Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

What is an Argumentative Essay? How to Write It (With Examples)

We define an argumentative essay as a type of essay that presents arguments about both sides of an issue. The purpose is to convince the reader to accept a particular viewpoint or action. In an argumentative essay, the writer takes a stance on a controversial or debatable topic and supports their position with evidence, reasoning, and examples. The essay should also address counterarguments, demonstrating a thorough understanding of the topic.

Table of Contents

- What is an argumentative essay?

- Argumentative essay structure

- Argumentative essay outline

- Types of argument claims

How to write an argumentative essay?

- Argumentative essay writing tips

- Good argumentative essay example

How to write a good thesis

- How to Write an Argumentative Essay with Paperpal?

Frequently Asked Questions

What is an argumentative essay.

An argumentative essay is a type of writing that presents a coherent and logical analysis of a specific topic. 1 The goal is to convince the reader to accept the writer’s point of view or opinion on a particular issue. Here are the key elements of an argumentative essay:

- Thesis Statement : The central claim or argument that the essay aims to prove.

- Introduction : Provides background information and introduces the thesis statement.

- Body Paragraphs : Each paragraph addresses a specific aspect of the argument, presents evidence, and may include counter arguments.

Articulate your thesis statement better with Paperpal. Start writing now!

- Evidence : Supports the main argument with relevant facts, examples, statistics, or expert opinions.

- Counterarguments : Anticipates and addresses opposing viewpoints to strengthen the overall argument.

- Conclusion : Summarizes the main points, reinforces the thesis, and may suggest implications or actions.

Argumentative essay structure

Aristotelian, Rogerian, and Toulmin are three distinct approaches to argumentative essay structures, each with its principles and methods. 2 The choice depends on the purpose and nature of the topic. Here’s an overview of each type of argumentative essay format.

Have a looming deadline for your argumentative essay? Write 2x faster with Paperpal – Start now!

Argumentative essay outline

An argumentative essay presents a specific claim or argument and supports it with evidence and reasoning. Here’s an outline for an argumentative essay, along with examples for each section: 3

1. Introduction :

- Hook : Start with a compelling statement, question, or anecdote to grab the reader’s attention.

Example: “Did you know that plastic pollution is threatening marine life at an alarming rate?”

- Background information : Provide brief context about the issue.

Example: “Plastic pollution has become a global environmental concern, with millions of tons of plastic waste entering our oceans yearly.”

- Thesis statement : Clearly state your main argument or position.

Example: “We must take immediate action to reduce plastic usage and implement more sustainable alternatives to protect our marine ecosystem.”

2. Body Paragraphs :

- Topic sentence : Introduce the main idea of each paragraph.

Example: “The first step towards addressing the plastic pollution crisis is reducing single-use plastic consumption.”

- Evidence/Support : Provide evidence, facts, statistics, or examples that support your argument.

Example: “Research shows that plastic straws alone contribute to millions of tons of plastic waste annually, and many marine animals suffer from ingestion or entanglement.”

- Counterargument/Refutation : Acknowledge and refute opposing viewpoints.

Example: “Some argue that banning plastic straws is inconvenient for consumers, but the long-term environmental benefits far outweigh the temporary inconvenience.”

- Transition : Connect each paragraph to the next.

Example: “Having addressed the issue of single-use plastics, the focus must now shift to promoting sustainable alternatives.”

3. Counterargument Paragraph :

- Acknowledgement of opposing views : Recognize alternative perspectives on the issue.

Example: “While some may argue that individual actions cannot significantly impact global plastic pollution, the cumulative effect of collective efforts must be considered.”

- Counterargument and rebuttal : Present and refute the main counterargument.

Example: “However, individual actions, when multiplied across millions of people, can substantially reduce plastic waste. Small changes in behavior, such as using reusable bags and containers, can have a significant positive impact.”

4. Conclusion :

- Restatement of thesis : Summarize your main argument.

Example: “In conclusion, adopting sustainable practices and reducing single-use plastic is crucial for preserving our oceans and marine life.”

- Call to action : Encourage the reader to take specific steps or consider the argument’s implications.

Example: “It is our responsibility to make environmentally conscious choices and advocate for policies that prioritize the health of our planet. By collectively embracing sustainable alternatives, we can contribute to a cleaner and healthier future.”

Types of argument claims

A claim is a statement or proposition a writer puts forward with evidence to persuade the reader. 4 Here are some common types of argument claims, along with examples:

- Fact Claims : These claims assert that something is true or false and can often be verified through evidence. Example: “Water boils at 100°C at sea level.”

- Value Claims : Value claims express judgments about the worth or morality of something, often based on personal beliefs or societal values. Example: “Organic farming is more ethical than conventional farming.”

- Policy Claims : Policy claims propose a course of action or argue for a specific policy, law, or regulation change. Example: “Schools should adopt a year-round education system to improve student learning outcomes.”

- Cause and Effect Claims : These claims argue that one event or condition leads to another, establishing a cause-and-effect relationship. Example: “Excessive use of social media is a leading cause of increased feelings of loneliness among young adults.”

- Definition Claims : Definition claims assert the meaning or classification of a concept or term. Example: “Artificial intelligence can be defined as machines exhibiting human-like cognitive functions.”

- Comparative Claims : Comparative claims assert that one thing is better or worse than another in certain respects. Example: “Online education is more cost-effective than traditional classroom learning.”

- Evaluation Claims : Evaluation claims assess the quality, significance, or effectiveness of something based on specific criteria. Example: “The new healthcare policy is more effective in providing affordable healthcare to all citizens.”

Understanding these argument claims can help writers construct more persuasive and well-supported arguments tailored to the specific nature of the claim.

If you’re wondering how to start an argumentative essay, here’s a step-by-step guide to help you with the argumentative essay format and writing process.

- Choose a Topic: Select a topic that you are passionate about or interested in. Ensure that the topic is debatable and has two or more sides.

- Define Your Position: Clearly state your stance on the issue. Consider opposing viewpoints and be ready to counter them.

- Conduct Research: Gather relevant information from credible sources, such as books, articles, and academic journals. Take notes on key points and supporting evidence.

- Create a Thesis Statement: Develop a concise and clear thesis statement that outlines your main argument. Convey your position on the issue and provide a roadmap for the essay.

- Outline Your Argumentative Essay: Organize your ideas logically by creating an outline. Include an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion. Each body paragraph should focus on a single point that supports your thesis.

- Write the Introduction: Start with a hook to grab the reader’s attention (a quote, a question, a surprising fact). Provide background information on the topic. Present your thesis statement at the end of the introduction.

- Develop Body Paragraphs: Begin each paragraph with a clear topic sentence that relates to the thesis. Support your points with evidence and examples. Address counterarguments and refute them to strengthen your position. Ensure smooth transitions between paragraphs.

- Address Counterarguments: Acknowledge and respond to opposing viewpoints. Anticipate objections and provide evidence to counter them.

- Write the Conclusion: Summarize the main points of your argumentative essay. Reinforce the significance of your argument. End with a call to action, a prediction, or a thought-provoking statement.

- Revise, Edit, and Share: Review your essay for clarity, coherence, and consistency. Check for grammatical and spelling errors. Share your essay with peers, friends, or instructors for constructive feedback.

- Finalize Your Argumentative Essay: Make final edits based on feedback received. Ensure that your essay follows the required formatting and citation style.

Struggling to start your argumentative essay? Paperpal can help – try now!

Argumentative essay writing tips

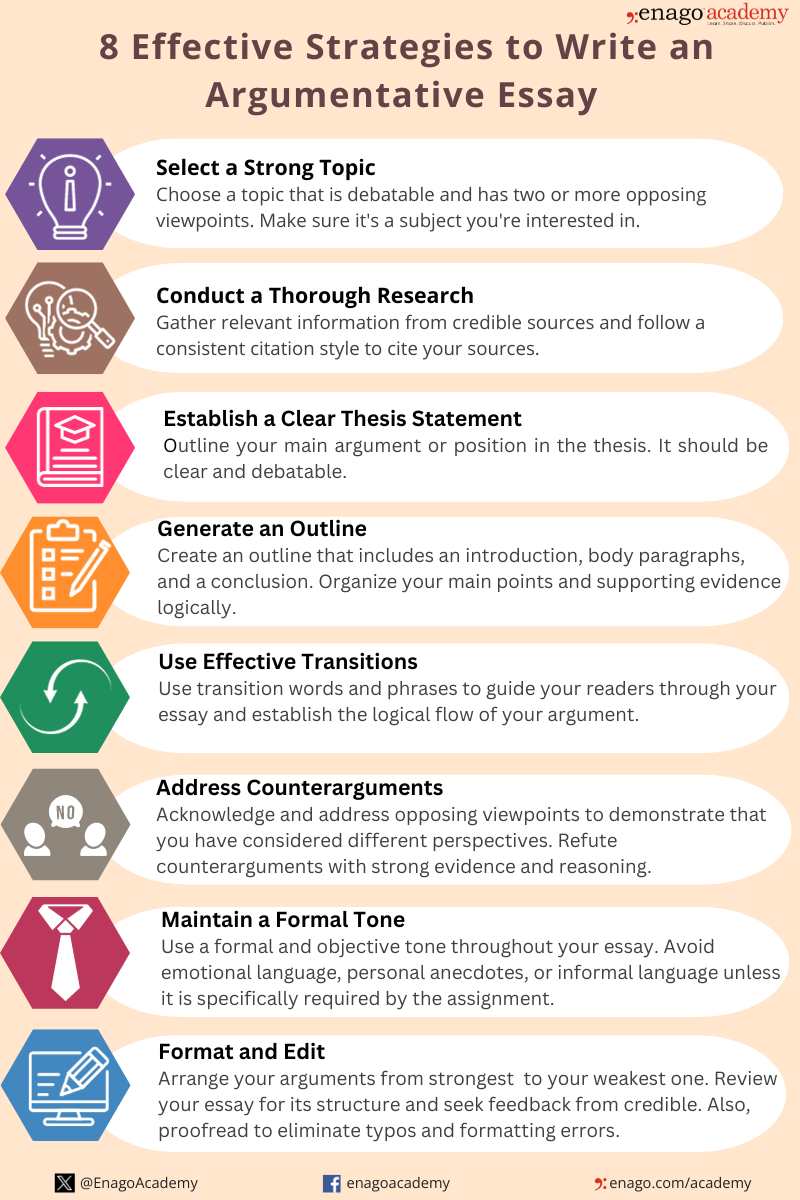

Here are eight strategies to craft a compelling argumentative essay:

- Choose a Clear and Controversial Topic : Select a topic that sparks debate and has opposing viewpoints. A clear and controversial issue provides a solid foundation for a strong argument.

- Conduct Thorough Research : Gather relevant information from reputable sources to support your argument. Use a variety of sources, such as academic journals, books, reputable websites, and expert opinions, to strengthen your position.

- Create a Strong Thesis Statement : Clearly articulate your main argument in a concise thesis statement. Your thesis should convey your stance on the issue and provide a roadmap for the reader to follow your argument.

- Develop a Logical Structure : Organize your essay with a clear introduction, body paragraphs, and conclusion. Each paragraph should focus on a specific point of evidence that contributes to your overall argument. Ensure a logical flow from one point to the next.

- Provide Strong Evidence : Support your claims with solid evidence. Use facts, statistics, examples, and expert opinions to support your arguments. Be sure to cite your sources appropriately to maintain credibility.

- Address Counterarguments : Acknowledge opposing viewpoints and counterarguments. Addressing and refuting alternative perspectives strengthens your essay and demonstrates a thorough understanding of the issue. Be mindful of maintaining a respectful tone even when discussing opposing views.

- Use Persuasive Language : Employ persuasive language to make your points effectively. Avoid emotional appeals without supporting evidence and strive for a respectful and professional tone.

- Craft a Compelling Conclusion : Summarize your main points, restate your thesis, and leave a lasting impression in your conclusion. Encourage readers to consider the implications of your argument and potentially take action.

Good argumentative essay example

Let’s consider a sample of argumentative essay on how social media enhances connectivity:

In the digital age, social media has emerged as a powerful tool that transcends geographical boundaries, connecting individuals from diverse backgrounds and providing a platform for an array of voices to be heard. While critics argue that social media fosters division and amplifies negativity, it is essential to recognize the positive aspects of this digital revolution and how it enhances connectivity by providing a platform for diverse voices to flourish. One of the primary benefits of social media is its ability to facilitate instant communication and connection across the globe. Platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram break down geographical barriers, enabling people to establish and maintain relationships regardless of physical location and fostering a sense of global community. Furthermore, social media has transformed how people stay connected with friends and family. Whether separated by miles or time zones, social media ensures that relationships remain dynamic and relevant, contributing to a more interconnected world. Moreover, social media has played a pivotal role in giving voice to social justice movements and marginalized communities. Movements such as #BlackLivesMatter, #MeToo, and #ClimateStrike have gained momentum through social media, allowing individuals to share their stories and advocate for change on a global scale. This digital activism can shape public opinion and hold institutions accountable. Social media platforms provide a dynamic space for open dialogue and discourse. Users can engage in discussions, share information, and challenge each other’s perspectives, fostering a culture of critical thinking. This open exchange of ideas contributes to a more informed and enlightened society where individuals can broaden their horizons and develop a nuanced understanding of complex issues. While criticisms of social media abound, it is crucial to recognize its positive impact on connectivity and the amplification of diverse voices. Social media transcends physical and cultural barriers, connecting people across the globe and providing a platform for marginalized voices to be heard. By fostering open dialogue and facilitating the exchange of ideas, social media contributes to a more interconnected and empowered society. Embracing the positive aspects of social media allows us to harness its potential for positive change and collective growth.

- Clearly Define Your Thesis Statement: Your thesis statement is the core of your argumentative essay. Clearly articulate your main argument or position on the issue. Avoid vague or general statements.

- Provide Strong Supporting Evidence: Back up your thesis with solid evidence from reliable sources and examples. This can include facts, statistics, expert opinions, anecdotes, or real-life examples. Make sure your evidence is relevant to your argument, as it impacts the overall persuasiveness of your thesis.

- Anticipate Counterarguments and Address Them: Acknowledge and address opposing viewpoints to strengthen credibility. This also shows that you engage critically with the topic rather than presenting a one-sided argument.

How to Write an Argumentative Essay with Paperpal?

Writing a winning argumentative essay not only showcases your ability to critically analyze a topic but also demonstrates your skill in persuasively presenting your stance backed by evidence. Achieving this level of writing excellence can be time-consuming. This is where Paperpal, your AI academic writing assistant, steps in to revolutionize the way you approach argumentative essays. Here’s a step-by-step guide on how to use Paperpal to write your essay:

- Sign Up or Log In: Begin by creating an account or logging into paperpal.com .

- Navigate to Paperpal Copilot: Once logged in, proceed to the Templates section from the side navigation bar.

- Generate an essay outline: Under Templates, click on the ‘Outline’ tab and choose ‘Essay’ from the options and provide your topic to generate an outline.

- Develop your essay: Use this structured outline as a guide to flesh out your essay. If you encounter any roadblocks, click on Brainstorm and get subject-specific assistance, ensuring you stay on track.

- Refine your writing: To elevate the academic tone of your essay, select a paragraph and use the ‘Make Academic’ feature under the ‘Rewrite’ tab, ensuring your argumentative essay resonates with an academic audience.

- Final Touches: Make your argumentative essay submission ready with Paperpal’s language, grammar, consistency and plagiarism checks, and improve your chances of acceptance.

Paperpal not only simplifies the essay writing process but also ensures your argumentative essay is persuasive, well-structured, and academically rigorous. Sign up today and transform how you write argumentative essays.

The length of an argumentative essay can vary, but it typically falls within the range of 1,000 to 2,500 words. However, the specific requirements may depend on the guidelines provided.

You might write an argumentative essay when: 1. You want to convince others of the validity of your position. 2. There is a controversial or debatable issue that requires discussion. 3. You need to present evidence and logical reasoning to support your claims. 4. You want to explore and critically analyze different perspectives on a topic.

Argumentative Essay: Purpose : An argumentative essay aims to persuade the reader to accept or agree with a specific point of view or argument. Structure : It follows a clear structure with an introduction, thesis statement, body paragraphs presenting arguments and evidence, counterarguments and refutations, and a conclusion. Tone : The tone is formal and relies on logical reasoning, evidence, and critical analysis. Narrative/Descriptive Essay: Purpose : These aim to tell a story or describe an experience, while a descriptive essay focuses on creating a vivid picture of a person, place, or thing. Structure : They may have a more flexible structure. They often include an engaging introduction, a well-developed body that builds the story or description, and a conclusion. Tone : The tone is more personal and expressive to evoke emotions or provide sensory details.

- Gladd, J. (2020). Tips for Writing Academic Persuasive Essays. Write What Matters .

- Nimehchisalem, V. (2018). Pyramid of argumentation: Towards an integrated model for teaching and assessing ESL writing. Language & Communication , 5 (2), 185-200.

- Press, B. (2022). Argumentative Essays: A Step-by-Step Guide . Broadview Press.

- Rieke, R. D., Sillars, M. O., & Peterson, T. R. (2005). Argumentation and critical decision making . Pearson/Allyn & Bacon.

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- Empirical Research: A Comprehensive Guide for Academics

- How to Write a Scientific Paper in 10 Steps

- What is a Literature Review? How to Write It (with Examples)

- Life Sciences Papers: 9 Tips for Authors Writing in Biological Sciences

Make Your Research Paper Error-Free with Paperpal’s Online Spell Checker

The do’s & don’ts of using generative ai tools ethically in academia, you may also like, how to write the first draft of a..., mla works cited page: format, template & examples, how to ace grant writing for research funding..., powerful academic phrases to improve your essay writing , how to write a high-quality conference paper, how paperpal is enhancing academic productivity and accelerating..., academic editing: how to self-edit academic text with..., 4 ways paperpal encourages responsible writing with ai, what are scholarly sources and where can you..., how to write a hypothesis types and examples .

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

How to Write an Argumentative Essay

4-minute read

- 30th April 2022

An argumentative essay is a structured, compelling piece of writing where an author clearly defines their stance on a specific topic. This is a very popular style of writing assigned to students at schools, colleges, and universities. Learn the steps to researching, structuring, and writing an effective argumentative essay below.

Requirements of an Argumentative Essay

To effectively achieve its purpose, an argumentative essay must contain:

● A concise thesis statement that introduces readers to the central argument of the essay

● A clear, logical, argument that engages readers

● Ample research and evidence that supports your argument

Approaches to Use in Your Argumentative Essay

1. classical.

● Clearly present the central argument.

● Outline your opinion.

● Provide enough evidence to support your theory.

2. Toulmin

● State your claim.

● Supply the evidence for your stance.

● Explain how these findings support the argument.

● Include and discuss any limitations of your belief.

3. Rogerian

● Explain the opposing stance of your argument.

● Discuss the problems with adopting this viewpoint.

● Offer your position on the matter.

● Provide reasons for why yours is the more beneficial stance.

● Include a potential compromise for the topic at hand.

Tips for Writing a Well-Written Argumentative Essay

● Introduce your topic in a bold, direct, and engaging manner to captivate your readers and encourage them to keep reading.

● Provide sufficient evidence to justify your argument and convince readers to adopt this point of view.

● Consider, include, and fairly present all sides of the topic.

● Structure your argument in a clear, logical manner that helps your readers to understand your thought process.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

● Discuss any counterarguments that might be posed.

● Use persuasive writing that’s appropriate for your target audience and motivates them to agree with you.

Steps to Write an Argumentative Essay

Follow these basic steps to write a powerful and meaningful argumentative essay :

Step 1: Choose a topic that you’re passionate about

If you’ve already been given a topic to write about, pick a stance that resonates deeply with you. This will shine through in your writing, make the research process easier, and positively influence the outcome of your argument.

Step 2: Conduct ample research to prove the validity of your argument

To write an emotive argumentative essay , finding enough research to support your theory is a must. You’ll need solid evidence to convince readers to agree with your take on the matter. You’ll also need to logically organize the research so that it naturally convinces readers of your viewpoint and leaves no room for questioning.

Step 3: Follow a simple, easy-to-follow structure and compile your essay

A good structure to ensure a well-written and effective argumentative essay includes:

Introduction

● Introduce your topic.

● Offer background information on the claim.

● Discuss the evidence you’ll present to support your argument.

● State your thesis statement, a one-to-two sentence summary of your claim.

● This is the section where you’ll develop and expand on your argument.

● It should be split into three or four coherent paragraphs, with each one presenting its own idea.

● Start each paragraph with a topic sentence that indicates why readers should adopt your belief or stance.

● Include your research, statistics, citations, and other supporting evidence.

● Discuss opposing viewpoints and why they’re invalid.

● This part typically consists of one paragraph.

● Summarize your research and the findings that were presented.

● Emphasize your initial thesis statement.

● Persuade readers to agree with your stance.

We certainly hope that you feel inspired to use these tips when writing your next argumentative essay . And, if you’re currently elbow-deep in writing one, consider submitting a free sample to us once it’s completed. Our expert team of editors can help ensure that it’s concise, error-free, and effective!

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

9-minute read

How to Use Infographics to Boost Your Presentation

Is your content getting noticed? Capturing and maintaining an audience’s attention is a challenge when...

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

How to Ace Slack Messaging for Contractors and Freelancers

Effective professional communication is an important skill for contractors and freelancers navigating remote work environments....

3-minute read

How to Insert a Text Box in a Google Doc

Google Docs is a powerful collaborative tool, and mastering its features can significantly enhance your...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

The Beginner's Blueprint for Writing an Effective Argumentative Essay

Are you ready to learn how to write an argumentative essay that packs a punch? Buckle up, because we're about to embark on a journey that will transform you into a master of persuasive writing! Whether you're a student, writer, or just someone who loves a good debate, mastering the art of crafting a compelling argumentative essay is a skill that will serve you well.

In this article, we'll walk you through the essential steps to writing an argumentative essay that effectively supports your stance with solid evidence and convincing reasoning. From understanding the basics to structuring your essay for maximum impact, we've got you covered. So, let's dive in and discover how to write an argumentative essay that will leave your readers convinced and impressed!

Understanding the Basics of an Argumentative Essay

Before diving into the nitty-gritty of crafting an argumentative essay, it's crucial to grasp the fundamentals. An argumentative essay is all about presenting a well-researched and logical argument to persuade your readers to see things from your perspective. It's not just about stating your opinion; it's about backing it up with solid evidence and reasoning.

The Building Blocks of an Argumentative Essay

- Introduction: This is where you set the stage for your argument. Start with a hook to grab your readers' attention, provide some background information, and clearly state your thesis .

- Body Paragraphs: This is the meat of your essay, where you present your arguments and evidence. Each paragraph should focus on one main point and provide supporting evidence.

- Conclusion: Wrap up your essay by restating your thesis and summarizing your main points. Leave your readers with something to think about.

Types of Argumentative Essays

The writing process.

- Brainstorm and research your topic

- Prepare an outline

- Draft your essay

- Revise and refine

- Proofread and edit

Remember, an argumentative essay is all about presenting a confident and assertive stance while maintaining a logical and organized structure. With these basics in mind, you're well on your way to writing a compelling argumentative essay!

Choosing a Strong Topic

Alright, let's dive into the exciting world of choosing a strong topic for your argumentative essay! The key is to find a subject that sparks your interest and gets your audience fired up.

What Makes a Topic Arguable?

To ensure your topic is arguable, ask yourself these questions:

- Is it debatable? Can people have different opinions on the subject?

- Is it relevant to your audience? Will they find it interesting and engaging?

- Is it not too broad or too narrow? You want a topic that's just right!

Techniques for Generating Topic Ideas

Narrowing down your topic.

Once you have a list of potential topics, it's time to narrow it down:

- Consider your goals and purpose for the essay. What do you want to achieve?

- Ensure there is sufficient evidence available to support your argument.

- Test the topic by putting it in a general argument format, such as "Is...effective?" or "...should be allowed for..."

Remember, a strong argumentative essay topic should be debatable, relevant to your audience, and not too broad or too narrow. By following these guidelines and techniques, you'll be well on your way to choosing a topic that will make your essay shine!

Structuring Your Essay Effectively

Alright, let's talk about how to structure your argumentative essay like a pro! A well-organized essay is like a roadmap that guides your readers through your argument, making it easy for them to follow along and see things from your perspective.

The Building Blocks of a Winning Structure

Crafting a compelling argument.

- Present your perspective: Explain your stance on the topic clearly and concisely.

- Address the opposition: Acknowledge and refute counterarguments with solid evidence.

- Provide evidence: Back up your claims with facts, statistics, and expert opinions.

- Find common ground: Consider both sides of the issue and propose a middle ground, if possible.

- Conclude with conviction: Reinforce your thesis and summarize your main points, leaving a lasting impression.

Logical Flow and Organization

To ensure your essay is easy to follow, pay attention to:

- Clear transitions between the introduction, body, and conclusion

- Body paragraphs that provide evidential support and explain how it connects to your thesis

- Consideration and explanation of differing viewpoints

- A conclusion that ties everything together and reinforces your argument

By structuring your essay effectively, you'll create a compelling and persuasive argument that leaves your readers convinced and impressed. So, go forth and organize your thoughts like a master debater!

Gathering and Evaluating Evidence

Alright, let's talk about gathering and evaluating evidence like a pro! This is where the real fun begins, as you dive into the world of research and uncover the juicy bits that will make your argumentative essay shine.

The Evidence Hunt

Using evidence effectively.

- Introduce the evidence and explain its significance.

- Show how the evidence supports your argument.

- Use quotations, paraphrasing, and summary to present the evidence.

- Always cite your sources properly.

Evaluating Evidence for Credibility

When assessing the credibility, accuracy, and reliability of your evidence, consider:

- The source: Is it primary or secondary? Is it reputable?

- Comparison with other sources: Does it align with or contradict other findings?

- Currency: Is the information up-to-date and relevant?

- Relevance: Does it directly support your claim and argument?

Evidence for Different Essay Types

- Literary Analysis Essays: Use quotes from the work itself or literary criticism.

- Research-Based Papers: Gather information from reliable sources, such as academic databases, libraries, and trusted websites.

- Document-Based Papers: Develop an argument based on provided documents, synthesizing material from at least three sources.

Putting It All Together

- Provide logical and persuasive evidence.

- Ensure your proof is appropriately documented.

- Consider your audience and present clear and convincing evidence.

- Explain the significance of each piece of evidence.

- Build evidence into your text strategically to prove your points.

Remember, well-researched, accurate, detailed, and current information is key to supporting your thesis statement. By gathering and evaluating evidence like a pro, you'll be well on your way to crafting an argumentative essay that packs a punch!

Crafting a Persuasive Thesis Statement

Alright, let's dive into the art of crafting a persuasive thesis statement that will make your argumentative essay shine like a beacon of brilliance!

The Power of a Strong Thesis Statement

A thesis statement is like the heart of your essay - it pumps life into your argument and keeps everything flowing smoothly. Here's what makes a thesis statement truly persuasive:

- It takes a stand: Your thesis should make a clear, debatable claim that people could reasonably have differing opinions on.

- It's specific: Narrow down your focus to make your argument more effective and easier to support with evidence.

- It's supportable: Make sure you can back up your claim with solid facts and reasoning.

- It's not just an announcement: Your thesis should do more than just state your topic - it should make an argument about it.

Crafting Your Persuasive Thesis: A Step-by-Step Guide

Examples of persuasive thesis statements.

- "The surge in plastic products during the 21st century has had a notable impact on climate change due to increased greenhouse gas emissions at every stage of its lifecycle, from production to disposal."

- "While social media provides rapid access to information, it has inadvertently become a conduit for misinformation, causing significant societal implications that call for more robust regulations."

- "While zoos have been popular attractions for centuries, they often cause more harm than good to the animals, making their closure imperative for animal welfare."

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Being too vague or broad

- Stating a fact instead of an argument

- Lacking focus or clarity

- Writing the thesis statement last

Remember, a persuasive thesis statement is the foundation of your argumentative essay. By crafting a clear, specific, and debatable claim that directly addresses your prompt, you'll set yourself up for success in convincing your readers to see things from your perspective. So go forth and argue with confidence!

Revising and Editing Your Essay

Alright, let's dive into the nitty-gritty of revising and editing your argumentative essay like a pro! This is where the magic happens, as you transform your rough draft into a polished masterpiece that will knock your readers' socks off.

The Revision Process: Making Your Essay Shine

Revising your essay involves taking a step back and looking at the big picture. It's all about making changes to the content, organization, and source material to ensure your argument is clear, well-supported, and logically structured.

- Check the clarity and support of your argument

- Evaluate the organization and logical flow of your essay

- Ensure proper integration and citation of sources

The Editing Process: Polishing Your Prose

Once you've revised your essay, it's time to put on your editing hat and focus on the sentence-level details. This is where you'll hunt down those pesky grammatical, punctuation, and typographical errors that can detract from your brilliant argument.

Tips and Tricks for Effective Revision and Editing

- Allow time between writing and revising for a fresh perspective

- Read your essay aloud to identify awkward phrasing or unclear points

- Get feedback from others and consider their suggestions

- Use the ARMS strategy for revision: Add, Remove, Move, and Substitute

- After revising, write a clean draft for publication, taking all revisions into account

Remember, the revision and editing process is crucial to transforming your argumentative essay from good to amazing. By carefully evaluating your essay and making necessary changes, you'll ensure that your argument is clear, well-supported, and persuasive.

So, roll up your sleeves, grab your red pen, and get ready to revise and edit your way to argumentative essay success!

Writing an effective argumentative essay is a skill that can be mastered with practice and dedication. By understanding the basics, choosing a strong topic, structuring your essay effectively, gathering and evaluating evidence, crafting a persuasive thesis statement, and revising and editing your work, you'll be well-equipped to create compelling arguments that leave a lasting impact on your readers.

As you embark on your argumentative essay writing journey, remember to approach each step with enthusiasm and an open mind. Embrace the power of persuasion, and let your unique voice shine through your writing. With these tools and techniques at your disposal, you're ready to tackle any argumentative essay that comes your way and make your mark in the world of persuasive writing.

What is an effective way to begin an argumentative essay?

To effectively initiate an argumentative essay, start with an engaging hook or a sentence that grabs attention. Provide a brief summary of the texts involved, clearly state your claim by restating the essay prompt, and include a topic sentence that reaffirms your claim and your reasoning.

How should I structure the opening of my argumentative essay?

The opening of an argumentative essay should establish the context by offering a general overview of the topic. The author should then highlight the significance of the topic or why it should matter to the readers. Concluding the introduction, the thesis statement should be presented, clearly outlining the main argument of the essay.

What is the initial step in crafting an argumentative essay?

The first step in writing an argumentative essay is selecting a topic and formulating a strong thesis statement. Your thesis should state your claim, your position on the claim, and outline the primary points that will bolster your stance within the context of the chosen topic. This statement will guide the development of the essay's body paragraphs.

Sign up for more like this.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

9.3: The Argumentative Essay

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 58378

- Lumen Learning

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Learning Objectives

- Examine types of argumentative essays

Argumentative Essays

You may have heard it said that all writing is an argument of some kind. Even if you’re writing an informative essay, you still have the job of trying to convince your audience that the information is important. However, there are times you’ll be asked to write an essay that is specifically an argumentative piece.

An argumentative essay is one that makes a clear assertion or argument about some topic or issue. When you’re writing an argumentative essay, it’s important to remember that an academic argument is quite different from a regular, emotional argument. Note that sometimes students forget the academic aspect of an argumentative essay and write essays that are much too emotional for an academic audience. It’s important for you to choose a topic you feel passionately about (if you’re allowed to pick your topic), but you have to be sure you aren’t too emotionally attached to a topic. In an academic argument, you’ll have a lot more constraints you have to consider, and you’ll focus much more on logic and reasoning than emotions.

Argumentative essays are quite common in academic writing and are often an important part of writing in all disciplines. You may be asked to take a stand on a social issue in your introduction to writing course, but you could also be asked to take a stand on an issue related to health care in your nursing courses or make a case for solving a local environmental problem in your biology class. And, since argument is such a common essay assignment, it’s important to be aware of some basic elements of a good argumentative essay.

When your professor asks you to write an argumentative essay, you’ll often be given something specific to write about. For example, you may be asked to take a stand on an issue you have been discussing in class. Perhaps, in your education class, you would be asked to write about standardized testing in public schools. Or, in your literature class, you might be asked to argue the effects of protest literature on public policy in the United States.

However, there are times when you’ll be given a choice of topics. You might even be asked to write an argumentative essay on any topic related to your field of study or a topic you feel that is important personally.

Whatever the case, having some knowledge of some basic argumentative techniques or strategies will be helpful as you write. Below are some common types of arguments.

Causal Arguments

- In this type of argument, you argue that something has caused something else. For example, you might explore the causes of the decline of large mammals in the world’s ocean and make a case for your cause.

Evaluation Arguments

- In this type of argument, you make an argumentative evaluation of something as “good” or “bad,” but you need to establish the criteria for “good” or “bad.” For example, you might evaluate a children’s book for your education class, but you would need to establish clear criteria for your evaluation for your audience.

Proposal Arguments

- In this type of argument, you must propose a solution to a problem. First, you must establish a clear problem and then propose a specific solution to that problem. For example, you might argue for a proposal that would increase retention rates at your college.

Narrative Arguments

- In this type of argument, you make your case by telling a story with a clear point related to your argument. For example, you might write a narrative about your experiences with standardized testing in order to make a case for reform.

Rebuttal Arguments

- In a rebuttal argument, you build your case around refuting an idea or ideas that have come before. In other words, your starting point is to challenge the ideas of the past.

Definition Arguments

- In this type of argument, you use a definition as the starting point for making your case. For example, in a definition argument, you might argue that NCAA basketball players should be defined as professional players and, therefore, should be paid.

https://assessments.lumenlearning.co...essments/20277

Essay Examples

- Click here to read an argumentative essay on the consequences of fast fashion . Read it and look at the comments to recognize strategies and techniques the author uses to convey her ideas.

- In this example, you’ll see a sample argumentative paper from a psychology class submitted in APA format. Key parts of the argumentative structure have been noted for you in the sample.

Link to Learning

For more examples of types of argumentative essays, visit the Argumentative Purposes section of the Excelsior OWL .

Contributors and Attributions

- Argumentative Essay. Provided by : Excelsior OWL. Located at : https://owl.excelsior.edu/rhetorical-styles/argumentative-essay/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Image of a man with a heart and a brain. Authored by : Mohamed Hassan. Provided by : Pixabay. Located at : pixabay.com/illustrations/decision-brain-heart-mind-4083469/. License : Other . License Terms : pixabay.com/service/terms/#license

8 Effective Strategies to Write Argumentative Essays

In a bustling university town, there lived a student named Alex. Popular for creativity and wit, one challenge seemed insurmountable for Alex– the dreaded argumentative essay!

One gloomy afternoon, as the rain tapped against the window pane, Alex sat at his cluttered desk, staring at a blank document on the computer screen. The assignment loomed large: a 350-600-word argumentative essay on a topic of their choice . With a sigh, he decided to seek help of mentor, Professor Mitchell, who was known for his passion for writing.

Entering Professor Mitchell’s office was like stepping into a treasure of knowledge. Bookshelves lined every wall, faint aroma of old manuscripts in the air and sticky notes over the wall. Alex took a deep breath and knocked on his door.

“Ah, Alex,” Professor Mitchell greeted with a warm smile. “What brings you here today?”

Alex confessed his struggles with the argumentative essay. After hearing his concerns, Professor Mitchell said, “Ah, the argumentative essay! Don’t worry, Let’s take a look at it together.” As he guided Alex to the corner shelf, Alex asked,

Table of Contents

“What is an Argumentative Essay?”

The professor replied, “An argumentative essay is a type of academic writing that presents a clear argument or a firm position on a contentious issue. Unlike other forms of essays, such as descriptive or narrative essays, these essays require you to take a stance, present evidence, and convince your audience of the validity of your viewpoint with supporting evidence. A well-crafted argumentative essay relies on concrete facts and supporting evidence rather than merely expressing the author’s personal opinions . Furthermore, these essays demand comprehensive research on the chosen topic and typically follows a structured format consisting of three primary sections: an introductory paragraph, three body paragraphs, and a concluding paragraph.”

He continued, “Argumentative essays are written in a wide range of subject areas, reflecting their applicability across disciplines. They are written in different subject areas like literature and philosophy, history, science and technology, political science, psychology, economics and so on.

Alex asked,

“When is an Argumentative Essay Written?”

The professor answered, “Argumentative essays are often assigned in academic settings, but they can also be written for various other purposes, such as editorials, opinion pieces, or blog posts. Some situations to write argumentative essays include:

1. Academic assignments

In school or college, teachers may assign argumentative essays as part of coursework. It help students to develop critical thinking and persuasive writing skills .

2. Debates and discussions

Argumentative essays can serve as the basis for debates or discussions in academic or competitive settings. Moreover, they provide a structured way to present and defend your viewpoint.

3. Opinion pieces

Newspapers, magazines, and online publications often feature opinion pieces that present an argument on a current issue or topic to influence public opinion.

4. Policy proposals

In government and policy-related fields, argumentative essays are used to propose and defend specific policy changes or solutions to societal problems.

5. Persuasive speeches

Before delivering a persuasive speech, it’s common to prepare an argumentative essay as a foundation for your presentation.

Regardless of the context, an argumentative essay should present a clear thesis statement , provide evidence and reasoning to support your position, address counterarguments, and conclude with a compelling summary of your main points. The goal is to persuade readers or listeners to accept your viewpoint or at least consider it seriously.”

Handing over a book, the professor continued, “Take a look on the elements or structure of an argumentative essay.”

Elements of an Argumentative Essay

An argumentative essay comprises five essential components:

Claim in argumentative writing is the central argument or viewpoint that the writer aims to establish and defend throughout the essay. A claim must assert your position on an issue and must be arguable. It can guide the entire argument.

2. Evidence

Evidence must consist of factual information, data, examples, or expert opinions that support the claim. Also, it lends credibility by strengthening the writer’s position.

3. Counterarguments

Presenting a counterclaim demonstrates fairness and awareness of alternative perspectives.

4. Rebuttal

After presenting the counterclaim, the writer refutes it by offering counterarguments or providing evidence that weakens the opposing viewpoint. It shows that the writer has considered multiple perspectives and is prepared to defend their position.

The format of an argumentative essay typically follows the structure to ensure clarity and effectiveness in presenting an argument.

How to Write An Argumentative Essay

Here’s a step-by-step guide on how to write an argumentative essay:

1. Introduction

- Begin with a compelling sentence or question to grab the reader’s attention.

- Provide context for the issue, including relevant facts, statistics, or historical background.

- Provide a concise thesis statement to present your position on the topic.

2. Body Paragraphs (usually three or more)

- Start each paragraph with a clear and focused topic sentence that relates to your thesis statement.

- Furthermore, provide evidence and explain the facts, statistics, examples, expert opinions, and quotations from credible sources that supports your thesis.

- Use transition sentences to smoothly move from one point to the next.

3. Counterargument and Rebuttal

- Acknowledge opposing viewpoints or potential objections to your argument.

- Also, address these counterarguments with evidence and explain why they do not weaken your position.

4. Conclusion

- Restate your thesis statement and summarize the key points you’ve made in the body of the essay.

- Leave the reader with a final thought, call to action, or broader implication related to the topic.

5. Citations and References

- Properly cite all the sources you use in your essay using a consistent citation style.

- Also, include a bibliography or works cited at the end of your essay.

6. Formatting and Style

- Follow any specific formatting guidelines provided by your instructor or institution.

- Use a professional and academic tone in your writing and edit your essay to avoid content, spelling and grammar mistakes .

Remember that the specific requirements for formatting an argumentative essay may vary depending on your instructor’s guidelines or the citation style you’re using (e.g., APA, MLA, Chicago). Always check the assignment instructions or style guide for any additional requirements or variations in formatting.

Did you understand what Prof. Mitchell explained Alex? Check it now!

Fill the Details to Check Your Score

Prof. Mitchell continued, “An argumentative essay can adopt various approaches when dealing with opposing perspectives. It may offer a balanced presentation of both sides, providing equal weight to each, or it may advocate more strongly for one side while still acknowledging the existence of opposing views.” As Alex listened carefully to the Professor’s thoughts, his eyes fell on a page with examples of argumentative essay.

Example of an Argumentative Essay

Alex picked the book and read the example. It helped him to understand the concept. Furthermore, he could now connect better to the elements and steps of the essay which Prof. Mitchell had mentioned earlier. Aren’t you keen to know how an argumentative essay should be like? Here is an example of a well-crafted argumentative essay , which was read by Alex. After Alex finished reading the example, the professor turned the page and continued, “Check this page to know the importance of writing an argumentative essay in developing skills of an individual.”

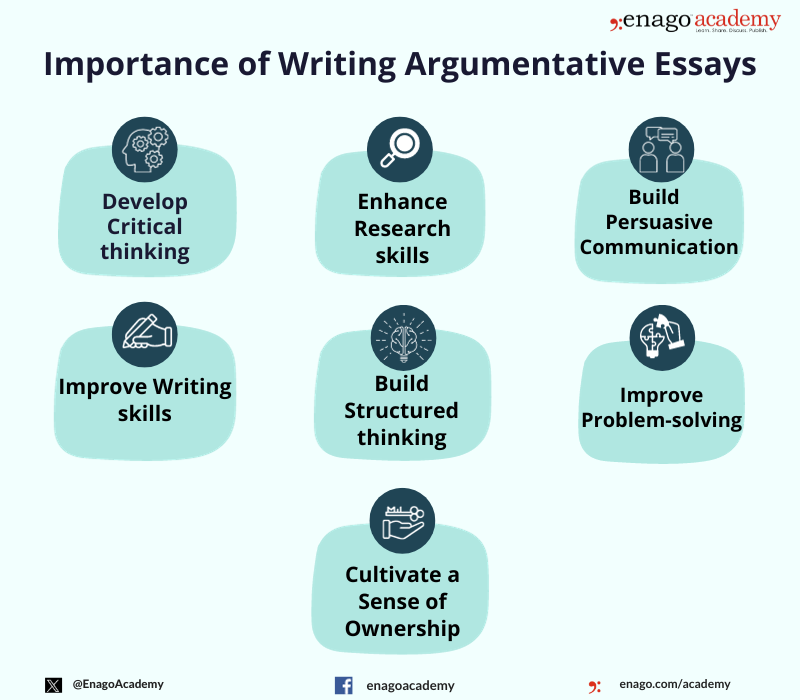

Importance of an Argumentative Essay

After understanding the benefits, Alex was convinced by the ability of the argumentative essays in advocating one’s beliefs and favor the author’s position. Alex asked,

“How are argumentative essays different from the other types?”

Prof. Mitchell answered, “Argumentative essays differ from other types of essays primarily in their purpose, structure, and approach in presenting information. Unlike expository essays, argumentative essays persuade the reader to adopt a particular point of view or take a specific action on a controversial issue. Furthermore, they differ from descriptive essays by not focusing vividly on describing a topic. Also, they are less engaging through storytelling as compared to the narrative essays.

Alex said, “Given the direct and persuasive nature of argumentative essays, can you suggest some strategies to write an effective argumentative essay?

Turning the pages of the book, Prof. Mitchell replied, “Sure! You can check this infographic to get some tips for writing an argumentative essay.”

Effective Strategies to Write an Argumentative Essay

As days turned into weeks, Alex diligently worked on his essay. He researched, gathered evidence, and refined his thesis. It was a long and challenging journey, filled with countless drafts and revisions.

Finally, the day arrived when Alex submitted their essay. As he clicked the “Submit” button, a sense of accomplishment washed over him. He realized that the argumentative essay, while challenging, had improved his critical thinking and transformed him into a more confident writer. Furthermore, Alex received feedback from his professor, a mix of praise and constructive criticism. It was a humbling experience, a reminder that every journey has its obstacles and opportunities for growth.

Frequently Asked Questions

An argumentative essay can be written as follows- 1. Choose a Topic 2. Research and Collect Evidences 3. Develop a Clear Thesis Statement 4. Outline Your Essay- Introduction, Body Paragraphs and Conclusion 5. Revise and Edit 6. Format and Cite Sources 7. Final Review

One must choose a clear, concise and specific statement as a claim. It must be debatable and establish your position. Avoid using ambiguous or unclear while making a claim. To strengthen your claim, address potential counterarguments or opposing viewpoints. Additionally, use persuasive language and rhetoric to make your claim more compelling

Starting an argument essay effectively is crucial to engage your readers and establish the context for your argument. Here’s how you can start an argument essay are: 1. Begin With an Engaging Hook 2. Provide Background Information 3. Present Your Thesis Statement 4. Briefly Outline Your Main 5. Establish Your Credibility

The key features of an argumentative essay are: 1. Clear and Specific Thesis Statement 2. Credible Evidence 3. Counterarguments 4. Structured Body Paragraph 5. Logical Flow 6. Use of Persuasive Techniques 7. Formal Language

An argumentative essay typically consists of the following main parts or sections: 1. Introduction 2. Body Paragraphs 3. Counterargument and Rebuttal 4. Conclusion 5. References (if applicable)

The main purpose of an argumentative essay is to persuade the reader to accept or agree with a particular viewpoint or position on a controversial or debatable topic. In other words, the primary goal of an argumentative essay is to convince the audience that the author's argument or thesis statement is valid, logical, and well-supported by evidence and reasoning.

Great article! The topic is simplified well! Keep up the good work

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Diversity and Inclusion

- Industry News

6 Reasons Why There is a Decline in Higher Education Enrollment: Action plan to overcome this crisis

Over the past decade, colleges and universities across the globe have witnessed a concerning trend…

- Reporting Research

Academic Essay Writing Made Simple: 4 types and tips

The pen is mightier than the sword, they say, and nowhere is this more evident…

![quality of argumentative essay What is Academic Integrity and How to Uphold it [FREE CHECKLIST]](https://www.enago.com/academy/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/FeatureImages-59-210x136.png)

Ensuring Academic Integrity and Transparency in Academic Research: A comprehensive checklist for researchers

Academic integrity is the foundation upon which the credibility and value of scientific findings are…

- AI in Academia

AI vs. AI: How to detect image manipulation and avoid academic misconduct

The scientific community is facing a new frontier of controversy as artificial intelligence (AI) is…

- Publishing News

Unified AI Guidelines Crucial as Academic Writing Embraces Generative Tools

As generative artificial intelligence (AI) tools like ChatGPT are advancing at an accelerating pace, their…

How to Effectively Cite a PDF (APA, MLA, AMA, and Chicago Style)

How to Optimize Your Research Process: A step-by-step guide

How to Improve Lab Report Writing: Best practices to follow with and without…

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

As a researcher, what do you consider most when choosing an image manipulation detector?

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Praxis Core Writing

Course: praxis core writing > unit 1, argumentative essay | quick guide.

- Source-based essay | Quick guide

- Revision in context | Quick guide

- Within-sentence punctuation | Quick guide

- Subordination and coordination | Quick guide

- Independent and dependent Clauses | Video lesson

- Parallel structure | Quick guide

- Modifier placement | Quick guide

- Shifts in verb tense | Quick guide

- Pronoun clarity | Quick guide

- Pronoun agreement | Quick guide

- Subject-verb agreement | Quick guide

- Noun agreement | Quick guide

- Frequently confused words | Quick guide

- Conventional expressions | Quick guide

- Logical comparison | Quick guide

- Concision | Quick guide

- Adjective/adverb confusion | Quick guide

- Negation | Quick guide

- Capitalization | Quick guide

- Apostrophe use | Quick guide

- Research skills | Quick guide

Argumentative essay (30 minutes)

- states or clearly implies the writer’s position or thesis

- organizes and develops ideas logically, making insightful connections between them

- clearly explains key ideas, supporting them with well-chosen reasons, examples, or details

- displays effective sentence variety

- clearly displays facility in the use of language

- is generally free from errors in grammar, usage, and mechanics

- organizes and develops ideas clearly, making connections between them

- explains key ideas, supporting them with relevant reasons, examples, or details

- displays some sentence variety

- displays facility in the use of language

- states or implies the writer’s position or thesis

- shows control in the organization and development of ideas

- explains some key ideas, supporting them with adequate reasons, examples, or details

- displays adequate use of language

- shows control of grammar, usage, and mechanics, but may display errors

- limited in stating or implying a position or thesis

- limited control in the organization and development of ideas

- inadequate reasons, examples, or details to explain key ideas

- an accumulation of errors in the use of language

- an accumulation of errors in grammar, usage, and mechanics

- no clear position or thesis

- weak organization or very little development

- few or no relevant reasons, examples, or details

- frequent serious errors in the use of language

- frequent serious errors in grammar, usage, and mechanics

- contains serious and persistent writing errors or

- is incoherent or

- is undeveloped or

- is off-topic

How should I build a thesis?

- (Choice A) Kids should find role models that are worthier than celebrities because celebrities may be famous for reasons that aren't admirable. A Kids should find role models that are worthier than celebrities because celebrities may be famous for reasons that aren't admirable.

- (Choice B) Because they profit from the admiration of youths, celebrities have a moral responsibility for the reactions their behaviors provoke in fans. B Because they profit from the admiration of youths, celebrities have a moral responsibility for the reactions their behaviors provoke in fans.

- (Choice C) Celebrities may have more imitators than most people, but they hold no more responsibility over the example they set than the average person. C Celebrities may have more imitators than most people, but they hold no more responsibility over the example they set than the average person.

- (Choice D) Notoriety is not always a choice, and some celebrities may not want to be role models. D Notoriety is not always a choice, and some celebrities may not want to be role models.

- (Choice E) Parents have a moral responsibility to serve as immediate role models for their children. E Parents have a moral responsibility to serve as immediate role models for their children.

How should I support my thesis?

- (Choice A) As basketball star Charles Barkley stated in a famous advertising campaign for Nike, he was paid to dominate on the basketball court, not to raise your kids. A As basketball star Charles Barkley stated in a famous advertising campaign for Nike, he was paid to dominate on the basketball court, not to raise your kids.

- (Choice B) Many celebrities do consider themselves responsible for setting a good example and create non-profit organizations through which they can benefit youths. B Many celebrities do consider themselves responsible for setting a good example and create non-profit organizations through which they can benefit youths.

- (Choice C) Many celebrities, like Kylie Jenner with her billion-dollar cosmetics company, profit directly from being imitated by fans who purchase sponsored products. C Many celebrities, like Kylie Jenner with her billion-dollar cosmetics company, profit directly from being imitated by fans who purchase sponsored products.

- (Choice D) My ten-year-old nephew may love Drake's music, but his behaviors are more similar to those of the adults he interacts with on a daily basis, like his parents and teachers. D My ten-year-old nephew may love Drake's music, but his behaviors are more similar to those of the adults he interacts with on a daily basis, like his parents and teachers.

- (Choice E) It's very common for young people to wear fashions similar to those of their favorite celebrities. E It's very common for young people to wear fashions similar to those of their favorite celebrities.

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

Argumentative Essay Examples to Inspire You (+ Free Formula)

.webp)

Table of contents

Meredith Sell

Have you ever been asked to explain your opinion on a controversial issue?

- Maybe your family got into a discussion about chemical pesticides

- Someone at work argues against investing resources into your project

- Your partner thinks intermittent fasting is the best way to lose weight and you disagree

Proving your point in an argumentative essay can be challenging, unless you are using a proven formula.

Argumentative essay formula & example

In the image below, you can see a recommended structure for argumentative essays. It starts with the topic sentence, which establishes the main idea of the essay. Next, this hypothesis is developed in the development stage. Then, the rebuttal, or the refutal of the main counter argument or arguments. Then, again, development of the rebuttal. This is followed by an example, and ends with a summary. This is a very basic structure, but it gives you a bird-eye-view of how a proper argumentative essay can be built.

Writing an argumentative essay (for a class, a news outlet, or just for fun) can help you improve your understanding of an issue and sharpen your thinking on the matter. Using researched facts and data, you can explain why you or others think the way you do, even while other reasonable people disagree.

Free AI argumentative essay generator > Free AI argumentative essay generator >

What Is an Argumentative Essay?

An argumentative essay is an explanatory essay that takes a side.

Instead of appealing to emotion and personal experience to change the reader’s mind, an argumentative essay uses logic and well-researched factual information to explain why the thesis in question is the most reasonable opinion on the matter.

Over several paragraphs or pages, the author systematically walks through:

- The opposition (and supporting evidence)

- The chosen thesis (and its supporting evidence)

At the end, the author leaves the decision up to the reader, trusting that the case they’ve made will do the work of changing the reader’s mind. Even if the reader’s opinion doesn’t change, they come away from the essay with a greater understanding of the perspective presented — and perhaps a better understanding of their original opinion.

All of that might make it seem like writing an argumentative essay is way harder than an emotionally-driven persuasive essay — but if you’re like me and much more comfortable spouting facts and figures than making impassioned pleas, you may find that an argumentative essay is easier to write.

Plus, the process of researching an argumentative essay means you can check your assumptions and develop an opinion that’s more based in reality than what you originally thought. I know for sure that my opinions need to be fact checked — don’t yours?

So how exactly do we write the argumentative essay?

How do you start an argumentative essay

First, gain a clear understanding of what exactly an argumentative essay is. To formulate a proper topic sentence, you have to be clear on your topic, and to explore it through research.

Students have difficulty starting an essay because the whole task seems intimidating, and they are afraid of spending too much time on the topic sentence. Experienced writers, however, know that there is no set time to spend on figuring out your topic. It's a real exploration that is based to a large extent on intuition.

6 Steps to Write an Argumentative Essay (Persuasion Formula)

Use this checklist to tackle your essay one step at a time:

1. Research an issue with an arguable question

To start, you need to identify an issue that well-informed people have varying opinions on. Here, it’s helpful to think of one core topic and how it intersects with another (or several other) issues. That intersection is where hot takes and reasonable (or unreasonable) opinions abound.

I find it helpful to stage the issue as a question.

For example:

Is it better to legislate the minimum size of chicken enclosures or to outlaw the sale of eggs from chickens who don’t have enough space?

Should snow removal policies focus more on effectively keeping roads clear for traffic or the environmental impacts of snow removal methods?

Once you have your arguable question ready, start researching the basic facts and specific opinions and arguments on the issue. Do your best to stay focused on gathering information that is directly relevant to your topic. Depending on what your essay is for, you may reference academic studies, government reports, or newspaper articles.

Research your opposition and the facts that support their viewpoint as much as you research your own position . You’ll need to address your opposition in your essay, so you’ll want to know their argument from the inside out.

2. Choose a side based on your research

You likely started with an inclination toward one side or the other, but your research should ultimately shape your perspective. So once you’ve completed the research, nail down your opinion and start articulating the what and why of your take.

What: I think it’s better to outlaw selling eggs from chickens whose enclosures are too small.

Why: Because if you regulate the enclosure size directly, egg producers outside of the government’s jurisdiction could ship eggs into your territory and put nearby egg producers out of business by offering better prices because they don’t have the added cost of larger enclosures.

This is an early form of your thesis and the basic logic of your argument. You’ll want to iterate on this a few times and develop a one-sentence statement that sums up the thesis of your essay.

Thesis: Outlawing the sale of eggs from chickens with cramped living spaces is better for business than regulating the size of chicken enclosures.

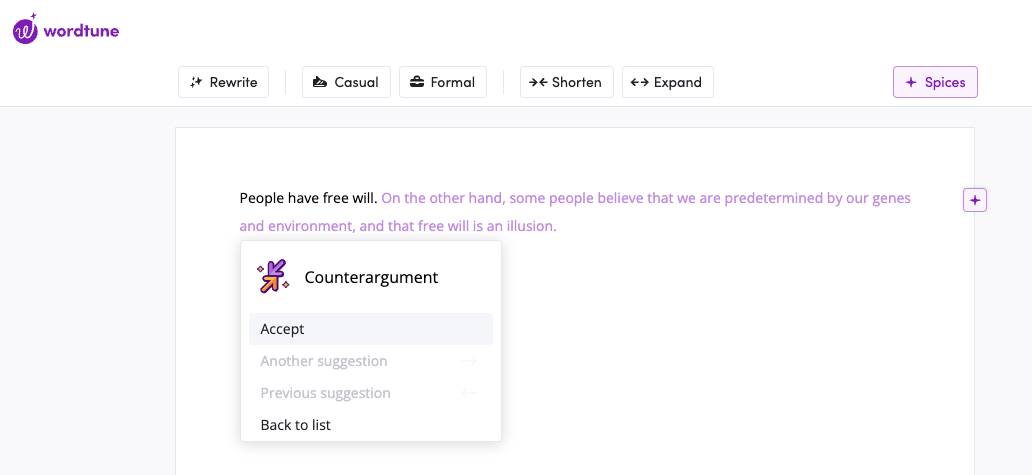

Now that you’ve articulated your thesis , spell out the counterargument(s) as well. Putting your opposition’s take into words will help you throughout the rest of the essay-writing process. (You can start by choosing the counter argument option with Wordtune Spices .)

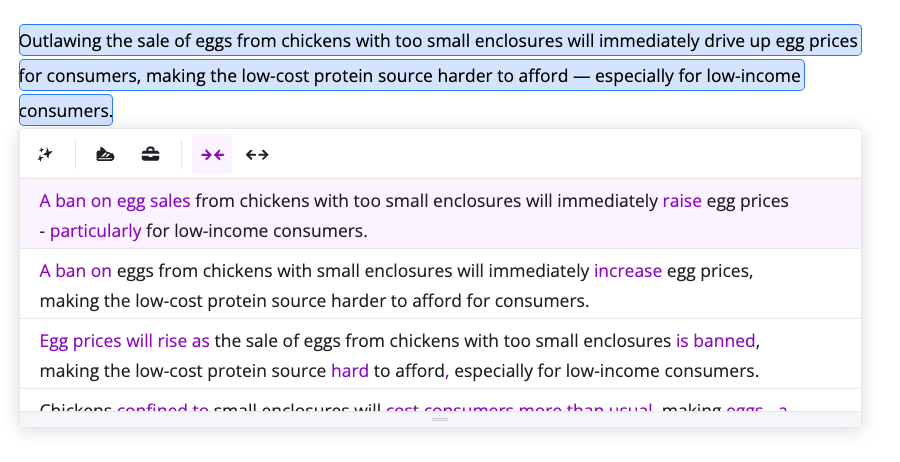

Counterargument: Outlawing the sale of eggs from chickens with too small enclosures will immediately drive up egg prices for consumers, making the low-cost protein source harder to afford — especially for low-income consumers.

There may be one main counterargument to articulate, or several. Write them all out and start thinking about how you’ll use evidence to address each of them or show why your argument is still the best option.

3. Organize the evidence — for your side and the opposition

You did all of that research for a reason. Now’s the time to use it.

Hopefully, you kept detailed notes in a document, complete with links and titles of all your source material. Go through your research document and copy the evidence for your argument and your opposition’s into another document.

List the main points of your argument. Then, below each point, paste the evidence that backs them up.

If you’re writing about chicken enclosures, maybe you found evidence that shows the spread of disease among birds kept in close quarters is worse than among birds who have more space. Or maybe you found information that says eggs from free-range chickens are more flavorful or nutritious. Put that information next to the appropriate part of your argument.

Repeat the process with your opposition’s argument: What information did you find that supports your opposition? Paste it beside your opposition’s argument.

You could also put information here that refutes your opposition, but organize it in a way that clearly tells you — at a glance — that the information disproves their point.

Counterargument: Outlawing the sale of eggs from chickens with too small enclosures will immediately drive up egg prices for consumers.

BUT: Sicknesses like avian flu spread more easily through small enclosures and could cause a shortage that would drive up egg prices naturally, so ensuring larger enclosures is still a better policy for consumers over the long term.

As you organize your research and see the evidence all together, start thinking through the best way to order your points.

Will it be better to present your argument all at once or to break it up with opposition claims you can quickly refute? Would some points set up other points well? Does a more complicated point require that the reader understands a simpler point first?

Play around and rearrange your notes to see how your essay might flow one way or another.

4. Freewrite or outline to think through your argument

Is your brain buzzing yet? At this point in the process, it can be helpful to take out a notebook or open a fresh document and dump whatever you’re thinking on the page.

Where should your essay start? What ground-level information do you need to provide your readers before you can dive into the issue?

Use your organized evidence document from step 3 to think through your argument from beginning to end, and determine the structure of your essay.

There are three typical structures for argumentative essays:

- Make your argument and tackle opposition claims one by one, as they come up in relation to the points of your argument - In this approach, the whole essay — from beginning to end — focuses on your argument, but as you make each point, you address the relevant opposition claims individually. This approach works well if your opposition’s views can be quickly explained and refuted and if they directly relate to specific points in your argument.

- Make the bulk of your argument, and then address the opposition all at once in a paragraph (or a few) - This approach puts the opposition in its own section, separate from your main argument. After you’ve made your case, with ample evidence to convince your readers, you write about the opposition, explaining their viewpoint and supporting evidence — and showing readers why the opposition’s argument is unconvincing. Once you’ve addressed the opposition, you write a conclusion that sums up why your argument is the better one.

- Open your essay by talking about the opposition and where it falls short. Build your entire argument to show how it is superior to that opposition - With this structure, you’re showing your readers “a better way” to address the issue. After opening your piece by showing how your opposition’s approaches fail, you launch into your argument, providing readers with ample evidence that backs you up.

As you think through your argument and examine your evidence document, consider which structure will serve your argument best. Sketch out an outline to give yourself a map to follow in the writing process. You could also rearrange your evidence document again to match your outline, so it will be easy to find what you need when you start writing.

5. Write your first draft

You have an outline and an organized document with all your points and evidence lined up and ready. Now you just have to write your essay.

In your first draft, focus on getting your ideas on the page. Your wording may not be perfect (whose is?), but you know what you’re trying to say — so even if you’re overly wordy and taking too much space to say what you need to say, put those words on the page.

Follow your outline, and draw from that evidence document to flesh out each point of your argument. Explain what the evidence means for your argument and your opposition. Connect the dots for your readers so they can follow you, point by point, and understand what you’re trying to say.

As you write, be sure to include:

1. Any background information your reader needs in order to understand the issue in question.

2. Evidence for both your argument and the counterargument(s). This shows that you’ve done your homework and builds trust with your reader, while also setting you up to make a more convincing argument. (If you find gaps in your research while you’re writing, Wordtune Spices can source statistics or historical facts on the fly!)

Get Wordtune for free > Get Wordtune for free >