Problem-Based Learning (PBL)

What is Problem-Based Learning (PBL)? PBL is a student-centered approach to learning that involves groups of students working to solve a real-world problem, quite different from the direct teaching method of a teacher presenting facts and concepts about a specific subject to a classroom of students. Through PBL, students not only strengthen their teamwork, communication, and research skills, but they also sharpen their critical thinking and problem-solving abilities essential for life-long learning.

See also: Just-in-Time Teaching

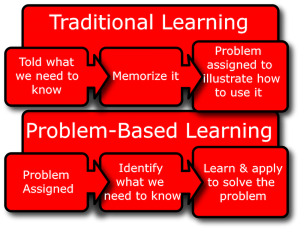

In implementing PBL, the teaching role shifts from that of the more traditional model that follows a linear, sequential pattern where the teacher presents relevant material, informs the class what needs to be done, and provides details and information for students to apply their knowledge to a given problem. With PBL, the teacher acts as a facilitator; the learning is student-driven with the aim of solving the given problem (note: the problem is established at the onset of learning opposed to being presented last in the traditional model). Also, the assignments vary in length from relatively short to an entire semester with daily instructional time structured for group work.

By working with PBL, students will:

- Become engaged with open-ended situations that assimilate the world of work

- Participate in groups to pinpoint what is known/ not known and the methods of finding information to help solve the given problem.

- Investigate a problem; through critical thinking and problem solving, brainstorm a list of unique solutions.

- Analyze the situation to see if the real problem is framed or if there are other problems that need to be solved.

How to Begin PBL

- Establish the learning outcomes (i.e., what is it that you want your students to really learn and to be able to do after completing the learning project).

- Find a real-world problem that is relevant to the students; often the problems are ones that students may encounter in their own life or future career.

- Discuss pertinent rules for working in groups to maximize learning success.

- Practice group processes: listening, involving others, assessing their work/peers.

- Explore different roles for students to accomplish the work that needs to be done and/or to see the problem from various perspectives depending on the problem (e.g., for a problem about pollution, different roles may be a mayor, business owner, parent, child, neighboring city government officials, etc.).

- Determine how the project will be evaluated and assessed. Most likely, both self-assessment and peer-assessment will factor into the assignment grade.

Designing Classroom Instruction

See also: Inclusive Teaching Strategies

- Take the curriculum and divide it into various units. Decide on the types of problems that your students will solve. These will be your objectives.

- Determine the specific problems that most likely have several answers; consider student interest.

- Arrange appropriate resources available to students; utilize other teaching personnel to support students where needed (e.g., media specialists to orientate students to electronic references).

- Decide on presentation formats to communicate learning (e.g., individual paper, group PowerPoint, an online blog, etc.) and appropriate grading mechanisms (e.g., rubric).

- Decide how to incorporate group participation (e.g., what percent, possible peer evaluation, etc.).

How to Orchestrate a PBL Activity

- Explain Problem-Based Learning to students: its rationale, daily instruction, class expectations, grading.

- Serve as a model and resource to the PBL process; work in-tandem through the first problem

- Help students secure various resources when needed.

- Supply ample class time for collaborative group work.

- Give feedback to each group after they share via the established format; critique the solution in quality and thoroughness. Reinforce to the students that the prior thinking and reasoning process in addition to the solution are important as well.

Teacher’s Role in PBL

See also: Flipped teaching

As previously mentioned, the teacher determines a problem that is interesting, relevant, and novel for the students. It also must be multi-faceted enough to engage students in doing research and finding several solutions. The problems stem from the unit curriculum and reflect possible use in future work situations.

- Determine a problem aligned with the course and your students. The problem needs to be demanding enough that the students most likely cannot solve it on their own. It also needs to teach them new skills. When sharing the problem with students, state it in a narrative complete with pertinent background information without excessive information. Allow the students to find out more details as they work on the problem.

- Place students in groups, well-mixed in diversity and skill levels, to strengthen the groups. Help students work successfully. One way is to have the students take on various roles in the group process after they self-assess their strengths and weaknesses.

- Support the students with understanding the content on a deeper level and in ways to best orchestrate the various stages of the problem-solving process.

The Role of the Students

See also: ADDIE model

The students work collaboratively on all facets of the problem to determine the best possible solution.

- Analyze the problem and the issues it presents. Break the problem down into various parts. Continue to read, discuss, and think about the problem.

- Construct a list of what is known about the problem. What do your fellow students know about the problem? Do they have any experiences related to the problem? Discuss the contributions expected from the team members. What are their strengths and weaknesses? Follow the rules of brainstorming (i.e., accept all answers without passing judgment) to generate possible solutions for the problem.

- Get agreement from the team members regarding the problem statement.

- Put the problem statement in written form.

- Solicit feedback from the teacher.

- Be open to changing the written statement based on any new learning that is found or feedback provided.

- Generate a list of possible solutions. Include relevant thoughts, ideas, and educated guesses as well as causes and possible ways to solve it. Then rank the solutions and select the solution that your group is most likely to perceive as the best in terms of meeting success.

- Include what needs to be known and done to solve the identified problems.

- Prioritize the various action steps.

- Consider how the steps impact the possible solutions.

- See if the group is in agreement with the timeline; if not, decide how to reach agreement.

- What resources are available to help (e.g., textbooks, primary/secondary sources, Internet).

- Determine research assignments per team members.

- Establish due dates.

- Determine how your group will present the problem solution and also identify the audience. Usually, in PBL, each group presents their solutions via a team presentation either to the class of other students or to those who are related to the problem.

- Both the process and the results of the learning activity need to be covered. Include the following: problem statement, questions, data gathered, data analysis, reasons for the solution(s) and/or any recommendations reflective of the data analysis.

- A well-stated problem and conclusion.

- The process undertaken by the group in solving the problem, the various options discussed, and the resources used.

- Your solution’s supporting documents, guests, interviews and their purpose to be convincing to your audience.

- In addition, be prepared for any audience comments and questions. Determine who will respond and if your team doesn’t know the answer, admit this and be open to looking into the question at a later date.

- Reflective thinking and transfer of knowledge are important components of PBL. This helps the students be more cognizant of their own learning and teaches them how to ask appropriate questions to address problems that need to be solved. It is important to look at both the individual student and the group effort/delivery throughout the entire process. From here, you can better determine what was learned and how to improve. The students should be asked how they can apply what was learned to a different situation, to their own lives, and to other course projects.

See also: Kirkpatrick Model: Four Levels of Learning Evaluation

I am a professor of Educational Technology. I have worked at several elite universities. I hold a PhD degree from the University of Illinois and a master's degree from Purdue University.

Similar Posts

Definitions of educational technology.

Educational Technology What is educational technology? There are a variety of definitions of educational technology. What is instructional design and technology? The Association for Educational Communications and Technology (AECT): Educational technology is the study…

Just-in-Time Teaching (JiTT)

Just-in-Time Teaching (JiTT) is an innovative approach to education that integrates real-life and virtual instruction to maximize the efficacy of both. This teaching method is created by a team led by university professor…

Definitions of The Addie Model

What is the ADDIE Model? This article attempts to explain the ADDIE model by providing different definitions. Basically, ADDIE is a conceptual framework. ADDIE is the most commonly used instructional design framework and…

Gagne’s Nine Events of Instruction

Heralded as a pioneer in educational instruction, Robert M. Gagné revolutionized instructional design principles with his WW II-era systematic approach, often referred to as the Gagné Assumption. The general idea, which seems familiar…

Using Bloom’s Taxonomy to Write Effective Learning Objectives: The ABCD Approach

Bloom’s Taxonomy offers a framework for categorizing educational goals that students are expected to attain as learning progresses. Learning objectives can be identified as the goals that should be achieved by a student at…

Adaptive Learning: What is It, What are its Benefits and How Does it Work?

People learn in many different ways. Adaptive learning has sought to address differences in ability by targeting teaching practices. The use of adaptive models, ranging from technological programs to intelligent systems, can be…

Center for Teaching

Teaching problem solving.

Print Version

Tips and Techniques

Expert vs. novice problem solvers, communicate.

- Have students identify specific problems, difficulties, or confusions . Don’t waste time working through problems that students already understand.

- If students are unable to articulate their concerns, determine where they are having trouble by asking them to identify the specific concepts or principles associated with the problem.

- In a one-on-one tutoring session, ask the student to work his/her problem out loud . This slows down the thinking process, making it more accurate and allowing you to access understanding.

- When working with larger groups you can ask students to provide a written “two-column solution.” Have students write up their solution to a problem by putting all their calculations in one column and all of their reasoning (in complete sentences) in the other column. This helps them to think critically about their own problem solving and helps you to more easily identify where they may be having problems. Two-Column Solution (Math) Two-Column Solution (Physics)

Encourage Independence

- Model the problem solving process rather than just giving students the answer. As you work through the problem, consider how a novice might struggle with the concepts and make your thinking clear

- Have students work through problems on their own. Ask directing questions or give helpful suggestions, but provide only minimal assistance and only when needed to overcome obstacles.

- Don’t fear group work ! Students can frequently help each other, and talking about a problem helps them think more critically about the steps needed to solve the problem. Additionally, group work helps students realize that problems often have multiple solution strategies, some that might be more effective than others

Be sensitive

- Frequently, when working problems, students are unsure of themselves. This lack of confidence may hamper their learning. It is important to recognize this when students come to us for help, and to give each student some feeling of mastery. Do this by providing positive reinforcement to let students know when they have mastered a new concept or skill.

Encourage Thoroughness and Patience

- Try to communicate that the process is more important than the answer so that the student learns that it is OK to not have an instant solution. This is learned through your acceptance of his/her pace of doing things, through your refusal to let anxiety pressure you into giving the right answer, and through your example of problem solving through a step-by step process.

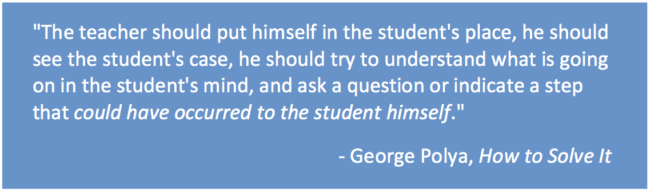

Experts (teachers) in a particular field are often so fluent in solving problems from that field that they can find it difficult to articulate the problem solving principles and strategies they use to novices (students) in their field because these principles and strategies are second nature to the expert. To teach students problem solving skills, a teacher should be aware of principles and strategies of good problem solving in his or her discipline .

The mathematician George Polya captured the problem solving principles and strategies he used in his discipline in the book How to Solve It: A New Aspect of Mathematical Method (Princeton University Press, 1957). The book includes a summary of Polya’s problem solving heuristic as well as advice on the teaching of problem solving.

Teaching Guides

- Online Course Development Resources

- Principles & Frameworks

- Pedagogies & Strategies

- Reflecting & Assessing

- Challenges & Opportunities

- Populations & Contexts

Quick Links

- Services for Departments and Schools

- Examples of Online Instructional Modules

Center for Teaching Innovation

Resource library.

- Establishing Community Agreements and Classroom Norms

- Sample group work rubric

- Problem-Based Learning Clearinghouse of Activities, University of Delaware

Problem-Based Learning

Problem-based learning (PBL) is a student-centered approach in which students learn about a subject by working in groups to solve an open-ended problem. This problem is what drives the motivation and the learning.

Why Use Problem-Based Learning?

Nilson (2010) lists the following learning outcomes that are associated with PBL. A well-designed PBL project provides students with the opportunity to develop skills related to:

- Working in teams.

- Managing projects and holding leadership roles.

- Oral and written communication.

- Self-awareness and evaluation of group processes.

- Working independently.

- Critical thinking and analysis.

- Explaining concepts.

- Self-directed learning.

- Applying course content to real-world examples.

- Researching and information literacy.

- Problem solving across disciplines.

Considerations for Using Problem-Based Learning

Rather than teaching relevant material and subsequently having students apply the knowledge to solve problems, the problem is presented first. PBL assignments can be short, or they can be more involved and take a whole semester. PBL is often group-oriented, so it is beneficial to set aside classroom time to prepare students to work in groups and to allow them to engage in their PBL project.

Students generally must:

- Examine and define the problem.

- Explore what they already know about underlying issues related to it.

- Determine what they need to learn and where they can acquire the information and tools necessary to solve the problem.

- Evaluate possible ways to solve the problem.

- Solve the problem.

- Report on their findings.

Getting Started with Problem-Based Learning

- Articulate the learning outcomes of the project. What do you want students to know or be able to do as a result of participating in the assignment?

- Create the problem. Ideally, this will be a real-world situation that resembles something students may encounter in their future careers or lives. Cases are often the basis of PBL activities. Previously developed PBL activities can be found online through the University of Delaware’s PBL Clearinghouse of Activities .

- Establish ground rules at the beginning to prepare students to work effectively in groups.

- Introduce students to group processes and do some warm up exercises to allow them to practice assessing both their own work and that of their peers.

- Consider having students take on different roles or divide up the work up amongst themselves. Alternatively, the project might require students to assume various perspectives, such as those of government officials, local business owners, etc.

- Establish how you will evaluate and assess the assignment. Consider making the self and peer assessments a part of the assignment grade.

Nilson, L. B. (2010). Teaching at its best: A research-based resource for college instructors (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- TA Resources

- Teaching Consultation

- Teaching Portfolio Program

- Grad Academy for College Teaching

- Faculty Events

- The Art of Teaching

- 2022 Illinois Summer Teaching Institute

- Large Classes

- Leading Discussions

- Laboratory Classes

- Lecture-Based Classes

- Planning a Class Session

- Questioning Strategies

- Classroom Assessment Techniques (CATs)

- Problem-Based Learning (PBL)

- The Case Method

- Community-Based Learning: Service Learning

- Group Learning

- Just-in-Time Teaching

- Creating a Syllabus

- Motivating Students

- Dealing With Cheating

- Discouraging & Detecting Plagiarism

- Diversity & Creating an Inclusive Classroom

- Harassment & Discrimination

- Professional Conduct

- Foundations of Good Teaching

- Student Engagement

- Assessment Strategies

- Course Design

- Student Resources

- Teaching Tips

- Graduate Teacher Certificate

- Certificate in Foundations of Teaching

- Teacher Scholar Certificate

- Certificate in Technology-Enhanced Teaching

- Master Course in Online Teaching (MCOT)

- 2022 Celebration of College Teaching

- 2023 Celebration of College Teaching

- Hybrid Teaching and Learning Certificate

- 2024 Celebration of College Teaching

- Classroom Observation Etiquette

- Teaching Philosophy Statement

- Pedagogical Literature Review

- Scholarship of Teaching and Learning

- Instructor Stories

- Podcast: Teach Talk Listen Learn

- Universal Design for Learning

Sign-Up to receive Teaching and Learning news and events

Problem-Based Learning (PBL) is a teaching method in which complex real-world problems are used as the vehicle to promote student learning of concepts and principles as opposed to direct presentation of facts and concepts. In addition to course content, PBL can promote the development of critical thinking skills, problem-solving abilities, and communication skills. It can also provide opportunities for working in groups, finding and evaluating research materials, and life-long learning (Duch et al, 2001).

PBL can be incorporated into any learning situation. In the strictest definition of PBL, the approach is used over the entire semester as the primary method of teaching. However, broader definitions and uses range from including PBL in lab and design classes, to using it simply to start a single discussion. PBL can also be used to create assessment items. The main thread connecting these various uses is the real-world problem.

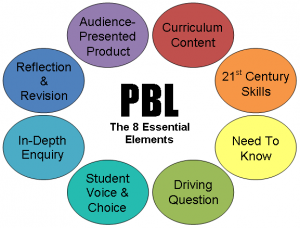

Any subject area can be adapted to PBL with a little creativity. While the core problems will vary among disciplines, there are some characteristics of good PBL problems that transcend fields (Duch, Groh, and Allen, 2001):

- The problem must motivate students to seek out a deeper understanding of concepts.

- The problem should require students to make reasoned decisions and to defend them.

- The problem should incorporate the content objectives in such a way as to connect it to previous courses/knowledge.

- If used for a group project, the problem needs a level of complexity to ensure that the students must work together to solve it.

- If used for a multistage project, the initial steps of the problem should be open-ended and engaging to draw students into the problem.

The problems can come from a variety of sources: newspapers, magazines, journals, books, textbooks, and television/ movies. Some are in such form that they can be used with little editing; however, others need to be rewritten to be of use. The following guidelines from The Power of Problem-Based Learning (Duch et al, 2001) are written for creating PBL problems for a class centered around the method; however, the general ideas can be applied in simpler uses of PBL:

- Choose a central idea, concept, or principle that is always taught in a given course, and then think of a typical end-of-chapter problem, assignment, or homework that is usually assigned to students to help them learn that concept. List the learning objectives that students should meet when they work through the problem.

- Think of a real-world context for the concept under consideration. Develop a storytelling aspect to an end-of-chapter problem, or research an actual case that can be adapted, adding some motivation for students to solve the problem. More complex problems will challenge students to go beyond simple plug-and-chug to solve it. Look at magazines, newspapers, and articles for ideas on the story line. Some PBL practitioners talk to professionals in the field, searching for ideas of realistic applications of the concept being taught.

- What will the first page (or stage) look like? What open-ended questions can be asked? What learning issues will be identified?

- How will the problem be structured?

- How long will the problem be? How many class periods will it take to complete?

- Will students be given information in subsequent pages (or stages) as they work through the problem?

- What resources will the students need?

- What end product will the students produce at the completion of the problem?

- Write a teacher's guide detailing the instructional plans on using the problem in the course. If the course is a medium- to large-size class, a combination of mini-lectures, whole-class discussions, and small group work with regular reporting may be necessary. The teacher's guide can indicate plans or options for cycling through the pages of the problem interspersing the various modes of learning.

- The final step is to identify key resources for students. Students need to learn to identify and utilize learning resources on their own, but it can be helpful if the instructor indicates a few good sources to get them started. Many students will want to limit their research to the Internet, so it will be important to guide them toward the library as well.

The method for distributing a PBL problem falls under three closely related teaching techniques: case studies, role-plays, and simulations. Case studies are presented to students in written form. Role-plays have students improvise scenes based on character descriptions given. Today, simulations often involve computer-based programs. Regardless of which technique is used, the heart of the method remains the same: the real-world problem.

Where can I learn more?

- PBL through the Institute for Transforming Undergraduate Education at the University of Delaware

- Duch, B. J., Groh, S. E, & Allen, D. E. (Eds.). (2001). The power of problem-based learning . Sterling, VA: Stylus.

- Grasha, A. F. (1996). Teaching with style: A practical guide to enhancing learning by understanding teaching and learning styles. Pittsburgh: Alliance Publishers.

Center for Innovation in Teaching & Learning

249 Armory Building 505 East Armory Avenue Champaign, IL 61820

217 333-1462

Email: [email protected]

Office of the Provost

Teaching Problem-Solving Skills

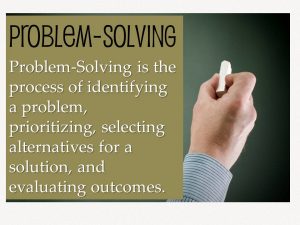

Many instructors design opportunities for students to solve “problems”. But are their students solving true problems or merely participating in practice exercises? The former stresses critical thinking and decision making skills whereas the latter requires only the application of previously learned procedures.

Problem solving is often broadly defined as "the ability to understand the environment, identify complex problems, review related information to develop, evaluate strategies and implement solutions to build the desired outcome" (Fissore, C. et al, 2021). True problem solving is the process of applying a method – not known in advance – to a problem that is subject to a specific set of conditions and that the problem solver has not seen before, in order to obtain a satisfactory solution.

Below you will find some basic principles for teaching problem solving and one model to implement in your classroom teaching.

Principles for teaching problem solving

- Model a useful problem-solving method . Problem solving can be difficult and sometimes tedious. Show students how to be patient and persistent, and how to follow a structured method, such as Woods’ model described below. Articulate your method as you use it so students see the connections.

- Teach within a specific context . Teach problem-solving skills in the context in which they will be used by students (e.g., mole fraction calculations in a chemistry course). Use real-life problems in explanations, examples, and exams. Do not teach problem solving as an independent, abstract skill.

- Help students understand the problem . In order to solve problems, students need to define the end goal. This step is crucial to successful learning of problem-solving skills. If you succeed at helping students answer the questions “what?” and “why?”, finding the answer to “how?” will be easier.

- Take enough time . When planning a lecture/tutorial, budget enough time for: understanding the problem and defining the goal (both individually and as a class); dealing with questions from you and your students; making, finding, and fixing mistakes; and solving entire problems in a single session.

- Ask questions and make suggestions . Ask students to predict “what would happen if …” or explain why something happened. This will help them to develop analytical and deductive thinking skills. Also, ask questions and make suggestions about strategies to encourage students to reflect on the problem-solving strategies that they use.

- Link errors to misconceptions . Use errors as evidence of misconceptions, not carelessness or random guessing. Make an effort to isolate the misconception and correct it, then teach students to do this by themselves. We can all learn from mistakes.

Woods’ problem-solving model

Define the problem.

- The system . Have students identify the system under study (e.g., a metal bridge subject to certain forces) by interpreting the information provided in the problem statement. Drawing a diagram is a great way to do this.

- Known(s) and concepts . List what is known about the problem, and identify the knowledge needed to understand (and eventually) solve it.

- Unknown(s) . Once you have a list of knowns, identifying the unknown(s) becomes simpler. One unknown is generally the answer to the problem, but there may be other unknowns. Be sure that students understand what they are expected to find.

- Units and symbols . One key aspect in problem solving is teaching students how to select, interpret, and use units and symbols. Emphasize the use of units whenever applicable. Develop a habit of using appropriate units and symbols yourself at all times.

- Constraints . All problems have some stated or implied constraints. Teach students to look for the words "only", "must", "neglect", or "assume" to help identify the constraints.

- Criteria for success . Help students consider, from the beginning, what a logical type of answer would be. What characteristics will it possess? For example, a quantitative problem will require an answer in some form of numerical units (e.g., $/kg product, square cm, etc.) while an optimization problem requires an answer in the form of either a numerical maximum or minimum.

Think about it

- “Let it simmer”. Use this stage to ponder the problem. Ideally, students will develop a mental image of the problem at hand during this stage.

- Identify specific pieces of knowledge . Students need to determine by themselves the required background knowledge from illustrations, examples and problems covered in the course.

- Collect information . Encourage students to collect pertinent information such as conversion factors, constants, and tables needed to solve the problem.

Plan a solution

- Consider possible strategies . Often, the type of solution will be determined by the type of problem. Some common problem-solving strategies are: compute; simplify; use an equation; make a model, diagram, table, or chart; or work backwards.

- Choose the best strategy . Help students to choose the best strategy by reminding them again what they are required to find or calculate.

Carry out the plan

- Be patient . Most problems are not solved quickly or on the first attempt. In other cases, executing the solution may be the easiest step.

- Be persistent . If a plan does not work immediately, do not let students get discouraged. Encourage them to try a different strategy and keep trying.

Encourage students to reflect. Once a solution has been reached, students should ask themselves the following questions:

- Does the answer make sense?

- Does it fit with the criteria established in step 1?

- Did I answer the question(s)?

- What did I learn by doing this?

- Could I have done the problem another way?

If you would like support applying these tips to your own teaching, CTE staff members are here to help. View the CTE Support page to find the most relevant staff member to contact.

- Fissore, C., Marchisio, M., Roman, F., & Sacchet, M. (2021). Development of problem solving skills with Maple in higher education. In: Corless, R.M., Gerhard, J., Kotsireas, I.S. (eds) Maple in Mathematics Education and Research. MC 2020. Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol 1414. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81698-8_15

- Foshay, R., & Kirkley, J. (1998). Principles for Teaching Problem Solving. TRO Learning Inc., Edina MN. (PDF) Principles for Teaching Problem Solving (researchgate.net)

- Hayes, J.R. (1989). The Complete Problem Solver. 2nd Edition. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Woods, D.R., Wright, J.D., Hoffman, T.W., Swartman, R.K., Doig, I.D. (1975). Teaching Problem solving Skills.

- Engineering Education. Vol 1, No. 1. p. 238. Washington, DC: The American Society for Engineering Education.

Catalog search

Teaching tip categories.

- Assessment and feedback

- Blended Learning and Educational Technologies

- Career Development

- Course Design

- Course Implementation

- Inclusive Teaching and Learning

- Learning activities

- Support for Student Learning

- Support for TAs

- Learning activities ,

- Faculty & Staff

Teaching problem solving

Strategies for teaching problem solving apply across disciplines and instructional contexts. First, introduce the problem and explain how people in your discipline generally make sense of the given information. Then, explain how to apply these approaches to solve the problem.

Introducing the problem

Explaining how people in your discipline understand and interpret these types of problems can help students develop the skills they need to understand the problem (and find a solution). After introducing how you would go about solving a problem, you could then ask students to:

- frame the problem in their own words

- define key terms and concepts

- determine statements that accurately represent the givens of a problem

- identify analogous problems

- determine what information is needed to solve the problem

Working on solutions

In the solution phase, one develops and then implements a coherent plan for solving the problem. As you help students with this phase, you might ask them to:

- identify the general model or procedure they have in mind for solving the problem

- set sub-goals for solving the problem

- identify necessary operations and steps

- draw conclusions

- carry out necessary operations

You can help students tackle a problem effectively by asking them to:

- systematically explain each step and its rationale

- explain how they would approach solving the problem

- help you solve the problem by posing questions at key points in the process

- work together in small groups (3 to 5 students) to solve the problem and then have the solution presented to the rest of the class (either by you or by a student in the group)

In all cases, the more you get the students to articulate their own understandings of the problem and potential solutions, the more you can help them develop their expertise in approaching problems in your discipline.

What Is Problem-Based Learning?

By Maureen Leming

Take a little bit of creativity, add a dash of innovation, and sprinkle in some critical thinking. This recipe makes for a well-rounded and engaged student who's ready to tackle life beyond the classroom. It's called Problem-Based Learning (PBL), and it teaches concepts and inspires lifelong learning at the same time.

This open-ended problem-based learning style presents students with a real-world issue and asks them to come up with a well-constructed answer. They can tap into online resources, use their previously-taught knowledge, and ask critical questions to brainstorm and present a solid solution. Unlike traditional learning, there might not be just one right answer, but the process encourages young minds to stay active and think for themselves.

We're all about the problem-based learning approach at The Hun School of Princeton . Through this article, you'll discover why — and what it looks like in real time.

An Overview of Problem-Based Learning

Problem-based learning (PBL) is a teaching style that pushes students to become the drivers of their learning education.

Problem-based learning uses complex, real-world issues as the classroom's subject matter, encouraging students to develop problem-solving skills and learn concepts instead of just absorbing facts.

This can take shape in a variety of different ways. For example, a problem-based learning project could involve students pitching ideas and creating their own business plans to solve a societal need. Students could work independently or in a group to conceptualize, design, and launch their innovative product in front of classmates and community leaders.

At the Hun School of Princeton, a problem-based learning mode is offered in conjunction with course content. This approach has been shown to help students develop critical thinking and communication skills as well as problem-solving abilities.

Aspects of Problem-Based Learning

Problem-based learning can be applied to any school subject, from social studies and literature to mathematics and science. No matter the field, a good problem-based learning approach should embody features like :

- Challenging students to understand classroom concepts on a deeper level.

- Pushing students to make decisions they're able to defend.

- Clearly connecting current course objectives to previous courses and knowledge.

- Encouraging students to work as a group to solve the complex issue at hand.

- Engaging students to solve an open-ended problem in multiple complex stages.

Benefits of Student-Led, Problem-Based Learning

Student-led learning is one of the most empowering ways to seat students at the forefront of their own educational experience.

It pushes students to be innovative, creative, open-minded, and logical. It also offers opportunities to collaborate with others in a hands-on, active way.

As part of our immersive educational model, we've discovered many benefits of problem-based learning:

- Promote self-learning : As a student-centered approach, problem-based learning pushes kids to take initiative and responsibility for their own learning. As they're pushed to use research and creativity, they develop skills that will benefit them into adulthood.

- Highly engaging : Instead of sitting back, listening and taking notes, problem-based learning puts students in the driver's seat. They have to stay sharp, apply critical thinking, and think outside the box to solve problems.

- Develop transferable skills: The abilities students develop don't just translate to one classroom or subject matter. They can be applied to a plethora of school subjects as well as life beyond, from taking leadership to solving real-world dilemmas.

- Improve teamwork abilities : Many problem-based learning projects have students collaborate with classmates to come up with a solution. This teamwork approach challenges kids to build skills like collaboration, communication, compromise, and listening.

- Encourage intrinsic rewards : With problem-based learning projects, the reward is much greater than simply an A on an assignment. Students earn the self-respect and satisfaction of knowing they've solved a riddle, created an innovative solution, or manufactured a tangible product.

Five Examples of Problem-Based Learning in Action

With a little context in mind, it's time to take a look at problem-based learning in the real world. One of the best parts of this learning style is that it's very flexible. You can adapt it to your classroom, content, and students. The following five examples are success stories of problem-based learning in action:

- Maritime discovery: Students explore maritime culture and history through visits to a nearby maritime museum. They're tasked with choosing a specific voyage, researching it, and crafting their own museum display. Throughout their studies, they'll create a captain's log, including mapping out voyages and building their own working sextant.

- Urban planning : Perfect for humanities classes, this example challenges students to observe and interview members of their community and determine the biggest local issue. They formulate practical solutions that they will then pitch to a panel of professional urban planners.

- Zoo habitats : This scientific example starts with a visit to a local zoo. Students use their observations and classroom knowledge to form teams and create research-supported habitat plans, presented to professional zoologists.

- Codebreakers : Instead of regular math lessons, let students lead with a code-breaking problem-based learning assignment. Students take on the role of a security agent tasked with decrypting a message, coding a new one in return, and presenting their findings to the classroom.

- Financial advisors : Challenge students to step into the role of a financial advisor and decide how to spend an allotted amount of money in a way that most benefits their community. Have them present their solution and explain their reasoning to the class.

The Hun School: Problem-Based Learning in Action

The Hun School of Princeton brings problem-based learning to life in our classrooms. Our collaborative school culture places a unique emphasis on hands-on, skilled-based education. NextTerm is just one example of problem-based learning in action here at The Hun School.

NextTerm gives students the opportunity to apply classroom knowledge to solve real-world problems on a local, national, and global scale. Take our Migration and Identity class, for example. Students in this course travel to the U.S.-Mexican border to speak directly to border patrol agents, ranchers, and immigrants in order to learn about the complex issue of migration straight from the source. Of course, this location is one of many that our students can explore. Our mandatory three-week mini-course , NextTerm , brings students beyond the campus and into a new environment, from domestic locations in Arizona, Montana, and Memphis to international locales in France and Ghana.

At our campus in Princeton, Hun students explore a relevant issue in collaboration with each other and field experts. They could be learning about the complexity of Ghanian economics or experiencing the modern-day impact of French history. This real-world immersion gives new power to their knowledge and helps them see the link between the classroom and the world at large. As they solve problems, Hun students can develop as individuals and teammates.

Ready to learn more about The Hun School approach and see problem-based learning strategies at work?

Inquire about Hun or schedule a tour to see problem-based learning in action!

Request More Information

Why Every Educator Needs to Teach Problem-Solving Skills

Strong problem-solving skills will help students be more resilient and will increase their academic and career success .

Want to learn more about how to measure and teach students’ higher-order skills, including problem solving, critical thinking, and written communication?

Problem-solving skills are essential in school, careers, and life.

Problem-solving skills are important for every student to master. They help individuals navigate everyday life and find solutions to complex issues and challenges. These skills are especially valuable in the workplace, where employees are often required to solve problems and make decisions quickly and effectively.

Problem-solving skills are also needed for students’ personal growth and development because they help individuals overcome obstacles and achieve their goals. By developing strong problem-solving skills, students can improve their overall quality of life and become more successful in their personal and professional endeavors.

Problem-Solving Skills Help Students…

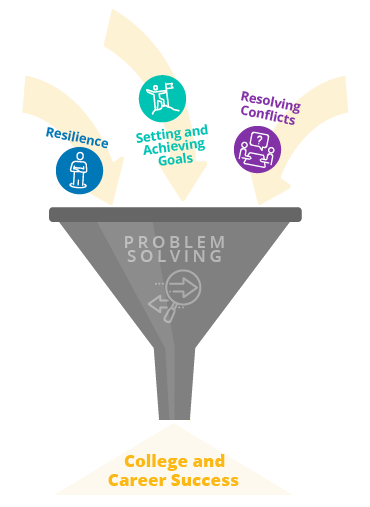

develop resilience.

Problem-solving skills are an integral part of resilience and the ability to persevere through challenges and adversity. To effectively work through and solve a problem, students must be able to think critically and creatively. Critical and creative thinking help students approach a problem objectively, analyze its components, and determine different ways to go about finding a solution.

This process in turn helps students build self-efficacy . When students are able to analyze and solve a problem, this increases their confidence, and they begin to realize the power they have to advocate for themselves and make meaningful change.

When students gain confidence in their ability to work through problems and attain their goals, they also begin to build a growth mindset . According to leading resilience researcher, Carol Dweck, “in a growth mindset, people believe that their most basic abilities can be developed through dedication and hard work—brains and talent are just the starting point. This view creates a love of learning and a resilience that is essential for great accomplishment.”

Set and Achieve Goals

Students who possess strong problem-solving skills are better equipped to set and achieve their goals. By learning how to identify problems, think critically, and develop solutions, students can become more self-sufficient and confident in their ability to achieve their goals. Additionally, problem-solving skills are used in virtually all fields, disciplines, and career paths, which makes them important for everyone. Building strong problem-solving skills will help students enhance their academic and career performance and become more competitive as they begin to seek full-time employment after graduation or pursue additional education and training.

Resolve Conflicts

In addition to increased social and emotional skills like self-efficacy and goal-setting, problem-solving skills teach students how to cooperate with others and work through disagreements and conflicts. Problem-solving promotes “thinking outside the box” and approaching a conflict by searching for different solutions. This is a very different (and more effective!) method than a more stagnant approach that focuses on placing blame or getting stuck on elements of a situation that can’t be changed.

While it’s natural to get frustrated or feel stuck when working through a conflict, students with strong problem-solving skills will be able to work through these obstacles, think more rationally, and address the situation with a more solution-oriented approach. These skills will be valuable for students in school, their careers, and throughout their lives.

Achieve Success

We are all faced with problems every day. Problems arise in our personal lives, in school and in our jobs, and in our interactions with others. Employers especially are looking for candidates with strong problem-solving skills. In today’s job market, most jobs require the ability to analyze and effectively resolve complex issues. Students with strong problem-solving skills will stand out from other applicants and will have a more desirable skill set.

In a recent opinion piece published by The Hechinger Report , Virgel Hammonds, Chief Learning Officer at KnowledgeWorks, stated “Our world presents increasingly complex challenges. Education must adapt so that it nurtures problem solvers and critical thinkers.” Yet, the “traditional K–12 education system leaves little room for students to engage in real-world problem-solving scenarios.” This is the reason that a growing number of K–12 school districts and higher education institutions are transforming their instructional approach to personalized and competency-based learning, which encourage students to make decisions, problem solve and think critically as they take ownership of and direct their educational journey.

Problem-Solving Skills Can Be Measured and Taught

Research shows that problem-solving skills can be measured and taught. One effective method is through performance-based assessments which require students to demonstrate or apply their knowledge and higher-order skills to create a response or product or do a task.

What Are Performance-Based Assessments?

With the No Child Left Behind Act (2002), the use of standardized testing became the primary way to measure student learning in the U.S. The legislative requirements of this act shifted the emphasis to standardized testing, and this led to a decline in nontraditional testing methods .

But many educators, policy makers, and parents have concerns with standardized tests. Some of the top issues include that they don’t provide feedback on how students can perform better, they don’t value creativity, they are not representative of diverse populations, and they can be disadvantageous to lower-income students.

While standardized tests are still the norm, U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona is encouraging states and districts to move away from traditional multiple choice and short response tests and instead use performance-based assessment, competency-based assessments, and other more authentic methods of measuring students abilities and skills rather than rote learning.

Performance-based assessments measure whether students can apply the skills and knowledge learned from a unit of study. Typically, a performance task challenges students to use their higher-order skills to complete a project or process. Tasks can range from an essay to a complex proposal or design.

Preview a Performance-Based Assessment

Want a closer look at how performance-based assessments work? Preview CAE’s K–12 and Higher Education assessments and see how CAE’s tools help students develop critical thinking, problem-solving, and written communication skills.

Performance-Based Assessments Help Students Build and Practice Problem-Solving Skills

In addition to effectively measuring students’ higher-order skills, including their problem-solving skills, performance-based assessments can help students practice and build these skills. Through the assessment process, students are given opportunities to practically apply their knowledge in real-world situations. By demonstrating their understanding of a topic, students are required to put what they’ve learned into practice through activities such as presentations, experiments, and simulations.

This type of problem-solving assessment tool requires students to analyze information and choose how to approach the presented problems. This process enhances their critical thinking skills and creativity, as well as their problem-solving skills. Unlike traditional assessments based on memorization or reciting facts, performance-based assessments focus on the students’ decisions and solutions, and through these tasks students learn to bridge the gap between theory and practice.

Performance-based assessments like CAE’s College and Career Readiness Assessment (CRA+) and Collegiate Learning Assessment (CLA+) provide students with in-depth reports that show them which higher-order skills they are strongest in and which they should continue to develop. This feedback helps students and their teachers plan instruction and supports to deepen their learning and improve their mastery of critical skills.

Explore CAE’s Problem-Solving Assessments

CAE offers performance-based assessments that measure student proficiency in higher-order skills including problem solving, critical thinking, and written communication.

- College and Career Readiness Assessment (CCRA+) for secondary education and

- Collegiate Learning Assessment (CLA+) for higher education.

Our solution also includes instructional materials, practice models, and professional development.

We can help you create a program to build students’ problem-solving skills that includes:

- Measuring students’ problem-solving skills through a performance-based assessment

- Using the problem-solving assessment data to inform instruction and tailor interventions

- Teaching students problem-solving skills and providing practice opportunities in real-life scenarios

- Supporting educators with quality professional development

Get started with our problem-solving assessment tools to measure and build students’ problem-solving skills today! These skills will be invaluable to students now and in the future.

Ready to Get Started?

Learn more about cae’s suite of products and let’s get started measuring and teaching students important higher-order skills like problem solving..

Problem based learning: a teacher's guide

December 10, 2021

Find out how teachers use problem-based learning models to improve engagement and drive attainment.

Main, P (2021, December 10). Problem based learning: a teacher's guide. Retrieved from https://www.structural-learning.com/post/problem-based-learning-a-teachers-guide

What is problem-based learning?

Problem-based learning (PBL) is a style of teaching that encourages students to become the drivers of their learning process . Problem-based learning involves complex learning issues from real-world problems and makes them the classroom's topic of discussion ; encouraging students to understand concepts through problem-solving skills rather than simply learning facts. When schools find time in the curriculum for this style of teaching it offers students an authentic vehicle for the integration of knowledge .

Embracing this pedagogical approach enables schools to balance subject knowledge acquisition with a skills agenda . Often used in medical education, this approach has equal significance in mainstream education where pupils can apply their knowledge to real-life problems.

PBL is not only helpful in learning course content , but it can also promote the development of problem-solving abilities , critical thinking skills , and communication skills while providing opportunities to work in groups , find and analyse research materials , and take part in life-long learning .

PBL is a student-centred teaching method in which students understand a topic by working in groups. They work out an open-ended problem , which drives the motivation to learn. These sorts of theories of teaching do require schools to invest time and resources into supporting self-directed learning. Not all curriculum knowledge is best acquired through this process, rote learning still has its place in certain situations. In this article, we will look at how we can equip our students to take more ownership of the learning process and utilise more sophisticated ways for the integration of knowledge .

Philosophical Underpinnings of PBL

Problem-Based Learning (PBL), with its roots in the philosophies of John Dewey, Maria Montessori, and Jerome Bruner, aligns closely with the social constructionist view of learning. This approach positions learners as active participants in the construction of knowledge, contrasting with traditional models of instruction where learners are seen as passive recipients of information.

Dewey, a seminal figure in progressive education, advocated for active learning and real-world problem-solving, asserting that learning is grounded in experience and interaction. In PBL, learners tackle complex, real-world problems, which mirrors Dewey's belief in the interconnectedness of education and practical life.

Montessori also endorsed learner-centric, self-directed learning, emphasizing the child's potential to construct their own learning experiences. This parallels with PBL’s emphasis on self-directed learning, where students take ownership of their learning process.

Jerome Bruner’s theories underscored the idea of learning as an active, social process. His concept of a 'spiral curriculum' – where learning is revisited in increasing complexity – can be seen reflected in the iterative problem-solving process in PBL.

Webb’s Depth of Knowledge (DOK) framework aligns with PBL as it encourages higher-order cognitive skills. The complex tasks in PBL often demand analytical and evaluative skills (Webb's DOK levels 3 and 4) as students engage with the problem, devise a solution, and reflect on their work.

The effectiveness of PBL is supported by psychological theories like the information processing theory, which highlights the role of active engagement in enhancing memory and recall. A study by Strobel and Van Barneveld (2009) found that PBL students show improved retention of knowledge, possibly due to the deep cognitive processing involved.

As cognitive scientist Daniel Willingham aptly puts it, "Memory is the residue of thought." PBL encourages learners to think critically and deeply, enhancing both learning and retention.

Here's a quick overview:

- John Dewey : Emphasized learning through experience and the importance of problem-solving.

- Maria Montessori : Advocated for child-centered, self-directed learning.

- Jerome Bruner : Underlined learning as a social process and proposed the spiral curriculum.

- Webb’s DOK : Supports PBL's encouragement of higher-order thinking skills.

- Information Processing Theory : Reinforces the notion that active engagement in PBL enhances memory and recall.

This deep-rooted philosophical and psychological framework strengthens the validity of the problem-based learning approach, confirming its beneficial role in promoting valuable cognitive skills and fostering positive student learning outcomes.

What are the characteristics of problem-based learning?

Adding a little creativity can change a topic into a problem-based learning activity. The following are some of the characteristics of a good PBL model:

- The problem encourages students to search for a deeper understanding of content knowledge;

- Students are responsible for their learning. PBL has a student-centred learning approach . Students' motivation increases when responsibility for the process and solution to the problem rests with the learner;

- The problem motivates pupils to gain desirable learning skills and to defend well-informed decisions ;

- The problem connects the content learning goals with the previous knowledge. PBL allows students to access, integrate and study information from multiple disciplines that might relate to understanding and resolving a specific problem—just as persons in the real world recollect and use the application of knowledge that they have gained from diverse sources in their life.

- In a multistage project, the first stage of the problem must be engaging and open-ended to make students interested in the problem. In the real world, problems are poorly-structured. Research suggests that well-structured problems make students less invested and less motivated in the development of the solution. The problem simulations used in problem-based contextual learning are less structured to enable students to make a free inquiry.

- In a group project, the problem must have some level of complexity that motivates students towards knowledge acquisition and to work together for finding the solution. PBL involves collaboration between learners. In professional life, most people will find themselves in employment where they would work productively and share information with others. PBL leads to the development of such essential skills . In a PBL session, the teacher would ask questions to make sure that knowledge has been shared between pupils;

- At the end of each problem or PBL, self and peer assessments are performed. The main purpose of assessments is to sharpen a variety of metacognitive processing skills and to reinforce self-reflective learning.

- Student assessments would evaluate student progress towards the objectives of problem-based learning. The learning goals of PBL are both process-based and knowledge-based. Students must be assessed on both these dimensions to ensure that they are prospering as intended from the PBL approach. Students must be able to identify and articulate what they understood and what they learned.

Why is Problem-based learning a significant skill?

Using Problem-Based Learning across a school promotes critical competence, inquiry , and knowledge application in social, behavioural and biological sciences. Practice-based learning holds a strong track record of successful learning outcomes in higher education settings such as graduates of Medical Schools.

Educational models using PBL can improve learning outcomes by teaching students how to implement theory into practice and build problem-solving skills. For example, within the field of health sciences education, PBL makes the learning process for nurses and medical students self-centred and promotes their teamwork and leadership skills. Within primary and secondary education settings, this model of teaching, with the right sort of collaborative tools , can advance the wider skills development valued in society.

At Structural Learning, we have been developing a self-assessment tool designed to monitor the progress of children. Utilising these types of teaching theories curriculum wide can help a school develop the learning behaviours our students will need in the workplace.

Curriculum wide collaborative tools include Writers Block and the Universal Thinking Framework . Along with graphic organisers, these tools enable children to collaborate and entertain different perspectives that they might not otherwise see. Putting learning in action by using the block building methodology enables children to reach their learning goals by experimenting and iterating.

How is problem-based learning different from inquiry-based learning?

The major difference between inquiry-based learning and PBL relates to the role of the teacher . In the case of inquiry-based learning, the teacher is both a provider of classroom knowledge and a facilitator of student learning (expecting/encouraging higher-order thinking). On the other hand, PBL is a deep learning approach, in which the teacher is the supporter of the learning process and expects students to have clear thinking, but the teacher is not the provider of classroom knowledge about the problem—the responsibility of providing information belongs to the learners themselves.

As well as being used systematically in medical education, this approach has significant implications for integrating learning skills into mainstream classrooms .

Using a critical thinking disposition inventory, schools can monitor the wider progress of their students as they apply their learning skills across the traditional curriculum. Authentic problems call students to apply their critical thinking abilities in new and purposeful ways. As students explain their ideas to one another, they develop communication skills that might not otherwise be nurtured.

Depending on the curriculum being delivered by a school, there may well be an emphasis on building critical thinking abilities in the classroom. Within the International Baccalaureate programs, these life-long skills are often cited in the IB learner profile . Critical thinking dispositions are highly valued in the workplace and this pedagogical approach can be used to harness these essential 21st-century skills.

What are the Benefits of Problem-Based Learning?

Student-led Problem-Based Learning is one of the most useful ways to make students drivers of their learning experience. It makes students creative, innovative, logical and open-minded. The educational practice of Problem-Based Learning also provides opportunities for self-directed and collaborative learning with others in an active learning and hands-on process. Below are the most significant benefits of problem-based learning processes:

- Self-learning: As a self-directed learning method, problem-based learning encourages children to take responsibility and initiative for their learning processes . As children use creativity and research, they develop skills that will help them in their adulthood.

- Engaging : Students don't just listen to the teacher, sit back and take notes. Problem-based learning processes encourages students to take part in learning activities, use learning resources , stay active , think outside the box and apply critical thinking skills to solve problems.

- Teamwork : Most of the problem-based learning issues involve students collaborative learning to find a solution. The educational practice of PBL builds interpersonal skills, listening and communication skills and improves the skills of collaboration and compromise.

- Intrinsic Rewards: In most problem-based learning projects, the reward is much bigger than good grades. Students gain the pride and satisfaction of finding an innovative solution, solving a riddle, or creating a tangible product.

- Transferable Skills: The acquisition of knowledge through problem-based learning strategies don't just help learners in one class or a single subject area. Students can apply these skills to a plethora of subject matter as well as in real life.

- Multiple Learning Opportunities : A PBL model offers an open-ended problem-based acquisition of knowledge, which presents a real-world problem and asks learners to come up with well-constructed responses. Students can use multiple sources such as they can access online resources, using their prior knowledge, and asking momentous questions to brainstorm and come up with solid learning outcomes. Unlike traditional approaches , there might be more than a single right way to do something, but this process motivates learners to explore potential solutions whilst staying active.

Embracing problem-based learning

Problem-based learning can be seen as a deep learning approach and when implemented effectively as part of a broad and balanced curriculum , a successful teaching strategy in education. PBL has a solid epistemological and philosophical foundation and a strong track record of success in multiple areas of study. Learners must experience problem-based learning methods and engage in positive solution-finding activities. PBL models allow learners to gain knowledge through real-world problems, which offers more strength to their understanding and helps them find the connection between classroom learning and the real world at large.

As they solve problems, students can evolve as individuals and team-mates. One word of caution, not all classroom tasks will lend themselves to this learning theory. Take spellings , for example, this is usually delivered with low-stakes quizzing through a practice-based learning model. PBL allows students to apply their knowledge creatively but they need to have a certain level of background knowledge to do this, rote learning might still have its place after all.

Key Concepts and considerations for school leaders

1. Problem Based Learning (PBL)

Problem-based learning (PBL) is an educational method that involves active student participation in solving authentic problems. Students are given a task or question that they must answer using their prior knowledge and resources. They then collaborate with each other to come up with solutions to the problem. This collaborative effort leads to deeper learning than traditional lectures or classroom instruction .

Key question: Inside a traditional curriculum , what opportunities across subject areas do you immediately see?

2. Deep Learning

Deep learning is a term used to describe the ability to learn concepts deeply. For example, if you were asked to memorize a list of numbers, you would probably remember the first five numbers easily, but the last number would be difficult to recall. However, if you were taught to understand the concept behind the numbers, you would be able to remember the last number too.

Key question: How will you make sure that students use a full range of learning styles and learning skills ?

3. Epistemology

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that deals with the nature of knowledge . It examines the conditions under which something counts as knowledge.

Key question: As well as focusing on critical thinking dispositions, what subject knowledge should the students understand?

4. Philosophy

Philosophy is the study of general truths about human life. Philosophers examine questions such as “What makes us happy?”, “How should we live our lives?”, and “Why does anything exist?”

Key question: Are there any opportunities for embracing philosophical enquiry into the project to develop critical thinking abilities ?

5. Curriculum

A curriculum is a set of courses designed to teach specific subjects. These courses may include mathematics , science, social studies, language arts, etc.

Key question: How will subject leaders ensure that the integrity of the curriculum is maintained?

6. Broad and Balanced Curriculum

Broad and balanced curricula are those that cover a wide range of topics. Some examples of these types of curriculums include AP Biology, AP Chemistry, AP English Language, AP Physics 1, AP Psychology , AP Spanish Literature, AP Statistics, AP US History, AP World History, IB Diploma Programme, IB Primary Years Program, IB Middle Years Program, IB Diploma Programme .

Key question: Are the teachers who have identified opportunities for a problem-based curriculum?

7. Successful Teaching Strategy

Successful teaching strategies involve effective communication techniques, clear objectives, and appropriate assessments. Teachers must ensure that their lessons are well-planned and organized. They must also provide opportunities for students to interact with one another and share information.

Key question: What pedagogical approaches and teaching strategies will you use?

8. Positive Solution Finding

Positive solution finding is a type of problem-solving where students actively seek out answers rather than passively accept what others tell them.

Key question: How will you ensure your problem-based curriculum is met with a positive mindset from students and teachers?

9. Real World Application

Real-world application refers to applying what students have learned in class to situations that occur in everyday life.

Key question: Within your local school community , are there any opportunities to apply knowledge and skills to real-life problems?

10. Creativity

Creativity is the ability to think of ideas that no one else has thought of yet. Creative thinking requires divergent thinking, which means thinking in different directions.

Key question: What teaching techniques will you use to enable children to generate their own ideas ?

11. Teamwork

Teamwork is the act of working together towards a common goal. Teams often consist of two or more people who work together to achieve a shared objective.

Key question: What opportunities are there to engage students in dialogic teaching methods where they talk their way through the problem?

12. Knowledge Transfer

Knowledge transfer occurs when teachers use their expertise to help students develop skills and abilities .

Key question: Can teachers be able to track the success of the project using improvement scores?

13. Active Learning

Active learning is any form of instruction that engages students in the learning process. Examples of active learning include group discussions, role-playing, debates, presentations, and simulations .

Key question: Will there be an emphasis on learning to learn and developing independent learning skills ?

14. Student Engagement

Student engagement is the degree to which students feel motivated to participate in academic activities.

Key question: Are there any tools available to monitor student engagement during the problem-based curriculum ?

Enhance Learner Outcomes Across Your School

Download an Overview of our Support and Resources

We'll send it over now.

Please fill in the details so we can send over the resources.

What type of school are you?

We'll get you the right resource

Is your school involved in any staff development projects?

Are your colleagues running any research projects or courses?

Do you have any immediate school priorities?

Please check the ones that apply.

Download your resource

Thanks for taking the time to complete this form, submit the form to get the tool.

Classroom Practice

Problem-Based Learning: What and How Do Students Learn?

- Published: September 2004

- Volume 16 , pages 235–266, ( 2004 )

Cite this article

- Cindy E. Hmelo-Silver 1

46k Accesses

2077 Citations

259 Altmetric

32 Mentions

Explore all metrics

Problem-based approaches to learning have a long history of advocating experience-based education. Psychological research and theory suggests that by having students learn through the experience of solving problems, they can learn both content and thinking strategies. Problem-based learning (PBL) is an instructional method in which students learn through facilitated problem solving. In PBL, student learning centers on a complex problem that does not have a single correct answer. Students work in collaborative groups to identify what they need to learn in order to solve a problem. They engage in self-directed learning (SDL) and then apply their new knowledge to the problem and reflect on what they learned and the effectiveness of the strategies employed. The teacher acts to facilitate the learning process rather than to provide knowledge. The goals of PBL include helping students develop 1) flexible knowledge, 2) effective problem-solving skills, 3) SDL skills, 4) effective collaboration skills, and 5) intrinsic motivation. This article discusses the nature of learning in PBL and examines the empirical evidence supporting it. There is considerable research on the first 3 goals of PBL but little on the last 2. Moreover, minimal research has been conducted outside medical and gifted education. Understanding how these goals are achieved with less skilled learners is an important part of a research agenda for PBL. The evidence suggests that PBL is an instructional approach that offers the potential to help students develop flexible understanding and lifelong learning skills.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Motivating students in competency-based education programmes: designing blended learning environments

Online learning in higher education: exploring advantages and disadvantages for engagement

The Effects of Problem-Based, Project-Based, and Case-Based Learning on Students’ Motivation: a Meta-Analysis

Abrandt Dahlgren, M., and Dahlgren, L. O. (2002). Portraits of PBL: Students' experiences of the characteristics of problem-based learning in physiotherapy, computer engineering, and psychology. Instr. Sci. 30: 111-127.

Google Scholar

Albanese, M. A., and Mitchell, S. (1993). Problem-based learning: A review of literature on its outcomes and implementation issues. Acad. Med. 68: 52-81.

Ames, C. (1992). Classrooms: Goals, structures, and student motivation. J. Educ. Psychol. 84: 261-271.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control , Freeman, New York.

Barron, B. J. S. (2002). Achieving coordination in collaborative problem-solving groups. J. Learn. Sci. 9: 403-437.

Barrows, H. S. (2000). Problem-Based Learning Applied to Medical Education , Southern Illinois University Press, Springfield.

Barrows, H., and Kelson, A. C. (1995). Problem-Based Learning in Secondary Education and the Problem-Based Learning Institute (Monograph 1), Problem-Based Learning Institute, Springfield, IL.

Barrows, H. S., and Tamblyn, R. (1980). Problem-Based Learning: An Approach to Medical Education , Springer, New York.

Bereiter, C., and Scardamalia, M. (1989). Intentional learning as a goal of instruction. In Resnick, L. B. (ed.), Knowing, Learning, and Instruction: Essays in Honor of Robert Glaser , Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, pp. 361-392.

Biggs, J. B. (1985). The role of metalearning in study processes. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 55: 185-212.

Blumberg, P., and Michael, J. A. (1992). Development of self-directed learning behaviors in a partially teacher-directed problem-based learning curriculum. Teach. Learn. Med. 4: 3-8.

Blumenfeld, P. C., Marx, R. W., Soloway, E., and Krajcik, J. S. (1996). Learning with peers: From small group cooperation to collaborative communities. Educ. Res. 25(8): 37-40.

Boud, D., and Feletti, G. (1991). The Challenge of Problem Based Learning , St. Martin's Press, New York.

Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., and Cocking, R. (2000). How People Learn , National Academy Press, Washington, DC.

Bransford, J. D., and McCarrell, N. S. (1977). A sketch of a cognitive approach to comprehension: Some thoughts about understanding what it means to comprehend. In Johnson-Laird, P. N., and Wason, P. C. (eds.), Thinking: Readings in Cognitive Science , Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, pp. 377-399.

Bransford, J. D., Vye, N., Kinzer, C., and Risko, R. (1990). Teaching thinking and content knowledge: Toward an integrated approach. In Jones, B. F., and Idol, L. (eds.), Dimensions of Thinking and Cognitive Instruction , Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, pp. 381-413.

Bridges, E. M. (1992). Problem-Based Learning for Administrators , ERIC Clearinghouse on Educational Management, Eugene, OR.

Brown, A. L. (1995). The advancement of learning. Educ. Res. 23(8): 4-12.

Chi, M. T. H., Bassok, M., Lewis, M. W., Reimann, P., and Glaser, R. (1989). Self-explanations: How students study and use examples in learning to solve problems. Cogn. Sci. 13: 145-182.

Chi, M. T. H., DeLeeuw, N., Chiu, M., and LaVancher, C. (1994). Eliciting self-explanations improves understanding. Cogn. Sci. 18: 439-477.

Chi, M. T. H., Feltovich, P., and Glaser, R. (1981). Categorization and representation of physics problems by experts and novices. Cogn. Sci. 5: 121-152.

Cognition and Technology Group at Vanderbilt (1997). The Jasper Project: Lessons in Curriculum, Instruction, Assessment, and Professional Development , Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ.

Cohen, E. G. (1994). Restructuring the classroom: Conditions for productive small groups. Rev. Educ. Res. 64: 1-35.

Collins, A., Brown, J. S., and Newman, S. E. (1989). Cognitive apprenticeship: Teaching the crafts of reading, writing, and mathematics. In Resnick, L. B. (ed.), Knowing, Learning, and Instruction: Essays in Honor of Robert Glaser , Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, pp. 453-494.

DeGrave, W. S., Boshuizen, H. P. A., and Schmidt, H. G. (1996). Problem-based learning: Cognitive and metacognitive processes during problem analysis. Instr. Sci. 24: 321-341.

Derry, S. J., Lee, J., Kim, J.-B., Seymour, J., and Steinkuehler, C. A. (2001, April). From ambitious vision to partially satisfying reality: Community and collaboration in teacher education . Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Seattle, WA.

Derry, S. J., Levin, J. R., Osana, H. P., Jones, M. S., and Peterson, M. (2000). Fostering students' statistical and scientific thinking: Lessons learned from an innovative college course. Am. Educ. Res. J. 37: 747-773.