- Open access

- Published: 19 May 2020

The mediating effect of social support on uncertainty in illness and quality of life of female cancer survivors: a cross-sectional study

- Insook Lee ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6090-7999 1 &

- Changseung Park 2

Health and Quality of Life Outcomes volume 18 , Article number: 143 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

2934 Accesses

19 Citations

Metrics details

Cancer survivors have been defined as those living more than 5 years after cancer treatment with no signs of recurrence or further growth; however, the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship of the United States defined cancer survivors as those undergoing treatment after being diagnosed with cancer or those considered to be fully cured. The National Cancer Institute of the United States established the Office of Cancer Survivorship, with the American Society of Clinical Oncology including “patient and survivor management” as its 2006 annual objective [ 1 ], indicating the importance of cancer survivor management as a major agenda item.

Typically, breast and thyroid cancer diagnoses occur among women in their 40s and 50s, and patients who receive treatment have high survival rates. The majority of breast and thyroid cancer survivors return to their daily lives within a relatively short timeframe [ 2 ], making quality of life after treatment and important factor in cancer treatment [ 3 , 4 , 5 ].

Cancer survivors have reported experiencing a variety of physical difficulties during or after treatment, including fatigue, pain, loss of energy, sleeping disorders, and constipation [ 6 , 7 ]. They also have psychological concerns, such as fear of the cancer spreading, concerns about treatment results, and uncertainty about the future [ 8 ], as well as financial difficulties, issues with their sex lives, decreased body image, difficulties in interpersonal relationships, role disorders, and difficulty returning to work [ 7 ]. Thus, cancer patients require a diverse range of healthcare services, plus emotional and socioeconomic support, with an international study of the quality of life and symptoms of cancer survivors reporting that the quality of life among Asian patients to be the lowest of those than other country [ 6 ]. Survivors of breast cancer have reported low quality of life after treatment [ 9 , 10 ], which is influenced by emotional and psychological factors such as uncertainty, body image, lack of self-respect, and depression [ 9 , 10 , 11 ], as well as social factors including social, family, and spouse support [ 10 , 11 ].

Uncertainty among women diagnosed with malignant illnesses was found to be higher than that among women with a lump in the breast [ 12 ]. Uncertainty among breast cancer patients continues for a long period because of the fear of recurrence [ 13 ] and reduced quality of life [ 11 ]. Similarly, thyroid cancer survivors also show higher levels of fatigue, depression, and anxiety compared to those with no experience of cancer [ 14 , 15 , 16 ].

Social support is a complex and multidimensional concept that is characterized by mutual benefits that include social, psychological, and material support provided by the social support network [ 17 ]. In other words, social support means help provided by social relationships such as family, friends, and significant others, and plays an important role in directly and indirectly reducing uncertainty [ 18 , 19 ]. For cancer survivors, the need for social support is varied and depends largely on the adaptive tasks they face [ 20 ]. Social support is closely related to breast cancer survivor prognosis [ 21 ]; breast cancer survivors’ uncertainty was found to lower their quality of life, but their recognition of social support was found to improve it [ 11 ]. Recognition of social support and uncertainty played a key role in managing and maintaining quality of life. Research has shown that social support differs according to survival stage, as patients who are undergoing treatment receive active support from healthcare professionals and their family, but this support declines notably after the treatment ends [ 14 , 22 , 23 ].

With the number of cancer survivors steadily increasing, there has been an increase in the number of studies published on cancer survivors internationally [ 22 , 24 ]. In Korea in particular, there have been studies on recurrence-prevention behaviors and quality of life [ 25 ], the factors influencing quality of life [ 10 ], fatigue and quality of life [ 26 ], distress and quality of life [ 27 ], and symptoms and quality of life among breast cancer survivors [ 8 ]. Most of these studies focused on breast cancer survivors, but few studies focus on overall quality of life and the related influential factors. Few studies have analyzed the relationships between uncertainty in illness, quality of life, and social support among female breast and thyroid cancer survivors.

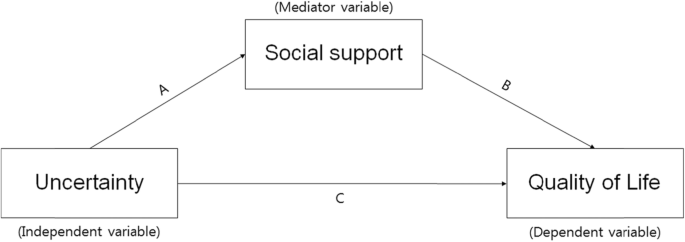

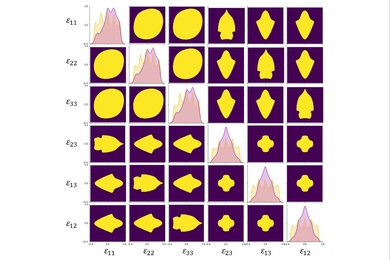

This study aimed to identify the relationships among uncertainty in illness, social support, and quality of life in female cancer survivors, and to verify the mediating role of social support, in the relationship between uncertainty in illness and quality of life. Social support may act as a generative mechanism influencing how uncertainty in illness, the predictor variable, affects quality of life, the outcome variable (Fig. 1 ) [ 28 ]. Therefore, this study will provide foundational data for devising practical and helpful intervention strategies to raise the quality of life of cancer survivors.

The theoretical research model showing the influence of uncertainty on quality of life and the mediating effect of social support

Participants

Participants were selected using convenience sampling of female cancer patients who were being treated by specialists in breast endocrinology at general hospitals located in J City of Korea. Among the 189 women (138 thyroid and 50 breast cancer patients) who agreed to participate, 156 surveys were collected (response rate: 82.5%). The final sample including 148 participants after excluding eight insincere responses. The data collection period was from April 21 to June 30, 2014. The completion of data collection through the mailed-in copies of surveys occurred on October 15, 2014. Participants were asked to complete the survey, put it in an opaque envelope, and seal it before returning it to the researchers. In cases in which on-site survey completion was difficult, participants were able to complete the survey at home and returned it by mail to the researcher.

The necessary sample size for the multiple regression analysis was confirmed utilizing G*power ver. 3.1.9 with a significance level (α) of .05; power of .80; effect size (f 2 ) of .15 (representing a medium effect size in the multiple regression analysis); and 13 independent variables (age, marital status, religion, level of education, occupation, satisfaction with economic status, smoking, drinking, diagnosis name, clinical stage of cancer, time passed since the end of treatment, uncertainty, and social support). The minimum sample size was determined to be 131. Since a maximum dropout rate of 40% was expected, information was collected from a total of 189 participants who fit the following inclusion criteria: 1) a diagnosis of cancer and no cognitive limitations; 2) the ability to understand and complete the survey in Korean; and 3) an understanding of the purpose of the study and consenting to participate. The exclusion criteria were those suffering from a mental illness, those with difficulties in communication, and those who did not wish to participate in the study.

Uncertainty in illness

Uncertainty occurs when an appropriate subjective interpretation of an illness or event is not formed. This study measured uncertainty using Mishel’s Uncertainty in Illness Scale (MUIS), which is composed of 33 items concerning uncertainty in illness. Mishel [ 19 ] originally developed the scale, and it has been translated into Korean by Lee [ 28 ]. The MUIS is a self-administered survey, with items scored on a 5-point scale from 5 ( strongly agree ) to 1 ( strongly disagree ). Positive items were measured backward, so that total scores ranged from 33 to 165. Higher scores indicated higher rates of uncertainty. The Cronbach’s α for the original 33-item tool was .91–.93; the Cronbach’s α for the tool used in the study of Korean breast cancer patients [ 29 ] was .83. In this study, the Cronbach’s α for the uncertainty scale was .88.

Social support

Social support was measured using Zimet et al.’s [ 30 ] Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS). This 12-item measure is scored on a 7-point, Likert-type scale, and assessed the three dimensions of family, friends, and significant others. Its sub-domains are composed of four items. Overall social support scores are calculated by summing the scores for each item, with higher scores indicating higher levels of social support. At the time of development, the Cronbach’s α reliability was .91; Cronbach’s α for each subscale ranged from .90–.95. In this study, the Cronbach’s α of the social support scale was .95.

Quality of life

Quality of life was measured using a standardized tool that was translated into the Korean and verified validity of the Korean version of the EORTC QLQ-C30, which was developed through a process of international joint study from multiple countries, and it is the most widely used standardized tool to measure the quality of life of cancer patients. This tool is composed of three subdomains and 30 items. It includes two items on overall quality of life and five functional domains (i.e., physical, role, cognitive, emotional, and social functions) that include 15 items; three symptom domains (i.e., fatigue, pain, nausea/vomiting) that include seven items; and one item for each of the symptoms commonly reported by cancer patients (i.e., difficulties in breathing, loss of appetite, sleeping disorders, constipation, diarrhea, and financial hardship) [ 31 ]. The EORTC QLQ-C30 is converted into a score ranging between 0 and 100 points [ 31 ]; higher overall quality of life scores, higher functional domain scores, and lower symptom domain scores indicate higher quality of life. Moreover, overall quality of life can be understood as a measurement of comprehensive quality of life [ 31 ]. This study assess quality of life using the overall quality of life score. At the time of development, Cronbach’s α was .65–.73; the Cronbach’s α for the overall quality of life score in this study was .853.

Ethical considerations

This study was conducted after receiving approval of the research protocol from the Institutional Review Board (Approved number: 2014-L02–01). The purpose and method of the research was explained directly to participants by a trained research assistant. The participants then signed an informed consent form that stated the survey would be used for the purposes of the study only, and that their confidentiality would be safeguarded. The subjects who agreed to participate in the survey received a small amount of goods worth of KRW 3000, but there were no factors that could interfere with the answers in the survey.

Data analysis

The collected data were coded and analyzed using SPSS software (version 24.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) at .05 significance level. The analysis excluded missing data values. The general characteristics, illness-related characteristics, uncertainty, social support, and quality of life were measured using frequency, percentages, means, and standard deviations. The differences in uncertainty, social support, and quality of life in accordance with general and illness-related characteristics were analyzed using independent t -tests and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Tukey’s post-hoc analysis was used for independent variables of more than three groups to identify which group contained the differences. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was calculated to identify correlations between uncertainty, social support, and quality of life. Multiple regression (stepwise method) was used to test the influence of uncertainty on social support and quality of life. To verify the mediating effects of social support in the relationship between uncertainty and quality of life, simple, and hierarchical multiple regression analyses were conducted as per the method proposed by Baron and Kenny [ 30 ]. The significance of the mediating effects of social support was verified using the Sobel test.

Demographic characteristics of subjects

The general characteristics of the female cancer survivors in this study indicated that their average age was 51.87 ( SD = 11.78) years, with the largest proportion (33.3%) of the population being in their 50s, followed by those in their 40s (30.1%), 60s and over (24.4%), and below 30 (12.2%). Most participants (76.2%) were married; 61.9% practiced a religion, and 66.7% had a high school education or below; 56.2% had jobs; 17.8% had lost their jobs as a result of their cancer diagnosis and treatment, and 73.1% indicated that their satisfaction with their financial status was average. They had an average of 2.26 ( SD = 1.19) children; 94.4% were non-smokers; 64.1% were non-drinkers; 29.1% of the subjects had breast cancer and 70.9% had thyroid cancer; 53.8% of the cancers were early stage, and 46.2% were advanced. The duration after cancer treatment averaged 17.64 ( SD = 31.30) months, with 70.3% reporting a duration of less than a year since they ended their treatment (Table 1 ).

Uncertainty in illness, social support, and quality of life

Average scores of uncertainty in illness, social support, and quality of life are given in Table 2 . The average uncertainty in illness score was 83.06 ( SD = 15.29; range: 44–127 points), and the average quality of life score was 66.90 ( SD = 20.32; range: 0–100 points). Average social support score was 62.62 ( SD = 17.09; range: 12–84 points), with family support being the highest (mean = 21.84, SD = 6.58), followed by support from significant others (mean = 21.28, SD = 5.93) and friends (mean = 19.45, SD = 6.70).

Differences in uncertainty in illness, social support, and quality of life according to general and illness-related characteristics

The results of the analysis of differences in uncertainty in illness, social support, and quality of life according to general and illness-related characteristics are given in Tables 3 and 4 . There were significant differences in uncertainty in illness by educational level ( t = 4.048, p < .001), satisfaction with financial status ( F = 3.760, p = .027), and smoking ( t = 2.195, p = .030). Uncertainty in illness was higher for subjects with less than a high school education, compared to those who had a university degree or higher, when they were dissatisfied with their financial status. Likewise, it was higher for smokers, compared to non-smokers.

Social support had statistically significant differences given satisfaction with financial status ( F = 5.151, p = .007) and duration since cancer treatment completion ( F = 4.292, p = .015). Social support was higher for subjects with average financial status satisfaction, and for subjects for whom it had been less than a year, or between 1 to 5 years, since they completed cancer treatment.

Quality of life significantly differed according to financial status satisfaction ( F = 6.648, p = .002). Participants had higher quality of life when they had high or average financial status satisfaction compared to dissatisfaction.

Correlation between uncertainty in illness, social support, and quality of life

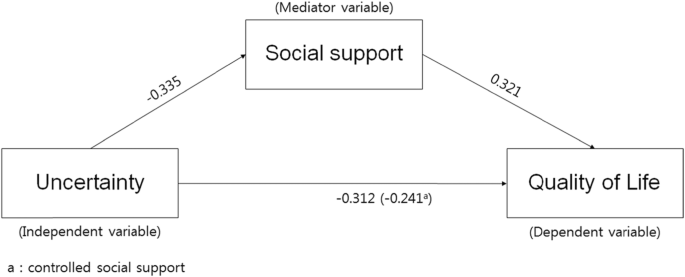

The results of the correlation analyses indicated that uncertainty in illness had a significant negative correlation with social support ( r = −.335, p < .001) and quality of life ( r = −.312, p < .001); social support had a significant positive correlation with quality of life ( r = .321, p < .001). Correlations between the sub-factors of social support and quality of life indicate that there were significant positive correlations between quality of life and support from significant others ( r = .315, p < .001), friends ( r = .284, p = .001), and family ( r = .265, p = .001). Uncertainty and support from significant others ( r = −.326, p = .001), friends ( r = −.294, p = .002), and family ( r = −.244, p = .010) showed significant negative correlations; particularly, the highest correlation was between support from significant others and uncertainty (Table 5 ).

Mediating effect of social support

Four stages of regression analysis were conducted to verify whether social support had mediating effects in the process by which uncertainty in illness influenced quality of life. Prior to verifying the mediating effects of social support, this study examined the multicollinearity between variables. The residual limit was between 0.8–1.0, which is higher than 0.1; and the value of the variance inflation factor was between 1.0–1.2, which was lower than 10, indicating no issues with multicollinearity. Moreover, the Durbin-Watson test, which is the test of independence of residual error, indicated d = 1.903–1.944, which was close to two and met the independence condition, representing no issues with self-correlation.

Using the hierarchy regression, this confirmed the partial mediating effects of social support in the process of uncertainty influencing quality of life (Table 6 , Fig. 2 ). The first regression analysis indicated that the independent variable (uncertainty) had a statistically significant influence on the mediator variable (social support; β = − 0.335, p < .001), and the explanatory power for social support was 10.4%. The second stage regression analysis indicated that the mediator variable (social support) had a significant influence on the dependent variable (quality of life; β = 0.321, p < .001), and the explanatory power for quality of life was 9.7%. The third stage regression analysis indicated that the independent variable (uncertainty) had a significant influence on the dependent variable (quality of life; β = − 0.312, p = .001) with an explanatory power of 8.9%. At the fourth stage, this study aimed to test the influence of the independent variable (uncertainty) on the dependent variable (quality of life) with social support as the mediator variable. The results indicated that uncertainty (β = − 0.241, p = .014) and social support (β = 0.213, p = .030) were significant predictors of quality of life. When social support was set as the mediator variable, uncertainty was found to have a significant influence on quality of life; the unstandardized regression coefficient reduced from − 0.396 to − 0.398, indicating a partial mediation of social support. The explanatory power of these variables in terms of quality of life was 12.1%. This study executed the Sobel test to verify the significance of the mediating effects of social support, confirming that they were significant in the relationship between uncertainty and quality of life.

Model showing the influence of uncertainty on quality of life and the mediating effect of social support

Mullen divided the stages of cancer survival into three major classifications [ 32 , 33 ]. First is the acute stage, which marks the period after the cancer diagnosis. Second is the extended stage, in which the active treatment of cancer has ended and the patient is placed under tracking observation or engages in intermittent treatment. During this period, the majority of cancer survivors experience uncertainty toward their cancer treatment and fear recurrence, and they may experience physical and psychological issues. Lastly, the permanent stage marks a period in which the cancer is thought to be fully cured, or the patient is expected to survive long term, with a low risk of recurrence.

The participants in this study averaged a score of 66.90 for quality of life. As it is difficult to draw a direct comparison given the lack of research utilizing this measure, in converting quality of life into a scale of 100 points, this study’s results were similar to those found previously regarding post-hoc management following breast cancer treatment for 200 women [ 8 , 10 ]. However, a study covering regionally based, adult female breast cancer survivors between 6 months and 2 years after anti-cancer treatment completion reported lower scores (e.g., 60.13 points) compared to this study [ 27 ]. Likewise, a study of breast cancer survivors with completed surgeries and assistive treatments, breast cancer survivors whose treatment had ended had scores of 53.4 and 56.66 points, respectively for breast cancer survivors with completed surgeries and assistive treatments [ 25 , 26 ].

On the other hand, a report of 110 adult females with breast cancer or OB/GYN cancers [ 33 ] indicated that quality of life according to cancer survival stage was 58.7, 62.3, and 66.8 points during the acute, extended, and permanent stages, respectively. Quality of life in this study was similar to the level experienced by survivors during the permanent stage. Considering that the average time since treatment was 17.64 months, these results indicate a relatively high quality of life. While these differences cannot be accurately compared and discussed because of the lack of research covering the same variables, the majority of survivors had thyroid cancer (70.9%), and it is known that thyroid cancer has higher rates of survival. Going forward, it is important to develop interventions to improve quality of life by assessing survivors’ specific stages.

There were no significant relationships between quality of life and length of time since completing treatment. Existing research has suggested that quality of life was significantly higher for those surviving more than 5 years after cancer treatment completion [ 8 , 33 ], indicating that quality of life improves as duration of survival increases. The quality of life of these cancer survivors has been reported to improve with the passage of time [ 8 , 33 ]. Therefore, cross-sectional and longitudinal studies are required in the future to identify quality of life by survival stage and changes in quality of life over time.

On the other hand, qualitative studies of Korean female cancer survivors have indicated that the significant others and families of female cancer survivors wanted them to return to their pre-cancer lives to take care of their spouses and children, indicated the demands on female cancer survivors in Korea to fulfill their roles as wives and mothers before fully recovering from cancer [ 33 ]. Thus, customized interventions by survival stage for female cancer survivors are needed along with further research on the relationships between cultural specificity, role conflicts imposed on survivors because they are women, and their quality of life.

The uncertainty toward illness of the participants in this study was similar to existing research in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy averaged 83.08 [ 34 ] and female thyroid cancer patients [ 35 ]. On the other hand, the level of uncertainty faced by cancer patients prior to surgery averaged 81.43 in a study of cancer patients hospitalized for breast, thyroid, and bladder cancer [ 36 ], which was slightly lower than the value found in this study. This appears to be because female cancer survivors in this study were mostly in the extended stage, which comes after the active treatment of their cancer [ 32 , 33 ]. Most cancer survivors face uncertainty toward cancer treatment and fear of recurrence [ 8 , 32 , 33 ]; thus, they experience a diverse range of physical and psychological problems [ 6 , 7 ]. On the other hand, a qualitative study of 25 breast cancer survivors aged over 30 who had undergone surgery and chemotherapy as their primary treatment for breast cancer [ 37 ] indicated that quality of life following treatment for breast cancer survivors saw a coexistence of anxiety and uncertainty about recurrence. A shorter duration of time since treatment led to higher confusion in their own health management efforts and health management in general.

These results indicate that there are limitations to comparing uncertainty results given the lack of domestic studies on cancer survivors; therefore, future studies are needed to fill this gap. Moreover, it is necessary to confirm uncertainty by cancer survival stage and develop interventions to reduce the uncertainty accompanying each stage.

Uncertainty in illness was higher for those with less than a high school education, compared to those with a university education or higher, when they were dissatisfied with their financial status, and for those who were smokers. These results were similar to previous research [ 36 ], which indicated high uncertainty for participants over 60 who had a low monthly income and low level of education. Therefore, it is necessary to consider these socioeconomic factors when developing uncertainty reducing strategies such as customized information delivery and communication.

The social support of female cancer survivors in this study was rather high, at 62.62 out of 84 points; family support was the highest, followed by support from significant others, and finally friends. Social support is known to play an important role in helping individuals reduce their levels of uncertainty [ 37 ]. Particularly, in Korea, family and healthcare professional support have been the most important support resources among all social support types [ 34 ]. The results of this study indicated that family support was the highest, which was in line with the results of existing studies. On the other hand, a qualitative study of 25 breast cancer survivors aged over 30 who had undergone surgery and chemotherapy as their primary breast cancer treatments [ 37 ] indicated that positive support and responses from family, patients with similar illnesses, and those surrounding them helped to strengthen positive self-suggestion, which also helped them to overcome their illnesses. Other studies have reported that patients undergoing treatment receive active support from healthcare professionals and their family, but they receive less support and interest from healthcare professionals, their family, and those surrounding them after the treatment ends [ 22 , 23 , 27 ]. Therefore, it is necessary to take a continuous interest in and facilitate social support for cancer survivors.

Social support was higher for participants with average satisfaction toward their financial status, and for those for whom less than a year, or between 1 and 5 years, had passed since the completion of their cancer treatment, compared to those for whom 5 years or more had passed since treatment. These results were similar to those of studies on cancer patients hospitalized for breast, thyroid, and bladder cancer surgery [ 36 ], which indicated social support differed according to the time that had passed since diagnosis. Moreover, these results are similar to those reporting that breast cancer survivors are required by their spouses or family to fulfill roles they had filled prior to their cancer diagnosis, and this was associated with decreasing support from family [ 38 ]. These results indicate that female cancer survivors require ongoing psychosocial support as well as education and access to information as they live out their lives.

According to Baik and Lim [ 20 ], who studied social support according to different stages of breast and gynecological cancer survival, the social support of patients in the acute stage was comparatively higher, but there were no significant differences in social support across the different stages, which was different from the findings of this study. While there were no significant differences, Baik and Lim [ 20 ] reported that the social support perceived by survivors decreased as they proceeded through the acute to the extended stage. The social support perceived by respondents decreased in the 2 years following the diagnosis but maintained the reduced rate through the permanent stage [ 20 ]. Long-term survivors had a greater need to meet other cancer patients and self-help groups [ 20 ]. Kwon and Yi [ 27 ] asserted that interest and support from family and the society in general are very important in raising breast cancer survivors’ quality of life and survival rates. Moreover, self-help groups were reported to be effective in providing emotional support for long- and short-term cancer survivors [ 39 ], which indicates the need for developing stage-specific social support interventions and various methods of facilitating social support groups. Moreover, further research is required concerning cancer survival stage-dependent social support and quality of life.

The results of this study showed that higher uncertainty in illness among female cancer survivors led to reduced social support and quality of life, while higher social support led to better quality of life. Support from others was found to be the most relevant aspect of the relationship between quality of life and uncertainty. These results were similar to those of studies on early-stage breast cancer patients [ 40 ] and on cancer patients hospitalized for breast, thyroid, and bladder cancer surgery [ 36 ], which indicated that perceived social support was lower as uncertainty increased.

Uncertainty was very influential on female cancer survivors’ quality of life. Higher uncertainty in illness among female cancer survivors led to lower social support and reduce quality of life; higher social support led to improved quality of life. The explanatory power of these variables on quality of life was 12.1%; uncertainty in illness and social support influenced the quality of life of female cancer survivors. Moreover, in the process of uncertainty in illness influencing subjects’ quality of life, social support was confirmed to play a significant, partially mediating, role in the relationship between uncertainty and quality of life. Higher uncertainty toward illness led to lower quality of life, higher social support led to higher quality of life, and social support influenced female cancer survivors’ quality of life by partially mediating its relationship with uncertainty. Social support plays an important role in directly and indirectly reducing uncertainty [ 18 , 19 ]. Social support is closely related to the prognosis of breast cancer survivors [ 21 ]. Uncertainty among breast cancer survivors has been found to lower their quality of life; however, social support has been found to improve quality of life [ 11 ]. Thus, the need for a diverse range of attempts, including developing and applying social support programs, to increase cancer survivors’ quality of life exists. On the other hand, the partially mediating effects of social support indicate that there are other mediating factors in uncertainty in illness’s influence on quality of life. Therefore, it is important for future studies to include other mediating factors in their examinations of what influences quality of life among female cancer survivors.

In Korea, studies on cancer survivors have been conducted since 2010, and the majority of these focused on breast cancer survivors. Particularly, as there has been no overall research into the healthy behaviors of cancer survivors, it is necessary to develop practical guidelines that befit Korea through studies concerning the development and application of health improvement programs based on the study of healthy behaviors, as per the assertion of Kim [ 32 ]. Moreover, attempts are needed to practically apply a diverse range of intervention studies to improve cancer survivors’ quality of life.

Moreover, future studies should include mediator variables other than social support that might influence quality of life. Additionally, both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies are needed to further investigate the quality of life and uncertainty according to the stages of survival.

Our results show that social support partial mediates the relationship between uncertainty and quality of life in female cancer survivors. The results of this study have great implications for improving cancer care, especially in how it relates to quality of life, and they also demonstrate how uncertainty can be decreased. Therefore, it is necessary to develop and apply intervention methods to improve social support thereby improving quality of life among female cancer survivors. A nurse-led social support program may especially contribute to enhancing the quality of life of cancer survivors by providing them with adequate health information and emotional support.

Availability of data and materials

The data used in this study were collected through questionnaires and analyzed by coding the original data. The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due [REASON WHY DATA ARE NOT PUBLIC] but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Mishel’s Uncertainty in Illness Scale

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support

European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30

Obstetrics/Gynaecology

Lee JE, Shin DW, Cho BL. The current status of cancer survivorship care and a consideration of appropriate care model in Korea. Korean J Clin Oncol. 2014;10(2):58–62. https://doi.org/10.14216/kjco.14012 .

Article Google Scholar

Yoon HJ, Seok JH. Clinical factors associated with quality of life in patients with thyroid cancer. J Korean Thyroid Assoc. 2014;7(1):62–9. https://doi.org/10.11106/jkta.2014.7.1.62 .

Dow KH, Ferrell BR, Leigh S, Ly J, Gulasekaram P. An evaluation of the quality of life among long-term survivors of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1996;39(3):261–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01806154 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Ferrell BR, Dow KH. Quality of life among long-term cancer survivors. Oncology. 1997;11:565–8.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Lee JE, Goo A, Lee KE, Park DJ, Cho B. Management of long-term thyroid cancer survivors in Korea. J Korean Med Assoc. 2016;59(4):287–93. https://doi.org/10.5124/jkma.2016.59.4.287 .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Molassiotis A, Yates P, Li Q, So WK, Pongthavornkamol K, Pittayapan P, et al. Mapping unmet supportive care needs, quality-of-life perceptions and current symptoms in cancer survivors across the Asia-Pacific region: results from the international STEP study. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(10):2552–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdx350 .

Yun YH, Kim YA, Sim JA, Shin AS, Chang YJ, Lee J, et al. Prognostic value of quality of life score in disease-free survivors of surgically-treated lung cancer. BMC Cancer. 2016;16(1):505–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-016-2504-x .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Park JH, Jun EY, Kang MY, Joung YS, Kim GS. Symptom experience and quality of life in breast cancer survivors. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2009;39(5):613–21. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2009.39.5.613 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Chae YR. Relationships of perceived health status, depression, and quality of life of breast cancer survivors. J Korean Adult Nurs. 2005;17:119–27.

Google Scholar

Kim YS, Tae YS. The influencing factors on quality of life among breast cancer survivors. J Korean Oncol Nurs. 2011;11(3):221–8. https://doi.org/10.5388/jkon.2011.11.3.221 .

Sammarco A, Konecny LM. Quality of life, social support, and uncertainty among Latina breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;35(5):844–9. https://doi.org/10.1188/08.ONF.844-849 .

Liao MN, Chen MF, Chen SC, Chen PL. Uncertainty and anxiety during the diagnostic period for women with suspected breast cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2008;31(4):274–83. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NCC.0000305744.64452.fe .

Dirksen S, Erickson J. Well-being in Hispanic and non-Hispanic Caucasian survivors of breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002;29(5):820–6. https://doi.org/10.1188/02.ONF.820-826 .

Husson O, Haak HR, Buffart LM, Nieuwlaat WA, Oranje WA, Mols F, et al. Health-related quality of life and disease specific symptoms in long-term thyroid cancer survivors: a study from the population-based PROFILES registry. Acta Oncol. 2013;52(2):249–58. https://doi.org/10.3109/0284186X.2012.741326 .

Lee JI, Kim SH, Tan AH, Kim HK, Jang HW, Hur KY, et al. Decreased health-related quality of life in disease-free survivors of differentiated thyroid cancer in Korea. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8(1):101. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-8-101 .

Yang J, Yi M. Factors influencing quality of life in thyroid cancer patients with thyroidectomy. Asian Oncol Nurs. 2015;15(2):59–66. https://doi.org/10.5388/aon.2015.15.2.59 .

Oh KS. Social support as a prescription theory. J Nurs Query. 2006;15(1):134–54.

Lien CY, Lin HR, Kuo IT, Chen ML. Perceived uncertainty, social support and psychological adjustment in older patients with cancer being treated with surgery. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18(16):2311–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02549.x .

Mishel MH. Uncertainty in illness. Image J Nurs Sch. 1988;20(4):225–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.1988.tb00082.x .

Baik OM, Lim J. Social support in Korean breast and gynecological cancer survivors: comparison by the cancer stage at diagnosis and the stage of cancer survivorship. Korean J Family Soc Work. 2011;32(6):5–35.

Nausheen B, Kamal A. Familial social support and depression in breast cancer: an exploratory study on a Pakistani sample. Psychooncology. 2007;16(9):859–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1136 .

Alfano CM, Rowland JH. Recovery issues in cancer survivorship: a new challenge for supportive care. Cancer J. 2006;12(5):432–43. https://doi.org/10.1097/00130404-200609000-00012 .

Ashing KT, Padilla G, Tejero JS, Kagawa-Singer M. Understanding the breast cancer experience of Asian American women. Psychooncology. 2003;12(1):38–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.632 .

Janz N, Mujahid M, Chung L, Lantz P, Hawley S, Morrow M, et al. Symptom experience and quality of life of women following breast cancer treatment. J Women's Health. 2007;16(9):1348–61. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2006.0255 .

Min HS, Park SY, Lim JS, Park MO, Won HJ, Kim JI. A study on behaviors for preventing recurrence and quality of life in breast cancer survivors. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2008;38(2):187–94. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2008.38.2.187 .

Kim GD. Impact of climacteric symptoms and fatigue on the quality of life in breast cancer survivors: the mediating effect of cognitive dysfunction. Asian Oncol Nurs. 2014;14(2):58–65. https://doi.org/10.5388/aon.2014.14.2.58 .

Kwon EJ, Yi M. Distress and quality of life in breast cancer survivors in Korea. Asian Oncol Nurs. 2012;12(4):289–96. https://doi.org/10.5388/aon.2012.12.4.289 .

Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173–82. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173 .

Lee I. Uncertainty, appraisal and quality of life in patients with breast cancer across treatment phases. J Cheju Halla Collage. 2009;33:94–112.

Zimet GD, Powell SS, Farley GK, Werkman S, Berkoff KA. Psychometric characteristics of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1990;55(3–4):610–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.1990.9674095 .

Fayers PM, Aaronson NK, Bjordal K, Groenvold M, Curran D, Bottomley A, On behalf of the EORTC Quality of Life Group. EORTC QLQ-C30 scoring manual. 3rd ed. Brussels: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer; 2001. p. 2001.

Kim SH. Understanding cancer survivorship and its new perspectives. J Korean Oncol Nurs. 2010;10(1):19–29.

Lim J, Han I. Comparison of quality of life on the stage of cancer survivorship for breast and gynecological cancer survivors. Korean J Soc Welf. 2008;60(1):5–27. https://doi.org/10.20970/kasw.2008.60.1.001 .

Ahn JY. The influence of symptoms, uncertainty, family support on resilience in patients with breast cancer receiving chemotherapy [master’s thesis]. Seoul: The Seoul National University; 2014.

Lee I, Park CS. Convergent effects of anxiety, depression, uncertainty, and social support on quality of life in women with thyroid cancer. J Korea Convergence Soc. 2017;8(8):163–76. https://doi.org/10.15207/JKCS.2017.8.8.163 .

Park YJ. Uncertainty, anxiety and social support among preoperative patients of cancer: A correlational study [master’s thesis]. Seoul: The Seoul National University; 2015.

Yun M, Song M. A qualitative study on breast cancer survivors’ experiences. Perspect Nurs Sci. 2013;10:41–51.

Ashing-Giwa KT. The contextual model of HRQoL: a paradigm for expanding the HRQoL framework. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(2):297–307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-004-0729-7 .

Adamsen L, Rasmussen J. Sociological perspectives on self-help groups: reflections on conceptualisation and social processes. J Adv Nurs. 2001;35(6):909–17. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01928.x .

Kim HY, So HS. A structural model for psychosocial adjustment in patients with early breast cancer. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2012;42(1):105–15. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2012.42.1.105 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Min, a physician of the Endocrine surgery at Cheju Halla Hospital, for collecting the data. And, we would like to thank the IRB who approved the research and the Editage Company who edited the English.

Conflict of interest

“No conflict of interest has been declared by the author(s).”

The authors did not receive any financial support for this study. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

“This research did not received any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.”

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Nursing, Changwon National University, C.P.O. Box 51140, Changwon, Republic of South Korea

Division of Nursing, Cheju Halla University, Jeju, Republic of South Korea

Changseung Park

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

IL designed the study, searched the literature, analyzed the data, conducted the interpretation of data, drafted and edited the manuscript, and submitted the manuscript for publishing. CSP collected the data, searched the literature, and critically revised the initial manuscript. And all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Insook Lee .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This study approved by IRB in Cheju Halla Hospital (IRB No. 2014-L02) and informed consent to participate.

Consent for publication

This manuscript has never been published in any other journal, and all authors agree to be published in this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Lee, I., Park, C. The mediating effect of social support on uncertainty in illness and quality of life of female cancer survivors: a cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 18 , 143 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01392-2

Download citation

Received : 08 December 2019

Accepted : 05 May 2020

Published : 19 May 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01392-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Health and Quality of Life Outcomes

ISSN: 1477-7525

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

Advertisement

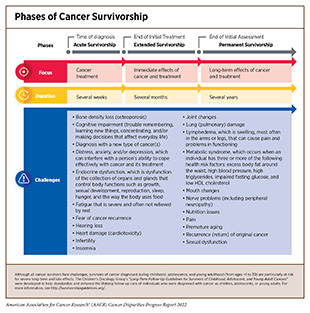

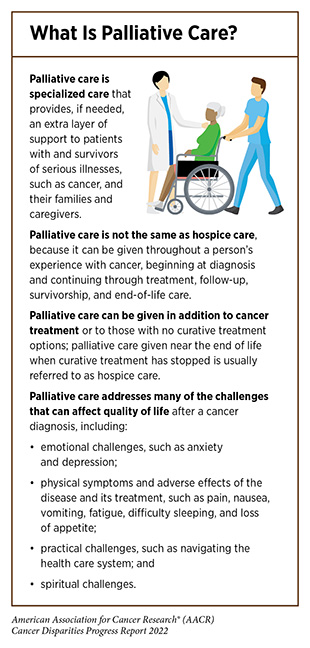

Challenges of Survivorship for Older Adults Diagnosed with Cancer

- Geriatric Oncology (L Balducci, Section Editor)

- Published: 14 March 2022

- Volume 24 , pages 763–773, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Margaret I. Fitch 1 ,

- Irene Nicoll 2 ,

- Lorelei Newton 3 &

- Fay J. Strohschein 4

2686 Accesses

5 Citations

Explore all metrics

Purpose of Review

The purpose of this brief review is to highlight significant recent developments in survivorship research and care of older adults following cancer treatment. The aim is to provide insight into care and support needs of older adults during cancer survivorship as well as directions for future research.

Recent Findings

The numbers of older adult cancer survivors are increasing globally. Increased attention to the interaction between age-related and cancer-related concerns before, during, and after cancer treatment is needed to optimize outcomes and quality of life among older adult survivors. Issues of concern to older survivors, and ones associated with quality of life, include physical and cognitive functioning and emotional well-being. Maintaining activities of daily living, given limitations imposed by cancer treatment and other comorbidities, is of primary importance to older survivors. Evidence concerning the influence of income and rurality, experiences in care coordination and accessing services, and effectiveness of interventions remains scant for older adults during survivorship.

There is a clear need for further research relating to tailored intervention and health care provider knowledge and education. Emerging issues, such as the use of medical assistance in dying, must be considered in this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Older adults with cancer and their caregivers — current landscape and future directions for clinical care

Sindhuja Kadambi, Kah Poh Loh, … Supriya Mohile

Research Methods: Outcomes and Survivorship Research in Geriatric Oncology

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Older adults constitute one of the fastest-growing subgroups in the cancer population [ 1 ]. Over the next decade, the number of individuals 65 years and older who are diagnosed with cancer is expected to double, accounting for 67% of new cancer cases and reaching levels of 14 million worldwide [ 2 ]. Given advances in screening, treatment, and supportive care which have resulted in improved cancer outcomes, the population of older adult cancer survivors is also expected to escalate [ 3 ].

The aftermath of cancer treatment can have a significant impact on survivors [ 4 , 5 ]. Physical, emotional, and practical changes during and after treatment may carry consequences that have a significant impact on the quality of life of survivors [ 6 ], carrying implications for recovery and maintenance of autonomy and independence. Early evidence illustrates that immediate recovery following cancer treatment and improvements in survival for older adults following cancer is slower than for younger survivors [ 7 ••]. For older adults, who may be already dealing with other comorbid conditions and effects of aging, the added burden of late and long-term effects may be particularly troublesome [ 8 ].

Challenges emerging during survivorship add to the complexity of meeting the needs of older adults after cancer [ 9 , 10 ••]. Evidence is beginning to accumulate regarding the unique, multi-dimensional needs of older adults following cancer [ 11 •], and, with it, an understanding of challenges they may face as cancer survivors [ 12 ]. However, further work is needed to fully understand survivorship experiences for this population, gaps in care delivery, and how those gaps could be mitigated.

This paper highlights significant recent developments in survivorship research and care for older adults following cancer. We define survivorship as the interval from completion of primary cancer treatment until the identification of recurrent or progressive disease [ 13 ]. Our aim is to provide insight into care and support needs of older adults during cancer survivorship as well as directions for future research.

A brief review of literature from the last 3 years reporting on older adult cancer survivors aged 65 years and older was undertaken. Relevant topics were identified through consultation with experts in the field and used for search purposes. Keywords used together with “older adults” and “cancer survivors” were accelerated aging, polypharmacy, late/long-term effects, cognitive changes, neuropathy, comprehensive geriatric assessment, survivorship care plans, depression, ethics, and MAiD. A search of Medline via PubMed using the keywords identified relevant English publications from the past 3 years. All article types were considered (e.g., reviews, perspectives papers, descriptive/intervention studies). Each article was reviewed, significant findings identified, and results grouped into broad topic areas. These broad topics are summarized below, presenting significant developments regarding research and care of older cancer survivors reported over the past 3 years.

Aging and Cancer Survival

Four articles addressed patterns of survival among older adults and the impact of little research that considers age-related concerns on patterns and quality of survival in this group. There have been consistent improvements in cancer survival over the past two decades; however, these improvements are smaller for those aged 75 years and older at diagnosis and there is greater variation in 5-year survival across countries for this age group [ 7 ••]. Cellular and molecular changes that occur in non-cancerous cells with aging contribute to a microenvironment that promotes tumor progression and to treatment responses that may impact outcomes, including survival, but are seldom considered in pre-clinical trials [ 14 •]. In addition, a lack of inclusion of older adults in clinical trials, and consideration of outcomes of importance to older adults, means that treatment decisions for older adults with cancer are often based on evidence acquired from younger adults with fewer comorbidities, less polypharmacy, and different physiology [ 15 ].

Accelerated Aging

Not only does aging impact the experience of cancer, but the disease and treatment can also impact the experience of aging among cancer survivors. There is increasing work documenting patterns of accelerated or accentuated aging among people who have experienced cancer treatment [ 16 , 17 ••, 18 ]. Aging is often understood as the “time-dependent accumulation of cellular damage” [ 14 •]. Accelerated or accentuated aging occurs when cancer and cancer treatments contribute to genotoxic and cytotoxic damage that contributes to anatomic and functional changes that mirror those expected with aging, but at a younger age or to a greater degree than would occur in the absence of cancer [ 17 ••]. We identified seven articles exploring relationships among physiological markers of aging, behavioral or functional changes associated with aging, and the receipt of cancer treatment. The aging phenotype caused by cancer and its treatment has been characterized by adverse physical and cognitive consequences, including fatiguability and poor endurance [ 19 ], persistent cognitive impairment [ 20 ], onset of chronic health conditions [ 16 , 21 ••, 22 ], and decreased survival [ 17 ••, 22 ]. Researchers are exploring physiological mechanisms that may contribute to this accelerated aging phenotype among cancer survivors, including DNA damage [ 17 ••, 22 ], stem cell depletion [ 17 ••], alterations in cerebral blood flow [ 20 ], shortening of telomere length [ 16 ], cellular senescence [ 17 ••, 21 ••], and disruption of pathways that mitigate the damaging effects of inflammation and oxidative stress [ 20 , 21 ••]. These physiological changes may be reflected in clinical measures of functional status, frailty, and cognitive function, including subjective measures, such as self-report measures of activities of daily living, and objective measures, such as gait speed and grip strength [ 17 ••]. These changes may also be reflected in biological measures. The authors of recent reviews present a thorough discussion of the biomarkers associated with aging that may be used to assess and/or predict accelerated aging [ 17 ••] or resilience [ 21 ••].

To increase understanding of cancer treatment on aging, appropriate clinical and biological measures of aging of must be incorporated into clinical trials [ 17 ••]. Resilience, defined as capacity to resist or regain physical, cognitive, or psychological function and well-being after a stressor, diminishes with aging and may be defined by age-related biologic processes [ 21 ••]. If so, then clinical and biological measures of aging may also predict resilience in older survivors, and identifying associated physiological and molecular mechanisms may promote the identification of protective factors and strategies to promote resilience and well-being in survivorship [ 21 ••]. Some strategies to prevent accelerated aging include treatment with pharmaceuticals or nutraceuticals that reduce inflammation, treat cardiovascular risk, or improve cardiac function, as well as behavioral strategies including exercise-based interventions considering the unique needs of survivors [ 16 ].

Issues of Particular Concern Among Older Adult Survivors

Eighteen articles describing physical issues, comorbidities, and polypharmacy for older cancer survivors were identified. Ten were studies of older cancer survivors, five focused on older breast cancer survivors, and others addressed issues with older survivors of hematological, oral-digestive and prostate cancers, and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Physical Issues

Studies about older adults following cancer treatment have chiefly focused on physical health and function [ 10 ••, 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 ••, 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 ]. The impaired physical function has been studied as a result of treatment [ 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 ] and several studies compared symptom burden with non-cancer controls or younger cancer survivors [ 23 , 26 , 28 , 29 , 30 ••, 31 , 32 , 33 , 35 ]. In a Canadian survey of over 3000 cancer survivors 75 years or older, 80% reported physical concerns [ 11 •]. Specifically impaired physical function, decline in cardiovascular and other health conditions, fatigue, and depression were studied. The effect of cancer treatment on cardiovascular systems, physical balance, mobility, and neuropathy were reported as significant in older cancer survivors [ 10 ••, 25 , 28 ].

While the importance of physical function in older cancer survivors was explored in some studies, cognitive impairment was highlighted in more than half. Cognitive decline was observed as common in older cancer survivors, but findings varied, ranging from 12 to 75% [ 33 ]. One study observed no association between chemotherapy and cognitive function [ 27 ]. In others, older cancer survivors were shown to demonstrate the decline in executive functioning and verbal memory more frequently than younger adults following treatment [ 26 , 33 ]. Regier et al. [ 33 ] found up to 40% of older cancer survivors exhibited cancer-related cognitive impairment (sustained attention, memory, and verbal fluency) 18 months post-diagnosis while survivors who exhibited high psychoneurological symptoms at diagnosis were more likely to experience greater cognitive decline post-treatment [ 25 , 30 ••, 35 ].

Comorbidities and Polypharmacy

It is estimated 25% of older adults with cancer have five or more comorbid conditions [ 10 ••]. In a recent Canadian study, over 70% of adult survivors 75 years and older reported comorbidities, the four most common being cardiovascular/heart disease (45%); arthritis, osteoarthritis, or other rheumatic diseases (40%); diabetes (16%); and mental health (7%) [ 11 •]. Given the prevalence of other diseases and medical conditions, it is interesting that less than half of the articles addressed comorbidities and fewer discussed the importance of polypharmacy and its implications. While older adults comprise less than 15% of the population of the USA, for example, they account for over 30% of both non-prescription and prescription medications [ 30 ••]. Magnusson et al. [ 30 ••] state that polypharmacy is defined as the use of five or more medications but recognize that researchers less often address appropriate versus inappropriate polypharmacy (lacking evidence base, adverse reactions, etc.). On average, older adults with cancer take nearly 10 different medications and many are uncertain about the reasons they need these medications [ 10 ••]. The impacts of adverse drug effects (e.g., falls, cognitive issues) and drug and disease interactions can be severe. In addition, Guerard et al. [ 10 ••] note that a fragmented group of providers is often responsible for the provision of healthcare to older adults which can result in a lack of communication and coordination among the various specialists involved [ 30 ••] and uncertainty on the part of survivors about where they should seek assistance for an issue [ 12 ].

Overall cancer and its treatments are associated with higher levels of symptom burden and greater loss of well-being over time in older adult survivors, as compared to older adults without cancer, suggesting the need for greater surveillance and opportunities for intervention [ 31 ]. In addition, many older adults are at risk for experiencing physical, emotional, and practical concerns following cancer treatment yet are not obtaining desired help [ 12 ]. Coughlin et al. noted that given prevalent age-related issues such as comorbidities, osteoporosis, symptoms, physical functioning, cognitive functioning, nutrition, and physical activity [ 37 ], appropriate surveillance, screening (including pre-screening for at-risk individuals), and interventions both during and post-treatment are critical to improve associated functional/neurological changes and improve the overall quality of life [ 24 , 30 ••, 31 , 32 , 33 ]. Future research is needed about the nature and extent of disability and symptom burden to develop survivorship programs for this distinct patient population [ 29 ] and inform the development of guidelines and policies in conjunction with patients’ preferences and goals [ 10 ••].

Factors Influencing Quality of Life in Older Adult Survivors

A primary direction of research regarding older adult cancer survivors has been identifying factors that influence quality of life. Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) is seen as a primary outcome given that priorities and values for older adults shift as they age [ 38 ] and acknowledge they have few remaining years. However, age alone is insufficient to explain variations in this populations’ HRQOL. Both cancer (e.g., cancer type, treatment modality, recurrence) and non-cancer-related (e.g., education, income, residence) factors contribute [ 38 , 39 , 40 ].

Most studies reviewed included survivors of breast, prostate, lung, and colorectal cancers, making use of existing databases and frequently resulting in sizeable sample sizes (121 [ 41 ] to 271,640 [ 42 •]. Studies involved various time intervals following completion of treatment (1 to > 10 years), definitions of older adults (e.g., 60+, 75+, 70+, 75+, and 80+ years) and combinations of physical, psychological, emotional, social, and demographic variables. Overall, there is agreement that HRQOL is lower in older adult survivors than in general older adult populations [ 42 •, 43 ].

Consistently physical variables have the strongest associations with HRQOL. Although these variables were measured in various ways, (e.g., physical well-being [ 44 •], functional health limitations [ 38 ] disability [ 45 ], mobility [ 46 , 47 ], and physical health status [ 48 ], the capacity to manage activities of daily living and maintain independence were critical for older adult survivors and contributed to HRQOL. Cancer type [ 49 •], the number of comorbidities [ 42 •, 45 ], length of time dealing with side effects, side effect severity [ 43 , 50 , 51 ], duration of chronic illness [ 39 ], and deteriorating health status [ 41 , 45 ] are key variables with negative influence on HRQOL. Experiencing fatigue [ 44 •], frailty [ 53 ••], difficulty performing Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) [ 53 ••], difficulty walking [ 46 ],) and increased risk for falls [ 47 , 48 ] are challenges associated with poor HRQOL outcomes [ 53 ••] in older survivors. In a sample of 3274 older cancer survivors, when asked to identify the main challenge, they experienced in transitioning to survivorship, over 68% identified physical limitations [ 11 •].

Psychosocial variables have not been explored as frequently as physical variables in older cancer survivors. Depression [ 40 , 50 ], body image (appearance) [ 51 , 54 ], reduced optimism [ 55 ], altered sexual intimacy [ 56 ], treatment decision regret [ 57 ], chronic stress (55), lack of emotional support [ 39 ], and post-traumatic growth [ 41 ] are associated with reduced HRQOL. Depression is concerning in this population, reaching levels of 30% in community-dwelling older survivors [ 40 ]. Increased levels of depression are associated with female gender, number of symptoms [ 50 ], living alone [ 40 ], reduced income [ 40 ], and recurrence [ 40 ]. Additionally, social well-being, which is associated with social support and satisfaction with psychosocial need fulfillment [ 58 ], is associated with QOL [ 41 ]. Attending to environmental barriers which hinder engagement in social activities and reintegration in the community is important for older survivors given isolation contributes to reduced QOL [ 58 ].

Two variables beginning to receive attention in survivor populations are income and rurality. A larger proportion of older cancer survivors with low household income have concerns and seek help for physical, emotional, and practical issues than those with higher incomes [ 59 ]. However, similar proportions of low- and high-income older survivors experienced difficulty obtaining help for their concerns. In general, lower levels of subjective socioeconomic status are associated with lower QOL across all domains [ 39 , 41 , 49 •], non-adherence in purchasing medicines and supplies [ 60 ], and foregoing tests, procedures, and care [ 61 ].

Although rurality has been investigated regarding access to screening, diagnostic, and treatment services, few studies have looked at access to services for survivorship care, especially for older adults. Access to services presents different challenges for survivors than for cancer patients; survivors want services close to home rather than traveling for specialist treatment [ 62 ]. Moss et al. [ 42 •] reported QOL is higher for older survivors living in urban settings where access to ancillary services such as social work, physiotherapy, and support groups is easier. The need to leverage the higher social integration in rural communities to enhance emotional support for older adult survivors is recommended.

Interventions for Older Adult Cancer Survivors

Few studies regarding the effectiveness of interventions designed for older adult cancer survivors were identified in our search. Interventions receiving the most attention included incorporating comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) and physical exercise.

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment

Older adults present a wide variation in health and functional status that may be exacerbated by cancer treatment and present various life challenges [ 63 ]. The use of screening and other assessment tools is helpful for identifying patient needs and planning appropriate interventions, particularly for distinct populations such as older adults.

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) is a process of evaluating and improving functional ability, physical health, cognition and mental health, and socio-environmental circumstances of older adults. Assessment results are reviewed by healthcare teams, discussed with patients, and incorporated into care plans. Nishuima et al. [ 64 •], for example, propose an approach to CGA comprised of assessments in 10 impairment domains (cognition, mood, communication, mobility, balance, bowels, bladder, nutrition, daily activities, and social) and a single comorbidity domain. Geriatric assessed impairments were associated with increased hospitalizations and long-term care use in older adults with cancer [ 65 ]. Benefits of CGA include treatment effectiveness and efficacy, prediction of mortality and cancer treatment tolerance, and decision-making to establish the appropriate treatment of cancer [ 66 ••]. CGA also helps identify significant comorbidities and polypharmacy [ 67 ] and patients who might benefit from less invasive and more tolerable evidence-based treatments [ 68 ]. Studies have shown that participants receiving CGA-based intervention report significantly better HRQOL [ 63 ].

While GA is helpful in identifying deficits in older adults with cancer and is considered a critical component in oncology treatment planning, with demonstrated feasibility and effectiveness, it is not widely implemented [ 63 , 65 , 67 , 68 ]. The incorporation of geriatric screening can be taxing to this population particularly if multiple surveys/screening tools related to geriatric domains are used in addition to those related to distress and patient-reported outcomes. In addition, healthcare providers find the incorporation of CGA into daily practice time-consuming [ 63 ]. Successful implementation requires the involvement of the multi-disciplinary team, strong administrative and patient scheduling support, and planning [ 66 ••]. Given the complexities of care for older adults with cancer, the introduction of CGA in post-treatment care, as an aspect of survivorship care planning, for example, could assist in isolating survivors’ critical health issues, identifying appropriate therapies, and enhancing survivorship care coordination.

Physical Activity/Exercise

More than 50% of older cancer survivors are not achieving standards for physical activity (PA) [ 44 •, 54 ]. Given the potential impact of PA on recovery and capacity to perform activities of daily living (ADLs), finding relevant and effective physical programming for older adults with cancer has become a priority. Unfortunately, current guidelines are based on research with younger populations. A recent systematic review of the effectiveness of PA interventions in older survivors identified 14 studies [ 69 ••]. However, interventions varied in duration (1 to 12 months), intensity, settings, and outcome measurements, making it difficult to draw conclusions about specific approaches for older survivors.

Given the choice about what interventions to pursue in one study, older adults selected PA [ 70 ]. Older survivors reported they used PA programs to increase engagement and performance of ADLs and reduce sleep disturbances and fatigue [ 70 , 71 , 72 ]. In addition, interventions help with issues of body image and psychosocial distress [ 44 •, 54 , 72 ]. Barriers included time, transportation, lack of facilities, weather, and pain [ 44 •, 70 , 72 ] while their preferences included structured programs incorporated with cancer care, having supervision, and being able to use equipment aids [ 70 , 72 ].

Older Adult Survivor Perspectives Regarding Experiences with Care

A small but growing body of evidence is emerging which captures survivors’ perspectives about experiences with cancer care delivery and suggestions for improvement. Given the complexity of needs and challenges in addressing concerns, it is important to understand the views of older survivors who have accessed services.

In quantitative investigations, higher access to services and higher self-reported health status were associated with better care experiences [ 73 ]. Variations in care experiences exist by education, gender, and cancer types. Scores indicating patient perceptions of higher care coordination are associated with living rurally at diagnosis, having fewer specialists involved in care, and more frequent visits with a family doctor [ 74 ]. Low scores are reported by women with metastatic disease, those with higher education, and individuals over 80 years of age [ 74 ].

A thematic analysis from Canada described perspectives of older adults regarding challenges experienced during survivorship care and suggestions for improvements. Themes regarding challenges included: “Getting back on my feet,” “Adjusting to life changes,” and “Finding the support I need” [ 11 •], while those regarding suggestions for improvements were, “Offer me support,” “Make access easy for me,” and “Show me you care” [ 36 ]. In this same study, communication, information, and access to a range of services were considered important yet remained gaps in service delivery by 82% of respondents.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, older adult survivors were reported to be among one of the most disadvantaged groups and needed special consideration in terms of support [ 75 ]. One qualitative study reported older survivors [ 76 ] indicated they understood the situation but that they missed interactions with others. Survivors found virtual clinic appointments were helpful, especially in reducing needs for transportation, but they were not as beneficial for social interaction as in-person visits.

Suggestions Regarding Future Research and Care Across Articles

Many articles contained recommendations about screening to identify at-risk individuals and utilizing deeper assessment of needs to build tailored interventions. Incorporating self-report by older survivors for aspects such as physical health, mobility, and emotional distress was emphasized [ 43 , 48 , 50 ] together with a relevant discussion of preferences [ 38 ]. Older survivors are a heterogeneous population with unique and complex needs. The priorities in unmet needs vary [ 12 ] and what will be most effective in meeting those needs differs from other age groups [ 77 ]. Yet health care professionals report a lack of confidence in caring for this population [ 78 ]. Enhancing knowledge and skill for survivorship care of older adults, guided by standards for optimizing care for this population [ 78 , 79 ], needs consideration.

Several areas of interventions used with other populations may have potential relevance for the older adult survivor cohort and could be considered for future program design and implementation. Lay Navigation [ 80 ], nurse coordination models [ 74 ], home telehealth [ 74 , 76 ], use of survivorship care plans [ 81 , 82 ], and active involvement of caregivers/partners in care planning [ 83 , 84 ] could be explored given the interventions were designed with the unique needs of older survivors in mind.

An Emerging Consideration from Clinical Care

An emerging issue regarding the clinical care of older adults with cancer is the marked increase in requests for medical assistance in dying (MAiD) [ 85 ]. The concept of MAiD encompasses the terms assisted suicide and euthanasia [ 86 •] with MAiD legislation originally aimed to ease the burden of suffering of imminent death. Conversation of the right to access MAiD most often centers on individual autonomy and dying with dignity (e.g., Selby et al. [ 87 •]), conceptualized as having control over one’s destiny. It has been strongly associated with an unacceptable situation of being dependent and a burden to the family. Definitions and restrictions of MAiD, guided by healthcare providers’ standards of practice, organizational policies, and professional codes of ethics, vary depending on jurisdiction-specific legislation. MAiD is often framed as a procedure; however, this patient choice also represents an extensive social movement in which a multitude of legal, ethical, regulatory, and clinical factors converge with highly personal values and beliefs involved. No discussion about this issue emerged in the literature regarding older adult cancer survivors, leaving little guidance for negotiating the difficulty of providing ethical options while also countering ageist discourses influencing patient choices.

The majority of people who consider MAiD have a pre-existing cancer diagnosis [ 88 •, 89 , 90 , 91 •]. A recent Canadian survey of oncologists reported 70% encountered a patient request for MAiD [ 92•• ]. Nurses also grapple with requests for medical assistance in dying (MAiD) among older adults with cancer, perceiving it to be a response to suffering, being a burden in survivorship, and not wanting to engage in treatment or transition to palliative care [ 80 ]. Concerns that uncontrolled physical and psychological symptoms may prompt premature requests for MAiD are warranted [ 91 •]. Furthermore, understanding the interplay of depression and demoralization, factors which are often undertreated and unaddressed in older adults, with MAiD requests is essential. The research provides a better understanding of these influences and provides guidance for practice underway [ 93 •].

In support of appropriate access and choice regarding MAiD, current evidence supports that clear and direct discussions with an interdisciplinary approach enhance therapeutic relationships [ 91• , 94 , 95 ]. At the same time, MAiD must remain person-centered to humanize a medicalized activity [ 96 ••]. Such conversations have implications for all patients, and more specifically older adults with cancer. The conversations are apt to occur within a largely unquestioned backdrop of system-level ageism, an often unaccounted for force impacting cancer care [ 36 ]. Healthcare professionals must consider messages they transmit when they commit to having explicit conversations about assistance for dying but not to the assistance required for living with the challenging side effects of cancer and subsequent treatment as patients move in and through survivorship. Evidence-informed guidelines are essential to support the transition through active treatment to survivorship. Clearly, there is need for further research in this area in the context of survivorship.

Existing Guidelines to Inform Intervention

Guidelines established by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network [NCCN] [ 97 ] and the American Society of Clinical Oncology [ 98 ] provide a framework for assessing and managing age-related concerns prior to and during cancer treatment. In addition, priorities to optimize care of older adults with cancer have been identified [ 79 , 99 , 100 ] and recommendations to support quality of life during all phases of the cancer trajectory, including survivorship, have been developed [ 101 ].

The body of evidence for guiding care of older adult cancer survivors is growing and confirms the unique and complex needs of this population. Screening at-risk individuals and connecting them to appropriate resources is important. Tailored assessments and interventions before, during, and after treatment are necessary to optimize survivorship care. However, additional research is required to design truly age appropriate and effective care approaches. By strengthening the evidence base to better inform treatment decision-making, outcomes for older adults with cancer may be improved, both in terms of survival and quality of life in survivorship.

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Miller KD, Nogueira L, Mariotto AB, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:363–85.

Article Google Scholar

Pilleron S, Sarfati D, Janssen-Heijnen M, et al. Global cancer incidence in older adults, 2012 and 2035: a population-based study. Int J Cancer. 2019;144:49–58.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Parry C, Kent EE, Mariotto AB, et al. Cancer survivors: a booming population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:1996–2005.

Lerro CC, Stein KD, Smith T, Virgo KS. A systematic review of large-scale surveys of cancer survivors conducted in North America, 2000–2011. J Cancer Survivorship. 2012;6:115–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-012-0214-1 .

Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E. From cancer patient to cancer survivor: Lost in transition. Institute of Medicine, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. 2006

Hamrood R, Hamrood H, Merhasin I, Kenan-Boker L. Chronic pain and other symptoms among breast cancer survivors: prevalence predictors and effects on quality of life. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;167(1):157–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-017-4485-0 ( Epub 2017 Aug 31 ).

Arnold M, Rutherford MJ, Bardot A, Ferlay J, Andersson TML, Myklebust TÅ… Bray F. Progress in cancer survival, mortality, and incidence in seven high-income countries 1995-2014 (ICBP SURVMARK-2): A population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(11);1493–1505. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30456-5 . Longitudinal, population-based study in which researchers analyzed patient-level data of 3.9 million patients drawn from population-based cancer registries in seven countries. They calculated age-standardized net survival at 1 and 5 years by tumor site, age group, and period of diagnosis.

Corbett T, Bridges J. Multimorbidity in older adults living with and beyond cancer. Current Opinion in Supportive and Palliative Care. 2019;13:220–4. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPC.0000000000000439 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar