American writer Joan Didion's 1992 book of essays written after the death of her friend and editor Robbins: 2 wds. - Daily Themed Crossword

Hello everyone! Thank you visiting our website, here you will be able to find all the answers for Daily Themed Crossword Game (DTC). Daily Themed Crossword is the new wonderful word game developed by PlaySimple Games, known by his best puzzle word games on the android and apple store. A fun crossword game with each day connected to a different theme. Choose from a range of topics like Movies, Sports, Technology, Games, History, Architecture and more! Access to hundreds of puzzles, right on your Android device, so play or review your crosswords when you want, wherever you want! Give your brain some exercise and solve your way through brilliant crosswords published every day! Increase your vocabulary and general knowledge. Become a master crossword solver while having tons of fun, and all for free! The answers are divided into several pages to keep it clear. This page contains answers to puzzle American writer Joan Didion's 1992 book of essays written after the death of her friend and editor Robbins: 2 wds..

American writer Joan Didion's 1992 book of essays written after the death of her friend and editor Robbins: 2 wds.

The answer to this question:

More answers from this level:

- "It's ___" (slang for "done")

- "Hell ___ No Fury"

- Throbbing pain

- Byron's "before"

- Swamp plant

- "Wish ___ a Star"

- "Off the ___" (unnoticed)

- Actor Noah who plays Dr. Carter on "ER"

- Nemo or Dory

- Actor Elgort of "The Fault In Our Stars"

- Personal watercraft from Kawasaki that was presented at the 2018 Oscars: 2 wds.

- "Whoops"

The best free cultural &

educational media on the web

- Online Courses

- Certificates

- Degrees & Mini-Degrees

- Audio Books

Read 12 Masterful Essays by Joan Didion for Free Online, Spanning Her Career From 1965 to 2013

in Literature , Writing | January 14th, 2014 3 Comments

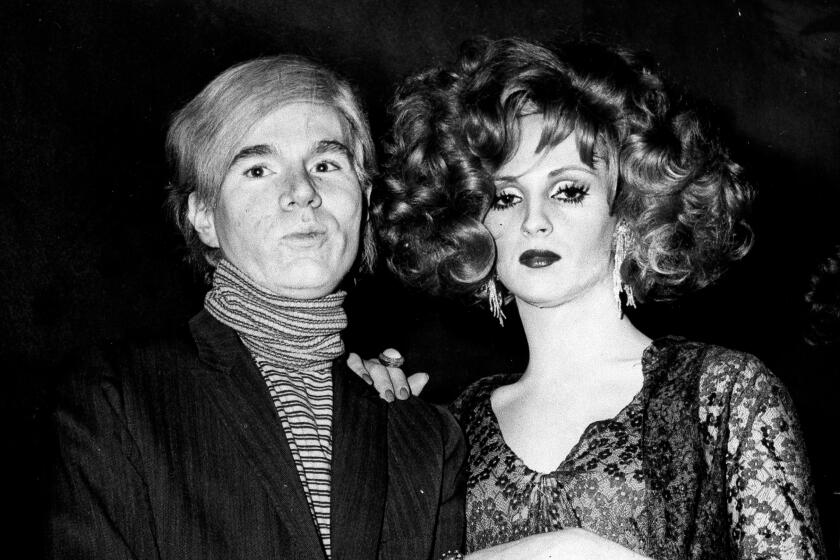

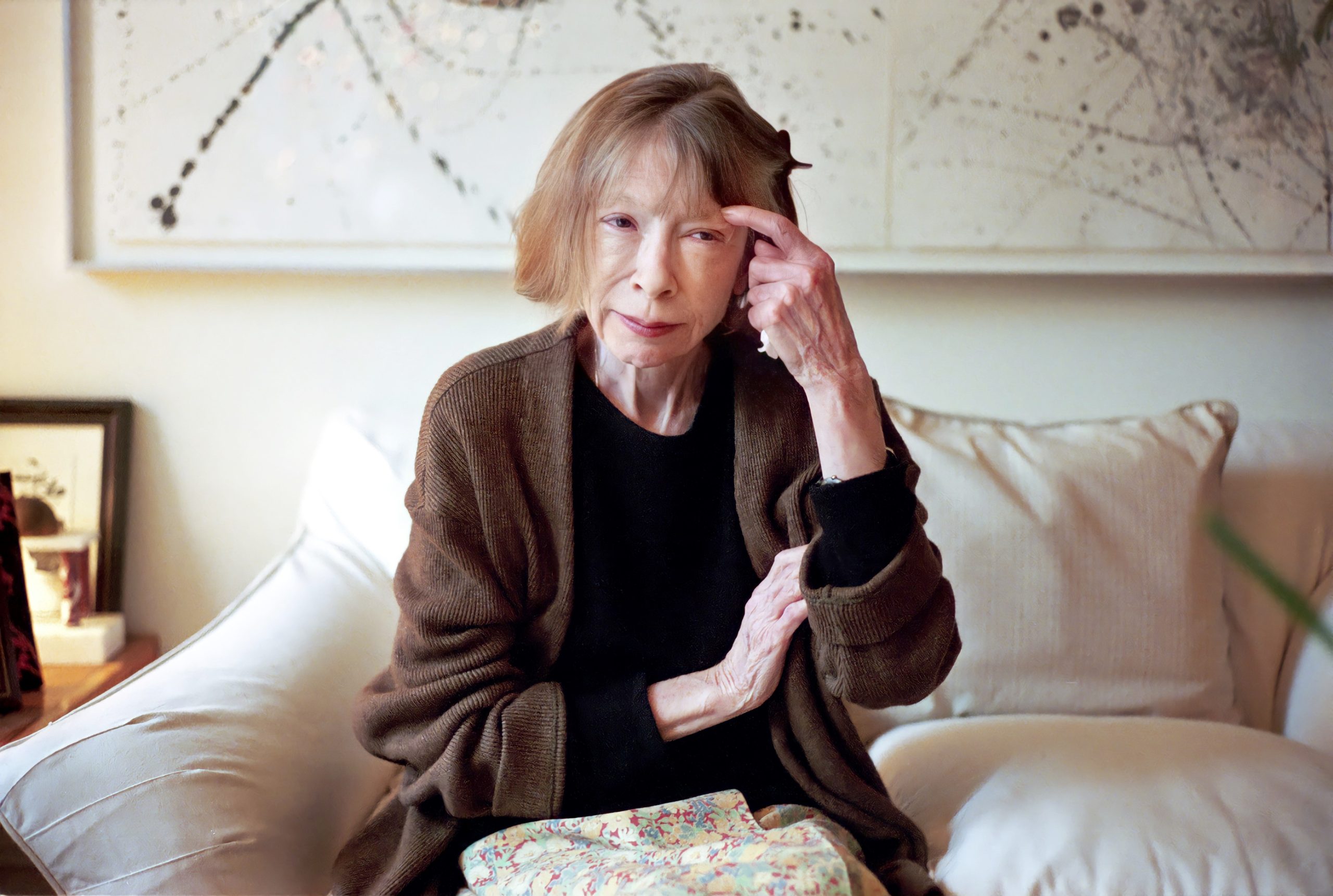

Image by David Shankbone, via Wikimedia Commons

In a classic essay of Joan Didion’s, “Goodbye to All That,” the novelist and writer breaks into her narrative—not for the first or last time—to prod her reader. She rhetorically asks and answers: “…was anyone ever so young? I am here to tell you that someone was.” The wry little moment is perfectly indicative of Didion’s unsparingly ironic critical voice. Didion is a consummate critic, from Greek kritēs , “a judge.” But she is always foremost a judge of herself. An account of Didion’s eight years in New York City, where she wrote her first novel while working for Vogue , “Goodbye to All That” frequently shifts point of view as Didion examines the truth of each statement, her prose moving seamlessly from deliberation to commentary, annotation, aside, and aphorism, like the below:

I want to explain to you, and in the process perhaps to myself, why I no longer live in New York. It is often said that New York is a city for only the very rich and the very poor. It is less often said that New York is also, at least for those of us who came there from somewhere else, a city only for the very young.

Anyone who has ever loved and left New York—or any life-altering city—will know the pangs of resignation Didion captures. These economic times and every other produce many such stories. But Didion made something entirely new of familiar sentiments. Although her essay has inspired a sub-genre , and a collection of breakup letters to New York with the same title, the unsentimental precision and compactness of Didion’s prose is all her own.

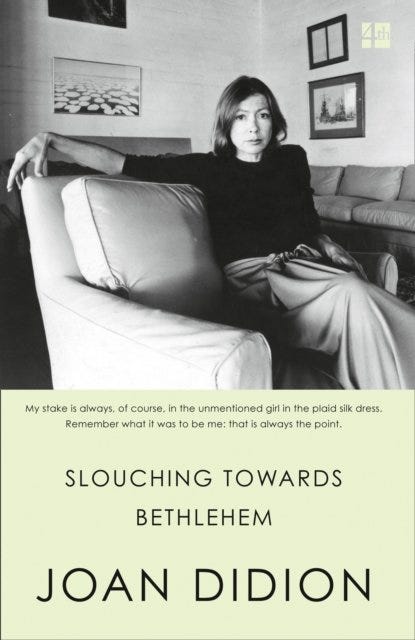

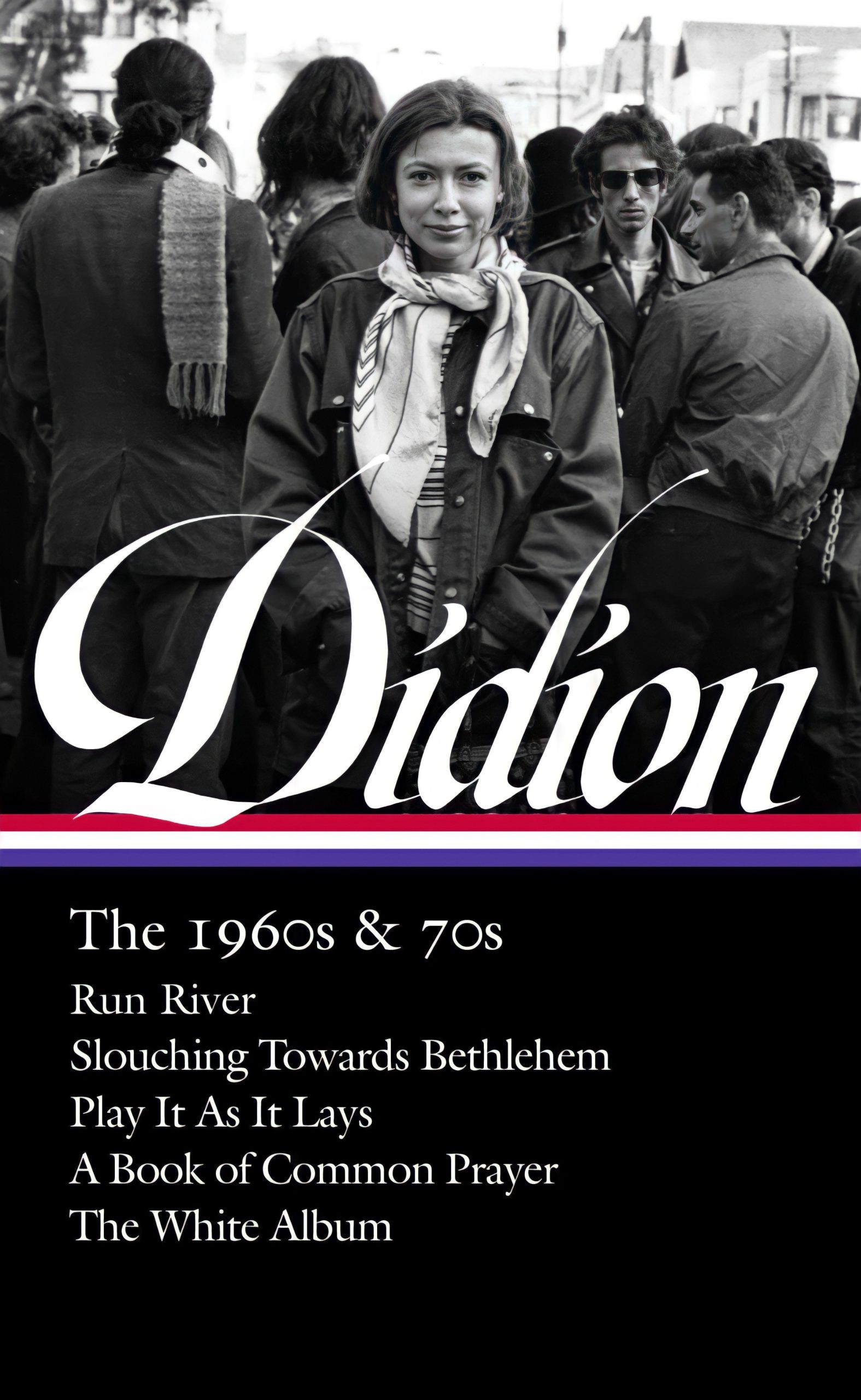

The essay appears in 1967’s Slouching Towards Bethlehem , a representative text of the literary nonfiction of the sixties alongside the work of John McPhee, Terry Southern, Tom Wolfe, and Hunter S. Thompson. In Didion’s case, the emphasis must be decidedly on the literary —her essays are as skillfully and imaginatively written as her fiction and in close conversation with their authorial forebears. “Goodbye to All That” takes its title from an earlier memoir, poet and critic Robert Graves’ 1929 account of leaving his hometown in England to fight in World War I. Didion’s appropriation of the title shows in part an ironic undercutting of the memoir as a serious piece of writing.

And yet she is perhaps best known for her work in the genre. Published almost fifty years after Slouching Towards Bethlehem , her 2005 memoir The Year of Magical Thinking is, in poet Robert Pinsky’s words , a “traveler’s faithful account” of the stunningly sudden and crushing personal calamities that claimed the lives of her husband and daughter separately. “Though the material is literally terrible,” Pinsky writes, “the writing is exhilarating and what unfolds resembles an adventure narrative: a forced expedition into those ‘cliffs of fall’ identified by Hopkins.” He refers to lines by the gifted Jesuit poet Gerard Manley Hopkins that Didion quotes in the book: “O the mind, mind has mountains; cliffs of fall / Frightful, sheer, no-man-fathomed. Hold them cheap / May who ne’er hung there.”

The nearly unimpeachably authoritative ethos of Didion’s voice convinces us that she can fearlessly traverse a wild inner landscape most of us trivialize, “hold cheap,” or cannot fathom. And yet, in a 1978 Paris Review interview , Didion—with that technical sleight of hand that is her casual mastery—called herself “a kind of apprentice plumber of fiction, a Cluny Brown at the writer’s trade.” Here she invokes a kind of archetype of literary modesty (John Locke, for example, called himself an “underlabourer” of knowledge) while also figuring herself as the winsome heroine of a 1946 Ernst Lubitsch comedy about a social climber plumber’s niece played by Jennifer Jones, a character who learns to thumb her nose at power and privilege.

A twist of fate—interviewer Linda Kuehl’s death—meant that Didion wrote her own introduction to the Paris Review interview, a very unusual occurrence that allows her to assume the role of her own interpreter, offering ironic prefatory remarks on her self-understanding. After the introduction, it’s difficult not to read the interview as a self-interrogation. Asked about her characterization of writing as a “hostile act” against readers, Didion says, “Obviously I listen to a reader, but the only reader I hear is me. I am always writing to myself. So very possibly I’m committing an aggressive and hostile act toward myself.”

It’s a curious statement. Didion’s cutting wit and fearless vulnerability take in seemingly all—the expanses of her inner world and political scandals and geopolitical intrigues of the outer, which she has dissected for the better part of half a century. Below, we have assembled a selection of Didion’s best essays online. We begin with one from Vogue :

“On Self Respect” (1961)

Didion’s 1979 essay collection The White Album brought together some of her most trenchant and searching essays about her immersion in the counterculture, and the ideological fault lines of the late sixties and seventies. The title essay begins with a gemlike sentence that became the title of a collection of her first seven volumes of nonfiction : “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” Read two essays from that collection below:

“ The Women’s Movement ” (1972)

“ Holy Water ” (1977)

Didion has maintained a vigorous presence at the New York Review of Books since the late seventies, writing primarily on politics. Below are a few of her best known pieces for them:

“ Insider Baseball ” (1988)

“ Eye on the Prize ” (1992)

“ The Teachings of Speaker Gingrich ” (1995)

“ Fixed Opinions, or the Hinge of History ” (2003)

“ Politics in the New Normal America ” (2004)

“ The Case of Theresa Schiavo ” (2005)

“ The Deferential Spirit ” (2013)

“ California Notes ” (2016)

Didion continues to write with as much style and sensitivity as she did in her first collection, her voice refined by a lifetime of experience in self-examination and piercing critical appraisal. She got her start at Vogue in the late fifties, and in 2011, she published an autobiographical essay there that returns to the theme of “yearning for a glamorous, grown up life” that she explored in “Goodbye to All That.” In “ Sable and Dark Glasses ,” Didion’s gaze is steadier, her focus this time not on the naïve young woman tempered and hardened by New York, but on herself as a child “determined to bypass childhood” and emerge as a poised, self-confident 24-year old sophisticate—the perfect New Yorker she never became.

Related Content:

Joan Didion Reads From New Memoir, Blue Nights, in Short Film Directed by Griffin Dunne

30 Free Essays & Stories by David Foster Wallace on the Web

10 Free Stories by George Saunders, Author of Tenth of December , “The Best Book You’ll Read This Year”

Read 18 Short Stories From Nobel Prize-Winning Writer Alice Munro Free Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

by Josh Jones | Permalink | Comments (3) |

Related posts:

Comments (3), 3 comments so far.

“In a classic essay of Joan Didion’s, “Goodbye to All That,” the novelist and writer breaks into her narrative—not for the first or last time,..”

Dead link to the essay

It should be “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” with the “s” on Towards.

Most of the Joan Didion Essay links have paywalls.

Add a comment

Leave a reply.

Name (required)

Email (required)

XHTML: You can use these tags: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>

Click here to cancel reply.

- 1,700 Free Online Courses

- 200 Online Certificate Programs

- 100+ Online Degree & Mini-Degree Programs

- 1,150 Free Movies

- 1,000 Free Audio Books

- 150+ Best Podcasts

- 800 Free eBooks

- 200 Free Textbooks

- 300 Free Language Lessons

- 150 Free Business Courses

- Free K-12 Education

- Get Our Daily Email

Free Courses

- Art & Art History

- Classics/Ancient World

- Computer Science

- Data Science

- Engineering

- Environment

- Political Science

- Writing & Journalism

- All 1500 Free Courses

- 1000+ MOOCs & Certificate Courses

Receive our Daily Email

Free updates, get our daily email.

Get the best cultural and educational resources on the web curated for you in a daily email. We never spam. Unsubscribe at any time.

FOLLOW ON SOCIAL MEDIA

Free Movies

- 1150 Free Movies Online

- Free Film Noir

- Silent Films

- Documentaries

- Martial Arts/Kung Fu

- Free Hitchcock Films

- Free Charlie Chaplin

- Free John Wayne Movies

- Free Tarkovsky Films

- Free Dziga Vertov

- Free Oscar Winners

- Free Language Lessons

- All Languages

Free eBooks

- 700 Free eBooks

- Free Philosophy eBooks

- The Harvard Classics

- Philip K. Dick Stories

- Neil Gaiman Stories

- David Foster Wallace Stories & Essays

- Hemingway Stories

- Great Gatsby & Other Fitzgerald Novels

- HP Lovecraft

- Edgar Allan Poe

- Free Alice Munro Stories

- Jennifer Egan Stories

- George Saunders Stories

- Hunter S. Thompson Essays

- Joan Didion Essays

- Gabriel Garcia Marquez Stories

- David Sedaris Stories

- Stephen King

- Golden Age Comics

- Free Books by UC Press

- Life Changing Books

Free Audio Books

- 700 Free Audio Books

- Free Audio Books: Fiction

- Free Audio Books: Poetry

- Free Audio Books: Non-Fiction

Free Textbooks

- Free Physics Textbooks

- Free Computer Science Textbooks

- Free Math Textbooks

K-12 Resources

- Free Video Lessons

- Web Resources by Subject

- Quality YouTube Channels

- Teacher Resources

- All Free Kids Resources

Free Art & Images

- All Art Images & Books

- The Rijksmuseum

- Smithsonian

- The Guggenheim

- The National Gallery

- The Whitney

- LA County Museum

- Stanford University

- British Library

- Google Art Project

- French Revolution

- Getty Images

- Guggenheim Art Books

- Met Art Books

- Getty Art Books

- New York Public Library Maps

- Museum of New Zealand

- Smarthistory

- Coloring Books

- All Bach Organ Works

- All of Bach

- 80,000 Classical Music Scores

- Free Classical Music

- Live Classical Music

- 9,000 Grateful Dead Concerts

- Alan Lomax Blues & Folk Archive

Writing Tips

- William Zinsser

- Kurt Vonnegut

- Toni Morrison

- Margaret Atwood

- David Ogilvy

- Billy Wilder

- All posts by date

Personal Finance

- Open Personal Finance

- Amazon Kindle

- Architecture

- Artificial Intelligence

- Beat & Tweets

- Comics/Cartoons

- Current Affairs

- English Language

- Entrepreneurship

- Food & Drink

- Graduation Speech

- How to Learn for Free

- Internet Archive

- Language Lessons

- Most Popular

- Neuroscience

- Photography

- Pretty Much Pop

- Productivity

- UC Berkeley

- Uncategorized

- Video - Arts & Culture

- Video - Politics/Society

- Video - Science

- Video Games

Great Lectures

- Michel Foucault

- Sun Ra at UC Berkeley

- Richard Feynman

- Joseph Campbell

- Jorge Luis Borges

- Leonard Bernstein

- Richard Dawkins

- Buckminster Fuller

- Walter Kaufmann on Existentialism

- Jacques Lacan

- Roland Barthes

- Nobel Lectures by Writers

- Bertrand Russell

- Oxford Philosophy Lectures

Open Culture scours the web for the best educational media. We find the free courses and audio books you need, the language lessons & educational videos you want, and plenty of enlightenment in between.

Great Recordings

- T.S. Eliot Reads Waste Land

- Sylvia Plath - Ariel

- Joyce Reads Ulysses

- Joyce - Finnegans Wake

- Patti Smith Reads Virginia Woolf

- Albert Einstein

- Charles Bukowski

- Bill Murray

- Fitzgerald Reads Shakespeare

- William Faulkner

- Flannery O'Connor

- Tolkien - The Hobbit

- Allen Ginsberg - Howl

- Dylan Thomas

- Anne Sexton

- John Cheever

- David Foster Wallace

Book Lists By

- Neil deGrasse Tyson

- Ernest Hemingway

- F. Scott Fitzgerald

- Allen Ginsberg

- Patti Smith

- Henry Miller

- Christopher Hitchens

- Joseph Brodsky

- Donald Barthelme

- David Bowie

- Samuel Beckett

- Art Garfunkel

- Marilyn Monroe

- Picks by Female Creatives

- Zadie Smith & Gary Shteyngart

- Lynda Barry

Favorite Movies

- Kurosawa's 100

- David Lynch

- Werner Herzog

- Woody Allen

- Wes Anderson

- Luis Buñuel

- Roger Ebert

- Susan Sontag

- Scorsese Foreign Films

- Philosophy Films

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

©2006-2024 Open Culture, LLC. All rights reserved.

- Advertise with Us

- Copyright Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

Shop TODAY All Stars: Vote for your favorite spring finds

- TODAY Plaza

- Share this —

- Watch Full Episodes

- Read With Jenna

- Inspirational

- Relationships

- TODAY Table

- Newsletters

- Start TODAY

- Shop TODAY Awards

- Citi Music Series

- Listen All Day

Follow today

More Brands

- On The Show

Joan Didion’s best books, from essays to fiction

On Thursday, it was announced that prolific writer Joan Didion had died at the age of 87.

An executive at her publisher, Knopf, confirmed the author's death to TODAY in an email and said that Didion passed away at her home in Manhattan from Parkinson's disease.

Here, we round up seven necessary reads by the late author, who was best known for work on mourning and essays and magazine contributions that captured the American experience.

Here are the best books by Joan Didion:

'the year of magical thinking' (2005).

Probably her best known work, this gutting work of non-fiction profiles Didion's experience grieving her husband John Gregory Dunne while caring for comatose daughter Quintana Roo Dunne.

"The Year of Magical Thinking" quickly became an iconic representation of mourning, capturing the sorrow and ennui of that period. It won numerous awards, including the Pulitzer Prize and National Book Awards, and was later adapted into a play starring Vanessa Redgrave.

'Blue Nights' (2011)

A continuation of what is started in "The Year of Magical Thinking," this poignant 2011 work of non-fiction features personal and heartbreaking memories of Quintana, who passed away at the age of 39, not long after Didion's husband died.

"It is a searing inquiry into loss and a melancholy meditation on mortality and time,” wrote book critic Michiko Kakutani of the New York Times.

'Slouching Towards Bethlehem' (1968)

Didion's first collection of nonfiction writing is revered as an essential portrait of America — particularly California — in the 1960s.

It focuses on her experience growing up in the Sunshine state, icons of that time John Wayne and Howard Hughes, and the essence of Haight-Ashbury, a neighborhood in San Francisco that became the heart of the counterculture movement.

'The White Album' (1979)

A reflective collection of essays, "The White Album" explores several of the same topics Didion touched on in "Slouching Towards Bethlehem," this time focusing on the history and politics of California in the late 1960s and early '70s. Its matter-of-fact and intimate stories give the reader a feeling of what California and the atmosphere was like during that time period.

'Play it as it Lays' (1970)

Set during a time before Roe vs. Wade, this terrifying and at times disturbing novel profiles a struggling actress living in Los Angeles whose life begins to unravel after she has a back-alley abortion.

"(Didion) writes with a razor, carving her characters out of her perceptions with strokes so swift and economical that each scene ends almost before the reader is aware of it, and yet the characters go on bleeding afterward," wrote book critic John Leonard for the New York times.

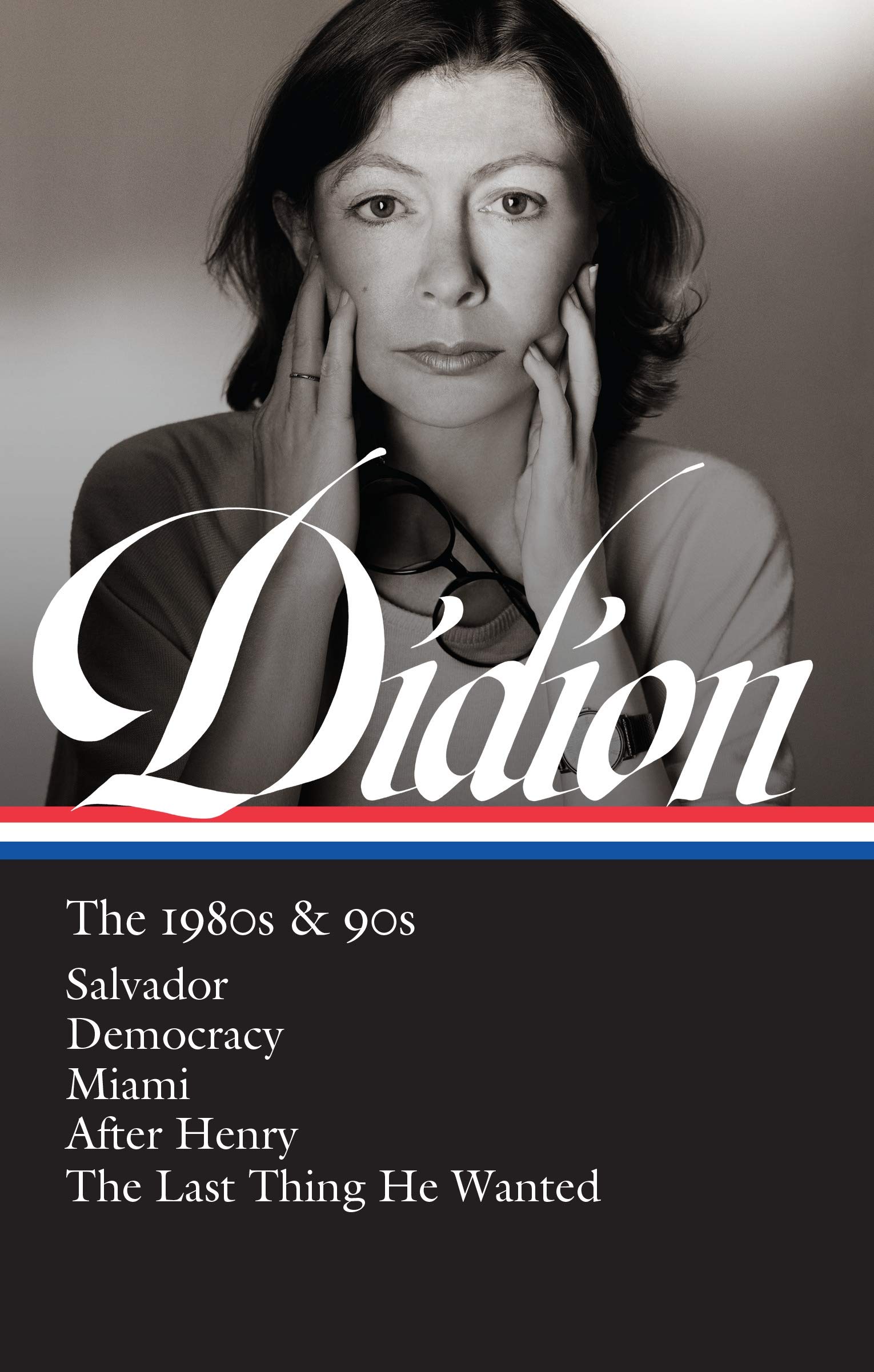

'Miami' (1987)

A great example of Didion's journalistic work, "Miami" paints a portrait of life for Cuban exiles in the south Florida city.

Didion writes a stunning and passionate page-turner set against the backdrop of Miami’s decline caused by economic and political changes with the refugee immigration from Cuba after Fidel Castro’s rise to power.

Alexander Kacala is a reporter and editor at TODAY Digital and NBC OUT. He loves writing about pop culture, trending topics, LGBTQ issues, style and all things drag. His favorite celebrity profiles include Cher — who said their interview was one of the most interesting of her career — as well as Kylie Minogue, Candice Bergen, Patti Smith and RuPaul. He is based in New York City and his favorite film is “Pretty Woman.”

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Let Me Tell You What I Mean by Joan Didion review – elegant essays spanning four decades

Rejection letters, California dreams and clear reflections on writing in a collection that explores self-doubt

I n the first essay of this new volume of previously uncollected pieces, Joan Didion makes a case against newspapers. Too often, she argues, their reporting style rests on “a quite factitious ‘ objectivity’”, which “lends the entire venture a mendacity” by failing to make explicit the writer’s own particular set of influences and biases. Didion praises instead magazines that cultivate a personal voice, and which aim to impart character and atmosphere rather than straightforward information: “They assume that the reader is a friend, that he is disturbed about something, and that he will understand if they talk to him straight; this assumption of a shared language and a common ethic lends their reports a considerable cogency of style.” Often, she concludes, the real story is “the story not in the newspaper”.

This could be read as a slanted manifesto for Didion’s own style. Across her 60-year career, from her landmark essay collections Slouching Towards Bethlehem (1968) and The White Album (1979), through her formally innovative novels, to her devastating 2005 memoir The Year of Magical Thinking , Didion has established a way of narration that focuses not so much on events as on subtexts, atmospheres and perceptions. She is usually present in her essays as a voice rather than a character, observer rather than participant – though the boundaries regularly blur. Yet even when she’s not saying directly what she’s feeling, it’s there in the architecture of every cool, clear sentence, in the sounds, gestures and images on which she chooses to focus her attention.

At university, Didion writes here in mock self-deprecation, “I would try to contemplate the Hegelian dialectic and would find myself concentrating instead on a flowering pear tree outside my window and the particular way the petals fell on my floor”. Half of the 12 essays in this collection were written for the Saturday Evening Post in the late 1960s, while the latest is from 2000; in them we see Didion exploring the possibility of that attention to detail, working out who exactly the “I” in her writing is, and what it is she’s seeing.

Didion’s essay collections have always included overtly personal moments – “We are here on this island in the middle of the Pacific in lieu of filing for divorce,” she writes in “In the Islands” from The White Book , adding: “I tell you this not as aimless revelation but because I want you to know, as you read me, precisely who I am and where I am and what is on my mind.” This new collection contains several pieces of relatively straight autobiography: a funny essay describing the pain of her rejection from Stanford and subsequent summer spent “in sullen but mild rebellion” (“On Being Unchosen by the College of One’s Choice”); “Telling Stories”, which describes how out of place the 19-year-old Didion felt in the writers’ workshop she took for a semester in 1954, attempting to remain inconspicuous by shrinking into her raincoat while others regaled the group with experiences that seemed far more redolent of the “writer’s life” – international, glamorous, drug-induced – than anything Didion had known growing up in Sacramento. (She went on to take a job composing advertising copy for Vogue, which she credits with teaching her to write.) The same essay includes a ream of rejection letters for an early short story widely condemned as too depressing: “I’m sorry,” wrote a representative of Good Housekeeping magazine, “we are seldom inclined to give our readers this bad a time.”

But the pieces most revealing of Didion’s self are those that discuss the act of writing itself. In “Why I Write” (1976) Didion directly confronts the question of the first person – of what it means for a writer to assume an identity on the page and a relationship with an invisible reader. “In many ways,” she observes, “writing is the act of saying I, of imposing oneself upon other people, of saying listen to me, see it my way, change your mind .” In another essay, on Hemingway’s style, she parses precisely how the very grammar of his sentences reveal “a certain way of looking at the world”: Didion too has a specific way of looking that binds together all her work, whether she’s watching Nancy Reagan pretend to pick flowers for a photoshoot, attending a meeting of Gamblers Anonymous or a reunion of airforce veterans in a Las Vegas hospitality suite, or parsing the mission statement of Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia LLC. Didion writes of “needing room in which to play with what I did not understand”. Her pieces often feel ambiguous, even ambivalent, and her detachment can at times be bemusing: the reader is left wondering where her stake is grounded in the stories she tells. Yet her particular skill lies in asking questions too far-reaching to be contained on the page, that reverberate far beyond the essay, as her images lodge themselves in the reader’s conscience.

The collection – expansively introduced by Hilton Als – touches on many of the themes that run through Didion’s work: the power of illusion, which she learned about at Vogue and later in Hollywood; the unspoken dynamics of makeshift, often precarious communities; the dangerous thrill of pursuing dreams. Recalling San Simeon, the castle on a hill in California which she would glimpse from the highway as a child, she reflects on the impact of knowing that just beyond reach lay this opulent paradise of shimmering turrets and battlements. “San Simeon,” she writes, “was an imaginative idea that affected me, shaped my own imagination in the way that all children are shaped by the actual and emotional geography of the place in which they grow up, by the stories they are told and the stories they invent.” There’s an echo here of Didion’s most famous line: “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” In that essay – “The White Album” – Didion describes a period between 1966 and 1971 when she “I began to doubt the premises of all the stories I had ever told myself”. Let Me Tell You What I Mean , its chapters largely rooted in this discombobulating period, is a valuable addition to the literature of self-doubt and self-awareness, an elegant untangling of what and why we remember and forget.

- Joan Didion

Most viewed

The essential Joan Didion: An L.A. Times reading list for newcomers and fans alike

- Show more sharing options

- Copy Link URL Copied!

Joan Didion, who died Thursday at 87 , produced decades’ worth of memorable work across genres and subjects: personal essays, reporting and criticism on pop culture, political dispatches from at home and abroad and, near the end of her career, a bestselling memoir and a follow-up. Whether you’re a newcomer looking for a place to start or a reader looking to dive deeper, here’s a guide to Didion’s writing, start to finish:

The ‘personals’

If any subset of her work made Didion’s reputation for “inevitable” sentences, it is the personal essays collected in “Slouching Towards Bethlehem” (1968) and “The White Album” (1979). These pieces, starting with “On Self-Respect” in 1961, and originally published in magazines such as Vogue, the American Scholar and the Saturday Evening Post, have come to be appreciated as models of the form, elliptical, poetic, punctuated with the author’s eye for telling detail and lacerating self-awareness. Didion’s essays carefully revealed, and concealed, the correspondent’s inner life: As she once wrote of husband John Gregory Dunne — in a piece he edited — “We are here on this island in the middle of the Pacific in lieu of filing for divorce.”

Didion later described these essays as having been written under “crash circumstances” — “On Self-Respect” was improvised in “two sittings,” she reflected in 2007 , and written “not just to a word count or a line count but a character count” — yet they produced an astonishing number of unforgettable phrases: “I’ve already lost touch with a couple people I used to be” ( “On Keeping a Notebook,” a personal favorite); “That was the year, my twenty-eighth, when I was discovering that not all of the promises would be kept” ( “Goodbye to All That,” which invented the modern “leaving New York” essay); “We tell ourselves stories in order to live” (“The White Album,” possibly the definitive rendering of the end of the ‘60s).

Joan Didion, masterful essayist, novelist and screenwriter, dies at 87

Didion bridged the world of Hollywood, journalism and literature in a career that arced most brilliantly in the realms of social criticism and memoir.

Dec. 23, 2021

A number of additional magazine pieces from her early career are collected in her final published work , “Let Me Tell You What I Mean ” (2021), and her observations of self and culture from the 1970s are central to her travelogue “South and West” (2017).

The counterculture reporting

In and among the “personals” of “Slouching” and “The White Album” are Didion’s cucumber-cool lacerations of the late ‘60s, casting twin gimlet eyes on the delusions of both the rock-ribbed squares and the child revolutionaries. From the gaudy populism of the Getty and the Sacramento Reagans to a requiem for John Wayne, the marriage of bad taste and bad money fills in where the center fails to hold. The title essay of “The White Album” swirls with Jim Morrison, the Manson “family,” Linda Kasabian’s famous dress, Huey P. Newton and all the rest as Didion bravely declines to make sense of it all. The title essay in “Slouching” culminates, likewise, in the senseless final image of a 3-year-old boy, neglected and imperiled in a hippie squat. “On Morality” and “The Women’s Movement” exude the skeptical libertarianism that distanced her from the madness.

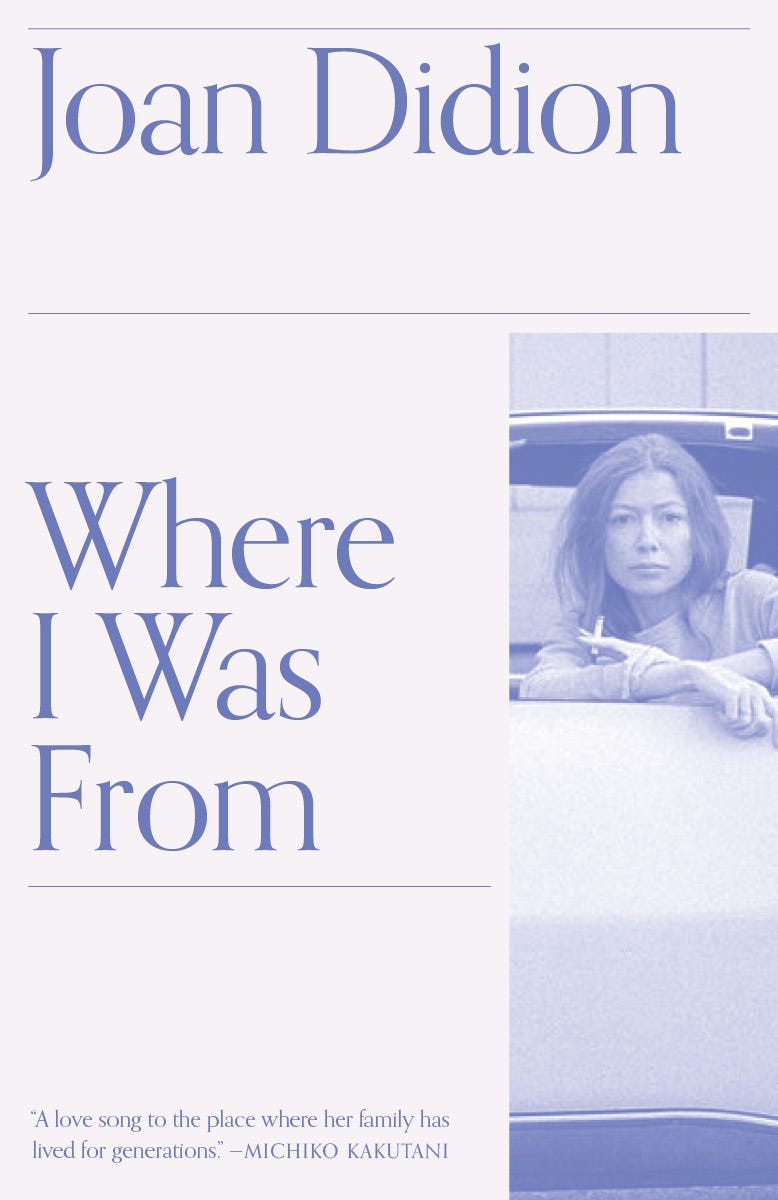

To see not just where the nation moved but where Didion did, it’s worth reading the early California pieces, including “Notes from a Native Daughter,” followed by “Where I Was From” (2003), which utterly demolishes California’s disastrous myth of self-reliance step by step, anatomizing its dependence on government largesse from the days of the Gold Rush — the water, the power, the military-industrial muscle. And finally she goes in on herself: the pioneer woman who never was.

Throughout her career, Didion was best known for her nonfiction, but her five novels conjure an equally pungent sense of place and time. Her first book, “Run River ” (1963) — inspired, she later wrote, by profound homesickness — is a family melodrama about the descendants of pioneers that draws heavily on Didion’s Sacramento upbringing. Perhaps her most famous novel, “Play It As It Lays” (1970), is set in a very different California: the Hollywood of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, suffused with the anomie of its dissolute heroine, Maria Wyeth. (Her opening monologue famously begins with an ice-cold allusion to Othello: “What makes Iago evil? Some people ask. I never ask.”)

But Didion’s most underrated writing may be found in three novels that reflected her growing interest in — and suspicion of — America’s empire abroad. Set in the fictional Central American nation of Boca Grande, “A Book of Common Prayer” (1977) features both acid satire of corrupt U.S.-backed regimes and a tragic riff on the tale of Patty Hearst, as protagonist Charlotte Douglas searches for her daughter Marin, who is on the lam with a Marxist terrorist organization. Her interest in U.S. interference in the region and the absurdities of the late Cold War reappears in her final work of fiction, “The Last Thing He Wanted ” (1996), about a reporter and a government official who fall in love amid a secret arms-dealing operation reminiscent of Iran-Contra.

Entertainment & Arts

Photos: Joan Didion, masterful essayist, novelist and screenwriter, dies at 87

Photos from the life of Joan Didion, who chronicled California, politics and sorrow in ‘Slouching Towards Bethlehem’ and ‘Year of Magical Thinking.’

It is “Democracy” (1984), though, that gathers these personal and political themes into the most extraordinary whole, tracing a history of violence and exploitation from the colonization of Hawaii through the dawn of the atomic age to produce Didion’s answer to the Vietnam War novel. She even casts herself as narrator: “Democracy,” set in the early 1970s, is told from the perspective of “Joan Didion,” whose focused repetitions and circular logic as she attempts to piece together the tale of a U.S. senator, his wife and her lover presage those of her blockbuster memoir, “The Year of Magical Thinking” (2005).

The political commentary

Though most Joan Didion primers begin, as this one does, with the personal essays, my introduction to Didion — and one I recommend if you would like to become as obsessed with her writing as I am — came through “Democracy” and the essays in “Political Fictions” (2001). Beginning in the 1980s, when she forged a close working relationship with legendary New York Review of Books editor Robert Silvers, Didion shifted the focus of her reporting away from culture: She relayed searing descriptions of war-torn El Salvador in “Salvador” (1983), captured the the conspiratorial fever surrounding much of U.S.-Cuba politics in “Miami” (1987) and detailed the ways in which Sept. 11 became a jingoistic cudgel in “Fixed Ideas” (2003).

But for their exceedingly thorough and ultimately devastating authority, there may be no better place to go to understand our current political disaster, and the media’s role in it, than Didion’s dispatches from the presidential campaigns of 1988 (“Insider Baseball”) and 1992 (“Eyes on the Prize”), her exasperated reflections on the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal (“Clinton Agonistes”) or her poisonously funny takedown of Bob Woodward (“The Deferential Spirit,” 1996), author of books “in which measurable cerebral activity is virtually absent.”

She also applied the technique in the damning “Sentimental Journeys” (collected in 1992’s “After Henry ”), detailing the process by which politicians and the press railroaded the Central Park Five in the hothouse atmosphere of late-’80s New York.

The late memoirs

Despite a career in which she befriended celebrities like Natalie Wood and Tony Richardson — and employed Harrison Ford as a carpenter — Didion reached the height of her prominence with her bestselling memoir, “The Year of Magical Thinking, ” published in 2005. While she had experimented with the form two years prior in “Where I Was From,” it was her heartbreakingly lucid dissection of grief that captured the imagination of the broader public, earning her wide acclaim and the National Book Award. “Magical Thinking” recounts a year in Didion’s life in which she grappled with Dunne’s 2003 death from cardiac arrest and daughter Quintana Roo’s serious illness, combining her readings of Sigmund Freud and Emily Post with vivid memories from one of 20th century literature’s most intimate marriages. Her follow-up , “Blue Nights” (2011), which looked back on Quintana’s untimely death in 2005, offered a more caustic vision, searching her relationship with her daughter for moments she wrong-footed herself while revealing her own declining health. In the process she developed a late style all her own — incantatory and poetic but never (God forbid) sentimental.

More to Read

Cari Beauchamp, L.A. fixture and author who redefined women in Hollywood, dies at 74

Dec. 22, 2023

She created the Drag Queen Story Hour. Now she’s launching L.A.’s newest publisher

Dec. 18, 2023

So you want to retire and become a writer? Here’s some inspiration

Nov. 4, 2023

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Matt Brennan is a Los Angeles Times’ deputy editor for entertainment and arts. Born in the Boston area, educated at USC and an adoptive New Orleanian for nearly 10 years, he returned to Los Angeles in 2019 as the newsroom’s television editor. He previously served as TV editor at Paste Magazine, and his writing has also appeared in Indiewire, Slate, Deadspin and numerous other publications.

Boris Kachka is the former books editor of the Los Angeles Times and the author, most recently, of “Becoming a Producer.”

More From the Los Angeles Times

The week’s bestselling books, March 24

March 20, 2024

In ‘The Exvangelicals,’ Sarah McCammon tells the tale of losing her religion

Instead of writing about Princess Diana, Chris Bohjalian opted for her Vegas impersonator

March 19, 2024

50 years after Candy Darling’s death, Warhol superstar’s struggle as a trans actress still resonates

March 18, 2024

We earn a commission for products purchased through some links in this article.

Joan Didion: A guide to five of her most influential books

An overview of the Didion books you'll revisit for the rest of your days

Joan Didion inspired countless writers and readers to put pen to paper and write about the world as they see it. Her unique style, restrained yet honest, affecting yet never sentimental, is peerless. Famed for her incisive depictions of American life and personal journalism, she never wasted a word, nor a character. Her seminal essay for Vogue , On Self-Respect first published in 1961, was written not to a word count or a line count, but to an exact character count.

Didion's work chronicled the mood of the '60s, the highs and the lows, as well as the human experience in general - few writers have explored the subject of death and loss with as much insight, control or candour. Her skill lay not only in her style of prose, but her ability to astutely observe the behaviour of others. She saw what others missed.

Here, we celebrate five of her most influential books.

Slouching Towards Bethlehem, 1968

Although Slouching Towards Bethlehem wasn't Didion's first book ( Run, River of 1963 was), it was the one that cemented her as a prominent writer. A collection of essays about California in the '60s, her work explores the beauty and the ugliness of the decade, from the hippy community of San Francisco's Haight Ashbury to a woman accused of murdering her husband. Considered an essential portrait of American life in the '60s, Slouching Towards Bethlehem received positive attention as soon as it was published and its fandom has only grown over the decades since.

The White Album, 1979

Another collection of essays, The White Album deals with the late '60s to late '70s and the aftermath of the former. She studies the Women's Movement, shares her psychiatric report, parties with Janis Joplin and visits Linda Kasabian, who served as a lookout while members of the Manson family murdered Sharon Tate, in prison. These diverse essays see Didion capture the anxiety of the era and try to make sense of the Manson murders, the event many believe caused the '60s to end abruptly.

Where I Was From, 2003

Didion revisits the California she grew up in, specifically Sacramento County where she lived with her family, but also the state more generally. She questions the history she was taught, debunks Californian mythology and traces her ancestors and their journey moving west. She writes candidly about her upbringing, while exploring class issues with nuance. Where I Was From is one of Didion's lesser-known books, but shouldn't be.

The Year of Magical Thinking, 2005

Written in the aftermath of her husband's sudden death, The Year of Magical Thinking is an account of loss and grief - and the ways in which it can drive us to insanity. Hers was one of the first books to talk about bereavement beyond funerals, tracking the days and months that follow with her signature detachment. She writes about her own 'magical thinking' - how she can't bring herself to get rid of her husband's shoes because she thought he might need them when he returns. It sounds like pure misery, but Didion's deadpan tone impressively stops it from being so.

Blue Nights, 2011

Just a month before The Year of Magical Thinking was published, Didion's daughter, Quintana died of acute pancreatitis, aged 39. Blue Nights - a devastating account of her daughter's life and death - challenges how much tragedy one person can take. She laments over the passage of time and worries about growing older, lonelier. This is a heartbreaking tome, but solace for anyone who has ever faced the incomparable loss of losing a child.

Update your collection with these cookbooks

Inside the 'Barbie: The World Tour' book

Marisa Abela: Becoming Amy Winehouse

Inside Penelope Chilvers' Cotswolds cottage

Life Lessons with Léa Seydoux

'Ripley' is coming soon to Netflix

Kaya Scodelario: What you don't know about me

What you need to know about 'Palm Royale'

Meghan launches her own lifestyle brand

The luxury wool bedding to buy now

Dried flowers for a spring style refresh

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

The Deferential Spirit

September 19, 1996 issue

Submit a letter:

Email us [email protected]

The Agenda: Inside the Clinton White House

The Commanders

Veil: The Secret Wars of the CIA 1981-1987

Wired: The Short Life and Fast Times of John Belushi

The Brethren

On the morning of Sunday, June 23, the day the prepublication embargo on Bob Woodward’s The Choice was lifted, The Washington Post , the newspaper for which Mr. Woodward has so famously been, since 1971, first a reporter and now an editor, published on the front page of its A section two stories detailing what its editors believed most newsworthy in The Choice . In columns one through four, directly under the banner and carrying the legend The Choice—Inside the Clinton and Dole Campaigns , there appeared passages from the book itself, edited into a narrative describing the meetings Hillary Clinton had from 1994 to 1996 with Jean Houston, who was characterized in the Post as “a believer in spirits, mythic and other connections to history and other worlds” and as “the most dramatic” of Mrs. Clinton’s “10 to 11 confidants,” a group that includes her mother.

This account of Mrs. Clinton’s not entirely remarkable and in any case private conversations with Jean Houston appeared under the apparently accurate if unarresting headline “At a Difficult Time, First Lady Reaches Out, Looks Within,” occupied one-hundred-and-fifty-four column inches, was followed by a six-column-inch box explaining the rules under which Mr. Woodward conducted his interviews, and included among similar revelations the news that, according to an unidentified source (Mr. Woodward tells us that some of his interviews were on the record, others “conducted under journalistic ground rules of ‘background’ or ‘deep background,’ meaning the information could be used but the sources of the information would not be identified”), Mrs. Clinton had at an unspecified point in 1995 disclosed to Jean Houston (“Dialogue and quotations come from at least one participant, from memos or from contemporaneous notes or diaries of a participant in the discussion”) that “she was sure that good habits were the key to survival.”

The remaining front-page columns above the fold in that Sunday morning’s Post were given over to a news story based on Mr. Woodward’s The Choice , written by Dan Balz, running seventy-nine column inches, and headlined “Dole Seeks ‘a 10’ Among List of 15: Running Mate Must Not Anger Right, Book Says.” Mr. Woodward, according to this story, “quotes Dole as saying he wants a running mate who will be ‘a 10’ in the eyes of the public, with the candidate telling the head of his search team, Robert F. Ellsworth, ‘Don’t give me someone who would send up [anger] the conservatives.”‘ Those Post readers sufficiently surprised by this disclosure to continue reading learned that “at the top of the list of 15 names, assembled in the late spring by Ellsworth and Dole’s campaign manager, Scott Reed, was Colin L. Powell.” When I read this in the Post I assumed that I would find some discussion of how or whether the vice-presidential search team had managed to construe their number-one choice of Colin L. Powell as consistent with the mandate “Don’t give me someone who would send up the conservatives,” but there was no such discussion to be found, neither in the Post nor in The Choice itself.

Mr. Woodward’s rather eerie aversion to engaging the ramifications of what people say to him has been generally understood as an admirable quality, at best a mandarin modesty, at worst a kind of executive big-picture focus, the entirely justifiable oversight of someone with a more important game to play. Yet what we see in The Choice is something more than a matter of an occasional inconsistency left unexplored in the rush of the breaking story, a stray ball or two left unfielded in the heat of the opportunity, as Mr. Woodward describes his role, “to sit with many of the candidates and key players and ask about the questions of the day as the campaign unfolded.” What seems most remarkable in this new Woodward book is exactly what seemed remarkable in the previous Woodward books, each of which was presented as the insiders’ inside story and each of which went on to become a number-one bestseller: these are books in which measurable cerebral activity is virtually absent.

The author himself disclaims “the perspective of history.” His preferred approach has been one in which “issues could be examined before the possible outcome or meaning was at all clear or the possible consequences were weighed.” The refusal to consider meaning or outcome or consequence has, as a way of writing a book, a certain Zen purity, but tends toward a process in which no research method is so commonplace as to go unexplained (“The record will show how I was able to gain information from records or interviews…. I could then talk with other sources and return to most of them again and again as necessary”), no product of that research so predictable as to go unrecorded.

The world rendered is an Erewhon in which not only inductive reasoning but ordinary reliance on context clues appear to have vanished. Any reader who wonders what Vice-President Gore thinks about Whitewater can turn to page 418 of The Choice and find that he believes the matter “small and unfair,” but has sometimes been concerned that “the Republicans and the scandal machinery in Washington” could keep it front and center. Any reader unwilling to hazard a guess about what Dick Morris’s polling data told him about Medicare can turn to page 235 of The Choice and find that “voters liked Medicare, trusted it and felt it was the one federal program that worked.”

This tabula rasa typing requires rather persistent attention on the part of the reader, since its very presence on the page tends to an impression that significant and heretofore undisclosed information must have just been revealed, by a reporter who left no stone unturned to obtain it. The weekly lunch shared by the President and Vice-President Gore, we learn in The Choice , “sometimes did not start until 3 P.M. because of other business.” The President, “who had a notorious appetite, tried to eat lighter food.” The reader attuned to the conventions of narrative might be led by the presentation of these quotidian details into thinking that a dramatic moment is about to occur, but the crux of the four-page prologue having to do with the weekly lunches turns out to be this: the President, according to Mr. Woodward, “thought a lot of the criticism he received was unfair.” The Vice-President, he reveals, “had some advice. Clinton always had found excess reserve within himself. He would just have to find more, Gore said.”

What Mr. Woodward chooses to leave unrecorded, or what he apparently does not think to elicit, is in many ways more instructive than what he commits to paper. “The accounts I have compiled may, at times, be more comprehensive than what a future historian, who has to rely on a single memo, letter, or recollection of what happened, might be able to piece together,” he noted in the introduction to The Agenda , an account of certain events in the first years of the Clinton administration in which he endeavored, to cryogenic effect, “to give every key participant in these events an opportunity to offer his or her recollections and views.” The “future historian” who might be interested in piecing together the details of how the Clinton administration arrived at its program for health-care reform, however, will find, despite a promising page of index references, that none of the key participants interviewed for The Agenda apparently thought to discuss what might have seemed the central curiosity in that process, which was by what political miscalculation a plan initially meant to remove third-party profit from the health-care equation (or to “take on the insurance industry,” as Putting People First, the manifesto of the 1992 Clinton-Gore campaign, had phrased it) would become one distrusted by large numbers of Americans precisely because it seemed to enlarge and further entrench the role of the insurance industry.

This disinclination of Mr. Woodward’s to exert cognitive energy on what he is told reaches critical mass in The Choice , where not much said to the author by a candidate or potential candidate appears to have been deemed too casual for documentation (“Most of them permitted me to tape-record the interviews; otherwise I took detailed notes”), too insignificant for inclusion. President Clinton declined to be interviewed directly for this book, but Senator Dole “was interviewed for more than 12 hours and the typed transcripts run over 200 pages.” Accounts of these interviews, typically including date, time, venue, weather, and apparel details (for one Saturday interview in his office the candidate was “dressed casually in a handsome green wool shirt”), can be found, according to the index of The Choice (“Dole, Robert J. ‘Bob’, interviews by author with”), on pages 87-89, 183, 214-215, 338, 345-348, 378, 414, and 423.

Study of these pages suggests the deferential spirit of the enterprise. In the course of the Saturday interview for which Senator Dole selected the “handsome green wool shirt,” a ninety-minute session which took place on February 4, 1995, in Dole’s office in the Hart Senate Office Building (“My tape recorder sat on the arm of his chair, and his press secretary, Clarkson Hine, took copious notes”), Mr. Woodward asked if Dole, in 1988, thought he was the best candidate. He reports Dole’s answer: “Thought I was.” This gave Mr. Woodward the opportunity to ask what he had previously (and rather mystifyingly, since little else in The Choice tends to this point) defined for the reader as “an important question for my book”: “You weren’t elected,” he reminded Senator Dole, “so you have to come out of that period feeling the system doesn’t elect the best?”

Senator Dole, not unexpectedly, answered agreeably: “I think it’s true. I think Elizabeth raises that a lot, whether it’s president, or Senate or whatever, that a lot of the best—somebody people would describe [as] the best—don’t make it. That’s the way the system works. You also come out of that, even though you lose, if you still have enough confidence in yourself, that you didn’t lose because you weren’t the best candidate. You lost for other reasons. You can always rationalize these things.”

On Saturday, July 1, 1995, again in Dole’s Hart office (Senator Dole in “casual khaki pants, a blue dress shirt with cufflinks, and purple Nike tennis shoes”), Mr. Woodward elicited, in the course of a two-and-a-half-hour interview, these reflections from the candidate:

On his schedule : “We’re trying to pace ourselves. It’s like today I’m not traveling, which is hard to believe. Tomorrow we go to Iowa, get back at 1 A.M. We’re off all day Monday. Then we go to New Hampshire.” On his speechwriters : “You can’t just read something that somebody’s written and say ‘Oh, boy, this is dynamite.’ You’ve got to have a feel for it and you’ve got to think, Jimminy, this might work. And this is the message. And I think we’re still testing it, and I think you can’t say that if I said this on day one, it’s going to be written in stone forever.” On the message, in response to Mr. Woodward’s suggestion that “there’s something people are waiting for somebody to say that no one has said yet” : “Right. I think you’re right.” On his strategy : “As long as we’re on target, on message, and got money in the bank, and people are signing up, we’re mostly doing the right thing. But I also have been around long enough to know that somebody can make a mistake and it’ll be all over, too.” On the Senate : “Somebody has to manage it. And it may not be manageable. It isn’t, you know, it’s a frustrating place sometimes but generally it works out.”

“I was not out of questions,” Mr. Woodward concludes, “but I too was growing tired, and it seemed time to stand up and thank him.”

Mr. Woodward dutifully tries, in the note that prefaces The Choice , to provide the “why” paragraph, the “billboard,” the sentence or sentences that explain to the reader why the book was written and what it is about. That these are questions with which he experiences considerable discomfort seems clear:

Presidential elections are defining moments that go way beyond legislative programs or the role of the government. They are measuring points for the country that call forth a range of questions which each candidate must try to address. Who are we? What mat-ters? Where are we going? In the private and public actions of the candidates are embedded their best answers. Action is character, I believe, and when all is said and sifted, character is what matters most.

This quo vadis , or valedictory, mode is one in which Mr. Woodward has crashed repeatedly when faced with the question of what his books are about, as if his programming did not extend to this point. The “human story is the core” was his somewhat more perfunctory stab at explaining what he was up to in The Commanders . For Wired , his 1984 book about the life and death of the comic John Belushi, Mr. Woodward spoke to 217 people on the record and obtained access to “appointment calendars, diaries, telephone records, credit card receipts, medical records, handwritten notes, letters, photographs, newspaper and magazine articles, stacks of accountants’ records covering the last several years of Belushi’s life, daily movie production reports, contracts, hotel records, travel records, taxi receipts, limousine bills and Belushi’s monthly cash disbursement records,” only to arrive, not unlike HAL in 2001, at these questions: “Why? What happened? Who was responsible, if anyone? Could it have been different or better? Those were the questions raised by his family, friends and associates. Could success have been something other than a failure? The questions persist. Nonetheless, his best and most definitive legacy is his work. He made us laugh, and now he can make us think.”

In any real sense, these books are “about” nothing but the author’s own method, which is not, on the face of it, markedly different from other people’s. Mr. Woodward interviews people, he tapes or takes (“detailed”) notes on what they say. He takes “great care to compare and verify various sources’ accounts of the same events.” He obtains documents, he reads them, he files them: for The Brethren , the book he wrote with Scott Armstrong about the Supreme Court, the documents “filled eight file drawers.” He consults The Almanac of American Politics (“the bible, and I relied on it”), he reads what others have written on the subject: “In preparation for my own reporting,” he tells us about The Choice , “I and my assistant, Karen Alexander, read and often studied hundreds of newspaper and magazine articles.”

Should the information he requires lie outside Washington, he goes the extra mile: “I traveled from coast to coast many times, visiting everyone possible and everywhere possible,” he tells us about the research for Wired . Since Mr. Woodward lives in Washington and John Belushi worked in the motion picture industry and died at the Chateau Marmont in Los Angeles, these coast-to-coast trips might have seemed to represent the minimum in dogged fact-gathering, but never mind: the author had even then, in 1984, transcended method and entered the heady ether of methodology, a discipline in which the reason for writing a book could be the sheer fact of being there. “I would like to know more and Newsweek magazine was saying that maybe that is the thing I should look at next,” he allowed recently when a caller on Larry King Live asked if he might not want to write about Whitewater. “I don’t know. I do not know about Whitewater and what it really means. I am waiting—if I can say this—for the call from somebody on the inside saying ‘I want to talk.”‘

Here is where we reach the single unique element in the method, and also the problem. As any prosecutor and surely Mr. Woodward knows, the person on the inside who calls and says “I want to talk” is an informant, or snitch, and is generally looking to bargain a deal, to improve his or her own situation, to place the blame on someone else in return for being allowed to plead down or out certain charges. Because the story told by a criminal or civil informant is understood to be colored by self-interest, the informant knows that his or her testimony will be unrespected, even reviled, subjected to rigorous examination and often rejection.

The informant who talks to Mr. Woodward, on the other hand, knows that his or her testimony will be not only respected but burnished into the inside story, which is why so many people on the inside, notably those who consider themselves the professionals or managers of the process—assistant secretaries, deputy advisers, players of the game, aides who intend to survive past the tenure of the patron they are prepared to portray as hapless—do want to talk to him. Many Dole campaign aides did want to talk, for The Choice , about the herculean efforts and adroit strategy required to keep the candidate with whom they were saddled even marginally on target, on message, on the program:

Dole offered a number of additional references to the past, how it had been done before, and Reed [Dole campaign manager Scott Reed] countered with his own ideas about how he would handle similar situations. A sense of diffusion and randomness wouldn’t work. Making seat-of-the-pants, airborne decisions was not the way he operated…. Dole needed a coherent and understandable message on which to run, Reed said. Deep down, he added, he knew Dole knew what he wanted to say, but he probably needed some help putting it together and delivering it…. Reed felt he had hit the right weaknesses.

Similarly, many Clinton foreign policy advisers did want to talk, again for The Choice , about the equally herculean efforts and strategy required to guide the President, on the question of Bosnia, from one of his “celebrated rages” (“‘I’m getting creamed!”‘ Clinton, “unleashing his frustration” and “spewing forth profanity,” is reported to have said on being told of the fall of Srebrenica) to a more nuanced appreciation of the policy options on which his aides had been laboring unappreciated: “Berger [Deputy National Security Adviser Sandy Berger] reminded him that Lake [National Security Adviser Anthony Lake] was trying to develop an Endgame Strategy.” At a meeting a few days later in the Oval Office, when Vice-President Gore mentioned a photograph in The Washington Post of a refugee from Srebrenica who had hanged herself from a tree, the adroit guidance continued:

“My 21-year-old daughter asked about that picture,” Gore said. “What am I supposed to tell her? Why is this happening and we’re not doing anything?” It was a chilling moment. The vice president was directly confronting and criticizing the president. Gore believed he understood his role. He couldn’t push the president too far, but they had built a good relationship and he felt he had to play his card when he felt strongly. He couldn’t know precisely what going too far meant unless he occasionally did it. “My daughter is surprised the world is allowing this to happen,” Gore said carefully. “I am too.” Clinton said they were going to do something.

This is a cartoon, but not a cartoon in which anyone who spoke to the author will appear to have taken any but the highest ground. Asked, in the same appearance on Larry King Live , why he thought people talked to him, Mr. Woodward responded:

Only because I get good information and I talk to people at the middle level, lower level, try to talk to the people at the top. They know that I am going to reflect their point of view. One of my earlier books, somebody called me who was in it and said “How am I going to come out?” and I said “Well, essentially, I write self portraits.”…They really are self portraits, because I go to people and I say—I check them and I double check them but—but who are you? What are you doing? Where do you fit in? What did you say? What did you feel?

Those who talk to Mr. Woodward, in other words, can be confident that he will be civil (“I too was growing tired, and it seemed time to stand up and thank him”), that he will not feel impelled to make connections between what he is told and what is already known, that he will treat even the most patently self-serving account as if untainted by hindsight (that of Richard Darman, say, who in 1992 presented himself to Mr. Woodward, who in turn presented him to America, as the helpless Cassandra of the 1990 Bush budget deal * ); that he will be, above all, and herein can be found both Mr. Woodward’s compass and the means by which he is set adrift, “fair.”

I once heard a group of reporters agree that there were at most twenty people who run any story. What they meant by “running the story” was setting the terms, setting the pace, deciding the agenda, determining when and where the story exists, and shaping what the story will be. There were certain people who ran the story in Vietnam, there were certain people in Central America, there were certain people in Washington. An American presidential campaign is a Washington story, which means that the handful of people who run the story in Washington—the people who write the most influential columns, the people who conduct the Sunday shows on which Washington talks to itself—will also run the campaign. Bob Woodward, who is unusual in that he is not a regular participant in the television dialogue and appears in print, outside his books, only infrequently, is one of the people who run the story in Washington.

In this business of running the story, in fact in the business of news itself, certain conventions are seen as beyond debate. “Opinion” will be so labeled, and confined to the op-ed page or the Sunday-morning shows. “News analysis” will be so labeled, and will appear in a subordinate position to the “news” story it accompanies. In the rest of the paper as on the evening news, the story will be reported “impartially,” the story will be “even-handed,” the story will be “fair.” “Fairness” is a quality Mr. Woodward particularly seems to prize (“I learned a long time ago,” he told Larry King, “you take your opinions and your attitudes, your predispositions—get them in your back pocket, because they are only going to get in the way of doing your job”), and mentions repeatedly in his thanks to his assistants.

It was “Karen Alexander, a 1993 graduate of Yale University,” who “brought unmatched intellect, grace and doggedness and an ingrained sense of fairness” to The Choice . On The Agenda , it was “David Greenberg, a 1990 graduate of Yale University,” who “repeatedly worked to bring greater balance, fairness, and clarity to our reporting and writing.” It was “Marc E. Solomon, a 1989 Yale graduate,” who “brought a sense of fairness and balance” to The Commanders. On The Veil, it was “Barbara Feinman, a 1982 graduate of the University of California at Berkeley,” whose “friendship and sense of fairness guided the daily enterprise.” For The Brethren, Mr. Woodward and his co-author, Scott Armstrong, thank “Al Kamen, a former reporter for the Rocky Mountain News ,” for his “thoroughness, skepticism, and sense of fairness.”

The genuflection toward “fairness” is a familiar newsroom piety, the excuse in practice for a good deal of autopilot reporting and lazy thinking but a benign ideal. In Washington, however, a community in which the management of news has become the single overriding preoccupation of the core industry, what “fairness” has too often come to mean is a scrupulous passivity, an agreement to cover the story not as it is occurring but as it is presented, which is to say as it is manufactured. Such institutionalized events as a congressional hearing or a presidential trip will be covered with due diligence, but the story will vanish the moment the gavel falls, the hour Air Force One returns to Andrews.

“Iran-contra” referred exclusively, for many Washington reporters, to the hearings. The sequence of events that came to be known as “the S&L crisis,” which was actually less a “crisis” than the structural malfunction that triggered what remains an uncontrolled meltdown in middle-class confidence, existed as a “story” only on those occasions (hearings, indictments) when it showed promise of rising to its “crisis” slug. Similarly, “Whitewater” (as in “I do not know about Whitewater and what it really means”) has survived as a story only to the extent that it allows those who cover it to note the waning or waxing probability of a “smoking gun,” or “evidence.”

“If there is evidence it should be pursued,” Mr. Woodward told Larry King to this point. “In fairness to the Clintons. And it’s—it—you know, we all in the news business, and in politics have to be very sensitive to the unfair smear…. It’s not fair and again it goes back to what’s the evidence?” Yet the actual interest of Whitewater lies in what has already been documented: it is “about” the S&L crisis, and thereby offers a detailed and specific look at the kinds of political and financial dealing that resulted in the meltdown in middle-class confidence. What Whitewater “really means” or offers, then, is an understanding of that meltdown, which is now being reported as an inexplicable phenomenon weirdly detached from the periodic “growth” figures produced in Washington; but this is not a story that will be put together by waiting for the call from somebody on the inside saying “I want to talk.”

Every reporter, in the development of a story, depends on and coddles, or protects, his or her sources. Only when the protection of the source gets in the way of telling the story does the reporter face a professional, even a moral, choice: he can blow the source and move to another beat or he can roll over, shape the story to continue serving the source. The necessity for making this choice between the source and the story seems not to have come up in the course of writing Mr. Woodward’s books, for good reason: since he proceeds from a position in which the very impulse to sort through the evidence and reach a conclusion is seen as suspect, something to be avoided in the higher interest of fairness, he has been able, consistently and conveniently, to define the story as that which the source tells him.

This fidelity to the source, whoever the source might be, leads Mr. Woodward down avenues that might at first seem dead-end: On page 16 of The Choice we have President Clinton, presumably on the authority of a White House source, “thunderstruck” that Senator Dole, on the morning after Clinton’s mother died in early 1994, should have described Whitewater on the network news shows as “unbelievable,” “mind-boggling,” “big, big news” that “cries out more than ever now for an independent counsel.” On page 346 of The Choice we have Senator Dole, on December 27, 1995, telling Mr. Woodward “that he had never used Whitewater to attack the president personally,” to which Mr. Woodward responds only: “What would be your criteria for picking a vice president?” On page 423 of The Choice we have Mr. Woodward, on April 20, 1996, by which date he had apparently remembered what he said on page 16 that Senator Dole said, although not what he said on page 346 that Senator Dole said, advising Senator Dole that the President had resented his “aggressive call for a Whitewater independent counsel back in early 1994, the day Clinton’s mother had died.”

Only now do we arrive at what seems to be for Mr. Woodward the point, and it has to do with his own role as honest broker, or conscience to the candidates. He reports that Senator Dole was “troubled” by this disclosure, even “haunted by what he might have done,” so much so that he was moved to write Clinton a letter of apology:

Later that week, Dole was at the White House for an anti-terrorism bill signing ceremony. Clinton took him aside into a corridor so they could speak alone. The president thanked him for the letter. He said he had read it twice. He was touched and appreciated it very much. “Mothers are important,” Dole said. Emotion rose up in both men. They looked at each other for an instant, then moved back to business. Soon they agreed on a budget for the rest of the year. It was not the comprehensive seven-year deal both had envisioned and worked on for months. But it was a start.

The human story is the core,” as Mr. Woodward said of The Commanders . To believe that this moment in the White House corridor occurred is not difficult: we know it occurred, precisely because whether or not it occurred makes no difference, has no significance, appears at first to tell us, like the famous moment described in Veil , the exchange between the author and William Casey in Room C6316 at Georgetown Hospital, nothing. “You knew, didn’t you,” Mr. Woodward thought to ask Casey on that occasion.

The contra diversion had to be the first question: you knew all along. His head jerked up hard. He stared, and finally nodded yes. Why? I asked. “I believed.” What? “I believed.” Then he was asleep, and I didn’t get to ask another question.

This account provoked, in the immediate wake of Veil ’s 1987 publication, considerable talk-show and dinner-table controversy (was Mr. Woodward actually in the room, did Mr. Casey actually nod, where were the nurses, what happened to the CIA security detail), including, rather astonishingly, spirited discussion of whether or not the hospital visit could be “corroborated.” In fact there was so markedly little reason to think the account inauthentic that the very question seemed to obscure, as the account itself had seemed to obscure, the actual problem with the scene in Room C6316 at Georgetown Hospital, which had to do with timing, or with what did Mr. Woodward know and when did he know it.

The hospital visit took place, according to Veil , “several days” after Mr. Casey’s resignation, which occurred on January 29, 1987. This was almost four months after the crash of the Hasenfus plane in Nicaragua, more than two months after the Justice Department disclosure that the United States had been selling arms to Iran in order to divert the profits to the contras, and a full month after both the House and Senate Permanent Select Committees on Intelligence had completed reports on their investigations into the diversion. The inquiries of the two congressional investigating committees established in the first week of January 1987, the Senate Select Committee on Secret Military Assistance to Iran and the Nicaraguan Opposition and the House Select Committee to Investigate Covert Arms Transactions with Iran, were already underway. The report of the Tower commission would be released in three weeks.

Against this background and this amount of accumulated information, the question of whether the Director of Central Intelligence “knew” about the diversion was, at the time Mr. Woodward made his hospital visit and even more conclusively at the time he committed his account of the visit to paper, no longer at issue, no longer relevant, no longer a question. The hospital interview, then, exists on the page only as a prurient distraction from the real questions raised by the diversion, only as a dramatization of the preferred Washington view that Iran-contra reflected not a structural problem but a “human story,” a tale of how one man’s hubris could have shaken the basically solid foundations of the established order, a disruption of the solid status quo that will be seen to end, satisfyingly, with that man’s death.

Washington, as rendered by Mr. Woodward, is by definition basically solid, a diorama of decent intentions in which wise if misunderstood and occasionally misled stewards will reliably prevail. Its military chiefs will be pictured, as Colin Powell was in The Commanders , thinking on the eve of war exclusively of their troops, the “kids,” the “teenagers”: a human story. The clerks of its Supreme Court will be pictured, as the clerks of the Burger court were in The Brethren , offering astute guidance as their justices negotiate the shoals of ideological error: a human story. The more available members of its foreign diplomatic corps will be pictured, as Saudi ambassador Prince Bandar bin Sultan was in The Commanders and in Veil , gaining access to the councils of power not just because they have the oil but because of their “backslapping irreverence,” their “directness,” their exemplification of “the new breed of ambassador—activist, charming, profane”: yet another human story. Its opposing leaders will be pictured, as President Clinton and Senator Dole are in The Choice , finding common ground on the importance of mothers: the ultimate human story.

That this crude personalization works to narrow the focus, to circumscribe the range of possible discussion or speculation, is, for the people who find it useful to talk to Mr. Woodward, its point. What they have in Mr. Woodward is a widely trusted reporter, even an American icon, who can be relied upon to present a Washington in which problematic or questionable matters will be definitively resolved by the discovery, or by the demonstration that there has been no discovery, of “the smoking gun,” “the evidence.” Should such narrowly-defined “evidence” be found, he can then be relied upon to demonstrate, “fairly,” that the only fingerprints on the smoking gun are those of the one bad apple in the barrel, the single rogue agent in the tapestry of decent intentions.

“I kept coming back to the question of personal responsibility, Casey’s responsibility,” Mr. Woodward reports having mused (apparently for once ready, at the moment when he is about to visit a source on his deathbed, to question the veracity of what he has been told) before his last visit to Room C6316 at Georgetown Hospital. “For a moment, I hoped he would take himself off the hook. The only way was an admission of some kind or an apology to his colleagues or an expression of new understanding. Under the last question on ‘Key unanswered questions for Casey,’ I wrote: ‘Do you see now that it was wrong?”‘ To commit such Rosebud moments to paper is what it means to tell “the human story” at “the core,” and it is also what it means to write political pornography.

September 19, 1996

Subscribe to our Newsletters

More by Joan Didion

Nineteen writers remember The New York Review ’s editor.

May 11, 2017 issue

On covering the Patty Hearst trial in San Francisco, 1976

May 26, 2016 issue

August 15, 2013 issue

Joan Didion (1934–2021) was the author, most recently, of Blue Nights and The Year of Magical Thinking , among seven other works of nonfiction. Her five novels include A Book of Common Prayer and Democracy .

The Washington Post : “Origin of the Tax Pledge,” by Bob Woodward (October 4, 1992, p. A1), “No-Tax Vow Scuttled Anti-Deficit Mission,” by Bob Woodward (October 5, 1992, p. A1), “Primary Heat Turned Deal into a ‘Mistake,”‘ by Bob Woodward (October 6, 1992, p. A1), and “The President’s Key Men: Splintered Trio, Splintered Policy,” by Bob Woodward (October 7, 1992, p. A1). ↩

The Fate of the Union: Kennedy and After

December 26, 1963 issue

A Double Standard

April 9, 1992 issue

Casey and Woodward: Who Used Whom?

November 5, 1987 issue

An Illegal War

October 21, 2004 issue

The Report of Captain Secher