also compromises the confidentiality of the research session. For example, in group discussion with old people in long term residential care I found that some residents tried to prevent others from criticising staff—becoming agitated and repeatedly interrupting with cries of “you can't complain”; “the staff couldn't possibly be nicer.” On the one hand, such interactions highlighted certain aspects of these people's experiences. In this case, it showed some resident's fear of being “punished” by staff for, in the words of one woman, “being cheeky.” On the other hand, such group dynamics raise ethical issues (especially when the work is with “captive” populations) and may limit the usefulness of the data for certain purposes (Scottish Health Feedback, unpublished report).

However, it should not be assumed that groups are, by definition, inhibiting relative to the supposed privacy of an interview situation or that focus groups are inappropriate when researching sensitive topics. Quite the opposite may be true. Group work can actively facilitate the discussion of taboo topics because the less inhibited members of the group break the ice for shyer participants. Participants can also provide mutual support in expressing feelings that are common to their group but which they consider to deviate from mainstream culture (or the assumed culture of the researcher). This is particularly important when researching stigmatised or taboo experiences (for example, bereavement or sexual violence).

Focus group methods are also popular with those conducting action research and those concerned to “empower” research participants because the participants can become an active part of the process of analysis. Indeed, group participants may actually develop particular perspectives as a consequence of talking with other people who have similar experiences. For example, group dynamics can allow for a shift from personal, self blaming psychological explanations (“I'm stupid not to have understood what the doctor was telling me”; “I should have been stronger—I should have asked the right questions”) to the exploration of structural solutions (“If we've all felt confused about what we've been told maybe having a leaflet would help, or what about being able to take away a tape recording of the consultation?”).

Some researchers have also noted that group discussions can generate more critical comments than interviews. 16 For example, Geis et al, in their study of the lovers of people with AIDS, found that there were more angry comments about the medical community in the group discussions than in the individual interviews: “perhaps the synergism of the group ‘kept the anger going’ and allowed each participant to reinforce another's vented feelings of frustration and rage. 17 A method that facilitates the expression of criticism and the exploration of different types of solutions is invaluable if the aim of research is to improve services. Such a method is especially appropriate when working with particular disempowered patient populations who are often reluctant to give negative feedback or may feel that any problems result from their own inadequacies. 19

Conducting a focus group study

Sampling and group composition.

Focus group studies can consist of anything between half a dozen to over fifty groups, depending on the aims of the project and the resources available. Most studies involve just a few groups, and some combine this method with other data collection techniques. Focus group discussion of a questionnaire is ideal for testing the phrasing of questions and is also useful in explaining or exploring survey results. 19 20

Although it may be possible to work with a representative sample of a small population, most focus group studies use a theoretical sampling model (explained earlier in this series 21 ) whereby participants are selected to reflect a range of the total study population or to test particular hypotheses. Imaginative sampling is crucial. Most people now recognise class or ethnicity as important variables, and it is also worth considering other variables. For example, when exploring women's experiences of maternity care or cervical smears it may be advisable to include groups of lesbians or women who were sexually abused as children. 22

Most researchers recommend aiming for homogeneity within each group in order to capitalise on people's shared experiences. However, it can also be advantageous to bring together a diverse group (for example, from a range of professions) to maximise exploration of different perspectives within a group setting. However, it is important to be aware of how hierarchy within the group may affect the data (a nursing auxiliary, for example, is likely to be inhibited by the presence of a consultant from the same hospital).

The groups can be “naturally occurring” (for example, people who work together) or may be drawn together specifically for the research. Using preexisting groups allows observation of fragments of interactions that approximate to naturally occurring data (such as might have been collected by participant observation). An additional advantage is that friends and colleagues can relate each other's comments to incidents in their shared daily lives. They may challenge each other on contradictions between what they profess to believe and how they actually behave (for example, “how about that time you didn't use a glove while taking blood from a patient?”).

It would be naive to assume that group data are by definition “natural” in the sense that such interactions would have occurred without the group being convened for this purpose. Rather than assuming that sessions inevitably reflect everyday interactions (although sometimes they will), the group should be used to encourage people to engage with one another, formulate their ideas, and draw out the cognitive structures which previously have not been articulated.

Finally, it is important to consider the appropriateness of group work for different study populations and to think about how to overcome potential difficulties. Group work can facilitate collecting information from people who cannot read or write. The “safety in numbers factor” may also encourage the participation of those who are wary of an interviewer or who are anxious about talking. 23 However, group work can compound difficulties in communication if each person has a different disability. In the study assessing residential care for the elderly, I conducted a focus group that included one person who had impaired hearing, another with senile dementia, and a third with partial paralysis affecting her speech. This severely restricted interaction between research participants and confirmed some of the staff's predictions about the limitations of group work with this population. However, such problems could be resolved by thinking more carefully about the composition of the group, and sometimes group participants could help to translate for each other. It should also be noted that some of the old people who might have been unable to sustain a one to one interview were able to take part in the group, contributing intermittently. Even some residents who staff had suggested should be excluded from the research because they were “unresponsive” eventually responded to the lively conversations generated by their coresidents and were able to contribute their point of view. Communication difficulties should not rule out group work, but must be considered as a factor.

RUNNING THE GROUPS

Sessions should be relaxed: a comfortable setting, refreshments, and sitting round in a circle will help to establish the right atmosphere. The ideal group size is between four and eight people. Sessions may last one to two hours (or extend into a whole afternoon or a series of meetings). The facilitator should explain that the aim of focus groups is to encourage people to talk to each other rather than to address themselves to the researcher. The researcher may take a back seat at first, allowing for a type of “structured eavesdropping.” 24 Later on in the session, however, the researcher can adopt a more interventionist style: urging debate to continue beyond the stage it might otherwise have ended and encouraging the group to discuss the inconsistencies both between participants and within their own thinking. Disagreements within groups can be used to encourage participants to elucidate their point of view and to clarify why they think as they do. Differences between individual one off interviews have to be analysed by the researchers through armchair theorising; differences between members of focus groups should be explored in situ with the help of the research participants.

The facilitator may also use a range of group exercises. A common exercise consists of presenting the group with a series of statements on large cards. The group members are asked collectively to sort these cards into different piles depending on, for example, their degree of agreement or disagreement with that point of view or the importance they assign to that particular aspect of service. For example, I have used such cards to explore public understandings of HIV transmission (placing statements about “types” of people into different risk categories), old people's experiences of residential care (assigning degrees of importance to different statements about the quality of their care), and midwive's views of their professional responsibilities (placing a series of statements about midwive's roles along an agree-disagree continuum). Such exercises encourage participants to concentrate on one another (rather than on the group facilitator) and force them to explain their different perspectives. The final layout of the cards is less important than the discussion that it generates. 25 Researchers may also use such exercises as a way of checking out their own assessment of what has emerged from the group. In this case it is best to take along a series of blank cards and fill them out only towards the end of the session, using statements generated during the course of the discussion. Finally, it may be beneficial to present research participants with a brief questionnaire, or the opportunity to speak to the researcher privately, giving each one the opportunity to record private comments after the group session has been completed.

Ideally the group discussions should be tape recorded and transcribed. If this is not possible then it is vital to take careful notes and researchers may find it useful to involve the group in recording key issues on a flip chart.

ANALYSIS AND WRITING UP

Analysing focus groups is basically the same as analysing any other qualitative self report data. 21 26 At the very least, the researcher draws together and compares discussions of similar themes and examines how these relate to the variables within the sample population. In general, it is not appropriate to give percentages in reports of focus group data, and it is important to try to distinguish between individual opinions expressed in spite of the group from the actual group consensus. As in all qualitative analysis, deviant case analysis is important—that is, attention must be given to minority opinions and examples that do not fit with the researcher's overall theory.

The only distinct feature of working with focus group data is the need to indicate the impact of the group dynamic and analyse the sessions in ways that take full advantage of the interaction between research participants. In coding the script of a group discussion, it is worth using special categories for certain types of narrative, such as jokes and anecdotes, and types of interaction, such as “questions,” “deferring to the opinion of others,” “censorship,” or “changes of mind.” A focus group research report that is true to its data should also usually include at least some illustrations of the talk between participants, rather than simply presenting isolated quotations taken out of context.

Tapping into interpersonal communication can highlight cultural values or group norms

This paper has presented the factors to consider when designing or evaluating a focus group study. In particular, it has drawn attention to the overt exploitation and exploration of interactions in focus group discussion. Interaction between participants can be used to achieve seven main aims:

To highlight the respondent's attitudes, priorities, language, and framework of understanding;

To encourage research participants to generate and explore their own questions and develop their own analysis of common experiences;

To encourage a variety of communication from participants—tapping into a wide range and form of understanding;

To help to identify group norms and cultural values;

To provide insight into the operation of group social processes in the articulation of knowledge (for example, through the examination of what information is censured or muted within the group);

To encourage open conversation about embarrassing subjects and to permit the expression of criticism;

Generally to facilitate the expression of ideas and experiences that might be left underdeveloped in an interview and to illuminate the research participant's perspectives through the debate within the group.

Group data are neither more nor less authentic than data collected by other methods, but focus groups can be the most appropriate method for researching particular types of question. Direct observation may be more appropriate for studies of social roles and formal organisations 27 but focus groups are particularly suited to the study of attitudes and experiences. Interviews may be more appropriate for tapping into individual biographies, 27 but focus groups are more suitable for examining how knowledge, and more importantly, ideas, develop and operate within a given cultural context. Questionnaires are more appropriate for obtaining quantitative information and explaining how many people hold a certain (pre-defined) opinion; focus groups are better for exploring exactly how those opinions are constructed. Thus while surveys repeatedly identify gaps between health knowledge and health behaviour, only qualitative methods, such as focus groups, can actually fill these gaps and explain why these occur.

Focus groups are not an easy option. The data they generate can be as cumbersome as they are complex. Yet the method is basically straightforward and need not be intimidating for either the researcher or the researched. Perhaps the very best way of working out whether or not focus groups might be appropriate in any particular study is to try them out in practice.

Further reading

Morgan D. Focus groups as qualitative research. London: Sage, 1988.

Kreuger R. Focus groups: a practical guide for applied research. London: Sage, 1988.

- Kitzinger J

- Ritchie JE ,

- Herscovitch F ,

- Gordon-Sosby K ,

- Reynolds KD ,

- Manderson L

- Turnbull L ,

- McCallum J ,

- Gregory S ,

- Denning JD ,

- Verschelden C

- Zimmerman M ,

- Szumowski D ,

- Alvarez F ,

- Bhiromrut P ,

- DiMatteo M ,

Interviews and focus groups in qualitative research: an update for the digital age

Affiliations.

- 1 Senior Lecturer (Adult Nursing), School of Healthcare Sciences, Cardiff University.

- 2 Lecturer (Adult Nursing) and RCBC Wales Postdoctoral Research Fellow, School of Healthcare Sciences, Cardiff University.

- PMID: 30287965

- DOI: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2018.815

Qualitative research is used increasingly in dentistry, due to its potential to provide meaningful, in-depth insights into participants' experiences, perspectives, beliefs and behaviours. These insights can subsequently help to inform developments in dental practice and further related research. The most common methods of data collection used in qualitative research are interviews and focus groups. While these are primarily conducted face-to-face, the ongoing evolution of digital technologies, such as video chat and online forums, has further transformed these methods of data collection. This paper therefore discusses interviews and focus groups in detail, outlines how they can be used in practice, how digital technologies can further inform the data collection process, and what these methods can offer dentistry.

- How was the first women's group of cosmonauts created and why?

- What were the criteria for selection?

- How was training for space flight organized?

- Did women train under the same program as men?

- What tasks did you have to carry out during weightlessness training flights?

- Why did Soviet spacecraft designers rely so much on automation?

- What was your training on a spaceship simulator?

- What were the functions of various instruments on the instrument board?

- What were the differences for you as a pilot between flying an airplane and a space vehicle?

- What was the fate of the women's group after Tereshkova's flight?

- What role did the "space race" play in the development of Soviet cosmonautics?

- Why did Soviet cosmonautics begin to lag behind? Were the problems mostly technical or political?

- What was the role of secrecy in the Soviet space program?

- Was it often necessary to switch to manual guidance during docking?

- Why did not Soviet designers put a computer on board the first Soyuz?

- What is the optimal division of functions between human and machine?

- How did you become attracted to history of cosmonautics?

- Is there any distance between you as a participant of events and as a historian?

- How well is the history of cosmonautics being written today?

- What are the most important tasks for historians of cosmonautics today?

Gerovitch: How was the first women's group of cosmonauts created and why?

Ponomareva: These days in the course of my work I read a lot of memoirs of rocket designers and leaders of the space program, and I am struck by their attitude toward the development of cosmonautics. For some reason in those days it was believed that cosmonautics would develop at a great pace, that space flights would become regular and routine, that there would be built almost as many spacecraft as aircraft. I cannot figure out how such prominent, intelligent people, who knew all the complexity and the expense of the construction and use of space technology, could be so mistaken about the rate of development of space technology. Sergei Pavlovich Korolev [the chief designer of the Soviet space program] and other leaders believed that this technology would advance with seven-league strides. Perhaps their belief has a psychological or sociological explanation, but I cannot explain it. At the end of 1961, Korolev sent a letter, I think, to Nikolai Kamanin [assistant to the deputy Chief Commander of the Air Force in charge of cosmonaut training], in which he wrote that in the near future 60 cosmonauts of various professions would be needed, including five women. By then only 20 cosmonauts had been trained. Such were the premises on which our space program developed.

Different authors offer different opinions as to whose idea it was to select women - Korolev's or Kamanin's - but Korolev's letter came earlier than Kamanin made his statements. The space race also played a role here. Competition with the Americans gave a powerful impulse to such rapid development of space technology. In many memoirs one can find the idea that one must not allow lagging behind the Americans in the space program at all costs, especially in manned flights as the most impressive for the masses. At that time in America women tried to make their way into the Mercury program. They had not been invited, but some first-class women pilots began to act on their own. They reached the Vice President with their request to be allowed to participate in the space program. Nothing came out of it, but since the Americans did not hide anything, some publications about this appeared in the press.

Thus the decision to create a women's group was made at the top. Kamanin wrote in his diary that it was necessary to train women for space flight within 5-6 months. The women's group was selected in March 1962, and in August he already wanted to have trained cosmonauts and to send them into space. As usual, the construction of spacecraft was delayed, space suits were not ready, and therefore the training of the women's group was extended.

Gerovitch: What were the criteria for selection?

Ponomareva: At that time it was assumed that a cosmonaut could only be someone connected with aviation. At the beginning, they selected only combat pilots, even though later Korolev objected to this idea (he had initially supported it and, quite possibly, he was its author). Women were selected through aviation clubs in the European part of the Soviet Union. They mostly selected sports parachute jumpers, since in the Vostok spacecraft the cosmonaut had to land on a parachute. Parachute jumping is a complex skill, and therefore to train a novice in such a short time is impossible. A group of five was formed: four parachute jumpers of different skill levels and I. I had been trained as a pilot and had only eight jumps. I was a third category jumper; in comparison to the sports master Irina Solov'eva's 800 jumps, my eight jumps were nothing. Kamanin wanted to look over the documents of approximately 200 women candidates, and he asked the Central Committee of the Voluntary Association for the Advancement of the Army, Aviation, and the Navy to help. They could find only 58, and he was rather disappointed. In his diary he wrote that the Association's Central Committee had done a bad job and that 58 candidates was not enough. At that time, the view that everything connected to cosmonautics must be on a giant scale was typical. From those 58 applications the final five were selected.

Gerovitch: How was the training for space flight organized?

Ponomareva: In March 1962, we began training at the Cosmonaut Training Center. Then the town [i.e., the Star City] did not exist yet; there were only office buildings. We lived in a rehabilitation center and went through the very same training as did the first men cosmonauts. We were trained to withstand various conditions of space flight: weightlessness, G-loads, and so on.

When we arrived in the Center, we were enrolled as privates in the Soviet Air Force. We found ourselves in a military unit, in which we became a foreign element, with our different characters and different ideas. Our commanders had great difficulty dealing with us, since we did not understand the requirements of the service regulations, and we did not understand that orders had to be carried out. Military discipline in general was for us an alien and difficult concept.

Specialists from Korolev's Design Bureau visited us and gave lectures on the Vostok spacecraft. Many of them later became cosmonauts. Specialists from other organizations also gave lectures. Our training was completed by the end of 1962. We passed a State Examination. Kamanin, who supervised our training for space flights, came in and asked us whether we wanted to become regular officers of the Air Force. This question was definitely too difficult for very young ladies not accustomed to military discipline. We thought it over and talked to the guys from the first group.

By the way, the cosmonauts of the first group, as well as everyone in the military unit, were opposed to the women's group and to a woman's flight. But they all understood that to put a woman into the orbit first was a matter of our prestige and it had to be done. These days reasons of prestige are called into question, but back then such was the popular attitude, not just among the leaders of the space program. Everyone believed that new world records must be set.

Despite their opposition to the idea of a woman's flight, the cosmonauts of the first group treated us very well; they cared about us, they helped us, they taught us how to deceive physicians and how to pass tests easier. After consulting with them, we decided that it was necessary to join the staff of the Air Force; it was necessary to be like everybody else.

Jumping ahead a bit, I will mention that this would play an important role in the future fortunes of our group. After Tereshkova's flight the commanders of the Center wanted very much to get rid of us. But the fact that we were regular officers presented an obstacle to such efforts. It was not so easy to get rid of us. Later, however, they found a way, but this first time they failed.

Gerovitch: Did the women train under the same program as the men?